Abstract

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) or concussion is a substantial health problem globally, with up to 15% of patients experiencing persisting symptoms that can significantly impact quality of life. Currently, the diagnosis of mTBI relies on clinical presentation with ancillary neuroimaging to exclude more severe forms of injury. However, identifying patients at risk for a poor outcome or protracted recovery is challenging, in part due to the lack of early objective tests that reflect the relevant underlying pathology. While the pathophysiology of mTBI is poorly understood, axonal damage caused by rotational forces is now recognized as an important consequence of injury. Moreover, serum measurement of the neurofilament light (NfL) protein has emerged as a potentially promising biomarker of injury. Understanding the pathological processes that determine serum NfL dynamics over time, and the ability of NfL to reflect underlying pathology will be critical for future clinical research aimed at reducing the burden of disability after mild TBI. Using a gyrencephalic model of head rotational acceleration scaled to human concussion, we demonstrate significant elevations in serum NfL, with a peak at 3 days post-injury. Moreover, increased serum NfL was detectable out to 2 weeks post-injury, with some evidence it follows a biphasic course. Subsequent quantitative histological examinations demonstrate that axonal pathology, including in the absence of neuronal somatic degeneration, was the likely source of elevated serum NfL. However, the extent of axonal pathology quantified via multiple markers did not correlate strongly with the extent of serum NfL. Interestingly, the extent of blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability offered more robust correlations with serum NfL measured at multiple time points, suggesting BBB disruption is an important determinant of serum biomarker dynamics after mTBI. These data provide novel insights to the temporal course and pathological basis of serum NfL measurements that inform its utility as a biomarker in mTBI.

Keywords: Mild traumatic brain injury, Concussion, Neurofilament light, Blood brain barrier, Diffuse axonal injury, Serum biomarkers

Introduction

Of the ~ 2.8 million traumatic brain injuries (TBI) sustained each year in the United States, an estimated 75% are classified as mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) or “concussion” [25, 90]. While the majority of mTBI patients experience early and complete recovery without intervention, up to 15% of patients can have persistent symptoms that significantly impact quality of life [68, 69]. Currently, the diagnostic approach to mTBI relies largely on clinical presentation, with conventional neuroimaging playing an important ancillary role to rule out the presence of more severe pathologies, particularly those requiring neurosurgical intervention [33]. Indeed, there are no objective tests that diagnose mTBI via the identification of a specific underlying pathology. Furthermore, there is no objective pathology-based metric by which to monitor recovery or stratify patients at risk of poor outcome.

Serum measurement of the neurofilament light protein (NfL) has emerged as a promising biomarker across a spectrum of neurological diseases [21], including TBI [4, 7, 21, 45, 47, 76–78]. As an important constituent of neurons, the presence of NfL in blood has been proposed as a surrogate marker of neuronal injury, and more specifically axonal degeneration [21]. Notably, diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is one of the most common and important pathologies of moderate and severe TBI and is increasingly acknowledged as a key pathological substrate of concussion [9, 10, 20, 41, 55, 58, 81]. Increases in serum NfL have been observed following moderate or severe TBI [27, 47, 76] and may reflect the extent of DAI, as well as predict the presence of neuroimaging findings and outcome [4, 27, 43, 47, 76]. In contrast, while increased serum NfL has been observed acutely following sports-related concussion [6, 52], others have failed to observe differences [62, 97], which may reflect variability in sampling, the cohorts examined, or heterogeneity in the underlying pathologies. Interestingly, participants of American football demonstrated increases in serum NfL when compared with pre-season levels [60, 61], as did boxers following a bout [79]. Measurement of serum NfL in ice hockey players acutely post-concussion was also able to predict longer durations of recovery prior to return to play or resignation from participation due to post-concussion symptoms [78]. However, little is known about how the amount of NfL in serum either reflects or is influenced by the nature and extent of the evolving cellular pathologies post-injury, which may have important implications for both its diagnostic and prognostic utility. Moreover, the advent of an objective and pathophysiologically-relevant means to assess concussion may inform patient selection for future interventional trials targeting specific pathological mechanisms.

Rotational forces caused by rapid unrestrained head motion or following direct head impact have long been described as an important cause of DAI [22, 35, 54]. Indeed, mechanical forces applied to axons at the instant of trauma can cause immediate structural damage to the axonal cytoskeleton, including disruption of microtubules [88, 89]. Subsequent deleterious cascades including activation of proteases, ionic dysregulation and metabolic failure can further promote cytoskeletal degradation and together perturb the transport of axonal cargo [14, 16, 32, 39, 51, 53, 66, 72, 73, 82, 85, 96, 101]. The resultant pathological accumulation of transported cargo appears as varicose swellings at periodic intervals along injured axons, or ultimately, at points of disconnection [88, 98]. Indeed, multiple proteins have been identified within axon swellings via immunohistochemistry including neurofilament subtypes [13–16, 18, 26, 63, 67, 72, 86, 102], ubiquitin [75] and spectrin breakdown products [16, 36, 53, 72, 73, 96]. However, the rapid and abundant accumulation of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) led to its adoption as the primary marker for the neuropathological identification of DAI [24, 35, 80]. APP immunoreactive axonal pathology has notably also been described in human tissue following concussion [9, 10]. Moreover, we previously demonstrated head rotational accelerations in swine scaled to human concussion can induce widely-distributed axonal pathology with accumulation of both NfL and APP [36]. Interestingly, this same model also demonstrated BBB permeability, with extravasation of serum proteins observed in a distribution consistent with a biomechanical etiology, yet in the absence of hemorrhage [37]. In support of this observation, advanced neuroimaging studies report acute BBB permeability following human mTBI [103], and in participants of contact sports [59, 99].

Characterizing histopathological outcomes from mTBI in parallel with serum biomarker measurements may offer important mechanistic insights as to the biological source of NfL at the subcellular level, and determine whether serum NfL reflects the nature and extent of neuronal injury. In addition, BBB integrity may be critical in determining NfL dynamics in blood. Here we characterize temporal serum NfL concentrations for up to 2 weeks following a standardized gyrencephalic model of mTBI induced by head rotational acceleration-deceleration [36, 37]. Subsequent quantitative histological examinations and detailed mapping were performed for axonal pathology, BBB permeability, and neuronal degeneration to elucidate the pathophysiological basis of serum NfL observations.

Materials and methods

Rotational acceleration model of concussion

All in vivo experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Under anesthesia, six-month-old female Hanford miniature swine (weighing 29.0 ± 3.6 (SD) Kg) were subjected to an established model that induces mTBI via forces caused by rotational acceleration/deceleration due to pure impulsive centroidal head rotation [12, 36, 54, 70, 83, 84].

The size of the brain plays a critical role in determining the nature and extent of pathology in TBI. Specifically, significant mass effects between regions of tissue can create high strains during dynamic brain deformation caused by rapid accelerations [29, 30, 49]. Accordingly, given the smaller mass of the swine brain, injury parameters of the model were scaled relative to brain mass to recapitulate the mechanical loading of tissue relevant to that which occurs in human mTBI [29, 30, 49, 54, 92].

Following induction of anesthesia using 0.4 mg/kg midazolam IM and 5% inhaled isoflurane, animals were intubated and anesthesia maintained via 2.5% inhaled isoflurane. The HYGE pneumatic actuator device was used to induce rapid head rotation. Specifically, the HYGE actuator generates linear motion via the triggered release of pressurized nitrogen. This linear motion is then converted to angular motion via custom-designed linkage assemblies to induce rotation over 20 ms. Rotational kinematics were recorded using angular velocity transducers (Applied Technology Associates) mounted to the linkage sidearm coupled to a National Instruments data acquisition system running custom LabView software (10 kHz sampling rate). In this fashion, we produced pure impulsive centroidal head rotation of up to 110° in the coronal plane with peak angular velocity of 225–253 rad/s. Animals were recovered from anesthesia and returned to the housing facility. While the procedure is non-surgical, preemptive analgesia was provided post-injury in the form of 0.1–3 mg of Buprenex (extended-release preparation).

Recovery was measured as time from withdrawal of isoflurane to extubation and mobilization on all 4 limbs, as well as time to resuming eating/drinking. All animals were observed in their home cage initially and at 24 post-RAI for the presence of any overt behavioral and neurological deficits, including appropriate mentation, gait, motor function and balance, coordination and basic visual/auditory perception, ability to chew /swallow. Sensation to touch was also assessed.

Following mTBI, animals were survived for 48 h (n = 2), 72 h (n = 6) and 2 weeks (n = 3). Additional sham animals were also subjected to identical procedures absent head rotation with survival of 72 h (n = 2) and 2 weeks (n = 1). No animals were excluded. All experiments and measurements were conducted in a standardized fashion in accordance with defined standard operating procedures.

At the study endpoint, all animals were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused using chilled heparinized saline (2L) followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) (8L). Brains were subsequently post-fixed for 7 days in 10% NBF, dissected into whole slice 5 mm blocks in the coronal plane and processed to paraffin using standard techniques.

Serum measurements of neurofilament light

Serial blood samples were collected via an indwelling catheter in the cephalic vein prior to and following mTBI or sham procedures. Samples were collected in glass vacutainers without additives (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) prior to injury (n = 10) and at 40 m (n = 7), 1.5 h (n = 6), 3–4 h (n = 11), 8 h (n = 8), 18 h (n = 3), 24 h (n = 6), 48 h (n = 8), 72 h (n = 9), 5 days (n = 3), 7 days (n = 3) and 14 days (n = 3) post-injury. In addition, samples were collected from sham animals prior to sham procedures (n = 3) and at 40 m (n = 2), 1.5 h (n = 1), 3–4 h (n = 3), 8 h (n = 2), 18 h (n = 1), 24 h (n = 3), 48 h (n = 3), 72 h (n = 2) and 14 days (n = 1) post-sham procedures.

Serum samples were prepared by allowing whole blood samples to clot for 30 min before centrifugation at 1300 g for 5 min. The supernatant was then removed and subjected to additional centrifugation for 10 min at 1300 g. 100 μL aliquots of the supernatant (serum) were prepared in sterile polypropylene cryotubes (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) and frozen at −80 °C for future use.

All samples were defrosted and immediately applied in duplicate to the Quanterix NfLight assay (reported LLQ: 0.174 pg/ml and LLD: 0.038 pg/ml per manufacturer). Serum NfL concentrations were measured using the Quanterix NF-Light Advantage version 2 (v2) LOT 501733 and 501706 and the Quanterix HD-1 Simoa Analyzer (Quanterix Corporation, Billerica, MA). Any samples where the co-efficient of variance was greater than 20% were repeated. The average co-efficient of variance was 5.6%. As an additional control for the specificity of the assay, a sample with previously established increased NfL (72 h post-injury) was reanalyzed with the NfL-specific detector antibody replaced with an antibody for another brain protein to determine if all signal was NfL specific. In this instance, an antibody specific for APP (biotinylated 22C11 clone, Millipore, Burlington, MA) was applied and showed no signal within the detectable range. Assays were performed blind to the experimental group.

Histological examinations

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E): 8 µm sections were generated using a rotatory microtome and sections from all blocks at 5 mm intervals throughout the entire rostro-caudal extent of the brain were subjected to standard H&E staining as described previously [34].

Single Immunohistochemical Labeling: All immunohistochemical (IHC) examinations were performed on 8 μm whole-brain coronal paraffin sections at 5 brain levels including: 1. The level of frontal cortex 5 mm from the frontal pole, including prefrontal cortex; 2. the level of the basal ganglia at the head of caudate nucleus; 3. the level of anterior hippocampus; 4. the level of posterior hippocampus at the level of the posterior commissure; and 5. the medulla. Levels were selected to incorporate a wide sampling spanning the rostro-caudal extent of the entire brain.

Following deparaffinization and rehydration, tissue sections were immersed in aqueous hydrogen peroxide (15 min) to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigen retrieval was performed in a microwave pressure cooker with immersion in preheated Tris EDTA buffer. Subsequent blocking was achieved using 1% normal horse serum (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) in Optimax buffer (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) for 30 min. Incubation with the primary antibodies was performed overnight at 4 °C. Specifically, sections were labeled with an antibody reactive for the N-terminal amino acids 66–81 of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Millipore, Billerica, MA; 1:80 k) to identify axonal pathology as APP accumulations within terminal bulbs or tortuous varicosities caused by transport interruption. In addition, adjacent sections were incubated with the NfL specific antibody, UD2 (Uman Diagnostics, Umea, Sweden). Notably, this antibody is included within the Quanterix assay performed to quantify serum NfL as described above. Lastly, a third set of adjacent sections were stained for the serum protein fibrinogen using a rabbit polyclonal antibody targeting the full-length swine fibrinogen at 1:5 k (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Fibrinogen is not normally present in the brain parenchyma under physiologic conditions and thus extravasated fibrinogen in the brain parenchyma is representative of BBB permeability as previously described [37].

After rinsing, sections were incubated with the appropriate species-specific biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), followed by the avidin–biotin complex (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Finally, visualization was achieved using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and counterstaining with haematoxylin performed.

Positive control tissue for APP and NfL IHC included sections of swine tissue with previously established DAI. Positive control tissue for fibrinogen IHC included a section of swine brain tissue with contusional injury with associated overt BBB permeability. Omission of primary antibodies was performed on the same material to control for non-specific binding for each individual IHC experiment.

Immunoenzymatic Double Labeling: For all animals, an additional subset of whole brain coronal sections were examined at the level of the basal ganglia at the head of caudate nucleus using double labeling to directly examine the relative distributions of fibrinogen extravasation and NfL immunoreactive injured axons. Specifically, NfL staining was performed as described above using DAB visualization before being subsequently incubated with the same fibrinogen antibody as above (1:3.5 K) for 20 h at 4 °C. Detection of fibrinogen was then achieved via the ImmPRESS™-AP anti-rabbit IgG (alkaline phosphatase) polymer detection kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) followed by the Vector blue alkaline phosphatase substrate kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) per manufacturer’s instructions. After rinsing, slides were coverslipped using an aqueous mounting medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA).

Fluoro-Jade C Staining: As a marker of degenerating neurons, Fluoro-Jade C staining [74] was performed on serial sections from all 5 brain levels as described for IHC. Specifically, following dewaxing and rehydration to water as above, tissue was the immersed in a 0.06% potassium permanganate solution for 20 min at room temperature. After being rinsed in flowing dH2O, tissue was incubated in 0.00012% Fluoro-Jade C solution (Millipore, Billerica, MA) in 0.1% acetic acid at room temperature for 30 min. After rinsing, sections were dried in an oven at 37 °C for 90 min before being immersed in xylenes and coverslipped. Positive control tissue included sections of swine brain tissue with contusional injury with associated neuronal degeneration. Negative controls included the same tissue with all procedures applied absent the application of the Fluoro-Jade C reagent.

Analysis and quantification of neuropathological findings

Review of neuropathology was performed blind to the experimental group. In additional to gross neuropathological examination, H&E stained sections at 5 mm intervals throughout the entire rostro-caudal extent of the brain were reviewed for the presence of hemorrhage, including microhemorrhage, ischemic change, evidence of raised ICP or any other focal pathology.

Extent and Distribution of Immunohistochemical Findings: Whole-brain sections in the coronal plane stained for APP, NfL and fibrinogen from each of the 5 levels as described above were subjected to high resolution scanning at 20X magnification using the Aperio ScanScope and viewed using associated Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Injured axons were identified and defined as those that were APP or NfL immunoreactive with an injured morphology including 1. Terminal axonal swellings or axonal bulbs, formerly referred to as retraction balls; 2. Axons with a beaded or fusiform morphology representing multiple points of apparent transport interruption as has been extensively described previously, including in this model [23, 24, 34–37, 80, 88]. Upon identification, each individual injured axon was manually tagged using the annotation tool in the Aperio ImageScope software across the entire whole brain coronal section, in all 5 brain levels examined. This produced detailed distribution maps (see example in Fig. 3d). In addition, the number of pathological axons was quantified per unit area of tissue across all 5 whole-brain levels.

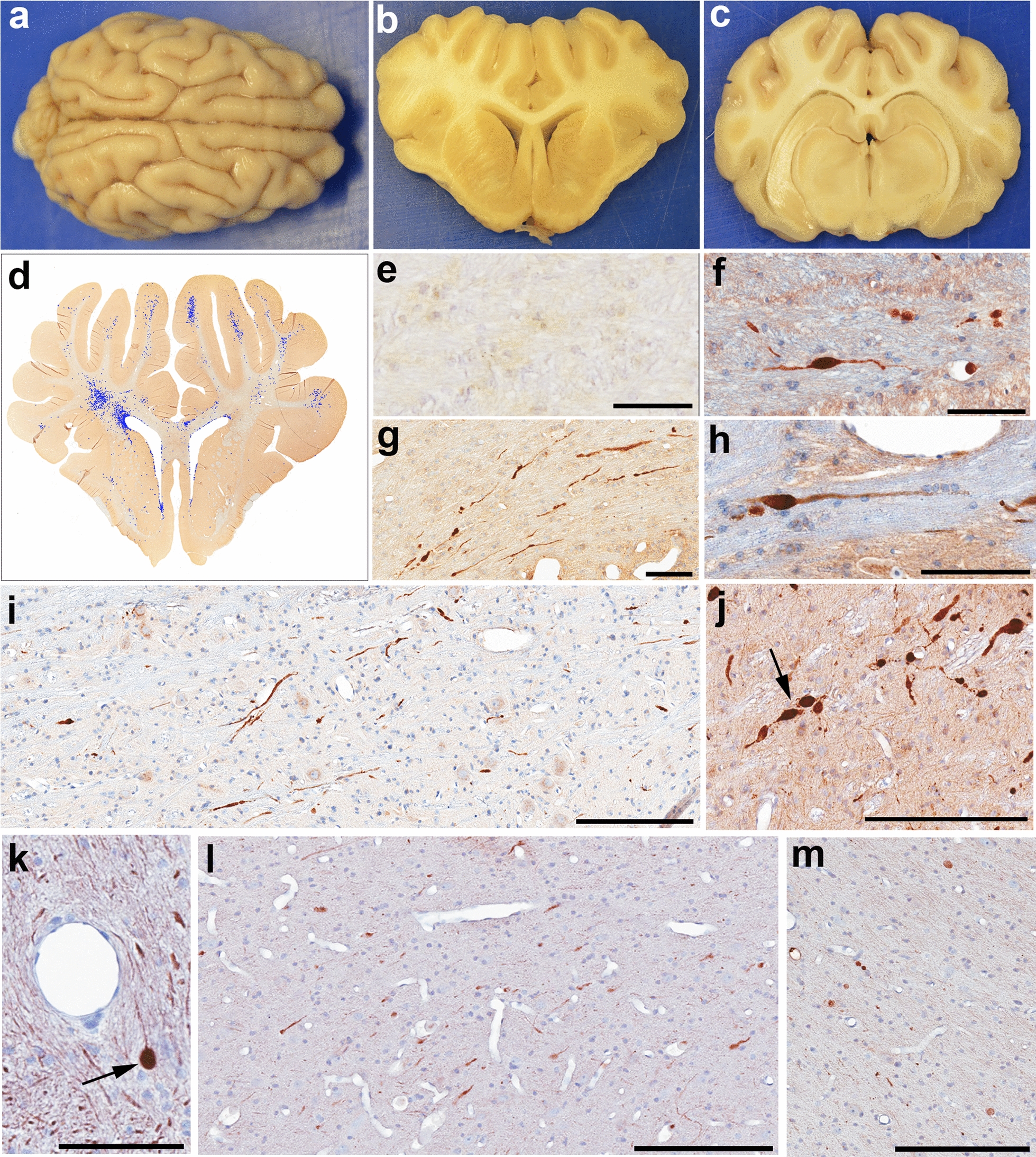

Fig. 3.

Gross Neuropathological Findings and Axonal Pathology. Representative example of the gross appearance of a the whole brain, and coronal tissue blocks at the level of b the lateral ventricles and c hippocampus 72 h following mTBI. The brain appears grossly normal and symmetrical, without evidence of significant brain swelling, hemorrhage or other focal pathologies. d Representative map showing the extent and distribution of APP + injured axonal profiles on a manually annotated tissue section following high-resolution digital scanning at 20X magnification. e An absence of APP immunoreactive swellings in the centrum semiovale of a sham animal at 72 h. f–j Injured axons displaying APP immunoreactive swellings within the centrum semiovale at the level of the anterior hippocampus 48 h post-mTBI (f), adjacent to the lateral ventricle 48 h post-mTBI (g), at 72 h post-mTBI within the internal capsule (h) and the brainstem (i), and 2 weeks following mTBI within the brainstem (j). Note the arrow in (j) showing multiple serial swellings due to multiple points of partially interrupted transport. k Injured axons displaying NfL immunoreactive swellings within the centrum semiovale. Arrow denotes a large spheroid with apparent terminal disconnection. l NfL immunoreactive injured axons in the white matter of the superior frontal gyrus at 48 h post mTBI m NfL immunoreactive injured axons 2 weeks post-mTBI within the grey-white interface of the insular cortex. Scale Bars: F, G: 90 µm, E, H, K: 100 µm, I, J, L, M: 200 µm

Similarly, digital scans of fibrinogen stained sections were reviewed and regions of extravasated fibrinogen indicative of BBB permeability outlined using the aforementioned annotation tools (Aperio ImageScope). The percentage area of fibrinogen immunoreactivity relative to the total section area was again determined across the entire whole-brain coronal sections across all 5 brain levels per animal.

To determine the extent of neuronal degeneration, Fluoro-Jade C stained sections were reviewed across the 5 representative brain levels as above and the number of individual positively stained neurons quantified for each brain section for all animals.

Statistical analyses

To assess for differences in serum NfL at the various time points post-injury for comparison with baseline pre-injury and sham measurements, the two-sample t test was applied with adjustment for multiple testing by false discovery rate (FDR) approach. In addition, a linear mixed-effects model with random slope was used to perform a longitudinal analysis to determine whether NfL increases over time in each group. This model takes into account the within-subject correlation due to repeated measures by including subject-specific random effect. Associations between histological outcomes and serum NfL were determined using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Linear regression was used to examine associations between multiple histological outcomes and serum NfL measurements.

Results

Following the head rotational acceleration model of concussion in swine, all animals recovered rapidly upon withdrawal of isoflurane consistent with prior detailed descriptions of the relationship between the model kinematics and neurological recovery [100]. Within 1–2 h, animals were fully conscious and alert, mental status was unaltered and normal feeding and drinking behaviors resumed. At 24–48 h following recovery from anesthesia, consistent with a clinical presentation of mild TBI, no animals displayed evidence of overt focal neurological deficit or cranial nerve dysfunction where possible to observe. Specifically, animals displayed normal posture, tone and gait with normal mobilization on all 4 limbs. Response to touch was appropriate, indicative of an absence of overt sensory deficit. Although the number of shams was small, there was no difference between injured and sham animals in the duration between withdrawal of anesthesia and return of consciousness assessed between 30 min and 1 h following injury (TTest p = 0.9).

Serum NfL is increased at multiple time points following experimental mTBI when compared with pre-injury and sham measurements

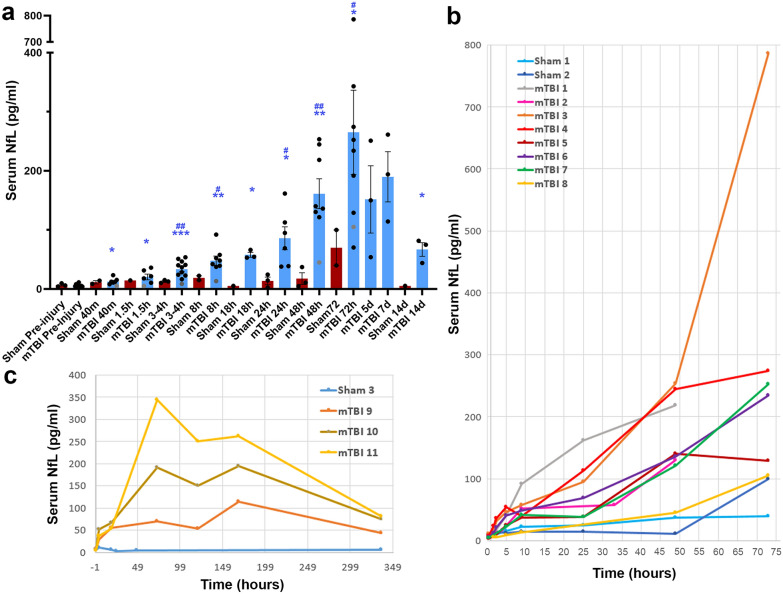

Significant increases in NfL were observed following experimental mTBI when compared with baseline pre-injury measurements at 40 min (n = 6; FDR adjusted p = 0.012), 1.5 h (n = 5; FDR adjusted p = 0.012), 3–4 h (n = 10; FDR adjusted p = 0.0002), 8 h (n = 7; FDR adjusted p = 0.0021), 18 h (n = 3; FDR adjusted p = 0.012), 1 day (n = 6; FDR adjusted p = 0.012), 2 days (n = 7; FDR adjusted p = 0.001), 3 days (n = 8; FDR adjusted p = 0.012), and 14 days (n = 3; FDR adjusted p = 0.049) post-injury (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Temporal Serum NfL Measurements Following mTBI. a Serum NfL measurements for each time point measured in injured versus sham animals. *Denotes difference from baseline (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) using T Test with adjustment for FDR. Note one animal did not have baseline serum NfL data and thus could not be included in this analysis. Individual data points for this animal are shown in gray. #Denotes difference from sham. (#p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01) using T Test with adjustment for FDR. b, c Serial NfL measurements in individual animals over time in those with survival of 48 or 72 h (b) and 2 weeks (c)

In addition to baseline sampling prior to mTBI, serial samples from additional sham animals were examined with survival time points of 72 h (n = 2) and 14d (n = 1). Levels of serum NfL in sham animals were consistently lower than that observed in injured animals and were significantly different at 3–4 h (FDR adjusted p = 0.0027), 8 h (FDR adjusted p = 0.022), 24 h (FDR adjusted p = 0.022), 2 days (FDR adjusted p = 0.0027) and 3 days post injury (FDR adjusted p = 0.046) (Fig. 1a). Notably, while formal statistical analysis was not possible at the 14 day time point, injured animals demonstrated serum NfL levels 8–14 times greater than the sham animal.

Peak elevations of serum NfL occurred 3 days following experimental mTBI and follows a biphasic distribution

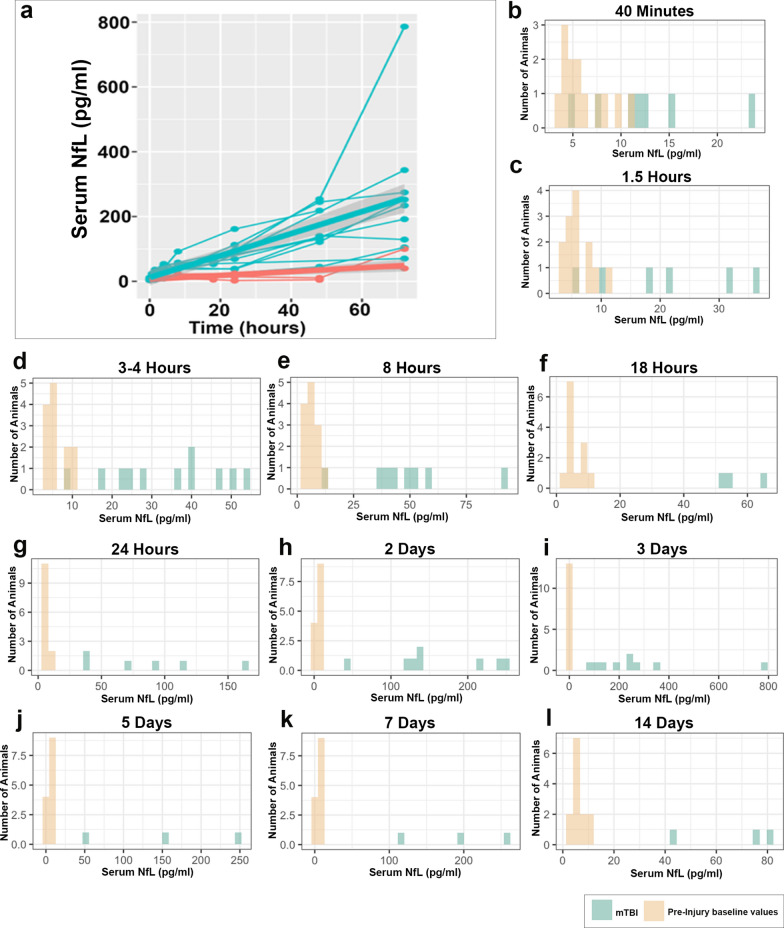

Serum NfL over time for individual animals is shown in Fig. 1b, c. While increases in serum NfL were observed as early as 40 m following mTBI, the maximal levels of serum NfL occurred at 3 days post-injury. We performed additional longitudinal analyses using a linear mixed-effects model in this period to examine the change in serum NfL over time by group (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, the results indicate that the serum NfL increases over time for both injured and sham groups (p = 0.0093). Indeed, a slight increase over time can be seen in the temporal course for individual sham animals (Figs. 1b, 2a). However, the rate of increase differs significantly between the two groups over this period (p = 0.0014), with far greater increases over time observed in injured animals. In addition, Fig. 2b–l shows the range of individual values at each time point in injured animals versus baseline values, with complete separation observed after 8 h post-injury.

Fig. 2.

Range of Serum NfL Levels Over Time Following mTBI. a Serum NfL in individual injured animals to 3 days post-injury (blue) and shams (red) with linear mixed effects model with random slope demonstrating increasing differences between mTBI and sham over time. b–l Range of serum NfL levels at each time point post-mTBI in comparison with all baseline measurements (mTBI and sham). It can be observed that serum NfL measurements completely separate from the baseline measurements after 8 h following mTBI

Interestingly, in all 3 animals surviving to 14 days post-mTBI, serum NfL was noted to decrease between days 3 and 5 before displaying a subsequent increase between days 5–7, followed by a further decline at 14d (Fig. 1c). This biphasic pattern was present regardless of the magnitude of serum NfL elevations.

Injured axons are an important source of serum NfL elevations following experimental mTBI

On gross neuropathological examination, all but 2 mTBI animals had normal appearing brains that were indistinguishable from shams (Fig. 3a–c). Specifically, consistent with clinical concussion there was no evidence of any focal pathology, including hemorrhage. In the remaining 2 animals (72 h survival) trace subdural and subarachnoid blood was observed in the posterior fossa (< ~ 1 ml) without any appreciable mass effect. In all cases, the brain hemispheres were symmetrical with no evidence of brain swelling or raised intracranial pressure (ICP). Microscopic examination of H&E stained sections examined every 5 mm through the entire rostro-caudal extent of the brain confirmed an absence of any significant focal pathology, or ischemic change in any animals. In 2 animals (72 h survival), there was just a single microhemorrhage (< ~ 20 red blood cells) observed in the frontal cortex and cerebellum, respectively.

Axonal pathology as identified via both APP and NfL IHC was observed across the spectrum of survival from 48 h to 2 weeks post-injury (Fig. 3d,f–m). This contrasted with sham animals where axonal pathology was either absent or very minimal as identified using either marker (Fig. 3e). Consistent with extensive, previous characterization of the model [12, 36, 37, 54, 70, 83, 84], IHC specific for APP revealed swollen and morphologically altered axons consistent with transport-interruption and was indistinguishable from that observed in human DAI [1–3, 23, 24, 34, 80]. Specifically, APP positive injured axonal profiles had complex morphologies including varicose swellings, often with multiple points of transport interruption along the length of an individual axon (Fig. 3j). In addition, large diameter spheroids were observed, which may represent more complete transport interruption at disconnected axon terminals (Fig. 3k).

At all survival time points examined, APP immunoreactive axonal pathology was observed across all brain levels in a stereotyped multifocal distribution consistent with biomechanical forces, as previously described in detail [36]. Specifically, this frequently involved regions of anatomic or structural interfaces including the grey-white matter interface, perivascular regions and the periventricular white matter. Hemispheric asymmetry in the distribution of APP immunoreactive axonal pathology was observed, consistent with a biomechanical etiology due to rotation toward the left side in the coronal plane.

NfL staining also revealed swollen axonal profiles consistent with interruption of axonal transport (Fig. 3k–m). This is consistent with previous descriptions using other NfL specific antibodies in swine and other TBI models, as well as in human post-mortem tissue [18, 26, 63, 102]. Notably, as expected, immunoreactivity for NfL was also present in a subset of neuronal somata, axons and dendrites with a normal morphology in both sham and injured animals (Fig. 4a, b). As such, visualization of small, more subtle swellings is limited by the high degree of baseline staining within axons. Nonetheless, following injury, in addition to axons with a normal appearance, NfL IHC revealed varicose swellings and disconnected terminal axonal bulbs in degenerating axons in a distribution consistent with that identified using APP IHC.

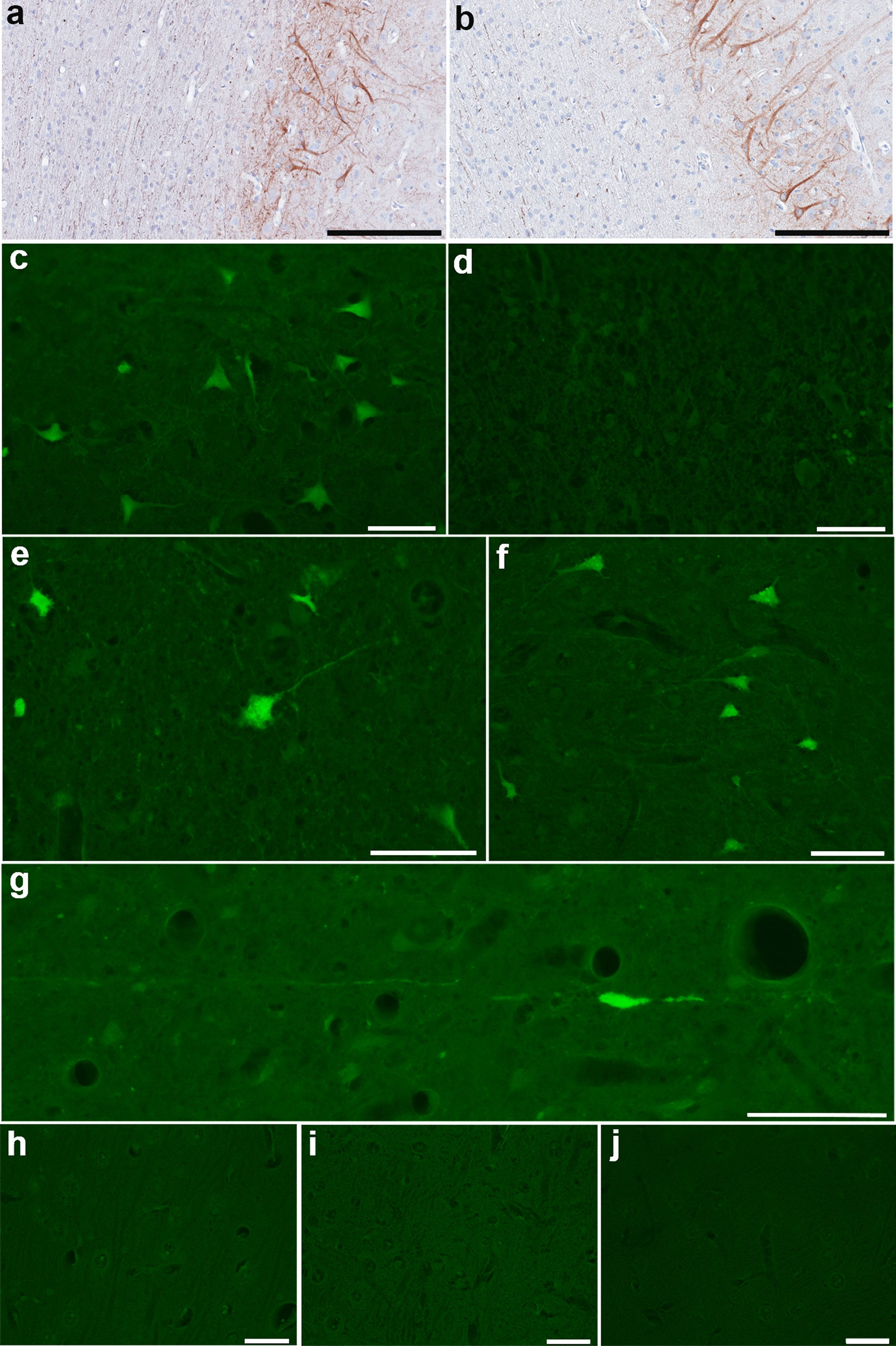

Fig. 4.

NfL and FJC Staining of Neuronal Somata. a, b NfL immunoreactivity in neuronal somata and dendrites with normal morphologies within deeper layers of cortex as well as axons in regions of normal white matter in sham animal (a) and at 72 h post-mTBI (b). Fluoro-Jade C fluorescent staining observed in (c) positive control tissue from the cortex surrounding a focal contusion at 48 h post-injury. d Negative control section where the same region of tissue underwent identical treatment absent the application of FJC. e, f Isolated clusters of FJC positive neurons observed in just 2 of all animals examined following mTBI including in the perirhinal cortex at 72 h post-injury (e) and the somatosensory cortex at 48 h post-injury (f). g Representative example of an FJC + axon with varicose swelling in the thalamus at 2 weeks post-mTBI. h–j Representative examples showing an absence of any FJC positive staining in the somatosensory cortex of a sham animal (h) and at 72 h post-mTBI (i), as well the motor cortex at 2 weeks post-mTBI (j). All scale bars 20 µm

In contrast, NfL immunoreactive neuronal somata displayed normal morphologies without any overt degenerative features, indicating that degeneration of axons is the most likely pathology contributing to serum NfL elevations (Fig. 4b). As further confirmation, serial sections stained with Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) failed to reveal neuronal somata with positive staining in all but 2 animals (Fig. 4e–j). Specifically, in one animal (48 h survival) there was a single small cluster of 25 FJC + neurons in the dorsolateral somatosensory cortex (mTBI-1; Fig. 4f). In the second animal (72 h survival) there were 3 small clusters of neurons in the right somatosensory cortex (11 cells), inferior temporal gyrus (9 cells) and perirhinal cortex (89 cells) (mTBI-4; Fig. 4e). Notably these animals did not display considerably greater elevations in serum NfL. Together these data indicate that in this model, active degeneration of neuronal somata was not a major contributor to serum biomarker levels, and injured axons likely serve as the primary source of serum NfL.

Interestingly, swollen axons with an injured morphology were occasionally FJC positive (Fig. 4g), even in the absence of any positive neuronal soma within the same animal. This was most commonly observed at the latest survival time point examined (2 weeks).

Serum NfL does not correlate with the extent of axonal pathology

Quantification of the number of axonal profiles per unit area across all 5 whole brain coronal sections was performed for each animal to determine any correlation with serum NfL levels. Interestingly, regardless of the duration of survival, there was no significant correlation between the serum NfL measurements at the study endpoint and the extent of either APP + (r = 0.028, n = 11, p = 0.93) or NfL + (r = 0.16, n = 11, p = 0.65) axonal pathology.

Furthermore, the extent of both APP + and NfL + axonal pathology at 72 h post-mTBI (the time when maximal pathology is observed) was not significantly associated with serum NfL measured at multiple time points (Table 1). Thus, while degenerating axons are the likely source of serum NfL, the extent of axonal pathology, alone, did not correlate with the degree of serum NfL elevation, suggesting additional factors play an important role in NfL dynamics in blood.

Table 1.

Associations between serum NfL over time and axonal pathology at 3 days post-injury

| Timepoint Post-mTBI serum measurement | APP + axonal pathology | NfL + axonal pathology | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s r | p value | Pearson’s r | p value | |

| 40 min | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.59 | 0.30 |

| 1.5 h | 0.65 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.56 |

| 3–4 h | 0.68 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.39 |

| 8 h | 0.09 | 0.87 | −0.13 | 0.81 |

| 24 h | 0.67 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.52 |

| 2 Days | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.66 |

| 3 Days | −0.79 | 0.88 | −0.45 | 0.37 |

No significant associations were observed between extent of APP or NfL immunoreactive axonal pathology identified histologically at the study endpoint (3 days post-injury) and serum NfL measured at various time points determined using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient

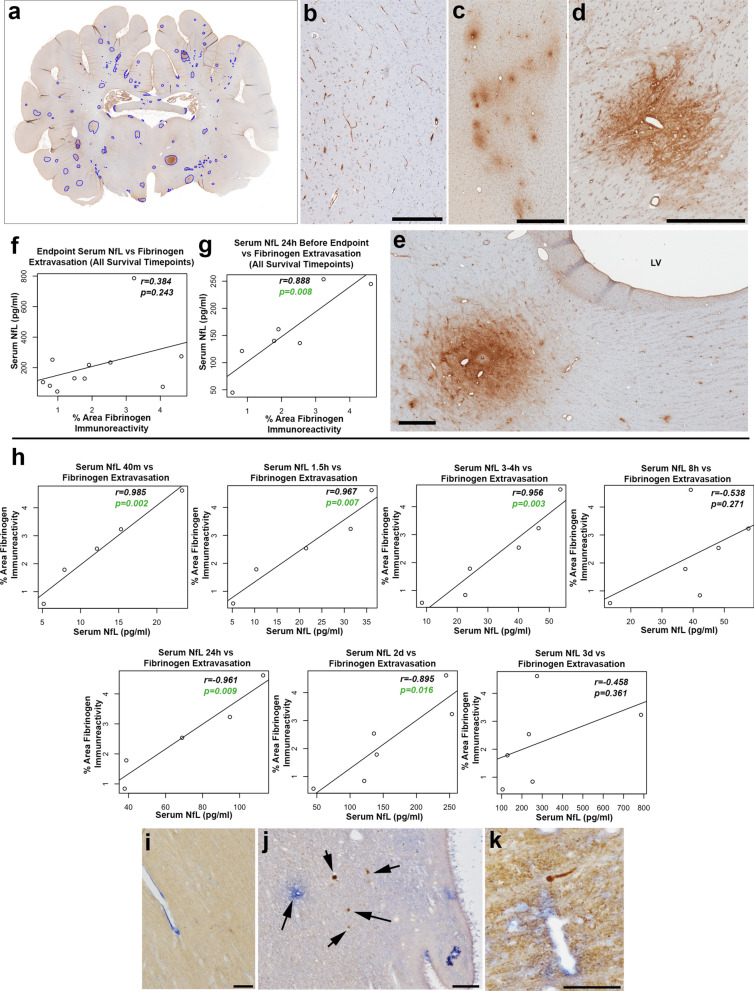

Blood–brain barrier permeability contributes to serum NfL dynamics

Consistent with previous detailed characterization of BBB permeability in this model [37], multifocal fibrinogen extravasation into the brain parenchyma was observed following a single mTBI. Perivascular fibrinogen immunoreactivity was observed in both white and gray matter in injured animals, but only minimally in shams (Fig. 5a–e). Mapping of fibrinogen extravasation in multiple whole-brain coronal sections revealed BBB permeability in a distribution consistent with a biomechanical etiology at structural interfaces including the gray-white interface, periventricular regions, subpial zones, and interfacing cell layers of the hippocampus. Notably, double immunoenzymatic labelling revealed injured NfL immunoreactive axons within regions where extravasated fibrinogen was also present, particularly within the white matter adjacent to the lateral ventricles (Fig. 5i–k).

Fig. 5.

Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability and Serum NfL. a Representative annotated map of fibrinogen extravasation at 72 h following mTBI. b Sham animals showing fibrinogen immunoreactivity only within the intravascular compartment. c Multiple foci of extravasated fibrinogen in the white matter close to the gray-white interface of the superior frontal gyrus 72 h following mTBI. d Large focus of extravasated fibrinogen in the midbrain at 72 h after mTBI. e Focus of extravasated fibrinogen adjacent to the lateral ventricle 2 weeks following mTBI. f, g Graphs showing correlations between extravasated fibrinogen determined via histological assessment and serum NfL at the endpoint (f) and 24 h prior to the endpoint (g) in all animals regardless of survival group. h Graphs showing correlations between serum NfL measured at different time points post-injury and extravasated fibrinogen determined via histological assessment in animals with a survival of 72 h. i–k Multi-immunoenzymatic labelling for NfL (brown) and fibrinogen (blue). Note the absence of swollen NfL profiles and fibrinogen confined to the intravascular compartment in a sham animal (i). In contrast, representative examples show NfL immunoreactive swollen axonal profiles in close proximity to regions of extravasated fibrinogen within (j) the periventricular region of the lateral ventricle at 72 h following mTBI and k the corpus callosum at 48 h following mTBI. Scale Bars: B: 300 µm, C–E: 500 µm, I–K: 100 µm

There was no significant association between the extent of fibrinogen extravasation and serum NfL measured at the study endpoint (regardless of survival time) (r = 0.38, n = 11, p = 0.24) (Fig. 5f). However, serum NfL measured 24 h before the endpoint (regardless of survival time) was strongly associated with the extent of fibrinogen extravasation determined histologically (r = 0.89, n = 7, p = 0.008) (Fig. 5g).

Moreover, the extent of fibrinogen extravasation observed histologically at 72 h post-mTBI was strongly associated with the level of serum NfL measured at 40 m (r = 0.99, p = 0.002), 1.5 h (r = 0.97, p = 0.007), 3–h (r = 0.96, p = 0.003), 24 h (r = 0.96, p = 0.009) and 2 days (r = 0.89, p = 0.016) post-injury (all n = 5–6) (Fig. 5h).

Finally, where sufficient numbers of animals permitted statistical evaluation, linear regression analyses did not reveal any significant association between serum NfL measurements and the extent of APP + pathology or NfL + pathology when considered together with fibrinogen extravasation at 72 h survival (all p > 0.05).

Discussion

Using a gyrencephalic and biomechanically-relevant model of mTBI induced via head rotational acceleration, we provide characterization of the temporal dynamics of serum NfL with parallel examination of the underlying neuropathologies. Increased serum NfL was observed acutely after injury with elevations above baseline measurements persisting for at least 2 weeks post-injury. Interestingly, while injured axons were revealed as the source of serum NfL, the extent of axonal pathology did not correlate with the amount of NfL in serum. In contrast, BBB permeability, identified histologically as extravasated fibrinogen, correlated strongly with serum NfL levels measured at multiple time points. Together these data demonstrate complex temporal dynamics and histological correlates of serum NfL that are critical for informing optimal sampling times and guiding appropriate interpretation of their pathological significance.

As an important constituent of neurons, and axons in particular, neurofilaments provide necessary structural support and may have complex functional interactions with other proteins and organelles [104]. Notably, low levels of NfL are detected in the blood of healthy individuals [19], possibly due to basal physiologic release of NfL into the interstitial fluid (ISF) for degradation. However, the dynamics affecting the amount of NfL that ultimately circulates in blood under both normal and pathophysiological conditions are complex and incompletely understood.

Traumatic injury to the axonal cytoskeletal and resultant transport interruption drives the accumulation of neurofilaments within tortuous swellings at points of mechanical damage along the axon length [26, 36, 50]. Eventual axonal disconnection and downstream Wallerian degeneration likely results in the expulsion of these large reservoirs of protein into the ISF. Notably, NfL can also be observed within specific subpopulations of cortical neuronal somata under normal conditions and, in theory, could also expel NfL into the ISF in the event that they degenerate. Here we show serum elevations of NfL in a clinically-relevant model of concussion, with axonal pathology in the absence of significant neuronal somatic degeneration or confounding severe pathologies including hemorrhage, ischemia or significant brain swelling. These data serve as important confirmation that axonal degeneration, alone, can serve as a source of NfL detectable in blood following mTBI.

The extent of axonal disconnection at any given time is therefore likely to be an important factor in determining the concentration of NfL in the brain ISF. However, here we show that the amount of NfL in blood at the study endpoint was not strongly associated with the extent of axonal pathology measured histologically using both APP and NfL as distinct immunohistochemical markers. This may be explained, in part, by the metrics used to assess axonal pathology. Specifically, APP and NfL IHC allow for the identification of axonal swellings secondary to transport interruption [35]. Yet previous work by our group and others has shown that different immunohistochemical markers, including APP and NfL, can identify both overlapping and distinct populations of injured axons [36, 86]. Thus, any one marker may not reveal the entire population of degenerating axons at a given time. Nonetheless, we selected to examine APP as the gold standard neuropathological marker of axonal pathology [23, 80]. Moreover, of various established markers of axonal pathology, APP has been shown to identify the greatest proportion of injured axons, including in this model [36]. While release from protein-rich axon swellings is presumed to be an abundant source of NfL in the ISF, it remains possible that NfL is also released by degenerating axons without significant swelling that remain undetected by transport-based markers. A more comprehensive analysis of the various histological outcomes across specific survival time points may allow for more detailed associations between serum NfL and the nature and evolution of pathological outcomes over time.

Alternatively, it may be that the extent of NfL in serum simply does not closely reflect the extent of axonal pathology by virtue of the complex dynamics involved in the clearance of NfL from the brain parenchyma. One clearance route is via the direct movement of NfL through the BBB to the systemic circulation, the rate of which may be influenced by the extent of pathological BBB disruption. This is of particular relevance following mTBI where pathological permeability of the BBB is increasingly recognized as a consequence of injury from both clinical neuroimaging studies [59, 99, 103] and preclinical data, including the model described here [37]. Interestingly, we demonstrate that the level of serum NfL measured at multiple time points correlates with the extent of histologically-identified extravasated fibrinogen, as an established marker of BBB permeability [5, 11, 28, 42, 44, 46, 71, 93, 95]. These data suggest that BBB function may be an important contributor to serum NfL dynamics in mTBI. This finding is in contrast to a recent report that failed to demonstrate any association between BBB permeability and serum NfL in irradiated mice or human samples where CSF/serum albumin ratio was determined [38]. However, the pathophysiological nature of both neuronal / axonal damage and BBB disruption may not be directly comparable to that occurring following mTBI.

It is important to note that the steady state of fibrinogen in the brain parenchyma is also determined by how rapidly it is cleared. Thus, fibrinogen extravasation observed histologically reflects cumulative leakage over a given period, and may in part explain why there was such robust correlation with serum NfL measured over the temporal course of the studies. Experiments utilizing injected tracers to precisely measure BBB opening at specific time points are warranted to permit more detailed exploration of the role of BBB permeability in temporal biomarker dynamics.

Curiously, slight increases in serum NfL were also observed following sham procedures in the absence of axonal pathology on histological examination. This is potentially explained by a degree of anesthesia-induced BBB opening, which has previously been reported with administration of isoflurane [91]. Minimal fibrinogen extravasation was also observed histologically in shams as described previously [37]. In particular, one sham animal showed a more notable increase at the study endpoint, at which time anesthesia is also administered. Levels of NfL in serum nonetheless remained significantly lower than in injured animals. These data highlight the importance of detailed characterization of sham animals to determine whether anesthetic agents alone contribute to biomarker changes in preclinical models.

An additional important route by which NfL may enter the circulation is via the CSF. While there have been considerable advancements in understanding the complex physiology of ISF-CSF fluid dynamics in recent years, the extent to which this is a primary route by which NfL enters the blood is not understood. This may include perivascular/glymphatic pathways or convective bulk flow with subsequent movement to the peripheral circulation via the arachnoid granulations or perineural spaces and lymphatics [48, 65]. Notably, strong correlations between the extent of NfL in CSF and serum have been reported in various disease states including TBI [38, 40], and a recent study examining a rodent model of TBI suggests transport via the glymphatic system may be an important route for other protein biomarkers [65]. While not examined here specifically, the normal or aberrant function of other clearance mechanisms may be a further contributing factor in serum biomarker dynamics. Notably, reports suggest TBI may have direct pathophysiological effects on ISF-CSF pathways, including glymphatic function [17, 31], although this has yet to be extensively examined in mTBI. Interestingly, the recently described subarachnoid lymphatic-like membrane (SYLM) has been identified as a distinct 4th meningeal layer that plays an important role in CSF transport and could potentially be disrupted by traumatic injury [57, 64]. Thus, serum NfL levels may be determined, in part, by the spatial relationship between axonal pathology and the local function of the various clearance systems. Indeed, we frequently observed injured NfL immunoreactive axons in close proximity with fibrinogen extravasation from BBB opening. Finally, the rate of degradation of NfL within the various fluid compartments, including its half-life in peripheral blood, will further influence serum concentration at any given time. The assessment of BBB permeability, ISF-CSF dynamics and other clearance mechanisms in parallel may provide valuable information to aid interpretation of any individual biomarker finding. Moreover, the recognition that BBB permeability contributes to the serum dynamics of NfL may have implications for its utility in other disease states.

With respect to the obvious complexity of these dynamics, we nonetheless observed a stereotyped pattern in temporal serum NfL measurements. Specifically, peak levels of serum NfL were detected at ~ 3 days after injury regardless of the magnitude of the concentrations, suggesting this may be an optimal time to detect pathological change, at least in mild injury without complicating pathologies. In addition, levels above baseline were detectable for at least 2 weeks after mTBI and occurred in the presence of ongoing axon degeneration observed histologically. Given that DAI is a known determinant of outcome following severe forms of TBI [56, 94], and perhaps mTBI [87, 105], it will be of interest to determine whether the duration of serum NfL elevation is of potential prognostic value. Interestingly, in all animals survived to 14 days post-injury, a possible biphasic distribution of NfL elevation was observed with a peak at 3 days followed by a subsequent decline and secondary increase at ~ 7 days. While just 3 animals were examined at these time points, the pattern was curiously consistent regardless of the magnitude of serum NfL elevations and may reflect specific time-dependent pathophysiologic processes affecting serum NfL dynamics. Notably, similar biphasic changes in BBB function have been described following a rodent model of TBI with speculation that inflammation may be a contributing factor [8]. However, more detailed analyses of serum NfL across a greater number of animals within this particular survival period will be important to further delineate the nature and consistency of changes. The examination of pathological outcomes within this time window may also permit identification of the mechanisms driving barrier opening that ultimately contribute to serum NfL fluctuations.

The mTBI model described produced consistent detectable elevations in serum NfL as might be expected in a model where controlled biomechanics of injury produce a specific pathological outcome within a narrow range of severity. Importantly, human mTBI is likely far more heterogeneous, with considerable variability in the relative extent and distribution of the multiple pathologies capable of influencing serum biomarker concentrations. Indeed, this may contribute to the wide range of serum NfL values reported following human mTBI and in participants of contact sports [6, 52, 60–62, 78, 79, 97]. In addition, here only female swine were examined, and potential sex differences in the nature and extent of pathology, or the pathophysiological processes governing biomarker dynamics, will be important to explore. Nonetheless, these data provide important information as to the specific underlying pathologies that contribute to the magnitude of serum NfL elevations following mTBI that will be critical for translation.

Abbreviations

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- DAI

Diffuse axonal injury

- DAB

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FDR

False discovery rate

- FJC

Fluoro-Jade C

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- ICP

Intracranial pressure

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- ISF

Interstitial fluid

- LLD

Lower limit of detection

- LLQ

Lower limit of quantification

- Mtbi

Mild traumatic brain injury

- NfL

Neurofilament light

- NBF

Neutral buffered formalin

Author contributions

VEJ and JDA contributed to study design, data analyses and interpretation, and manuscript preparation. DHS and RDA contributed to data interpretation and preparation of the manuscript. DKC contributed to preclinical TBI modelling, RX and JF contributed to statistical analyses. DCH contributed to histological staining and analyses. CL contributed to biomarker measurement and analyses.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01-NS123034 (VJ), NIH/NINDS training grant T32NS043126 (JDA), US Department of Defense W81XWH-19-1-0861 and NIH U01-NS114140 (RDA), The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation (DHS), and the PA Consortium on Traumatic Brain Injury 4100077083 (DHS).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All in vivo experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Ramon Diaz-Arrastia has consulted with MesoScale Discoveries and BrainBox Solutions, Inc. Dr. Douglas Smith has consulted with Abbott Laboratories.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adams JH, Doyle D, Ford I, Gennarelli TA, Graham DI, McLellan DR (1989) Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology 15:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams JH, Graham DI, Gennarelli TA, Maxwell WL (1991) Diffuse axonal injury in non-missile head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 54:481–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams JH, Graham DI, Murray LS, Scott G (1982) Diffuse axonal injury due to nonmissile head injury in humans: an analysis of 45 cases. Ann Neurol 12:557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Nimer F, Thelin E, Nystrom H, Dring AM, Svenningsson A, Piehl F, Nelson DW, Bellander BM (2015) comparative assessment of the prognostic value of biomarkers in traumatic brain injury reveals an independent role for serum levels of neurofilament light. PLoS ONE 10:e0132177. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez JI, Saint-Laurent O, Godschalk A, Terouz S, Briels C, Larouche S, Bourbonniere L, Larochelle C, Prat A (2015) Focal disturbances in the blood-brain barrier are associated with formation of neuroinflammatory lesions. Neurobiol Dis 74:14–24. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asken BM, Yang Z, Xu H, Weber AG, Hayes RL, Bauer RM, DeKosky ST, Jaffee MS, Wang KKW, Clugston JR (2020) Acute effects of sport-related concussion on serum glial fibrillary acidic protein, ubiquitin C-Terminal hydrolase L1, total Tau, and neurofilament light measured by a multiplex assay. J Neurotrauma 37:1537–1545. 10.1089/neu.2019.6831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagnato S, Grimaldi LME, Di Raimondo G, Sant’Angelo A, Boccagni C, Virgilio V, Andriolo M (2017) Prolonged cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chain increase in patients with post-traumatic disorders of consciousness. J Neurotrauma 34:2475–2479. 10.1089/neu.2016.4837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baskaya MK, Rao AM, Dogan A, Donaldson D, Dempsey RJ (1997) The biphasic opening of the blood-brain barrier in the cortex and hippocampus after traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurosci Lett 226:33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumbergs PC, Scott G, Manavis J, Wainwright H, Simpson DA, McLean AJ (1994) Staining of amyloid precursor protein to study axonal damage in mild head injury. Lancet 344:1055–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumbergs PC, Scott G, Manavis J, Wainwright H, Simpson DA, McLean AJ (1995) Topography of axonal injury as defined by amyloid precursor protein and the sector scoring method in mild and severe closed head injury. J Neurotrauma 12:565–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridges LR, Andoh J, Lawrence AJ, Khoong CH, Poon WW, Esiri MM, Markus HS, Hainsworth AH (2014) Blood-brain barrier dysfunction and cerebral small vessel disease (arteriolosclerosis) in brains of older people. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73:1026–1033. 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne KD, Chen XH, Meaney DF, Smith DH (2011) Mild traumatic brain injury and diffuse axonal injury in swine. J Neurotrauma 28:1747–1755. 10.1089/neu.2011.1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buki A, Farkas O, Doczi T, Povlishock JT (2003) Preinjury administration of the calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 attenuates traumatically induced axonal injury. J Neurotrauma 20:261–268. 10.1089/089771503321532842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buki A, Koizumi H, Povlishock JT (1999) Moderate posttraumatic hypothermia decreases early calpain-mediated proteolysis and concomitant cytoskeletal compromise in traumatic axonal injury. Exp Neurol 159:319–328. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7139S0014-4886(99)97139-X[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buki A, Okonkwo DO, Povlishock JT (1999) Postinjury cyclosporin A administration limits axonal damage and disconnection in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 16:511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buki A, Siman R, Trojanowski JQ, Povlishock JT (1999) The role of calpain-mediated spectrin proteolysis in traumatically induced axonal injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58:365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen J, Wright DK, Yamakawa GR, Shultz SR, Mychasiuk R (2020) Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury alters glymphatic clearance rates in limbic structures of adolescent female rats. Sci Rep 10:6254. 10.1038/s41598-020-63022-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christman CW, Salvant JB Jr, Walker SA, Povlishock JT (1997) Characterization of a prolonged regenerative attempt by diffusely injured axons following traumatic brain injury in adult cat: a light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical study. Acta Neuropathol 94:329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Disanto G, Barro C, Benkert P, Naegelin Y, Schadelin S, Giardiello A, Zecca C, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Leppert D et al (2017) Serum Neurofilament light: a biomarker of neuronal damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 81:857–870. 10.1002/ana.24954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eierud C, Craddock RC, Fletcher S, Aulakh M, King-Casas B, Kuehl D, LaConte SM (2014) Neuroimaging after mild traumatic brain injury: review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage Clinical 4:283–294. 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, Di Filippo M, Parnetti L, Zetterberg H (2019) Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 90:870–881. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gennarelli TA, Thibault LE, Adams JH, Graham DI, Thompson CJ, Marcincin RP (1982) Diffuse axonal injury and traumatic coma in the primate. Ann Neurol 12:564–574. 10.1002/ana.410120611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentleman SM, Nash MJ, Sweeting CJ, Graham DI, Roberts GW (1993) Beta-amyloid precursor protein (beta APP) as a marker for axonal injury after head injury. Neurosci Lett 160:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gentleman SM, Roberts GW, Gennarelli TA, Maxwell WL, Adams JH, Kerr S, Graham DI (1995) Axonal injury: a universal consequence of fatal closed head injury? Acta Neuropathol 89:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerberding JL BS (2003) Report to congress ontraumatic brain injury in the United States: steps to prevent a serious public health problem. National center for injuy prevention and control, centers for disease control and prevention. City

- 26.Grady MS, McLaughlin MR, Christman CW, Valadka AB, Fligner CL, Povlishock JT (1993) The use of antibodies targeted against the neurofilament subunits for the detection of diffuse axonal injury in humans. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 52:143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham NSN, Zimmerman KA, Moro F, Heslegrave A, Maillard SA, Bernini A, Miroz JP, Donat CK, Lopez MY, Bourke N et al (2021) Axonal marker neurofilament light predicts long-term outcomes and progressive neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. Sci Transl Med. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg9922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hay JR, Johnson VE, Young AM, Smith DH, Stewart W (2015) Blood-brain barrier disruption is an early event that may persist for many years after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 74:1147–1157. 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holbourn AHS (1945) Mechanics of brain injuries. Brit Med Bull 3:147–149 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holbourn AHS (1943) Mechanics of Head Injury. The Lancet 242:438–441 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iliff JJ, Chen MJ, Plog BA, Zeppenfeld DM, Soltero M, Yang L, Singh I, Deane R, Nedergaard M (2014) Impairment of glymphatic pathway function promotes tau pathology after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci 34:16180–16193. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3020-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwata A, Stys PK, Wolf JA, Chen XH, Taylor AG, Meaney DF, Smith DH (2004) Traumatic axonal injury induces proteolytic cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channels modulated by tetrodotoxin and protease inhibitors. J Neurosci 24:4605–4613. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0515-03.200424/19/4605[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ Jr, Cantrill SV, Gean AD, Howard PK, Ghajar J, Riggio S, Wright DW, Wears RL et al (2008) Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decisionmaking in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. Ann Emerg Med 52:714–748. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson VE, Stewart JE, Begbie FD, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, Stewart W (2013) Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 136:28–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH (2013) Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 246:35–43. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Weber MT, Cullen DK, Siman R, Smith DH (2016) SNTF immunostaining reveals previously undetected axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol 131:115–135. 10.1007/s00401-015-1506-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson VE, Weber MT, Xiao R, Cullen DK, Meaney DF, Stewart W, Smith DH (2018) Mechanical disruption of the blood-brain barrier following experimental concussion. Acta Neuropathol 135:711–726. 10.1007/s00401-018-1824-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalm M, Bostrom M, Sandelius A, Eriksson Y, Ek CJ, Blennow K, Bjork-Eriksson T, Zetterberg H (2017) Serum concentrations of the axonal injury marker neurofilament light protein are not influenced by blood-brain barrier permeability. Brain Res 1668:12–19. 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kampfl A, Posmantur R, Nixon R, Grynspan F, Zhao X, Liu SJ, Newcomb JK, Clifton GL, Hayes RL (1996) mu-calpain activation and calpain-mediated cytoskeletal proteolysis following traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem 67:1575–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalil M, Teunissen CE, Otto M, Piehl F, Sormani MP, Gattringer T, Barro C, Kappos L, Comabella M, Fazekas F et al (2018) Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 14:577–589. 10.1038/s41582-018-0058-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinnunen KM, Greenwood R, Powell JH, Leech R, Hawkins PC, Bonnelle V, Patel MC, Counsell SJ, Sharp DJ (2011) White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain 134:449–463. 10.1093/brain/awq347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirk J, Plumb J, Mirakhur M, McQuaid S (2003) Tight junctional abnormality in multiple sclerosis white matter affects all calibres of vessel and is associated with blood-brain barrier leakage and active demyelination. J Pathol 201:319–327. 10.1002/path.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korley FK, Yue JK, Wilson DH, Hrusovsky K, Diaz-Arrastia R, Ferguson AR, Yuh EL, Mukherjee P, Wang KKW, Valadka AB et al (2018) Performance evaluation of a multiplex assay for simultaneous detection of four clinically relevant traumatic brain injury biomarkers. J Neurotrauma. 10.1089/neu.2017.5623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwon EE, Prineas JW (1994) Blood-brain barrier abnormalities in longstanding multiple sclerosis lesions. an immunohistochemical study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 53:625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laverse E, Guo T, Zimmerman K, Foiani MS, Velani B, Morrow P, Adejuwon A, Bamford R, Underwood N, George J et al (2020) Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light chain, but not tau, are biomarkers of sports-related mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Commun. 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu JY, Thom M, Catarino CB, Martinian L, Figarella-Branger D, Bartolomei F, Koepp M, Sisodiya SM (2012) Neuropathology of the blood-brain barrier and pharmaco-resistance in human epilepsy. Brain 135:3115–3133. 10.1093/brain/aws147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ljungqvist J, Zetterberg H, Mitsis M, Blennow K, Skoglund T (2017) Serum neurofilament light protein as a marker for diffuse axonal injury: results from a case series study. J Neurotrauma 34:1124–1127. 10.1089/neu.2016.4496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Louveau A, Smirnov I, Keyes TJ, Eccles JD, Rouhani SJ, Peske JD, Derecki NC, Castle D, Mandell JW, Lee KS et al (2015) Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature 523:337–341. 10.1038/nature14432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Margulies SS, Thibault LE, Gennarelli TA (1990) Physical model simulations of brain injury in the primate. J Biomech 23:823–836. 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90029-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marmarou CR, Walker SA, Davis CL, Povlishock JT (2005) Quantitative analysis of the relationship between intra- axonal neurofilament compaction and impaired axonal transport following diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 22:1066–1080. 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maxwell WL, Watt C, Pediani JD, Graham DI, Adams JH, Gennarelli TA (1991) Localisation of calcium ions and calcium-ATPase activity within myelinated nerve fibres of the adult guinea-pig optic nerve. J Anat 176:71–79 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCrea M, Broglio SP, McAllister TW, Gill J, Giza CC, Huber DL, Harezlak J, Cameron KL, Houston MN, McGinty G et al (2020) association of blood biomarkers with acute sport-related concussion in collegiate athletes: findings from the NCAA and department of defense CARE consortium. JAMA Netw Open 3:e1919771. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGinn MJ, Kelley BJ, Akinyi L, Oli MW, Liu MC, Hayes RL, Wang KK, Povlishock JT (2009) Biochemical, structural, and biomarker evidence for calpain-mediated cytoskeletal change after diffuse brain injury uncomplicated by contusion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68:241–249. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181996bfe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meaney DF, Smith DH, Shreiber DI, Bain AC, Miller RT, Ross DT, Gennarelli TA (1995) Biomechanical analysis of experimental diffuse axonal injury. J Neurotrauma 12:689–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miles L, Grossman RI, Johnson G, Babb JS, Diller L, Inglese M (2008) Short-term DTI predictors of cognitive dysfunction in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 22:115–122. 10.1080/02699050801888816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moen KG, Skandsen T, Folvik M, Brezova V, Kvistad KA, Rydland J, Manley GT, Vik A (2012) A longitudinal MRI study of traumatic axonal injury in patients with moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83:1193–1200. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mollgard K, Beinlich FRM, Kusk P, Miyakoshi LM, Delle C, Pla V, Hauglund NL, Esmail T, Rasmussen MK, Gomolka RS et al (2023) A mesothelium divides the subarachnoid space into functional compartments. Science 379:84–88. 10.1126/science.adc8810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niogi SN, Mukherjee P, Ghajar J, Johnson C, Kolster RA, Sarkar R, Lee H, Meeker M, Zimmerman RD, Manley GT et al (2008) Extent of microstructural white matter injury in postconcussive syndrome correlates with impaired cognitive reaction time: a 3T diffusion tensor imaging study of mild traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29:967–973. 10.3174/ajnr.A0970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Keeffe E, Kelly E, Liu Y, Giordano C, Wallace E, Hynes M, Tiernan S, Meagher A, Greene C, Hughes S et al (2020) Dynamic blood-brain barrier regulation in mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 37:347–356. 10.1089/neu.2019.6483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oliver JM, Anzalone AJ, Stone JD, Turner SM, Blueitt D, Garrison JC, Askow AT, Luedke JA, Jagim AR (2018) Fluctuations in blood biomarkers of head trauma in NCAA football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurosurg. 10.3171/2017.12.JNS172035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oliver JM, Jones MT, Kirk KM, Gable DA, Repshas JT, Johnson TA, Andreasson U, Norgren N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2016) Serum neurofilament light in American football athletes over the course of a season. J Neurotrauma 33:1784–1789. 10.1089/neu.2015.4295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pattinson CL, Meier TB, Guedes VA, Lai C, Devoto C, Haight T, Broglio SP, McAllister T, Giza C, Huber D et al (2020) Plasma biomarker concentrations associated with return to sport following sport-related concussion in collegiate athletes-a concussion assessment, research, and education (CARE) consortium study. JAMA Netw Open 3:e2013191. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pettus EH, Christman CW, Giebel ML, Povlishock JT (1994) Traumatically induced altered membrane permeability: its relationship to traumatically induced reactive axonal change. J Neurotrauma 11:507–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pla V, Bitsika S, Giannetto MJ, Ladron-de-Guevara A, Gahn-Martinez D, Mori Y, Nedergaard M, Mollgard K (2023) Structural characterization of SLYM-a 4th meningeal membrane. Fluids Barriers CNS 20:93. 10.1186/s12987-023-00500-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plog BA, Dashnaw ML, Hitomi E, Peng W, Liao Y, Lou N, Deane R, Nedergaard M (2015) Biomarkers of traumatic injury are transported from brain to blood via the glymphatic system. J Neurosci 35:518–526. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3742-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Povlishock JT, Buki A, Koiziumi H, Stone J, Okonkwo DO (1999) Initiating mechanisms involved in the pathobiology of traumatically induced axonal injury and interventions targeted at blunting their progression. Acta Neurochir Suppl 73:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Povlishock JT, Marmarou A, McIntosh T, Trojanowski JQ, Moroi J (1997) Impact acceleration injury in the rat: evidence for focal axolemmal change and related neurofilament sidearm alteration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:347–359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rabinowitz AR, Li X, McCauley SR, Wilde EA, Barnes A, Hanten G, Mendez D, McCarthy JJ, Levin HS (2015) Prevalence and predictors of poor recovery from mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 32:1488–1496. 10.1089/neu.2014.3555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roe C, Sveen U, Alvsaker K, Bautz-Holter E (2009) Post-concussion symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury: influence of demographic factors and injury severity in a 1-year cohort study. Disabil Rehabil 31:1235–1243. 10.1080/09638280802532720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ross DT, Meaney DF, Sabol MK, Smith DH, Gennarelli TA (1994) Distribution of forebrain diffuse axonal injury following inertial closed head injury in miniature swine. Exp Neurol 126:291–299. 10.1006/exnr.1994.1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ryu JK, McLarnon JG (2009) A leaky blood-brain barrier, fibrinogen infiltration and microglial reactivity in inflamed Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Cell Mol Med 13:2911–2925. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00434.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saatman KE, Abai B, Grosvenor A, Vorwerk CK, Smith DH, Meaney DF (2003) Traumatic axonal injury results in biphasic calpain activation and retrograde transport impairment in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23:34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saatman KE, Bozyczko-Coyne D, Marcy V, Siman R, McIntosh TK (1996) Prolonged calpain-mediated spectrin breakdown occurs regionally following experimental brain injury in the rat. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 55:850–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmued LC, Stowers CC, Scallet AC, Xu L (2005) Fluoro-Jade C results in ultra high resolution and contrast labeling of degenerating neurons. Brain Res 1035:24–31. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schweitzer JB, Park MR, Einhaus SL, Robertson JT (1993) Ubiquitin marks the reactive swellings of diffuse axonal injury. Acta Neuropathol 85:503–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shahim P, Gren M, Liman V, Andreasson U, Norgren N, Tegner Y, Mattsson N, Andreasen N, Ost M, Zetterberg H et al (2016) Serum neurofilament light protein predicts clinical outcome in traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 6:36791. 10.1038/srep36791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shahim P, Politis A, van der Merwe A, Moore B, Chou YY, Pham DL, Butman JA, Diaz-Arrastia R, Gill JM, Brody DL et al (2020) Neurofilament light as a biomarker in traumatic brain injury. Neurology 95:e610–e622. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shahim P, Tegner Y, Marklund N, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2018) Neurofilament light and tau as blood biomarkers for sports-related concussion. Neurology 90:e1780–e1788. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shahim P, Zetterberg H, Tegner Y, Blennow K (2017) Serum neurofilament light as a biomarker for mild traumatic brain injury in contact sports. Neurology 88:1788–1794. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sherriff FE, Bridges LR, Sivaloganathan S (1994) Early detection of axonal injury after human head trauma using immunocytochemistry for beta-amyloid precursor protein. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 87:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Siman R, Giovannone N, Hanten G, Wilde EA, McCauley SR, Hunter JV, Li X, Levin HS, Smith DH (2013) Evidence that the blood biomarker SNTF predicts brain imaging changes and persistent cognitive dysfunction in Mild TBI patients. Front Neurol 4:190. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singleton RH, Stone JR, Okonkwo DO, Pellicane AJ, Povlishock JT (2001) The immunophilin ligand FK506 attenuates axonal injury in an impact-acceleration model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 18:607–614. 10.1089/089771501750291846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith DH, Chen XH, Xu BN, McIntosh TK, Gennarelli TA, Meaney DF (1997) Characterization of diffuse axonal pathology and selective hippocampal damage following inertial brain trauma in the pig. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:822–834 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith DH, Nonaka M, Miller R, Leoni M, Chen XH, Alsop D, Meaney DF (2000) Immediate coma following inertial brain injury dependent on axonal damage in the brainstem. J Neurosurg 93:315–322. 10.3171/jns.2000.93.2.0315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Staal JA, Dickson TC, Gasperini R, Liu Y, Foa L, Vickers JC (2010) Initial calcium release from intracellular stores followed by calcium dysregulation is linked to secondary axotomy following transient axonal stretch injury. J Neurochem 112:1147–1155. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stone JR, Singleton RH, Povlishock JT (2001) Intra-axonal neurofilament compaction does not evoke local axonal swelling in all traumatically injured axons. Exp Neurol 172:320–331. 10.1006/exnr.2001.7818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strauss SB, Kim N, Branch CA, Kahn ME, Kim M, Lipton RB, Provataris JM, Scholl HF, Zimmerman ME, Lipton ML (2016) Bidirectional changes in anisotropy are associated with outcomes in mild traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 37:1983–1991. 10.3174/ajnr.A4851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang-Schomer MD, Johnson VE, Baas PW, Stewart W, Smith DH (2012) Partial interruption of axonal transport due to microtubule breakage accounts for the formation of periodic varicosities after traumatic axonal injury. Exp Neurol 233:364–372. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tang-Schomer MD, Patel AR, Baas PW, Smith DH (2010) Mechanical breaking of microtubules in axons during dynamic stretch injury underlies delayed elasticity, microtubule disassembly, and axon degeneration. FASEB J 24:1401–1410. 10.1096/fj.09-142844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, Xu L (2017) Traumatic brain injury-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths–United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 66:1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tetrault S, Chever O, Sik A, Amzica F (2008) Opening of the blood-brain barrier during isoflurane anaesthesia. Eur J Neurosci 28:1330–1341. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thibault L, Gennarelli TA, Margulies SS, et al. (1990) The Strain Dependent Pathophysiological Consequences of Inertial Loading on Central Nervous System Tissue. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Biomechanics of Impact Lyon, France 191–202

- 93.Tomimoto H, Akiguchi I, Suenaga T, Nishimura M, Wakita H, Nakamura S, Kimura J (1996) Alterations of the blood-brain barrier and glial cells in white-matter lesions in cerebrovascular and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Stroke 27:2069–2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vieira RC, Paiva WS, de Oliveira DV, Teixeira MJ, de Andrade AF, de Sousa RM (2016) Diffuse axonal injury: epidemiology, outcome and associated risk factors. Front Neurol 7:178. 10.3389/fneur.2016.00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Viggars AP, Wharton SB, Simpson JE, Matthews FE, Brayne C, Savva GM, Garwood C, Drew D, Shaw PJ, Ince PG (2011) Alterations in the blood brain barrier in ageing cerebral cortex in relationship to Alzheimer-type pathology: a study in the MRC-CFAS population neuropathology cohort. Neurosci Lett 505:25–30. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]