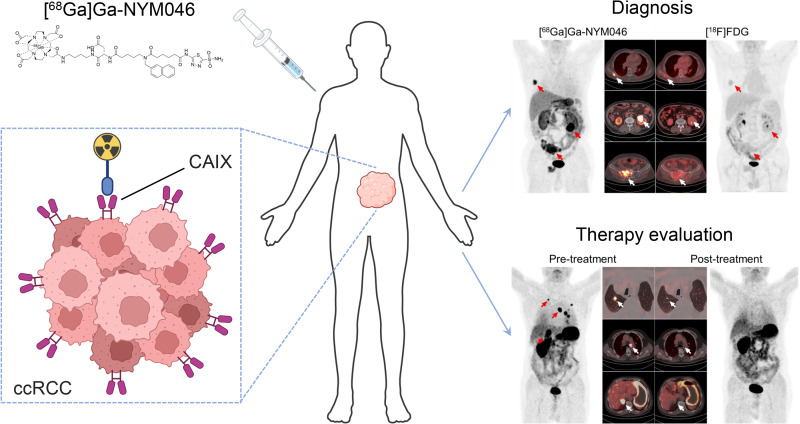

Visual Abstract

Keywords: [68Ga]Ga-NYM046, 18F-FDG, PET/CT, carbonic anhydrase IX, clear cell renal cell carcinoma

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the diagnostic efficacy of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT in animal models and patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) and to compare its performance with that of 18F-FDG PET/CT. Methods: The in vivo biodistribution of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 was evaluated in mice bearing OS-RC-2 xenografts. Twelve patients with ccRCC were included in the study; all completed paired [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT. The diagnostic efficacies of these 2 PET tracers were compared. Moreover, the positive rate of carbonic anhydrase IX in the pathologic tissue sections was compared with the SUVmax obtained by PET/CT. Results: The tumor accumulation of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 at 1 h after injection in OS-RC-2 xenograft tumor models was 7.21 ± 2.39 injected dose per gram of tissue. Apart from tumors, the kidney and stomach showed high-uptake distributions. In total, 9 primary tumors, 96 involved lymph nodes, and 147 distant metastases in 12 patients were evaluated using [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Compared with 18F-FDG PET/CT, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT detected more primary tumors (9 vs. 1), involved lymph nodes (95 vs. 92), and distant metastases (137 vs. 127). In quantitative analysis, the primary tumors’ SUVmax (median, 13.5 vs. 2.4; z = −2.668, P = 0.008) was significantly higher in [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT. Conversely, the involved lymph nodes’ SUVmax (median, 5.9 vs. 7.6; z = −3.236, P = 0.001) was higher in 18F-FDG PET/CT. No significant differences were found for distant metastases (median SUVmax, 5.0 vs. 5.0; z = −0.381, P = 0.703). Higher [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 uptake in primary tumors corresponded to higher expression of carbonic anhydrase IX, with an R2 value of 0.8274. Conclusion: [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT offers a viable strategy for detecting primary tumors, involved lymph nodes, and distant metastases in patients with ccRCC.

Renal malignancies account for 2% of the annual global tumor incidence, with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) being predominant (1). The success of treating patients depends on early diagnosis and accurate staging, which are crucial in guiding personalized therapeutic management (2,3). About 20%–30% of individuals who have undergone surgery for renal cell carcinoma are at risk of metastatic relapse (4). Such relapses can manifest in unusual sites such as the pancreas, peritoneal cavity, and intestinal tract, which are likely to be missed by routine follow-up (5,6). 18F-FDG PET/CT is a commonly used method for whole-body evaluation of tumors. Nevertheless, its performance in diagnosing primary foci of ccRCC has been disappointing, as previous metaanalyses demonstrated a sensitivity of only 62% (7). In addition, some studies revealed that 18F-FDG PET/CT faces inherent challenges in diagnosing metastatic lesions of ccRCC because of the high physiologic background activity and inflammation, with a variable sensitivity range of 63.6%–90.0% (8–10). Consequently, these limitations underscore the need to develop alternative diagnostic strategies to improve the accuracy of tumor detection.

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) belongs to the phylogenetically well-preserved carbonic anhydrase family and is induced by hypoxia, functionally related to the acidic tumor microenvironment, involved in tumor aggressiveness (11,12). Moreover, CAIX is highly expressed in nearly all cases of ccRCC, triggered by the inactivation of von Hippel–Lindau syndrome (13). By contrast, CAIX expression in adult normal tissues is relatively low, except in the stomach, bile duct epithelium, and gallbladder (14). A CAIX-targeting mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody (known as G250 or girentuximab) was first labeled with 131I and applied as an imaging agent in patients with ccRCC (15). Subsequently, 111In- or 89Zr-girentuximab entered clinical research (16–19). However, the findings from previous studies indicated that large-molecule antibodies often exhibit limited tumor penetration and slow blood clearance. Compared with large-molecule biopharmaceuticals, small-molecule targeted drugs exhibit superior characteristics in various domains, including pharmacokinetic behavior, cost, patient adherence, and ease of drug storage and transportation (20).

Here, a new small-molecule compound, NYM046, targeting CAIX was introduced. It is based on acetazolamide and features a DOTA chelating structure for 68Ga labeling. In this study, the diagnostic efficacy of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 in OS-RC-2 xenograft tumor models and patients with ccRCC was evaluated, and its application value was compared with that of 18F-FDG PET/CT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Radiopharmaceutical Preparation

NYM046 was synthesized by Shanghai Bioduro Biologics Co., Ltd., by the authors’ design. Radionuclide labeling was performed using the Morten M1 system (Sunmao Medical Technologies). In brief, 68Ga was prepared using a 68Ge/68Ga generator (Eckert & Ziegler) and 0.05 M HCl (5 mL). The eluate was added to a reaction flask containing a sodium acetate buffer (0.25 M), along with 40 μg (0.036 μmol) of the precursor, NYM046 (1 mg/mL), to achieve a mixture with a pH of 4. The mixture was heated to 100°C for 10 min and purified using a C18 Sep-Pak cartridge (Waters), with 0.5 mL of 75% ethanol solution and 5 mL of normal saline as eluents. The product, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046, was confirmed by radioactive high-performance liquid chromatography (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Small-Animal PET/CT and Blocking Study

Tumor-bearing mice were anesthetized by administration of 1.5%–2% isoflurane through an air current set at 0.5 L/min and then were intravenously injected with [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 (2.3 ± 0.1 MBq, 0.2 mL). Dynamic scanning using small-animal PET/CT followed (Super Nova) within 3 h. Small-animal PET/CT images were reconstructed using 3-dimensional ordered-subsets expectation maximization. Then, the major organs were manually outlined on the images as the region of interest. The percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) for major organs was calculated using PMOD (version 4.3; PMOD Technologies). For blocking experiments, tumor-bearing mice were administered unlabeled NYM046 (400 μg, 0.2 mL) intravenously, followed 1 h later by an intravenous injection of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 (2.1 ± 0.1 MBq, 0.2 mL), with scanning performed at 1 h after injection. Animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines established by the ethical committee of Jiangnan University.

Patient Inclusion Criteria

This study was a prospective, single-center trial to evaluate the diagnostic performance of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT in patients with primary or metastatic ccRCC. Twelve patients were ultimately enrolled, all of whom had undergone surgery or puncture biopsy of renal lesions with a confirmed diagnosis of ccRCC (Supplemental Fig. 1; supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org). The study was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the Jiangnan University affiliated hospital (LS2020003). All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05638256).

PET/CT in Patients

Each patient underwent paired [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG imaging using a PET/CT scanner (Siemens Biography 64 TruePoint). The interval between the 2 scans was less than 3 d. Scans were taken from the head to the upper femur and divided into separate head and body portions. The mean dose of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 was 129 MBq (range, 98–174 MBq) for each patient, whereas the dose of 18F-FDG was based on the patient’s weight (5.55 MBq/kg).

PET/CT Image Analysis

[68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG PET/CT images were viewed independently by 2 qualified nuclear medicine physicians. Any lesion with higher radioactivity uptake than in the surrounding normal tissue was considered positive (except for physiologic uptake). The short diameters of involved lymph nodes and the long diameters of other measurable lesions were measured according to the RECIST 1.1 standard. SUVmax was obtained by outlining the region of interest.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were accomplished using SPSS 25.0 (IBM). SUVmax data were expressed as median, first quartile, and third quartile and were compared using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Lesion numbers were assessed using the McNemar test. Statistical differences were considered significant if the P value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Chemistry and Radiolabeling

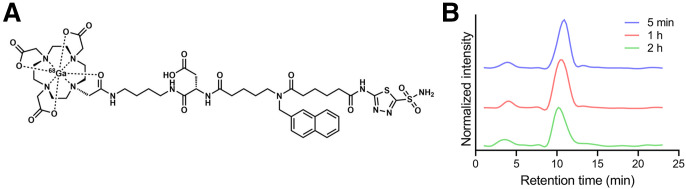

The chemical structure and characterization of NYM046 are shown in Supplemental Fig. 2. NYM046 exhibited a molecular mass of 1,118.45 g/mol and a purity of 95.74% (Supplemental Fig. 2). The chemical structure of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 is shown in Figure 1A, and its molar activity was 3.68 ± 0.83 GBq/μmol. The radiochemical purity of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 was more than 95% (Supplemental Fig. 3). Additionally, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 remained stable for more than 2 h in human serum (Fig. 1B). The binding affinity of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 to CAIX was 4.98 ± 0.50 nM (Supplemental Fig. 4). During the safety assessment, 6 mice were injected with [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 (7.4 MBq, 0.5 mL) via the tail vein, and no body weight loss was observed over 14 d (Supplemental Fig. 5).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Chemical structure of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046. (B) Stability of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 in serum on radioactive high-performance liquid chromatography analysis.

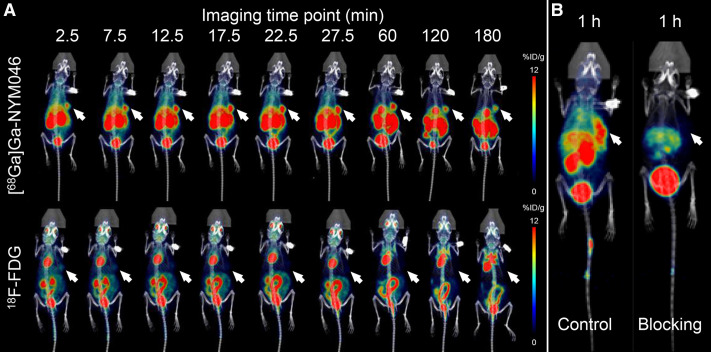

PET/CT in Animals

The radioactivity uptake of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 in OS-RC-2 xenograft tumor models peaked between 27.5 and 60 min (Fig. 2A), and the tumor accumulation at 1 h after injection was 7.21 ± 2.39 %ID/g (Supplemental Table 1). The blockade study of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 showed a decrease in tumor radioactivity uptake from 8.66 ± 2.17 %ID/g to 2.46 ± 0.67 %ID/g for 1 h (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) In vivo biodistribution imaging of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG in OS-RC-2 xenograft tumor models. (B) Representative PET/CT images of OS-RC-2 xenograft tumor models with or without unlabeled NYM046 blocking.

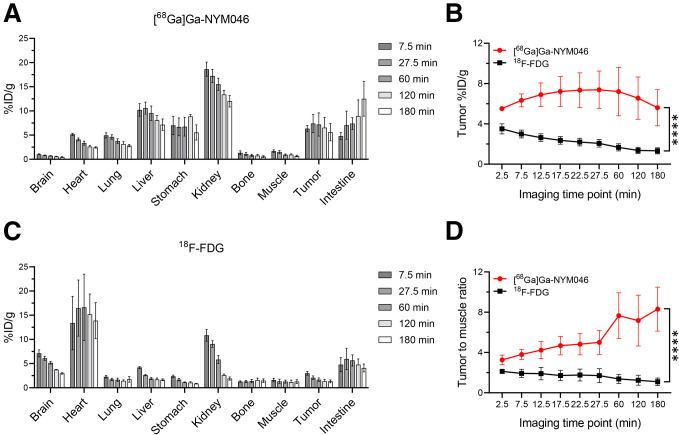

The radioactivity biodistributions of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG in the OS-RC-2 xenograft tumor models was assessed (Figs. 3A and 3C). The tumor accumulation and tumor-to-muscle ratio were significantly higher for [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT than for 18F-FDG PET/CT within 3 h (Figs. 3B and 3D).

FIGURE 3.

(A and C) Radioactivity biodistribution of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 (A) and 18F-FDG (C) in various organs in OS-RC-2 tumor model at different time points after injection. (B and D) Quantitative curves of tumor uptake (B) and contrast (D) with background tissues (tumor-to-muscle contrast). ****P < 0.0001.

Clinical PET/CT Studies in Patients with ccRCC

Patient clinical data are presented in Table 1. Twelve patients (9 male and 3 female; median age, 59 y; range, 38–81 y) who underwent paired [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG PET/CT were prospectively enrolled. No adverse reactions were observed in patients after [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT in a 2-wk follow-up period.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Included Clinical Cases

| Patient no. | SUVmax | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age (y) | Condition | Tumor location | Lesions* | [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 | 18F-FDG | |

| 1 | F | 56 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 8.2 | 1.9 |

| 2 | F | 46 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 6.2 | 2.5 |

| 3 | F | 54 | Postop | Pleura, pancreas mets | 7/0 | 4.3 (2.6, 8.9) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.4) |

| 4 | M | 67 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 3.7 | 2.3 |

| 5 | M | 63 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 13.5 | 2.9 |

| 6 | M | 38 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 11.5 | 2.6 |

| 7 | M | 59 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 13.9 | 2.2 |

| Lymph node met | 0/1 | 5.0 | 1.6 | ||||

| Lung and bone mets | 3/1 | 6.5 (4.1, 13.8) | 2.4 (1.4, 3.0) | ||||

| 8 | M | 46 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 13.9 | 2.2 |

| 9 | M | 72 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 18.5 | 2.6 |

| 10 | M | 59 | Postop | Lymph node mets | 19/72 | 5.8 (4.7, 7.5) | 7.8 (5.6, 9.4) |

| Brain, lung, liver, bone and subcutaneous mets | 55/68 | 4.9 (3.7, 6.5) | 5.5 (4.2, 6.9) | ||||

| 11 | M | 81 | Preop | Primary tumor | 1/0 | 43.7 | 2.4 |

| Lung, adrenal gland and bone mets | 5/4 | 11.2 (5.3, 15.3) | 2.8 (1.8, 4.0) | ||||

| 12 | M | 73 | Postop | Lymph node mets | 3/1 | 21.4 (9.6, 24.9) | 3.6 (2.5, 4.0) |

| Lung and bone mets | 2/2 | 13.1 (7.9, 16.9) | 2.0 (1.0, 9.0) | ||||

Measurable/nonmeasurable lesions on CT according to RESIST 1.1 standard.

Preop = before operation; postop = after operation; met = metastasis.

SUVmax is expressed as specific numeric value or as median followed by first and third quartiles in parentheses.

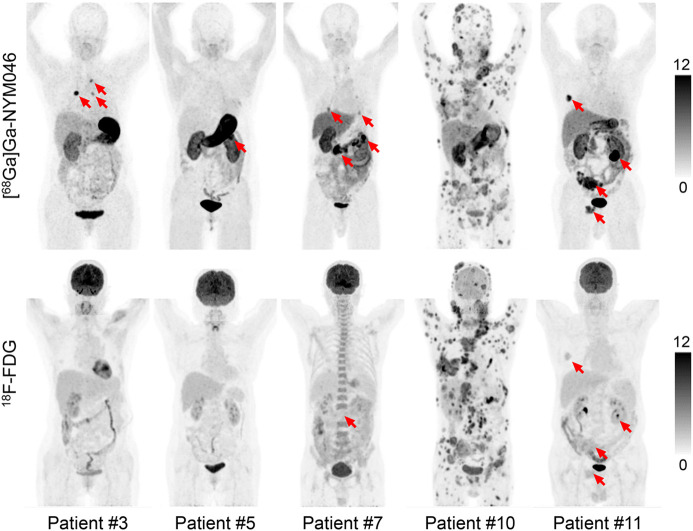

Representative PET/CT images of 5 patients at 1 h after injection of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG are shown in Figure 4. The tissues with the highest SUVmax uptake of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 were the stomach (22.14 ± 16.40), tumor (8.60 ± 5.98), kidney (6.92 ± 2.24), and gallbladder (6.68 ± 2.04; Supplemental Table 2). The SUVmax of 18F-FDG in tumor was 1.87 ± 0.48, which was lower than that of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 (Supplemental Table 2).

FIGURE 4.

Representative maximum-intensity projections of 5 patients (patients 3, 5, 7, 10, and 11) comparing [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG. Both tracers showed specific retention in bone and lymph node metastases (patients 10 and 11). [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT outperformed 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting primary tumors, lung metastases, and pleural metastases (patients 3, 5, 7, and 11).

In visual analysis, the comparison revealed that [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT detected more primary tumors (9/9 vs. 1/9, P = 0.008) and distant metastases (137/147 vs. 127/147, P = 0.041). Meanwhile, these 2 scans had roughly similar efficacy in diagnosing lymph node metastases (Table 2). A typical image comparing the 2 scans is shown (Fig. 5). Additionally, 103 of 252 CT-measurable lesions were positive for [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 uptake, or approximately 41%.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG PET/CT in Patients at 1 Hour After Injection

| SUVmax | Lesions (n) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 | 18F-FDG | z | P | [68Ga] Ga-NYM046 | 18F-FDG | χ2 | P |

| Primary tumor (n = 9) | 13.5 (7.2, 16.2) | 2.4 (2.2, 2.6) | −2.668 | 0.008 | 9 | 1 | 6.125 | 0.008 |

| Lymph node metastases (n = 96) | 5.9 (4.8, 7.8) | 7.6 (5.0, 9.4) | −3.236 | 0.001 | 95 | 92 | 0.800 | 0.375 |

| Distant metastases (n = 147) | 5.0 (3.8, 7.1) | 5.0 (3.7, 6.8) | −0.381 | 0.703 | 137 | 127 | 4.050 | 0.041 |

SUVmax is expressed as median followed by first and third quartiles in parentheses and was assessed using nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Lesion numbers were assessed using McNemar test.

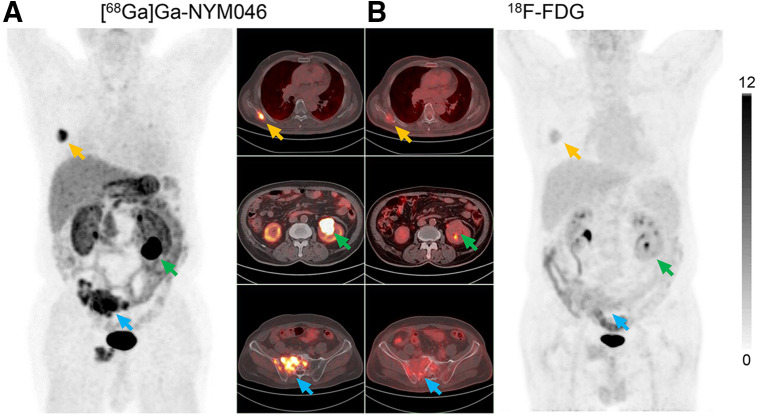

FIGURE 5.

[68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT (A) and 18F-FDG PET/CT (B) scans of patient 11. Bone metastases (yellow and blue arrows) were diagnosed as positive findings in both scans, whereas renal primary tumor (green arrows) was diagnosed as positive finding on [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT but as false-negative finding on 18F-FDG PET/CT.

The uptake of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 and 18F-FDG in all tumor lesions was further analyzed (Table 2). In primary tumors, the SUVmax for [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 was significantly higher than that for 18F-FDG (median, 13.5 vs. 2.4; z = −2.668, P = 0.008). However, a lower SUVmax was observed for [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT than for 18F-FDG PET/CT for metastatic lymph nodes (median, 5.9 vs. 7.6; z = −3.236, P = 0.001). Moreover, no significant differences in SUVmax were found between the 2 agents for distant metastases (median, 5.0 vs. 5.0; z = −0.381, P = 0.703).

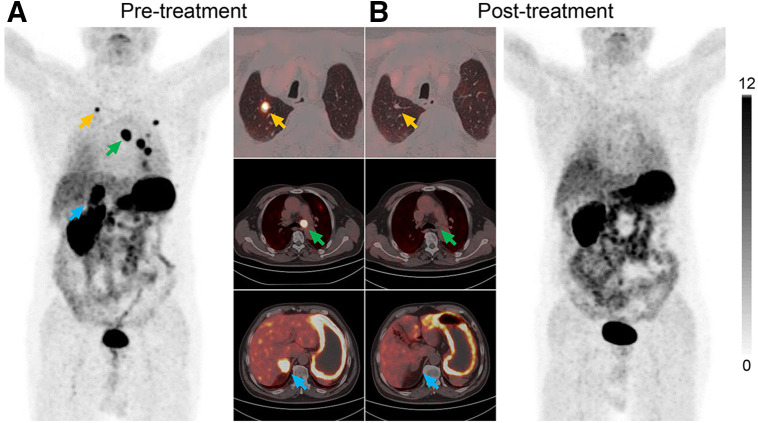

Patient 12, a 73-y-old man, had undergone a total right nephrectomy several years previously and was pathologically diagnosed with ccRCC (Fig. 6). During follow-up, lesions in the right adrenal gland, multiple pulmonary nodules, and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes were identified. [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT confirmed that CAIX was highly expressed at all these sites, with an SUVmax of 23.9. After 2 cycles of treatment with a programmed death receptor 1 inhibitor and a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, posttreatment [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT showed partial shrinkage of the lesions compared with the previous CT images, as well as a significant decrease in uptake on PET.

FIGURE 6.

Images of patient 12 (73-y-old man), who underwent left nephrectomy with pathologically confirmed ccRCC and suspected tumor metastases on follow-up. (A) Images from pretreatment [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT demonstrate mediastinal lymph node metastases (green arrows), lung metastases (yellow arrows), and right adrenal metastases (blue arrows). (B) After 2 treatment cycles, all metastases were negative for uptake.

Some patients in the study underwent nephrectomy after PET/CT, and our group obtained 6 tumor section specimens for immunohistochemical studies with the patients’ informed consent. The immunohistochemical staining results revealed remarkable CAIX expression in these tumors (Supplemental Fig. 6A). Quantitative analysis showed that the higher [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 uptake in primary renal tumors corresponded to higher CAIX expression, with an R2 value of 0.8274 (Supplemental Fig. 6B).

DISCUSSION

Renal cell carcinoma is the most common type of kidney cancer (21). Despite improvements in the 5-y survival rate, the prognosis for patients with advanced ccRCC remains unfavorable (22). Over the past 2 decades, there has been a significant evolution in the diagnosis and treatment of ccRCC, transitioning from traditional to innovative targeted and immunotherapeutic strategies.

Recently, Wu et al. created a novel CD70-targeted tracer, [18F]RCCB6, highlighting the utility of immuno-PET/CT for assessing tumor burden and monitoring treatment responses in patients with advanced ccRCC (23,24). In addition to CD70, CAIX also has demonstrated promising efficacy in theranostics for ccRCC. For example, Turkbey et al. conducted a phase II pilot study of [18F]F-VM4–037 and found that the tracer posed challenges in evaluating primary ccRCC lesions (25). Kulterer et al. studied the performance of [99mTc]Tc-PHC-102, administering a high dose of the tracer to each patient (600–800 MBq) (26).

In this study, we developed the radiotracer [68Ga]Ga–NYM046, characterized by satisfactory purity and stability. Compared with NY104, which also features acetazolamide as its base structure, NYM046 shows similar CAIX-targeting affinity (4.98 nM vs. 5.75 nM) and reduced uptake in normal tissues, including kidney, lung, and bone, as observed in animal models (27). In patients, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT detected all primary tumors (9/9), whereas [68Ga]Ga-NY104 PET/CT showed an accuracy of only 58% (11/19) in cases of a primary renal mass (28). The main structural distinctions between NY104 and NYM046 are the incorporation of a DOTA macrocycle and a naphthyl group. DOTA and its derivatives are known to form highly stable complexes with 68Ga (29,30). Furthermore, previous studies on PSMA-617 have shown that incorporating a naphthylic linker significantly enhances tumor targeting and biologic activity and could help to optimize pharmacokinetics and improve imaging contrast (31,32). In the blocking assay, unlabeled NYM046 effectively inhibited binding of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 to CAIX, further confirming its targeting specificity.

In the clinical study, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 was highly concentrated in the kidneys because of eventual excretion through the urinary system, and it showed high accumulation in the stomach because of the physiologically high expression of CAIX in the human gastric mucosa (33). In a lesion-based analysis, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT detected more primary and metastatic lesions of ccRCC than did conventional CT or 18F-FDG PET/CT. [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 uptake was typically higher than 18F-FDG uptake in primary tumors but was lower in involved lymph nodes and comparable in distant metastases. One reason is that immune cells are an important component of the tumor microenvironment and are present at all stages of tumorigenesis (34). Particularly in 18F-FDG PET/CT, inflammation and the associated reactive activation of tissues can lead to nonspecific uptake in immune cells (35).

Furthermore, this study revealed a positive correlation between the expression of CAIX and the SUVmax of [68Ga]Ga-NYM046. However, the regulation of CAIX expression is predominantly governed by HIF-α–mediated mechanisms. Considering that hypoxia often occurs in solid tumors (36,37), it is important to be aware of the risk for secondary malignancies, with prostate, breast, colon, bladder cancers, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma being the 5 most common secondary malignancies in certain individuals with ccRCC (38). From another perspective, this insight suggests that tracers targeting CAIX may offer a broader scope of clinical utility, extending beyond the traditional association with ccRCC (Supplemental Fig. 7). Further research will be necessary to explore this potential.

The field of integrated diagnostic and therapeutic tracers is gaining increasing prominence. Radiopharmaceutical therapy with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617, used in patients with PSMA-positive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, has shown efficacy in prolonging progression-free and overall survival (39). Consequently, NYM046, which contains a DOTA structure for stable binding with 177Lu, holds certain potential for radiopharmaceutical therapy. However, the aggregation of NYM046 in the gastric mucosa may raise concerns about potential normal-tissue injury and warrants further investigation in future studies.

This study had some limitations. First, the study’s small sample of patients may introduce statistical bias. Second, because of the potential side effects of invasive examinations, the metastatic lesions in the patients were not pathologically confirmed, potentially leading to diagnostic errors. We anticipate addressing these issues in future research.

CONCLUSION

We successfully developed a CAIX-targeting small-molecule tracer, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046, that might offer a practical approach for diagnosing and monitoring treatment efficacy in patients with ccRCC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the clinical and research staff at the Department of Nuclear Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, for technical assistance and helpful discussions. We also thank Norroy Bioscience for professional technical assistance.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Does [68Ga]Ga-NYM046, a novel CAIX-targeted PET tracer, perform better than 18F-FDG in the diagnosis of ccRCC?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: In a prospective study of 12 patients with ccRCC, [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 PET/CT was superior to 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of primary tumors and comparable in the detection of metastatic lesions.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: [68Ga]Ga-NYM046 provides a promising method for diagnosing and monitoring treatment efficacy in patients with ccRCC.

DISCLOSURE

This work was supported by the Subject Construction Fund from the Wuxi Medicine School of Jiangnan University, the Subject Development Fund (FZXK2021011) from the Wuxi Health Select Committee, and the Clinical Research and Translational Medicine Research Fund (LCYJ202331) from the Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rathmell WK, Rumble RB, Van Veldhuizen PJ, et al. Management of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2957–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel U, Sokhi H. Imaging in the follow-up of renal cell carcinoma. AJR. 2012;198:1266–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sivaramakrishna B, Gupta NP, Wadhwa P, et al. Pattern of metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a single institution study. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scatarige JC, Sheth S, Corl FM, Fishman EK. Patterns of recurrence in renal cell carcinoma: manifestations on helical CT. AJR. 2001;177:653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang HY, Ding HJ, Chen JH, et al. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG-PET and PET/CT in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:464–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Majhail NS, Urbain JL, Albani JM, et al. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the evaluation of distant metastases from renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3995–4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Long NM, Smith CS. Causes and imaging features of false positives and false negatives on F-PET/CT in oncologic imaging. Insights Imaging. 2011;2:679–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuccio C, Ceci F, Castellucci P, et al. Restaging clear cell renal carcinoma with 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:e320–e324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dorai T, Sawczuk IS, Pastorek J, Wiernik PH, Dutcher JP. The role of carbonic anhydrase IX overexpression in kidney cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2935–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pastorekova S, Gillies RJ. The role of carbonic anhydrase IX in cancer development: links to hypoxia, acidosis, and beyond. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019;38:65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bismar TA, Bianco FJ, Zhang H, et al. Quantification of G250 mRNA expression in renal epithelial neoplasms by real-time reverse transcription-PCR of dissected tissue from paraffin sections. Pathology. 2003;35:513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liao S-Y, Lerman MI, Stanbridge EJ. Expression of transmembrane carbonic anhydrases, CAIX and CAXII, in human development. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oosterwijk E, Bander NH, Divgi CR, et al. Antibody localization in human renal cell carcinoma: a phase I study of monoclonal antibody G250. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:738–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verhoeff SR, Oosting SF, Elias SG, et al. [89Zr]Zr-DFO-girentuximab and [18F]FDG PET/CT to predict watchful waiting duration in patients with metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29:592–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merkx RIJ, Lobeek D, Konijnenberg M, et al. Phase I study to assess safety, biodistribution and radiation dosimetry for 89Zr-girentuximab in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:3277–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Muselaers CH, Boerman OC, Oosterwijk E, Langenhuijsen JF, Oyen WJ, Mulders PF. Indium-111-labeled girentuximab immunoSPECT as a diagnostic tool in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1101–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verhoeff SR, van Es SC, Boon E, et al. Lesion detection by [89Zr]Zr-DFO-girentuximab and [18F]FDG-PET/CT in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:1931–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhong L, Li Y, Xiong L, et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs: part A—renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barata PC, Rini BI. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma: current status and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:507–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu Q, Wu Y, Zhang Y, et al. ImmunoPET/CT imaging of clear cell renal cell carcinoma with [18F]RCCB6: a first-in-human study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2024;51:2444–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu Q, Wu Y, Zhang Y, et al. [18F]RCCB6 immuno-positron emission tomography/computed tomography for postoperative surveillance in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a pilot clinical study. Eur Urol. 2024;86:372–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Turkbey B, Lindenberg ML, Adler S, et al. PET/CT imaging of renal cell carcinoma with 18F-VM4-037: a phase II pilot study. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kulterer OC, Pfaff S, Wadsak W, et al. A microdosing study with 99mTc-PHC-102 for the SPECT/CT imaging of primary and metastatic lesions in renal cell carcinoma patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu W, Li X, Zheng G, et al. Preclinical and pilot clinical evaluation of a small-molecule carbonic anhydrase IX targeting PET tracer in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50:3116–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhu W, Zheng G, Yan X, et al. Diagnostic efficacy of [68Ga]Ga-NY104 PET/CT to identify clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. June 25, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guleria M, Das T, Amirdhanayagam J, Sarma HD, Dash A. Comparative evaluation of using NOTA and DOTA derivatives as bifunctional chelating agents in the preparation of 68Ga-labeled porphyrin: impact on pharmacokinetics and tumor uptake in a mouse model. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2018;33:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsionou MI, Knapp CE, Foley CA, et al. Comparison of macrocyclic and acyclic chelators for gallium-68 radiolabelling. RSC Advances. 2017;7:49586–49599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Benešová M, Schäfer M, Bauder-Wüst U, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a tailor-made DOTA-conjugated PSMA inhibitor with optimized linker moiety for imaging and endoradiotherapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lundmark F, Olanders G, Rinne SS, Abouzayed A, Orlova A, Rosenström U. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of linker-optimised PSMA-targeting radioligands. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thiry A, Dogné JM, Masereel B, Supuran CT. Targeting tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase IX in cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity. 2019;51:27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Demmert TT, Pomykala KL, Lanzafame H, et al. Oncologic staging with 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT demonstrates a lower rate of nonspecific lymph node findings than 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:1906–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robertson N, Potter C, Harris AL. Role of carbonic anhydrase IX in human tumor cell growth, survival, and invasion. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6160–6165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Becker HM. Carbonic anhydrase IX and acid transport in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rabbani F, Reuter VE, Katz J, Russo P. Second primary malignancies associated with renal cell carcinoma: influence of histologic type. Urology. 2000;56:399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1091–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]