Abstract

Public food purchase programs are a useful tool for promoting food security through rural development, supporting family farmers, and encouraging sustainable and healthy food production. The study aimed to analyse the characteristics of family farmer organizations associated with the Brazilian Public Food Procurement (PFP) program and the opinion of technicians and managers of the organizations regarding the benefits and challenges of the program. A cross-sectional study was conducted through a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire contained questions regarding the characteristics of the organization and the food sales process, as well as the opinion about the benefits and challenges of PFP. The results were stratified according to the organization’s participation in the PFP. The chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was applied. A total of 293 managers and technicians from family farmer organizations participated in the study. The majority of participants (71.7 %) reported their involvement in the PFP program. The study revealed that farmer organizations and public technical assistance agencies with larger memberships and employing conventional or mixed production methods were found to be more actively engaged in the PFP program across Brazil. Participants highlighted that direct sales under the program offer benefits to consumers, producers, and the environment. However, challenges identified include seasonal production constraints, bureaucratic hurdles in sales procedures, inadequate infrastructure for food storage and processing within farmer organizations, insufficient information from restaurants about purchasing opportunities, and a lack of support and technical assistance. These factors pose implementation challenges for the PFP program. While the PFP program shows promise in promoting direct sales and supporting local farmers, addressing the identified challenges will be crucial for its sustained success and broader adoption across different regions.

Keywords: "Food system", "Food security", "Food availability", "Sustainable development", "Institutional food service"

1. Introduction

Public food purchase programs are a useful tool for promoting food security through rural development, supporting family farmers, and encouraging sustainable and healthy food production. In recent years, interest in these programs has grown among both researchers and policymakers [1,2]. This increased interest can be attributed to several key factors, including the growing debate on the sustainability of the food system and the rise in food-related health problems [3,4]. The current global syndemic scenario, where, undernutrition, obesity and climatic variations intersect, stands as one of the most significant challenges today [5].

Concerns regarding the negative social and environmental impacts of the current food system have prompted various global initiatives over time. It all began with the Rome Declaration on Nutrition, which emphasizes the urgent need for food systems to comprehensively address malnutrition and promote healthy and sustainable diets worldwide [6]. Following this, the United Nations provides guidelines in SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) to enhance food security and support sustainable agricultural practices [7]. Reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change further highlight the importance of sustainable agriculture in mitigating and adapting to climate change impacts [8]. The FAO's Policy Framework and Action Plan for Nutrition [9] offer strategic direction for enhancing resilient and nutritious food systems. Lastly, the EAT-Lancet Commission report provides a scientific foundation for promoting healthy dietary practices within the context of environmental sustainability [10]. Governments in many countries of different economic and social backgrounds are developing public policies to promote more sustainable and healthier forms of food production and consumption [2,[11], [12], [13]]. One prominent initiative includes the integration of sustainability criteria into food procurement by public institutions. This involves sourcing local, agroecological food that aligns with cultural preferences and supports family farmers. Brazil has a large area intended for agriculture production; however, the concentration of land emphasizes the inequalities in the rural environment. The 2017 Brazilian Census of Agriculture showed that family farming represents 76.8 % of the total number of agricultural establishments in the country, but takes up the equivalent of 23 % of the total area of such establishments [14]. Unlike the agribusiness model, in which monoculture and food production such as commodities predominate, family farming in Brazil is distinguished by polyculture, many types of seeds grown, and the integration of the farm with the community [15].

As part of the policies to strengthen family agriculture, the implementation of the Food Acquisition Program (PAA for its original acronym) in 2003 made it possible for public procurement of food to be made based on criteria that were not solely economic. As a result, food produced by family farmers, especially in socially vulnerable situations, began to be purchased to supply public institutional food services such as hospitals, universities and public schools [16]. As of 2009, public food procurement from family farmers became mandatory in the school context through the National School Feeding Program (PNAE for its original acronym) [17] and in 2015 this obligation was extended to other public food services (universities, hospitals, armed forces, etc.) through the PAA program in the Institutional Purchase modality [18].

To sell their products to public institutional food services, family farmers - individually or organized into cooperatives, associations or unions - draw up a work plan and present the public institutions’ procurement sector with a proposal for participation. To prepare this proposal, farmers and their organizations can be supported by public technical assistance services. In Brazil, the public service of technical assistance and agricultural extension has existed since 1948 [19]. Currently, the country has 13 State technical assistance companies. In addition, municipal agricultural departments have agronomists and agricultural technicians who support small farmers [20]. Technical support can help less structured farmers enter the market more competitively [21]. Despite the potential benefits of support networks for farmers, there is a significant lack of access to these services, making them often inaccessible to many in the agricultural community. This disparity in access can severely limit the resources available to farmers, impacting their ability to innovate and adopt sustainable practices. Furthermore, the structure and organization of these support networks within a municipality can greatly influence the type of products farmers are able to supply [22,23].

The benefits of public sector food procurement from family farmers for producers, consumers and the environment are already recognized in the literature [[24], [25], [26]]. Evidence shows that these public policies have contributed to building more sustainable food systems by reducing poverty and inequality [27], improving the food offered in institutional settings [28], better living and working conditions in rural areas [21], the strengthening of regional organizational ties [29], increased diversification of family production [30], as well as achieving goals related to food system sustainability and social equity [31]. Therefore, they have been contributing to the achievement of many of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) outlined by 2030 by the United Nations (UN) [7].

Despite incentives via federal programs, the supply of food from local family farmers to public institutional food services has many challenges, including the bureaucracy of the sales processes [32,33], interest on the part of farmers and their organizations [34], delivery logistics [33], farmers dependency on institutional markets [35], outsourcing of food services, lack of technical assistance for farmers, and farmers’ production capacity [36]. However, most studies that show the benefits and challenges of public procurement are conducted from the perspective of institutions that buy food.

Given the importance of public procurement for strengthening the family farm sector, the study aimed to analyse the characteristics of family farmer organizations associated with the Brazilian Public Food Procurement (PFP) program and the opinion of technicians and managers of the organizations regarding the benefits and challenges of the program. Understanding how this programme works in a country with extensive and diverse agriculture, such as Brazil, can provide relevant information for the implementation or improvement of similar programmes in other contexts. Furthermore, by identifying barriers and facilitators, the study can contribute to the development of more effective and equitable policies, promoting more sustainable agricultural development.

2. Methodology

A cross-sectional study was conducted through an electronic questionnaire sent to government and non-government organizations that are related to family farming throughout the Brazilian territory. The questionnaire was answered by technicians and managers of the family farmer organizations (cooperatives, associations, unions) and government organizations that provide technical assistance to family farmers as these workers are often involved in the process of developing projects for the sale of food to public institutions.

For data collection, a structured questionnaire was created on the Google Forms platform that was self-administered by the participants. The questionnaire was developed based on the research team's experience in previous studies [32,36,37]. Before implementation, the questionnaire was reviewed by experts in local food procurement and pilot-tested to ensure its suitability.

The survey included questions about: a. Participant information: organization and position they hold in the organization; b. Characterization of the organization: region of the country to which it belongs (North, Northeast, Midwest, South and Southeast); type of organization (family farmer organization (associations, cooperatives, and unions); government technical assistance agency; others); area of operation (municipal/regional/national); type of food production of the farmers involved (conventional, farmers using herbicides, pesticides and synthetic chemical fertilizers/ecological, farmers not using synthetic chemicals and using biological pest control/mixed, with farmers using the organic production method and others using the conventional production method); number of family farmers registered in the organization; c. Identification of the food sales process: Involved in the PFP program for the supply to institutional food services (yes/no); d. View on the benefits and challenges of implementing the policy of direct food sales to public institutional food services. To identify the view (item d), closed questions were used with three response options (yes, no, and I don't know) focusing on the key benefits and challenges related to the implementation of PFP for the supply to public institutional food services reported by the literature (Table 2, Table 3). The questionnaire had a list of statements regarding direct sales from family farming to public food services. The respondents should answer whether they considered it a benefit, or a challenge based on their experience.

Table 2.

Study participants’ views on the benefits of implementing the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services, stratified as per involvement in the program.

| Benefitsb | Total |

Involvement in the PFP |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) |

Yes, n (%) |

No, n (%) |

||

| 293 (100) | 210 (71.7) | 83 (28.3) | ||

| Stimulates the local economy | Yes | 283 (96.6) | 205 (97.6) | 78 (94) |

| No/Don’t know | 10 (3.4) | 5 (2.4) | 5 (6.0) | |

| Boosts local food production in the region | Yes | 274 (93.5) | 197 (93.8) | 77 (92.8) |

| No/Don’t know | 19 (6.5) | 13 (6.2) | 6 (7.2) | |

| Expands the range of food produced in the region | Yes | 270 (92.2) | 194 (92.4) | 76 (91.6) |

| No/Don’t know | 23 (7.8) | 16 (7.6) | 7 (8.4) | |

| Expands the food processing activities in the region | Yes | 261 (89.1) | 189 (90.0) | 72 (86.7) |

| No/Don’t know | 32 (10.9) | 21 (10.0) | 11 (13.3) | |

| Improve the provision of fresh food within the institutiona | Yes | 280 (95.6) | 204 (97.1) | 76 (91.6) |

| No/Don’t know | 13 (4.4) | 6 (2.9) | 7 (8.4) | |

| Expands the availability of fruits and vegetables on the menus | Yes | 278 (94.9) | 202 (96.2) | 76 (91.6) |

| No/Don’t know | 15 (5.1) | 8 (3.8) | 7 (8.4) | |

| Contributes to the revival of food traditions | Yes | 266 (90.8) | 190 (90.5) | 76 (91.6) |

| No/Don’t know | 27 (9.2) | 20 (9.5) | 7 (8.4) | |

| Enhances the quality of the food provided by the institutional food servicea | Yes | 277 (94.5) | 202 (96.2) | 75 (90.4) |

| No/Don’t know | 16 (5.5) | 8 (3.8) | 8 (9.6) | |

| Contributes to more sustainable food systemsa | Yes | 278 (94.9) | 203 (96.7) | 75 (90.4) |

| No/Don’t know | 15 (5.1) | 7 (3.3) | 8 (9.6) | |

| Increases the farmer’s income | Yes | 283 (96.6) | 206 (98.1) | 77 (92.8) |

| No/Don’t know | 10 (3.4) | 4 (1.9) | 6 (7.2) | |

| Secures a market for produce from family farming | Yes | 277 (94.5) | 201 (95.7) | 76 (91.6) |

| No/Don’t know | 16 (5.5) | 9 (4.3) | 7 (8.4) | |

p<0.05.

Due to the limited number of responses in the 'no' and 'don't know' options, it was decided to combine these categories.

Table 3.

Study participants' views on the challenges of implementing the PFP for the supply to public food services, categorized by their organization’s involvement in the program.

| Challenges | Total |

Involvement in the PFP |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) 293 (100) |

Yes, n (%) 210 (71.7) |

No, n (%) 83 (28.3) |

||

| Food demand surpasses the production capacity of family farms | Yes | 99 (33.8) | 74 (35.2) | 25 (30.1) |

| No | 143 (48.8) | 107 (51.0) | 36 (43.4) | |

| Don’t know | 51 (17.4) | 29 (13.8) | 22 (26.5) | |

| The seasonality of local production prevents meeting the institution's required food demand | Yes | 191 (65.2) | 143 (68.1) | 48 (57.8) |

| No | 64 (21.8) | 45 (21.4) | 19 (22.9) | |

| Don’t know | 38 (13.0) | 22 (10.5) | 16 (19.3) | |

| The institutional procurement of food involves a highly bureaucratic process | Yes | 223 (76.1) | 160 (76.2) | 63 (76.0) |

| No | 48 (16.4) | 38 (18.1) | 10 (12.0) | |

| Don’t know | 22 (7.5) | 12 (5.7) | 10 (12.0) | |

| The food sold by family farmers has a higher cost than other ones | Yes | 117 (39.9) | 87 (41.4) | 30 (36.1) |

| No | 138 (47.1) | 102 (48.6) | 36 (43.4) | |

| Don’t know | 38 (13.0) | 21 (10.0) | 17 (20.5) | |

| Food from family farms is not readily accepted by consumersa | Yes | 72 (24.6) | 55 (26.2) | 17 (20.5) |

| No | 180 (61.4) | 134 (63.8) | 46 (55.4) | |

| Don’t know | 41 (14.0) | 21 (10.0) | 20 (24.1) | |

| The criteria for food sales set by health surveillancea | Yes | 186 (63.5) | 135 (64.3) | 51 (61.4) |

| No | 78 (26.6) | 62 (29.5) | 16 (19.3) | |

| Don’t know | 29 (9.9) | 13 (6.2) | 16 (19.3) | |

| Insufficient food service infrastructure for storagea | Yes | 161 (54.9) | 124 (59) | 37 (44.6) |

| No | 74 (25.3) | 56 (26.7) | 18 (21.7) | |

| Don’t know | 58 (19.8) | 30 (14.3) | 28 (33.7) | |

| Absence of support from public administrationa | Yes | 212 (72.3) | 154 (73.3) | 58 (69.9) |

| No | 50 (17.1) | 42 (20.0) | 8 (9.6) | |

| Don’t know | 31 (10.6) | 14 (6.7) | 17 (20.5) | |

| Insufficient information from the institution about the option to purchase food from family farminga | Yes | 199 (67.9) | 146 (69.5) | 53 (63.9) |

| No | 60 (20.5) | 51 (24.3) | 9 (10.8) | |

| Don’t know | 34 (11.6) | 13 (6.2) | 21 (25.3) | |

| Insufficient information from farmers regarding the opportunity to sell products to public food servicesa | Yes | 172 (58.7) | 123 (58.6) | 49 (59.0) |

| No | 100 (34.1) | 79 (37.6) | 21 (25.3) | |

| Don’t know | 21 (7.2) | 8 (3.8) | 13 (15.7) | |

| Lack of technical assistance for farmersa | Yes | 217 (74.1) | 158 (75.2) | 59 (71.1) |

| No | 52 (17.7) | 40 (19.0) | 12 (14.5) | |

| Don’t know | 24 (8.2) | 12 (5.7) | 12 (14.5) | |

| The payments made by the institution for products from family farming are lowa | Yes | 106 (36.2) | 76 (36.2) | 30 (36.1) |

| No | 144 (49.1) | 118 (56.2) | 26 (31.3) | |

| Don’t know | 43 (14.7) | 16 (7.6) | 27 (32.5) | |

| The number of family farmers in the region is limiteda | Yes | 46 (15.7) | 31 (14.8) | 15 (18.2) |

| No | 229 (78.2) | 171 (81.4) | 58 (69.9) | |

| Don’t know | 18 (6.1) | 8 (3.8) | 10 (12.0) | |

| There are few family farming organizations that offer food for sale in the regiona | Yes | 147 (50.2) | 103 (49.1) | 44 (53.0) |

| No | 117 (39.9) | 92 (43.8) | 25 (30.1) | |

| Don’t know | 29 (9.9) | 15 (7.1) | 14 (16.9) | |

| Insufficient infrastructure for food processing in farmers' organizationsa | Yes | 195 (66.6) | 142 (67.6) | 53 (63.8) |

| No | 64 (21.8) | 51 (24.3) | 13 (15.7) | |

| Don’t know | 34 (11.6) | 17 (8.1) | 17 (20.5) | |

| The logistics of product delivery are quite expensive for family farmersa | Yes | 162 (55.3) | 122 (58.1) | 40 (48.2) |

| No | 93 (31.7) | 66 (31.4) | 27 (32.5) | |

| Don’t know | 38 (13.0) | 22 (10.5) | 16 (19.3) | |

p < 0.05.

The questionnaire was emailed between the first semester of 2019 and 2020. Email addresses available on the website of public agencies providing technical assistance to farmers, such as agricultural departments or technical assistance companies throughout Brazil, were collected. Emails of non-governmental organizations, such as unions, associations, or cooperatives from different regions of Brazil were also collected. In total, 558 email addresses were collected (58 from agricultural secretariats, 70 from technical assistance companies, 62 from trade unions, 342 from cooperatives and 26 from associations). To increase the number of participants, public technical assistance agencies were contacted by telephone. During the phone call, the research objectives were explained to them, their participation was requested, and they were provided with the information needed to complete the questionnaire. When contacting the public technical assistance agencies, they were also asked to help disseminate the research to other organizations related to family farming in the region. To ensure a sufficient number of participants from various regions of the country, this procedure was repeated periodically over the ten-month duration allocated for this stage of the research.

For data analysis, IBM SPSS ver 21 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, EEUU) was used. A descriptive analysis was carried out, stratifying the data according to their involvement in the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services. To analyse the association between the characteristics of the organizations and involvement in the PFP, chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were applied, comparing the characteristics of the organizations involved in the PFP with those that were not involved. The chi-squared test was used for larger sample sizes where the expected frequency in each cell was sufficiently high. For smaller sample sizes or when the expected frequency was low, Fisher's exact test was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The same procedure was employed to analyse participants' opinions regarding the benefits and challenges of implementing PFP. We chose to combine the responses "no" and "don't know" in our analysis of opinions regarding the benefits of the purchase, given the low percentage of these selections. The research received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Brazil) (Register: 3.344.854).

3. Results

Representatives from 293 family farming-related organizations from different regions of Brazil participated in the study. Most participants (54.9 %) worked in the management of the farmers’ organization (administration, managers, presidents); 26.6 % as rural development agents (agronomists, agricultural technicians and extension workers); and 18.4 % were categorized as others (farmers, organization members, researchers). Most of them claimed to do activities related to the PFP program implementation for the supply to public institutional food services, such as preparation of the list of food available for sale (70.6 %); technical assistance for farmers (69.3 %), and development of the food sale project (68.6 %).

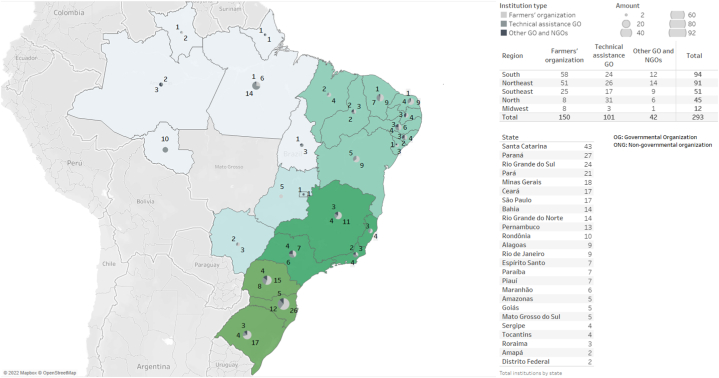

Fig. 1 presents the geographic and organizational distribution of study participants. The South, Northeast, and Southeast had the highest number of participants (n = 94, n = 91, and n = 51, respectively). In contrast, the Midwest and North had the lowest participation, with 12 and 45 participants, respectively. The three southern states had the highest number of participants: Santa Catarina n = 43, Paraná n = 27 and Rio Grande do Sul n = 24. The majority of the respondents stated working in non-governmental farmers’ organizations, such as associations, cooperatives or unions (n = 150/51.2 %), followed by government technical assistance agencies (n = 101/35.5 %). The variation in participant numbers across regions could be attributed to the distinct agricultural characteristics of each region in the country.

Fig. 1.

Geographic and organizational distribution of study participants.

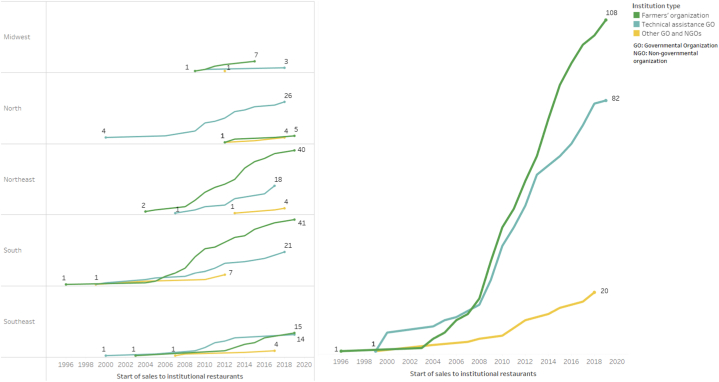

With respect to participation in the PFP program for the supply to public institutional food services, 71.7 % of the participants (n = 210) claimed involvement of the organizations in which they operate. Fig. 2 presents the annual cumulative number of family farmer organizations initiating direct sales to public institutional food services, grouped by organization type and regional distribution. An increase in the number of organizations involved in the PFP can be observed from 2003 onwards, increasing from 2009 onwards. These periods coincide with the time when the public purchase of products from family farmers gained greater relevance in the country's public policies (2003 marks the creation of the PAA food purchase program and 2009 the restructuring of the national school feeding program, PNAE).

Fig. 2.

Annual cumulative number of family farmer organizations initiating direct sales to public institutional food services, grouped by organization type and regional distribution.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of study participants’ organizations as per their involvement in the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services. More than half of the sample worked at the regional level (63.9 %). Participants were mainly located in the Northeast (31.1 %) and South (32.1 %) regions of Brazil. The number of family farmers associated with each organization was quite heterogeneous, ranging from less than 26 to more than 151. Most participants (60.4 %) reported the organization had both farmers who used the ecological production method and farmers who produced in the conventional modality and were therefore categorized as a mixed production method.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants’ organizations as per their involvement in the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services.

| N (%) 293 (100) |

Involvement in the PFP |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) 210 (71.7) |

No, n (%) 83 (28.3) |

||

| Organization Typeb | |||

| Farmers' organizationa | 150 (51.2) | 108 (72.0) | 42 (28.0) |

| Government technical assistance organizationa | 101 (34.5) | 82 (81.2) | 19 (18.8) |

| Other governmental and non-governmental organizations | 42 (14.3) | 20 (47.6) | 22 (52.4) |

| Scope of operationb | |||

| Regionala | 186 (63.9) | 134 (72.0) | 52 [8] |

| Municipala | 66 (22.7) | 47 (71.2) | 19 (28.8) |

| Federal | 39 (13.4) | 27 (69.2) | 12 (30.8) |

| Region | |||

| North | 45 (15.4) | 35 (77.8) | 10 (22.2) |

| Northeast | 91 (31.1) | 62 (68.1) | 29 (31.9) |

| Midwest | 12 (4.1) | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) |

| Southeast | 51 (17.4) | 33 (64.7) | 18 (35.3) |

| South | 94 (32.1) | 69 (73.4) | 25 (26.6) |

| Number of family farmers registered in the organizationb | |||

| ≤ 26 | 99 (33.8) | 54 (54.5) | 45 (45.5) |

| 27–150a | 97 (33.1) | 80 (82.5) | 17 (17.5) |

| 151+a | 97 (33.1) | 76 (78.4) | 21 (21.6) |

| Food production method used by the organization’s farmersb | |||

| Mixed (organic and conventional)a | 177 (60.4) | 136 (76.8) | 41 (23.2) |

| Organic | 59 (20.1) | 38 (64.4) | 21 (35.6) |

| Conventionala | 32 (10.9) | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) |

| Did not answer | 25 (8.6) | 9 [36] | 16 (64) |

p < 0.05.

Total< 293 - missing data.

Of the total participants, 71.7 % said they were involved in the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services. When stratifying the data according to involvement in the PFP, no correlation was found between the region of the country and the food sale to food services.

On the other hand, an association was observed between the type of organization, the scope of operation, the number of farmers registered in the organization, and the method of food production. Farmers’ organizations and public technical assistance agencies, at the regional and municipal level, with more than 26 registered farmers and with the conventional and mixed methods of food production, were more involved in implementing the PFP program for the supply to public institutional food services.

Table 2 shows participants’ views on the benefits of implementing the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services, stratified as per involvement in the program. Participants in both groups recognized that public procurement could be beneficial for stimulating the local economy (96.6 %), for food production in the region (quantity: 93.5 %, variety: 92.2 %; processing: 89.1 %), for the amount of food supplied on the institutional menus (supply of fresh food: 95.6 %, offer of vegetables and fruits on menus; 94.9 %, revival of cooking traditions 90.8 %), for the environment (sustainability of the food system: 94.9 %), and for the producers (increased income: 96.6 %; safe market: 94.5 %).

When comparing the opinions of participants involved in the PFP with those who were not involved, significant differences were identified in some of the variables studied. Among the participants from organizations that were involved in the PFP, a higher percentage showed that the benefits created by this type of sale are the increase in the provision of fresh food within the institution (97.1 %), the improvement in the quality of the food provided (96.2 %) and the contribution for more sustainable food systems (96.7 %), while in the other group, 8.4 %, 9.6 % and 9.6 % respectively, did not express or denied these aspects as benefits related to direct sales (p < 0.05).

Table 3 shows the study participants' views on the challenges of implementing the PFP for the supply to public food services, categorized by their organization’s involvement in the program. More than 65 % of the participants considered as challenges the seasonality of production (65.2 %), bureaucracy (76.1 %), lack of support from public management (72.3 %), lack of information from institutional restaurants (67.9 %), lack of technical assistance (74.1 %), and insufficient infrastructure for food processing in farmers' organizations (66.6 %).

On the other hand, a higher percentage of participants did not consider as being challenges: productive capacity (48.8 %), cost of products (47.1 %), acceptance of family farming products (61.4 %), amounts paid by the institution to the family for the agricultural products (49.1 %), and the number of family farmers in the region (78.2 %).

When comparing the opinions of the group participants involved in the PFP with those who were not involved, significant differences were identified in most variables studied. Specifically, a higher percentage of participants who could not answer was observed among those who were part of organizations that were not involved in the PFP.

4. Discussion

This study analyses the characteristics of family farmer organizations associated with the Brazilian PFP program and the opinion of technicians and managers of the organizations regarding the benefits and challenges of the program. In general, regardless of the region of the country, the farmer organizations and public technical assistance agencies with the highest number of farmers, that use conventional or mixed production methods were most involved in the PFP program. In the participants' view, direct sales can bring benefits to consumers, producers, and the environment. However, the seasonality of production, the bureaucracy of the sales process, the lack of proper infrastructure for food storage or processing in farmers’ organizations, the lack of information from restaurants about the possibilities to purchase food from farmers, the lack of support and technical assistance were considered challenges for its implementation.

Our results show that farmer organizations and public technical assistance agencies with the highest number of farmers are more involved in direct family farm food sales to public institutional food services through the PFP program. These results are consistent with the literature, which concludes that supporting farmers through good organizational structures, such as cooperatives and associations, and support by public technical assistance agencies, contributes to increasing participation in the PFP for the supply to public institutional food services [11]. It is also consistent with a previous study [31], which showed that having a higher number of producers also favors organizations that sell to public institutions. It should be noted that family farming is characterized by small-scale production and the use of the family’s workforce [38], which limits their access to markets where large quantities of food are demanded, as is the case of institutional restaurants. According to a Brazilian study, the average monthly consumption in a university restaurant in the State of Santa Catarina was more than 20 tons of vegetables and 12 tons of fruits [37]. As for school feeding, meals are prepared daily for more than 40 million students across the country [39], which shows the possibilities of public food procurement for the supply these institutions.

One of the purposes of the government procurement of local food from family farming is to strengthen this production sector. However, productive and technical assistance limitations to farmers can hinder their market entry. Collective actions can be a good instrument to facilitate small farmers’ access to institutional markets. Also, their involvement in institutional sales is especially relevant to promoting the sustainability of the food system, which requires increasing the production and consumption of healthy food, such as fruits and vegetables, from agricultural systems that are more respectful of the environment and society [2,40].

Organizations comprised of conventional producers seem to be more involved in PFP for the supply to public institutional food services. Previous studies have already shown the low inclusion of organic food in institutional restaurants [36]. The regulation of institutional procurement sets forth that the prices of organic food can increase by up to 30 % in price compared to what would be paid for a conventional product. However, this regulation does not seem to be sufficient to enable the production and participation of organic food producers in institutional procurement. This may be because this increase in the values paid is not always applied by the institutions that make the purchase. Another possible reason is that farmers who adopted certified organic production systems accessed more lucrative markets than public procurement, even with the 30 % price incentive [41]. It is noteworthy that selling organic food requires a specific certification whose economic cost is not always affordable for family farmers. In addition, the transition process from conventional to organic production requires long periods [32]. However, our results show that part of the organizations participating in the study had conventional and organic producers, which suggests that, despite the challenges, the number of producers changing to organic production may be increasing.

Our results showed that increased demand for fresh food, improved food quality, and contribution to more sustainable food system are said to be benefits associated with PFP from local family farmers for the supply to government food services. Perhaps because it is a direct sale of local agriculture, produced on a small scale, and more labor intensive. However, the seasonality of production is one of the challenges identified among those involved in selling food to institutional restaurants. In fact, as already described in a previous study [31], seasonality makes it difficult to meet institutional demand, as the availability of products changes throughout the year and does not always match food demand. The gap between food supply and demand limits the access of small farmers to this market and the sale of local food. Including food produced by farmers in the region in institutional restaurants requires changes in the food production process organization for restaurants. Previous studies suggest new ways of planning and organizing food purchases, involving nutritionists, family farmers, and agricultural technicians, are needed to introduce food produced by family farming in the region [32]. This is because seasonality is not always a requirement considered when planning menus in institutional restaurants.

In the view of the study participants, the lack of information from institutional restaurants, the limited support by public management to provide technical assistance to farmers and the insufficient infrastructure for food processing in farmers' organizations can also hinder the implementation of policies to supply institutional restaurants with food from family farming. These results suggest that more investment by the administration in training the players involved (restaurant managers, farmers and farmers’ organizations), as well as investment in productive infrastructure, could facilitate the sale of food from family farmers to public institutions.

The positive perception of participants regarding the benefits of direct sales to public institutional food services, such as promoting the local economy, sustainability of the food system, and increasing income for family farmers, underscores its relevance not only for local food security but also in addressing global challenges like climate change and contributing to achieving the SDGs, particularly those related to poverty eradication, food security, and sustainable agriculture. However, family farmer organizations and technical assistance agencies face significant challenges such as seasonal production and bureaucratic hurdles in sales processes, reflecting common barriers to the sustainability of the global food system. The insufficiency of adequate infrastructure and the need for greater technical support highlight the importance of coordinated policies to maximize the economic, social, and environmental benefits of direct local food sales.

When analysing the results of our study, it is noteworthy that voluntary participation and the data collection procedure, which was done online, can influence the response rate. Nevertheless, communication channels were provided via email and telephone with government technical assistance agencies and farmers' organizations to increase the number of participants. Also, because it was a self-completed questionnaire, the participants’ views could be conditioned by their knowledge of the subject under study. Nevertheless, the representation of many actors with different levels of involvement in the PFP and from different regions of Brazil made it possible to explore and compare the characteristics of the family farmer organizations involved in the program and to learn the opinion of their workers regarding the benefits and challenges of implementing it. Conversely, following data collection, a neoliberal agenda was implemented in the Brazil that affected food policies [42].

Nevertheless, the findings from the study provide insight into the opinion of technicians and managers of the family farmer organizations with experience in the direct sale of food to public institutional food services. These findings can assist decision-makers in the implementation of public food procurement programs.

5. Conclusions

This study analyses family farmer organizations participating in Brazil's Public Food Procurement program, focusing on the perspectives of technicians and managers regarding its benefits and challenges. The findings indicate that organizations with larger memberships and those employing conventional or mixed production methods are more actively engaged in the program. Participants highlight potential benefits such as enhanced outcomes for consumers, producers, and the environment, underscoring the program's positive impact. However, the study identifies significant challenges in effectively implementing direct sales through the PFP program, including production seasonality, bureaucratic hurdles in the sales process, inadequate infrastructure for food storage and processing, limited awareness among restaurants about sourcing from local farmers, and insufficient support and technical assistance. To enhance the program's success, targeted interventions are recommended, such as streamlining administrative processes, improving infrastructure support for farmers, increasing awareness campaigns among potential buyers like restaurants, and providing enhanced technical assistance and support services to farmer organizations. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for ensuring the sustained success and broader adoption of the Public Food Procurement program across diverse regions.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological De-velopment, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Brazil: Call CNPq/MCTIC Nº 016/2016.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Panmela Soares: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Suellen Secchi Martinelli: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Elena Albero Atance: Writing – original draft. Rafaela Fabri: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Vicente Clemente-Gómez: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mari Carmen Davó-Blanes: Writing – original draft. Suzi Barletto Cavalli: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Graduate Program in Nutrition, Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), for the postdoctoral scholarship of the National Postdoctoral Program of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (PNPD/CAPES), Brazil, granted to Panmela Soares.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39019.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.FAO . FAO; Rome: 2021. Alliance of Bioversity International, CIAT. Public Food Procurement for Sustainable Food Systems and Healthy Diets – Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swensson L.F.J., Tartanac F. Public food procurement for sustainable diets and food systems: the role of the regulatory framework. Global Food Secur. 2020;25 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindgren E., Harris F., Dangour A.D., Gasparatos A., Hiramatsu M., Javadi F., et al. Sustainable food systems-a health perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2018;13(6):1505–1517. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0586-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fanzo J., Davis C., McLaren R., Choufani J. The effect of climate change across food systems: implications for nutrition outcomes. Global Food Secur. 2018;18:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swinburn B.A., Kraak V.I., Allender S., Atkins V.J., Baker P.I., Bogard J.R., et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the lancet commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FAO, WHO. Rome Declaration on Nutrition . FAO, WHO; Rome: 2014. Second International Conference on Nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, General Assembley 70 session. 2015. pp. 1–35. A/RES/70/1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . IPCC Reports. 2024. https://www.ipcc.ch/reports/ [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.FAO . FAO; Rome: 2021. Strategic Framework 2022-31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willett W., Rockström J., Loken B., Springmann M., Lang T., Vermeulen S., et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnino R. Quality food, public procurement, and sustainable development: the school meal revolution in Rome. Environ. Plann. 2009;41(2):425–440. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith J., Andersson G., Gourlay R., Karner S., Mikkelsen B.E., Sonnino R., et al. Balancing competing policy demands: the case of sustainable public sector food procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;112(Part 1):249–256. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barling D., Andersson G., Bock B., Canjels A., Galli F., Gourlay R., et al. Revaluing public sector food procurement in europe: an action plan for sustainability. Vol. 1. 2013. p. 36. Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasil . IBGE; 2017. Censo Agropecuário 2017. Resultados Definitivos IBGE.https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-2017 [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graeub B.E., Chappell M.J., Wittman H., Ledermann S., Kerr R.B., Gemmill-Herren B. The state of family farms in the world. World Dev. 2016;87:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei nº 10.696, de 2 de julho de 2003 . 2003. Dispõe sobre a repactuação e o alongamento de dívidas oriundas de operações de crédito rural, e dá outras providências. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brasil. Lei n° 11 . Brasília: Diário Oficial da União; 947 de 16 de junho de 2009. Dispõe sobre o atendimento da alimentação escolar e do Programa Dinheiro Direto na Escola aos alunos da educação básica; altera as Leis nº 10.880, de 9 de junho de 2004, 11.273, de 6 de fevereiro de 2006, 11.507, de 20 de julho de 2007; revoga dispositivos da Medida Provisória nº 2.178-36, de 24 de agosto de 2001, e a Lei nº 8.913, de 12 de julho de 1994; e dá outras providências. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decreto nº 8.473, de 22 de junho de 2015 . 2015. Estabelece, no âmbito da Administração Pública federal, o percentual mínimo destinado à aquisição de gêneros alimentícios de agricultores familiares e suas organizações, empreendedores familiares rurais e demais beneficiários da Lei nº 11.326, de 24 de julho de 2006, e dá outras providências. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castro CNd. IPEA; Brasília: 2015. Desafios da agricultura familiar: o caso da assistência técnica e extensão rural. Contract No.: 12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brasil . Pecuária e Abastecimento; 2020. Apoio a Projetos: Ministério da Agricultura.https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/ater/apoio-a-projetos [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berchin I.I., Nunes N.A., de Amorim W.S., Alves Zimmer G.A., da Silva F.R., Fornasari V.H., et al. The contributions of public policies for strengthening family farming and increasing food security: the case of Brazil. Land Use Pol. 2019;82:573–584. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz NBd, Jesus JGd, Bacha C.J.C., Costa E.M. Acesso da agricultura familiar ao crédito e à assistência técnica no Brasil. Rev. Econ. e Soc. Rural. 2021;59 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilpoux O.F., Gonzaga J.F., Pereira M.W.G. Agrarian reform in the Brazilian Midwest: difficulties of modernization via conventional or organic production systems. Land Use Pol. 2021;103 [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Eighth plenary meeting; Geneva: 2004. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Committee A, third report. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . FAO; Rome: 2013. Alimentación escolar directa de la agricultura familiar y las posibilidades de compra: Estudio de caso de ocho países. Fortalecimiento de Programas de Alimentación Escolar en el Marco de la Iniciativa América Latina y Caribe Sin Hambre 2025; p. 107. Proyecto GCP/RLA/180/BRA. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Food Programme . World Food Programme; Rome: 2013. State of School Feeding Worldwide. [Google Scholar]

- 27.FAO. Superação da fome e da probreza rural - Iniciativas brasileiras . Brasília: Organização das Nações Unidas para a Alimentação e a Agricultura. 2016. Organização das Nações Unidas para a Alimentação e a Agricultura; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidaner E., Balaban D., Burlandy L. The Brazilian school feeding programme: an example of an integrated programme in support of food and nutrition security. Publ. Health Nutr. 2013;16(6):989–994. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiodi R.E., de Almeida G.F., Assis L.H.B. Efeitos de políticas de compras institucionais sobre a organização de produtores familiares no Vale do Ribeira. Rev. Econ. e Soc. Rural. 2022;60(3):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valencia V., Wittman H., Blesh J. Structuring markets for resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019;39(2) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittman H., Blesh J. Food sovereignty and fome zero: connecting public food procurement programmes to sustainable rural development in Brazil. J. Agrar. Change. 2017;17(1):81–105. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soares P., Martinelli S.S., Melgarejo L., Davó-Blanes M.C., Cavalli S.B. Strengths and weaknesses in the supply of school food resulting from the procurement of family farm produce in a municipality in Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2015;20:1891–1900. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015206.16972014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assis T.R.P., Franca A.G.M., Coelho A.M. Family farming and school feeding: challenges for access to institutional markets in three municipalities of minas gerais. Rev. Econ. e Soc. Rural. 2019;57(4):577–593. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saraiva E.B., Silva APFd, Sousa AAd, Cerqueira G.F., Chagas CMdS., Toral N. Panorama da compra de alimentos da agricultura familiar para o Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2013;18:927–935. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232013000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandão E.A.F., Santos TdR., Rist S. Family farmers' perceptions of the impact of public policies on the food system: findings from Brazil's semi-arid region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020;4 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soares P., Caballero P., Davó-Blanes M.C. Compra de alimentos de proximidad en los comedores escolares de Andalucía, Canarias y Principado de Asturias. Gac. Sanit. 2017;31:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinelli S.S., Soares P., Fabri R.K., Campanella G.R.A., Rover O.J., Cavalli S.B. Potencialidades da compra institucional na promoção de sistemas agroalimentares locais e sustentáveis: o caso de um restaurante universitário. Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional. 2015;22(1):558–573. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ploeg J.D.V.D. Diez cualidades de la agricultura familiar. Leisa revista de agroecología. 2014;29(4):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.BRASIL, FNDE Dados Físicos e Financeiros do PNAE: Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento da Educação. 2012. https://www.fnde.gov.br/index.php/programas/pnae/pnae-consultas/pnae-dados-fisicos-e-financeiros-do-pnae [Available from:

- 40.Nicholson L., Turner L., Schneider L., Chriqui J., Chaloupka F. State farm-to-school laws influence the availability of fruits and vegetables in school lunches at US public elementary schools. J. Sch. Health. 2014;84(5):310–316. doi: 10.1111/josh.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borsatto R.S., Altieri M.A., Duval H.C., Perez-Cassarino J. Public procurement as strategy to foster organic transition: insights from the Brazilian experience. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019;35(6):688–696. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macedo AdC., Souza-Esquerdo V.F., Borsatto R.S. Neoliberal agenda and the dismantling of socially-efficient public food procurement programs: an emblematic case. Global Food Secur. 2023;37 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.