Abstract

This study aimed to examine the key factors that influence entrepreneurial innovation and organizational performance, specifically focusing on the impact of environmental policy instruments, intellectual capital, and organizational learning. In the context of the resource-based view and institutional theory, the authors developed a comprehensive research model to establish hypotheses about the relationships between these factors. Utilizing a survey-based technique with random sampling, this study analyzes the complex relationships between variables by employing structural equation modeling. Data were obtained from 323 members of management teams from Vietnamese firms. The results emphasize the significant advantage of accruing intellectual capital and fostering organizational learning in response to the impact of environmental policy instruments on entrepreneurial innovation. Furthermore, integrating intellectual capital, entrepreneurial innovation, and organizational learning is shown to improve organizational performance. Entrepreneurial innovation plays a role in connecting organizational performance with intellectual capital and organizational learning. The study’s findings provide valuable insights for scholars and professionals, enhancing comprehension of complex interactions among various elements. Entrepreneurs can utilize these observations to develop inventive tactics that harness both internal and external resources to effectively promote innovation and improve business performance.

Keywords: Environmental policy instruments, Intellectual capital, Organizational learning, Entrepreneurial innovation, Organizational performance

1. Introduction

In recent years, regulatory bodies worldwide have increasingly prioritized the development of comprehensive regulations and suggestions for implementing environmentally friendly practices in producing and providing products and services. Environmental issues stemming from swift industrial growth have become a primary focus for businesses, governments, and societies at large. Moreover, institutional pressure encompasses the imposition of limitations on business conduct through the establishment of regulations, incentives, and penalties. Such pressure arises mostly from requirements imposed by legal authorities [1]. The growing concern among consumers, governments, and societies regarding environmental contamination has increased the recognition of the significance of green innovation [1] and institutional pressure, particularly in terms of environmental policy instruments, for achieving sustainable development across various industries and countries [2,3].

In today’s fiercely competitive business landscape, the survival and prosperity of enterprises hinge on their ability to embrace innovation. The organizational resource-based view (RBV) posits that a firm’s distinctive talents and resources play a pivotal role in its success and sustained competitive advantage [4]. Moreover, the success of innovative operations in the knowledge-driven economy relies on exceptional internal resources, such as intellectual capital (IC) and organizational learning supports, and external resources, such as environmental policy instruments [5]. IC is a combination of information, experience, and practical skills that, when utilized, can generate value [6]. Organizational learning refers to an organization’s ability to process knowledge and adapt its behavior to reflect a new cognitive environment, with the goal of enhancing its performance [7,8]. Environmental policy instruments are government efforts to reduce air and water pollution, solid waste, and natural resource depletion for effective environmental management and governance [9].

Despite a prevailing assumption that IC positively impacts innovation outcomes, empirical investigations of its actual effects have failed to reach consensus, prompting calls for further research into the relationship between IC and innovative performance [10].

Organizational learning significantly impacts the understanding of the factors driving organizational performance [[11], [12], [13], [14]]. Empirical studies exploring the relationship between organizational learning and organizational performance have yielded mixed results. Some have found a positive linear relationship [[12], [13], [14], [15]], others have identified a negative linear relationship [16], and still others have found no significant association [17]. To resolve these contradictory results, some scholars have examined the intermediate processes that underlie the connection between organizational learning and organizational performance [18], proposing innovation as a crucial mediating factor. Despite the valuable insights produced by previous studies, there remains a lack of understanding regarding the role of entrepreneurial innovation in the relationships between IC, organizational learning supports, environmental policy instruments, and their impact on organizational performance.

At the same time, organizations are functioning in more turbulent business environments and under existential pressures [19,20]. Modern organizations must be more flexible, adaptable, and innovative to endure and flourish. The primary challenge for firms lies in identifying a way to function efficiently with substantial profitability while simultaneously upholding their environmental and social obligations. Despite the significant demand for effective solutions, research investigating the potential influence of innovation and internal and external resources on organizational performance in Vietnam is scarce.

This study aimed to fill these research gaps by integrating the RBV with institutional theory. Specifically, it investigated the role of entrepreneurial innovation in mediating the relationships between organizational learning and IC with organizational performance, in the context of Vietnamese enterprises.

To meet these research objectives, an empirical study was undertaken utilizing a sample dataset of 323 managers from Vietnamese enterprises and using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) methodology to investigate three distinct research questions.

RQ1

What environmental policy instruments affect entrepreneurial innovation?

RQ2

What role does entrepreneurial innovation play in the relationships between organizational learning supports, IC, and organizational performance?

RQ3

What organizational learning supports and IC affect organizational performance?

The findings offer valuable insights into how businesses can utilize their internal and external resources to overcome institutional pressure, improve their innovative operations, and achieve robust business performance. Specifically, this study offers several distinct contributions to the existing body of literature and business practices. The research model extends the RBV and institutional theory to explain how environmental policy instruments, IC, organizational learning support, and entrepreneurial innovation interact to enhance organizational performance. Furthermore, the research verifies that innovation plays a partially mediating role in linking organizational learning and IC to organizational performance. This study examined how 2 s-order constructs, IC and environmental policy instruments, impact organizational performance. The findings enable the formulation of numerous crucial suggestions for corporate managers, stakeholders, and legislators.

2. Literature review

2.1. Resource-based view theory

The RBV theory was initially developed by Wernerfelt [21] and later expanded by Barney [4]. This theory emphasizes the importance of resources as the fundamental determinants of business performance. Resources are defined broadly to include all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, business properties, information, knowledge, and other elements that an organization possesses or controls. According to this theory, differences in performance among organizations within the same industry can be attributed to each organization’s possession of unique and diverse resources, characterized by factors such as value, rarity, inimitability, and nonsubstitutability. After undergoing extensive development in recent years, the RBV theory has gained widespread acceptance among scholars in the field of management studies [11,22].

2.2. Institutional theory

Institutional theory is a theoretical framework that Zucker [23] introduced to analyze social processes, particularly external factors. It proposes that organizations are affected by normative constraints that may originate from external sources, such as the state, or from within the organization itself. This theory examines the impact of external pressures on organizational behavior, particularly how these pressures lead to conformity [24]. Moreover, multiple studies indicate that as the level of institutional pressure rises, enterprises tend to become more alike in their efforts to establish legitimacy. As an instance of management innovation, the widespread adoption of the ISO 14000 standard in developed nations showcases consistently imitative behavior [25].

Recently, enterprises have garnered attention for their involvement in environmental pollution issues. Authorities have implemented numerous measures to increase the financial burden associated with producing emissions [1,26]. Therefore, enterprises now use proactive environmental measures to comply with stricter environmental laws and minimize their environmental footprint [27]. Typically, in response to more stringent environmental regulations, enterprises are increasingly allocating resources to research and development (R&D) initiatives, aiming to uncover better and more innovative solutions.

Overall, this study aimed to investigate the relationships between internal resources and the external institutional pressures that influence many aspects of business behavior and performance by combining the RBV and institutional theory. Drawing on the RBV’s emphasis on internal resources like intellectual capital and organizational learning, the study proposes hypotheses regarding their impact on entrepreneurial innovation and business performance. In addition, by incorporating insights from institutional theory that emphasize the importance of external environmental elements and institutional forces, the study broadens its hypotheses to include the effects of environmental policy tools on corporate innovation. This holistic approach acknowledges the dynamic interaction of internal resources, external institutional forces, and organizational responses, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding how organizations navigate challenges, innovate, and ultimately achieve long-term performance outcomes.

2.3. Entrepreneurial innovation

Innovation refers to the implementation of management practices, procedures, and service processes that are inventive and responsive to changes in the environment, especially regarding the adoption of new technologies. The goal is to meet new and diverse needs and expectations, thereby creating a competitive advantage for a company offering new services in various domains [28]. Entrepreneurial innovativeness refers to the active pursuit of novel prospects and goods, as well as the removal of outdated operations, to gain an advantage over rivals and, in turn, increase the creative use of resources and enhance business performance [29,30]. Previous studies have demonstrated how innovation promotes organizational excellence, competitiveness, profitability, and efficiency [[31], [32], [33]]. The RBV can help an organization acquire a competitive advantage through its ability to learn and adapt to new knowledge. This can serve as an explanation for the expected relationship between the organization’s knowledge and learning capacity, innovation, and firm performance.

2.4. Environmental policy instruments and entrepreneurial innovation

Policy instruments are the mechanisms used by governments to implement policies to accomplish political objectives [34]. Likewise, environmental policy instruments refer to the actions governments undertake to tackle air and water pollution, solid waste, and the depletion of natural resources, thus providing effective environmental management and governance [9]. Choosing the right instrument is a complex task that involves the consideration of both efficacy and suitability [35]. The emergence of environmental governance practices has resulted in the development of information methods and voluntary agreements to effectively promote good governance [3].

Lindeneg [36] proposed categorizing environmental policy instruments as market-based or command-and-control instruments. Market-based mechanisms address the external costs of environmental pollution by implementing such measures as sewage charges, environmental subsidies, emissions trading, and other market-oriented approaches [37,38]. Implementing such measures can motivate organizations to adopt environmental innovations, thereby reducing costs that affect firm performance. Another explanation worth mentioning is that being environmentally conscious and implementing eco-friendly practices are linked to long-term organizational advantages. Firms with financial incentives may take on greater risks to achieve long-term rewards. They may develop the ability to absorb and implement environmental innovations due to environmental and R&D spillover effects [2,3]. In other words, environmental policy instruments predictably encourage firms to seek innovation while reducing costs. Overall, enterprises have pursued environmental policy instruments that create a significant driving force to enhance innovation [1,3,39,40].

Command-and-control instruments refers to the measures state administrative departments implement to promote relevant laws, regulations, and standard compliance. These measures aim to prohibit or restrict producers' use of specific pollutants or production methods, thereby influencing polluters’ behavior [3]. Moreover, routines driven by command-and-control regulation can create continuous organizational change and adaptation [41], acting as a catalyst for information exchange and effectively identifying innovation opportunities that would otherwise be hindered by organizational stagnation [2]. Similarly, the command-and-control instrument employs a variety of compulsory means to regulate activities, including imposing technological requirements and setting limits on pollutant discharge concentration [42]. Importantly, those acts effectively function as constraints on businesses, compelling them to comply with standards or face legal consequences.

This resonates with institutional theory, which suggests that institutional pressure compels firms to comply with legitimacy standards and reduce costs associated with illicit operations. This will lead corporations to retire outdated manufacturing methods and research innovative solutions to enhance production processes. The stronger the impact of environmental policy instruments on organizations, the greater their motivation to innovate and the lower the level of social pressure they may encounter. Enterprises with low investment in environmental sustainability may feel pressure to establish legitimacy [43]. Thus, in line with institutional theory and previous studies, the researchers proposed.

H1

Environmental policy instruments positively affect entrepreneurial innovation.

2.5. Organizational learning supports and entrepreneurial innovation

Organizational learning refers to an organization’s ability to effectively assimilate knowledge and adapt its actions in response to changing cognitive circumstances, with the ultimate goal of enhancing its overall performance [7,8]. Organizational learning allows organizations to optimize their ability to adapt and generate new ideas by aligning their internal resources with external demands. March [44] categorized learning into two main types: exploitative learning and exploratory learning. Exploitative activities include the process of carefully choosing, applying, enhancing, and perfecting preexisting information. Exploration is when an organization actively seeks, uncovers, and generates novel information and pursues new possibilities. Effectively managing both exploration and exploitation is crucial for an organization’s long-term survival and success [45]. However, balancing two processes is difficult, as they often compete for scarce resources. In other words, allocating more resources to exploitation results in a reduction of resources available for exploration, and vice versa.

Worth noting is that the RBV posits organizational learning as an essential component of businesses' strategic resources [46]. This study’s association with the RBV suggests that a firm’s competitive advantage relies primarily on its organizational context and its valuable, uncommon, and difficult-to-replicate talents and core competencies, rather than its static resources. The ability to learn and innovate are intangible assets of organizations. Therefore, enhancing the level of organizational learning support results in a competitive advantage. As organizations gain knowledge, their employees develop the capacity to enhance adaptability, flexibility, and effectiveness, ensuring the resilience and competitiveness of the organization [20,47]. Organizations that prioritize learning are better equipped to capitalize on market possibilities, thus enhancing their ability to innovate, create, thrive, and progress [8,48]. This also aligns with the idea that the pursuit of new information is naturally intertwined with the improvement of current knowledge. This combination of exploration and exploitation may lead to novel outcomes [49,50] and higher-level performance [51]. Thus, the researchers proposed.

H2

Organizational learning support can positively affect entrepreneurial innovation.

2.6. Intellectual capital and entrepreneurial innovation

Intellectual capital refers to a collection of knowledge, experience, and practical talents that organizations can use to generate value [6]. Many studies on intellectual capital categorize it into three groups: human capital, structural capital, and relational capital. Human capital is an organization’s most substantial intangible asset [[52], [53], [54]]. It encompasses activities related to education, training, and career development and aims to enhance employees' knowledge, skills, abilities, values, and social assets. Many previous studies have found that human capital contributes the skills necessary to develop an organizational knowledge base, which, in turn, improves firm performance. Other studies have indicated that the knowledge employees possess, along with well-functioning external networks, constitute the most effective combination for achieving success [55]. Structural capital refers to the nonhuman knowledge resources inside an organization that facilitate the performance of human capital [56]. This category consists of information systems and databases, established routines, procedures, processes, corporate culture, methods, business development plans, intellectual property, and any other assets beyond physical assets that contribute to the organization’s worth [57]. Relational capital is the collective value of assets that facilitate and oversee ties with the surrounding environment [28].

Intellectual capital is the knowledge and information possessed by an organization, which can function as a unique intangible asset that helps organizations foster innovation [58,59]. Integrating this premise with the RBV suggests that businesses with extensive and diverse knowledge will possess a greater capacity for creativity. Hence, utilizing an organization’s intellectual capital is both a method and a necessity for promoting innovation. Based on these arguments, the researchers proposed.

H3

Intellectual capital positively affects entrepreneurial innovation.

2.7. Organizational learning supports, organizational innovation, and performance

Human resources are paramount in organizations and play a crucial role in determining organizational effectiveness and performance [20]. Additionally, the RBV posits that innovative human resource practices are crucial for gaining a competitive advantage, highlighting the significance of human and intellectual functions in achieving strategic objectives [4,60]. Therefore, the more organizational learning supports human resource management, the more opportunities the organization will have to improve and develop firm performance, achieving competitive advantage through innovative capacities. Organizational learning is an ongoing process that occurs over time, providing the organization with additional abilities and knowledge to enhance its competence [61] and improve performance through various activities [14]. The literature in this field has also emphasized the importance of organizational learning for the efficient functioning and long-term sustainability of organizations [61,62].

First, empirical studies have demonstrated growing scholarly interest in the correlation between organizational learning and performance, despite the existing literature presenting ambiguous results. Several studies suggest that organizational learning aids enterprises in updating their existing knowledge, acquiring new knowledge, and disseminating it across the organization, thereby contributing to enhancing enterprise performance. In particular, several studies have provided evidence to support the existence of a positive relationship between organizational learning and performance [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]]. Meanwhile, other studies argue that organizational learning involves consuming resources, including intangible resources such as information and knowledge. However, these studies suggest that acquiring information and knowledge through organizational learning does not directly affect the performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. In other words, no significant correlation exists between organizational learning and performance [17]. To resolve these contradictory results, some scholars examined the intermediate processes involved in the connection between organizational learning and organizational performance [63] and found that innovation serves as a crucial mediating factor. Although their study provided useful insights, there remains a limited understanding of the mediating factors (such as enterprise innovation) that can convert both organizational learning supports and intellectual capital into organizational performance. To fill this gap, this study investigated these mediating effects.

Second, a direct association exists between organizational innovation and organizational performance. Organizations that actively pursue innovation and successfully adjust to their surroundings are more likely to acquire the skills necessary to enhance their performance and maintain a sustainable competitive edge [14,64]. García‐Morales et al. [65] highlighted open innovation and organizational learning as key determinants of organizational performance. They emphasized these factors as crucial for increasing market share and providing companies with a competitive advantage through improved organizational performance [14,65]. Other empirical studies have confirmed a significant positive relationship between organizational innovation and performance [66].

Finally, intellectual capital is the primary source of competitive advantage, significantly influencing an organization’s innovation performance [67]. The growing focus on intellectual capital might be due to organizations' desire to achieve success through innovation performance [58,59]. Based on these arguments, the researchers proposed the following hypotheses.

H4

Organizational learning supports positively and significantly impact organizational performance.

H5

Entrepreneurial innovation positively and significantly impacts organizational performance.

H6

Intellectual capital positively and significantly impacts organizational performance.

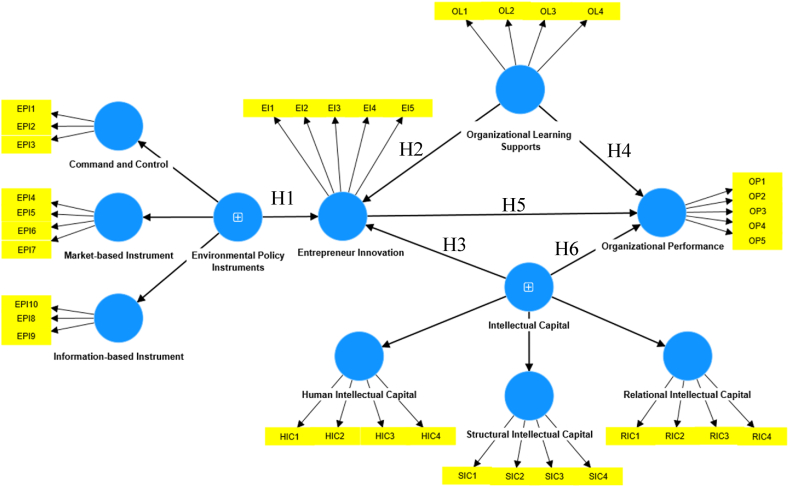

The study introduces a research model that elucidates the relationships between the variables covered by the six hypotheses, drawing from discussions in the literature. The paper also examines the mediating role of entrepreneurial innovation in connecting organizational learning supports and intellectual capital with organizational performance. Fig. 1 illustrates the research model. It is worth noting that two constructs—environmental policy instruments and intellectual capital—are established as second-order constructs.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and procedure

The study design’s basis is a quantitative method, using a survey-based technique to collect data. To adapt the measurements to Vietnamese circumstances, an English instructor initially translated the questionnaire into Vietnamese and made necessary modifications. Subsequently, the authors conducted two group discussions that included six directors from various enterprises and two government executives serving on an industrial zone administration board. In response to participants' comments, the questionnaire underwent modifications to align it with the specific research setting in Vietnam. In addition, the authors ran a pilot test involving 35 participants and made minor adjustments to confirm that meanings were appropriate within the research context.

Notably, the researchers modified the questionnaire to align with relevant literature, incorporating insights from two group discussions and the pilot test to accurately capture the underlying variables examined in this investigation, as outlined in the supplemental file. Before the data-gathering process commenced, this project received approval from the Center for Public Administration Ethics Committee (CFPA-RC-23-02-23) and obtained consent from the participants (CFPA-RC-26-02-23).

The researchers designed the questionnaire to capture managers’ perceptions of their enterprises regarding intellectual capital, environmental policy instruments, innovative activities, and organizational performance. The authors obtained robust endorsement from the management boards of the industrial zones in Dong Nai Province, Vietnam, to obtain access to a roster of 850 prospective enterprises. They acquired a sample of 323 valid responses for analysis by randomly selecting 500 enterprises from the list that would receive the questionnaire between March and August 2023. Table 1 shows specific information on the characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Characteristics | Number (N=323) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job title | Board of directors | 65 | 20.10 % |

| Executive managers | 258 | 79.90 % | |

| Working experience | 5–10 years | 6 | 1.90 % |

| 11–15 years | 59 | 18.30 % | |

| 16–20 years | 129 | 39.90 % | |

| More than 20 years | 129 | 39.90 % | |

| Number of employees | Less than 20 | 6 | 1.90 % |

| 20–50 | 25 | 7.70 % | |

| 51–99 | 37 | 11.50 % | |

| 100–199 | 101 | 31.30 % | |

| 200–299 | 65 | 20.10 % | |

| More than 300 | 89 | 27.60 % | |

| Industry | Electricity and water supply | 28 | 8.70 % |

| Finance and banking | 84 | 26.00 % | |

| Logistics and supply chain | 12 | 3.70 % | |

| Manufacturing | 105 | 32.50 % | |

| Warehouse, factory, land for rent | 94 | 29.10 % | |

Source: Created by the authors.

3.2. Measures

This study’s latent constructs used a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree.” The authors made minor modifications to all structural items in previous studies to fit the context of Vietnam. First, they adapted environmental policy instruments from previous studies [3,39,40]. However, this study distinguished itself by building this variable as a second-order construct with an overall Cronbach’s alpha (α) of 0.905, exceeding the 0.6 threshold. This includes three first-order constructs: command-and-control instruments (α = 0.902), market-based instruments (α = 0.914), and information-based instruments (α = 0.832).

Second, the researchers adapted entrepreneurial innovation with five items from prior studies [47,68] (overall α = 0.854). Third, they adapted organizational learning supports with four items from previous studies [8,48] (overall α = 0.829). Fourth, they adapted intellectual capital from prior studies [[52], [53], [54]], established it as a second-order construct (overall α = 0.953), and included three first-order constructs: human intellectual capital (α = 0.907), structural intellectual capital (α = 0.908), and relational intellectual capital (α = 0.901). Finally, they adapted organizational performance from other studies [69] (overall α = 0.891). Table 2 provides further details of the reliability and validity results for all constructs in the research model.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity of the constructs.

| Constructs and items | λ | α | CR | AVE | FCVIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental policy instruments (EPI) (Second-order construct) | 0.905 | 0.910 | 0.540 | |||

| Command-and-control instruments (First-order construct) | 0.902 | 0.902 | 0.836 | 1.994 | ||

| EPI1 | If our enterprise violates environmental standards, it will be subject to strict penalties. | 0.904 | ||||

| EPI2 | The laws and regulations that our enterprise faces are very sound. | 0.920 | ||||

| EPI3 | The technical standards of pollution reduction that our enterprise faces are very stringent. | 0.919 | ||||

| Market-based instruments (First-order construct) | 0.914 | 0.917 | 0.795 | 1.201 | ||

| EPI4 | By carrying out environmental pollution control, our enterprise can get tax concessions. | 0.655 | ||||

| EPI5 | By carrying out environmental pollution control, our enterprise can get government subsidies. | 0.891 | ||||

| EPI6 | If discharging pollution, our enterprise should bear the corresponding taxes. | 0.927 | ||||

| EPI7 | Our enterprise should pay a certain amount of pollution margin. | 0.841 | ||||

| Information-based instruments (First-order construct) | 0.832 | 0.833 | 0.749 | 1.512 | ||

| EPI8 | Our enterprise must release environmental information in a timely manner. | 0.786 | ||||

| EPI9 | Our enterprise’s environmental management standards have ISO14000 certification. | 0.745 | ||||

| EPI10 | Our enterprise promises to voluntarily achieve higher environmental performance than regulatory requirements. | 0.756 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial innovation (EI) | 0.854 | 0.866 | 0.635 | 1.455 | ||

| EI1 | Our enterprise has abilities to use new technology. | 0.808 | ||||

| EI2 | Our enterprise is willing to take first-mover advantage in product value addition. | 0.825 | ||||

| EI3 | Our leaders don’t fear risk-taking while implementing new technology. | 0.657 | ||||

| EI4 | Our enterprise is familiar with using information and communications technology (ICT) applications in business. | 0.846 | ||||

| EI5 | Our enterprise has skills in adapting technology trends to help create new things. | 0.833 | ||||

| Organizational learning supports (OL) | 0.829 | 0.840 | 0.661 | 1.639 | ||

| OL1 | The enterprise has acquired and shared a significant amount of new and relevant knowledge, which has provided a competitive advantage. | 0.840 | ||||

| OL2 | The enterprise’s members have acquired some critical capacities and skills that provide a competitive advantage. | 0.861 | ||||

| OL3 | The entrepreneurial improvements have been fundamentally influenced by new knowledge entering the enterprise. | 0.742 | ||||

| OL4 | The enterprise is a learning organization. | 0.803 | ||||

| Intellectual capital (IC) (Second-order construct) | 0.953 | 0.953 | 0.658 | |||

| Human intellectual capital (First-order construct) | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.782 | 1.428 | ||

| HIC1 | Employees of our enterprise have excellent professional skills in their jobs and functions. | 0.817 | ||||

| HIC2 | The enterprise provides well-designed training programs. | 0.863 | ||||

| HIC3 | Employees are creative in our enterprise. | 0.805 | ||||

| HIC4 | Employees hold suitable work experience for accomplishing their job successfully in our enterprise. | 0.666 | ||||

| Structural intellectual capital (First-order construct) | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.784 | 1.675 | ||

| SIC1 | Our enterprise responds to changes very quickly. | 0.794 | ||||

| SIC2 | Our enterprise emphasizes new market development. | 0.784 | ||||

| SIC3 | Our enterprise’s culture and atmosphere are flexible and comfortable. | 0.792 | ||||

| SIC4 | The overall operations procedure of our enterprise is very efficient. | 0.799 | ||||

| Relational intellectual capital (First-order construct) | 0.901 | 0.901 | 0.772 | 1.411 | ||

| RIC1 | Our enterprise maintains appropriate interactions with its stakeholders. | 0.839 | ||||

| RIC2 | Our enterprise maintains long-term relationships with customers. | 0.896 | ||||

| RIC3 | Our enterprise has stable and good relationships with strategic partners. | 0.902 | ||||

| RIC4 | Our enterprise solves problems through effective collaboration. | 0.875 | ||||

| Organizational performance (OP) | 0.891 | 0.891 | 0.696 | 1.527 | ||

| OP1 | The enterprise is capable of sustainable development. | 0.849 | ||||

| OP2 | The quality of the enterprise’s products/services has improved over time. | 0.857 | ||||

| OP3 | The enterprise has a good reputation in the industry. | 0.831 | ||||

| OP4 | The enterprise’s customers appreciate its product/service quality. | 0.819 | ||||

| OP5 | The enterprise’s sales volume has increased over the last 3 years. | 0.815 | ||||

Notes: Factor loading: λ, Cronbach’s alpha: α.

Source: Created by the authors.

3.3. Data analysis

One limitation of the PLS-SEM approach is its lack of traditional fit indices and rigorous measurement model assessment, compared to the covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) approach. This can lead to inflated estimates and potential oversight of measurement error and validity issues. Moreover, CB-SEM is a well-established and extensively researched method in the field of social sciences. However, PLS-SEM has become increasingly popular in organizational research applications in the last decade, as a supplemental approach to SEM [70]. The researchers based the decision to utilize the PLS-SEM methodology on its recognized effectiveness and flexibility. The social sciences commonly use this method, and it is well-suited to complex models with complicated structures involving several interactions at the concept level [71,72]. The primary purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between different latent variables within the complex research model. Hence, for this study design, PLS-SEM was appropriate for analyzing causal relationships among multiple independent and dependent variables, thereby prioritizing the validation or rejection of the hypotheses as formulated.

4. Results

4.1. Testing for convergent and discriminant validity

The researchers examined the research model using the SmartPLS 4.0 application package. Following the completion of descriptive studies, the authors employed the two-stage analytical technique outlined by Hair et al. [73]. Subsequently, the study examined convergent validity, discriminant validity, internal consistency, and reliability, as well as item-by-item reliability, to verify the model’s suitability. As shown in Table 2, both the minimum loading of 0.655 and the highest loading of 0.919 exceeded the threshold of 0.50 [74]. The researchers assessed the study’s internal consistency and reliability by calculating α and composite reliability (CR) [75]. Table 2 shows that the measurement model exhibits internal consistency and reliability, with the CR value and α exceeding the 0.70 threshold for all components. To evaluate convergent validity, the authors computed the average variance extracted (AVE). Table 2 demonstrates that all constructs had AVE values above the convergent validity threshold of 0.5 [74].

The researchers employed the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) criterion to evaluate discriminant validity, with an HTMT score below 0.90 establishing discriminant validity between two reflective conceptions [76]. Table 3 demonstrates that all values are inside the specified range, thus meeting the criterion for discriminant validity. Overall, the reflective constructs in the research model satisfied both convergent and discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

| Construct | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTMT ratio | |||||||||

| Command and Control (1) | |||||||||

| Entrepreneurial Innovation (2) | 0.612 | ||||||||

| Human Intellectual Capital (3) | 0.543 | 0.534 | |||||||

| Information-Based Instrument (4) | 0.818 | 0.536 | 0.539 | ||||||

| Market-Based Instrument (5) | 0.424 | 0.245 | 0.340 | 0.582 | |||||

| Organizational Learning Supports (6) | 0.628 | 0.800 | 0.617 | 0.615 | 0.236 | ||||

| Organizational Performance (7) | 0.651 | 0.804 | 0.543 | 0.555 | 0.236 | 0.899 | |||

| Relational Intellectual Capital (8) | 0.632 | 0.600 | 0.677 | 0.529 | 0.246 | 0.733 | 0.769 | ||

| Structural Intellectual Capital (9) | 0.581 | 0.653 | 0.884 | 0.519 | 0.275 | 0.643 | 0.641 | 0.698 |

Notes: The square root of AVE for a construct is highlighted in bold along the diagonal.

Source: Created by the authors.

4.2. Common method bias

Several researchers have discovered that using the full collinearity variance inflation factor (FCVIF) can detect common method bias (CMB). Kock [77] proposed that an FCVIF value below 3.3 indicates the absence of any CMB issues in the data, which Table 2 shows for all latent constructs.

4.3. Structural equation model

To test the structural models, the authors used the bootstrapping technique to calculate the estimates, R2, and respective t-values for resampling of 5000 [73]. R-squared values for entrepreneurial innovation and organizational performance were 0.510 and 0.689, respectively. These values of the endogenous constructs fall within the designated thresholding range. Consequently, these results were satisfactory, indicating a favorable model fit.

Table 4 also demonstrates the hypothesis testing. All hypotheses were accepted at a significant level (p-value <0.05). Moreover, the researchers estimated indirect effects to determine the mediation effects of entrepreneurial innovation on the relationships between 1) organizational learning supports and organizational performance and 2) intellectual capital and organizational performance. Table 4 depicts the mediation results, illustrating that all testing outcomes partially mediated these relationships.

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing.

| Direct effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Estimates | T-values | P-values | Remarks |

| H1. EPI → EI | 0.126 | 2.410 | 0.016 | Supported |

| H2. OL → EI | 0.481 | 8.538 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3. IC → EI | 0.208 | 3.244 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4. OL → OP | 0.470 | 9.010 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5. EI → OP | 0.270 | 5.446 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6. IC → OP | 0.197 | 4.172 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Mediation effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Type | Estimates | T-values | P-values | Remarks |

| H4. OL → OP | Direct | 0.470 | 9.010 | 0.000 | Supported |

| OL → EI → OP | Indirect | 0.130 | 4.161 | 0.000 | Partial mediation |

| H6. IC → OP | Direct | 0.199 | 3.514 | 0.000 | Supported |

| IC → EI → OP | Indirect | 0.056 | 2.129 | 0.033 | Partial mediation |

Source: Created by the authors.

5. Discussion and implications

5.1. The role of environmental policy instruments in enhancing entrepreneurial innovation

This study aimed to investigate the crucial aspects and environmental policy instruments involved in expanding the RBV and institutional theory. The findings demonstrate that environmental policy instruments exert a substantial influence on entrepreneurial innovation (supporting H1, as shown in Table 4), consistent with previous studies [1,3,39,40]. The results indicate that environmental policy instruments establish a favorable atmosphere for innovation by aligning economic incentives, establishing benchmarks, and promoting cooperation. By incorporating environmental considerations into economic decision-making, these policies facilitate the advancement and acceptance of sustainable technologies, promoting both environmental preservation and economic expansion. Governments frequently provide financial incentives, such as subsidies and grants, to promote the advancement and acceptance of clean and sustainable technologies. This fosters innovation by mitigating the financial risks that R&D in green technologies entails. Furthermore, governments can establish stringent emission criteria and environmental rules to incentivize firms to allocate resources toward R&D efforts aimed at meeting these criteria. This can result in the emergence of novel technologies and methodologies that are more ecologically sustainable.

5.2. The role of intellectual capital and organizational learning supports stimulating organizational innovation and performance

First, the findings indicate that intellectual capital significantly impacts both entrepreneurial innovation (supporting H3) and organizational performance (supporting H6; see Table 4). Hence, the incorporation of intellectual capital substantially influences an organization’s bottom line. Moreover, organizations with strong intellectual–capital capabilities are more likely to have better possibilities for growth, a crucial factor in the organization’s long-term performance. These findings are consistent with existing research emphasizing the importance of intellectual capital in promoting innovation activities [58,59] and driving business outcomes [[52], [53], [54]]. Therefore, intellectual capital encompasses intangible assets and knowledge-based resources that are essential in stimulating business innovation and overall organizational performance.

Second, a positive association exists between the level of support for organizational learning and the extent of entrepreneurial innovation (supporting H2). This outcome aligns with initial expectations [8,48]. Organizations that prioritize learning can more effectively capitalize on market opportunities, leading to enhanced capacity for innovation, development, prosperity, and growth.

Finally, consistent with previous studies [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]], the findings provide strong evidence to support the role of organizational learning support as a critical determinant of organizational performance (supporting H4). The literature suggests that enhanced integration of organizational learning within human resource management increases the potential for improved company performance and the attainment of competitive advantage by fostering innovative capacities. Organizational learning is a continuous process that occurs gradually. The organization gains supplementary capabilities and knowledge to augment its proficiency [61] and enhance overall performance [14]. Specifically, the findings from the mediating-effects tests demonstrate the partial mediation effect of entrepreneurial innovation.

5.3. Theoretical implications

Examining the connections between environmental policy instruments, entrepreneurial innovation, intellectual capital, organizational learning supports, and organizational performance, by integrating the RBV and institutional theory is a valuable pursuit in the field of management studies and innovation management. Some of its theoretical contributions follow.

First, the traditional RBV framework focuses primarily on internal capabilities and resources. However, the integration of institutional theory enables the examination of external factors, such as environmental policy instruments, and internal resources, such as organizational learning support and intellectual capital. The research findings highlighted the roles of these factors in enhancing organizational innovation and performance in Vietnamese enterprises.

Second, within the institutional framework, incorporating environmental policy instruments as the second-order construct into this theory entails considering different types of policy instruments (such as market-based instruments, command-and-control instruments, and information-based instruments) as sub-dimensions that collectively represent the overall concept of environmental policy instruments. This approach enables a more intricate and all-encompassing comprehension of their function and influence. Importantly, this approach has the potential to foster the creation of novel policy instruments, combining the advantages of several types to effectively tackle intricate environmental problems. Similarly, IC is established as a second-order construct with the ability to provide a higher level of universality or a more inclusive viewpoint. This strategy allows for a deeper understanding of complex interactions while reducing the possible complications associated with generating multiple hypotheses. In simpler terms, it enhances the manageability and clarity of our model, increasing its accuracy in representing the underlying theoretical framework. This approach supports the ability to produce more significant and reliable results.

Finally, within the RBV, integrating IC as a secondary construct involves assessing its different elements (i.e., human capital, structural capital, and relational capital) as subordinate dimensions that ultimately reflect the broader idea. This technique offers a more intricate and all-encompassing comprehension of the role and influence of intellectual capital within businesses. Specifically, it has profound implications for strategic management, organizational performance, innovation, and learning experience, offering vital insights for IC scholars and practitioners.

5.4. Practical implications

First, this research aids organizations in effectively aligning internal resources while considering external pressures. Organizations can use this alignment to enhance their creative capacity and facilitate learning activities. This paper also offers practical principles for implementing the use of intellectual capital, including encouraging individual creativity; implementing professional training programs; being open to new challenges; establishing strong relationships with stakeholders, customers, and strategic partners to encourage innovation; and improving overall performance.

Second, this paper offers a comprehensive analysis of innovation management within business environments. The management team should create pragmatic guidelines to cultivate an innovative culture, organize innovation teams, and oversee the entire innovation process. This should include idea generation, leveraging new technology, seizing opportunities to be the first mover in the market, enhancing knowledge and skills for implementing ICT applications, and developing new products or services.

Ultimately, the primary objective of the management team should be to comply with environmental standards, laws, and regulations for minimizing pollution. Organizations that demonstrate a commitment to controlling environmental pollution can potentially receive tax reductions and enhance their reputations for social responsibility. By diligently adhering to these commitments, they are more inclined to allocate resources toward R&D to promote and endorse innovative initiatives. Importantly, pragmatic contributions play a crucial role in bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and practical applications, facilitating informed decision-making, and encouraging sustainable development.

6. Conclusion, limitations, and future research goals

6.1. Conclusion

This study provides new insights into the relationship between environmental policy instruments and entrepreneurial innovation, as well as its outcomes. By combining the theoretical perspectives of the RBV, institutional theory, and relevant literature, the authors discovered that entrepreneurial innovation plays a partially mediating role. This role is crucial in establishing the significant connections between organizational performance and both intellectual capital and organizational learning supports. Furthermore, including two secondary concepts—intellectual capital and environmental policy instruments—enhanced the theoretical framework by offering a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of the role and impact of intellectual capital and businesses’ environmental compliance. Significantly, these findings provide valuable insights into how businesses can utilize environmental policy tools and leverage internal resources to support and encourage innovative initiatives in response to external constraints, ultimately achieving sustainable development.

6.2. Limitations and future research goals

First, notwithstanding the valuable discoveries of this work, it is necessary to recognize various constraints. Exclusively depending on self-reported data introduces the possibility of bias or inaccuracy. Future research endeavors could incorporate objective performance metrics or utilize secondary data to enhance the validity of the findings.

Second, we followed the proposals of previous studies in investigating mediating effects. However, future studies should consider testing the moderating effects of critical factors in the research model, such as organizational learning and intellectual capital. In addition, incorporating organizational learning has substantially advanced the research model. However, the organizational capacities to absorb and assimilate new knowledge can significantly influence the achievement of learning outcomes. Hence, future studies could delve deeper into this facet of the topic.

Ultimately, concentrating on particular characteristics and their connections, potentially disregarding other significant variables that may impact organizational performance, limits this study’s scope. Significantly, areas such as organizational culture, cybersecurity, external disruptions, and leadership styles have not been thoroughly investigated. Future studies could incorporate these variables to enhance the understanding of the factors that determine organizational efficiency. Analyzing these components and their potential interactions can lead to a deeper comprehension of the factors that drive organizational success, providing valuable insights into both theoretical and practical aspects.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Thang Nam Huynh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Phuong Van Nguyen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Anh Minh Do: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology. Phuong Uyen Dinh: Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Investigation. Huan Tuong Vo: Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

8. Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

7. Funding statement

This research was funded by Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCMC) under grant number B2022-28–04.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Thang Nam Huynh, Email: thangnamhuynh74@gmail.com.

Phuong Van Nguyen, Email: nvphuong@hcmiu.edu.vn.

Anh Minh Do, Email: minhanh16042001@gmail.com.

Phuong Uyen Dinh, Email: phuong.du@ou.edu.vn.

Huan Tuong Vo, Email: vthuan@hcmiu.edu.vn.

References

- 1.Qi G., Jia Y., Zou H. Is institutional pressure the mother of green innovation? Examining the moderating effect of absorptive capacity. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;278 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X., Chu Z., Ren L., Xing J. Open innovation and sustainable competitive advantage: the role of organizational learning. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2023;186 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao Z. Environmental policy instruments, environmental innovation and the reputation of enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;171:1111–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991;17:99–120. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehman S.U., Elrehail H., Alsaad A., Bhatti A. Intellectual capital and innovative performance: a mediation-moderation perspective. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022;23:998–1024. doi: 10.1108/JIC-04-2020-0109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allameh S.M., Rezaei A., Seyedfazli H. Relationship between knowledge management enablers, organisational learning, and organizational innovation: an empirical investigation. Int. J. Bus. Innovat. Res. 2017;12:294–314. doi: 10.1504/IJBIR.2017.082087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu I.-L., Chen J.-L. Knowledge management driven firm performance: the roles of business process capabilities and organizational learning. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014;18:1141–1164. doi: 10.1108/JKM-05-2014-0192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obeso M., Hernández-Linares R., López-Fernández M.C., Serrano-Bedia A.M. Knowledge management processes and organizational performance: the mediating role of organizational learning. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020;24:1859–1880. doi: 10.1108/JKM-10-2019-0553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mickwitz P. A framework for evaluating environmental policy instruments. Evaluation. 2003;9:415–436. doi: 10.1177/135638900300900404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostini L., Nosella A. Enhancing radical innovation performance through intellectual capital components. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017;18:789–806. doi: 10.1108/JIC-10-2016-0103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding Z., Li M., Yang X., Xiao W. Ambidextrous organizational learning and performance: absorptive capacity in small and medium-sized enterprises. Manag. Decis. 2023;61:3610–3634. doi: 10.1108/MD-02-2023-0138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altinay L., Madanoglu M., De Vita G., Arasli H., Ekinci Y. The interface between organizational learning capability, entrepreneurial orientation, and SME growth. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016;54:871–891. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y., Li Y., Lee S.H., Bo Chen L. Entrepreneurial orientation, organizational learning, and performance: evidence from China. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011;35:293–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00359.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soomro B.A., Mangi S., Shah N. Strategic factors and significance of organizational innovation and organizational learning in organizational performance. Eur. J. Innovat. Manag. 2021;24:481–506. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-05-2019-0114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michna A. The relationship between organizational learning and SME performance in Poland. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009;33:356–370. doi: 10.1108/03090590910959308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho M.H.-W., Wang F. Unpacking knowledge transfer and learning paradoxes in international strategic alliances: contextual differences matter. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015;24:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santos-Vijande M.L., Sanzo-Pérez M.J., Álvarez-González L.I., Vázquez-Casielles R. Organizational learning and market orientation: interface and effects on performance. Ind. Market. Manag. 2005;34:187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Morales V.J., Ruiz-Moreno A., Llorens-Montes F.J. Effects of technology absorptive capacity and technology proactivity on organizational learning, innovation and performance: an empirical examination. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007;19:527–558. doi: 10.1080/09537320701403540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y., Cooper C.L., Tarba S.Y. Resilience, wellbeing and HRM: a multidisciplinary perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019;30:1227–1238. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1565370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Do H., Budhwar P., Shipton H., Nguyen H.-D., Nguyen B. Building organizational resilience, innovation through resource-based management initiatives, organizational learning and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Res. 2022;141:808–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wernerfelt B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strat. Manag. J. 1984;5:171–180. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250050207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pereira V., Bamel U. Extending the resource and knowledge based view: a critical analysis into its theoretical evolution and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2021;132:557–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zucker L. vol. 13. 1987. pp. 443–464. (Institutional Theories of Organization, Review Literature and Arts of the Americas). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruef M., Scott W.R. A multidimensional model of organizational legitimacy: hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998;43:877. doi: 10.2307/2393619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delmas M.A. The diffusion of environmental management standards in Europe and in the United States: an institutional perspective. Pol. Sci. 2002;35:91–119. doi: 10.1023/A:1016108804453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambec S., Cohen M.A., Elgie S., Lanoie P. The porter hypothesis at 20: can environmental regulation enhance innovation and competitiveness? Rev. Environ. Econ. Pol. 2013;7:2–22. doi: 10.1093/reep/res016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brix J. Building capacity for sustainable innovation: a field study of the transition from exploitation to exploration and back again. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;268 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allameh S.M. Antecedents and consequences of intellectual capital: the role of social capital, knowledge sharing and innovation. J. Intellect. Cap. 2018;19:858–874. doi: 10.1108/JIC-05-2017-0068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yunis M., Tarhini A., Kassar A. The role of ICT and innovation in enhancing organizational performance: the catalysing effect of corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2018;88:344–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed R.R., Akbar W., Aijaz M., Channar Z.A., Ahmed F., Parmar V. The role of green innovation on environmental and organizational performance: moderation of human resource practices and management commitment. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraj E., Matute J., Melero I. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: the role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tourism Manag. 2015;46:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall B.H., Sena V. Appropriability mechanisms, innovation, and productivity: evidence from the UK. Econ. Innovat. N. Technol. 2017;26:42–62. doi: 10.1080/10438599.2016.1202513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inthavong P., Rehman K.U., Masood K., Shaukat Z., Hnydiuk-Stefan A., Ray S. Impact of organizational learning on sustainable firm performance: intervening effect of organizational networking and innovation. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weimer D.L., Vining A.R. 6 Edition. Routledge; New York: Routledge: 2017. Policy Analysis. Revised edition of Policy analysis, 2011, 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dreibelbis R.C., Martin J., Coovert M.D., Dorsey D.W. The looming cybersecurity crisis and what it means for the practice of industrial and organizational psychology. Ind Organ Psychol. 2018;11:346–365. doi: 10.1017/iop.2018.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindeneg K. Instruments in environmental policy? Different approaches. Waste Manag. Res. 1992;10:281–287. doi: 10.1016/0734-242X(92)90105-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Damon M., Sterner T. Policy instruments for sustainable development at rio +20. J. Environ. Dev. 2012;21:143–151. doi: 10.1177/1070496512444735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergquist A.-K., Söderholm K., Kinneryd H., Lindmark M., Söderholm P. Command-and-control revisited: environmental compliance and technological change in Swedish industry 1970–1990. Ecol. Econ. 2013;85:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hojnik J., Ruzzier M. The driving forces of process eco-innovation and its impact on performance: insights from Slovenia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016;133:812–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y. Environmental innovation practices and performance: moderating effect of resource commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014;66:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yi J., Hong J., Chung Hsu W., Wang C. The role of state ownership and institutions in the innovation performance of emerging market enterprises: evidence from China. Technovation. 2017;62–63:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergek A., Berggren C. The impact of environmental policy instruments on innovation: a review of energy and automotive industry studies. Ecol. Econ. 2014;106:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang C.-H. The influence of corporate environmental Ethics on competitive advantage: the mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2011;104:361–370. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0914-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.March J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991;2:71–87. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2.1.71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nielsen J.A., Mathiassen L., Hansen A.M. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning: a critical application of the 4I model. Br. J. Manag. 2018;29:835–850. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Real J.C., Roldán J.L., Leal A. From entrepreneurial orientation and learning orientation to business performance: analysing the mediating role of organizational learning and the moderating effects of organizational size. Br. J. Manag. 2014;25:186–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00848.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chege S.M., Wang D., Suntu S.L. Impact of information technology innovation on firm performance in Kenya. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2020;26:316–345. doi: 10.1080/02681102.2019.1573717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martín-Rojas R., García-Morales V.J., Bolívar-Ramos M.T. Influence of technological support, skills and competencies, and learning on corporate entrepreneurship in European technology firms. Technovation. 2013;33:417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2013.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lynch R., Jin Z. Knowledge and innovation in emerging market multinationals: the expansion paradox. J. Bus. Res. 2016;69:1593–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao Q., Gedajlovic E., Zhang H. Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organ. Sci. 2009;20:781–796. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Junni P., Sarala R.M., Taras V., Tarba S.Y. Organizational ambidexterity and performance: a meta-analysis. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013;27:299–312. doi: 10.5465/AMP.2012.0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahmed S.S., Guozhu J., Mubarik S., Khan M., Khan E. Intellectual capital and business performance: the role of dimensions of absorptive capacity. J. Intellect. Cap. 2020;21:23–39. doi: 10.1108/JIC-11-2018-0199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kusi-Sarpong S., Mubarik M.S., Khan S.A., Brown S., Mubarak M.F. Intellectual capital, blockchain-driven supply chain and sustainable production: role of supply chain mapping. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2022;175 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Truong B.T.T., Van Nguyen P., Vrontis D., Ahmed Z.U. Unleashing corporate potential: the interplay of intellectual capital, knowledge management, and environmental compliance in enhancing innovation and performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024;28:1054–1073. doi: 10.1108/JKM-05-2023-0389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inkinen H.T., Kianto A., Vanhala M. Knowledge management practices and innovation performance in Finland. Baltic J. Manag. 2015;10:432–455. doi: 10.1108/BJM-10-2014-0178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bollen L., Vergauwen P., Schnieders S. Linking intellectual capital and intellectual property to company performance. Manag. Decis. 2005;43:1161–1185. doi: 10.1108/00251740510626254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bahrami M., Arabzad S.M., Ghorbani M. Innovation in market management by utilizing business intelligence: introducing proposed framework. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;41:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.04.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campos S., Dias J.G., Teixeira M.S., Correia R.J. The link between intellectual capital and business performance: a mediation chain approach. J. Intellect. Cap. 2022;23:401–419. doi: 10.1108/JIC-12-2019-0302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rehman S.U., Kraus S., Shah S.A., Khanin D., Mahto R.V. Analyzing the relationship between green innovation and environmental performance in large manufacturing firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;163 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barney J., Wright M., Ketchen D.J. The resource-based view of the firm: ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001;27:625–641. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00114-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wild R.H., Griggs K.A., Downing T. A framework for e‐learning as a tool for knowledge management. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2002;102:371–380. doi: 10.1108/02635570210439463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Inkpen A.C., Crossan M.M. Believing is seeing: joint ventures and organizational learning. J. Manag. Stud. 1995;32:595–618. [Google Scholar]

- 63.García-Morales V.J., Lloréns-Montes F.J., Verdú-Jover A.J. Influence of personal mastery on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation in large firms and SMEs. Technovation. 2007;27:547–568. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2007.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hurley R.F., Hult G.T.M. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: an integration and empirical examination. J Mark. 1998;62:42–54. doi: 10.2307/1251742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.García‐Morales V.J., Llorens‐Montes F.J., Verdú‐Jover A.J. Antecedents and consequences of organizational innovation and organizational learning in entrepreneurship. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2006;106:21–42. doi: 10.1108/02635570610642940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Zubielqui G.C., Lindsay N., Lindsay W., Jones J. Knowledge quality, innovation and firm performance: a study of knowledge transfer in SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2019;53:145–164. doi: 10.1007/s11187-018-0046-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alrowwad A., Abualoush S.H., Masa’deh R. Innovation and intellectual capital as intermediary variables among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and organizational performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2020;39:196–222. doi: 10.1108/JMD-02-2019-0062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agarwal R., Prasad J. A conceptual and operational definition of personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998;9:204–215. doi: 10.1287/isre.9.2.204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen P.V., Huynh H.T.N., Lam L.N.H., Le T.B., Nguyen N.H.X. The impact of entrepreneurial leadership on SMEs' performance: the mediating effects of organizational factors. Heliyon. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Legate A.E., Hair J.F., Chretien J.L., Risher J.J. PLS-SEM: prediction-oriented solutions for HRD researchers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2023;34:91–109. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ali F., Rasoolimanesh S.M., Sarstedt M., Ringle C.M., Ryu K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hospit. Manag. 2018;30:514–538. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. second ed. SAGE Publication, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA., CA: 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hair J.F., Sarstedt M., Hopkins L., Kuppelwieser V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014;26:106–121. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hair J.F., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long. Range Plan. 2013;46:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chin W.W. Handbook of Partial Least Squares. Springer; New York: 2010. How to write up and report PLS analyses; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci. 2015;43:115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collaboration. 2015;11:1–10. doi: 10.4018/ijec.2015100101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.