Abstract

Aims

The study aims to explore the associations of eczema, Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index (CDAI), with depression symptoms in adults based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) database.

Methods

In total, 3,402 participant data were extracted from the NHANES 2005–2006. The relationship between eczema, CDAI, and depression symptoms was explored by utilizing weighted univariate and multivariate logistic regression models, presenting as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The additive interaction between eczema, CDAI, and depression symptoms was measured by relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) and the attributable proportion of interaction (AP). Subsequently, the associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression were also explored in different gender, body mass index (BMI), and smoking subgroups.

Results

Of the 3,402 participants included, the mean age was 46.76 (0.83) years old, and 174 (5.11%) participants had depression symptoms. In the adjusted model, both eczema (OR = 3.60, 95%CI: 2.39–5.40) and CDAI (OR = 1.97, 95%CI: 1.19–3.27) were associated with a higher prevalence of depression symptoms. Compared to the participants with high CDAI and no eczema, those participants with low CDAI (eczema: OR = 7.30, 95%CI: 4.73–11.26; non-eczema: OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.06–3.19) have higher odds of depression symptoms, no matter have eczema or not. When under low CDAI levels, eczema was associated with increased odds of depression symptoms (OR = 3.76, 95%CI: 2.34–6.03). When under low CDAI level, eczema was also related to elevated odds of depression symptoms in those males, females, BMI <25, BMI ≥25, non-smoking, and smoking.

Conclusion

CDAI could modulate the association of eczema with depression symptoms in adults.

Keywords: Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index, eczema, depression, moderating, NHANES

1. Introduction

Eczema, or atopic dermatitis, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritus, recurrent eczematous patches, and plaques (1). Typically manifesting in early childhood, it may persist into adulthood or even emerge later in life (1). In the United States (U.S), approximately 10–20% of adults experience eczema at some point (2, 3). Beyond the physical discomfort it causes, eczema profoundly impacts mental health (4). Adults with eczema are at an elevated risk of developing psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances (5, 6). The burden of eczema transcends its dermatological symptoms, resulting a significant reduction in quality of life and increased healthcare utilization due to both physical discomfort and associated psychological distress (4).

Depression, a common comorbidity of eczema, further exacerbates the considerable burden of the condition (7). Individuals with eczema are at a heightened risk of experiencing depression compared to those without the disorder (8). The mechanisms underlying this association are complex and may involve chronic stress due to the physical symptoms of eczema, social stigma, sleep disturbances, and the psychological impact of living with a visible chronic condition (8–10). Understanding the relationship between eczema and depression is essential for developing effective interventions that address both the dermatological and psychological aspects of the disease.

Oxidative stress is a pivotal pathophysiological mechanism implicated in both eczema and depression (11, 12). The Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index (CDAI) is a comprehensive measure of dietary antioxidant intake, encompassing a broad spectrum of antioxidants, including vitamins C and E, carotenoids, and flavonoids (13). Research indicates that CDAI was inversely associated with depression in the general population (14). Additionally, dietary antioxidant intake has shown a negative correlation with childhood eczema (15). Given these associations, CDAI may serve as a potential moderator influencing the relationship between eczema and depression. Hence, this study aims to investigate the moderating effect of CDAI on the association between eczema and depression symptoms in adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), a major program by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), assesses the nutrition and health status of both adults and children in the U.S. The NHANES protocol has received approval from the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, with all participants providing informed consent before the survey. The ethical approval was granted with an exemption from the Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine.

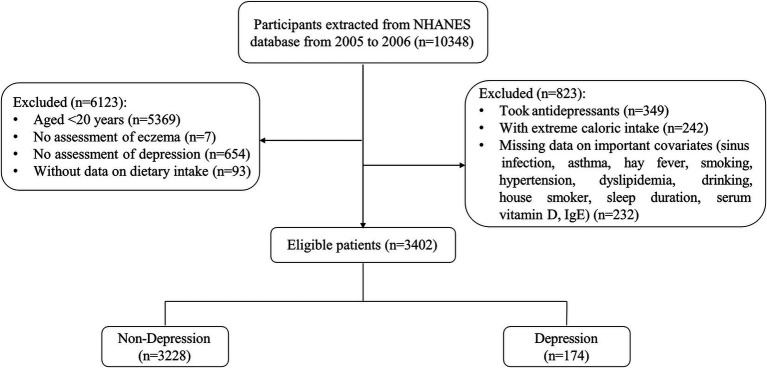

Data for participants were extracted from the NHANES 2005–2006 cycle, the only period with complete questionnaires on eczema. The participants included individuals aged ≥20 years old, who having an assessment for eczema and depression symptoms, as well as dietary intake data. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) individuals taking antidepressants, (2) extreme caloric intake (defined as <600 kcal or > 4,200 kcal per day for men, and < 500 kcal or > 3,600 kcal per day for women) (16), and (3) missing data on important covariates.

2.2. Determination of eczema

Eczema diagnosis was based on self-reported data from the NHANES questionnaire, where individuals indicated a positive response to the query, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have eczema” (17).

2.3. CDAI assessment

CDAI was calculated using six dietary antioxidant micronutrients: vitamins A, C, E, zinc, magnesium, and selenium, following Wright’s method (17). Each nutrient was standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation to estimate CDAI. Standardized intakes were then summarized with equal weighting to derive the composite CDAI. In our study, the CDAI score was categorized into two levels based on the median.

2.4. Depression assessment

Depression symptoms were defined using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a 9-item screening tool assessing the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks via face-to-face mobile examination center interview (18). Respondents rated symptoms such as anhedonia, depressed mood, sleep disturbance, fatigue, appetite changes, low self-esteem, concentration problems, psychomotor disturbances, and suicidal ideation on a 0–3 scale. The PHQ-9 total score ranges from 0 to 27 points, with a score ≥ 10 indicating clinically relevant depressive symptoms (19).

2.5. Covariates

The covariates in this study included race, poverty income ratio (PIR), marriage, education level, sleep duration, smoking, house smoker, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and serum vitamin D. Smoking status was determined according to the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life.” Hypertension, as measured by NHANES, was self-reported, applying antihypertensive drugs and blood pressure measurements consistent with previous studies (20, 21). Self-reported hypertension was assessed by participants having a positive answer to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure.” Hypertension, measured by the NHANES, was defined as a mean systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure or ≥ 80 mmHg, based on four measurements (22). Participants who were diagnosed with diabetes were defined as follows: (1) fasting blood glucose ≥7 mmol/L, (2) Hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%, (3) self-reported diabetes which was diagnosed by professional physicians before, (4) taking insulin or other hypoglycemic drugs (23, 24). The medical conditions section, identified by the variable name prefix MCQ, includes self-and proxy-reported interview data on a wide range of health conditions and medical history for children and adults. Questions “Has a doctor or other health professional ever informed you that you had congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack, stroke, etc.?” (labeled MCQ 160 B-F in household questionnaires administered during home interviews) were utilized to identify participants with a history of CVD if they answered “yes” to any of these questions.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Considering the recommendations of NHNAES, appropriate sample weights (SDMVPSU, SDMVSTRA, WTMEC2YR) were applied for all analyses. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard error (S.E), and weight t-tests were utilized for comparisons between the depression and non-depression groups. The constitutional ratio was provided for categorical variables, and Chi-square tests were employed for comparisons between the two groups. Potential covariates were selected according to the weighted logistic regression models, with detailed results of covariates selection presented in Supplementary Table S1. Weighted multivariable logistic regression models were employed to investigate the associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression symptoms, with results reported as 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and odds ratios (ORs). In addition, the additive interaction between eczema, CDAI, and depression symptoms was measured by relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) and the attributable proportion of interaction (AP). When the confidence interval of RERI and AP contained 0, there was no additive interaction. Subsequently, the associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression were also explored in different gender, body mass index (BMI), and smoking subgroups. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.3 (2023-03-15 ucrt), with a significance threshold of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of participants

In total, 3,402 participants were included in the current study (Figure 1). The basic characteristics based on depression were presented in Table 1. Of those participants, the mean age was 46.76 (0.83) years old, and 50.92% were female. And 174 (5.11%) individuals have depression symptoms Statistical differences were found between depression and non-depression groups in PIR, marriage, education level, physical activity, sleep duration, smoking, house smoker, hypertension, diabetes, CVD, serum vitamin D, eczema, CDAI, and six components of CDAI (all p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Flowing chart of the selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | Total (n = 3,402) | Depression | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 3,228) | Yes (n = 174) | |||

| Age, years, mean (±S.E) | 46.76 (±0.83) | 46.81 (±0.82) | 45.70 (±2.10) | 0.565 a |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.574 b | |||

| Female | 1752 (50.92) | 1,654 (50.82) | 98 (52.97) | |

| Male | 1,650 (49.08) | 1,574 (49.18) | 76 (47.03) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.126 b | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1710 (72.45) | 1,638 (72.79) | 72 (65.00) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 762 (11.06) | 707 (10.73) | 55 (18.32) | |

| Mexican American | 697 (8.03) | 659 (7.97) | 38 (9.37) | |

| Other Race | 233 (8.46) | 224 (8.51) | 9 (7.32) | |

| PIR, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| <1.85 | 1,219 (24.57) | 1,119 (23.49) | 100 (48.29) | |

| ≥1.85 | 2076 (72.90) | 2004 (73.89) | 72 (51.30) | |

| Unknown | 107 (2.53) | 105 (2.62) | 2 (0.42) | |

| Marriage, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| Married/Living with partner | 2,211 (67.63) | 2,118 (68.28) | 93 (53.24) | |

| Single/Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 1,191 (32.37) | 1,110 (31.72) | 81 (46.76) | |

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| Below high school | 904 (16.60) | 834 (16.12) | 70 (27.10) | |

| High school/GED or Equivale | 802 (24.43) | 749 (23.88) | 53 (36.52) | |

| Above high school | 1,696 (58.97) | 1,645 (60.00) | 51 (36.39) | |

| Height, cm, mean (±S.E) | 169.03 (±0.24) | 169.07 (±0.24) | 168.30 (±0.85) | 0.374 a |

| Weight, kg, mean (±S.E) | 81.70 (±0.84) | 81.60 (±0.83) | 84.04 (±2.65) | 0.337 a |

| BMI, kg/m2, n (%) | 0.919 b | |||

| <25 | 1,024 (33.15) | 973 (33.13) | 51 (33.66) | |

| ≥25 | 2,378 (66.85) | 2,255 (66.87) | 123 (66.34) | |

| PA, MET·min/week, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| <450 | 670 (20.49) | 645 (20.69) | 25 (16.07) | |

| ≥450 | 1,433 (47.34) | 1,396 (48.36) | 37 (24.92) | |

| Unknown | 1,299 (32.17) | 1,187 (30.95) | 112 (59.01) | |

| Sleep duration, hours, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| 7–9 | 2054 (62.80) | 1990 (63.85) | 64 (39.74) | |

| <7 | 1,264 (35.24) | 1,159 (34.15) | 105 (59.25) | |

| >9 | 84 (1.96) | 79 (2.00) | 5 (1.00) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 0.001 b | |||

| No | 1808 (51.88) | 1744 (52.92) | 64 (29.21) | |

| Yes | 1,594 (48.12) | 1,484 (47.08) | 110 (70.79) | |

| Drinking, n (%) | 0.400 b | |||

| No | 476 (11.33) | 451 (11.45) | 25 (8.61) | |

| Yes | 2,926 (88.67) | 2,777 (88.55) | 149 (91.39) | |

| House smoker, n (%) | 0.001 b | |||

| 0 | 2,801 (82.07) | 2,680 (82.73) | 121 (67.59) | |

| 1–2 | 548 (16.18) | 501 (15.68) | 47 (27.22) | |

| ≥3 | 53 (1.75) | 47 (1.59) | 6 (5.19) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.010 b | |||

| No | 1,662 (49.93) | 1,595 (50.70) | 67 (33.06) | |

| Yes | 1740 (50.07) | 1,633 (49.30) | 107 (66.94) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0.011 b | |||

| No | 2,971 (90.43) | 2,833 (90.75) | 138 (83.41) | |

| Yes | 431 (9.57) | 395 (9.25) | 36 (16.59) | |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 0.504 b | |||

| No | 968 (29.46) | 927 (29.62) | 41 (25.93) | |

| Yes | 2,434 (70.54) | 2,301 (70.38) | 133 (74.07) | |

| CVD, n (%) | 0.002 b | |||

| No | 3,070 (92.28) | 2,928 (92.58) | 142 (85.65) | |

| Yes | 332 (7.72) | 300 (7.42) | 32 (14.35) | |

| Asthma, n (%) | 0.304 b | |||

| No | 3,003 (87.39) | 2,854 (87.54) | 149 (83.95) | |

| Yes | 399 (12.61) | 374 (12.46) | 25 (16.05) | |

| Hay fever, n (%) | 0.334 b | |||

| No | 3,057 (87.15) | 2,899 (86.99) | 158 (90.75) | |

| Yes | 345 (12.85) | 329 (13.01) | 16 (9.25) | |

| Sinus infection, n (%) | 0.112 b | |||

| No | 2,943 (84.66) | 2,803 (85.03) | 140 (76.45) | |

| Yes | 459 (15.34) | 425 (14.97) | 34 (23.55) | |

| Topical steroids, n (%) | 0.461 b | |||

| No | 3,389 (99.52) | 3,215 (99.50) | 174 (100.00) | |

| Yes | 13 (0.48) | 13 (0.50) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Topical emollients, n (%) | 0.829 b | |||

| No | 3,401 (99.99) | 3,227 (99.99) | 174 (100.00) | |

| Yes | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Antihistamines, n (%) | 0.805 b | |||

| No | 3,310 (95.96) | 3,142 (95.98) | 168 (95.50) | |

| Yes | 92 (4.04) | 86 (4.02) | 6 (4.50) | |

| Antipsychotics, n (%) | 0.126 b | |||

| No | 3,386 (99.38) | 3,214 (99.46) | 172 (97.59) | |

| Yes | 16 (0.62) | 14 (0.54) | 2 (2.41) | |

| Energy, kcal, mean (±S.E) | 2098.19 (±25.09) | 2102.43 (±24.67) | 2005.02 (±56.58) | 0.066 a |

| Serum vitamin D, nmol/L, mean (±S.E) | 61.11 (±1.22) | 61.36 (±1.22) | 55.57 (±2.45) | 0.020 a |

| IgE, kU/L, mean (±S.E) | 133.51 (±7.75) | 133.86 (±8.23) | 125.79 (±21.79) | 0.750 a |

| Eczema, n (%) | <0.001 b | |||

| No | 3,190 (92.67) | 3,039 (93.06) | 151 (84.06) | |

| Yes | 212 (7.33) | 189 (6.94) | 23 (15.94) | |

| CDAI, Mean (±S.E) | 0.23 (±0.09) | 0.29 (±0.09) | −1.23 (±0.33) | <0.001 a |

| CDAI, n (%) | 0.002 b | |||

| High | 851 (26.88) | 820 (27.48) | 31 (13.71) | |

| Low | 2,551 (73.12) | 2,408 (72.52) | 143 (86.29) | |

| Vitamin A, mcg, mean (±S.E) | 606.11 (±15.10) | 610.96 (±14.76) | 499.73 (±44.14) | 0.016 a |

| Vitamin C, mg, mean (±S.E) | 82.85 (±2.32) | 83.90 (±2.28) | 59.72 (±7.41) | 0.005 a |

| Vitamin E, mg, mean (±S.E) | 7.14 (±0.15) | 7.20 (±0.15) | 5.87 (±0.42) | 0.007 a |

| Magnesium, mg, mean (±S.E) | 290.35 (±2.79) | 292.34 (±2.70) | 246.65 (±9.46) | <0.001 a |

| Selenium, mcg, mean (±S.E) | 107.83 (±1.57) | 108.47 (±1.56) | 93.87 (±4.18) | 0.002 a |

| Zinc, mg, Mean (±S.E) | 12.41 (±0.31) | 12.49 (±0.33) | 10.61 (±0.64) | 0.019 a |

S.E, standard error; aWeighted t-test; bRao-Scott Chi-square test; CDAI, composite dietary antioxidant index; PIR, income-to-poverty ratio; BMI, body mass index; PA, physical activity; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

3.2. Associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression symptoms

The associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression were illustrated in Table 2. After adjusting race, PIR, marriage, education level, sleep duration, smoking, house smoker, hypertension, diabetes, CVD, and serum vitamin D, both eczema (OR = 3.60, 95%CI: 2.39–5.40) and CDAI (OR = 1.97, 95%CI: 1.19–3.27) were associated with higher prevalence of depression symptoms. Compared to the participants with high CDAI and no eczema, those participants with low CDAI (eczema: OR = 7.30, 95%CI: 4.73–11.26; non-eczema: OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.06–3.19) have higher odds of depression symptoms, no matter have eczema or not. There was a significant synergistic effect of eczema and low CDAI level on depression symptoms (RERI = 4.22, 95%CI: 0.54–7.90; AP = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.20–0.95). We further explored the association of eczema with depression symptoms under different CDAI levels (Table 3). In individuals with high CDAI levels, no statistical significance relationship was found between eczema and depression symptoms (OR = 2.56, 95%CI: 0.61–10.83). When under low CDAI level, eczema was associated with increased odds of depression symptoms (OR = 3.76, 95%CI: 2.34–6.03).

Table 2.

The associations of eczema, CDAI with depression symptoms.

| Variables | Unadjusted | Model 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Eczema | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.54 (1.82–3.55) | <0.001 | 3.60 (2.39–5.40) | <0.001 |

| CDAI | ||||

| High | Ref | Ref | ||

| Low | 2.38 (1.48–3.85) | <0.001 | 1.97 (1.19–3.27) | 0.009 |

| CDAI and Eczema | ||||

| Eczema (no) and CDAI (high) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema (no) and CDAI (low) | 2.22 (1.31–3.75) | 0.003 | 1.84 (1.06–3.19) | 0.030 |

| Eczema (yes) and CDAI (high) | 1.51 (0.53–4.29) | 0.436 | 2.24 (0.78–6.41) | 0.134 |

| Eczema (yes) and CDAI (low) | 6.34 (3.96–10.17) | <0.001 | 7.30 (4.73–11.26) | <0.001 |

| Measures | Measure (95% CI) | Measure (95% CI) | ||

| RERI | 3.62 (0.66–6.57) | 4.22 (0.54–7.90) | ||

| AP | 0.57 (0.24–0.90) | 0.58 (0.20–0.95) | ||

OR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence intervals; Ref, reference; CDAI, composite dietary antioxidant index; RERI, relative excess risk of interaction; AP, attributable proportion; Unadjusted was crude model; Model 1 adjusting race, PIR, marriage, education, sleep duration, smoking, house smoker, hypertension, diabetes, CVD, and serum Vitamin D.

Table 3.

The association of eczema with depression symptoms under different CDAI level.

| Variables | Unadjusted | Model 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| CDAI (high) | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.51 (0.53–4.29) | 0.436 | 2.56 (0.61–10.83) | 0.200 |

| CDAI (low) | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.86 (1.84–4.45) | <0.001 | 3.76 (2.34–6.03) | <0.001 |

OR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence intervals; Ref, reference; CDAI, composite dietary antioxidant index; Unadjusted was crude model; Model 1 adjusting race, PIR, marriage, education, sleep duration, smoking, house smoker, hypertension, diabetes, CVD, and serum Vitamin D.

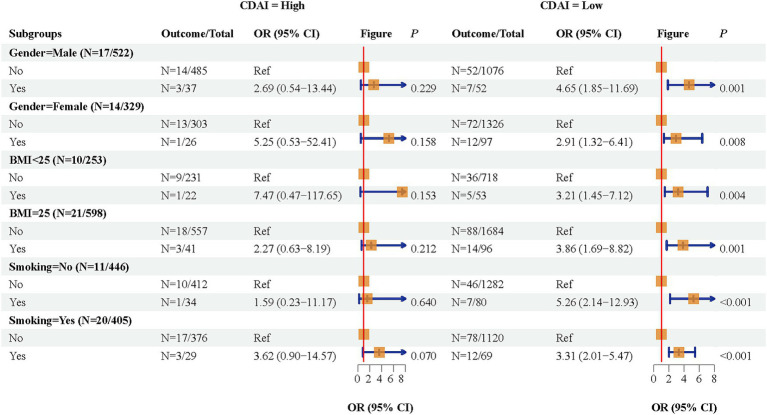

3.3. Subgroup analysis

The associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression were further explored in various gender, BMI, and smoking subgroups (Table 4) (Figure 2). When under low CDAI level, eczema was related to elevated odds of depression symptoms in those males (OR = 4.65, 95%CI: 1.85–11.69), females (OR = 2.91, 95%CI: 1.32–6.41), BMI <25 (OR = 3.21, 95%CI: 1.45–7.12), BMI ≥25 (OR = 3.86, 95%CI: 1.69–8.82), non-smoking (OR = 5.26, 95%CI: 2.14–12.93), and smoking (OR = 3.31, 95%CI: 2.015.47). When individuals experienced high CDAI levels, no associations were found between eczema and depression symptoms of diverse subgroups. The interaction effect of CDAI and eczema on depression was shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

The association of eczema with depression symptoms under different CDAI level in subgroups.

| Variables | CDAI (high) | CDAI (low) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome/Total | OR (95% CI) | P | Outcome/Total | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Gender-Male (n = 17/522) | ||||||

| No | n = 14/485 | Ref | n = 52/1076 | Ref | ||

| Yes | n = 3/37 | 2.69 (0.54–13.44) | 0.229 | n = 7/52 | 4.65 (1.85–11.69) | 0.001 |

| Gender-Female (n = 14/329) | ||||||

| No | n = 13/303 | Ref | n = 72/1326 | Ref | ||

| Yes | n = 1/26 | 5.25 (0.53–52.41) | 0.158 | n = 12/97 | 2.91 (1.32–6.41) | 0.008 |

| BMI <25 (n = 10/253) | ||||||

| No | n = 9/231 | Ref | n = 36/718 | Ref | ||

| Yes | n = 1/22 | 7.47 (0.47–117.65) | 0.153 | n = 5/53 | 3.21 (1.45–7.12) | 0.004 |

| BMI ≥25 (n = 21/598) | ||||||

| No | n = 18/557 | Ref | n = 88/1684 | Ref | ||

| Yes | n = 3/41 | 2.27 (0.63–8.19) | 0.212 | n = 14/96 | 3.86 (1.69–8.82) | 0.001 |

| Smoking-No (n = 11/446) | ||||||

| No | n = 10/412 | Ref | n = 46/1282 | Ref | ||

| Yes | n = 1/34 | 1.59 (0.23–11.17) | 0.640 | n = 7/80 | 5.26 (2.14–12.93) | <0.001 |

| Smoking-Yes (n = 20/405) | ||||||

| No | n = 17/376 | Ref | n = 78/1120 | Ref | ||

| Yes | n = 3/29 | 3.62 (0.90–14.57) | 0.070 | n = 12/69 | 3.31 (2.01–5.47) | <0.001 |

Figure 2.

Associations of eczema, CDAI, with depression symptoms in different gender, BMI, smoking subgroups.

Table 5.

The combined effect of CDAI and eczema on the odds of depression in subgroups.

| Subgroups | Outcome/Total | Unadjusted | Model 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Gender = Female | n = 98/1752 | ||||

| CDAI and Eczema | |||||

| Eczema = No and CDAI=High | n = 13/303 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema = No and CDAI = Low | n = 72/1326 | 2.12 (0.89–5.07) | 0.117 | 1.94 (0.74–5.05) | 0.248 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI=High | n = 1/26 | 0.94 (0.12–7.57) | 0.954 | 1.80 (0.25–12.70) | 0.588 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI = Low | n = 12/97 | 5.37 (2.14–13.46) | 0.004 | 6.06 (2.28–16.13) | 0.023 |

| P for trend | 0.003 | P for trend | 0.022 | ||

| RERI | 3.31 (−1.42–8.05) | 3.33 (−3.09–9.74) | |||

| AP | 0.62 (0.09–1.15) | 0.55 (−0.17–1.27) | |||

| SI | 4.13 (0.31–54.29) | 2.92 (0.27–32.13) | |||

| Gender = Male | n = 76/1650 | ||||

| CDAI and Eczema | |||||

| Eczema = No and CDAI=High | n = 14/485 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema = No and CDAI = Low | n = 52/1076 | 2.30 (1.24–4.29) | 0.022 | 1.85 (0.93–3.72) | 0.157 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI=High | n = 3/37 | 1.95 (0.72–5.24) | 0.213 | 2.42 (0.91–6.41) | 0.151 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI = Low | n = 7/52 | 8.35 (3.48–20.02) | <0.001 | 9.61 (3.36–27.52) | 0.013 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | P for trend | 0.014 | ||

| RERI | 5.10 (−1.24–11.45) | 6.34 (−3.11–15.79) | |||

| AP | 0.61 (0.27–0.95) | 0.66 (0.27–1.05) | |||

| SI | 3.27 (1.03–10.34) | 3.79 (0.89–16.09) | |||

| BMI < 25 | n = 51/1024 | ||||

| CDAI and Eczema | |||||

| Eczema = No and CDAI=High | n = 9/231 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema = No and CDAI = Low | n = 36/718 | 1.95 (0.80–4.76) | 0.167 | 1.75 (0.73–4.21) | 0.276 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI=High | n = 1/22 | 0.92 (0.13–6.64) | 0.934 | 1.36 (0.18–10.43) | 0.784 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI = Low | n = 5/53 | 5.77 (2.20–15.14) | 0.004 | 6.41 (2.34–17.55) | 0.022 |

| P for trend | 0.005 | P for trend | 0.023 | ||

| RERI | 3.90 (−1.37–9.17) | 4.30 (−1.72–10.32) | |||

| AP | 0.68 (0.21–1.14) | 0.67 (0.18–1.16) | |||

| SI | 5.48 (0.29–102.92) | 4.87 (0.32–74.43) | |||

| BMI ≥ 25 | n = 123/2378 | ||||

| CDAI and Eczema | |||||

| Eczema = No and CDAI=High | n = 18/557 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema = No and CDAI = Low | n = 88/1684 | 2.36 (1.32–4.20) | 0.013 | 1.85 (0.97–3.53) | 0.135 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI=High | n = 3/41 | 1.95 (0.76–5.01) | 0.192 | 2.45 (0.94–6.36) | 0.140 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI = Low | n = 14/96 | 6.65 (3.21–13.75) | <0.001 | 7.54 (3.58–15.88) | 0.006 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | P for trend | 0.007 | ||

| RERI | 3.34 (−1.76–8.45) | 4.24 (−1.94–10.42) | |||

| AP | 0.50 (0.00–1.00) | 0.56 (0.06–1.07) | |||

| SI | 2.45 (0.64–9.45) | 2.84 (0.61–13.24) | |||

| Smoking = No | n = 64/1808 | ||||

| CDAI and Eczema | |||||

| Eczema = No and CDAI=High | n = 10/412 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema = No and CDAI = Low | n = 46/1282 | 2.10 (0.91–4.83) | 0.107 | 1.77 (0.72–4.35) | 0.268 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI=High | n = 1/34 | 1.29 (0.16–10.34) | 0.816 | 1.53 (0.18–12.78) | 0.709 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI = Low | n = 7/80 | 7.46 (2.40–23.17) | 0.005 | 9.93 (2.88–34.25) | 0.015 |

| P for trend | 0.003 | P for trend | 0.014 | ||

| RERI | 5.07 (−2.81–12.95) | 7.63 (−3.71–18.96) | |||

| AP | 0.68 (0.18–1.18) | 0.77 (0.36–1.17) | |||

| SI | 4.66 (0.37–58.12) | 6.85 (0.36–131.66) | |||

| Smoking = Yes | n = 110/1594 | ||||

| CDAI and Eczema | |||||

| Eczema = No and CDAI=High | n = 17/376 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Eczema = No and CDAI = Low | n = 78/1120 | 2.36 (1.27–4.36) | 0.018 | 1.87 (1.01–3.44) | 0.103 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI=High | n = 3/29 | 1.64 (0.66–4.03) | 0.305 | 2.51 (1.13–5.57) | 0.073 |

| Eczema = Yes and CDAI = Low | n = 12/69 | 6.33 (3.31–12.10) | <0.001 | 6.62 (3.82–11.46) | 0.001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | P for trend | 0.001 | ||

| RERI | 3.33 (0.17–6.49) | 3.24 (−0.31–6.79) | |||

| AP | 0.53 (0.22–0.84) | 0.49 (0.12–0.86) | |||

| SI | 2.67 (1.02–7.00) | 2.37 (0.88–6.38) | |||

OR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence intervals; Ref, reference; CDAI, composite dietary antioxidant index; Model 1 adjusting race, PIR, marriage, education, sleep duration, smoking, house smoker, hypertension, diabetes, CVD, and serum Vitamin D.

4. Discussion

Eczema was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of depression symptoms. Similarly, a lower level of CDAI was also associated with a higher prevalence of depression symptoms. Importantly, our study found that low CDAI levels could modulate the relationship between eczema and depression symptoms. Specifically, individuals with both eczema and low CDAI levels exhibited heightened odds of depression compared to those with higher CDAI levels. This indicated the potential protective role of dietary antioxidants in mitigating depressive symptoms associated with chronic inflammatory conditions like eczema.

Our finding was consistent with existing literature reporting the relationship between eczema and depression (7, 25, 26). Chiesa Fuxench et al. (7) reported an increased likelihood of anxiety or depression in patients with eczema, with similar results in Cheng’s research (8). There is a greater prevalence of depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, and suicidal ideation among individuals with eczema (25). Patients with eczema should be vigilant about their mental health. Anyway, our study uniquely contributes by highlighting the role of dietary antioxidants in modifying the association of CDAI with depression symptoms. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the direct impact of inflammatory processes on mental health outcomes, whereas our research underscores the importance of dietary factors in modulating this association (27). Vitamin D and E supplementations demonstrate effectiveness to some extent in improving eczema severity (28). An antioxidant diet is a protective factor against depression, and a negative relationship exists between CDAI and depression (14). Our findings added the reference to the beneficial effect of antioxidants on mental health among patients with eczema.

The mechanisms underlying the moderating of low CDAI levels on the association between eczema and depression symptoms require comprehensive investigation. Dietary antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, carotenoids, and flavonoids, are essential in neutralizing reactive oxygen species and mitigating inflammation (13). Individuals with eczema experience heightened oxidative stress due to increased inflammation and reactive oxygen species production (1). Oxidative stress was also linked to neuronal damage and altered neurotransmitter function implicated in depression (12). Thus, higher antioxidant intake, as indicated by CDAI, may alleviate oxidative stress in eczema patients, thus reducing depressive symptoms. Secondly, dietary antioxidants possess anti-inflammatory properties that may directly benefit both eczema and depression. Eczema, characterized by skin inflammation, correlates with elevated cutaneous and serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-22 (29). It has been suggested that IL-13, by binding to dopaminergic neurons and stimulating astrocyte production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, along with oxidative stress, could contribute to neuronal damage in the ventral tegmental and substantia nigra, potentially predisposing individuals to depression and suicidality (30, 31). By mitigating inflammation, antioxidants could potentially mitigate the systemic inflammatory response associated with eczema, potentially easing depressive symptoms. Thirdly, the gut-skin and the gut-brain axes provide additional mechanistic insights. Dietary antioxidants can influence gut microbiota composition and function, thereby modulating immune responses and the production of neuroactive compounds (32). Dysbiosis and impaired gut barrier function observed in eczema patients have been linked to both skin inflammation and depressive symptoms (33). Increased antioxidants intake may restore gut microbial balance, yielding beneficial effects on both eczema severity and mood disorders.

We found that subgroups stratified by gender, BMI, and smoking status consistently demonstrated that low levels of the CDAI intensified the association between eczema and depression symptoms. This suggests that the beneficial effects of dietary antioxidants might be widespread, impacting various demographic groups similarly. Women may experience different hormonal fluctuations that interact with antioxidant levels and their mental health outcomes, while individuals with higher BMI might have altered metabolism affecting the efficacy of antioxidants. Additionally, smoking status could play a crucial role, as smokers often have lower antioxidant levels due to lifestyle factors, potentially exacerbating both eczema and depressive symptoms.

Our findings underscore the significant role that dietary interventions can play in managing mental health outcomes for individuals with eczema. Specifically, healthcare providers should evaluate and optimize antioxidant intake in patients with eczema, as this may help mitigate the risk of depression. We recommend implementing dietary assessments that focus on patients’ current antioxidant consumption. Providers can guide patients toward a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and whole grains-key sources of dietary antioxidants-potentially alleviating both eczema symptoms and depressive symptoms. In practical terms, healthcare providers can create structured dietary plans that incorporate these foods, alongside educational resources that highlight the benefits of antioxidant-rich diets. Collaborating with nutritionists or dietitians can further enhance these efforts, providing patients with tailored dietary strategies that align with their preferences and lifestyle constraints. Additionally, addressing the feasibility of such dietary changes is crucial; for instance, practitioners could explore local food resources, budget-friendly options, and simple recipes to make healthier eating more accessible.

The strengths of our study lie in its utilization of a large, nationally representative sample from the NHANES database, facilitating robust statistical analyses. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to establish causality between CDAI, eczema, and depression. Future longitudinal studies are necessary to clarify the temporal relationships and long-term effects of dietary antioxidants on mental health outcomes. Secondly, dietary intake data were obtained according to the 24-h dietary recall interview, which may introduce potential recall bias. Further research incorporating objective measures of antioxidant status, such as biomarkers, would provide more accurate estimates of dietary antioxidant effects on eczema and depression. Lastly, residual confounding from unmeasured variables in the database cannot be discounted.

5. Conclusion

Our study shows that low levels of the CDAI moderate the relationship between eczema and depressive symptoms in U.S. adults. These results suggest that individuals with eczema may experience heightened depressive symptoms when CDAI levels are low. Dietary interventions aimed at increasing antioxidant intake may play a crucial role in the mental health management of individuals with eczema.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: NHANES (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine for the studies involving humans because Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Jiangsu Province Hospital of Chinese Medicine. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TZ: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YW: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1470833/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Frazier W, Bhardwaj N. Atopic dermatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. (2020) 101:590–8. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. (2016) 387:1109–22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00149-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg JI. Atopic dermatitis in adults. Med Clin North Am. (2020) 104:157–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: atopic dermatitis and health-related quality of life. Acta Derm Venereol. (2020) 100:10.2340/00015555-3511. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schonmann Y, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, Abuabara K, Roberts A, Smeeth L, et al. Atopic eczema in adulthood and risk of depression and anxiety: a population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2020) 8:248–257.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.030, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthewman J, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, Adesanya EI, Smith CH, Roberts A, et al. Anxiety and depression in people with eczema or psoriasis: a comparison of associations in UK biobank and linked primary care data. Clin Epidemiol. (2023) 15:891–9. doi: 10.2147/clep.S417176, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, Boyle J, Fonacier L, Gelfand JM, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. (2019) 139:583–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng BT, Silverberg JI. Depression and psychological distress in us adults with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2019) 123:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.06.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinh NM, Trang VTT, Dac Thuy LN, Tam HTX, Hang LTT, Bac PV. The anxiety and depression disorder in adults with atopic dermatitis: experience of a dermatology hospital. Dermatol Reports. (2023) 15:9524. doi: 10.4081/dr.2022.9524, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasseeh AN, Elezbawy B, Korra N, Tannira M, Dalle H, Aderian S, et al. Burden of atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther. (2022) 12:2653–68. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00819-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minzaghi D, Pavel P, Kremslehner C, Gruber F, Oberreiter S, Hagenbuchner J, et al. Excessive production of hydrogen peroxide in mitochondria contributes to atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. (2023) 143:1906–1918.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2023.03.1680, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt S, Nagappa AN, Patil CR. Role of oxidative stress in depression. Drug Discov Today. (2020) 25:1270–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He H, Chen X, Ding Y, Chen X, He X. Composite dietary antioxidant index associated with delayed biological aging: a population-based study. Aging. (2024) 16:15–27. doi: 10.18632/aging.205232, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao L, Sun Y, Cao R, Wu X, Huang T, Peng W. Non-linear association between composite dietary antioxidant index and depression. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:988727. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.988727, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Li H. Association between dietary antioxidants intake and childhood eczema: results from the NHANES database. J Health Popul Nutr. (2024) 43:12. doi: 10.1186/s41043-024-00501-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidelmann SB, Claggett B, Cheng S, Henglin M, Shah A, Steffen LM, et al. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: a prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. (2018) 3:e419–28. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30135-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou T, Chen S, Mao J, Fei Y, Yu X, Han L. Composite dietary antioxidant index is negatively associated with olfactory dysfunction among adults in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Res. (2024) 124:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2024.02.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorgensen D, White GE, Sekikawa A, Gianaros P. Higher dietary inflammation is associated with increased odds of depression independent of Framingham risk score in the National Health and nutrition examination survey. Nutr Res. (2018) 54:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2018.03.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu JP, Zeng RX, Zhang YZ, Lin SS, Tan JW, Zhu HY, et al. Systemic inflammation markers and the prevalence of hypertension: a NHANES cross-sectional study. Hypertens Res. (2023) 46:1009–19. doi: 10.1038/s41440-023-01195-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai Y, Chen M, Zhai W, Wang C. Interaction between trouble sleeping and depression on hypertension in the NHANES 2005-2018. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:481. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12942-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APHA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. (2018) 71:1269–324. doi: 10.1161/hyp.0000000000000066, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Li X, Wang Z, Bancks MP, Carnethon MR, Greenland P, et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among us adults, 1999-2018. JAMA. (2021) 326:704–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.9883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu F, Earp JE, Adami A, Weidauer L, Greene GW. The relationship of physical activity and dietary quality and diabetes prevalence in us adults: findings from NHANES 2011-2018. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3324. doi: 10.3390/nu14163324, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kage P, Simon JC, Treudler R. Atopic dermatitis and psychosocial comorbidities. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2020) 18:93–102. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel KR, Immaneni S, Singam V, Rastogi S, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic dermatitis, depression, and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2019) 80:402–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.063, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parisapogu A, Ojinna BT, Choday S, Kampa P, Ravi N, Sherpa ML, et al. A molecular basis approach of eczema and its link to depression and related neuropsychiatric outcomes: a review. Cureus. (2022) 14:e32639. doi: 10.7759/cureus.32639, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim JJ, Liu MH, Chew FT. Dietary interventions in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive scoping review and analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. (2024) 185:545–89. doi: 10.1159/000535903, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courtney A, Su JC. The psychology of atopic dermatitis. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:1602. doi: 10.3390/jcm13061602, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu L, Hu X, Jin X. Il-4 as a potential biomarker for differentiating major depressive disorder from bipolar depression. Medicine. (2023) 102:e33439. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000033439, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vai B, Mazza MG, Cazzetta S, Calesella F, Aggio V, Lorenzi C, et al. Higher interleukin 13 differentiates patients with a positive history of suicide attempts in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord Rep. (2021) 6:100254. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li XY, Meng L, Shen L, Ji HF. Regulation of gut microbiota by vitamin C, vitamin E and Β-carotene. Food Res Int. (2023) 169:112749. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112749, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elhage KG, Kranyak A, Jin JQ, Haran K, Spencer RK, Smith PL, et al. Mendelian randomization studies in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. (2024) 144:1022–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2023.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: NHANES (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).