Abstract

C(sp3)–Cl bonds are present in numerous biologically active molecules and can also be used as a site for diversification by substitution or cross-coupling reactions. Herein, we report a remote internal site-selective C(sp3)–H bond chlorination of alkenes through sequential alkene isomerization and hydrochlorination, enabling the synthesis of both benzylic and tertiary chlorides with excellent site-selectivity. This transformation offers exciting possibilities for the late-stage chlorination of derivatives of natural products and pharmaceuticals. We also demonstrate the regioconvergent synthesis of a single alkyl chloride from unrefined mixtures of isomeric alkenes, which can be extracted directly from petrochemical sources.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Synthetic chemistry methodology

C(sp3)–Cl bonds are present in numerous biologically active molecules and can also be used as a site for diversification by substitution or cross-coupling reactions. Here, the authors report a remote internal site-selective C(sp3)–H bond chlorination of alkenes through sequential alkene isomerization and hydrochlorination, enabling the synthesis of both benzylic and tertiary chlorides with excellent site-selectivity.

Introduction

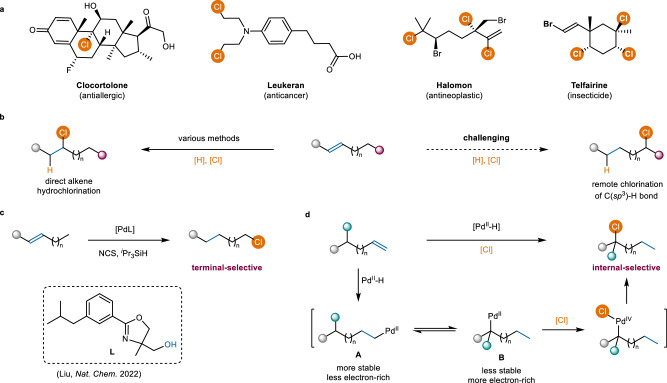

Alkyl chlorides are ubiquitous in nature and are found in nearly every class of biomolecules, ranging from alkaloids to terpenoids to steroids1,2. The chloro group serves as a crucial functional regulator in a variety of fields, including pharmaceuticals, materials, functional molecules, and natural products (Fig. 1a)3–7. Moreover, alkyl chlorides are widely employed as highly versatile synthetic building blocks in organic synthesis8–10. Therefore, significant efforts have been devoted to exploring diverse methodologies for their efficient synthesis11–13.

Fig. 1. Inspiration for internal-selective C(sp3)−H bond chlorination of alkenes.

a, Selected biologically active molecules containing C(sp3)−Cl bonds. b, Hydrochlorination of alkenes. c Previous work: terminal-selective C(sp3)−H bond chlorination of alkenes. d This work: internal-selective C(sp3)−H bond chlorination of alkenes.

Given the abundance and easy accessibility of alkene feedstocks, hydrochlorination of alkenes−including catalytic hydrochlorination14–20 and hydrochlorination using HCl surrogates21–27 or gaseous HCl28–39−represents one of the most straightforward and attractive approaches for synthesizing alkyl chlorides. Typically, hydrogen and chlorine atoms tend to add directly across the C=C bond (Fig. 1b, left). While the remote hydrochlorination of alkenes, which places a hydrogen on the alkene and a chlorine group distal to the alkene, offers promising opportunities for site-selectively chlorinating C(sp3)–H bonds to synthesize structurally diverse alkyl chlorides, it still faces formidable challenges and remains largely unexplored (Fig. 1b, right). Recently, Liu and coworkers achieved a remarkable breakthrough in remote migratory hydrochlorination of alkenes, enabling the selective chlorination of terminal C(sp3)–H bonds (Fig. 1c)40. The exceptional chemo- and site-selectivity is achieved through the use of a well-designed pyridine-oxazoline ligand containing a hydroxyl group. This hydroxyl group can form a hydrogen bond with the oxygen atom of N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS), thereby accelerating the oxidation of stable linear alkyl PdII species by NCS to produce primary alkyl chlorides. Herein, in our continuing research interests in alkene hydrofunctionalizations41–43, we report a Pd-catalyzed internally distant C(sp3)–H bond chlorination through migratory hydrochlorination of alkenes (Fig. 1d). Most previous research on Pd-catalyzed chlorination of C(sp3)–H bonds has predominantly used nitrogen-containing functional groups as directing groups, such as sulfoximine44, amide derived from 8-aminoquinoline45–47, and pyridine48,49. Recently, Yu and coworkers advanced this field by developing a Pd(II)-catalyzed β-C(sp3)–H chlorination of carboxylic acids, where the carboxyl group serves as the directing group50.

Despite significant progress in the transition-metal-catalyzed internal C(sp3)–H bond functionalizations of alkenes through chain walking, achieving internal C(sp3)–H bond chlorination remains an elusive goal51–58. One major challenge is the difficulty of forming C−Cl bonds via thermodynamically unfavorable reductive elimination from organometallic complexes, as the reverse process, oxidative addition, is more facile. This difficulty is further exacerbated when thermodynamically stable styrene derivatives can be formed through competitive β-hydrogen elimination59–61. Inspired by the C(sp3)–H bond functionalizations of alkenes via high-valent palladium intermediates62–64, we speculated that this challenging internal site-selective chlorination could be addressed by using appropriate oxidants and ancillary ligands. Iterative hydropalladation and β-H elimination of an alkene can generate either a linear alkyl PdII species A or a branched alkyl PdII species B (Fig. 1d). Generally, the linear alkyl PdII species A is more stable but less electron-rich compared to the branched alkyl PdII species B40. Precedent literatures have demonstrated that chlorination of the branched alkyl PdII species B, which has a more electron-rich palladium center, is kinetically more favorable than that of the linear alkyl PdII species A when exposed to relatively less reactive electrophilic chlorinating reagents, such as CuCl265,66. Building on this, we hypothesized that employing appropriate electrophilic chlorinating reagents would predominantly oxidize branched alkyl PdII species B, leading to internal site-selective C(sp3)–H bond chlorination.

Results and discussion

Reaction development

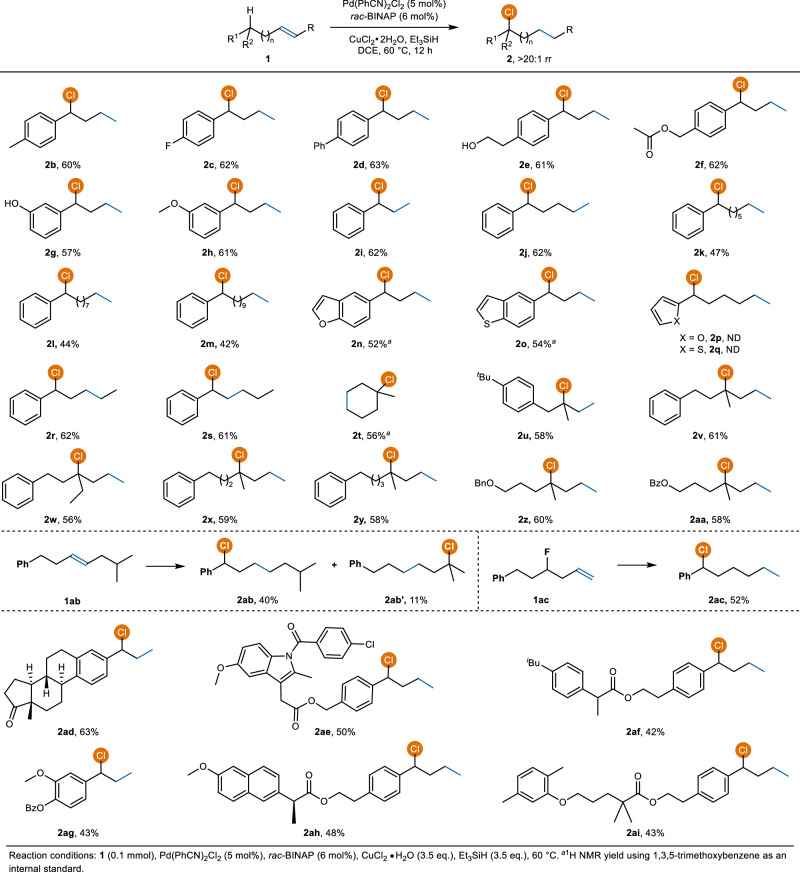

To investigate our hypothesis, we initiated this study with the remote chlorination of 4-phenyl-1-butene 1a (Fig. 2). After carefully evaluating palladium precatalysts, ligands, electrophilic chlorinating reagents, hydride sources, and solvents, we found that this reaction performed well using a combination of Pd(PhCN)2Cl2 and rac-BINAP as the catalyst, CuCl2∙2H2O as the oxidant and chloride source, and Et3SiH as a hydride source (entry 1), providing the desired benzylic chloride 2a with 65% yield and excellent internal site-selectivity (>20:1 rr). Other palladium precatalysts, such as Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2, PdBr2, or Pd(TFA)2, were less efficient, resulting primarily in isomerization and reduction of alkenes (entries 2−4). Chlorination was completely halted even in the presence of an additional 20 mol% CH₃CN under standard conditions. We speculate that CH₃CN, which coordinates more readily with palladium than PhCN, interferes with ligand binding and thus inhibits the chlorination process. Consequently, when Pd(CH3CN)2Cl2 was used instead of Pd(PhCN)2Cl2, the desired chloride 2a was not obtained. Both dppp and dppf led to the desired product but with low yields (entries 5 and 6). Bisphosphine ligands are critical to the reaction, and nitrogen-based ligands and N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands give only a hydrogenation product (see SI for details). Replacement of CuCl2∙2H2O with CuCl2 resulted in a lower yield, possibly because water can activate silane to promote the formation of Pd–H (entry 7)67. No desired chlorinated products were observed when using chlorinating reagents such as N-chlorophthalimide (NCP) and NCS; only isomerization and reduction of alkenes were obtained (entry 8). There are two possible explanations for this result. One is that NCP and NCS, due to their greater steric hindrance, are unable to oxidize the branched alkyl PdII species. The other possibility is that these oxidants may be converted into the corresponding imides in the presence of silane, which could subsequently coordinate with the catalyst and lead to its deactivation. When using the stronger oxidant PhICl2, a mixture of chlorination products at different positions, along with a dichlorination product, was detected by GC-MS (entry 9). This result is likely due to the increased rate of oxidative chlorination facilitated by the stronger chlorinating reagent, which closely matches the rate of migration of the Pd−H species along the carbon chain, leading to the formation of a mixture of isomers. Ph2SiH2 also performed well (entry 10), but (EtO)3SiH gave a poor result with a significant amount of hydrogenation product (entry 11). Another chlorine-containing solvent, such as DCM, led to diminished yields (entry 12). Finally, a control experiment demonstrated the essential role of a palladium catalyst, as no hydrochlorination product was formed when using only CuCl2∙2H2O and silane (entry 13).

Fig. 2.

Reaction optimization.

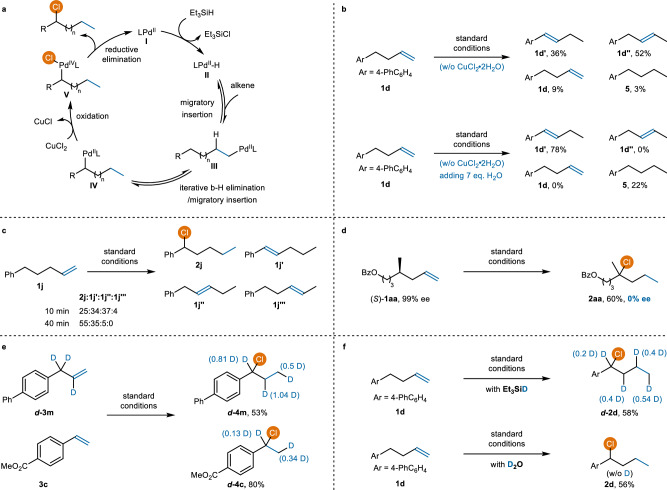

Scope of remote internal C(sp3)–H bond chlorination of alkenes

With these optimal conditions, we subsequently investigated the reaction generality. As illustrated in Fig. 3, a variety of aliphatic alkenes could undergo remote migratory hydrochlorination smoothly, providing the corresponding benzylic chlorides with moderate to good yields and excellent site-selectivity (2b−2h, 57−63% yield, >20:1 rr). Isomerization and reduction of alkenes are the primary by-products observed in substrates with moderate yields. The reaction is insensitive to the chain length between the C=C bond and the remote aryl group, ranging from 1 to 10 C-atoms (2i−2m, 42−62% yield). Heteroaromatic rings, such as furan and thiophene, demonstrate compatibility with the reaction (2n and 2o); however, they cannot serve as termination sites for benzylic chlorination (2p and 2q, see SI for other alkene substrates that show no reactivity). Internal alkenes were found to be competent substrates, regardless of the initial position of the C=C bond (2r and 2s, 62 and 61% yield, respectively). Chlorination of the alicyclic substrate 1t delivered the desired product 2t in 56% yield. Interestingly, chlorination of the tertiary C(sp3)–H bond rather than the benzylic C(sp3)–H bond was successfully achieved when using alkenes that feature a tertiary carbon in the chain (2u−2aa, 56−61% yield). A mixture of benzylic chloride (2ab) and tertiary chloride (2ab′) was obtained when chlorinating an alkene with a benzylic C(sp3)–H bond on one side and a tertiary C(sp3)–H bond on the other side. Using an alkene 1ac with an F-substituent in the aliphatic chain, a defluorinated chlorination product 2ac was obtained with a 52% yield. This result suggests that β-F elimination likely occurred, leading to the formation of a Pd–F species. The presence of silane further facilitates the conversion of the Pd–F complex to Pd–H, allowing the chlorination reaction to continue.

Fig. 3.

Remote internal C(sp3)–H bond chlorination of alkenes.

The introduction of C(sp3)–Cl bonds can impart beneficial properties to biologically active molecules, such as altering the electronic properties of nearby functional groups, enhancing their lipophilicity, and preventing metabolic oxidation at the chlorinated locus68,69. Consequently, we expanded our investigation to encompass a diverse array of substrates originating from bioactive molecules, including estrone (2ad), indomethacin (2ae), ibuprofen (2af), eugenol (2ag), naproxen (2ah), and gemfibrozil (2ai), successfully achieving the corresponding chlorides with excellent site-selectivities (>20:1 rr) and moderate to good yields (42−63% yield). Hydroxyl, ester, amide, and carbonyl groups are well tolerated in our reactions.

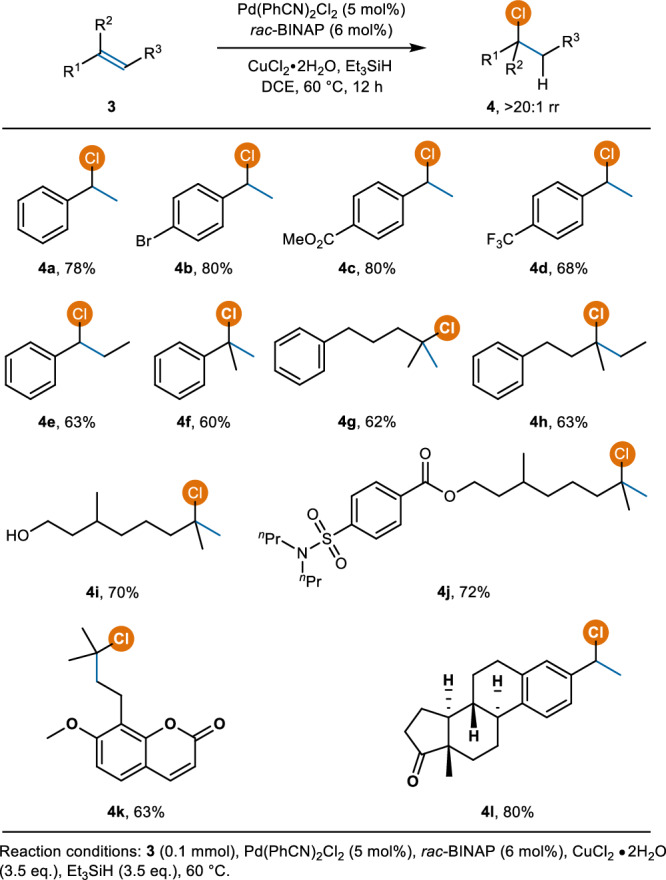

Scope of direct hydrochlorination of alkenes

Despite the development of several approaches for the catalytic hydrochlorination of alkenes, the efficient chlorination of styrene derivatives remains a challenge due to their easy oligomerization14–20. In this context, the hydrochlorination of styrenes under optimized conditions was also investigated (Fig. 4). To our delight, the hydrochlorination of diverse styrenes bearing different substituents on the phenyl ring afforded the benzylic chlorides exclusively (4a−4f, 60−80% yield). Electron-rich styrenes are highly prone to oligomerization under these conditions, and no hydrochlorination products were obtained. Poly-substituted terminal and internal alkenes were also competent substrates and were transformed into the corresponding chlorides in good yields (4g−4j, 62−72% yield). Hydrochlorination of osthol and estrone derivatives worked well, yielding the desired chlorination products in 63% and 80% yields (4k and 4l), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Hydrochlorination of styrenes and poly-substituted alkenes.

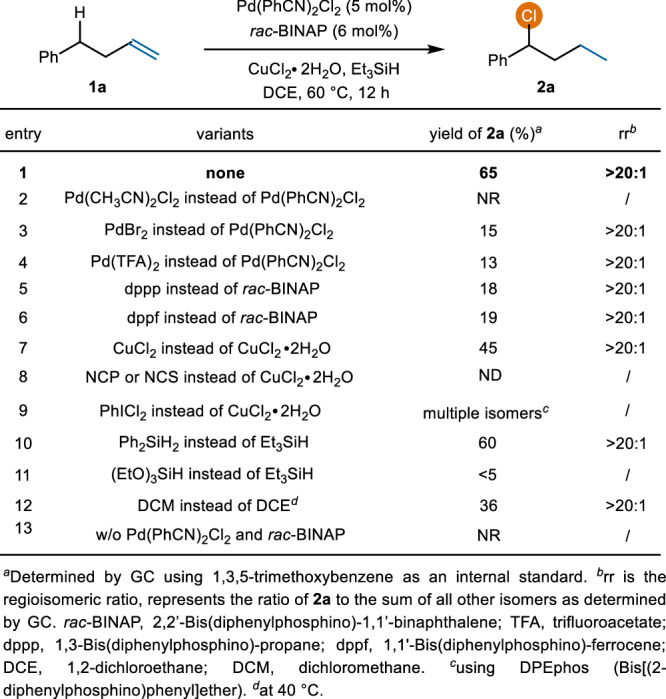

Mechanism investigation

Based on literature reports on remote internal hydrofunctionalization of alkenes and our own investigations, we propose the mechanism shown in Fig. 5a40,65,66,70,71,72–74. The catalytic cycle is initiated by the formation of a Pd–H complex II from LPdII and silane. A series of iterative β-H elimination and migratory insertion processes ultimately provides benzyl or tertiary palladium intermediate IV. In line with Sanford’s arylhalogenation of alkenes65,66, we propose oxidizing the PdII-alkyl species IV with CuCl2∙2H2O to generate a high oxidation state PdIV-intermediate V. Reductive elimination of the intermediate V provides the desired chlorination products. Oxidative chlorination of intermediate IV is more favorable than that of intermediate III, allowing for internal C(sp3)–H bond chlorination.

Fig. 5. Mechanistic studies.

a Proposed mechanism. b Alkene isomerization in the absence of CuCl2∙2H2O or CuCl2. c Reaction monitor. d Hydrochlorination of stereocenter-containing alkene. e Crossover experiment. f Deuterium-labeling experiments.

To gain insights into this internal migratory hydrochlorination, a series of mechanistic experiments were performed. When we subjected alkene 1 d to the standard reaction conditions in the absence of CuCl2∙2H2O, a mixture of alkenes resulting from alkene isomerization was observed (Fig. 5b, top). We also performed the chlorination reaction in the absence of CuCl2 but with 7 eq. of H2O, and observed that the styrenyl derivatives 1 d′ emerged as the major product (Fig. 5b, bottom). These results suggest that alkene isomerization is independent of the presence of CuCl2∙2H2O and indicate that water facilitates the isomerization process by activating the silane67. Furthermore, a mixture of alkenes was obtained when the reaction was run to partial conversion (Fig. 5c), suggesting that alkene isomerization proceeds through rapid dissociation and reassociation of the Pd−H species during the chain-walking process. To further support this rapid dissociation and reassociation proposal, the chlorination of alkene (S)-1aa, which contains a pre-existing stereocenter in the chain, was studied (Fig. 5d). The observation of the racemization is consistent with the dissociated chain-walking mechanism75. Moreover, a crossover experiment was conducted using a mixture of deuterated d−3m and undeuterated 3c. The detection of deuterium in the product d−4c provides additional evidence for the dissociation of the Pd–H species from the alkene (Fig. 5e). Additionally, an isotopic labeling experiment was performed using deuterated silane. Deuterium was observed at all methylenes, suggesting that migration of Pd–H species along the carbon chain of the alkenes indeed occurred (Fig. 5f, top). No deuterium incorporation into the desired product was observed when D2O was used, indicating that the silane is the sole hydrogen source (Fig. 5f, bottom).

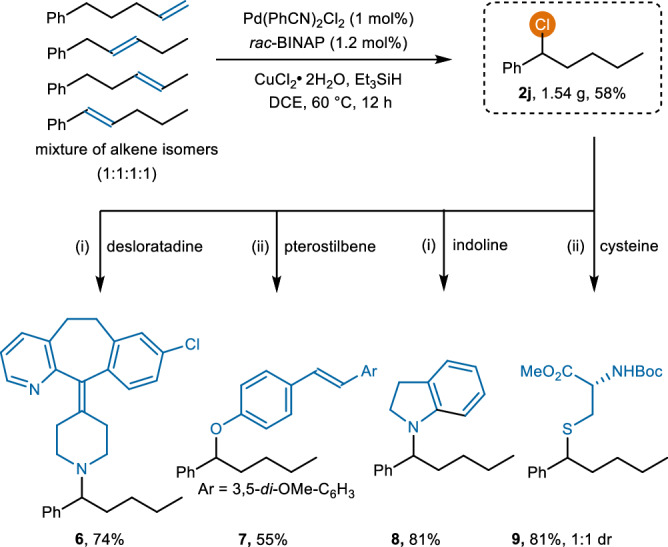

Transformations

Since isomeric mixtures of alkenes can be extracted directly from petrochemical sources and are widely available on an enormous scale as industrial feedstocks, their use in regioconvergent reactions is of considerable interest. Our method enables the remote internal chlorination of alkene isomer mixtures with a catalyst loading as low as 1 mol%, yielding a single benzylic chlorination product 2j on a gram scale (1.54 g, 58% yield, Fig. 6). Alkyl chlorides serve as useful synthons for further transformations, providing various valuable organic compounds. Chlorination product 2j could react with bioactive pharmaceuticals and natural products, such as desloratadine, pterostilbene, indoline, and cysteine, to yield their derivatives.

Fig. 6. Regioconvergent hydrochlorination and its applications.

(i) KI (2.5 eq.), K2CO3 (2.5 eq.), MeCN, 80 °C, 24 h. (ii) KI (2.5 eq.), K2CO3 (2.5 eq.), DMF, 80 °C, 24 h.

Hydrochlorination represents an attractive method for transforming feedstock alkenes into valuable chlorinated bioactive molecules and building blocks. By combining Pd-catalysis with the electrophilic chlorinating agent CuCl2∙2H2O, we successfully achieved a remote internal site-selective C(sp3)–H bond chlorination of alkenes via remote migratory hydrochlorination, enabling the synthesis of both benzylic and tertiary chlorides with excellent site-selectivities. This transformation proceeds under mild conditions, making it practical for late-stage chlorination of bioactive molecules and unrefined mixtures of isomeric alkenes. Ongoing investigations in our laboratory involve exploring other electrophiles of significant synthetic utility, and results will be reported in due course.

Methods

General procedure for hydrochlorination of alkenes

In an N2-filled glovebox, Pd(PhCN)2Cl2 (1.9 mg, 0.005 mmol), rac-BINAP (3.8 mg, 0.006 mmol), and DCE (0.5 mL) were added sequentially to a 1-dram vial. The resulting mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 15 min. Then Et3SiH (41.0 mg, 0.35 mmol), olefin (0.10 mmol), and CuCl2∙2H2O (59.0 mg, 0.35 mmol) were added sequentially to the reaction. The reaction mixture was stirred at 60 oC for 12 h. After this time, the reaction was concentrated and purified by flash silica gel chromatography to give the pure product.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No.2222024), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos.22201018 and 22371016), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2021YFA1401200) for funding. We thank the Analysis & Testing Center of the Beijing Institute of Technology.

Author contributions

Y.-X.W. and Z.W. performed the experiments and collected and analyzed the data. X.-H.Y. directed the project and wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All other data were available from the corresponding author upon request. For experimental details and procedures, spectra for all unknown compounds, see supplementary files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54896-6.

References

- 1.Gribble, G. W. Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds-A Comprehensive Update (Springer, 2010).

- 2.Gribble, G. W. Natural organohalogens: a new frontier for medicinal agents? J. Chem. Educ.81, 1441–1449 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng, J. & Zhan, J. Chlorinated natural products and related halogenases. Isr. J. Chem.59, 387–402 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang, M. L. & Bao, Z. Halogenated materials as organic semiconductors. Chem. Mater.23, 446–455 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernmandes, M. Z. et al. Halogen atoms in the modern medicinal chemistry: hints for the drug design. Curr. Drug Targets11, 303–314 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiodi, D. & Ishihara, Y. “Magic chloro”: profound effects of the chlorine atom in drug discovery. J. Med. Chem.66, 5305–5331 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auffinger, P., Hays, F. A., Westhof, E. & Ho, P. S. Halogen bonds in biological molecules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA48, 16789–16794 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaumann, E. Science of Synthesis: Houben-Weyl Methods of Molecular Transformations 35: Chlorine, Bromine, and Iodine (Georg Thieme, 2008).

- 9.Rudolph, A. & Lautens, M. Secondary alkyl halides in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.48, 2656–2670 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luh, T.-Y., Leung, M.-K. & Wong, K.-T. Transition metal-catalyzed activation of aliphatic C−X bonds in carbon−carbon bond formation. Chem. Rev.100, 3187–3204 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varenikov, A., Shapiro, E. & Gandelman, M. Decarboxylative halogenation of organic compounds. Chem. Rev.121, 412–484 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal, V. et al. Enzymatic halogenation and dehalogenation reactions: pervasive and mechanistically diverse. Chem. Rev.117, 5619–5674 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrone, D. A., Ye, J. & Lautens, M. Modern transition-metal-catalyzed carbon–halogen bond formation. Chem. Rev.116, 8003–8104 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shibutani, S., Nagao, K. & Ohmiya, H. A dual cobalt and photoredox catalysis for hydrohalogenation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 4375–4379 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, J., Sun, X., van der Worp, B. A. & Ritter, T. Anti-Markovnikov hydrochlorination and hydronitrooxylation of α-olefins via visible-light photocatalysis. Nat. Catal.6, 196–203 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie, K. & Oestreich, M. Decarbonylative transfer hydrochlorination of alkenes and alkynes Based on a B(C6F5)3-initiated grob fragmentation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.61, e202203692 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilger, D. J., Grandjean, J. M., Lammert, T. R. & Nicewicz, D. A. The direct anti-Markovnikov addition of mineral acids to styrenes. Nat. Chem.6, 720–726 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaspar, B. & Carreira, E. M. Catalytic hydrochlorination of unactivated olefins with para-toluenesulfonyl chloride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.47, 5758–5760 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podhajsky, S. M. & Sigman, M. S. Coupling Pd-catalyzed alcohol oxidation to olefin functionalization: hydrohalogenation/hydroalkoxylation of styrenes. Organometallics26, 5680–5686 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alper, H. et al. Synthesis of carbonyl-olefin complexes of platinum(II), PtX2(CO)(olefin), and the catalytic hydrochlorination of olefins. Organometallics10, 1665–1671 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertrand, X., Paquin, P., Chabaud, L. & Paquin, J. F. Hydrohalogenation of unactivated alkenes using a methanesulfonic acid/halide salt combination. Synthesis54, 1413–1421 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, X. & Herzon, S. B. Cobalt bis(acetylacetonate)–tert-butyl hydroperoxide–triethylsilane: a general reagent combination for the Markovnikov-selective hydrofunctionalization of alkenes by hydrogen atom transfer. Beilstein J. Org. Chem.14, 2259–2265 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schevenels, F. T., Shen, M. & Snyder, S. A. Isolable and readily handled halophosphonium pre-reagents for hydro- and deuteriohalogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.139, 6329–6337 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yadav, V. K. & Babu, K. G. A. Remarkably efficient Markovnikov hydrochlorination of olefins and transformation of nitriles into imidates by use of AcCl and an alcohol. Eur. J. Org. Chem.2005, 452–456 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Mattos, M. C. S. & Sanseverino, A. M. A convenient and simplified preparation of both enantiomers of α-terpinyl chloride. Synth. Commun.30, 1975–1983 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boudjouk, P., Kim, B.-k & Han, B.-H. Trimethylchlorosilane and water. Convenient reagents for the regioselective hydrochlorination of olefins. Synth. Commun.26, 3479–3484 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kropp, P. J. et al. Surface-mediated reactions. 3. Hydrohalogenation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.115, 3071–3079 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivier, A. & Müller, D. S. Hydrochlorination of alkenes with hydrochloric acid. Org. Proc. Res. Dev.28, 305–309 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verschueren, R. H., Voets, L., Saliën, J., Balcaen, T. & De Borggraeve, W. M. Solvent-free hydrohalogenation and deuteriohalogenation by ex situ generation of HX and DX gas. Eur. J. Org. Chem.26, e202300785 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang, S., Hammond, G. B. & Xu, B. Metal-free regioselective hydrochlorination of unactivated alkenes via a combined acid catalytic system. Green. Chem.20, 680–684 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanemura, K. Silica gel-mediated hydrohalogenation of unactivated alkenes using hydrohalogenic acids under organic solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett.59, 4293–4298 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kropp, P. J. et al. Surface-mediated reactions. 1. Hydrohalogenation of alkenes and alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.112, 7433–7434 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tierney, J., Costello, F. & Dalton, D. R. Hydrochlorination of alkenes. 3. Reaction of the gases hydrogen chloride and (E)- and (Z)−2-butene. J. Org. Chem.51, 5191–5196 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landini, D. & Rolla, F. Addition of hydrohalogenic acids to alkenes in aqueous-organic, two-phase systems in the presence of catalytic amounts of onium salts. J. Org. Chem.45, 3527–3529 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker, K. B. & Grob, C. A. Stereoselective cis and trans addition of hydrogen chloride to olefins. Synthesis789, 790 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fahey, R. C. & Mcpherson, C. A. Kinetics and stereochemistry of the hydrochlorination of 1,2-dimethylcyclohexene. J. Am. Chem. Soc.93, 2445–2453 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fahey, R. C. & Monahan, M. W. Stereochemistry of the hydrochlorination of cyclohexene-1,3,3-d3 in acetic acid. Evidence for termolecular anti addition of acids to olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc.92, 2816–2820 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stille, J. K., Sonnenberg, F. M. & Kinstle, T. H. The addition of hydrogen chloride and hydrobromic acid to 2,3-dideuterionorbornene. J. Am. Chem. Soc.88, 4922–4925 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitmore, F. C. & Johnston, F. Secondary isoamyl chloride, 3-chloro-2-methylbutane. J. Am. Chem. Soc.55, 5020–5022 (1933). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, X., Jin, J., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Catalytic remote hydrohalogenation of internal alkenes. Nat. Chem.14, 425–432 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, Q., Wang, Z., Dong, V. M. & Yang, X.-H. Enantioselective hydroalkoxylation of 1,3-dienes via Ni-catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 3909–3914 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slocumb, H. S., Nie, S., Dong, V. M. & Yang, X.-H. Enantioselective selenol-ene using Rh-hydride catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 18246–18250 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiu, A. Y., Slocumb, H. S., Yeung, C. S., Yang, X.-H. & Dong, V. M. Enantioselective addition of pyrazoles to dienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.60, 19660–19664 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rit, R. K., Yadav, M. R., Ghosh, K., Shankar, M. & Sahoo, A. K. Sulfoximine assisted Pd(II)-catalyzed bromination and chlorination of primary β-C (sp3)–H bond. Org. Lett.16, 5258–5261 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Czyz, M. L. et al. Photoexcited Pd(II) auxiliaries enable light-induced control in C(sp3)–H bond functionalisation. Chem. Sci.11, 2455–2463 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xiong, H.-Y., Cahard, D., Pannecoucke, X. & Besset, T. Pd-catalyzed directed chlorination of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds at room temperature. Eur. J. Org. Chem.2016, 3625–3630 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, X., Sun, Y., Sun, T.-Y. & Rao, Y. Auxiliary-assisted palladium-catalyzed halogenation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds at room temperature. Chem. Commun.52, 6423–6426 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li, B., Wang, S.-Q., Liu, B. & Shi, B.-F. Synthesis of oxazolines from amides via palladium-catalyzed functionalization of unactivated C(sp3)−H bond. Org. Lett.17, 1200–1203 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stowers, K. J., Kubota, A. & Sanford, M. S. Nitrate as a redox co-catalyst for the aerobic Pd-catalyzed oxidation of unactivated sp3-C–H bonds. Chem. Sci.3, 3192–3195 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu, L. et al. Enhancing substrate–metal catalyst affinity via hydrogen bonding: Pd(II)-catalyzed β-C(sp3)–H bromination of free carboxylic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 16297–16304 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, Y., He, Y. & Zhu, S. Nickel-catalyzed migratory cross-coupling reactions: new opportunities for selective C–H functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res.56, 3475–349 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodrigalvarez, J., Haut, F. L. & Martin, R. Regiodivergent sp3 C–H functionalization via Ni-catalyzed chain-walking reactions. JACS Au3, 3270–3282 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, Y., He, Y. & Zhu, S. NiH-catalyzed functionalization of remote and proximal olefins: new reactions and innovative strategies. Acc. Chem. Res.55, 3519–3536 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fiorito, D., Scaringi, S. & Mazet, C. Transition metal-catalyzed alkene isomerization as an enabling technology in tandem, sequential and domino processes. Chem. Soc. Rev.50, 1391–1406 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghosh, S., Patel, S. & Chatterjee, I. Chain-walking reactions of transition metals for remote C–H bond functionalization of olefinic substrates. Chem. Commun.57, 11110–11130 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janssen-Müller, D., Sahoo, B., Sun, S.-Z. & Martin, R. Tackling remote sp3 C−H functionalization via Ni-catalyzed “chain-walking” reactions. Isr. J. Chem.60, 195–206 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sommer, H., Juliá-Hernández, F., Martin, R. & Marek, I. Walking metals for remote functionalization. ACS Cent. Sci.4, 153–165 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vasseur, A., Bruffaerts, J. & Marek, I. Remote functionalization through alkene isomerization. Nat. Chem.8, 209–219 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones, D. J., Lautens, M. & McGlacken, G. P. The emergence of Pd-mediated reversible oxidative addition in cross coupling, carbohalogenation and carbonylation reactions. Nat. Catal.2, 843–851 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen, C. & Tong, X. Synthesis of organic halides via palladium(0) catalysis. Org. Chem. Front.1, 439–446 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang, X., Liu, H. & Gu, Z. Carbon–halogen bond formation by the reductive elimination of PdII species. Asian J. Org. Chem.1, 16–24 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yin, G., Mu, X. & Liu, G. Palladium(II)-catalyzed oxidative difunctionalization of alkenes: bond forming at a high-valent palladium cnter. Acc. Chem. Res.49, 2413–2423 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hickman, A. J. & Sanford, M. S. High-valent organometallic copper and palladium in catalysis. Nature484, 177–185 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sehnal, P., Taylor, R. J. K. & Fairlam, J. S. Emergence of palladium(IV) chemistry in snthesis and catalysis. Chem. Rev.110, 824–889 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalyani, D., Satterfield, A. D. & Sanford, M. S. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative arylhalogenation of alkenes: synthetic scope and mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 8419–8427 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kalyani, D. & Sanford, M. S. Oxidatively intercepting heck intermediates: Pd-catalyzed 1,2- and 1,1-arylhalogenation of alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.130, 2150–2151 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garcés, K. et al. Iridium-catalyzed hydrogen production from hydrosilanes and water. ChemCatChem6, 1691–1697 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gál, B., Bucher, C. & Burns, N. Z. Chiral alkyl halides: underexplored motifs in medicine. Mar. Drugs14, 206 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Naumann, K. Influence of chlorine substituents on biological activity of chemicals: a review. Pest Manag. Sci.56, 3–21 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, Y.-C. et al. Umpolung asymmetric 1,5-conjugate addition via palladium hydride catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202215568 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen, Y.-W., Liu, Y., Lu, H.-Y., Lin, G.-Q. & He, Z.-T. Palladium-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective migratory allylic C(sp3)-H functionalization. Nat. Commun.12, 5626–5634 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li, X., Yang, X., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Palladium-catalyzed remote hydro-oxygenation of internal alkenes: an efficient access to primary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 22877–22883 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu, Z. et al. Multi-site programmable functionalization of alkenes via controllable alkene isomerization. Nat. Chem.15, 988–997 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang, Y., Liu, J. & He, Z. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrofunctionalizations of conjugated dienes. Chin. J. Org. Chem.43, 2614–2627 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kochi, T., Kanno, S. & Kakiuchi, F. Nondissociative chain walking as a strategy in catalytic organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett.60, 150938 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All other data were available from the corresponding author upon request. For experimental details and procedures, spectra for all unknown compounds, see supplementary files.