Abstract

To investigate the safety, efficacy and risk factors for complications of stenting with optional coiling versus coiling alone for acutely ruptured cerebral aneurysms (ARCAs) using different antiplatelet schemes, 2021 patients were prospectively enrolled into the stenting group (n = 967) and the coiling group (n = 1054). Four different antiplatelet regimens were used. The clinical and treatment data were analyzed and compared. In the stenting group, the common antiplatelet regimen was applied in 259 patients (26.8%), loading regimen in 210 (21.7%), intravenous tirofiban regimen in 240 (24.8%), and premedication free regimen in 258 (26.7%). The aneurysm occlusion degrees in the coiling vs. stenting group were not significantly (P > 0.05) different after treatment. Complications occurred in 168 (15.94%) and 171 (17.68%) patients in the coiling and the stenting group, respectively. Fifteen (1.55%) patients experienced stent-related ischemic complications. The only significant (P < 0.05) independent protective factor for complete occlusion was stent-assisted coiling in the stenting group but aneurysm daughter sac in the coiling group. Significant (P < 0.05) independent risk factors for poor mRS (3–6) were posterior circulation aneurysms and neurological bleeding complications in the stenting group and neurological complications in the coiling group. In the stenting group, the only independent risk factor was parent artery stenosis for neurological complications, Raymond grade III for neurological ischemic complications, and the ice cream technique for total complications in the stenting group. In conclusion, different antiplatelet schemes can be safely and efficiently used for intracranial stenting with optional coiling as compared with coiling alone for ARCAs.

Keywords: Different antiplatelet regimens, Acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms, Stenting, Coiling, Complications

Subject terms: Diseases, Medical research, Neurology

Introduction

Endovascular embolization has become the primary approach of treatment for intracranial aneurysms, especially after the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial has proven that endovascular management of ruptured cerebral aneurysms is a safe, effective, and sometimes preferable choice of treatment1,2. However, not all intracranial aneurysms can be safely treated with coiling alone because of the wide neck in some aneurysms. Application of intracranial stents has greatly expanded the indications of endovascular treatment to large and wide-necked cerebral aneurysms, with the stent not only providing a mechanical barrier to prevent coil protrusion but also altering the hemodynamic stresses in both the parent artery and aneurysm to facilitate aneurysm thrombosis and healing3–7. Compared with coil embolization alone, intracranial stents can facilitate adequate aneurysm coiling, increase packing density, and improve long-term outcomes of unruptured, large, wide-necked cerebral aneurysms without significantly elevating the risk of procedural complications7.

Nonetheless, controversies exist regarding the periprocedural safety of stent application for acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms, and increased incidences of hemorrhagic and ischemic complications have been reported in the use of stent-assisted coiling (SAC) compared with coiling alone for acutely-ruptured aneurysms even though great heterogeneity exists in different studies7–9. Nonetheless, the use of SAC did not increase the risk of periprocedural complications for selected ruptured cerebral aneurysms in some studies10,11. These differences may be caused by different antiplatelet regimes, experiences and skills of the operator, types of stents, and criteria of patient’s enrollment. Antiplatelet therapy, even if used for a short period of time, may theoretically predispose patients with acutely-ruptured aneurysms to additional bleeding complications, which may not be tolerated by patients with an already decreased hemorrhagic and neurological reserve. Moreover, differences in the agent, dose and timing of antiplatelet therapy may contribute to additional periprodedural complications in SAC of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms because of no consensus on these aspects among different neuroendovascular physicians. Thus, more stringent prospective studies involving multicenters are necessary to prove the safety and efficacy of different antiplatelet regimes for intracranial stenting with optional coiling for the treatment of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms, and these studies are hypothesized to be effective in these aspects. The purpose of this study was to prospectively investigate the safety and efficacy of different antiplatelet regimes for intracranial stenting with optional coiling in comparison with coiling without stent assistance for acutely ruptured saccular aneurysms.

Materials and methods

Overview

This study was a post hoc analysis using data from an investigator-initiated, prospective, multicenter, open-label, controlled clinical trial (Registration number NCT03153865) that was performed for a different purpose. This multicenter clinical trial had four sections, including the establishment and evaluation of the standardized treatment model for ruptured intracranial aneurysms, the natural and intervention outcome of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, the rupture risk prediction model of unruptured aneurysms, and the standardized antithrombotic therapy for unruptured intracranial aneurysms combined with ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. This study was a subanalysis of the first section for the treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms conducted between July 2016 and April 2020 after approval by the ethics committees of all participating centers. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, and all participating subjects or their legal representatives had signed the informed consent to participate. All methods were conducted in accordance to the relevant guidelines and regulations. The whole trial was designed and supervised by a steering committee of independent academic researchers, and an independent committee monitored the data and study outcomes including the procedure-associated complications, severe adverse events and suggested adjustment of the study outcomes or discontinuation of patient enrollment. All imaging data were evaluated in a blind manner by an imaging research center, and a professional independent statistician performed the analysis.

The clinical trial was funded by the Chinese National Ministry of Science and Technology without involvement in the trial’s design or investigation. No industries had been involved in the trial. The trial sites were certified medical centers in China, with more than 1000 patients with unruputred or acutely-ruptured intracranial aneurysms being treated in each of the medical center. The principle of the Declaration of Helsinki12 had been closely observed in the whole trial. The first author wrote the draft of the manuscript, and all authors had critically reviewed the manuscript. The completeness and accuracy of all data as well as the fidelity of the trial to the protocol had been guaranteed by all authors.

Subjects

The inclusion criteria were patients with acutely ruptured, saccular cerebral aneurysms that were acutely treated with either coiling without a stent for assistance (cohort 1 or the coiling group: coiling alone, balloon coiling, or Comaneci-assisted coiling) or with intracranial stenting (cohort 2 or the stenting group: stent coiling, stenting only, flow diverters, and covered stents). The exclusion criteria were patients with mycotic and traumatic aneurysms, extradural aneurysms, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) with unknown reasons, or malignant cerebral tumors. Acutely ruptured aneurysms were defined as aneurysms which were ruptured within three days before endovascular treatment. The patients were not involved in the study design. The work has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria13.

Antiplatelet regimes

Four currently-available regimes of antiplatelet therapy were used in patients treated with stent or flow diverter placement across the medical centers, including the common regime with the clopidogrel (75 mg/d) and aspirin (100 mg/d) being administered at least three days before the endovascular procedure, the loading regime with 300 mg of clopidogrel and 300 mg of aspirin administered orally or through a nasogastric tube at least 4 h before embolization, the intravenous tirofiban regime, and the premedication free regime. In the intravenous tirofiban regime, patients received a 0.4 µg/kg/min loading dose of tirofiban for 30 min before stenting followed by a 0.10 µg/kg/min maintenance infusion during embolization, and a loading dose of clopidogrel and aspirin (300 mg each) was administered after the tirofiban maintenance infusion. In the premedication free regime, no antiplatelet premedication was prescribed prior to the endovascular procedure, whereas after the endovascular procedure, all patients with stenting received daily doses of 75 mg of clopidogrel for 6 months and 100 mg of aspirin indefinitely. The standard of care was to treat the cerebral aneurysms within 24 h after rupture so as to prevent possible re-rupture before treatment.

Endovascular procedures

The endovascular procedure was performed through the femoral approach under general anesthesia after pre-embolization angiography confirmed the presence of ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Systematic heparinization was conducted after femoral sheath placement with an intravenous heparin bolus of 70–100 U/kg given to all patients followed by continuous infusion of heparin to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) of 2.5 to 3 times to their baseline ACT during the procedure. Three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography was performed to assess the morphology and size of the aneurysm (neck and dome) and parent artery for selection of appropriate coils, stents and flow diverters. Coiling alone was performed until dense packing in narrow-necked aneurysms after a microcatheter was sent into the aneurysm dome. For wide-neck aneurysms (neck > 4 mm and/or dome/neck ratio < 2), an intracranial stent (Enterprise stent, Codman Neurovascular, Raynham, MA, USA; Neuroform stent, Stryker, Stryker, Natick, MA, USA; Solitaire stent, ev3, Plymouth, MN, USA; LVIS stent, Microvention-Terumo, Tustin, CA, USA; LEO, BALT, Montmorency, France; Willis covered stent, Microport, Shanghai, China; Pipeline embolization device, Medtronic, Irvine, CA, USA; Tubridge flow diverter, MicroPort, Shanghai, China) was implanted to cover the aneurysm neck with or without coiling. The type of stent was selected on a case-by-case basis according to the aneurysm size and morphology, size of the parent artery, and specific clinical situations, with the stent or flow diverter slightly bigger than the parent artery diameter and long enough to cover the aneurysm neck. After stent deployment, cerebral angiography was performed to check the location and wall apposition of the stent. In case of poor stent apposition against the arterial wall, a microcatheter or a micro-guidewire was used to massage the inner wall of the stent and make the stent apposite well on the arterial wall. For deployment of a stent inside the ICA siphon, the same operation was performed to make the stent apposite against the siphon wall even though the stent is not specifically designed for the ICA siphon. In case of flow diverter deployment, coil embolization was conducted in patients with irregular, symptomatic (mass effect), large or giant cerebral aneurysms or those with a daughter dome to accelerate fast thrombosis and prevent possible rerupture of the aneurysm. In coiling, a micro-catheter was jailed between the stent or flow diverter and the parent arterial wall in all cases for coil insertion into the aneurysm cavity. Dense packing was achieved for SAC while loose packing was conducted for flow diverter deployment because of the dense mesh of the flow diverters. Heparinization was reversed at the end of the emoblization.

Complication and outcome evaluation

Procedural thromboembolic complications were defined as luminal filling defect, stagnation of contrast filling in an artery, non-display of a distal artery, new neurological deficit / finding on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (even if a complication was not visualized in the case). Hemorrhagic complications occurred when a device was visualized to locate outside the aneurysm lumen with concurrent extravasation of contrast agent, increased hemorrhage on control CT imaging, or rebleeding from the treated aneurysm. Postprocedural cerebral bleeding and infarction were assessed with cerebral CT and/or MRI. The neurological and functional status was evaluated with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score in each patient at discharge. Good outcomes were defined as a mRS score 0–2 while poor outcomes as an mRS score 3–6.

The primary outcome was the neurological and functional status (mRS) at discharge and the risk factors. The secondary outcome was the periprocedural complications and risk factors. The outcomes were assessed in a blind manner by two physicians with over 10-year experience in endovascular treatment of cerebrovascular diseases, and if disagreement arose, a third physician was involved to make a consensus.

Parameters evaluated

Patient’s age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking status, alcohol abuse, parent artery stenosis before embolization, Hunt-Hess (HH) grades to evaluate the SAH severity, anterior or posterior circulation, aneurysm size, neck width, aneurysm location, presence of aneurysm daughter sac, thrombi within the aneurysm sac, diameters of proximal and distal parent artery, treatment time and modes, stent type, antiplatelet regimen, occlusion degree immediately after endovascular treatment, procedural complications, parent artery flow affected after embolization, and clinical outcomes at discharge. Aneurysm occlusion degree immediately after endovascular embolization was assessed with the Raymond-Roy (RR) grades: grade I for complete aneurysm occlusion, grade II for neck remnant, and grade III for aneurysm sac remnant14. If no significant difference (P > 0.05) was detected in the RR grade at the end of treatment between the stenting and coiling groups, the stenting embolization mode was considered as efficacious as the coiling embolization mode. (The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in eSAP 1, and the study project of China National Key R&D Program is available in eSAP 2).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation and tested with the student t-test if in the normal distribution. For continuous variables of non-normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for the test between groups. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentages and tested with the Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test. Univariable logistic regression analysis was performed for risk factors of complications, and factors with the P < 0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis for independent risk factors. Missing data were imputed with the linear regression method, relevant prognostic factors, and outcomes from all relevant information. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding patients whose data were missing. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline data and antiplatelet regimen

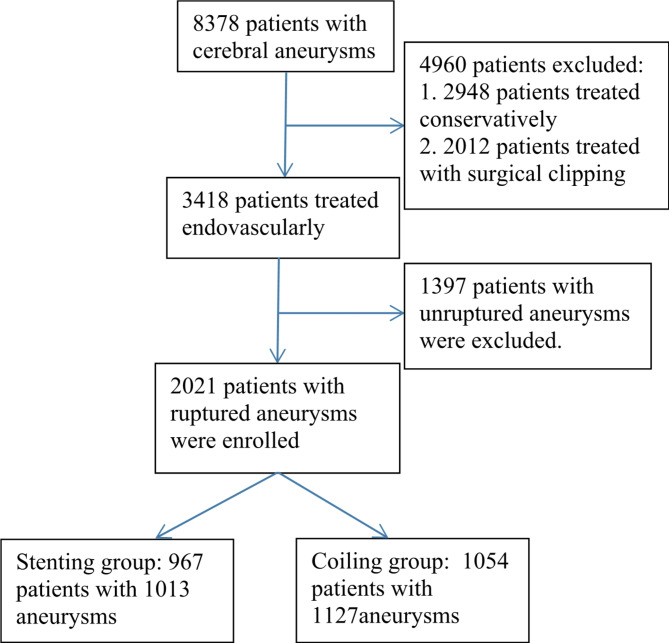

In total, 2021 patients with 2158 ruptured aneurysms were enrolled, including 758 males (37.5%) and 1263 females (62.5%) with a median age of 56.3 years (range 16–87 years) (Fig. 1). The stenting group (cohort 2) enrolled 967 patients harboring 1013 aneurysms, and the coiling group (cohort 1) consisted of 1054 patients with 1127 aneurysms (Table 1). Before endovascular treatment, antivasospasm drugs were administered, including Nimodipine (oral application at 30 mg four times daily) in 346 (49.43% or 346/700) patients, and Fasudil (35 mg for intravenous dripping three times daily) in 33 (4.71% or 33/700) in the stenting group.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment.

Table 1.

Baseline data of the patients (n, % and mean ± SD).

| Variables | Coiling only | Stent or flow diverter placement | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1054 (100) | 967 (100) | |

| Female | 638 (60.53) | 625 (64.63) | 0.39 |

| Mean Age (y) | 56.54 ± 11.78 (12–87) | 56.08 ± 11.19 (14–85) | 0.63 |

| Hypertension | 410 (38.90) | 355 (36.71) | 0.45 |

| Diabetes | 37 (3.51) | 27 (2.79) | |

| Smoking | 166 (15.75) | 137 (14.17) | |

| Alcohol abuse | 105 (9.96) | 74 (7.65) | |

| HH grades | 0.43 | ||

| 0 | 5 (0.47) | 16 (1.65) | |

| 1 | 164 (15.56) | 191 (19.75) | |

| 2 | 400 (37.95) | 456 (47.16) | |

| 3 | 199 (18.88) | 191 (19.75) | |

| 4 | 89 (8.44) | 67 (6.93) | |

| 5 | 19 (1.80) | 14 (1.45) | |

| Antiplatelet regimen | 0.0002 | ||

| Common regimen | 12 (1.14) | 259 (26.78) | |

| Loading regimen | 3 (0.28) | 210 (21.72) | |

| Intravenous tirofiban regimen | 12 (1.14) | 240 (24.82) | |

| Premedication-free regimen | 0 | 258 (26.68) | |

| Time of treatment | 0.89 | ||

| < 24 h after SAH | 727 (68.98) | 289 (29.89) | |

| 24–72 h | 327 (31.02) | 678 (70.11) |

SD standard deviation, HH Hunt-Hess grades.

In the stenting group, the common antiplatelet regimen was applied in 259 patients (26.8%), loading regimen in 210 (21.7%), intravenous tirofiban regimen in 240 (24.8%), and premedication free regimen in 258 (26.7%) (Table 1). In the coiling group, 15 (1.4%) patients were originally planned with stent placement and administered the antiplatelet treatment before embolization.

No significant (P > 0.05) differences existed in the baseline data between two groups except for aneurysm neck size which was significantly (P < 0.0001) larger in the stenting than in the coiling group (3.51 ± 1.77 mm vs. 2.78 ± 1.61 mm) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Aneurysm features and treatment (n, %).

| Variables | Coiling only | Stenting | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of aneurysms | 1127 (100) | 1013 (100) | |

| Location of aneurysms | 0.63 | ||

| Anterior cerebral artery | 443 (39.31) | 260 (25.67) | |

| Middle cerebral artery | 126 (11.18) | 89 (8.79) | |

| Internal carotid artery | 426 (37.80) | 524 (51.73) | |

| Vertebral artery | 27 (2.40) | 54 (5.33) | |

| Basilar artery | 25 (2.22) | 47 (4.64) | |

| Posterior cerebral artery | 22 (1.95) | 23 (2.27) | |

| AICA | 8 (0.71) | 0 | |

| PICA | 38 (3.37) | 15 ((1.48) | |

| Superior cerebellar artery | 12 (1.06) | 1 (0.099) | |

| Aneurysm size (mm) | 5.32 ± 3.16 (0.8–51) | 5.44 ± 3.13 (1–30) | 0.28 |

| < 5 mm | 653 (57.94) | 590 (58.24) | |

| 5–10 mm | 436 (38.69) | 359 (35.44) | |

| > 10 mm | 38 (3.37) | 64 (6.32) | |

| Aneurysm neck (mm) | 2.75 ± 1.28 (0.2–15) | 3.51 ± 1.77 (0.5–20) | <0.0001 |

| Presence of daughter aneurysms | 166 (14.73) | 161 (15.89) | |

| Treatment | NA | ||

| Coiling only | 1053 (93.43) | NA | |

| Balloon assistant coiling | 39 (3.46) | NA | |

| Patent artery occlusion | 9 (0.80) | NA | |

| Double microcathters | 26 (2.31) | NA | |

| SAC | NA | 939 (92.69) | |

| Stent only | NA | 68 (6.71) | |

| Covered stent | NA | 6 (0.59) | |

| Raymond occlusion grade | 0.43 | ||

| I | 1035 (91.84) | 909 (89.73) | |

| II | 72 (6.39) | 36 (3.55) | |

| III | 20 (1.78) | 68 (6.71) | |

| mRS at discharge | 0.11 | ||

| 0–2 | 921 (83.38) | 840 (86.87) | |

| 3–6 | 133 (16.62) | 127 (13.13) |

SAC stent-assisted coiling, PICA posterior inferior cerebellar artery, AICA anterior inferior cerebellar artery, mRS modified Rankin Scale score.

Aneurysm characteristics

Most aneurysms were located at the anterior circulation (Table 2), accounting for 86.2% vs. 88.3% in the stenting vs. the coiling group. The aneurysm size was not significantly (P > 0.05) different in the stenting vs. the coiling group (5.44 ± 3.13 mm vs. 5.32 ± 3.16 mm).

Procedural characteristics

In the coiling group (cohort 1), 1053 aneurysms (93.4% or 1053/1127) were treated with coiling alone, 39 (3.5%) treated with balloon assisted coiling, 9 (0.8%) treated with parent artery occlusion, and 26 (2.3%) managed with double microcatheters (Table 2).

In the stenting group (cohort 2), 939 aneurysms (92.69% or 993/1013) were embolized with SAC including deployment of a stent to cover coil protrusion in six patients, 68 (6.71%) treated with stenting only including 14 Pipeline stents, and six (0.59%) embolized with a Willis covered stent (Table 2). A total of 1019 stents were used, including 552 (54.06%) LVIS stents, 203 (19.88%) Solitaire, 175 (17.14%) Enterprise, 42 (4.11%) Neuroform, 18 (1.76%) LIVS Jr, 14 (1.37%) Pipeline, six (0.59%) Tubridge, six covered (0.59%), and three (0.29%) LEO. Eight (0.83% or 8/967) patients experienced deployment of an additional stent in an overlapping manner to cover a giant aneurysm. The mode of stent deployment included half deployment in 540 (53.31%) patients, deployment after coiling in 318 (31.39%), stenting only in 68 (6.71%), deployment before coiling through the stent in 53 (5.23%), ice cream technique in 26 (2.57%), Y configuration in two (0.20%), and covered stent in six (0.59%).

Angiographic outcome

Immediately after embolization (Table 2), the aneurysm occlusion degrees were Raymond-Roy grade I in 1035 (91.84%) aneurysms, II in 72 (6.39%), and III in 20 (1.78%) in the coiling group, which were not significantly (P = 0.43) different from those in the stenting group [grade I in 909 (89.73%) aneurysms, II in 36 (3.55%), and grade III in 68 (6.71%)].

Clinical outcomes

Periprocedural complications

Complications occurred in 168 (15.94%) and 171 (17.68%) patients in the coiling alone and the stenting group, respectively, however, no significant (P > 0.05) differences existed in the rate of total (15.94% vs. 17.68%, P = 0.55), neurological (5.98% vs. 8.38%, P = 0.31), hemorrhagic (1.04% vs. 1.96%, P = 0.16), ischemic (2.75% vs. 4.03%, P = 0.61), hydrocephalus (2.18% vs. 2.38%, P = 0.61), and other (9.96% vs. 9.31%, P = 0.40) complications in the coiling vs. stenting group even though the rates of neurological complications were higher in the stenting group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Complications in two groups (n, %).

| Variables | Coiling only (1054) | Stenting (967) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total complications | 168 (15.94) | 171(17.68) | 0.55 |

| Neurological complications | 63 (5.98) | 81 (8.38) | 0.31 |

| Hemorrhagic complications | 11 (1.04) | 19 (1.96) | 0.16 |

| Aneurysmal hemorrhage | 10 (0.95) | 12 (1.24) | |

| Vascular injury | 0 | 1 (0.10) | |

| Intraparenchymal hemorrhage | 1 (0.095) | 6 (0.62) | |

| Ischemic complications | 29 (2.75) | 39 (4.03) | 0.61 |

| Coil escape or protrusion | 4 (0.38) | 5 (0.52) | |

| Stent-related | 0 | 15 (1.55) | |

| Vasospasm | 22 (2.09) | 17 (1.76) | |

| Vascular injury | 3 (0.28) | 2 (0.21) | |

| Hydrocephalus | 23 (2.18) | 23 (2.38) | |

| Other complications | 105 (9.96) | 90 (9.31) | 0.40 |

| Groin hematoma | 10 (0.95) | 14 (1.45) | |

| Lower limb venous thrombosis | 5 (0.47) | 4 (0.41) | |

| Digestive tract bleeding | 6 (0.57) | 4 (0.41) | |

| Pneumonia | 83 (7.87) | 68 (7.03) | |

| Femoral arteriovenous fistula | 1 (0.095%) | 0 |

Fifteen (1.55%) patients experienced stent-related ischemic complications, including six (40%) during embolization and nine (60%) after embolization (Table 4), with the parent artery flow being partially affected after embolization in three patients (30%, 40%, and 80% stenosis, respectively). Six of these patients were treated < 24 h after aneurysm rupture, four at 24–72 h, and five at 3d-21 d. The aneurysm neck was significantly (P = 0.01) greater in patients with than those without stent-related ischemic complications (4.67 ± 2.13 mm vs. 3.49 ± 1.69 mm), but the aneurysm size was not significantly (P = 0.21) different between them (6.44 ± 2.29 mm vs. 5.42 ± 2.12 mm).

Table 4.

Data for stent-related ischemic complications (n = 15).

| Variables | Data |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 15 |

| Age (y) | 44–70 (54.53 ± 7.08) |

| Sex (F/M) | 9/6 |

| Height (cm) | 150–175 (162.86 ± 9.00) |

| Weight (kg) | 45–80 (63.11 ± 11.67) |

| BMI | 17.3-28.76 (23.68 ± 3.09) |

| Aneurysm location (n) | ACA: 4, BA: 4, ICA: 4, MCA: 2, VA: 1 |

| Aneurysm size (mm) | 3–20 (6.44 ± 2.29) |

| Neck size (mm) | 1.5–20 (4.67 ± 2.13) |

| Proximal parent artery size (mm) | 2-5.2 (3.21 ± 0.84) |

| Distal parent artery diameter (mm) | 0.22–4.8 (2.61 ± 1.12) |

| mRS scores | 0 in 1, 1 in 3, 2 in 5, 3 in 1, 4 in 2, 5 in 3 |

| No. of aneurysm with a daughter sac | 4 |

| Treatment mode | Stent-coiling |

| Stent types (n, %) | LVIS: 9 (1.63%), Neuroform: 2 (4.76%), Enterprise: 2 (1.14%), Solitaire: 2 (0.99%) |

| Stent deployment modes (n,%) | Stenting only: 1 (1.47%), stent half-deployment: 7 (1.30%), stenting after coiling: 5 (1.57%), Y stenting: 1 (50%) |

| Raymond score (n) | I: 13, II: 1, and III: 1 |

| Parent artery patency (n) | Patent: 12, partially occluded:3 (30%, 40%, and 80%) |

| Time of complications (n) | During embolization: 6, Post embolization: 9 |

| Accompanied complications (n) | Hydrocephalus:1, pneumonia: 1 |

| Time of treatment (n) | < 24 h: 6, 24–72 h: 9 |

| Antiplatelet therapy time (n, %) | Common regimen: 8 (3.09%), loading regimen: 5 (2.38%), and premedication free regimen: 2 (0.78%). |

Data were presented as the mean and standard deviation. BMI body mass index, ACA anterior cerebral artery, BA basilar artery, ICA internal carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery, VA vertebral artery, mRS modified Rankin Scale scores.

mRS at discharge

At discharge, the mRS was 0–2 in 921 (83.38%) patients and 3–6 in 133 (16.62%) in the coiling group with mRS 6 in 23 patients (mortality rate of 2.18% or 23/1054), not significantly (P = 0.11) different from that in the stenting group with 0–2 in 840 (86.87%) patients and 3–6 in 127 (13.13%) with mRS 6 in 24 patients (mortality rate of 2.48% or 24/967) (Table 2).

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses

Aneurysm complete occlusion

The only significant (P < 0.05) independent protective factor for complete occlusion in univariate and multivariate analyses was SAC in the stenting group (Table 5) and an aneurysm daughter sac in the coiling group (Table 6). No risk factors were identified for complete occlusion in either the stenting or coiling group.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses in the stenting group.

| Variables | No. of patients | Univariate analysis | Mutivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| statistics | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Raymond-Roy grade I occlusion | Stent assisted coiling | 944 | 26.46 | < 0.0001 | 15.763(6.241–39.813) | < 0.0001 |

| mRS at discharge | Aneurysm size ≥ 10 mm | 188 | 6.71 | 0.0096 | 1.996(1.138–3.499) | |

| Posterior circulation | 273 | 4.18 | 0.041 | 0.666 (0.454–0.977) | 0.0005 | |

| Parent artery occluded or stenotic | 19 | 12.99 | 0.0003 | 0.164(0.065–0.412) | ||

| Neurological complications | 81 | 131.19 | < 0.0001 | 0.054(0.331 − 0.089) | ||

| Bleeding complications | 19 | 53.33 | < 0.0001 | 0.023(0.007–0.799) | 0.003 | |

| Ischemic complications | 39 | 44.54 | < 0.0001 | 0.091(0.046–0.178) | ||

| Stent-related ischemic complications | 15 | 7.596 | 0.0059 | 0.20(0.070–0.571) | ||

| Thrombolysis for ischemia | 15 | 4.99 | 0.026 | 5.25(1.15–23.94) | ||

| Ischemia occurring during embolization | 12 | 11.15 | 0.0008 | 13.57(2.36–77.95) | ||

| Other complications | 90 | 24.21 | < 0.0001 | 0.283(0.174–0.459) | ||

| Total complications | 171 | 147.52 | < 0.0001 | 0.078(0.052–0.117) | ||

| Neurological complications | Parent artery flow affected after treatment | 19 | 8.937 | 0.0028 | 5.575(2.061–15.082) | |

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 6 | 13.813 | 0.0002 | 26.795(4.832-148.578) | 0.027 | |

| Stent related ischemic complications | Parent artery flow affected after treatment | 19 | 9.723 | 0.002 | 0.065(0.017–0.253) | |

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 6 | 18.309 | < 0.0001 | 0.011(0.002–0.059) | 0.0041 | |

| Neurological ischemic complications | Parent artery flow affected after treatment | 19 | 12.79 | 0.0003 | 10.727(3.646–31.621) | |

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 6 | 12.618 | 0.0004 | 32.029(6.236-164.508) | ||

| Raymond grade III | 22 | 3.889 | 0.049 | 4.444(1.255–15.743) | 0.034 | |

| Other complications | Aneurysm neck ≥ 4 mm | 36 | 3.95 | 0.047 | 1.61(1.011–2.564) | |

| Proximal parent artery diameter < 3.2 mm compared with > 3.2 | 23 | 5.296 | 0.021 | 0.536(0.312–0.920) | ||

| Daughter aneurysm sac | 31 | 16.842 | < 0.0001 | 2.853(1.768–4.604) | ||

| Deployment of a stent vs. multiple stents | 62 | 37.085 | < 0.0001 | 0.096(0.048–0.192) | ||

| Ice cream stenting technique | 17 | 66.37 | < 0.0001 | 55.798(18.217–170.91) | < 0.0001 | |

| Total complications | Daughter aneurysm sac | 161 | 13.58 | 0.0002 | 2.208(1.469–3.319) | |

| Deployment of a stent vs. multiple stents | 859 vs. 38 | 23.772 | < 0.0001 | 0.173(0.089–0.338) | ||

| Ice cream stenting technique | 21 | 47.265 | < 0.0001 | 27.571(9.118–83.362) | 0.000 | |

| Parent artery flow affected after treatment | 19 | 4.244 | 0.039 | 2.702(1.011–7.224) | ||

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 6 | 9.11 | 0.003 | 13.28(2.41–73.14) | ||

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, mRS modified Rankin scale scores, ICA internal carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery.

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses in the coiling group.

| Variables | No. of patients | Univariate analysis | Mutivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| statistics | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Raymond-Roy grade I | Daughter Aneurysm sac | 23 | 7.323 | 0.007 | 2.079 (1.256–3.441) | 0.025 |

| mRS at discharge | Daughter aneurysm sac | 122 | 10.71 | 0.001 | 2.162 (1.386–3.371) | |

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 31 | 11.16 | 0.0008 | 3.781 (1.808-7.90) | ||

| Neurological complications | 63 | 66.52 | < 0.0001 | 9.717 (5.638–16.746) | 0.04 | |

| Ischemic complications | 29 | 32.61 | < 0.0001 | 9.907 (4.47–21.96) | ||

| Hydrocephalus | 23 | 29.39 | < 0.0001 | 11.571 (4.628–28.933) | ||

| Other complications | 105 | 65.11 | < 0.0001 | 6.51 (4.186–10.138) | ||

| Total complications | 168 | 110.12 | < 0.0001 | 8.833 (5.887–13.254) | ||

| Neurological complications | Parent artery flow affected after treatment | 34 | 6.016 | 0.014 | 3.689 (1.471–9.251) | |

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 45 | 8.264 | 0.004 | 3.825 (1.704–8.587) | 0.009 | |

| Treatment by occluding parent artery | 9 | 6.39 | 0.012 | 8.37 (2.04–34.26) | ||

| Lacerum and Cavenous ICA segments | 9 | 7.152 | 0.0075 | 10.5 (2.358–46.749) | 0.017 | |

| Neurological ischemic complications | Treatment by occluding parent artery | 9 | 5.584 | 0.018 | 11.545 (2.291–58.174) | |

| Parent artery flow being affected after treatment | 34 | 6.584 | 0.01 | 5.696 (1.866–17.389) | ||

| Total complications | Daughter aneurysm sac | 166 | 18.945 | < 0.0001 | 2.570 (1.714–3.854) | |

| Aneurysms at MCA M1 segment | 18 | 6.138 | 0.013 | 5.549 (1.536–20.055) | 0.012 | |

| Parent artery stenosis before treatment | 45 | 7.90 | 0.005 | 2.808 (1.438–5.483) | ||

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, mRS modified Rankin scale scores, ICA internal carotid artery, MCA middle cerebral artery.

mRS at discharge

In the stenting group, significantly (P < 0.05) better outcomes (mRS 0–2) were achieved in patients with the aneurysm size ≥ 10 mm, occurrence of ischemic complications during embolization, and treatment of ischemic complications with thrombolysis, but poor outcomes (mRS 3–6) in patients with posterior circulation aneurysms, parent artery stenosis or occlusion, neurological complications, neurological bleeding complications, neurological ischemic complications, stent-related ischemic complications, other non-neurological complications, and total complications (Table 5). Multivariate analysis revealed posterior circulation aneurysms and neurological bleeding complications as significant (P < 0.05) independent risk factors for poor mRS (3–6) at discharge.

In the coiling group (Table 6), univariate analysis revealed significantly (P < 0.05) poor outcomes (mRS 3–6) in patients with a daughter aneurysm sac, combined parent artery stenosis, neurological complications, ischemic complications, hydrocephalus, other complications, and total complications, whereas multivariate analysis revealed neurological complications as the only significant (P < 0.05) independent risk factor for poor outcomes at discharge.

Complications

a. Stenting group

Stent-related hemorrhagic complications occurred in 18 (1.65%) patients (Table 3), including aneurysmal hemorrhage in 12 (1.24%) and intraparenchymal hemorrhage in 6 (0.62%), all in patients treated with stent-assisted embolization using the braided LVIS stent in 11 (1.08 or 11/1019), laser-cut stents (3 Solitarie, 2 Enterprise, and 2 Neuroform) in 7 (0.69% or 7/1019), and flow diverter or covered stent in 0. Stent-related ischemic complications took place in 15 (1.55%) patients (Table 4), including 9 (0.88% or 9/1019) LVIS (braided) stents and 6 (0.59% or 6/1019) laser-cut stents (2 Solitaire, 2 Enterprise, and 2 Neuroform) without involving the flow diverters or covered stents. No significant (P = 0.20) difference was detected in the hemorrhagic and ischemic complications between the braided, laser-cut or flow diverters and covered stents.

Significantly (P < 0.01) more stent-related ischemic complications were present in patients with the parent artery stenosis before embolization and the parent artery flow being affected after embolization, whereas the parent artery stenosis was the only independent risk factor for stent-related ischemic complications (Table 5).

Significantly (P < 0.01) more neurological complications occurred in patients with parent artery stenosis and parent artery flow being affected after embolization, whereas parent artery stenosis was the only independent risk factor for neurological complications. Significantly (P < 0.05) more neurological ischemic complications took place in patients with parent artery flow affected after embolization, parent artery stenosis, and Raymond grade III, with Raymond grade III as the only significant independent risk factor for neurological ischemic complications. Other non-neurological complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in patients with an aneurysm neck ≥ 4 mm, proximal parent artery diameter < 3.2 mm, daughter aneurysm sac, deployment of a single stent, and the ice cream technique, with the ice cream technique as the only significant independent risk factor for other complications.

Total complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in patients with a daughter aneurysm sac, use of the ice cream technique for stenting, parent artery flow affected, and parent artery stenosis, but significantly (P < 0.0001) decreased in patients with deployment of only one stent (Table 5). Multivariate analysis revealed that the ice cream technique for stenting was the only significant (P < 0.05) independent risk factor for total complications.

b. Coiling group

Significantly (P < 0.05) more neurological complications were present in patients with parent artery flow being affected, parent artery stenosis, treatment by occluding the parent artery, and aneurysms located in the Lacerum and Cavenous segments of ICA, whereas parent artery stenosis and aneurysm location in the Lacerum and Cavenous segments of ICA were two significant (P < 0.05) independent risk factors for neurological complications (Table 6). Neurological ischemic complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in patients with parent artery occlusion and parent artery flow being affected, but no significant independent risk factors were found for ischemic complications. Total complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in patients with a daughter aneurysm sac, aneurysms at the MCA M1 segment, and parent artery stenosis before treatment, with aneurysms at the MCA M1 segment as the only significant independent risk factor for total complications.

Discussion

In this study investigating the safety, efficacy and risk factors for complications of stenting with optional coiling versus coiling alone for ARCAs using different antiplatelet schemes, it was found that different antiplatelet schemes can be safely and efficiently used for intracranial stenting with optional coiling as compared with coiling alone in the treatment of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms.

Surgery in the acute phase of aneurysm rupture is dangerous because of the severe conditions and possible surgical complications, and aneurysm rerupture. Nonetheless, to facilitate medications for patients with ruptured cerebral aneurysms and prevent further rupture of the aneurysm, surgical treatment of these patients is necessary in the acute phase of aneurysm rupture. Stent thrombosis is a common complication in the use of intracranial stents for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms and may be associated with stent implantation and hypercoagulable state of the patients in the acute stage of rupture15. Oral administration of antiplatelet agents before embolization of unruptured cerebral aneurysms for preventing thromboembolism is widely accepted. The dosage of 100–300 mg/day for aspirin and 75 mg/day for clopidogrel has been recommended in the literature, administered orally 5–7 days before the coiling procedure16,17. However, if the patient did not follow such a regimen, a loading dose of 300–500 mg of aspirin and 300 mg of clopidogrel could be administered as a viable alternative just before coiling. Nonetheless, whether periprocedural antiplatelet therapy is useful for acutely ruptured aneurysms is unclear. In some studies testing the platelet function after dual antiplatelet therapy in endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms18,19, the adenosine diphosphate (ADP) inhibition rate was associated with subsequent cerebral ischemic events and intracranial or extracranial bleeding events. However, based on the outcome of an international multicenter study20, preprocedural platelet function testing before Pipeline treatment of intracranial aneurysms in patients premedicated with an aspirin and clopidogrel dual antiplatelet therapy regimen may not be necessary to significantly reduce the risk of procedure-related intracranial complications. Nonetheless, development of ethno-oriented DAPT (dual antiplatelet therapy) regimens in the future is necessary to improve the prognosis associated with better inhibition of the platelet in different populations.

Although stenting is able to prevent coil protrusion and alter hemodynamic stresses to promote aneurysm healing, adverse effects may occur more frequently in ruptured aneurysms with likely worse clinical outcomes than those without stenting as reported in a systematic review21. One study even reported a 10 times higher rate of early adverse events in ruptured cerebral aneurysms than that in unruptured ones22. Thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications have been reported to present in 25% of patients with stent deployment for treatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms in comparison with only 4% in case of unruptured aneurysms23. These adverse events may be primarily associated with the dual antiplatelet therapy which is required to prevent thrombosis-induced stent occlusion in ruptured aneurysms. Aneurysm rupture will create a hypercoagulable status, where a stent in SAC will become highly thrombogenic for parent arteries until the stent has become completely endothelialized24. Nonetheless, Edwards et al. demonstrated that preventive antiplatelet therapy could significantly decrease the rate of periprocedural thromboembolic complications without causing major systemic or intracranial hemorrhage for patients with ruptured aneurysms at a high risk of a thromboembolic event25. Ryu et al. concluded that the periprocedural complications of SAC for ruptured cerebral aneurysms could be affected by the approach of antiplatelet administration26. Yet, the optimal antiplatelet medication during the acute stage of aneurysm rupture has to be determined, and insufficient antiplatelet regimen may be the main factor of stent ischemic complications.

In our study, four antiplatelet regimens were used. The first common regimen applied dual antiplatelet therapy at least three days before the embolization procedure, which was also frequently used in the treatment of unruptured aneurysms. The disadvantage of this scheme is that it delays the treatment opportunity of acutely-ruptured aneurysms. Moreover, it does not confirm the effectiveness of the antiplatelet therapy if the thromboelastography-platelet mapping is not measured. The second regimen is an intensive scheme. Because clopidogrel is a precursor drug that needs to be metabolized to form an effective component and some patients may be clopidogrel resistant, this scheme may not achieve sufficient antiplatelet effect. The third one is the intravenous tirofiban regimen, which has been proved to be effective in the antiplatelet therapy for the treatment of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms27–29. The fourth scheme did not use antiplatelet drugs before the endovascular procedure. Choi et al.30 had demonstrated a higher rate of procedural thromboembolism of SAC as compared with coiling alone (25.5% vs. 12.4%, P = 0.01) in using this regimen for acutely-ruptured aneurysms, but without causing a significant (P > 0.05) difference in poor clinical outcomes (mRS ≥ 3) between the treatment approaches (30.9% vs. 22.1%).

In our study, the rates of total (17.68% vs. 15.94%), neurological (8.38% vs. 5.98%), hemorrhagic (1.96% vs. 1.04%), and ischemic (4.03% 2.75%) complication were not significantly different in the stenting vs. coiling alone group even though the relevant complication rate was higher in the stenting group which adopted the antiplatelet therapy. More hemorrhagic and stent-related ischemic complications were present in the stenting group. Intracranial hemorrhage (2-4%) has been reported to associate with SAC or flow diversion for cerebral aneurysms31–34, which was consistent with our study. Though the intraparenchymal hemorrhage rate was not significantly different in the coiling vs. stenting group (0.095% vs. 0.62%), the rate in the stenting group was 6.5 times that in the coiling group. Stent-related ischemic complications occurred in 15 patients (1.55%) in the stenting group, especially in patients with the parent artery stenosis before embolization and the parent artery flow being compromised after embolization, and the parent artery stenosis before embolization was the only independent risk factor for stent-related ischemic complications. These results may suggest that the use of the antiplatelet therapy in the treatment of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms with stents or flow diverters may not significantly increase the hemorrhagic or ischemic complication rate and that the antiplatelet therapy may not be a risk factor for these hemorrhagic or ischemic complications. In SAC for acutely-ruptured aneurysms, the total periprocedural complication rate was reported to range 5.6–20.2%, with the hemorrhagic and ischemic complication rate ranging 3.5-9.1% and 2.1-25.5%, respectively24,30,35, which were consistent with our study.

In the stent-related ischemic complications, the modes of stent deployment were not significantly different even though the mode of Y stenting reached 50% because only two patients received Y-configuration stenting. In the stents used, the Neuroform stent seemed to have a higher stent-related ischemic complication rate (4.76%) compared with the LVIS (1.63%), Enterprise (1.14%), and Solitaire (0.99%) stent. The exact reason for this is unknown but may be related to its open-cell design. The common regimen was the mostly frequently used antiplatelet therapy followed by the loading regimen and premedication free regimen. Nonetheless, the parent artery stenosis before embolization was the only independent risk factor for stent-related ischemic complications. In analyzing factors affecting different complications, the only independent risk factor for neurological, neurological ischemic, and other non-neurological and total complications in the stenting group was the parent artery stenosis before embolization, the Raymond-Roy grade III, and the ice cream technique for stent deployment, respectively.

In the coiling group, the neurological complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased by the parent artery flow being affected after embolization, parent artery stenosis, treatment by occluding the parent artery, and aneurysms located in the Lacerum and Cavernous segments of ICA, with parent artery stenosis and aneurysm location in the Lacerum and Cavernous segments of ICA being two significant (P < 0.05) independent risk factors. Neurological ischemic complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased by occluding the parent artery and parent artery flow being affected after treatment. Total complications were significantly (P < 0.05) increased in patients with a daughter aneurysm sac, aneurysms at the MCA M1 segment, and combined parent artery stenosis, with aneurysms at the MCA M1 segment being the only significant independent risk factor for total complications. These results suggest parent artery stenosis before embolization and parent artery flow being affected including parent artery occlusion for treatment may all affect the neurological and total complications in both groups.

Clinical outcomes at discharge were not significantly (P > 0.05) different between the two groups. In the stenting group, good outcomes were achieved in patients with an aneurysm size ≥ 10 mm, presence of ischemic complications during the embolization procedure and use of thrombolysis for ischemic complications, whereas poor outcomes in patients with posterior circulation aneurysms, parent artery stenosis and neurological complications. However, posterior circulation aneurysms and neurological bleeding complications were significant independent risk factors for poor clinical outcome at discharge. In the coiling group, poor outcomes were present in patients with a daughter aneurysm sac, parent artery stenosis, and complications, with neurological complications as the only significant independent risk factor for poor outcomes. At discharge, favorable outcomes (mRS 0–2) were achieved in 83.38% in the coiling group, which was not significantly different from 86.87% in the stenting group. Favorable outcomes have also been reported in other studies using SAC in the treatment of ruptured aneurysms in the acute stage, ranging from 82.5 to 88.0% 7,24.

The embolization approach using the ice cream technique in the stenting group significantly increased the non-neurological and total complication rate, whereas occluding the parent artery in the coiling group significantly increased the neurological complication rate. These approaches should be carefully weighed before application. The ice cream stenting technique was used when embolizing a bifurcation aneurysm with SAC, where a stent was deployed in the parent artery with the distal stent end located at the aneurysm neck (without entering the aneurysm cavity) before coiling the aneurysm dome through the stent lumen. After embolization, the stent and the coils in the aneurysm dome distal to the stent looked like an ice cream. Currently, the ice cream stenting technique is not used because of the poor embolization effect. Because the parent artery stenosis before treatment and the parent artery flow being compromised after embolization are two factors significantly affected the clinical outcomes at discharge as well as neurological and total complications in both the coiling and stenting groups, careful handling of these conditions is necessary to improve the outcomes and complications.

Aneurysm occlusion degrees immediately after embolization were not significantly different in the coiling versus the stenting group. For complete occlusion, the only significant (P < 0.05) independent protective factor was SAC in the stenting group but aneurysm daughter sac in the coiling group, which suggests that SAC may significantly increase the aneurysm complete occlusion rate. Because an aneurysm daughter sac may increase the risk of aneurysm rupture, dense packing is required to prevent aneurysm rupture at the daughter sac, which may contribute to the increased rate of complete aneurysm occlusion in the coiling group. Thus, the presence of an aneurysm daughter sac was detected to be a protective factor for the complete occlusion rate. The complete aneurysm occlusion rate was Raymond-Roy grade I of 91.84% in the coiling group and 89.73% in the stenting group in our study, which was consistent with the complete aneurysm occlusion rate of 80.6-92.7% reported in studies investigating SAC for ruptured aneurysms in the acute stage7,24.

In the stenting group, aneurysms with a wide neck (> 4 mm or the dome-to-neck ratio < 2) were treated with stent or flow diverter deployment, whereas aneurysms in the coiling group had a narrow neck (< 4 mm or the dome-to-neck ratio > 2). This difference in the aneurysm neck width is well known, and aneurysms with a wide neck has to be treated with SAC or flow diversion because it is very difficult or impossible to treat a wide-necked aneurysm with coiling alone. For acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms, it is relatively safe to use intracranial stents for emergency treatment of these ruptured aneurysms. Because of the microinvasiveness, endovascular treatment with or without use of intracranial stents is recommended in the acute phase of aneurysm rupture. If necessary, thromboelastography is needed to monitor the antiplatelet effect of DAPT for adjusting the DAPT dosage and agents especially for some medical centers with many experiences in this aspect36.

The strengths of our study were the use of a large cohort of patients in the prospective investigation of the safety and efficacy of different antiplatelet regimens in endovascular treatment of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms at multiple medical centers with exploration of risk factors for relevant complications. Some limitations also existed in this study. This study only analyzed aneurysm occlusion degrees immediately after embolization and periprocedural complications, with no analysis of the results at angiographic follow-up. Because our focus was mainly in the complications associated with the use of stents or flow diverters, heterogeneities might also exist in the aneurysm morphology in the coiling versus stenting group, which may also affect the outcomes. Moreover, only Chinese patients were enrolled, and the outcomes should be generalized with caution for other ethnic groups. The time of endovascular treatment was also a limitation because 70% of stent group were treated at the time 24 h after aneurysm rupture and 68% of the coiling group were treated within 24 h. Re-bleeding risk of aneurysmal rupture is high within 24 h, which may potentially affect thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complication. Furthermore, this study used some old data which may affect the generalization of the outcomes. Future prospective, randomized, controlled studies will have to be conducted involving multiple centers and ethnicities and considering all the above issues for better outcomes.

In conclusion, different antiplatelet schemes can be safely and efficiently used for intracranial stenting with optional coiling as compared with coiling alone in the treatment of acutely-ruptured cerebral aneurysms at the acute stage even though more stringent studies may be necessary to prove this finding.

Author contributions

Study design: L.L., T.-X.L., B.-L.G.; Data collection: L.L., Q.-H.H., Q.-J.S., K.-T.C., Q.-Q.Z., L.-F.Z.; Data analysis: L.L., Q.-Hai Huang, Bu-Lang Gao; Supervision: Li Li; Approval: All authors.

Funding

This study was supported by the 13th Fiveyear Plan of China for Research and Development (2016YFC1300702), Henan Province Science and Technology Key Project (182102310658), and Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (222102310208).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Molyneux, A. et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (isat) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised trial. Lancet360, 1267–1274 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molyneux, A. J. et al. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (isat) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet366, 809–817 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao, B., Baharoglu, M. I., Cohen, A. D. & Malek, A. M. Y-stent coiling of basilar bifurcation aneurysms induces a dynamic angular vascular remodeling with alteration of the apical wall shear stress pattern. Neurosurgery72, 617–629 (2013). discussion 628 – 619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao, B., Baharoglu, M. I. & Malek, A. M. Angular remodeling in single stent-assisted coiling displaces and attenuates the flow impingement zone at the neck of intracranial bifurcation aneurysms. Neurosurgery72, 739–748 (2013). discussion 748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao, B. L. et al. Cerebral aneurysms at major arterial bifurcations are associated with the arterial branch forming a smaller angle with the parent artery. Sci. Rep.12, 5106 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao, B. L. et al. Greater hemodynamic stresses initiated the anterior communicating artery aneurysm on the vascular bifurcation apex. J. Clin. Neurosci.96, 25–32 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue, G. et al. Safety and efficacy of stent-assisted coiling for acutely ruptured wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: Comparison of lvis stents with laser-cut stents. Chin. Neurosurg. J.7, 19 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darkwah Oppong, M. et al. Secondary hemorrhagic complications in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: When the impact hits hard. J. Neurosurg. 1–8 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hudson, J. S. et al. Hemorrhage associated with ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients on a regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy: A retrospective analysis. J. Neurosurg.129, 916–921 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chitale, R. et al. Treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: comparison of stenting and balloon remodeling. Neurosurgery72, 953–959 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuo, Q. et al. Safety of coiling with stent placement for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: A contemporary cohort study in a high-volume center after improvement of skills and strategy. J. Neurosurg.131, 435–441 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Medical, A. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA310, 2191–2194 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathew, G. et al. Strocss 2021: Strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. Int. J. Surg.96, 106165 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Won, S. Y. et al. Short- and midterm outcome of ruptured and unruptured intracerebral wide-necked aneurysms with microsurgical treatment. Sci. Rep.11, 4982 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez, P., Lukaszewicz, A. C., Lenck, S., Nizard, R., Drouet, L., & Payen, D. Platelet activation and aggregation after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. BMC Neurol.18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kim, M. S. J. K. et al. Safety and efficacy of antiplatelet response assay and drug adjustment in coil embolization: A propensity score analysis. Neuroradiology58, 1125–1134 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxley, T. J. D. R., Mitchell, P. J., Davis, S. & Yan, B. Antiplatelet resistance and thromboembolic complications in neurointerventional procedures. Front. Neurol.2 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Xu, R. et al. Microbleeds after stent-assisted coil embolization of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Incidence, risk factors and the role of thromboelastography. Curr. Neurovasc Res.17, 502–509 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge, H. et al. Association of thrombelastographic parameters with complications in patients with intracranial aneurysm after stent placement. World Neurosurg.127, e30–e38 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vranic, J. E. et al. The impact of preprocedural platelet function testing on periprocedural complication rates associated with pipeline flow diversion: An international multicenter study. Neurosurgery95, 179–185 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodily, K. D., CJ, Lanzino, G., FiorellaD, J., WhiteP, M. & Kallmes, D. F. Stent-assisted coiling in acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A qualitative, systematic review of the literature. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.32, 1232–1236 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bechan, R. S. S. M., Majoie, C. B., Peluso, J. P., Sluzewski, M. & van Rooij, W. J. Stent-assisted coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms: Complications in acutely ruptured versus unruptured aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.37, 502–507 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalouhi, N. J. P. et al. Stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms: Predictors of complications, recanalization, and outcome in 508 cases. Stroke44, 1348–1353 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muto, M. G. F. et al. Stent-assisted coiling in ruptured cerebral aneurysms: Multi-center experience in acute phase. Radiol. Med.122, 43–52 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards, N. J. J. W., Sanzgiri, A., Corona, J., Dannenbaum, M. & Chen, P. R. Antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of peri-coiling thromboembolism in high-risk patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J. Neurosurg.127, 1326–1332 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryu, C. W. S. P. S., Shin, H. S. & Koh, J. S. Complications in stent-assisted endovascular therapy of ruptured intracranial aneurysms and relevance to antiplatelet administration: A systematic review. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.36, 1682–1688 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, S. C. J., Kang, M., Cha, J. K. & Huh, J. T. Safety and efficacy of intravenous tirofiban as antiplatelet premedication for stent-assisted coiling in acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol.37, 508–514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, Z. L. et al. Intravenous administration of tirofiban versus loading dose of oral clopidogrel for preventing thromboembolism in stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms. Int. J. Stroke. 12, 553–559 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu, Q. S. Q. et al. Prophylactic administration of tirofiban for preventing thromboembolic events in flow diversion treatment of intracranial aneurysms. J. Neurointerv Surg.13, 835–840 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi, H. H. C. Y. et al. Antiplatelet premedication-free stent-assisted coil embolization in acutely ruptured aneurysms. World Neurosurg.114, e1152–e1160 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kayan, Y. D. A. J., Fease, J. L., Tran, K., Milner, A. M. & Scholz, J. M. Incidence of delayed ipsilateral intraparenchymal hemorrhage after stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms in a high-volume single center. Neuroradiology58, 261–266 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouchaud, A. B. W., Lanzino, G., Cloft, H. J., Kadirvel, R. & Kallmes, D. F. Delayed hemorrhagic complications after flow diversion for intracranial aneurysms: A literature overview. Neuroradiology58, 171–177 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tumialán, L. M. Z. Y., Cawley, C. M., Dion, J. E., Tong, F. C. & Barrow, D. L. Intracranial hemorrhage associated with stent-assisted coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms: A cautionary report. J. Neurosurg.108, 1122–1129 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, C. B. S. W., Zhang, G. X., Lu, H. C. & Ma, J. Flow diverter treatment of posterior circulation aneurysms. A meta-analysis. Neuroradiology58, 391–400 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, X. Z. Q. et al. Stent assisted coiling versus non-stent assisted coiling for the management of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Neurointerv Surg.11, 489–496 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, L. et al. Pipeline flex embolization device for the treatment of large unruptured posterior circulation aneurysms: Single-center experience. J. Clin. Neurosci.96, 127–132 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.