Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are two common chronic airway diseases. The prevalence of both diseases is high and the 2 diseases are not mutually exclusive. Thus, there are many overlapping patients. This so-called asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) has become a hot issue in pulmonary medicine.

However, the concept of ACO is limited in several ways. Firstly, there has not yet been a firm definition. Various groups have proposed different definitions, so prevalence vary depending on which definition is used.1,2 This hinders comparative research on the phenomenon, including clinical trials. Secondly, asthma and COPD are heterogeneous diseases, making their combination even more heterogeneous. However, previous studies have tended to define ACO as a single disease entity rather than an assembly of heterogeneous endotypes. This has triggered huge debate over its definition. Thirdly, the definition of COPD is evolving. Thus, the old ACO definition may not fit with the new definition of COPD.

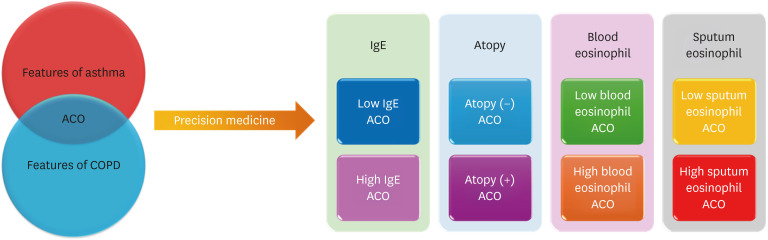

Several measures must be taken to provide precision medicine to patients with ACO. Firstly, the concept of ACO must be modified from a single disease entity to a complex of multiple heterogeneous endotypes (Fig. 1). In this issue, Shim and colleagues3 classified ACO according to T2-high and T2-low groups and reported significant heterogeneity, with clinical characteristics differing between the groups. For example, subjects with high levels of eosinophils in sputum had less lung function and showed a faster decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) than those with low levels; those with high levels of immunoglobulin E had faster declines in FEV1 over the course of 3 months vs. those with low levels; and the risk of exacerbation was higher in those with atopic ACO. This study had a strength In that it was based on a multicenter prospective cohort. Moreover, the diagnostic criteria for asthma were stringent, applied and managed by specialists in the departments of allergy or pulmonology: asthma was defined by evidence of airway hyperresponsiveness or reversibility. Another strength was its pioneering role in comprehensively classifying endotypes of ACO, thereby clarifying the heterogeneity reported in many previous studies.4,5,6,7 However, the study also had some limitations. It was based on an asthma cohort, not a COPD cohort. It would have been preferable to also include patients from a COPD cohort.6,7 Second, due to missing data, the sample sizes of some subgroups were relatively small (e.g., only 25 subjects had low levels of sputum). Nonetheless, the findings were consistent with those of several previous studies: in 2015, four different phenotypes of ACO were introduced,4 and in 2017 and 2022, the characteristics of ACO were reported to differ significantly based on smoking intensity and eosinophil levels in the blood.5,6

Fig. 1. New concept of ACO. To provide precision medicine, multiple endotypes must be identified.

ACO, asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

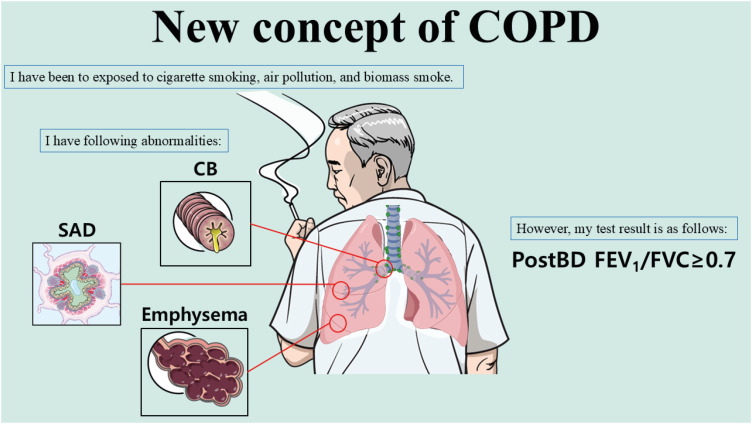

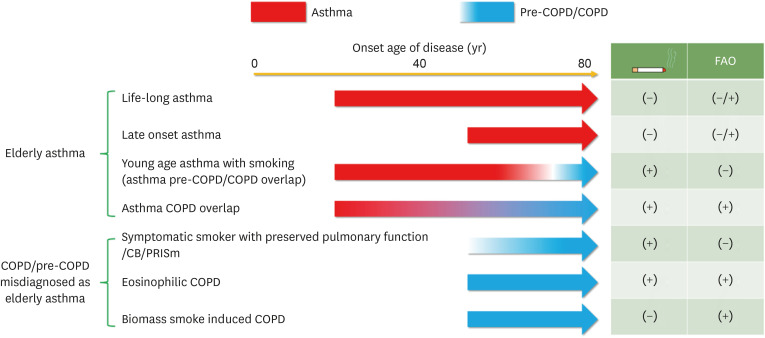

Secondly, the definition of ACO should be changed according to the new definition of COPD. In particular, fixed obstruction (post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7) is no longer an absolute condition in COPD. The Lancet Commission paper suggested that even without spirometric obstruction, COPD can be diagnosed.8 Choi and Rhee9 also suggested that the 0.7 criterion should be discarded. COPD can be defined in patients with features of COPD (chronic bronchitis/small airway disease/emphysema) (Fig. 2). Some experts have named this condition pre-COPD or preserved ratio impaired spirometry. Thus, the definition of ACO should be changed accordingly. Thirdly, more precise phenotyping is needed in elderly patients, who may have overlapping phenotypes (Fig. 3). It is extremely important to identify key factors, including history of asthma, smoking, biomass exposure, and airflow obstruction.

Fig. 2. New concept of COPD. COPD can be diagnosed without fixed airflow limitation.

The image was created with Biorender.com.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CB, chronic bronchitis; SAD, small airway disease; BD, bronchodilator; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Fig. 3. Various phenotypes of asthma, COPD and ACO in elderly patients.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ACO, asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap; CB, chronic bronchitis; PRISm, preserved ratio impaired spirometry; FAO, fixed airflow obstruction.

Finally, the effects of new pharmacologic agents should be evaluated in ACO. According to recent reports, dupilumab can positively affect COPD,10,11 making dupilumab the first biologic to prove efficacious for both asthma and COPD. However, the evidence for ACO is still lacking since ACO was excluded in both asthma and COPD trials. Further clinical trials of new medications approved in asthma or COPD are needed in patients with ACO.

There have been significant debates regarding ACO. Despite this, it is clear that patients with both asthma and COPD features do exist. In our daily clinical practice, many patients are compatible with ACO. Simply labeling these patients as ACO is insufficient. Precision medicine will necessitate the identification of ACO endotypes. Classifying ACO into T2-high and T2-low may be a good first step.

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jo YS, Hwang YI, Yoo KH, Kim TH, Lee MG, Lee SH, et al. Comparing the different diagnostic criteria of asthma-COPD overlap. Allergy. 2019;74:186–189. doi: 10.1111/all.13577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jo YS, Hwang YI, Yoo KH, Kim TH, Lee MG, Lee SH, et al. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on exacerbation of asthma-COPD overlap according to different diagnostic criteria. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1625–1633.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shim JS, Kim SY, Kim SH, Lee T, Jang AS, Park CS, et al. Clinical characteristics of T2-low and T2-high asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap: findings from COREA cohort. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2024;16:601–612. doi: 10.4168/aair.2024.16.6.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee CK. Phenotype of asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome. Korean J Intern Med. 2015;30:443–449. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.30.4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joo H, Han D, Lee JH, Rhee CK. Heterogeneity of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:697–703. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S130943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joo H, Park SY, Park SY, Park SY, Kim SH, Cho YS, et al. Phenotype of asthma-COPD overlap in COPD and severe asthma cohorts. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e236. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JY, Rhee CK, Yoo KH, Jung KS, Lee JH, Yoon HK, et al. Heterogeneity of asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap from a cohort of patients with severe asthma and COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2023;17:17534666231169472. doi: 10.1177/17534666231169472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolz D, Mkorombindo T, Schumann DM, Agusti A, Ash SY, Bafadhel M, et al. Towards the elimination of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2022;400:921–972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi JY, Rhee CK. It is high time to discard a cut-off of 0.70 in the diagnosis of COPD. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2024;18:709–719. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2024.2397480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatt SP, Rabe KF, Hanania NA, Vogelmeier CF, Bafadhel M, Christenson SA, et al. Dupilumab for COPD with blood eosinophil evidence of type 2 inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:2274–2283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2401304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt SP, Rabe KF, Hanania NA, Vogelmeier CF, Cole J, Bafadhel M, et al. Dupilumab for COPD with type 2 inflammation indicated by eosinophil counts. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:205–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2303951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]