Abstract

Purpose

Metabolic abnormalities, such as insulin resistance (IR) and dyslipidemia, have been linked to an increased risk of asthma. The triglyceride-glucose index (TyG), a metric indicating metabolic dysfunction, exhibits correlations with metabolic syndrome and IR. However, little research has been conducted on the relationship between TyG and asthma in the pediatric population. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the relationship between TyG and asthma among adolescents.

Methods

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 2007 and 2012 was analyzed in this cross-sectional study. The association between TyG and asthma was evaluated using various statistical methods, including multivariate logistic regression analysis, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis, threshold effects analysis, and subgroup analysis.

Results

A total of 1,629 adolescent participants were enrolled in the study, consisting of 878 (53.9%) males and 751 females (46.1%), with a mean age of 15.5 years. After adjusting for all covariates in the multivariate logistic regression, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for TyG and asthma in the highest quintile (Q5, > 8.65) was 4.26 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.54, 11.81; P = 0.005) compared to the TyG in the second quintile (Q2, 7.68–7.96). Additionally, the multivariate RCS analysis revealed a non-linear relationship between TyG and asthma (P = 0.003). In the threshold analysis, the adjusted OR of asthma was 0.001 (95% CI, 0, 0.145; P = 0.007) in participants with a TyG < 7.78, and the adjusted OR of asthma was 3.685 (95% CI, 1.499, 9.058; P = 0.004) in participants with a TyG ≥ 7.78. Subgroup analysis did not show any interactive role for TyG and asthma.

Conclusions

In US adolescents, a U-shaped association was observed between asthma and the TyG, with a critical turning point identified at around 7.78.

Keywords: Dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, metabolic disease, asthma, adolescent

INTRODUCTION

Asthma, characterized by airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, is the most prevalent chronic respiratory condition during childhood. Over recent decades, the prevalence of asthma has experienced a steady rise, placing considerable strain on healthcare systems and adversely impacting the well-being of affected individuals. Among children, the overall prevalence of asthma was reported to be at 9.1%, while among adolescents, it was slightly elevated at 11.0%.1 While numerous risk factors for asthma have been identified, emerging evidence suggests a potential association between metabolic disturbances and the development of asthma.

Assessing insulin resistance (IR) and metabolic syndrome in the general population presents challenges due to the invasiveness of the gold standard diagnostic method, the high insulin-normal glucose clamp.2 As a result, alternative laboratory measures have garnered interest, with the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG), which has emerged as a promising biomarker for assessing metabolic syndrome, offering valuable insights into IR, metabolic dysregulation, and systemic inflammation.3,4,5 Derived from fasting glucose and triglyceride levels,3 a higher level of TyG is associated with cardiovascular outcomes and incidence of diabetes.6,7 Notably, TyG has emerged as a superior biomarker compared to the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), owing to its simplicity and strong correlation with metabolic abnormalities.8 Although the association between TyG and metabolic disorders is well-established, its potential relationship with asthma remains relatively unexplored, particularly in the adolescent population.

This cross-sectional study aims to investigate the association between TyG and asthma among US adolescents, utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The hypothesis posits a dose-response connection between asthma and TyG, suggesting that both low and high levels of TyG are linked to an elevated risk of asthma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and study population

This cross-sectional study used data from 2007–2012 NHANES, a national survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) aimed at evaluating the health and nutritional status of the noninstitutionalized population in the US.9 NHANES gathered demographic data and a diverse range of health-related information through household visits, screening assessments, and laboratory analyses conducted at a mobile examination center. Approval for the NHANES study protocol was granted by the Research Ethics Review Board at the NCHS, and all participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment.10 No further Institutional Review Board approval was necessary for secondary analysis. The present study included individuals aged between 12 and 20 years who completed the survey. Participants who lacked information about asthma, fasting triglyceride, and fasting glucose were eliminated.

Asthma assessment

To identify participants with asthma, we evaluated their responses to the questions “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you have asthma?” and “Do you still have asthma?” in the Medical Condition Questionnaire. Only those who answered ‘Yes’ to both questions were classified as having asthma, while those who answered ‘No’ to either question were classified as non-asthmatic.

TyG measurement

Enzymatic techniques were employed with an autoanalyzer to assess plasma fasting glucose and serum fasting triglyceride levels. TyG was computed using the formula3: Ln [Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) × Fasting Triglycerides (mg/dL)/2]. Participants were then stratified into quintiles (Q1–Q5) according to their TyG levels for analysis.

Covariates definitions

A variety of covariates were obtained according to prior literature requirements,11 including sex, age, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI) category, family income, smoke exposure, family history of asthma, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), white blood cells (WBCs), eosinophils percent (EOPC), hemoglobin (HGB), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), glycohemoglobin (HbA1c), diabetes, HOMA-IR, onset age of asthma, and asthma treatment. The categorization of race/ethnicity consisted of 5 groups: Mexican American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and other races. BMI categories were determined using age- and sex-specific growth charts as advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12 These categories were defined as follows: underweight (less than 5th percentile), normal weight (5th to 84.9th percentile), overweight (85th to 94.9th percentile), and obese (more than 95th percentile). The poverty income ratio (PIR) divided family income into 3 categories: low (PIR ≤ 1.3), medium (1.3–3.5), and high (PIR > 3.5).13 Smoke exposure was identified by the level of serum cotinine into 3 groups: non-exposure (< 1 ng/mL), heavy exposure (1–10 ng/mL), and active smokers (> 10 ng/mL).14 HOMA-IR was computed using the formula15: [Fasting Insulin (mU/L) × Fasting Glucose (mmol/L)]/22.5. Subsequently, in subgroup analysis, HOMA-IR was categorized into 2 groups: < 3 denoted normal, while ≥ 3 indicated IR.16 The receipt of asthma treatment was ascertained based on the responses to the question: “During the past 3 months, have you taken medication prescribed by a doctor or other healthcare professionals for asthma?” Those who answered affirmatively were classified as having received asthma treatment, whereas those who responded in the negative were classified as having not received treatment for asthma.17

Multiple single imputation was utilized for 392 participants (2.4%) with missing data pertaining to the mentioned covariates. During each step of the round-robin imputation process, a Bayesian Ridge model was employed as the estimator.18

Statistical analysis

The present study is a secondary analysis of a publicly accessible database. Continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range), while categorical variables are presented as percentages. To compare the baseline characteristics among different TyG groups, statistical differences were assessed using t-tests or one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

We conducted multivariate logistic regression to assess the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between TyG and asthma. Model 1 was adjusted for sociodemographic factors, comprising sex, age, race/ethnicity, BMI category, and PIR. In Model 2, additional adjustments were made for family history of asthma, smoke exposure, SBP, DBP, WBC, EOPC, and HGB. Lastly, Model 3 included full adjustments with additional variables, such as HDL-C, HbA1c, diabetes status, asthma treatment, and HOMA-IR.

We employed restricted cubic splines (RCSs) with 4 knots to explore linearity and evaluate the dose-response relationship between TyG and asthma, while adjusting for covariates in Model 3. Additionally, we conducted a piecewise logistic regression model to assess the threshold association between TyG and asthma, with the aim of identifying specific cut-off points where the risk of asthma undergoes a significant change as a function of varying TyG levels and to ascertain the TyG level that is associated with an elevated risk of asthma, thereby providing guidance for clinical assessments and interventions.

Furthermore, to assess the consistency of the association between TyG and asthma across various subgroups, interaction and subgroup analyses were conducted based on sex, BMI category, family asthma history, and HOMA-IR.

Finally, several sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, participants with missing covariates were excluded to ensure consistency in the patterns observed in the single imputation analysis, multivariable logistic regression and RCS were utilized to further investigate these trends. Second, in order to evaluate the correlation between TyG and current asthma status, we conducted an analysis to determine the relationship between TyG and forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1). Subsequently, the participants were screened for asthma to further investigate the relationship between TyG and the duration of asthma, as well as the receipt of asthma treatment.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (Version 4.2.2; The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria; http://www.R-project.org) and the Free Statistics analysis software (Version 1.9; Beijing Free Clinical Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value of < 0.05.

RESULTS

Study population

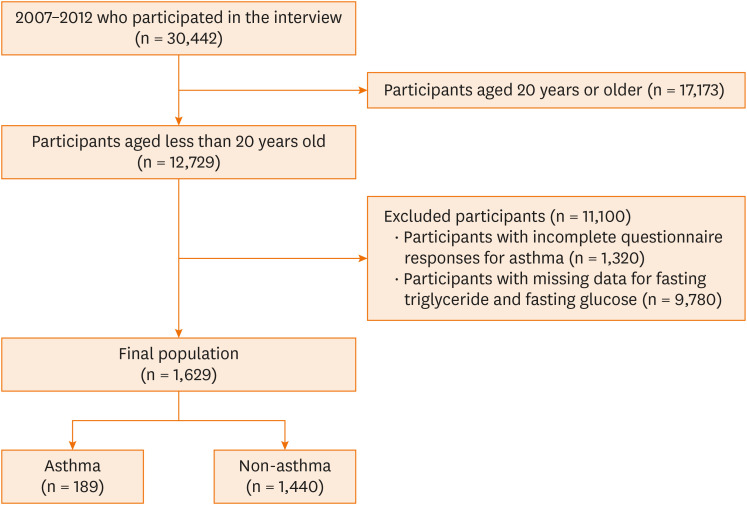

Data from 3 NHANES release cycles (2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012) were extracted for analysis. Out of the 30,442 participants who completed the survey, 17,713 were aged 20 years or older. Among the remaining 12,729 respondents, those with incomplete answers for asthma (1,320), and those with missing data for fasting triglyceride and fasting glucose (n = 9,780) were excluded. In all, a total of 1,629 participants met the inclusion criteria of the present study, of which 189 reported having asthma (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of this study.

Baseline characteristics

We enrolled a total of 1,629 patients with a mean age of 15.5 (± 2.3 years). Among these participants, 29.6% were identified as non-Hispanic white ethnicity and 53.9% were male. The overall prevalence of asthma in the study population was 11.6%, with an onset age of asthma of 5 years. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants stratified by quintiles of TyG. The groups categorized based on TyG levels exhibited significant differences in terms of sex, race/ethnicity, BMI category, PIR, smoke exposure, waist circumference, SBP, WBC, HGB, HDL-C, HbA1c, diabetes, and HOMA-IR (all P < 0.05). Conversely, there were no significant variations in the distribution of patient characteristics including age, DBP, and EOPC across the different TyG groups (all P > 0.05).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics categorized by TyG.

| Variables | TyG | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1,629) | Q1 (< 7.68) (n = 324) | Q2 (7.68–7.96) (n = 317) | Q3 (7.97–8.22) (n = 333) | Q4 (8.23–8.56) (n = 329) | Q5 (> 8.65) (n = 326) | |||

| Sex | 0.045 | |||||||

| Male | 878 (53.9) | 157 (49.5) | 170 (51.1) | 177 (54.6) | 176 (53.5) | 198 (60.7) | ||

| Female | 751 (46.1) | 160 (50.5) | 163 (48.9) | 147 (45.4) | 153 (46.5) | 128 (39.3) | ||

| Age (yr) | 15.5 ± 2.3 | 15.5 ± 2.2 | 15.5 ± 2.3 | 15.3 ± 2.2 | 15.6 ± 2.3 | 15.7 ± 2.4 | 0.151 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Mexican American | 376 (23.1) | 62 (19.6) | 77 (23.1) | 57 (17.6) | 87 (26.4) | 93 (28.5) | ||

| Other Hispanic | 192 (11.8) | 24 (7.6) | 38 (11.4) | 31 (9.6) | 44 (13.4) | 55 (16.9) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 482 (29.6) | 94 (29.7) | 96 (28.8) | 62 (19.1) | 119 (36.2) | 111 (34) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 420 (25.8) | 106 (33.4) | 77 (23.1) | 146 (45.1) | 48 (14.6) | 43 (13.2) | ||

| Other/Multi-racial | 159 (9.8) | 31 (9.8) | 45 (13.5) | 28 (8.6) | 31 (9.4) | 24 (7.4) | ||

| BMI category | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Underweight | 45 (2.8) | 13 (4.1) | 7 (2.1) | 10 (3.1) | 10 (3) | 5 (1.5) | ||

| Normal weight | 959 (58.9) | 200 (63.1) | 203 (61) | 232 (71.6) | 187 (56.8) | 137 (42) | ||

| Overweight | 289 (17.7) | 64 (20.2) | 53 (15.9) | 50 (15.4) | 64 (19.5) | 58 (17.8) | ||

| Obese | 336 (20.6) | 40 (12.6) | 70 (21) | 32 (9.9) | 68 (20.7) | 126 (38.7) | ||

| PIR | 0.030 | |||||||

| Low (< 1.3) | 713 (43.8) | 129 (40.7) | 125 (37.5) | 146 (45.1) | 145 (44.1) | 168 (51.5) | ||

| Median (1.3–3.5) | 589 (36.2) | 123 (38.8) | 136 (40.8) | 114 (35.2) | 110 (33.4) | 106 (32.5) | ||

| High (> 3.5) | 327 (20.1) | 65 (20.5) | 72 (21.6) | 64 (19.8) | 74 (22.5) | 52 (16) | ||

| Smoke exposure | 0.041 | |||||||

| Non-exposure (< 1 ng/mL) | 1,276 (78.3) | 261 (82.3) | 264 (79.3) | 263 (81.2) | 255 (77.5) | 233 (71.5) | ||

| Heavy exposure (1–10 ng/mL) | 155 (9.5) | 25 (7.9) | 30 (9) | 31 (9.6) | 28 (8.5) | 41 (12.6) | ||

| Active smokers (> 10 ng/mL) | 198 (12.2) | 31 (9.8) | 39 (11.7) | 30 (9.3) | 46 (14) | 52 (16) | ||

| Family asthma | 0.255 | |||||||

| Yes | 511 (31.4) | 104 (32.8) | 119 (35.7) | 98 (30.2) | 98 (29.8) | 92 (28.2) | ||

| No | 1,118 (68.6) | 213 (67.2) | 214 (64.3) | 226 (69.8) | 231 (70.2) | 234 (71.8) | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 81.8 ± 14.7 | 78.5 ± 12.3 | 81.3 ± 14.2 | 76.3 ± 10.2 | 82.8 ± 14.4 | 89.8 ± 17.4 | < 0.001 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 109.2 ± 10.5 | 108.4 ± 9.8 | 108.9 ± 10.1 | 108.4 ± 10.3 | 109.3 ± 10.7 | 111.1 ± 11.4 | 0.006 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 58.6 ± 12.5 | 58.2 ± 12.3 | 58.8 ± 12.3 | 58.7 ± 11.1 | 58.4 ± 12.7 | 59.1 ± 13.9 | 0.893 | |

| WBC (1,000 cells/uL) | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 7.3 ± 2.3 | < 0.001 | |

| EOPC (%) | 2.6 (1.7, 4.3) | 2.6 (1.6, 3.9) | 2.6 (1.7, 4.3) | 2.8 (1.7, 4.6) | 2.4 (1.6, 4.0) | 2.7 (1.7, 4.2) | 0.663 | |

| HGB (g/dL) | 14.1 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.3 | 14.0 ± 1.3 | 13.7 ± 1.3 | 14.2 ± 1.4 | 14.4 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 | |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 52.7 ± 12.1 | 56.1 ± 11.8 | 53.7 ± 11.7 | 58.3 ± 11.3 | 50.6 ± 10.5 | 45.1 ± 10.5 | < 0.001 | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 0.007 | |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Yes | 11 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 8 (2.5) | ||

| No | 1,608 (98.7) | 316 (99.7) | 329 (98.8) | 323 (99.7) | 328 (99.7) | 312 (95.7) | ||

| Borderline | 10 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.8) | ||

| HOMA-IR | 2.7 (1.9, 4.2) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.4) | 2.7 (1.9, 4.1) | 2.2 (1.5, 3.1) | 2.9 (2.0, 4.3) | 4.1 (2.7, 6.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Onset age of asthma (yr) | 5.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 6.0 (2.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (2.0, 9.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 10.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 8.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Asthma treatment | 0.661 | |||||||

| Yes | 128 (7.9) | 28 (8.8) | 23 (6.9) | 21 (6.5) | 30 (9.1) | 26 (8) | ||

| No | 1,501 (92.1) | 289 (91.2) | 310 (93.1) | 303 (93.5) | 299 (90.9) | 300 (92) | ||

| Asthma | 0.347 | |||||||

| Yes | 189 (11.6) | 32 (10.1) | 33 (9.9) | 36 (11.1) | 41 (12.5) | 47 (14.4) | ||

| No | 1,440 (88.4) | 285 (89.9) | 300 (90.1) | 288 (88.9) | 288 (87.5) | 279 (85.6) | ||

Values are presented as number (%), mean ± standard deviation or mean (range).

TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; BMI, body mass index; PIR, ratio of income to poverty; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; WBC, white blood cell; EOPC, eosinophils percent; HGB, hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HbA1c, glycohemoglobin; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance.

Association between TyG and asthma

The univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that race/ethnicity, BMI category, smoke exposure, family history of asthma, WBC, EOPC, diabetes, and HOMA-IR were significantly associated with asthma (Supplementary Table S1).

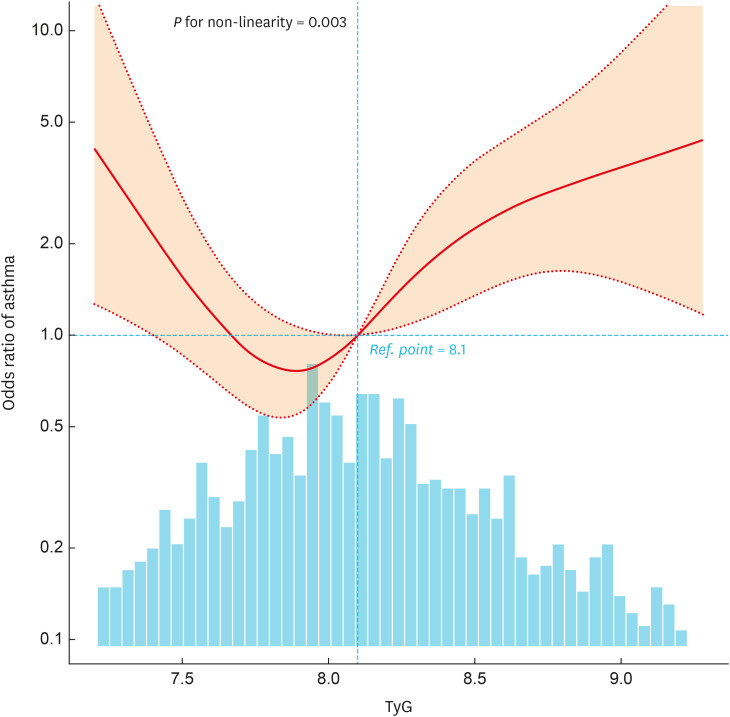

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for all potential covariates, individuals with the highest TyG values (> 8.65) exhibited a 4.26-fold increased risk of asthma compared to those with lower TyG values in Q2 (7.68–7.96) (OR, 4.26; 95% CI, 1.54, 11.81; P = 0.005) (Table 2). In order to investigate the presence of a dose-response relationship between TyG and the risk of asthma, an RCS analysis was conducted. After controlling for potential confounding factors, a nonlinear association between TyG and asthma was identified (P for nonlinearity = 0.003) (Fig. 2). Notably, in the threshold analysis, the OR of developing asthma was 0.001 (95% CI, 0, 0.145; P = 0.007) among the participants with a TyG < 7.78. When TyG exceeded 7.78, the OR for the risk of developing asthma shifted to 3.685 (95% CI, 1.499, 9.058; P = 0.004). This finding suggests a U-shaped relationship between TyG levels and the incidence of asthma; both low and high levels of TyG were associated with an elevated risk of asthma (Table 3).

Table 2. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and asthma.

| Quintiles | Total | No. (%) | Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Q2 (7.68–7.96) | 317 | 32 (10.1) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||||

| Q1 (< 7.68) | 324 | 36 (11.1) | 1.11 (0.67, 1.84) | 0.676 | 1.08 (0.65, 1.81) | 0.764 | 1.22 (0.7, 2.13) | 0.479 | 2.61 (0.99, 6.86) | 0.051 |

| Q3 (7.97–8.22) | 333 | 33 (9.9) | 0.98 (0.59, 1.64) | 0.937 | 1.08 (0.64, 1.82) | 0.780 | 1.05 (0.6, 1.84) | 0.853 | 1.87 (0.68, 5.1) | 0.225 |

| Q4 (8.23–8.56) | 329 | 41 (12.5) | 1.27 (0.78, 2.07) | 0.343 | 1.45 (0.87, 2.4) | 0.153 | 1.53 (0.88, 2.64) | 0.129 | 2.54 (0.94, 6.88) | 0.066 |

| Q5 (> 8.65) | 326 | 47 (14.4) | 1.5 (0.93, 2.42) | 0.097 | 1.63 (0.98, 2.71) | 0.061 | 1.85 (1.05, 3.25) | 0.033 | 4.26 (1.54, 11.81) | 0.005 |

| P for trend | 1,629 | 0.111 | 0.046 | 0.059 | 0.112 | |||||

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index category, poverty income ratio; Model 2 was adjusted for Model 1 + family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin; Model 3 was adjusted for Model 2 + high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 2. Association between TyG and asthma odds ratio. Solid and dashed lines represent the predicted value and 95% confidence intervals. They were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index category, poverty income ratio, family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance. Only 95% of the data is shown.

TyG, triglyceride-glucose index.

Table 3. Threshold effect analysis of the relationship between TyG and asthma.

| TyG | Adjusted model | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| < 7.78 | 0.001 (0, 0.145) | 0.007 |

| ≥ 7.78 | 3.685 (1.499, 9.058) | 0.004 |

| Likelihood ratio test | < 0.001 | |

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index category, poverty income ratio, family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance. Only 95% of the data is displayed.

TyG, triglyceride-glucose index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Stratified analyses based on additional variables and sensitivity analyses

Stratified analyses revealed that the no significant interactions across all subgroups when stratified by sex, BMI category, family history of asthma, and HOMA-IR (Supplementary Fig. S1).

In addition, sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding participants with missing variables. Results remained constant after adjusting the model for multivariate logistic regression and RCS analysis (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Fig. S2).

To further assess the robustness of the main findings, we calculated E values to evaluate the potential impact of unmeasured confounding variables. The results indicated that the association between TyG and asthma was robust unless the OR for the risk of asthma due to an unmeasured confounder reached 7.987. Subsequently, we explored the correlation between FEV1 and TyG, thereby evaluating the association between the current severity of asthma and TyG. After adjusting for all covariates in the multiple linear regression analysis, a negative correlation was identified between FEV1 and TyG, with a reduction of 91.62 mL for each unit increase in TyG (β = −91.62; 95% CI, −155.2, −28.04; P = 0.005) (Supplementary Table S3). This finding suggests that elevated TyG levels may be associated with diminished lung function. Moreover, asthmatics were selected for further investigation of the relationship between the TyG and the duration of asthma. After adjusting for all covariates, a positive correlation was observed between the TyG and the duration of asthma (β = 0.39; 95% CI, −1.22, 2; P = 0.634). However, the association was not statistically significant (Supplementary Table S4). We ultimately examined the correlation between asthma treatment status and the TyG within this population. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, asthmatics with the highest TyG quintile (Q5, > 8.65) exhibited an OR value of 4.09 (95% CI, 1.11, 15.1; P = 0.034), compared to those with lower TyG quintile (Q2, 7.70–7.96) (Supplementary Table S5). These findings suggest that individuals with higher TyG values are less likely to be receiving asthma treatment, indicating a significant relationship between elevated TyG levels and untreated asthma.

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional study of American adolescents demonstrated a U-shaped relationship between TyG and asthma in US adolescents, with a turning point of 7.78. These findings suggest that both elevated and diminished TyG levels are linked to an elevated risk of asthma. A grasp of this threshold is of paramount importance for clinicians, as it enables the identification of patients at elevated risk of asthma based on their TyG levels. This, in turn, facilitates the implementation of more targeted preventive measures and treatments. Furthermore, subgroup analysis within the study population did not reveal any significant interactions between different subgroups. Sensitivity analysis revealed that this association remained robust.

Additionally, we observed a seemingly contradictory result in the additional analysis, where higher TyG levels were associated with both an increased risk of asthma and a higher likelihood of untreated asthma. This paradox can be explained by considering socioeconomic and healthcare access disparities. Individuals with higher TyG may have poorer overall metabolic health, often linked to lower socioeconomic status and limited healthcare access.19,20 Consequently, this population may have more severe asthma that remains untreated due to barriers in accessing healthcare services.21,22

Over the past few years, there has been a growing emphasis on exploring the correlation between metabolic markers and respiratory conditions, notably asthma. A study conducted by Michael in adults found that IR was common among asthmatics and was associated with a poor response to bronchodilators and corticosteroids.16 Forno et al.23 reported that IR and metabolic syndrome had a significant relationship with worsened lung function in US adolescents, and this effect was even worse among those who had asthma. A Danish cohort study demonstrated IR as an important predictor for the onset of asthma-like symptoms.24 In addition, several previous studies have indicated a correlation between serum lipids and asthma.25,26,27 These studies have suggested a strong association between asthma and metabolic abnormalities. TyG, encompassing both IR and dyslipidemia components, offers a more comprehensive assessment of metabolic dysregulation. Consequently, it holds promise as a valuable marker to explore the association between metabolic dysfunction and asthma.

However, the relationship between TyG and asthma has only been explored in a limited number of studies, and the conclusions drawn from these studies have been inconsistent. Staggers et al.28 reported that TyG was associated with the risk of asthma exacerbation utilizing data from the Veterans Health Administration. Wu et al.11 discovered TyG as a potential risk factor for compromised respiratory function, displaying a robust correlation with restrictive spirometry pattern and various respiratory symptoms. Nevertheless, their findings did not reveal a noteworthy association between the index and asthma. This inconsistency with our present study might stem from variations in study populations. While Wu et al.11 concentrated on adults aged ≥ 40 years, our investigation centered on adolescents. In contrast to the prior research, our study unveiled a non-linear correlation between TyG and asthma. We found that both low and high TyG levels were linked to heightened asthma risk. Further multicenter randomized controlled trials are imperative to elucidate the precise impact of TyG on asthma among adolescents in the future.

While the precise mechanism underlying the U-shaped relationship between TyG and asthma remains incompletely understood, our findings align with biological plausibility supported by existing evidence. First, elevated TyG levels reflect IR, a condition characterized by impaired insulin action and compensatory hyperinsulinemia. IR may affect airway smooth muscle, leading to increased contractility, proliferation, and remodeling.29 This can result in airway hyperresponsiveness and bronchoconstriction, key features of asthma pathophysiology. In addition, hypoglycemia can induce increased inflammatory cytokines and leukocytosis,30,31 suggesting a link between hypoglycemia and inflammation. This may contribute to airway hyperresponsiveness and worsen asthma control. Furthermore, dyslipidemia, indicated by the triglyceride levels in TyG, may also contribute to asthma risk. Triglycerides may modulate immune cell function and polarization, leading to dysregulated immune responses in asthma.32,33 In conclusion, TyG, serves as a comprehensive biomarker of metabolic dysregulation, has the potential to link metabolic syndrome and asthma.

The strengths of our study lie in the utilization of a relatively large population-based cohort, which provided ample statistical power to investigate the relationship between TyG and asthma in adolescents. Additionally, through rigorous statistical analyses, including multivariate logistic regression, RCS analysis, and stratified analysis, the present study offers compelling evidence regarding the correlation between TyG levels and the risk of asthma. However, there are certain limitations to our study. Firstly, despite extensive efforts to adjust for numerous important confounders, the possibility of unmeasured confounders linked to asthma risk, such as allergen, and rhinitis, which were not included in the 2007–2012 NHANES database, cannot be entirely ruled out. Nevertheless, the sensitivity analysis utilizing the E-value methodology yielded E-values higher than the reported strength of associations between allergens and asthma,34,35,36 indicating that allergens are less likely to diminish the association in our study. We acknowledge the potential influence of residual measured or unmeasured confounding on our findings. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design of the study hinders our ability to establish a causal link between TyG and asthma. Lastly, the study was limited to participants of American population, thus the generalizability of our findings to non-American populations may be limited. Consequently, well-designed multicenter randomized controlled trials are imperative to validate our results.

In summary, The present study revealed a U-shaped relationship between the TyG and asthma in American adolescents, with a cut-off point of approximately 7.78. The presence of a single cut-off value in a U-shaped curve underscores the importance of considering both ends of the spectrum when assessing asthma risk. This finding highlights the index as a potential epidemiologic biomarker to link metabolic irregularity and asthma within adolescents, as it allows for more precise identification of individuals at higher risk and enables more targeted preventive and therapeutic strategies. Further exploration is warranted to elucidate the intricate relationships between TyG levels and asthma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was sponsored by Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Program of Fuzhou, Fujian, P.R.C.

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Association of covariates and asthma risk

Association between triglyceride-glucose index and asthma after deletion of missing covariates

Association between forced expiratory volume in the first second and TyG

Association between duration of asthma and TyG

Association between asthma treatment status and triglyceride-glucose index within asthmatics

Forest plot of multivariable logistics analysis between triglyceride-glucose index and asthma. Except for the stratification component itself, each stratification factor was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI category, poverty income ratio, family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, and HOMA-IR.

Association between TyG and asthma odds ratio after deletion of missing covariates. Solid and dashed lines represent the predicted value and 95% confidence intervals. They were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index category, poverty income ratio, family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance. Only 95% of the data is shown.

References

- 1.The Global Asthma Report 2022. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022;26:1–104. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.22.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh B, Saxena A. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance: a review. World J Diabetes. 2010;1:36–47. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v1.i2.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrero-Romero F, Simental-Mendía LE, González-Ortiz M, Martínez-Abundis E, Ramos-Zavala MG, Hernández-González SO, et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3347–3351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Son DH, Lee HS, Lee YJ, Lee JH, Han JH. Comparison of triglyceride-glucose index and HOMA-IR for predicting prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;32:596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Q, Zhang TY, Cheng YJ, Ma Y, Xu YK, Yang JQ, et al. Impacts of triglyceride-glucose index on prognosis of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from an observational cohort study in China. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:108. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Che B, Zhong C, Zhang R, Pu L, Zhao T, Zhang Y, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index and triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio as potential cardiovascular disease risk factors: an analysis of UK biobank data. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:34. doi: 10.1186/s12933-023-01762-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Sun M, Yang Y, Yao N, Yan S, Wang L, et al. Predictive effect of triglyceride glucose-related parameters, obesity indices, and lipid ratios for diabetes in a Chinese population: a prospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:862919. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.862919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasques AC, Novaes FS, de Oliveira MS, Souza JR, Yamanaka A, Pareja JC, et al. TyG index performs better than HOMA in a Brazilian population: a hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93:e98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES survey methods and analytic guidelines [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES-NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approval [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu TD, Fawzy A, Brigham E, McCormack MC, Rosas I, Villareal DT, et al. Association of triglyceride-glucose index and lung health: a population-based study. Chest. 2021;160:1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Growth charts: data file for the CDC extended BMI-for-age growth charts [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/extended-bmi-data-files.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. WWEIA data tables [Internet] Washington, D.C.: Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2022. [cited 2024 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/wweia-data-tables/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hukkanen J, Jacob P, 3rd, Benowitz NL. Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:79–115. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters MC, Schiebler ML, Cardet JC, Johansson MW, Sorkness R, DeBoer MD, et al. The impact of insulin resistance on loss of lung function and response to treatment in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:1096–1106. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2745OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES 2011–2012 questionnaire instruments [Internet] Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [cited 2024 Jun 18]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/questionnaires.aspx?BeginYear=2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Soft. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saki N, Hashemi SJ, Hosseini SA, Rahimi Z, Rahim F, Cheraghian B. Socioeconomic status and metabolic syndrome in Southwest Iran: results from Hoveyzeh Cohort Study (HCS) BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:332. doi: 10.1186/s12902-022-01255-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volaco A, Cavalcanti AM, Filho RP, Précoma DB. Socioeconomic status: the missing link between obesity and diabetes mellitus? Curr Diabetes Rev. 2018;14:321–326. doi: 10.2174/1573399813666170621123227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cesaroni G, Farchi S, Davoli M, Forastiere F, Perucci CA. Individual and area-based indicators of socioeconomic status and childhood asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:619–624. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00091202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uphoff E, Cabieses B, Pinart M, Valdés M, Antó JM, Wright J. A systematic review of socioeconomic position in relation to asthma and allergic diseases. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:364–374. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forno E, Han YY, Muzumdar RH, Celedón JC. Insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and lung function in US adolescents with and without asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:304–311.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thuesen BH, Husemoen LL, Hersoug LG, Pisinger C, Linneberg A. Insulin resistance as a predictor of incident asthma-like symptoms in adults. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:700–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cottrell L, Neal WA, Ice C, Perez MK, Piedimonte G. Metabolic abnormalities in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:441–448. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0603OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yiallouros PK, Savva SC, Kolokotroni O, Behbod B, Zeniou M, Economou M, et al. Low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in childhood is associated with adolescent asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:423–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fenger RV, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Linneberg A, Husemoen LL, Thuesen BH, Aadahl M, et al. The relationship of serum triglycerides, serum HDL, and obesity to the risk of wheezing in 85,555 adults. Respir Med. 2013;107:816–824. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staggers KA, Minard C, Byers M, Helmer DA, Wu TD. Metabolic dysfunction, triglyceride-glucose index, and risk of severe asthma exacerbation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11:3700–3705.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dekkers BG, Schaafsma D, Tran T, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. Insulin-induced laminin expression promotes a hypercontractile airway smooth muscle phenotype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:494–504. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0251OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joy NG, Tate DB, Younk LM, Davis SN. Effects of acute and antecedent hypoglycemia on endothelial function and markers of atherothrombotic balance in healthy humans. Diabetes. 2015;64:2571–2580. doi: 10.2337/db14-1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Razavi Nematollahi L, Kitabchi AE, Stentz FB, Wan JY, Larijani BA, Tehrani MM, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines in response to insulin-induced hypoglycemic stress in healthy subjects. Metabolism. 2009;58:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X, Paulsson G, Stemme S, Hansson GK. Hypercholesterolemia is associated with a T helper (Th) 1/Th2 switch of the autoimmune response in atherosclerotic apo E-knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1717–1725. doi: 10.1172/JCI1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fessler MB, Parks JS. Intracellular lipid flux and membrane microdomains as organizing principles in inflammatory cell signaling. J Immunol. 2011;187:1529–1535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubner FJ, Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, Tisler CJ, Pappas TE, et al. Early life rhinovirus wheezing, allergic sensitization, and asthma risk at adolescence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharpe RA, Thornton CR, Tyrrell J, Nikolaou V, Osborne NJ. Variable risk of atopic disease due to indoor fungal exposure in NHANES 2005-2006. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:1566–1578. doi: 10.1111/cea.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CH, Chao HJ, Chan CC, Chen BY, Guo YL. Current asthma in schoolchildren is related to fungal spores in classrooms. Chest. 2014;146:123–134. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Association of covariates and asthma risk

Association between triglyceride-glucose index and asthma after deletion of missing covariates

Association between forced expiratory volume in the first second and TyG

Association between duration of asthma and TyG

Association between asthma treatment status and triglyceride-glucose index within asthmatics

Forest plot of multivariable logistics analysis between triglyceride-glucose index and asthma. Except for the stratification component itself, each stratification factor was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI category, poverty income ratio, family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, and HOMA-IR.

Association between TyG and asthma odds ratio after deletion of missing covariates. Solid and dashed lines represent the predicted value and 95% confidence intervals. They were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index category, poverty income ratio, family asthma, smoke exposure, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, white blood cell, eosinophils percent, hemoglobin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glycohemoglobin, diabetes, asthma treatment, and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance. Only 95% of the data is shown.