Abstract

Introduction

Parathyroid carcinoma is an exceptionally rare endocrine malignancy, constituting <1 % of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) cases. It presents with more severe hypercalcemia and higher PTH levels than benign parathyroid diseases, requiring increased clinical awareness for accurate identification and specialized management. The results of this case series may provide insight into the clinical presentation, diagnostic workup, surgical management, and prognosis of parathyroid carcinoma, supplemented by a comprehensive review of current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed three cases of parathyroid carcinoma treated at a tertiary referral hospital. We analyzed patient demographics, clinical presentation, imaging studies, surgical interventions, histopathological findings, and follow-up data. We emphasized intraoperative decisions, criteria for achieving sustained hormonal control, and long-term monitoring protocols.

Results

Patient 1: An 84-year-old male patient presented with severe hypercalcemia and elevated PTH levels. Preoperative imaging, including 4D CT and sestamibi scan, identified a 3.7 cm, 9.32-gram parathyroid mass, which was surgically resected. Despite removing the mass and normalizing calcium levels, PTH levels remained elevated, suggesting residual disease.

Patient 2: A 77-year-old male patient with osteoporosis and a history of kidney stones underwent presurgical parathyroid scintigraphy, which indicated a right superior parathyroid adenoma. A 3 cm, 3.55-gram parathyroid carcinoma was successfully removed, normalizing calcium and PTH levels. Follow-up imaging and labs confirmed no recurrence.

Patient 3: A 61-year-old female patient with end-stage renal disease presented with a 5 cm hypervascular neck mass. Preoperative 4D CT and ultrasound suggested an adenoma. After surgery, PTH levels normalized, but the patient died five years later from an unrelated stroke.

Conclusion

Parathyroid carcinoma is a rare malignancy that demands thorough diagnostic procedures, imaging techniques, precise surgical intervention, and vigilant long-term follow-up to manage the risk of recurrence. Elevated PTH and calcium levels should raise suspicion of malignancy, especially in severe hypercalcemia. This case series illustrates how the disease can present variably, with unique challenges in each patient. Despite the limitations of current adjuvant therapies, advancements in genetic and molecular research hold promise for future therapeutic options.

Keywords: Parathyroid carcinoma, Hyperparathyroidism, Hypercalcemia, PTH, En bloc resection

Highlights

-

•

Parathyroid carcinoma is hard to diagnose due resembling benign conditions and possible hypercalcemia and elevated PTH.

-

•

Management requires a high index of suspicion, thorough diagnostic workup, and meticulous surgical intervention.

-

•

Intraoperative PTH monitoring is crucial for ensuring complete tumor removal.

-

•

The disease's indolent nature requires rigorous, long-term follow-up, as it is resistant to conventional radio and chemotherapy.

-

•

A multidisciplinary team involving endocrinology, surgery, oncology, and pathology is essential for good patient outcomes.

1. Introduction

Parathyroid carcinoma is an exceedingly rare malignancy, representing <1 % of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) [1,2]. First described by Sainton and Millot in 1933, this carcinoma is the least commonly encountered endocrine malignancy worldwide [3]. Unlike benign parathyroid disease, parathyroid carcinoma is typically associated with more severe manifestations of hypercalcemia, including marked elevations in serum calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels [4,5]. These severe biochemical abnormalities often lead to pronounced clinical symptoms such as osteoporosis, nephrolithiasis, and neuromuscular disturbances [6,7].

The etiology of parathyroid carcinoma involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors [8]. While exposure to radiation, particularly during childhood, has been implicated in the development of benign parathyroid disease, its role in parathyroid carcinoma remains less clear [1,9]. Genetic predispositions, particularly germline mutations in the CDC73 gene (formerly HRPT2), play a significant role [8]. This gene encodes the protein parafibromin, a tumor suppressor whose loss of function is linked to the pathogenesis of both familial and sporadic forms of the disease [8].

Diagnosing parathyroid carcinoma preoperatively is challenging due to its clinical and biochemical overlap with benign conditions such as parathyroid adenomas and hyperplasia [10]. Imaging studies, including ultrasound, 4D CT, and sestamibi scans, are useful for localizing the tumor and assessing its extent [11]. However, definitive diagnosis relies on histopathological examination post-surgery, as preoperative biopsies are generally contraindicated due to the risk of tumor seeding and diagnostic artifacts [4,12].

The primary treatment for parathyroid carcinoma is surgical, with en bloc resection being the preferred approach to ensure complete removal of the tumor and reduce the risk of recurrence [11]. Intraoperative PTH monitoring is essential to confirm the success of the resection [13]. Despite surgical advances, recurrence remains a significant concern, necessitating rigorous long-term follow-up [1,14]. Adjuvant therapies, including radiation and chemotherapy, have shown limited success, but ongoing research into targeted molecular and immunotherapies holds promise for future treatment options [11,15].

Given the rarity of parathyroid carcinoma, continued research and multi-center collaborations are needed to improve diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment protocols, and enhance patient outcomes [3]. This manuscript aims to review the clinical presentation, diagnostic workup, surgical management, and prognosis of parathyroid carcinoma, supplemented by a case series to illustrate these points.

2. Methods

We retrospectively reviewed three cases of parathyroid carcinoma treated at a tertiary referral hospital performed by a general surgeon with >30 years of endocrine surgery experience. We analyzed patient demographics, clinical presentation, imaging studies, surgical interventions, histopathological findings, and follow-up data. We emphasized intraoperative decisions, criteria for a biochemical cure, and long-term monitoring protocols.

2.1. Summary of key data points

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical presentation.

| Patient ID | Age | Gender | Initial Symptoms | Relevant Comorbidities | Initial Calcium (mg/dL) | Initial PTH (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 84 | Male | Osteoporosis, muscle/bone pain, kidney stones | Prostate cancer, bladder cancer, HTN, PAF, HLD, RA | 12.7 | 253 |

| Patient 2 | 77 | Male | Osteoporosis, history of kidney stones | Atrial fibrillation, bladder cancer, chronic heart failure, CAD, morbid obesity, pacemaker | 10.1 | 264.4 |

| Patient 3 | 61 | Female | Left neck mass, shortness of breath | ESRD on hemodialysis, HTN, type 2 diabetes, CAD, chronic anemia, thrombocytopenia | 12.6 | >2000 |

Table abbreviations: HTN (hypertension), PAF (paroxysmal atrial fibrillation), HLD (hyperlipidemia), RA (rheumatoid arthritis), CAD (coronary artery disease), ESRD (end stage renal disease).

Table 2.

Diagnostic approaches and imaging.

| Patient ID | Imaging modality | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | CT Parathyroid 4D | 3.3 cm mass inferior to the left thyroid lobe; suspicious for parathyroid adenoma |

| Sestamibi Scan | Persistent uptake in the left thyroid bed; possible small adenoma within the right thyroid | |

| Ultrasound | Multinodular thyroid with a large hypoechoic mass | |

| Patient 2 | Parathyroid Scintigraphy | Persistent delayed nodular radiotracer uptake along the deep margin of the right thyroid lobe |

| Ultrasound | N/A | |

| Patient 3 | CT Parathyroid 4D | 5 cm hypervascular mass in the left side of the neck anterior to the common carotid artery, suspicious for parathyroid adenoma |

| Ultrasound | 2.9 × 2.8 × 4.3 cm mass lateral to the left thyroid lobe | |

| FNA (pre-op) | FNA done to rule out other head and neck malignancy due to uncertainty of being parathyroid. Initial prior biopsy showed follicular neoplasm. FNA showed hypercellular parathyroid tissue. |

Table abbreviations: FNA (fine needle aspiration).

Table 3.

Surgical interventions and outcomes.

| Patient ID | Surgical procedure | Intraoperative findings | Post-surgical calcium (mg/dL) | Post-surgical PTH (pg/mL) | Follow-up outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Left superior parathyroidectomy | 3.7 cm parathyroid carcinoma, lymphovascular invasion | 10.1 | 180.9 | Persistent elevated PTH, ongoing monitoring |

| Patient 2 | Right superior parathyroidectomy | 3.55 cm parathyroid carcinoma | 8.0 | 58.5 | Stable, no recurrence |

| Patient 3 | Left thyroid lobectomy, isthmusectomy, and parathyroidectomy | 5 cm hypervascular parathyroid tumor invading anterior strap muscles | 8.9 | 15.8 | Non-adherence to follow-up, later expired due to stroke |

Table abbreviations: PTH (parathyroid hormone).

Table 4.

Histopathological findings.

| Patient ID | Histopathology | Immunohistochemical stains | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Parathyroid carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion | PTH, parafibromin, Ki-67 | Capsular and vascular invasion, low mitotic rate |

| Patient 2 | Parathyroid carcinoma with vascular invasion | PTH, parafibromin, Ki-67 | Fibrous bands, low mitotic rate, focal vascular invasion |

| Patient 3 | Parathyroid carcinoma with capsular and lymphovascular invasion | PTH, Ki-67, TTF1, galectin-3 | Chronic thyroiditis with oncocytic Hurthle cell changes and scattered calcifications. There is a cellular expansile nodule with occasional fibrous bands and capsular and lymphovascular invasion. Mitotic figures are not conspicuous in >50 high power fields. Low Ki-67 proliferation index |

Table abbreviations: PTH (parathyroid hormone), Ki-67 (Antigen Kiel 67), TFF1 (Trefoil Factor 1).

Table 5.

Follow-up.

| Patient ID | Follow-up and recurrence monitoring | Additional notes |

|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Persistent elevated PTH, ongoing monitoring, Ca normalized | Despite the normalization of calcium levels, the persistent elevation in PTH levels raises concerns about residual parathyroid carcinoma. Consideration is being given to further surgical intervention to remove any remaining parathyroid tissue that may be contributing to the elevated PTH levels, aiming for complete excision of the malignant tissue and reducing the risk of recurrence. A post-operative SPECT CT indicated a suspected right-sided parathyroid adenoma. The decision to proceed with further surgery, including potential exploration and removal of the left thyroid for suspected residual disease (despite no SPECT activity) and re-examination of the right parathyroid, is still pending patient consent. |

| Patient 2 | Stable with no recurrence, regular follow-ups | Following with no signs of recurrence |

| Patient 3 | No adherence to follow-up, later expired | Lost to longitudinal follow up, expired five years later due to CVA |

Table abbreviations: PTH (parathyroid hormone), CVA (cerebral vascular accident).

2.2. Comparative analysis of parathyroid carcinoma case series

2.2.1. Patient demographics and clinical presentation

The three cases in this series demonstrate the diverse clinical presentations of parathyroid carcinoma, showcasing the complexity of this rare endocrine malignancy (Table 1). Patient 1, an 84-year-old male, presented with osteoporosis, muscle, and bone pain, and a history of kidney stones. Patient 2, a 77-year-old male, exhibited similar symptoms, including osteoporosis and kidney stones, along with significant cardiac comorbidities. Patient 3, a 61-year-old female, presented with a prominent left neck mass and extensive comorbidities, including end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and diabetes, making her case particularly unusual as it involved parathyroid carcinoma in the context of tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

These cases illustrate the necessity of considering parathyroid carcinoma in patients with severe hypercalcemia and markedly elevated PTH levels, especially when accompanied by significant comorbid conditions. However, the presentation can vary, as demonstrated by Patient 2, who had normal calcium levels with inappropriately elevated PTH, indicating that not all cases present with the classic signs of hypercalcemia. This variability in presentation emphasizes the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and comprehensive diagnostic evaluation in suspected cases of parathyroid carcinoma.

2.2.2. Diagnostic and imaging procedures

Diagnostic workup for these patients included biochemical tests, imaging studies, and histopathological examination (Table 2).

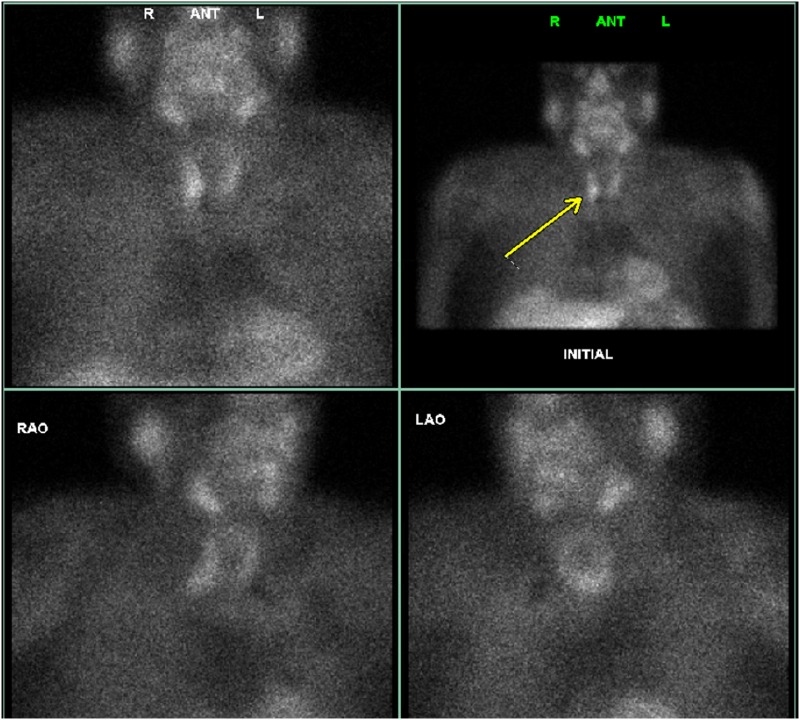

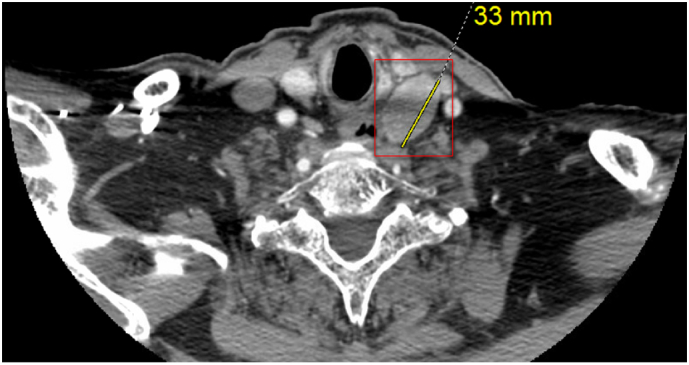

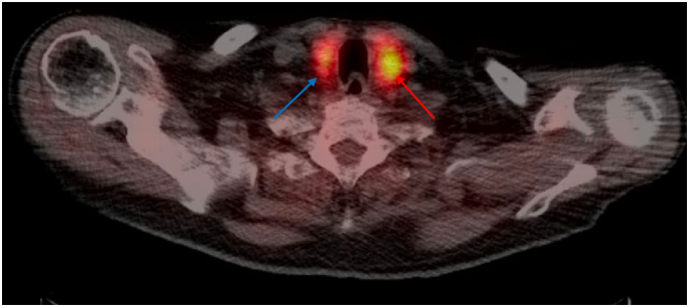

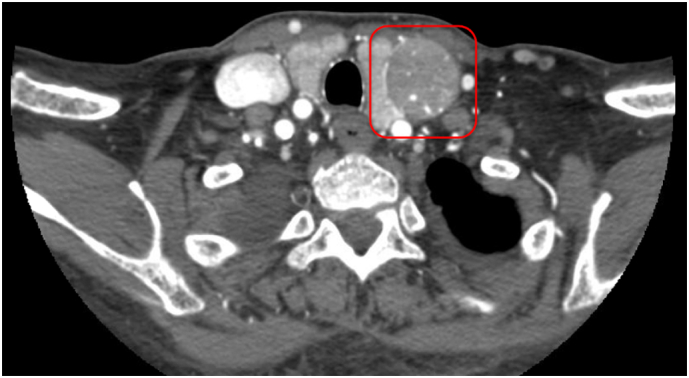

For Patient 1, imaging initially revealed a 3.3 cm mass suggestive of a parathyroid adenoma, not explicitly indicative of carcinoma (Fig. 1). NM Parathyroid Spect CT Sestamibi revealed a focal area of persistent uptake of the radiopharmaceutical within the left thyroid bed consistent with a probable thyroid adenoma (Fig. 2). Post-surgical examination confirmed the diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma. Patient 2's scintigraphy pointed to a right superior parathyroid adenoma, later confirmed as carcinoma with vascular invasion (Fig. 3). Patient 3 presented with imaging that showed a 5 cm hypervascular mass, initially suspected to be an adenoma but later identified as carcinoma with significant invasion (Fig. 4). The mass displays significant arterial and venous blood supply, indicating a hypervascular nature. However, it cannot be definitively identified as parathyroid or metastatic tissue based solely on the imaging characteristics.

Fig. 1.

CT Parathyroid 4D of Patient 1 reveals a 3.3 cm mass located inferior to the left thyroid lobe, showing a nonspecific enhancement pattern but suspicious for a parathyroid adenoma (marked by a red square). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

NM Parathyroid SPECT CT (Sestamibi) of Patient 1 shows a focal area of persistent uptake within the left thyroid bed, indicative of a probable thyroid adenoma (red arrow). Minimal persistent uptake in the right thyroid bed suggests a potential small adenoma (blue arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Parathyroid scintigraphy of Patient 2 demonstrates persistent delayed nodular radiotracer uptake along the deep margin of the right thyroid lobe, consistent with a parathyroid adenoma (yellow arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

CT soft tissue neck with contrast of Patient 3 demonstrates a 5 cm hypervascular mass located anterior to the common carotid artery and distinct from the left thyroid lobe (red box). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Ultrasound and 4D CT scans were essential in identifying the abnormal masses, with sestamibi scans providing further localization details. For Patient 1, a preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA) was conducted, which identified parathyroid tissue. This procedure was carried out due to the initial misdiagnosis of the mass as a thyroid nodule, leading to the decision to perform a biopsy. The use of FNA is generally avoided in suspected cases of parathyroid carcinoma to prevent potential seeding and the creation of diagnostic artifacts.

2.2.3. Surgical interventions and outcomes

Surgical management involved en bloc resection where feasible, aiming to remove the tumor and any involved surrounding tissues (Table 3).

Patient 1: The patient underwent a left superior parathyroidectomy, during which a 3.7 cm carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion was removed. Intraoperative monitoring showed a significant drop in PTH levels, from 299 to 93, indicating more than a 50 % decrease. Additionally, all four parathyroid glands were identified during the procedure, suggesting a thorough exploration was completed.

Despite these findings, postoperative PTH levels remained elevated, raising concerns about residual disease or ectopic parathyroid tissue. A subsequent SPECT CT scan revealed a suspected right-sided parathyroid adenoma. Although further surgery, including a potential en bloc resection, was considered to address the elevated PTH levels, it was not immediately pursued. This decision was influenced by the patient's reluctance to undergo additional procedures and the absence of clear localization of abnormal glands during the initial surgery.

Ongoing management focuses on monitoring PTH and calcium levels, with discussions about the possibility of future surgical intervention to ensure complete removal of any residual parathyroid tissue. This case emphasizes the need for comprehensive intraoperative assessment and the importance of continued follow-up in cases where biochemical markers do not fully normalize.

Patient 2: This patient was treated by right superior parathyroidectomy. The removal of a 3.55 cm carcinoma resulted in the normalization of calcium (8.0 mg/dL) and PTH (58.5 pg/mL) levels postoperatively. Regular follow-ups showed no recurrence, highlighting the effectiveness of thorough initial surgical intervention.

Patient 3: This patient required a left thyroid lobectomy with isthmusectomy and parathyroidectomy due to the invasive nature of the tumor. The patient achieved normalization of PTH levels (15.8 pg/mL) postoperatively but was lost to follow-up. Unfortunately, the patient expired five years later due to a stroke.

2.2.4. Histopathological findings

Histopathological evaluation confirmed parathyroid carcinoma in all cases, characterized by key features such as capsular and vascular invasion (Table 4).

Patient 1: Histopathology demonstrated capsular and vascular invasion with a low mitotic rate.

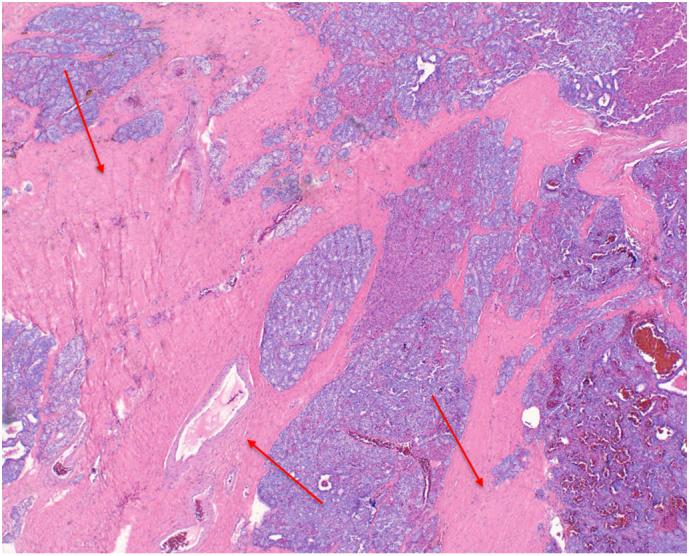

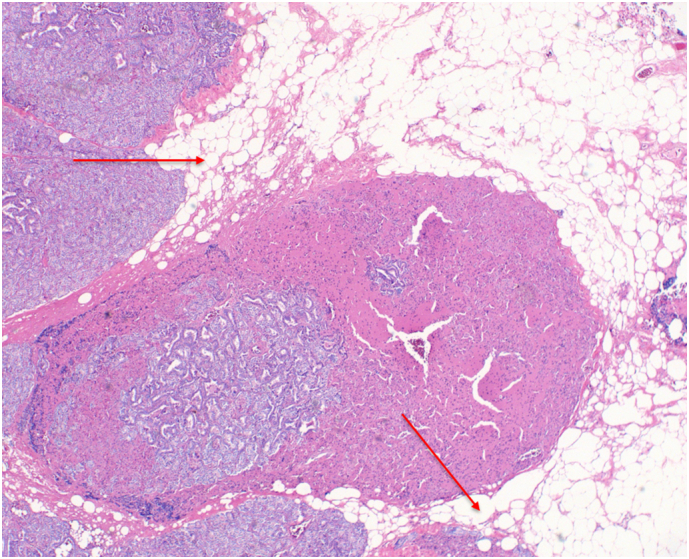

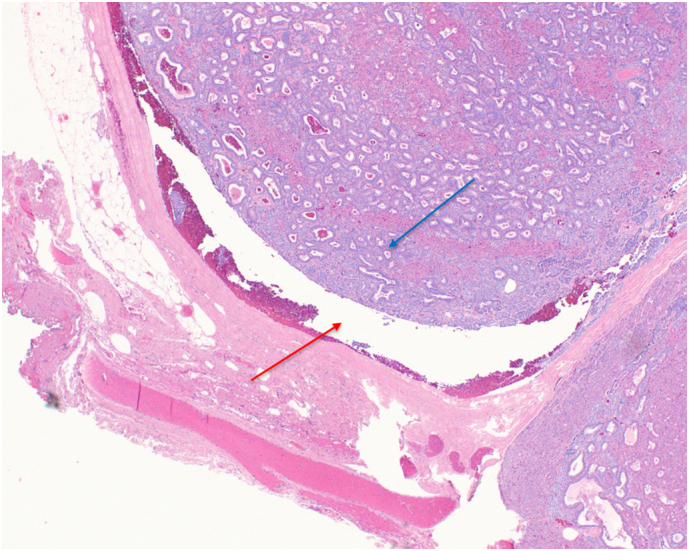

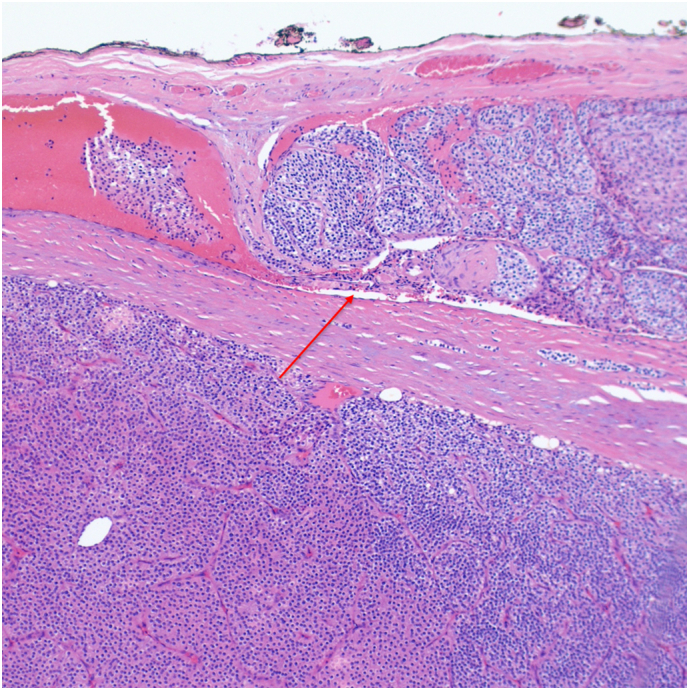

Patient 2: Histopathology showed fibrous bands (Fig. 5) and focal vascular invasion with fat infiltration (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

Fig. 5.

Patient 2 H&E stained pathology slide at 10× magnification demonstrating fibrous bands (red arrows). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 6.

Patient 2 H&E stained pathology slide at 10× magnification showing fat infiltration (red arrows). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

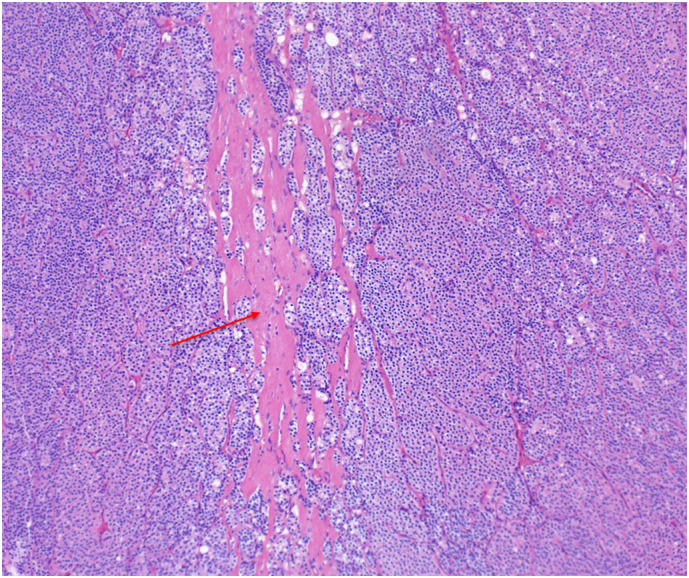

Fig. 7.

Patient 2 H&E stained pathology slide at 10× magnification shows tumor (blue arrow) vascular invasion of a blood vessel (red arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

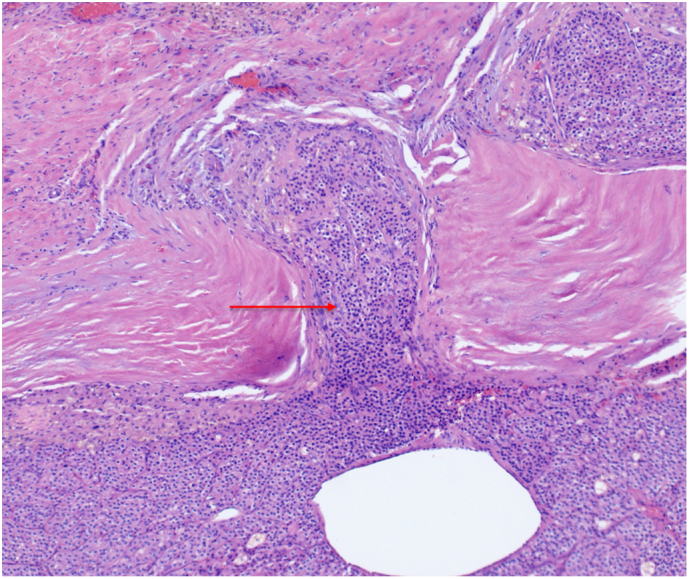

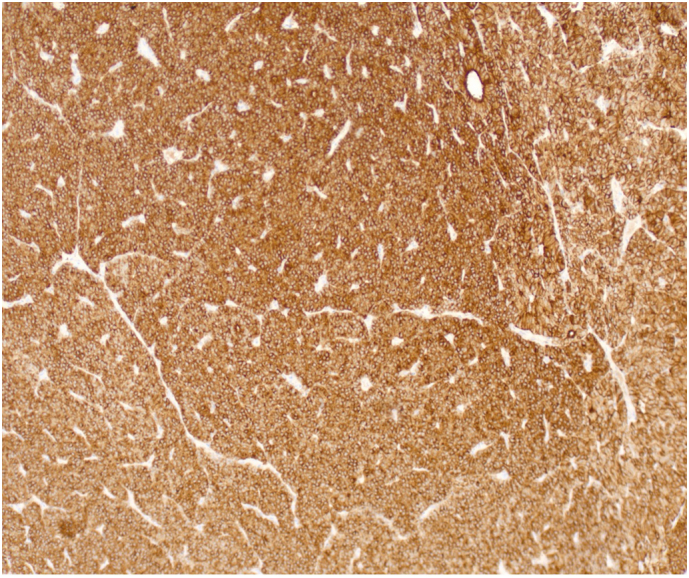

Patient 3: Histopathology revealed capsular and lymphovascular invasion with fibrous bands and a low Ki-67 proliferation index (Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10). Immunohistochemical staining was consistent across cases, confirming parathyroid tissue through positive PTH and parafibromin staining as demonstrated with Patient 3 in Fig. 11.

Fig. 8.

Patient 3 H&E stained pathology slide at 10× magnification demonstrating capsular invasion (red arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 9.

Patient 3 H&E stained pathology slide at 10× magnification showing vascular invasion of a blood vessel (red arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 10.

Patient 3 H&E stained pathology slide at 10× magnification demonstrating fibrous bands (red arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 11.

Patient 3 immunohistochemical stained pathology slide at 10× magnification demonstrating positive PTH staining.

3. Discussion

Parathyroid carcinoma is a rare endocrine malignancy, constituting <1 % of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) cases [6]. The complexity of diagnosing and managing this condition requires careful clinical assessment, comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, and precise surgical treatment [4,16]. The clinical presentation of parathyroid carcinoma often includes severe hypercalcemia, elevated PTH levels, and symptoms such as osteoporosis, nephrolithiasis, and neuromuscular disturbances [6]. However, not all patients exhibit these symptoms uniformly. For example, in this series, Patient 2 presented with relatively mild hypercalcemia (10.1 mg/dL) compared to the more typical presentation seen in Patients 1 and 3. This variability necessitates a high index of suspicion for accurate diagnosis. Initial diagnostic steps typically involve biochemical tests to assess calcium and PTH levels [10]. Subsequent imaging studies, such as ultrasound, 4D CT scans, and sestamibi scans, are crucial for tumor localization [17,18].

In comparison to similar case reports and studies, our findings align with the literature that parathyroid carcinoma often presents with severe hypercalcemia and elevated PTH levels, although these parameters can vary. In one review of 43 cases of parathyroid carcinoma, Wynne et al. reported that a majority of patients presented with hypercalcemia >14 mg/dL, with only a minority showing moderate hypercalcemia between 11 and 13 mg/dL, as seen in our second patient [2]. This suggests that while extreme hypercalcemia is common, moderate levels, such as the 10.1 mg/dL seen in our patient, do not rule out malignancy.

Similarly, Wei and Harari noted that parathyroid carcinomas tend to be larger and more invasive at diagnosis, often requiring en-bloc resection to avoid recurrence [5]. Our findings echo this, particularly in the third patient, where the carcinoma invaded the anterior strap muscles and necessitated extensive surgery.

In this series, histopathological examination post-surgery confirmed the diagnosis of carcinoma in all cases, highlighting key features like capsular and vascular invasion. Preoperative biopsies, generally avoided due to seeding and the risk of diagnostic artifacts, were performed in Patients 1 and 3. This approach should be used cautiously, especially when parathyroid tissue is suspected [19].

Surgical treatment is the primary approach for managing parathyroid carcinoma, with the aim of complete tumor removal [1,20]. En-bloc resection is often necessary to minimize recurrence risk [11]. Intraoperative PTH monitoring is crucial to assess the completeness of tumor excision [13,21]. The decision to perform an en-bloc resection requires significant expertise, as many recurrences occur due to inadequate initial surgery where the parathyroid capsule may be inadvertently violated [11,22]. The “Miami Criterion,” which defines biochemical cure as a >50 % decrease in PTH levels from the highest pre-incision or pre-excision level within 10 min post-resection, serves as a standard intraoperative guideline [13,21].

Complications following parathyroidectomy for carcinoma are well-documented, and it is crucial to monitor patients for recurrence, persistent hypercalcemia, and PTH elevation. In our first case, despite initial successful resection, the persistent elevation in PTH suggests possible ectopic parathyroid tissue or incomplete resection. Such complications are not uncommon in parathyroid carcinoma, and persistent hypercalcemia post-surgery can result in nephrolithiasis, bone disease, and neuromuscular disturbances if not adequately managed.

Further, there is the risk of damage to surrounding structures during surgery. Damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve is a known complication during parathyroid surgery, particularly in cases where the carcinoma is closely associated with the thyroid gland or surrounding tissues. While no vocal cord paralysis occurred in our patients, close monitoring for this complication is advised, especially in cases requiring extensive dissection.

Long-term monitoring remains essential, as recurrences are frequent. Chow et al. reported recurrence rates as high as 50 % within five years, particularly in cases where en bloc resection was not achieved [3]. This is consistent with the outcome of our first patient, where ongoing monitoring is necessary due to persistent PTH elevation.

Given its propensity for recurrence, long-term follow-up is critical for managing parathyroid carcinoma [11,23] (Table 5). Persistent elevated PTH levels in Patient 1 necessitated continued monitoring and potential additional surgical intervention. Patient 2 remained stable with no recurrence, demonstrating the effectiveness of thorough initial surgery and diligent follow-up. Patient 3's case involves non-adherence to follow-up. Standard follow-up protocols include regularly monitoring calcium and PTH levels, typically every 3 to 6 months initially, then annually [11,22]. Patients frequently experience multiple recurrences over their lifetime if not adequately treated initially, with mortality often resulting from complications related to hypercalcemia rather than the cancer itself [16]. Current treatments for recurrent disease focus on surgical re-excision and medical management of hypercalcemia, using agents like bisphosphonates, denosumab, and cinacalcet [1,10]. Prognostic factors for parathyroid carcinoma include tumor size, extent of invasion, and initial PTH levels [16,22]. Larger tumors with significant capsular and vascular invasion are linked to poorer outcomes and higher recurrence rates [21]. Patient compliance with long-term follow-up is essential for managing this chronic condition, as recurrences are common and often life-threatening due to hypercalcemia-related complications [1,3].

4. Conclusion

Parathyroid carcinoma is challenging to diagnose and treat due to its resemblance to benign conditions and potential for severe hypercalcemia and elevated PTH levels. This case series highlights the importance of a high index of suspicion, thorough diagnostic workup, and meticulous surgical intervention, particularly en bloc resection, to minimize recurrence. Intraoperative PTH monitoring is crucial for ensuring complete tumor removal. The disease's indolent nature requires rigorous, long-term follow-up, as it is resistant to conventional radio and chemotherapy. Emerging targeted molecular and immunotherapies offer promising future treatments. A multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinologists, surgeons, oncologists, and pathologists is essential for optimal patient outcomes. Preoperative biopsy of parathyroid glands should generally be avoided.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

This manuscript has been reported in line with the PROCESS criteria [24].

Ethical approval

Exemption from ethical approval has been given for this case series. Case series with 3 or less patients do not require institutional review board (IRB) approval at our institution.

Sources of funding

There are no sources of funding for this work.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nathaniel Grabill, MD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration. Mena Louis, DO: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft. Nikita Machado, MD: Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision. Pierpont Brown III, MD: Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision. Ezra Ellis, MD: Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Investigation. Sumi So, MD: Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Investigation.

Guarantor

Nathaniel Grabill, MD (corresponding author)

Registration of research studies

NA

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that there are no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence (bias) this work.

Contributor Information

Nathaniel Grabill, Email: Nathaniel.grabill@nghs.com.

Nikita Machado, Email: nikita.machado@nghs.com.

Pierpont Brown, III, Email: pierpont.browniii@nghs.com.

Ezra Ellis, Email: ezra.ellis@nghs.com.

Sumi So, Email: sumi.so@nghs.com.

References

- 1.DeLellis R.A. Parathyroid carcinoma: an overview. Adv Anat Pathol. Mar 2005;12(2):53–61. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000151319.42376.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wynne A.G., van Heerden J., Carney J.A., Fitzpatrick L.A. Parathyroid carcinoma: clinical and pathologic features in 43 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) Jul 1992;71(4):197–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow E., Tsang R.W., Brierley J.D., Filice S. Parathyroid carcinoma--the Princess Margaret Hospital experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41(3):569–572. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00098-4. Jun 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apaydın T., Yavuz D.G. Seven cases of parathyroid carcinoma and review of the literature. Hormones (Athens) Mar 2021;20(1):189–195. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00220-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei C.H., Harari A. Parathyroid carcinoma: update and guidelines for management. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. Mar 2012;13(1):11–23. doi: 10.1007/s11864-011-0171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd C., Kashyap S., Kwartowitz G. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2023. Parathyroid cancer. Jul 24. 2024 Jan–. PMID: 30085580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C.A., Gaz R.D. Natural history of parathyroid carcinoma. Diagnosis, treatment, and results. Am. J. Surg. Apr 1985;149(4):522–527. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(85)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam M.A., Untch B.R., Olson J.A., Jr. Parathyroid carcinoma: current understanding and new insights into gene expression and intraoperative parathyroid hormone kinetics. Oncologist. 2010;15(1):61–72. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi C., Lu N., Yong Y.J., Chu H.D., Xia A.J. Parathyroid carcinoma: three case reports. World J. Clin. Cases. 2023;11(25):5934–5940. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i25.5934. Sep 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan K., Mete Ö. Parathyroid carcinoma: diagnosis and clinical implications. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2015;31(Suppl. 1):80–97. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2015.01316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingeret A.L. Contemporary evaluation and management of parathyroid carcinoma. JCO Oncol Pract. Jan 2021;17(1):17–21. doi: 10.1200/jop.19.00540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salcuni A.S., Cetani F., Guarnieri V., et al. Parathyroid carcinoma. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. Dec 2018;32(6):877–889. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carneiro D.M., Solorzano C.C., Nader M.C., Ramirez M., Irvin G.L., 3rd. Comparison of intraoperative iPTH assay (QPTH) criteria in guiding parathyroidectomy: which criterion is the most accurate? Surgery. Dec 2003;134(6):973–979. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.06.001. discussion 979-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roser P., Leca B.M., Coelho C., et al. Diagnosis and management of parathyroid carcinoma: a state-of-the-art review. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2023;30(4) doi: 10.1530/erc-22-0287. Apr 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigo J.P., Hernandez-Prera J.C., Randolph G.W., et al. Parathyroid cancer: an update. Cancer Treat. Rev. Jun 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cetani F., Pardi E., Torregrossa L., et al. Approach to the patient with parathyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023;109(1):256–268. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad455. Dec 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodgers S.E., Perrier N.D. Parathyroid carcinoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. Jan 2006;18(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000198019.53606.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obara T., Fujimoto Y. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with parathyroid carcinoma: an update and review. World J Surg. Nov–Dec 1991;15(6):738–744. doi: 10.1007/bf01665308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira C. Role of intraoperative parathyroid hormone in guiding parathyroidectomy. Acta Biomed. 2023;94(2):e2023040. doi: 10.23750/abm.v94i2.13998. Apr 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin K.E., Galante M., Clark O.H. Parathyroid carcinoma versus parathyroid adenoma in patients with profound hypercalcemia. Surgery. Jun 1987;101(6):649–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leiker A.J., Yen T.W., Eastwood D.C., et al. Factors that influence parathyroid hormone half-life: determining if new intraoperative criteria are needed. JAMA Surg. Jul 2013;148(7):602–606. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cetani F., Pardi E., Marcocci C. Parathyroid carcinoma. Front. Horm. Res. 2019;51:63–76. doi: 10.1159/000491039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kebebew E. Parathyroid carcinoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. Aug 2001;2(4):347–354. doi: 10.1007/s11864-001-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathew G., Agha R.A., Sohrabi C., Franchi T., Nicola M., Kerwan A., Agha R for the PROCESS Group Preferred reporting of case series in surgery (PROCESS) 2023 guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2023 doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000940. (article in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]