Abstract

Background

Alopecia areata (AA) is characterized by hair loss on the scalp and body, significantly impacting patients’ quality of life based on its severity.

Objective

This study aims to identify crucial factors influencing the perception of severe AA from the patients’ viewpoint.

Methods

A web-based survey was conducted among AA patients attending dermatology departments at 21 university hospitals in Korea. The survey comprised 17 criteria, exploring both clinical characteristics of AA patients and subjective determinants of disease severity.

Results

A total of 791 AA patients and their caregivers participated in the survey. Approximately 30% of respondents developed AA during childhood, with 43.5% experiencing chronic courses lasting over 3 years. Half of the participants exhibited more than 20% scalp hair loss, and 42% reported additional hair loss on other body parts, such as eyelashes and nose hair. Most respondents agreed that patients with ≥20% scalp hair loss should be categorized as having severe AA. They also identified longer disease duration, involvement of non-scalp body hair, treatment refractoriness, and social or mental impairment requiring medical intervention as factors indicating increased disease severity.

Conclusion

This survey underscores the significant impact of AA on patients’ quality of life and highlights existing unmet needs in current treatment modalities.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, patients, Needs Assessment, Surveys and Questionnaires, Severity of Illness Index

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is an unpredictable autoimmune disease caused by the collapse of hair follicle immune privilege. It usually presents as patchy hair loss, but it can lead to total body hair loss in severe cases. While most patients with 1–2 hairless patches heal naturally, treating severe patients with extensive hair loss is difficult, and even after treatment, it often shows a chronic refractory course1,2. The conventional treatment of AA includes topical or intralesional corticosteroids, contact immunotherapy with diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP), systemic immunosuppressants, and steroid pulse therapy3,4,5. However, these treatments are not consistently effective, and there is limited evidence supporting their effectiveness in severe AA. Patient satisfaction with treatment is also low6. Recently, new drugs such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors have emerged as effective treatments for moderate to severe AA, but access to these drugs remains limited due to their high cost7,8,9.

Significant hair loss, particularly in the eyebrows and eyelashes, can profoundly influence a patient’s appearance, impacting social interactions and leading to serious psychological effects10,11,12. Studies have shown that patients with AA experience a 30% higher level of daily life stress compared to the general population, and the prevalence of lifelong psychiatric disorders in AA patients ranges from 66% to 74%. Additionally, the lifetime prevalence of depression in AA patients is reported to be between 38% and 39%, with general anxiety disorder prevalence ranging from 39% to 62%13. Furthermore, research indicates that AA patients have a 6.28-fold higher risk of suicidal ideation than the general population14.

In cases where scalp, eyebrow, or nose hairs are absent, patients become more susceptible to external harmful stimuli such as ultraviolet rays, sweat, dust, and infectious organisms. This vulnerability can lead to persistent physical discomfort and increase the risk of comorbidities such as conjunctivitis and upper respiratory tract infections15,16,17.

As AA is a chronic inflammatory disorder, individuals with this condition face an elevated risk of developing other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid disease. Patients diagnosed with AA have a 1.86-fold higher risk of developing autoimmune diseases within three years compared to individuals without AA18.

Given these considerations, it is imperative to establish clear criteria for severe AA, as it can significantly impact patients’ lives and requires appropriate management19. However, currently, individuals with severe AA often receive similar treatment approaches as those with only one or two alopecic patches. Therefore, raising awareness about the disease is crucial to reducing the burden on patients and ensuring they receive the supportive treatment environment they need.

The Korean Hair Research Society (KHRS) recently proposed diagnostic criteria for severe AA. According to KHRS guidelines, hair loss exceeding 50% of the scalp area qualifies as severe AA. Additionally, severe AA may be diagnosed if a patient experiences significant loss of body hair, such as eyebrows, along with a marked decline in quality of life, active hair loss, or an inadequate response to treatment, even if the scalp area affected ranges from 20% to 50% (unpublished).

Recognizing the importance of considering patients' psychosocial burden and quality of life when assessing AA severity, this study aimed to identify crucial factors determining severe AA from the patients’ perspective. By surveying various parameters related to disease severity, including age of onset, disease duration, persistence of alopecic patches, involvement of body hair, social impairment, mental health conditions, and treatment response, the study sought to ascertain the significance of each factor in determining severity and the threshold at which each item should be considered indicative of severe AA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

All individuals diagnosed with AA by a dermatologist and who sought care at the dermatology departments of 21 university hospitals in Korea from June 2023 to November 2023 were eligible for inclusion in this study. There were no exclusion criteria based on the extent of scalp hair loss or the types of treatments received.

Study design

This study employed a cross-sectional design, utilizing a web-based survey method. Patients who provided informed consent were provided with a QR code at the outpatient clinics of respective centers. Upon scanning the QR code, participants were redirected to the web survey questionnaire. The survey was designed to be completed within twenty minutes. For participants under the age of nineteen, the survey was completed by their legal guardians. The questionnaire consisted of seventeen questions covering four main areas: patient demographics, disease characteristics, treatment response, and factors influencing disease severity. Further details regarding the survey contents are outlined in Supplementary Table 1.

Ehitcs statement

The study protocol received approval from the institutional review board of Eunpyeong St. Mary’s Hospital (IRB No. PC23QCDI0076) and all other participating institutes before the commencement of participant recruitment.

RESULTS

Patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics

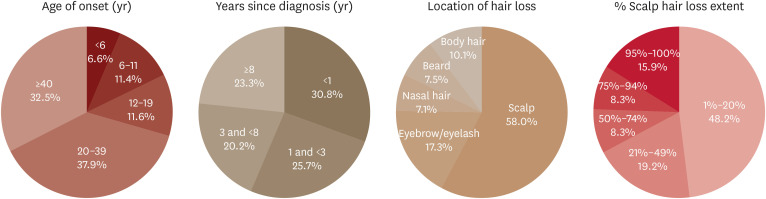

A total of 791 patients completed the survey, with the majority of responses (684, 86.5%) provided by the patients themselves, while the remainder (107, 13.5%) were completed by their legal representatives. Table 1 and Fig. 1 provide an overview of the demographics and clinical characteristics of the AA patients.

Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Variables | Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient demographics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 325 (41.5) | ||

| Female | 463 (58.5) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD | 38.05±14.83 | ||

| Province (city) of residence | |||

| Seoul | 226 (28.6) | ||

| Gyeonggi | 238 (30.1) | ||

| Chungcheong-do | 98 (12.4) | ||

| Gyeongsang-do | 96 (12.1) | ||

| Jeolla-do | 98 (12.4) | ||

| Others | 35 (4.4) | ||

| Level of education | |||

| Elementary school | 16 (2.0) | ||

| Middle school | 22 (2.8) | ||

| High school | 206 (26.0) | ||

| College or university | 477 (60.3) | ||

| Others | 70 (8.8) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age of onset (yr) | |||

| <6 | 52 (6.6) | ||

| 6–11 | 90 (11.4) | ||

| 12–19 | 92 (11.6) | ||

| 20–39 | 300 (37.9) | ||

| ≥40 | 257 (32.5) | ||

| Years since diagnosis (yr) | |||

| <1 | 244 (30.8) | ||

| 1 and <3 | 203 (25.7) | ||

| 3 and <8 | 160 (20.2) | ||

| ≥8 | 184 (23.3) | ||

| Location of hair loss | |||

| Scalp | 786 (58.0) | ||

| Eyebrow/eyelash | 235 (17.3) | ||

| Nasal hair | 96 (7.1) | ||

| Beard | 101 (7.5) | ||

| Body hair | 137 (10.1) | ||

| % Scalp hair loss extent | |||

| 1%–20% | 381 (48.2) | ||

| 21%–49% | 152 (19.2) | ||

| 50%–74% | 66 (8.3) | ||

| 75%–94% | 66 (8.3) | ||

| 95%–100% | 126 (15.9) | ||

Values are presented as number (%).

Fig. 1. Clinical characteristics.

Among the 791 participants, 325 (41.5%) were male, and 463 (58.3%) were female. The onset of AA for most participants (557/791, 70.4%) occurred in adulthood (20 years or older). The remaining 29.6% of participants (234/791) experienced pediatric or adolescent onset of AA, with 6.6% (52/791) and 11.4% (90/791) being diagnosed under the age of 6 and 12 years old, respectively. Regarding the duration of hair loss, 23.3% (184/791) of patients had a chronic course, being diagnosed with AA for 8 years or longer.

In terms of the location of hair loss, 42.0% of participants experienced hair loss beyond the scalp area. The most common locations of hair loss other than the scalp were the eyelash/eyebrow region, body hair, beard, and nasal hair, accounting for 58.0%, 17.3%, 7.1%, and 7.5%, respectively. Approximately half of the participants (381/791, 48.2%) had 1-20% scalp hair loss. Notably, patients with 95-100% scalp hair loss represented a significant proportion, accounting for 15.9% (126/791) of the total AA patients.

Patients’ perception of criteria for poor treatment response

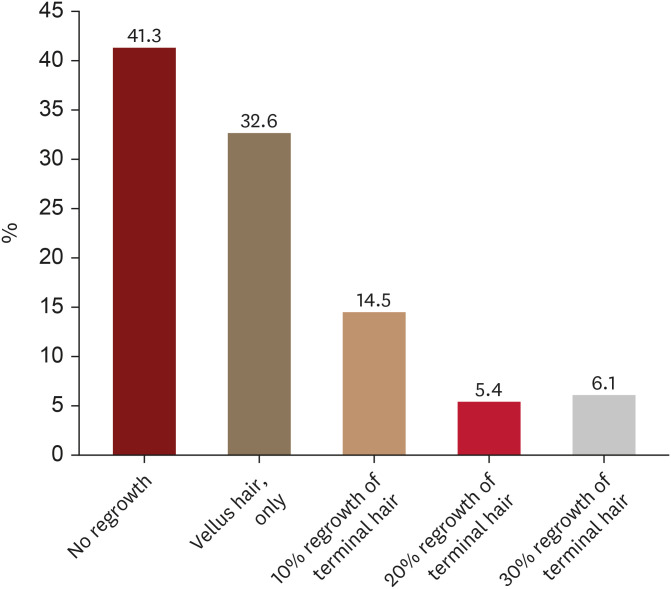

When patients were queried about their definition of inadequate response at 6 months from the initiation of treatment, a substantial portion (41.3%, 327/791) cited ‘no hair regrowth.’ Additionally, 32.6% (258/791) deemed the presence of only vellus hair growth as indicative of a poor response (Fig. 2). Notably, 6.1% (48/791) of patients still considered the response inadequate even when achieving 30% terminal hair regrowth.

Fig. 2. Amount of scalp hair regrowth that alopecia areata patients consider as poor response after 6 months of treatment.

Patient-reported factors determining disease severity

1) Extent of scalp hair loss and duration of hair loss patch

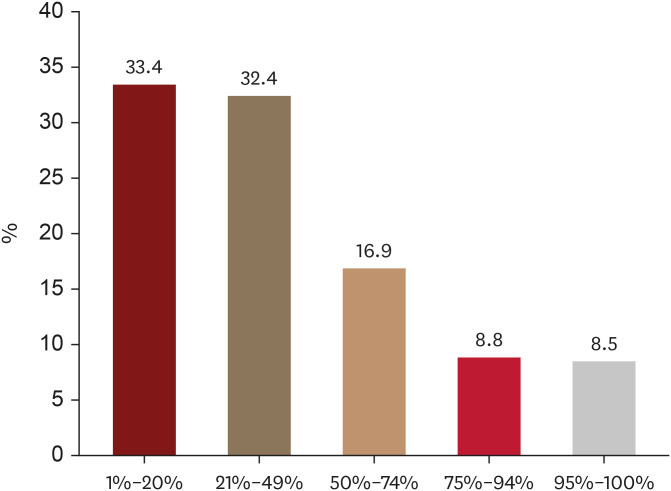

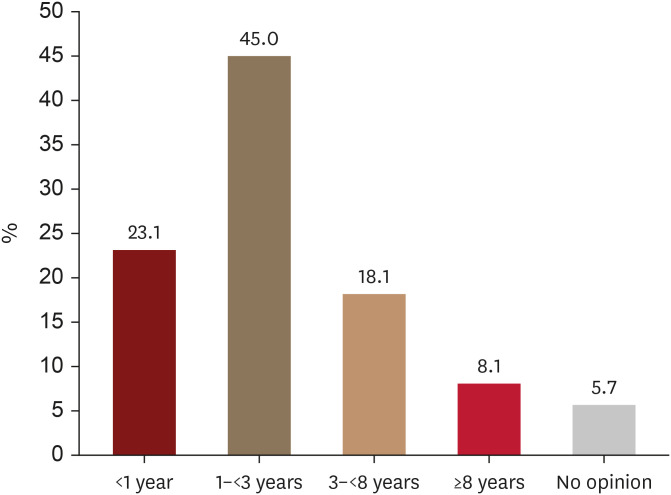

Regarding the extent of scalp hair loss, 65.8% of patients (520/791) considered AA as severe even when less than 50% scalp hair loss was present (Fig. 3). Moreover, the majority of patients (68.1%, 539/791) would still perceive AA as severe when the hair loss patch lasted less than 3 years (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Extent of scalp hair loss (%) that alopecia areata patients consider severe.

Fig. 4. Duration of hair loss patch (years) that alopecia areata patients consider severe.

2) Location of hair loss patches

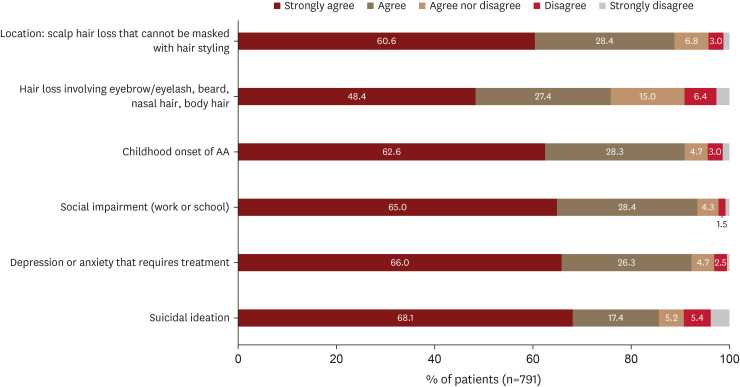

Concerning factors related to disease characteristics, 60.6% (479/791) and 48.4% (383/791) of patients strongly agreed that AA severity should be heightened when scalp hair loss occurs in an area where it cannot be masked with hair styling, or in body locations other than the scalp, such as the eyebrow/eyelash, beard, nasal hair, or body hair, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Other patient-reported factors associated with AA severity and their level of agreement.

AA: alopecia areata.

3) Onset age of disease

In terms of the age of disease onset, 62.6% (495/791) of patients strongly agreed that AA severity should be increased if the onset of AA is in childhood.

4) Psychosocial factors determining AA severity

The majority of AA patients agreed to increase severity if there is psychosocial impairment. Sixty-five percent (514/791) of patients strongly agreed that AA severity should be elevated if social impairment affects work or school life. Additionally, 66.0% (522/791) and 68.1% (539/791) of patients strongly agreed that AA severity should be increased if there is depression or anxiety requiring treatment or suicidal ideation, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of AA in Korea has exhibited a consistent upward trend over the past decade, with 179,388 patients treated in 2022. Individuals aged in their 20s to 50s, actively engaged in social activities, comprised 80% of all patients20,21. Similarly, the majority of participants in this survey were socially active, reflecting the demographic profile of AA patients in Korea. All 791 participants in this study were outpatients of university hospitals nationwide, suggesting a likelihood of recruiting relatively severe cases. Supporting this, 29.6% of all patients presented with onset during childhood and adolescence, with 6.6% being under the age of 6. Most patients regarded hair loss occurring during childhood onset as indicative of severe AA; indeed, AA in children, especially those under the age of 6, often showed a chronic course22,23.

The prevalence of chronic episodes lasting more than 3 years was 43.5%, with 23.3% of participants experiencing hair loss for over 8 years. Regarding the assessment of disease severity based on disease duration, 23.1% and 45.0% of patients agreed that severity should be increased even when the hair loss duration is less than a year or 3 years, respectively.

Interestingly, differences in viewpoints emerged between patients and physicians regarding severity assessed by the extent of scalp hair loss. This study reveals that most patients perceive AA as severe even when less than 50% of the scalp area is affected, which contrasts with expert consensus in several countries, including Korea. Expert consensus in several countries, including Korea (unpublished), Australia, Italy, and Brazil, stipulates that severe AA entails involvement of more than 50% of the scalp area. However, the Japanese guideline proposes alopecic patches exceeding 25% of the scalp area as indicative of severe AA24,25,26,27.

The prevalence of hair loss in areas such as eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair among patients with AA was not well known. However, this study reveals that 42.0% of participants experience some form of body hair loss. Most patients with AA agreed that severity should be heightened, even if the area of scalp hair loss does not exceed 50%, in cases where other body hairs besides the scalp are affected.

Noticeable amount of hair loss can profoundly impact self-esteem, comparable to the effects of body deformities and disabilities28. Patients may experience avoidance of interpersonal relationships, depression, or even suicidal thoughts or attempts29. This study revealed a high rate (85.5%) of strong to moderate agreement that suicidal ideation in AA patients should be considered indicative of severe AA. Correspondingly, 92.3% and 93.4% of participants agreed that upstaging should be considered if they require treatment for mental illnesses due to their hair loss or experience social impairment, respectively.

Recognizing the significance of hair loss in eyebrows and eyelashes, tools such as the Bringham eyebrow scale have been developed and adopted in clinical practice and diagnostic guidelines in several countries30,31,32.

According to the KHRS guidelines for AA treatment (2022), which reflect the latest treatment options, oral JAK inhibitors, conventional systemic immunosuppressants, contact immunotherapy (DPCP), or wigs are recommended as first-line treatments for patients with a Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of >50, indicating severe AA. Subsequently, the decision to maintain the first-line treatment or switch to another treatment is made based on the treatment response33. While it is recognized that conventional AA treatments often yield unsatisfactory results, AA patients tend to have high expectations. Although physicians commonly regard the emergence of newly growing vellus hairs as a treatment response, 32.6% of patients indicated that if only vellus hairs grew after six months of treatment, they would consider alternative treatment options due to perceived inadequate response. Additionally, even if terminal hair regrowth is evident in 30% of hairless patches, 6.1% of patients believed that the treatment response was still insufficient and that alternative treatment options should be explored.

This study was exclusively conducted on patients visiting university hospitals, potentially introducing a selection bias that may not fully represent all AA patients in Korea. However, the significance of this study lies in its evaluation based on the real-life experiences of AA patients and their caregivers. It is the first study to investigate the factors determining AA severity from the perspectives of patients and their caregivers on a national scale. The findings reveal that a significant portion of AA patients experience onset during childhood and endure chronic courses. Many participants exhibit more than 20% scalp hair loss and suffer from hair loss in other body parts such as eyelashes and nose hair. The majority of participants believe that any involvement of body hair, treatment resistance, social impairment, or depression and anxiety warranting medical intervention should be considered factors contributing to AA severity. These results are expected to enhance awareness about severe AA, which significantly impacts quality of life, and prompt institutional support for developing a comprehensive severity assessment tool encompassing various aspects of AA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We appreciate the active participation of council members of the KHRS, 791 of survey participants.

Footnotes

FUNDING SOURCE: This work was supported by the Korean Hair Research Society (KHRS).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Survey criteria

References

- 1.Smith A, Trüeb RM, Theiler M, Hauser V, Weibel L. High relapse rates despite early intervention with intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy for severe childhood alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:481–487. doi: 10.1111/pde.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strazzulla LC, Wang EH, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang KS, Mesinkovska NA, Piliang MP, Bergfeld WF. Clinical efficacy of diphenylcyclopropenone in alopecia areata: retrospective data analysis of 50 patients. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2015;17:50–55. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2015.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowaczyk J, Makowska K, Rakowska A, Sikora M, Rudnicka L. Cyclosporine with and without systemic corticosteroids in treatment of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2020;10:387–399. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phan K, Ramachandran V, Sebaratnam DF. Methotrexate for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:120–127.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strazzulla LC, Wang EH, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. Alopecia areata: an appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan D, Fan H, Chen M, Xia L, Wang S, Dong W, et al. The efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:950450. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.950450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, Zlotogorski A, Ko J, Mesinkovska NA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1687–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King B, Zhang X, Harcha WG, Szepietowski JC, Shapiro J, Lynde C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b-3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401:1518–1529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pazhoohi F, Kingstone A. Eyelash length attractiveness across ethnicities. Sci Rep. 2023;13:14849. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-41739-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadr J, Jarudi I, Sinha P. The role of eyebrows in face recognition. Perception. 2003;32:285–293. doi: 10.1068/p5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, Agbai ON, Kiuru M. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397–403. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S53985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang LH, Ma SH, Tai YH, Dai YX, Chang YT, Chen TJ, et al. Increased risk of suicide attempt in patients with alopecia areata: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Dermatology. 2023;239:712–719. doi: 10.1159/000530076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen JV. The biology, structure, and function of eyebrow hair. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(Suppl):s12–s16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Starace M, Cedirian S, Alessandrini AM, Bruni F, Quadrelli F, Melo DF, et al. Impact and management of loss of eyebrows and eyelashes. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023;13:1243–1253. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00925-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozturk AB, Damadoglu E, Karakaya G, Kalyoncu AF. Does nasal hair (vibrissae) density affect the risk of developing asthma in patients with seasonal rhinitis? Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;156:75–80. doi: 10.1159/000321912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S, Lee H, Lee CH, Lee WS. Comorbidities in alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:466–477.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:806–812.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Alopecia areata [Internet] 2023. [cited 2023 March 31]. Available from: https://health.kdca.go.kr/healthinfo/biz/health/gnrlzHealthinfo/gnrlzHealthinfo/gnrlzHealthInfoView.do?cntnts_sn=5690.

- 21.HIRA Big Data Open Portal. Alopecia areata [Internet] 2023. [cited 2023 March 31]. Available from: https://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olap3thDsInfo.do.

- 22.De Waard-van der Spek FB, Oranje AP, De Raeymaecker DM, Peereboom-Wynia JD. Juvenile versus maturity-onset alopecia areata--a comparative retrospective clinical study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:429–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb02604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tosti A, Bellavista S, Iorizzo M. Alopecia areata: a long term follow-up study of 191 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cranwell WC, Lai VW, Photiou L, Meah N, Wall D, Rathnayake D, et al. Treatment of alopecia areata: an Australian expert consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:163–170. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossi A, Muscianese M, Piraccini BM, Starace M, Carlesimo M, Mandel VD, et al. Italian guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of alopecia areata. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2019;154:609–623. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.19.06458-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos PM, Anzai A, Duque-Estrada B, Melo DF, Sternberg F, Santos LD, et al. Consensus on the treatment of alopecia areata - Brazilian Society of Dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95(Suppl 1):39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuboi R, Itami S, Manabe S, Amo Y, Ito T, Inui S, et al. Japanese Dermatological Association Alopecia areata clinical practice guidelines. Jpn J Dermatol. 2017;127:2741–2762. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, Ko J, Cassella J. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20:S62–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dalen M, Muller KS, Kasperkovitz-Oosterloo JM, Okkerse JM, Pasmans SG. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in children and adults with alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:1054898. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1054898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manjaly P, Li SJ, Tkachenko E, Ko JM, Liu KJ, Scott DA, et al. Development and validation of the Brigham Eyelash Tool for Alopecia (BELA): a measure of eyelash alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:271–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tkachenko E, Huang KP, Ko JM, Liu KJ, Scott DA, Senna MM, et al. Brigham eyebrow tool for alopecia: a reliable assessment of eyebrow alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20:S41–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyrwich KW, Kitchen H, Knight S, Aldhouse NV, Macey J, Nunes FP, et al. Development of clinician-reported outcome (ClinRO) and patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures for eyebrow, eyelash and nail assessment in alopecia areata. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:725–732. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00545-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park H, Kim JE, Choi JW, Kim DY, Jang YH, Lee Y, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with alopecia areata in Korea: part I topical and device-based treatment. Ann Dermatol. 2023;35:190–204. doi: 10.5021/ad.22.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Survey criteria