Abstract

Background

Mendelian randomization (MR) has been used to identify drug targets in many conditions. Height is a classic complex trait affected by genetic and early-life environmental factors. No systematic screening has been conducted to identify drugs that interact with height. We investigated the causal relationship between genes and height, and systematically screened for interactive drugs that may promote or delay growth.

Methods

We performed MR using summary statistics from the Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits consortium (N=253,288), the UK Biobank (N=461,950), and the BioBank Japan Project (N=159,095). Gene expression-single-nucleotide polymorphism associations represented by cis-expression quantitative trait loci data were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression study and were used as genetic instruments. We performed annotation and enrichment analyses of the genes. Interactive drugs were identified through drug-gene interactions.

Results

Of the 27,094 genes screened, 209 had causal associations with height, including genes associated with height and short stature phenotypes (AMZ1, GNA12, NPPC, UQCC1, and ZBTB38), genes associated with height in a few studies (ANKIB1, CEP250, DCAF16, HIST1H4E, and HLA-C), and genes without previous evidence (BTN2A2 and RBMS1P1). Enrichment analysis showed that transcriptional regulation by RUNX1 was the most enriched pathway. Interactive drugs were identified, including amoxicillin, atenolol, infliximab, colchicine, propionyl-L-carnitine, BMN-111, and tamoxifen, which were known to have a positive effect on height. We also identified drugs that had a negative effect on height, including antineoplastic drugs, corticosteroids, and antiepileptic drugs. Moreover, many interactive drugs have not been previously reported to be associated with height.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that many genes have causal effects on height. By interrogating drug-gene interactions, interactive drugs have been identified as having both positive and negative effects on growth, which would help make clinical decisions.

Keywords: Mendelian randomization analysis (MR analysis), drug target prediction, body height, growth

Highlight box.

Key findings

• The study identifies 209 genes causally associated with height, and discovers a range of drugs with previously unreported positive and negative effects on height.

What is known and what is new?

• Height is a complex trait influenced by genetic factors and early-life environmental influences. Mendelian randomization has been recognized as a powerful tool in epidemiology to investigate the causal impact of risk factors on various conditions.

• This manuscript adds a comprehensive analysis to the existing body of knowledge by systematically screening for the first time a vast number of genes and their associations with height. It introduces new genetic markers linked to height, such as BTN2A2 and RBMS1P1, and expands on the known ones. Furthermore, it provides novel insights into the pharmacological landscape, identifying both positive and negative influences of specific drugs on height, which was previously unexplored.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The study’s findings have implications for developing targeted treatments for height-related conditions and necessitate further research to understand the mechanisms of drug effects on growth. Healthcare providers should consider these genetic and pharmacological influences when prescribing medications that may impact patients’ height.

Introduction

Linear growth is a complex process and is recognized as one of the best indicators of children’s health and well-being. Adequate height development during childhood is essential not only for physical health but also for psychosocial development, as it can impact self-esteem and social interactions (1,2). Short stature is shown to be associated with impaired quality of life, affecting both physical capabilities and psychological well-being (3). Additionally, research indicates that individuals with shorter stature may face increased risks for various health conditions, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (4,5) as well as metabolic disorders (6). This underscores height as a vital aspect of pediatric healthcare.

The main regulators of growth include genetics, epigenetics, and the environment. Previous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of height have identified genomic variants that are statistically associated with adult height, which explain 20–50% of phenotypic variance (7-10). Although height is highly heritable, there is evidence demonstrating the impact of epigenetic factors on height (11). The average height across European populations has increased over the last hundred years (12). The mean height of Chinese adolescents aged 18 years increased significantly at a rate of 1.3 cm/decade for males and 0.8 cm/decade for females over the last three decades (13). Identification of the epigenetic factors of height is helpful both to understanding the etiology and molecular mechanism of diseases and to informing the actions of modification. Many drugs exert their effects on growth although the mechanism has not been completely understood. Recombinant human growth hormone has been licensed for the treatment of short stature associated with growth hormone deficiency, Prader-Willi syndrome, being born small for gestational age, idiopathic short stature, Turner syndrome, short stature homeobox-containing gene deficiency, Noonan syndrome, and chronic renal insufficiency (14). C-natriuretic peptide analogues such as BMN-111 can improve growth in children with achondroplasia (15). Some drugs, on the contrary, are known to have issues with growth suppression (16-18). However, these findings come from individual studies, and no systematic screening has been conducted to identify drugs that interact with height.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a statistical genetics framework used to identify causal associations between pairs of genetically predicted traits using data from human genetic studies. It is increasingly employed due to its ability to address a significant issue with evidence from observational studies: confounding between exposure and outcome, regardless of whether the confounders are measured (19). Additionally, it can overcome the challenge of reverse causality (19). MR has been applied extensively across multiple fields, such as evaluating the causal significance of both endogenous and exogenous exposures, verifying and discovering causal effects for known risk factors of clinical relevance, determining the causal role of behavioral traits, simulating drug targets, and more (20). As an example, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, MR contributed to establishing the causal associations between COVID-19 and various factors such as interleukin-6, vitamin D, body mass index, and blood lipid (21).

MR studies have been conducted on the analysis of various phenotypes, including height. Most studies reported the causal effect of height on other diseases. In these studies, higher height has been shown to reduce the risk of atherosclerotic diseases, ischemic stroke, and coronary heart disease (22,23), while increasing the risk of cancer (22,23), atrial fibrillation (23,24), venous thromboembolism (23), and cardioembolic stroke (25). However, there has been no systematic scan of gene expression for novel causal mediators of height.

Drug-target disease pairs supported by human genetics analysis have greatly increased the odds of success in drug discovery pipelines (26). Proteins are frequently used as the principal regulators of molecular pathways and the targets of the majority of drugs. Genetic variants acting in “cis” on druggable protein levels or gene expression that encode druggable proteins can provide powerful tools for informing therapeutic targeting as they mimic the on-target effects observed by pharmacological modification (27). The discovery of disease-associated proteins with causal genetic evidence found using MR thus provides an opportunity to:

Identify novel therapeutic targets for a specific phenotype, such as COVID-19 (28), heart failure (29), and multiple sclerosis (30);

Repurpose licensed drugs (31); and

Identify potentially harmful effects on a specific phenotype (32).

In this study, we used MR to systematically screen the expression of 27,094 genes to investigate novel mediators of height, potential drug targets, opportunities for drug repurposing, and potential harmful effects of existing therapies. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE-MR reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-265/rc).

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Dataset

Exposure: gene expression-single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associations represented by cis-expression quantitative trait loci (cis-eQTL) data were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) study (version 6p) (33) using the R package “MRInstruments”. We used GWAS summary statistics from the following data sources to collect outcome information using the R package “TwoSampleMR” (34).

❖ Data A (ieu-a-89) (9): Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) consortium, including 253,288 Europeans (both males and females).

❖ Data A-M (ieu-a-96) (8): GIANT consortium, including 60,586 male Europeans.

❖ Data A-F (ieu-a-97) (8): GIANT consortium, including 73,137 female Europeans.

❖ Data B (ukb-b-10787) (35): UK Biobank, including 461,950 Europeans (both males and females).

❖ Data C (bbj-a-70) (36): BioBank Japan Project (BBJ), including 159,095 East Asians (both males and females).

Additional details on the data sources are provided in Table S1.

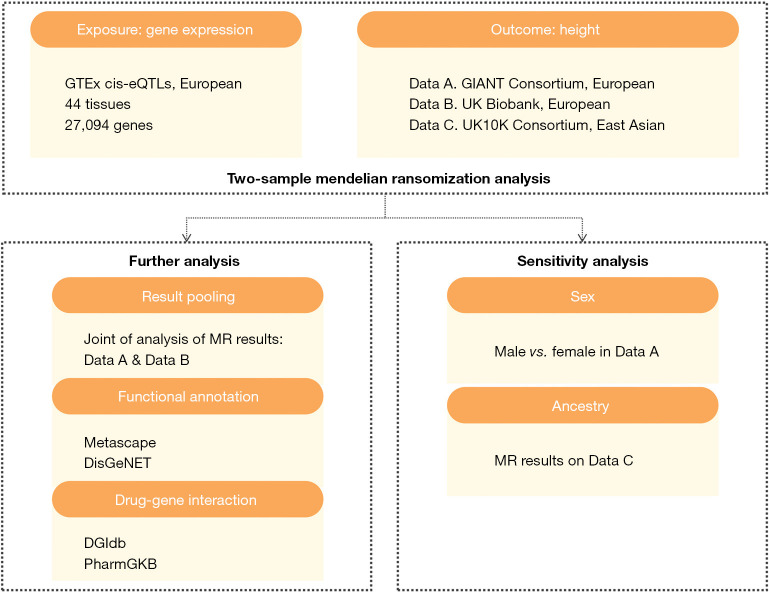

Study design

As shown in Figure 1, a two-sample MR study was performed using the eQTL data as the exposure and the GIANT consortium, UK Biobank, and BBJ consortium as the outcomes. We conducted further analysis, including result pooling, functional annotation, and drug-gene interactions. In the primary analysis, both the exposure and the outcome data were from individuals with European ancestry, thus similar in the genetic variant-exposure associations. The following three assumptions underpin MR analysis: (I) the genetic variants used as instrumental variables should be strongly associated with the exposure; (II) the utilized genetic variants should not be associated with any confounders; and (III) the selected genetic variants should affect the outcome merely through the risk factor rather than via alternative pathways. We also performed sensitivity analyses using subsets of different sexes and ancestries.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the study design. MR, Mendelian randomization.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.1.2).

The eQTL proposed instruments were obtained from the GTEx study (version 6p), resulting from conditional analysis of normalized gene expression in individuals of European ancestry in 44 tissues with at least 70 samples. We only included associations labeled as ‘is_choson_snp’ by GTEx, which includes 280,594 SNPs covering 27,094 genes.

For each outcome dataset, we performed two-sample MR analysis using the R package “TwoSampleMR” (34) with the following steps. First, SNPs from the exposure dataset were extracted from the outcome dataset, with the minimum linkage disequilibrium r2 threshold set to 0.8 and aligning tag alleles to target alleles enabled. Palindromic SNPs were allowed, with a minor allele frequency threshold for inference of 0.3. Second, the effects were harmonized, and duplicate summary sets were pruned based on sample size. Third, we used the fixed-effects, inverse-variance-weighted (IVW) method for proposed instruments that contain more than one variant and the Wald ratio for proposed instruments with one variant. The Wald ratio estimates are calculated as the regression coefficient for genetic association with the outcome divided by the regression coefficient for genetic association with circulating protein levels. The IVW estimates are calculated as the average of instrument ratio coefficients weighted by the inverse variance. We also tested the heterogeneity across variant-level MR estimates using the Cochrane Q method for proposed instruments with multiple variants. Exposures with a Q value below 0.05 will be discarded from further analysis. Multiple testing was adjusted using the Bonferroni correction method. The P value thresholds were calculated by dividing the desired significance level (α=0.05) by the total number of statistical tests [280,378] performed, which is 1.8−7. To prioritize the most significant exposures, we used much lower thresholds while reporting the results.

Concordance with previous reports was compared using data from DisGeNET (37). Annotation and enrichment analysis were performed using Metascape (38). Drug-gene interaction data were downloaded from DGIdb (39) (database version date: February 2022) and PharmGKB (40,41).

Results

MR analysis

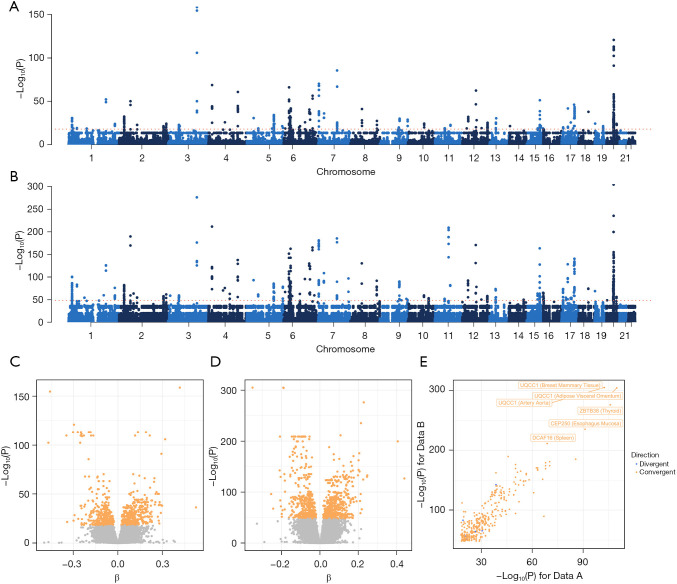

The significance levels of exposures determined by MR analysis are visualized using Manhattan plots for Data A (Figure 2A) and Data B (Figure 2B), which showed similar patterns. The P value thresholds for exposures to be selected for further analysis were determined based on the results: P<10−18 for Data A and P<10−48 for Data B. Using the thresholds, volcano plots are presented in Figure 2C for Data A and Figure 2D for Data B). Exposures satisfying the threshold requirements in both datasets were therefore analyzed, including 749 exposures of 209 genes (“selected genes”). Of the 749 exposures, 742 (99.1%) have the same effect direction between datasets. The P values of selected exposures were plotted in Figure 2E, showing highly convergent results.

Figure 2.

Mendelian randomization results. Manhattan plots depicting exposure-based test results of Data A (A) and Data B (B), volcano plots showing the statistical significance versus beta coefficients of Data A (C) and Data B (D), and the convergency between the two datasets (E). For Manhattan plots, the x-axis represents the genes’ genomic position, and the y-axis represents the statistical significance [−log10(P)]. The different colors (light blue and dark blue) show the extent of each chromosome. For volcano plots, the x-axis represents the beta coefficients of Mendelian randomization, and the y-axis represents the statistical significance [−log10(P)]. (C,D) Points in orange represent exposures with a P value lower than the threshold, while points in grey represent exposures with a P value above the threshold. In (E), the direction “Divergent” indicates that the beta coefficients for Data A and Data B have different signs.

For each gene being identified and selected, GWAS evidence was retrieved from DisGeNET (C0005890, body height, and C0489786, height). Exposures with minimal P values or strong clinical relevance are listed in Table 1. Notably, AMZ1 in the brain nucleus accumbens basal ganglia demonstrates a strong positive causal association with height, with a beta coefficient of 0.1031 (P=5.65E−71) in Data A and 0.0722 (P=6.68E−175) in Data B. Similarly, BTN2A2, CEP250, DCAF16, HIST1H4E, HLA-C, RBMS1P1, and ZBTB38 in specific tissues show positive causal associations with height in both datasets. In contrast, ANKIB1 in the esophagus gastroesophageal junction exhibits a negative association (β=−0.1981, P=2.76E−86 in Data A and β=−0.1348, P=7.30E−186 in Data B) with height. Furthermore, GNA12, NPPC, and UQCC1 in certain tissues demonstrate negative causal associations with height in both datasets. A full list of all selected exposures is shown in https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tp-24-265-1.pdf.

Table 1. Significant Mendelian randomization results.

| Gene | Tissue | Number of GWAS evidence from DisGeNET | Data Ab | Data Bc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | s.e. | P value | β | s.e. | P value | ||||

| AMZ1 | Brain nucleus accumbens basal ganglia | 10 | 0.1031 | 0.0058 | 5.65E−71 | 0.0722 | 0.0026 | 6.68E−175 | |

| ANKIB1 | Esophagus gastroesophageal junction | 1 | −0.1981 | 0.0101 | 2.76E−86 | −0.1348 | 0.0046 | 7.30E−186 | |

| BTN2A2 | Esophagus mucosa | 0 | 0.1803 | 0.0104 | 7.55E−67 | 0.1226 | 0.0047 | 3.28E−152 | |

| CEP250 | Esophagus mucosa | 1 | 0.2928 | 0.0144 | 8.12E−92 | 0.2141 | 0.0065 | 7.15E−236 | |

| DCAF16 | Spleen | 1a | 0.1440 | 0.0082 | 1.76E−69 | 0.1075 | 0.0035 | 4.94E−212 | |

| GNA12 | Artery tibial | 8 | −0.0988 | 0.0059 | 6.87E−64 | −0.0729 | 0.0026 | 3.11E−171 | |

| Cells EBV-transformed lymphocytes | −0.0568 | 0.0034 | 6.87E−64 | −0.0413 | 0.0015 | 1.37E−168 | |||

| Cells transformed fibroblasts | −0.1288 | 0.0076 | 6.87E−64 | −0.0935 | 0.0034 | 1.38E−167 | |||

| Colon sigmoid | −0.1368 | 0.0078 | 1.43E−68 | −0.0975 | 0.0035 | 6.68E−175 | |||

| Colon transverse | −0.2217 | 0.0127 | 1.43E−68 | −0.1571 | 0.0057 | 6.78E−170 | |||

| Esophagus mucosa | −0.1946 | 0.0111 | 1.43E−68 | −0.1415 | 0.0049 | 6.82E−180 | |||

| Esophagus muscularis | −0.0965 | 0.0054 | 5.65E−71 | −0.0693 | 0.0024 | 1.20E−181 | |||

| Heart left ventricle | −0.1304 | 0.0077 | 6.87E−64 | −0.0946 | 0.0034 | 1.37E−168 | |||

| Spleen | −0.0977 | 0.0058 | 6.87E−64 | −0.0710 | 0.0026 | 1.38E−167 | |||

| HIST1H4E | Whole blood | 1a | 0.2457 | 0.0142 | 7.55E−67 | 0.1670 | 0.0064 | 3.28E−152 | |

| HLA-C | Brain cerebellum | 9a | 0.0306 | 0.0028 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0215 | 0.0012 | 1.33E−73 | |

| Brain putamen basal ganglia | 0.0339 | 0.0031 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0238 | 0.0013 | 1.33E−73 | |||

| Adipose subcutaneous | 0.0310 | 0.0028 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0217 | 0.0012 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Artery aorta | 0.0269 | 0.0025 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0189 | 0.0010 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Artery coronary | 0.0266 | 0.0024 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0186 | 0.0010 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Brain hippocampus | 0.0333 | 0.0030 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0234 | 0.0013 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Cells EBV-transformed lymphocytes | 0.0279 | 0.0025 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0195 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Colon sigmoid | 0.0295 | 0.0027 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0207 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Colon transverse | 0.0322 | 0.0029 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0226 | 0.0012 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Esophagus gastroesophageal junction | 0.0274 | 0.0025 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0192 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Esophagus mucosa | 0.0349 | 0.0032 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0245 | 0.0014 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Esophagus muscularis | 0.0276 | 0.0025 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0194 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Heart atrial appendage | 0.0273 | 0.0025 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0191 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Nerve tibial | 0.0283 | 0.0026 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0198 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Stomach | 0.0346 | 0.0032 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0243 | 0.0013 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Thyroid | 0.0283 | 0.0026 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0199 | 0.0011 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| Whole blood | 0.0362 | 0.0033 | 7.63E−28 | 0.0254 | 0.0014 | 1.98E−73 | |||

| NPPC | Pancreas | 2 | −0.0523 | 0.0056 | 5.78E−21 | −0.0384 | 0.0025 | 2.24E−54 | |

| RBMS1P1 | Artery tibial | 0 | 0.2436 | 0.0145 | 3.77E−63 | 0.1750 | 0.0063 | 3.00E−171 | |

| UQCC1 | Adipose visceral omentum | 9 | −0.2514 | 0.0113 | 1.75E−110 | −0.1892 | 0.0051 | 6.88E−305 | |

| Artery aorta | −0.4690 | 0.0218 | 4.04E−103 | −0.3509 | 0.0094 | 1.41E−305 | |||

| Breast mammary tissue | −0.2544 | 0.0118 | 4.04E−103 | −0.1904 | 0.0051 | 1.41E−305 | |||

| ZBTB38 | Thyroid | 18 | 0.3182 | 0.0145 | 1.19E−106 | 0.2284 | 0.0064 | 1.15E−276 | |

a, Manually included; b, Data A (ieu-a-89): GIANT consortium, including 253,288 Europeans; c, Data B (ukb-b-10787): UK Biobank, including 461,950 Europeans. GWAS, genome-wide association studies; s.e., standard error; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

Sensitivity analysis by sex was conducted using Data A-M and Data A-F. The homogeneity between males and females in selected exposures is visualized in Figure S1. The analysis revealed consistent results for most exposures between males and females. However, there were a few inconsistent results, notably FAM133B in the brain nucleus accumbens basal ganglia, which showed a low P value for females and a high P value for males. MR results on Data A (Europeans) and Data C (East Asians) were compared to evaluate the potential interaction of ancestries (Figure S2). Notable differences were observed between the two ancestries. Some of the exposures with the largest differences are shown in Table S2.

Functional annotation

The selected genes were passed into Metascape for functional annotation and enrichment analysis. Pathway and process enrichment analysis results are shown in Table 2. Transcriptional regulation by RUNX1 was the most relevant pathway with the selected genes. Ten genes selected by our MR results were hit in the pathway of Transcriptional regulation by RUNX1 (CSNK2B, H2BC5, PSMC5, SMARCD2, H4C3, H4C8, H4C5, MYL9, SCMH1, and ITCH).

Table 2. Top 20 clusters with their representative enriched terms (one per cluster).

| GO | Description | Count | % | Log10(P) | Log10(Q) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-HSA-8878171 | Transcriptional regulation by RUNX1 | 10 | 5.71 | −5.87 | −1.53 |

| GO:1901987 | Regulation of cell cycle phase transition | 12 | 6.86 | −4.82 | −1.17 |

| GO:0017062 | Respiratory chain complex III assembly | 3 | 1.71 | −4.39 | −1.09 |

| GO:0048048 | Embryonic eye morphogenesis | 4 | 2.29 | −4.31 | −1.07 |

| GO:0051052 | Regulation of DNA metabolic process | 12 | 6.86 | −4.16 | −1.07 |

| GO:0051101 | Regulation of DNA binding | 6 | 3.43 | −4.14 | −1.07 |

| GO:0018193 | Peptidyl-amino acid modification | 13 | 7.43 | −3.48 | −0.78 |

| GO:0015697 | Quaternary ammonium group transport | 3 | 1.71 | −3.45 | −0.77 |

| WP4321 | Thermogenesis | 5 | 2.86 | −3.37 | −0.75 |

| GO:0060441 | Epithelial tube branching involved in lung morphogenesis | 3 | 1.71 | −3.35 | −0.75 |

| R-HSA-9006925 | Intracellular signaling by second messengers | 8 | 4.57 | −3.34 | −0.75 |

| R-HSA-211976 | Endogenous sterols | 3 | 1.71 | −3.30 | −0.74 |

| GO:0048660 | Regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation | 6 | 3.43 | −3.24 | −0.69 |

| GO:0018022 | Peptidyl-lysine methylation | 4 | 2.29 | −3.13 | −0.62 |

| WP5312 | Metabolic pathways of fibroblasts | 3 | 1.71 | −3.08 | −0.61 |

| GO:0008630 | Intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to DNA damage | 4 | 2.29 | −3.06 | −0.60 |

| R-HSA-556833 | Metabolism of lipids | 12 | 6.86 | −2.87 | −0.47 |

| GO:0061024 | Membrane organization | 12 | 6.86 | −2.79 | −0.43 |

| hsa04216 | Ferroptosis | 3 | 1.71 | −2.76 | −0.41 |

| GO:0009791 | Post-embryonic development | 4 | 2.29 | −2.69 | −0.37 |

GO, Gene Ontology.

Druggable target identification

The druggable categories of the genes classified using DGIdb are shown in Figure S3. Among the selected genes, 43 were druggable genomes. Details of the category annotation results are shown in Table S3. The selected genes were analyzed using DGIdb and PharmGKB for drug-gene interactions. Results from both databases were combined. Many antineoplastics have been identified as interactive drugs, including chemotherapy agents such as mitoxantrone dihydrochloride, carboplatin, and gemcitabine, as well as targeted therapies like erlotinib and imatinib. Other drugs positively and negatively related to height and the previously reported evidence are presented in Table 3. While amoxicillin, atenolol, infliximab, colchicine, propionyl-L-carnitine, BMN-11, and tamoxifen were associated with increased height, corticosteroids, and antiepileptic drugs have been reported to cause delayed growth. We also identified previously unknown compounds that may impact growth, including the antipsychotics fluspirilene and pimozide, the hormonal therapy diethylstilbestrol and vasopressin, and the nutraceutical propionyl-L-carnitine. The complete result list is provided in Table S4.

Table 3. Existing evidence for the identified drugs.

| Drug | Drug class | Interaction direction on height | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | Antibiotics | Positive | (42) |

| Atenolol | Beta-blockers | Positive | (43,44) |

| Infliximab | TNF alfa inhibitors | Positive | (45) |

| Colchicine | Gout therapy | Positive | (46) |

| Propionyl-L-carnitine | Misc | Positive | (47) |

| BMN-111 (vosoritide) | C-natriuretic peptide analogues | Positive | (15) |

| Tamoxifen | Antiestrogens | Positive | (48) |

| Cortisol, dexamethasone | Corticosteroids | Negative | (49) |

| Valproic acid, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin | Antiepileptic drugs | Negative | (50) |

TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the causal relationship between genes and height and systematically screened for interactive drugs that may promote or delay growth. Genes were identified to be causally associated with body height, including AMZ1, GNA12, NPPC, UQCC1, and ZBTB38, which have been associated with height and short stature phenotypes in various studies. ANKIB1, CEP250, DCAF16, HIST1H4E, and HLA-C have been associated with height in a few studies. Some genes, such as BTN2A2 and RBMS1P1, have not been previously reported. Transcriptional regulation by RUNX1 was the most enriched pathway with these causal genes. Associated drugs identified on the basis of drug-gene interactions include amoxicillin, atenolol, infliximab, colchicine, propionyl-L-carnitine, BMN-11, and tamoxifen, which were associated with increased height, and corticosteroids and antiepileptic drugs, which have been reported to cause growth retardation. There is no existing evidence on many of the drugs identified. Our findings have highlighted potential druggable targets and revealed opportunities for drug repurposing.

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic screening for interactive drugs that may promote or delay growth. Our workflow entails two steps. First, we identified genes causally associated with height using MR analysis. Modifications to the genes may therefore have clinical implications, which can be either positive, to promote growth, or negative, to inhibit growth. Second, we identified existing drugs that have interactions with the selected genes. Certain drugs have already been reported to be associated with height. Positive effects have been observed for amoxicillin (42), atenolol (43,44), infliximab (45), colchicine (46), propionyl-L-carnitine (47), BMN-111 (vosoritide) (15), and tamoxifen (48). Conversely, corticosteroids (like cortisol and dexamethasone) (49) and certain antiepileptic drugs (such as valproic acid, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin) (50) have been linked to negative effects on height. Other drugs identified may also have benefits for growth and therefore can be inspected and evaluated for the properness to be indicated, or, on the other hand, delay growth so that pediatric prescriptions should be avoided or closely monitored.

Many of the causal genes identified in this study are consistent with previous literature. ZBTB38 involved in transcriptional regulation has been found to be associated with familial short stature (51), idiopathic short stature (52), and short stature of undefined etiology (53). Its mutations were associated with a better response to recombinant human growth hormone therapy (54). NPPC has been reported to be a cause of isolated short stature in children (55). AMZ1 and GNA12 were reported to be associated with the rare copy number variations in Turner syndrome patients (56). While GWAS focuses on single-nucleotide polymorphisms, our study focuses on gene expression. Furthermore, while GWAS focuses on association, MR generally establishes causality. Thus, some genes previously published to be related to height in GWAS have not been demonstrated in the current study.

BTN2A2 and RBMS1P1 have not been previously reported to be associated with height. BTN2A2 is an immune modulator that inhibits the proliferation of activated CD4 and CD8 T-cells, affecting T-cell metabolism and cytokine secretion. Given the possible interplay between height and the immune system (57), further exploration of BTN2A2’s role may reveal its significance in growth regulation. RBMS1P1 is a pseudogene, and its regulatory functions have not been thoroughly investigated. Variations in pseudogenes can sometimes influence the expression of nearby genes, suggesting that RBMS1P1 may have an indirect role in height regulation.

In the enrichment analysis, several pathways we identified have also been reported to be associated with height in previous reports. Transcriptional regulation by RUNX1 was the most enriched. The RUNX1 transcription factor is a master regulator of hematopoiesis (58). It is known that chronic anemia has a negative effect on growth (59,60). However, the actual relationship has not been figured out (61). Our results supported a cross-talk between hematopoiesis and growth, and suggested that genes involved in the regulation of hematopoiesis have a causal relationship with height. The lipid metabolism pathway was also enriched in our study. The association between lower height and higher dyslipidemia risk has been established in a few studies (62,63). However, it has been attributed to a shared reason of a worse childhood condition. Our results suggest that there may also be genetic explanations.

We have identified drugs interacting with the selected genes. Some have been reported to have positive effects on height. C-natriuretic peptide analogues such as BMN-111 have shown their effects on improving growth in children with achondroplasia (15). Growth-promoting effects have been reported for antibiotics in prepubertal children and are more pronounced for ponderal than for linear growth (42), mediated by the treatment of clinical or subclinical infections or by modulation of the intestinal microbiota. The effects of beta-blockers on enhancing growth hormone secretion have also been reported in boys with constitutional delays in growth (43,44). In children with chronically active severe Crohn’s disease, growth velocity, and height percentile increased during infliximab therapy if patients were treated before or in early puberty (45). Colchicine was shown to improve height development significantly in familial Mediterranean fever patients (46). L-carnitine was shown to promote growth hormone secretion and growth (47), and was recommended as a routine treatment in short thalassaemic patients with growth hormone deficiency. In a chart review study, tamoxifen significantly increased the predicted adult height without having negative effects on sexual maturation (48). Of note, existing evidence supporting the identified drugs’ effect on height was mostly found in patients with specific pathological conditions. Whether the results can be generalized to general populations remains unclear.

There are also some drugs reported to have adverse effects on height, such as antineoplastics. In a longitudinal analysis of the growth of acute lymphoblastic leukemia children, treatment is associated with delayed growth during and after the treatment, even negatively affecting the final height (18). Corticosteroids are also known to decrease linear growth (49). Results from pediatric epilepsy patients using antiepileptic drugs encourage closely monitoring growth in children and adolescents under treatment (50). These results corroborate the results of our study and thus, the reliability of our workflow.

Moreover, many of the drugs have not been reported to affect height. For example, acetaminophen is a commonly used pediatric drug and was identified in our study as an interactive drug. Understanding its underpinning role in the association with height would help clinicians make evidence-based decisions. Dietary supplements like quercetin and curcumin were also identified in the study. Further investigation into them may provide suggestions for our lifestyle.

Our results also shed light on the potential mechanisms of the interactive drugs. For example, the negative effect of corticosteroids and the positive effect of BMN-111 on height may both be related to the drug target of NPPC. NPPC, also known as C-type natriuretic peptide, is crucial in promoting endochondral bone growth in humans (64). It has been reported to be a cause of isolated short stature in children (55). Examination of its protein-protein interactions revealed that NPPC interacts with natriuretic peptide receptors, guanylate cyclases, adenylate cyclases, and membrane metalloendopeptidases (Figure S4), all of which are known to be associated with body height by GWAS. NPPC may therefore be a potential drug target for height.

Sensitivity analyses revealed consistency between males and females, however, there are differences among races for the association between specific genes and height. For example, SLC39A5 was shown to be causally associated with height in the East Asian population but not in the European population, which is consistent with previous GWAS results (65). However, we are also aware of the limitation that the eQTL data we used include mostly individuals of European ancestry, thus not a perfect match to be used as the exposure in the East Asian population.

Our study offers several advantages. Firstly, unlike previous studies that focused on specific conditions, we examined height—a phenotype of universal interest—using MR. This broadens the implications for pediatric clinical practice. Secondly, MR allowed us to address confounding factors, establish causal relationships, and systematically identify genes associated with height in an unbiased manner. While MR has been widely used in cardiovascular diseases and cancer, its application in pediatrics is limited, making our study valuable in confirming its usefulness. Thirdly, our analyses integrated results from multiple datasets, thus benefiting from the large sample size, and were complemented by multi-faceted sensitivity analyses.

We acknowledge certain limitations in our study. Firstly, while we established causal relationships between genes and height using MR, downstream analyses such as enrichment analysis and drug-gene interaction identification were based on associations. Secondly, the beta coefficients from MR results do not directly indicate the effect sizes of drugs. They reflect the long-term consequences of perturbation and may not accurately predict the benefits of shorter-duration clinical interventions (66). Thirdly, the results of drug effects should be interpreted with caution. Though some drugs were identified as having a positive effect on height, their potentially adverse effects were not assessed. Though some drugs were identified as having a negative effect on height, discontinuing these drugs is not recommended without considering factors such as dose, duration, and the possibility of temporary effects that may not impact adult height upon discontinuation. Therefore, a careful evaluation of the benefits and risks associated with any identified drug is necessary. Given the in silico nature of our findings, the clinical significance of the identified drug remains uncertain, and further validation is required to substantiate these results.

Conclusions

In this study, we followed a two-step workflow to systematically screen for interactive drugs with height. The interactive drugs identified both positive and negative effects on growth, which would help inform clinical decisions. These findings warrant further assessment by conducting real-world studies, e.g., using data from electronic medical records in which both height and prescriptions are routinely recorded, in a fast and scalable way. Many identified drugs without existing evidence may also have clinical implications, which can be explored in future studies.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Feihong Luo from Children’s Hospital of Fudan University for his contributions during the discussion of this paper. His insightful suggestions and constructive feedback have greatly enhanced the quality of this work.

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE-MR reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-265/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-265/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hermanussen M, Scheffler C. Body height as a social signal. Papers on Anthropology 2019;28:47-60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stulp G, Buunk AP, Verhulst S, et al. Human height is positively related to interpersonal dominance in dyadic interactions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117860. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backeljauw P, Cappa M, Kiess W, et al. Impact of short stature on quality of life: A systematic literature review. Growth Horm IGF Res 2021;57-58:101392. 10.1016/j.ghir.2021.101392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabara Y, Shoji-Asahina A, Ogawa A, et al. Additive association of blood pressure and short stature with stroke incidence in 450,000 Japanese adults: the Shizuoka study. Hypertens Res 2024;47:2075-85. 10.1038/s41440-024-01702-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weingarten N, Iyengar A, Patel M, et al. Short stature is a risk factor for heart transplant morbidity and mortality. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2023;31:682-90. 10.1177/02184923231197691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toro-Huamanchumo CJ, Pérez-Zavala M, Urrunaga-Pastor D, et al. Relationship between the short stature and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance markers in workers of a private educational institution in Peru. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14:1339-45. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weedon MN, Lango H, Lindgren CM, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 20 loci that influence adult height. Nat Genet 2008;40:575-83. 10.1038/ng.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randall JC, Winkler TW, Kutalik Z, et al. Sex-stratified genome-wide association studies including 270,000 individuals show sexual dimorphism in genetic loci for anthropometric traits. PLoS Genet 2013;9:e1003500. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood AR, Esko T, Yang J, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat Genet 2014;46:1173-86. 10.1038/ng.3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yengo L, Vedantam S, Marouli E, et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 2022;610:704-12. 10.1038/s41586-022-05275-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issarapu P, Arumalla M, Elliott HR, et al. DNA methylation at the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) gene influences height in childhood. Nat Commun 2023;14:5200. 10.1038/s41467-023-40607-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatton TJ. How have Europeans grown so tall? Oxf Econ Pap 2014;66:349-72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song Y, Yan XJ, Zhang JS, et al. Gender difference in secular trends of body height in Chinese Han adolescents aged 18 years, 1985-2014. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2021;42:801-6. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200804-01014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danowitz M, Grimberg A. Clinical Indications for Growth Hormone Therapy. Adv Pediatr 2022;69:203-17. 10.1016/j.yapd.2022.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savarirayan R, Tofts L, Irving M, et al. Safe and persistent growth-promoting effects of vosoritide in children with achondroplasia: 2-year results from an open-label, phase 3 extension study. Genet Med 2021;23:2443-7. 10.1038/s41436-021-01287-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hata M, Ogino I, Aida N, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood: outcomes of late effects on pituitary function and growth in long-term survivors. Int J Cancer 2001;96 Suppl:117-24. 10.1002/ijc.10348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell SG, Frydenberg M, Thomsen PH. The effects of long-term medication on growth in children and adolescents with ADHD: an observational study of a large cohort of real-life patients. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2015;9:50. 10.1186/s13034-015-0082-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vilela MI, Viana MB. Longitudinal growth and risk factors for growth deficiency in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:86-92. 10.1002/pbc.20901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison S, Howe L, Davies AR. Making sense of Mendelian randomisation and its use in health research: A short overview. Cardiff: Public Health Wales NHS Trust & Bristol University 2020; 23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richmond RC, Davey Smith G. Mendelian Randomization: Concepts and Scope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2022;12:a040501. 10.1101/cshperspect.a040501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo S, Liang Y, Wong THT, et al. Identifying factors contributing to increased susceptibility to COVID-19 risk: a systematic review of Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol 2022;51:1088-105. 10.1093/ije/dyac076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howe LJ, Brumpton B, Rasheed H, et al. Taller height and risk of coronary heart disease and cancer: A within-sibship Mendelian randomization study. Elife 2022;11:e72984. 10.7554/eLife.72984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai FY, Nath M, Hamby SE, et al. Adult height and risk of 50 diseases: a combined epidemiological and genetic analysis. BMC Med 2018;16:187. 10.1186/s12916-018-1175-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin MG, Judy R, Gill D, et al. Genetics of height and risk of atrial fibrillation: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003288. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linden AB, Clarke R, Hammami I, et al. Genetic associations of adult height with risk of cardioembolic and other subtypes of ischemic stroke: A mendelian randomization study in multiple ancestries. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003967. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson MR, Tipney H, Painter JL, et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat Genet 2015;47:856-60. 10.1038/ng.3314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finan C, Gaulton A, Kruger FA, et al. The druggable genome and support for target identification and validation in drug development. Sci Transl Med 2017;9:eaag1166. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaziano L, Giambartolomei C, Pereira AC, et al. Actionable druggable genome-wide Mendelian randomization identifies repurposing opportunities for COVID-19. Nat Med 2021;27:668-76. 10.1038/s41591-021-01310-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henry A, Gordillo-Marañón M, Finan C, et al. Therapeutic Targets for Heart Failure Identified Using Proteomics and Mendelian Randomization. Circulation 2022;145:1205-17. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J, Zhou J, Xu Y. Potential drug targets for multiple sclerosis identified through Mendelian randomization analysis. Brain 2023;146:3364-72. 10.1093/brain/awad070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Interleukin-6 Receptor Mendelian Randomisation Analysis (IL6R MR) Consortium; Swerdlow DI, Holmes MV, et al. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet 2012;379:1214-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zhao JV, Schooling CM. Using Mendelian randomization study to assess the renal effects of antihypertensive drugs. BMC Med 2021;19:79. 10.1186/s12916-021-01951-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bahcall OG. GTEx pilot quantifies eQTL variation across tissues and individuals. Nat Rev Genet 2015;16:375. 10.1038/nrg3969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Elife 2018;7:e34408. 10.7554/eLife.34408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001779. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akiyama M, Ishigaki K, Sakaue S, et al. Characterizing rare and low-frequency height-associated variants in the Japanese population. Nat Commun 2019;10:4393. 10.1038/s41467-019-12276-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piñero J, Ramírez-Anguita JM, Saüch-Pitarch J, et al. The DisGeNET knowledge platform for disease genomics: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D845-55. 10.1093/nar/gkz1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun 2019;10:1523. 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cotto KC, Wagner AH, Feng YY, et al. DGIdb 3.0: a redesign and expansion of the drug-gene interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:D1068-73. 10.1093/nar/gkx1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whirl-Carrillo M, Huddart R, Gong L, et al. An Evidence-Based Framework for Evaluating Pharmacogenomics Knowledge for Personalized Medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;110:563-72. 10.1002/cpt.2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;92:414-7. 10.1038/clpt.2012.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gough EK, Moodie EE, Prendergast AJ, et al. The impact of antibiotics on growth in children in low and middle income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2014;348:g2267. 10.1136/bmj.g2267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martha PM, Jr, Blizzard RM, Rogol AD. Atenolol enhances growth hormone release to exogenous growth hormone-releasing hormone but fails to alter spontaneous nocturnal growth hormone secretion in boys with constitutional delay of growth. Pediatr Res 1988;23:393-7. 10.1203/00006450-198804000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghigo E, Bellone J, Arvat E, et al. Effects of alpha- and Beta-adrenergic agonists and antagonists on growth hormone secretion in man. J Neuroendocrinol 1990;2:473-6. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1990.tb00435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walters TD, Gilman AR, Griffiths AM. Linear growth improves during infliximab therapy in children with chronically active severe Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:424-30. 10.1002/ibd.20069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ozçakar ZB, Kadioğlu G, Siklar Z, et al. The effect of colchicine on physical growth in children with familial mediterranean fever. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:825-8. 10.1007/s00431-009-1120-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beshlawy AE, Abd El Dayem SM, Mougy FE, et al. Screening of growth hormone deficiency in short thalassaemic patients and effect of L-carnitine treatment. Arch Med Sci 2010;6:90-5. 10.5114/aoms.2010.13513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreher NC, Eugster EA, Shankar RR. The use of tamoxifen to improve height potential in short pubertal boys. Pediatrics 2005;116:1513-5. 10.1542/peds.2005-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuhlbrigge AL, Kelly HW. Inhaled corticosteroids in children: effects on bone mineral density and growth. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:487-96. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee HS, Wang SY, Salter DM, et al. The impact of the use of antiepileptic drugs on the growth of children. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:211. 10.1186/1471-2431-13-211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin YJ, Liao WL, Wang CH, et al. Association of human height-related genetic variants with familial short stature in Han Chinese in Taiwan. Sci Rep 2017;7:6372. 10.1038/s41598-017-06766-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Wang ZM, Teng YC, et al. An SNP of the ZBTB38 gene is associated with idiopathic short stature in the Chinese Han population. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79:402-8. 10.1111/cen.12145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perchard R, Murray PG, Payton A, et al. Novel Mutations and Genes That Impact on Growth in Short Stature of Undefined Aetiology: The EPIGROW Study. J Endocr Soc 2020;4:bvaa105. 10.1210/jendso/bvaa105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parsons S, Stevens A, Whatmore A, et al. Role of ZBTB38 Genotype and Expression in Growth and Response to Recombinant Human Growth Hormone Treatment. J Endocr Soc 2022;6:bvac006. 10.1210/jendso/bvac006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hisado-Oliva A, Ruzafa-Martin A, Sentchordi L, et al. Mutations in C-natriuretic peptide (NPPC): a novel cause of autosomal dominant short stature. Genet Med 2018;20:91-7. 10.1038/gim.2017.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li L, Li Q, Wang Q, et al. Rare copy number variants in the genome of Chinese female children and adolescents with Turner syndrome. Biosci Rep 2019;39:BSR20181305. 10.1042/BSR20181305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Polimanti R, Yang BZ, Zhao H, et al. Evidence of Polygenic Adaptation in the Systems Genetics of Anthropometric Traits. PLoS One 2016;11:e0160654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ichikawa M, Asai T, Chiba S, et al. Runx1/AML-1 ranks as a master regulator of adult hematopoiesis. Cell Cycle 2004;3:722-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimizu Y, Sato S, Koyamatsu J, et al. Height indicates hematopoietic capacity in elderly Japanese men. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:2407-13. 10.18632/aging.101061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soliman AT, Al Dabbagh MM, Habboub AH, et al. Linear growth in children with iron deficiency anemia before and after treatment. J Trop Pediatr 2009;55:324-7. 10.1093/tropej/fmp011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Allali S, Brousse V, Sacri AS, et al. Anemia in children: prevalence, causes, diagnostic work-up, and long-term consequences. Expert Rev Hematol 2017;10:1023-8. 10.1080/17474086.2017.1354696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oh NK, Song YM, Kim SH, et al. Short Stature is Associated with Increased Risk of Dyslipidemia in Korean Adolescents and Adults. Sci Rep 2019;9:14090. 10.1038/s41598-019-50524-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schooling CM, Jiang C, Lam TH, et al. Height, its components, and cardiovascular risk among older Chinese: a cross-sectional analysis of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1834-41. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bocciardi R, Ravazzolo R. C-type natriuretic peptide and overgrowth. Endocr Dev 2009;14:61-6. 10.1159/000207477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin E, Tsai SJ, Kuo PH, et al. Genome-wide association study in the Taiwan Biobank identifies four novel genes for human height: NABP2, RASA2, RNF41 and SLC39A5. Hum Mol Genet 2021;30:2362-9. 10.1093/hmg/ddab202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daghlas I, Gill D. Mendelian randomization as a tool to inform drug development using human genetics. Camb Prism Precis Med 2023;1:e16. 10.1017/pcm.2023.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]