Abstract

Background

Generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) is characterized by fluctuating muscle weakness. Exacerbation frequency, adverse events (AEs) related to immunosuppressant therapy and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) are not well understood. Our study aimed to describe long‐term clinical outcomes, drug‐related AEs and estimated HCRU in gMG patients.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort analysis of clinical data from patients with gMG followed‐up over eight consecutive years in a Spanish referral unit. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) clinical classification, MGFA post‐interventional status (MGFA‐PIS), Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG‐ADL) score, exacerbations, MG crises, therapies, AEs reported, specialist consultations and emergency room visits were studied biannually. An estimation of HRCU was made based on these data.

Results

Some 220 patients newly diagnosed with gMG were included. Ninety percent were seropositive (84.5% anti‐acetylcholine receptor [AChR], 5.9% anti‐muscle‐specific kinase [MuSK]). Baseline mean MG‐ADL score was 5.04 points (SD 3.17), improving to 0.7 points (SD 1.40) after 8 years. Exacerbations were more frequent in years 1–2 (30.1%) but still occurred in years 7–8 (20.2%). Myasthenic crisis frequency remained 1% in years 7–8. Eighty‐nine percent achieved MGFA‐PIS minimal manifestations or better at 8 years. Fifty‐one percent of patients reported at least one AE during the study period, leading to drug withdrawal in approximately 20% of cases. HCRU decreased between years 1–2 to years 7–8 with an estimated cost of MG from 8074.19 € per patient/year to 1679.46 €, respectively.

Conclusions

There is a group of MG patients that suffers from persistent symptoms and exacerbations (11%–20%) or MG crises, and drug AEs, which may increase disease burden and impact on the healthcare system.

Keywords: adverse drug reaction, health resource, immunosuppressant, myasthenia gravis

INTRODUCTION

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a rare, autoimmune, neuromuscular disease mediated by autoantibodies against diverse proteins of the postsynaptic membrane in the neuromuscular junction. This interaction leads to fluctuating muscle weakness. There are two main clinical phenotypes: (1) ocular MG (oMG) with muscular weakness involving extrinsic ocular muscles and eyelid muscles and (2) generalized MG (gMG) where muscle weakness involves cervical, bulbar, respiratory and limb muscles [1, 2].

For many patients, gMG is characterized by periodic acute exacerbations, or MG exacerbations, that impact their quality of life [3]. Some patients may experience MG crises, which are life‐threatening exacerbations leading to respiratory insufficiency and intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Exacerbations during the disease course may increase the number of visits to the emergency room (ER) department or consultations with neurology specialists and may lead to hospitalization, resulting in high costs for public health systems. The need for ICU admission during MG crisis further increases healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). Currently the annual rate of disease worsening and the clinical characteristics of those patients who deteriorate are not well known [4]. Reporting of HCRU is variable depending on the region and the characteristics of the population (e.g., age distribution, prevalent comorbidities) and this information is scarce in Spain [5, 6, 7].

In recent decades, several treatment strategies have been used to treat MG. Symptomatic treatments based on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and disease‐modifying treatments such as corticosteroids and nonsteroidal immunosuppressants (IST) have been primarily used as disease‐modifying drugs, with regimen choice based on immunological and patient's clinical characteristics. Thymectomy has proved to be effective in anti‐acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibody‐positive disease [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Immunomodulatory drugs including intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasma exchange (PLEX) can be used acutely during clinical exacerbations, MG crises and, sometimes, as a coadjuvant chronic therapy in patients with drug‐refractory MG, but these therapies have short‐term effects. Despite the widespread use of nonsteroidal ISTs in gMG, prescribing is often off‐label, and their safety profiles have been primarily described in other autoimmune diseases. Evidence from randomized clinical trials on the frequency and severity of adverse events (AEs) in MG patients and on long‐term safety are therefore scarce. The incidence of AEs, some of them serious, may increase the burden of disease in MG, sometimes leading to therapy changes, and also increasing the costs related to disease management.

The aim of our study was to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes, including occurrence of exacerbations and myasthenic crisis, incidence and severity of drug‐related AEs, and to estimate HCRU in gMG patients diagnosed and followed for eight consecutive years in a referral unit in Spain.

METHODS

Data source

The Neuromuscular Diseases Unit database is a single‐center dataset that includes individual medical and pharmacy electronic records of patients with confirmed MG diagnosis attending the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (HSCP) in Barcelona, Spain. The HSCP Neuromuscular Diseases Unit is a referral unit for patients with neuromuscular diseases from different geographical areas in Spain.

MG was diagnosed by a consultant neurologist based on compatible clinical features together with one or more of the following criteria: (1) positive results on an AChR or muscle‐specific kinase (MuSK) antibody assay; (2) electrophysiological study findings compatible with a postsynaptic neuromuscular junction disorder (repetitive stimulation, single‐fiber electromyography, or both); and (3) clinical response to cholinesterase inhibitors.

Patients were recruited and data collected by neurologist experts in neuromuscular diseases. The dataset for this study comprises demographic, clinical, immunologic and therapeutic information from a baseline assessment at MG diagnosis or first assessment after diagnosis in another center, and up to four consecutive biannual follow‐up medical assessments.

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort analysis. The study period started on 1 January 1998 and ended on 31 December 2020. The study cohort included all patients aged 18 years or more at first clinical visit with gMG, diagnosed between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2018. Patients were followed from the first visit in our referral unit with a frequency of visits dependent on the severity of MG symptoms and drug changes based on clinical judgement. Data were included from first visit in our unit until the earliest of the following dates: 8 years' follow‐up achievement, the study period end date, the last clinical record available before 31 December 2020, or patient death. The follow‐up period was split into four biannual periods post MG diagnosis to assess study outcomes (Figure 1).

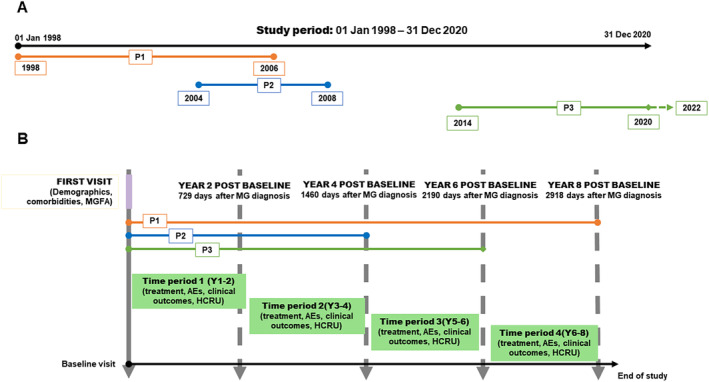

FIGURE 1.

Study design and example. Upper panel (A) shows an example of three hypothetical patients (P1, P2 and P3) included in our study. P1 had a complete 8‐year follow‐up. P2 had an incomplete 4‐year follow‐up because of attrition or death. P3 had an incomplete 6‐year follow‐up because of the end of study period. Lower panel (B) illustrates the study design from the baseline visit, with biannual periods (time periods) of observation. It also represents the aforementioned hypothetical patients organized from first visit to our center, considered as the baseline study visit. From the first visit or baseline visit data on clinical outcomes, treatments, adverse effects and healthcare resource utilization were collected for every biannual period. Data were collected biennially until patients reached 8 years of follow‐up, follow‐up reached 31 December 2020 or the patient's death. AE, adverse effect; HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; MG, myasthenia gravis; MGFA, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America; P, patient; Y, year.

The study excluded patients with oMG, defined as Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America class I (MGFA class I) [13] during all the study period, those initially diagnosed and followed for longer than 2 years in another center or with a different usual MG center, and patients enrolled in a MG drug clinical trial during the first 2 years after diagnosis. Information about patients that were enrolled in a clinical trial after the first 2 years post‐diagnosis was included and data during the trial was censored. Patients with oMG phenotype at disease onset who progressed to generalized disease during the study period were included.

Informed consent and ethics committee approval

Every patient provided a written informed consent for inclusion of clinical data and biological samples in the Neuromuscular Diseases Unit from Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau database and sample collection (code c.0002365). The study was approved by the local ethics committee (code IIBSP‐MGG‐2022‐12).

Study procedures and definitions

Patient baseline characteristics were recorded at first clinical visit during the study period, hereafter designated as “baseline visit”.

Study outcomes included clinical characteristics, prescribed medication, AEs and HRCU:

Clinical characteristics: Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) clinical classification [14] and Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG‐ADL) scale [15, 16] were collected at baseline visit and in the clinical visit that was closest to the beginning of each time period ±2 months. MGFA post‐interventional status (MGFA‐PIS) classification [14] was collected at the clinical visit that was closest to the beginning of each time period ±2 months. Minimal symptoms expression was defined as presenting mild symptoms, equivalent to MG‐ADL score <2 [17]. Data about thymic pathology and thymectomy were also collected. Thymectomy was offered to all patients with a suspicion of a thymoma based on chest imaging evaluation (computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging). Patients included before 2016 without suspicion of malignant thymic pathology were not systematically offered thymectomy. From 2016 onwards all patients with gMG, anti‐AChR‐positive and early onset were recommended thymectomy [8].

Frequency of clinical exacerbations, defined as a worsening in clinical status in a patient previously in stable or pharmacologic remission, or with minimal manifestations as per MGFA‐PIS classification [14]; and MG crisis, defined as exacerbations leading to severe respiratory distress and mechanical ventilatory support (MGFA V) [13], were collected during the study period.

Medications: Patients were treated according to the standard of care following international recommendations [13] using pyridostigmine as needed. Prednisone (PDN) was started at 1 mg/kg/day dose and then doses were tapered on alternate days if possible, based on MG symptom severity, tolerance and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory therapy (IVIG and PLEX) was used as rescue therapy to treat patients with moderate to severe gMG. Chronic immunomodulatory therapy was administered to no responders or intolerant to immunosuppressors, with periodicity tailored to the patient's symptoms. Azathioprine (AZA) dose was calculated based on thiopurine methyltransferase activity (TPMT) and weight. Immunosuppressant drug (IS) dosage, such as mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclosporine, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, was adjusted as specified by local guidelines [18]. AZA and MMF were usually the first immunosuppressant therapies (IST) prescribed. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus were used if AZA and MMF were ineffective, produced side effects, or were contraindicated. Rituximab and cyclophosphamide were used for drug‐refractory anti‐AChR‐positive MG; for anti‐MuSK MG, rituximab was an earlier option from 2012 onwards [10]. For IST and chronic immunomodulatory therapies, once treatment goals were achieved, the drug was maintained for at least 1–2 years and then tapered to the minimal effective dosage [13]. Neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) blockers and complement inhibitors were not used as they were not approved for MG in Spain during the study period. Time from baseline visit to treatment start and discontinuation were collected.

Drug refractory status was defined as lack of clinical changes following treatment with corticosteroids and two other IS agents [13]. Drug refractoriness was evaluated biannually during the study follow‐up.

Immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory agent‐related AEs were collected with groups defined by the most common event types: cephalalgia, digestive impairment (including abdominal pain and non‐infectious diarrhea), bone fracture, urinary infection, respiratory infection, digestive infection and other infections. Other AEs included very infrequent AEs. Severity of each AE was graded using the European Medicines Agency's classification, as mild (awareness of signs or symptoms, but easily tolerated), moderate (events introduce a low level of inconvenience or concern to the participant and may interfere with daily activities), severe (events interrupt the participant's normal daily activities and generally require systemic drug therapy) or serious (events that result in hospital in‐patient stay, an extension of a hospital stay, permanent disability or death) (ema.eu protocol CPMP/ICH/377/95). The causative drug was decided based on drug administration timing, AE appearance and clinical judgement. For AEs from co‐administered drugs (e.g., infection in a patient receiving prednisone and an immunosuppressant drug), the AE was attributed to both treatments.

HCRU and costs: Direct costs from inpatient and outpatient services (length of MG‐related hospitalizations and ICU stays; number of ER visits, days of hospital/ambulatory day care and MG‐related neurologist or other specialist consultations) and pharmacy, including dose of hospital‐administered IVIG (hospitalization or day hospital administration) and number of PLEX sessions. Given the long duration of the study (1998–2020) and variability in costs over this period, 2022 prices for drugs and procedures were used. Hospital department price estimations from 2022 were: IVIG, 478.31 €/10 g; hospitalization, 634.23 € per day; ICU, 2019.87 € per day; day hospital, 286.67 € per session; first ambulatory consult: 181.39 €; follow‐up consult, 90.7 €; ER consult: 234.67 €; PLEX, 1209 € per session; thymectomy surgery, 8922€.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 723 new MG patients visited the Neuromuscular Disease Unit during the 1998–2020 period. Of those, 125 (17.3%) had oMG phenotype during the study period (and transitioned to gMG) and 378 (52.3%) did not meet the study selection criteria (Figure 2). The remaining 220 gMG patients were included. Median age at baseline visit was 70.0 (P25–P75 56–83) years and 120 (54.5%) were female. (Table 1). Some 166 patients (60.5%) had been diagnosed by another neurologist a median of 2.07 (P25–P75 1.03–6.07) months prior to the first assessment in our referral unit.

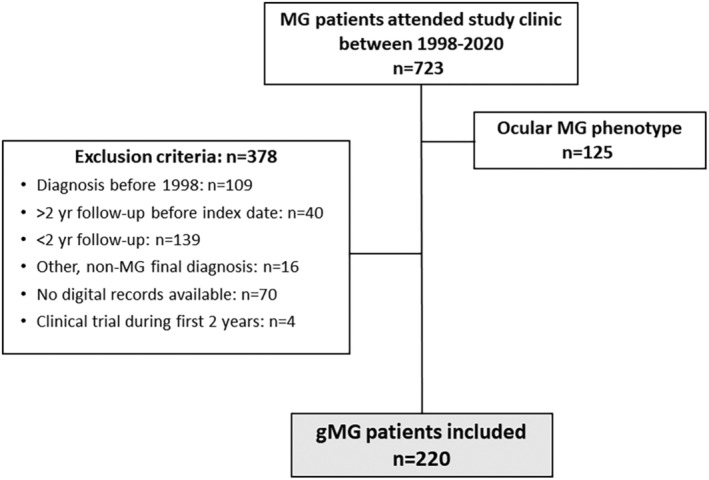

FIGURE 2.

Study participants’ flow diagram. gMG, generalized myasthenia gravis; MG, myasthenia gravis.

TABLE 1.

Description of demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients (N=220).

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Sex female, n (%) | 120 (54.5) |

| Median age at first MG symptom, years (P25–P75) | 60.5 (44.3–73.0) |

| Median age at first visit, years (P25–P75) | 70.0 (56–83) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Time from first symptom to diagnosis, months (SD) | 8.8 (21.3) |

| Time from baseline visit to diagnosis, days a (SD) | 48 (132.0) |

| Autoimmunity, n (%) b | |

| Anti‐AChR | 186 (84.5) |

| Anti‐MuSK | 13 (5.9) |

| Seronegative | 22 (10.0) |

| Baseline MGFA clinical classification, n (%) | |

| I | 77 (35.0) |

| IIA | 48 (21.8) |

| IIB | 58 (26.4) |

| IIIA | 7 (3.2) |

| IIIB | 17 (7.7) |

| IVA | 1 (0.5) |

| IVB | 9 (4.1) |

| V | 3 (1.4) |

| MGFA class at maximal worsening during the study follow‐up, n (%) | |

| IIA | 48 (21.8) |

| IIB | 49 (22.3) |

| IIIA | 34 (15.5) |

| IIIB | 47 (21.4) |

| IVA | 5 (2.3) |

| IVB | 24 (10.9) |

| V | 13 (5.9) |

| Drug refractory status during study follow‐up, n (%) | 22 (10.0) |

| Death during study period n, (%) | 27 (12.3) |

Abbreviations: AChR, acetylcholine receptor; MG, myasthenia gravis; MGFA, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America; MuSK, muscle‐specific kinase; P, percentile; SD standard deviation.

Among the 133 (60.5%) patients who were diagnosed after their first visit.

One patient was anti‐AChR‐positive and anti‐MuSK‐positive.

Patient outcomes over 8‐year study follow‐up

In total, 219 (99.5%) patients completed the initial biannual follow‐up consultation (time period 1), 164 (74.5%) completed 4 years (time period 2), 124 (56.4%) completed 6 years (time period 3) and 94 (42.7%) completed the 8‐year follow‐up (time period 4). One patient had incomplete follow‐up during the first study time period (year 1–2) but resumed follow‐up at the third year, and was included from time period 2 (year 3–4). For 104 patients the baseline visit occurred after 31 December 2012 and their duration of study follow‐up was less than 8 years. Five patients were lost to follow‐up before completing 8 years of follow‐up.

Twenty‐seven patients died between 1998 and 2020. Seventeen patients died during the study follow‐up causing an attrition, and 10 patients died after having completed the 8 years of follow‐up. None of the patients died from MG or MG‐related complications (e.g., cardiovascular disease related to hypertension and diabetes and malignancies).

Sixty‐seven patients (30.5%) had their thymus removed, eight of them prior to baseline. All of them had their elective thymectomy during the first 2 years after diagnosis. Thymoma (29/67; 43.3%) and thymic hyperplasia (24/67; 35.8%) were the two main pathologic findings in surgical biopsies. Fourteen thymectomized patients had an atrophic or normal thymus.

MG clinical manifestations

Table 2 details the MG‐ADL, MGFA class, MG exacerbations and MG crisis during the study period. Seventy‐seven patients (35.0%) presented exclusively with ocular symptoms at diagnosis (MGFA class I) and progressed to generalized disease within the first 3 years from diagnosis (mean time of 8.9 months; standard deviation [SD] 13.5).

TABLE 2.

Description of clinical outcomes (mean Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living [MG‐ADL] score, number and percentage of exacerbations, myasthenia gravis crisis, minimal symptoms expression and Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America [MGFA] class) during the biannual study follow‐up periods.

| Clinical outcome | Baseline (N = 220) | Year 1–2 (N = 219) | Year 3–4 (N = 164) | Year 5–6 (N = 124) | Year 7–8 (N = 94) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean MG‐ADL score (SD) | 5.04 (3.17) | 1.56 (2.30) | 1.09 (1.83) | 1.15 (2.06) | 0.7 (1.40) |

| Minimal symptom expression, n (%) | NA | 141 (64.4) | 115 (70.0) | 82 (66.1) | 69 (73.4) |

| Exacerbations in 2 years, n (%) a | NA | 112 (30.1) | 54 (23.8) | 28 (22.6) | 20 (20.2) |

| Myasthenic crisis in 2 years, n | NA | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| MGFA class, n (%) | |||||

| Asymptomatic | NA | 104 (47.1) | 95 (57.9) | 79 (63.7) | 63 (67) |

| I | 77 (35.0) | 18 (8.1) | 15 (9.1) | 10 (8.1) | 7 (7.4) |

| IIA | 48(21.8) | 59 (26.9) | 33 (20.1) | 22 (17.7) | 18 (19.1) |

| IIB | 58 (26.4) | 25 (11.4) | 14 (8.5) | 10 (8.1) | 5 (5.3) |

| IIIA | 7 (3.2) | 6 (2.7) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| IIIB | 17 (7.7) | 4 (1.8) | 4 (2.4) | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| IVA | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IVB | 9 (4.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| V | 3 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: MG‐ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; MGFA, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America; NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation.

Percentage of patients experiencing exacerbations.

Concerning MG‐ADL assessment, we noticed a decrease in the mean total MG‐ADL score from 5.0 (SD 3.2) to 0.7 (SD 1.4) after 8 years’ follow‐up. The MG‐ADL assessment by score domain (ocular, bulbar, limb and respiratory) at baseline showed a patient mean ocular score of 2.2 (SD 1.62), bulbar score of 1.8 (SD 2.0), limb score of 1.0 (SD 1.3) and respiratory score of 0.2 (SD 0.6). At 8 years’ follow‐up (time period 4), patients had a mean ocular MG‐ADL score of 0.5 (SD 0.9); bulbar score of 0.1 (SD 0.5); limb score of 0.2 (SD 0.6) and respiratory score of 0.0 (SD 0.3).

A total of 86 patients (39.1%) had at least one clinical exacerbation during follow‐up, and 47.1% of them had more than one exacerbation. All the MG crises reported belonged to the same patient except for the two MG crises observed in a male patient with late‐onset anti‐AChR gMG, predominantly bulbar symptoms and no thymic pathology, during time period 3.

The number of MG crises and MG exacerbations decreased over time but events were observed during the 8 years of patient follow‐up.

Treatment‐related outcomes

At baseline, 86 patients had started pyridostigmine and PDN treatment at another center, 9 had AZA, 2 MMF, 2 tacrolimus, 2 cyclosporine and 1 rituximab. Furthermore, two patients had been referred to our center for drug refractoriness.

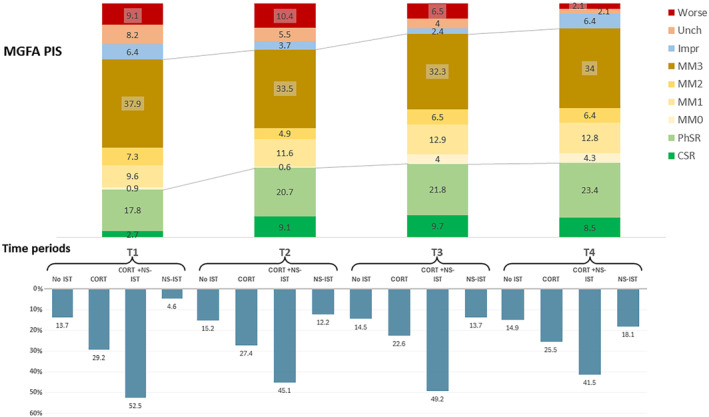

During the study period, 187 (85.0%) patients required pyridostigmine treatment, 191 (86.8%) used PDN, 105 (47.7%) AZA, 75 MMF, 47 (21.4%) cyclosporine A, 5 (2.3%) cyclophosphamide, 6 (2.7%) periodic IVIG and 2 (0.9%) periodic PLEX. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of use of the various therapies and drug combinations over time and the evolution of the response based on MGFA‐PIS classification (Figure 3). At year 1–2 period end 13 patients were drug‐refractory (11 new drug‐refractory patients); 14 patients at year 2–4 period end (4 of them newly refractory); 16 at year 5–6 period end (4 new refractory) and 16 at year 7–8 period end (1 new refractory).

FIGURE 3.

Drug use and clinical outcome (Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America post‐interventional status, MGFA‐PIS) in each time period. The upper panel shows MGFA‐PIS at each study period. The lower panel shows information about immunosuppressant therapy use at each study time period. CORT + NS‐IST, combination of corticosteroids and nonsteroidal IST; CORT, corticosteroids; CSR, clinical stable remission; Impr, improved; MM, minimal manifestations; No IST, no immunosuppressant therapies, but may be using pyridostigmine; NS‐IST, nonsteroidal IST; PhSR, pharmacologic stable remission; Unch, unchanged.

Table 3 describes the occurrence of AEs and the percentage of patients who stopped drug use during the study period.

TABLE 3.

Description of adverse events (AEs) and AE‐related drug interruptions.

| Drug/procedure | AEs reported/patients n (%) | Patients with AE‐related interruptions n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Pyridostigmine | 19/187 (10.2) | 10 (5.3) |

| Prednisone | 65/191 (34.0) | 36 (18.8) |

| Azathioprine | 35/105 (33.3) | 21 (20.0) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 25/75 (33.3) | 14 (18.7) |

| Cyclosporine A | 23/47 (48.9) | 10 (21.3) |

| Tacrolimus | 2/17 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 3/5 (60.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| Periodic IVIG | 2/6 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Rituximab | 2/17 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) |

| Periodic plasma exchange | 1/2(50.0) | 1 (50.0) |

Note: For each drug or procedure, total number of patients with AEs, total number of patients treated with the drug and percentage (in parentheses) of treated patients with AEs are shown in the second column. Total number of patients and percentage (in brackets) of patients with AE‐related interruptions are shown in the third column.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulins.

Fifty‐one percent of patients (n = 112) experienced at least one AE during follow‐up. The mean number per patient was 0.75 (P25–P75 0–1). Overall, 107 AEs from 83 patients were reported during year 1–2, 32 from 23 patients during year 3–4, 26 from 19 patients during year 5–6, and 12 from 8 patients during year 7–8. Table S1 shows the AEs classified by drug and severity in each biannual period.

HCRU and costs of MG care

The number of patients requiring neurology ward admissions during the consecutive biannual observational periods were 92 (42.0%; year 1–2), 18 (11.0%; year 3–4), 9 (7.3%; year 5–6) and 4 (4.3%; year 7–8). Similarly, the number of patients who required day hospital care were 39 (17.8%), 16 (9.8%), 16 (12.9%) and 1 patient (1.1%), respectively. Table 4 summarizes the total number of neurology consultations, days of hospitalization due to MG exacerbations or treatment‐derived complications, days in ICU due to MG or treatment‐derived complications, and days of outpatient hospital. There was a decrease in HCRU over the study duration. Estimated MG‐related costs were highest during the first 2 years from diagnosis.

TABLE 4.

Description of myasthenia gravis‐related healthcare resource utilization during the study follow‐up periods.

| Parameter | Year 1–2 (N = 219) | Year 3–4 (N = 164) | Year 5–6 (N = 124) | Year 7–8 (N = 94) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory neurologist consultations (per patient/year) | 1916 (4.38) | 1075 (3.28) | 720 (2.67) | 495 (2.38) |

| Other specialist consultations (per patient/year) | 340 (0.78) | 123 (0.38) | 96 (0.39) | 52 (0.28) |

| Hospital admission due to MG or complications (days per patient/year) | 1249 (2.85) | 267 (0.82) | 280 (1.13) | 53 (0.28) |

| Hospitalization due to thymectomy (days per patient/year) | 479 (1.09) | NA | NA | NA |

| Day hospital sessions (days per patient/year) | 458 (1.05) | 157 (0.48) | 122 (0.49) | 8 (0.04) |

| ER consultations due to MG (per patient/year) | 20 (0.05) | 22 (0.07) | 12 (0.05) | 0 |

| ICU admission (days per patient/ year) | 81 (0.18) | 13 (0.04) | 50 (0.20) | 62 (0.33) |

| Total amount of IVIG in grams (per patient/year) | 24,138 (55.11) | 7650 (23.32) | 5590 (22.54) | 2195 (11.67) |

| PLEX sessions (per patient/year) | 90 (0.21) | 23 (0.07) | 25 (0.10) | 0 |

| Estimated costs of MG care (per patient/year) | 3,496,952.65 € (8074.19 €) | 748,132.75 € (2280.89 €) | 689,793.58 € (2774.09 €) | 315,739.24 € (1679.46 €) |

Note: Total and mean number per patient/year are shown for each timepoint analyzed. Data about health care consumption per patient and year are shown in parentheses.

Abbreviations: ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MG, myasthenia gravis; NA, not applicable; PLEX, plasma exchange.

DISCUSSION

In this study we comprehensively described the clinical evolution and management of a cohort of gMG patients during the first 8 years of disease, including clinical outcomes, therapies, HCRU and related costs.

Disease severity and symptom expression usually vary throughout the disease course. In our study, we observed that disease activity was much higher in the first 2 years after diagnosis: mean MG‐ADL scores were higher (with a higher burden of ocular and bulbar symptoms), patients experienced more disease exacerbations and MG crises, and needed immunomodulatory rescue therapies more often than at later timepoints. Although the IST developed over recent decades have improved patients' prognosis, our study shows that a considerable number of patients remain symptomatic, and some may experience exacerbations and even MG crises during the 8 years of follow‐up. We found that 65%–70% of patients achieved minimal symptom expression, which is the usual treatment goal, during the study period. In addition, 10% of MG patients became drug‐refractory during follow‐up. All these observations suggest that MG is an unpredictable disease and that new, more effective therapies capable of maintaining disease stability are urgently needed.

However, drug‐refractoriness is not the only unmet need in MG. In our study, we showed a high incidence of AEs related to IST, leading to drug withdrawal in 5%–25% of patients depending on the drug and AE severity. Some of the AEs registered were serious, potentially leading to increased disease burden and potentially affecting patients' quality of life. The current, widely used drug‐refractory definition includes both the patients not responding to treatment and patients who need to discontinue therapies because of side effects, limiting the therapeutic options available to treat MG [19, 20]. Given the difference between both patient subgroups, it might be appropriate to consider patients who are either drug‐refractory [13] or therapy intolerant as “hard‐to‐treat” MG patients. Drug intolerance may be determined by the toxicity of the treatment and the biological features, including pharmacogenetics, of the pre‐morbid MG patient, whereas drug‐refractoriness seems to depend on disease severity and immunological features. However, both situations lead to difficulties in the treatment of patients [21, 22]. A new hope for “hard‐to‐treat” MG patients may be the new emergent agents that act on non‐cellular targets, such as anti‐complement and anti‐FcRn therapies. These drugs have demonstrated efficacy and tolerability in clinical trials with a faster onset of action, which are important attributes when treating MG exacerbations and crises [23, 24, 25].

The clinical characteristics of MG and the nature of the therapies in use make it necessary to follow patients closely, resulting in high HCRU. The Spanish health system is based on universal access to healthcare independent of patient income. Also, the drugs and other therapeutic procedures are unrestricted, administered in accordance with clinical guidelines and clinician judgment. The study findings reflect MG management in Spain and provide new data about HCRU and related costs for MG in a national healthcare organization. Many HCRU studies focus on pharmacological costs, but in the case of MG the resources needed also include inpatient and outpatient services (e.g., ER consultations, hospitalizations, ICU admissions, day hospital care, neurologist and other specialists' consultations) and non‐pharmacological interventions, such as thymectomy and PLEX, that increase financial burden. Our study considered these costs, showing a high HCRU and associated costs, particularly during the first 2 years after MG diagnosis.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically and comprehensively describe the clinical manifestations (measured by commonly used scales such as MG‐ADL, MGFA clinical classification and MGFA‐PIS), immunological status, drug use and associated AEs and HCRU in a universal health care system, using a reliable source of information from clinical records obtained by trained neuromuscular disease neurologists in a reference unit and over a long time period (up to 8 years’ post‐diagnosis). Other similar studies about clinical characteristics [26], drug use and AEs [27] and HCRU [5, 7, 28, 29] were based on information from general practitioners (GPs), based on insurance claim databases [30, 31, 32, 33], were patient‐based registries [34] or had shorter follow‐up periods. Despite differences in design, evidence from previous studies also suggest that MG activity is higher at the beginning of the disease course, with a greater number of exacerbations and MG crises and, thus, higher MG‐related HCRU and costs.

The main study limitation is the retrospective design and use of an existing database created from medical and pharmacy records that may result in missing information. However, completeness of the information analyzed was extremely high. A second potential limitation is the high proportion of patients with late MG onset included. Nevertheless, a previous study confirmed the high prevalence of late‐onset MG in our region (Catalonia) [35].

Third, this is a single‐center study conducted in a reference unit in Spain, which might limit the generalizability of the findings, as clinical criteria may differ between centers across Europe and countries outside Europe; and the study population may overrepresent hard‐to‐treat patients. In addition, reported HCRU is likely to be underestimated given that cost of the commonly prescribed IST and pyridostigmine, GP consultations or other specialists not working in our center, and indirect costs due to disability, medical sick leave, workdays' loss, absenteeism, and caregiver expenses, were not considered. Furthermore, the expected lower HCRU of patients who had oMG at baseline (one in three study patients) might have contributed to the dilution of the initial peak in HCRU during years 1 and 2. Also, the use of a reference price table from 2022 throughout the study period influenced the reported cost estimations. Finally, our study lacks information about quantitative clinical assessment (such as the Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis [QMG] scale) and quality of life scales, which would have enabled a more complete description of the real burden of MG.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite great improvement in MG management owing to the wide range of immunosuppressive drugs available in recent decades, there is still a group of patients (11%–20%) that suffer from persistent MG symptoms, exacerbations or MG crises, and drug AEs which impact clinical management and the healthcare system.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

David Reyes‐Leiva: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; formal analysis; writing – original draft. Álvaro Carbayo: Data curation; writing – review and editing. Ana Vesperinas‐Castro: Data curation; writing – review and editing. Ricard Rojas‐García: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Luis Querol: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Janina Turon‐Sans: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Francesc Pla‐Junca: Data curation; writing – review and editing; investigation. Montse Olivé: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Eduard Gallardo: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. Mar Pujades‐Rodriguez: Data curation; methodology; conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Elena Cortés‐Vicente: Conceptualization; data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing; investigation; funding acquisition.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by UCB Pharma. A.C. is supported by the Río Hortega Contract (CM21/00057) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III. E.C.‐V. is supported by the Juan Rodés Contract (JR19/00037) from Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

David Reyes‐Leiva: reports no disclosures. Álvaro Carbayo: reports no disclosures. Ana Vesperinas: reports no disclosures. Luis Querol received research grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Ministry of Economy and Innovation (Spain), CIBERER, Fundació La Marató, GBS‐CIDP Foundation International, UCB and Grifols. LQ received speaker or expert testimony honoraria from CSL Behring, Novartis, Sanofi‐Genzyme, Merck, Annexon, Alnylam, Biogen, Janssen, Lundbeck, ArgenX, UCB, Dianthus, LFB, Avilar Therapeutics, Octapharma and Roche. LQ serves on the Clinical Trial Steering Committee for Sanofi Genzyme and was Principal Investigator for UCB's CIDP01 trial. Janina Turon‐Sans: reports no disclosures. Ricard Rojas‐García: reports no disclosures. Eduard Gallardo: reports no disclosures. Mar Pujades‐Rodriguez: is employed by UCB Pharma. Elena Cortés‐Vicente has received public speaking honoraria and compensation for advisory boards and/or consultation fees from UCB, Argenx, Alexion, Janssen and Lundbeck. Ogilvy Health provided editorial assistance, which was funded by UCB Pharma.

Supporting information

Table S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients and their relatives for their support of this study. David Reyes‐Leiva, Álvaro Carbayo, Ana Vesperinas, Ricard Rojas‐García, Luis Querol, Janina Turon‐Sans, Montse Olivé, Eduard Gallardo and Elena Cortés‐Vicente are members of the European Reference Network for Neuromuscular Diseases (EURO‐NMD), XUECs (Networks of Specialized Centers of Excellence in Minority Health of Catalonia) and work in a reference center for rare neuromuscular diseases (CSUR).

Reyes‐Leiva D, Carbayo Á, Vesperinas‐Castro A, et al. Persistent symptoms, exacerbations and drug side effects despite treatment in myasthenia gravis. Eur J Neurol. 2025;32:e16463. doi: 10.1111/ene.16463

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available on request to any qualified investigator.

REFERENCES

- 1. Drachman DB, de Silva S, Ramsay D, Pestronk A. Humoral pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;505:90‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(10):1023‐1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boscoe AN, Xin H, L'Italien GJ, Harris LA, Cutter GR. Impact of refractory myasthenia gravis on health‐related quality of life. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2019;20(4):173‐181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris L, Graham S, MacLachlan S, Exuzides A, Jacob S. A retrospective longitudinal cohort study of the clinical burden in myasthenia gravis. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landfeldt E, Pogoryelova O, Sejersen T, Zethraeus N, Breiner A, Lochmüller H. Economic costs of myasthenia gravis: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(7):715‐728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phillips G, Abreu C, Goyal A, et al. Real‐world healthcare resource utilization and cost burden assessment for adults with generalized myasthenia gravis in the United States. Front Neurol. 2022;12:809999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ting A, Story T, Lecomte C, Estrin A, Syed S, Lee E. A real‐world analysis of factors associated with high healthcare resource utilization and costs in patients with myasthenia gravis receiving second‐line treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2023;445:120531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wolfe GI, Kaminski HJ, Cutter GR. Randomized trial of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):2006‐2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cortés‐Vicente E, Álvarez‐Velasco R, Pla‐Junca F, et al. Drug‐refractory myasthenia gravis: clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcome. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(2):122‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Illa I, Diaz‐Manera J, Rojas‐Garcia R, et al. Sustained response to rituximab in anti‐AChR and anti‐MuSK positive myasthenia gravis patients. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;201–202:90‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dalakas MC. Immunotherapy in myasthenia gravis in the era of biologics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(2):113‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piehl F, Eriksson‐Dufva A, Budzianowska A, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab for new‐onset generalized myasthenia gravis: the RINOMAX randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(11):1105‐1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanders DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87(4):419‐425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America , Jaretzki A, Barohn RJ, et al. Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Neurology. 2000;55(1):16‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, Foster B, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ. Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology. 1999;52(7):1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Howard JF, Freimer M, O'Brien F, et al. QMG and MG‐ADL correlations: study of eculizumab treatment of myasthenia gravis: short reports. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(2):328‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The REGAIN Study Group , Vissing J, Jacob S, Fujita KP, O'Brien F, Howard JF. ‘Minimal symptom expression’ in patients with acetylcholine receptor antibody‐positive refractory generalized myasthenia gravis treated with eculizumab. J Neurol. 2020;267(7):1991‐2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cortés‐Vicente E, Gallardo E, Álvarez‐Velasco R, Illa I. Myasthenia gravis treatment updates. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2020;22(8):24. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silvestri NJ, Wolfe GI. Treatment‐refractory myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2014;15(4):167‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mantegazza R, Antozzi C. When myasthenia gravis is deemed refractory: clinical signposts and treatment strategies. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:175628561774913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schneider‐Gold C, Hagenacker T, Melzer N, Ruck T. Understanding the burden of refractory myasthenia gravis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:175628641983224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Q, Ge H, Gui M, et al. Polymorphisms in drug metabolism genes predict the risk of refractory myasthenia gravis. Ann Transl Med. 2022;10(21):1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Howard JF, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, et al. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody‐positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):976‐986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Howard JF, Bril V, Vu T, et al. Safety, efficacy, and tolerability of efgartigimod in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis (ADAPT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(7):526‐536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bril V, Drużdż A, Grosskreutz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of rozanolixizumab in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis (MycarinG): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, adaptive phase 3 study. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(5):383‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris L, Allman PH, Sheffield R, Cutter G. Longitudinal analysis of disease burden in refractory and nonrefractory generalized myasthenia gravis in the United States. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;22(1):11‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee I, Leach JM, Aban I, McPherson T, Duda PW, Cutter G. One‐year follow‐up of disease burden and medication changes in patients with myasthenia gravis: from the mg patient registry. Muscle Nerve. 2022;66(4):411‐420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xin H, Harris LA, Aban IB, Cutter G. Examining the impact of refractory myasthenia gravis on healthcare resource utilization in the United States: analysis of a Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America patient registry sample. J Clin Neurol. 2019;15(3):376‐385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahic M, Bozorg AM, DeCourcy JJ, et al. Physician‐reported perspectives on myasthenia gravis in the United States: a real‐world survey. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(4):1535‐1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mahic M, Bozorg A, Rudnik J, Zaremba P, Scowcroft A. Treatment patterns in myasthenia gravis: a United States health claims analysis. Muscle Nerve. 2023;67(4):297‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahic M, Bozorg A, Rudnik J, Zaremba P, Scowcroft A. Healthcare resource use in myasthenia gravis: a US health claims analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2023;16:175628642211503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mevius A, Jöres L, Biskup J, et al. Epidemiology and treatment of myasthenia gravis: a retrospective study using a large insurance claims dataset in Germany. Neuromuscul Disord. 2023;33(4):324‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Antonini G, Habetswallner F, Inghilleri M, et al. Real world study on prevalence, treatment and economic burden of myasthenia gravis in Italy. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e16367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dewilde S, Philips G, Paci S, et al. Patient‐reported burden of myasthenia gravis: baseline results of the international prospective, observational, longitudinal real‐world digital study MyRealWorld‐MG. BMJ Open. 2023;13(1):e066445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aragonès JM, Altimiras J, Roura P, et al. Prevalencia de miastenia gravis en la comarca de Osona (Barcelona, Cataluña). Neurologia. 2017;32(1):1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available on request to any qualified investigator.