Abstract

Background

Reprogramming of cellular metabolism is a pivotal mechanism employed by tumor cells to facilitate cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation, thereby propelling the progression of cancer. A comprehensive analysis of the transcriptional and metabolic landscape of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) at high resolution could greatly enhance the precision of management and therapeutic strategies for this malignancy.

Methods

The Air-flow-assisted Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectro-metric Imaging (AFADESI-MSI) and Spatial Transcriptomics techniques (ST) were employed to investigate the metabolic and transcription profiles of CSCC and normal tissues. For clinical validation, the expression of ASCT2(Ala, Ser, Cys transporter 2) was assessed using immune histochemistry in 122 cases of cervical cancer and 30 cases of cervicitis.

Results

The AFADESI-MSI findings have revealed metabolic differences among different CSCC patients. Among them, the metabolic pathways of glutamine show more significant differences. After in situ detection of metabolites, the intensity of glutamate is observed to be significantly higher in cancerous tissue compared to normal tissue, but the intensity is not uniform. To elucidate the potential factors underlying alterations in glutamine metabolism across tissues, we employ ST to quantify mRNA levels. This analysis unveils significant perturbations in glutamine metabolism accompanied by extensive heterogeneity within cervical cancer tissues. After conducting a comprehensive analysis, it has been revealed that the differential expression of ASCT2(encoded by SLC1A5) in distinct regions of cervical cancer tissues plays a pivotal role in inducing heterogeneity in glutamine metabolism. Furthermore, the higher the expression level of ASCT2, the higher the intensity of glutamate is in the region. Further verification, it is found that the expression of ASCT2 protein in CSCC tissues is significantly higher than that in normal tissues (105/122, 86.07%).

Conclusions

This finding suggests that the variation in glutamine metabolism is not uniform throughout the tumor. The differential expression of ASCT2 in different regions of cervical cancer tissues seems to play a key role in causing this heterogeneity. This research has opened up new avenues for exploring the glutamine metabolic characteristics of CSCC which is essential for developing more effective targeted therapies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13275-6.

Keywords: Cervical carcinoma, Glutamine metabolism, Heterogeneity, AFADESI-MSI, ST

Background

Cervical carcinoma(CC) ranks as the fourth most prevalent malignancy impacting women’s health, with an estimated 660,000 new cases and 350,000 fatalities reported globally in 2022, an escalation in the global ranking of cervical cancer mortality from fourth to third place [1]. The presence of molecular and metabolic heterogeneity in patients with tumors has been recognized [2]. Molecular and Metabolism Heterogeneity is generally considered to be a key factor in deaths, treatment failure, and drug resistance for cancer patients [3].

Metabolic reprogramming, a hallmark of cancer cells, is a crucial process by which malignant cells ensure an ample supply of proteins, nucleotides, and lipids to sustain rapid growth and proliferation [4, 5]. Glutamine metabolism has garnered significant attention as a promising therapeutic target, primarily due to its pivotal role in fueling cancer cell growth and proliferation. Glutamine plays a pivotal and multifaceted role in cancer cells, serving as both a nitrogen source for amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis, as well as a carbon source for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and lipid biosynthesis pathway [6]. Consequently, cancer cells exhibit an inherent reliance on glutamine. Glutamine metabolism and closely linked metabolic networks involving glutamine transporters(ASCT2), glutaminase(GLS/GLS2), and aminotransferase(GPT, GOT1/2, PSAT1, GLUD1), are essential for cancer cell survival [7].

However, the high-throughput discovery of tumor-associated metabolic alterations at both the metabolite and metabolic enzyme levels is still a great challenge [8]. The findings of Li et al. provide valuable resources for elucidating the intra-tumoral heterogeneity of cervical cancer using single-cell transcriptomics analysis [9]. However, their research lost spatial localization information. The fundamental mechanisms underlying the interactions of tumor-associated cell subsets, including their spatial distribution and functional relationships, remain unresolved. The integration of spatial metabolomics and spatial transcriptomics has revolutionized researchers’ comprehension of cancer. The analysis of spatially heterogeneous functional metabolites and their associated genes will provide crucial in situ biochemical information for tissue-specific molecular histology and pathology, thereby facilitating a more accurate understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying diseases.

Our previous studies have demonstrated an upregulation of fatty acid synthesis within tumor tissues through the AFADESI-MSI [10]. This study reveals the accumulation of glutamate in cervical cancer tissues. This study has also revealed heterogeneity in glutamine metabolism among tumor tissues from different patients and within distinct regions of the same patient’s tumor. To clarify the cause of glutamine accumulation.ST analysis showed that compared with GLS/GLS2, GPT, GOT1/GOT2, PSAT1, and GLUD1, the average expression level and percentage of ASCT2 in tumor tissues of 3 patients were higher, with significantly higher expression levels of ASCT2 observed in CSCC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. Meanwhile, there is heterogeneity in ASCT2 expression among different CSCC patients or within distinct tumor regions of the same patient. It is worth noting that the regions exhibiting high ASCT2 expression coincided with the areas of glutamate accumulation. To further elucidate the correlation between ASCT2 expression and the progression of cervical cancer. Our research group collected clinical paraffin specimens from patients who conducted immunohistochemical analysis and found that ASCT2 expression in cervical cancer tissues was significantly up-regulated. In this study, AFADESI-MSI and ST were combined for the first time facilitating the identification of heterogeneous cancer cell populations in cervical cancer and elucidation of their catabolic characteristics. The spatial integrity of tissue domains is maintained, facilitating the integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic data with histological tissue images to visualize gene expression patterns across the tumor. Cervical samples were collected to decode the metabolic pathways of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) would yield novel insights into the management of advanced CSCC, potentially expediting the eradication of cervical cancer.

Methods

The overall study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of AFADESI-MSI and ST experiments applied to cervical tissues

Patients and samples

Approval to perform metabolome and transcriptome analysis on tissue samples was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University. Cervical specimens were collected from 3 patients including central cancer tissues (CSCC1), distal noncancerous tissue (NC1) (collected at 5 cm away from the cancer tissue) from the No.1 patient, and peripheral cancer tissues, adjacent noncancerous tissues (NC2-CSCC2) from No.2 patient, and central cancer tissues (CSCC3) from No.3 patient.

Fixation, staining, and imaging

The sectioned slides were hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining. Images were captured using a digital slice scanner (Hamamatsu, San Jose, CA, USA) to facilitate histopathological evaluation. Diagnoses were made by two experienced pathologists on material using HE staining.

AFADESI-MSI analysis and data processing

The AFADESI-MSI analysis was performed using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) in both positive and negative-ion modes, covering an m/z range of 70–1,000 with a nominal mass resolution of 70,000. The MSI experiments were conducted by continuously scanning the tissue surface in the x-direction at a constant rate of 200 μm/s, with a vertical step of 200 μm separating adjacent lines in the y-direction. Precise extraction of region-specific mass spectrometry (MS) profiles was achieved through the alignment of high-spatial-resolution hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images. The discriminative endogenous molecules from distinct tissue microregions were identified using a supervised statistical analytical approach known as partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). The statistical software SPSS 21.0 was employed for conducting two-tailed t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Tissue preparation for spatial transcriptomic experiment

The tissue block was rinsed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), immersed in a pre-cooled tissue storage solution (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), and subsequently embedded in a pre-cooled optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (Sakura, USA).

Reverse transcription, spatial library preparation, and sequencing

Briefly, sections with a thickness were obtained from each OCT-embedded sample for total RNA extraction. The RNA integrity number (RIN) was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, USA). Only samples with a minimum RIN value of 7 were deemed eligible for inclusion in the transcriptomic study. All samples exhibited RIN values ranging from 7 to 10. After confirming the identities of cDNA amplification products, a sequencing library was constructed utilizing a Library Construction Kit provided by 10 × Genomics. The sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq 3000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using a 150 bp paired-end run conducted by Quick Biology (Pasadena, CA, USA). The SAV (Illumina) platform was employed for data quality assessment. The demultiplexing process was performed using the Bcl2fastq2 v 2.17 software (Illumina).

Quantitative analysis of glutamine (Gln) in the cellular supernatant

Recover the supernatant from the cells and prepare control wells without any sample or enzyme substrate, following the same subsequent steps. Additionally, set up standard wells and sample wells for Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) analysis (Mlbio, Shanghai, China). Refrigerate the plate at 37 °C for 30 min after applying a sealing film to ensure proper incubation. Be careful when removing the sealing film, discarding the liquid, shaking off any excess, and adding enough washing buffer to each well. Allow it to stand for 30 s before discarding. Repeat this process five times and then blot dry. Add 50 μl of enzyme–substrate to each well, excluding the blank well. Add 50 μl of Reagent A to each well, followed by the addition of 50 μl of Reagent B with gentle and thorough mixing. Subsequently, incubate the mixture at a temperature of 37℃ in a light-restricted environment for 10 min. The absorbance (optical density, OD) of each well was measured sequentially at a wavelength of 450 nm.

RNA sequencing analysis

The Space Ranger software pipeline (version 1.2.0) provided by 10 × Genomics was utilized for processing Visium spatial RNA-seq output and brightfield microscope images, enabling tissue detection, read alignment using the STAR2 aligner, generation of feature spot matrices, execution of clustering and gene expression analysis, as well as placement of spots in spatial context on the slide image. The unique molecular identifier (UMI) count matrix was processed by the research group using the R package Seurat3 (version 3.2.0). The identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed using the Find Markers function from the Seurat3 package. A significance threshold was set at P value < 0.05 and |log2foldchange|> 0.58 to determine significant differential expression. The enrichment analysis of DEGs was conducted using R based on the hypergeometric distribution, separately for GO and KEGG pathways.

Immunohistochemical scoring

The expression of ASCT2 was assessed in a blinded model using a compound microscope by two independent pathologists. In brief, the images were evaluated based on the intensity of staining as follows: a score of 3 represented dark brown staining, a score of 2 indicated brown madder staining, a score of 1 denoted faint yellow staining, and a score of 0 referred to negative staining. Subsequently, the images were evaluated according to the proportion of positive cells among total tumor cells: a score of 4 corresponded to ≥ 76%, a score of 3 ranged from 51 to 75%, a score of 2 encompassed an interval between 11 and 50%, while a score of 1 accounted for percentages ranging from 1% to10%. The scores for each slide were aggregated to generate a final score (Final score = staining depth score × number of positive cells score): strong positive (+ + +): ≥ 5 points; moderate positive (+ +): 4 points; weakly positive ( +): 3 points; negative (-): < 3 points.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), and GraphPad PRISM software (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was employed to compare between the two groups. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Cervical squamous carcinoma driven by AFADESI-MSI exhibits heterogeneity in its characterization

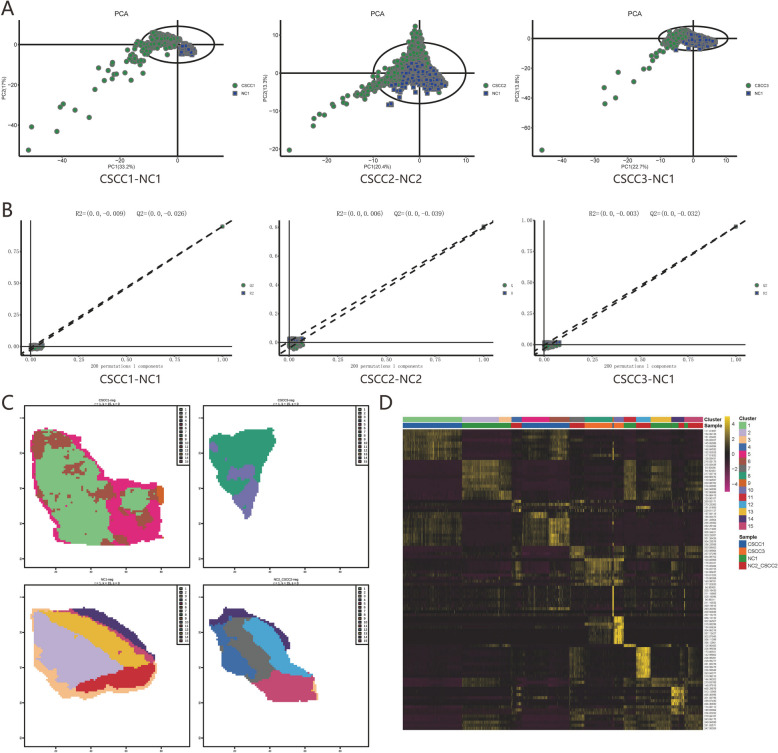

The human cervical squamous carcinoma tissue section can be divided into central cancer tissues (CSCC1; CSCC3), marginal cancer tissue (CSCC2), and cervix uteri normal tissues (NC1; NC2), where CSCC2 and NC2 are shown in the same section. Regions were labeled as either: normal squamous epithelium, invasive cancer, or tumor stroma tissues. The spatially resolved AFADESI-MSI technique was used to map the differential metabolites in the tissues of cervical cancer patients. Unsupervised PCA was employed to evaluate the overall distribution among samples and the stability of the entire analysis process, performing principal component analysis on the metabolites. It was found that the cancer and adjacent tissues of the 3 pairs of samples included in this study were relatively distant from each other on the score map, and the difference was significant (Fig. 2A). Orthogonal partial least squares (OPLS-DA) were employed to discern the overall metabolic profile disparities between cancerous and adjacent tissues. The corresponding OPLS-DA model was constructed to derive the R2 and Q2 values, followed by linear regression analysis utilizing R2Y and Q2Y from the original model. The arrangements of CSCC1 and NC1 (Q2 = −0.026), CSCC2 and NC2(Q2 = −0.039), and CSCC3 and NC1 (Q2 = −0.032) tissues exhibited significant differences in metabolites (Fig. 2B). These findings collectively affirm the reliability of the three tissue sample models and suggest discernible disparities among their respective metabolite profiles. The visualization of the overall expression level of the clustering results indicates that tumor cells exhibit intra-tumor heterogeneity and patient heterogeneity, with regions of the same color showing more similar overall expression levels (Fig. 2C). The heat map exhibited different accumulations of metabolites in different clusters (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

AFADESI-MSI exhibits heterogeneity A: Unsupervised PCA was employed to evaluate the overall distribution. B Orthogonal partial least squares (OPLS-DA) were employed to discern the overall metabolic profile disparities. C The visualization of the overall expression level, with regions of the same color showing more similar overall expression levels. D The top characteristic metabolites of the Cluster were presented in the heat map. The color from purple to golden yellow indicates that the expression abundance of the substance is from low to high, that is, golden yellow indicates the higher expression abundance of differential metabolites

Tumor-associated metabolic pathway discovery

The expression levels of all significantly different metabolites were subjected to Hierarchical Clustering to more effectively demonstrate the relationship among samples and the variations in metabolite expression across different samples. These results showed an accumulation of glutamate(M/Z:146.04592) in the tumor tissues of all 3 patients (Fig. 3A). The discriminative metabolites were subjected to metabolic pathway matching analysis in the KEGG database, facilitating the identification of perturbed metabolic pathways. Under the condition of p < 0.01, metabolic pathways were significantly dysregulated and involved in glutamine and glutamate metabolism, proximal tubule bicarbonate reclamation, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, pentose phosphate pathway, and so on. The enrichment analysis reveals that the metabolic pathways of glutamine and glutamate exhibit significant differences in CSCC1 and CSCC3, while also displaying high significance in CSCC2 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, the enrichment analysis also indicated metabolic differences among different patients. The study findings have revealed multiple metabolic abnormalities in CSCC, including a significant disruption in glutamine metabolism.

Fig. 3.

Metabolic Pathway Discovery A: Hierarchical Clustering of all significantly different metabolite expression levels. B Enrichment analysis of differential metabolites was performed. The red line indicates a p-value of 0.01, and the blue line indicates a p-value of 0.05

In situ validation of crucial metabolites

Tissue-specific detection of glutamine (Gln) metabolic disorders can be achieved through in situ AFADESI-MSI analysis. After performing tissue MSI, the MS image was integrated with microscopy to create a microscopy-MSI overlay image that combines the spatial resolution of microscopy with the chemical signatures of MSI in an integrated whole. Precise extraction and visualization of mass spectra specific to cancer, epithelium, and tumor stroma were achieved based on the overlay image obtained from microscopy-MSI analysis. The utilization of an image overlay facilitates the precise identification of microregions corresponding to each specific cell type, thereby enabling accurate extraction of mass spectra. The MS image is composed of consecutive pixels, each representing the relative content of metabolites in the corresponding region. In this study, we calculated the Glu intensity on a pixel-by-pixel basis to construct an MS image. The ion-intensity ratio in the cancer tissue (red region) is suggested to be higher than that in the normal tissue (green region). The ion intensity of glutamate was observed to be significantly higher in cancerous tissue compared to normal tissue (Fig. 4). Moreover, ionic strength-based mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) may provide a diagnostic approach for CSCC. The findings were validated in cellular models. The glutamine consumption in SiHa and HeLa (cervical cancer cell) cell media exhibited a significant increase when compared to H8(normal cervical epithelium) (Figure S1).

Fig. 4.

Enhanced Validation of Essential Metabolites in situ A: Microscopy-MSI overlay. B: Representative mass spectra of cancer tissues. The H&E image was taken from [10]

Spatial transcriptomic characterization of CSCC

The spatial transcription technology was applied to determine the mRNA levels, aiming to elucidate the underlying factors contributing to variations in glutamine metabolism across previously mentioned tissues. Transporter and pivotal enzymes establish connections and regulate intricate metabolic reactions, thereby being consistently acknowledged as promising targets for anticancer drug development. Therefore, spatial transcriptomics techniques have been employed to investigate the in situ transcriptional profile of transporters and enzymes involved in glutamine metabolism.

Using UMAP cluster display, it was found that cervical cancer patients or different tumor regions within the same patient also exhibited heterogeneity (Figure S2). Scmetabolism analysis was performed on different cell types in the tissues. Interestingly, the Reactome analysis unveiled a significant involvement of glutamine metabolism in cervical cancer tissues, demonstrating extensive heterogeneity. Specifically, differences in glutamine metabolism were found between normal cervical epithelial tissues (Fig. 5A) and tumor stroma (Fig. 5B) from different patients and tumor tissues (Fig. 5C). The researchers were excited because the results of the reactom analysis were highly consistent with the KEGG results (Fig. 5D). Both the AFADESI-MSI and ST Reactome analyses reveal altered glutamine metabolism in cervical cancer patients’ tissues, indicating a reprogrammed metabolic state.

Fig. 5.

Tissue heterogeneity in patients with cervical cancer was analyzed by ST. A-C Reactom analyses (A: Between normal epithelial tissues; B: Stromal of tumor in different patients; C: Between tumor tissues of different patients). D: KEGG analyses

In situ validation of key genes involved in glutamine metabolism

The catabolism of glutamine to glutamate in tumors occurs via the catalytic action of GLS. Glutamate is converted into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG). The conversion of glutamate to α-KG is catalyzed by either glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD) or aminotransferase enzymes (GPT, GOT1/GOT2, PSAT1). To better understand the differences in glutamine metabolism among different cervical cancer tissues, mentioned above gene expression analyses were conducted. Expression-based clustering was employed as a framework to investigate the heterogeneity within and between patients in the dataset. The findings revealed distinct expression patterns of glutamine-related genes among individual patients, which could contribute to the development of more sophisticated and personalized therapeutic protocols.

Spatial transcriptome analysis showed that compared with GLS/GLS2, GPT, GOT1/GOT2, PSAT1, and GLUD1, the average expression level and percentage of ASCT2 (SLC1A5) in tumor tissues of 3 patients were higher (Fig. 6A), with significantly higher expression levels of ASCT2 (SLC1A5) observed in cervical squamous cell carcinoma tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, there was significant variation in the expression of ASCT2 among tumor cell clusters and interstitial tissues of different patients, as well as within tumor tissues of the same patient (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, these findings indicate a significant spatial heterogeneity of this gene. The exciting part is that the regions with high ASCT2 expression are highly consistent with the regions exhibiting high levels of glutamine metabolism. GLS (Figure S3A) expression in CSCC1 was significantly increased. Notably, in two other pairs of tissues (NC2-CSCC2; NC1-CSCC3), the expression of GLS2 (Figure S3C) in tumor tissues was significantly higher than that in normal tissues. However, from the spots, the expression degree of GLS was slightly higher than that of GLS2, indicating that GLS may played a more significant role than GLS2 in patients with cervical cancer. Transaminases, GOT1/2 (Figure S4), GLUD1, and PSAT1(Figure S5A-D) also play an important role in cervical cancer patients. However, their differences in expression were always not statistically significant in one of the pairs of patients. Aminotransferase GPT (Figure S5E-F) is almost not expressed in cervical cancer and adjacent tissues. In conclusion, ASCT2 plays a key role in the process of glutamine metabolism in cervical cancer. The differential expression of ASCT2 in distinct regions of cervical cancer tissue appears to exert a pivotal role in inducing heterogeneity within glutamine metabolism.

Fig. 6.

In situ validation of key genes involved in glutamine metabolism. A: Expression of glutamine metabolism-related genes in three tumor tissues. B: ASCT2 spatial feature and violin plot; C ASCT2 violin plot between different tissues (CSCC1,2,3,4 refer to different clusters in the CSCC1 tumor tissue)

The relationship between the expression level of ASCT2 protein and the clinicopathological parameters

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the role played by the ASCT2 protein in patients diagnosed with cervical cancer. The research group collected paraffin tissue samples from 122 patients diagnosed with cervical cancer and 30 patients diagnosed with cervicitis. The patients consist of 110 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, 4 cases of adenocarcinoma, and 8 cases of adeno-squamous carcinoma. Cervical cancer patients’ mean age ± standard deviation was 43.00 ± 5.66. In addition, the rate of lymph node metastasis was 23.77%. The 122 patients were classified according to AJCC as follows: pathological stage T1, 10 (8.20%); pathological stage T2, 64 (52.50%); and pathological stage T3, 48 (39.34%). Interestingly, IHC analysis indicated that the positive immunostaining rate for ASCT2 in CSCC tissue was significantly higher than in cervicitis tissues (Fig. 7A). The IHC assay revealed a significant up-regulation of ASCT2 in cancerous tissue compared to normal tissue (105/122, 86.07%), which is consistent with the findings from MSI and ST analysis. The statistic intimated that the expression status of ASCT2 was closely associated with the age of patients, degree of differentiation, AJCC stage, infiltration, and lymphatic metastasis (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

ASCT2 protein expression A: ASCT2 protein expression in cervical cancer tissues and normal cervical epithelial tissues by IHC. B: Correlation between ASCT2 expression in cervical cancer tissue and pathological parameters of patients. ****:P < 0.0001

Discussion

Despite the effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy as a therapeutic measure, is characterized by notorious resistance to current therapies attributed to inherent tumor heterogeneity [11]. Therefore, extensive and in-depth research on the heterogeneity of cervical cancer patients is necessary to obtain personalized and precise treatment [12]. In this study, we present a comprehensive characterization of the transcription and metabolism landscape in cervical carcinoma (CSCC) using AFADESI-MSI and ST technology at a high resolution. These findings have significant implications for precision management and treatment strategies in cervical cancer.

Reprogramming of metabolism represents the cancer-associated metabolic alterations that occur during tumorigenesis and is a novel hallmark of cancer [13]. Reprogramming of glutamine metabolism is equally crucial for tumor survival, and there exists competition among these cells in the TME to acquire glutamine uptake. The results demonstrate a significant accumulation of glutamate in cervical cancer tissues. This indicates that cervical cancer cells require a significant amount of glutamine for energy during the rapid proliferation process. Glutamine addiction is consistently observed in numerous malignant tumor cells [4]. For instance, breast cancer [14], lung cancer [15], renal cancer [16], and Pancreatic cancer [17] clear cell renal cell carcinomas [18] exhibit addiction to glutamine. Glutamine metabolism plays a pivotal role in the regulation of tumorigenesis and progression, thus offering promising avenues for targeted therapy through the inhibition of intracellular glutamine metabolic enzymes and transporters [19]. However, distinct patterns of glutamine can be observed among different cancer subtypes within tumors originating from a specific organ. ASCT2 transport is critical only for triple-negative basal-like breast cancer cell growth compared with minimal effects in luminal breast cancer cells [20]. However, mapping the distribution of metabolites remains a challenge due to the complexity and heterogeneity of tissue samples. Therefore, AFADESI-MSI is introduced in this study. This method is non-targeted, and highly sensitive, with wide coverage and high chemical specificity, enabling researchers to visualize the spatial distribution of multiple metabolites in their original state [21]. After overlaying the microscopy-MSI image, glutamate was found to be significantly upregulated in the carcinoma region compared to normal epithelium and tumor stroma.

Heterogeneity manifests between distinct regions within the same tumor. In the study of lung cancer, there are significant differences in cell types and histological structures [22]. Meanwhile, prostate cancer exhibits heterogeneity from molecular perspectives [23]. It is worth noting that in this study, the results showed heterogeneity in glutamine metabolism among tumor tissues from different patients and within different tumor regions of the same patients. This finding further illustrates the presence of distinct primary cervical cancers within an individual patient, highlighting their coexistence. We wondered what the cause of tumor heterogeneity was. Tumors originating from the same source but driven by distinct oncogenes may exhibit divergent metabolic profiles. The investigation of this aspect will continue to be the primary focus of our forthcoming research. According to literature reports, in contrast to MFC-induced liver tumors, MET-induced liver tumors exhibit downregulation of GLS expression while upregulating GLUL and accumulating glutamine [24]. Furthermore, many other factors can regulate glutamine metabolism such as the activity c-Jun [25], Rb [26], GLUL acetylation levels [27], and others. Collectively, the intricate and heterogeneous array of molecular alterations presents significant challenges in both the diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer. However, advancements in our comprehension of intra-tumoral heterogeneity will enable us to navigate these for translational research, and ultimately enhance.

Metabolites are the immediate byproducts of metabolic enzymes, and their tissue levels can serve as indicators of enzyme capacities [28]. Characterization of metabolites associated with the metabolic pathway in cancer tissue offers valuable insights for the discovery of tumor-associated metabolic enzymes. The spatial transcriptome technique was therefore employed to detect the transcription of genes encoding relevant metabolic enzymes in situ. The transportation of glutamine (Gln) across the cell membrane is facilitated by amino acid transporters, specifically ASCT2 [29]. Upon entering the cytoplasm, it undergoes lysis mediated by GLS, resulting in the production in the production of glutamate and ammonia (NH3). Mitochondrial glutaminase plays a pivotal role in catalyzing the conversion of glutamine to glutamate, making it a crucial enzyme in the process of glutaminolysis [30]. Glutamate can undergo further catabolism through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, involving its conversion to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG). The formation of α-KG can be catalyzed by either glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD) or aminotransferases. For the study of glutamine, many scholars primarily focus on the effects of ASCT2 and GLS on tumor patients. ASCT2 plays a pivotal role in regulating cellular energetics [31]. The dysregulation of this process affects various functional factors, ranging from intracellular energy metabolism to neurotransmission, thereby inducing a metabolic cascade. The UMAP clustering and ST analysis in this study revealed significant heterogeneity. This research suggested that there were significantly higher expression levels of ASCT2 were observed in CSCC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. Furtherly, ST analysis also showed that compared with GLS/GLS2, GPT, GOT1/GOT2, PSAT1, and GLUD1, the average expression level and percentage of ASCT2 (encoded by SLC1A5 gene) in tumor tissues of 3 patients were higher. Interestingly, two distinct subtypes of glutaminase have been identified in mammals: the “kidney-type” GLS1 and the “liver-type” GLS2 [32]. The expression level of GLS (GLS1) in CSCC1 was significantly higher than that in NC1, with statistical significance, as revealed by this study. This is consistent with literature reports. The expression level of GLS2 was relatively high in the remaining 2 pairs of tumor tissues; however, it exhibited an overall low abundance. This observation deviates slightly from previous findings. Next, we need to further expand the sample size and conduct in-depth research on both GLS1 and GLS2. Although there is some comprehension regarding ASCT2 and GLS, the conventional study approach fails to retain cellular spatial information dissociation, which is crucial for comprehending the cellular microenvironment and cell–cell interactions. After further spatial analysis, it was found that there is heterogeneity in the expression of ASCT2 and GLS among different cervical cancer patients or within different tumor regions of the same patient. Reactom analysis revealed heterogeneity in glutamine metabolism among different cervical cancer tissues. So cervical cancer is also a dynamic disease. Throughout the progression of the disease, cancers tend to exhibit an increased level of heterogeneity. Due to this inherent heterogeneity, the bulk tumor may contain a diverse collection of cells that harbor distinct molecular signatures and exhibit varying degrees of sensitivity toward therapeutic interventions. Accurate assessment of tumor heterogeneity is crucial for advancing research.

In this study, the experimental result showed that ASCT2 is a potential predictor and therapeutic marker of cervical cancer. To complement this, we directly demonstrated the higher expression of ASCT2 in CSCC cells by performing IHC for 122 cases. The higher expression status of ASCT2 was closely associated with the age of patients, degree of differentiation, AJCC stage, infiltration, and lymphatic metastasis. These results suggest that ASCT2 plays an important role in cervical cancer patients.

Our study provides clinical evidence indicating aberrant glutamate accumulation in cervical cancer tissue, primarily attributed to upregulated expression of ASCT2, however, it is subject to certain limitations. Although this study comprehensively investigated the characteristics of cervical cancer, encompassing metabolism, transcription, and protein analysis, it is important to note that the samples were predominantly sourced from specific regions and may not be fully representative of the broader population. However, this effect was minimized through meticulous experimental design and thorough data analysis. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the overexpression of ASCT2 in various malignancies. Such as, Lung cancer [33], Breast Cancer [34], Pancreatic cancer [35], Epithelial ovarian cancer [36], and so forth. However, the regulatory mechanism governing ASCT2 activity in cervical cancer cells remains elusive. In future investigations, our research group will delve deeper into elucidating the underlying factors contributing to heterogeneity in ASCT2 expression among cervical cancer patients and unraveling the precise regulatory mechanisms involved. These endeavors will establish a robust foundation for precise treatment strategies and improved prognostic outcomes in cervical cancer.

Conclusion

This comprehensive analysis unveiled significant perturbations in glutamine metabolism accompanied by extensive heterogeneity within cervical cancer tissues. The differential expression of ASCT2 in distinct regions of cervical cancer tissue appears to exert a pivotal role in inducing heterogeneity within glutamine metabolism. The IHC verification results demonstrate a significantly elevated expression level of ASCT2 in CSCC tissue compared to normal tissue, consistent with the findings obtained from intensity mass spectrometry and ST. Overall, this research has opened up new avenues for exploring the glutamine metabolic characteristics of CSCC and holds promise for future advancements in CSCC treatment. In future studies, it is needed to expand the patient sample size and comprehensively investigate the potential factors contributing to the heterogeneity of ASCT2 expression in cervical cancer patients in cellular, animal, and organoid models. These efforts will enable us to unravel the precise regulatory mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Glutamine content in cell media. **:P<0.01.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2. UMAP dimensionality reduction clustering result map A: The horizontal and vertical coordinates of the Figure represent the first and second principal components of UMAP dimensionality reduction respectively. Each point in the Figure represents a Spot, and the spots of different groups are distinguished by different colors. B: The Figure reflects the specific distribution of different groups in sample space slice positions, and the colors correspond to the left Figure.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure S3. GLS/GLS2 spatial transcriptome expression patterns A: GLS spatial feature and violin plot. B: GLS violin plot between different tissues. C: GLS2 spatial feature and violin plot. D: GLS2 violin plot between different tissues.

Supplementary Material 4: Figure S4. GOT1/ GOT2 spatial transcriptome expression patterns A: GOT1 spatial feature and violin plot. B: GOT1 violin plot between different tissues. C: GOT2 spatial feature and violin plot. D: GOT2 violin plot between different tissues.

Supplementary Material 5: Figure S5. GLUD1, PSAT1, and GPT spatial transcriptome expression pattern A: GLUD1 spatial feature and violin plot. B: GLUD1 violin plot between different tissues. C: PSAT1 spatial feature and violin plot. D: PSAT1 violin plot between different tissues. E: GPT spatial feature and violin plot. F: GPT violin plot between different tissues.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CSCC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- ASCT2

Ala, Ser, Cys transporter 2

- GLS

Glutaminase

- GLUL

Glutamate-Ammonia Ligase

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- AFADESI-MSI

Air-flow-assisted Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectro-metric Imaging

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- Gln

Glutamine

- UMAP

Uniform manifold approximation and projection

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- α-KG

α-Ketoglutarate

- GLUD

Glutamate dehydrogenase

Authors’ contributions

QL and JZ Data generation and analyses. QL Statistical analyses. GA and AH Results interpretation. Writing—review & editing: All authors. Funding acquisition: AH.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China” (No. 2022D01D13) and the Key Research and Development Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China (2022B03019-1–1). We thank OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for the detection of metabolite and Whole transcriptome used in this study.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [GEO] repository, [PRJNA1029249]”.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the local ethical committee of Xinjiang Medical University, and the study was performed following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The recruited volunteers were requested to sign an informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guzalinuer Abulizi, Email: gzlnr@qq.com.

Ayshamgul Hasim, Email: axiangu@xjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra S, Goswami A, Mandal P. Molecular heterogeneity of cervical cancer among different ethnic/racial populations. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(6):2441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park JH, Pyun WY, Park HW. Cancer metabolism: phenotype, signaling and therapeutic targets. Cells. 2020;9(10):2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li T, Copeland C, Le A. Glutamine metabolism in cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1311:17–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faubert B, Solmonson A, DeBerardinis RJ. Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science. 2020;368(6487):eaaw5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin J, Byun JK, Choi YK, Park KG. Targeting glutamine metabolism as a therapeutic strategy for cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(4):706–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cluntun AA, Lukey MJ, Cerione RA, Locasale JW. Glutamine metabolism in cancer: understanding the heterogeneity. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(3):169–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonçalves AC, Richiardone E, Jorge J, Polónia B, Xavier CPR, Salaroglio IC, Riganti C, Vasconcelos MH, Corbet C, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB. Impact of cancer metabolism on therapy resistance - clinical implications. Drug Resist Updat. 2021;59:100797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C, Wu H, Guo L, Liu D, Yang S, Li S, Hua K. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals cellular heterogeneity and molecular stratification of cervical cancer. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu L, Li J, Ma J, Hasim A. Combined spatially resolved metabolomics and spatial transcriptomics reveal the mechanism of RACK1-mediated fatty acid synthesis. Mol Oncol. 2024. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Das S, Babu A, Medha T, Ramanathan G, Mukherjee AG, Wanjari UR, Murali R, Kannampuzha S, Gopalakrishnan AV, Renu K, et al. Molecular mechanisms augmenting resistance to current therapies in clinics among cervical cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2023;40(5):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia L, Oyang L, Lin J, Tan S, Han Y, Wu N, Yi P, Tang L, Pan Q, Rao S, et al. The cancer metabolic reprogramming and immune response. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li S, Zeng H, Fan J, Wang F, Xu C, Li Y, Tu J, Nephew KP, Long X. Glutamine metabolism in breast cancer and possible therapeutic targets. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;210:115464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pecchillo Cimmino T, Pagano E, Stornaiuolo M, Esposito G, Ammendola R, Cattaneo F. Formyl-peptide receptor 2 signaling redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming of lung cancer cells. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(9):1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakraborty S, Balan M, Sabarwal A, Choueiri TK, Pal S. Metabolic reprogramming in renal cancer: events of a metabolic disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1876(1):188559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Encarnación-Rosado J, Sohn ASW, Biancur DE, Lin EY, Osorio-Vasquez V, Rodrick T, González-Baerga D, Zhao E, Yokoyama Y, Simeone DM, et al. Targeting pancreatic cancer metabolic dependencies through glutamine antagonism. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(1):85–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wettersten HI, Aboud OA, Lara PN Jr, Weiss RH. Metabolic reprogramming in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(7):410–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao-Yan W, Xiao-Xia Y, Peng-Fei S, Zong-Xue Z, Xiu-Li G. Metabolic reprogramming of glutamine involved in tumorigenesis, multidrug resistance and tumor immunity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;940:175323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Geldermalsen M, Wang Q, Nagarajah R, Marshall AD, Thoeng A, Gao D, Ritchie W, Feng Y, Bailey CG, Deng N, et al. ASCT2/SLC1A5 controls glutamine uptake and tumour growth in triple-negative basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35(24):3201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He MJ, Pu W, Wang X, Zhang W, Tang D, Dai Y. Comparing DESI-MSI and MALDI-MSI mediated spatial metabolomics and their applications in cancer studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:891018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu F, Fan J, He Y, Xiong A, Yu J, Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhao W, Zhou F, Li W, et al. Single-cell profiling of tumor heterogeneity and the microenvironment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haffner MC, Zwart W, Roudier MP, True LD, Nelson WG, Epstein JI, De Marzo AM, Nelson PS, Yegnasubramanian S. Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(2):79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang X, Gan G, Wang X, Xu T, Xie W. The HGF-MET axis coordinates liver cancer metabolism and autophagy for chemotherapeutic resistance. Autophagy. 2019;15(7):1258–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma G, Liang Y, Chen Y, Wang L, Li D, Liang Z, Wang X, Tian D, Yang X, Niu H. Glutamine deprivation induces PD-L1 Expression via activation of EGFR/ERK/c-Jun signaling in renal cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2020;18(2):324–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds MR, Lane AN, Robertson B, Kemp S, Liu Y, Hill BG, Dean DC, Clem BF. Control of glutamine metabolism by the tumor suppressor Rb. Oncogene. 2014;33(5):556–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eelen G, Dubois C, Cantelmo AR, Goveia J, Brüning U, DeRan M, Jarugumilli G, van Rijssel J, Saladino G, Comitani F, et al. Role of glutamine synthetase in angiogenesis beyond glutamine synthesis. Nature. 2018;561(7721):63–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noda-Garcia L, Liebermeister W, Tawfik DS. Metabolite-enzyme coevolution: from single enzymes to metabolic pathways and networks. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87:187–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scalise M, Console L, Cosco J, Pochini L, Galluccio M, Indiveri C. ASCT1 and ASCT2: brother and sister? SLAS Discov. 2021;26(9):1148–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang D, Wang M, Huang X, Wang L, Liu Y, Zhou S, Tang Y, Wang Q, Li Z, Wang G. GLS as a diagnostic biomarker in breast cancer: in-silico, in-situ, and in-vitro insights. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1220038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Zhao T, Li Z, Wang L, Yuan S, Sun L. The role of ASCT2 in cancer: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;837:81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jo M, Koizumi K, Suzuki M, Kanayama D, Watanabe Y, Gouda H, Mori H, Mizuguchi M, Obita T, Nabeshima Y, et al. Design, synthesis, structure-activity relationship studies, and evaluation of novel GLS1 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2023;87:129266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin L, Cheng X, Wang S, Gong G, Su H, Huang H, Chen T, Damdinjav D, Dorjsuren B, Li Z, et al. Discovery of novel aminobutanoic acid-based ASCT2 inhibitors for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Med Chem. 2024;67(2):988–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyu XD, Liu Y, Wang J, Wei YC, Han Y, Li X, Zhang Q, Liu ZR, Li ZZ. Jiang JW, et al. A novel ASCT2 inhibitor, C118P, blocks glutamine transport and exhibits antitumour efficacy in breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(20):5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo HC, Park SJ, Nam M, Kang J, Kim K, Yeo JH, Kim JK, Heo Y, Lee HS, Lee MY, et al. A Variant of SLC1A5 is a mitochondrial glutamine transporter for metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Cell Metab. 2020;31(2):267–283.e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo H, Xu Y, Wang F, Shen Z, Tuo X, Qian H, Wang H, Wang K. Clinical associations between ASCT2 and p-mTOR in the pathogenesis and prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;40(6):3725–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Glutamine content in cell media. **:P<0.01.

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2. UMAP dimensionality reduction clustering result map A: The horizontal and vertical coordinates of the Figure represent the first and second principal components of UMAP dimensionality reduction respectively. Each point in the Figure represents a Spot, and the spots of different groups are distinguished by different colors. B: The Figure reflects the specific distribution of different groups in sample space slice positions, and the colors correspond to the left Figure.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure S3. GLS/GLS2 spatial transcriptome expression patterns A: GLS spatial feature and violin plot. B: GLS violin plot between different tissues. C: GLS2 spatial feature and violin plot. D: GLS2 violin plot between different tissues.

Supplementary Material 4: Figure S4. GOT1/ GOT2 spatial transcriptome expression patterns A: GOT1 spatial feature and violin plot. B: GOT1 violin plot between different tissues. C: GOT2 spatial feature and violin plot. D: GOT2 violin plot between different tissues.

Supplementary Material 5: Figure S5. GLUD1, PSAT1, and GPT spatial transcriptome expression pattern A: GLUD1 spatial feature and violin plot. B: GLUD1 violin plot between different tissues. C: PSAT1 spatial feature and violin plot. D: PSAT1 violin plot between different tissues. E: GPT spatial feature and violin plot. F: GPT violin plot between different tissues.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [GEO] repository, [PRJNA1029249]”.