Dear Editor,

Cutis laxa (CL) is characterised by the development of loose, wrinkled, redundant, and hypo-elastic skin due to degradation of elastic fibres in the extracellular matrix. It may be inherited or acquired. The acquired form is classified into two types: type 1 or generalised acquired elastolysis and type 2 or Marshall’s syndrome [Table 1].[1,2,3,4,5] Herein, we report a rare case of Marshall’s syndrome associated with Sweet’s syndrome.

Table 1.

| Type 1 or generalised acquired elastolysis | Type 2 or Marshall’s syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | • Drugs (isoniazid, penicillin) | Post-inflammatory elastolysis after Sweet’s syndrome or Sweet’s syndrome like inflammatory dermatoses |

| • Malignancies (multiple myeloma, lymphoma) | ||

| • Infections (Toxocara canis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Treponema pallidum, Onchocerca volvulus) | ||

| • Connective tissue diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) | ||

| • Inflammatory (dermatitis herpetiformis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, sarcoidosis, celiac disease, acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis) | ||

| • Miscellaneous (nephrotic syndrome, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, mastocytosis, amyloidosis) | ||

| Age group | Usually in adults | • Children (when associated with Sweet’s syndrome) |

| • Young adults (when associated with Sweet’s syndrome like inflammatory dermatoses) | ||

| Progression | Starts in head and neck region and expands peripherally in a cranio-caudal fashion | Starts in head and neck region and expands peripherally in a cranio-caudal fashion. |

| Clinical presentation | Generalised or circumscribed (in interstitial granulomatous dermatitis), with or without preceding inflammatory lesions | • Eruptive phase: Appearance of bright red papules and plaques with or without associated fever. It can persist for months to years |

| • Elastolysis phase: Clinical lesions fade and signs of post-inflammatory elastolysis appear | ||

| Systemic involvement | Pulmonary emphysema, pneumothorax, vascular dilatations, gastrointestinal diverticulae, cor-pulmonale, and hernia. | Cardiovascular involvement, Takayasu arteritis |

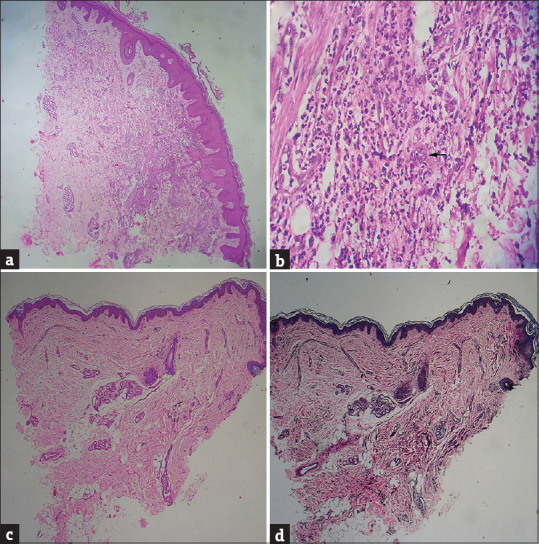

A 3-year-old boy presented with multiple red raised lesions and clear fluid-filled lesions all over the body associated with fever and mild itching for 10 days. The lesions had a cephalocaudal evolution. A history of similar illness was present 4 months back. There was no history of contact with patients of leprosy. Family, immunisation, and developmental and birth history were unremarkable. On examination, multiple well-defined erythematous, edematous papules and plaques of size ranging from 4 × 4 cm to 0.5 × 0.5 cm were present over the face, bilateral ear, trunk, and bilateral upper and lower limbs [Figure 1a and b]. The larger plaques showed relative central clearing and trailing scales. Subsequently, tense, clear fluid-filled vesicles and bullae appeared over the lesions [Figure 1c]. The differential diagnoses considered were erythema nodosum leprosum, Sweet’s syndrome, erythema multiforme, and acute haemorrhagic edema of infancy. Haematological and biochemical tests were within normal limits. Anti-nuclear antibody was negative. Slit skin smear was negative for acid fast bacilli. Histopathological examination revealed diffuse dense infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis with significant leucocytoclasia, suggestive of Sweet’s syndrome [Figure 2a and b]. The patient was started on oral prednisolone at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day, following which all the lesions healed in around 2 weeks with brownish hyperpigmentation and redundant, wrinkled skin in areas of healing of larger plaques [Figure 1d]. A final diagnosis of Marshall’s syndrome associated with Sweet’s syndrome was suspected, and repeat biopsy with Verhoeff Van Geison (VVG) staining was done from the wrinkled skin, which showed reduced elastin in the upper dermis and coarse elastin fibres in the lower dermis [Figure 2c and d]. The patient is now on tapering doses of prednisolone without any recurrence.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Multiple well-defined erythematous, edematous papules and plaques, with a few lesions showing targetoid appearance. (c) Tense, clear fluid-filled vesicles and bullae (black arrow) over the lesions. (d) Wrinkling of skin after healing (red arrow)

Figure 2.

(a) Diffuse dense infiltration of neutrophils in the upper dermis (H and E, ×40). (b) Significant leukocytoclasia along with dilated vessels and endothelial swelling (black arrow) (H and E, ×400). (c) Epidermal atrophy and absence of inflammatory cells in upper dermis after treatment (H and E, ×40). (d) Reduced elastin in upper dermis and coarse elastin fibres in lower dermis (VVG, ×40)

The pathogenesis of Marshall’s syndrome is not clear; however, stimulation of elastase activity and/or dysfunction of elastase/protease inhibitors in genetically susceptible individuals resulting in elastolysis forms the basis of pathogenetic mechanisms.[1] Low lysyl oxidase activity, high cathepsin G levels, and reduced alpha-1-antitrypsin mostly contribute to decreased cutaneous elastin.[2] Elastase produced by neutrophils and macrophages may cause destruction of elastin. Another hypothesis is the deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin, which allows the protease to destroy the dermal elastic tissues.[4]

The most common associations described in order of frequency are Sweet’s syndrome, urticaria-like neutrophilic dermatosis, and acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis.[3] In the index case, Sweet’s syndrome was associated with acquired cutis laxa. Sweet’s syndrome was diagnosed based on fulfilment of two major and two minor criteria. Cardiovascular involvement and Takayasu arteritis have been described as systemic association of Marshall’s syndrome.[4,5] In our case, no systemic complication was found.

Marshall’s syndrome is often refractory and irreversible to treatment. Dapsone, oral prednisolone, and adalimumab have been used in acquired cutis laxa secondary to neutrophilic dermatoses.[3] Plastic surgery, botulinum toxin injection, and face-lift treatment have also been used.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Çalışkan E, Açıkgöz G, Yeniay Y, Özmen İ, Gamsızkan M, Akar A. A case of Marshall's syndrome and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:e217–21. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berk DR, Bentley DD, Bayliss SJ, Lind A, Urban Z. Cutis laxa: A review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:842.e1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita A, Fukui T, Akasaka E, Nakajima K, Nakano H, Sawamura D, et al. Acquired cutis laxa secondary to acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: A case report and mini-review of literature. J Dermatol. 2023;51:287–93. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagati A, Shrivastava S, Baghela B, Agarwal P, Saikia S. Acquired cutis laxa secondary to Sweet syndrome in a child (Marshall syndrome): A rare case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:146–9. doi: 10.1111/cup.13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michl C, Hühn R, Sunderkötter C. Sweet-Syndrom des Kindesalters mit erworbener Cutis laxa (Marshall-Syndrom) als Erstmanifestation einer Takayasu-Arteriitis [Sweet syndrome of childhood with acquired cutis laxa (Marshall syndrome) as primary manifestation of Takayasu arteritis. Dermatologie (Heidelb) 2022;73:884–890. doi: 10.1007/s00105-022-04999-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]