Dear Editor,

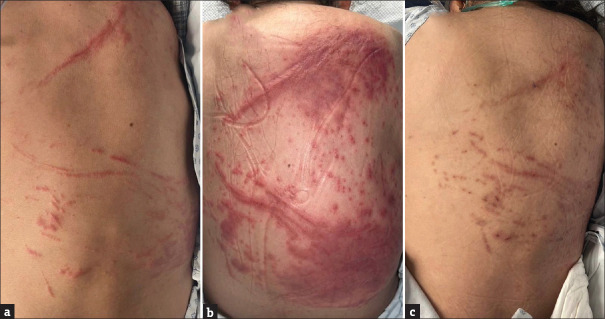

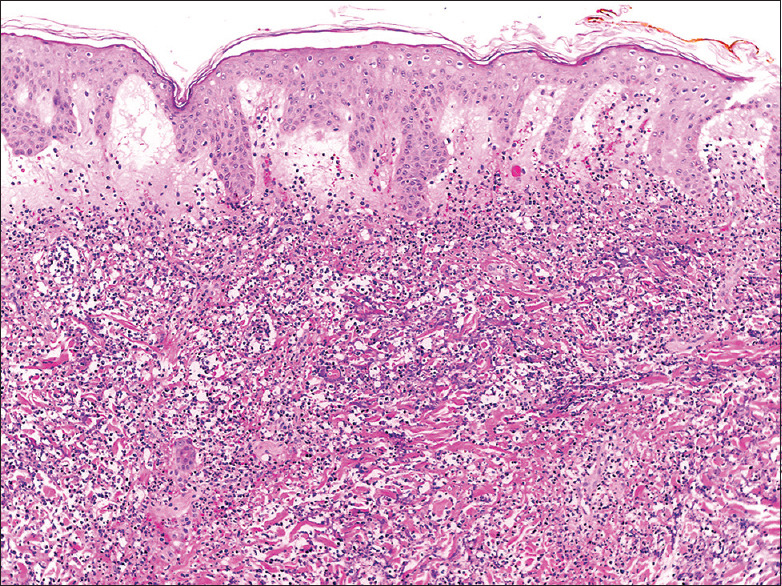

We present a case involving a 49-year-old woman who sought care for community-acquired pneumonia and serologic signs of lupus activity at our institution. Her medical history included rhupus, characterised by functional class IV rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, arthritis mutilans, secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Treatment for her underlying conditions included: prednisone 10 mg/day, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/day, warfarin, ferrous sulphate, and analgesics. Physical examination revealed an asymptomatic dermatosis, characterised by linear erythema, and erythematous millimetre-sized papules, arranged linearly on the back, resembling a flagellate-like erythema [Figure 1a], which, within 48 hours, evolved into erythematous-oedematous (urticarial) plaques that maintained a linear configuration [Figure 1b]. Laboratory testing indicated neutrophilia (9600/μL) and an elevated reactive C protein (19.23 mg/dL). A skin biopsy was performed, revealing diffuse neutrophilic dermatitis with oedema of the papillary dermis and karyorrhexis [Figure 2], findings compatible with Sweet syndrome (SS). The patient was started on prednisone (0.5 mg/kg daily), which led to the lesions’ improvement and eventual transition to post-inflammatory pigmentation in the course of 1 week [Figure 1c].

Figure 1.

Dermatosis on day 1, showing slight linear erythema. Dermatosis on day 2, displaying erythematous-edematous plaques in a linear pattern, as well as confluence in other areas with erythematous plaques and infiltrated edema. Dermatosis on day 5, with clinical resolution within 48 hours following the increase of systemic steroids

Figure 2.

The H&E-stained skin biopsy reveals significant dermal edema accompanied by a dense neutrophilic infiltrate, with no evidence of vasculitis

SS is an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, often presenting as erythematous-violaceous, tender nodules, papules, or plaques on the face, neck, and upper extremities, frequently accompanied by fever and neutrophilia. It is often accompanied by new-onset fever and neutrophilia. SS primarily affects adults over the age of 50. Some reports indicate a slight prevalence in women, with no predominance in any ethnic group. However, there is a notable association with hematologic diseases, autoimmune disorders, and solid organ neoplasms, among others.[1,2] SS can manifest in various clinical scenarios, including classic/idiopathic, malignancy-associated, or drug-induced forms, characterised by skin symptoms, fever, and laboratory abnormalities such as elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and neutrophilic leucocytosis.[3]

Our patient’s history of rhupus and respiratory tract infection represented potential triggers for the development of SS. In addition, the patient denied having risk factors for flagellate erythema, such as fungal infections or medication intake. The skin lesions, initially resembling flagellate erythema, were identified upon closer examination as typical SS papules, despite their unusual back and arm locations. Described clinical variants of SS encompass the prototypic clinical presentation, bullous SS, cellulitis-like SS, necrotising SS, and neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands. Our patient exhibited what we propose as a new clinical variant: flagellate erythema-like.[2] We propose a new clinical variant of SS resembling flagellate erythema.

The differential diagnosis should include neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis, which is characterised by persistent elevated pink or red plaques or macules, often seen in patients with lupus, but without dermal oedema, unlike SS.[4] Our patient’s primary lesions persisted for over 48 hours, supporting the SS diagnosis, further confirmed by biopsy findings of diffuse neutrophilic dermatitis with oedema and karyorrhexis.

Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay of SS treatment, with prednisone doses ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg/day. Cutaneous lesions typically improve within 72 hours of treatment initiation, with second-line therapies available for refractory cases.

This case is unique in its simulation of flagellate erythema by SS, underscoring the importance of considering SS in atypical presentations and lowering the biopsy threshold for accurate diagnosis.[5]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Villarreal CD, Ocampo J, Villarreal A. Sweet syndrome: A review and update. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2016;1(107):369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, Duvic M. New practical aspects of Sweet syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:301–18. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00673-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng S, Li S, Tang S, Pan Y, Ding Y, Qiao J, et al. Insights into the characteristics of Sweet syndrome in patients with and without hematologic malignancy. Front Med. 2020;18(7):20. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gusdorf L, Lipsker D. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis: A review. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018;145:735–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendonça FM, Márquez-García A, Méndez-Abad C, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, Perea-Cejudo M, Martín JJR, et al. Flagellate dermatitis and flagellate erythema: Report of 4 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:461–3. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]