Abstract

Familial dysautonomia (FD) is a fatal autosomal recessive congenital neuropathy caused by a T-to-C mutation in intron 20 of the Elongator acetyltransferase complex subunit 1 (ELP1) gene, which causes tissue-specific skipping of exon 20 and reduction of ELP1 protein. Here, we developed a base editor (BE) approach to precisely correct this mutation. By optimizing Cas9 variants and screening multiple gRNAs, we identified a combination that was able to promote up to 70% on-target editing in HEK293T cells harboring the ELP1 T-to-C mutation. These editing levels were sufficient to restore exon 20 inclusion in the ELP1 transcript. Moreover, we optimized an engineered dual intein-split system to deliver these constructs in vivo. Mediated by adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery, this BE strategy effectively corrected the liver and brain ELP1 splicing defects in a humanized FD mouse model carrying the ELP1 T-to-C mutation and rescued the FD phenotype in iPSC-derived sympathetic neurons. Importantly, we observed minimal off-target editing demonstrating high levels of specificity with these optimized base editors. These findings establish a novel and highly precise BE-based therapeutic approach to correct the FD mutation and associated splicing defects and provide the foundation for the development of a transformative, permanent treatment for this devastating disease.

Keywords: ELP1, CRISPR, Cas9, genome editing, bystander editing, splicing, neurodegenerative disease

Introduction

Familial dysautonomia (FD), also known as hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type III (HSANIII) or Riley-Day syndrome, is a rare, fatal, inherited congenital disorder that affects the development and survival of specific unmyelinated sensory and autonomic neurons. FD is caused by a T-to-C base transition at the 6th base of intron 20 (c.2204+6T>C) of the Elongator acetyltransferase complex subunit 1 (ELP1, previously known as IKBKAP)1,2. This mutation (henceforth ELP1 T6C) results in variable tissue-specific skipping of ELP1 exon 20, leading to a premature termination codon and a corresponding reduction in ELP1 protein1,3. The lowest levels of ELP1 expression occur in the central and peripheral nervous system3. Most patients with FD are of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, with a carrier frequency in that population of 1:30, rising to 1:17 for Polish Jews4,5. All FD patients possess at least one copy of this mutation, and 99.5% of patients are homozygous1,6. FD symptoms include decreased pain and temperature sensation, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, labile blood pressure, gait ataxia, and retinal degeneration7–12 (Fig. 1a). Neurogenic dysphagia causes frequent aspiration, leading to chronic pulmonary disease. Characteristic hyperadrenergic “autonomic crises” consisting of brisk episodes of severe hypertension, tachycardia, skin blotching, retching, and vomiting occur in all patients8,12–15. Unexplained sudden death, aspiration pneumonia, and respiratory insufficiency remain the leading causes of death7,11. To date, there are no treatments available to stop the continuous neuronal loss in FD patients.

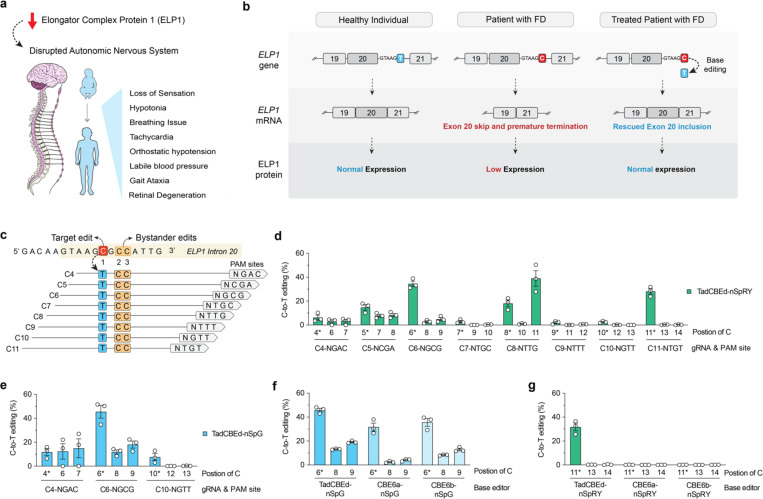

Figure 1. Development of cytosine base editors to correct the ELP1 T6C mutation causing FD.

a, Schematic of familial dysautonomia (FD) symptoms caused by reduced ELP1 protein levels affecting the autonomic nervous system. b, Schematic of FD caused by reduction in ELP1 protein levels due to a T-to-C (T6C) mutation in the position 6 of intron 20. c, Schematic of the genomic region surrounding the ELP1 T6C mutation, showing base editor guide RNA (gRNA) target sites; potential bystander edits are highlighted in orange boxes. d-e, C-to-T base editing to correct ELP1 T6C in homozygous HEK293T cells using TadCBEd, which comprises deaminase domains fused to PAM-variant SpCas9 enzymes nSpRY (d) and nSpG (e). Edited alleles were assessed via targeted sequencing and analyzed using CRISPResso2. f-g, Comparison of deaminase activity for correcting the ELP1 T6C mutation in homozygous HEK293T cells using TadCBEd, CBE6a, or CBE6b deaminase domains fused to SpG paired with gRNA C6 (f) or SpRY paired with gRNA C11 (g). Data in panels d-g from experiments in HEK 293T cells harboring the ELP1 T6C mutation; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints are shown for n = 3 independent biological replicates.

Previous efforts to develop therapeutic approaches for FD include splicing modulator compounds (SMCs), antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), modified exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNAs (ExSpe snRNAs), and gene replacement therapy16–22. However, none of these potential strategies offer a permanent cure or have been FDA-approved. The drawbacks of SMCs in these potential therapies lie in their frequent lack of specificity and transient nature. Similarly, ASOs, ExSpe snRNAs, and gene replacement therapies have limitations, including transient effects, unknown longevity of expression, utilization of ubiquitous exogenous promoters, uncontrolled gene expression, and potential neurotoxicity. Genome editing technologies capable of permanently correcting the FD splicing mutation to adequately maintain endogenous expression of ELP1 would overcome many of these challenges.

Base editors (BEs) and prime editors (PEs) are genome editing technologies capable of installing point mutations23. Recently, we reported preclinical efforts to optimize novel BE technologies to treat spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a severe pediatric neuromuscular disease24. SMA is caused by mutations in SMN1. SMN2 is a paralogous gene with a base transition in exon 7, which causes this exon to be skipped in most SMN2 transcripts. Thus, we developed a BE approach to restore SMN expression by correcting the SMN2 coding sequence. We engineered enzymes and tested several combinations of guide RNAs (gRNAs) capable of editing SMN224. One optimized combination resulted in up to 99% intended editing in SMA patient-cells24, highlighting the great therapeutic potential of customized BEs to introduce corrective genetic edits efficiently and safely.

In this study, we investigated the feasibility of developing a genetic treatment for FD by correcting the ELP1 T6C using cytosine base editing (Fig. 1b). We performed a series of engineering strategies to optimize these base editors along with a comprehensive evaluation of on-target and off-target editing via unbiased methods. Minimum off-target editing was observed showing high levels of specificity with these optimized base editors. To assess the in vivo effectiveness of the most optimal base editors, we utilized a humanized FD mouse model harboring the ELP1 T-to-C mutation as well as FD-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived neurons. Our findings demonstrate that engineering base editors can effectively correct the ELP1 splicing defects in vivo and in human neurons, leading to phenotypic rescue. This work provides essential in vivo proof-of-concept data necessary to advance a durable, single-dose therapeutic strategy for FD toward the clinic.

Results and Discussion

Development of HEK 293T cell lines harboring the ELP1 T6C mutation

We first established a homozygous HEK 293T cell line harboring the ELP1 T6C mutation via adenosine base editing (ABE). We sought to generate this cell line to rapidly screen and prioritize combinations of editors and guide RNAs (gRNAs) that maximize editing efficiencies. We tested various combinations of gRNAs and ABEs (Sup. Fig. 1a). Transfections in HEK 293T cells were performed to investigate the efficacy of these combinations, with some combinations achieving >50% precise introduction of the mutation with the presence or not of bystander editing (Sup. Fig. 1a). To create a clonal cell line, we further selected the most optimal ABE paired gRNA-A6 and transfected into fresh HEK 293T cells followed by a serial dilution for single cell sorting (Sup. Fig. 1b). Targeted sequencing of the ELP1 locus in genomic DNA extracted from clonal cell lines confirmed that some harbored homozygous ELP1 T6C mutation and we selected a homozygous HEK 293T cell line harboring ELP1 T6C and no other bystander edits (hereafter named HEK 293T-ELP1-TC6) to use throughout this study to screen and optimize base editor strategies for correcting the FD mutation.

Development of cytosine base editors to correct the ELP1 T6C mutation

Using the newly developed HEK 293T-ELP1-TC6 homozygous cell line, we explored the potential of various cytosine base editors (CBEs) to correct the ELP1 T6C mutation since CBEs can catalyze C•G to T•A edits25. We recognize that this approach has several challenges. For example, CBEs can only act in a narrow ‘edit window’ within the gRNA-Cas target site at a fixed distance from a PAM motif, but there are no NGG PAMs typically recognized by wild-type (WT) CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes for this specific ELP1 site (Fig. 1c). Thus, this site is not accessible for WT CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes. Another complicating factor is that the target cytosine has two additional adjacent cytosines, which may lead to bystander edits (Fig. 1c). To overcome these challenges and identify an efficient and precise CBE strategy, we utilized previously engineered SpCas9 variants that have relaxed tolerance for NNN PAMs (named SpRY) or preference for an NGN PAM motif (named SpG)26. In addition, we designed eight different gRNAs to tile target sites across the ELP1 T6C editable window for CBEs by placing the target cytosine at positions C4 to C11 (Fig. 1c). We tested various Cas enzymes linked with different deaminases and found that recently developed CBEs comprised of the TadCBEd deaminase25 is more efficient than other conventional options such as BE4max27 as well as prime editing strategies to edit the ELP1 FD mutation (Fig. 1d–e and Sup. Fig. 2a–c). Therefore, we cloned TadCBEd deaminase into our SpRY and SpG Cas9 variants. TadCBEd-SpRY enabled C-to-T editing across nearly all gRNAs within this editing window, with the most promising result observed using gRNA C11 (NTG PAM), which achieved efficient target base correction without any bystander editing mutation (Fig. 1d). TadCBEd-SpG also resulted in C-to-T editing using all gRNAs with NGN PAMs (Fig. 1d). The most efficient combination identified across all CBE conditions was TadCBEd-SpG paired with gRNA-C6 (NGC PAM). While this condition resulted in bystander editing at two other cytosine sites (Fig. 1e), it is important to emphasize that these edits occur in the intronic region and have no negative impact on exon 20 inclusion or ELP1 splicing. Moreover, TadCBEd deaminase domain activity was superior to CBE6a and 6b (Fig. 1f–g). Taken together, these data demonstrate that optimized CBEs can correct the ELP1 T6C mutation in human cells.

Optimization of an AAV-delivered base editing strategy to correct the ELP1 T6C mutation

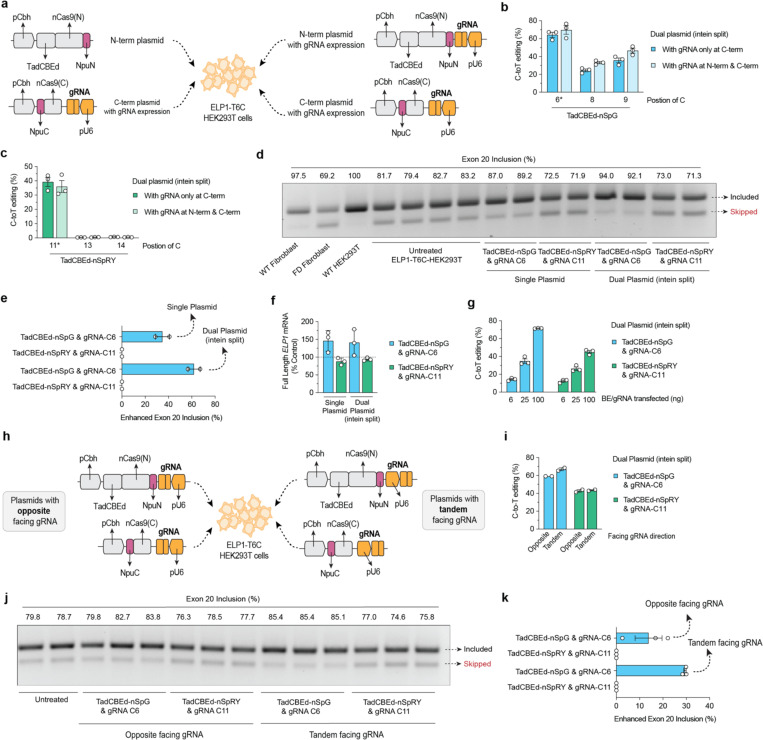

We then selected two conditions for further investigation: (1) TadCBEd-SpRY paired with gRNA-C11, which results in reasonable on-target editing with no bystander editing and (2) TadCBEd-SpG paired with gRNA-C6, which results in the highest on-target editing. To prepare for future in vivo applications, we applied a series of engineering strategies to produce an intein-split system to facilitate the packaging of these constructs into AAV vectors for in vivo delivery24. First, we cloned novel variants of intein-split systems expressing gRNAs in both C-terminal and N-terminal, which achieved efficient on-target editing in cells (Fig. 2a–c). Most importantly, we observed that TadCBEd-SpG and gRNA-C6 combination delivered via this intein-split system resulted in a significant increase in ELP1 exon 20 inclusion, which was not observed with the TadCBEd-SpRY and gRNA-C11 combination (Fig. 2d–f). To better simulate in vivo conditions where BE expression may not be optimal, we performed titration experiments in R179H HEK 293T cells. This experiment allowed us to establish a dynamic range of activity across different constructs, reflecting more physiologically relevant expression levels. We observed that TadCBEd-SpG with gRNA C6 resulted in the highest levels of on-target ELP1 TC6 correction (Fig. 2g). Lastly, we evaluated the impact of gRNA orientations relative to the base editor within these constructs, testing whether this architectural variation could impact the editing efficiency (Fig. 2h). Our findings revealed that tandem-facing gRNAs yielded slightly higher editing efficiency compared to the opposite-facing orientation. More importantly, this configuration resulted in a greater rescue of ELP1 exon 20 inclusion (Fig. 2i–k). Collectively, these optimizations led to the development of a refined construct, paving the way for further in vivo testing.

Figure 2. Engineering an intein-split system for in vivo delivery via adeno- associated virus (AAV).

a, Schematic of plasmid transfection experiments in HEK293T-ELP1-T6C cells using ITR-containing intein-split AAV production plasmid for TadCBEd fused with SpCas9 variants SpG or SpRY with N-terminus and C-terminus. Comparison between strategies with or without guide RNA (gRNA) expression in the N-term. b-c, C-to-T base editing to correct ELP1 T6C in homozygous HEK293T cells using AAV plasmids illustrated in panel a. d-e, ELP1 protein splicing assessing exon 20 inclusion and quantification for splicing enhancement in HEK293T ELP1 T6C cells treated with conventional base editor or intein-split plasmids. f, qPCR analysis of full-length ELP1 transcript expression following treatment with conventional and AAV plasmid systems using SpCas9 variants SpG paired with gRNA-C6 and SpRY paired with gRNA-C11). g, C-to-T editing efficiency using DNA titration of intein-split AAV plasmid in HEK293T ELP1 T6C cells. h, Schematic comparing opposite vs. tandem gRNA cassette orientation relative to SpCas9 expression in ITR-containing intein-split AAV production plasmids. i, C-to-T editing efficiency comparison between opposite and tandem gRNA orientations in intein-split AAV plasmids. j-k, ELP1 protein splicing assessing exon 20 inclusion and quantification for splicing enhancement when HEK293T ELP1 T6C cells treated with construct in panel h. Data in panels b-c, e-g, I, and k are from experiments in HEK293T cells; mean, s.e.m., and individual datapoints are shown for n = 2 or 3 independent biological replicates.

Assessment of CBE-mediated ELP1 T6C correction specificity

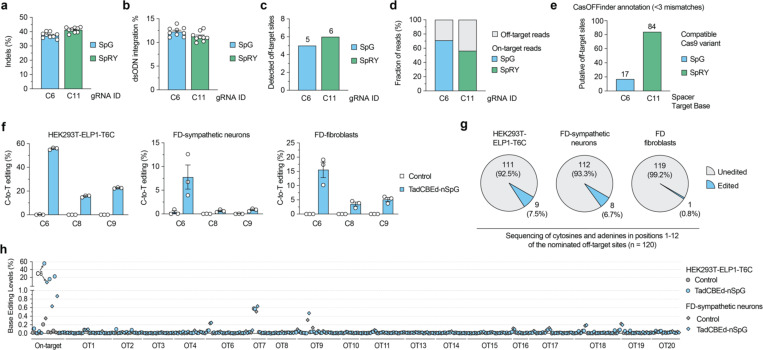

Given that base editors can introduce unwanted genome-wide off-target edits, we performed an unbiased cell-based assay (GUIDE-seq2) and in silico prediction (Cas-OFFinder) to nominate putative off-target sites. GUIDE-seq2 is an updated version of GUIDE-seq28,29. We performed GUIDE-seq2 in HEK293T-ELP1-TC6 using nucleases SpG paired with gRNA C6 and SpRY paired with C11. Sequencing data from GUIDE-seq2 experiments revealed expected on-target editing (Fig. 3a) and integration of the GUIDE-seq dsODN tag (Fig. 3b). Off-target analysis revealed 5 and 6 off-target sites detected for SpG and SpRY, respectively (Fig. 3c and Sup. Fig. 3a–b). With SpG and gRNA-C6, about 70% of reads were attributable to on-target editing, while only about 55% for on-target reads for SpRY and gRNA-C11 (Fig. 3d), suggesting an increased on-target precision for the intended ELP1 site targeting with SpG and gRNA-C6 when compared to SpRY and gRNA-C11. Analysis of putative off-target sites with 3 or fewer mismatches using Cas-OFFinder for SpG with gRNA-C6 or SpRY with gRNA-C11 revealed 17 and 84 sites, respectively (Fig. 3e and Sup. Fig. 4a–c). Importantly, among the 17 targets identified for SpG with gRNA-C6, two were also previously identified by GUIDE-seq2.

Figure 3. Base editing specificity in correcting the ELP1 T6C mutation.

a-b, Results from GUIDE-seq2 experiments including analysis of insertion or deletion (indels; panel a) and quantification of reads containing the GUIDE-seq2 dsODN tag (panel b) in ELP1 T6C HEK 293T cells when using SpCas9 variants SpG nuclease with gRNA-C6 or SpRY nuclease with gRNA-C11. c, Total number of GUIDE-seq2-detected off-target sites using SpG or SpRY. d, Percentage of total GUIDE-seq reads attributable to the on-target site or cumulative off-target sites. e, Number of putative off-target sites in the human genome with up to 3 mismatches for the spacers of gRNAs C6 and C11, as annotated by CasOFFinder. f, On-target C-to-T editing levels in HEK293T-ELP1-T6C cells, iPSC-derived FD-sympathetic neurons, and FD patient primary fibroblast cells when treated with TadCBEd-nSpG paired with gRNA-C6. g, Pie chart showing a summary of off-target sites validated for gRNA C6 and SpG across all 3 cell types in panel f, based on in silico CasOFFinder and GUIDE-seq2 nominations. h, Summary of on- and off-target base editing levels in three cell lines from panel f. Cells were untreated (naïve) or treated with TadCBEd-nPSG and gRNA C6. Genomic DNA was subjected to PCR for the on-target site and 19 off-target sites (nominated by CasOFFinder and GUIDE-seq2) with data analysis via CRISPResso2 for n = 3 independent biological replicates. For panels a-b and f, mean, standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.), and individual data points are shown for n = 3 or 9 independent biological replicates.

We next validated the list of a total of 20 nominated off-target sites from GUIDE-seq2 combined with CasOFFinder for SpG paired with gRNA-C6. For this validation step, we used three different cells that demonstrated precise on-target editing: HEK293T-ELP1-TC6 (Fig. 3f and Sup. Fig. 5), FD iPSC-derived sympathetic neurons (Fig. 3f and Sup. Fig. 6a–b), and FD patient fibroblasts (Fig. 3f and Sup. Fig. 7).

Off-target base editing was detected at 9 sites in HEK293T-ELP1-TC6 cells, 8 sites in FD iPSC-derived sympathetic neurons, and only a single site in FD patient primary fibroblasts (Fig. 3g). Notably, all significant off-target base editing was lower than 0.2% in absolute values when compared to untreated paired cells (Fig. 3h). In summary, these results demonstrate that our developed TadCBEd-nSpG base editor paired with gRNA-C6 can effectively correct ELP1 T6C with minimal off-target editing in different human cell types.

In vivo testing of ELP1 base editing efficiency in a humanized FD mouse model and phenotypic recovery in human sympathetic neurons

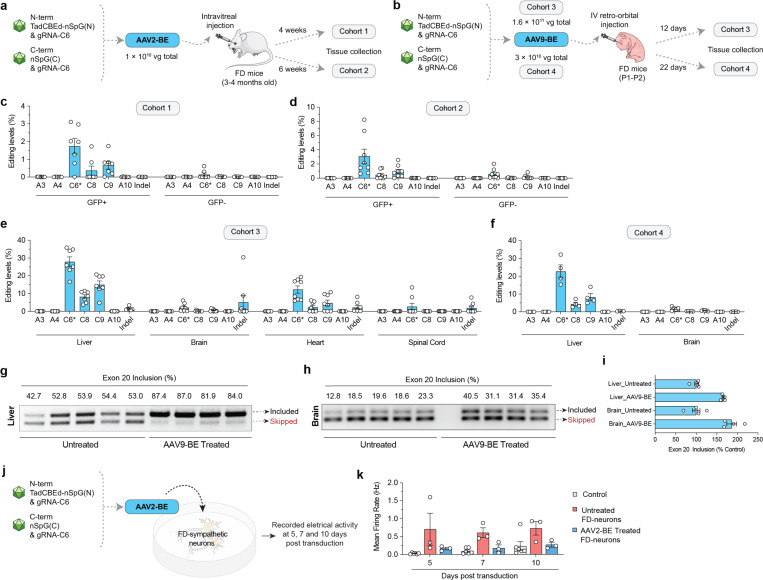

To assess the translatability of our base editing approach, we used two different AAV serotypes, AAV2 and AAV9, to deliver our N- and C-terminal TadCBEd-nSpG and gRNA-C6 strategy in the humanized TgFD9 mouse model, which carries the full ELP1 human gene with the FD mutation30. This model is phenotypically normal, as it expresses normal levels of mouse endogenous ELP1, but it faithfully recapitulates the ELP1 splicing defect observed in FD patients, making it an ideal model for testing the effects of our base editing approach on rescuing ELP1 splicing in vivo. We delivered AAV2-BE via intravitreal injections into TgFD9 mice (Fig. 4a) and AAV9-BE systemically in TgFD9 neonates (Fig. 4b). Analysis was conducted using two distinct cohorts for each delivery method, with varying doses and time courses (Fig. 4a–b). These two delivery approaches are highly translatable: AAV2 delivery via intravitreal injection provides a localized treatment that has the potential to rescue retinal degeneration, while AAV9 systemic delivery has the potential to address the systemic manifestations of the disease. AAV2-BE intravitreal delivery promoted up to 9% on-target editing in retinal cells, with average values close to 3% (Fig. 4c–d). In parallel, we observed a range of editing efficiency across different tissues with the systemic injections (Fig. e–f). Notably, liver was the most edited tissue with about 30% editing on average, and brain tissues reached up to 5% editing levels (Fig. 4e–f). To determine whether these editing levels could rescue ELP1 exon 20 inclusion in vivo, we extracted RNA and calculated the % exon 20 inclusion levels in both liver and brain tissues. Remarkably, in TgFD9 mice injected with AAV9-BE, the percentage of ELP1 exon 20 inclusion in the brain nearly doubled compared to untreated mice. In the liver, although the base editing efficiency was higher than in the brain, we observed only a 20% increase in ELP1 exon 20 inclusion in treated TgFD9 mice compared to untreated controls (Fig. 4g–i). One possible explanation for this is the tissue-specific variability in the splicing of the mutant ELP1 transcript. In the liver, the mutant transcript already splices relatively well, reaching an average of 66% exon 20 inclusion, even in untreated TgFD9 mice, whereas in the brain, splicing is much less efficient, with only an average of 18% exon 20 inclusion. The difference in baseline splicing efficiency could explain the more pronounced improvement in splicing following base editing in the brain. These striking findings demonstrate for the first time that these optimized base editors can significantly rescue the ELP1 splicing in mouse brain.

Figure 4. AAV-mediated delivery of base editors for in vivo ELP1 C6T editing.

a, Schematic of local retina injections of dual AAV2-BE vectors expressing intein-split TadCBEd-SpG and gRNA C6 into TgFD9 mice carrying the human ELP1 transgene with T6C mutation. Mice retina ganglion cells were isolated and sorted based on GFP expression at 4 or 6 weeks post-injection. b, Schematic of P1–2 intravenous (IV) injections of AAV9-BE vectors expressing intein-split TadCBEd-SpG and gRNA C6 into TgFD9 neonates. Mice were sacrificed, and tissues were harvested at 12 or 22 days post-injection. c-f, On-target C-to-T editing and potential bystander editing in the retina cells (c-d) or across different tissues (e-f) in each cohort treated base editors. g-h. ELP1 splicing in liver (g) and brain (h) tissues after AAV9-BE treatment. i, Quantification of exon 20 inclusion as percentage of the control in mice tissues are shown in panels g and h. j, Schematic of AAV2-BE transduction in iPSC-derived FD sympathetic neurons. Cell culture plates equipped with multielectrode arrays (MEAs) were used to record the electrical activity of sympathetic neurons. k, Electrical activity of iPSC-derived FD sympathetic neurons recorded at 5, 7, and 10 days post-transduction. Measurements were taken from both untreated and AAV2-BE-treated neurons. The mean firing rate was used to quantify overall neuronal firing activity. For panel k, mean, standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.), and individual data points are shown for n = 3-6 independent biological replicates.

To assess the therapeutic potential of our approach in rescuing the neuronal phenotype, we used FD iPSC-derived sympathetic neurons, as they accurately recapitulate many of the neuronal features characteristic of FD31. After treatment with AAV2-BE, we observed approximately 10% editing efficiency in the FD iPSC-derived sympathetic neurons. We recorded the electrical activity of these neurons at 5, 7, and 10 days post-transduction, comparing treated and untreated groups (Fig. 4j and Sup. Fig. 4). As previously described, FD sympathetic neurons exhibited hyperactivity when compared to neurons derived from healthy control hiPSCs (Fig. 4k). Notably, in FD sympathetic neurons treated with AAV2-BE, we observed a full recovery of activity to normal levels, demonstrating that even a 10% editing efficiency is sufficient to produce a significant improvement in critical FD-related phenotypes. In summary, the development and validation of a gene editing technology targeting the FD splicing mutation provides a groundbreaking approach to treating this devastating disorder. The significance of this work is underscored by the rapid advancements in gene editing and the severity of FD, a disease that currently lacks effective therapeutic options beyond supportive care. This study represents a pioneering effort to assess the therapeutic potential and safety of base editors in correcting the ELP1 splicing defect, both in a mouse model and a human neuronal model of FD, thereby paving the way for future therapeutic interventions in FD.

Discussion

FD is a sensory and autonomic neurodegenerative disease for which no effective treatments currently exist to halt the progressive neuronal loss that defines this devastating disorder. A permanent base editing therapy for FD holds the potential to transform disease care. Notably, because all FD patients carry at least one copy of the ELP1 T6C mutation, and 99.5% are homozygous for this mutation10,11, developing a precise and efficient strategy to correct the genetic cause of FD would benefit all affected individuals. Several efforts have been made to develop disease-modifying therapies, including small molecule SMCs, ASOs, and modified exon-specific U1 snRNAs 12–14. While these approaches have shown promising effects in mouse models12,14,15, confirming the therapeutic relevance of ELP1 as a target, none offer a permanent solution or have achieved FDA approval. SMCs often lack specificity and are transient, while ASOs, exon-specific U1 snRNAs, and gene replacement therapies face limitations such as transient effects, unknown duration of expression, reliance on exogenous promoters, uncontrolled gene expression, and potential neurotoxicity. In contrast, genome editing technologies capable of permanently correcting the ELP1 splicing mutation while preserving endogenous expression levels would address these challenges and represent a significant advance in therapy for FD.

Methods

Plasmids and oligonucleotides

Target site sequences for gRNAs are available in Supplementary Table 2. Plasmids used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 3; new plasmids related to genome editing technologies generated during this study will be available through Addgene. Oligonucleotide sequences are available in Supplementary Table 4. Briefly, base editor plasmids were generated by subcloning different TadA deaminase sequences into the NotI and BglII sites of pCMV-T7-ABEmax(7.10)-VRQR-P2A-EGFP (RTW5025; Addgene plasmid 140003) via isothermal assembly32. Additional mutations were cloned into BE plasmids using isothermal assembly the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (E0554; New England Biolabs; NEB). Expression plasmids for human U6 promoter-driven gRNAs were generated by annealing and ligating duplexed oligonucleotides corresponding to spacer sequences into BsmBI-digested pUC19-U6-BsmBI_cassette-SpCas9_gRNA (BPK1520; Addgene plasmid 65777). Npu intein-split ABE constructs were cloned into N- and C-terminal AAV plasmids (Addgene plasmids 137177 and 137178, respectively). The N-terminal vector was modified to include the deaminase domain and gRNA cassette. The C-terminal vector was modified to encode the spacers for ELP1-T6C.

HEK293T and fibroblast culture

Human HEK 293T cells (American Type Culture Collection; ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (HI-FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Transfections were performed 20 hours following seeding of 2×104 HEK 293T cells per well in 96-well plates. Base editor transfections contained 70 ng of ABE expression plasmid and 30 ng gRNA expression plasmid (exception for specific experiments testing lower doses, which included a supplemented weight of a stuffer plasmid BPK1098 to reach 100 ng total DNA) mixed with 0.72 μL of TransIT-X2 (Mirus) in a total volume of 15 μL Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transfection mixtures were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature and distributed across the seeded HEK 293T cells. Experiments were halted after 72 hours and genomic DNA (gDNA) was collected by discarding the media, resuspending the cells in 100 μL of quick lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 25 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 60 ng/μL Proteinase K (NEB)), heating the lysate for 6 minutes at 65 °C, heating at 98 °C for 2 minutes, and then storing at −20 °C. For experiments to generate clonal cell lines, serial dilutions were performed to sort for single clones. Samples of supernatant media from cell culture experiments were analyzed monthly for the presence of mycoplasma using MycoAlert PLUS (Lonza).

For fibroblast cell culture, GMO2343 patient fibroblasts were thawed and incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM-10%) fetal bovine (FBS) for 72 hours. Fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% HI-FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For experiments involving fluorescence-activated cell sorting, the media was modified to contain 20% HI-FBS for recovery after sorting. Fibroblasts were transfected with Lipofectamine LTX (ThermoFisher) to deliver separate plasmids encoding base editors. Approximately 48 hours after transfection, GFP+ fibroblasts were sorted (MGH Pathology: Flow and Mass Cytometry Core (CNY) and DNA was extracted.

Human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) lines

hPSC experiments were carried out in vitro with two hPSC lines: H9, a healthy control embryonic stem cell line, and S2, an FD patient derived iPSC line. H9 embryonic stem cells were purchased from WiCell, H9=WA-09 (female, NIH registry # 0062). S2 iPSCs were reprogrammed and characterized previously31 from FD patient fibroblasts purchased from Coriell S2=GM04899 (female, 12 years old). The fibroblasts were previously reprogrammed, characterized31 and resulting iPSCs have been employed to study FD in vitro 31,33–35. Detailed stem cell maintenance has been previously described33,34. hPSCs were maintained in Essential 8 medium (Gibco, A15170–01) on Vitronectin (Thermo Fisher/Life Technologies, A14700, 5 ug/ml) coated cell culture plates and passaged regularly with EDTA (Sigma, ED2SS).

In vitro differentiation of hPSCs into sympathetic neurons

In vitro differentiation into sympathetic neurons was done as previously described33,34. On day 0, hPSCs were dissociated in EDTA for 20 min at 37°C, washed with 1X PBS, and plated on Geltrex (Invitrogen, A1413202) coated plates at 1.25*105 cells/cm2. On day 0–1 cells were maintained in Essential 6 medium (Gibco, A15165–01) supplemented with 0.4 ng/ml BMP4 (PeproTech, 314-BP), 10 uM SB431542 (R&D Systems, 1614), and 300 nM CHIR99021 (R&D Systems, 4423). From day 2 to day 10, cells were fed with Essential 6 medium containing 10 uM SB431542 and 0.75 uM CHIR99021. On day 10, neural crest cells were rinsed with 1x PBS twice, then dissociated with Accutase (Corning, AT104500) for 20 min. at 37°C. Dissociated neural crest cells were again rinsed with 1X PBS and replated onto ultra low-attachment 24 well cell culture dishes (Corning, 07 200 602) at 0.5*106 cells/well. Sympathetic neuron progenitors were maintained in 3D spheroid cultures from day 10 to day 14 in Neurobasal media (Gibco, 21103–049) containing 1% N2 supplement (Gibco, 17502–048), 2% B27 supplement (Gibco, 17502–048), 1% L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher/Gibco, 25030–081), 3 uM CHIR99021, and 10 ng/ml FGF2 (R&D Systems, 233-FB/CF). On day 14, sympathetic neuron progenitors were dissociated in Accutase for 20 min. at 37°C, washed in 1X PBS, and replated on PO (Sigma, P3655)/LM (R&D Systems, 3400–010-01)/FN (VWR/Corning, 47743–654) coated cell culture dishes at 1.0*105 cells/cm2. Sympathetic neuron growth and maturation was supported by maintaining cells in Neurobasal medium containing 1% N2 supplement, 2% B27 supplement, 1% L-glutamine, 25 ng/ml GDNF (PeproTech, 450), 25 ng/ml BDNF (R&D Systems, 248-BD), 200 uM Ascorbic Acid (Sigma, A8960), 25 ng/ml NGF (PeproTech, 450–01), and 200 uM dbcAMP (Sigma, D0627) with 0.125 uM RA (Sigma, R2625). RA was added fresh at each feeding from day 14 onwards. Number of independent experiments (biological replicates, n) were defined as independent differentiations started at least 3 days apart or from a freshly thawed vial of hPSCs.

AAV2-BE transduction in iPSC derived neurons and phenotype observation

FD iPSC-derived sympathetic neurons were transduced with AAV2-BEs. On day 21 of the sympathetic neuron differentiation, viruses were added to Neurobasal media with N2/B27/L-glutamine/GDNF/BDNF/Ascorbic Acid/NGF/dbcAMP/RA. Old media was removed from the sympathetic neuron containing wells, and a low volume of media containing viruses (30 ul/96 well or 250 ul/24 well) was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 6 hours. After 6 hours fresh Neurobasal media with N2/B27/L-glutamine/GDNF/BDNF/Ascorbic Acid/NGF/dbcAMP/RA was added to the wells to increase total media in the wells, so they did not dry out overnight (total 150 ul/96 well or 500 ul/24 well). 24 hours after initial transduction, media containing viruses was removed from the wells and replaced with fresh Neurobasal media with N2/B27/L-glutamine/GDNF/BDNF/Ascorbic Acid/NGF/dbcAMP/RA.

Brightfield images of transduced sympathetic neurons were taken regularly after transduction to monitor neuron growth and any morphological or viability related effect of the viruses. Fluorescent images were taken using the Lionheart FX Automated Microscope to assess effective transduction with AAV2:GFP. To harvest gDNA from sympathetic neurons, five days after transduction, sympathetic neurons were washed with 1X PBS. Then, using a cell scraper, neurons were detached from the plate in ice cold 1X PBS and collected in Eppendorf tubes. Dried cell pellets were then flash frozen and shipped on dry ice for further gDNA processing. Electrical activity of sympathetic neurons was performed as previously described33,34. Briefly, on day 14 of sympathetic neuron differentiations, cells were plated onto 96-well CytoView MEA plates coated with PO/LM/FN. These cells were transduced as described above. Neural activity was measured at the desired timepoints with the Axion Maestro Pro multiwell plate reader using the neural detection mode.

Next-generation sequencing and data analysis

The genome modification efficiencies of nucleases, base editors, and prime editors were determined by next-generation sequencing (NGS) using a 2-step PCR-based Illumina library construction method, similar to as previously described26. Briefly, genomic loci were amplified from approximately 50 ng of gDNA using Q5 High-fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) and the primers (Supplementary Table 4). PCR products were purified using paramagnetic beads prepared as previously described36,37. Approximately 20 ng of purified PCR-1 products were used as template for a second round of PCR (PCR-2) to add barcodes and Illumina adapter sequences using Q5 and primers (Supplementary Table 4) and cycling conditions of 1 cycle at 98 °C for 2 min; 10 cycles at 98 °C for 10 sec, 65 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C 30 sec; and 1 cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified prior to quantification via capillary electrophoresis (Qiagen QIAxcel), normalization, and pooling. Final libraries were quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit (Complete kit; Universal) (Roche) and sequenced on a MiSeq sequencer using a 300- cycle v2 kit (Illumina). On-target genome editing activities were determined from sequencing data using CRISPResso238 using parameters: CRISPResso -r1 READ1 -r2 READ2 --amplicon_seq--amplicon_name --guide_seq GUIDE -w 20 --cleavage_offset −10 for nucleases and CRISPResso -r1 READ1 -r2 READ2 --amplicon_seq --guide_seq GUIDE -w 20 --cleavage_offset −10 --base_editor_output --conversion_nuc_from C --conversion_nuc_to T --min_frequency_alleles_around_cut_to_plot 0.001.

Off-target analysis via GUIDE-seq2

GUIDE-seq2 (Lazzarotto & Li et al, in preparation) is an adapted version of the original GUIDE-seq method28,29. Briefly, approximately 20,000 HEK 293T cells were seeded per well in 96-well plates ~20 hours prior to transfection, performed using 29 ng of nuclease expression plasmid, 12.5 ng of gRNA expression plasmid, 1 pmol of the GUIDE-seq double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide tag (dsODN; oSQT685/686)28,29, and 0.3 μL of TransIT-X2 (Mirus). Genomic DNA was extracted ~72 hours post transfection using the DNAdvance Kit (Beckman Coulter) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and then quantified by Qubit (Thermo Fisher). On-target dsODN integration was assessed by PCR amplification, library preparation, and next-generation sequencing as described above, with data analysis via CRISPREsso238 run in non-pooled mode by supplying the target site spacer, the reference amplicon, and both the forward and reverse dsODN-containing amplicons as ‘HDR’ alleles with custom parameters: -w 25 -g GUIDE --plot_window_size 50. The fraction of alleles bearing an integrated dsODN was calculated as the number of reads mapped to the forward dsODN amplicon plus the number of reads mapped to the reverse dsODN amplicon divided by the sum of the total reads mapped to all three amplicons.

GUIDE-seq2 reactions were performed essentially as described (Lazzarotto & Li et al, in preparation) with minor modifications. Briefly, the Tn5 transposase was prepared by combining 36 μL hyperactive Tn5 (1.85 mg/mL, purified as previously described), 15 μL annealed i5 adapter oligos encoding 8 nucleotide (nt) barcodes and 10-nt unique molecular indexes (UMIs) (Supplementary Table 4), with 52 μL 2x Tn5 dialysis buffer (100 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.2, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 20% glycerol) for 60 minutes at 24 °C. Tagmentation reactions were performed in 40 μL reactions for 7 minutes at 55 °C, containing approximately 250 ng of genomic DNA, 8 μL of the assembled Tn5/i5 -transposome, and 8 μL of freshly prepared 5x TAPS-DMF buffer (50 mM TAPS-NaOH, 25 mM MgCl2, and 50% dimethylformamide (DMF)). Tagmentation reactions were halted using 5 μL of a 50% proteinase K (NEB) solution (mixed with H2O) with incubation at 55 °C for 15 minutes, purified using SPRI-guanidine magnetic beads, and analyzed via TapeStation with High Sensitivity D5000 tapes (Agilent). Separate PCR reactions were performed using dsODN sense- and antisense-specific primers (Supplementary Table 4) using Platinum Taq (Thermo Fisher), with a thermocycler program of 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 15 cycles of temperature cycling (95 °C for 30 s, 70 °C (−1 °C per cycle) for 120 s, and 72 °C for 30 s), 20 constant cycles (95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 30 s), an a final extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes. PCR products were purified using SPRI beads and analyzed via QIAxcel (Qiagen) prior to sample pooling to form single sense- and antisense- libraries. Libraries were purified using the Pippin Prep (Sage Science) DNA size selection system to achieve a size range of 250–500 base pairs. Sense- and antisense- libraries were quantified using Qubit (Thermo Fisher) and pooled in equal amounts to achieve a final concentration of 2 nM. The library was sequenced using NextSeq1000/2000 P3 kit (Illumina) with cycle settings of 146, 8, 18, 146. Demultiplexed sequencing reads were down sampled to ensure equal numbers of reads for samples being compared using the same gRNA. Data analysis was performed using an updated version of the open-source GUIDE-seq2 analysis softwareClick or tap here to enter text. (https://github.com/tsailabSJ/guideseq/tree/V2) with the max_mismatches parameter set to 6.

AAV production

Plasmids encoding TadCBEd-SpG split into N-term and C-terminal fragments via an Npu intein and gRNA C6 for packaging into AAV2 and AAV9 vectors were cloned as previously described24,39,40 (see Supplementary Table 3 for plasmids). AAV2 or AAV9 vectors encoding BEs and gRNAs were produced by PackGene Biotech Inc. or by our local core facility at Grousbeck Gene Therapy Center, Schepens Eye Research Institute and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. AAVs were produced from endo-free plasmid DNA in a triple transfection (ITR-flanked ExspeU1-eGFP, packaging, and Adeno-helper plasmids) in HEK293 cells. After 3 days, the viral vector was isolated from the combined lysate and cell media via sequential high salt, benzonase (for non-AAV protected DNA digestion) treatment, lysate clearing via high-speed centrifugation, Tangential Flow Filtration (for volume reduction and clearing), Iodoxinol gradient ultracentrifugation (for purification and separation of empty vs full particles) and buffer exchange and formulation in PBS via molecular weight cutoff filtration. Preparation was undergone titration via digital droplet PCR, and quality control for purity was assessed via SDS-PAGE.

Mice and AAV-BE treatment in vivo

The generation of the TgFD9 mice carrying the human ELP1 transgene with intron 20 6 T>C mutation was previously generated 30. Control and TgFD9 mice have a mixed background, including C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N. Both sexes were included in this study. The mice were housed in the animal facility at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA), provided with access to food and water ad libitum, and maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Massachusetts General Hospital and were in accordance with NIH guidelines. For routine genotyping of progeny, genomic DNA was prepared from tail biopsies, and PCR was carried out using the following primers - forward, 5`-TGATTGACACAGACTCTGGCCA-3’; reverse, 5`-CTTTCACTCTGAAATTACAGGAAG-3’- to discriminate the ELP1 alleles and the primers - forward 5`-GCCATTGTACTGTTTGCGACT-3’; reverse, 5`-TGAGTGTCACGATTCTTTCTGC-3’- to detect the TgFD9 transgene.

For Intravitreal injection of AAV-BE vectors, TgFD9 mice were anesthetized by placing them in a mobile isoflurane induction chamber, and the vaporizer was set to an isoflurane concentration of 2% at 2 L/min O2. Pupils of the mice were dilated using 2.5% phenylephrine and 1% tropicamide. About 0.5% proparacaine is used as a topical anesthetic during the procedure for 1–2min. Genteal gel was used to keep the eyes moist and avoid corneal dryness and opacities. The body temperature of the mouse was kept stable at 37°C throughout the procedure. Under the control of a stereo microscope (Discovery.V20, Zeiss), an incision was made into the sclera posterior of the superior limbus using a sterile, sharp 30-gauge (G) needle without touching the lens. A microliter Hamilton syringe attached to a 34G blunt needle was carefully inserted into the same incision, and 1 μl of the indicated AAV vector combination (45% N-term, 45% C-term, 10% eGFP) at a total dose of 1.5 × 109 or 1 × 1010 vg was injected slowly into the vitreous using manual pressure. The needle was kept inside the vitreous area for at least 1 minute after the injection to avoid reflux of viral suspension. After the completion of intravitreal AAV injections, triple antibiotic ointment (neomycin, bacitracin, and polymyxin B) was applied, and mice were injected subcutaneously with the analgesic buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg).

For systemic injections, AAV-BE were combined as indicated and injected into the temporal facial vein of neonatal mice (P1-P2) according to a previously described protocol41. Briefly, neonatal mice were immobilized using cryoanesthesia by freezing on wet ice for 30–60s without direct contact. AAV9 N and C terminal vectors were combined at doses of 3 × 1010 or 1.6 × 1011vector genomes (vg)/g diluted in PBS (ThermoFisher Scientific). The pups were monitored for deep anesthesia and were placed under an anatomical microscope. An insulin syringe with a 31-gauge needle (BD, USA), containing an aliquot of the AAV vector was inserted into the temporal vein. Once the content of the syringe was injected into the facial vein. Pups were then warmed with a heat pack to recover from low body temperature and returned to the dam.

Isolation of retinal cell suspension

After dissection, retinas were dissociated into single cells using 45U of papain (Worthington, Cat. #LS003126) solution (1mg L-Cystine, Sigma; 8 KU of DNase I, Affymetrix; in 5 mL DPBS) as previously published32. The retina was then incubated at 37C for 20min, followed by the replacement of buffer with 2mL ovomucoid solution (15 mg ovomucoid, Worthington Biochemical; 15 mg BSA Thermo Fisher Scientific; in 10 mL DPBS) and 500ul deactivated FBS. Following the enzymatic digestion, the retinas were carefully triturated and filtered using 20 mm filter. Trituration steps were repeated with an additional 1mL ovomucoid solution until no tissue was visible. The single cell suspension was then spun down at 300g, 4C for 10 min.

Extraction of gDNA and RNA from mouse tissues

Genomic DNA was extracted from mouse tissues using the Agencourt DNAdvance protocol (Beckman Coulter). Briefly, ~10 to 20 mg frozen tissue samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min prior to treatment. Lysis reactions were performed using LBH lysis buffer, 1 M DTT, and proteinase K (40mg/mL) in 200 μL reactions, incubated overnight (18 to 20 hr) at 55 °C with shaking at 100 RPM. gDNA was purified from lysate using Bind BBE solution containing magnetic beads and performing three washes with 70% ethanol. DNA was eluted in 200 μL of Elution buffer EBA, and the approximate concentrations of gDNA were quantified by Nanodrop.

Brain and liver tissues were removed and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA), using a TissueLyser (Qiagen). Total RNA was extracted using the TRI reagent procedure provided by the manufacturer. The yield, purity, and quality of the total RNA for each sample were determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, reverse transcription was performed using 1 μg of total RNA, Random Primers (Promega), and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen)17,18.

RT-PCR analysis of full-length and mutant ELP1 transcripts

RT-PCR was performed using the cDNA equivalent of 100 ng of starting RNA in a 30-μl reaction, using GoTaq® green master mix (Promega) and 30 amplification cycles (94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s). Human-specific ELP1 primers - forward, 5`- CCTGAGCAG CAATCATGTG −3; reverse, 5`- TACATGGTCTTCGTGACATC-3’- were used to amplify human ELP1 isoform. PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. The relative amounts of WT and mutant (Δ20) ELP1 spliced isoforms in a single PCR were determined using ImageJ and the integrated density value for each band as previously described17,18,30,42. The relative proportion of the WT isoform detected in a sample was calculated as a percentage.

RT-qPCR analysis of full-length and mutant ELP1 transcripts

Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen), using Qiagen TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Similarly, human fibroblasts were collected, and RNA was extracted with QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The yields of the total RNA for each sample were determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. Full-length and mutant ELP1 mRNA expression was quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis using CFX384 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad). Reverse transcription and qPCR were carried out using One Step RT-qPCR (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The mRNA levels of full-length ELP1, mutant Δ20 ELP1 and GAPDH were quantified using Taqman-based RT-qPCR with a cDNA equivalent of 25 ng of starting RNA in a 20-μl reaction. To amplify the full-length ELP1 isoform, FL ELP1 primers forward, 5`- GAGCCCTGGTTTTAGCTCAG −3`; reverse, 5`- CATGCATTCAAATGCCTCTTT −3` and FL ELP1 probe 5`- TCGGAAGTGGTTGGACAAACTTATGTTT-3` were used. To amplify the mutant (Δ20) ELP1 spliced isoforms, Δ20 ELP1 primers forward, 5`- CACAAAGCTTGTATTACAGACT −3`; reverse, 5`- GAAGGTTTCCACATTTCCAAG −3` and Δ20 ELP1 probe 5`- CTCAATCTGATTTATGATCATAACCCTAAGGTG −3` were used to amplify the mutant (Δ20) ELP1 spliced isoforms. The ELP1 forward and reverse primers were each used at a final concentration of 0.4 μM. The ELP1 probes were used at a final concentration of 0.15 μM. Mouse GAPDH mRNA was amplified using 20X gene expression PCR assay (Life Technologies, Inc.). RT-qPCR was carried out at the following temperatures for indicated times: Step 1: 48°C (15 min); Step 2: 95°C (15 min); Step 3: 95°C (15 sec); Step 4: 60°C (1 min); Steps 3 and 4 were repeated for 39 cycles. The Ct values for each mRNA were converted to mRNA abundance using actual PCR efficiencies. ELP1 FL and Δ20 mRNAs were normalized to GAPDH and vehicle controls and plotted as fold change compared to vehicle treatment. Data were analyzed using the SDS software.

Data availability

Primary datasets will be available in Supplementary Table 6. Sequencing datasets will be deposited with the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). Plasmids from this study will be made available through Addgene.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following individuals for their technical contributions: Sabyasachi Das (in vivo injections and tissue collection), Sydnee Dymock (mouse colony maintenance), and Paolo Pigini (PCR splicing analysis). We thank Dr. Alejandra Gonzalez-Duarte and Dr. Horacio Kaufmann of the Dysautonomia Treatment and Evaluation Center at New York University Medical School for their helpful discussions. C.R.R.A was supported by a Charles A. King Trust Postdoctoral Research Fellowship, Bank of America, N.A., Co-Trustees, a James L. and Elisabeth C. Gamble Endowed Fund for Neuroscience Research / Mass General Neuroscience Transformative Scholar Award, a MGH Physician/Scientist Development Award, and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K01NS134784. B.P.K. was supported by an MGH Howard M. Goodman Fellowship, the Kayden-Lambert MGH Research Scholar Award 2023-2028, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DP2CA281401, P01HL142494 and R01NS125353. A.C. is supported by the Knights Templar Eye Foundation career starter grant and funding from the Familial Dysautonomia Foundation. E.M. was supported by the HMS Ruth and Maurice Freeman Award for Pain Research and NIH grants R01NS124561 and R01NS095640. S.A.S. was supported by the NIH grant R01NS095640.

Footnotes

Competing interests

B.P.K., E.M. and C.R.R.A are inventors on a patent application filed by Mass General Brigham (MGB) that describes genome editing technologies to treat FD. B.P.K. and C.R.R.A. are inventors on additional patents or patent applications filed by MGB that describe genome engineering technologies, including to treat SMA. S.A.S. is an inventor on several U.S. and foreign patents and patent applications assigned to the Massachusetts General Hospital, including U.S Patents 8,729,025 and 9,265,766, both entitled “Methods for altering mRNA splicing and treating familial dysautonomia by administering benzyladenine,” filed on August 31, 2012 and May 19, 2014 and related to use of kinetin; and U.S. Patent 10,675,475 entitled, “Compounds for improving mRNA splicing” filed on July 14, 2017 and related to use of BPN-15477. E.M. and S.A.S. are inventors on an International Patent Application Number PCT/US2021/012103, assigned to Massachusetts General Hospital and entitled “ RNA Splicing Modulation” related to use of BPN-15477 in modulating splicing.B.P.K. is a consultant for EcoR1 capital, Novartis Venture Fund, and Jumble Therapeutics, and is on the scientific advisory boards of Acrigen Biosciences, Life Edit Therapeutics, and Prime Medicine. B.P.K. has a financial interest in Prime Medicine, Inc., a company developing therapeutic CRISPR-Cas technologies for gene editing. E.M. is a consultant for ReviR Therapeutics. C.R.R.A is a consultant for Ilios Therapeutics and Biogen and holds stocks in publicly traded companies developing gene therapies. B.P.K. and C.R.R.A interests were reviewed and are managed by MGH and MGB in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policies. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Slaugenhaupt S. A. et al. Tissue-specific expression of a splicing mutation in the IKBKAP gene causes familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 598–605 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slaugenhaupt S. A. Genetics of familial dysautonomia. Clin. Auton. Res. 12, I15–I19 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuajungco M. P. et al. Tissue-specific reduction in splicing efficiency of IKBKAP due to the major mutation associated with familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 749–758 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelrod F. B. & Gold-von Simson G. Hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies: types II, III, and IV. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2, 39 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Duarte A., Cotrina-Vidal M., Kaufmann H. & Norcliffe-Kaufmann L. Familial dysautonomia. Clin. Auton. Res. Off. J. Clin. Auton. Res. Soc. 33, 269–280 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leyne M. et al. Identification of the first non-Jewish mutation in familial Dysautonomia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 118A, 305–308 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Slaugenhaupt S. A. & Kaufmann H. Familial dysautonomia: History, genotype, phenotype and translational research. Prog. Neurobiol. 152, 131–148 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L. & Kaufmann H. Familial dysautonomia (Riley-Day syndrome): when baroreceptor feedback fails. Auton. Neurosci. Basic Clin. 172, 26–30 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Axelrod F. B. & Abularrage J. J. Familial dysautonomia: a prospective study of survival. J. Pediatr. 101, 234–236 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axelrod F. B. & Pearson J. Congenital sensory neuropathies. Diagnostic distinction from familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1960 138, 947–954 (1984). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Familial dysautonomia - Axelrod - 2004. - Muscle & Nerve - Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/mus.10499. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Norcliffe-Kaufmann L., Axelrod F. & Kaufmann H. Afferent baroreflex failure in familial dysautonomia. Neurology 75, 1904–1911 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilz M. J. et al. Assessing function and pathology in familial dysautonomia: assessment of temperature perception, sweating and cutaneous innervation. Brain J. Neurol. 127, 2090–2098 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Axelrod F. B., Nachtigal R. & Dancis J. Familial dysautonomia: diagnosis, pathogenesis and management. Adv. Pediatr. 21, 75–96 (1974). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufmann H. & Biaggioni I. Autonomic failure in neurodegenerative disorders. Semin. Neurol. 23, 351–363 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donadon I. et al. Exon-specific U1 snRNAs improve ELP1 exon 20 definition and rescue ELP1 protein expression in a familial dysautonomia mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 2466–2476 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morini E. et al. Development of an oral treatment that rescues gait ataxia and retinal degeneration in a phenotypic mouse model of familial dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 110, 531–547 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morini E. et al. ELP1 Splicing Correction Reverses Proprioceptive Sensory Loss in Familial Dysautonomia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 638–650 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano G. et al. Rescue of a familial dysautonomia mouse model by AAV9-Exon-specific U1 snRNA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 1534–1548 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salani M. et al. Development of a Screening Platform to Identify Small Molecules That Modify ELP1 Pre-mRNA Splicing in Familial Dysautonomia. SLAS Discov. 24, 57–67 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz A. et al. Reduction of retinal ganglion cell death in mouse models of familial dysautonomia using AAV-mediated gene therapy and splicing modulators. Sci. Rep. 13, 18600 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha R. et al. Antisense oligonucleotides correct the familial dysautonomia splicing defect in IKBKAP transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 4833–4844 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anzalone A. V., Koblan L. W. & Liu D. R. Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 824–844 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alves C. R. R. et al. Optimization of base editors for the functional correction of SMN2 as a treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 118–131 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neugebauer M. E. et al. Evolution of an adenine base editor into a small, efficient cytosine base editor with low off-target activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 673–685 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walton R. T., Christie K. A., Whittaker M. N. & Kleinstiver B. P. Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants. Science 368, 290–296 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koblan L. W. et al. Improving cytidine and adenine base editors by expression optimization and ancestral reconstruction. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 843–846 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai S. Q. et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol 33, 187–197 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malinin N. L. et al. Defining genome-wide CRISPR-Cas genome-editing nuclease activity with GUIDE-seq. Nat. Protoc. 16, 5592–5615 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hims M. M. et al. A humanized IKBKAP transgenic mouse models a tissue-specific human splicing defect. Genomics 90, 389–396 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeltner N. et al. Capturing the biology of disease severity in a PSC-based model of familial dysautonomia. Nat. Med. 22, 1421–1427 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegert S. et al. Transcriptional code and disease map for adult retinal cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 487–495 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H.-F. et al. Norepinephrine transporter defects lead to sympathetic hyperactivity in Familial Dysautonomia models. Nat. Commun. 13, 7032 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu H.-F. et al. Parasympathetic neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells model human diseases and development. Cell Stem Cell 31, 734–753.e8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito-Diaz K. et al. Genipin rescues developmental and degenerative defects in familial dysautonomia models and accelerates axon regeneration. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadq2418 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohland N. & Reich D. Cost-effective, high-throughput DNA sequencing libraries for multiplexed target capture. Genome Res. 22, 939–946 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleinstiver B. P. et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas12a variants with increased activities and improved targeting ranges for gene, epigenetic and base editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 276–282 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clement K. et al. CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 224–226 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramirez S. H. et al. An Engineered Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Mediates Efficient Transduction of Pericytes and Smooth Muscle Cells of the Brain Vasculature. Hum. Gene Ther. 34, 682–696 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanlon K. S. et al. Selection of an Efficient AAV Vector for Robust CNS Transgene Expression. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 15, 320–332 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gombash Lampe S. E., Kaspar B. K. & Foust K. D. Intravenous Injections in Neonatal Mice. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 52037 (2014) doi: 10.3791/52037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shetty R. S. et al. Specific correction of a splice defect in brain by nutritional supplementation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4093–4101 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Primary datasets will be available in Supplementary Table 6. Sequencing datasets will be deposited with the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA). Plasmids from this study will be made available through Addgene.