Abstract

As engineered microbes are used in increasingly diverse applications across human health and bioproduction, the field of synthetic biology will need to focus on strategies that stabilize and contain the function of these populations within target environments. To this end, recent advancements have created layered sensing circuits that can compute cell survival, genetic contexts that are less susceptible to mutation, burden, and resource control circuits, and methods for population variability reduction. These tools expand the potential for real-world deployment of complex microbial systems by enhancing their environmental robustness and functional stability in the face of unpredictable host response and evolutionary pressure.

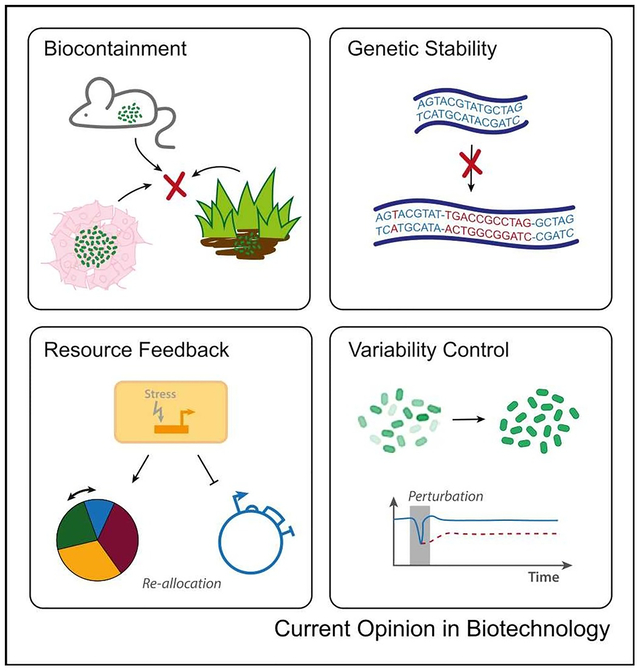

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

With the advancement of genetic circuit engineering and the explosion of microbiome-related research, an expansion in the field of living therapeutics is only natural. Beyond the use of microbes to deliver therapeutic payloads and act as environmental reporters, researchers have created layered functionality for sensing, recording, and treating various human diseases within one system. Recently, deployed bacteria have been used to prevent antibiotic dysbiosis, signal to the immune system, treat metabolic disorders, and sense and record the mouse gut environment [1–5]. Outside of the realm of human health, microbes are extensively used for bioproduction of valued metabolites and fuels. While the uses for and complex functionality of such engineered microbes continue to grow, the field as a whole still faces many challenges concerning deployment of engineered populations into real-world environments. Safe introduction of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) into the environment and their effectiveness outside of the lab, rely on (1) containment of populations and their localized activation, (2) genetic stability of circuitry, (3) mitigation of burden and resource-mediated coupling, and (4) variability reduction due to disturbances or population heterogeneity. In this review, we highlight recent work to tackle each of these fundamental issues and offer our perspective on how to prepare engineered microbes for the next phase.

Containment and environmental activation

To limit engineered microbial function to within a specified environment, many researchers have improved the population’s biosensing capabilities and tied sensor input to population survival or activation. For example, Ishikawa et al. created a pollutant-degrading strain that requires the presence of toluene, the pollutant of interest, for survival [6]. Local ultrasound-based thermal induction has been used to trigger downstream therapeutic output transcriptionally or by recombinase in mouse models [7]. NIR light conversion by microgels has been used to activate gut colonization and therapeutic delivery of EcN externally [8], while thermal switches within cells can discriminate between in vivo fever and release from a mouse, where the cells are subsequently killed [9].

Environmental signals have also been integrated for more complex functions impacting population survival. Foundational work by the Collin’s lab introduced the creation of independent riboregulator switches and the ‘deadman’ and ‘passcode’ motifs that all use layered transcriptional control to compute cell survival based on environment [10,11]. More recently, Chien et al. developed a strain that shows permissive growth in a mouse model only in tumor environments by lactate and hypoxia-driven expression of essential genes [12]. Similarly, bile acid markers in conjunction with an external inducer signal can differentiate between bioproduction, the gut environment, and environmental release [13]. Building upon the original synchronized lysis circuit [14], the inducible synchronized lysis circuit (SLC) was made to allow tunable population dynamics between growth phase, oscillatory phase, and a high-induction kill switch, using p-coumaric acid as a safe ingestible inducer [15]. Other kill switch functions have been developed that encode counters before triggering death [16] or are more evolutionarily resistant through context changes, SOS tolerance, and redundancy [17]. Last, bacterial encapsulation has been used to only allow high-density cell survival in swarmbots or temporary immune invasion for distal tumor delivery, disallowing survival of single wayward cells [18,19].

In addition to the concern of population and cell containment, researchers have also investigated techniques to reduce genetic leakage through horizontal gene transfer into natural microbes. A commonly explored method is the use of genome-reduced and stop codon-expanded strains that cannot create functional proteins following horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of altered genes [20]. Swapped amino acid codes take this further to prevent bidirectional gene transfer of most genes between an organism and its community [21]. Last, splitting a functional locus to create active heterodimers is also a valuable method for HGT prevention [1].

Genetic stability

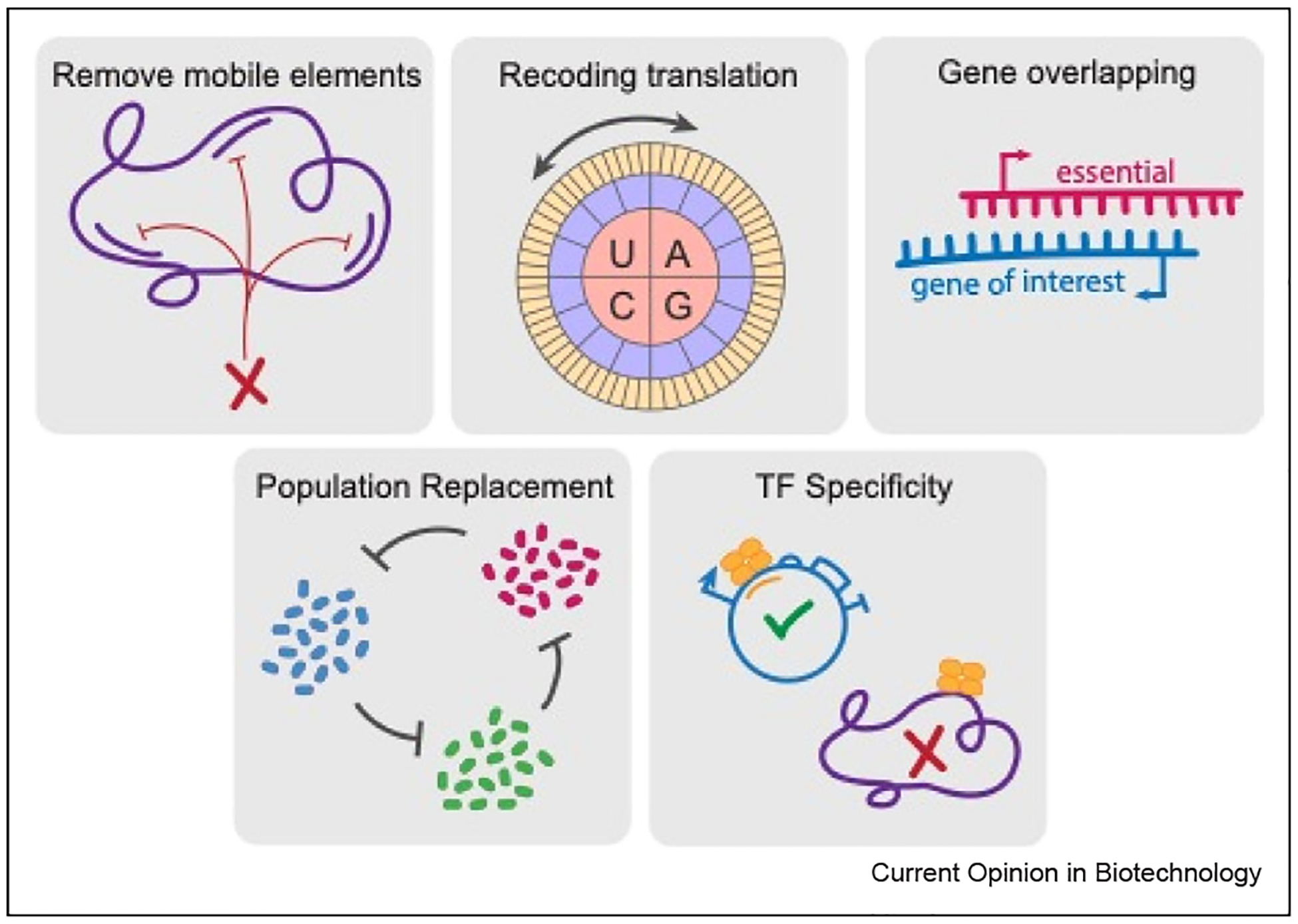

While impressive functionality has been achieved from engineering microbes in the past couple of decades, a major concern that remains is the issue of genetic stability. When newly introduced functions detract from cell survival, mutation and recombination can quickly drive populations away from desired phenotypes. It has been well established that genome integration can considerably improve genetic stability and remove the need for selection markers, however, it can be difficult to generate robust circuit output within the genomic context. Recently, researchers have managed to solve this problem with the application of automated construct design and the use of insulated, high-expression genomic sites [22]. Automated design has also enabled the development of a large toolbox of nonrepetitive genetic parts that can create circuits much less susceptible to homologous recombination [23]. To prevent disruption of engineered function and reduce evolutionary pressure, many complimentary approaches have been explored, as highlighted in Figure 1. Some groups have reduced general mutational capacity by creating clean genome hosts that lack mobile elements [24], altering RNA polymerases and RNAses to reduce plasmid mutation rates [25], and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based silencing of transposon families [26]. Similarly, commonly recurring single-bp mutations could be targeted in the mouse gut with specific CRISPR guide RNAs [27]. A clever strategy to reduce mutation of toxic or burdensome genes is to overlap these sequences with those of an essential gene, effectively counterbalancing evolutionary pressures [28,29]. Circuit function has also been stabilized in yeast by using multivalent zinc finger transcriptional regulators (TRs) whose enhanced specificity reduces fitness costs on the host genome [30]. One simulation-based study suggested the creation of new ‘fail-safe’ genetic codes that use fewer tRNAs to map mutations in codons into null codons [31]. Of course, in a laboratory setting, the ideal way to prevent long-term genetic instability is to constantly reseed your engineered population. While this is difficult in a real-world deployment, Liao et al. showed that a ‘rock-paper-scissors’ dynamic ecology was able to stabilize a lysis circuit through cyclic replacement [32].

Figure 1.

Methods for stabilization of synthetic circuitry against evolutionary pressure. (Top) Removal of mobile elements from the genome can prevent transposon-caused gene interruption, Umenhoffer et al. and Geng et al. Recoding amino acids can prevent protein gain-of-function mutation, Calles et al. Overlapping genes of interest with essential genes for survival can protect against mutation, Decrulle et al. and Blazejewski et al. (Bottom) Reseeding populations by sequentially alternating ecologies can enhance long-term circuit function, Liao et al. Improved transcription factor specificity to prevent off-target binding can reduce host growth defects and therefore reduce evolutionary pressure, Bragdon et al.

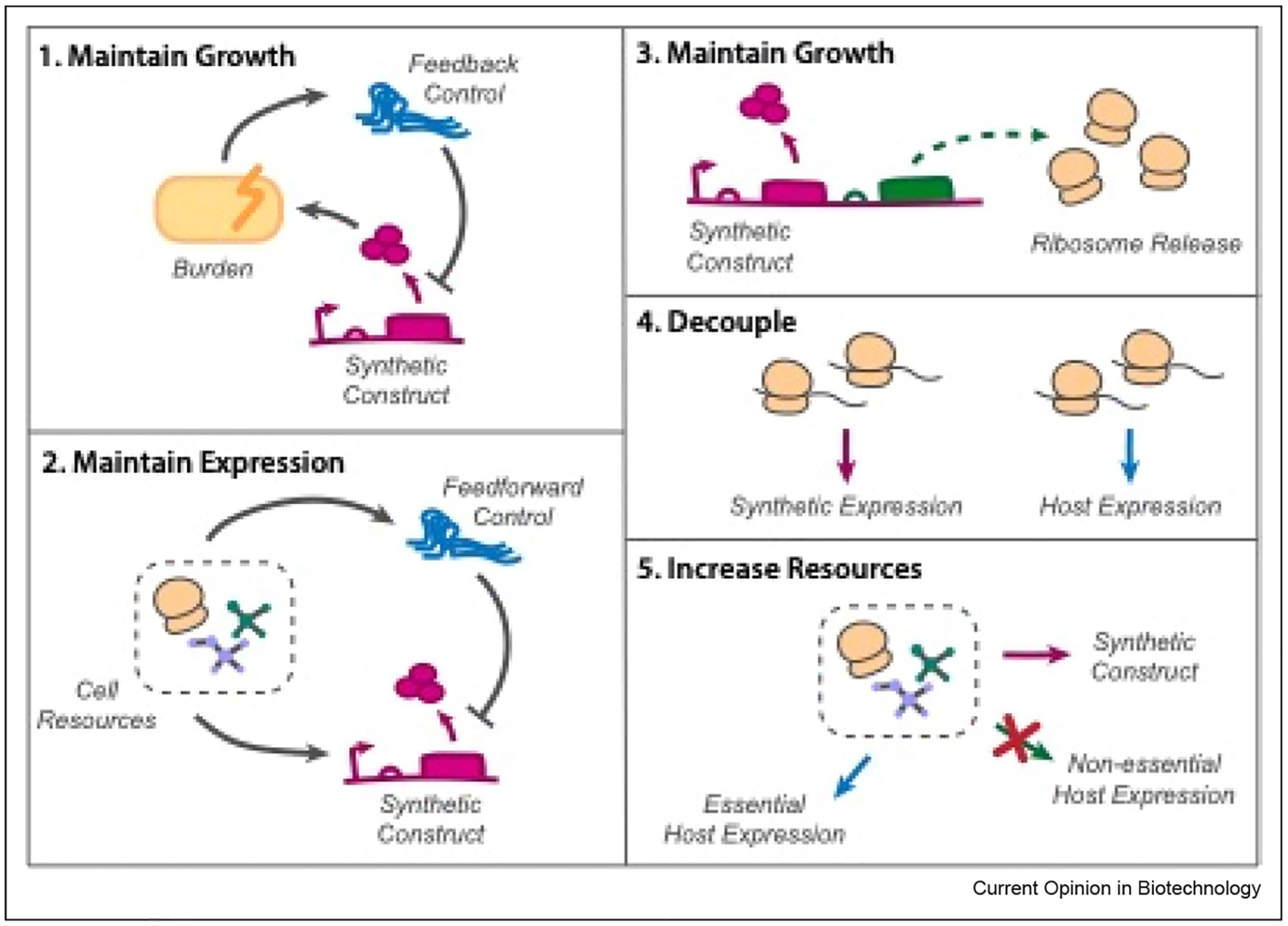

Burden mitigation and feedback control

The above methods to improve genetic stability combat the selective pressure against heterologous gene function, however, another option is to directly reduce this selective pressure. Oftentimes, expression of synthetic cassettes can lead to growth defects and stress on engineered populations. Growth feedback from such host-circuit coupling can have unexpected effects on circuit function and can increase or decrease robustness, stability, and sensitivity based on network topology, not to mention lead to mutation [33]. One potential strategy is to reduce the burden of these circuits by integrating them into insulated genomic landing pads that do not impact native host transcription, as mentioned above [22]. Division of labor using microbial consortia can spread burdensome expression across the population as explored extensively by You’s group and summarized further in their recent review [34,35]. Alternatively, researchers have used a chromosomal origin-removing switch to decouple population growth phase from production, although this would not work for long-term dynamic applications [36].

A method that has risen in popularity recently is the use of burden-based feedback for resource reallocation, one of the first instances of which was created by Ceroni et al. This group used stress-responsive promoters to drive Cas9 repression of overly burdensome-expressed genes [37]. Others have created inducible or quorum-based induction of similar stress and feedback promoters [38]. Rather than repression of a gene of interest (GOI) in response to burden, in their latest paper, Barajas et al. actually couple gene activation to a release of extra ribosomes to prevent reduced growth rate [39]. Incoherent feedforward loops are an established control motif that has been applied to compensate for resource loading from a gene of interest, using endoribonucleases or miRNAs for feedback repression in mammalian cells [40,41]. These constructs in particular aim to uncouple synthetic expression from resource availability to maintain robust expression. By using just a few transcription factor mutations that reduce nonessential protein production, researchers have also been able to directly increase cellular resources for heterologous expression [42]. By a similar vein, the Arkin lab developed a method to degrade the global cellular transcriptome using MazF in order to release resources for a synthetic circuit and a few protected genes [43].

Beyond resource reallocation, another way to account for the burden generated by expressed constructs is using orthogonal resource pools, where heterologous expression uses separate ribosomes. These ribosomes allow for dynamically controlled circuit-specific resource pools that can reduce coupling and increase engineered production [44]. Kolber et al. were able to improve efficiency of such orthogonal machinery by hybridizing ribosomes from other species with sections of the E. coli ribosome [45]. Recent advances to mitigate burden, decouple resource loading, and improve growth of strains expressing synthetic constructs are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Recent developments in resource and burden-based feedback control. (1) Burden-based feedback reduction of costly synthetic constructs to maintain strain growth, Ceroni et al. (2) Resource-based iFFL to maintain constant expression, despite changing cell resource availability, Jones et al. and Frei et al. (3) Compensate for synthetic construct loading by releasing extra ribosomes, Barajas et al. (4) Decouple synthetic and host expression using orthogonal ribosome pools, Darlington et al. and Kolber et al. (5) Increase available resources for synthetic expression by reducing nonessential host expression, Lastiri-Pancardo et al. and Venturelli et al.

Variability reduction of circuit outputs and within populations

The final concern we address regarding realistic deployment of engineered microbial populations is the issue of variability. This variability can lead to unpredictable circuit function in response to external disturbances from the environment or can be the result of nongenetic heterogeneity between individuals.

Many researchers well versed in control theory have designed circuit motifs that allow robust adaptation to cellular resource changes through application of incoherent feedforward loops or sequestration-based control. Sootla et al. demonstrated the theoretical use of signal sequestration to create a robust controller [46], while another research group experimentally reduced copy number variation of transfected plasmids in mammalian cells using an iFFL motif [47]. By a similar concept, the Voigt lab generated constant gene expression control in bacteria using TALE-activated promoters that showed nearly identical expression, regardless of genetic context, copy number, and growth condition [48]. Two groups explicitly developed methods for perfect adaptation to environmental disturbance and even parameter and network perturbation by two differing network architectures. One method used two-node negative feedback coupled to weak positive feedback to show impressive adaptation within bacterial systems [49]. Researchers in the Khammash lab developed an Antithetic integral feedback circuit in mammalian cells that used RNA sequestering to show robust perfect adaptation to network and resource perturbations, as well as reduced variance overall [50].

In addition to combating variability through added control layers, some groups, particularly in application to metabolic engineering, have demonstrated a concept known as population quality control where the best individual performers in a population are selected for. A pioneering study, Xiao et al. were one of the first to show that linking high production to an individual growth advantage could improve population quality and therefore overall production [51]. Since then, numerous research groups have shown improved yields by population product addiction for the formation of naringenin and GlcNac in yeast and NeuAc production in B. subtilis, among other pathways, where the expression of essential genes is coupled to product biosensing [52–54]. Employing a spatially separated strategy, Stella et al. were able to remove cheaters from a branched chain amino acid-producing population as well [55]. Multistrain ecologies have also been used particularly for tryptophan-reliant production where the first strain is under growth-production coupling of tryptophan, while the second strain is responsible for final end-product conversion into tryptamine or indigo [56,57]. Last, expanding beyond nongenetic population selection, adaptive laboratory evolution can apply product-growth coupling to mutationally evolved strains for strain engineering of best producers [58]. All of the above methods showed impressive improvements in the production of valuable metabolites through the coupling of cell survival to synthetic production. These strategies, however, are reliant on the use of inducible essential genes or repressible toxins within their circuits, both of which are vulnerable to mutational escape over generations. The higher the selective pressure to escape, the more likely for mutational breaking of product-growth coupling. One way to get around this evolutionary susceptibility is for the product of interest to be directly required in a reaction for cell survival, not just as a signal for inducible survival. For example, Noh et al. removed the coenzyme B12-independent gene for methionine synthesis forcing the creation of coenzyme B12 for cell survival [59]. Here, the desired functionality of an engineered population is also necessary for that population’s survival and cannot be easily circumvented.

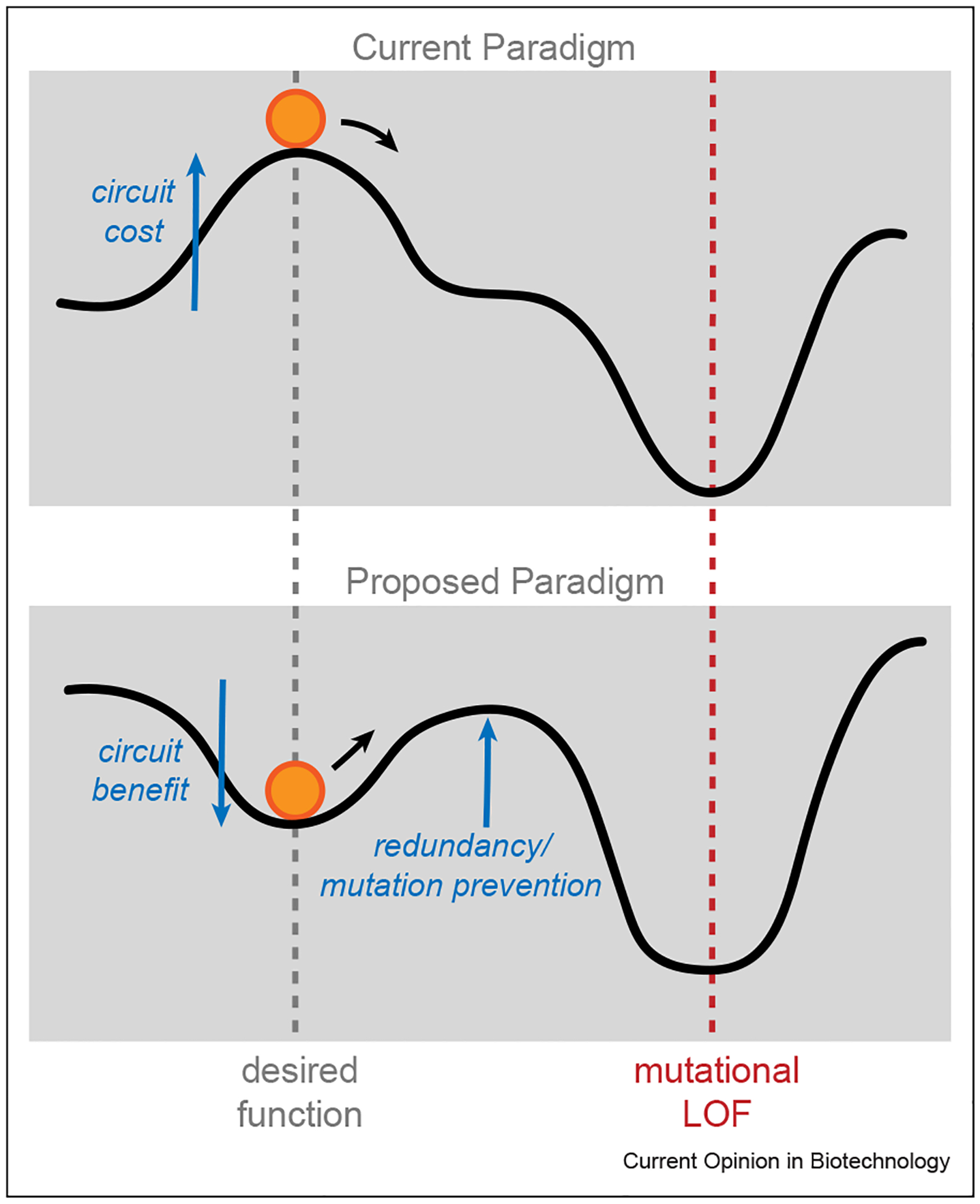

Concluding perspectives

In this review, we highlight recent advancements in the field of synthetic biology that improve the robustness, stability, and containment of engineered microbial populations toward real- world deployment. Some impressive work includes the development of environmentally specific permissive growth, mutation-resistant recoded or reduced genomes, burden-based feedback control, perfect-adaptation networks, and population product addiction. Together, this research begins to prepare synthetic organisms for realized use, however, many of the control mechanisms introduced above are still vulnerable to evolutionary loss of function. The stricter the selection criteria for organism control, the higher the risk of mutation. The most promising designs in our view actually reduce the chance of mutational escape through context-aware whole-cell burden minimization, division of labor within consortia, and clever rearrangement of host genomes.

An even more impressive feat is the positive alignment of evolutionary pressure in the direction of desired synthetic capability, meaning that engineered functionality given to a cell is in fact in some part beneficial (Figure 3). This idea was applied for the host essential production of coenzyme B12, however, it could be expanded for a wide variety of potential applications. Imagine if successful killing of tumor cells in vivo by microbes resulted in access to a new favorable niche or similarly if degradation of environmental pollutants gave engineered cells a fitness advantage over wild-type community members. Although such strategies may come with new containment issues of their own, alignment of microbial evolution with our own interests seems like an overarching stabilization strategy worth considering. Taking it a step further, instead of adding layers of control circuitry to tightly regulate these bacterial workers, it may be beneficial in some scenarios to harness population variability. In nature, for example, heterogeneity is a tool used for population adaptation in fluctuating environments or division of labor within one clonal population. While these counterintuitive strategies may not be applicable in all cases, synthetic design that harnesses the inherent variability of living things and their ability to dynamically evolve and adapt could lead to a new generation of engineered organisms with untapped capabilities.

Figure 3.

Proposed general method for stabilizing engineered microbes for long-term deployment. (Top) Most synthetic constructs induce a cost to the cell that is unstable in the face of evolutionary pressure. (Bottom) The use of redundancy and other mutation prevention methods described in the Genetic stability selection can slow down evolutionary loss of function, however, designing circuits that construe a benefit to the cell can reduce evolutionary pressure overall.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant no. R01GM069811). S.K. was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under grant no. DGE-2038238. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. S.K. was also supported by the NIH-sponsored Quantitative Integrative Biology Training Grant (grant no. 5T32GM127235). The authors thank James J. Collins for critical reading of the paper.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships that may be considered as potential competing interests: J.H. is a cofounder of GenCirq Inc, which focuses on cancer therapeutics. He is on the Board of Directors and has equity in GenCirq.

Data availability

No data were used for the research described in the article.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

•• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Cubillos-Ruiz A, Alcantar MA, Donghia NM, Cárdenas P, Avila-Pacheco J, Collins JJ: An engineered live biotherapeutic for the prevention of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis. Nat Biomed Eng 2022, 6:910–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurbatri CR, Lia I, Vincent R, Coker C, Castro S, Treuting PM, Hinchliffe TE, Arpaia N, Danino T: Engineered probiotics for local tumor delivery of checkpoint blockade nanobodies. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12:eaax0876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent RL, Gurbatri CR, Redenti A, Coker C, Arpaia N, Danino T: Probiotic-guided CAR-T cells for universal solid tumor targeting. bioRxiv 2021, 10.1101/2021.10.10.463366〉 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riglar DT, Giessen TW, Baym M, Kerns SJ, Niederhuber MJ, Bronson RT, Kotula JW, Gerber GK, Way JC, Silver PA: Engineered bacteria can function in the mammalian gut long-term as live diagnostics of inflammation. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35:653–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isabella VM, Ha BN, Castillo MJ, Lubkowicz DJ, Rowe SE, Millet YA, Anderson CL, Li N, Fisher AB, West KA, et al. : Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:857–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishikawa M, Kojima T, Hori K: Development of a biocontained toluene-degrading bacterium for environmental protection. Microbiol Spectr 2021, 9:e0025921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abedi MH, Yao MS, Mittelstein DR, Bar-Zion A, Swift MB, Lee-Gosselin A, Barturen-Larrea P, Buss MT, Shapiro MG: Ultrasound-controllable engineered bacteria for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2022, 13:1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui M, Sun T, Li S, Pan H, Liu J, Zhang X, Li L, Li S, Wei C, Yu C, et al. : NIR light-responsive bacteria with live bio-glue coatings for precise colonization in the gut. Cell Rep 2021, 36:109690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piraner DI, Abedi MH, Moser BA, Lee-Gosselin A, Shapiro MG: Tunable thermal bioswitches for in vivo control of microbial therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callura JM, Dwyer DJ, Isaacs FJ, Cantor CR, Collins JJ: Tracking, tuning, and terminating microbial physiology using synthetic riboregulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010, 107:15898–15903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CTY, Lee JW, Cameron DE, Bashor CJ, Collins JJ: “Deadman” and “Passcode” microbial kill switches for bacterial containment. Nat Chem Biol 2016, 12:82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.••.Chien T, Harimoto T, Kepecs B, Gray K, Coker C, Hou N, Pu K, Azad T, Nolasco A, Pavlicova M, et al. : Enhancing the tropism of bacteria via genetically programmed biosensors. Nat Biomed Eng 2022, 6:94–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Engineered microbes with permissive growth condition specific to tumors. Lactate and hypoxia sensors drove essential gene expression in an in vivo tumor model.

- 13.Taketani M, Zhang J, Zhang S, Triassi AJ, Huang Y-J, Griffith LG, Voigt CA: Genetic circuit design automation for the gut resident species Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38:962–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Din MO, Danino T, Prindle A, Skalak M, Selimkhanov J, Allen K, Julio E, Atolia E, Tsimring LS, Bhatia SN, et al. : Synchronized cycles of bacterial lysis for in vivo delivery. Nature 2016, 536:81–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miano A, Liao MJ, Hasty J: Inducible cell-to-cell signaling for tunable dynamics in microbial communities. Nat Commun 2020, 11:1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stirling F, Naydich A, Bramante J, Barocio R, Certo M, Wellington H, Redfield E, O’Keefe S, Gao S, Cusolito A, et al. : Synthetic cassettes for pH-mediated sensing, counting, and containment. Cell Rep 2020, 30:3139–3148.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rottinghaus AG, Ferreiro A, Fishbein SRS, Dantas G, Moon TS: Genetically stable CRISPR-based kill switches for engineered microbes. Nat Commun 2022, 13:672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang S, Lee AJ, Tsoi R, Wu F, Zhang Y, Leong KW, You L: Coupling spatial segregation with synthetic circuits to control bacterial survival. Mol Syst Biol 2016, 12:859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harimoto T, Hahn J, Chen Y-Y, Im J, Zhang J, Hou N, Li F, Coker C, Gray K, Harr N, et al. : A programmable encapsulation system improves delivery of therapeutic bacteria in mice. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40:1259–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrido V, Piñero-Lambea C, Rodriguez-Arce I, Paetzold B, Ferrar T, Weber M, Garcia-Ramallo E, Gallo C, Collantes M, Peñuelas I, et al. : Engineering a genome-reduced bacterium to eliminate Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in vivo. Mol Syst Biol 2021, 17:e10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.•.Fujino T, Tozaki M, Murakami H: An amino acid-swapped genetic code. ACS Synth Biol 2020, 9:2703–2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Swapped the codon sequences for a few amino acids to create bi-directional genetic firewall. External protein sequences will be nonfunctional in this orthogonal translation system and vice versa.

- 22.Park Y, Espah Borujeni A, Gorochowski TE, Shin J, Voigt CA: Precision design of stable genetic circuits carried in highly-insulated E. coli genomic landing pads. Mol Syst Biol 2020, 9584., 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hossain A, Lopez E, Halper SM, Cetnar DP, Reis AC, Strickland D, Klavins E, Salis HM: Automated design of thousands of nonrepetitive parts for engineering stable genetic systems. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38:1466–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umenhoffer K, Draskovits G, Nyerges Á, Karcagi I, Bogos B, Tímár E, Csörgő B, Herczeg R, Nagy I, Fehér T, et al. : Genome-wide abolishment of mobile genetic elements using genome shuffling and CRISPR/Cas-assisted MAGE allows the efficient stabilization of a bacterial chassis. ACS Synth Biol 2017, 6:1471–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deatherage DE, Leon D, Rodriguez ÁE, Omar SK, Barrick JE: Directed evolution of Escherichia coli with lower-than-natural plasmid mutation rates. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46:9236–9250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geng P, Leonard SP, Mishler DM, Barrick JE: Synthetic genome defenses against selfish DNA elements stabilize engineered bacteria against evolutionary failure. ACS Synth Biol 2019, 8:521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavez A, Pruitt BW, Tuttle M, Shapiro RS, Cecchi RJ, Winston J, Turczyk BM, Tung M, Collins JJ, Church GM: Precise Cas9 targeting enables genomic mutation prevention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018, 115:3669–3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.••.Decrulle AL, Frénoy A, Meiller-Legrand TA, Bernheim A, Lotton C, Gutierrez A, Lindner AB: Engineering gene overlaps to sustain genetic constructs in vivo. PLoS Comput Biol 2021, 17:e1009475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Computationally designed sequence overlaps between an essential gene and a gene of interest to protect. Showed experimentally the prevention of loss of function mutations through this entanglement.

- 29.Blazejewski T, Ho H-I, Wang HH: Synthetic sequence entanglement augments stability and containment of genetic information in cells. Science 2019, 365:595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bragdon MDJ, Patel N, Chuang J, Levien E, Bashor CJ, Khalil AS: Cooperative assembly confers regulatory specificity and long-term genetic circuit stability. bioRxiv 2022, 10.1101/2022.05.22.492993〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calles J, Justice I, Brinkley D, Garcia A, Endy D: Fail-safe genetic codes designed to intrinsically contain engineered organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47:10439–10451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao MJ, Din MO, Tsimring L, Hasty J: Rock-paper-scissors: engineered population dynamics increase genetic stability. Science 2019, 365:1045–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang R, Li J, Melendez-Alvarez J, Chen X, Sochor P, Goetz H, Zhang Q, Ding T, Wang X, Tian X-J: Topology-dependent interference of synthetic gene circuit function by growth feedback. Nat Chem Biol 2020, 16:695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Zhang X, Tang C, Li P, Zhu R, Sun J, Zhang Y, Cui H, Ma J, Song X, et al. : Engineering consortia by polymeric microbial swarmbots. Nat Commun 2022, 13:3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duncker KE, Holmes ZA, You L: Engineered microbial consortia: strategies and applications. Microb Cell Factories 2021, 20:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasari M, Kasari V, Kärmas M, Jõers A: Decoupling growth and production by removing the origin of replication from a bacterial chromosome. ACS Synth Biol 2022, 11:2610–2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ceroni F, Boo A, Furini S, Gorochowski TE, Borkowski O, Ladak YN, Awan AR, Gilbert C, Stan G-B, Ellis T: Burden-driven feedback control of gene expression. Nat Methods 2018, 15:387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glasscock CJ, Biggs BW, Lazar JT, Arnold JH, Burdette LA, Valdes A, Kang M-K, Tullman-Ercek D, Tyo KEJ, Lucks JB: Dynamic control of gene expression with riboregulated switchable feedback promoters. ACS Synth Biol 2021, 10:1199–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barajas C, Huang H-H, Gibson J, Sandoval L, Vecchio DD: Feedforward ribosome control mitigates gene activation burden. bioRxiv 2022, 10.1101/2021.02.11.430724〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.••.Jones RD, Qian Y, Siciliano V, DiAndreth B, Huh J, Weiss R, Del Vecchio D: An endoribonuclease-based feedforward controller for decoupling resource-limited genetic modules in mammalian cells. Nat Commun 2020, 11:5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Use of an iFFL motif to increase robustness of a synthetic circuit against resource loading in various mammalian cell lines, including human. Specifically used the CasE endoribonuclease to control synthetic output under same promoter.

- 41.••.Frei T, Cella F, Tedeschi F, Gutiérrez J, Stan G-B, Khammash M, Siciliano V: Characterization and mitigation of gene expression burden in mammalian cells. Nat Commun 2020, 11:4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Model-informed design of an iFFL motif that instead uses synthetic or endogenous miRNA-based control. Have extensive characterization of cellular burden and show enhanced synthetic output robustness in various mammalian cell lines.

- 42.Lastiri-Pancardo G, Mercado-Hernández JS, Kim J, Jiménez JI, Utrilla J: A quantitative method for proteome reallocation using minimal regulatory interventions. Nat Chem Biol 2020, 16:1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venturelli OS, Tei M, Bauer S, Chan LJG, Petzold CJ, Arkin AP: Programming mRNA decay to modulate synthetic circuit resource allocation. Nat Commun 2017, 8:15128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darlington APS, Kim J, Jiménez JI, Bates DG: Dynamic allocation of orthogonal ribosomes facilitates uncoupling of co-expressed genes. Nat Commun 2018, 9:695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kolber NS, Fattal R, Bratulic S, Carver GD, Badran AH: Orthogonal translation enables heterologous ribosome engineering in E. coli. Nat Commun 2021, 12:599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sootla A, Delalez N, Alexis E, Norman A, Steel H, Wadhams GH, Papachristodoulou A: Dichotomous feedback: a signal sequestration-based feedback mechanism for biocontroller design. J R Soc Interface 2022, 19:20210737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, Lee J, Land MA, Lai S, Igoshin OA, St-Pierre F: A synthetic circuit for buffering gene dosage variation between individual mammalian cells. Nat Commun 2021, 12:4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segall-Shapiro TH, Sontag ED, Voigt CA: Engineered promoters enable constant gene expression at any copy number in bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun Z, Wei W, Zhang M, Shi W, Zong Y, Chen Y, Yang X, Yu B, Tang C, Lou C: Synthetic robust perfect adaptation achieved by negative feedback coupling with linear weak positive feedback. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50:2377–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.•.Frei T, Chang C-H, Filo M, Arampatzis A, Khammash M: A genetic mammalian proportional–integral feedback control circuit for robust and precise gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2022, 119:e2122132119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Use mRNA-based sequestration to build antithetic integral feedback circuit experimentally in mammalian cells. This motif generates perfect adaptation to environmental and network disturbances. Also use proportional-integral feedback to reduce output variance overall.

- 51.Xiao Y, Bowen CH, Liu D, Zhang F: Exploiting nongenetic cell-to-cell variation for enhanced biosynthesis. Nat Chem Biol 2016, 12:339–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao Y, Tian R, Lv X, Li J, Liu L, Du G, Chen J, Liu Y: Inducible population quality control of engineered Bacillus subtilis for improved N -Acetylneuraminic acid biosynthesis. ACS Synth Biol 2021, 10:2197–2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lv Y, Gu Y, Xu J, Zhou J, Xu P: Coupling metabolic addiction with negative autoregulation to improve strain stability and pathway yield. Metab Eng 2020, 61:79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.•.Lee S-W, Rugbjerg P, Sommer MOA: Exploring selective pressure trade-offs for synthetic addiction to extend metabolite productive lifetimes in yeast. ACS Synth Biol 2021, 10:2842–2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Create GlcNac product addiction of yeast by inversely coupling it to fluorocytosine toxicity. Explain trade-offs in such designs between selection pressure causing better performance but greater chance of recombination and resistance formation.

- 55.Stella RG, Gertzen CGW, Smits SHJ, Gätgens C, Polen T, Noack S, Frunzke J: Biosensor-based growth-coupling and spatial separation as an evolution strategy to improve small molecule production of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab Eng 2021, 68:162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen T, Wang X, Zhuang L, Shao A, Lu Y, Zhang H: Development and optimization of a microbial co-culture system for heterologous indigo biosynthesis. Microb Cell Factories 2021, 20:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, Policarpio L, Prajapati D, Li Z, Zhang H: Developing E. coli-E. coli co-cultures to overcome barriers of heterologous tryptamine biosynthesis. Metab Eng Commun 2020, 10:e00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seok JY, Han YH, Yang J-S, Yang J, Lim HG, Kim SG, Seo SW, Jung GY: Synthetic biosensor accelerates evolution by rewiring carbon metabolism toward a specific metabolite. Cell Rep 2021, 36:109589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.•.Noh MH, Lim HG, Moon D, Park S, Jung GY: Auxotrophic selection strategy for improved production of coenzyme B12 in Escherichia coli. iScience 2020, 23:100890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Improved the production of coenzyme B12 by making it required for cell survival through removal of the B12-independent methionine synthesis pathway. A product addiction strategy that does not require indirect repression of toxins or induction of essential genes.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.