Abstract

Structural and functional studies of the carminomycin 4-O-methyltransferase DnrK are described, with an emphasis on interrogating the acceptor substrate scope of DnrK. Specifically, the evaluation of 100 structurally and functionally diverse natural products and natural product mimetics revealed an array of pharmacophores as productive DnrK substrates. Representative newly identified DnrK substrates from this study included anthracyclines, angucyclines, anthraquinone-fused enediynes, flavonoids, pyranonaphthoquinones, and polyketides. The ligand-bound structure of DnrK bound to a non-native fluorescent hydroxycoumarin acceptor, 4-methylumbelliferone, along with corresponding DnrK kinetic parameters for 4-methylumbelliferone and native acceptor carminomycin are also reported for the first time. The demonstrated unique permissivity of DnrK highlights the potential for DnrK as a new tool in future biocatalytic and/or strain engineering applications. In addition, the comparative bioactivity assessment (cancer cell line cytotoxicity, 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, and axolotl embryo tail regeneration) of a select set of DnrK substrates/products highlights the ability of anthracycline 4-O-methylation to dictate diverse functional outcomes.

Graphical Abstract:

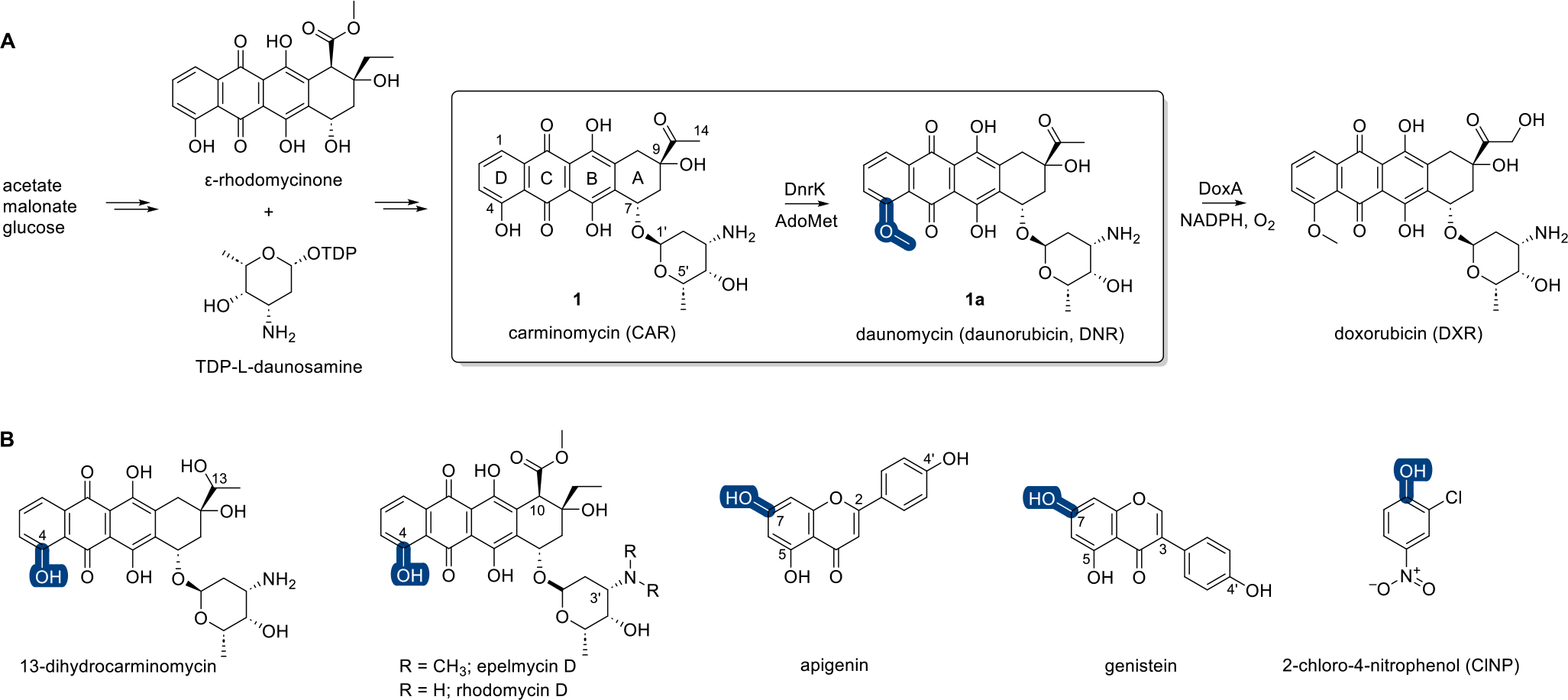

Daunorubicin (DNR, 1a, also known as daunomycin) and the 14-hydroxy derivative doxorubicin (DXR, adriamycin) (Figure 1A) are anthracycline-based microbial natural products that have been used effectively to treat cancer for over four decades.1 DNR and DXR are potent topoisomerase II inhibitors, and both also induce free radical species that contribute to cumulative dose-limiting cardiotoxicity.1–3 The producing strain for DNR (Streptomyces peucetius) was first isolated in the 1950s from a sample collected near a 13thcentury castle in the Apulia region of southern Italy.4 Subsequent N-nitroso-N-methylurea-based mutagenesis of this DNR producer led to the first DXR-producing variant.5,6 DNR and DXR and their producing strains subsequently served as early prototypical models that enabled many pioneering discoveries relating to aromatic polyketide and uniquely functionalized deoxysugar genetics and biosynthesis.7,8 These studies revealed DNR biosynthesis to culminate with carminomycin (CAR, 1) methyltransferase (MT)-catalyzed 4-O-methylation and subsequent DNR P450 hydroxylase-catalyzed C-14-hydroxylation to afford DXR.9–11 Strohl and co-workers were the first to demonstrate the S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)-dependent 4-O-methylation reaction in vitro using crude extracts from several daunomycin-producing strains and also were the first to report preliminary biochemical studies of the native CAR 4-O-MT purified from Streptomyces sp. strain C5.12 Subsequent genetic studies led to the discovery of the genes encoding the CAR 4-O-MT (dnrK from S. peucetius and dauK from Streptomyces sp. strain C5)11,13 and opened the door to heterologous overproduction strains and bioconversion studies.13–15 For example, the use of dnrK in heterologous strain engineering enabled production of non-native hybrid natural products as exemplified by the production of 4-O-methylepelmycin D by heterologous expression of dnrK in epelmycin-producing S. violaceus (Figure 1B).16 Heterologous overproduction of DnrK in E. coli by Hutchinson and co-workers set the stage for mechanistic, structural, and biocatalysis applications.14 Representative highlights include observed biocatalytic rate improvements with immobilized DnrK,17,18 new MT mechanistic insights based on determined DnrK ligand-bound structures,18,19 and structure-based engineering such as the rational design of RdmB-like AdoMet-dependent monooxygenases from DnrK.20

Figure 1.

A, Overview of the final steps of DNR (1a) and DXR biosynthesis with emphases on the DnrK-catalyzed methylation reaction (box) and DnrK regioselectivity (blue). B, Previously reported DnrK or DauK substrates with MT regioselectivity highlighted (blue).

The foundational DnrK structures also enabled computational docking studies as the basis for the discovery of new DnrK methyl acceptors. These studies implicated prototypical flavones and isoflavones as putative substrates and confirmed facile DnrK turnover of apigenin and genistein (Figure 1B).21 Inspired by the demonstrated ability of DnrK to methylate simpler non-anthracycline substrates, we recently reported a simple colorimetric assay for DnrK based on the substrate surrogate 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol (ClNP) (Figure 1B).22 Ternary complex structure elucidation with DnrK, ClNP, and a stabilized AdoMet isosteric substrate AdotMet also revealed the capacity of the DnrK active site to accommodate larger and/or more diverse methyl acceptors. To build on this observation and interrogate DnrK permissivity, herein we describe evaluation of 100 structurally and functionally diverse natural products and natural product mimetics of wide-ranging architectural complexity as potential DnrK substrates. Included in the demonstrated DnrK substrates is 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MeUmb, 75, a fluorescent hydroxycoumarin drug frequently used as a real-time fluorescent indicator in enzyme assays)23,24 and a range of complex natural products including anthracyclines, angucyclines, anthraquinone-fused enediynes, flavonoids, pyranonaphthoquinones, and polyketides. This study also provides previously undetermined DnrK kinetic parameters and a comparative evaluation of the impact of anthracycline 4-O-methylation on cancer cell line cytotoxicity, 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, and axolotl embryo tail regeneration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

DnrK Non-native Acceptor Scope.

A representative set of 100 structurally diverse hydroxy-aromatic natural products or natural mimetics were assessed as putative acceptors in the presence of DnrK and AdoMet. Assays were analyzed via LC-MS with new methylated products identified by a change in mass (monomethylation Δm/z = +14, dimethylation Δm/z = +28, and trimethylation Δm/z = +42) and retention time compared to control in the absence of DnrK. The native substrate CAR (1) and the previously reported non-native substrate ClNP (kcat = 0.019 ± 0.001 min−1, Km = 106 ± 10 μM under saturating [AdoMet])22 were included as positive controls. Since the kinetic parameters for DnrK with native substrate CAR (1) had not been previously reported, these values were determined as part of this study (CAR kcat = 0.65 ± 0.03 min−1, Km = 50 ± 2 μM under saturating [AdoMet]). DnrK catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) with CAR (1) was found to be nearly 2 orders of magnitude greater (77-fold) than that of the non-native acceptor ClNP (Table S1), primarily due to a notable difference in kcat. For comparison, the catalytic efficiencies for typical AdoMet-dependent MTs range from ~10 to 7200 M−1 s−1.25

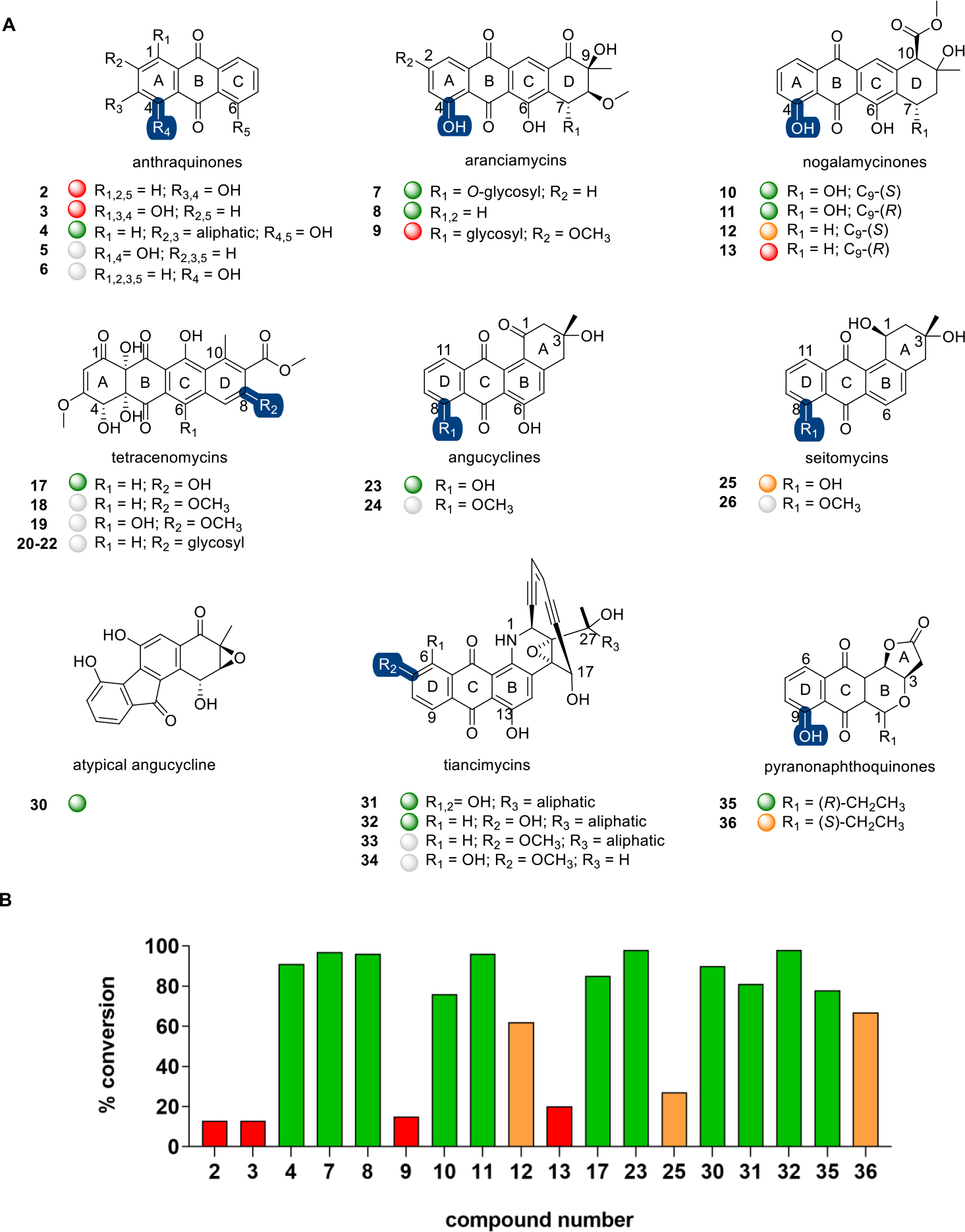

The first set of new non-native substrates identified were comprised of fused aromatic anthracene, tetracene, or benz[a]anthracene scaffolds (Figure 2; Table S2). With the exception of the tetracenomycins and tiancimycins, all members within this series contained the key β-hydroxy quinone signature of the native substrate CAR (1). The simplest among these were the substituted anthraquinones alizarin (2, 13%), purpurin (3, 13%), and 9,10-seco-7-deoxynogalamycinone (4, 91%).26 Anthraquinones represent a structurally and functionally diverse class of pharmacophores in which subtle structural changes can notably alter functional outcomes.27–30 Comparative analysis of the anthraquinone set revealed CAR-like DnrK β-hydroxy regioselectivity in 4. LC-MS could not delineate A ring versus C ring β-hydroxy alkylation in 4 nor β- or γ-hydroxy methylation for 2 or 3 (Figures S24–S26). Intriguingly, no turnover was observed with representative anthraquinones containing only β-hydroxy substitutions such as quinizarin (5) or juglone (6).

Figure 2.

A, Representative anthracene, tetracene, benz[a]anthracene, and related DnrK substrates. Highlighted DnrK regioselectivity (blue), where determined, was based on isolation and structure elucidation [4-O-methoxyarancinamycin (7a)] or coelution with product standards (1a, 18, 24, 26, and 32) or assigned based on the presence of a single aromatic hydroxyl (pyranonapthoquinones). B, The percent conversion to product in end point LC-MS assays (1 mM test agent, 3.2 mM AdoMet, 100 μM DnrK, 37 °C, 16 h). Turnover is categorized in the plot and under each structure as a colored ball as good (≥75%, green), moderate (>25% to <75%, orange), low (≤25%, red), and no turnover (gray).

The CAR-like tetracenes methylated by DnrK included aranciamycin (7, 97%; Figure S1),31 7-deoxyaranciamycin (8, 96%; also known as SM 173B), steffimycin B (9, 15%),32 and various nogalamycinones [nogalavinone (10, 76%), auramycinone (11, 96%), 7-deoxynogalamycinone (12, 62%), and deoxyauramycinone (13, 20%), respectively].26,33 Compared to CAR (1), the aranciamycin D ring has a C8 methoxy and differs slightly in the C7 glycosyl and C9 aliphatic substitutions. DnrK turnover of 7 and the C7-deoxy analogue of its aglycon (8, lacking both C7-OH and its appended 2-O-methyl-l-rhamnose) was quantitative, and the corresponding DnrK aranciamycin product confirmed as 4-O-methoxyarancinamycin (7a) via product isolation and structure elucidation (Figures S2 and S3). While DnrK appeared to tolerate a wide range of D ring structural modifications, the addition of a C2 methoxy substitution led to marked reduction in DnrK turnover. Compared to 8, the structurally related nogalamycinones (10 and 11) and 7-deoxynogalamycinones (12 and 13) lack the D ring C8 methoxy and contain a distinct C10 substitution. In the case of nogalamycinones, the absence or presence of the C7 hydroxy comparatively impacted DnrK turnover with DnrK favoring the C7-hydroxy analogues 10 and 11 over 12 and 13. No DnrK-catalyzed conversion was observed in the presence of prototypical nogalamycins bearing a C1/C2-fused glycoside [compounds 14–16; Figure S4].34

Distinct from the CAR-like tetracenes, tetracenomycins lack the key β-hydroxy quinone signature of the native DnrK substrate. Tetracenomycins are natural products with antibiotic and anticancer activities that inhibit the polypeptide exit tunnel of the bacterial ribosome.35 Facile DnrK-catalyzed turnover of 8-desmethyltetracenomycin C (17, 85%) was observed, the reaction product of which had the same retention time and mass as tetracenomycin C [TCM C, 18; Figure S5].36 This surprising result implicated DnrK as a functional mimic of the TCM 8-O-MT TcmO.9,37,38 In addition, while DnrK-catalyzed reactions with 6-hydroxy-TCM C (19) led to no product, C8-glycosides of 8-desmethyl TCM C (20–22) led to efficient TCM C (18) production in two (20 and 22) of the three cases. This result is consistent with glycoside hydrolysis and concomitant C8-methylation. Incubation of these three glycosides in the absence and presence of DnrK or AdoMet revealed that glycoside hydrolysis was nonenzymatic.

Representative tetracyclic benz[a]anthracene DnrK substrates included naturally occurring angucyclines, a structurally and functionally diverse class of natural products.39 Specifically, rabelomycin (23, 98%)40 and 8-O-desmethylseitomycin (25, 27%) in the presence of DnrK and AdoMet led to 8-O-methylrabelomycin (24) (Figure S6) and seitomycin (26)41 (Figure S7), respectively. Consistent with DnrK angucycline C8 regioselectivity, C8-substituted analogues [e.g., landomycin E (27)42 and himalaquinone G (28)43] were not DnrK substrates (Figure S4). The inability of DnrK to alkylate landomycinone (29) may be due to the planar structure of landomycinone due to an aromatic A ring. DnrK was also able to catalyze methylation of fluostatin C (30), a benzofluorene-containing atypical angucycline that shares the same early biosynthetic pathway with the typical angucyclines.44 While 90% putative monomethylated product of 30 was detected, DnrK regioselectivity was not determined.

Similar to benz[a]anthracenes, enediyne-fused anthraquinones also contain a tetracyclic angular substructure.45,46 As representatives of this natural product class, the tiancimycins (TNMs) are potent anticancer agents that function primarily as DNA-damaging agents.47,48 Interestingly, while representative tiancimycins contain key C6 and/or C13 β-hydroxyquinone signatures, only C7-O-methylation was observed in the presence of DnrK and AdoMet. Specifically, DnrK enabled facile turnover in the presence of TNM C (31, 81%) and efficient conversion of TNM F (32, 98%) to TNM G (33) (Figure S8). Consistent with this, an analogue lacking the requisite C7-OH [TNM A (34)] led to no reaction. This surprising result implicated DnrK as a functional mimic of the TNM 7-O-MT TnmH.49

Many pyranonaphthoquinone (PNQ) natural products also contain an angular tetracyclic framework and a key C9 β-hydroxyquinone signature. Frenolicin B [FB (35)],50 the prototypical pyranonaphthoquinone, has potent antiparasitic and anticancer activities and was recently found to selectively inhibit peroxiredoxins and glutaredoxins.51 Evaluation of a representative set of naturally occurring PNQs52 revealed DnrK-catalyzed C9-O-methylation in a number of cases. This study led to two preliminary DnrK SAR observations. First, the relative A and B ring stereochemistry [e.g., FB (35, 78%) versus epi-FB (36, 67%)] influenced but did not prohibit catalysis. Second, the intact lactone (A ring) appears to be important, as representative analogues with open lactones (i.e., linear free acids; compounds 37–42; Figure S4) failed to turn over.

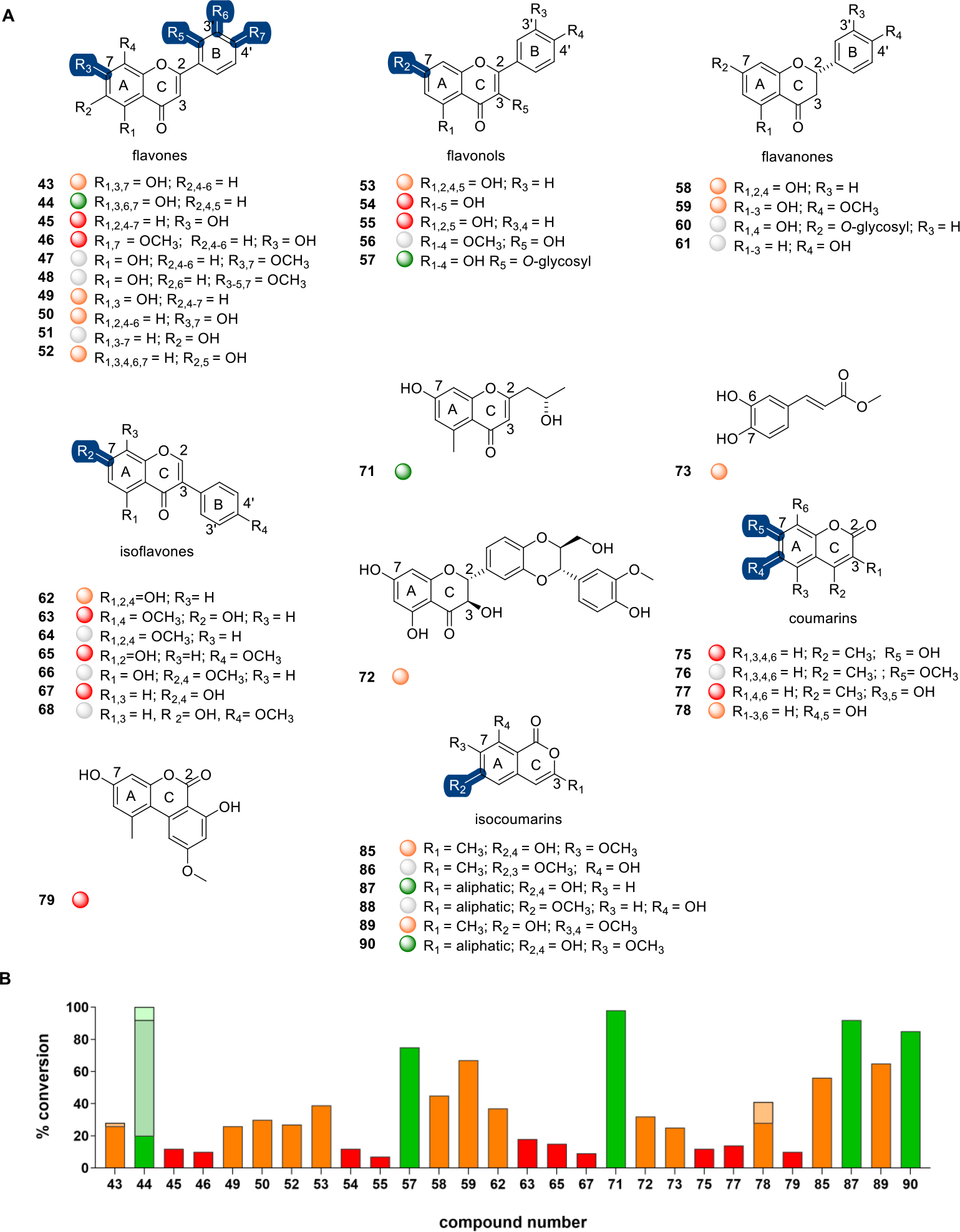

Flavonoids are polyphenolic plant secondary metabolites with anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and cardio/neuro-protective activities.53,54 They are comprised of a fused chromone (1-benzopyran-4-one, benzo-γ-pyrones) core bearing a phenyl at either C2 (flavone) or C3 (isoflavones). Previous computational studies implicated a small set of substituted flavonoids (apigenin, genistein, kaempferol, luteolin, naringenin, and quercetin) as putative DnrK substrates, computationally predicted C7-, C3′- and C4′-OH as the putative methylation sites, and biochemically confirmed DnrK-catalyzed in vitro turnover of apigenin and genistein to their corresponding C7-O-methyl products (Figure 1B).21 To extend this prior study, a wide range of substituted benzo-γ-pyrones including representative flavones, flavonols, flavanones, isoflavones, and related scaffolds (Figure 3) were evaluated. The prior docking study with representative flavones [apigenin (43) and luteolin (44)] predicted a preference of DnrK for C7 and C3′. Consistent with this prediction, representative flavones bearing a single free C7-OH [7-hydroxyflavone (45) and 5,4′-dimethoxy-7-hydroxyflavone (46)] led to corresponding monomethylated products (12% and 10%, respectively). The lack of turnover with flavones bearing a single C5-OH [apigenin dimethyl ether (47) and 5-hydroxy-2′,4′,7,8-tetramethoxyflavone (48)] and the observed DnrK-catalyzed conversion of 5,7-dihydroxy-substituted chrysin (49, 26%) were also consistent with C7 regioselectivity. Likewise, the lack of turnover of flavones bearing a single C5-OH (47 and 48) and the observed DnrK-catalyzed conversion of 5,7,3′,4-tetrahydroxyluteolin (44) to mono-, di-, and trimethyl products (20%, 72%, and 8%, respectively) were consistent with the computational prediction of DnrK C3′-regioselectivity but, in contrast to the computational model, also implicated DnrK-catalyzed C4′-O-methylation. As further support for DnrK flavone C4′-regioselectivity, only monomethylation was observed in the context of 7,4′-dihydroxyflavone (50, 30%), while the 5,7,4′-trihydroxy-substituted 43 led to both a monomethylated product (26%)21 and a 7,4′-di-O-methoxy product (47, 2%; Figure S9). Also distinct from the prior computational predictions, comparison of 6-hydroxy-substituted (51, no turnover) to 6,2′-dihydroxy-substituted (52, 27%) substrates suggested DnrK as capable of flavone C2′-O-methylation.

Figure 3.

A, Representative flavones, flavonols, flavanones, isoflavones, coumarins, and related DnrK substrates. Highlighted DnrK regioselectivity (blue), where determined, was based on coelution with product standards (47, 64, 66, 68, 76, 86, and 88) or assigned based on the presence of a single aromatic hydroxyl (45, 46, and 89). B, The percent conversion to product in end-point LC-MS assays (1 mM test agent, 3.2 mM AdoMet, 100 μM DnrK, 37 °C, 16 h). Turnover is categorized in the plot and under each structure as a colored ball as good (≥75%, green), moderate (>25% to <75%, orange), low (≤25%, red), and no turnover (gray). Percent di- and/or trimethylation for compounds 43, 44, and 78 are represented as lighter shades of each represented color.

In vitro studies with a representative set of flavonols (3-hydroxyflavones) were consistent with a prior docking study that predicted a preference of DnrK for C7 of kaempferol (53) and quercetin (54).21 Specifically, monomethylation in the context of kaempferol (53, 39%), quercetin (54, 12%), and galangin (55, 7%) was observed, while a model flavonol bearing a single C3-OH [quercetin 5,7,3′,4′-tetramethyl ether (56)] lacked turnover. Surprisingly, DnrK was also able to accommodate additional steric bulk at C3, as exemplified by the turnover of the 3-α-l-rhamnoside-substituted quercitrin (57, 75%).

A C7 preference in the context of representative flavanones [2(R)- and 2-(S)-naringenin] was also implicated via docking.21 Consistent with this, representative flavanones with a free C7-OH [2(S)-naringenin (58, 45%); 2(S)-hesperetin (59, 67%)] led to monomethylated products, while related flavanones lacking a free C7-OH [2(S)-naringenin 7-β-d-glucoside (60) or 4′-hydroxyflavanone (61)] failed to turn over in the presence of DnrK.

Docking studies with the representative isoflavone genistein (62) projected a preference of DnrK for C7 and C4′.21 Consistent with C7-O-methylation, DnrK catalyzed the conversion of 5,4′-dimethoxy-7-hydroxyisoflavone (63) to 5,7,4′-trimethoxyisoflavone (64, 18%; Figure S10), the conversion of biochanin A (65) to the corresponding 7-methoxy biochanin A (66, 15%; Figure S11), and the production of 7-methoxygenistein from genistein (62, 37%).21 Similarly, for models lacking a C5-OH, a shift from C7 regioselectivity to C4′-O-methylation was observed, as exemplified by the DnrK-catalyzed conversion of daidzein (67) to formononetin (68, 9%; Figure S12). The addition of steric bulk at C8 [puerarin (69)] or C6 and C8 [pomiferin (70)] prohibited turnover (Figure S4).

DnrK also catalyzed methylation of three other flavonoid-related natural products including the bacterial metabolite 5-carbomethoxymethyl-2-heptyl-7-hydroxychrome (71),55 the plant anticancer/antiviral metabolite silybin B (72),56 and the phenylpropanoid-derived plant metabolite methylcaffeate (73).57 While 71 and 72 each contain a free C7-OH and led to monomethylated products (98% and 32%, respectively), DnrK regioselectivity was not determined. Comparison of monomethylation of 3,4-dihydroxy-substituded methyl caffeate (73, 25%) with 4-hydroxycinnamamide (74, no turnover; Figure S4) implicated DnrK-catalyzed phenylpropanoid C-6-O-methylation to mirror that observed with representative coumarins.

Coumarins are another major class of phenylpropanoid comprised of a fused chromone (1-benzopyran-2-one, benzo-α-pyrones) core (Figure 3). Like flavonoids, coumarins invoke diverse functions including anticoagulant, anticancer, antioxidant, antiviral, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-neurodegenerative activities.58,59 In addition, coumarins are also commonly used fluorophores.60 DnrK catalyzed 7-O-methylation of the prototypical coumarin 4-methylumbelliferone [4-MeUmb (75, 12%)], the product for which co-eluted with the 7-O-methoxy commercial standard [7-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin (76)] (Figure S13). The parent (75) is fluorescent under slightly basic conditions, the fluorescence of which can be abolished via C7-OH modification (e.g., alkylation or glycosylation).61 DnrK catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) with CAR (1) was nearly 3 orders of magnitude greater (500-fold) than that with 75 (kcat = 0.036 ± 0.001 min−1, Km = 1160 ± 170 μM under saturating [AdoMet]; Table S1). DnrK-catalyzed turnover was also observed with 5,7-dihydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (77, 14%), 6,7-dihydroxycoumarin (78, 44%), and the benzo(c)coumarin 9-methoxyalternariol (79, 10%). Indicative of both C6 and C7 regioselectivity, the product distribution of 78 included two chromatographically distinct monomethylated species (28% and 13%) and a dimethylated product as a minor product (3%). Increasing coumarin steric bulk [orlandin (80), 4,5,7-trihydroxy-3-phenylcoumarin (81), or representative chrysomycins (82–84); Figure S4] prohibited alkylation.

The structurally similar polyketide-derived isocoumarins are biosynthetically distinct from phenylpropanoids but, like their coumarin counterparts, display diverse bioactivities.62 DnrK isocoumarin C6-regioselectivity was established via the observed conversion of 6,8-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-3-methylisocoumarin (85) to the corresponding C6-methoxy product 8-hydroxy-6,7-dimethoxy-3-methylisocoumarin (86, 56%; Figure S14) and orthosporin (87) to the corresponding C6-methoxy product diaporthin (88, 92%; Figure S15). Two additional isocoumarins bearing a free C6-OH [6-hydroxy-7,8-dimethoxy-3-methylisocoumarin (89, 65%); 6,8-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-3-hydroxymethylisocoumarin (90, 85%)] also led to DnrK-catalyzed monomethylated products.

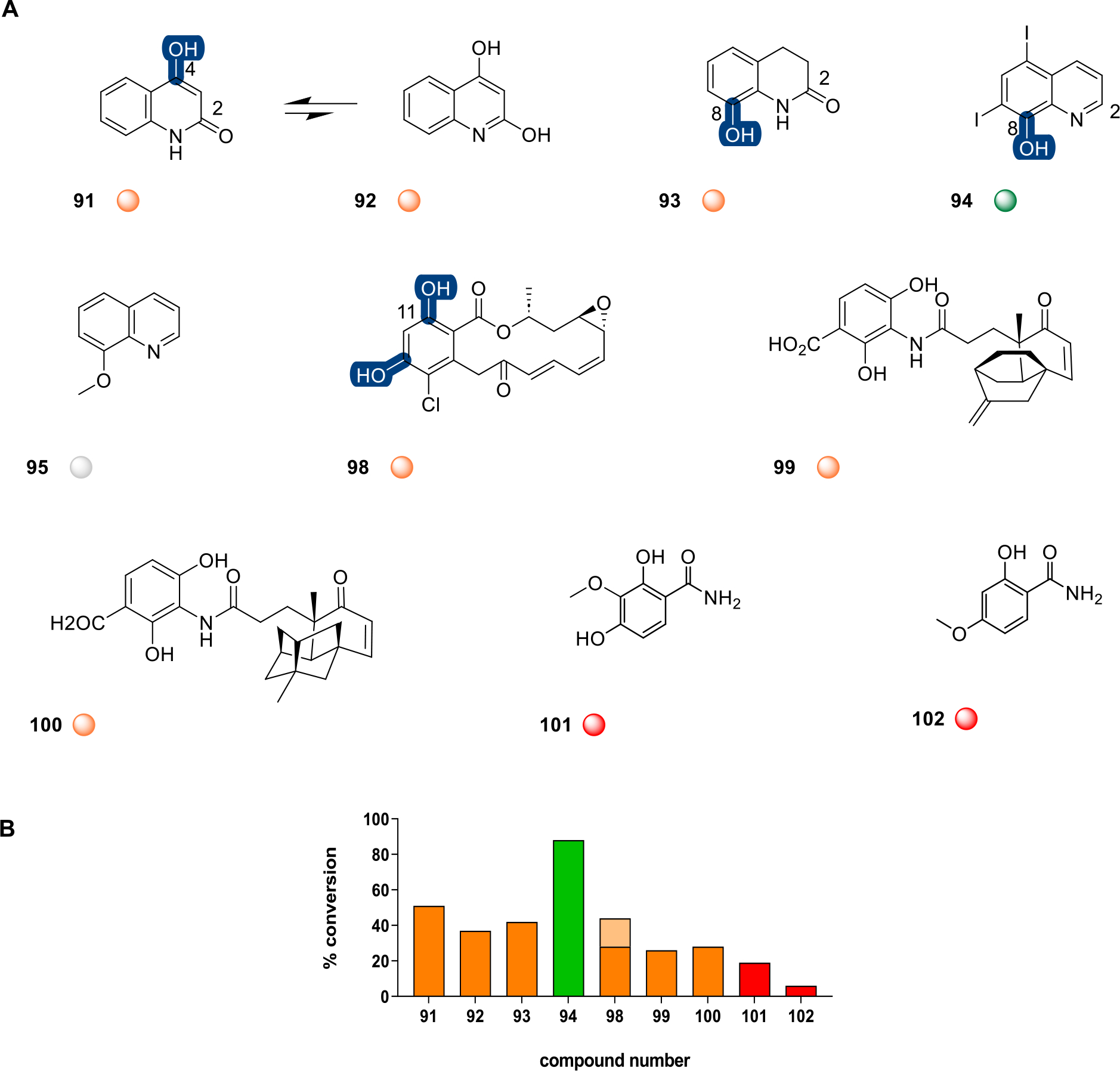

Structurally related to coumarins, 2-quinolones are derived from anthranilic acid (Figure 4).63 Both 4-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one (91, 51%) and its tautomer 2,4-dihydroxyquinoline (92, 37%) led to the same DnrK-catalyzed product, implicating a common tautomer as the substrate (Figure S16).64 DnrK was also able to catalyze putative C8-OH methylation of the related 8-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2-quinolinone (93, 42%) and iodoquinol (94, 88%). By comparison, DnrK had no effect on 8-methoxyquinoline (95; Figure S4) (consistent with C8-OH selectivity) or simple related scaffolds lacking the heterocyclic nitrogen such as naphthols (96 and 97; Figure S4). DnrK was also able to alkylate diverse fused benzoic acid containing natural products including the Hsp90 inhibitor radicicol (98, 44%),65 the fatty acid synthase inhibitors platencin and platensimycin (99, 26% and 100, 28%, respectively],66–68 and structurally related pyramidamycins A and B (101, 19% and 102, 6%, respectively)69 (Figure 4). Of particular note, DnrK was able to alkylate both the C9-OH and the C11 β-OH of radicicol, as evidenced by the production of two chromatographically distinct monomethyl species (23% and 5%) and a third dimethylated product (16%). While platencin (99), platensimycin (100), and the pyramidamycins (101 and 102) also share a common phenolic benzoic acid-type core and each led to a single monomethyl product, regioselectivity in this series was not determined.

Figure 4.

A, Representative 2-quinolones, fused benzoic acid containing natural products, and related DnrK substrates. Highlighted DnrK regioselectivity (blue), where determined, was based on the presence of a single aromatic hydroxyl (91, 93, and 94) and detection of monomethylated product or two aromatic hydroxyls (98) and detection of mono- and dimethylated products. B, The percent conversion to product in end-point LC-MS assays (1 mM test agent, 3.2 mM AdoMet, 100 μM DnrK, 37 °C, 16 h). Turnover is categorized in the plot and under each structure as a colored ball as good (≥75%, green), moderate (>25% to >75%, orange), low (≤25%, red), and no turnover (gray). Percent dimethylation for compound 98 is represented as lighter shades of orange.

DnrK Structure Elucidation and Relationships to Other MTs with Similar Functions.

To better understand acceptor binding, the crystal structure of DnrK with the fluorescent hydroxycoumarin 4-MeUmb (75) was determined to be 1.84 Å resolution in space group C2. The determined structure is quite similar to the other solved DnrK complexes, with pairwise Cα rmsd between all protomers in 1TW2, 1TW3, 5EEG, 5EEH, and 5JR3 ranging between 0.2 and 1.3 Å. The electron density clearly displays the bound 4-MeUmb (75) acceptor and reveals the conversion of AdoMet added to the crystallization drops to AdoHcy (Figure S18). The hydroxy of the acceptor is positioned to accept a methyl from the bound AdoMet surrogate (AdoHyc) with a water positioned between the AdoHcy sulfur and the hydroxy of 4-MeUmb (75) (Figure S19). Since DnrK was validated as a functional mimic of TnmH and TcmO, we also compared their structures to that of DnrK. The comparative structures share a common methyltransferase fold and are quite similar to Cα rmsd ranging from 1.8 to 2.5 Å for protomers of DnrK to TnmH (39% sequence identity) and 3.6–4.3 Å for DnrK to the AlphaFold-predicted structure of TcmO (24% sequence identity) (Figure S20 and Figure S21).

The binding tunnel of DnrK containing AdoHcy and the 4-MeUmb (75) is open on three sides (near the nucleotide of AdoHcy, along the edge of 4-MeUmb (75) and a smaller opening above it) (Figure S22). The large open area around the acceptor binding region allows the pocket to accommodate a number of different compounds, as illustrated by the structures of DnrK in complex with AdoHcy and 4-methoxy-ϵ-rhodomycin T (M-ϵ-T) (PDB ids 1TW2 and 1TW3), the complex with a tetrazole analogue of AdoHcy (5EEG), and the complex with CINP (5EEH), all of which reveal a large open substrate tunnel. In fact, in the structure with AdoHcy and CINP, five CINP molecules in addition to the ClNP positioned for methyl transfer bound within the tunnel were observed.22 Compared to the structure of TnmH and the predicted structure of TcmO, the DnrK acceptor binding tunnel is more open. Specifically, in the region between helices 11 and 12 of DnrK, residues 161–167 interrupt these two helices and are flipped out of the binding pocket. In contrast, the equivalent region of TnmH (and for the predicted TcmO structure) has the two helices abutting with a kink at the end of helix 11 that changes the helix direction for helix 12. This positions TnmH R153 and TcmO N154 (the residues corresponding to D163 in DnrK) in proximity to the carboxylate of AdoMet/AdoHcy, restricting the substrate tunnel (Figure S22B and S22C).

Impact of Methylation on the Bioactivity of Representative Model Compounds.

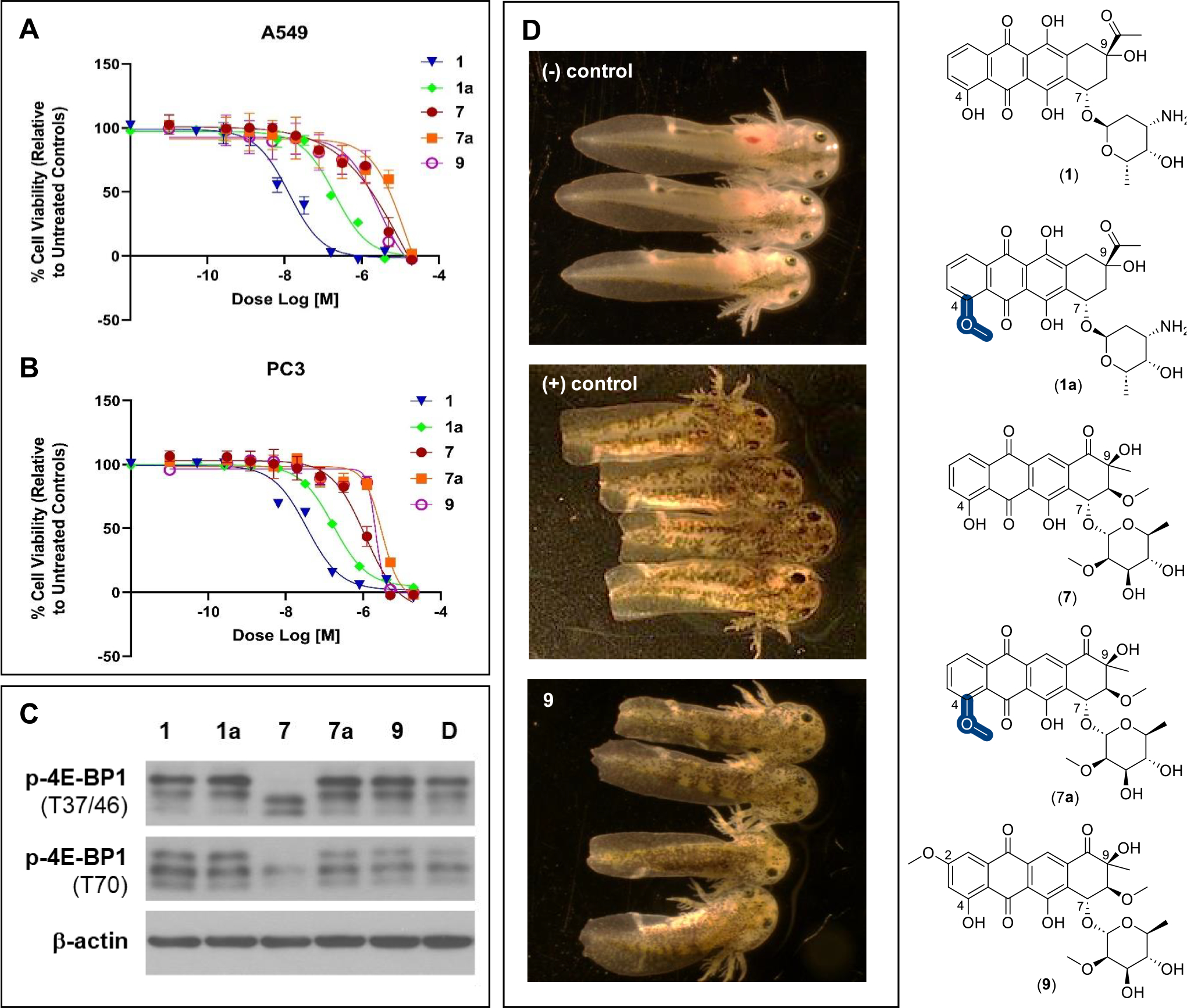

A small exemplary set of compounds was selected to interrogate in three complementary assays (cancer cell line cytotoxicity, 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, and axolotl tail regeneration) to enable a preliminary assessment of biocatalytic O-methylation on metabolite function. The parental scaffolds included in this set were CAR (1) and aranciamycin (7), metabolites that structurally diverge from one another by their C7 glycosyl substituents as well as divergent substitution and stereochemistry at C9. Also included were the corresponding C4-O-methylated DnrK products of CAR and aranciamycin (DNR/1a and 7a, respectively) and steffimycin B (9),32 a naturally occurring C2-O-methoxy analogue of 7. While the des-methyl parent (1) was 30–200-fold more cytotoxic than 7 in the two representative cancer cell lines tested, C4-O-methylation of both 1 and 7 led to reductions in cytotoxicity of 7–15-fold for 1 and 4–7-fold for 7 (Figure 5A and 5B). The corresponding cytotoxicity of 9 reflects that of 7/7a, consistent with other recent (9) cancer cell line cytotoxicity studies70 and the reported notably reduced affinity of 9 for DNA compared to that of DNR or DXR.71

Figure 5.

A, Dose–response of compounds CAR (1), DNR (1a), aranciamycin (7), 4-O-methoxyaranciamycin (7a), and steffimycin B (9) against A549 (non-small-cell lung) human cancer cell line (72 h). B, Dose–response of mentioned compounds against the PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell line (72 h). A549: IC50 for the compounds (1, 13.09 nM; 1a, 199.0 nM; 7, 2.7 μM; 7a, 13.8 μM; 9, 2.8 μM). PC3: IC50 for the compounds (1, 34.98 nM; 1a, 170.1 nM; 7, 1.1 μM; 7a, 4.3 μM; 9, 3.1 μM). C, HCT116 cells were treated with 2 μM of test compounds or DMSO (negative control) for 6 h followed by Western blot analysis for the indicated proteins. D, The impact of 10 μM steffimycin B (9) on axolotl embryo tail regeneration at 7 dpa compared to vehicle (DMSO, negative control) and the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin (positive control). Compounds 1, 1a, 7, and 7a led to no inhibition of tail regeneration under identical conditions.

Among the multiple mechanisms put forth as drivers of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and downstream ROS-mediated processes are a predominate contributing factor.1 The phosphorylation status of the cap-dependent translational repressor 4E-BP1 is a correlative sensor for ROS-mediated cytotoxicity in cancer cell lines.51 As highlighted in Figure 5C, only 7 invokes a shift in 4E-BP1 phosphorylation indicative of ROS induction. Taken together with the cytotoxicity studies highlighted above, these data suggest minimal ROS contribution to cytotoxicity among the structurally related high-potency (1 and 1a) and most low-potency (7a and 9) analogues. In contrast, these data reveal the absence or presence of a C4-O-methoxy group in the low-potency comparators (7 and 7a) to contribute to a putative mechanistic shift that ultimately alters cellular ROS status.

Prior studies in the regenerative salamander model (the Mexican axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum) revealed tail regeneration to require a rapid escalation of ROS which occurs as a rapid response to axolotl tail amputation.72 While all members of the test set were well-tolerated in a corresponding axolotl embryo tail regeneration assay,43,73 only 9 inhibited tail regeneration (Figures 5D and S17). This result highlights subtle anthracycline structural modifications to translate to dramatic shifts in regenerative outcomes where the divergence from the 4E-BP 1p/ROS study described above may result, in part, from yet to be determined factors that contribute to differences in uptake and/or in vivo exposure.

CONCLUSIONS

Methyltransferases are ubiquitous biocatalysts, and, while it is well-established that many methyltransferases can use non-native AdoMet donors, stringent fidelity to the corresponding acceptor is typical among methyltransferases.74 Within this context, the current study highlights DnrK as unique among conventional methyltransferases by virtue of a demonstrated broad acceptor tolerance. The mechanistic and/or structural basis of DnrK’s perceived atypical permissivity remains unclear. As described in the current study, DnrK’s active-site features and general catalytic parameters are similar to those of previously studied aromatic O-methyltransferases. Yet, the current and previously reported DnrK ligand-bound structures do reinforce the evidence of DnrK’s productive flexibility to diverse ligands and ligand orientations.18,22 Consistent with this, recent chimeric engineering studies also implicate the DnrK scaffold as a uniquely malleable biocatalytic template able to accommodate diverse chemistries.20,75 While speculative, the potential of DnrK to productively orient diverse acceptors with the requisite activated alkyl donor (AdoMet) may suggest increased attention be given to key acceptor properties (e.g., pKa/nucleophilicity) in predicting putative non-native substrates. Within this context, the unique acceptor permissivity of DnrK may offer the potential for a more systematic study to probe the contribution of such specific acceptor molecular features in catalysis. In addition, the demonstrated uniquely permissive biocatalytic capabilities of DnrK also open the door for future synthetic biology and/or synthetic applications.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Experimental Procedures.

Most compounds for substrate scope studies were derived from the Spectrum Collection (Microsource Discovery Systems, Inc., Gaylordsville, CT, USA) or the University of Kentucky Center for Pharmaceutical Research and Innovation Natural Products Repository (Lexington, KY, USA). Tiancimycins, platensimycin, and platencin were isolated as previously described.47,67,68,76 Silybin B was provided by Professor Tom Prisinzano (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA). Carminomycin (CAR, 1) was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells and S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet, 32 mM solution in 10% EtOH–5 mM H2SO4) were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

High-resolution electrospray ionization (HRESI) mass spectra were recorded on an AB SCIEX Triple TOF 5600 system (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). HPLC-UV/MS analyses were accomplished with an Agilent Infinity Lab LC/MSD mass spectrometer (MS model G6125B; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an Agilent 1260 Infinity II Series Quaternary LC system and a Phenomenex NX-C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) [method A: solvent A: H2O–0.1% formic acid, solvent B: CH3CN; flow rate: 0.5 mL min−1; 0–30 min, 5–100% B (linear gradient); 30–35 min, 100% B; 35–36 min, 100–5% B; 36–40 min, 5% B]. Semipreparative HPLC was accomplished using a Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA) C18 column (10 × 250 mm, 5 μm) on a Varian (Palo Alto, CA, USA) ProStar model 210 equipped with a photodiode diode array detector and a gradient elution profile [method B: solvent A: H2O–0.025% TFA; solvent B: CH3CN; flow rate: 5.0 mL min−1; 0–3 min, 10% B; 3–35 min, 10–100% B; 35–40 min, 100% B; 40–43 min, 100–10% B; 43–45 min, 10% B]. All NMR data were recorded at 400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C with Varian Inova NMR spectrometers (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), where δ-values were referenced to respective solvent signals [CDCl3, δH 7.24 ppm, δC 77.23 ppm]. A549 and PC3 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). All other biochemicals and chemicals were reagent grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise noted.

N-His6-DnrK and N-His6-SAHH Heterologous Production and Purification.

N-His6-DnrK and N-His6-S-adenosyl-l-homocysteinease (SAHH) were produced and purified as previously described for all studies herein.22,77

DnrK in Vitro Assay.

Assays followed the previously reported protocols with minor changes.22,78–80 Specifically, for substrate specificity studies, DnrK reactions were conducted in a volume of 30 μL of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, containing 3.2 mM AdoMet, 1 mM non-native acceptor, and 100 and 40 μM DnrK and SAHH. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h and subsequently quenched with an equal volume of MeOH followed by centrifugation (13000g, 15 min) to remove the precipitated protein. Product formation was assessed by HPLC (method A) and based on the integration of species at 254, 280, or 320 nm as previously reported.22 Corresponding control reactions lacking DnrK or AdoMet led to no product. As commercially sourced AdoMet stereochemistry and stability is variable,22,77,81 turnover in a model reaction (conversion of 1 to 1a) with commercially sourced AdoMet (NEB) was compared to AdoMet generated via methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT)-catalyzed conversion (which affords a single AdoMet stereoisomer from ATP and l-methionine) and found to be identical. Thus, commercially sourced AdoMet was used for all assays described. Inclusion of SAHH (an enzyme that degrades the co-product SAH/AdoHcy) in these reactions improved turnover by driving reaction equilibrium toward desired product formation, and newer cofactor regeneration systems are anticipated to afford similar advantages.82

DnrK Kinetics.

DnrK kinetic parameters were determined for both CAR (1) and 4-MeUmb (75) acceptors (Table S1) using assay conditions described above. Kinetic studies were conducted in triplicate using 10 μM DnrK under saturating AdoMet (1.6 mM) and variable concentrations of 1 [15 μM to 500 mM] or 75 [150 μM to 10 mM]. Kinetic parameters were derived from Michaelis–Menten reciprocal plots (Figure S23).

DnrK Crystallization and Structure Elucidation.

The co-crystallization of DnrK with AdoHcy and 4-MeUmb (75) was achieved by mixing 0.2 μL of protein sample solution (20 mg/mL DnrK, 2.5 mM AdoMet, 7.5 mM (75), and 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0) with 0.2 μL of reservoir solution (1.26 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.0, and 0.2 M lithium sulfate) at 20 °C using the hanging drop method. The crystals were then soaked and cryoprotected with 80% reservoir solution, 15% glycerol, and 3 mM 75 and then flash cooled in liquid nitrogen for data collection.

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory) on Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT) beamline 21-ID-F. Data sets were indexed, integrated, and scaled using XDS.83 The structure was phased using the isomorphous DnrK structure in complex with AdoHcy and 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol, PDB id 5EEH,22 as a starting model. The structural model was completed after several rounds of manual model building with COOT84 and refinement with phenix.refine.85 The structure was visualized and analyzed using a collaborative 3D graphics system.86 The structural biology software applications used in this project were compiled and configured by SBGrid.87 Data processing and refinement statistics are shown in Table S3, and the structure was deposited in the worldwide Protein Data Bank with PDB id 5JR3.

Structure Prediction of TcmO.

The TcmO homodimer was predicted using AlphaFold-Multimer88,89 with a multiple sequence alignment generated by MMSeqs290 in the ColabFold91 notebook both with and without templates. The rank 1 model from the run without templates had the highest median pLDDT (0.97) and the lowest median PAE (3.8 Å) score. The AMBER relaxed92 model from this run was quite similar to the other models produced (Cα rmsd 0.1–0.4 Å for the homodimers) and was selected for further analysis. Plots of the multiple sequence alignment coverage and local and global predicted accuracy metrics are shown in Figure S20.

4-O-Methoxyaranciamycin Production and Structure Elucidation.

In a 15 mL sterile conical tube, a total volume of 5 mL of DnrK reaction including 5.4 mg (10 mM DMSO stock) of previously isolated aranciamycin (7), 3.2 mM AdoMet, and 100 and 40 μM affinity-purified DnrK and SAHH in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, was conducted under standard assay conditions and used for preparative DnrK-catalyzed methylation. Semipreparative HPLC purification of the crude reaction (method B, Figure S2) afforded compound 7a in pure form as an orange solid (3.0 mg, 55% yield). The molecular formula of 7a was established as C28H30O12 based on (+)- and (−)-HRESIMS [m/z 559.1813 [M + H]+ (calcd 559.1910 for C28H31O12); m/z 557.1649 [M – H]− (calcd 557.1664 for C28H29O12)] and the corresponding Δm/z = 14 compared to that for 7, consistent with an additional methyl group. Consistent with this, the 13C/1H/HSQC NMR of 7a (Table S4) highlighted a missing 4-OH (δH 11.82, 1H, s) and an additional methoxy group (δH 4.09, 3H, s; δC 57.0). The connection of the OCH3 at the 4-position in compound 7a was established based on the observed critical HMBC correlation from the singlet methoxy (δH 4.09; 4-OCH3) to C-4 (δC 161.4). All other 2D NMR (1H,1H-COSY and HMBC) correlations were in full agreement with structure 7a (Figure S3). Thus, compound 7a was designated as 4-O-methoxyarancinamycin.

Cancer Cell Line Viability Assay.

Mammalian cell line cytotoxicity [A549 (non-small-cell lung) and PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell lines] assays (Figure 5A and Figure 5B) were accomplished in triplicate following our previously reported protocols.42,52 Actinomycin D and H2O2 were used as positive controls.

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described.43,51,72 Specifically, after treatment with test agent, HCT116 cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of protein were subsequently resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, immunoblotted with specific primary and secondary antibodies, and detected using chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) (Figure 5C). Antibodies for phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) (#2855) and phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr70) (#13396) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). β-Actin antibody (A5441; 1:10 000) was from Sigma-Aldrich.

Axolotl Embryo Tail Regeneration Assay.

The axolotl embryo tail regeneration assay was conducted following our previously reported protocols.43,72,73 Briefly, stage 42 embryos were manually hatched, administered benzocaine anesthesia (0.2 g in 10 mL of EtOH/L water), and photographed (Figures 5D and S17). Embryos were subsequently administered 2 mm tail amputations and then reared (in the absence or presence of test agent) at 18–19 °C in 12-well microtiter plates containing 2.0 mL of artificial pond water (43.25 g NaCl, 0.625 g KCl, 1.25 g MgSO4, 2.5 g NaHCO3, and 1.25 g CaCl per 50 L charcoal filtered municipal water). The solutions were changed on days 3 and 5 postamputation (dpa), and experiments were terminated on 7 dpa. Images of anesthetized embryos at 0, 3, 5, and 7 dpa were captured using an Olympus microscope with a 0.5× objective lens and DP400 camera. All chemicals were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to 0.1% final DMSO concentration. Axolotls (RRID:AGSC_100E) were obtained from the Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center (RRID:SCR_006372). Vehicle (DMSO) was used as the negative control, and the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin was used as a positive control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R37 AI052218 (J.S.T.), R01 CA203257 (J.S.T., Q.-B.S.), USDA-NIFA-CBGP, Grant No. 2023–38821-39584 (K.A.S. and J.S.T.), and GM 134954 (B.S.), the NSF, BioXFEL Science and Technology Center grant 1231306 (G.N.P.), NIH postdoctoral fellowships F32 GM133114 (A.D.S.) and F32 GM128345 (C.N.T.), the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000117 and UL1 TR001998). We also thank the College of Pharmacy PharmNMR Center for analytical support. NMR data were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE NEO 400 MHz NMR spectrometer or a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 MHz high-performance digital NMR spectrometer [supported, in part, by NIH grants P20 GM130456 (J.S.T.) and S10 OD28690]. This research also used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-2Corridor (Grant 085P1000817). GM/CA-CAT at the APS has been funded by the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006, P30GM138396) The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of NIH or NSF.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AdoMet

S-adenosylmethionine

- AdoHcy

S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine

- PAE

predicted aligned error

- pLDDT

predicted local distance difference test score

- SAHH

S-adenosyl-l-homocysteinease

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

SI Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.3c00947.

Supplementary figures and tables, analytical data, and citations (PDF)

Contributor Information

Elnaz Jalali, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States; Present Address: Novartis Gene Therapy, San Diego, California 92121, United States..

Fengbin Wang, Department of Biosciences, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77030, United States; Present Address: University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama 35294, United States.

Brooke R. Overbay, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States; Present Address: Procter & Gamble, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202, United States.

Mitchell D. Miller, Department of Biosciences, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77030, United States

Khaled A. Shaaban, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Center for Pharmaceutical Research and Innovation, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States

Larissa V. Ponomareva, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Center for Pharmaceutical Research and Innovation, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States

Qing Ye, Markey Cancer Center, Department of Pharmacology and Nutritional Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States.

Hoda Saghaeiannejad-Esfahani, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States.

Minakshi Bhardwaj, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States; Present Address: Celanese, Florence, Kentucky 41042, United States..

Andrew D. Steele, Department of Chemistry, The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology, University of Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, United States

Christiana N. Teijaro, Department of Chemistry, The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology, University of Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, United States; Present Address: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, New Jersey 08543, United States.

Ben Shen, Department of Chemistry, Department of Molecular Medicine, Natural Products Discovery Center, and Skaggs Graduate School of Chemical and Biological Sciences, The Herbert Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology, University of Florida, Jupiter, Florida 33458, United States; Present Address: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, New Jersey 08543, United States..

Steven G. Van Lanen, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Center for Pharmaceutical Research and Innovation, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States

Qing-Bai She, Markey Cancer Center, Department of Pharmacology and Nutritional Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States.

S. Randal Voss, Department of Neuroscience, Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center, and Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States.

George N. Phillips, Jr., Department of Biosciences and Department of Chemistry, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77030, United States

Jon S. Thorson, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Center for Pharmaceutical Research and Innovation, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States

Data Availability Statement

This article contains Supporting Information. The structural coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as PDBID 5JR3.

■ REFERENCES

- (1).Van der Zanden S; Qiao X; Neefjes J FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6095–6111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bristow MR; Thompson PD; Martin RP; Mason JW; Billingham ME; Harrison DC Am. J. Med. 1978, 65, 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McGowan JV; Chung R; Maulik A; Piotrowska I; Walker JM; Yellon DM Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2017, 31, 63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Camerino B; Palamidessi G Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1960, 90, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Di Marco A; Cassinelli G; Arcamone F Cancer Treat Rep. 1981, 65, 3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Arcamone F; Cassinelli G; Fantini G; Grein A; Orezzi P; Pol C; Spalla C Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1969, 11, 1101–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hulst MB; Grocholski T; Neefjes JJ; van Wezel GP; Metsä-Ketelä M Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 814–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Binaschi M; Bigioni M; Cipollone A; Rossi C; Goso C; Maggi CA; Capranico G; Animati F Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents. 2001, 1, 113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hutchinson CR Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2525–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hutchinson CR; Colombo AL J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 23, 647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dickens ML; Priestley ND; Strohl WR J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 2641–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Connors NC; Strohl WR J. Gen. Microbiol. 1993, 139, 1353–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dickens ML; Ye J; Strohl WR J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Madduri K; Torti F; Colombo AL; Hutchinson CR J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 3900–3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Madduri K; Hutchinson CR J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 3879–3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Miyamoto Y; Ohta S; Johdo O; Nagamatsu Y; Yoshimoto A J.. Antibiot. Tokyo. 2000, 53, 828–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Scotti C; Hutchinson CR Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1995, 48, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Jansson A; Koskiniemi H; Mäntsälä P; Niemi J; Schneider GJ Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41149–41156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fewer DP; Metsä-Ketelä M FEBS J. 2020, 287, 1429–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Grocholski T; Dinis P; Niiranen L; Niemi J; Metsä-Ketelä M Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 9866–9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kim NY; Kim JH; Lee YH; Lee EJ; Kim J; Lim Y; Chong YH; Ahn JH J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 1991–1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Huber TD; Wang F; Singh S; Johnson BR; Zhang J; Sunkara M; Van Lanen SG; Morris AJ; Phillips GN Jr; Thorson JS ACS. Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 2484–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zheng J; Wei W; Lan X; Zhang Y; Wang Z Anal. Biochem. 2018, 549, 26–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Williams GJ; Thorson JS Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Jalali E; Thorson JS Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 69, 290–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wang R; Nguyen J; Hecht J; Schwartz N; Brown KV; Ponomareva LV; Niemczura M; van Dissel D; van Wezel GP; Thorson JS; Metsä-Ketelä M; Shaaban KA; Nybo SE ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 4193–4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Malik EM; Müller CE Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 705–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Siddamurthi S; Gutti G; Jana S; Kumar A; Singh SK Future Med. Chem. 2020, 12, 1037–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Campora M; Francesconi V; Schenone S; Tasso B; Tonelli M Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Singh J; Hussain Y; Luqman S; Meena A Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2418–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Cheema MT; Ponomareva LV; Liu T; Voss SR; Thorson JS; Shaaban KA; Sajid I Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 3044–3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Brodasky TF; Reusser F J. Antibiot. Tokyo. 1974, 27, 809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Torkkell S; Kunnari T; Palmu K; Hakala J; Mäntsälä P; Ylihonko K Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 396–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Siitonen V; Nji Wandi B; Törmänen AP; Metsä-Ketelä M ACS. Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 2433–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Osterman IA; Wieland M; Maviza TP; Lashkevich KA; Lukianov DA; Komarova ES; Zakalyukina YV; Buschauer R; Shiriaev DI; Leyn SA; Zlamal JE; et al. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Egert E; Noltemeyer M; Siebers J; Rohr J; Zeeck A J. Antibiot Tokyo. 1992, 45, 1190–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Decker H; Summers RG; Hutchinson CR J. Antibiot Tokyo. 1994, 47, 54–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Nguyen JT; Riebschleger KK; Brown KV; Gorgijevska NM; Nybo SE Biotechnol. J. 2022, 17, No. e2100371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kharel MK; Pahari P; Shepherd MD; Tibrewal N; Nybo SE; Shaaban KA; Rohr J Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 264–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Liu WC; Parker L; Slusarchyk S; Greenwood GL; Graham SF; Meyers E J. Antibiot Tokyo. 1970, 23, 437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Abdelfattah M; Maskey RP; Asolkar RN; Gruen-Wollny I; Laatsch H J. Antibiot Tokyo. 2003, 56, 539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Shaaban KA; Srinivasan S; Kumar R; Damodaran C; Rohr J J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Zhang Y; Cheema MT; Ponomareva LV; Ye Q; Liu T; Sajid I; Rohr J; She QB; Voss SR; Thorson JS; Shaaban KA J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 1930–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Yang C; Huang C; Zhang W; Zhu Y; Zhang C Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5324–5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Yan X Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 703–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Galm U; Hager MH; Van Lanen SG; Ju J; Thorson JS; Shen B Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 739–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Yan X; Chen JJ; Adhikari A; Teijaro CN; Ge H; Crnovcic I; Chang CY; Annaval T; Yang D; Rader C; Shen B Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 5918–5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Zhuang Z; Jiang C; Zhang F; Huang R; Yi L; Huang Y; Yan X; Duan Y; Zhu X Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 1304–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Adhikari A; Teijaro CN; Yan X; Chang CY; Gui C; Liu YC; Crnovcic I; Yang D; Annaval T; Rader C; Shen B J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8432–8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Iwai Y; Kora A; Takahashi Y; Hayashi T; Awaya J; Masuma R; Oiwa R; Omura S J. Antibiot Tokyo. 1978, 31, 959–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Ye Q; Zhang Y; Cao Y; Wang X; Guo Y; Chen J; Horn J; Ponomareva LV; Chaiswing L; Shaaban KA; Wei Q; Anderson BD; St Clair DK; Zhu H; Leggas M; Thorson JS; She QB Cell. Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 366–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Wang X; Shaaban KA; Elshahawi SI; Ponomareva LV; Sunkara M; Zhang Y; Copley GC; Hower JC; Morris AJ; Kharel MK; Thorson JS J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1441–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mutha RE; Tatiya AU; Surana SJ Future. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Alzaabi MM; Hamdy R; Ashmawy NS; Hamoda AM; Alkhayat F; Khademi NN; Al Joud SMA; El-Keblawy AA; Soliman SSM Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 291–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Xu J; Kjer J; Sendker J; Wray V; Guan H; Edrada R; Lin W; Wu J; Proksch P J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 662–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Srivastava R; Tripathi S; Unni S; Hussain A; Haque S; Dasgupta N; Singh V; Mishra BN Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 3476–3489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Xiang M; Su H; Hu J; Yan Y J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Stefanachi A; Leonetti F; Pisani L; Catto M; Carotti A Molecules 2018, 23, 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Carneiro A; Matos MJ; Uriarte E; Santana L Molecules 2021, 26, 501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Sun XY; Liu T; Sun J; Wang XJ RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 10826–10847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Williams GJ; Zhang C; Thorson JS Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Noor AO; Almasri DM; Bagalagel AA; Abdallah HM; Mohamed SGA; Mohamed GA; Ibrahim SRM Molecules 2020, 25, 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Kishimoto S; Hara K; Hashimoto H; Hirayama Y; Champagne PA; Houk KN; Tang Y; Watanabe K Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Aly AA; El-Sheref EM; Mourad AE; Bakheet MEM; Bräse S Mol. Divers. 2020, 24, 477–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Khandelwal A; Crowley VM; Blagg BSJ Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 92–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Wang J; Soisson SM; Young K; Shoop W; Kodali S; Galgoci A; Painter R; Parthasarathy G; Tang YS; Cummings R; Ha S; Dorso K; Motyl M; Jayasuriya H; Ondeyka J; Herath K; Zhang C; Hernandez L; Allocco J; Basilio A; Tormo JR; Genilloud O; Vicente F; Pelaez F; Colwell L; Lee SH; Michael B; Felcetto T; Gill C; Silver LL; Hermes JD; Bartizal K; Barrett J; Schmatz D; Becker JW; Cully D; Singh SB Nature. 2006, 441, 358–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Smanski MJ; Peterson RM; Rajski SR; Shen B Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1299–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Rudolf JD; Dong LB; Shen B Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 139–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Shaaban KA; Shepherd MD; Ahmed TA; Nybo SE; Leggas M; Rohr J J. Antibiot. Tokyo. 2012, 65, 615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Huseman ED; Byl JAW; Chapp SM; Schley ND; Osheroff N; Townsend SD ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1327–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Dall’Acqua F; Vedaldi D; Gennaro A Chem. Biol. Interact. 1979, 25, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Al Haj Baddar NW; Chithrala A; Voss SR Dev. Dyn. 2019, 248, 189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Ponomareva LV; Athippozhy A; Thorson JS; Voss SR Comp. Biochem. Physiol C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 178, 128–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Dinis P; Tirkkonen H; Wandi BN; Siitonen V; Niemi J; Grocholski T; Metsä-Ketelä M PNAS Nexus. 2023, 2, pgad009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Grocholski T; Yamada K; Sinkkonen J; Tirkkonen H; Niemi J; Metsä-Ketelä M ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 850–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Yan X; Ge H; Huang T; Hindra DY; Teng Q; Crnovčić I; Li X; Rudolf JD; Lohman JR; Zhu X; Huang Y; Zhao LX; Jiang Y; Van Nieuwerburgh F; Rader C; Duan Y; Shen B mBio. 2016, 7, No. e02104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Singh S; Zhang J; Huber TD; Sunkara M; Hurley K; Goff RD; Wang G; Zhang W; Liu C; Rohr J; Van Lanen SG; Morris AJ; Thorson JS Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 3965–3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Singh S; McCoy JG; Zhang C; Bingman CA; Phillips GN Jr; Thorson JS J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 22628–22636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Singh S; Chang A; Helmich KE; Bingman CA; Wrobel RL; Beebe ET; Makino S; Aceti DJ; Dyer K; Hura GL; Sunkara M; Morris AJ; Phillips GN Jr; Thorson JS ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1632–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Singh S; Nandurkar NS; Thorson JS Chembiochem 2014, 15, 1418–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Kornfuehrer T; Romanowski S; de Crécy-Lagard V; Hanson AD; Eustáquio AS Chembiochem 2020, 21, 3495–3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Popadić D; Mhaindarkar D; Thai MHND; Hailes HC; Mordhorst S; Andexer JN RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Kabsch W Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Liebschner D; Afonine PV; Baker ML; Bunkóczi G; Chen VB; Croll TI; Hintze B; Hung LW; Jain S; McCoy AJ; Moriarty NW; Oeffner RD; Poon BK; Prisant MG; Read RJ; Richardson JS; Richardson DC; Sammito MD; Sobolev OV; Stockwell DH; Terwilliger TC; Urzhumtsev AG; Videau LL; Williams CJ; Adams PD Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2019, 75, 861–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Yennamalli R; Arangarasan R; Bryden A; Gleicher M; Phillips GN Jr J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2014, 47, 1153–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Morin A; Eisenbraun B; Key J; Sanschagrin PC; Timony MA; Ottaviano M; Sliz P Elife. 2013, 2, No. e01456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Evans R; O’Neill M; Pritzel A; Antropova N; Senior A; Green T; Žídek A; Bates R; Blackwell S; Yim J; Ronneberger O; Bodenstein S; Zielinski M; Bridgland A; Potapenko A; Cowie A; Tunyasuvunakool K; Jain R; Clancy E; Kohli P; Jumper J; Hassabis D bioRxiv, 2021, 2021.10.04.463034. [Google Scholar]

- (89).Jumper J; Evans R; Pritzel A; Green T; Figurnov M; Ronneberger O; Tunyasuvunakool K; Bates R; Žídek A; Potapenko A; Bridgland A; Meyer C; Kohl SAA; Ballard AJ; Cowie A; Romera-Paredes B; Nikolov S; Jain R; Adler J; Back T; Petersen S; Reiman D; Clancy E; Zielinski M; Steinegger M; Pacholska M; Berghammer T; Bodenstein S; Silver D; Vinyals O; Senior AW; Kavukcuoglu K; Kohli P; Hassabis D Nature. 2021, 596, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Mirdita M; Steinegger M; Söding J Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2856–2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Mirdita M; Schütze K; Moriwaki Y; Heo L; Ovchinnikov S; Steinegger M Nat. Methods. 2022, 19, 679–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Eastman P; Swails J; Chodera JD; McGibbon RT; Zhao Y; Beauchamp KA; Wang LP; Simmonett AC; Harrigan MP; Stern CD; Wiewiora RP; Brooks BR; Pande VS PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, No. e1005659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article contains Supporting Information. The structural coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as PDBID 5JR3.