Abstract

Expanding the systemic treatment options for patients with psoriasis, deucravacitinib, an oral, selective, allosteric tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor is approved in the United States, European Union, China, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and other countries for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy. Evidence suggests the comparative efficacy of systemic therapies may be different in Asian versus White patients. This systematic review and network meta‐analysis (NMA) evaluated the clinical efficacy associated with deucravacitinib and other biologic or non‐biologic systemic treatments for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Asian populations. Electronic databases were searched to identify randomized trials of the interventions of interest. Multinomial random effects models adjusting for baseline placebo risk were used to estimate Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) responses at weeks 10–16. Of 8596 studies identified, 20 were included in the NMA. The estimated PASI 75 and 90 (95% credible interval) response rates for deucravacitinib were estimated to be 66% (49%–80%) and 40% (24%–58%) in Asian populations, notably higher than placebo (6% [4%–9%] and 1% [0.8–2%]) and apremilast (24% [12%–40%] and 9% [4%–20%]). No statistically significant difference was observed in PASI 75 and 90 responses between deucravacitinib and adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, infliximab, ustekinumab, and tildrakizumab. Deucravacitinib demonstrated robust efficacy in the Asian population, with PASI 75 and 90 responses comparable to some biologics. Deucravacitinib provides a convenient oral therapy with efficacy similar to several biologic therapies.

Keywords: Apremilast, biologics, deucravacitinib, network meta‐analysis, psoriasis

1. INTRODUCTION

Systemic treatment options for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis include conventional therapies, targeted small molecules and biologics. The biologics include the first‐generation antitumor necrosis factor (anti‐TNF) inhibitors and interleukin (IL) 12/23 inhibitors as well as the second‐generation IL‐17 and IL‐23 inhibitors. Targeted small molecules include apremilast and the recent addition, deucravacitinib, an oral, selective, allosteric tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor. Deucravacitinib is approved in the United States, European Union, Japan, China, Taiwan, Korea, and other countries for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy. 1 , 2 , 3 In two global, phase 3 clinical trials (POETYK PSO‐1 and PSO‐2), deucravacitinib demonstrated superior efficacy compared with apremilast. 4 , 5

The number of available treatments makes direct comparisons of all possible combinations unfeasible; therefore, systematic literature reviews (SLRs) and network meta‐analyses (NMAs) are used to identify published literature and to evaluate the feasibility of indirectly comparing the relative effects of various therapies through a common comparator (i.e, placebo). Evidence suggests that the comparative efficacy of systemic therapies may be different in Asian patients versus those of other ethnicities due to demographic and patient characteristics, psoriatic disease characteristics, clinical practice, and lifestyle differences such as smoking and alcohol use. 6 , 7 However, NMAs specifically focused on these differences in the Asian population have not been published.

The objective of this SLR and NMA was to estimate the comparative effectiveness of deucravacitinib relative to other systemic treatments in the Asian patient population with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (particularly patients from the East Asia region).

2. METHODS

The SLR was performed following a prespecified protocol (available through the corresponding author) and conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, and following the standards required by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

2.1. Study selection and data extraction

Electronic databases were searched to identify English‐language, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published from database inception through January 3, 2023 (Tables S1‐S6). Conference proceedings from 2019 to 2022 and clinical trial registries were also searched. The methods used to evaluate studies was reported previously. 4 Eligible studies were RCTs of systemic treatments conducted in Asia (including East Asia – China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan) or with patients considered to be of Asian descent (i.e., Asian ethnicity). Eligible studies in the SLR included adults with moderate to severe psoriasis who reported Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) responses of 50%, 75%, 90%, or 100% reduction from baseline (PASI 50, PASI 75, PASI 90, or PASI 100, respectively). Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. Interventions and comparators were limited to only those treatments approved as of January 2023 in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

TABLE 1.

Study selection criteria.

| Category | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Asian adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with moderate to severe a plaque PsO who are candidates for systemic therapies |

|

| Interventions |

Biologics:

Targeted small molecules:

|

Studies that do not include a treatment arm with any of the selected comparators of interest |

| Comparisons |

|

N/A |

| Outcomes | Efficacy:

|

|

| Study designs |

|

|

| Subgroups |

|

N/A |

| Other limits |

|

Journal articles and conference abstracts not available in English |

|

Studies published outside the time frame of interest | |

|

Trials conducted outside of Asia without subgroup data for Asian patients |

Abbreviations: BID, twice a day; BIW, twice weekly; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EOW, every other week; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; N/A, not applicable; NMA, network meta‐analysis; OD, once daily; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PGA, Physician Global Assessment; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis; PSSD, Psoriasis Symptoms and Signs Diary; QW, every week; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q4W, every 4 weeks; Q8W, every 8 weeks; Q12W, every 12 weeks; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SLR, systematic literature review; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TYK2, tyrosine kinase 2.

If “moderate to severe” was mentioned, then that was sufficient criteria for inclusion regardless of the definition. However, if “moderate to severe” was not mentioned, a decision was made with clear documentation based on the PGA, PASI, body surface area (BSA), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) criteria (PGA ≥3, PASI ≥10, BSA ≥10, or DLQI ≥10).

Any dose of systemic conventional small molecule treatments was included, as doses are often modified or titrated.

The list of included studies from each publication was reviewed to identify any additionally relevant RCTs not otherwise captured by the database searches. These publications themselves were not included in the systematic literature review unless unique data were available that was not published elsewhere from the individual trials.

Study selection followed a 2‐stage screening process. First, titles and abstracts identified by the search strategies were independently reviewed by two researchers to determine eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A third reviewer resolved discrepancies, if necessary. Second, all full‐text articles deemed eligible in the first stage were reviewed independently by two researchers. The studies at the second stage met all the protocol‐specified inclusion criteria and had no exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer, as needed.

Data were extracted by one researcher and independently validated by a second researcher. Data elements of interest were study characteristics (e.g., author, publication year, sponsor, study objectives, sample size), patient characteristics (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities), treatment regimen, and outcomes related to efficacy and safety. Studies published as multiple articles (e.g., interim and/or final results) were extracted as one study. Data for subgroup analyses (e.g., previous use of biologics) were extracted by the treatment arm in each trial, if available.

2.2. Feasibility assessment

To ensure the two main NMA assumptions of consistency and similarity were met across the included trials, a feasibility assessment was performed. The characteristics of the trials identified in the SLR and connected in the network (i.e., study design, patient characteristics, interventions and comparators, and outcomes) were evaluated to determine if they were sufficiently similar to be synthesized quantitatively, and whether any imbalances in potential effect modifiers existed. Evidence of effect modification was identified through the evaluation of subgroup analyses of the included trials, published literature, and previous NICE technology appraisals for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Effect modifiers were validated by clinical experts.

2.3. NMA methodology

This study followed PRISMA Reporting Guidelines for meta‐analysis (Table S7). This methodology was described previously. In brief, this NMA used a multinomial (probit) REZ model with random effects, adjusted for baseline placebo risk (i.e., placebo response) to estimate the probability for achieving a PASI response for each treatment over 10–16 weeks, the number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve one additional PASI 75 response, and the relative odds of achieving a PASI response between treatments.

For each treatment, the NNT to achieve one additional PASI 75 or PASI 90 response relative to placebo was calculated as the reciprocal of the difference in estimated PASI 75 response rates between the active treatment and placebo.

3. RESULTS

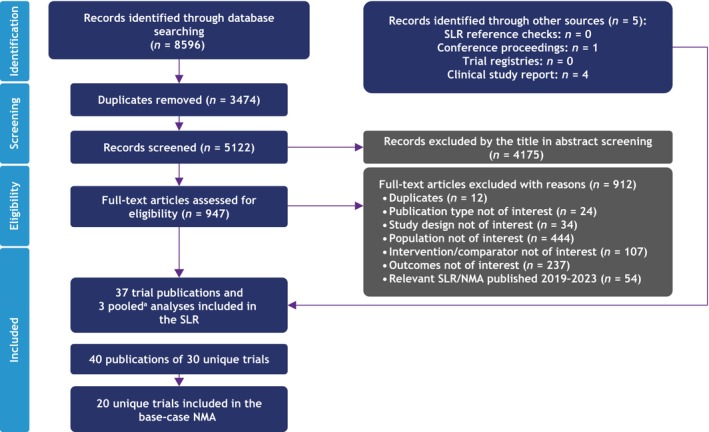

Of 8596 records identified by the searches, 20 unique RCTs were included in the NMA (Figure 1); 15 were exclusively Asian studies, while five were Asian subgroups of larger, global studies. Most studies enrolled or reported on Japanese patients (10 studies), followed by Chinese (seven studies), South Korean (five studies), and Taiwanese patients (four studies). While several trials included patients from more than one country, only one trial (ERASURE) reported data for two distinct subgroups of Asian patients (Taiwanese and Korean). Study populations were generally similar with respect to age and sex. Patients were, on average, between 32.0 and 53.3 years old, and most participants in each study were male. The mean body weight ranged from 65.8 to 80.5 kg; however, most studies reported a mean weight of less than 75 kg (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Systematic literature review (SLR) attrition diagram. aPooled analyses of randomized controlled trial were not included in the SLR unless unique data were available that were not published elsewhere. NMA, network meta‐analysis.

TABLE 2.

Study and patient characteristics included in the NMA.

| Trial (phase) | Total patients No. | Primary endpoint weeks | Severity definition | Intervention(s) and comparators | Age, mean (SD) years | Body weight mean (SD) kg | Disease duration years | Prior biologic therapy, % | Race/ethnicity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asahina 8 2010 (2/3) | 169 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Adalimumab 80 mg at weeks 0, then 40 mg Q2W | 44.2 (14.3) | 67.4 (9.9) | 14.0 | 0 a | Japanese: 100 |

| Placebo | 43.9 (10.8) | 71.3 (15.3) | 15.5 | 0 a | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Cai 9 2017 (3) | 425 | 12 | NR | Adalimumab 80 mg at weeks 0, then 40 mg Q2W | 43.1 (11.9) | 69.7 (12.4) | 14.8 | 0 a | Chinese: 100 |

| Placebo | 43.8 (12.5) | 67.0 (10.6) | 15.8 | 0 a | Chinese: 100 | ||||

| CAIN457A2318 10 (3b) | 441 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, IGA ≥3 |

Secukinumab 300 mg QW to week 4, then Q4W |

39.0 (11.6) | 73.3 (14.2) | 15.0 | 14.9 | Chinese: 100 |

| Secukinumab 150 mg QW to week 4, then Q4W | 40.5 (10.8) | 72.7 (15.5) | 16.2 | 21.8 | Chinese: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 38.7 (10.3) | 72.6 (13.3) | 14.8 | 20.9 | Chinese: 100 | ||||

| CLEAR 11 , 12 (3) | 676 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, mIGA ≥3 |

Secukinumab 300 mg QW to week 4, then Q4W |

39.1 (15.1) | NR | 12.39 | 17.4 | Korean/Taiwanese: 80 |

| Ustekinumab 45 or 90 ng at weeks 0 and 4, then Q12W | 39.8 (14.1) | NR | 12.59 | 17.9 | Korean/ Taiwanese: 80 | ||||

| ERASURE Japanese subgroup (3) | 87 | 12 | PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10, mIGA ≥3 |

Secukinumab 300 mg QW to week 4, then Q4W |

51.9 (11.8) | 76.5 (14.4) | 15.6 | 20.7 | Japanese: 100 |

|

Secukinumab 150 mg QW to weeks 4, then Q4W |

48.2 (13.1) | 74.2 (16.5) | 15.6 | 17.2 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 50.2 (13.6) | 72.6 (18.9) | 14.1 | 20.7 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| ERASURE 12 Taiwanese subgroup (3) | 738 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, mIGA ≥3 |

Secukinumab 300 mg QW to week 4, then Q4W |

38.1 (12) | 74.7 (13.4) | 13.6 |

Anti‐TNF: 25 Anti‐IL 12/23: 12.5 Other: 12.5 |

Taiwanese: 100 |

|

Secukinumab 150 mg QW to week 4, then Q4W |

39.5 (10.9) | 71.5 (15.7) | 14.5 |

Anti‐TNF: 25 Anti‐IL 12/23: 25 Other: 5 |

Taiwanese: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 40.6 (10.8) | 78.2 (20.0) | 8.3 |

Anti‐TNF: 6.7 Anti‐IL 12/23: 13.3 Other: 6.7 |

Taiwanese: 100 | ||||

| I1F‐MC‐RHBH (3) | 12 | NR | Ixekizumab 160 mg at weeks 0 then 80 mg Q2W | NR | NR | NR | NR | Chinese: 100 | |

| Placebo | NR | NR | NR | NR | Chinese: 100 | ||||

| LOTUS (3) | 322 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Ustekinumab 45 mg at weeks 0, 4, and 16 |

40.1 (12.4) | 69.6 (11.6) | 14.6 | 11.9 | Chinese: 100 |

| Placebo | 39.2 (12.2) | 69.6 (12.1) | 14.2 | 6.8 | Chinese: 100 | ||||

| Igarashi 13 2012 (2/3) | 158 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Ustekinumab 45 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then Q12W |

45.0 | 73.2 (15.4) | 15.8 | 1.6 | Japanese: 100 |

|

Ustekinumab 90 mg at weeks 0 and 5, then Q12W |

44.0 | 71.1 (14.0) | 17.3 | 0 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 49.0 | 71.2 (10.9) | 16.0 | 0 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Nakagawa 14 2016 (2) | 151 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then Q2W |

46.4 (11.8) | 72.6 (15.9) | 15.0 | 13.5 | Japanese: 100 |

| Placebo | 46.6 (10.8) | 72.2 (15.2) | 16.9 | 7.9 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Ohtsuki, 2017 (2b) | 254 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Apremilast 30 mg BID | 51.7 (12.7) | 70.1 (13.0) | 13.9 | 2.4 | Japanese: 100 |

| Placebo | 48.3 (12.0) | 68.5 (13.8) | 12.4 | 4.8 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Ohtsuki 15 2018 (3) | 192 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, IGA ≥3 |

Guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then Q8W |

47.8 (11.1) | 74.3 (16.0) | 14.4 | 17.5 | Japanese: 100 |

| Placebo | 48.3 (10.6) | 71.6 (14.0) | 13.7 | 15.6 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| POETYK PSO‐1 16 (3) | 666 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, sPGA ≥3 |

Deucravacitinib 6 mg OD |

32.0 (13.1) | NR | 12.12 | 22 | Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese: 100 |

|

Apremilast 30 mg BID |

36.2 (11.3) | NR | 12.08 | 22.6 | Asian: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 36.3 (12.3) | NR | 14.13 | 38.0 | Asian: 100 | ||||

| POETYK PSO‐3 (3) | 220 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, sPGA ≥3 |

Deucravacitinib 6 mg OD |

40.3 (12.9) | 77.5 (15.8) | 13.2 | 46.7 |

Chinese: 80.8 Korean: 19.2 |

| Placebo | 41.2 (12.3) | 74.5 (14.4) | 13.9 | 47.7 |

Chinese: 83.8 Korean: 16.2 |

||||

| PEARL (3) | 121 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Ustekinumab 45 mg at weeks 0, 4, 16 |

40.9 (12.7) | 73.1 (12.7) | 11.9 | 21.3 |

Taiwanese/Chinese: 49.2 Korean: 50.8 |

| Placebo | 40.4 (10.1) | 74.6 (13.0) | 13.9 | 15.0 |

Taiwanese/Chinese: 50 Korean: 50 |

||||

| reSURFACE 1, Japanese subgroup analysis 17 (3) | 158 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, PGA ≥3 |

Tildrakizumab 200 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then Q12W |

49.0 (11.6) | 71.4 (13.1) | NR | NR | Japanese: 100 |

|

Tildrakizumab 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then Q12W |

46.3 (11.9) | 68.4 (14.7) | NR | NR | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 50.5 (12.6) | 69.2 (14.0) | NR | NR | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Seo 18 2021 (3) | 62 | 12 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, sPGA ≥3 |

Brodalumab 210 mg at weeks 0 and 1, then Q2W |

43.5 (14.3) | 71.0 (15.0) | 10.9 | 10.0 | Korean: 100 |

| Placebo | 43.7 (15.8) | 72.8 (13.6) | 13.6 | 36.4 | Korean: 100 | ||||

| SustalMM 19 (2/3) | 171 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, sPGA ≥3 |

Risankizumab 150 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then Q12W |

53.3 (11.9) | 74.1 (16.2) | NR | 29 | Japanese: 100 |

| Placebo | 50.9 (11.2) | 75.1 (17.7) | NR | 24 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Umezawa 20 2021 (2/3) | 127 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, PGA ≥3 |

Certolizumab pegol 400 mg Q2W | 52.4 (11.6) | 71.6 (14.3) | 13.2 | Anti‐TNF: 5.7 | Japanese: 100 |

| Certolizumab pegol 400 mg at weeks 0, 2, and 4, then 200 mg Q2W | 48.4 (13.5) | 72.6 (14.3) | 12.7 | Anti‐TNF: 6.3 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 47.9 (11.4) | 75.1 (15.8) | 12.7 | Anti‐TNF: 3.8 | Japanese: 100 | ||||

| VOYAGE 1, VOYAGE 2, pooled 21 (3) | 837 | 16 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10%, IGA ≥3 |

Guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0 and 4, then Q8W |

41.2 (12.2) | 76.5 (17.43) | 15.3 | 27.7 | Taiwanese/Korean: 100 |

| Adalimumab 80 mg at weeks 0, then 40 mg Q2W | 38.1 (10.14) | 80.5 (15.68) | 12.1 | 26.7 | Taiwanese/Korean: 100 | ||||

| Placebo | 42.6 (11.75) | 74.3 (14.32) | 12.6 | 26.7 | Taiwanese/Korean: 100 | ||||

|

Yang 22 2012 (3) |

84 | 10 |

PASI ≥12, BSA ≥10% |

Infliximab 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6, then Q8W | 39.4 (12.3) | 68.2 (9.2) | 16.0 | NR | Chinese: 100 |

| Placebo | 40.1 (11.1) | 67.4 (9.9) | 16.0 | NR | Chinese: 100 |

Abbreviations: BIW, twice weekly; BSA, body surface area; IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; mIGA, IGA modified version; NMA, network meta‐analysis; NR, not reported; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PGA, Physician Global Assessment; Q2/4/8/12 W, every 2/4/8/12 weeks; QW, once weekly; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; sPGA, static PGA; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Assumed based on enrollment criteria (i.e., inclusion/exclusion criteria) regarding prior therapies (e.g., anti‐TNF).

3.1. Risk of bias

Among the 20 studies included in the NMA, 13 (65%) were judged to have some concerns about the overall risk of bias, while four (20%) were rated as low risk of bias and three (15%) as high risk of bias (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Risk of bias.

| Trial | Randomization process | Deviations from intended interventions | Missing outcome data | Measurement of the outcome | Selection of the reported results | Overall bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asahina 2010 | High | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | High |

| Cai 2017 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| CAIN457A2318 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| CLEAR 11 , 12 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| ERASURE 12 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| I1F‐MC‐RHBH | Some concerns | Some concerns | High | High | Some concerns | High |

| Igarashi 2012 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| LOTUS | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| Nakagawa 2016 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Ohtsuki 2017 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Ohtsuki 2018 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| PEARL | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| POETYK PSO‐1 16 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| POETYK PSO‐3 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| RESURFACE 1 23 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Seo 2021 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| SustaIMM | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| Umezawa | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| VOYAGE 1 21 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| VOYAGE 2 24 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Yang | Some concerns | Low | Low | High | Some concerns | High |

3.2. Feasibility assessment results

The study design of most trials was of good quality (i.e., phase 3, double‐blind, controlled trials) and it was assumed that any minor differences in trial design across the included studies would not impact the relative treatment effects. No trial was excluded from the analysis because of poor study quality based on the risk of bias assessment.

In consultation with clinical experts, the authors considered the following variables to be treatment effect modifiers: geography/ethnicity, disease severity, prior biologic exposure, and time point of assessment.

Because of the observed heterogeneity based on geography, trials not conducted in East Asian countries were excluded (i.e., India, Kuwait, and Pakistan). There is a likelihood that ethnicity could influence treatment responses in plaque psoriasis; therefore, studies that enrolled patients based on Asian ethnicity yet did not enroll patients from any Asian countries were also excluded from the NMA. Results reported at the trials' primary endpoints were prioritized. Several methods for imputing missing data were used across trials. Non‐responder imputation (or modified non‐responder imputation) was the preferred method for data included in the NMA, followed by last observation carried forward and, lastly, no imputation.

3.3. NMA results

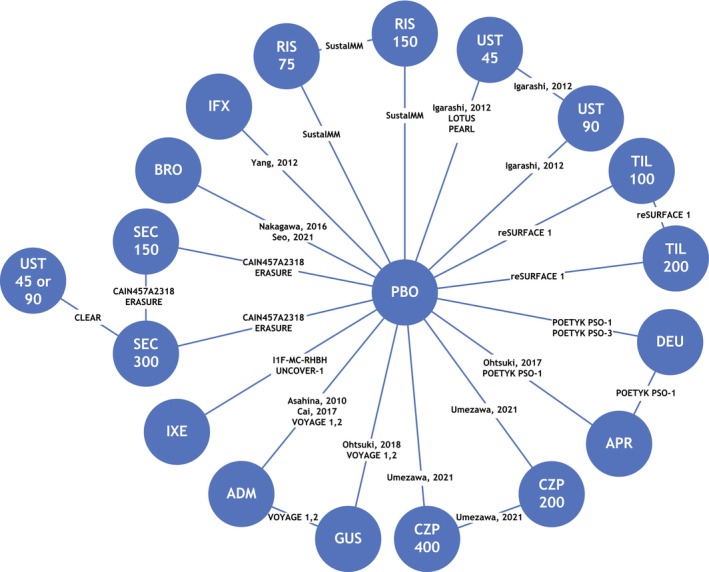

The connected network of trials included in the NMA analysis is shown in Figure 2. All treatments included in the analysis were more effective than placebo, and all biologic treatments including deucravacitinib were more effective than apremilast at achieving PASI 75 and PASI 90.

FIGURE 2.

Network diagram. ADM, adalimumab; APR, apremilast; BRO, brodalumab; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DEU, deucravacitinib; GUS, guselkumab; IFX, infliximab; IXE, ixekizumab; PBO, placebo; RIS, risankizumab; SEC, secukinumab; TIL, tildrakizumab; UST, ustekinumab.

The NMA‐estimated PASI 75 response rate of deucravacitinib was 66% (95% credible interval [CrI] 49%–80%) in Asian populations, which was notably higher than that for apremilast (24%; 95% CrI 12%–40%; Figure 3a). Based on odds ratios estimated by the NMA, no significant differences were observed between deucravacitinib and the TNF‐α inhibitors adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and infliximab, the IL‐12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, and the IL‐23 inhibitor tildrakizumab in achieving a PASI 75 response (Figure 4a).

FIGURE 3.

Estimated response rates: (a) Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75; (b) PASI 90. Data are presented as posterior median and 95% credible interval for PASI response rates and were adjusted relative to baseline placebo risk. ADM, adalimumab; APR, apremilast; BRO, brodalumab; CrI, credible interval; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DEU, deucravacitinib; GUS, guselkumab; IFX, infliximab; IL, interleukin; IXE, ixekizumab; NMA, network meta‐analysis; PASI 75, ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI, 90, ≥90% reduction from baseline in PASI; PBO, placebo; Q2W, every 2 weeks; RIS, risankizumab; SEC, secukinumab; TIL, tildrakizumab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UST, ustekinumab.

FIGURE 4.

Estimated odds ratios from the network analysis for (a) Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 and (b) PASI 90. ADM, adalimumab; APR, apremilast; BRO, brodalumab; CrI, credible interval; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DEU, deucravacitinib; GUS, guselkumab; IFX, infliximab; IL, interleukin; IXE, ixekizumab; PASI 75, ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI, 90, ≥90% reduction from baseline in PASI; PLC, placebo; RIS, risankizumab; SEC, secukinumab; TIL, tildrakizumab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UST, ustekinumab.

The PASI 90 response rate of deucravacitinib was 40% (95% Crl 24%–58%) in the Asian population, which was notably higher than that for apremilast (9%; 95% CrI 4%–20%) and placebo (1%; 95% CrI 0.8%–2%; Figure 3b). Based on odds ratios estimated in the NMA, no significant differences were observed between deucravacitinib and the TNF‐α inhibitors adalimumab, certolizumab pegol 200 mg, and infliximab, the IL‐12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, and the IL‐23 inhibitor tildrakizumab in achieving a PASI 90 response (Figure 4b).

Based on odds ratios estimated in the NMA, no significant differences were observed between deucravacitinib and the IL‐17 inhibitors risankizumab (75 mg) or secukinumab (150 mg) in achieving a PASI 50 or PASI 100 response.

The NNT to achieve a PASI 75 response rate compared with placebo for deucravacitinib was 1.67, which was substantially less than that for apremilast (5.66). The NNTs for the biologics adalimumab, certolizumab pegol (200 mg), ustekinumab, and tildrakizumab were within the lower and upper bounds for the NNT for deucravacitinib (1.33–2.33) (Figure 5a). The NNT to achieve a PASI 90 response rate compared with placebo for deucravacitinib (2.58) was substantially less than that for apremilast (12.84), and the NNTs for the biologics adalimumab, certolizumab pegol 200 mg, ustekinumab, and tildrakizumab were within the lower and upper bounds of the NNT for deucravacitinib (1.78–4.35) (Figure 5b).

FIGURE 5.

Numbers needed to treat to achieve (a) Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75 response rate and (b) PASI 90 response rate. ADM, adalimumab; APR, apremilast; BRO, brodalumab; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DEU, deucravacitinib; GUS, guselkumab; IFX, infliximab; IL, interleukin; IXE, ixekizumab; PASI 75, ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI, 90, ≥90% reduction from baseline in PASI; Q2W, every 2 weeks; RIS, risankizumab; SEC, secukinumab; TIL, tildrakizumab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UST, ustekinumab.

4. DISCUSSION

Patients receiving deucravacitinib had a higher probability of achieving PASI 75 and 90 compared with those receiving placebo and apremilast. Deucravacitinib was not significantly different from the anti‐TNFs adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab pegol, or the IL‐12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL‐23 inhibitor tildrakizumab at achieving PASI 75 and 90 responses. These results indicate that the efficacy of deucravacitinib is higher than the non‐biologic apremilast and similar to many available biologic agents. Deucravacitinib was also not significantly different from the IL‐17 inhibitors risankizumab and secukinumab, indicating that the efficacy of deucravacitinib after 10–16 weeks of treatment was similar to that of many available biologic agents. These results are potentially paradigm‐changing because the data demonstrate that a TYK2 inhibitor offers similar efficacy benefits to some biologic therapies.

The findings of this NMA are consistent with those of a recently published global phase 3 NMA, which included trials largely consisting of White patients. 4 Both analyses found deucravacitinib to be statistically significantly more likely to achieve a higher PASI 75 response than apremilast within 16 weeks of initiating treatment, although the effect was greater in Asian patients (odds ratio = 6.25) than in the global NMA (odds ratio = 2.34). Comparisons with biologics were more favorable for Asian patients than global populations that did not specifically include Asian patients, such that PASI responses for deucravacitinib were comparable to TNF‐α inhibitors adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab pegol 200 mg and infliximab, the IL‐12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, and the IL‐23 inhibitor tildrakizumab.

The results of this NMA should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. Of the 20 trials that reported sufficient information to be included in the NMA, 15 were conducted exclusively in Asian populations enrolled from Asian countries and five trials reported data from an Asian subgroup of a larger, global trial. In some cases, Asian subgroups for which geographies or ethnicities were not specified were presumed, based on the countries from which patients were enrolled. Only five trials had treatment arms with more than 100 patients, and many contained fewer than 50 patients. Comparisons with more than one study were weighted toward those with larger sample sizes. Additionally, data for certain clinically relevant outcomes or treatment differences (effect modifiers) (e.g., disease severity and previous biologic exposure) were limited or not available from all studies. Thus, effect modification testing and subgroup analyses could not be performed. Longer‐term data are important for psoriasis treatments; however, few studies with long‐term endpoints that met the inclusion criteria were identified and, therefore, a robust statistical analysis could not be conducted.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Deucravacitinib demonstrated robust efficacy in the East Asian population, with PASI 75 and PASI 90 response rates higher than those for the non‐biologic apremilast and comparable to those of several biologics. The NNT to achieve PASI 75 and PASI 90 with deucravacitinib was substantially lower than that of apremilast and was comparable to that of some biologic therapies. Deucravacitinib provides a convenient oral therapy option with efficacy similar to that of several biologic therapies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Tsen‐Fang Tsai has served as a clinical trial investigator or consultant with honoraria from AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, GSK, Janssen‐Cilag, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaEssentia, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Yayoi Tada has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Jimro, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Maruho, Sun Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tanabe‐Mitsubishi, Torii Pharmaceutical, and UCB; and honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Janssen, Jimro, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Maruho, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tanabe‐Mitsubishi, Torii Pharmaceutical, and UCB; and consulting fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lilly, Maruho, Novartis, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and UCB; Dr. Tada was not associated with the editorial process of this manuscript. Camy Kung, Yichen Zhong, Renata M. Kisa are employees and shareholders of Bristol Myers Squibb. Allie Cichewicz, Katarzyna Borkowska, and Tracy Westley are employees of Evidera, which received funding from Bristol Myers Squibb. Yu‐Huei Huang served as a clinical trial investigator or received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen‐Cilag, Novartis, and Pfizer. Xing‐Hua Gao served as a consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Janssen Xian, Lilly, and Novartis. Seong‐Jin Jo served as a clinical trial investigator, advisory board member, consultant, or received research grants or speaker's honoraria from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion Healthcare, Daewoong, Green Cross Laboratories, Janssen, Kolon Pharma, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, UCB, and Yuhan. April W. Armstrong served as a research investigator, scientific advisor, and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Arcutis, Aslan Pharmaceuticals, Beiersdorf, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Dermira, EPI Health, Incyte, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Mindera Health, Nimbus, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

Supporting information

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

Table S4.

Table S5.

Table S6.

Table S7.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Cheryl Jones of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Tsai T‐F, Tada Y, Kung C, Zhong Y, Cichewicz A, Borkowska K, et al. Indirect comparison of deucravacitinib and other systemic treatments for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Asian populations: A systematic literature review and network meta‐analysis. J Dermatol. 2024;51:1559–1571. 10.1111/1346-8138.17448

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The Bristol Myers Squibb policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers‐and‐partners/independent‐research/data‐sharing‐request‐process.html.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sotyktu [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol Myers Squibb; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sotyktu [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Bristol Myers Squibb K.K; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sotyktu [summary of product characteristics]. Dublin, Ireland: Bristol Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Operations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong AW, Warren RB, Zhong Y, Zhuo J, Cichewicz A, Kadambi A, et al. Short‐, mid‐, and long‐term efficacy of deucravacitinib versus biologics and nonbiologics for plaque psoriasis: a network meta‐analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:2839–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, Kircik L, Gordon KB, Foley P, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52‐week, randomized, double‐blinded, Program fOr Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu C, Wang G, Burge RT, Ye E, Dou G, Li J, et al. Outcomes of biologic use in Asian compared with non‐Hispanic white adult psoriasis patients from the CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:187–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Asahina A, Nakagawa H, Etoh T, Ohtsuki M. Adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a phase II/III randomized controlled study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cai L, Gu J, Zheng J, Zheng M, Wang G, Xi LY, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Chinese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 3, randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cai L, Zhang JZ, Yao X, Gu J, Liu QZ, Zheng M, et al. Secukinumab demonstrates high efficacy and a favorable safety profile over 52 weeks in Chinese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Chin Med J. 2020;133:2665–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thaci D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, Tsai T‐F, Vanaclocha F, Kingo K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Igarashi A, Kato T, Kato M, Song M, Nakagawa H. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque‐type psoriasis: long‐term results from a phase 2/3 clinical trial. J Dermatol. 2012;39:242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakagawa H, Niiro H, Ootaki K. Brodalumab, a human anti‐interleukin‐17‐receptor antibody in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a phase II randomized controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;81:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohtsuki M, Kubo H, Morishima H, Goto R, Zheng R, Nakagawa H. Guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque‐type psoriasis in Japanese patients: efficacy and safety results from a phase 3, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1053–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, Papp KA, Strober B, Thaçi D, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52‐week, randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO‐1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Igarashi A, Nakagawa H, Morita A, Okubo Y, Sano S, Imafuku S, et al. Efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from a 64‐week phase 3 study (reSURFACE 1). J Dermatol. 2021;48:853–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seo SJ, Shin BS, Lee JH, Jeong H. Efficacy and safety of brodalumab in the Korean population for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Dermatol. 2021;48:807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohtsuki M, Fujita H, Watanabe M, Suzaki K, Flack M, Huang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from the SustaIMM phase 2/3 trial. J Dermatol. 2019;46:686–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Umezawa Y, Sakurai S, Hoshii N, Nakagawa H. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: 16‐week results from a phase 2/3 Japanese study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:513–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, Shen YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double‐blinded, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang HZ, Wang K, Jin HZ, Gao TW, Xiao SX, Xu JH, et al. Infliximab monotherapy for Chinese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled multicenter trial. Chin Med J. 2012;125:1845–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Tyring SK, Sinclair R, Thaçi D, et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2017;390:276–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, Song M, Wasfi Y, Randazzo B, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:418–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

Table S4.

Table S5.

Table S6.

Table S7.

Data Availability Statement

The Bristol Myers Squibb policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers‐and‐partners/independent‐research/data‐sharing‐request‐process.html.