Abstract

Objective

Children with special healthcare needs (SHCN) due to a chronic health condition perform more poorly at school compared with their classmates. We aimed to estimate the effects of past, current, transient, emerging and persistent SHCN on school performance in primary school children.

Methods

Data from the German population-based prospective cohort study ikidS were used. The children withSHCN screener was administered before school entry (T1) and at the end of first (T2) and third grade (T3). Grades for German, maths and science (range: 1 (Very Good) to 6 (Failure)) were obtained at the end of third grade (age 8–9 years), and an average grade was calculated. Associations between the timing of SHCN and average grade were estimated by mixed linear regression models adjusted for potential confounding variables.

Results

751 children were included, and 21% had ever SHCN. Children with ever SHCN had poorer school performance than children with never SHCN (adjusted mean difference in average grade [95% CI]: 0.17 [0.06; 0.28]). SHCN in the third year were associated with a poorer average grade (0.29 [0.16; 0.41]) compared with healthy children. Only emerging (0.31 [0.15; 0.48]) and persistent (0.25 [0.07; 0.43]) SHCN were associated with average grade.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the negative effect of current, emerging and persistent SHCN on academic performance in primary school children. Consequently, students should be regularly assessed for SHCN during school age. Timely interventions may help reduce the adverse effects of chronic health conditions on academic achievements in childhood.

Keywords: Child Health, Epidemiology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This prospective cohort study demonstrates that current, emerging and persistent SHCN negatively influence school performance in primary school children.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The findings emphasise the importance of regular screening for SHCN throughout primary school. Future research should examine the educational benefits of interventions to support children with SHCN.

Introduction

A growing number of children suffer from chronic health conditions (CHCs).1 Children with CHC are at an increased risk of unfavourable psychosocial and educational outcomes like lower school attendance and poorer school performance with potentially negative long-term effects on academic attainment, socioeconomic status and general health in adulthood.2

A particularly vulnerable subgroup of children with CHC is children with special healthcare needs (SHCN). Children with SHCN are children who (i) have or are at risk for having a physical, developmental, behavioural or emotional condition and (ii) require health or related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.3 Approximately 17% to 21% of children at school age are affected.4 5 Due to their underlying long-term condition, children with SHCN require more prescription medications and use medical, social or educational services more frequently, and their functional status is decreased compared with their healthy peers.3

The development of the children with SHCN screener6 has facilitated the study of psychosocial outcomes in this group. School children with SHCN exhibit attention problems,7 miss more school days8 and have a lower grade point average9 and lower scores on academic rating scales10,12 compared with children without SHCN.

Previous studies on educational problems in children with SHCN were limited by varying definitions of SHCN, the use of unvalidated screening instruments for SHCN, cross-sectional study designs, poorly defined educational outcomes and bias due to residual confounding. In addition, there have been only a few longitudinal studies on the association between SHCN trajectories and school performance, which hampers the development and implementation of evidence-based care strategies and services for children with SHCN.

The severity of the underlying CHC itself as well as the resulting SHCN can vary over time, which would lead to changing impacts of the CHC on daily life and psychosocial outcomes. These variations would explain why some children with SHCN have poorer educational outcomes than others. For instance, a current SHCN due to a CHC may have a stronger effect on school performance than a past SHCN that dates back several years.13 A better understanding of the short- and long-term effects of SHCN will help identify children who are at risk for adverse educational outcomes and to determine the optimal time point for intervention.

The objective of this study was to estimate the effects of timing and trajectories of SHCN on school performance in primary school children. To overcome the limitations of previous studies, we applied accepted definitions and instruments, used data from a prospective cohort study and adjusted our effect estimates for a broad range of confounding variables identified through a directed acyclic graph.

Methods

The present study used data from the German population-based prospective cohort study ikidS (ikidS: ich komme in die Schule (German); I am starting school).

The ikidS cohort study

Details on background, objectives, study design, sampling strategy, instruments used and the characteristics of the cohort have been published elsewhere.11 14 In short, the project was a population-based prospective cohort study in the district of Mainz-Bingen (Rhineland-Palatinate; Germany). Children were recruited in 2015 during their mandatory preschool health examination. Assessments were made at the preschool health examination during the year before school entry, 6 weeks before school entry, 3 months after school entry and at the end of first and third grade. The regional Department of Public Health provided preschool health examination data for all study participants and, in an anonymised form, for the entire 2015 school enrolment population.

Study sample

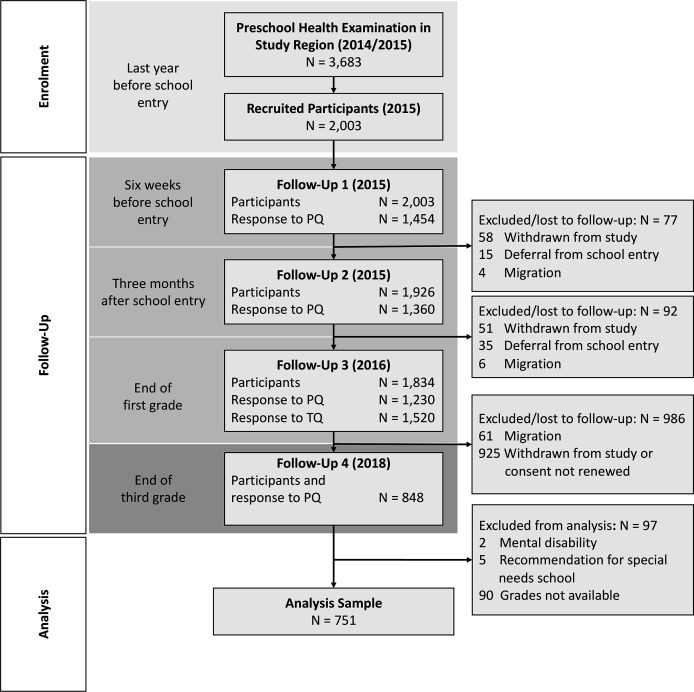

Out of 3683 children undergoing the preschool health examination, 2003 children were enrolled, and 848 parents responded to the third-grade questionnaire. For the present study, children without information on the outcome (third-grade school performance) were excluded. To ensure a more homogeneous study group, children with mental disabilities including cerebral palsy and children attending regular schools despite a recommendation for a special needs school were also excluded (if attending regular school, the latter group will have their own curriculum and an additional supporting special education teacher). The final analysis sample consisted of 751 children (figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of participants in the ikidS cohort study.

Assessment of SHCN

Children with a CHC were identified by a German version4 of the CSHCN screener.6 The 14-item parental questionnaire measures SHCN at the time of assessment by the actual use or need of these services or by functional limitations due to a CHC; it covers five different aspects of CHC consequences: (1) use or need of prescription medication; (2) above average use or need of medical, mental health or educational services; (3) functional limitations compared with others of the same age; (4) use or need of specialised therapies; and (5) treatment or counselling for emotional, behavioural, or developmental problems. Special healthcare needs due to a CHC are present if (i) at least one of the five aspects is confirmed, (ii) the respective consequence is due to any kind of CHC and (iii) the CHC has lasted or is expected to last for at least 12 months. The screener was administered 6 weeks before school entry (T1), at the end of first grade (T2) and at the end of third grade (T3).

Assessment of third-grade school performance

At the end of the third school year, grades for the school subjects German language, mathematics and science were captured in the third-grade parent questionnaire. Parents were also invited to send a copy of the third-year school certificate. These school subjects were selected as outcomes because of their association with CHC in previous studies.12

In Germany, grades in regular primary school range from 1 (very good) to 6 (failure); a lower grade therefore indicates better school performance. After investigating the pair-wise correlation between individual grades (range: r=0.50 to 0.55), an average grade was calculated if at least two out of three individual grades were available.

Statistical analysis

To assess the overall effect of SHCN as well as the timing and trajectories of SHCN, the following SHCN groups and comparisons were defined:

-

Primary analysis of overall effect.

Ever SHCN (needs reported at least once) vs never SHCN (needs never reported).

-

Secondary analysis of timing

SHCN reported prior to school entry (T1) vs no SHCN reported prior to school entry.

SHCN reported at the end of first grade (T2) vs no SHCN reported at the end of first grade.

SHCN reported at the end of third grade (T3) vs no SHCN reported at the end of third grade.

-

Secondary analysis of trajectories

Transient SHCN (needs reported before third grade but not at third grade) vs never SHCN (needs never reported).

Emerging SHCN (needs only reported at third grade) vs never SHCN (needs never reported).

Persistent SHCN (needs reported at third grade and at least once before) vs never SHCN (needs never reported)

Descriptive statistics for the sample were performed on complete cases only. The representativeness of the analysis sample was assessed by a qualitative comparison to the study population. Children with ever vs never reporting SHCN were compared with standardised mean differences.15

Multivariable linear mixed-effects regression models were used to investigate the associations between SHCN groups as independent variables and average grade as the dependent variable. Effect estimates refer to differences between children with the respective SHCN and children without the respective SHCN (reference group) and are reported as adjusted mean differences with 95% CI. A random intercept for the child’s school variable was included in all models to correct for within-school correlation.

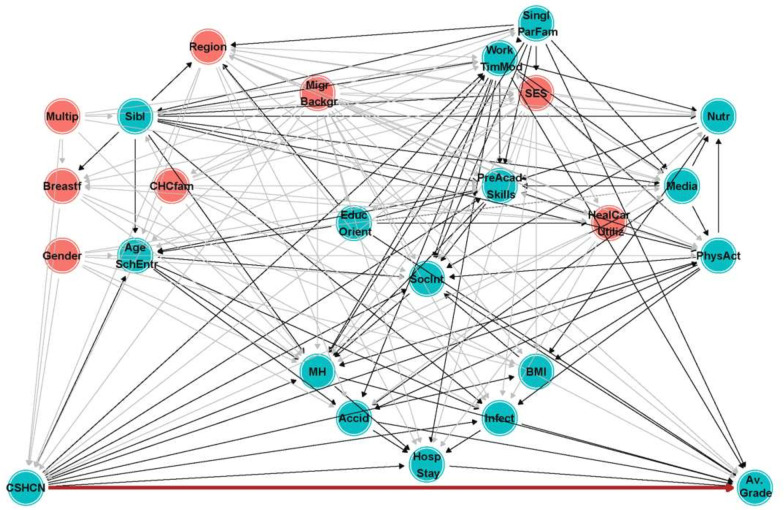

Based on a causal framework and a directed acyclic graph8 (figure 2), effect estimates were adjusted for the following confounding variables: child’s sex (male/female), immigrant status (child or at least one parent with foreign citizenship or born outside Germany), socioeconomic status (z-score based on the Winkler Index16), multiple at birth (yes/no), breastfeeding duration (none/up to 6 months/6 months or more), CHC in the family (yes/no), completion of all recommended well-child visits (proxy for parental health awareness, yes/no), and school location (urban/rural).

Figure 2. Directed acyclic graph for the association between special healthcare needs and school performance. Variables in red indicate the minimally sufficient adjustment set. Paths in grey were blocked by the adjustment set. Abbreviations: Accid, accidents; AgeSchEntr, age at school entry; Av. Grade, average grade; BMI, body mass index; Breastf, breastfeeding; CHCfam, chronic health condition in the family; EducOrient, educational orientation; HealCarUtiliz, healthcare utilisation; HospStay, hospital stay; Infect, infections; MH, mental health; MigrBackgr, immigrant status; Multip, multiple at birth; Nutr, nutrition; PhysAct, physical activity; PreAcadSkills, pre-academic skills; SES, socioeconomic status; SHCN, special healthcare needs; Sibl, siblings; SinglParFam, single-parent family; SocInt, social integration; WorkTimMod work time model.

Missing values for SHCN and confounding variables were imputed 10 times using multivariate imputation by chained equations with 100 iterations (R package mice17). Only pooled results of regression models were reported. In a sensitivity analysis, effect estimates for SHCN at the end of first grade and at the end of third grade were stepwise adjusted for previous SHCN. For example, the effect of SHCN at the end of third grade was additionally adjusted for the effect of SHCN at the end of first grade. All analyses were carried out with R version 4.1.0.18

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Cohort participants at the end of third grade differed from the study population regarding immigrant status, duration of breastfeeding and parental education (online supplemental table 1). Children included in the analysis sample had similar characteristics compared with cohort participants in third grade (online supplemental table 1). Children who ever reported SHCN were more likely to be male, have a mother with a university entrance qualification and have a father without a university entrance qualification (table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of children included in the analysis overall and stratified by special healthcare needs. Values represent proportions of complete cases.

| Overall | Never SHCN | Ever SHCN | % missing | SMD | |

| n=751 | n=543 | n=147 | |||

| Female sex | 50 | 53 | 37 | 0 | 0.33 |

| Immigrant family | 7.9 | 7.3 | 5.7 | 4.0 | 0.062 |

| Multiple at birth | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.035 |

| Breastfeeding | 2.4 | 0.083 | |||

| None | 11 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Up to 6 months | 39 | 40 | 37 | ||

| More than 6 months | 50 | 49 | 50 | ||

| Abitur (A-level exams), mother | 77 | 78 | 82 | 4.9 | 0.11 |

| Abitur (A-level exams), father | 74 | 77 | 69 | 6.4 | 0.18 |

| School location | 0 | 0.076 | |||

| District of Mainz-Bingen (rural) | 55 | 55 | 59 | ||

| City of Mainz (urban) | 45 | 45 | 41 |

SHCNspecial healthcare needsSMDstandardised mean difference

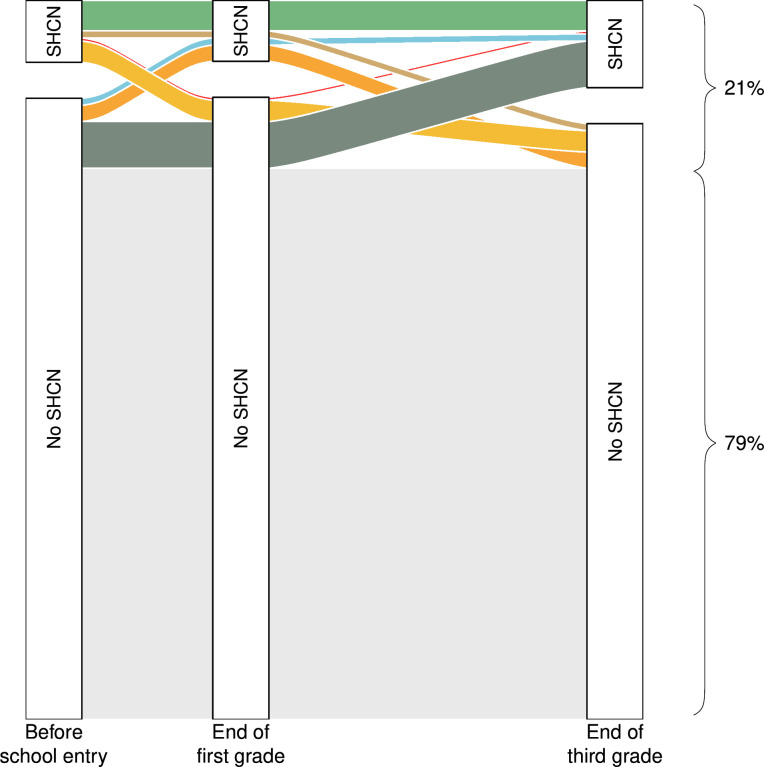

The proportion of children with SHCN was 9% prior to school entry (n=66) and 9% at the end of first grade (n=65) and increased to 13% at the end of third grade (n=96). Most children never reported having SHCN (n=543; 79%). In 147 children (21%), SHCN was reported at least once (ever SHCN); of these, 48 children (7%) had transient SHCN, 46 (7%) had emerging SHCN and 42 (6%) had persistent SHCN (figure 3).

Figure 3. Trajectories of children with special healthcare needs (SHCN) from prior to school entry to the end of third grade. Percentages on the right are the proportions of children with never and ever reporting SHCN.

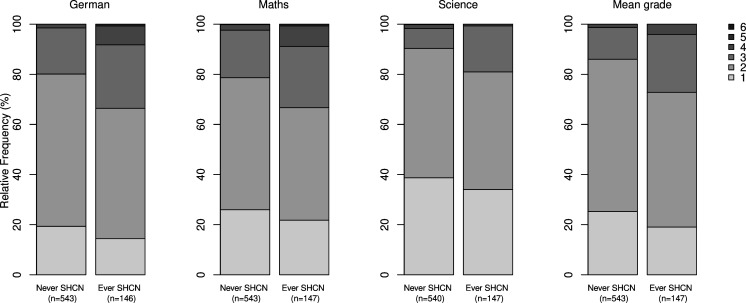

18, 24 and 37% of children achieved a grade of 1 in German language, maths and science, respectively (figure 4). Mean (SD) grades for German language, maths and science were 2.1 (0.7), 2.1 (0.8) and 1.8 (0.7), respectively. The mean (SD) average grade across these three subjects was 2.0 (0.6).

Figure 4. Distribution of German Language, mathematics, science and overall mean grades stratified by special healthcare needs. SHCN, special healthcare needs.

The mean (SD) average grade was 2.1 (0.7) in children with ever SHCN compared with 1.9 (0.6) in children with never SHCN. Multivariable regression analysis showed that children with ever SHCN performed poorer than their classmates with never SHCN (adjusted mean difference 0.17 [0.06; 0.28]).

SHCN prior to school entry (T1: adjusted mean difference 0.06 (−0.09; 0.21)) and SHCN at the end of first grade (T2: adjusted mean difference 0.11 (−0.04; 0.26)) were not related to the average grade in third year. By contrast, SHCN reported at the end of the third year (T3) was associated with the average grade in the third year (adjusted mean difference 0.29 (0.16; 0.41)). Incremental adjustments for past SHCN did not change these results (data not shown).

There was no difference in the average grade between children with transient SHCN vs never SHCN (adjusted mean difference −0.03 [-0.19; 0.14]). In contrast, children with emerging or persistent SHCN performed poorer than children with never SHCN (adjusted mean differences 0.31 (0.15; 0.48) and 0.25 (0.07; 0.43)).

Discussion

The present study showed that children in third grade with a history of SHCN performed poorer at school compared with their classmates who never reported SHCN. Current, emerging and persistent SHCN had a stronger association with school performance in third grade than past or transient SHCN in both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Our findings in a European country are consistent with the results of previous studies from the USA and Australia. In their cross-sectional study of 1457 children in fourth to sixth grade in the USA,9 Forrest et al observed a 0.19 points lower mean grade point average (verbal and math combined; range: 0–4) in children with SHCN compared with controls (2.9 vs 3.1 grade point average). An Australian longitudinal study in 6- to 7-year-old children found that emerging and persistent SHCN had an adverse effect on school performance; children with persistent SHCN had 0.21 (maths) and 0.32 (literacy) lower grade z-scores compared with children without SHCN. These findings underscore the cross-national disadvantages of children with chronic illness and SHCN in school.

Our findings are of particular importance in the German educational context, since, at the end of fourth grade, teachers provide a recommendation for the type of secondary school that a student should attend (high school vs secondary schools not leading to a high school diploma). This recommendation is largely influenced by the grades in the third year and has considerable influence on a student’s educational achievement and therefore potentially also on their socioeconomic status in adulthood.

Past and transient SHCN were not related to third-grade school performance in our study. The above-mentioned Australian study found reductions in grade z-score of 0.20 and 0.30 for maths and literacy, respectively, in 10 to 11 year old children with transient SHCN compared with their healthy classmates, but no such association in a younger cohort of 6 to 7 year old children.10 Transient SHCN may be a proxy for less severe CHCs with a high potential for spontaneous recovery or CHCs that were successfully treated before any negative impact on school performance occurred. Differences in disease severity and access to and use of healthcare services or educational support systems may therefore explain the different effects of transient SHCN on school performance between the two studies.

The strengths of the underlying ikidS project are the population-based setting, the longitudinal design and the use of a directed acyclic graph for the selection of confounding variables for the regression models.11 Our study, however, is limited by selection towards socioeconomically privileged, non-immigrant families at the assessment in third grade. Therefore, our results cannot be easily extrapolated to the population level. Since the effect of SHCN on school performance may be more pronounced in socioeconomically disadvantaged families,19 we may have underestimated the true population effect of SHCN on school performance. Lastly, SHCN differs widely by the type and severity of the underlying CHC. The effect on school performance is, therefore, not homogenous. Reported effects should rather be viewed as a pooled effect of several single CHC effects.

Conclusions

Children with SHCN have poorer third-grade school performance compared with their healthy peers. Affected children should be identified and efforts be made to meet their healthcare needs and to provide educational support services. Current, emerging and persistent SHCN are of particular importance; therefore, SHCN should be assessed regularly during school age. Future studies should investigate the educational benefits of supporting children with SHCN in school.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the documentation specialists and student research aids for conducting the surveys at school. We particularly wish to thank all the parents, children and teachers for their cooperation; they made this study possible. This work is part of the doctoral thesis of Jennifer Schlecht.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant numbers 01ER1302 and 01ER1702). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by the ethics committee of the State Medical Association of Rhineland-Palatinate (file # 837.544.13 (9229-F)), the regional Supervisory School Authority and the State Representative for Data Protection in Rhineland-Palatinate. Written informed parental consent was obtained for study participation and for each follow-up assessment. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Schlecht, Email: jennifer.schlecht@uni-mainz.de.

Jochem König, Email: koenigjo@uni-mainz.de.

Stefan Kuhle, Email: stefan.kuhle@i-med.ac.at.

Michael S Urschitz, Email: urschitz@uni-mainz.de.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Van Cleave J, Gortmaker SL, Perrin JM. Dynamics of obesity and chronic health conditions among children and youth. JAMA. 2010;303:623–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suhrcke M, de Paz Nieves C. The impact of health and health behaviours on educational outcomes in high income countries: a review of the evidence. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:137–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheidt-Nave C, Ellert U, Thyen U, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of children and youth with special health care needs (CSHCN) in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:750–6. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bethell CD, Read D, Blumberg SJ, et al. What is the prevalence of children with special health care needs? Toward an understanding of variations in findings and methods across three national surveys. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein REK, et al. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlecht J, Hammerle F, König J, et al. Teachers reported that children with special health care needs displayed more attention problems. Acta Paediatr. 2024;113:1051–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.17125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlecht J, König J, Kuhle S, et al. School absenteeism in children with special health care needs. Results from the prospective cohort study ikidS. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0287408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Riley AW, et al. School outcomes of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2011;128:303–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quach J, Barnett T. Impact of chronic illness timing and persistence at school entry on child and parent outcomes: Australian longitudinal study. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann I, Diefenbach C, Gräf C, et al. Chronic health conditions and school performance in first graders: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlecht J, König J, Urschitz MS. Chronisch krank in der Schule – schulische Fähigkeiten von Kindern mit speziellem Versorgungsbedarf. Ergebnisse der Kindergesundheitsstudie ikidS. [Chronically ill at School – School Performance in Children with Special Health Care Needs. Results Child Health Study iKidS] Klin Padiatr. 2022;234:88–95. doi: 10.1055/a-1672-4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quach J, Jansen PW, Mensah FK, et al. Trajectories and outcomes among children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e842–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urschitz MS, Gebhard B, Philippi H. Partizipation und Bildung als Endpunkte in der pädiatrischen Versorgungsforschung [Participation and education as outcomes of paediatric health services research] Kinder Jugendmed. 2016;16:206–17. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1616321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC. Using the Standardized Difference to Compare the Prevalence of a Binary Variable Between Two Groups in Observational Research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38:1228–34. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winkler J, Stolzenberg H. Der Sozialschichtindex im Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey [Social class index in the Federal Health Survey] Gesundhwesen. 1999;61:S178–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011 doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldfeld S, O’Connor M, Quach J, et al. Learning trajectories of children with special health care needs across the severity spectrum. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]