Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

Opioid agonist, partial agonist and antagonist medications are used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD). This was the first omnibus narrative systematic review of the contemporary qualitative literature on patient experiences of receiving these medications.

Design

Narrative systematic review using the sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation and research framework.

Data sources

PubMed, Embase and APA PsycINFO were searched between 1 January 2000 and 14 June 2023, with the addition of hand searches.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Qualitative and mixed methods studies among adults with experience of receiving OUD treatment medication in community and criminal justice settings.

Data extraction and synthesis

One reviewer conducted searches using the pre-registered strategy. Two independent reviewers screened studies and assessed quality using the Consolidation Criteria for Reporting Qualitative tool. Identified reports were first categorised using domains from the addiction dimensions for assessment and personalised treatment (an instrument developed to guide OUD treatment planning), then by narrative synthesis.

Results

From 1129 studies, 47 reports (published between 2005 and 2023) were included. Five major themes (and nine subthemes) were identified: (1) expectations about initiating treatment (barriers to access; motivations to receive medication); (2) responses to medication induction and stabilisation; (3) experience of the dispensing pharmacy (attending; medication dispensing); (4) experiences of maintenance treatment (services; dose adjustment; personal and social functioning); and (5) social factors (integration and stigma) and experiences of discontinuing treatment. Together these themes reflected and endorsed the importance of patient-centred care and clinically integrated services. Further qualitative research in real-world settings is needed on extended-release buprenorphine given the relative novelty of this medication option.

Conclusions

A narrative systematic review of the qualitative studies of medications for OUD endorsed the importance of patient-centred care and clinically integrated services.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019139365.

Keywords: Substance misuse, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Systematic Review, CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This review combines the narratives of patient experiences with daily, weekly and monthly medications for opioids use disorder.

Three major databases were searched following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines.

This review was challenging to conduct due to the variety of cultural and political settings.

There were limited findings on tolerance during treatment, which is specifically relevant for high-potency opioids such as fentanyl.

Introduction

Several opioid medications are available in most developed treatment systems around the world to treat opioid use disorder (OUD).1 These include a full mu-opioid receptor agonist (μ-OR; daily oral liquid methadone (MET)); a partial μ-OR receptor agonist (daily transmucosal tablet, film and lyophilisate wafer buprenorphine (BUP-SL)); and a full μ-OR antagonist (daily tablet naltrexone (NTX-SL or a monthly extended-release subcutaneous injectable formulation of naltrexone NTX-XR).2 Extended- release (weekly and monthly) subcutaneous injectable buprenorphine (BUP-XR) is now available in some treatment systems. Daily MET and BUP-SL treatment is initiated under supervision at community retail pharmacies3; extended-release medications are typically administered at the clinic.4,6

The effectiveness of MET and BUP-SL has been studied by many randomised controlled trials and observational cohort studies. Findings show that receiving either medication is associated with the reduction of non-medical opioid use and the risk of fatal opioid poisoning.3 However, a meta-analysis indicates that retention (ie, time enrolled) in daily treatments is suboptimal for many patients—ranging from 20% to 83% for BUP-SL and 31% to 84% for MET, for an average duration of 24.4 weeks.7 Extended-release formulations offer the patient simple weekly or monthly dosing. During maintenance, retention outcomes have been compared with daily treatment. In one study, patients receiving NTX-XR stayed in treatment for an average of 69.3 days compared with 63.7 days for BUP-SL.8 A study of individuals released from prison reported an 8-week retention rate for BUP-XR and BUP-SL of 69.2% and 34.6%, respectively.9 An observational study using treatment data across the USA reported a 12-month retention rate of 46% for NTX-XR, 48% for MET, 50% for BUP-XR and 66% for BUP-SL.10 The first head-to-head superiority randomised controlled trial of MET or BUP-SL versus BUP-XR over 24 weeks reported an adjusted mean days of enrolment of 129 days in the former group and 145 days in the latter group.11

Quantitative systematic reviews report the following factors to be associated with longer retention in maintenance treatment: having a supportive family; spending less time with people using illicit substances; receiving take-home doses of daily medication; and higher MET doses.12 Factors associated with shorter retention include patients of younger age; use of heroin and cocaine during treatment; legal issues; the belief that observed pharmacy dosing is stigmatising, and that prescribing regimens are inflexible to personal needs.12 13

Qualitative studies—stand-alone evaluations and those embedded in quantitative designs—can make an important contribution to understanding the patient experience of OUD treatment, through a focus on context and nuanced capture of patients’ subjective appraisal of treatment effectiveness.14 Three systematic reviews of qualitative studies have been published. The first examined barriers to accessing treatment, which included negative OUD treatment medication perceptions, a fear of stigmatisation and a perceived lack of flexibility.13 The second addressed outcomes for pregnant women, finding that there was a perceived stigma for pregnant women seeking treatment and challenges around the incompatibilities of the ‘mother’ and ‘substance user’ identity.15 The third looked at ‘lived experience’. Findings included the view that BUP-SL is less stigmatising than MET and that medication alone is insufficient to support recovery. Even though this study reported the lived experience of individuals, the search strategy was limited to studies published between 2019 and 2021.16

There has been no omnibus review of all qualitative studies reported in the scientific literature on OUD treatment medication. Our aims were: to evaluate the patient experience of OUD treatment medication and how it is delivered by treatment services; and to identify themes that can inform efforts to improve treatment delivery and effectiveness.

Methods

Design

This was a narrative systematic review of qualitative research among adults (≥18 years) with experience with daily, weekly and monthly OUD treatment medication. The protocol was prospectively registered (online supplemental file 1). The review was conducted and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols guideline.17

Search strategy

We used PubMed, Embase and APA PsycINFO electronic databases to search for contemporary literature published between 1 January 2000 and 14 June 2023 (search strategy in online supplemental file 2), supplemented by hand search. The start date was selected to encompass the contemporary standards of treatment that have been in place for the last few decades, which is reflected by the introduction of several international policies, including the Drug and Addiction Treatment Act in 2000,18 the Food and Drug Administration approval of BUP-SL in 200219 and the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence’s MET and BUP-SL protocol in 2005.20

The Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research (SPIDER) framework21 guided this strategy and the inclusion criteria (table 1). All records from the search were first exported into EndNote V.2022 (n=1175). Duplicate studies were then removed (n=46). Two reviewers (NL and CN) independently screened the studies by title and abstract using the SPIDER criteria. Each study was initially classified as ‘relevant’, ‘not relevant’ or ‘possibly relevant’. Studies classified as relevant or possibly relevant were full-text screened and then designated as ‘full text–relevant’ or ‘full text–not relevant’. Both reviewers independently screened the studies and met to review and resolve rating disparities at each stage.

Table 1. SPIDER framework.

| SPIDER | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Sample | Whole sample ≥18 years old or results pertaining to participants that are ≥18 years old. | Participants <18 years old.Stakeholders, carers or professionals.Participants were prescribed opioids for chronic pain. |

| Phenomenon of interest | The whole sample has personal experience of OUD medication. | Screening and induction of OUD medication in the emergency department setting.Non-prescribed use of opioids.Some of the samples have personal experience with OUD medication. |

| Design | All forms of study design. | Social media extracts.Electronic health records. |

| Evaluation | OUD medication delivered in community healthcare or criminal justice settings. | |

| Research type | Qualitative methodology.Mixed methodology. | Quantitative methodology.Quantifying qualitative data. |

OUDopioid use disorderSPIDERSample, Phenomena of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research

Data extraction and quality evaluation

NL extracted the following study characteristics: details of authors, country, sample size, sample age, clinical description, medication type, reported patient ethnicity, study design, topic guide and qualitative findings. Each study was assessed using the 32-item Consolidation Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) tool.23 There has recently been a critique of the assumptions made in the COREQ tool, that certain qualitative practices are standard when they are not.24 Therefore, we did not offer comment on the scores to avoid dismissal of valuable findings.

Narrative synthesis

A narrative synthesis approach was used to identify and interpret similar and differing concepts reported in the included studies.25 This proceeded in four stages: (1) Study findings were first organised using the patient-level OUD severity, concurrent problem complexity and OUD recovery structure of the Addiction Dimensions for Assessment and Personalised Treatment (ADAPT) instrument26; (2) a preliminary synthesis was constructed grouping major and minor themes in a sequence of their treatment journey; (3) a further synthesis identified relationships within and between themes; and (4) we evaluated the extent to which review findings could be generalised across clinical populations and treatment system contexts.

Patient and public involvement

None.

Results

Study selection

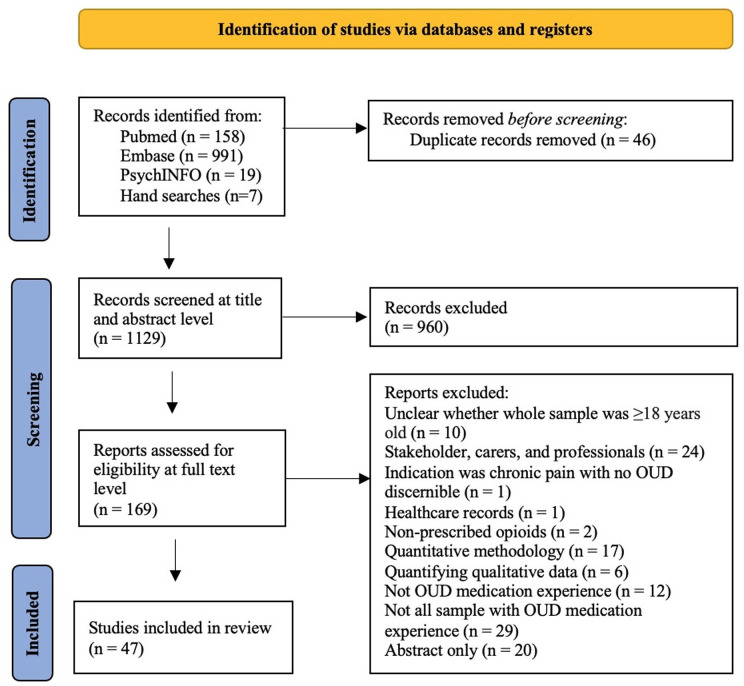

After the removal of duplicates, the search strategy yielded 1129 unique records. After screening, 960 articles did not address the study aims and were removed. 169 full-text articles were evaluated, with 122 articles removed as ineligible (figure 1).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.17OUD, opioid use disorder.

Characteristics of included studies

Forming the analysis set, the final 47 studies (among 1147 patients; 60.4% male, 27.6% female) which were included were published between 2005 and 2023. Studies originated from the USA (12 reports); Australia (seven reports); UK (six reports); Ireland (five reports); Norway (four reports); Canada (four reports); and Iran (two reports). Single studies were done in Belgium, India, Kenya, Lebanon, Mexico, Spain and Thailand. The following OUD treatment medications were evaluated in these 47 reports: MET (33 reports); BUP-SL (17 reports); BUP-XR (nine reports); and NTX-XR (two reports). Herein, when presenting the results, references with the corresponding studies are displayed.

Table 2 summarises the study characteristics. 10 were rated with high quality (COREQ total score ≥20); 32 studies were rated of medium quality (total score 11–19); and five were of low quality (total score <10) (online supplemental file 3). The most prominent COREQ factor present within lower quality was a lack of transparency in the description of study methods.

Table 2. Included study’s descriptive results.

| Author (year) | Country | Treatment type | Length of treatment |

| Allen et al (2022)39 | Australia | BUP-XR | >2 months |

| Alves et al (2021)52 | England | MET or BUP-SL | – |

| Barnett et al (2021)57 | Australia | BUP-XR | 2–24 months |

| Bornstein et al (2020)62 | USA | MET | – |

| Brenna et al (2022)42 | Norway | NTX-XR | <12 weeks |

| Carrera et al (2016)69 | Spain | MET or BUP-SL | 3 months |

| Chandler et al (2013)38 | Scotland | MET (n=17)BUP-SL (n=1)Dihydrocodeine (n=1) | <13 years |

| Cheng et al (2022)40 | USA | BUP-XR | 3–16 weeks |

| Claffey et al (2017)29 | Ireland | MET (n=6)BUP-SL (n=1) | – |

| Clay et al (2023)51 | Australia | BUP-XR | 0.5–48 months |

| De Maeyer et al (2011)55 | Belgium | MET | 5–10 years |

| Diaz-Negrete et al (2019)59 | Mexico | MET | – |

| Fox et al (2016)60 | USA | BUP-SL | – |

| Gelpi-Acosta (2015)32 | USA | MET | 1–30 years |

| Ghaddar et al (2018)36 | Lebanon | BUP-SL | 1 month to 6 years |

| Gourlay et al (2005)71 | Australia | MET | 3 months to 13 years |

| Granerud and Toft (2015)46 | Norway | BUP-SL or MET | 1–15 years |

| Havnes et al (2013)56 | Norway | BUP-SL or MET | – |

| Havnes et al (2014)63 | Norway | BUP-SL or MET | <10 years |

| Hayashi et al (2017)47 | Thailand | MET | – |

| Johnstone et al (2011)68 | Scotland | BUP-SL | – |

| Kermode et al (2020)67 | India | MET | 2–4 months |

| Khosravi and Kasaeiyan (2020)65 | Iran | MET | – |

| Lancaster et al (2022)58 | Australia | BUP-XR | 1–10 months |

| Latham (2012)61 | Ireland | MET | 1–12 years |

| Lynch et al (2020)50 | USA | BUP-XR | 3 months |

| Maina et al (2021)30 | Canada | MET | ≥6 months |

| Maina et al (2021)33 | Canada | MET | ≥6 months |

| Mayock and Butler (2021)31 | Ireland | MET | ≥10–20 years |

| McNeil et al (2015)37 | Canada | MET | – |

| Neale et al (2022)49 | England and Wales | BUP-XR | <72 hours |

| O’Byrne and Jeske Pearson (2019)66 | Ireland | MET | 3 months to 4 years |

| O’Reilly et al (2011)53 | Ireland | MET | >4 years |

| Parsons et al (2020)45 | England and Wales | BUP-XR | 1–8 months |

| Patil Vishwanath et al (2019)54 | Australia | MET (n=7)BUP-SL (n=9) | >5 years |

| Proulx and Fantasia (2021)27 | USA | MET (n=1)BUP-SL (n=9) | – |

| Pytell et al (2022)90 | USA | MET (n=12)BUP-SL (n=8) | – |

| Rahimi et al (2019)44 | Iran | MET | >6 months |

| Randall-Kosich and Andraka-Christou (2020)34 | USA | BUP-SL, MET or NTX-XR | – |

| Rawson et al (2019)28 | USA | MET or BUP-SL | ≥3 months |

| Rhodes (2018)41 | Kenya | MET | – |

| Sanders et al (2013)64 | USA | MET | – |

| Tanner et al (2011)43 | Scotland | MET or BUP-SL | – |

| Treloar et al (2022)48 | Australia | BUP-XR | 1–10 months |

| Vail et al (2021)35 | USA | BUP-SL | – |

| Vigilant (2005)91 | USA | MET | – |

| Woo et al (2017)70 | Canada | MET | – |

BUP-SLSublingual buprenorphineBUP-XRExtended-release buprenorphineMETMethadoneNTXnaltrexoneNTX-XRExtended-release naltrexone

Major and subthemes

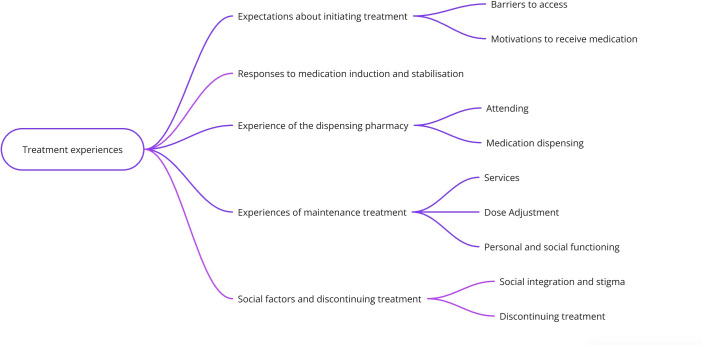

We identified five major themes and nine subthemes (figure 2).

Figure 2. Themes and subthemes.

Expectations about initiating treatment (barriers to access; motivations to receive medication).

Responses to medication induction and stabilisation.

Experience of the dispensing pharmacy (attending; medication dispensing).

Experiences of maintenance treatment (services; dose adjustment; personal and social functioning).

Social factors (integration and stigma) and experiences of discontinuing treatment.

Theme 1: expectations about initiating treatment

Barriers to access

Barriers to accessing OUD treatment services were reported in the USA and Ireland. Participants in the USA reported being unaware of treatment availability27 and believing there were insufficient numbers of licensed prescribers.28 In Ireland, within the Traveller community, there was a worry that services would require personal documentation that participants did not have.29 In both countries, patients were concerned about long waiting times for an assessment to initiate treatment.27,29

Motivations to receive medication

Participants receiving MET were motivated to engage in treatment to reduce the emotional and physical burden of OUD,30 31 having a goal of abstinence32 or to reduce health risks associated with opioid use, including taking substances by injection; and accidental drug poisoning associated with consuming heroin.33 Participants receiving BUP-SL in the USA opted for this treatment hoping the blockade effects would prevent relapse to non-medical opioid use,34 allow them to gain control over distressing cravings34 or avoid the risk of potential drug poisoning from fentanyl use.35 Also in the USA, for those receiving either BUP-SL or MET, a motivation for treatment was to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms.32 34

In Canada, Lebanon and the USA, participants were motivated by social factors, such as engaging in treatment due to improving personal finances or reducing the risk of arrest.30 32 33 36 37 New parents or pregnant women in the USA, receiving either BUP-SL or MET, viewed parenthood as a motivator to engage in treatment.27 Conversely, even when these parents and others in Scotland, wanted to engage in treatment, they feared the attention of local authority child protection services.27 38

Those receiving BUP-XR in Australia, were motivated to start treatment due to the anticipated convenience and flexibility, with more patient autonomy over treatment and increased ‘normality’ due to the absence of pharmacy visits; whereas others expressed reluctance to stop attending the pharmacy due to disruption to daily routine.39 There was also concern surrounding the BUP-XR route of administration in the USA, however, this was due to fear of needles, potential allergic response or previous adverse drug reactions.40

Often the introduction of a new OUD treatment was viewed positively. In the USA, MET, BUP-SL or NTX-XR treatment was sought out after unsuccessful peer support, counselling, residential rehabilitation and inpatient supervised withdrawal management interventions.34 The introduction of MET in Kenya, also provided hope for recovery following unsuccessful non-medical treatment attempts.41 In Norway, NTX-XR was viewed as a ‘last chance’ at achieving treatment goals after other treatments had proved unsuccessful.42

Theme 2: responses to medication induction and stabilisation

Studies from Lebanon, Iran, Scotland, England and Wales, raised concerns about the iatrogenic addiction liability of MET and BUP-SL.3643,45 Conversely, a study from Norway reported MET and BUP-SL being effective at reducing intrusive thoughts about substance use and distressing cravings.46 In terms of withdrawal symptoms, those in Kenya reported MET to be immediately effective at preventing the onset of opioid withdrawal symptoms,41 however in Canada, when transferring between different brands of MET, participants experienced precipitate withdrawal symptoms.37 Additionally, others receiving MET in Thailand, Canada and Scotland reported experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms.30 33 43 47 48

A study in Norway with participants receiving NTX-XR reported the experience of drug administration pain and gastrointestinal discomfort, with some patients reporting sadness, fear, shame and suicidal ideation during treatment.42 Following the first dose, some participants experienced relief of negative emotional symptoms; while others reported that they noticed a re-emergence of symptoms of psychological trauma and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder traits with a negative impact on daily living.42 BUP-XR was assessed in Australia, the USA, England and Wales, BUP-XR administration was described as painful,39 40 45 49 resulting in a small lump and bruising in some instances.40 45 49 Some individuals found BUP-XR to be an insufficient dose,39 49 whereas others found the dose to be sufficient45 50 and were able to surpass the dosing window.39 While receiving BUP-XR there were inconsistent reports of opioid cravings,39 40 45 51 withdrawal symptoms,39 40 49 51 gastrointestinal issues, sleep45 49 and energy levels.49

Theme 3: experience of the dispensing pharmacy

Attending

Short distances to clinics and pharmacies provided ease and convenience for those receiving MET, BUP-SL and BUP-XR in England, Wales and Australia.39 45 52 However, others receiving MET reported challenges with attending the pharmacy and clinic, due to childcare responsibilities,53 seeking or attending work31 or medical appointments.37 Logistical and financial difficulties were reported by patients needing to travel to the pharmacy for either MET or BUP-SL over long distances in Ireland, the USA and Australia, where limited public transport was available.32 53 54

Medication dispensing

The supervision of MET or BUP-SL in Australia was viewed in contrasting ways. Some patients viewed the requirement for supervised dosing as the source of external motivation for abstinence, and they regarded pharmacists as being kind, caring, courteous, understanding and considerate.54 Other patients criticised the amount of time they were required to wait before dispensing.54 Participants in Scotland felt like other customers at the pharmacy were prioritised.43 Those receiving MET in Ireland said that waiting at the pharmacy risked unwanted contact with other patients and others not in treatment.53 In Belgium, negative views towards pharmacies were moderated by access to take-home doses of MET.55 However, in Australia and Norway, there were reports of take-home doses of MET and BUP-SL being stored or diverted to others.56 57 In Australia, the concern around medication diversion was irradicated by BUP-XR, participants also appreciated the lack of time spent at clinics with this medication.57 Other benefits to BUP-XR dosing included, the minimised risk of child intoxication by take-home doses in England and Wales.45 However, others in Australia, England and Wales, viewed the lack of pharmacy contact due to BUP-XR as a loss of connection with others and their previous routine.39 49 57 58

Theme 4: experiences of maintenance treatment

Services

When discussing MET or BUP-SL treatment experiences, patients from England and Mexico reported that when attending a specialist addiction clinic, they felt welcomed and treated with care and respect.52 59 The clinical environment in the USA was regarded as a confidential and safe space to discuss problems and treatment needs.60 Patient evaluation of effective clinical practice in England endorsed the provision of accurate information about MET or BUP-SL and efforts to build trust.52 Some individuals receiving BUP-SL in the USA expressed negative interactions when at the clinic, including feeling judged and rigid practices.60 Several other patients in the USA, receiving either MET or BUP-SL found that attending the clinic to be stressful, citing experiences of exposure to individuals they believed to be intoxicated or involved in selling substances and conflict with other patients.28 Individuals accessing services for MET in Thailand reported being harassed by the police when arriving and leaving the premises.47

With regards to both MET and BUP-SL treatment services, patients in Mexico, valued the provision of psychotherapy and group and family therapies within the clinic to support recovery.59 In England and Ireland, patients approved of efforts to integrate OUD treatment with other health, social and welfare services and professional teams.52 61 Individuals in Canada appreciated timely access to local mental health services and help for those experiencing homelessness or socioeconomic hardship.30 This was echoed by patients in Norway, feeling demotivated when they perceived that opioid abstinence was the primary focus of treatment and their housing or education needs were not considered.46 In England, some patients stated that they preferred to receive MET or BUP-SL treatment in the primary care setting, because this was viewed as an anonymous and confidential space where OUD was not a focus and a long-term therapeutic relationship could be fostered.52

When there were female-specific accounts of treatment services, women in Iran, receiving MET reported feeling judged, abused, outcasted and isolated.44 Pregnant and postpartum women receiving MET in the USA reported fear, shame and concern about their newborn baby experiencing withdrawals.62 These women felt like their pregnancy was disapproved of and there was limited communication regarding MET and reproduction.62 Other pregnant women in the USA, receiving MET or BUP-SL, felt judged by healthcare providers when disclosing their treatment status and there were reports that they were accused of intentionally harming their unborn child through exposure to OUD medication.27 The same individuals reported feeling anxious about the disconnection between drug treatment and family services, which was attributed to receiving inconsistent information.27

Dose adjustment

There were many accounts of concerns around dose adjustments for MET. Some patients in the USA, Ireland and Norway felt there was little or no consultation about changes made to their prescription,32 53 63 and in Ireland, patients reported that a request for dose reduction was declined.31 There were also reports in the USA and Iran, where a MET dose increase was given even when the patient cited treatment-emergent adverse reactions including feeling numb, swollen and gaining weight.64 65 Some individuals in Ireland felt uncomfortable about the transactional nature of a negative urine sample requirement for take-home MET medication66; whereas, others were stoical.53 In the USA, individuals were not happy about the automatic MET dose increase when they provided an opioid-positive urine sample.64 Patients receiving either BUP-SL or MET in Norway reported opioid-positive urine samples resulting in a return to a less flexible prescription.46

Personal and social functioning

There were many patient evaluations of personal and social functioning. Participants reported an improvement in their overall health and well-being,31 43 54 67 self-esteem43 67 and self-confidence43 46 49 while receiving MET or BUP-SL. Additionally, those receiving MET reported an increase in life purpose.31 55 MET, BUP-SL31 38 57 67 68 and BUP-XR40 45 48 50 58 were viewed as promoting a ‘normal life’ and giving respite from a chaotic lifestyle.41 54 55 63 Patients receiving BUP-XR, MET or BUP-SL reported being on treatment allowed them to participate in activities to attain and engage in paid work.40 45 54 58 67 While receiving MET,41 43 55 and BUP-SL,43 participants reported experiencing mental clarity. Mental clarity was not always viewed in a positive light, as in some instances this led to boredom.43 However, when patients receiving BUP-XR, reflected on their experience of daily dosing, they reported experiencing constant thoughts about their dose and collection,45 48 which resulted in feeling trapped and controlled by the medication and dosing regimen.48 Due to the monthly dosing regimen, individuals receiving BUP-XR felt free of thought40 45 48 as they no longer had a daily reminder of medication or worry about medication being stolen, lost or running out.40 48

There were reports from Ireland and Belgium, that MET led to a sense of emotional blunting which inhibited the patient’s ability to cope with everyday life and progress.31 55 In Spain, there were reports that BUP-SL was viewed as more desirable than MET, due to facilitating lifestyle changes, such as less treatment contact time and more take-home doses, resulting in less time absent from work.69 In Lebanon, BUP-SL was viewed as a more socially acceptable treatment than MET.36 This may be due to how highly stigmatising MET is,38 55 66 citing its green colour and various negative connotations associated with its name.68 In terms of BUP-XR, the patient endorsed its opioid-blocking effects,39 40 43 45 however, there were both negative and positive impacts on mood.45 49 51

In Spain, Belgium and Ireland, patients receiving MET found the treatment to be financially beneficial,69 due to it acting as a cheaper alternative to heroin and removing the need to commit a crime to purchase heroin.31 55 Participants in Iran, Lebanon and the USA found that receiving MET or BUP-SL increased their financial difficulties because they were required to cover some of the medication and dispensing costs.27 36 65 When comparing daily medication to BUP-XR costs in Australia, participants found BUP-XR to be a more affordable option due to fewer dispensing fees.39

In terms of treatment disclosure, individuals in Ireland, the USA and Canada feared disclosing MET due to the stigma around previously injecting substances,62 wanting to avoid conflict with friends and family70 and avoiding judgement from future partners.66 Whereas those receiving MET in Australia, who did not identify with addiction, opted for non-disclosure and others who identified with being ‘functional’ and using MET to manage withdrawals, and felt like they had to disclose their treatment status to be able to advocate for themselves in healthcare settings.71

An important aspect of treatment for those receiving MET in Iran was the provision of practical support from family members.44 MET treatment in Kenya was also viewed positively in terms of family dynamics as it helped build harmonious relationships, trust and reduce conflict.41 In India, some family members were accepting of MET; however, others were distrusting of patients receiving MET due to a lack of understanding of the treatment and addiction.67

Theme 5: social factors and discontinuing treatment

Societal integration and stigma

Individuals from Mexico, reported feeling as though MET treatment assisted them in feeling more integrated into mainstream society.59 However, in Canada, Iran and the USA participants reported negative feelings while receiving MET, for example, low self-esteem44 70; guilt,70 shame62 70; or feeling disregarded.62 There were also many reports of stigma when participants were receiving MET, individuals in Canada reported negative attitudes from friends, family and healthcare workers,70 and those from Australia reported negative attitudes from pharmacy staff, and doctors.71 In Scotland, those receiving BUP-SL in prison reported stigma from prison staff.68 When receiving BUP-XR in Australia and USA, participants reflected on how both MET and BUP-SL were stigmatising during all aspects of treatment and how BUP-XR allowed them to feel like normal members of society.48 50 This was echoed when those receiving MET or BUP-SL, were still viewed as being ‘addicts’ even if they were abstinent from non-medical substances.28 38 41 46 66 68 70

Discontinuing treatment

Many reasons were given for the decision to discontinue treatment. In the USA, patients receiving MET, BUP-SL or NTX-XR reported discontinuing due to not wanting to be on a medication for a long time and risk dependency.34 Others in the USA and Canada receiving either MET, BUP-SL or NTX-XR discontinued due to missing treatment doses or missing treatment payments30 33 34; others also feared disclosing treatment to employers and the need for frequent healthcare visits.34

There were various reports of why MET was discontinued in Canada, including missing treatment doses, missing treatment payments30 33 34 and a lack of viable or reliable transport to pharmacies.30 33 37 There were also various patient-level factors, including resumed use of opioids; the desire to feel the effects of non-medical drugs; psychological distress33; and the lack of support from family members.30 33 In terms of terminating long-acting OUD treatment formulas, some decided to terminate NTX-XR treatment due to not achieving treatment goals,34 42 wanting to return to MET or BUP-SL following unexpected adverse reactions42 or no longer wanting to pay monthly physician costs that are required in the USA.34 Individuals chose to discontinue BUP-XR due to persistent withdrawals, significant administration pain,40 unexpected adverse reactions51 or a fear of becoming too comfortable on the medications.45 Some participants receiving BUP-XR also reported wanting to return to BUP-SL as they desired the euphoric feeling from BUP-SL.40

Discussion

The main findings from this narrative systematic review include: the prominent motivation to engage in OUD medication was to avoid the negative aspects of OUD and achieve a ‘normal life’. There were inconclusive reports on the effectiveness of most OUD medications in this review, however, there were largely negative reactions reported when receiving NTX-XR. There were many financial and time barriers to attending the pharmacy while receiving daily medication, and once at the pharmacy, there were reports of challenging encounters with other customers. In some instances, this was mitigated by an increase in take-home doses or BUP-XR. Most services were viewed positively, apart from those in the USA and Thailand, due to negative experiences with peers or law enforcement. Participants found adjustments to MET dose challenging, and often not a collaborative experience with clinics. MET, BUP-SL and BUP-XR were generally viewed positively in terms of personal and social functioning. However, when comparing BUP-XR to MET and BUP-SL, BUP-XR was viewed as less stigmatising.

In this review, the aim of treatment for most individuals was abstinence from non-medical opioids and to lead a ‘normal’ life. There appear to be some aspects of OUD medication treatment that act as barriers to attaining a ‘normal’ life including the following structural and logistical factors we have reviewed: difficulties initiating treatment, a large time and financial burden to maintain treatment, frequent appointments at the clinic and pharmacy and the requirement to restart treatment if three consecutive doses of BUP-SL or MET are missed.72 Participants often reported an increase in take-home dose and BUP-XR to be a mitigating factor to the challenges faced with frequent pharmacy visits. The challenges with frequent pharmacy visits may contribute to the large range in retention rates for BUP-SL and MET,7 with protective factors of retention including more take-home doses12 and lower rates of retention with observed dosing and inflexible prescribing.13 This may be a factor as to why early clinical trial findings for BUP-XR retention rates are higher.8,11

Some patients found MET dose adjustments to not be a collaborative experience, which may be due to the full agonist properties of this treatment, meaning that high doses or the concomitant use of alcohol or other sedative substances can cause sedation and respiratory depression.73 This may be a barrier to an autonomous or collaborative therapeutic relationship, due to safety concerns. Additionally, often patients receiving NTX-XR reported adverse reactions to treatment, which was reported as a reason for discontinuation and may be a reason for previous research reporting naltrexone formulas having the highest disenrolment rates.74

It was apparent that some patients and service providers viewed MET with negative connotations linked to its name, the colour of the liquid and the experience of observed daily dosing at the pharmacy. BUP-SL and BUP-XR were identified as more socially acceptable than MET75 76 . This may be due to the pharmacological properties of buprenorphine reducing safety concerns and easily faciliating larger dispensing intervals, in the form of either monthly dosing or increased take-home doses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the previous strict pharmacy dispensing policy was tested. Findings suggest that patients felt trusted and positively regarded an increase in take-home doses and longer dispensing intervals.77 This is also reflected in this review, by participants appreciating the longer treatment intervals that BUP-XR treatment facilitates. However, early real-world treatment dropout rates for BUP-XR are higher than those for BUP-SL,10 which suggests that interval dosing in itself may not be sufficient to facilitate a normal life and meet all patient needs. One reason for this reported in the USA, may include that the cost incurred by the patient receiving BUP-XR outweighs the benefits of the treatment.78 However, in Australia BUP-XR was more cost-effective than BUP-SL for patients.39 We currently do not have data for countries where there is a lower cost incurred by patients. This suggests further longer-term research is required for those receiving BUP-XR.

In conjunction with pharmacotherapy, psychological and social support for OUD needs to be addressed.79 Some participants stated that when they were on treatment, suppressed emotions arose and other participants found that there was either a lack of access or barriers to receiving psychological support. Integrated healthcare delivered by a multidisciplinary team was a commonly expressed desire. The historical separation of services could reflect a prevailing view of substance use as a social and criminal issue, rather than a public health matter. In recent years, there has been a need for better individual and public integration with other health services, to reduce health disparities and economic costs.80 It has also been found that separating services reinforces stigma, even though many patients who attend emergency departments, hospitals and general practitioner81 settings have co-occurring substance use disorders.82,85

We acknowledge several limitations. First, the review was challenging to conduct due to the variety of cultural and political settings in which treatments are delivered and experienced. We aimed to identify factors that could be addressed to improve patient experience and effectiveness, but we readily acknowledge that cultural, administrative and legal issues may be barriers to change for some treatment systems and service providers—especially those where increased flexibility in prescribing regimens is not permissible. Second, the constructs of the ADAPT26 that were not featured in the data extraction were the degree of opioid tolerance and treatment cessation. This suggests individuals using high-potency opioids (such as fentanyl and its analogues86,88) are a high-priority population for qualitative research. Longitudinal qualitative studies are needed on how these patients experience treatment induction in the context of high opioid tolerance. Third, in the 18 years (2005–2023) from the first to the last published study, one-quarter of the studies included were conducted in the USA and the substantial increase in the incidence of fatal opioid-related poisonings,89 shifts in prescribing policy and the broadening of treatment availability through waivered office-based prescribers,28 are all contextual factors which may limit the generalisability of findings to some treatment systems internationally.

In conclusion, the qualitative literature on OUD treatment offers valuable knowledge about the patient experience to improve service delivery. The themes identified in the review endorse patient-centred care and clinically integrated OUD treatment provision. Due to the relative novelty of BUP-XR, further research is needed in real-world settings.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors kindly acknowledge Francesca Small for administrative support and cross-checking of the quality rating of reviewed articles.

Footnotes

Funding: Salary costs of corresponding author NL were supported by a collaborative study funded by Indivior UK Limited to King’s College London (the sponsor, grant number: KCLEXPOINDV19) for a randomised controlled trial of BUP-XR versus MET or BUP-SL. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation or report writing. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Indivior.

Prepub: Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-088617).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Natalie Lowry, Email: natalie.m.lowry@kcl.ac.uk.

Carina Najia, Email: carina.1.najia@kcl.ac.uk.

Mike Kelleher, Email: mike.kelleher@slam.nhs.uk.

Luke Mitcheson, Email: luke.mitcheson@slam.nhs.uk.

John Marsden, Email: john.marsden@kcl.ac.uk.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study.

References

- 1.Public Heath England Part 1: introducing opioid substitution treatment (OST) 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/opioid-substitution-treatment-guide-for-keyworkers/part-1-introducing-opioid-substitution-treatment-ost Available.

- 2.Taylor JL, Samet JH. Opioid Use Disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:ITC1–16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202201180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence. 2007. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta114 Available.

- 4.Marsden J, Kelleher M, Hoare Z, et al. Extended-release pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder (EXPO): protocol for an open-label randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of injectable buprenorphine versus sublingual tablet buprenorphine and oral liquid methadone. Trials. 2022;23:697. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06595-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, et al. Injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) for opioid dependence: long-term safety and effectiveness. Addiction. 2013;108:1628–37. doi: 10.1111/add.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Opioid dependence: buprenorphine prolongedrelease injection (buvidal) nice. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/es19/chapter/Key-messages Available.

- 7.Klimas J, Hamilton M-A, Gorfinkel L, et al. Retention in opioid agonist treatment: a rapid review and meta-analysis comparing observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Syst Rev. 2021;10:216. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01764-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif Z-E-H, et al. Effectiveness of Injectable Extended-Release Naltrexone vs Daily Buprenorphine-Naloxone for Opioid Dependence: A Randomized Clinical Noninferiority Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:1197–205. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JD, Malone M, McDonald R, et al. Comparison of Treatment Retention of Adults With Opioid Addiction Managed With Extended-Release Buprenorphine vs Daily Sublingual Buprenorphine-Naloxone at Time of Release From Jail. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2123032. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.23032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan JR, Walley AY, Murphy SM, et al. Characterizing initiation, use, and discontinuation of extended-release buprenorphine in a nationally representative United States commercially insured cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225:S0376-8716(21)00259-3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsden J, Kelleher M, Gilvarry E, et al. Superiority and cost-effectiveness of monthly extended-release buprenorphine versus daily standard of care medication: a pragmatic, parallel-group, open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. E Clin Med. 2023;66:102311. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor AM, Cousins G, Durand L, et al. Retention of patients in opioid substitution treatment: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0232086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall NY, Le L, Majmudar I, et al. Barriers to accessing opioid substitution treatment for opioid use disorder: A systematic review from the client perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:S0376-8716(21)00146-0. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakshman M, Sinha L, Biswas M, et al. Quantitative vs qualitative research methods. Indian J Pediatr. 2000;67:369–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02820690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuda-McCaie F, Kotera Y. A qualitative meta-synthesis of pregnant women’s experiences of accessing and receiving treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022;41:851–62. doi: 10.1111/dar.13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Techau A, et al. The Lived Experience of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder: Qualitative Metasynthesis. J Addict Nurs. 2022;34:E119–34. doi: 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Drug addiction treatment act of 2000. in: services. u.s. department of health & human services, editor. an act to amend the controlled substances act with respect to registration requirements for practitioners who dispense narcotic drugs in schedule iii, iv, or v for maintenance treatment or detoxification treatment. 2000. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BILLS-106hr2634eh/summary Available.

- 19.McCormick MC. Subutex and Suboxone Approval Letter, (2002). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2002. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2002/20732,20733ltr.pdf Available.

- 20.Taylor R. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence. in: national institute of health and care excellence, editor. west midlands. 2005. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta114/documents/drug-misuse-methadone-and-buprenorphine-final-protocol2 Available.

- 21.Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:1435–43. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The EndNote Team . EndNote. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate Analytics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. How do you solve a problem like COREQ? A critique of consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research. Elsevier; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popay J. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1:b92. doi: 10.13140/2.1.1018.4643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsden J, Eastwood B, Ali R, et al. Development of the Addiction Dimensions for Assessment and Personalised Treatment (ADAPT) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proulx D, Fantasia HC. The Lived Experience of Postpartum Women Attending Outpatient Substance Treatment for Opioid or Heroin Use. J Midwife Womens Health . 2021;66:211–7. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rawson RA, Rieckmann T, Cousins S, et al. Patient perceptions of treatment with medication treatment for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in the Vermont hub-and-spoke system. Prev Med. 2019;128:S0091-7435(19)30261-0. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claffey C. Exploring Irish travellers’ experiences of opioid agonist treatment: A phenomenological study. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl. 2017;19:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maina G, Fernandes de Sousa L, Mcharo S, et al. Risk perceptions and recovery threats for clients with a history of methadone maintenance therapy dropout. J Subst Use. 2021;26:594–8. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2020.1867661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayock P, Butler S. Pathways to “recovery” and social reintegration: The experiences of long-term clients of methadone maintenance treatment in an Irish drug treatment setting. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:S0955-3959(20)30430-8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelpi-Acosta C. Challenging biopower: “Liquid cuffs” and the “Junkie” habitus. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2015;22:248–54. doi: 10.3109/09687637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maina G, Marshall K, Sherstobitof J. Untangling the Complexities of Substance Use Initiation and Recovery: Client Reflections on Opioid Use Prevention and Recovery From a Social-Ecological Perspective. Subst Abuse. 2021;15:11782218211050372. doi: 10.1177/11782218211050372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Randall-Kosich O, Andraka-Christou B. Reasons for Starting and Stopping Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Naltrexone Treatment. J Addict Med. 2020;14:e414–5. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vail W, Faro E, Watnick D, et al. Does incarceration influence patients’ goals for opioid use disorder treatment? A qualitative study of buprenorphine treatment in jail. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;222:S0376-8716(21)00024-7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaddar A, Khandaqji S, Abbass Z. Challenges in implementing opioid agonist therapy in Lebanon: a qualitative study from a user’s perspective. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2018;13:14. doi: 10.1186/s13011-018-0151-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNeil R, Kerr T, Anderson S, et al. Negotiating structural vulnerability following regulatory changes to a provincial methadone program in Vancouver, Canada: A qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:168–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandler A, Whittaker A, Cunningham-Burley S, et al. Substance, structure and stigma: parents in the UK accounting for opioid substitution therapy during the antenatal and postnatal periods. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24:e35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen E, Samadian S, Altobelli G, et al. Exploring patient experience and satisfaction with depot buprenorphine formulations: A mixed-methods study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2023;42:791–802. doi: 10.1111/dar.13616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng A, Badolato R, Segoshi A, et al. Perceptions and experiences toward extended-release buprenorphine among persons leaving jail with opioid use disorders before and during COVID-19: an in-depth qualitative study. Addict Sci Clin Pract . 2022;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s13722-022-00288-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhodes T. The becoming of methadone in Kenya: How an intervention’s implementation constitutes recovery potential. Soc Sci Med. 2018;201:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenna IH, Marciuch A, Birkeland B, et al. “Not at all what I had expected”: Discontinuing treatment with extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX): A qualitative study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;136:S0740-5472(21)00393-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanner GR, Bordon N, Conroy S, et al. Comparing methadone and Suboxone in applied treatment settings: the experiences of maintenance patients in Lanarkshire. J Subst Use. 2011;16:171–8. doi: 10.3109/14659891.2010.526480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahimi S, Jalali A, Jalali R. Psychological Needs of Women Treated with Methadone: Mixed Method Study. Alcohol Treat Q. 2019;37:328–41. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2018.1554982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parsons G, Ragbir C, D’Agnone O, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes, Experiences and Satisfaction with Weekly and Monthly Injectable Prolonged-Release Buprenorphine. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2020;11:41–7. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S266838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Granerud A, Toft H. Opioid dependency rehabilitation with the opioid maintenance treatment programme - a qualitative study from the clients’ perspective. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2015;10:35. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi K, Ti L, Ayutthaya PPN, et al. Barriers to retention in methadone maintenance therapy among people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand: a mixed-methods study. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14:63. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0189-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Treloar C, Lancaster K, Gendera S, et al. Can a new formulation of opiate agonist treatment alter stigma?: Place, time and things in the experience of extended-release buprenorphine depot. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;107:S0955-3959(22)00204-3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neale J, Parkin S, Strang J. How do patients feel during the first 72 h after initiating long-acting injectable buprenorphine? An embodied qualitative analysis. Addiction. 2023;118:1329–39. doi: 10.1111/add.16171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynch K, Frost M, Chokshi S, et al. The effects of buprenorphine depot implants on patient sleep and quality of life: findings from a mixed-methods pilot trial. Addict Res Theory. 2020;28:152–9. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2019.1613522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clay S, Treloar C, Degenhardt L, et al. “I just thought that was the best thing for me to do at this point”: Exploring patient experiences with depot buprenorphine and their motivations to discontinue. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;115:S0955-3959(23)00051-8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alves PCG, Stevenson FA, Mylan S, et al. How do people who use drugs experience treatment? A qualitative analysis of views about opioid substitution treatment in primary care (iCARE study) BMJ Open. 2021;11:e042865. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Reilly F, O’Connell D, O’Carroll A, et al. Sharing control: user involvement in general practice based methadone maintenance. Ir J Psychol Med. 2011;28:129–33. doi: 10.1017/S079096670001209X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patil Vishwanath T, Cash P, Cant R, et al. The lived experience of Australian opioid replacement therapy recipients in a community-based program in regional Victoria. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019;38:656–63. doi: 10.1111/dar.12979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Maeyer J, Vanderplasschen W, Camfield L, et al. A good quality of life under the influence of methadone: a qualitative study among opiate-dependent individuals. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:1244–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Havnes IA, Clausen T, Middelthon AL. “Diversion” of methadone or buprenorphine: “harm” versus “helping.”. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnett A, Savic M, Lintzeris N, et al. Tracing the affordances of long-acting injectable depot buprenorphine: A qualitative study of patients’ experiences in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;227:S0376-8716(21)00454-3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lancaster K, Gendera S, Treloar C, et al. The Social, Material, and Temporal Effects of Monthly Extended-Release Buprenorphine Depot Treatment for Opioid Dependence: An Australian Qualitative Study. Contemp Drug Probl. 2023;50:105–20. doi: 10.1177/00914509221140959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diaz-Negrete DB, Velázquez-Altamirano M, Benítez-Villa JL, et al. Psychosocial reintegration process in patients who receive maintenance treatment with methadone: A qualitative analysis. Salud Ment . 2019;42:173–84. doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2019.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fox AD, Masyukova M, Cunningham CO. Optimizing psychosocial support during office-based buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Patients’ experiences and preferences. Subst Abus. 2016;37:70–5. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1088496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latham L. Methadone Treatment in Irish General Practice: Voices of Service Users. Ir J Psychol Med. 2012;29:147–56. doi: 10.1017/S0790966700017171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bornstein M, Berger A, Gipson JD. A mixed methods study exploring methadone treatment disclosure and perceptions of reproductive health care among women ages 18-44 years, Los Angeles, CA. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;118:S0740-5472(20)30375-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Havnes IA, Clausen T, Middelthon AL. Execution of control among “non-compliant”, imprisoned individuals in opioid maintenance treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanders JJ, Roose RJ, Lubrano MC, et al. Meaning and methadone: patient perceptions of methadone dose and a model to promote adherence to maintenance treatment. J Addict Med. 2013;7:307–13. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318297021e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khosravi M, Kasaeiyan R. Reasons for Increasing Daily Methadone Maintenance Dosage among Deceptive Patients: A Qualitative Study. J Med Life. 2020;13:572–9. doi: 10.25122/jml-2020-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Byrne P, Jeske Pearson C. Methadone maintenance treatment as social control: Analyzing patient experiences. Nurs Inq. 2019;26:e12275. doi: 10.1111/nin.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kermode M, Choudhurimayum RS, Rajkumar LS, et al. Retention and outcomes for clients attending a methadone clinic in a resource-constrained setting: a mixed methods prospective cohort study in Imphal, Northeast India. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17:68. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00413-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnstone A, Duffy T, Martin C. Subjective effects of prisoners using buprenorphine for detoxification. Int J Prison Health. 2011;7:52–65. doi: 10.1108/17449201111256907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carrera I. Study on users’ perception of agonist opioid treatment in the galician network of drug addiction. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl. 2016;18:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woo J, Bhalerao A, Bawor M, et al. “Don’t Judge a Book Its Cover”: A Qualitative Study of Methadone Patients’ Experiences of Stigma. Subst Abuse. 2017;11:1178221816685087. doi: 10.1177/1178221816685087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gourlay J, Ricciardelli L, Ridge D. Users’ experiences of heroin and methadone treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1875–82. doi: 10.1080/10826080500259497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clinical Guidelines on Drug Misuse and Dependence Update 2017 Independent Expert Working Group Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management, Department of Health, London. 2017.

- 73.Dematteis M, Auriacombe M, D’Agnone O, et al. Recommendations for buprenorphine and methadone therapy in opioid use disorder: a European consensus. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:1987–99. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1409722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tompkins CNE, Neale J, Strang J. Opioid users’ willingness to receive prolonged-release buprenorphine depot injections for opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Madden EF, Barker KK, Guerra J, et al. Variation in intervention stigma among medications for opioid use disorder. SSM - Qual Res Health. 2022;2:100161. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scott G, Turner S, Lowry N, et al. Patients’ perceptions of self-administered dosing to opioid agonist treatment and other changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e069857. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morgan JR, Assoumou SA. The limits of innovation: Directly addressing known challenges is necessary to improve the real-world experience of novel medications for opioid use disorder. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30:1285–7. doi: 10.1111/acem.14814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marsden J, Stillwell G, James K, et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of an adjunctive personalised psychosocial intervention in treatment-resistant maintenance opioid agonist therapy: a pragmatic, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:391–402. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Day E. Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;37:382. doi: 10.1111/dar.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richards-Jones L, Patel P, Jagpal PK, et al. Provision of drug and alcohol services amidst COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative evaluation on the experiences of service providers. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023;45:1098–106. doi: 10.1007/s11096-023-01557-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soderstrom CA, Smith GS, Dischinger PC, et al. Psychoactive substance use disorders among seriously injured trauma center patients. JAMA. 1997;277:1769–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu L-T, Swartz MS, Wu Z, et al. Alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in emergency department settings in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, et al. The Prevalence and Detection of Substance Use Disorders among Inpatients Ages 18 to 49: An Opportunity for Prevention. Prev Med. 1998;27:101–10. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colon-Berezin C, Nolan ML, Blachman-Forshay J, et al. Overdose Deaths Involving Fentanyl and Fentanyl Analogs - New York City, 2000-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2019;68:37–40. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6802a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl Law Enforcement Submissions and Increases in Synthetic Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - 27 States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2016;65:837–43. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jalal H, Buchanich JM, Roberts MS, et al. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science. 2018;361:eaau1184. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pytell JD, Sklar MD, Carrese J, et al. “I’m a Survivor”: Perceptions of Chronic Disease and Survivorship Among Individuals in Long-Term Remission from Opioid Use Disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06925-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vigilant LG. “I Don’t Have Another Run Left With It”: Ontological Security in Illness Narratives of Recovering on Methadone Maintenance. Deviant Behav. 2005;26:399–416. doi: 10.1080/016396290931650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]