Abstract

In the process of cardiac fibrosis, the balance between the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway and Wnt inhibitory factor genes plays an important role. Secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sFRP3), a Wnt inhibitory factor, has been linked to epigenetic mechanisms. However, the underlying role of epigenetic regulation of sFRP3, which is crucial in fibroblast proliferation and migration, in cardiac fibrosis have not been elucidated. Therefore, we aimed to investigate epigenetic and transcription of sFRP3 in cardiac fibrosis. Using clinical samples and animal models, we investigated the role of sFRP3 promoter methylation in potentially enhancing cardiac fibrosis. We also attempted to characterize the underlying mechanisms using an isoprenaline-induced cardiac fibrosis mouse model and cultured primary cardiac fibroblasts. Hypermethylation of sFRP3 was associated with perpetuation of fibroblast activation and cardiac fibrosis. Additionally, mitochondrial fission, regulated by the Drp1 protein, was found to be significantly altered in fibrotic hearts, contributing to fibroblast proliferation and cardiac fibrosis. Epigenetic modification of sFRP3 promoter methylation also influenced mitochondrial dynamics, linking sFRP3 repression to excessive mitochondrial fission. Moreover, sFRP3 hypermethylation was mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) in cardiac fibrosis and fibroblasts, and DNMT3A knockdown demethylated the sFRP3 promoter, rescued sFRP3 loss, and ameliorated the isoprenaline-induced cardiac fibrosis and cardiac fibroblast proliferation, migration and mitochondrial fission. Mechanistically, DNMT3A was shown to epigenetically repress sFRP3 expression via promoter methylation. We describe a novel epigenetic mechanism wherein DNMT3A represses sFRP3 through promoter methylation, which is a critical mediator of cardiac fibrosis and mitochondrial fission. Our findings provide new insights for the development of preventive measures for cardiac fibrosis.

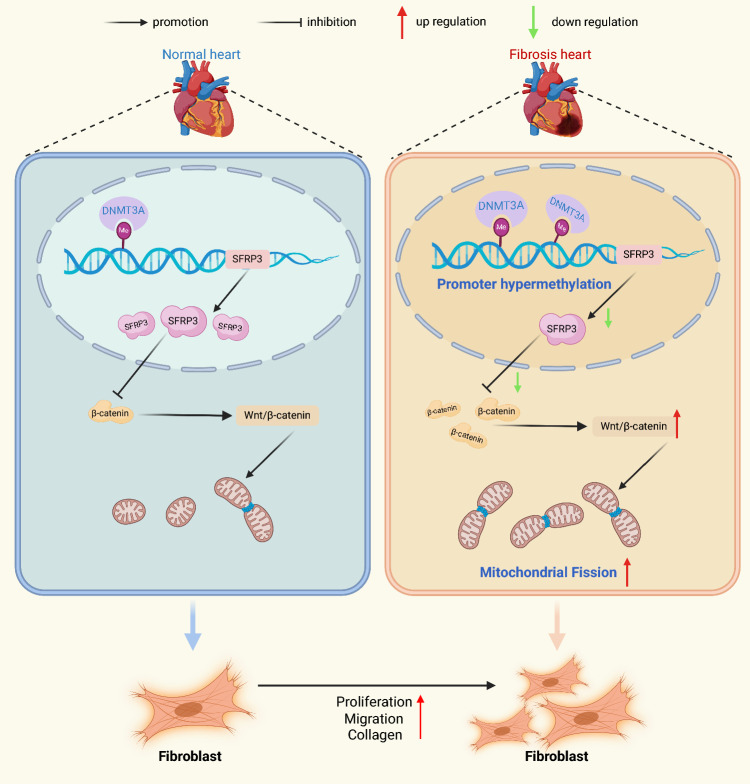

Graphical Abstract

DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A causes upregulation of sFRP3 methylation levels in cardiac fibrosis and cardiac fibroblasts. Subsequently, sFRP3 downregulation promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation, migration and mitochondrial fission. DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A repressed sFRP3 to facilitate cardiac fibroblast activation and cardiac fibrosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-024-05516-5.

Keywords: Cardiac fibrosis, Cardiac fibroblast, DNMT3A, SFRP3, Proliferation, Migration, Mitochondrial fission

Introduction

Cardiac fibrosis is a chronic and progressive interstitial heart disease [1, 2]. This process is characterized by the net accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins [3, 4]. The differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts is regarded as a pivotal event in the pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis [5–7], and cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration play key roles in cardiac fibrosis [8]. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is extensively involved in fibrosis as a profibrotic cytokine [9, 10]. Increased expression of α-smooth muscle actin and periostin (POSTN) is widely used as a marker of the fibroblast activation phenotype [11, 12]. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of cardiac fibrosis and the activation phenotype of cardiac fibroblasts are complex and the available evidence is inconclusive [13, 14].

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays an important role in heart physiology and pathology by regulating a variety of crucial cellular events [15], including differentiation [16], proliferation [17], and migration [18]. Interestingly enough, Epigenetic changes are also involved in the aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer cells [19]. The secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (sFRP3) is generally thought to inhibit Wnt signaling in several cancers [19, 20].

Recent studies have shown that secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRPs) are often downregulated via promoter hypermethylation in cancer cell lines and cancer tissues [21]. Notably, sFRP3 plays a crucial role in fibroblast proliferation and migration. Similar to cancer cells, fibroblast dysfunction have been regulated by DNA methylation. However, no reports have described the role of promoter methylation of sFRP3 in cardiac fibrosis. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the levels of methylation and transcription of sFRP3 in cardiac fibrosis based on the hypothesis that CpG island methylation of the sFRP3 promoter plays an important role in regulating sFRP3 expression in cardiac fibrosis.

The study can enhance our understanding on cardiac fibrosis for the development of appropriate preventive measures.

Materials and methods

All experimental materials and methods related to this article are described in detail in the Supplementary Material.

Results

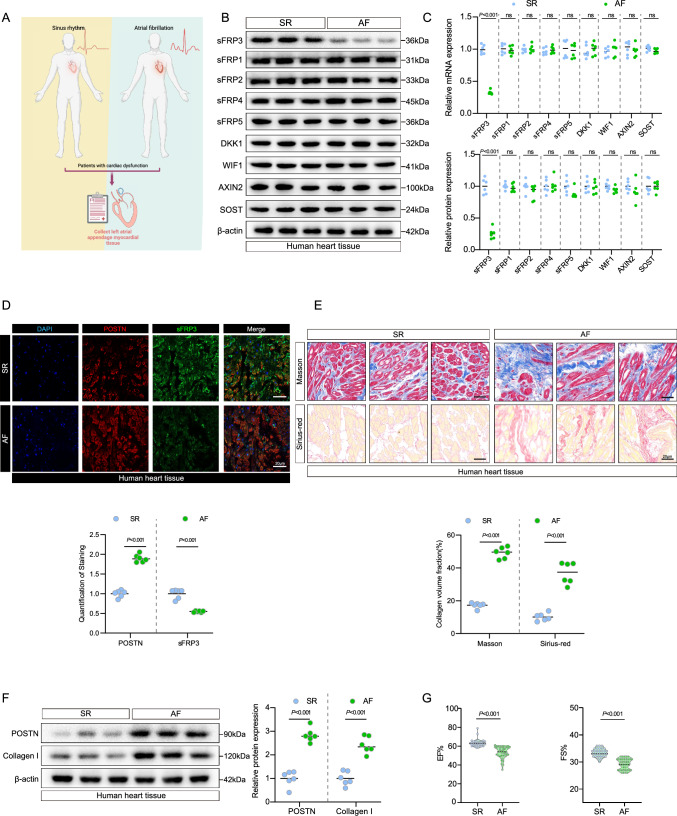

sFRP3 expression is decreased during fibrosis phenotype development in human patients with AF

Wnt signaling is a well-known molecular pathway involved in cardiovascular and fibrosis-related pathogenesis, and Wnt pathway activity is determined by Wnt pathway inhibitors [22]. To evaluate the changes in the expression of Wnt inhibitory factor genes in human AF heart tissues, we first analyzed the expression of Wnt inhibitors in the fibrotic hearts of patients with AF. The protein and mRNA levels of sFRP3 were decreased in AF fibrotic hearts (Fig. 1B, C and Supplementary Fig. S1A), while no changes were observed in the expression of other Wnt inhibitors, including sFRP1, sFRP2, sFRP4, sFRP5, DKK1, WIF1, AXIN2 and SOST (Fig. 1B, C and Supplementary Fig. S1A). This result suggested that sFRP3 was associated with the onset of AF. By co-staining for sFRP3 with the fibroblast marker POSTN and cardiomyocyte marker cTnT, we observed reduced staining for sFRP3 in the fibroblasts, but not cardiomyocyte, in the fibrotic heart (Fig. 1D and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S1B, C).

Fig. 1.

sFRP3 expression is decreased during fibrosis phenotype development in human patients with AF. A Schematic representation of the experimental design. B The expression of SFRP3, SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, SFRP5, DKK1, WIF1, AXIN2 and STOT in AF or SR patient heart tissues were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. C The expression of SFRP3, SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, SFRP5, DKK1, WIF1, AXIN2 and STOT in AF or SR patient heart tissues were analyzed by RT-qPCR for indicated mRNA levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. D Hearts tissues from AF or SR patient were embedded in paraffin, and tissue sections were evaluated by Immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence assays were performed to evaluate SFRP3 and POSTN expression in human heart tissue, Nuclei were stained with DAPI (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. E Hearts tissues from AF or SR patient were embedded in paraffin, and tissue sections were evaluated by Masson's trichrome staining (n = 6) and Sirius red staining (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. F The expression of POSTN and type I collagen in AF or SR patient heart tissues were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. G Cardiac function evaluated by echocardiography on AF or SR patient, P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

Next, we validated fibrosis by detecting the expression of protein and mRNA markers of fibrosis and histopathology. Masson trichrome and Sirius red staining were used to identify areas of severe collagen deposition in the heart tissue of patients with AF in comparison with healthy controls (Fig. 1E and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S1D). Consistent with the histopathological findings, POSTN and collagen I protein expression were significantly increased in patients with AF (Fig. 1F and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S1E). Additionally, the protein expression levels of WNT1 and β-catenin were also shown to be elevated in the AF group (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S1F). More importantly, Western blotting assays indicated that sFRP3 protein expression was decreased in the heart tissue of patients with AF (Fig. 1B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S1A).

We also monitored changes in heart function in patients with AF (Fig. 1G). Strikingly, echocardiography indicated impaired cardiac function; the ejection fraction and fractional shortening were significantly lower than those in healthy controls (Fig. 1G), indicating that the cardiac function of patients with AF was decompensated. Moreover, we found that the expression of sFRP3 was positively correlated with the ejection fraction and fractional shortening in patients (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S1G). Collectively, these findings suggest that increased cardiac fibrosis and impaired cardiac function are associated with sFRP3 suppression and that sFRP3 suppression is accompanied by a fibrosis phenotype in patients with AF.

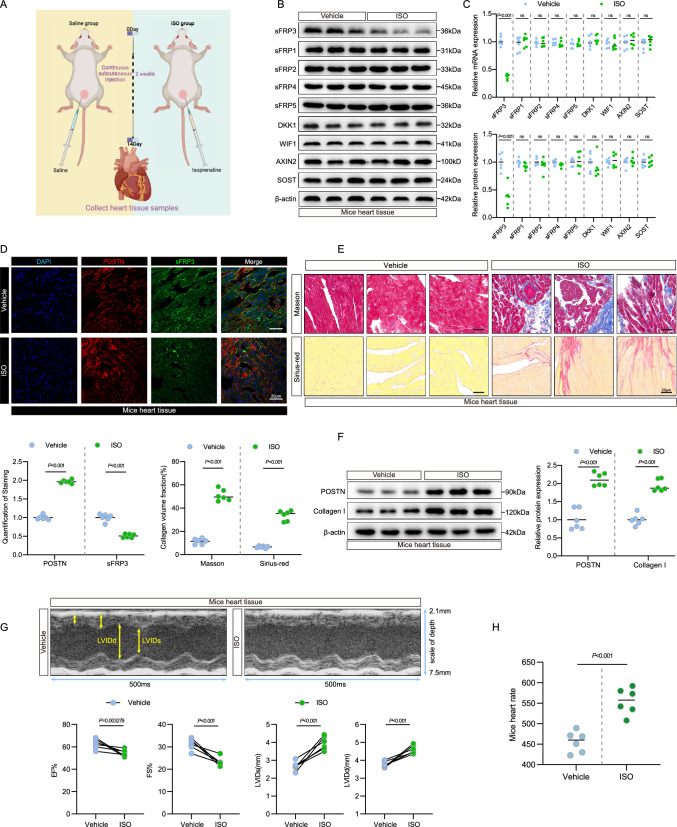

sFRP3 downregulation is accompanied by the fibrosis phenotype in experimental cardiac fibrosis mouse model

In a mouse model of isoprenaline (ISO)-induced cardiac fibrosis [22] (Fig. 2A), we first analyzed the expression of Wnt inhibitors. The mRNA and protein levels of sFRP3 were decreased in mouse tissues showing ISO-induced cardiac fibrosis (Fig. 2B, C and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2A), while sFRP1, sFRP2, sFRP4, sFRP5, DKK1, WIF1, AXIN2 and SOST expressions showed no changes in ISO-induced mouse cardiac fibrosis tissue (Fig. 2B, C and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2A), indicating that sFRP3 plays a crucial role in experimental cardiac fibrosis. Next, we observed reduced staining for sFRP3 in the fibroblasts in the fibrotic heart by co-staining for sFRP3 and the fibroblast marker POSTN (Fig. 2D and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2B). However, we did not observe reduced staining for sFRP3 in the cardiomyocytes in the fibrotic heart upon co-staining for sFRP3 and the cardiomyocyte marker cTnT (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2C), indicating sFRP3-specific dysregulation of fibroblasts.

Fig. 2.

sFRP3 downregulation is accompanied by the fibrosis phenotype in experimental cardiac fibrosis mouse model. A Schematic representation of the experimental design. B The expression levels of sFRP3, sFRP1, sFRP2, sFRP4, sFRP5, DKK1, WIF1, AXIN2, and SOST in ISO-induced experimental cardiac fibrosis tissues were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated proteins (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. C The expression levels of sFRP3, sFRP1, sFRP2, sFRP4, sFRP5, DKK1, WIF1, AXIN2, and SOST in ISO-induced experimental cardiac fibrosis tissues were analyzed by RT-qPCR for the indicated mRNAs (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. D Heart tissues from ISO-induced experimental models were embedded in paraffin, and tissue sections were evaluated by immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence assays were performed to evaluate sFRP3 and POSTN expression in mice heart tissue, Nuclei were stained with DAPI (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. E Heart tissues from ISO-induced experimental models were embedded in paraffin, and tissue sections were evaluated by Masson's trichrome staining (n = 6) and Sirius red staining (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. F The expression of POSTN and type I collagen in ISO-induced experimental cardiac fibrosis tissues were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. G Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on mice with ISO-induced experimental cardiac fibrosis to assess cardiac function (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. H Basal heart rate on mice with ISO-induced experimental cardiac fibrosis to assess heart rate level (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

Next, we validated fibrosis by detecting the expression of protein and mRNA markers of fibrosis and by histopathological assessments. In addition, Masson trichrome staining and Sirius red staining were used to identify areas of collagen deposition that were severe and extensive in ISO-induced mouse cardiac fibrosis tissue, but not in the vehicle control (Fig. 2E and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2D). Consistent with the histopathological findings, POSTN and collagen I protein expression were significantly increased in ISO-induced mouse cardiac fibrosis tissue (Fig. 2F and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2E). Additionally, the protein expression levels of WNT1 and β-catenin were also shown to be elevated in the ISO group (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2F). More importantly, sFRP3 protein expression decreased in the heart tissue of ISO-treated mice (Fig. 2B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2A), consistent with the immunoblot assays.

We also monitored changes in heart function in ISO-induced mice (Fig. 2G, H). Strikingly, echocardiography indicated impaired cardiac function; the ejection fraction and fractional shortening were significantly lower than those in the vehicle control (Fig. 2G), indicating that the cardiac function of ISO-induced mice was decompensated[23]. Moreover, we found that the expression of sFRP3 was positively correlated with the ejection fraction and fractional shortening in mice (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S2G). Taken together, these results suggest that increased cardiac fibrosis and impaired cardiac function are associated with sFRP3 suppression in patients with AF and that sFRP3 was suppressed and accompanied by a fibrotic phenotype in experimental cardiac fibrosis.

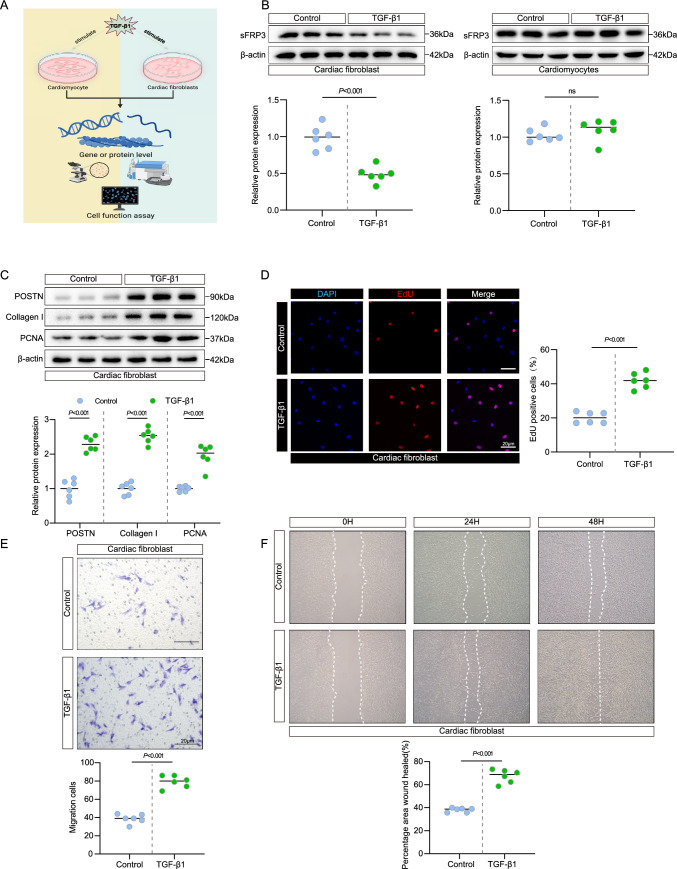

sFRP3 expression was decreased in activated cardiac fibroblasts but not in cardiomyocytes

Given the consistent downregulation of sFRP3 expression in patients with cardiac fibrosis as well as in the experimental cardiac fibrosis model and that fact that TGF-β1 enhances fibroblast phenoconversion [24] and increases the secretion of extracellular matrix proteins [25], we hypothesized that the core factors of fibrosis, such as TGF-β1 [9, 10], may regulate sFRP3 expression. Stimulation of cultured cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes with TGF-β1 (Fig. 3A) and long-term evaluation showed that the mRNA and protein levels of sFRP3 decline strongly below the baseline levels in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 3B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3A, B) but not in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3A, B). The in vivo results indicated that the downregulation of sFRP3 expression remained stably suppressed when cardiac fibroblasts were exposed to TGF-β1, similar to the findings in the human and mice fibrotic heart tissues (Fig. 1B, C and Fig. 2B, C). These results demonstrated that the expression of sFRP3 is downregulated in cardiac fibroblasts in a TGF-β1-dependent manner.

Fig. 3.

sFRP3 expression was decreased in activated cardiac fibroblasts but not in cardiomyocytes. A Schematic representation of the experimental design. B The expression of SFRP3 in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. C The expression of POSTN, type I collagen and PCNA in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. D EdU assay to detect TGF-β1 induced the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. E Transwell migration assay detect TGF-β1 induced the migration ability of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. F The scratch assay was performed to test TGF-β1 induced the migration ability of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

More importantly, TGF-β1 treatment led to an increase in the expression of the key fibrosis markers POSTN and collagen I in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 3C and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3C, D). Since TGF-β1 treatment led to cardiac fibroblast proliferation [26] and migration [27], we found that the expression of the proliferation marker PCNA was significantly increased in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts in comparison with the control (Fig. 3C and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3C, D). Moreover, the cell proliferation rate was greater in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts than in the control, as determined by the EdU and CCK8 assays (Fig. 3D and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3E, F). Furthermore, the cell migration activity in the TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts was greater than that in the control, as determined by the Transwell and wound-healing assays (Fig. 3E, F and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3G, H). These results suggest that sFRP3 expression was decreased in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts.

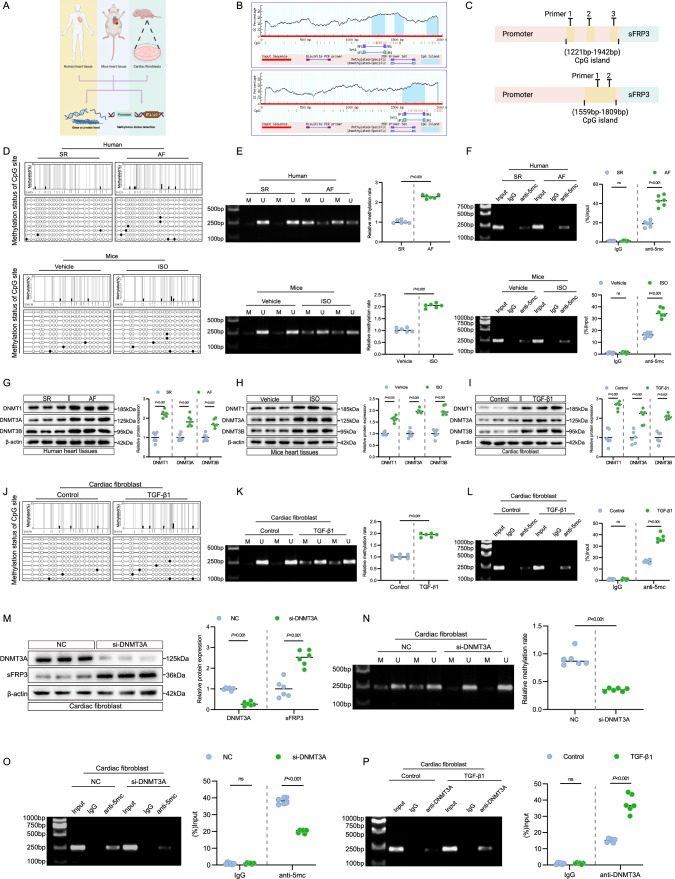

sFRP3 promoter hypermethylation is accompanied by DNA methyltransferase alterations in vivo and vitro

A persistent downregulation of sFRP3 expression in the fibrotic heart and repression of sFRP3 expression upon stimulation of cardiac fibroblasts with TGF-β1 was observed (Fig. 4A). Loss by epigenetic silencing of Wnt inhibitors such as sFRP family members is more frequent [28], and has been associated with human breast carcinoma. We hypothesized that DNA methylation account for the repressed expression of sFRP3. To evaluate whether DNA methylation is implicated in the downregulation of sFRP3 expression in fibrotic hearts and cultured cardiac fibroblasts, we analyzed the sFRP3 promoter using MethPrimer (urogene.org). Both the human and murine sFRP3 promoters were characterized by typical CpG islands located in the − 1221 bp/1369 bp, − 1475 bp/1576 bp, − 1830 bp/1942 bp (human), and − 1559/1809 bp regions (murine) (Fig. 4B and C). Next, we examined the DNA methylation status of the sFRP3 promoter using BSP and MSP. Fibrotic heart samples from patients with AF and mice exhibited greater sFRP3 promoter methylation than healthy controls (Fig. 4D, E and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4H). More importantly, the MeDIP assay revealed that fibrotic heart samples from patients with AF and mice exhibited increased methylation of the sFRP3 promoter (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

sFRP3 promoter hypermethylation is accompanied by DNA methyltransferase alterations in vivo and vitro. A Schematic representation of the experimental design. B The SFRP3 promoter by the online software MethPrimer (urogene.org/methprimer). Human SFRP3 gene promoters are characterized by typical CpG islands (human). Murine SFRP3 gene promoters are characterized by typical CpG islands-(murine). C Diagram of SFRP3 promoter primer design for ChIP and MeDIP assay. D The human and mice heart DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by BSP assay (n = 3). E The human and mice heart DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MSP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. F The human and mice heart DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MeDIP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. G The expression of DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B in AF or SR patient heart tissues were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. H The expression of DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B in ISO induced experimental cardiac fibrosis tissues were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. I The expression of DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. J THE TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by BSP assay (n = 3). K The TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MSP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. L The TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MeDIP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. M The expression of DNMT3A and SFRP3 in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts treatment with siRNA-DNMT3A were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. N The TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts treatment with siRNA-DNMT3A and the DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MSP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. O The TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts treatment with siRNA-DNMT3A and the DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MeDIP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. P DNMT3A binds to the SFRP3 promoter in cardiac fibroblasts. ChIP products were amplified by PCR. The ChIP assay revealed that DNMT3A could bind to the SFRP3 promoter (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t-test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

Subsequently, to identify the potential upstream inducers of hypermethylation, we examined the major DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and found that fibrotic heart DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B were all upregulated in both patients with AF and in mice (Fig. 4G, H and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4A, B), and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of the mouse heart and AF patient sections confirmed these elevations (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4C). Taken together, these results suggest that sFRP3 suppression in the hearts of both patients and mice was likely due to aberrant DNMT1/3A/3B elevation and the consequent sFRP3 promoter hypermethylation.

We further investigated whether TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts showed similar changes in sFRP3 hypermethylation. Consistent with the in vivo findings, the expression of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B markedly increased in these fibroblasts (Fig. 4I and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4D). We also examined the DNA methylation status of the sFRP3 promoter. Consistent with the previous findings, the samples from TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts exhibited increased sFRP3 promoter methylation in BSP and MSP (Fig. 4J, K). Strikingly, the MeDIP assay revealed increased methylation of the sFRP3 promoter in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 4L), indicating decreased sFRP3 expression in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts due to DNA hypermethylation.

Therefore, we speculated that DNMTs induced the silencing of sFRP3 in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts. To evaluate the specific role of DNMTs in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts, DNMTs were knocked down in cardiac fibroblasts (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4E). Interestingly, only DNMT3A knockdown increased sFRP3 expression (Fig. 4M), whereas no similar effect was observed in cardiomyocytes (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S3I). The subsequent MeDIP and MSP analysis confirmed that DNMT3A knockdown reduced hypermethylation of the sFRP3 promoter induced by TGF-β1 (Fig. 4N and O). In addition, 5-azadC, a DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor, reversed the DNA methylation-mediated repression of sFRP3 expression (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4F). More importantly, the enrichment of DNMT3A at the promoter region of sFRP3 loci was determined by ChIP-PCR analysis, and the results indicated increased enrichment of DNMT3A in the sFRP3 promoter in TGF-β1-treated cardiac fibroblasts and fibrotic heart samples from patients with AF (Fig. 4P and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S4G). These results suggest that the sFRP3 promoter is hypermethylated along with the elevation of DNMT3A expression in vivo and in vitro and that DNMT3A epigenetically represses sFRP3 expression via promoter methylation.

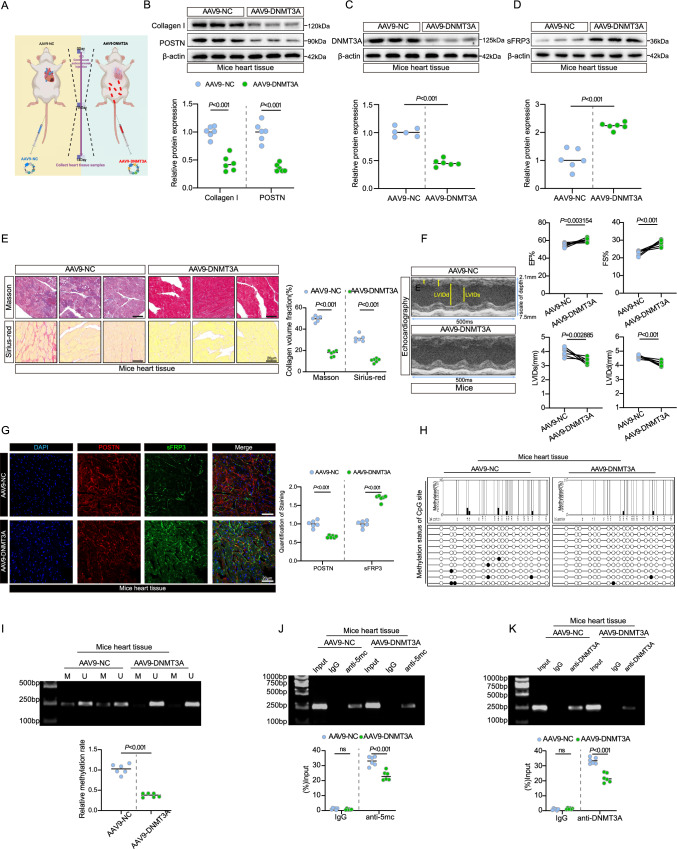

sFRP3 epigenetic derepression ameliorates experimental cardiac fibrosis

To determine the role of DNMT3A in experimental cardiac fibrosis, we subcutaneously injected mice with ISO-induced cardiac fibrosis by expressing shRNA-DNMT3A, mice were treated with AAV9-POSTN-shDNMT3A, an adeno-associated viruses to induce fibroblast-specific knockdown of DNMT3A and specially targeted cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 5A). Measurements of body weight, water intake, and food intake revealed no group differences (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5A-C). DNMT3A knockdown substantially reduced collagen I and POSTN levels (Fig. 5B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5D). DNMT3A expression significantly decreased in AAV9-DNMT3A mice after DNMT3A knockdown (Fig. 5C and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5E), according to immunofluorescence assays (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5I). Consistent with these findings, Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red staining showed a marked reduction in collagen deposition and fibrosis in AAV9-DNMT3A-treated mice (Fig. 5E and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5F). After AAV9-DNMT3A treatment, we observed improved cardiac function, as evaluated by echocardiography (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, sFRP3 levels were elevated in mice with cardiac fibrosis after DNMT3A knockdown (Fig. 5D and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5G), according to immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 5G and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5H). Furthermore, samples from AAV9-DNMT3A-treated mice exhibited decreased sFRP3 promoter methylation (Fig. 5H, I, and J), as detected by BSP, MSP, and MeDIP assays, indicating that DNMT3A knockdown inhibited sFRP3 promoter methylation in mice with cardiac fibrosis. More importantly, ChIP-PCR analysis to determine the enrichment of DNMT3A at the promoter region of sFRP3 loci indicated decreased enrichment of DNMT3A in the sFRP3 promoter in AAV9-DNMT3A-treated mice (Fig. 5K). These results suggest that DNMT3A silencing ameliorates ISO-induced cardiac fibrosis by decreasing sFRP3 promoter methylation and boosting sFRP3 expression. Additionally, to confirm the direct effect of sFRP3 on cardiac fibrosis and cardiac function in mice, we subcutaneously injected mice with ISO-induced cardiac fibrosis by expressing shRNA-sFRP3, mice were treated with AAV9-POSTN-sh-sFRP3, an adeno-associated viruses to induce fibroblast-specific knockdown of sFRP3 and specially targeted cardiac fibroblasts. Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red staining showed a marked increase in collagen deposition and fibrosis in AAV9-sFRP3-treated mice (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5J). Additionally, echocardiography indicated a more severe decline in cardiac function in the AAV9-sFRP3-treated mice (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5K). Besides, sFRP3 knockdown significantly increased collagen I, POSTN, WNT1 and β-catenin levels (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5L). Furthermore, an experiment using cardiac fibroblasts transfected with DNMT3A and/or sFRP3 siRNAs, which further substantiated the relationship between sFRP3 and DNMT3A (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5M).

Fig. 5.

sFRP3 epigenetic derepression ameliorates experimental cardiac fibrosis. A Schematic representation of the experimental design. B The expression of type I collagen and POSTN in ISO induced experimental treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. C The expression of DNMT3A in ISO induced experimental treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. D The expression of SFRP3 in ISO induced experimental treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. E Hearts tissues from ISO induced experimental treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A, the mice heart tissues were embedded in paraffin, and tissue sections were evaluated by Masson's trichrome staining (n = 6) and Sirius red staining (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. F Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on mice ISO induced experimental treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A to assess cardiac function (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. G Hearts tissues from ISO induced experimental treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A, the mice heart tissues were embedded in paraffin, and tissue sections were evaluated by Immunofluorescence staining. Immunofluorescence assays were performed to evaluate SFRP3 and POSTN expression in mice heart tissue, Nuclei were stained with DAPI (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. H ISO-induced mice treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A, the mice heart DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by BSP assay (n = 3). I ISO-induced mice treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A, the mice heart DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MSP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. J ISO-induced mice treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A, the mice heart DNA methylation status of SFRP3 promoters by MeDIP assay (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. K ISO-induced mice treatment with AAV9-DNMT3A, ChIP products were amplified by PCR. The ChIP assay revealed that DNMT3A could bind to the SFRP3 promoter (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

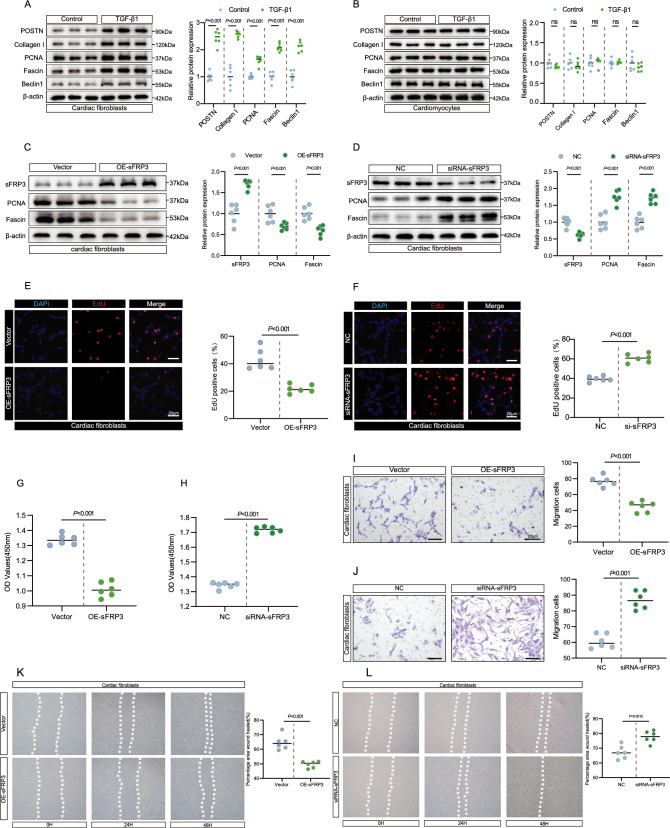

sFRP3 regulated cardiac fibroblasts proliferation and migration, while downregulation of DNMT3A rescues it

To further determine the function of sFRP3 in primary cells isolated from neonatal mice, we assessed the cellular function initially in primary cells that were differentiated with TGF-β1. TGF-β1 treatment led to an increase in the levels of the key fibrosis marker POSTN and collagen I in cardiac fibroblasts but not in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6A, B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S6A). Because TGF-β1 treatment led to cardiac fibroblast proliferation [29], migration [30], and autophagy [31], we found that the levels of the proliferation marker PCNA, the migration marker fascin, and the autophagy marker Beclin 1 were significantly increased in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts but not in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6A, B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S6A).

Fig. 6.

sFRP3 regulated cardiac fibroblasts proliferation and migration, while downregulation of DNMT3A rescues it. A The expression of POSTN, type I collagen, PCNA, Fascin and Beclin1 in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. B The expression of POSTN, type I collagen, PCNA, Fascin and Beclin1 in TGF-β1 induced cardiomyocytes were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P > 0.05 with Student’s t test. C The expression of sFRP3, PCNA and Fascin in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts treatment with sFRP3 overexpression were analyzed by western blotting for indicated protein levels (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. D The expressions of sFRP3, PCNA and Fascin in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated proteins (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. E EdU assay to detect the proliferation of TGF-β1 induced treatment with sFRP3 overexpression of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. F EdU assay to detect the proliferation of TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. G CCK-8 assay to detect TGF-β1 induced treatment with sFRP3 overexpression the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. H CCK-8 assay to detect TGF-β1 induced treatment with siRNA-sFRP3 the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. I Transwell migration assay detect TGF-β1 induced treatment with sFRP3 overexpression the migration ability of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. J Transwell migration assay to detect the migration ability TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. K The scratch assay was performed to test TGF-β1 induced treatment with sFRP3 overexpression the migration ability of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. L The scratch assay was performed to test TGF-β1 induced treatment with siRNA-sFRP3 the migration ability of cardiac fibroblasts (n = 6), P = 0.0015 with Student’s t test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

Next, we explored whether sFRP3 is capable of regulating cardiac fibroblast function and the underlying mechanisms. We observed that sFRP3 overexpression significantly decreased the production of the proliferation marker PCNA and the migration marker fascin, whereas sFRP3 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect, but did not affect Beclin 1 levels (Fig. 6C, D and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S6B,C,D). These data suggest that sFRP3 is a critical regulator of TGF-β1-induced proliferation and migration of cardiac fibroblasts. Furthermore, we found that cardiac fibroblast proliferation was inhibited in the sFRP3-overexpression group than in the vector group, as determined by the EdU and CCK8 assays, sFRP3 knockdown had the opposite effect (Fig. 6E, F, G, H). Consistent with this observation, cardiac fibroblast migration activity was inhibited in the sFRP3-overexpression group than in the vector group, whereas sFRP3 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect, as determined by the Transwell assay (Fig. 6I, J) and wound-healing assay (Fig. 6K, L). However, the level of cell autophagy was not altered by sFRP3 overexpression in cardiac fibroblasts, as determined by the Acridine Orange assay (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6E). These results suggested that overexpression of sFRP3 inhibited cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration, whereas sFRP3 knockdown promoted these.

Indeed, our findings also demonstrated that the sFRP3 promoter is hypermethylated along with DNMT3A in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts and the fibrotic heart (Fig. 4I, J, K, L). Additionally, sFRP3 expression in the mice with cardiac fibrosis was significantly increased by DNMT3A knockdown (Fig. 5D and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S5G). To elucidate the role of DNMT3A in controlling sFRP3 expression during cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration, we first targeted the expression of sFRP3 in cardiac fibroblasts. siRNA-mediated knockdown of sFRP3 in cardiac fibroblasts increased the mRNA levels of collagen I and promoted the expression of the proliferation marker POSTN and the migration marker fascin (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6F, G). Next, we investigated whether DNMT3A knockdown could rescue the effects of sFRP3 knockdown on cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration. To test this hypothesis, we measured the proliferation rate and migration of cardiac fibroblasts transfected with DNMT3A and/or sFRP3 siRNAs. Knockdown of DNMT3A significantly counteracted the effects of elevated sFRP3 knockdown on the cardiac fibroblast proliferation marker POSTN (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6H) and the migration marker fascin (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6H). Moreover, consistent with the decreased levels of proliferation and migration markers, DNMT3A knockdown significantly counteracted the effects of elevated sFRP3 knockdown on cardiac fibroblast migration (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6I) and proliferation rates (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6J). Indeed, DNMT3A knockdown was shown to remarkably reduce the proliferation rate and migration activity of cardiac fibroblasts and decrease the expressions of Wnt1, β-catenin, POSTN, and fascin (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6K, L, M). In contrast, DNMT3A overexpression inhibited sFRP3 expression, significantly enhanced the proliferation rate and migration activity of cardiac fibroblasts, and increased the expression of Wnt1, β-catenin, POSTN, and fascin (Supplementary material online, Fig. S6N, O, P). Taken together, these results suggest that sFRP3 knockdown promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration, whereas DNMT3A inactivation prevents this process.

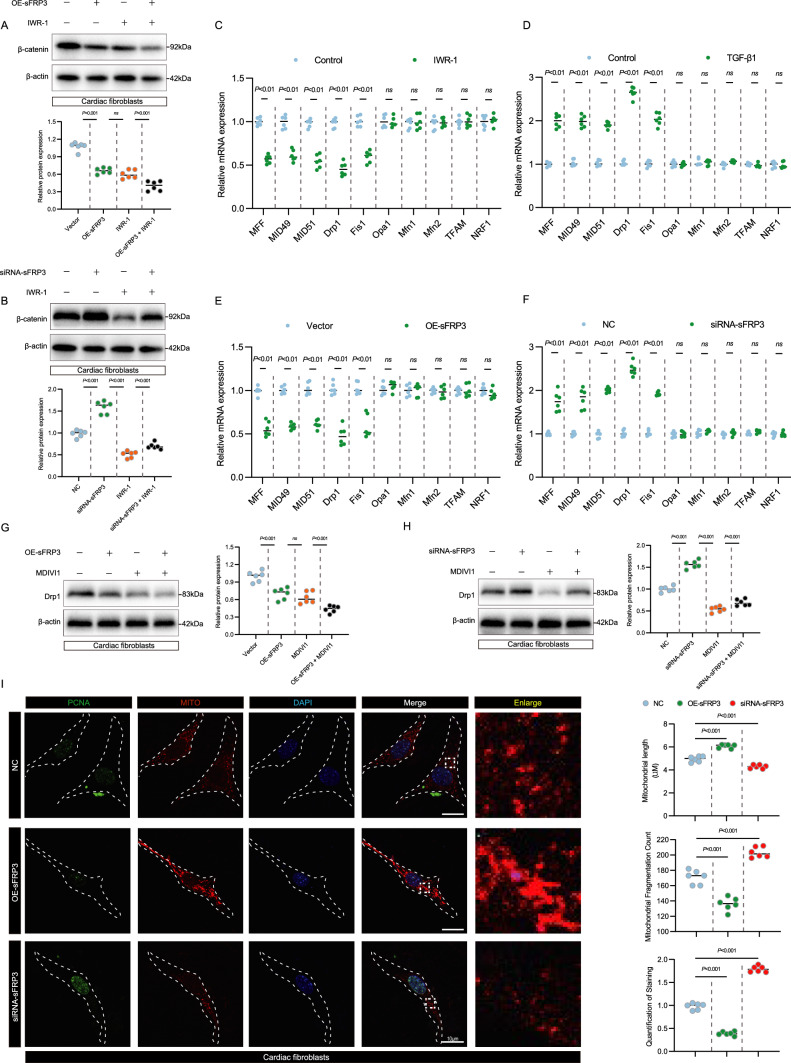

sFRP3 controls cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration is required for mitochondrial fission

Because Wnt/β-catenin axis is strongly related to mitochondrial dynamics. We hypothesized that sFRP3 controls cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration was necessary for mitochondrial dynamics, including mitochondrial fission, fusion, and biogenesis. To test this hypothesis, first, since sFRP3 is an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, we investigated the possible correlation between sFRP3 and β-catenin in cardiac fibroblasts, which demonstrated that over expression of sFRP3 reduces the β-catenin expression, while Wnt1 IWR-1 inhibitor promotes it, whereas sFRP3 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect (Fig. 7A, B and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S7A, C). To confirm the pathway is correctly depicted, a Western blot analysis for AXIN was employed (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S7B, D). These results suggest that knockdown of sFRP3 promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration by targeting β-catenin. Next, we used RT-qPCR and western blotting to screen various markers related to mitochondrial fission, fusion, and biogenesis in cardiac fibroblast treatment with Wnt inhibitor IWR-1. Interestingly, we observed decreased levels of mitochondrial fission markers (Drp1 and Fis1) in cardiac fibroblast treatment with Wnt inhibitor IWR-1(Fig. 7C). Moreover, we observed increased levels of mitochondrial fission markers (Drp1 and Fis1) in TGF- β1 induced cardiac fibroblast (Fig. 7D). The levels of mitochondrial fusion markers (MFN1 and MFN2) and biogenesis markers (TFAM and NRF1) were slightly, but not significantly, altered in TGF- β1-induced cardiac fibroblast (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

sFRP3 controls cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration is required for mitochondrial fission. A The expressions of β-catenin in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with sFRP3 overexpression and IWR-1 were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated proteins (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. B The expressions of β-catenin in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 and IWR-1 were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated proteins (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. C The expression levels of MFF, MID49, MID51, Drp1, Fis1, Opa1, Mfn1, Mfn2, TFAM and NRF1 in IWR-1 induced cardiac fibroblasts were analyzed by RT-qPCR for the indicated mRNAs (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. D The expression levels of MFF, MID49, MID51, Drp1, Fis1, Opa1, Mfn1, Mfn2, TFAM and NRF1 in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts were analyzed by RT-qPCR for the indicated mRNAs (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. E The expression levels of MFF, MID49, MID51, Drp1, Fis1, Opa1, Mfn1, Mfn2, TFAM and NRF1 in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with sFRP3 overexpression were analyzed by RT-qPCR for the indicated mRNAs (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. F The expression levels of MFF, MID49, MID51, Drp1, Fis1, Opa1, Mfn1, Mfn2, TFAM and NRF1 in TGF-β1 induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 were analyzed by RT-qPCR for the indicated mRNAs (n = 6), P value with Student’s t test. G The expressions of Drp1 in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with sFRP3 overexpression and MDIVI1 were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated proteins (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. H The expressions of Drp1 in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 and MDIVI1 were analyzed by western blotting for the indicated proteins (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. I Cardiac fibroblasts treated with siRNA-sFRP3 and sFRP3 overexpression after TGF-β1-induced were co-stained with mitotracker and PCNA. Measure mitochondrial length, mitochondrial fragmentation and the PCNA expression of different groups (n = 6), P ≤ 0.001 with Student’s t test. “ns” indicates findings that were not significant (P > 0.05). The “n” in the figure legends indicates the number of biological replicates

We further investigated whether the sFRP3 controls cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration was necessary for mitochondrial fission in TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts, we targeted the expression of sFRP3 in cardiac fibroblasts, overexpression of sFRP3 in cardiac fibroblasts decreased the mRNA levels of mitochondrial fission markers (Drp1 and Fis1), whereas sFRP3 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect (Fig. 7E, F). Consistent with this observation, over expression of sFRP3 reduces the Drp1 expression, while Drp1 inhibitor MDIVI1 promotes it; whereas sFRP3 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect (Fig. 7G, H and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S7E, G). Besides, by assessed the GTPase activity of Drp1, similar results were observed (see Supplementary material online, Fig. S7F, H). Consistent with the above findings, through co-staining for Mito-tracker red and the fibroblast proliferation marker PCNA, we observed decrease in staining for the PCNA protein and inhibit mitochondrial fission in fibroblasts trartment with sFRP3 over expression, whereas sFRP3 knockdown resulted in the opposite effect (Fig. 7I and see Supplementary material online, Fig. S7E). Taken together, these results suggest that sFRP3 controls cardiac fibroblast proliferation and migration is required for mitochondrial fission.

Discussion

Our central finding is that decreased sFRP3 expression with DNMT3A upregulation was accompanied by proliferation and migration of cardiac fibroblasts in an experimental cardiac fibrosis model and patients with AF. By adopting a comprehensive approach, we found that the demethylating agent 5-azadC normalized the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts in vitro. To gain insights into the possible inhibitors of Wnt genes that are affected by hypermethylation in fibrotic fibroblasts [32, 33], we screened and identified nine genes that are selectively expressed in human and mouse fibrotic hearts. Among these inhibitors of Wnt genes, we focused on sFRP3. In this study, we used evidence and mechanistic explanations from cultured cells, animal models, and clinical samples to show that sFRP3 repression due to aberrant DNMT3A elevation and the subsequent sFRP3 promoter hypermethylation are important epigenetic hallmarks of cardiac fibrosis (Graphical Abstract).

Our results are supported by several other findings. First, DNMT3A expression has been shown to be markedly increased and sFRP3 expression is significantly decreased in human and mouse fibrotic heart tissues. Consistent with this finding, our results further revealed that sFRP3 promoter hypermethylation associated with fibrosis is mediated by the DNMT3A and that pathological hypermethylation by DNMT3A can be induced by long-term exposure to the profibrotic growth factor TGF-β1. Interestingly, we provided evidence that epigenetic sFRP3 silencing causes fibroblast proliferation, migration, and fibrosis, similar to the proliferation of cancer cells, in a growth factor-independent manner upon sFRP3 silencing.

Second, on the basis of these findings, silencing of DNMT3A was shown to ameliorate experimental cardiac fibrosis, suppress collagen deposition, and inhibit fibroblast proliferation and migration activity. Furthermore, mechanistically, knockdown of DNMT3A decreased the enrichment of DNMT3A in the sFRP3 promoter and promoted sFRP3 expression in fibrotic hearts and TGF-β1-induced cardiac fibroblasts. Together, these results suggest that sFRP3 hypermethylation correlates strongly with fibrosis and in vitro sFRP3 methylation correlates with TGF-β1-induced proliferation and migration of cardiac fibroblasts.

Third, our study emphasize the role of the Wnt/β-catenin axis as a potential therapeutic target for cardiac fibrosis, confirming the results of previous studies that suggested a prominent role of Wnt signaling in cardiac fibrosis[34–37]. Interestingly, increased Wnt signaling within the fibrotic microenvironment is attributable to autocrine and paracrine growth factor stimulation [38–40]. Our results indicate a new mechanism of epigenetic sFRP3 silencing that caused increased Wnt/β-catenin signal pathway activation in the fibrotic heart and cardiac fibroblasts exposed to TGF-β1. Strikingly, knockdown of sFRP3 promotes cardiac fibroblast proliferation, migration and mitochondrial fission, whereas inactivation of DNMT3A rescues it. These results suggest that the anti-fibrotic capacity of Wnt inhibitors should be further explored.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to show that sFRP3 hypermethylation perpetuates cardiac fibroblast proliferation, migration, mitochondrial fission and fibrosis. Thus, the findings corroborate the fact that specific genes contribute to cardiac fibrosis [41]. Further studies are required to elucidate the utility of methylated genes as diagnostic markers for predicting cardiac fibrosis and the possible therapeutic efficacy of methylation inhibitors in the progression of cardiac fibrosis. However, the focus of this study is the myocardial remodeling and fibrosis induced by atrial fibrillation. Focuses on exploring the role of cardiac fibroblasts in the process of cardiac fibrosis and its molecular mechanisms. This study does have limitations and does not delve into the electrophysiological changes associated with atrial fibrillation.

Conclusions

Our results found a novel mechanism by which decreased sFRP3 expression with DNMT3A upregulation was accompanied by proliferation, migration and mitochondrial fission of cardiac fibroblast.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170236, 81700212), Key research and development projects of Anhui Province (202104j07020037), Excellent Youth Research Project in University of Anhui Province (2023AH030116), Translational medicine research project of Anhui Province (2021zhyx-C61), Excellent Top Talents Program of Anhui Province Universities (gxyqZD2022023), Key Project of Natural Science Foundation in Anhui Provincial (KJ2021A0313) and National Natural Science Foundation Incubation Program of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (2020GMFY02).

Abbreviations

- AF

Atrial fibrillation

- BSP

Bisulfite-assisted polymerase chain reaction

- CCK8

Cell counting kit-8

- CF

Cardiac fibrosis

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- DNMT3A

DNA methyltransferase 3A

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- ISO

Isoprenaline

- MeDIP

Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation

- MSP

Methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction

- POSTN

Periostin

- sFRP

Secreted frizzled-related protein

- sFRP3

Secreted frizzled-related protein 3

- SR

Sinus rhythm

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-β1

- WIF1

Wnt inhibitory factor-1

Authors contributions

Hui Tao, Jian-Yuan Zhao, Wei Cao designed the study. Hui Tao and Jian-Yuan Zhao reviewed the manuscript. Li-Chan Lin, Zhi-Yan Liu, Bin Tu and Shun-Xiang Jiang performed molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation experiments. Kai Song and Shun-Xiang Jiang performed the animal and cell experiments. Bin Tu, Ze-Yu Zhou analyzed and interpreted data. Hui Tao and Jian-Yuan Zhao helped revise the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

All animal research programs have been approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of Anhui Medical University.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to its publication in Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shun-Xiang Jiang, Ze-Yu Zhou, Bin Tu and Kai Song contribute equally to the first author.

Contributor Information

Wei Cao, Email: 13514964858@qq.com.

Jian-Yuan Zhao, Email: zhaojy@vip.163.com.

Hui Tao, Email: taohui@ahmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Frangogiannis NG (2021) Cardiac fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res 117:1450–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travers JG, Tharp CA, Rubino M, McKinsey TA (2022) Therapeutic targets for cardiac fibrosis: from old school to next-gen. The Journal of clinical investigation. 132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Kurose H (2021) Cardiac Fibrosis and Fibroblasts. Cells 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Travers JG, Kamal FA, Robbins J, Yutzey KE, Blaxall BC (2016) Cardiac fibrosis: the fibroblast awakens. Circ Res 118:1021–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall C, Gehmlich K, Denning C, Pavlovic D (2021) Complex relationship between cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes in health and disease. J Am Heart Assoc 10:e019338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hortells L, Johansen AKZ, Yutzey KE (2019) Cardiac Fibroblasts and the Extracellular Matrix in Regenerative and Nonregenerative Hearts. Journal of cardiovascular development and disease. 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Frangogiannis NG (2019) Cardiac fibrosis: cell biological mechanisms, molecular pathways and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Aspects Med 65:70–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frangogiannis NG (2019) The extracellular matrix in ischemic and nonischemic heart failure. Circ Res 125:117–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S, Ranjbarvaziri S, Lay FD, Zhao P, Miller MJ, Dhaliwal JS et al (2018) Genetic regulation of fibroblast activation and proliferation in cardiac fibrosis. Circulation 138:1224–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villalobos E, Criollo A, Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, French KM, May HI et al (2019) Fibroblast primary cilia are required for cardiac fibrosis. Circulation 139:2342–2357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J, Subbaiah KCV, Xie LH, Jiang F, Khor ES, Mickelsen D et al (2020) Glutamyl-Prolyl-tRNA synthetase regulates proline-rich pro-fibrotic protein synthesis during cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res 127:827–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiang FL, Fang M, Yutzey KE (2017) Loss of β-catenin in resident cardiac fibroblasts attenuates fibrosis induced by pressure overload in mice. Nat Commun 8:712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landry NM, Rattan SG, Filomeno KL, Meier TW, Meier SC, Foran SJ et al (2021) SKI activates the Hippo pathway via LIMD1 to inhibit cardiac fibroblast activation. Basic Res Cardiol 116:25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stratton MS, Bagchi RA, Felisbino MB, Hirsch RA, Smith HE, Riching AS et al (2019) Dynamic chromatin targeting of BRD4 stimulates cardiac fibroblast activation. Circ Res 125:662–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foulquier S, Daskalopoulos EP, Lluri G, Hermans KCM, Deb A, Blankesteijn WM (2018) WNT signaling in cardiac and vascular disease. Pharmacol Rev 70:68–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X et al (2013) Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc 8:162–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heallen T, Zhang M, Wang J, Bonilla-Claudio M, Klysik E, Johnson RL et al (2011) Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science (New York, NY) 332:458–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laeremans H, Rensen SS, Ottenheijm HC, Smits JF, Blankesteijn WM (2010) Wnt/frizzled signalling modulates the migration and differentiation of immortalized cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 87:514–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida GJ (2020) Regulation of heterogeneous cancer-associated fibroblasts: the molecular pathology of activated signaling pathways. J Exp Clin Cancer Res CR 39:112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kephart JJ, Tiller RG, Crose LE, Slemmons KK, Chen PH, Hinson AR et al (2015) Secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (SFRP3) is required for tumorigenesis of PAX3-FOXO1-positive alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 21:4868–4880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan H, Zhou F, Nie D, Chen Q, Cai X, Shan X et al (2014) Hepatitis C virus core protein epigenetically silences SFRP1 and enhances HCC aggressiveness by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 33:2826–2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Li Z, Ji H (2021) Direct targeting of β-catenin in the Wnt signaling pathway: current progress and perspectives. Med Res Rev 41:2109–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burke RM, Lighthouse JK, Mickelsen DM, Small EM (2019) Sacubitril/valsartan decreases cardiac fibrosis in left ventricle pressure overload by restoring PKG signaling in cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Heart Fail 12:e005565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan R, Yuan L, Li J, Wang J, Li Z, Cai Z, et al. (2022) Bone morphogenetic protein 4 inhibits pulmonary fibrosis by modulating cellular senescence and mitophagy in lung fibroblasts. Eur Respiratory J 60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wei P, Xie Y, Abel PW, Huang Y, Ma Q, Li L et al (2019) Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1-induced miR-133a inhibits myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Dis 10:670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen G, Xu H, Xu T, Ding W, Zhang G, Hua Y et al (2022) Calycosin reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac function in post-myocardial infarction mice by suppressing TGFBR1 signaling pathways. Phytomed Int J Phytoth Phytopharmacol 104:154277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng X, Wang L, Wen X, Gao L, Li G, Chang G et al (2021) TNAP is a novel regulator of cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction by mediating TGF-β/Smads and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. EBioMedicine 67:103370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhuvanalakshmi G, Arfuso F, Kumar AP, Dharmarajan A, Warrier S (2017) Epigenetic reprogramming converts human Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells into functional cardiomyocytes by differential regulation of Wnt mediators. Stem Cell Res Ther 8:185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Zhuang T, Pi J, Chen X, Zhang Q, Li Y et al (2019) Endothelial forkhead box transcription factor P1 regulates pathological cardiac remodeling through transforming growth factor-β1-endothelin-1 signal pathway. Circulation 140:665–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao L, Wang LY, Liu ZQ, Jiang D, Wu SY, Guo YQ et al (2020) TNAP inhibition attenuates cardiac fibrosis induced by myocardial infarction through deactivating TGF-β1/Smads and activating P53 signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis 11:44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan C, Zhang HF, Wang YJ, Chen ZT, Deng BQ, Qiu Q et al (2021) The downregulation of ADAM17 exerts protective effects against cardiac fibrosis by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitophagy. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021:5572088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Wang X (2020) Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol 13:165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sremac M, Paic F, Grubelic Ravic K, Serman L, Pavicic Dujmovic A, Brcic I et al (2021) Aberrant expression of SFRP1, SFRP3, DVL2 and DVL3 Wnt signaling pathway components in diffuse gastric carcinoma. Oncol Lett 22:822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tao H, Yang JJ, Shi KH, Li J (2016) Wnt signaling pathway in cardiac fibrosis: New insights and directions. Metabol Clin Exp 65:30–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q, Wang L, Wang S, Cheng H, Xu L, Pei G et al (2022) Signaling pathways and targeted therapy for myocardial infarction. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7:78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu HH, Cao G, Wu XQ, Vaziri ND, Zhao YY (2020) Wnt signaling pathway in aging-related tissue fibrosis and therapies. Ageing Res Rev 60:101063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Zheng X, Zhang C, Zhang C, Bu P (2021) Lcz696 alleviates myocardial fibrosis after myocardial infarction through the sFRP-1/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol 12:724147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chanda D, Otoupalova E, Smith SR, Volckaert T, De Langhe SP, Thannickal VJ (2019) Developmental pathways in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med 65:56–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng Y, Ren J, Gui Y, Wei W, Shu B, Lu Q et al (2018) Wnt/β-catenin-promoted macrophage alternative activation contributes to kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 29:182–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao J, Liu J, Niu J, Zhang Y, Shen W, Luo C et al (2019) Wnt/β-catenin/RAS signaling mediates age-related renal fibrosis and is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Aging Cell 18:e13004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mencke R, Olauson H, Hillebrands JL (2017) Effects of Klotho on fibrosis and cancer: a renal focus on mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 121:85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.