Abstract

Introduction

Adult spinal Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) presents a treatment challenge due to ongoing controversies. Traditional approaches such as curettage with bone grafting and internal fixation are preferred for severe cases involving mechanical instability, neurological deficits, or deformity. This study aimed to explore the efficacy of a customized approach involving simple posterior instrumentation without curettage or bone grafting in treating adult spinal LCH.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed a prospectively maintained database of all spine surgeries conducted at our institute from April 2013 to December 2020. Adult patients (age≥20) diagnosed with LCH were included. We assessed surgical methods, adjuvant therapy, and clinical results, such as perioperative progression of disease, symptoms, and recurrence.

Results

Four male patients aged between 21 and 28, each with a single spinal LCH lesion (T6, T5, and C5) except one case (T5 and T7), were treated. Diagnoses were confirmed via biopsy (two open, two needle biopsies). Whole-body computed tomography or bone scintigraphy revealed no additional LCH lesions in any patient, except in one patient with a small lung nodule. All patients presented with severe back or neck pain and pathological fractures at the affected vertebra. Thoracic LCH cases received percutaneous pedicle screw fixation, while the cervical case was managed with conventional posterior instrumentation using lateral mass screws. After surgery, all patients experienced significant pain relief, halted bone lysis, and rapid new bone formation. One patient underwent chemotherapy postsurgery. Over 3 years of follow-up, imaging studies revealed no recurrences of the disease.

Conclusions

Posterior instrumentation, without the need for curettage or bone grafting, is a promising surgical treatment for adult spinal LCH. This method may effectively halt lesion progression, prevent spinal deformity, and avert neurological deficits in the patients with progressive spine lesion where conservative treatment may not adequately prevent vertebral fractures.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), Adult spinal LCH, Posterior instrumentation, Curettage, Spine tumor, Percutaneous pedicle screw

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease that is particularly prevalent in children, characterized by the accumulation of CD1a+/Langerin+ LCH cells1). The clinical spectrum ranges from single-system LCH, which may spontaneously remit, to multiple-system LCH, treated with chemotherapy1). In children, spinal LCH is usually treated nonsurgically and resolves spontaneously with the collapse of the affected vertebra2,3). Remodeling of the affected vertebra is observed, particularly in children2-5). However, adult spinal LCH often presents with neurological symptoms and vertebral destruction, necessitating surgical intervention in most cases6,7). Traditional surgical treatment typically involves lesion curettage with bone grafting and instrumentation, yielding satisfactory clinical results8-11). However, these surgeries are invasive, involving significant tissue damage, bone harvesting, losing mobile segments, and potential future complications such as adjacent segment disease12).

In contrast, we have been treating adult spinal LCH cases with severe vertebral bone lysis using simple posterior fixation without curettage or bone grafting. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of our treatment approach for adult spinal LCH.

Materials and Methods

This study was a retrospective observational case series and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed patients who underwent surgery for histologically diagnosed spinal LCH, extracted from a prospectively maintained database of all spine surgeries at our institute from April 2013 to December 2020. Patients below 20 years old were excluded.

Outcomes

We investigated whether remission of spinal LCH lesions was achieved and examined the presence of spinal deformities and neurological deficits at the time of the final follow-up.

Moreover, we recorded demographic and other clinical data, such as imaging studies, comorbidities, symptom duration, surgical methods, and adjuvant therapy.

Results

Four male patients, aged between 21 and 28, underwent surgical treatment. Three patients had single spinal lesion each (T6, T5, and C5), while one patient had multiple lesions (T5 and T7). Whole-body Computed tomography (CT), bone scintigraphy, and/or brain Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed no involvement of other organs in any patients, except for one patient with small lung nodules. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical details of all four patients.

Table 1.

Summary of the Clinical Data of the Patients.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 27 | 26 | 21 | 28 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Smoking | Current | Former | Current | No |

| Concomitant disease | None | None | None | None |

| Symptoms | Severe back pain | Severe back pain | Severe neck pain | Severe back pain and anterior chest pain |

| Neurological deficit | Mild numbness in bilateral lower limbs | None | None | None |

| Diagnostic methods | Two needle biopsies Open biopsy | Needle biopsy | Open biopsy | Needle biopsy |

| Location of the lesion | T6 | T5 | C5 | T5 and T7 |

| Other LCH lesions | None (examined with bone scintigraphy and whole-body CT) | Small nodule in lung (examined with whole-body CT) | None (examined with whole-body CT) | None (examined with whole-body CT and brain MRI) |

| Duration from symptom onset to surgery | 9 weeks | 6 weeks | 20 weeks | 9 weeks |

| Surgery | PPS fixation(T4, T5, T7, and T8) | PPS fixation(T4 and T6) | Open fixation with lateral mass screw(C4, C5, and C6) | PPS fixation(T4, T6, and T8) |

| Adjuvant therapy | None | Chemotherapy | None | None |

| Follow-up periods (years) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Implant removal | No | 2 years postoperatively | 2 years postoperatively | 2 years postoperatively |

| Remission of LCH | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neurological deficit at final follow-up | No | No | No | No |

LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; PPS, percutaneous pedicle screw

The initial symptoms were back or neck pain, localized around the affected lesion, with no preceding trauma or specific incident reported. Notably, one patient (Case 4) had received a COVID-19 vaccine 2 weeks before symptom onset. All patients exhibited substantial and progressive osteolysis in the affected vertebral body. All patients were diagnosed with LCH either by needle biopsy (Cases 2 and 4) or open biopsy (Cases 1 and 3). Specifically, Case 1 underwent an open biopsy along with percutaneous pedicle screw (PPS) fixation after two needle biopsies failed to clarify the diagnosis. Case 3 underwent an open biopsy under general anesthesia due to the location of the lesion in the cervical vertebral body. The duration from symptom onset to surgery was 6-20 weeks.

Postoperatively, all patients experienced significant pain relief. CT scans demonstrated cessation of bone lysis and rapid new bone formation, confirmed within 2 months after surgery. Pathological fracture or deformity of the vertebral shape did not progress after the index surgery, and the shape of the vertebrae was reconstructed to the same form as before surgery. However, deformities caused by fractures that had already occurred before surgery were not repaired even after remodeling (Case 2).

All patients, except one, consented to implant removal, which was successfully performed without complications. One patient (Case 2) underwent chemotherapy 6 months postsurgery at another hospital, although the lung lesion had diminished. Over a 3-year follow-up period, imaging studies revealed no recurrences of the disease.

Case Presentation

Case 1

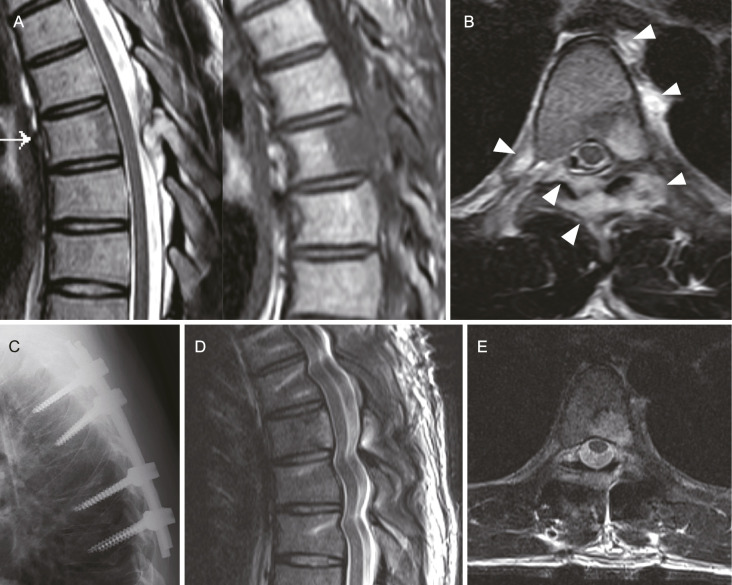

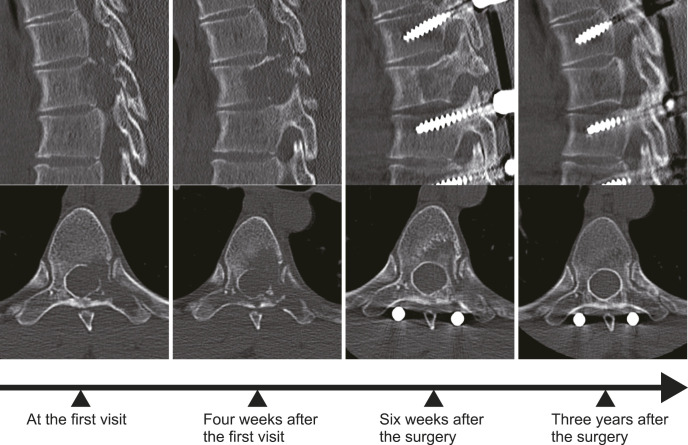

A 27-year-old male presented at our hospital with severe back pain and bilateral lower limb numbness. MRI revealed an abnormal lesion in the T6 vertebra and posterior epidural space (Fig. 1A and B). CT confirmed a large lytic lesion in T6 (Fig. 2). Two CT-guided needle biopsies failed to provide a definitive diagnosis. Due to the rapid progression of vertebral lysis (Fig. 2), we opted for posterior instrumentation using a PPS system combined with an open biopsy (Fig. 1C). He experienced significant relief from back pain soon after the surgery. Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of LCH. Notably, the epidural lesion visible in the preoperative MRI had almost completely resolved in the MRI performed 7 days postsurgery (Fig. 1D and E). A subsequent CT scan, taken 6 weeks postoperatively, demonstrated rapid new bone formation at the lesion site (Fig. 2). He was followed up without any adjuvant therapy. Three years postoperatively, a CT scan showed the vertebra appearing almost normal, with the patient remaining asymptomatic (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Imaging study of Case 1: A, T2-weighted (left) and T1-weighted (right) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) displaying an abnormal lesion in the T6 vertebral body, lamina, and epidural space. B, T2-weighted axial MRI highlighting the abnormal lesion extending into the epidural and perivertebral spaces (indicated by white arrowheads). C, Lateral X-ray postfixation surgery, showing the surgical outcome. D and E, T2-weighted MRI scans taken 7 days postsurgery, revealing a significant reduction in the size of the epidural lesion.

Figure 2.

This series shows the progression and treatment response of the bone lysis in Case 1. Following the posterior instrumentation with the percutaneous pedicle screw system, there was a cessation of the rapid bone lysis. New bone formation was observed as early as 6 weeks postsurgery. The final CT scan, taken 3 years postoperatively, reveals a vertebra that appears almost normal.

Case 2

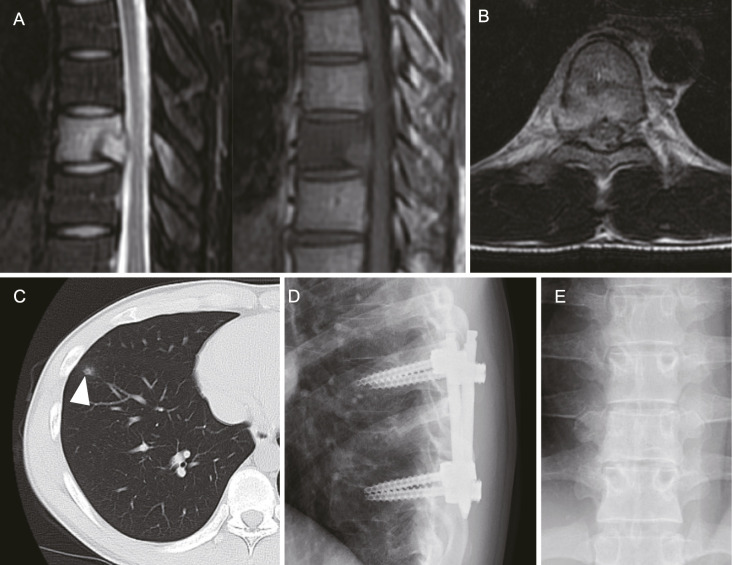

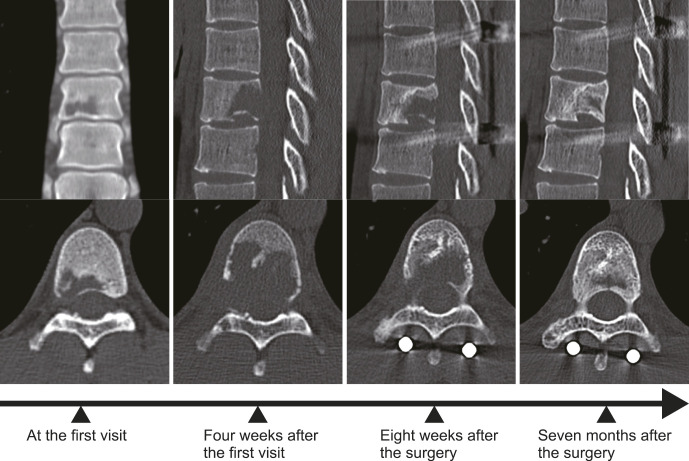

A 26-year-old male presented to our hospital with back pain. MRI identified a lesion in the T5 vertebra (Fig. 3A and B), and a CT-guided needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of LCH. In addition, a lung CT scan revealed a small abnormal nodule (Fig. 3C). He underwent simple posterior fixation using a PPS system (Fig. 3D) due to rapid progression of bone lysis and accompanying fracture of the distal endplate (Fig. 4). His back pain significantly improved soon after the surgery. A CT scan performed 5 weeks postsurgery demonstrated rapid bone reconstitution (Fig. 4). Further imaging after 7 months revealed the vertebra to be almost normal (Fig. 4). Although the lung lesion also diminished, chemotherapy was recommended and administered at another hospital. Two years after the initial surgery, he underwent successful implant removal. At the last follow-up, he was symptom-free, and the X-ray study revealed no abnormalities (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Imaging study of Case 2. A, Fat suppression T2-weighted (left) and T1-weighted (right) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing an abnormal lesion in the T5 vertebra of Case 2. B, Fat suppression T2-weighted axial MRI revealing perivertebral and epidural lesions. C, A small nodule observed in the right lung. D, X-ray taken after the fixation surgery, showing the postoperative status. E, Postoperative X-ray taken 2 years later, after the removal of the instrumentation.

Figure 4.

This series shows the progression and subsequent response to treatment of bone lysis in Case 2. Following the posterior instrumentation using the percutaneous pedicle screw system, a halt in the rapid progression of bone lysis was observed. Seven months after operation, significant bone reconstitution is evident, although some deformation of the endplate persists, as was present prior to the operation.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that posterior fixation alone, without bone grafting or curettage, can facilitate rapid reconstitution of spinal LCH lesions in four adult patients. Notably, this bone reconstitution occurred without the need for adjuvant chemotherapy in all but one case where chemotherapy was administered postreconstitution.

The first-line treatment for spinal LCH, in both pediatric and adult patients, typically involves conservative management, with or without chemotherapy1,13-15). Bisphosphonates represent another treatment option for spinal LCH and other osseous involvement, with several case series reporting successful outcomes16,17). Furthermore, smoking cessation is important for the regression of adult LCH18). In pediatric cases, spinal LCH often resolves without surgery, frequently through spontaneous collapse and remodeling of the affected vertebra2,3). However, this natural process of remodeling may be inhibited in children over 15 years old or in those undergoing vertebral curettage and may lead to residual spinal deformities5). In contrast, adult spinal deformities are less likely to remodel naturally once vertebral collapse occurs, often resulting in persistent vertebral deformities and more common neurological dysfunctions6,7). Therefore, surgical intervention may be warranted if bone lysis rapidly progresses, significant bone destruction and potential fractures are anticipated, or partial fractures have already occurred, to prevent vertebral collapse.

Traditional fusion surgery for spinal LCH8-11) presents several disadvantages, such as extensive tissue damage and the potential for adjacent segment problems12). To address these issues, we adopted a customized approach of posterior instrumentation without curettage or bone grafting. This method was based on the hypothesis that preserving the vertebral body's anatomical shape might allow future remodeling and avoiding curettage could help maintain normal structure. Furthermore, this technique, particularly using the PPS system19), allows for minimally invasive fixation, particularly beneficial in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Furthermore, this method can save mobile segments if instrumentation is removed after recovery.

Our study observed an immediate halt in the progression of bone lysis postsurgery, with rapid bone reconstitution in all patients. The first case notably showed a significant decrease in the epidural lesion just 7 days after surgery (Fig. 1B). The exact mechanisms behind this rapid remission remain unclear. LCH has two aspects, neoplastic nature20,21) and a reactive disease22). We hypothesize that mechanical loading will promote the disease progression of LCH via upregulation of cytokine signaling22) by uncertain mechanisms; thus, the posterior instrumentation may cease the progression of LCH lesion.

The rapid bone destruction observed in our adult spinal LCH cases underscores the critical need for timely intervention. Delayed treatment can lead to irreversible deformities and neurological issues. Once a pathological fracture occurs, the resulting deformity may persist even after bone reconstitution, as demonstrated in Case 2. Therefore, early instrumentation surgery emerges as a viable option for severe cases. Although we have not experienced cases of continued disease progression postsurgery, should this occur, additional treatments such as corticosteroid injections23) or chemotherapy1) could be considered.

Although the results are promising, the small sample size of our study necessitates cautious interpretation. In addition, we did not have access to health-related quality of life scores or visual analog scales for back or neck pain. The mechanisms driving LCH remission remain unclear. Therefore, further research involving larger cohorts and longer follow-up periods is essential to confirm the efficacy and safety of our treatment strategy.

In conclusion, the use of posterior fixation without curettage or bone grafting in four adult patients with LCH resulted in rapid regression of bone lysis and subsequent bone reconstitution. This less invasive approach, employing the PPS system, is an effective treatment strategy for managing progressive LCH lesions in the adult spine, particularly in cases where conservative treatment alone may not suffice to prevent vertebral fracture.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that there are no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sources of Funding: None

Author Contributions: B.O. (Bungo Otsuki): conceptualization, methodology, data curation, and writing original draft preparation.

H.K. (Hiroaki Kimura), S.F. (Shunsuke Fujibayashi), T.S. (Takayoshi Shimizu), T.S. (Takashi Sono), and K.M. (Koichi Murata): visualization, investigation, and writing-reviewing and editing.

S.M. (Shuichi Matsuda): supervision, reviewing, and editing.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyoto University (R2508). Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent. In addition, we used an opt-out method to obtain consent for this study through our institute's homepage, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Kobayashi M, Tojo A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(12):3707-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ippolito E, Farsetti P, Tudisco C. Vertebra plana. Long-term follow-up in five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(9):1364-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg S, Mehta S, Dormans JP. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the spine in children. Long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(8):1740-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raab P, Hohmann F, Kuhl J, et al. Vertebral remodeling in eosinophilic granuloma of the spine. A long-term follow-up. Spine. 1998;23(12):1351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeom JS, Lee CK, Shin HY, et al. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis of the spine. Analysis of twenty-three cases. Spine. 1999;24(16):1740-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang WD, Yang XH, Wu ZP, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of spine: a comparative study of clinical, imaging features, and diagnosis in children, adolescents, and adults. Spine J. 2013;13(9):1108-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang W, Yang X, Cao D, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of spine in adults: a report of 30 cases and outcome. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2010;152(7):1129-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang L, Liu ZJ, Liu XG, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the cervical spine: a single Chinese institution experience with thirty cases. Spine. 2010;35(1):E8-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu GH, Li J, Wang XB, et al. Surgical treatment based on pedicle screw instrumentation for thoracic or lumbar spinal Langerhans cell histiocytosis complicated with neurologic deficit in children. Spine J. 2014;14(5):768-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadashiva N, Rajalakshmi P, Mahadevan A, et al. Surgical treatment of Langerhans cell histiocytosis of cervical spine: case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32(6):1149-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talamonti G, D'Aliberti GA, Debernardi A, et al. Paediatric spinal Langerhans cell histiocytosis requiring corpectomy and fusion at C7 and at Th8-Th9 levels. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012007660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otsuki B, Fujibayashi S, Takemoto M, et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a risk factor for further surgery in short-segment lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(11):2514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueda Y, Murakami H, Demura S, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the lumbar spine in an adult. Orthopedics. 2012;35(12):e1818-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aizawa T, Sato T, Tanaka Y, et al. Signal intensity changes on MRI during the healing process of spinal Langerhans cell granulomatosis: report of two cases. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(1):98-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutsen Y, Esselinckx W, Delos M, et al. Adult onset of multifocal eosinophilic granuloma of bone: a long-term follow-up with evaluation of various treatment options and spontaneous healing. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18(1):69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Georgakopoulou D, Anastasilakis AD, Makras P. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis and the skeleton. J Clin Med. 2022;11(4):909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chellapandian D, Makras P, Kaltsas G, et al. Bisphosphonates in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: an international retrospective case series. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016;8(1):e2016033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suri HS, Yi ES, Nowakowski GS, et al. Pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DY, Lee SH, Chung SK, et al. Comparison of multifidus muscle atrophy and trunk extension muscle strength: percutaneous versus open pedicle screw fixation. Spine. 2005;30(1):123-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alayed K, Medeiros LJ, Patel KP, et al. BRAF and MAP2K1 mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a study of 50 cases. Hum Pathol. 2016;52:61-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Degar BA, et al. Recurrent BRAF mutations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood. 2010;116(11):1919-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Graaf JH, Tamminga RY, Dam-Meiring A, et al. The presence of cytokines in Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. J Pathol. 1996;180(4):400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimondi E, Mavrogenis AF, Rossi G, et al. CT-guided corticosteroid injection for solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the spine. Skelet Radiol. 2011;40(6):757-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]