Abstract

The development of an efficient catalyst to meet the world's increasing energy demand and eliminate organic pollutants in water, is a concern of current researchers. In this article, a highly effective composite has been synthesized using the solvothermal approach, by incorporating CuWO4 nanoparticles into Fe-based MOF, Fe (BDC). The synthesized samples were analyzed further by some characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscope (FTIR) and scanning electron microscopy. The highest catalytic activity for the oxygen evolution reaction was observed in the CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) composite, which exhibited low overpotential 188 mV to obtained the current density of 10 mA cm−2, and a smaller Tafel slope of 40 mV dec−1. The nanocomposite CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) material showed enhanced visible light absorption and maximum degradation of methylene blue up to 96.92 %. It has been found that this research promotes the development of an efficient MOF-based catalyst for OER and photocatalytic technology.

Keywords: CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe), Nanocomposite, Water splitting, Oxygen evolution reaction, Photodegradation of dye

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Designing highly efficient catalyst by incorporation of CuWO4 in MIL-101(Fe).

-

•

The newly designed CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) showed efficient OER activity.

-

•

The CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) is efficient for methylene blue photodegradation.

-

•

The better photodegradation is associated with Z-scheme heterojunction formation between CuWO4 and MIL-101(Fe).

1. Introduction

For the last few decades, humanity has faced three major challenges: energy shortages, rapidly deteriorating environmental conditions, and resulting economic issues. Surprisingly, all of these issues are linked to one another [1,2]. The majority of the human population relies on fossil fuels to meet their energy requirements. Initially the customers were ignorant of both the shortage of fossil fuels and their potentially harmful effects on the environment. Scarcity has worsened unparalleled inflation, and uncontrolled consumption resulted in environmental degradation [3]. Taking into account the rise in energy crises and environmental concerns it is crucial to create green and manageable energy assets to substitute non-renewable energy sources like fossil fuels [4]. Researchers emphasized the need of an alternative and sustainable energy source that have no adverse effects on surrounding in any manner. In order to mitigate energy sources, water splitting, oxygen and hydrogen production are an efficient and viable solution to exceed all contemporary sources and is the focus of current research [5,6].

The persistent increment of industrialization and urbanization caused serious ecological contamination. Most of the developing countries are unable to provide an adequate amount of water to the consumers owing to industrial contaminants. Different dyes are emitted in water. Among various dyes, methylene blue (MB) is frequently utilized in paper, textile and varnish industries. Uncontrolled MB discharge can result in mutation, toxicity, allergic reactions, and carcinogenic activity [[7], [8], [9]].

Since the grown material will be used for electrocatalysis or photocatalysis, it should be active, extremely effective, or stable, which may have reduced charge carriers' recombination, adsorption energy for photocatalytic and water oxidation processes. Water splitting is based on two half reactions including oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at anode and cathode, respectively and both depends on overpotential to proceed at an appropriate rate [10]. As OER demands significantly higher over-potential than HER, this is especially important for the four electrons coupled reaction. An efficient development of OER catalyst with a minimal over-potential is therefore a major challenge [11].

Catalytic materials like ZnO, TiO2 and graphene oxide have been researched in this regard for water splitting [[12], [13], [14]]. However, due to inefficiencies including high electron-hole pair recombination and high band gap, their catalytic efficiency is very low [15,16]. Catalyst efficiency is improved through a variety of techniques, including heterostructure composite formation, doping, dye sensitization and metal functionalization [[17], [18], [19]]. Effective strategies involving semiconductor combinations and metal ion doping to form an efficient heterostructure also improves catalytic performances [20]. The development of interfaces between the cocatalysts and the photocatalysts modifies the surface charge density and prevent unfavorable carrier recombination at heterojunction interfaces in addition to promoting photogenerated charge separation [21].

CoP cocatalyst with single-atom phosphorus vacancies defects (CoP-Vp) was synthesized and coupled with Cd0.5Zn0.5S to construct CoP-Vp@Cd0.5Zn0.5S (CoP-Vp@CZS) heterojunction photocatalysts. Under visible light irradiation, the nanohybrids exhibit an attractive photocatalytic hydrogen generation activity and improves electron transfer and charge separation efficiencies than that of pristine ZCS samples [21]. Another di-defects modified VSe2 electrocatalyst prepared and exhibits higher HER than most previously reported non-noble metal HER electrocatalysts, requiring overpotentials of 67.2, 72.3, and 122.3 mV to reach 10 mA cm−2 in acidic, alkaline, and neutral environments, respectively [22]. Zhang et al., synthesized SVD-WS2@DG nanocomposite which requires a much smaller overpotential (108 mV vs. RHE) than SVD-WS2, WS2, to reach the current density of 10 mAcm−2. This indicates that the SVD-WS2@DG hybrids have efficient HER activity [23].

Metal-organic framework (MOF), is a kind of porous material that function as an effective catalyst by coordinating the inorganic nodes with organic linkers (bidentate or multidentate ligands). Because of the enormous surface area of MOF, composites can be created by adding diverse guest molecules such as metal oxide nanoparticles, polyoxometalates, polymers and carbon materials [24]. MOFs are widely used in several applications like adsorption, catalysis, storage, sensing and drug delivery [25]. MOFs performance in the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) is also promising. However, MOFs generally have low endurance and resistance to electricity, which lowers the efficiency of their energy conversion [26]. Also due to low charge separation efficiency few reports are present of its individual use for photocatalytic activity [27]. MOFs are used as sacrifice templates to construct various heterostructure with electrical reactivity and strong electrical properties [28]. The photocatalytic activity of MIL-101(Fe) can be enhanced by mixing it with an appropriate materials to form heterojunctions [29].

CuWO4, an inexpensive and eco-friendly transition metal tungstate, has drawn a lot of interest in a number of areas, including photocatalysis [30], degradation of contaminants, and water splitting owing to its exceptional chemical stability, electrical, catalytic qualities, and low cost [31] have played a key role in the construction of the active OER catalysts and photocatalyst material. Z-scheme heterojunction catalysts have attracted a lot of attention in recent years because of its unique electronic structure not only promotes electron-hole pairs separation, but it also maintains a great capability for redox [32].

Numerous Fe based MOF heterojunctions have been reported such as ZnO/MIL-101(Fe) for degradation of Rhodamine B [33]. MIL-101(Fe)/Bi2WO6, V2O5/NH2-MIL-101(Fe) [34,35], CeO2/MIL-101(Fe) [36], MIL-101(Fe)/Bi2O3 [37] and MIL-101(Fe)/g-C3N4 [38] showed excellent photocatalytic activity. Materials based on MOFs are also used for OER like NiS@MOF-5, that required an overpotential of 174 mV to deliver 10 mA cm−2 [39]. Additionally, heterostructures CoOx/UiO-66 and NiO/UiO-66 are emerged for better oxygen evolution reactions [40].

In this project, CuWO4 nanoparticles are synthesized and are successfully incorporated in MIL-101(Fe). The CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) composite material benefits from numerous accessible reactive sites, optimized photo-redox ability, and reduction in electron hole pair recombination. The current fabricated materials were used to investigate OER for water splitting and methylene blue photodegradation.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Chemical reagents

All the chemicals used were sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na2WO4.2H2O, Sigma Aldrich, 99.99 %), copper II nitrate (Cu(NO3)2.3H2O, Sigma Aldrich, 99.9 %), iron III chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3.6H2O, Sigma Aldrich, 97 %), 1,4-benzene dicarboxylic acid (BDC, Sigma Aldrich, 98 %), ethanol (Analar, 99.8 %), N-N-dimethylformamide (Riedel-deHaen, 99 %), acetone (Sigma Aldrich, 99.8 %), distilled water, Potassium hydroxide (KOH, Sigma Aldrich, 85 %) and Nickel foam (NF, China).

2.2. Preparation of MIL-101(Fe)

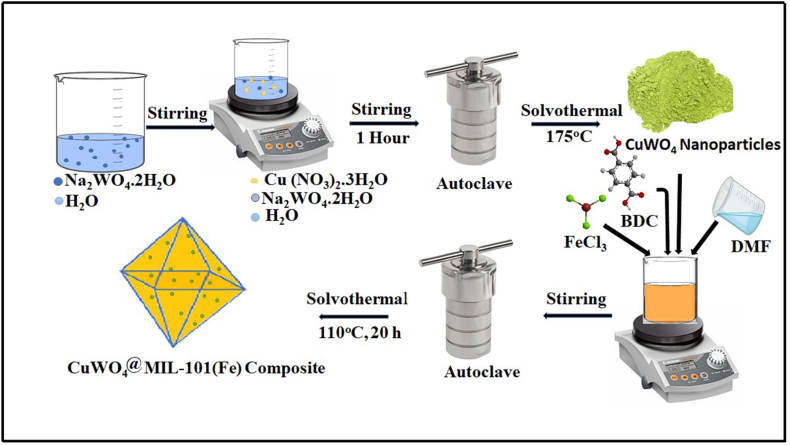

MIL-101(Fe) was synthesized by solvothermal route [41]. After adding 1.24 mmol of 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid and 2.48 mmol of iron chloride hexahydrate to 50 mL of DMF, the mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The mixture was poured in 100 mL autoclave and was then kept in an oven for 20 h at 110 °C. The light brown product was isolated by centrifugation, rinsed with water and finally with ethanol. The precipitate was then dehydrated in oven at 150 °C.

2.3. Synthesis of CuWO4 nanoparticle

Hydrothermal route was employed to synthesize copper tungstate nanoparticles. After adding Na2WO4.2H2O (2 mmol) to 25 mL of water, 0.03 M Cu(NO3)2.3H2O solution was poured to the first solution, and mixture was magnetically stirred for 1 h. The solution changed to a light blue color. This mixture was then put into an autoclave and heated to 175 °C for 24 h. The resulting light green precipitates were washed with ethanol and dried for 5 h at 70 °C [42].

2.4. Preparation of CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) nanocomposite

Pre-synthesized CuWO4 nanoparticles was incorporated into host MOF to fabricate CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) nanocomposite. Iron chloride hexahydrate (2.48 mmol) was dissolved in 30 mL DMF. Meanwhile, 0.01 g of nanoparticles (CuWO4) were sonicated in 10 mL of DMF and then added to the above mention solution. 20 mL of DMF was used to dissolve 1.24 mmol benezene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid and dropwise added to the above mixture. The solution was poured into stain-less steel Teflon lined autoclave and then kept in an oven at 110 °C for 20 h. The product obtained by centrifugation was washed with water and then with ethanol. The product was dried at 150 °C to synthesize powdered CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) composite [43]. Schematic representation for preparation of CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) nanocomposite is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration for synthesis of CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) nanocomposite.

2.5. Fabrication of electrode

NF was cut into small sections (1 × cm2) followed by sonication for 20 min in acetone, DI water and ethanol, after that used as working electrode. The furnace was used to dehydrate the electrodes at 333 K for 20 min. Electrocatalyst ink was created by using 5.0 mg of samples homogenized in (100 μL) DI water for 1 h to evaluate the activity of fabricated materials via ultrasonic assisted processing. The drop-casting technique was used to deposit ink on NF.

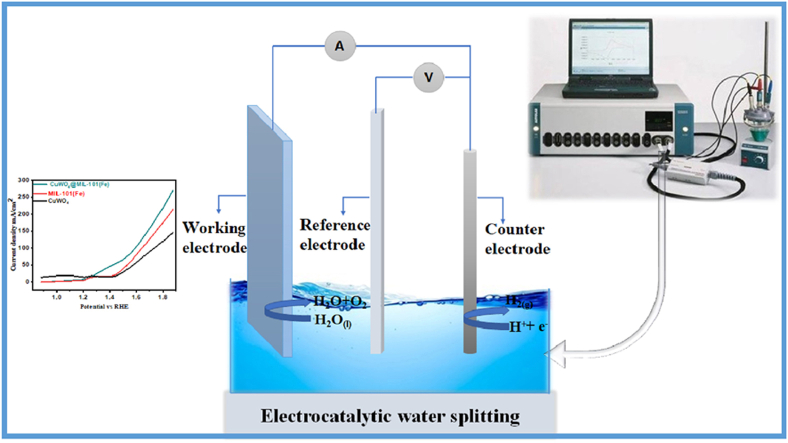

2.6. Oxygen evolution reaction studies

Cyclic voltammetry (CV), linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were performed by Autolab PGSTAT-204 (Metrohm) in 1.0 M KOH aqueous electrolyte for studying OER of synthesized samples. Using three electrode systems, a Pt wire (counter electrode), an Ag/AgCl (reference electrode), and fabricated materials on NF (working electrode) were held in place by a Pyrex glass cell to measure all the parameters. The cyclic voltammetry studies employed both positive and negative potentials and the LSV only employed the positive potential, scanning at 5 mV−1.

Expression (1) was used to convert recorded voltage to the RHE potential from the standard Ag/AgCl reference potential [44].

| (1) |

To evaluate the kinetics and performance of the prepared materials, a Tafel slope was calculated by creating a graph between overpotential (η) vs. log j using the polarization curve and by equation (2) [45].

| (2) |

In equation (2) ‵a’ is the transfer of charge coefficient, ‵j’ is the current density, η shows the overpotential, ‘F’ is the Faraday constant and ‵n’ represents the number of electrons active in the catalytic reaction.

To compute electrochemical surface area (ECSA), which is a crucial factor in enhancing the electrocatalytic efficiency of all products equation (3) can be utilized [46].

| (3) |

Different CV plots were obtained at multiple scan rates (20, 40, 60 and 80 mV−1) in the non-faradic region. The change in j was determined by calculating the difference between the negative and positive current densities. The straight line for the Cdl value was obtained by plotting the values of j against the required scan rates. The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was then calculated by dividing the resulting slope by 2. Broad ECSA with numerous exposed active sites is necessary for the electrochemical activity of potential working materials.

EIS is another way to determine the mechanism of water splitting, electrode surface characteristics and charge transfer process in materials.

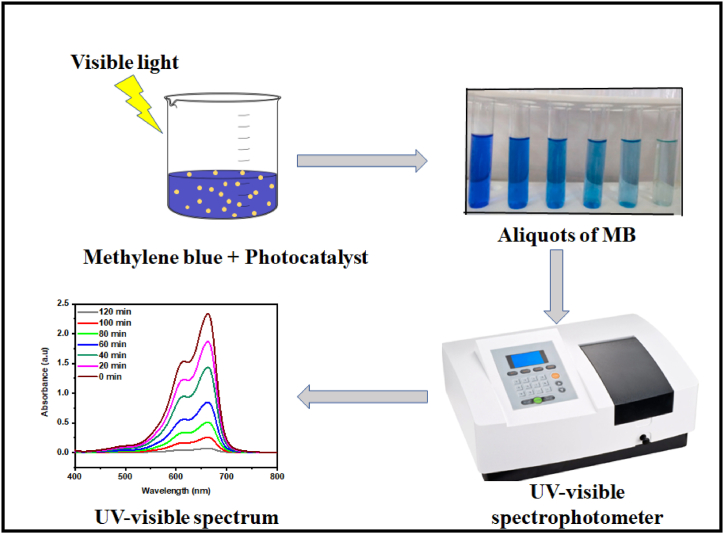

2.7. Photocatalytic activity measurement

In the usual process, 1L of MB dye solution was prepared by dissolving 31.98 mg of MB in deionized water. 0.1 g of CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) was added in 100 mL dye solution. Mixture was then magnetically stirred in photoreactor for 30 min in dark to establish the adsorption-desorption equilibrium. The adsorption capacity of CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) shown in Fig. 2 gradually enhanced with the passage of time and then becomes constant. CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) composite showed remarkable adsorption capacity than other catalysts.

Fig. 2.

Adsorption capacity study of CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe).

The adsorption capacity (qe; mg/g) were determined by equation (4).

| (4) |

Where qe is the adsorption capacity (mg g−1), Co and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of dye in mg L−1; V is the volume of sample solution (L) and W is the amounts of adsorbent (g).

5 mL aliquot of CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) was taken and centrifuged to eliminate solid particles and at 663.5 nm absorbance was measured by spectrophotometer. The MB dye solution was then exposed to a tungsten lamp of 500 W. The solution's UV–Vis absorbance was checked after every 20 min by removing 5 mL sample from the reactor.

The photocatalytic activity measurements are given in Fig. 3. The % degradation of MB was calculated by the following equation (5).

| (5) |

Where Ao and At represents dye absorbance at 0 and time t respectively.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of photocatalytic activity of CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) nanocomposite.

2.8. Characterization

To perform the functional group analysis of materials, Bruker Alpha II Fourier-transform infrared spectrophotometer was used in the range of 4000-400 cm−1. Crystallinity of samples were recorded on Shimadzu XRD-6000 in the range of 4°-80° at scan rate of 5° min−1. Scanning electron microscopy (Nova Nano SEM-LUMS and Apreo 2 SEM) were used to analyze morphology of the products. To access the efficiency of catalysts, Shimadzu-2600 UV–visible spectrophotometer was used at room temperature for recording the photodegradation of MB dye.

3. Results and discussion

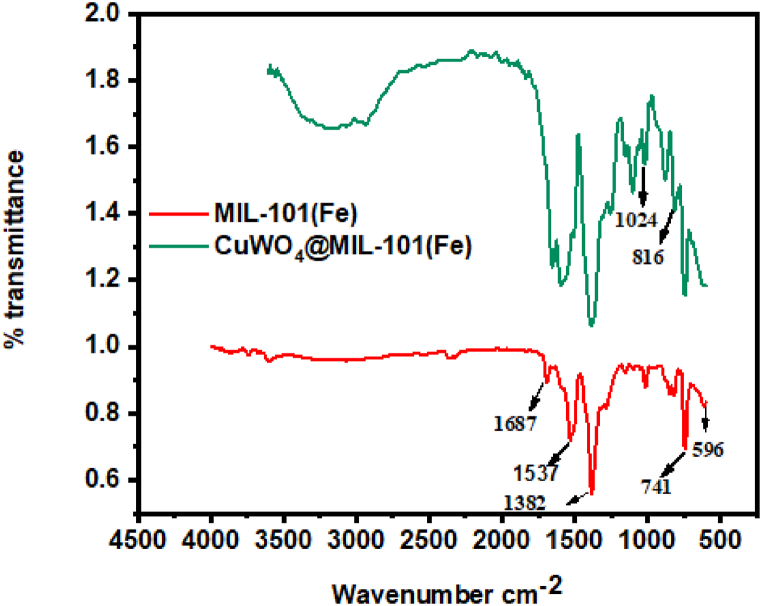

3.1. FTIR analysis

The structure of the fabricated materials was confirmed using FTIR. Infrared spectroscopy shows the characteristics peaks at 1687 cm−1, 1537 cm−1, 1382 cm−1 that represents the vibration of C=O, asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibration peaks of carboxylic group (COO) in 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid. Fig. 4 depicts the FTIR spectra of synthesized materials. Other peaks at 741 cm−1 and 596 cm−1 are caused by the C-H bond stretching of benzene and Fe-O vibration respectively [41]. Analysis of composite shows all the prominent peaks of MIL-101(Fe). The additional absorption peaks at 1024 cm−1 and 816 cm−1 corresponds to W-O and Cu-O bonds, demonstrating the successful incorporation of nanoparticles in MIL-101(Fe) [30,47].

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectrum of MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe).

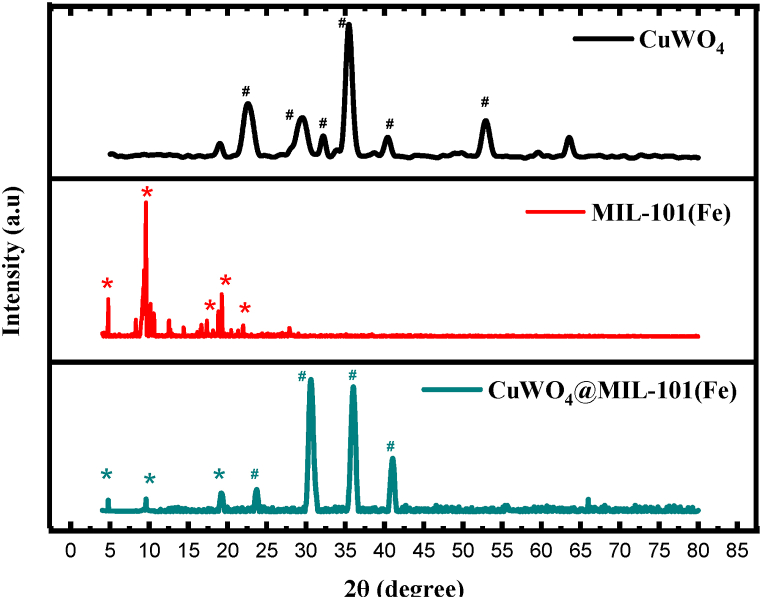

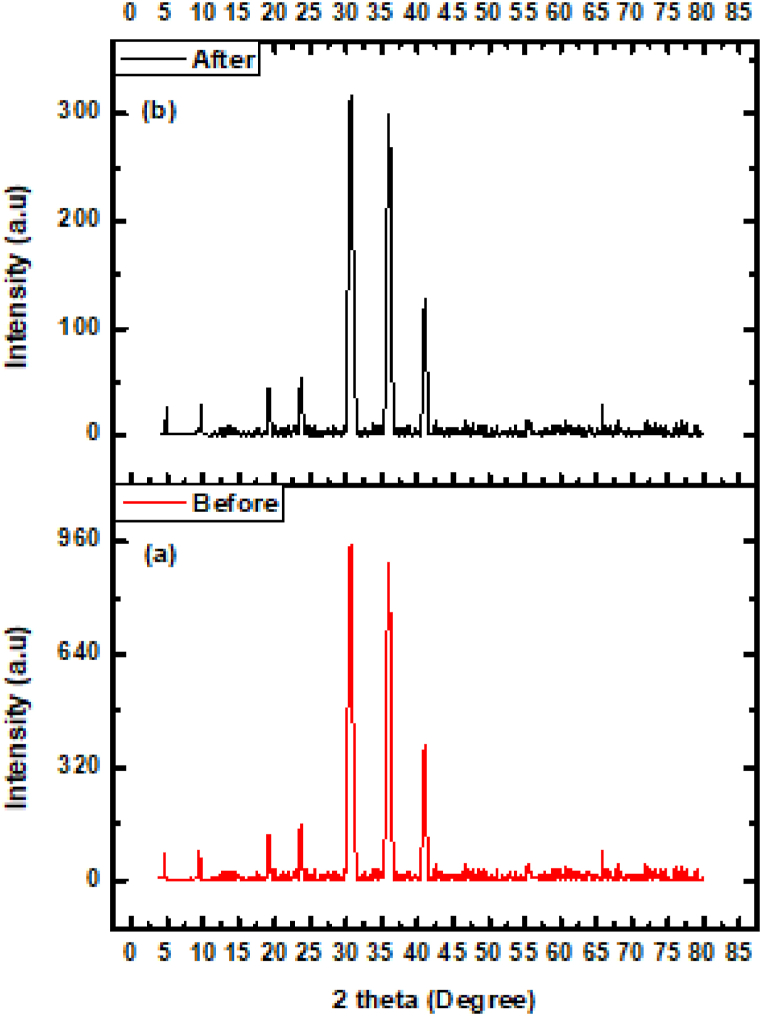

3.2. X-ray diffraction pattern

XRD was used to determine the nanomaterials phase purity and degree of crystallinity. The crystallinity of prepared samples CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe), CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) was identified by X-ray diffraction approach as shown in Fig. 5. All the materials have grown well in crystalline form and intense peaks are observed. The well-defined diffraction peaks at 2θ about 4.79°, 9.61°, 18.8°, 19.26°, 21.99° correspond to MIL-101(Fe) and is in good agreement with the reported pattern [41,48]. The typical peaks of CuWO4 are located at 22.57°, 29.69°, 32.17°, 35.48°, 40.39°, 40.39°, 55.6° [[49], [50], [51]]. P-XRD analysis of CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) shows that majority of the diffraction peaks are related to MIL-101(Fe) and some additional NPs diffraction peaks are also observed. The XRD analysis of samples reveals that CuWO4 NPs have been successfully incorporated into MIL-101(Fe) and no obvious alterations have been observed in distinct PXRD pattern. It is indicated that MIL-101(Fe) has retained its distinctive pattern and crystallinity after the incorporation of CuWO4 NPs.

Fig. 5.

XRD pattern of CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe), CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe).

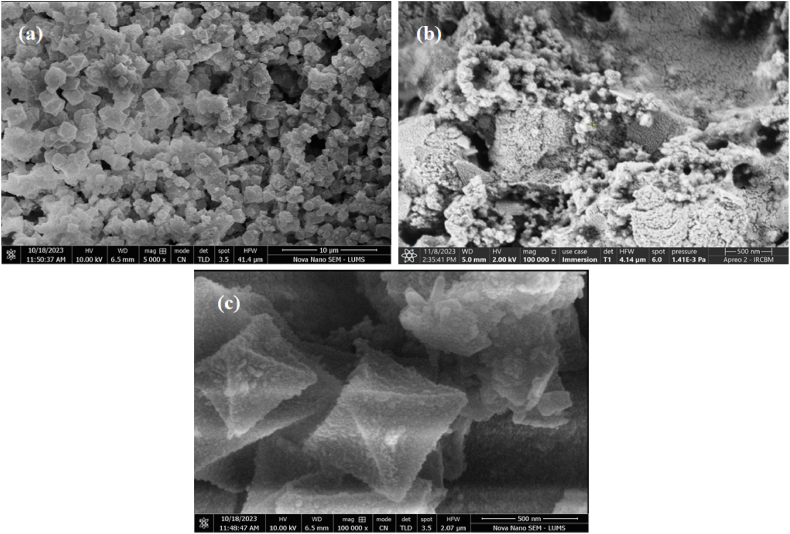

3.3. Scanning electron microscopy

Morphological analysis of the fabricated materials were visualized by SEM. Fig. 6(a–c) represents the fabricated material's SEM images. Fig. 6(a) shows the well defined, smooth surface, octahedral architecture of MIL-101(Fe) [52]. Fig. 6(b) shows CuWO4 nanoparticles, agglumerated and spherical in shape [47]. As for CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) in Fig. 6(c) illustarates the CuWO4 nanoparticles anchored on MIL-101(Fe) that represents the incorporation and composite formation.

Fig. 6.

SEM images of (a) MIL-101(Fe), (b) CuWO4, (c) CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe).

3.4. Electrochemical measurements

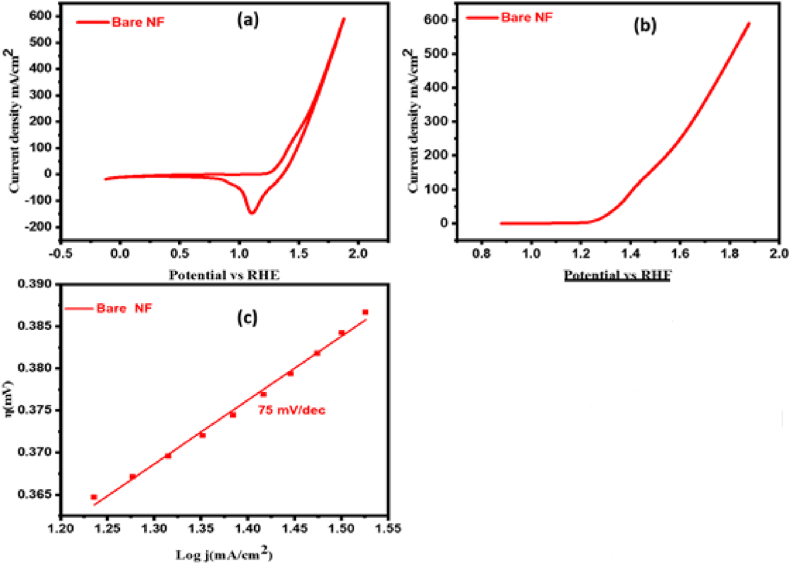

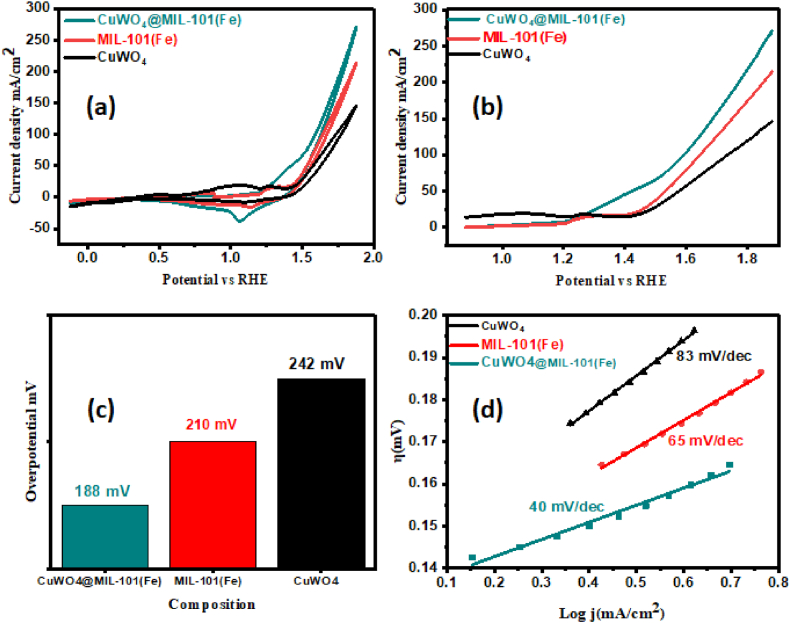

For the electrochemical investigation, the Autolab PGSTAT-204 workstation was employed. The OER catalytic performance of each synthesized product was assessed in 1.0 M alkaline solution using a three-electrode setup. The OER performance of all catalysts was examined; the findings are shown in Fig. 7, Fig. 8. Using CV and LSV employing a sweep rate set at 5 mV s−1, bare NF in Fig. 7(a and b) and all samples CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe), and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) were analyzed, as illustrated in Fig. 8(a and b). According to the LSV results of bare NF and the fabricated material, the calculated values for the onset potential were 1.30, 1.44, 1.38, 1.27 V vs RHE for bare NF, CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe), respectively at 10 mA cm−2, the resulting overpotential for bare NF, CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe), and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) was 345, 242, 210, and 188 mV, respectively thus providing a more precise relationship between the electrochemical performance of the fabricated nanomaterials as depicted in Fig. 8(c). Among all the nanomaterials, CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) nanocomposite shows the enhanced electrochemical activity due to its superior contact area, small average crystallite size, significant electrical conductivity, lower onset and overpotentials. The Tafel slope was derived from the preceding polarization curves to give perception of OER process' reaction speed. The overall mechanism of OER involves the of four main steps depicted below [4,53].

| M + OH− → M − OH + e− | (6) |

| M − OH + OH− → M − O + H2O + e− | (7) |

| M − O + OH− → M-OOH + e− | (8) |

| MOOH− + OH− → M + O2 (g) + e− | (9) |

In the above equation, M is the catalytic active site, MOH, MO, MOOH are the reaction intermediates. The OER dynamic rate rises, when the overpotential and slope values are smaller [54]. Fig. 7, Fig. 8Illustrates the computed Tafel plots for bare NF CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe), and CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) which were found to be 75, 83, 65, and 40 m V dec−1, respectively suggesting the significant charge mobility in an alkaline medium. These results increasingly support the rapid response rate, which is a sign of the promising electrochemical characteristics of the MOF composites.

Fig. 7.

(a) Cyclic voltammogram (b) LSV of bare NF (c) Tafel slope of bare NF.

Fig. 8.

(a) Cyclic voltammogram (b) LSV of all the fabricated materials (c) Overpotential (d) Tafel slope of all the fabricated products.

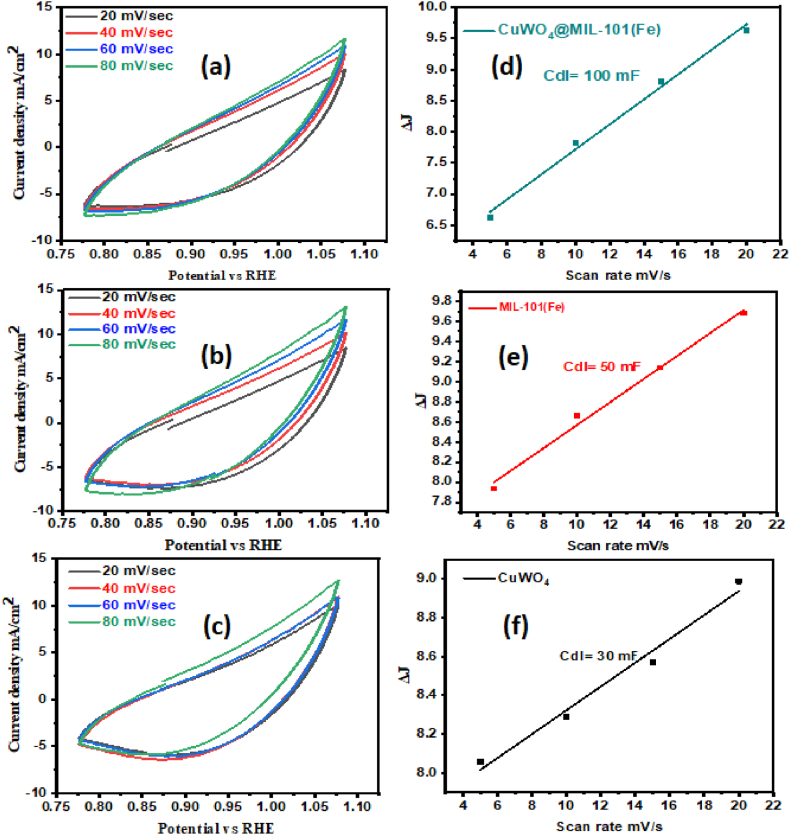

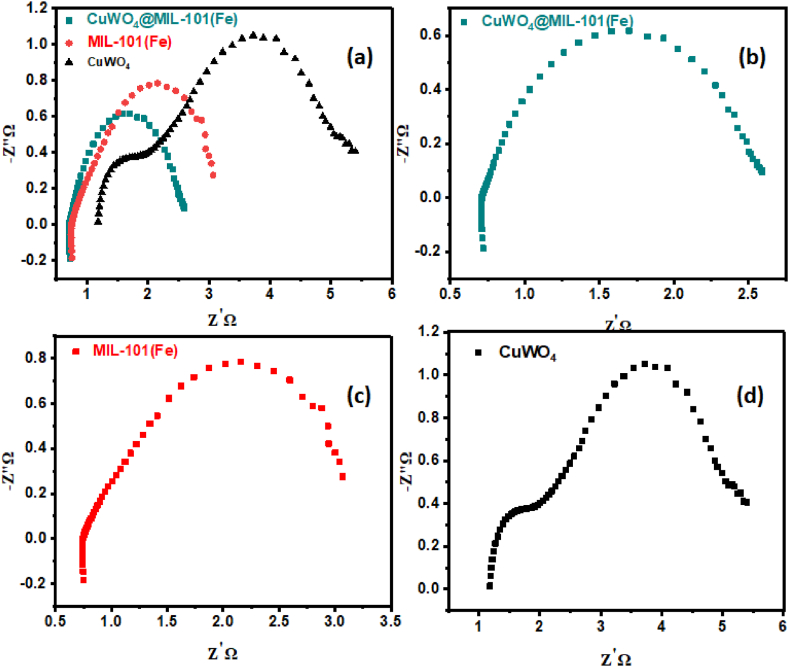

As seen in Fig. 9(a–c), multiple CV graphs in the non-faradic zone were collected at various scan rates of (20, 40, 60, and 80 mV s – 1). The value of j was found from the polarization cycle and was plotted against fixed scan rates producing a straight line. Double layer capacitance was determined from half of the straight-line slope, useful in ECSA computation. As shown in Fig. 9(d–f), the computed Cdl values for CuWO4 and MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) composite were 30 mF, 50 mF, and 100 mF, respectively. The obtained Cdl was divided by a capacitance of 0.040 cm− 2 for the ECSA calculation. The corresponding ECSA values for CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe), and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) were 750 cm2, 1250 cm2, and 2500 cm2 respectively. The fabricated material's increased ECSA value indicates the presence and availability of the catalytic site, both of which are crucial for the exchange of electron that occurs during the electrocatalytic procedure. Increased ECSA indicates that there is greater number of active sites in the composite [3]. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy is also an important technique to access the OER activity of nanomaterials. The CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) composite exhibits a shorter semicircle in the Nyquist plots than CuWO4 and MIL-101(Fe) as shown in Fig. 10(a–d). This work demonstrates the robust electrocatalytic activity of nanocomposite promoting the charge transfer reaction compared to other materials. This phenomenon elucidates the rapid oxygen evolution reaction activity. Table 1 shows the overpotential and Tafel slope of CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) compared to other reported results showing a significant improvement in the current investigation's findings.

Fig. 9.

(a–c) CV plots at different scan rates, (d–f) Cdl plots of synthesized catalysts.

Fig. 10.

(a) Combined EIS Nyquist plot of all synthesized material, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for (b) CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe), (c) MIL-101(Fe), (d) CuWO4.

Table 1.

OER comparison of MOF- based composites in an aqueous medium with current work.

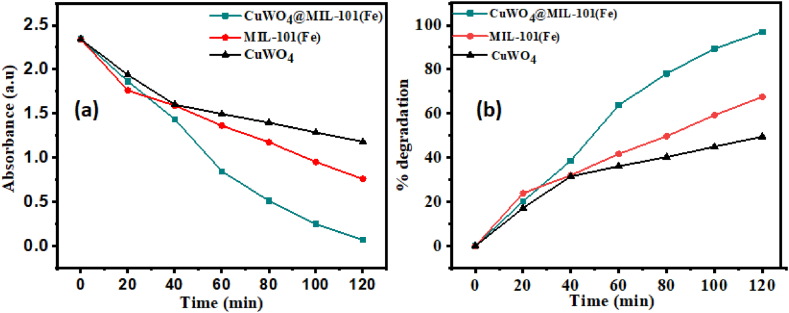

3.5. UV–visible spectroscopic analysis

Dye solution containing CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) shows minimum absorbance of 0.072 (a.u) in comparison to the dye solution comprising all other photocatalysts. The calculated percentage degradation of methylene blue is 49.55 %, 67.57 %, 96.92 % by CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) respectively as shown in Fig. 11(b). This demonstrates the heterojunction formation enhances MB photodegradation.

Fig. 11.

(a) Light absorbance by MB after CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) treatment for 120 min and (b) % degradation of methylene blue after CuWO4, MIL-101(Fe) and CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) treatment for 120 min.

The % degradation comparison of reported photocatalysts is given in Table 2. MB is one of the most studied organic pollutants due to its poisonous nature and water solubility. It has been linked to a variety of disorders in people.

Table 2.

Comparison of the current work's photocatalytic activity with that the reported MIL-101(Fe) composites.

| Sr. No. | Photocatalysts | Contaminants | Light Source | Radiation Time (mins) | Degradation Percentage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MnOx/MIL-101(Fe) | RhB | Visible | 60 | 78 | [61] |

| 2 | ZnO/MIL-101(Fe) | RhB | Visible | 300 | 80.7 | [33] |

| 3 | M-MIL-101(Fe)/TiO2 | Tetracycline | Solar light | 60 | 95.95 | [29] |

| 4 | Cu2O/Fe3O4/MIL-101(Fe) | Ciprofloxacin | Visible | 105 | 99.2 | [62] |

| 5 | CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) | MB | Visible | 120 | 96.92 | This work |

MB was degraded by synthesized photocatalyst under visible light. MB concentration is found to decrease over time. MB is degraded by MIL-101(Fe) under visible light and its absorbance intensity changes from 2.341 (a.u) to 1.181 (a.u). Similar phenomenon was shown by CuWO4 and CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe). It can be observed that after 120 min all the samples degraded MB, but CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) degraded MB efficiently than all other samples. It can be seen from Fig. 11(a) that after 120 min.

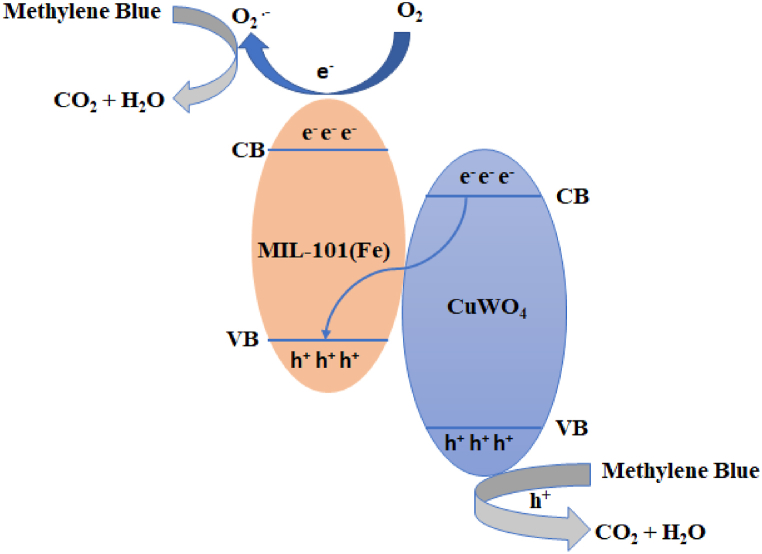

3.6. Proposed possible photodegradation mechanism of MB

Construction of heterojunction is one of the promising strategies for the separation of photogenerated electron hole pair. Z-scheme heterojunction is formed when VB and CB of photocatalyst (A) is higher than the photocatalyst (B), while the CB of photocatalyst (B) is higher than the VB of photocatalyst (A). Under exposure to light, photogenerated electrons in CB of photocatalyst (A) with strong reduction abilities and holes in VB of photocatalyst (B) having strong oxidation abilities are retained. The photogenerated electrons in CB of photocatalyst B and holes in the VB of photocatalyst A combine with inferior redox potential [57]. According to literature, the VB and CB edges of MIL-101(Fe) are +0.98 V and −0.75 V, respectively [58] and VB and CB edges of CuWO4 are +2.55 V and +0.20 V, respectively [59]. The CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) fulfills the requirement of Z-scheme. When the composite is irradiated with the visible light, the electrons in the valence band of CuWO4 jumps to conduction band leaving behind the holes in VB. Same phenomenon occurs with the MIL-101(Fe), the electrons would jump to the conduction band leaving behind the high energy hole in MIL-101(Fe). The photogenerated electrons at the CB of CuWO4 would recombine with the photogenerated holes in VB of MIL-101(Fe). The photogenerated electrons in the conduction band of MIL-101(Fe) effectively reduce O2 to O2.-. Holes in VB of CuWO4 reacts with OH− to form .OH as shown in Fig. 12. Both the O2.- and .OH effectively degrading the organic dyes [60].

| CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) + hv → CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) (h+ + e−) | (10) |

| O2 + e− → O2.- | (11) |

| H2O + h+ → OH. | (12) |

| O2.- + OH. + Methylene blue → Degradation Products | (13) |

Fig. 12.

Proposed mechanism of photocatalytic degradation of organic dye.

3.7. Stability of catalyst

If we compare the XRD data of recovered catalyst with that of fresh catalyst we have analyzed that the catalyst still possess all the functionalities as indicated by the emergence of peaks but they have of less intensity indicating despite of less intense peaks catalyst is still present in its original form shown in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

XRD pattern of CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) catalyst stability before and after photocatalysis.

4. Conclusion

In the current project, CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) nanocomposite was synthesized successfully by the solvothermal method. Characterizations results supported the confirmation of nanocomposite. The fabricated nanocomposite is highly active for OER activity. The better OER activity of CuWO4@MIL-101 (Fe) is ascribed to the heterojunction formation between CuWO4 and MIL-101(Fe). Z-scheme heterojunction decreases the recombination of electron hole pairs. The enhanced active sites due to greater surface area, responding excellent activity for OER such as small overpotential 188 mV, lower onset potential 1.27 V to attain current density at 10 mA cm−2. The CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) nanocomposite gives a lower Tafel slope of 40 mV dec−1, indicating favorable electrons transfer and improved catalytic activity. CuWO4@MIL-101(Fe) composite is also effective in photodegradation of methylene blue dye, achieving % dye degradation of up to 96.92 within 120 min. It is anticipated that solvothermal synthesis of highly efficient catalyst opens up new pathway for electrochemical OER and photodegradation of organic dyes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mariam Khan: Writing – original draft, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Muhammad Mahboob Ahmed: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Muhammad Nadeem Akhtar: Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis. Muhammad Sajid: Writing – review & editing, Software. Nagina Naveed Riaz: Validation, Software, Investigation. Muhammad Asif: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Muhammad Kashif: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Bushra Shabbir: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis. Khalil Ahmad: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Muhammad Saeed: Software, Investigation, Formal analysis. Maryam Shafiq: Software, Investigation, Formal analysis. Tayyaba Shabir: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:Muhammad Nadeem Akhtar reports equipment, drugs, or supplies and statistical analysis were provided by Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Lahore University of Management Science, Pakistan. nil If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledged Institute of Chemical Sciences, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, We are also thankful to the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Lahore University of Management Science, Pakistan for the analysis of samples.

References

- 1.Yuan F., Wei Y.D., Gao J., Chen W. Water crisis, environmental regulations and location dynamics of pollution-intensive industries in China: a study of the Taihu Lake watershed. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;216:311–322. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konduracka E. A link between environmental pollution and civilization disorders: a mini review. Rev. Environ. Health. 2019;34(3):227–233. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2018-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ur Rehman M.Y., Manzoor S., Nazar N., Abid A.G., Qureshi A.M., Chughtai A.H., Joya K.S., Shah A., Ashiq M.N. Facile synthesis of novel carbon dots@ metal organic framework composite for remarkable and highly sustained oxygen evolution reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2021;856 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiaz M., Athar M. Modification of MIL‐125 (Ti) by incorporating various transition metal oxide nanoparticles for enhanced photocurrent during hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4(29):8508–8515. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jatoi Y.F., Fiaz M., Athar M. Synthesis of efficient TiO 2/Al 2 O 3@ Cu (BDC) composite for water splitting and photodegradation of methylene blue. J. Aust. Ceram. 2021;57:489–496. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basith M., Ahsan R., Zarin I., Jalil M. Enhanced photocatalytic dye degradation and hydrogen production ability of Bi25FeO40-rGO nanocomposite and mechanism insight. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29402-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed S., Ahmad Z. Development of hexagonal nanoscale nickel ferrite for the removal of organic pollutant via Photo-Fenton type catalytic oxidation process. Environ. Nanotechnol. 2020;14 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed S., Lo I.M. Phosphate removal from river water using a highly efficient magnetically recyclable Fe3O4/La (OH) 3 nanocomposite. Chemosphere. 2020;261 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdullah M., John P., Ahmad Z., Ashiq M.N., Manzoor S., Ghori M.I., Nisa M.U., Abid A.G., Butt K.Y., Ahmed S. Visible-light-driven ZnO/ZnS/MnO 2 ternary nanocomposite catalyst: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Appl. Nanosci. 2021;11:2361–2370. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabbar A., Fiaz M., Rani S., Ashiq M.N., Athar M. Incorporation of CuO/TiO 2 nanocomposite into MOF-5 for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and photodegradation of organic dyes. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020;30:4043–4052. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandamalla A., Manchala S., Anand P., Fu Y.-P., Shanker V. Development of versatile CdMoO4/g-C3N4 nanocomposite for enhanced photoelectrochemical oxygen evolution reaction and photocatalytic dye degradation applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2021;19 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma M., Huang Y., Liu J., Liu K., Wang Z., Zhao C., Qu S., Wang Z. Engineering the photoelectrochemical behaviors of ZnO for efficient solar water splitting. J. Semiconduct. 2020;41(9) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang J., Durrant J.R., Klug D.R. Mechanism of photocatalytic water splitting in TiO2. Reaction of water with photoholes, importance of charge carrier dynamics, and evidence for four-hole chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130(42):13885–13891. doi: 10.1021/ja8034637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh T.-F., Cihlář J., Chang C.-Y., Cheng C., Teng H. Roles of graphene oxide in photocatalytic water splitting. Mater. Today Chem. 2013;16(3):78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao C.-H., Huang C.-W., Wu J.C. Hydrogen production from semiconductor-based photocatalysis via water splitting. Catalysts. 2012;2(4):490–516. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadeem M.S., Munawar T., Mukhtar F., Batool S., Hasan M., Akbar U.A., Hakeem A.S., Iqbal F. Energy-levels well-matched direct Z-scheme ZnNiNdO/CdS heterojunction for elimination of diverse pollutants from wastewater and microbial disinfection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29(33):50317–50334. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J., Yu J., Zhang Y., Li Q., Gong J.R. Visible light photocatalytic H2-production activity of CuS/ZnS porous nanosheets based on photoinduced interfacial charge transfer. Nano Lett. 2011;11(11):4774–4779. doi: 10.1021/nl202587b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Q., Li L., Xin Z., Yu Y., Wang L., Zhang W. Visible light response and heterostructure of composite CdS@ ZnS–ZnO to enhance its photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2020;813 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bashir S., Jamil A., Alazmi A., Khan M.S., Alsafari I.A., Shahid M. Synergistic effects of doping, composite formation, and nanotechnology to enhance the photocatalytic activities of semiconductive materials. Opt. Mater. Express. 2023;135 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiang W., Zhang Y., Lin H., Liu C.-j. Nanoparticle/metal–organic framework composites for catalytic applications: current status and perspective. Molecules. 2017;22(12):2103. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J., Li L., Du M., Cui Y., Li Y., Yan W., Huang H., Li X.a., Zhu X. Single‐atom phosphorus defects decorated CoP cocatalyst boosts photocatalytic hydrogen generation performance of Cd0. 5Zn0. 5S by directed separating the photogenerated carriers. Small. 2023;19(20) doi: 10.1002/smll.202300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J., Li J., Huang H., Chen W., Cui Y., Li Y., Mao W., Zhu X., Li X.a. Spatial relation controllable di‐defects synergy boosts electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction over VSe2 nanoflakes in all pH electrolytes. Small. 2022;18(47) doi: 10.1002/smll.202204557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui Y., Guo X., Zhang J., Li X.a., Zhu X., Huang W. Di-defects synergy boost electrocatalysis hydrogen evolution over two-dimensional heterojunctions. Nano Res. 2022;15(1):677–684. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain H.M., Fiaz M., Athar M. Facile refluxed synthesis of TiO 2/Ag 2 O@ Ti-BTC as efficient catalyst for photodegradation of methylene blue and electrochemical studies. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2021;18:1269–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safaei M., Foroughi M.M., Ebrahimpoor N., Jahani S., Omidi A., Khatami M. A review on metal-organic frameworks: synthesis and applications. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;118:401–425. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu D., Liu J., Wang L., Du Y., Zheng Y., Davey K., Qiao S.-Z. A 2D metal–organic framework/Ni (OH) 2 heterostructure for an enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Nanoscale. 2019;11(8):3599–3605. doi: 10.1039/c8nr09680e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen H.P., Kim T.H., Lee S.W. Visible light‐driven AgBr/AgCl@ MIL‐101 (Fe) composites for removal of organic contaminant from wastewater. Photochem. Photobiol. C. 2020;96(1):4–13. doi: 10.1111/php.13186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y., Yang Y., Liu Y., Zhao S., Tang Z. Metal–organic frameworks for electrocatalysis: beyond their derivatives. Small Science. 2021;1(12) [Google Scholar]

- 29.He L., Dong Y., Zheng Y., Jia Q., Shan S., Zhang Y. A novel magnetic MIL-101 (Fe)/TiO2 composite for photo degradation of tetracycline under solar light. J. Hazard Mater. 2019;361:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu X., Gao D., Li Y., Dong H., Zhou W., Yang L., Zhang Y. Fabrication of novel CuWO 4 nanoparticles (NPs) for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in aqueous solution. SN Appl. Sci. 2019;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen C., Bi W., Xia Z., Yuan W., Li L. Hydrothermal synthesis of the CuWO4/ZnO composites with enhanced photocatalytic performance, ACS Omega. 2020;5:13185–13195. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c01220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Low J., Jiang C., Cheng B., Wageh S., Al‐Ghamdi A.A., Yu J. A review of direct Z‐scheme photocatalysts. Small Methods. 2017;1(5) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amdeha E., Mohamed R.S. A green synthesized recyclable ZnO/MIL-101 (Fe) for Rhodamine B dye removal via adsorption and photo-degradation under UV and visible light irradiation. Environ. Technol. 2021;42(6):842–859. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2019.1647290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S., Wang C., Liu Y., Liu Y., Cai M., Zhao W., Duan X. S-scheme MIL-101 (Fe) octahedrons modified Bi2WO6 microspheres for photocatalytic decontamination of Cr (VI) and tetracycline hydrochloride: synergistic insights, reaction pathways, and toxicity analysis. J. Chem. Eng. 2023;455 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang C., Wang J., Li M., Lei X., Wu Q. Construction of a novel Z-scheme V2O5/NH2-MIL-101 (Fe) composite photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline. Solid State Sci. 2021;117 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huo Q., Liu G., Sun H., Fu Y., Ning Y., Zhang B., Zhang X., Gao J., Miao J., Zhang X. CeO2-modified MIL-101 (Fe) for photocatalysis extraction oxidation desulfurization of model oil under visible light irradiation. J. Chem. Eng. 2021;422 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hao C.-c., Chen F.-y., Bian K., Tang Y.-b., Shi W.-l. Spindle-like MIL101 (Fe) decorated with Bi2O3 nanoparticles for enhanced degradation of chlortetracycline under visible-light irradiation. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2022;13(1):1038–1050. doi: 10.3762/bjnano.13.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen F., Wang H., Hu H., Gan J., Su M., Xu H., Wei C. Construction of NH2-MIL-101 (Fe)/g-C3N4 hybrids based on interfacial Lewis acid-base interaction and its enhanced photocatalytic redox capability. Colloids Surf., A: Physicochem. Eng. 2021;631 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiaz M., Kashif M., Fatima M., Batool S.R., Asghar M.A., Shakeel M., Athar M. Synthesis of efficient TMS@ MOF-5 catalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Catal. Lett. 2020;150:2648–2659. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charles V., Yang Y., Yuan M., Zhang J., Li Y., Zhang J., Zhao T., Liu Z., Li B., Zhang G. CoO x/UiO-66 and NiO/UiO-66 heterostructures with UiO-66 frameworks for enhanced oxygen evolution reactions. New J. Chem. 2021;45(32):14822–14830. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gecgel C., Simsek U.B., Gozmen B., Turabik M. Comparison of MIL-101 (Fe) and amine-functionalized MIL-101 (Fe) as photocatalysts for the removal of imidacloprid in aqueous solution. J. Iran. Chem. 2019;16:1735–1748. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima A., Costa M., Santos R., Batista N., Cavalcante L., Longo E., Luz G., Jr. Facile preparation of CuWO4 porous films and their photoelectrochemical properties. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;256:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiaz M., Kashif M., Shah J.H., Ashiq M.N., Gregory D.H., Batool S.R., Athar M. Incorporation of MnO 2 nanoparticles into MOF-5 for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Ionics. 2021;27:2159–2167. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiaz M., Kashif M., Majeed S., Ashiq M.N., Farid M.A., Athar M. Facile fabrication of highly efficient photoelectrocatalysts MxOy@ NH2‐MIL‐125 (Ti) for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4(23):6996–7002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shabbir B., Drissi N., Jabbour K., Gassoumi A., Alharbi F., Manzoor S., Ashiq M.F., Alburaih H., Ehsan M.F., Ashiq M.N. Development of Mn-MOF/CuO composites as platform for efficient electrocatalytic OER. Fuel. 2023;341 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shabbir B., Jabbour K., Manzoor S., Ashiq M.F., Fawy K.F., Ashiq M.N. Solvothermally designed Pr-MOF/Fe2O3 based nanocomposites for efficient electrocatalytic water splitting. Heliyon. 2023;9(10) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou S., Wang Y., Zhao G., Li C., Liu L., Jiao F. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B by Z-scheme CuWO 4/gC 3 N 4 heterojunction. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021;32:2731–2743. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salman F., Zengin A., Çelik Kazici H. Synthesis and characterization of Fe 3 O 4-supported metal–organic framework MIL-101 (Fe) for a highly selective and sensitive hydrogen peroxide electrochemical sensor. Ionics. 2020;26:5221–5232. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarwar A., Razzaq A., Zafar M., Idrees I., Rehman F., Kim W.Y. Copper tungstate (CuWO4)/graphene quantum dots (GQDs) composite photocatalyst for enhanced degradation of phenol under visible light irradiation. Results Phys. 2023;45 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kavitha B., Karthiga R. Synthesis and characterization of CuWO4 as nano-adsorbent for removal of Nile blue and its antimicrobial studies. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2020;11:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jatav N., Kuntail J., Khan D., De A.K., Sinha I. AgI/CuWO4 Z-scheme photocatalyst for the degradation of organic pollutants: experimental and molecular dynamics studies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;599:717–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li J., Wang L., Liu Y., Zeng P., Wang Y., Zhang Y. Removal of berberine from wastewater by MIL-101 (Fe): performance and mechanism. ACS Omega. 2020;5(43):27962–27971. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c03422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan D., Chen R., Xiao Z., Wang S. Engineering the electronic structure of Co3O4 by carbon-doping for efficient overall water splitting. Electrochim. Acta. 2019;303:316–322. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J., Cui W., Liu Q., Xing Z., Asiri A.M., Sun X. Recent progress in cobalt‐based heterogeneous catalysts for electrochemical water splitting. J. Adv. Mater. 2016;28(2):215–230. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Navarro R.M., Pena M., Fierro J. Hydrogen production reactions from carbon feedstocks: fossil fuels and biomass. Chem. Rev. 2007;107(10):3952–3991. doi: 10.1021/cr0501994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fabbri E., Habereder A., Waltar K., Kötz R., Schmidt T.J. Developments and perspectives of oxide-based catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014;4(11):3800–3821. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiao D., Chen F., Wang S., Wang Y., Li W., He Q. Preparation and study of photocatalytic performance of a novel Z-scheme heterostructured SnS2/BaTiO3 composite. Vacuum. 2021;186 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu L., Zhang L., Wang F., Qi K., Zhang H., Cui X., Zheng W. Bi-metal–organic frameworks type II heterostructures for enhanced photocatalytic styrene oxidation. Nanoscale. 2019;11(16):7554–7559. doi: 10.1039/c9nr00790c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen H., Leng W., Xu Y. Enhanced visible-light photoactivity of CuWO4 through a surface-deposited CuO. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118(19):9982–9989. [Google Scholar]

- 60.X.-q. Wang, S.-f. Han, Q.-w. Zhang, N. Zhang, D.-d. Zhao. Photocatalytic oxidation degradation mechanism study of methylene blue dye waste water with GR/iTO2. MATEC Web Conf. 2018. EDP Sciences.

- 61.Ding D., Jiang Z., Ouyang Q., Wang L., Zhang Y., Zan L. Enhanced photocatalytic activity and mechanism insight of MnOx/MIL-101. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018;82:226–232. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doan V.-D., Huynh B.-A., Le Pham H.A., Vasseghian Y. Cu2O/Fe3O4/MIL-101 (Fe) nanocomposite as a highly efficient and recyclable visible-light-driven catalyst for degradation of ciprofloxacin. Environ. Res. 2021;201 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.