Abstract

Cyanobacteria are highly abundant in the marine photic zone and primary drivers of the conversion of inorganic carbon into biomass. To date, all studied cyanobacterial lineages encode carbon fixation machinery relying upon form I Rubiscos within a CO2-concentrating carboxysome. Here, we report that the uncultivated anoxic marine zone (AMZ) IB lineage of Prochlorococcus from pelagic oxygen-deficient zones (ODZs) harbors both form I and form II Rubiscos, the latter of which are typically noncarboxysomal and possess biochemical properties tuned toward low-oxygen environments. We demonstrate that these cyanobacterial form II enzymes are functional in vitro and were likely acquired from proteobacteria. Metagenomic analysis reveals that AMZ IB are essentially restricted to ODZs in the Eastern Pacific, suggesting that form II acquisition may confer an advantage under low-O2 conditions. AMZ IB populations express both forms of Rubisco in situ, with the highest form II expression at depths where oxygen and light are low, possibly as a mechanism to increase the efficiency of photoautotrophy under energy limitation. Our findings expand the diversity of carbon fixation configurations in the microbial world and may have implications for carbon sequestration in natural and engineered systems.

Keywords: cyanobacteria, photoautotrophy, Rubisco, carbon fixation, metagenomics

The Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle is the dominant mechanism by which inorganic carbon is fixed biologically on Earth (1). All members of the phylum Cyanobacteria perform the CBB cycle using form I ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) ensconced in a carboxysome, a bacterial microcompartment serving as a CO2-concentrating mechanism. In the ocean, the picocyanobacterial lineages Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus are thought to exclusively employ form IA Rubisco and α-carboxysomes, both of which may have been laterally transferred from proteobacteria (2). Among these groups, little variation within the genetic architecture of the carbon fixation machinery has been observed, despite the existence of numerous ecotypes differentiated by their spatial and metabolic niches (3). Here, we characterize the first known form II Rubisco in Cyanobacteria, found within an abundant Prochlorococcus ecotype from oxygen-deficient zones (ODZs) (4, 5). We also explore the potential ramifications of this gene inventory for the marine carbon cycle.

Results

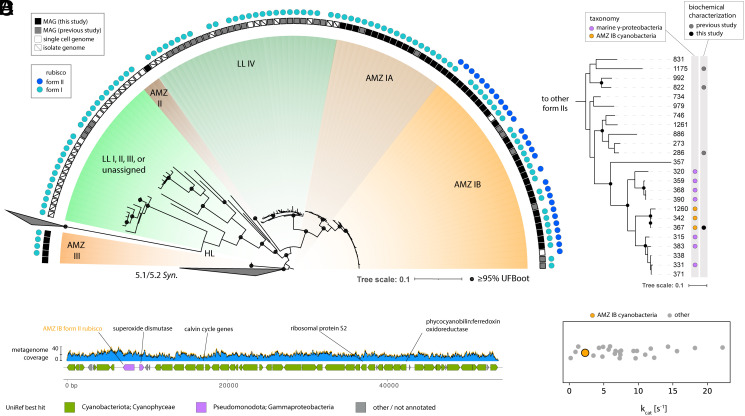

While conducting a metagenomic survey of autotrophic organisms in the marine environment (6), we detected genomic bins from cyanobacteria encoding both form I and form II Rubiscos. Initial phylogenetic reconstructions indicate that these bins fall within the AMZ (anoxic marine zone) lineages of Prochlorococcus, ecotypes recently characterized from single-cell genomes (SAGs) from anoxic seawater (4). To increase genomic sampling of these lineages, we reconstructed 54 new medium-to-high quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from public data. Analysis of the total genome set indicated that only the AMZ IB subclade encoded both the form I and form II Rubiscos in the same MAG and/or SAG (4) (Fig. 1A and Dataset S1). Although a few AMZ IB bins possess only form I or form II, this is likely due to genome incompleteness.

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of cyanobacteria with multiple Rubisco forms. (A) Ribosomal protein tree depicting ODZ Prochlorococcus lineages and their Rubiscos. (B) Form II Rubisco gene tree showing representative AMZ IB sequences and their phylogenetic context. Tree tips are labeled with sequence numbers (Dataset S2). (C) Maximal carboxylation rates (kcat) for form II rubiscos reported in refs. 7 and 8 and the AMZ IB sequence #367 measured in this study. (D) Genomic context of form II Rubisco within an AMZ IB MAG. Blue regions represent metagenomic sequencing coverage.

We next clustered cyanobacterial form II Rubiscos and placed representative sequences into a tree. Sequences formed a monophyletic clade within a larger group mostly derived from marine gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 1B). We inferred that the cyanobacterial sequences were likely functional based on proximity to other biochemically characterized proteins (Fig. 1B) and the presence of all active site residues coordinating substrate binding and catalysis (9, 10) (Dataset S3). To confirm functionality, we heterologously expressed the most common Prochlorococcus form II sequence (#367), demonstrated carboxylation coupled to NADH oxidation (11), and quantified active site concentration using CABP inhibition (SI Appendix, Extended Methods). The maximal carboxylation rate (kcat) was 2.3 ± 0.1 s−1, within the known range for form II Rubiscos (Fig. 1C) (8).

Finally, we examined the genomic context of cyanobacterial form II sequences, finding that they are encoded alongside a superoxide dismutase also of putative gammaproteobacterial origin (Fig. 1D and Dataset S4) and were recovered on distinct scaffolds from form I sequences. No chaperones or regulators were identified in the immediate context. Importantly, the overwhelming cyanobacterial affiliation of genes near the form II—most notably, the ribosomal protein S2—indicate that the presence of form II Rubisco is likely not the result of misbinning; similarly, consistent read coverage indicates that misassembly in this region is unlikely.

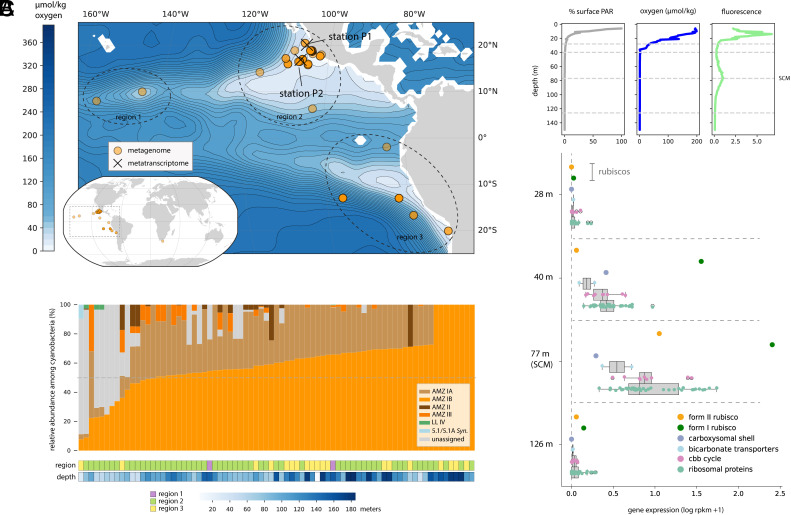

In addition to CO2, Rubisco also reacts promiscuously with oxygen, leading to the loss of up to 25% of fixed carbon through a process termed photorespiration (12). Because form IIs generally possess a lower specificity for CO2 over O2 (SC/O) and are not associated with carboxysomes, they are thought to be preferentially employed in low-oxygen environments (13). Accordingly, we examined the distribution of AMZ IB with form II Rubiscos using a global metagenomic survey. Our analysis detected AMZ IB within nearly 80 samples, essentially restricted to ODZs of the Eastern Pacific (Fig. 2A and Dataset S5). When detected, this lineage typically comprised the majority of the cyanobacterial community (Fig. 2B), consistent with previous results (4, 5).

Fig. 2.

Distribution and expression patterns of AMZ IB Prochlorococcus. (A) Location of metagenomic and metatranscriptomic samples where AMZ IB were detected, overlaid with oxygen concentrations at 125 m. (B) Relative abundance of cyanobacterial ecotypes in metagenomes (≤200 m) containing AMZ IB, based on sequencing coverage of representative genomes. (C) Gene expression patterns at station P1. PAR, photosynthetically active radiation; SCM, secondary chlorophyll max.

Within ODZs, oxygen concentrations, light, and nutrients vary significantly with water depth (5). To examine the impact of these gradients upon the utilization of Rubisco forms, we leveraged a metatranscriptomic transect from an offshore ODZ near Mexico (P1, Fig. 2A) (14). Alignment of transcripts to a representative genome suggested that AMZ IB was only active in the lower euphotic zone of the ODZ (Fig. 2C). Form I Rubisco was highly expressed at 40 and 77 m, whereas form II was essentially only expressed at 77 m (anoxic SCM, ~0.01% surface PAR), where it attained ~4% of form I levels. Trends were similar at another site (P2) with a more gradual oxycline and deeper SCM, though relative expression of the form II was higher (~16% of form I at the SCM) (Fig. 2A and Dataset S6). Additionally, we detected 10 peptides identical to the predicted AMZ IB form II sequence in a metaproteome previously collected at P2 (5) (Dataset S7). These peptides were only recovered at 100 m, near the top of the SCM.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that an abundant lineage of Cyanobacteria from ODZs uncharacteristically encodes both form I and form II Rubiscos. While known within marine proteobacteria, this genetic repertoire has not before been observed in Cyanobacteria, Earth’s most numerous bacterial primary producers. In proteobacteria, form II Rubiscos are noncarboxysomal and can be preferentially transcribed under low-oxygen conditions that theoretically favor their biochemical attributes (15). Thus, we propose that the acquisition of the form II Rubisco by AMZ IB—likely from co-occurring gammaproteobacteria—represents an adaptation to low oxygen (and often, elevated CO2) niches within ODZs. This gene, alongside others related to anaerobic stress tolerance and signaling (4), may permit AMZ IB to flourish in the measurably anoxic waters of the euphotic zone.

At this stage, the physiological impact of simultaneous Rubisco expression in AMZ IB is unclear. One possibility is that tandem expression permits cells to fix additional CO2, including that leaked from the carboxysome associated with their form IA Rubisco. We speculate that the energetic cost associated with carboxysome production may be particularly burdensome at depths where light/energy is limited and thus that a noncarboxysomal form might be particularly advantageous there. Tandem expression of both forms could also result from a dependence of the form II Rubisco upon form I-associated chaperones or regulators.

Together, our results demonstrate a unique metabolic configuration with the potential to impact carbon cycling in ODZs, significant and expanding portions of the world’s oceans. Additionally, our findings raise the intriguing possibilities that carbon fixation genes may be more mobile and modular than previously recognized and that harboring multiple forms of Rubisco might be a viable strategy toward increasing carbon fixation efficiency in both natural and engineered systems.

Materials and Methods

We created a genomic database to examine the distribution of Rubisco genes within AMZ cyanobacteria. To expand sampling of these lineages, a targeted metagenomics effort was undertaken using publicly available data. All phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using appropriate references and maximum-likelihood methods. The distribution and gene expression patterns of AMZ IB were generated through read-mapping of public metagenomic and metatranscriptomic datasets to a representative genome followed by normalization for sequencing effort and gene length. Measurement of Rubisco kinetics and modeling was performed using published methodology. Details are available in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S1-6 (XLSX)

Dataset S7 (FASTA)

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Rathwell, Natalie Kellogg, Alex Roberts, Luis Valentin-Alvarado, and Matthew Olm. Funding was provided by the Stanford Science Fellows (A.L.J.), NSF Ocean Sciences Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (A.L.J.), NSF award OCE-2143035 (A.E.D.), NSF award OCE-2022911 (G.R.), and Simons Foundation Award 561645 (J.Y.).

Author contributions

A.L.J., J.Y., G.R., and A.E.D. designed research; A.L.J., K.H., R.Z.W., L.J.T.-K., N.J., and G.R. performed research; A.L.J., K.H., R.Z.W., L.J.T.-K., N.J., and G.R. analyzed data; and A.L.J., K.H., R.Z.W., L.J.T.-K., N.J., N.P., P.M.S., J.Y., G.R., and A.E.D. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Contributor Information

Alexander L. Jaffe, Email: ajaffe@stanford.edu.

Anne E. Dekas, Email: dekas@stanford.edu.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Underlying data are available in SI Appendix and NCBI (PRJNA1136951). Custom code is available at github.com/alexanderjaffe/odz-pros. Previously published data were used for this work (16–21).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Bar-On Y. M., Milo R., The global mass and average rate of rubisco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 4738–4743 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess W. R., et al. , The photosynthetic apparatus of Prochlorococcus: Insights through comparative genomics. Photosynth. Res. 70, 53–71 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biller S. J., Berube P. M., Lindell D., Chisholm S. W., Prochlorococcus: The structure and function of collective diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 13–27 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ulloa O., et al. , The cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus has divergent light-harvesting antennae and may have evolved in a low-oxygen ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2025638118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchsman C. A., et al. , Cyanobacteria and cyanophage contributions to carbon and nitrogen cycling in an oligotrophic oxygen-deficient zone. ISME J. 13, 2714–2726 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe A. L., Salcedo R. S. R., Dekas A. E., Abundant and metabolically flexible lineages within the SAR324 and gammaproteobacteria dominate the potential for rubisco-mediated carbon fixation in the dark ocean. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2024). 10.1101/2024.05.09.593449 (Accessed 10 May 2024). [DOI]

- 7.Flamholz A. I., et al. , Revisiting trade-offs between Rubisco kinetic parameters. Biochemistry 58, 3365–3376 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidi D., et al. , Highly active rubiscos discovered by systematic interrogation of natural sequence diversity. EMBO J. 39, e104081 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleland W. W., Andrews T. J., Gutteridge S., Hartman F. C., Lorimer G. H., Mechanism of Rubisco: The carbamate as general base. Chem. Rev. 98, 549–562 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabita F. R., et al. , Function, structure, and evolution of the RubisCO-like proteins and their RubisCO homologs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 576–599 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lilley R. M., Walker D. A., An improved spectrophotometric assay for ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 358, 226–229 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludwig L. J., Canvin D. T., The rate of photorespiration during photosynthesis and the relationship of the substrate of light respiration to the products of photosynthesis in sunflower leaves. Plant Physiol. 48, 712–719 (1971). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badger M. R., Bek E. J., Multiple Rubisco forms in proteobacteria: Their functional significance in relation to CO2 acquisition by the CBB cycle. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1525–1541 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattes T. E., Susan B., Rocap G., Morris R. M., Two metatranscriptomic profiles through low-dissolved-oxygen waters (DO, 0 to 33 µM) in the Eastern Tropical North Pacific Ocean. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 11, e0120121 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Léniz B., Murillo A. A., Ramírez-Flandes S., Ulloa O., Diversity and transcriptional levels of RuBisCO form II of sulfur-oxidizing γ-Proteobacteria in coastal-upwelling waters with seasonal Anoxia. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 213 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang I. H., et al. , Partitioning of the denitrification pathway and other nitrite metabolisms within global oxygen deficient zones. ISME Commun. 3, 76 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beman J. M., et al. , Substantial oxygen consumption by aerobic nitrite oxidation in oceanic oxygen minimum zones. Nat. Commun. 12, 7043 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchsman C. A., Cherubini L., Hays M. D., An analysis of protists in Pacific oxygen deficient zones: Implications for Prochlorococcus and N2 -producing bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 24, 1790–1804 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuchsman C. A., Devol A. H., Saunders J. K., McKay C., Rocap G., Niche partitioning of the N cycling microbial community of an offshore oxygen deficient zone. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertagnolli A. D., Konstantinidis K. T., Stewart F. J., Non-denitrifier nitrous oxide reductases dominate marine biomes. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 12, 681–692 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sunagawa S., et al. , Ocean plankton. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 348, 1261359 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S1-6 (XLSX)

Dataset S7 (FASTA)

Data Availability Statement

Underlying data are available in SI Appendix and NCBI (PRJNA1136951). Custom code is available at github.com/alexanderjaffe/odz-pros. Previously published data were used for this work (16–21).