Abstract

Introduction

This systematic review is the first step in the process of standardizing outcome reporting through the development of a core outcome set for research on critically ill obstetric patients (COSCO).

Methods

A five-database search was performed to identify randomized and non-randomized studies published before November 2017, on patients admitted to intensive care or high-dependency units during or immediately after pregnancy. Reported outcomes were categorized into domains and definitions were documented.

Results

Of the 12,581 citations reviewed, 136 studies were included. The most reported outcome domains were maternal all-cause mortality (n = 128, 94.5%), resource use (n = 116, 85.6%), and clinical/physiological outcomes (n = 111, 82.8%). Outcomes related to functioning/life impact and adverse effects of treatment were only reported in four (2.9%) studies. There was inconsistency in outcome definitions.

Conclusions

This review identified considerable variation in outcome reporting and definitions and generated an outcome list to consider in COSCO development.

Keywords: Systematic review, critically ill obstetrics patients, core outcome set

Background

It is estimated that maternal critical illness affects 0.7 to 13.5 out of 1000 pregnancies. 1 Although critical illness in pregnancy accounts for a small proportion of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, it is associated with high maternal and fetal mortality.1–3 Young and healthy individuals may experience a sudden deterioration of their existing health conditions due to their pregnancy status or may encounter significant complications without any preceding comorbidities. It is therefore concerning that an overall increase in severe maternal morbidity (SMM) is detected in Canada (13.9 to 16.1 per 10,000 births) 4 and in the United States (14.7 to 18.0 per 10,000 hospital discharges). 5

Management of critically ill pregnant individuals presents significant challenges owing to changes in maternal physiology, potential fetal effects of medical interventions, and psychosocial issues. 6 Additionally critically ill pregnant women have been excluded or underrepresented in most interventional trials involving ICU patients. 7 Evaluation of interventions is based on observational data, but synthesis of data and meta-analysis highly depends on standardization of study methods and outcomes. 8 Improvement of research in this field will involve inclusion of pregnant women in clinical trials and the conduct of multicenter studies using standardized outcomes important to stakeholders. The process of standardization of outcome reporting and measurement is achieved through the development of a core outcome set—a standardized set of outcomes developed through consensus involving patients and relevant stakeholders. 9

This systematic review aims to generate a list of outcomes for the development of a core outcome set in critically ill obstetric patients (COSCO) and to evaluate the discrepancy in outcome and definition reporting.

Material and methods

The study protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO 2017 (CRD42017071944) 10 and has been conducted and reported following preferred reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 11

Data sources and searches

A comprehensive electronic search of the literature was designed and conducted by a medical information specialist in MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and the Joanna-Briggs Database of Systematic Reviews for articles published from inception to November 2017. The search strategy included keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms related to our population of interest such as obstetrics, pregnancy, intensive care, critical care, severe obstetric morbidity, severe acute maternal morbidity, postnatal morbidity, near miss and SMM (Supplemental data 1). The search was limited to articles written in English. The references of eligible studies were examined for additional publications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Randomized clinical trials and non-randomized studies including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control, case series studies, and systematic reviews on women admitted to intensive care or high-dependency units during or immediately after pregnancy were included. Letters, commentaries, editorials, narrative reviews, and case reports were excluded. Cochrane checklist was used for the assessment of non-randomized studies to categorize non-randomized study designs. 12

Studies were considered eligible if they described admission in the antepartum or postpartum period within 6 weeks in an ICU or high-dependency unit. Articles relating to neonatal mechanical ventilation or mechanical ventilation provided only for surgery (e.g. cesarean) were excluded. Mechanical ventilation for chronic respiratory disease, trophoblastic pregnancies, or brain death was also excluded. Supplemental Data 2 describes the full inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (JVL and JK) independently screened the titles/abstracts and full texts for study eligibility using Covidence software. 13 Any discrepancy during the screening was resolved through mutual discussion and adjudication by a third reviewer (SEL). Two reviewers (JVL and JK) extracted data from included studies including study design, number of included subjects, reported outcomes, and their definitions.

Data synthesis and analysis

Outcomes were categorized into core areas: mortality, physiological outcomes, functioning, adverse effects, and resource use, based on a previously published taxonomy. 14 Frequency of reporting of each outcome and their definitions were analyzed.

Results

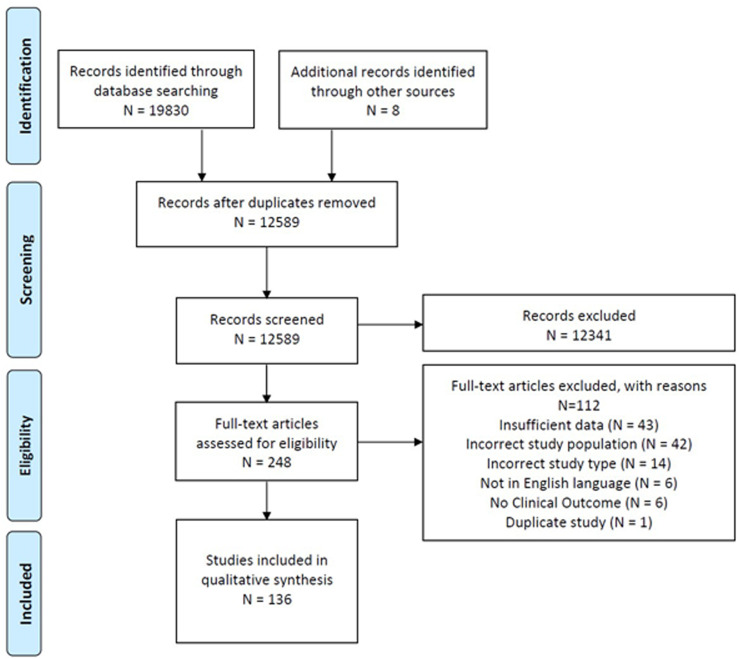

The search identified 12,581 titles and abstracts after the removal of duplicates and eight additional articles were found after screening the reference lists. Of these, 136 published studies that reported on 10,109 pregnant or postpartum individuals admitted to critical care, met the inclusion criteria and were included (Figure 1—PRISMA diagram). Characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Supplemental Data 3. Of these, 121 were cohort studies, 11 were case-control studies, two were systematic reviews, and two were cross-sectional studies (of which one was a qualitative study). Included studies were conducted in 39 different countries from six continents including high- and low-and-middle-income countries and 27 (19.8%) were multicenter. The countries from which most publications were published included the USA (n = 21), India (n = 18), the UK (n = 9), and Canada (n = 6). Sample sizes ranged from 15 to 158,410, with a median of 108 and an interquartile range of 247.5. Excluded articles are listed in Supplemental Data 4.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

The studies reported 18 outcomes, which are summarized in Table 1. Across the five core areas (mortality/survival, physiological/clinical, functioning/life impact, adverse events, and resource use) from the Williamson/Clarke revised taxonomy, 14 there were appreciable differences observed in the number of outcomes falling under each core area and the extent to which each was studied in the literature. Most of the studies reported mortality/survival (128 out of 136, 94.1%) and resource use (116 out of 136, 85.2%). Maternal, fetal/neonatal, and obstetric outcomes under the clinical/physiological core area were reported in 111 out of 136 studies (81.6%), while the functioning core area which includes domains such as social or emotional functioning, delivery of care, perceived health status and the adverse events core area were only represented in four studies (2.9%), with no study reporting on delivery of care patient satisfaction or emotional functioning and well-being. Health-related quality of life was only reported in one study. Mother–newborn separation was reported in two studies. With respect to maternal resource use, the length of ICU/high-dependency unit stay was reported in 70.5% of studies, and specific interventions were reported in 58.8% of the studies, while the length of hospital stay was reported in 14.7%. Costs were only considered in two studies.

Table 1.

All reported outcomes based on the Williamson/Clarke (revised) taxonomy.

| Core areas | Domains | Outcomes | Definition/descriptors (when provided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality/survival | Mortality/survival (n = 128) | Maternal mortality |

|

| Clinical/physiological | General outcomes (n = 23) | Organ dysfunction |

|

| Pregnancy, puerperium, and perinatal outcomes (n = 88) | Offspring mortality |

|

|

| Offspring morbidity |

|

||

| Preterm delivery |

|

||

| Birthweight |

|

||

| Mode of delivery |

|

||

| Hysterectomy |

|

||

| Functioning/life impact | Physical functioning (n = 4) | Physical functioning |

|

| Mother's experiences of critical care |

|

||

| Role functioning | Mother–newborn separation |

|

|

| Quality of life | Health-related quality of life |

|

|

| Adverse events | Adverse events (n = 4) | Complications |

|

| Resource use | Hospital (n = 116) | Length of stay |

|

| Readmission to ICU |

|

||

| Cost of ICU admission |

|

||

| Specific interventions |

|

HDU: high-dependency unit; ICU: intensive care unit; MSOF: multiple system organ failure; MODS: multiple organ dysfunction score; SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment; IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction; NICU: neonatal ICU.

There was high heterogeneity in outcome definitions. “Maternal All-Cause Mortality” reported in the studies varied from “Death in ICU, (24/128, 18.7%),” “Death during hospital stay, (8/128, 6.2%),” “All cause death within 42 days (7/128, 5.4%),” “All cause death within 56 days, (1/1287.8%),” “All cause death within 90 days, (1/1280.7%),” or “1 year postpartum, (2/128, 1.5%).” In 85 out of 128 studies (66.4%), the time point of maternal mortality was unclear. Similarly among the physiological/clinical outcome's core area, the outcomes varied considerably in definitions often not in keeping with definitions recommended by, for example, the World Health Organization. 15 For example, neonatal mortality was variably defined as a postnatal loss in the first to 28 days of life or up to 8 weeks of life. Perinatal mortality was similarly defined as the loss of a fetus or neonate in utero to 28 days, 6 weeks, or 1 year after birth. Thresholds for preterm birth varied from under 27 weeks to under 36 weeks. Birthweight was not inconsistently defined, with terms such as “small for gestational age,” “intrauterine growth restriction,” and “low/very low birthweight” without clear definitions.

Discussion

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative 9 defines an outcome in the context of healthcare, which serves to assess the impact of a treatment considering its benefits and risks. In clinical practice, the provision of care should align with outcomes that patients deem significant. In research, outcomes play a crucial role in determining sample sizes and evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention. Precisely defining and measuring outcomes are essential for conducting meta-analyses, which subsequently influence clinical practices, health policies, and funding decisions, thereby impacting patient care. Particularly for COSCO, whose incidence is fortunately rare, it becomes imperative that researchers worldwide consistently report and measure outcomes that are valued by patients and stakeholders involved in their care. This led to the establishment of core outcome sets, which are supported by initiatives such as COMET 16 and Outcome Reporting in Obstetric Studies (OROS). 17 The creation of a core outcome set for studies involving critically ill obstetrics patients is currently underway as part of the OROS project.

This systematic review, which identified all outcomes documented in 136 studies, marks the initial step in its development process. It identified considerable variation in the reported outcomes including inconsistencies in outcome definitions across studies and variation in timing of outcome measurement. These identified issues present various challenges for clinicians and researchers alike for interpretation of results and make comparison of study results challenging. For example, differences in the timing of outcome measurement lead to an inability to pool results and generate meta-analyses. This variation was prominently seen with regard to maternal mortality, offspring mortality, mode of delivery, and fetal growth.

An important part of conditions of satisfaction development is to include patient-important outcomes such as those within the functioning domain. Critically ill pregnant patients can often experience long-lasting impacts on their emotional, social, and role functioning and these outcomes were poorly represented in our systematic review. The development of COSCO involves patients and patients’ family interviews to identify these patients' important outcomes.

Our study has several strengths. This study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in critical care, obstetrics, systematic reviews, and core outcome set methodology. Also, we included all studies regardless of quality assessment, acknowledging that critical illness in pregnancy is rare and some study types such as case reports, case series, and qualitative research studies that involve small numbers of patients might still report on important outcomes to consider for future research. Quality of the outcome reporting or risk-of-bias assessment of the included studies was not conducted for two reasons. First, there is no validated risk-of-bias assessment tool for systematic reviews of studies aimed primarily at outcome reporting. 18 Second, the aim of the study was to include all published outcomes and definitions regardless of the risk of bias, to get a full understanding of what outcomes have been reported in the literature. This is in keeping with other systematic reviews performed for the development of core outcome sets. 19

This work also has limitations. First, the systematic review was completed in 2018 and publication was delayed initially, as the authors pursued the subsequent steps of COSCO and later, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. An update of the search was not completed and many studies on maternal critical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic are therefore not included. Although this may affect the validity of this systematic review, we sought to demonstrate variation in outcome reporting and use a literature review only as the first step in developing COSCO. Critical care during the COVID-19 pandemic reflected an exceptional situation with public health and other influences, which are perhaps not representative of ongoing and future studies on critically ill pregnant patients. It is unlikely that additional generalizable outcomes would be identified by a review of these studies. The second major limitation is that only English-language studies were included, which might have excluded additional qualitative studies that might have reported patient-important outcomes. We have since completed an international qualitative study that identified these outcomes. 20

Conclusion

This systematic review identified a list of outcomes regarding critical illness during pregnancy, and considerable variation in their reporting and definition. These outcomes along with others obtained from stakeholder interviews form an essential step towards the development of COSCO.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research is funded by the CHEST Foundation Research Grant in Women's Lung Health. Dr Rohan D'Souza is the recipient of a Tier II Canada Research Chair in maternal health [2021-00337].

Ethical approval: This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed consent: Not applicable.

Guarantor: SL.

Contributorship: Study conception and design: SEL, JVL, and RD; development and execution of search strategy: DH; data screening and extraction: JK and JVL; draft manuscript preparation: MT, RA, and RD. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. All contributors are acknowledged as contributing authors and approved manuscript submission.

ORCID iDs: Julien Viau-Lapointe https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4288-2673

Rizwana Ashraf https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5287-0273

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Pollock W, Rose L, Dennis CL. Pregnant and postpartum admissions to the intensive care unit: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36: 1465–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guntupalli KK, Hall N, Karnad DR, et al. Critical illness in pregnancy: Part I: An approach to a pregnant patient in the ICU and common obstetric disorders. Chest 2015; 148: 1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trost S, Beauregard J, Chandra G, et al. Pregnancy-related deaths: Data from maternal mortality review committees in 36 US states, 2017–2019. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html (accessed 26 February 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dzakpasu S, Deb-Rinker P, Arbour L, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada: Temporal trends and regional variations, 2003-2016. J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 41: 1589–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink DA, Kilday D, Cao Z, et al. Trends in maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity during delivery-related hospitalizations in the United States, 2008 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6: e2317641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaffney A. Critical care in pregnancy – is it different? Semin Perinatol 2014; 38: 329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhame I, D'Souza R, Cheng MP. The moral imperative to include pregnant women in clinical trials of interventions for COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173: 836–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chess LE, Gagnier JJ. Applicable or non-applicable: investigations of clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016; 16: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET handbook: Version 1.0. Trials 2017; 18: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viau-Lapointe J, Twin S, Kfouri J, et al. Outcomes reported in studies on critically ill pregnant and postpartum women: A systematic review. PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017071944 2017. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017071944 (accessed 26 March 2024).

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff Jet al. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, et al. Chapter 24: Including non-randomized studies on intervention effects. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. (eds). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2019, pp.595–620. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. https://www.covidence.org.

- 14.Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, et al. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 96: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Maternal deaths. https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/4622 (accessed 30 August 2024).

- 16.COMET-Initiative. Core outcome measures in effectiveness trials 2011. https://comet-initiative.org/ (accessed 5 April 2024).

- 17.OROS-Project. Outcome reporting in obstetric studies, https://oros-project.com/ (2019, accessed 5 April 2024).

- 18.Duffy JMN, Hirsch M, Gale C, et al. A systematic review of primary outcomes and outcome measure reporting in randomized trials evaluating treatments for pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017; 139: 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villani LA, Pavalagantharajah S, D’Souza R. Variations in reported outcomes in studies on vasa previa: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020; 2: 100116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viau Lapointe J, Juando-Prats C, Zapata R, et al. Patient reported outcomes in research on critically ill obstetric patients. Obstet Med 2024. Published online October 16, 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-obm-10.1177_1753495X241302848 for Outcome reporting in studies on critically ill obstetric patients: A systematic review by Julien Viau-Lapointe, Julia Kfouri, Mary Thompson, Rizwana Ashraf, Rohan D’Souza and Stephen Lapinsky in Obstetric Medicine