Abstract

Sexual minority individuals experience barriers to receiving equitable healthcare. Research also indicates that young men who have sex with men (YMSM), particularly young men of color, have limited engagement in the HIV Care Continuum and there are significant disparities across the continuum. This study aims to uncover how providers can engage YMSM of color in all forms of care, including primary care and HIV prevention through an HIV Prevention Continuum. This qualitative study reports data from the Healthy Young Men’s Cohort Study; a total of 49 YMSM participated in the eight focus groups. This study provides a description of YMSM’s overall health concerns, experiences with healthcare, and under what circumstances YMSM seek care. We then present a model describing the salient characteristics of a HIV Prevention Continuum for YMSM of Color and provides clear areas for education, intervention, and policy change to support better overall health for YMSM of color.

Keywords: Young men who have sex with men, HIV/AIDS, access to care, HIV prevention

Sexual minority individuals experience significant barriers to receiving equitable health care (Dean et al., 2000; Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian, 2011; Mayer et al., 2008; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Currently, there is a dearth in knowledge about how young men who have sex with men (YMSM) – a sexual minority group with some of the most striking health disparities - access and engage in care. Importantly, research has shown that nationally, YMSM, particularly young men of color, are the only demographic group that has experienced an increase in rates of HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). The research also indicates that YMSM’s – as well as other adolescents and young adults’ - engagement in the HIV Care Continuum (e.g., testing, linkage to care, retention in care, adherence) is lacking, and there are significant disparities across the continuum. It is estimated that only 40% of youth who are infected with HIV are aware of their diagnosis; 25% are linked to care; 11% are retained in care and only 6% are virally suppressed (Zanoni & Mayer, 2014).

Apart from HIV, the literature is also clear that YMSM experience adverse physical health, mental health, and sexual health outcomes (Halkitis & Figueroa, 2013; McGarrity, 2014; Storholm et al., 2013). However, it is unclear how YMSM access and engage in healthcare, an important support system that has proven to be helpful in identifying at-risk behaviors among young people and connecting them to treatment and services that help reduce or prevent negative health outcomes (Irwin, Adams, Park, & Newacheck, 2009; Ozer, Urquhart, Brindis, Park, & Irwin, 2012). Although there have been studies that have shed some light on the healthcare experiences of sexual minority youth, which includes YMSM, no prior study has explored YMSM’s general healthcare experiences from the unique perspective of YMSM themselves. This is an important step as one cannot fully consider how to better engage YMSM in the HIV care continuum without first understanding what facilitates and impedes access to care more generally. This study aims to describe YMSM’s experiences with and perceptions of healthcare (both primary care and HIV prevention) in order to more fully develop and utilize an HIV Prevention Continuum.

While adolescence and young adulthood are generally one of the healthiest periods in one’s life, youth between the ages of 16 and 24 face major public health concerns such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs), mental health disorders, substance use, violence, and access to healthcare (W.K. Kirzinger, Cohen, & Gindi, 2012; W. K. Kirzinger, Cohen, & Gindi, 2013; Park, Mulye, Adams, Brindis, & Irwin, 2006; Park, Scott, Adams, Brindis, & Irwin, 2014). When examining trends over time, data show that many of these concerns have not improved throughout the past five to ten years— and in some cases such as violence and suicidality, these concerns have worsened (Mulye et al., 2009; Park et al., 2006; Park et al., 2014). YMSM are oftentimes at even greater risk for these same public health concerns. In particular, intimate partner violence (Freedner, Freed, Yang, & Ausin, 2002; Kubicek & McNeeley, 2015); gay-related physical violence from families, peer, or strangers (Hunter, 1990); sexual violence and victimization (Balsam, Beauchaine, Mickey, & Rothblum, 2005; Koblin et al., 2006); substance and alcohol use (Newcomb, Birkett, Corliss, & Mustanski, 2014; Swann, Bettin, Clifford, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2017; Wong, Weiss, Ayala, & Kipke, 2010); and depression and suicide (Allen & Glicken, 1996; Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Garcia, Adams, Friedman, & East, 2002; Gibson, 1989; Kipke et al., 2007; Koblin et al., 2006; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010; Mustanski, Garofalo, Herrick, & Donenberg, 2007) all disproportionately affect YMSM and other sexual minority youth today.

Given these health risks, it is imperative that YMSM engage in the health care system in order to receive relevant physician screenings and advice about health risks and prevention. Unfortunately, young people ages 15 to 24 have the lowest utilization of medical services compared to all other age groups (A. B. Bernstein et al., 2003) despite findings that show primary care settings are effective in identifying at-risk behaviors among youth and engaging them in treatment and services (Mitchell, Ybarra, Korchmaros, & Kosciw, 2014; Webb, Kauer, Ozer, Haller, & Sanci, 2016). Barriers to healthcare that all young people experience include structural barriers (e.g., cost, long visits, confidentiality); social barriers (e.g., stigma of being seen by community members, developmentally appropriate provider interactions); and personal barriers (e.g., perceived needs, self-assessments, fear/anxieties about HIV and STI testing, mistrust of providers, lack of health literacy, limited intergenerational knowledge about the healthcare system) (Marcell et al., 2017; Raymond-Flesch, Siemons, Pourat, Jacobs, & Brindis, 2014).

Among sexual minority individuals more broadly, there is research that shows they are significantly more likely to delay or avoid necessary medical care compared to heterosexuals (Krehely, 2009). In a recent study that used a national sample of sexual minority youth, young men had 2.72 times the risk of reporting unmet medical needs in the past year when compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Luk, Gilman, Haynie, & Simons-Morton, 2017). This finding supports a 2015 study in which approximately half of the YMSM in the sample did not see a medical provider in the past year for a routine physical or check-up, with Latino YMSM reporting a significantly lower percentage of medical care access (Meanley et al., 2015). Moreover, in 2011, Williams and Chapman (2011) found that sexual minority adolescents reported higher rates of unmet medical needs and were more likely to forgo medical care because they were worried about their parents finding out and/or afraid of what a doctor would say or do during a medical appointment.

In particular, research suggests that YMSM are in need of mental health services. Despite the higher rates of anxiety, depression, suicide, and victimization when compared to heterosexual male peers, YMSM report higher rates of unmet mental health needs (Williams & Chapman, 2011). This lack of mental health service engagement supports a 2008 study on mental health engagement among YMSM and adult MSM where YMSM (ages 16 to 25) were more likely to report depressive symptoms, heavy alcohol use, and drug use; YMSM were also less likely to report the use of counseling or medication for psychiatric conditions (Salomon et al., 2008).

The few studies that have explored health care experiences among YMSM examined factors influencing sexual minority youth’s healthcare preferences. A study on sexual minority youth in the United States and Canada found that youth placed as much importance on healthcare provider qualities and interpersonal skills—such as honesty, respect, and a non-judgmental demeanor—as the provider’s competency in providing medical care (Hoffman, Freeman, & Swann, 2009). Research conducted with African American YMSM and transgender youth in the House and Ball communities found that youth were not accessing care because of costs, lack of transportation, and fear and avoidance of difficult conversations with providers (Rowan, DeSousa, Randall, White, & Holley, 2014).

Access to health care is particularly important for YMSM who are living with HIV. Youth, in general, who delay seeking care for an HIV infection after a positive test result, are at high risk for dropping out of HIV care, and have poor adherence to antiretroviral regiments (Hightow-Weidman, Jones, Phillips Ii, Wohl, & Giordano, 2011; Wohl et al., 2011). Additionally, among a national sample of 15–22 year old YMSM living with HIV, only 15% were receiving HIV medical care and 8% were on antiretroviral medications (Valleroy et al., 2000; Wohl et al., 2011).

Penchansky and Thomas’s theory (1981) provides a useful definition that incorporates various dimensions of access to care as they relate to patients providers and resources. They defined access as the degree of fit between the consumer and the service; the better the fit, the better the access. Access is optimized by accounting for each of the following dimensions: accessibility (e.g., location); availability (e.g., sufficient services based on need); acceptability (e.g., attitudes of consumers/providers regarding characteristics of service and providers); affordability (e.g., direct costs of service); and adequacy/accommodation (e.g, hours, referrals). The dimensions of access are independent yet interconnected and each is important to assess the achievement of access. More recently, Saurman (2016) modified this theory to include, awareness (e.g., marketing, communications). This is a useful tool in which to view the current study as we examine the varying experiences of accessing care among an often underserved and vulnerable community.

Without understanding the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes that YMSM have about the health care system more generally, it is impossible to develop effective interventions that will increase YMSM’s engagement in care, a critical relationship that not only supports prevention for HIV-negative YMSM, but also the health, wellbeing, and longevity of YMSM who are currently living with HIV. Therefore, using this modified Penchansky and Thomas model, we describe YMSM’s access to and perceptions of care to identify the principal components of an HIV prevention continuum for YMSM’s regular and ongoing access to care.

Methods

Study Sample and Sampling Design

This manuscript explores qualitative data that were collected as part of the Healthy Young Men’s Cohort Study conducted in Los Angeles County (N=448); data were collected between January and March 2016. Individuals were eligible to participate in the study if they were: ages 16 to 24 years; assigned a male sex at birth; self-identified as gay, bisexual, or uncertain about their sexual orientation; reported a sexual encounter with a male within the previous 12 months; self-identified as Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, or multi-ethnic; and lived in the Los Angeles metro area. In addition, we purposively recruited 51 HIV-positive participants into the Cohort. Participants were recruited using social media (73%), venue-based sampling at public venues (e.g. bars/clubs, Pride and other community events) (16%), and through friend referral (11%). Additional information about the study design and methods are described elsewhere (Kipke et al., 2019). All procedures were approved by the institution’s Institutional Review Board of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Young men were recruited into the focus groups from the larger HYM cohort. They were randomly selected from the cohort rosters and invited to participate in this additional research activity. Young men identified in this way were contacted and the study team explained the focus group topic and its procedures. Young men verbally agreed to participate prior to arriving at the focus group. A total of 49 YMSM participated in the eight focus groups. Table 1 provides a description of each focus group’s participants.

Table 1.

HYM 2.0 Cohort Demographics (N=449)

| Variable | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 16–17 years | 13 (3) |

| 18–20 years | 114 (25) | |

| 21–24 years | 322 (72) | |

| Race | Black | 9 (21) |

| Latino | 264 (59) | |

| Multi-racial | 90 (20) | |

| Food Security | Food secure | 285 (64) |

| Food insecure | 109 (24) | |

| Hunger | 55 (12) | |

| Residence | Family | 212 (47) |

| Own place/apartment | 154 (34) | |

| With friends/partner | 41 (9) | |

| No regular place/other | 42 (10) | |

| Employment | In school | 75 (17) |

| In school, employed | 138 (31) | |

| Employed, not in school | 154 (34) | |

| Not employed, not in school | 73 (16) | |

| Sexual Identity | Gay | 335 (75) |

| Other same-sex identity | 20 (4) | |

| Bisexual | 74 (16) | |

| Straight | 1 (.2) | |

| Other (e.g., pansexual) | 19 (4) | |

| Sexual Attraction | Males only | 199 (44) |

| Males and females | 247 (55) | |

| Females only | 1 (.2) | |

| Don’t know | 2 (.4) | |

| HIV Serostaus | Positive | 52 (12) |

The focus group discussion guide was designed to gather in-depth information on young men’s experiences with healthcare, barriers and facilitators to accessing care, primary health concerns and experiences in accessing care. Each focus group lasted 1.5–2 hours and was digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Eight focus groups were conducted either at the HYM project offices (n=5) or at the offices of one of our community partners (n=3). Informed consent for focus group participants was obtained prior to beginning the study activities. The informed consent was explained to the young men in a group setting and the study team checked with each participant individually to address questions or concerns. Respondents were provided a $35 incentive for completing the focus group.

Analysis

The qualitative analysis for this manuscript utilized a “constant comparative” approach, an aspect of grounded theory that entails the simultaneous process of data collection, analysis and description. In this process, data are analyzed for patterns and themes to discover the most salient categories, as well as any emergent theoretical implications (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). As the data are collected, they are immediately analyzed for patterns and themes, with a primary objective of discovering theory implicit in the data. Focus group transcripts were included in the analysis and MAXQDA was used for coding and analysis of relationships between and within text segments.

Members of the research team reviewed an initial sample of 15% of the transcripts to identify key themes, which formed the basis of the project codebook. Codes focusing on a range of topics were identified and defined based on the key constructs included in the discussion guide. The codebook was modified as needed, and once finalized, two members of the research team were responsible for coding the interviews. To establish the coding system, 15% of the transcripts were double-coded. Inter-coder reliability was assessed through MAXQDA’s calculation and differences in coding were discussed and resolved by the team until an alpha of .80 was achieved. The open coding process included refining codes based on the data. Codes related to health concerns, experiences with healthcare, family history with healthcare and barriers to care were included in the current analysis. This process led to the structure of the present study which provides a description of YMSM’s overall health concerns, their experiences with healthcare as children and young adults, and under what circumstances YMSM seek medical care. The codes were placed into a model that describes the salient characteristics that feed into a HIV Prevention Continuum for YMSM of Color.

In addition, using a version of a grounded theory approach to the analysis, allows one to discover emerging patterns in data with goal being to a research method that will enable you to develop a theory which offers an explanation about the main concern of the population within the area of inquiry and how that concern is resolved or processed. As we mapped the identified concepts related to health care access a model related to access to care for YMSM of color emerged. A literature review of how others have conceptualized access to care led to the identification of the Penchansky and Thomas model (Penchansky & Thomas, 1981) which seemed to reflect the data in our own study (with some modifications as described later). Thus, the resulting framework utilizes both an updated HIV Prevention Continuum for YMSM of Color that maps well onto the dimensions of access to care described by Penchansky and Thomas.

Results

Health Concerns for Young Men Who Have Sex with Men

Young men were asked about their biggest health concerns. Among the most common responses were issues related to overall physical health including nutrition and exercise – with several noting that “knowing your body” and being “aware of your needs” are keys to good health. Many of the young men in the focus groups were living on their own for the first time and expressed that shopping for food and cooking was a challenge as “having a healthy lifestyle is very expensive” and time consuming. Several stated they missed the home cooking they had when living at home where things were prepared for them. In addition, given the many responsibilities related to work, school and/or family, young men generally felt they did not get enough exercise or eat well.

Stress and Mental Health

These everyday concerns about basic needs and other life issues contribute to a generalized feeling of stress that was described in each of the focus groups. High levels of stress related to family, work, school, meeting basic needs and other experiences can lead to other problems such as “binging to make yourself feel better”, “drinking every day” or other less healthy coping strategies such as smoking or other drug use. As one focus group participant stated, “when it comes to health, you need to have like emotional, physical, spiritual all of that together…when you don’t have one without the other, you’re kinda all like, off balance”. This young man and others felt that you needed to look at health more holistically to better understand how different aspects of your being affect others.

Stress can affect a person physically, mentally and spiritually and was described by one focus group participant as “black magic—it can cause anything and everything”. Young men also described feeling enormous amounts of pressure from “everyone” including “people who are closest to us, like friends and families or it could just be society”. As young men of color, the majority of whom identify as gay, the expectations for success were seen as higher than for others. One young man acknowledged that “sometimes we forget we’re not gods, we’re not perfect, we’re not all of these things that everyone expects us to be”. When discussing the pressures of life and meeting their own and others’ expectations, young men recognized that these pressures and stress can sometimes lead to unhealthy coping strategies where they “just wanna feel good right now, I want something to feel good and we look to certain vices whether it’s shopping, comfort food, or sex or drugs….it’s this never-ending cycle that never really breaks”.

In a similar vein, when young men discussed the challenges of scheduling and maintaining complex schedules that include work, family, school, friends and other activities, they felt this left little time to work on their health. As “men within the LGBT community, men of color, it’s important that we know how to balance” life’s demands. They also acknowledged that while you can work hard to remind yourself to do things, set alarms and other tricks to manage their lives and schedules, if someone is overly stressed and feeling bad about themselves, this can lead to feelings of depression and anxiety. In such cases when someone has these feelings and does not want to follow through on appointments or reminders, one respondent described this as “when your spirit starts to die.” He felt this is what was most difficult because:

That’s what keeps you going…[and] I don’t know how to rekindle that…you know, if I’m getting overweight I know I can go to the gym. If I’m like getting stressed out, I know I can go and meditate …if I get sick I can go to the doctor. But, if my spirit’s dying, like, I don’t know what to do for that.

While describing one’s spirit as being the driver of behavior was a unique choice of words, the sentiment was echoed across all focus groups with YMSM. While more commonly referred to as mental health, this was seen as the biggest need for this population, and the hardest to access. Related to the Penchansky and Thomas’s dimension of availability (Penchansky & Thomas, 1981), low cost mental health services are hard to find and include limited hours, availability and stringent limits on the number of visits. One young man who was a student at a local university explained that counseling services were available on campus but also lamented about the lengthy process for enrollment and limited availability of counselors. Others with commercial or public insurance related to the affordability dimension of access (Penchansky & Thomas, 1981) and explained that mental health services were generally not covered, were limited to a small number of sessions (e.g., fewer than 10) and, when they were covered, the copays were too expensive.

Being mentally healthy for these young men meant feeling good about yourself, having a sense of self-esteem and pride, knowing what is important for you and being realistic about what you can do. While many focus group participants described striving for perfection with regards to their bodies, jobs and relationships, knowing how much one can realistically manage was seen as the key to being mentally healthy. Mental health was described as “what has to come first” in order to achieve anything else one wants, including physical health, the ideal relationship and a successful career. Being in good mental health was also related to knowing your emotions and how to react or express them in a society that often frowns on emotional expression. One participant described this as imperative to good health:

So we are sitting here thinking that, OK, are the characters from “Inside Out” in there working properly? Like is Joy running the show or is it Sadness or is it Bitch? So you’re sitting here thinking about your emotions and how to express them, or you don’t even know how to express them half the time. So you’ll go back to binge eating …or you’ll do something out of anger or sadness…because we’re just not taught how to fully deal and comprehend our own emotions. And when you do know how to do all that, that’s really moving towards good health.

Sexual Health

In addition to general healthy behaviors and mental health, YMSM mentioned sexual health, including HIV and STI prevention as well as access to PrEP. Given the risk profiles for YMSM of color, this is not surprising. What was somewhat surprising was the effect some of the public health education related to sexual health has had on YMSM of color. Most of the young men reported being tested for HIV every 3 or 6 months, generally following the recommended frequency. A few reported more frequent testing behaviors such as monthly due to their fear of contracting HIV.

While the messages have been effective in outlining the importance of protecting oneself, there was a sense of fear and paranoia amongst some of the participants resulting in some misperceptions about what constitutes high-risk sexual behavior and what the public health statistics actually mean. For example, some participants reported abstaining from any and all sexual activity (“I don’t fuck with that, I don’t fuck with sex”) including kissing and making out. Others stated that getting an STI is “always in the back of my mind” and “you have to worry about it all the time”. Interestingly, while many young men are fearful of contracting an STI, several acknowledged they do not know much about STIs including how to treat them, which are curable and the different ways they can be contracted. For example, one young man shared that when he “got chlamydia, that was like the scariest thing…I was like shaking almost ‘cause I didn’t know anything about it”.

The portrayal of young Black gay men in public health messaging resonated particularly strong with some participants; one young man stated that the medical profession believes that “HIV runs in Black gay men”. Another young man stated that he constantly hears the statistics about African American YMSM, that one out of two will be HIV+ by the time they are 40 years old. As a result, he believes that at some point in time, “in 6 months or a year or like a year and half or something…, it’s like I get tested and I’m positive for HIV”. This sense of inevitability was echoed across the focus groups.

Young Men’s Experiences with Health Care

Data from YMSM indicate that their health is clearly important to them. Like other adolescents and young adults, they are concerned about their physical health, particularly their diet and exercise. Many are also in the process of transitioning their care from a family doctor or pediatrician which includes negotiating insurance enrollment and identifying a doctor with whom they can connect and feel comfortable. In addition, many also have complicated and busy schedules that include work, school and family obligations; these schedules are often at odds with hours of clinics and doctors’ offices (as related to Penchansky and Thomas’s (1981) dimension of adequacy). However, unlike their heterosexual peers, YMSM are also dealing with issues related to stigma, as well as privacy and comfort in discussing sexual health, all of which can facilitate or impede access to care.

Many of the young men described a number of challenges in accessing health care. Like other young adults, these young men are exploring their independence in different ways, and this can include signing up for health insurance and finding a primary provider, things that had typically been done by their parents or other caregivers in the past. Young men described circumstances related to Saurman’s (2016) modified model of access and the dimension of awareness, indicating limited knowledge in this area and that “no one’s really shown me how to do that stuff” and that this “wasn’t something that was covered in high school or junior high”. The process of finding a competent and caring medical provider can be complex and require a level of health literacy or knowledge that most young people are not generally exposed to, further complicating their access to care. For example, Penchansky and Thomas (1981) describe an important aspect of access as identifying providers with characteristics that are acceptable to the patient/consumer. Young men in this study were unsure how to find a provider they can relate to, indicating they are not sure of the “vetting process” for finding a doctor. Similarly, many young men were not aware that they can change a provider assigned to them by their insurance provider, much less how to do so.

Young men in our focus groups were generally divided into two groups, those with regular access to a longtime primary care provider (usually a family doctor) and those with limited access to care and/or no primary care provider. Commonalities among those who reported regular access to care included having health insurance through work or family, having a primary care provider as opposed to a clinic with rotating providers, and a strong family history of accessing care.

This latter point seemed to be strongly correlated to current access to care, with young men who reported regularly going to the doctor as a child being more likely to report consistent access to care. These young men indicated that annual check-ups and ongoing communication with their doctor was something that had been instilled in them at an early age. One participant reported that for him, “health was always something that was important, just like education…health and education pretty much go together cause if you don’t know how to deal with something you research it, you ask questions…I attest [sic] that really to my mom”. For these young men, going to the doctor was something that they “never had to worry about” as they knew where to go. These young men generally felt comfortable with their doctor, one young man stated that he was very comfortable with his doctor due to his mother saying things like your “doctor’s like your best friend. You have to, you know, be honest about anything and everything”. In addition, young men in this group described their habits for making regular appointments as “I just try to stick to the routine of getting a check-up every six months…’cause that’s what my mom always would do”.

Young men who did not regularly access care tended to not have health insurance or be enrolled in a public insurance plan like Medi-Cal. One participant reported that he went from having no health insurance, to getting on Medi-Cal to having insurance through his employer with a local HMO. He described the inequity of care between the public and private insurance as “astounding” as he now has regular access to specialists and generalists in professional environments; in contrast he described his time on public insurance as being ”bottom of the barrel”. He acknowledged that he has better care now only “because I have a job that pays well and the job has those benefits so it’s like a privilege in itself but it took a long time to get there…it’s not something that’s easily accessible for most people”.

Young men in this group also described limited interactions with doctors growing up. For some this was related to their family not having health insurance growing up. One young man reported he had not been to the doctor since he was in elementary school but he recently had to go because he had tonsillitis which became very stressful because he did not “have healthcare…and my family doesn’t either…it’s never been a part of my life.” Some young men related this limited access to healthcare with cultural values. For example, among Latino young men, use of home remedies was common rather than going to the doctor and having to pay for the visit and prescriptions “when you grow up in an ethnic family, you get all these home remedies”. African American young men tended to describe only going to the doctor when there was a clear emergency and that it is common to let things heal on their own rather than seeking medical advice. This was something that was ingrained in them as a child:

R1: “when we were playing outside, my cousins, like falling off trees, down the hill, scraping knees, going into the house crying, Mom, Auntie, Grandma… [they would then ask] ‘Are you bleeding, if not, get your ass up and keep going and keep playing’.

R2: You keep going…

R1: You learn from like two, three, four [years old]…so by the time we are teenagers we don’t go to the doctor.

Another participant explained that this was also an issue in his family. He shared a time when he had to go to the hospital in high school, which was a real wake up call for him and his family, about being more aware of their health. They now make a ritual of all going to the doctor together on an annual basis on the same day. He stated that “you have to be the example, especially with parents; they have to show that example in order for that to continue from generation to generation, if you make it a ritual to schedule your appointments all in the same day”.

When YMSM Access Care

As described, respondents generally fell into two camps, those who more regularly accessed care and those who did not. For those who regularly accessed care, it seemed that generally this was not for more preventive care. Instead, these young men reported making seeing their providers when feeling ill or having an injury of some kind, citing being “too busy” to go to regular check-ups. In contrast, those with limited access to care only saw their providers when there was a major issue (e.g., accident, serious illness). Some of the young men related this reticence in accessing care to cultural values, with one group of African American respondents inquiring, ”how many Black dads really visit the doctor?”. Latino young men agreed with these sentiments with some noting, “we fix ourselves”.

Young men did acknowledge that while generally, not having consistent access to care does not impact their lives on a regular basis, when something does happen like “you get an STD…or like you have a super high fever and it’s like when things happen and you realize you don’t have somewhere that you can go, that’s terrifying”. One young man reported that “if I wouldn’t have gotten HIV, I probably still wouldn’t have a doctor right now….it’s when something happens is…what made me have to go in….and then trying to navigate it then on top of like dealing with something that was really stressful…like it was really confusing”.

Again, related to the dimension of acceptability, when discussing the qualities they look for in a provider, one of the most important things was a sense of comfort with the provider (Penchansky & Thomas, 1981). Many of the focus group participants indicated having very negative experiences in doctors’ offices including feeling judged by clinic staff. One young man reported seeing a doctor at his regular clinic. The young man shared his sexual history with the doctor and the doctor then proceeded to tell him that “you really should reconsider having sex with men or having gay sex…because our bodies aren’t built like that, we’re made to have sex with a woman…plus it’s just, it’s just better for your spirit”. Another respondent reported going to a clinic for treatment for an STI and the clinic nurse with a look of “disgust”, disrespectfully asked, “Ugh, you’re in here again?”. These accounts were not unusual in the course of data collection; in fact they were more the norm. One young man felt that these types of experiences were “discouraging and will make people not want to engage with that stuff [healthcare] even if something is wrong, like that’s a huge problem”.

As a result of these experiences, young men generally acknowledged that having someone that is culturally competent is key to quality care. For these young men, this meant someone who was both competent with regards to culture and ethnicity but also competent in working with YMSM and other sexual minority groups. Many of the young African American participants expressed dealing with providers who were either not accustomed to working with African American communities or faced open hostility and micro-aggressions from the provider or staff. For example, one young man, a public health student, reported that when he sees a provider he is well aware of their discomfort and inexperience of working with African American patients. He reported that the provider only asked whether he played basketball “[he really] threw that out there because that’s what [she’s] used to ….or doing a checklist in [her] mind. Either way, I’m offended.” Another participant reported that as an adult, he now is aware of needing to pick and choose who he “settles for” in a physician. He stated that “I need to know that they understand what my community is going through and they don’t have uh, uh, a certain distaste for my community…cause that makes them kind of dismissive with whatever it is that I approach them with.” One young man clearly linked this lack of cultural competency to access to care, “it’s gonna further perpetuate people not wanting to go to the doctor…in our community, I’m being honest with you, a lot of Black folks, we don’t like to go to the doctor period. And that goes from generation to generation. There’s people that die because they don’t go to the doctor because dealing with doctors who aren’t culturally competent and who aren’t aware of the many issues that go on within the community”.

Having someone who understands “my lifestyle” was a sentiment heard throughout the focus group sessions. This quality is important as young men should be able to relate to their provider instead of seeing someone who is “going to look at me weird”. Having a shared experience with the provider was seen as important with one participant stating that the issues he wants to talk about with a doctor “affect our community as a whole” and even an ally cannot be fully competent because they lack the shared experience. For example, several participants reported that the only questions their doctors asked them related to HIV or sexual health was whether they wanted to be tested for HIV. These young men reported that when the results came back negative, there was “nothing to discuss”.

Importantly, respondents also identified that doctors lacking this competency are generally not aware of new advances in HIV prevention including PrEP and PEP. None of the focus group participants who had a provider practicing outside of an LGBT-specific health center, indicated that their primary care doctors had ever initiated a discussion about PrEP with them. One young man expressed that he would like to ask his doctor about PrEP but “this is a doctor who has to see a lot of other types of patients…and I live in the ghetto basically. So I don’t think this doctor thinks or cares to encounter that type, that many people who would actually ask for PrEP.”

One focus group discussion compared their experiences with openly gay providers with straight doctors:

I feel like with a straight doctor would just be like not really interested in what you’re talking about and…can’t really give you advice for it cause they’re not o that level with you…versus this doctor…when I tell him things I’ve done, it’s like OK, you need to protect yourself, do this…

Ideally I would like a gay doctor….it would just be easier. I feel like I have asked heterosexual doctors oh do you know about this…and they’re like no. So I feel like if I were to ask about anything they would be like – what’s that – and I would kinda raise my eyebrow, like oh, do you read the tabloids? Like do you own a TV?

Discussion

An HIV Prevention Continuum for YMSM of Color

This study provides important information about the challenges that YMSM of color experience in accessing care. These challenges include limited health literacy for navigating a complicated service system, identifying appropriate providers, cultural values and histories concerning healthcare and cultural competency (or lack thereof) of community providers.

To date, HIV providers and researchers have focused most of their efforts and programming on the HIV Care Continuum as a means to reach national and international goals of zero new infections. While efforts to identify and treat HIV positive individuals is absolutely necessary to achieve this goal, there is still a lot of work to be done on the prevention end of the continuum to develop programs and services that encourage access to preventive services at a young age and promote overall health and well-being. Similar to what other studies have found, (Luk et al., 2017; Meanley et al., 2015) the young men in this study indicated that many YMSM are not regularly accessing medical services. Without regular access to care already being integrated into their lives, the challenges of linking HIV positive young men into care, retaining them and reaching adherence to their medications will remain.

The data in this study clearly indicate there is work to be done to ready young people to navigate a complex healthcare system, identify culturally competent providers and become better advocates for their own health. Once again, using the modified Penchansky and Thomas model for access as a guide, we mapped our own data to the dimensions of access (Penchansky & Thomas, 1981; Saurman, 2016). One area that did not directly map onto this model are those data that describe prior experiences with healthcare, one’s own as well as family history, and how that contributes to accessing care, particularly preventive care. For example, participants described to what extent their families’ experiences impacted their own access to care, with young men whose family instilled the importance of check-ups and regular care reporting currently accessing regular use of preventive care. In contrast, those whose families’ tended to put off medical care until it was a real emergency, were more likely to currently report more limited use of healthcare services. To include this important aspect in the model, we propose an additional dimension of attitude. We propose this new “a” to the access model to account for one’s attitude, including individuals’ emotions, feelings, beliefs, opinions and/or inclinations, and how they affect one’s access to care. This inclusion integrates the consumer/patient experience into the access model, a stark omission from the current school of thought.

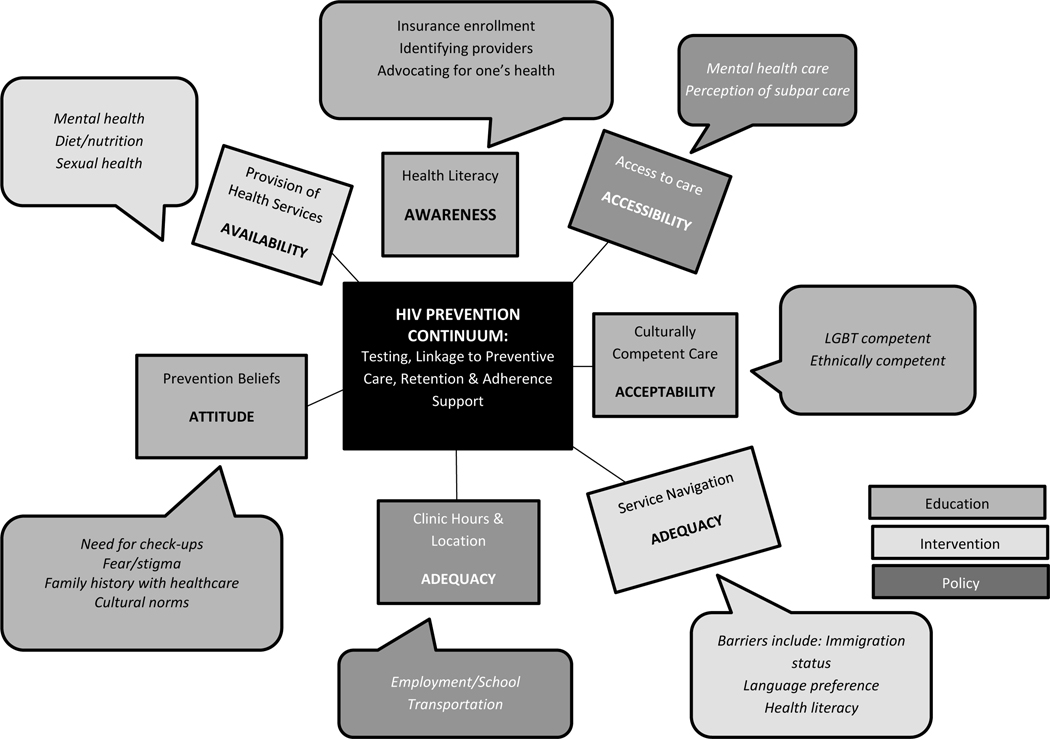

Figure 1 provides a schematic of our qualitative data discussed here as it relates to an HIV Prevention Continuum for YMSM of Color. As indicated by the legend, rectangles are meant to include dimensions of health access as outlined in the Penchansky model and described by focus group participants. The call-outs provide more concrete examples of what those dimensions represent based on YMSM’s experiences. Borrowing from McNairy and El-Sadr (2014) who proposed a shift in focus from care to prevention, we build on their idea of a prevention continuum by providing clear areas for education (e.g., health literacy, cultural competency, prevention beliefs), intervention (service navigation, provision of health services) and policy change (e.g., clinic hours, access to care) to support better overall health for YMSM of color. While several young men lamented that there is “no money for that [prevention]”, we strongly advocate for the development and testing of interventions that focus on increasing health literacy, improving access to care - particularly mental health services - and increasing the cultural competency of medical providers. Achieving these goals will lay a strong foundation for engagement of YMSM and other sexual minority individuals in health care. Once this is achieved, engagement in a care continuum will be more seamless.

Figure 1.

Elements to Address for Full Engagement in an HIV Prevention Continuum for YMSM of Color

The literature indicates a dearth of research about health literacy among adolescents and young adults; most of the interventions and related evaluative scales have been designed for adults (Manganello, 2008; Sansom-Daly et al., 2016; Shone, Doane, Blumkin, Klein, & Wolf). The tasks that young people are expected to master with regards to health care can be complex and overwhelming, and currently there are few resources that are easily accessible and that provide practical and relevant information for young people. Related to Figure 1, with regards to education, there are a number of recommendations from this study related to health literacy that include very concrete tasks such as how to: 1) to enroll in insurance; 2) identify a provider; 3) change a provider; 4) advocate for one’s health; and 5) speak with a provider about one’s health. Health literacy interventions can also address some of the cultural norms that were described by our participants including when to see a doctor, the difference between home remedies and medical services, and the importance of preventive services. Interventions to enhance health literacy skills may include programs that can be conducted in school or health care settings and can potentially use mass media and/or gaming technology (e.g., medical television shows, online or app-based programs) to teach health literacy skills to adolescents. Creating and evaluating interventions that are varied according to content, target group and administration will lead to programs that can enhance health literacy skills among YMSM and other adolescents (Manganello, 2008; Sansom-Daly et al., 2016).

Interventions that utilize mHealth and other technologies should also be developed and evaluated to bridge the challenge of accessing care, particularly mental health care which was mentioned in each focus group and endorsed by almost all of the participants. Given the ubiquitous presence of technology in the lives of adolescents and young adults, telehealth platforms may be an effective method for delivering interventions including mental health services and service navigation. Telehealth programs have been relatively commonly used in rural and military settings given the limited access to care and high mobility for these populations, respectively (Mishkind, Boyd, Kramer, Ayers, & Miller, 2013; Nesbitt, Cole, Pellegrino, & Keast, 2006; Tuerk et al., 2010). Telehealth in urban settings can be just as useful given the challenges young people often experience with accessing transportation and/or integrating health appointments into their already busy schedules. Telehealth for mental health services has been found to be just as effective as face-to face interaction with high patient satisfaction, (Barak, Hen, Boniel-Nissim, & Shapira, 2008; Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2015) moderate to high clinician satisfaction and positive clinical outcomes (Richardson, Christopher, Grubaugh, Egede, & Elhai, 2009).

With regards to improving access to care, there are also a number of policy implications that can be explored. For example, our community engagement process for this study identified that the majority of clinics providing STI screenings and other services important for YMSM typically do not offer services after 4:00 pm; clinics that are open on weekends are also very limited. These hours are more employee-centered than client centered and providers should consider expanding their hours during the week and/or having some availability on weekends to allow greater access for young people. Also, while some young people are able to remain on their parents’ health insurance until the age of 26, many young people are not able to take advantage of this. Regardless, tools that help explain the insurance enrollment process as well as explanations regarding copays, deductibles and covered services that are designed for young people are necessary. This may go a long way in ensuring these “young invincibles” are enrolled in insurance and able to access services when they need them.

Cultural competence, defined as the awareness and adequate responsiveness to patient populations with cultural factors that may affect health care including language, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors of providers (Betancourt, Green, & Carrillo, 2002) as it relates to both race/ethnicity and sexual orientation, was identified as a barrier to accessing care. Homophobia in the healthcare system still exists, including refusals to provide accepted standards of care and verbal abuse (National Research Council, 2011). Healthy People 2020 has documented a shortage of providers who are culturally competent in LGBT health (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). A recent survey of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education-accredited practices found that less than 10% of practices had policies or procedures in place to identify LGBT-competent providers for the public (Khalili, Leung, & Diamant, 2015); the majority questioned the need for facilitating this access suggesting that many providers are unaware of the challenges sexual minority individuals face in identifying competent providers. This same survey found that the majority of institutions (52%) have no LGBT-competency training available for their providers.

Cultural competency training has been shown to increase provider knowledge and awareness and to improve communication skills (Joos, Hickam, Gordon, & Baker, 1996; Radix & Maingi, 2018; Roter et al., 1995). Comfort in discussing one’s sexual identity or sexual behaviors with providers is a concern. Adult MSM have reported discomfort in discussing their same sex behaviors with providers, (Klitzman & Greenberg, 2002) and this feeling of discomfort may be more intensified for YMSM since they are less likely to have talked with anyone about their sexual identity. Disclosure, however, is important to receiving the appropriate screenings and advice as disclosure has been associated with a higher likelihood of receiving HIV screening and information about HIV and STI prevention (K. T. Bernstein et al., 2008; Brooks et al., 2018; Meanley et al., 2015). Having a physician who is culturally competent can promote better communication between providers and patients. In order to fully address the HIV Prevention and Care Continua, it is imperative that medical institutions develop standard policies and procedures to increase the competency of their providers. Currently there are no standards for identifying cultural competency for LGBT patient populations. Healthcare providers and administrators should work with the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (or similar bodies) and LGBT populations to develop these standardized criteria for providers and organizations so that sexual minority populations have a threshold for identifying appropriate physicians and clinics. One model to examine are the guidelines developed by the Fenway Institute in Boston which provides recommendations for healthcare organizations to ensure intake forms and recommended screenings/tests are adapted for LGBT patients (Ard & Makadon, 2012). These criteria should then be used by HIV advocates and providers to develop referral guides that identify local culturally competent providers and clinics for their patient populations.

There are a number of limitations to this study that should be acknowledged. These analyses are based on experiences and perceptions of young men recruited in Los Angeles. Although various recruitment methods were employed, the majority of young men in our sample were recruited from gay-identified venues (e.g., bars, clubs, websites). The experiences of our participants may not be reflective of men outside of Los Angeles and/or young men who do not patronize gay venues. For prevention efforts, future studies should include data collected in other cities and communities. While the goal of qualitative data is not to be generalizable to other samples but rather provide context and depth to specific phenomenon, it should still be noted that because this was largely a qualitative analysis, the data reported were derived from a small sample; therefore attempts at generalizability cannot be made. Additionally, the use of focus groups rather than individual interviews may have contributed to concerns about social desirability amongst participants. While the researchers did not sense this was a concern during the course of data collection, this should be acknolweded as a limitation of the data collection. In addition, this was a community sample, not a population based sample and thus generalizations cannot be extrapolated to other YMSM. Also, the findings rely on respondents’ self-reported behaviors, which cannot be independently verified. Additionally, the data reported here are cross-sectional and therefore do not contain information about the trajectory of their use of and experiences with the healthcare system over time. The developmental stage in which these young men currently reside, emerging adulthood, involves many changes and transitions, and it is unclear how these behaviors and perceptions may develop with age (Arnett, 2000). We encourage others to further explore these areas to better understand the temporal relationships.

In spite of these limitations, the data presented here speak to a number of recommendations for service providers and researchers to develop effective prevention programs for YMSM. Research continues to show that sexual minority individuals experience disparities in many important health outcomes (Halkitis & Figueroa, 2013; Meyer & Northridge, 2007; Storholm et al., 2013); understanding how to ensure that LGBT youth, specifically YMSM of color, are accessing quality preventive care is an integral step in advancing our efforts to a world without HIV. By integrating aspects of both prevention and care in a single paradigm (e.g., the HIV Prevention and Care Continua), we can ensure a balanced focus on care for those young people who are HIV positive as well as help those who are HIV negative remain negative and healthy in other areas of their being. Thus, it is time that policymakers recognize that access to care is yet another area in which sexual minority individuals face inequitable disparities and it is time for research and programs to address these significant disparities.

Table 2.

HYM 2.0 Cohort Health Status and Health Behaviors (N=449)

| Variable | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Overall health | Excellent | 43 (10) |

| Very good | 129 (29) | |

| Good | 138 (31) | |

| Fair | 113 (25) | |

| Poor | 24 (5) | |

| Currently worried about something related to health or body | Yes | 249 (56) |

| Hours of sleep | Not enough hours | 245 (55) |

| The right number of hours | 163 (36) | |

| Too many hours | 39 (8) | |

| Number of days in the past 7 days exercised for 20 minutes | 0 days | 96 (21) |

| 1 – 2 days day | 89 (20) | |

| 3 −5 days | 183 (41) | |

| > 5 days | 70 (18) | |

| Number of times in the past 7 days fruit was consumed | 0 times | 34 (8) |

| 1 to 3 times per week | 158 (35) | |

| 4 to 6 times per week | 95 (21) | |

| Once a day or more | 159 (35) | |

| Number of times in the past 7 days green salad was consumed | 0 times | 151 (34) |

| 1 to 3 times per week | 198 (44) | |

| 4 to 6 times per week | 51 (11) | |

| Once a day or more | 45 (11) | |

| Ever diagnosed with a chronic condition | Yes | 222 (49) |

| Top chronic conditions | Depression | 86 (19) |

| Anxiety | 73 (16) | |

| Asthma | 68 (15) | |

| Needed/wanted mental health care/counseling in last 12 months | Yes | 247 (55) |

| Received the mental health care needed in last 12 months a | Yes | 72 (29) |

| No | 173 (70) | |

Denominator is 247; those who wanted/needed mental health care

Table 3.

HYM 2.0 Cohort Access to Preventive Healthcare and HIV/STI Testing (N=449)

| Variable | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Has a regular place to go for healthcare | Yes | 371 (82) |

| Has a primary care provider | Yes | 246 (55) |

| Seen a doctor in the last 12 months | Yes | 319 (71) |

| Used emergency department in last 12 months | Yes | 157 (35) |

| Satisfaction with doctor or primary care provider | Very dissatisfied | 10 (2) |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 39 (9) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 139 (31) | |

| Very satisfied | 164 (36) | |

| Currently has health insurance | Yes | 374 (83) |

| Source of health insurance | Parent | 146 (39) |

| Work/school | 49 (13) | |

| Medicaid | 138 (37) | |

| Changed health insurance in last 6 months | Yes | 67 (15) |

| Was uninsured for a period of time in last 6 months | Yes | 119 (26) |

| Last time tested for HIV | Never tested for HIV | 11 (2) |

| < 3 months ago | 196 (44) | |

| Between 3 and 6 months ago | 76 (17) | |

| 6 months – 1 year ago | 34 (8) | |

| > 1 year ago | 23 (5) | |

| Location of last HIV test | Rapid testing in a van | 42 (9) |

| Rapid testing in a clinic | 91 (20) | |

| At a clinic (NOT rapid testing) | 113 (25) | |

| At a doctors office | 81 (18) | |

| Ever tested for a STI | Yes | 397 (88) |

| Positive test for one or more STIs at baseline* | Yes | 107(27) |

| Gonorrhea (throat) | 30 (9) | |

| Gonorrhea | 8 (2) | |

| Gonorrhea (anal) | 29 (8) | |

| Chlamydia | 7 (2) | |

| Chlamydia (anal) | 38 (11) | |

| Syphilis | 46 (13) | |

Denominator is 395 due to missing data

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the many staff members who contributed to collection, management, analysis and review of this data: James Aboagye, Ifedayo Akinyemi, MPH, Alex Aldana, Stacey Alford, Alicia Bolton, PhD, Ali Johnson, Lily Negash, MPH, Nicole Pereia, Yolo Akili Robinson, Aracely Rodriguez and Maral Shahanian. The authors would also like to acknowledge the insightful and practical commentary of the members of: The Community Advisory Board: Joaquin Gutierrez, Altamed Health Services, Daniel Nguyen, Asian Pacific AIDS Intervention Team, Ivan Daniels III, Los Angeles Black Pride, Steven Campos and Davon Crenshaw, AIDS Project Los Angeles, Andre Mollette, LA Gay and Lesbian Center, Miguel Martinez, Division of Adolescent Medicine, CHLA, Greg Wilson, Reach LA, and Jesse Medina, The LGBTQ Center Long Beach.

Support for the original research was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (U01DA036926). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

References

- Allen LB, & Glicken AD (1996). Depression and suicide in gay and lesbian adolescents. Physician Assistant, 20, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ard KL, & Makadon HJ (2012). Improving the health care of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (lgbt) people: Understanding and eliminating health disparities Retrieved from Boston, MA: [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Mickey RM, & Rothblum ED (2005). Mental health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings: Effects of gender sexual orientation, and family. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(3), 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A, Hen L, Boniel-Nissim M, & Shapira N. (2008). A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 26(2–4), 109–160. doi: 10.1080/15228830802094429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard-Gilligan M, Duax Jakob JM, Doane LS, Jaeger J, Eftekhari A, Feeny N, & Zoellner LA (2015). An investigation of depression, trauma history, and symptom severity in individuals enrolled in a treatment trial for chronic PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(7), 725–740. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein AB, Hing E, Moss AJ, Allen KF, Siller AB, & Tiggle RB (2003). Health care in America: Trends in utilization. Retrieved from Hyattsville, Maryland: [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KT, Liu KL, Begier EM, Koblin B, Karpati A, & Murrill C. (2008). Same-sex attraction disclosure to health care providers among New York City men who have sex with men: implications for HIV testing approaches. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(13), 1458–1464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, & Carrillo JE (2002). Cultural competence in health care: emerging frameworks and practical approaches. Retrieved from New York, NY: [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, & D’Augelli AR (2002). Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks H, Llewellyn CD, Nadarzynski T, Pelloso FC, De Souza Guilherme F, Pollard A, & Jones CJ (2018). Sexual orientation disclosure in health care: A systematic review. British Journal of General Practice 68(668), e187–e196. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X694841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). HIV and young men who hav sex with men Retrieved from Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors/pdf/hiv_factsheet_ymsm.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, Sell RL, Silezio DMV, Bowen DJ, . . . Xavier J. (2000). Lesbian, Gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Findings and concerns. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 4, 102–151. [Google Scholar]

- Freedner N, Freed LH, Yang YW, & Ausin SB (2002). Dating violence among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a community survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Adams J, Friedman L, & East P. (2002). Links between past abuse, suicide ideation, and sexual orientation among San Diego college students. Journal of American College Health, 51(1), 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P. (1989). Gay male and lesbian youth suicide (3). Retrieved from Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, & Figueroa RP (2013). Sociodemographic characteristics explain differences in unprotected sexual behavior among young HIV-negative gay, bisexual, and other YMSM in New York City. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(3), 181–190. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Jones K, Phillips Ii G, Wohl A, & Giordano TP (2011). Baseline Clinical characteristics, antiretroviral therapy use, and viral load suppression among HIV-positive young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25 Suppl 1, S9–14. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ND, Freeman K, & Swann S. (2009). Healthcare preferences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. (1990). Violence against lesbian and gay male youths. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 5, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian, G., Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, . (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Retrieved from Washignton, DC: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64806/ [Google Scholar]

- Irwin CE, Adams SH, Park MJ, & Newacheck PW (2009). Preventive care for adolescents: Few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics, 123(4), e565–e572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos SK, Hickam DH, Gordon GH, & Baker LH (1996). Effects of a physician communication intervention on patient care outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 11(3), 147–155. doi: 10.1007/bf02600266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili J, Leung LB, & Diamant AL (2015). Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. American Journal of Public Health, 105(6), 1114–1119. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Weiss G, Wong C, Lopez D, Iverson E, & Ford W. (2007). The health and health behaviors of young men who have sex with men. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(4), 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Kubicek K, Wong CF, Robinson YA, Akinyemi IC, Beyer WJ, . . . Belzer M. (2019). A focus on the HIV care continuum through the Healthy Young Men’s Cohort study: Protocol for a mixed-methods study. JMIR Research Protocol, 8(1), e10738. doi: 10.2196/10738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirzinger WK, Cohen RA, & Gindi RM (2012). Health care access and utilization among young adults aged 19–25: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–September 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzinger WK, Cohen RA, & Gindi RM (2013). Trends in insurance coverage and source of private coverage among young adults aged 19–25: United States, 2008–2012. NCHS Data Brief(137), 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman RL, & Greenberg JD (2002). Patterns of communication between gay and lesbian patients and their health care providers. J Homosex, 42(4), 65–75. doi: 10.1300/J082v42n04_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Torian LV, Xu G, Guilin V, Makki H, MacKellar DA, & Valleroy L. (2006). Violence and HIV-related risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 18(8), 961–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krehely J. (2009). How to close the LGBT health disparities gap. Retrieved from americanprogress.org website: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/reports/2009/12/21/7048/how-to-close-the-lgbt-health-disparities-gap/ Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbt/reports/2009/12/21/7048/how-to-close-the-lgbt-health-disparities-gap/ [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, & McNeeley M. (2015). Young men who have sex with men’s experiences with intimate partner violence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. doi: 10.1177/0743558415584011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Gilman SE, Haynie DL, & Simons-Morton BG (2017). Sexual orientation differences in adolescent health care access and health-promoting physician advice. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(5), 555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganello JA (2008). Health literacy and adolescents: A framework and agenda for future research. Health Educ Res, 23(5), 840–847. doi: 10.1093/her/cym069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcell AV, Morgan AR, Sanders R, Lunardi N, Pilgrim NA, Jennings JM, . . . Dittus PJ (2017). The socioecology of sexual and reproductive health care use among young urban minority males. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(4), 402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, Stall R, Goldhammer H, & Landers S. (2008). Sexual and gender minority health: What We know and what needs to be done. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 989–995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarrity LA (2014). Socioeconomic status as context for minority stress and health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity,, 1(4), 383–397. [Google Scholar]

- McNairy ML, & El-Sadr WM (2014). A paradigm shift: Focus on the HIV prevention continuum. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 59 Suppl 1, S12–S15. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meanley S, Gale A, Harmell C, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Pingel E, & Bauermeister JA (2015). The role of provider interactions on comprehensive sexual healthcare among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 27(1), 15–26. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, & Northridge ME (2007). The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Mishkind M, Boyd A, Kramer GM, Ayers T, & Miller PA (2013). Evaluating the benefits of a live, simulation-based telebehavioral health training for a deploying army reserve unit. Military Medicine, 178(12), 1322–1327. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML, Korchmaros JD, & Kosciw JG (2014). Accessing sexual health information online: use, motivations and consequences for youth with different sexual orientations. Health Educ Res, 29(1), 147–157. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, Adams SH, Irwin CE, & Brindis CD (2009). Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(1), 8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, & Emerson EM (2010). Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.178319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Herrick A, & Donenberg GR (2007). Psychosocial helath problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Retrieved from Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt TS, Cole SL, Pellegrino L, & Keast P. (2006). Rural outreach in home telehealth: Assessing challenges and reviewing successes. Telemedicine and e-Health, 12(2), 107–113. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Birkett M, Corliss HL, & Mustanski B. (2014). Sexual orientation, gender, and racial differences in illicit drug use in a sample of US high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 304–310. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EM, Urquhart JT, Brindis CD, Park M, & Irwin CE (2012). Young adult preventive health care guidelines: There but can’t be found. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 166(3), 240–247. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MJ, Mulye TP, Adams SH, Brindis CD, & Irwin CE (2006). The health status of young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(3), 305–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MJ, Scott JT, Adams SH, Brindis CD, & Irwin CE Jr. (2014). Adolescent and young adult health in the United States in the past decade: Little improvement and young adults remain worse off than adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(1), 3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penchansky R, & Thomas JW (1981). The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care, 19(2), 127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radix A, & Maingi S. (2018). LGBT cultural competence and interventions to help oncology nurses and other health care providers. Semin Oncol Nurs, 34(1), 80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond-Flesch M, Siemons R, Pourat N, Jacobs K, & Brindis CD (2014). “There is no help out there and if there is, it’s really hard to find”: a qualitative study of the health concerns and health care access of Latino “DREAMers”. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(3), 323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LK, Christopher F, Grubaugh AL, Egede LE, & Elhai JD (2009). Current directions in videoconferencing tele-mental health research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16, 323–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, & Roca RP (1995). Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 155(17), 1877–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan D, DeSousa M, Randall EM, White C, & Holley L. (2014). “We’re just targeted as the flock that has HIV”: health care experiences of members of the house/ball culture. Social Work & Health Care 53(5), 460–477. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2014.896847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon EA, Mimiaga MJ, Husnik MJ, Welles SL, Manseau MW, Montenegro AB, . . . Mayer KH (2008). Depressive symptoms, utilization of mental health care, substance use and sexual risk among young men who have sex with men in EXPLORE: Implications for age-specific interventions. AIDS Behav, 13(4), 811–821. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9439-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom-Daly UM, Lin M, Robertson EG, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Girgis A, & Cohn RJ (2016). Health literacy in adolescents and young adults: An updated review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol, 5(2), 106–118. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurman E. (2016). Improving access: Modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s Theory of Access. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 21(1), 36–39. doi: 10.1177/1355819615600001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shone LP, Doane C, Blumkin AK, Klein J, & Wolf MS Performance of health literacy tools among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(2), S11–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storholm ED, Siconolfi DE, Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Eddy JA, & Bare MG (2013). Sociodemographic factors contribute to mental health disparities and access to services among young men who have sex with men in New York City. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 17(3), 294–313. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2012.763080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, & Corbin J. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Swann G, Bettin E, Clifford A, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B. (2017). Trajectories of alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drug use in a diverse sample of young men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depend, 178, 231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk PW, Fortney J, Bosworth HB, Wakefield B, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, & Frueh BC (2010). Toward the development of national telehealth services: The role of veterans health administration and future directions for research. Telemedicine and e-Health, 16(1), 115–117. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2018, January 23, 2018). Healthy People 2020. Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH, McFarland W, & Shehan DA (2000). HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA, 284(2), 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb MJ, Kauer SD, Ozer EM, Haller DM, & Sanci LA (2016). Does screening for and intervening with multiple health compromising behaviours and mental health disorders amongst young people attending primary care improve health outcomes? A systematic review. BMC Fam Pract, 17, 104. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0504-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KA, & Chapman MV (2011). Comparing health and mental health needs, service use, and barriers to services among sexual minority youths and their peers. Health and Social Work 36(3), 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl A, Garland W, Wu J, Au C-W, Boger A, Dierst-Davies R, . . . Jordan W. (2011). A youth-focused case management intervention to engage and retain young gay men of color in HIV care. AIDS Care, 23, 988–997. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Weiss G, Ayala G, & Kipke MD (2010). Harassment, discrimination, violence and illicit drug use among YMSM. . AIDS Education and Prevention, 22(10), 286–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni BC, & Mayer KH (2014). The adolescent and young adult HIV Cascade of Care in the United States: Exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 28(3), 128–135. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]