Abstract

Respiratory complex I is a central metabolic enzyme coupling NADH oxidation and quinone reduction with proton translocation. Despite the knowledge of the structure of the complex, the coupling of both processes is not entirely understood. Here, we use a combination of site‐directed mutagenesis, biochemical assays, and redox‐induced FTIR spectroscopy to demonstrate that the quinone chemistry includes the protonation and deprotonation of a specific, conserved aspartic acid residue in the quinone binding site (D325 on subunit NuoCD in Escherichia coli). Our experimental data support a proposal derived from theoretical considerations that deprotonation of this residue is involved in triggering proton translocation in respiratory complex I.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, iron–sulfur cluster, NADH dehydrogenase, NADH:quinone oxidoreductase, proton‐coupled electron transfer, quinone reduction, redox‐induced FTIR spectroscopy, site‐directed mutagenesis

Respiratory complex I is a major enzyme of cellular energy metabolism coupling quinone reduction and proton translocation across the membrane. The coupling mechanism is not understood. We identify by means of redox‐induced FTIR spectroscopy and site‐directed mutagenesis a single aspartate residue that is deprotonated at −0.3 V and protonated at −0.1 V. This reaction is connected with quinone chemistry and is most likely involved in triggering proton translocation.

Abbreviations

FMN, flavin mononucleotide

Ferricyanide, the hexacyanoferrate anion

Fe/S, iron–sulfur

LMNG, Lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol

MD, molecular dynamics

MES, 2‐morpholinoethanesulfonic acid

OD, optical density

SDS/PAGE, sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Proton‐pumping NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, also called respiratory complex I, is essential for cellular energy metabolism in most organisms. It catalyzes the oxidation of NADH and uses the electrons for quinone (Q) reduction. The redox reaction is coupled with the translocation of protons across the membrane [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. These reactions are spatially separated: A so‐called peripheral arm catalyzes electron transfer and a so‐called membrane arm is responsible for proton translocation [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Mitochondrial complex I is made up of 45 different subunits including 14 conserved subunits, which are present in all species that contain a proton‐pumping NADH:Q oxidoreductase [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. In general, complex I from bacteria consists of the 14 core subunits. As a special case, the complex from Escherichia coli comprises just 13 subunits called NuoA to NuoN due to the fusion of the genes encoding subunit NuoCD [11, 12]. The structure of the 14 core subunits is strictly conserved, so that the complex from E. coli represents a minimal structural form of a proton‐pumping NADH:Q oxidoreductase [4, 6, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17].

NADH is oxidized by flavin mononucleotide (FMN) at the tip of the peripheral arm, and electrons are transferred by a series of iron–sulfur (Fe/S) clusters over a 100 Å distance towards the membrane [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Here, Q is reduced by the most distal Fe/S cluster N2 (Fig. 1) ~20–30 Å above the membrane plane [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Q is bound in a unique cavity composed of subunits from both arms. The membrane arm contains four putative proton pathways that are connected to each other and to the Q cavity by an approximately 200 Å long central axis of buried charged residues [4, 6, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19]. Three proton pathways are located on each of subunits NuoL, M and N of the membrane arm. The fourth pathway, called the E‐channel [6], is proximal to the Q binding site and it is composed of NuoH, A, J and K [6, 18]. Several mechanisms of proton translocation including all or just a few of the putative proton pathways are currently under discussion [5, 8, 9, 10, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23].

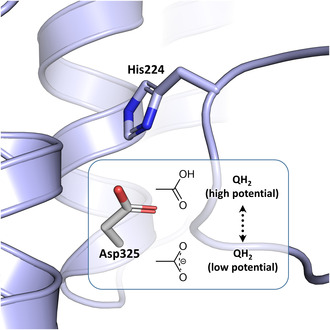

Fig. 1.

Structure of and electron transfer in complex I. (A) Structure of E. coli complex I (PDB: 7Z7S) with the subunits in gray [18]. The FMN and the Fe/S clusters are depicted in their standard atomic colors. The position of Q is in this structure is shown in red and green. (B) Scheme of the electron transfer in the peripheral arm of the complex from NADH (top) to the quinone (bottom). The amino acids mentioned in the text are depicted. (C) Arrangement of the amino acids in question in the Q binding site from T. thermophilus complex I (PDB: 4HEA). The Asp/His H‐bond is indicated by a dashed line and the distance is provided. The residues are shown in the T. thermophilus (purple) and in the E. coli (black) numbering. The position of the most distal Fe/S cluster N2 is shown at the top of the figure.

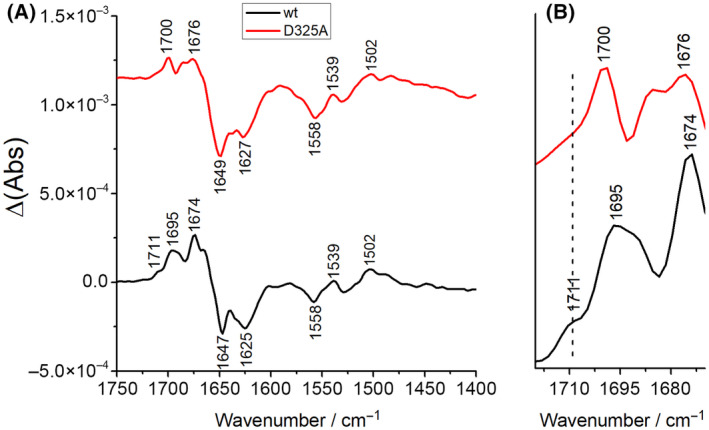

Before the structure of complex I was known, we showed by redox‐induced FTIR difference spectroscopy that the potential step from −0.3 to −0.1 V is coupled with the protonation of an acidic amino acid residue [24]. This potential step was attributed to the oxidoreduction of Fe/S cluster N2 with a redox potential of −0.16 V at pH 6 [25]. As N2 is located on NuoB, we tried to identify the acidic amino acid in question by site‐directed mutagenesis of NuoB without a clear result [25]. Electron transfer from N2 to Q is only possible when Q penetrates deeply into its binding cavity in 12 to 10 Å distance from N2 [17, 18, 20, 26, 27]. Redox titrations revealed a redox potential of tightly bound Q of less than −300 mV [28, 29]. It was suggested that this site corresponds to a so‐called low potential binding site (E m ~ −0.3 V) and that Q moves inside its binding cavity to another, the so‐called high‐potential binding site, where it takes a more positive redox potential (estimated to E m ~ 0.08 V) [23, 30].

Structural and biochemical data as well as MD simulations [6, 26, 31, 32, 33] suggested that the carbonyl groups of the quinone headgroup are in hydrogen‐bond contact to conserved H224CD and Y273CD (the superscript refers to the name of the E. coli subunit; numbering according to UniProt [34]. The different residue numbers in various organisms are listed in Table S1). The position of H224CD is further stabilized by forming an ion pair with D325CD [6, 26]. From large‐scale computational simulations, it was concluded that the reduction of Q is coupled with an opening of the His/Asp ion pair and subsequent protonation of reduced Q by Y273CD and H224/D325CD [26]. This would in turn generate a significant charge imbalance that is transmitted to the membrane arm. These steps were discussed as the initial charging steps of proton translocation [26].

We suspected that D325CD could be the acidic amino acid that is protonated during the potential step from −0.3 to −0.1 V [24]. To this end, we generated several mutations at position D325CD in E. coli complex I that significantly affect the electron transfer activity without disturbing the assembly of the complex. The sensitivity to the Q‐site‐specific inhibitor piericidin A is significantly decreased. Redox‐induced FTIR spectroscopy of the D325ACD variant clearly shows that this residue is protonated upon electrochemically induced electron transfer. Possible implications for energy coupling in complex I are discussed.

Materials and methods

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides

A derivative of E. coli BW25113 [35] chromosomally lacking ndh was used to overproduce complex I from a plasmid [36]. Here, the chromosomal nuo operon is replaced by a resistance cartridge (nptII). Escherichia coli strain DH5α∆nuo was used for site‐directed mutagenesis to avoid recombination [36]. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich. Restriction enzymes were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Site‐directed mutations were introduced into nuoCD on plasmid pBADnuo His [37] according to the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). A silent mutation was introduced by PCR using the KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Novagen), generating a new restriction site to identify positive clones by restriction analysis. The primer pairs for site‐directed mutagenesis are listed in Table S2. Mutations were examined by DNA sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany).

Cell growth and preparation of cytoplasmic membranes

To test the functionality of complex I, parental and mutant strains were grown aerobically in minimal medium with 25 mm acetate as sole carbon source [38] at 37 °C while agitating at 180 rpm. Expression of the nuo operon was induced by an addition of 0.02% (w/v) l‐arabinose. Cell growth was measured as optical density at 600 nm (OD600). For protein preparations, cells were grown in rich autoinduction medium with 34 μg⋅mL−1 chloramphenicol [38] and harvested by centrifugation. The sedimented cells were suspended in a fivefold volume of buffer A (50 mm MES/NaOH, 50 mm NaCl, pH 6.0) containing 0.1 mm PMSF and a few grains of DNAseI and disrupted by three passages through an HPL‐6 (Maximator, 1000–1500 bar) [38]. Cytoplasmic membranes were obtained by differential centrifugation [38] and suspended in an equal volume (1:1, w/v) of buffer A* (buffer A with 5 mm MgCl2) with 0.1 mm PMSF.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation

Proteins were extracted from the cytoplasmic membrane by an addition of 1% (w/v) LMNG (2,2‐didecylpropane‐1,3‐bis‐β‐D‐maltopyranoside; Anatrace) to a membrane suspension in buffer A* [38]. After incubation for 1 h at 4 °C, the suspension was centrifuged for 20 min at 160 000 g and 4 °C (Rotor 60Ti, Sorvall wX+ Ultra Series centrifuge; Thermo Scientific). 0.5 mL supernatant was loaded onto 24 mL gradients of 5–30% (w/v) sucrose in A*LMNG (buffer A* with 0.005% (w/v) LMNG) and centrifuged for 16 h at 104 000 g (4 °C, Rotor SW28, Sorvall wX+ Ultra Series centrifuge; Thermo Scientific). The gradients were fractionated into 1 mL portions.

Protein preparation

The D325ACD variant was prepared as described [39]. In short, membrane proteins were extracted with 2% (w/v) LMNG, the cleared extract was adjusted to 20 mm imidazole and applied to a 35 mL ProBond Ni2+‐IDA column (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in binding buffer (A*pH6.8 with 0.005% (w/v) LMNG and 20 mm imidazole, pH 6.8). Bound proteins were eluted with binding buffer containing 308 mm imidazole. Fractions with NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration in 100 kDa MWCO Amicon Ultra‐15 centrifugal filters (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and applied onto a Superose 6 size‐exclusion chromatography column (300 mL; GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany) equilibrated in buffer A* with 10% (v/v) glycerol and 0.005% (w/v) LMNG. Fractions with the highest NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity were used for further studies.

Activity assays

Activity assays were performed at 30 °C. The NADH oxidase activity of cytoplasmic membranes was determined by a Clarke‐type oxygen electrode (DW1, Hansatech, Pentney, UK) as described [38]. The electrode was calibrated by an addition of a few grains sodium dithionite to air saturated buffer [40]. NADH oxidase activity was inhibited by an addition of various amounts of piericidin A (ChemCruz, Heidelberg, Deutschland) to the NADH‐induced reaction. The NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity was determined as decrease of the ferricyanide absorbance at 410 nm [38] with a diode‐array spectrometer (QS cuvette, d = 1 cm, Hellma; TIDAS S, J&M, Aalen, Germany) using an ε of 1 mm −1⋅cm−1 [41]. The NADH:decyl‐Q oxidoreductase activity was measured as decrease of the NADH concentration at 340 nm using an ε of 6.3 mm −1⋅cm−1 (QS cuvette, d = 1 cm, Hellma; TIDAS S, J&M Aalen). The assay contained 60 μm decyl‐Q, 2 μg complex I or the D325ACD variant and a tenfold molar excess (5 μg) E. coli cytochrome bo 3 oxidase in buffer A*LMNG. The reaction was started by an addition of 150 μm NADH [38].

IR spectroscopy

The experiments were performed in a thin‐layer transmission electrochemical cell as previously described [42, 43]. The semi‐transparent gold grid that serves as a working electrode was modified with 1:1 solution of cysteamine and mercaptopropionic acid (mixture of positively and negatively charged thiols) in order to prevent the adsorption of protein on the electrode surface. A platinum contact and an aqueous Ag/AgCl 3 m KCl electrode were used as counter and reference electrodes, respectively. An hour before each experiment the protein was incubated with a cocktail of 19 mediators with a final concentration of 25 μm [44]. The cell was assembled as described previously [24]. The oxidized minus reduced FTIR difference spectra were obtained in the −300/−500 mV vs Ag/AgCl potential range (the values are converted to SHE’ potentials by adding +208 mV) using a Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer from Bruker Optics, with an equilibration time of 5 min for each step. The redox reaction was cycled over 50–80 times and for each redox state two spectra (256 scans, 4 cm−1 resolution) were averaged.

Other analytical methods

Protein concentration was determined by the biuret method using BSA as a standard [45]. The concentration of purified complex I was determined by UV/vis‐spectroscopy (TIDAS S; J&M) using an ε280 of 781 mm −1 cm−1 as derived from the amino acid sequence [46]. SDS/PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) was performed with a 10% separating gel and a 3.9% stacking gel [47]. The pKa of D325CD was calculated with PropKa3 [48] using the pdb model 7Z7S of E. coli complex I [18].

Results

D325CD of E. coli complex I was individually mutated to A, E, N and Q by changing the respective codon on the pBADnuo His expression plasmid that encodes the entire E. coli nuo operon under the control of the inducible PBAD arabinose promoter [37]. The expression strain BW25113Δndh nuo:nptII_FRT was transformed with plasmids either encoding the original nuo‐genes or the corresponding mutations. Due to the lack of the alternative NADH dehydrogenase (ndh) [38] and the chromosomally encoded complex I, all NADH‐induced activities of membranes from this strain exclusively derive from complex I and the variants encoded on the plasmid.

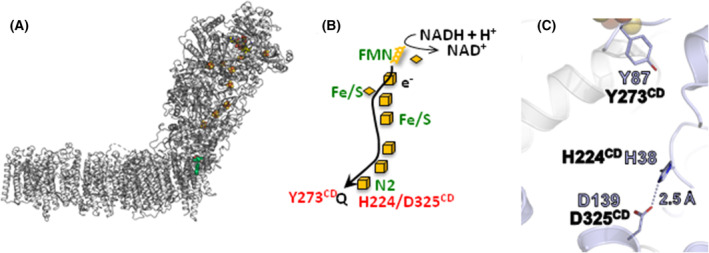

To screen for an effect of the mutations on complex I, the host strain individually transformed with the various plasmids was grown in minimal medium with acetate as non‐fermentable carbon source. Here, an intact complex I is required for fast growth to high OD values [38]. The mutant strains D325ACD and D325ECD grew as fast as the parental strain. Only the D325NCD and D325QCD mutant strains grew slightly slower (Fig. 2). This already suggests that complex I is fully assembled and active in the A and E mutants, while it may have a decreased activity in the N and Q mutants.

Fig. 2.

Growth of the nuoCD mutant strains and stability of the variants. (A) Growth curves of the reference strain producing parental complex I (black) and the D325CD mutant strains D325ACD (red), D325ECD (blue), D325NCD (green), and D325QCD (violet) in minimal medium with acetate as the only carbon source. The arrow marks the induction of gene expression with 0.02% (w/v) L‐arabinose. (B) Sucrose gradients of detergent solubilized membranes from the parental strain (black) and the nuoCD mutant strains D325ACD (red), D325ECD (blue), D325NCD (green) and D325QCD (violet). The NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity of each fraction is shown; the activities are normalized to 20 mg protein applied on each gradient.

The assembly of the complex I variants in the mutant strains was assessed by separating proteins extracted from cytoplasmic membranes with LMNG using sucrose gradient centrifugation (Fig. 2). The position of the complex and the variant proteins in the gradient was determined by their NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity. Parental complex I sediments around fraction 16 as expected [49]. The variants sedimented at the same position of the gradient with approximately the same total activity (Fig. 2) indicating a similar amount of protein in the mutant membranes. As an exception, the strain producing the D325ACD variant shows a significantly higher total activity than the parental strain (Fig. 2).

The amount of the complex and the variants in cytoplasmic membranes was also determined by measuring the NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity (Table 1). This activity is mediated by FMN bound to NuoF and is not coupled to Q reduction or proton pumping. The activity of the D325ACD mutant strain is significantly higher than that of the parental strain, while that of the D325ECD and D325QCD mutant strains is slightly diminished. The NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity of the D325NCD mutant membranes is only two thirds of that of the parental strain. These results are in good agreement with the activity profiles of the sucrose gradients (Fig. 2). For unknown reasons, the D325ACD mutant produces more of the variant than the parent strain of complex I. The physiological activity of complex I was determined by measuring the NADH oxidase activity of cytoplasmic membranes. In this assay, NADH is oxidized by complex I and the produced quinol is used by the quinol oxidases to reduce oxygen to water. The decrease of the oxygen concentration in the buffer is measured. Here, the D325ACD mutant strain showed a slightly diminished activity while that of the other mutant strains was half and one third of the parental strain, respectively (Table 1). Production of complex I from the nuo‐plasmids might lead to different amounts of the complex in the strains. To compensate for this difference, the NADH oxidase activity was normalized for the amount of complex I in the respective membranes as derived from the NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity (Table 1). Taking the different amount of complex I in the membrane into account, the D325ACD and D325ECD mutant strains exhibited about 60% and the other strains approximately half of the activity of the parental strain (Table 1). Thus, the mutations clearly diminished complex I electron transfer activity without blocking the reaction. This is in agreement with previous reports [26, 50]. The rapid growth of the mutant strain producing the D325ACD variant (Fig. 2) is explained by the fact that although the variant retains 62% of its physiological activity, this is compensated for by the production of 132% of the amount of the variant.

Table 1.

NADH oxidase and NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity of cytoplasmic membranes from E. coli parental strain (WT) and D325CD mutant strains. Data were obtained from three measurements of two biological replicates, the standard deviation is given.

| Strain | NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity | NADH oxidase activity | Normalized NADH oxidase activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (U⋅mg−1 total protein) | (%) | (U⋅mg−1 total protein) | (%) | (U⋅mg−1 total protein) | (%) | |

| WT | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 100 ± 5 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 100 ± 7 | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 100 ± 9 |

| D325ACD | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 132 ± 9 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 81 ± 3 | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 62 ± 10 |

| D325ECD | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 92 ± 9 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 55 ± 9 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 59 ± 10 |

| D325NCD | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 64 ± 18 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 31 ± 23 | 0.26 ± 0.06 | 50 ± 28 |

| D325QCD | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 80 ± 10 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 33 ± 21 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 43 ± 22 |

To determine the influence of the mutation on inhibitor binding, the NADH oxidase activity was titrated with piericidin A, a specific Q site inhibitor of complex I [40]. The IC50 for the parental membranes was 3.3 μm piericidin A (Table 2), which is in good agreement with previous data [40]. Remarkably, all D325CD mutants showed a significantly lower affinity to piericidin A. The D325ECD mutant strain that contains a longer acidic side chain exhibits an approximately two‐fold and membranes from the D325ACD mutant strain an approximately three‐fold higher IC50 (Table 2). Membranes from the mutants with an amide at this position, D325QCD and D325NCD, show high IC50 values of around 17 μm (Table 2). The latter indicates a disturbed binding of piericidin A at its binding site. This is in agreement with structural data indicating that H224CD, the ion‐pair binding partner of D325CD, is strongly involved in specific binding of piericidin A [16].

Table 2.

Inhibition of the NADH oxidase activity of cytoplasmic membranes from E. coli parental and nuoCD mutant strains. Data were obtained from two measurements of three biological replicates, the standard deviation is given.

| Strain | IC50 (piericidin A) |

|---|---|

| (μm) | |

| WT | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| D325ACD | 9.3 ± 0.8 |

| D325ECD | 6.2 ± 0.5 |

| D325NCD | 17.4 ± 0.6 |

| D325QCD | 16.9 ± 1.2 |

To clarify whether D325CD is the acidic amino acid residue that we identified to be protonated by the potential step from −0.3 to −0.1 V [24], complex I and the D325ACD variant were prepared to homogeneity by affinity and size‐exclusion chromatography (Fig. S1). The D325ACD variant was selected for comparison as the methyl protons show no signals in the region from 1800 to 1710 cm−1. From 50 g cells 7–10 mg of complex I and of the variant protein were obtained. The elution profiles and the SDS‐gel of the preparations of complex I and the variant show no significant differences (Fig. S1). The specific NADH/ferricyanide oxidoreductase activity of preparations of the D325ACD variant is 98 ± 3.5 U⋅mg−1 of the variant and thus, similar to that of complex I with 105 ± 2.8 U⋅mg−1 of complex I. Likewise, the variant showed about 61% (17.2 ± 0.4 U⋅mg−1 of the variant) of the specific NADH:decyl‐Q oxidoreductase activity of the parental complex (28.2 ± 2.4 U⋅mg−1 of complex I), which is in line with data obtained from membranes (Table 1). The NADH:decyl‐Q oxidoreductase activity of the isolated enzymes is used to measure electron transfer from NADH to the artificial substrate decyl‐Q, whereby the electrons follow the physiological path via the FMN and the FeS clusters to the Q binding site. The reaction is coupled with proton translocation, but this has no effect on the assay as the enzyme is not reconstituted in proteoliposomes.

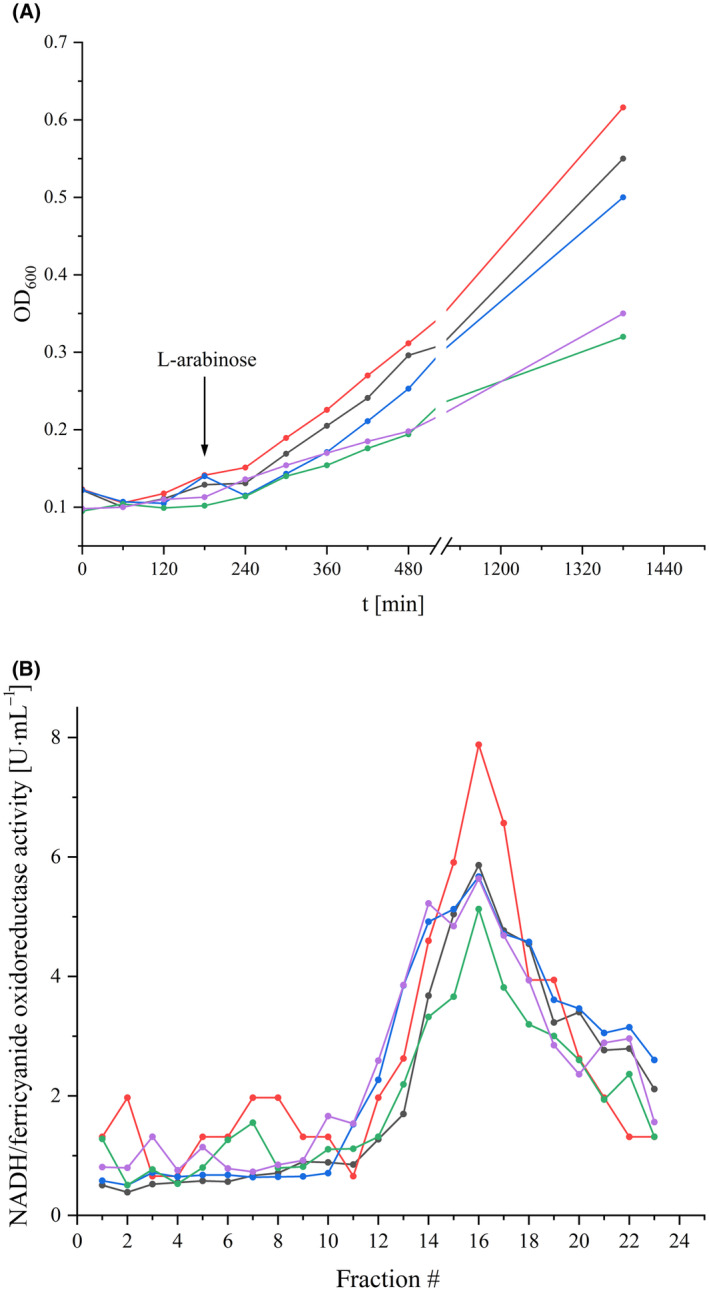

The redox‐dependent reorganizations of complex I and the contributions of titratable amino acid residues have been described by infrared spectroscopy [24]. The ν(C=O) modes of protonated aspartic and glutamic acid side chains contribute in the spectral range from 1800 to 1710 cm−1. This spectral region is highly characteristic for protonated acidic amino acid residues in membrane proteins [51, 52]. The spectra were recorded under the same experimental conditions as reported [24]. Accordingly, a potential step from −0.3 to −0.1 V was applied to both samples. In this range, tightly bound Q will be reduced and protonated and it will move away from its tight position in the cavity in proximity of N2 [23, 30]. Spectra of the complex and the variant were recorded from 1800 to 1200 cm−1 as in our original experiment (Fig. 3). The individual signals present in the redox difference spectra of complex I have already been discussed in detail [24]. Noteworthy, the spectra look highly similar to those obtained with the preparation of the chromosomally encoded complex in a different detergent [24]. The complex I difference spectra feature a clear signal at 1711 cm−1 as reported for the previously published preparation (Fig. 3). This signal contains contributions from the FMN and another group that was originally attributed to an acidic amino acid side chain due to its clearly lower intensity in the spectra of the NADH dehydrogenase fragment of the complex that contains the FMN but lacks cluster N2 and the Q binding site [24]. Comparison of redox difference spectra of complex I and the D325ACD variant reveals that the signal at 1711 cm−1 is nearly lost in the redox difference spectrum of the D325ACD variant (Fig. 3). Following our previous findings [24] the very low residual absorbance is attributed to the FMN. Since both spectra were recorded in a pH 6 buffer, the pKa of the residue in question should be higher than 6. Only a few acidic amino acid residues of complex I are predicted to have a pKa above 6 by using the PropKa3 software. According to these predictions, the pKa of D325CD, the aspartic acid residue that is the focus of our study, fulfills this requirement with a pKa of 8.3, which is consistent with the experimental data. Taking all experimental evidence together our data strongly suggest that this D325CD becomes deprotonated upon Q reduction at −0.3 V and protonated when the reduced and protonated QH2 moves away from N2 to another position in the Q cavity at −0.1 V.

Fig. 3.

(A) Oxidized minus reduced FTIR difference spectra of the complex I and the D325ACD variant at pH 6 in the −0.3/−0.1 V potential range. (B) Magnified view of the 1720–1670 cm−1 spectral range.

Discussion

Mutation of D325CD to A, E, N, and Q does not hamper the assembly of the complex (Fig. 2). However, these mutations clearly diminish the NADH:Q oxidoreductase activity normalized to the amount of the protein in the membrane (Table 1) in agreement with previous studies on the E. coli enzyme [26, 50]. As the mutations do not fully block activity, D325CD is not essential for the enzyme's activity. In contrast, based on the FTIR spectroscopic data, D325CD clearly is the amino acid residue that is deprotonated when the complex experiences a potential of −0.3 V and protonated at a potential of −0.1 V (Fig. 3).

There is a general agreement that Q is reduced by electron transfer from the most distal Fe/S cluster N2, when bound to the tight position in the Q binding cavity of complex I (Fig. 1) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. Most likely, Q is fully reduced to Q2− [26] that readily accepts protons from nearby donors. However, it is unclear whether Q2− is fully protonated at this position resulting in QH2 or whether a quinol anion QH− is formed instead [53]. Furthermore, the proton source is still under debate. From co‐crystallization of the Thermus thermophilus complex I with piericidin A and the substrate analog decyl‐Q, Baradaran et al. concluded that one of the redox‐active carbonyl groups interacts with Y273CD and the other one with H224CD (E. coli numbering, see Table S1) [6]. The same conserved Y273CD and H224CD residues were also identified by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations as obligate binding partners to enable redox‐driven proton translocation [23, 32, 33, 54, 55]. However, so far no structure has been solved in which the carbonyl groups of a long‐chain Q are bound by these two residues. Furthermore, biochemical data obtained with Y. lipolytica complex I indicate that these two residues might just ligate the two carbonyl groups to enable a proper positioning of the Q headgroup for electron transfer. Mutagenesis of these residues prevented the reaction with long‐chain Qs such as the native Q9, however, the isolated variants were fully active with short‐chain quinones such as Q1 and Q2 [31]. This could mean that these residues may not be involved in the protonation of the Q [16, 31].

H224CD forms an ion pair with D325CD that was proposed to open upon Q reduction and protonation, thus leading to deprotonation of D325CD by H224CD [26]. Our FTIR data show that the deprotonated carboxylate of D325CD is found in the reduced state at −0.3 V and that this side chain becomes protonated to a neutral carboxylic acid in the oxidized state at −0.1 V (Fig. 3). At −0.3 V, the potential at which Q is reduced, D325CD is therefore present in the deprotonated form. According to MD simulations, D325CD becomes deprotonated as soon as Q is reduced to the Q2− state by electron transfer from cluster N2 [26]. Q2− is rapidly protonated to QH2 from a yet unknown source, which could be the nearby conserved Y273CD and H224CD residues as discussed above [26]. According to quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics simulations, deprotonation of D325CD upon QH2 formation is accomplished by H224CD. Thus, our FTIR difference spectra fully support this suggestion (Fig. 3). Following the simulations [26], the anionic D325CD moves away from H224CD towards the membrane arm. This is enabled by D325CD being part of a conformationally flexible four‐helix bundle [6]. The movement of the anionic D325CD should induce conformational changes that are involved in driving proton translocation in the membrane arm [26]. Remarkably, the D325NCD variant was shown to be able to translocate protons. This was explained by the fact that this residue is part of a larger proton relay system [26].

Beyond the scope of the MD simulations, our experimental data now show that when QH2 moves from its low potential to its high‐potential position in the cavity at −0.1 V, D325CD becomes protonated, most likely after proton translocation in the membrane arm. The proton may derive from the electric ‘back‐wave’ in the membrane arm [23] or the charge re‐distribution in the membrane arm upon proton uptake from the cytosol [18]. Thus, we experimentally confirm the proposal that D325CD is in the deprotonated state during Q reduction [26] and show that it is in the protonated state when QH2 moves to its high‐potential binding site.

Author contributions

CH and FH constructed the expression plasmids, purified the proteins, performed the biochemical experiments and acquired the biochemical data, FM and PH recorded the FTIR spectra, CH, FM, FH, PH, and TF analyzed the data, DW performed pKa calculations, TF wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors, TF designed the study.

Peer review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1002/1873‐3468.15013.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Preparation of complex I and the D325ACD variant.

Table S1. Nomenclature of individual NuoCD positions in various organisms.

Table S2. Oligonucleotides used for site‐directed mutagenesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) by grants 278002225/RTG 2202 and SPP1927; FR 1140/11‐2 to TF and ANR‐10‐LABX‐0026_CSC to PH. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Edited by Peter Brzezinski

This is an Editor's Choice from the 9 December 2024 issue

Data accessibility

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Hirst J (2013) Mitochondrial complex I. Annu Rev Biochem 82, 551–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedrich T (2014) On the mechanism of respiratory complex I. J Bioenerg Biomembr 46, 255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sazanov LA (2015) A giant molecular proton pump: structure and mechanism of respiratory complex I. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16, 375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parey K, Wirth C, Vonck J and Zickermann V (2020) Respiratory complex I – structure, mechanism and evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol 63, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaila VRI (2021) Resolving chemical dynamics in biological energy conversion: long‐range proton‐coupled electron transfer in respiratory complex I. Acc Chem Res 54, 4462–4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baradaran R, Berrisford JM, Minhas GS and Sazanov LA (2013) Crystal structure of the entire respiratory complex I. Nature 494, 443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gnandt E, Dörner K, Strampraad MFJ, de Vries S and Friedrich T (2016) The multitude of iron‐sulfur clusters in respiratory complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta 1857, 1068–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cabrera‐Orefice A, Yoga EG, Wirth C, Siegmund K, Zwicker K, Guerrero‐Castillo S, Zickermann V, Hunte C and Brandt U (2018) Locking loop movement in the ubiquinone pocket of complex I disengages the proton pumps. Nat Commun 9, 4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grba D, Chung I, Bridges HR, Agip A‐NA and Hirst J (2023) Investigation of hydrated channels and proton pathways in a high‐resolution cryo‐EM structure of mammalian complex I. Sci Adv 9, eadi1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim H, Saura P, Pöverlein MC, Gamiz‐Hernandez AP and Kaila VRI (2023) Quinone catalysis modulates proton transfer reactions in the membrane domain of respiratory complex I. J Am Chem Soc 145, 17075–17086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weidner U, Geier S, Ptock A, Friedrich T, Leif H and Weiss H (1993) The gene locus of the proton‐translocating NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase in Escherichia coli. Organization of the 14 genes and relationship between the derived proteins and subunits of the mitochondrial complex I. J Mol Biol 233, 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braun M, Bungert S and Friedrich T (1998) Characterization of the overproduced NADH dehydrogenase fragment of the NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from Escherichia coli . Biochemistry 37, 1861–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agip A‐NA, Blaza JN, Fedor JG and Hirst J (2019) Mammalian respiratory complex I through the lens of Cryo‐EM. Annu Rev Biophys 48, 165–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fiedorczuk K, Letts JA, Degliesposti G, Kaszuba K, Skehel M and Sazanov LA (2016) Atomic structure of the entire mammalian respiratory complex I. Nature 538, 406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galemou Yoga E, Angerer H, Parey K and Zickermann V (2020) Respiratory complex I – mechanistic insights and advances in structure determination. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861, 148153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bridges HR, Fedor JG, Blaza NJ, Di Luca A, Jussupow A, Jarman OD, Wright JJ, Agip A‐NA, Gamiz‐Hernandez AP, Roessler MM et al. (2020) Structure of inhibitor‐bound mammalian complex. Nat Commun 11, 5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zheng W, Chai P, Zhu J and Zhang K (2024) High‐resolution in situ structures of mammalian respiratory supercomplexes. Nature 631, 232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kravchuk V, Petrova O, Kampjut D, Wojciechowska‐Bason A, Breese Z and Sazanov L (2022) A universal coupling mechanism of respiratory complex I. Nature 609, 808–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Di Luca A, Gamiz‐Hernandez AP and Kaila VRI (2017) Symmetry‐related proton transfer pathways in respiratory complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114, E6314–E6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kampjut D and Sazanov L (2020) The coupling mechanism of mammalian respiratory complex I. Science 370, eabc4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laube E, Meier‐Credo J, Langer JD and Kühlbrandt W (2022) Conformational changes in mitochondrial complex I of the thermophilic eukaryote Chaetomium thermophilum . Sci Adv 8, eadc 9952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaila VRI and Wikström M (2021) Architecture of bacterial respiratory chains. Nat Rev Microbiol 19, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaila VRI (2018) Long‐range proton‐coupled electron transfer in biological energy conversion: towards mechanistic understanding of respiratory complex I. J R Soc Interface 15, 20170916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hellwig P, Scheide D, Bungert S, Mäntele W and Friedrich T (2000) FT‐IR spectroscopic characterization of NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from Escherichia coli: oxidation of FeS cluster N2 is coupled with the protonation of an aspartate or glutamate side chain. Biochemistry 39, 10884–10891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Flemming D, Hellwig P, Lepper S, Kloer DP and Friedrich T (2006) Catalytic importance of acidic amino acids on subunit NuoB of the Escherichia coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). J Biol Chem 281, 24781–24789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharma V, Belevich G, Gamiz‐Hernandez AP, Róg T, Vattulainen I, Verkhovskaya ML, Wikström M, Hummer G and Kaila VRI (2015) Redox‐induced activation of the proton pump in the respiratory complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 11571–11576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chung I, Wright JJ, Bridges HR, Ivanov BS, Biner O, Pereira CS, Arantes GM and Hirst J (2022) Cryo‐EM structures define ubiquinone‐10 binding to mitochondrial complex I and conformational transitions accompanying Q‐site occupancy. Nat Commun 13, 2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verkhovsky M, Bloch DA and Verkhovskaya M (2012) Tightly‐bound ubiquinone in the Escherichia coli respiratory complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta 1817, 1550–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Verkhovskaya M and Wikström M (2014) Oxidoreduction properties of bound ubiquinone in complex I from Escherichia coli . Biochim Biophys Acta 1837, 246–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wikström M, Sharma V, Kaila VRI, Hosler JP and Hummer G (2015) New perspectives on proton pumping in cellular respiration. Chem Rev 115, 2196–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tocilescu MA, Fendel U, Zwicker K, Kerscher S and Brandt U (2007) Exploring the ubiquinone binding cavity of respiratory complex I. J Biol Chem 282, 29514–29520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Warnau J, Sharma V, Gamiz‐Hernandez AP, Di Luca A, Haapanen O, Vattulainen I, Wikström M, Hummer G and Kaila VRI (2018) Redox‐coupled quinone dynamics in the respiratory complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115, E8413–E8420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gamiz‐Hernandez AP, Jussupow A, Johansson MP and Kaila VRI (2017) Terminal electron‐proton transfer dynamics in the quinone reduction of respiratory complex I. J Am Chem Soc 139, 16282–16288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. The UniProt Consortium (2023) UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D523–D531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Datsenko KA and Wanner BL (2000) One‐step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K‐12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97, 6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burschel S, Kreuzer Decovic D, Nuber F, Stiller M, Hofmann M, Zupok A, Siemiatkowska B, Gorka M, Leimkühler S and Friedrich T (2019) Iron‐sulfur cluster carrier proteins involved in the assembly of Escherichia coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). Mol Microbiol 111, 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pohl T, Uhlmann M, Kaufenstein M and Friedrich T (2007) Lambda red‐mediated mutagenesis and efficient large scale affinity purification of the Escherichia coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). Biochemistry 46, 10694–10702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nuber F, Schimpf J, di Rago J‐P, Tribouillard‐Tanvier D, Procaccio V, Martin‐Negrier M‐L, Trimouille A, Biner O, von Ballmoos C and Friedrich T (2021) Biochemical consequences of two clinically relevant ND‐gene mutations in Escherichia coli respiratory complex I. Sci Rep 11, 12641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schimpf J, Oppermann S, Gerasimova T, Santos Seica AF, Hellwig P, Grishkovskaya I, Wohlwend D, Haselbach D and Friedrich T (2022) Structure of the peripheral arm of a minimalistic respiratory complex I. Structure 30, 80–94.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Friedrich T, van Heek P, Leif H, Ohnishi T, Forche E, Kunze B, Jansen R, Trowitzsch‐Kienast W, Höfle G, Reichenbach H et al. (1994) Two binding sites of inhibitors in NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). Relationship of one site with the ubiquinone‐binding site of bacterial glucose:ubiquinone oxidoreductase. Eur J Biochem 219, 691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Friedrich T, Hofhaus G, Ise W, Nehls U, Schmitz B and Weiss H (1989) A small isoform of NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) without mitochondrially encoded subunits is made in chloramphenicol‐treated Neurospora crassa . Eur J Biochem 180, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moss D, Nabedryk E, Breton J and Mäntele W (1990) Redox‐linked conformational changes in proteins detected by a combination of infrared spectroscopy and protein electrochemistry. Evaluation of the technique with cytochrome c . Eur J Biochem 187, 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Melin F and Hellwig P (2020) Redox properties of the membrane proteins from the respiratory chain. Chem Rev 120, 10244–10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hellwig P, Behr J, Ostermeier C, Richter O‐MH, Pfitzner U, Odenwald A, Ludwig B, Michel H and Mäntele W (1998) Involvement of glutamic acid 278 in the redox reaction of the cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans investigated by FT‐IR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 37, 7390–7399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gornall AG, Bardawill CJ and David MM (1949) Determination of serum proteins by means of the biuret reaction. J Biol Chem 177, 751–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gill SC and von Hippel PH (1989) Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem 182, 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schägger H and von Jagow G (1987) Tricine‐sodium dodecyl sulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem 166, 368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Olsson MHM, Sondergaard CR, Rostkowski M and Jensen JH (2011) PROPKA3: consistent treatment of internal and surface residues in empirical pKa predictions. J Chem Theory Comput 7, 525–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leif H, Sled VD, Ohnishi T, Weiss H and Friedrich T (1995) Isolation and characterization of the proton‐translocating NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli . Eur J Biochem 230, 538–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sinha PK, Castro‐Guerrero N, Patki G, Sato M, Torres‐Bacete J, Sinha S, Miyoshi H, Matsuno‐Yagi A and Yagi T (2015) Conserved amino acid residues of the NuoD segment important for structure and function of Escherichia coli NDH‐1 (complex I). Biochemistry 54, 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hellwig P, Barquera B and Gennis RB (2001) Direct evidence for the protonation of aspartate‐75, proposed to be at a quinol binding site, upon reduction of cytochrome bo 3 from Escherichia coli . Biochemistry 40, 1077–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zscherp C, Schlessinger R, Titor J, Oesterhelt D and Heberle J (1999) In situ determination of transient pKa changes of internal amino acids of bacteriorhodopsin by using time‐resolved attenuated total reflection Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 5496–5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Djurabekova A, Lasham J, Zdorevskyi O, Zickermann V and Sharma V (2024) Long‐range electron proton coupling in respiratory complex I – insights from molecular simulations of the quinone chamber and antiporter‐like subunits. Biochem J 481, 499–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Röpke M, Riepl D, Saura P, Di Luca A, Mühlbauer ME, Jussupow A, Gamiz‐Hernandez AP and Kaila VRI (2021) Deactivation blocks proton pathways in the mitochondrial complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118, e2019498118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Teixeira MH and Arantes GM (2019) Balanced internal hydration discriminates substrate binding to respiratory complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta 1860, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Preparation of complex I and the D325ACD variant.

Table S1. Nomenclature of individual NuoCD positions in various organisms.

Table S2. Oligonucleotides used for site‐directed mutagenesis.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.