Abstract

Background

Common mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, are estimated to affect up to 15% of the UK population at any one time, and health care systems worldwide need to implement interventions to reduce the impact and burden of these conditions. Collaborative care is a complex intervention based on chronic disease management models that may be effective in the management of these common mental health problems.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of collaborative care for patients with depression or anxiety.

Search methods

We searched the following databases to February 2012: The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) trials registers (CCDANCTR‐References and CCDANCTR‐Studies) which include relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from MEDLINE (1950 to present), EMBASE (1974 to present), PsycINFO (1967 to present) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, all years); the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (ICTRP); ClinicalTrials.gov; and CINAHL (to November 2010 only). We screened the reference lists of reports of all included studies and published systematic reviews for reports of additional studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of collaborative care for participants of all ages with depression or anxiety.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent researchers extracted data using a standardised data extraction sheet. Two independent researchers made 'Risk of bias' assessments using criteria from The Cochrane Collaboration. We combined continuous measures of outcome using standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We combined dichotomous measures using risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs. Sensitivity analyses tested the robustness of the results.

Main results

We included seventy‐nine RCTs (including 90 relevant comparisons) involving 24,308 participants in the review. Studies varied in terms of risk of bias.

The results of primary analyses demonstrated significantly greater improvement in depression outcomes for adults with depression treated with the collaborative care model in the short‐term (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.27; RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43), medium‐term (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.15; RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48), and long‐term (SMD ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.24; RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.41). However, these significant benefits were not demonstrated into the very long‐term (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.27).

The results also demonstrated significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes for adults with anxiety treated with the collaborative care model in the short‐term (SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.17; RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.87), medium‐term (SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.19; RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.69), and long‐term (SMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.34 to ‐0.06; RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.42). No comparisons examined the effects of the intervention on anxiety outcomes in the very long‐term.

There was evidence of benefit in secondary outcomes including medication use, mental health quality of life, and patient satisfaction, although there was less evidence of benefit in physical quality of life.

Authors' conclusions

Collaborative care is associated with significant improvement in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual care, and represents a useful addition to clinical pathways for adult patients with depression and anxiety.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Interprofessional Relations, Anxiety, Anxiety/therapy, Case Management, Case Management/organization & administration, Depression, Depression/therapy, Patient Care Team, Patient Care Team/organization & administration, Primary Health Care, Primary Health Care/organization & administration, Psychiatric Nursing, Psychiatry, Psychology, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Standard of Care

Plain language summary

Collaborative care for people with depression and anxiety

Many people suffer from depression and anxiety. These problems can make people feel sad, scared and even suicidal, and can affect their work, their relationships and their quality of life. Depression and anxiety can occur because of personal, financial, social or health problems.

‘Collaborative care’ is an innovative way of treating depression and anxiety. It involves a number of health professionals working with a patient to help them overcome their problems. Collaborative care often involves a medical doctor, a case manager (with training in depression and anxiety), and a mental health specialist such as a psychiatrist. The case manager has regular contact with the person and organises care, together with the medical doctor and specialist. The case manager may offer help with medication, or access to a ‘talking therapy’ to help the patient get better.

Collaborative care has been tested with patients in a number of countries and health care systems, but it is not clear whether it should be recommended for people with depression or anxiety.

In this review we found 79 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (90 comparisons) including 24,308 patients worldwide, comparing collaborative care with routine care or alternative treatments (such as consultation‐liaison) for depression and anxiety. There were problems with the methods in some of the studies. For example, the methods used to allocate patients to collaborative care or routine care were not always free from bias, and many patients did not complete follow‐up or provide information about their outcomes. Most of the studies focused on depression and the evidence suggests that collaborative care is better than routine care in improving depression for up to two years. A smaller number of studies examined the effect of collaborative care on anxiety and the evidence suggests that collaborative care is also better than usual care in improving anxiety for up to two years. Collaborative care increases the number of patients using medication in line with current guidance, and can improve mental health related quality of life. Patients with depression and anxiety treated with collaborative care are also more satisfied with their treatment.

Background

Description of the condition

Common mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, are highly prevalent with estimates of up to 15% of the UK population affected at any one time (NICE 2011a). The prevalence of individual common mental health disorders varies considerably. The one‐week prevalence rates from the Office of National Statistics 2007 national survey were 4.4% for generalised anxiety disorder, 3.0% for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 2.3% for depression, 1.4% for phobias, 1.1% for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and 1.1% for panic disorder (McManus 2009). Worldwide, depression affects about 154 million people, and an estimated 5.8% of men and 9.5% of women will experience a depressive episode in any given year (WHO 2001a).

Depression and anxiety are a major cause of disease burden and disability (Ustun 2004) with depression projected to become one of the three leading causes of burden of disease by 2030 (Mathers 2006). Symptoms of depression include: depressed mood; loss of interest or pleasure in activities; insomnia or sleeping too much; and fatigue or loss of energy. Symptoms of anxiety differ but can include: excessive worry; feeling tense or restless; significant tension in muscles; and irritability (APA 2000). The impact of both disorders on social and occupational functioning, physical health and mortality is also substantial (Ormel 1999), and often anxiety and depression present together, disabling the person further (NICE 2011a). Depression also accounts for two‐thirds of all suicides (Sartorius 2001).

Depression and anxiety are often chronic in nature, characterised by high rates of relapse and recurrence. Following their first episode of depression, at least 50% of people will go on to have one or more further episode(s), with the risk of relapse increasing to 70% after the second episode, and as high as 90% after a third episode (Kupfer 1991).

Description of the intervention

It is estimated that up to 90% of patients diagnosed with depression and anxiety are treated solely in primary care (NICE 2011a). However, the management of these disorders is often suboptimal (NHS 2002). The most common method of treatment for common mental health disorders in primary care is psychotropic medication (NICE 2011a). There are problems with this approach, as patients do not take the medication as prescribed for a variety of reasons including fears of addiction, dependency and side effects (Lingam 2002). Care for patients with chronic problems like depression is often not proactive; patients do not receive ongoing monitoring and care designed to reduce the burden of disorder and the likelihood of recurrence and relapse (Buszewicz 2011).

It has been recognised that improving the treatment of common mental health problems is a very complex task which requires changes to the way care is provided, together with additional resources to develop the appropriate systems to enable primary care professionals to deliver high quality care (Gilbody 2003a; Katon 1997; Katon 2001). Four distinct models of quality improvement in common mental health problems have been identified: training primary care staff, consultation‐liaison, replacement/referral, and collaborative care (Bower 2005).

The collaborative care model is based on the principles of chronic disease management applied to conditions such as diabetes. The model can involve a large number of different interventions including: screening, education of patients, changes in practice routines, and developments in information technology (Wagner 1996). Collaborative care models are exemplars of 'complex interventions' which consist of a number of separate elements, where the particular elements that function as the ‘active ingredient’ can be difficult to identify (Medical Research Council 2008).

The term 'collaborative care' was first used to describe an intervention which was delivered by a primary care provider and a psychiatrist (Katon 1995a). However, there have been significant developments in the model since that time, and thus clear specification of the meaning of the term in line with current thinking is important. A widely accepted definition of collaborative care used in a systematic review of complex system interventions requires that four key criteria are met: a multi‐professional approach to patient care, structured management plan, scheduled patient follow‐ups, and enhanced inter‐professional communication (Gunn 2006).

How the intervention might work

Research has suggested that a key aspect of effective collaborative care is 'case management' (Gilbody 2003a). Case management has been described as a health worker taking responsibility for proactively following up patients, assessing patient adherence to psychological and pharmacological treatments, monitoring patient progress, taking action when treatment is unsuccessful, and delivering psychological support (Von Korff 2001). Case managers work closely with the primary care provider (who retains overall clinical responsibility) and can receive regular supervision from a mental health specialist (Gilbody 2003a; Katon 2001).

Why it is important to do this review

Collaborative care is a model of care for common mental health problems which has generated worldwide interest in its effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness. Although a number of reviews of collaborative care have been published, significant uncertainties remain. Many trials are from the United States, and their generalisability to other contexts and health care systems is unclear. Effectiveness may vary by patient population; collaborative care was not recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) for depression (NICE 2010) or anxiety (NICE 2011b), but was recommended for depression in patients with chronic disease (NICE 2009). The evidence base for collaborative care is also rapidly developing. Mental health policy in the UK highlights the importance of patient choice in treatments for mental health problems, and collaborative care could provide another option for services to complement other proven treatments. This review will consolidate the developing body of evidence on collaborative care and provide an up‐to‐date and rigorous assessment to inform policy and practice.

Objectives

This review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression and anxiety.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics: Trial participants were either male or female patients of any age.

Diagnosis: Trial participants had a primary diagnosis of depression (including: acute, chronic, persistent, remitted, subthreshold and postnatal) or anxiety (including: generalised anxiety, panic, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobias, social anxiety, health anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)). Diagnosis of trial participants was according to one of the following: 1) diagnosis made by primary care provider; 2) Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (APA 2000) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (WHO 1992) criteria; or 3) assessment through self‐rated or clinician‐rated validated instruments, e.g. Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ‐9) (Kroenke 2001), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1987) and/or Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988). Some studies included a mixed population, of which only a proportion were depressed or anxious (e.g. where studies included a mix of patients who were at‐risk drinking, suicidal or depressed). These were included only if the majority (>= 50%) of participants were depressed and/or anxious, to ensure that the results of the study related to our target group.

Comorbidity: Trial participants could also have long‐term conditions (i.e. asthma, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), as well as a common mental health problem.

Setting: Trial participants could be identified in a variety of healthcare settings (excluding in‐patient/specialist mental health), but the intervention had to be predominantly delivered in primary care or community settings.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

This review has adopted four key collaborative care criteria (Gunn 2006). We regarded studies as collaborative care studies if they fulfilled the following criteria.

A multi‐professional approach to patient care. A primary care provider (general practitioner, family physician, primary care physician or a specialist providing undifferentiated medical care) and at least one other health professional (e.g. nurse, psychologist, psychiatrist, or pharmacist) or paraprofessional is involved with patient care. For the purposes of the current review, we characterised primary care as medical care involving first contact and ongoing care to patients, regardless of the patient's age, gender or presenting problem (Boerma 1999; WHO 2001b).

A structured management plan. Introduction of an organised approach to patient care including access to evidence based management information in the form of guidelines or protocols. Management included either or both pharmacological (e.g. antidepressant medication) and non‐pharmacological interventions (e.g. patient and provider education, counselling, or cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)).

Scheduled patient follow‐ups. An organised approach to patient follow‐up defined as one or more scheduled telephone or in‐person follow‐up appointments to provide specific interventions, facilitate treatment adherence, or monitor symptoms or adverse effects.

Enhanced inter‐professional communication. Introduction of mechanisms to facilitate communication between professionals caring for the patient, including team meetings, case conferences, individual consultation/supervision, shared medical records, and patient‐specific written or verbal feedback between care‐givers.

Comparator interventions

We included studies that compared collaborative care with 'usual care' (for example, routine primary care, waiting lists, or untreated groups identified through screening) or collaborative care with other interventions.

Based on analysis of studies identified in the review, we distinguished the following three types of usual care.

Studies that provided no additional intervention in the usual care group, including no notification of patient depression status.

Studies that provided additional interventions in the usual care group (such as education of primary care providers, or notification of patient depression status), but where these aspects of the intervention were applied to both arms, and potentially cancelled out.

Studies that enhanced usual care by providing an intervention that the collaborative care arm did not receive e.g. where only primary care clinicians in the usual care arm received training and educational materials on depression evaluation and treatment (Asarnow 2005).

Based on analysis of studies identified in the review, we distinguished the following three types of ‘active comparisons’.

‘Alternative interventions’ such as feedback alone, consultation‐liaison and enhanced referral, which were compared with collaborative care.

'Enhancements of collaborative care’ such as collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison, and collaborative care plus psychotherapy, which were compared with collaborative care.

‘Models of collaborative care interventions’ such as collaborative care (medication) versus collaborative care (psychotherapy), which were compared directly.

Types of outcome measures

Where relevant (i.e. for the effects of collaborative care on depression) we reported both continuous and dichotomous outcomes. For dichotomous outcomes, studies generally reported either ‘response' outcomes (i.e. a ≥ 50% reduction in symptom scores from baseline) or 'remission' (patients at each time point with scores under a particular threshold). For consistency, we reported response outcomes where possible.

Primary outcomes

Change in depression or anxiety, as measured by observer or patient self‐report.

Secondary outcomes

Medication for depression and/or anxiety. This was reported as the proportion of patients using medication, proportions meeting predefined levels of use, or proportions with ‘appropriate’ use according to guidelines or other measures. Such data could be based on administrative data or patient self‐report. We pooled data relating to rates of use and adherence, and administrative data and self‐report.

We included the following outcomes only when a validated tool was used.

Social functioning, e.g. Social Adaptation Self‐evaluation Scale (SASS) (Bosc 1997).

Quality of life, e.g. Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36, SF‐12) (Ware 1993).

Patient satisfaction, e.g. Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) (Attkinson 2003).

Timing of outcome assessment

We categorised outcomes as short‐term (0 to 6 months), medium‐term (7 to 12 months), long‐term (13 to 24 months), and very long‐term (25 months or more). We rounded down studies that reported unconventional follow‐up points (e.g. 27 weeks).

Search methods for identification of studies

CCDAN's Specialised Register

The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintain two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK; a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 29,500 reports of trials in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 65% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual. Further details are available from the CCDAN Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC). Reports of trials for inclusion in the registers are collated from routine (weekly) generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to present), EMBASE (1974 to present), and PsycINFO (1967 to present); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organization's (WHO's) trials portal (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), drug companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies can be found on the Group‘s website.

Electronic searches

We searched the CCDAN registers (to 9th February 2012) using the following terms.

1. CCDANCTR‐Studies Condition = (depress* or dysthymi* or anxiety or anxious or panic or *phobi* or obsessi* or compulsi* or post‐traumatic) and Intervention = (“care manag*” or "case manage*" or collaborat* or ”disease manag*" or “enhanced care” or “managed care” or multicomponent or multi‐component or multidisciplinary or multi‐disciplinary or stepped)

2. CCDANCTR‐References The CCDANCTR‐References Register was searched using a more sensitive set of terms to identify additional untagged/uncoded references: 1. (depress* or dysthymi* or anxiety or anxious or *phobi* or PTSD or post‐trauma* or “post trauma*” or postrauma* or panic or OCD or obsessi* or compulsi* or GAD) [ti, ab, kw] 2. ((collaborat* or coordinat* or co‐ordinat* or shared or integrat* or stepped or systematic) AND (care or healthcare or “health care” or working or intervention* or service or model or effort* or manage*)) [free‐text] 3. ((augment* or enhance*) AND (care* or healthcare or “health care” or communicat*)) [free‐text] 4. (“care manage*” or "case manage*" or “chronic care*” or “complex intervention*” or “cooperative behav*” or “co‐operative behav*” or “joint working” or pathway or interprofessional or inter‐professional or interdisciplinary or inter‐disciplinary or multidisciplin* or multi‐disciplin* or multiprofession* or multi‐profession* or transdisciplin* or trans‐disciplin* or multifacet* or multi‐facet* or “complex intervention*” or “multiple intervention*” or multi‐intervention* or “organisational intervention*” or “organizational intervention*” or “interpersonal relation*” or “ inter‐personal relation*” or “interinstitutional relation*” or “inter‐institutional relation*” or “consultation liaison” or algorithm* or “treatment guideline*” or “treatment protocol*” or “treatment delivery” or “treatment model” or adherence or compliance or concordance or “patient care team” or “patient care management” or “patient care planning” or “case management” or “managed care program*” or “delivery of healthcare” or “continuity of patient care” or “professional‐patient relations” or “interprofessional relations”) [free‐text] 5. (1 and (2 or 3 or 4))

3. CINAHL (1982 to 11th November 2010) We conducted an additional search on CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health) (search strategy in Appendix 1).

4. International Trial Registers We also carried out searches on the WHO trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify ongoing or unpublished studies using the terms: ("stepped care" or "collaborative care" or interprofessional or interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary). We imported and filtered results into Excel using terms for depression and anxiety.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of reports of all included studies and other systematic reviews for additional published, unpublished or ongoing research.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (JA and PB) independently scanned the identified studies and excluded studies according to the criteria above, on the basis of titles and abstracts. We retrieved full copies of the studies deemed eligible by one of the team (JA) for closer examination. If there was uncertainty or disagreement, we reached consensus by discussion and consultation with another review author (PB, DR or SG). A log of all studies which initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but which we later excluded on retrieval of the full‐text are detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. We kept a record of the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Content data were extracted by JA, DR, KL and LG and double‐extracted by research assistants/associates. Outcome data were extracted by PB and research assistants. A standardised data extraction form was used for the following characteristics.

The patient population (demographic and clinical characteristics).

The nature of the intervention (e.g. types of interventions used, contact between patient and professional, and amount of collaboration between professionals).

Internal validity (assessment of risk of bias).

External validity (context of recruitment and methods of recruitment).

We presented analyses using the following structure. In the analysis of primary outcomes we distinguished all collaborative care interventions, separating studies by diagnosis (depression and anxiety) and age (adolescents and adults). Therefore analyses 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 report outcomes for depression in adults, analyses 1.4, 1.5 and 1.6 report outcomes for anxiety in adults and analyses 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 report outcomes for depression in adolescents. No studies reported anxiety outcomes in adolescents.

We separately analysed primary outcomes reported as dichotomous outcomes and as continuous outcomes. Each type of outcome was reported at four time periods: 0 to 6 months, 7 to 12 months, 13 to 24 months, and 25+ months.

For the secondary outcome of medication use, we applied the same analytical methods. The majority of studies reported medication use using dichotomous outcomes; we excluded the minority reporting continuous outcomes.

For the secondary outcome of quality of life, we combined analyses across collaborative care interventions for patients with depression and anxiety. The majority of studies reported quality of life using continuous outcomes; we excluded the minority reporting dichotomous outcomes. We split quality of life outcomes into mental health quality of life (e.g. SF‐36 emotional role, SF‐mental component score), and physical health quality of life (e.g. SF‐36 physical functioning, SF‐physical component score). We excluded measures that did not report separate mental health and physical health dimensions (e.g. EQ5D overall utility).

For satisfaction outcomes, we combined analyses across collaborative care intervention for patients with depression and anxiety. We analysed satisfaction outcomes reported as dichotomous outcomes and continuous outcomes separately. We only reported a single satisfaction outcome point for each study, choosing the outcome closest to six months as the likely best indicator of patient experience of the intervention, unaffected by memory or other bias.

As part of the protocol, we intended to report on social function outcomes. However, a very wide variety of social function outcome measures were reported, and there was a lack of clarity over their definition, scope, and comparability. It was therefore not possible to produce a rigorous synthesis in the time frame of the review. We have extracted social function outcomes and may report on these in a later update of the review when a suitable typology has been developed to ensure consistency in analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, one review author (JA, PC, CD or DR) and one research assistant/associate independently applied The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011b). This tool encourages consideration of:

selection bias due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence;

selection bias due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment;

performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study (blinding);

detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors (blinding);

attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data;

reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting;

bias due to integrity of the intervention; and

bias due to other problems, such as:

any potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; or

claims to have been fraudulent; or

some other problem.

We used our comments to show how we assessed the risk of bias, with judgements of either low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias, or high risk of bias. If there was uncertainty or disagreement, we reached consensus by discussion and consultation with another review author (PC).

Measures of treatment effect

Studies in the review reported both dichotomous (e.g. recovered/not recovered) and continuous outcomes (such as patient scores on self‐reported outcome scales). For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes, as a range of different measures were used, we calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) and 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials

As collaborative care is an organisational intervention, cluster trials are commonly used as a way of avoiding bias associated with contamination. We identified studies using cluster randomisation and we adjusted the precision of analyses based on these studies in the meta‐analysis using the ‘effective sample size’ method outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (section 16.3.4) (Higgins 2011a). We calculated the effective sample size of groups in each cluster trial on the basis of the original sample size divided by the ‘design effect’. The design effect was calculated by 1 + (M – 1) ICC, where M represents the average cluster size and ICC is the intracluster correlation coefficient. We assumed a common design effect across groups. For the base analysis we assumed an intra‐class correlation of 0.02 (Adams 2004). We examined the effect of adjustment for clustering in a sensitivity analysis using intra‐class correlations of 0.00 and 0.05 (Donner 2002).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where studies reported multiple collaborative care interventions against a single control we extracted each collaborative care intervention as a separate comparison and entered them where relevant in the meta‐analysis, dividing the control group sample size appropriately to avoid double‐counting in the analysis. Where a study reported a single collaborative care intervention against two different types of controls (individual and cluster controls) we treated this as two separate comparisons, dividing the intervention group sample size to avoid double‐counting in the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We distinguished between two types of ‘loss’ of data: patients who did not complete their assigned collaborative care treatment (‘treatment completion’) and patients who did not complete follow‐up for assessment of outcome (‘loss to follow‐up’).

For ‘treatment completion’, we assessed whether the study used an appropriate 'intention‐to‐treat' analysis (including all patients in the analysis irrespective of treatment completion) or ‘per protocol’ analysis (excluding patients who did not complete treatment according to some defined criterion). We describe the approaches used by individual studies in Characteristics of included studies.

To assess 'loss to follow‐up' in included studies, we also calculated the proportion of randomised patients who were lost to follow‐up at the 0 to 6 month follow‐up across arms, and within each arm, and also calculated the difference in the proportions between collaborative care and usual care arms.

Data for the meta‐analysis were missing for many outcomes, usually in terms of missing standard deviations (SDs) and sample sizes. In a change from the study protocol, we did not contact all authors to collect missing data as it was not possible to complete this task in the time available for the review. We did contact two authors for data in order to allow us to include their studies in the review (McCusker 2008; Rost 2001a; Rost 2001b) as the data reported in the published papers was not in the form required. We did not impute missing data required for calculations of treatment effect (e.g. missing SDs), but we did recalculate necessary parameters from published data (e.g. calculating SDs from published standard errors). When we update the review we will impute data for meta‐regression analysis to maximise the numbers of studies available for the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity using the I² statistic, an estimate of the percentage of total variation across studies that can be attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance. This statistic is interpreted as follows: 0% to 40% might not be important, 30% to 60% might represent moderate levels of heterogeneity, 50% to 90% might represent substantial levels of heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2011). We calculated the 95% confidence intervals around the I2 estimate using the Stata command heterogi. In the original protocol, we planned to use a random‐effects model where a moderate to high (50% or more) level of statistical heterogeneity was found (Higgins 2003). However, given the high levels of clinical and methodological heterogeneity in terms of participants, interventions, comparisons and outcome measures (see Characteristics of included studies), we used random‐effects models in all analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We examined funnel plots to test for asymmetry which can indicate a number of issues including: selection bias (such as publication bias), poor methodological quality, and true heterogeneity (Egger 1997). We also reported any instances of selective outcome reporting in the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

Data synthesis

We used a random‐effects model for all meta‐analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

From previous analyses we expected heterogeneity in terms of treatment effects across different populations and types of interventions and we planned to examine these. Our primary analysis was collaborative care versus usual primary care. Other planned secondary analyses were to examine comparisons of different study designs, participants and types of collaborative care. This would include:

-

types of participants

country (United States, other)

location of recruitment (primary care, community, specialist, mixed); and location of delivery (primary care, community, specialist, mixed)

ethnicity (75% or more white, other)

baseline severity (subthreshold, met criteria for major depressive or anxiety disorder, mixed)

-

the complexity of the intervention

types of professionals (primary care provider and case manager, or primary care provider, case manager and mental health specialist)

intervention intensity (measures of sessions, and sessions multiplied by session length)

intervention content (medication management alone, psychological intervention alone, and combined).

We had planned to undertake a series of exploratory analyses using meta‐regression, to examine the influence of these and other study‐level factors in predicting the magnitude and direction of outcomes (Thompson 2002). We had planned to assess the significance of predictive factors (selected a priori and outlined above) in explaining between‐study heterogeneity, as measured by the I² statistic, according to the method proposed in (Higgins 2004).

We did not undertake these further exploratory analyses due to time constraints, but it is envisaged that we will include them in the review update.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the effects of excluding certain types of studies: cluster trials; trials including patients on the basis of comorbid physical conditions; studies considered at high risk of bias based on concealment of allocation methods and attrition (studies with > 20% loss to follow‐up). We conducted these sensitivity analyses only on depression outcomes (both continuous and dichotomous) at six months.

Following review, we also conducted a posthoc sensitivity analysis on intervention length. Our analysis of outcomes was based on time since randomisation (0 to 6 months, 7 to 12 months, 13 to 24 months, 25+ months), but some collaborative care interventions continue for periods of greater than six months, and it is possible that the longer‐term effects of collaborative care (i.e. those in the 7‐ to 12‐month period and beyond) do not reflect any enduring effect of the intervention, but simply reflect those interventions that are extended beyond the initial outcome period (0 to 6 months). To assess this possibility, we coded studies as to whether the intervention is completed in the 0‐ to 6‐month outcome point, or extended beyond that. In a sensitivity analysis, we removed those studies where the intervention extended beyond six months, to assess whether the effects found at the 7‐ to 12‐month time point were significantly different when studies with longer‐term interventions were excluded.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

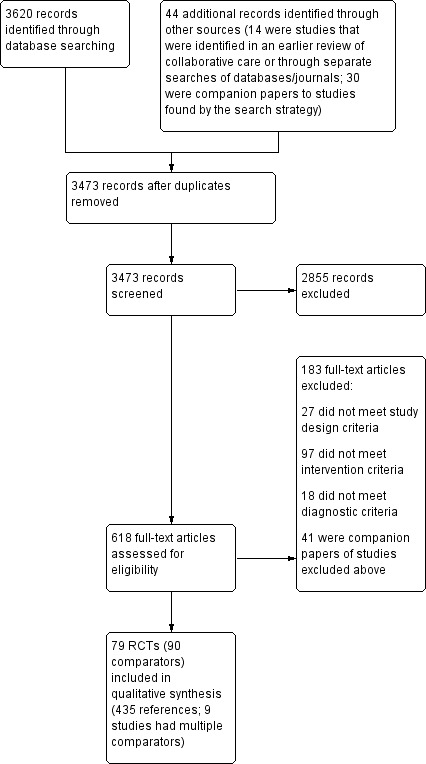

After removal of duplicates, we identified 3473 references from the searches. After assessing the titles and abstracts we checked 618 full‐texts, and included 79 randomised controlled studies (90 individual comparisons) in the review (435 references; nine studies had multiple comparisons) (see flow diagram in Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 79 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (90 comparisons) involving 24,308 participants in the review.

The ‘Characteristics of included studies’ table details the characteristics of the studies, including study design, the characteristics of participants, the characteristics of interventions and outcome measures. These are summarised for the 90 comparisons below (figures are rounded to nearest whole numbers, and so the overall percentage does not always equal 100).

Design

All included comparisons were RCTs; 21 (23%) comparisons used cluster randomisation, where the unit of randomisation was either a primary care practice (n = 19) or a primary care provider (n = 2).

Setting

Sixty‐eight comparisons (76%) were conducted in the US; 10 (11%) in the UK; five (6%) in other European countries (Germany, The Netherlands); and seven (8%) from other countries (Canada, Chile, India, Puerto Rico).

Sixty‐nine comparisons (77%) recruited participants from primary care; eight (9%) from community settings; 11 (12%) from specialist physical health settings; and two (2%) used a mixture of primary/community/specialist settings.

Participants

Participant characteristics: Seventy‐nine comparisons (88%) focused on adults aged 18 to 64 years; two (2%) on adolescents under the age of 18; and nine (10%) on those 65 years or more. For comparisons with available data (n = 70), 33 (47%) included a sample of predominately white origin (classed as 75% or more of the sample). Twenty‐one comparisons (23%) included only those who were taking medication for depression and/or anxiety at baseline.

Diagnosis: Eighty‐four comparisons (93%) included participants with symptoms of depression or depression and anxiety; six (7%) included only participants with anxiety disorders.

The diagnostic status of participants was identified in 45 comparisons (50%) using Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (APA 2000) or International Classification Disorder (ICD) (WHO 1992) criteria. In the remainder, depression or anxiety status at point of entry was defined by self‐rated or clinician‐rated validated instruments or by the primary care provider without the use of standardised measures or criteria. In three comparisons (3%) participants did not have to have symptoms of depression at baseline (Bartels 2004; Kroenke 2010; Williams 2007). As stated in the protocol, we included these studies since at least 50% of participants had depression at baseline, based on mean score of depression outcome measure or numbers provided.

Sixty‐five comparisons (72%) included participants with both subthreshold and diagnosed major depressive or anxiety disorder; 23 (26%) included only those that met diagnostic criteria for major depressive or anxiety disorder; and two (2%) included only subthreshold patients.

Sixteen comparisons (18%) had physical comorbidity as an inclusion criteria, such as, diabetes (Bogner 2010; Ell 2010; Katon 2004; Piette 2011), cancer (Dwight‐Johnson 2005; Ell 2008; Kroenke 2010; Strong 2008), epilepsy (Ciechanowski 2010), post‐stroke (Williams 2007), heart disease (Huffman 2011; Rollman 2009) or other/mix of conditions (Bogner 2008; Katon 2010; Pyne 2011; Vera 2010).

Setting: In 82 comparisons (91%) the main healthcare provider was based in primary care; in eight comparisons (9%) a specialist provided general medical care.

Interventions

All comparisons had to meet the four criteria of collaborative care stated in the protocol although there was considerable variability in the exact nature of the intervention.

A multi‐professional approach to patient care: all comparisons involved a primary care provider (generic medical professional) and at least one other health professional (e.g. psychiatrist, nurse, psychologist). In 78 comparisons (87%) the intervention involved contributions from people with three distinct roles (primary care provider, case manager, mental health specialist); 12 (13%) involved two professional roles (primary care provider and case manager, although in these comparisons typically the case manager was a mental health specialist). In 50 comparisons (56%) the case manager was a mental health practitioner; in 40 (44%) the case manager did not have a professional background in mental health.

A structured management plan: all comparisons included an organised approach to patient care (e.g. evidence based medication algorithm, manualised psychological interventions such as behavioural activation or cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)). In 48 comparisons (53%) the intervention included medication management and psychological therapy; 37 (41%) included medication management only; and 5 (6%) psychological therapy only.

Scheduled patient follow‐ups: all comparisons included an organised approach to patient follow‐up (e.g. scheduled telephone or in‐person follow‐up appointments). In 49 (54%) of the comparisons the intervention lasted six months or less, in 31 (34%) comparisons the intervention lasted more than six months, and it was unclear how long the intervention lasted in 10 (11%) comparisons.

Enhanced inter‐professional communication: all comparisons introduced mechanisms to facilitate communication between professionals (e.g. team meetings, individual consultation/supervision, shared medical records, and patient‐specific written or verbal feedback between care‐givers).

The duration of the intervention varied across studies and data extraction was complex. Detailed data were not always reported, and the intensity of collaborative care interventions is sometimes contingent on short‐term outcomes rather than being standardised for all patients, and may be titrated over time so that an initial high intensity intervention is replaced by low intensity monitoring over the longer‐term. We estimated that 32 comparisons (36%) included an intervention of more than six months duration.

We will explore variability between studies in meta‐regression analyses and include this in the updated review.

Comparison group

Thirty‐four (38%) comparisons provided no additional intervention in the usual care group. Fifty‐two (58%) comparisons did provide additional interventions in the usual care group (such as education (guidelines or brief training session) for primary care providers on the recognition and management of depression, or notification of patient’s depression status) but these aspects of the intervention were also applied in the intervention arm. One (1%) comparison enhanced usual care by providing an intervention that the collaborative care arm did not receive (Asarnow 2005). One (1%) comparison did not describe usual care (Uebelacker 2011).

Excluded studies

Of the 3473 records screened, we excluded 2855 (82%) on title and abstract. We retrieved 618 full‐text articles and excluded 183 (30%) from the review. Of these, 27 did not meet study design criteria (e.g. not RCTs), 97 did not meet intervention criteria (e.g. the intervention was not focused on the depression or anxiety, only included one professional, did not include enhanced communication or scheduled follow‐ups), 18 did not meet diagnostic criteria (e.g. less than 50% of participants were depressed or anxious at baseline), and 41 were companion papers of the excluded ones.

The ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’ table lists those trials which were potentially relevant (n = 37) but which did not meet all the inclusion criteria for the review, together with the exact criteria on which they were excluded. We excluded 24 because of the type of intervention used, 11 because of the types of participants included, and two because of study design.

Ongoing studies

Twenty studies are classified as 'ongoing' (Characteristics of ongoing studies). We contacted all lead authors of these studies, and whilst some studies were complete, data were not published/available in time to include in the review.

Studies waiting classification

Eight studies are awaiting classification because we either have not been able to contact authors/are awaiting author response, the study is completed and we are awaiting publication of results, or translation was not possible within the time frame of the review (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

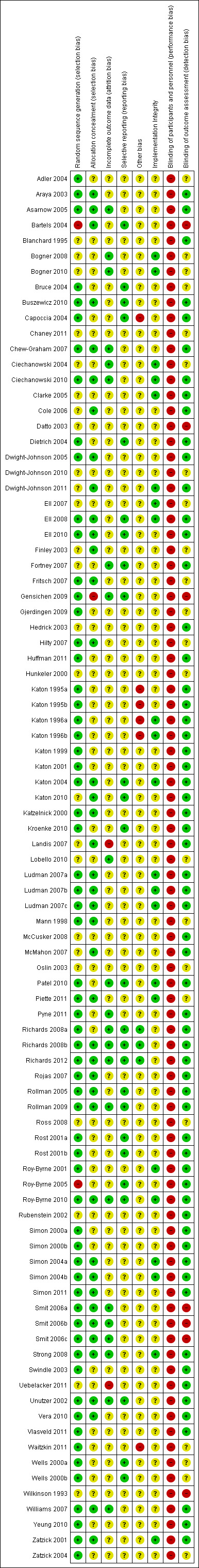

Risk of bias in included studies

A graphical representation of the risk of bias in included studies is presented in Figure 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Generation of random sequence

In sixty‐three (70%) comparisons random sequence generation was described adequately and we rated these as ‘low risk' of bias. In twenty‐five (28%) comparisons the description of how the sequence was generated was either missing or there was insufficient information available to make an assessment and we rated these as ‘unclear risk' of bias. Two (2%) comparisons described methods which were considered to be at ‘high risk' of bias (Bartels 2004; Roy‐Byrne 2005).

Allocation

In forty (44%) comparisons there was adequate description of allocation concealment and we rated these as ‘low risk' of bias. In forty‐nine (54%) comparisons the description of allocation concealment was either missing or there was insufficient information available for assessment and we rated these as ‘unclear risk' of bias. One (1%) comparison described methods which were considered to be at ‘high risk' of bias (Gensichen 2009).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel was not possible in any case. We therefore rated all comparisons at ‘high risk' of bias in relation to this criterion.

Sixty‐one (68%) comparisons described adequate blinding of those completing outcome assessment and we rated these at ‘low risk' of bias. In twenty‐two (24%) comparisons the description of blinding of outcome assessment was either missing or there was insufficient information available for assessment and we rated these as ‘unclear risk' of bias. Seven (8%) comparisons described methods which we considered to be at ‘high risk' of bias (Bartels 2004; Datto 2003; Gensichen 2009; Smit 2006a; Smit 2006b; Smit 2006c; Wilkinson 1993).

Incomplete outcome data

In terms of the proportion of randomised patients who were lost to follow‐up at the 0 to 6 month follow‐up, for the 87 comparisons where rates could be calculated, 26 (30%) had 10% or less loss to follow‐up, 38 (44%) had 11% to 20%, 14 (16%) had 21% to 30%, 6 (7%) had 31% to 40%, and 3 (3%) had 40% or more loss to follow‐up.

In terms of differences in the proportions between collaborative care and usual care arms, seven (8%) comparisons had differences of greater than 10% between trial arms.

Twenty‐three (26%) comparisons did not have high rates of loss to follow‐up or imbalance and described adequate methods of dealing with incomplete outcome data and we rated these as ‘low risk' of bias. In sixty‐six (73%) comparisons the rates of loss to follow‐up or imbalance were high, the description of methods for dealing with incomplete outcome data was missing, or there was insufficient information available for assessment, and we rated these as ‘unclear risk' of bias. One (1%) comparison had high rates of loss to follow‐up and described methods of dealing with missing data which were considered to be at ‘high risk' of bias (Uebelacker 2011).

Selective reporting

In twenty‐five comparisons (28%) the authors had made protocols available and reported on all expected outcomes, therefore we rated these as ‘low risk' of bias. Sixty‐five comparisons (72%) did not have a protocol available and/or insufficient information was available to judge selective reporting, and we rated these as ‘unclear risk' of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Using the three criteria to assess other potential sources of bias: 1) any potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; 2) study claimed to have been fraudulent; or 3) some other problem, we rated 81 comparisons (90%) as 'unclear risk' of bias, three (3%) as 'low risk' of bias and six (7%) as 'high risk' of bias. We made the high risk of bias judgements based on analytical methods used or cross‐contamination, where case managers were specified to provide care for patients in both usual care and collaborative care groups.

Effects of interventions

1. Collaborative care versus usual care (adults)

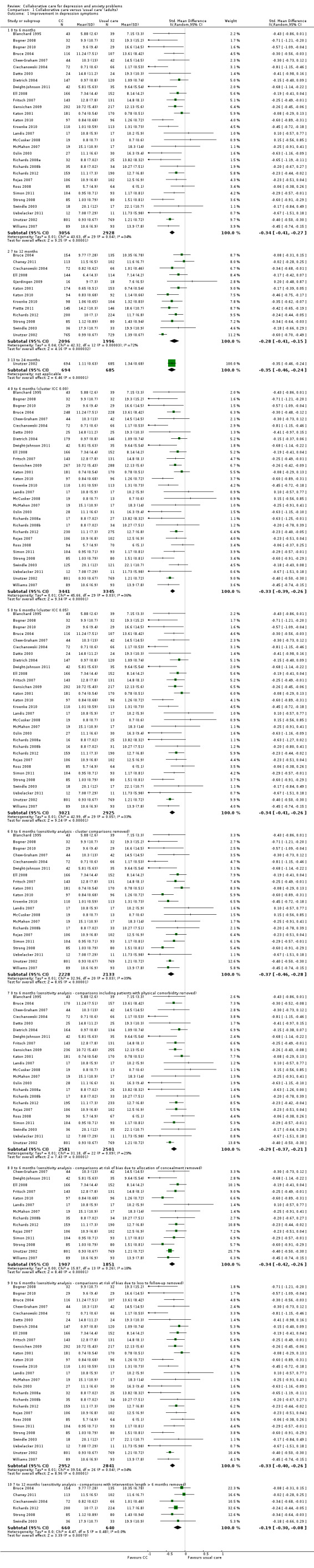

1.1 and 1.2 Depression

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

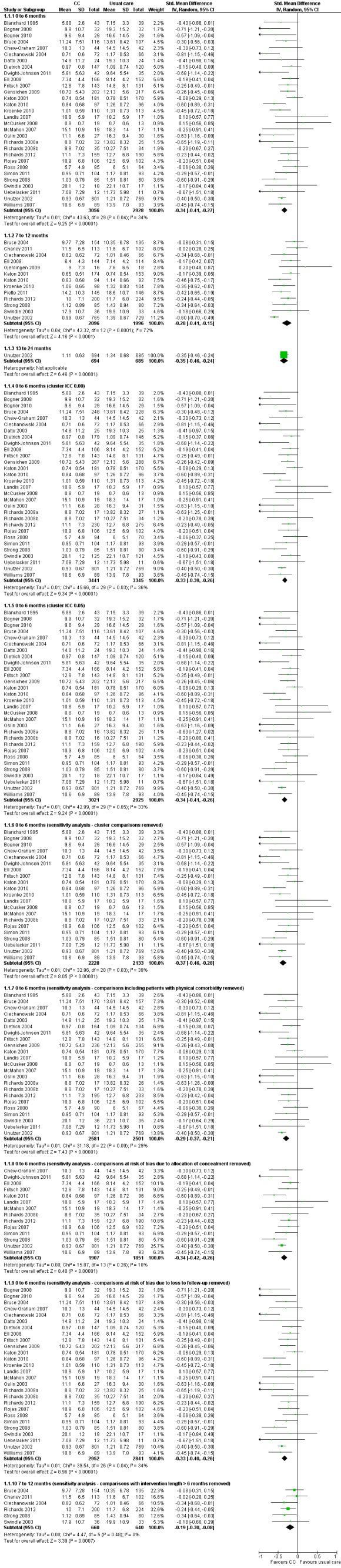

Thirty comparisons (5984 participants) reported short‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (standard mean difference (SMD) ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.27, I² = 34%) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 1 Improvement in depression symptoms.

Forty‐eight comparisons (11,250 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (risk ratio (RR) 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43, I² = 71%) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 2 Depression response.

The funnel plots for the analyses of short‐term continuous and dichotomous outcomes are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Neither showed marked evidence of asymmetry.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), outcome: 1.1 Improvement in depression symptoms.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), outcome: 1.2 Depression response.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Thirteen comparisons (4092 participants) reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.15, I² = 72%) (Analysis 1.1).

Twenty‐nine comparisons (8001 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48, I² = 83%) (Analysis 1.2).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

One comparison (1379 participants) reported long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.24, I² not applicable) (Analysis 1.1).

Six comparisons (2983 participants) reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.41, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.2).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care.

Five comparisons (943 participants) reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.27, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.2).

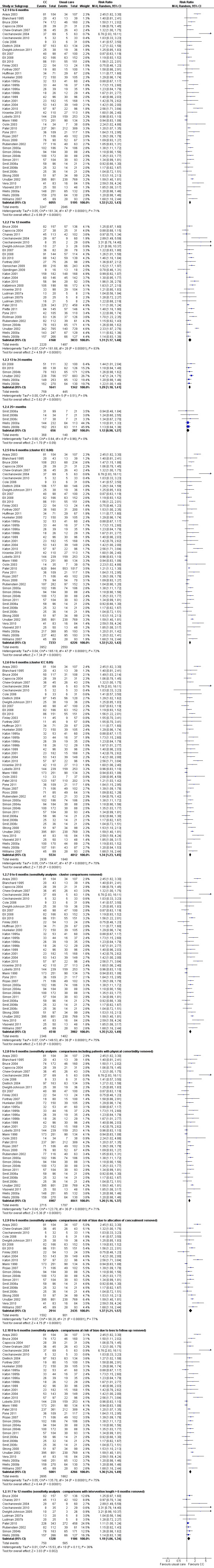

1.3 Antidepressant medication use

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

Forty‐four comparison studies (10,117 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.63, I² = 81%) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 3 Antidepressant medication use.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Twenty‐six comparisons (6486 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.26 to 1.61, I² = 78%) (Analysis 1.3).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

Six comparisons (2963 participants) reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.45, I² = 54%) (Analysis 1.3).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

Three comparisons (232 participants) reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.21, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.3).

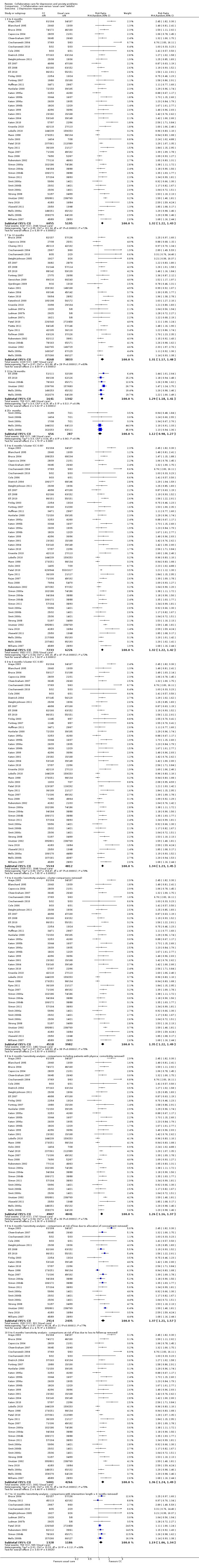

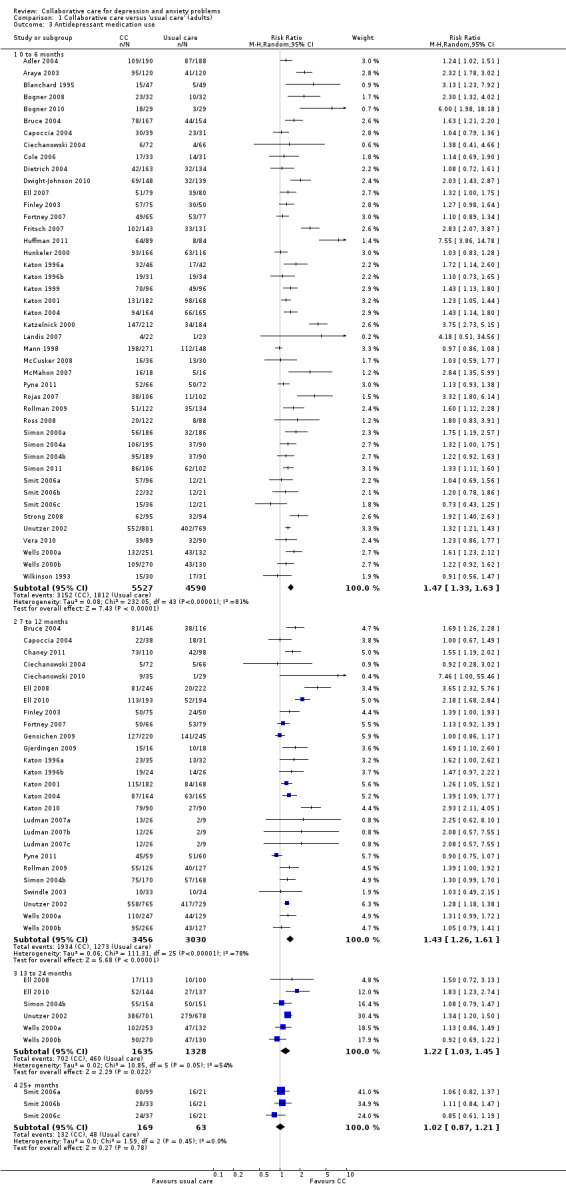

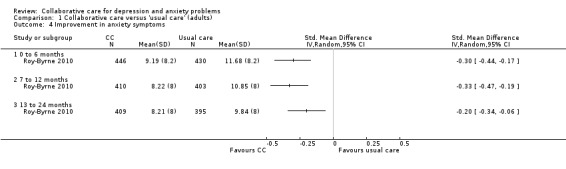

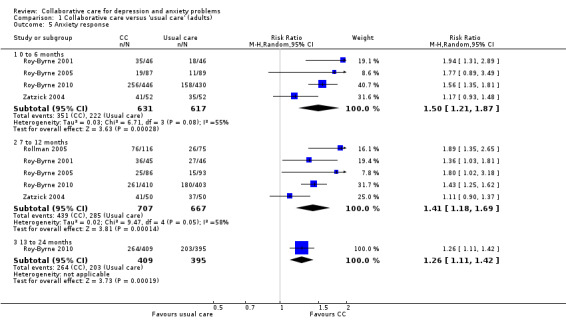

1.4 and 1.5 Anxiety

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

One comparison (876 participants) reported short‐term continuous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.17, I² not applicable) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 4 Improvement in anxiety symptoms.

Four comparisons (1248 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.87, I² = 55%) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 5 Anxiety response.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

One comparison (813 participants) reported medium‐ term continuous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.19, I² not applicable) (Analysis 1.4).

Five comparisons (1374 participants) reported medium‐ term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.69, I² = 58%) (Analysis 1.5).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

One comparison (804 participants) reported long‐term continuous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.34 to ‐0.06, I² not applicable) (Analysis 1.4).

One comparison (804 participants) reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.42, I² not applicable) (Analysis 1.5).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous or dichotomous outcomes for anxiety for collaborative care versus usual care.

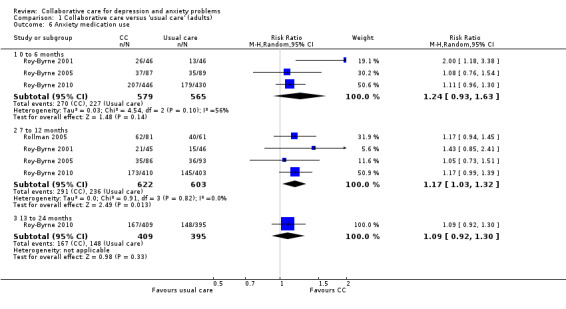

1.6 Anxiety medication use

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

Three comparisons (1144 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety medication use. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.63, I² = 56%) (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 6 Anxiety medication use.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Four comparisons (1225 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety medication use. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.32, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.6).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

One comparison (804 participants) reported longer‐term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety medication use. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.30, I² not applicable) (Analysis 1.6).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for anxiety medication use.

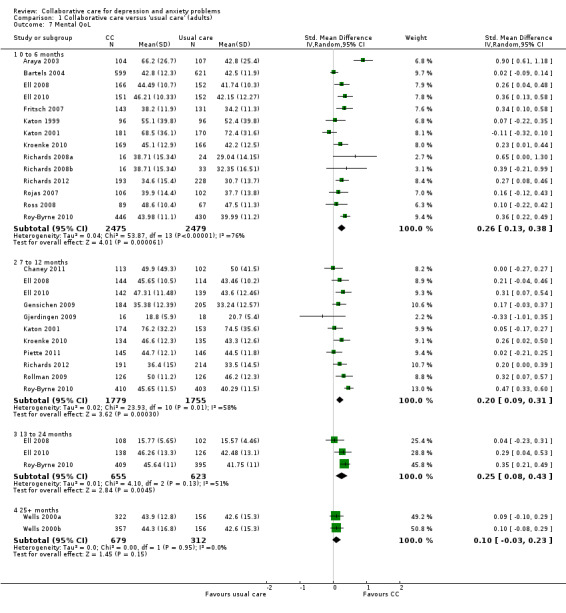

1.7 Mental health quality of life

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

Fourteen comparisons (4954 participants) reported short‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD 0.26, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.38, I² = 76%) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 7 Mental QoL.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Eleven comparisons (3534 participants) reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD 0.20, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.31, I² = 58%) (Analysis 1.7).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

Three comparisons (1278 participants) reported long‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD 0.25, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.43, I² = 51%) (Analysis 1.7).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

Two comparisons (991 participants) reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.23, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.7).

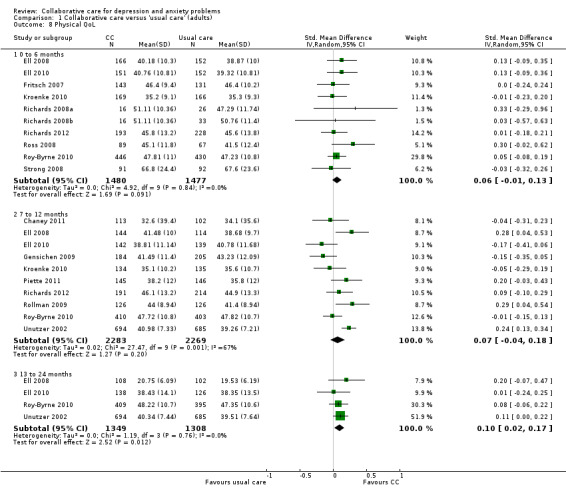

1.8 Physical health quality of life

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

Ten comparisons (2957 participants) reported short‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.13, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 8 Physical QoL.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Ten comparisons (4552 participants) reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.18, I² = 67%) (Analysis 1.8).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

Four comparisons (2657 participants) reported long‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD 0.10, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.17, I² = 0%) (Analysis 1.8).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life.

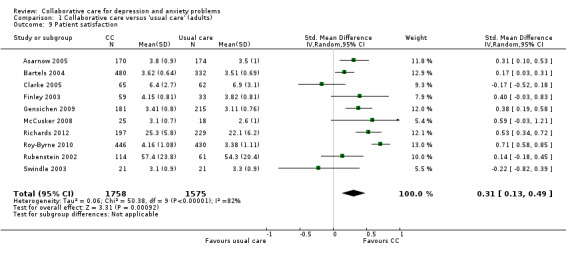

1.9 and 1.10 Patient satisfaction

Ten comparisons (3333 participants) reported continuous outcomes for patient satisfaction. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (SMD 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.49, I² = 82%) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 9 Patient satisfaction.

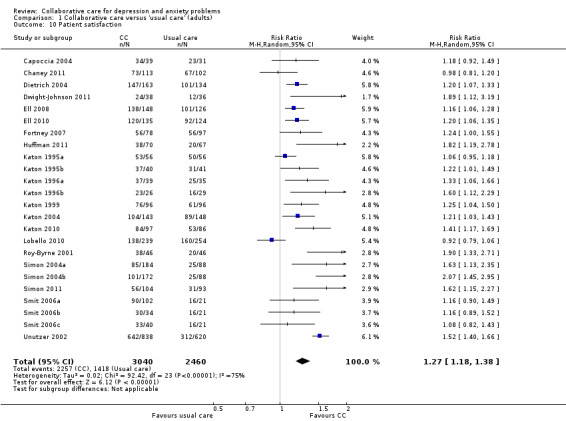

Twenty‐four comparisons (5500 participants) reported dichotomous outcomes for patient satisfaction. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.38, I² = 75%) (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adults), Outcome 10 Patient satisfaction.

2. Collaborative care versus usual care (adolescents)

2.1 and 2.2 Depression

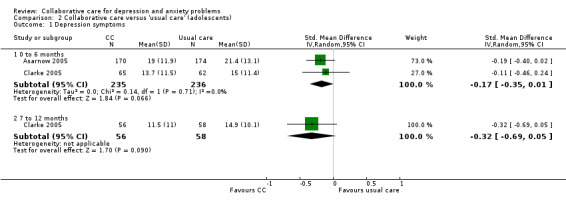

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

Two comparisons (471 participants) reported short‐term continuous depression outcomes for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.35 to 0.01, I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adolescents), Outcome 1 Depression symptoms.

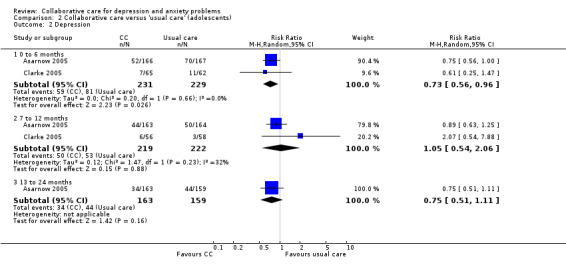

Two comparisons (460 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.96, I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adolescents), Outcome 2 Depression.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

One comparison (114 participants) reported medium‐term continuous depression outcomes for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents. There were no significant differences between the two (SMD ‐0.32, 95% CI ‐0.69 to 0.05, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.1).

Two comparisons (441 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.06, I² = 32%) (Analysis 2.2).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents.

One comparison (322 participants) reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.11, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.2).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous or dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus usual care in adolescents.

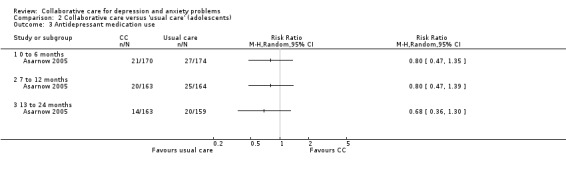

2.3 Antidepressant medication use

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

One comparison (335 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.35, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adolescents), Outcome 3 Antidepressant medication use.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

One comparison (327 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.39, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.3).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

One comparison (321 participants) reported longer‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.30, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.3).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for antidepressant medication use.

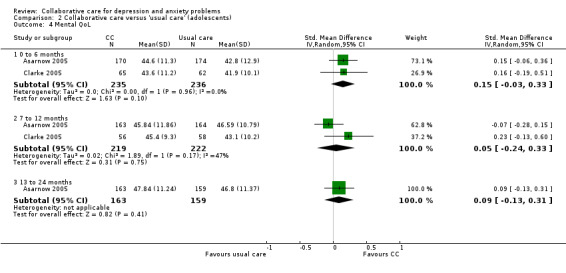

2.4 Mental health quality of life

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

Two comparisons (471 participants) reported short‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.33, I² = 0%) (Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adolescents), Outcome 4 Mental QoL.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Two comparisons (441 participants) reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.33, I² = 47%) (Analysis 2.4).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

One comparison (322 participants) reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.31, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.4).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for mental health quality of life.

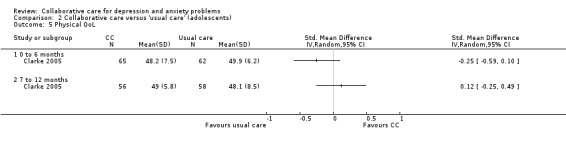

2.5 Physical health quality of life

Short‐term 0 to 6 months

One comparison (127 participants) reported short‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.10, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adolescents), Outcome 5 Physical QoL.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

Two comparisons (114 participants) reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.12, 95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.49, I² not applicable) (Analysis 2.5).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life.

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for physical health quality of life.

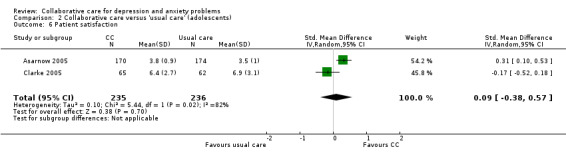

2.6 Patient satisfaction

Two comparisons (471 participants) reported continuous outcomes for patient satisfaction. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.57, I² = 82%) (Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Collaborative care versus 'usual care' (adolescents), Outcome 6 Patient satisfaction.

No comparisons reported dichotomous outcomes for patient satisfaction.

3. Collaborative care versus feedback (adults)

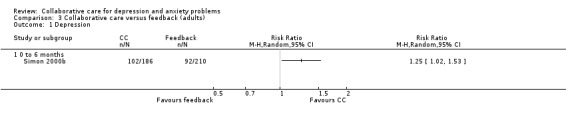

3.1 Depression

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

No comparisons reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

One comparison (396 participants) reported dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback. Collaborative care was significantly more effective than feedback (RR 1.25, 95% C I 1.02 to 1.53, I² not applicable) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Collaborative care versus feedback (adults), Outcome 1 Depression.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

No comparisons reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

No comparisons reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

No comparisons reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

No comparisons reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus feedback.

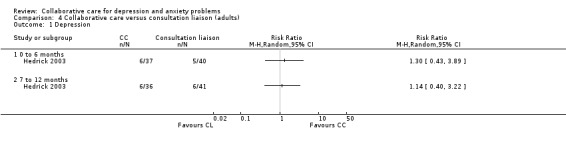

4. Collaborative care versus consultation‐liaison (adults)

4.1 Depression

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

No comparisons reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus consultation‐liaison.

One comparison (77 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus consultation‐liaison. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.43 to 3.89, I² not applicable) (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Collaborative care versus consultation liaison (adults), Outcome 1 Depression.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

One comparison (77 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus consultation‐liaison. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.40 to 3.22, I² not applicable) (Analysis 4.1).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term continuous or dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus consultation‐liaison.

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous or dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus consultation‐liaison.

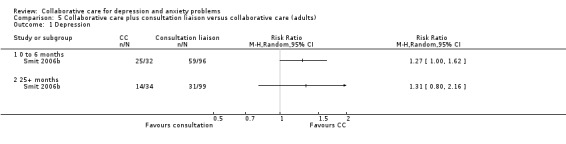

5. Collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison versus collaborative care (adults)

5.1 Depression

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

One comparison (128 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison versus collaborative care. Collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison was significantly more effective than usual care (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.62, I² not applicable) (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Collaborative care plus consultation liaison versus collaborative care (adults), Outcome 1 Depression.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

No comparisons reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison versus collaborative care.

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison versus collaborative care.

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

One comparison (133 participants) reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus consultation‐liaison versus collaborative care. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.16, I² not applicable) (Analysis 5.1).

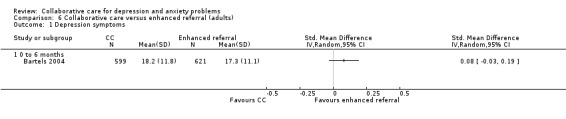

6. Collaborative care versus enhanced referral (adults)

6.1 Depression

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

One comparison (1220 participants) reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus enhanced referral. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.19, I² not applicable) (Analysis 6.1).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Collaborative care versus enhanced referral (adults), Outcome 1 Depression symptoms.

No studies reported dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus enhanced referral.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

No comparisons reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus enhanced referral.

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus enhanced referral.

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care versus enhanced referral.

7. Collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication) (adults)

7.1 Depression

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

No comparisons reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication).

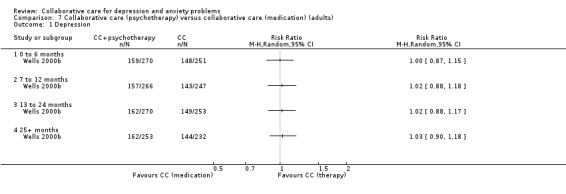

One comparison (521 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication). There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.15, I² not applicable) (Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication) (adults), Outcome 1 Depression.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

No comparisons reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative‐care (medication).

One comparison (513 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication). There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.18, I² not applicable) (Analysis 7.1).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication).

One comparison (523 participants) reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication). There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.17, I² not applicable) (Analysis 7.1).

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication).

One comparison (485 participants) reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care (psychotherapy) versus collaborative care (medication). There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.18, I² not applicable) (Analysis 7.1).

8. Collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care (adults)

8.1 and 8.2 Depression

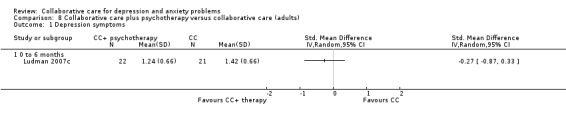

Short‐term: 0 to 6 months

One comparison (43 participants) reported continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care. There were no significant differences between the two groups (SMD ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.87 to 0.33, I² not applicable) (Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care (adults), Outcome 1 Depression symptoms.

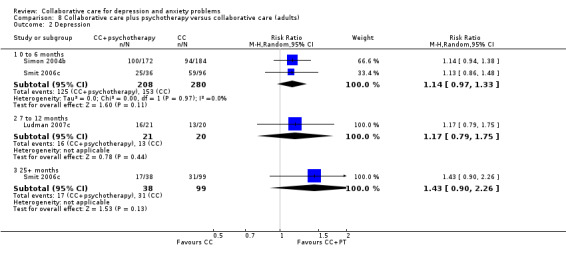

Two comparisons (488 participants) reported short‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.33, I² = 0%) (Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care (adults), Outcome 2 Depression.

Medium‐term: 7 to 12 months

No comparisons reported medium‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care.

One comparison (41 participants) reported medium‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.75, I² not applicable) (Analysis 8.2).

Long‐term: 13 to 24 months

No comparisons reported long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care.

No comparisons reported long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care.

Very long‐term: 25 months or more

No comparisons reported very long‐term continuous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care.

One comparison (137 participants) reported very long‐term dichotomous outcomes for depression for collaborative care plus psychotherapy versus collaborative care. There were no significant differences between the two groups (RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.90 to 2.26, I² not applicable) (Analysis 8.2).

Sensitivity analyses

The main analysis of the effects of collaborative care on continuous depression outcomes at six months (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.27) was not markedly changed when the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) used to analyse cluster comparisons was 0.00 (SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.26) or 0.05 (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.26) (Analysis 1.1).

The main analysis of the effects of collaborative care on continuous depression outcomes at six months (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.27) was not markedly changed when sensitivity analysis removed cluster comparisons (SMD ‐0.37, 95% CI ‐0.46 to ‐0.28), comparisons with inclusion criteria of physical comorbidity (SMD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.21) or comparisons at unclear or high risk of bias in terms of allocation concealment (SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.26) or loss to follow‐up (SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.40 to ‐0.26) (Analysis 1.1).

The effects of collaborative care on continuous depression outcomes at 12 months (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.15) changed to SMD ‐0.19 (95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.08) when comparisons including intervention beyond six months were removed.

The main analysis of the effects of collaborative care on dichotomous depression outcomes at six months (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43) was not markedly changed when the estimates of the ICC used to analyse cluster comparisons were 0.00 (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.42) or 0.05 (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.45) (Analysis 1.2).

The main analysis of the effects of collaborative care on dichotomous depression outcomes at six months (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.43) was not markedly changed when sensitivity analysis removed cluster comparisons (RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.49), comparisons with inclusion criteria of physical comorbidity (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.37) and comparisons at unclear or high risk of bias in allocation concealment (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.57) or loss to follow‐up (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.49) (Analysis 1.2).

The effects of collaborative care at 12 months (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.48) changed to RR 1.19 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.34) when comparisons including intervention beyond six months were removed.

Discussion