Abstract

Background:

Perceptions of health harms and addictiveness related to nicotine products, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients are an important predictor of use. This study examined differences in perceived harm and addiction across such products among adolescents, young adults, and adults.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional survey (N = 6,131, ages 13–40 years old) in which participants reported perceived harm and addictiveness for 11 products (cigarettes, disposable nicotine e-cigarettes, pod-based nicotine e-cigarettes, other nicotine e-cigarettes, THC e-cigarettes, e-cigarettes with other ingredients, nicotine pouches, nicotine lozenges, nicotine gums, nicotine tablets, nicotine toothpicks). We applied adjusted regression models and conducted pairwise comparisons between age group (13–17, 18–20, 21–25, and 26–40) and product use status (never, ever, and past-30-day use), adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and financial comfort.

Results:

Overall, participants in younger age groups perceived products to be more harmful and addictive than those in older age groups, with the exception of e-cigarettes with other ingredients. For all products, participants who never used perceived each product to be more harmful than those who ever used. For all products, participants who used the products in the past 30-days had lower perceived harm and addictiveness compared to never and ever use. Certain sociodemographic groups, such as people who identify as LGBTQ+, Non-Hispanic Black, or Hispanic, had lower perceived harm and addictiveness for most products.

Discussion:

Efforts should be made to educate all age groups and minoritized groups on harms and addictiveness of all nicotine products, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients.

Keywords: Nicotine, cannabis, e-cigarettes, perceptions, addiction

Introduction

E-cigarette use is high in the U.S. across all age groups, exposing millions of people to harmful toxins and chemicals including nicotine. In 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 14% of adolescents (grades 6–12), 11% of young adults (age 18–24), and 7% of adults (age 24 and older) used a nicotine e-cigarette in the past 30-days.1,2 Adolescent use of nicotine e-cigarettes has recently decreased, yet in 2023, 10% of high-school students reported past 30-day use.3 Of increasing concern is the rising popularity and prevalence of using other substances in e-cigarettes,4 including tetrahydrocannabidiol (THC; the active ingredient in cannabis), melatonin, caffeine, and vitamins.4,5 Use of other oral nicotine products, such as nicotine pouches and gums, is also becoming increasingly popular, especially among adolescents and young adults.6,7 For example, the 2023 National Youth Tobacco Survey found that over 410,000 U.S. adolescents reported nicotine pouch use in the past 30-days,3 which is an increase from 2022.8

The health risks associated with nicotine (including plant-based and synthetic nicotine) and THC use include respiratory distress, addiction, difficulty quitting both substances, impacts on mental health, and psychosocial problems.9–12 Both nicotine and THC are harmful to and disrupt the developing adolescent brain;13,14 as such, adolescents and young adults are highly susceptible to addiction when using these substances in any form.15 People continue to use these products in large part because they are addicted, and many of those who report a desire to quit struggle to do so.16 To help address this public health issue and protect people from such health risks and addiction, it is necessary to understand beliefs that drive decisions to use e-cigarettes that contain nicotine, THC, and other ingredients as well as other nicotine products.

Although the health risks and addictive potential of nicotine products have been well documented, people tend to misperceive harm,17–19 people tend to misperceive harm, particularly for newer nicotine products such as nicotine pouches.7 Risk perceptions are one of the many determining factors of behavior, with both theory (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior, Health Belief Model),20 and research21 showing a significant and important relationship between perceived risks, intentions or willingness to use, and actual substance use behavior. For example, the theory of planned behavior posits that individual behavior results from intentions, which are influenced by attitudes and perceptions.22 Thus, the perceptions people have of the potential harm and addictiveness of substances may influence their willingness and future plans to use those substances. Across methodologies and samples of adolescents, young adults, and adults, people who perceive low risk and/or harbor greater misperceptions of substance-related harm and addiction are more likely to initiate and use substances.19,23,24 Lower perceived risk of substances not only contribute to initiation of use,25 but also lowered intention to quit or reduce use.26 Research on individual-level characteristics have found that those who are more socioeconomically disadvantaged or minoritized tend to have lower risk perceptions of nicotine products compared to those who do not identify as a socioeconomic minority.24 Studies on people who identify as a sexual and/or gender minority have found mixed results on harm perceptions of nicotine products.27,28

Despite the existing research around harm perceptions and substance use, few studies have compared risk perceptions for an array of nicotine products, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients across age groups that include adolescents to adults. Qualitative research has found that adolescents and young adults perceive the harms of tobacco and cannabis products differently,29,30 but we lack quantitative studies. Moreover, few studies include different types of substances and products within a single analysis to provide comparisons across products, and none include different types of e-cigarettes (e.g., disposable vs. pod-based vs. non-nicotine including THC and other ingredients) or other nicotine products such as Zyn/oral nicotine pouches.7 Assessment of harm perceptions is vital for understanding who may be at highest risk for initiation and use.

This study will examine perceptions of harm and addictiveness across a variety of nicotine products, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients. The sample includes adolescents, young adults, and adults. The study’s objectives are to: 1) examine whether perceptions of harm and addictiveness vary across products and product use status; and 2) examine whether perceptions of harm and addictiveness of different products vary across age groups and sociodemographic factors (e.g., race/ethnicity and sexual identity). Based on prior studies on e-cigarette perceptions,18,31 we hypothesize that participants in younger age groups and those who have never used the product will perceive greater harm and addictiveness. Understanding harm perceptions across various products and across all age groups and use experiences will be key to understanding how to tailor prevention strategies to help lower population-level and sub-population-level risk perceptions and ultimately use of specific products.

Methods

Procedures

We conducted a national cross-sectional survey study from November to December 2021 via Qualtrics and utilizing their online research panel. Qualtrics is an online survey tool that also provides access to an online panel of research participants to partake in research surveys.32 Participants in these online panels are chosen from a pre-determined pool of participants who have agreed to be contacted by market research organizations to complete surveys.33 Potential participants were recruited by Qualtrics and provided online consent (18 years and older) or assent (younger than 18 years) before taking part in the online survey. All study protocols were approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board. To maintain data quality, the study followed American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guidelines for reporting the study sample, survey completion rate, and procedures. For more information on the study, please see descriptions of methods published elsewhere.4

Sample

The sampling plan was to recruit a 1:1:1 ratio of participants in the following age groups (13 to 17 years, 18 to 20 years, and 21 to 40 years) and to have the sample approximate the US Census for sex, race, and ethnicity. Once the demographic quotas were met, additional participants from that subgroup would not be recruited into the survey. The average survey completion time for participants was 28 minutes; participants could only complete the survey one time. Participants who completed the survey under the median completion time or failed our attention checks were excluded.

The final survey sample included N=6,131 participants, and over-half identified as female (n=3451, 56.3%), non-Hispanic white (n=3188, 52%), and heterosexual (n=4261, 69.5%). Although the sampling plan recruited a 1:1:1 ratio of participants in the following age groups (13 to 17 years, 18 to 20 years, and 21 to 40 years), to address the questions in this study we recoded age into a four-category variable of: ages 13–17 (adolescent), 18–20 (young adult under 21, the legal purchase age for tobacco and cannabis), 21–25 (young adult but over 21), and 26–40 (adult, age when brain development more finalized and less likely to become addicted).13,14 Resultant age categories included 26.6% (n=1631) adolescents, 33.2% (n=2036) young adults under 21, 20.1% (n=1232) young adults over 21, and 20.1% (n=1232) adults.

Measures

Development of the survey instrument was pilot tested with a group of 42 adolescents, young adults, and adults.

Demographics

Participants self-reported their age, gender identity (male, female, nonbinary or other, and prefer not to say), sexual orientation (heterosexual or straight, LGBTQ+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, queer, intersex, pansexual, two-spirit (2S), androgynous, or asexual], not listed above [please specify], and prefer not to say), race and ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino; non-Hispanic Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander; non-Hispanic Black or African American; non-Hispanic White; non-Hispanic other or multiracial; and prefer not to say), and financial comfort (do not meet basic expenses, just meet expenses with nothing left over, meet needs with a little left over, live comfortably, and prefer not to say).34

Product Use

Consistent with survey best practices,35 all participants first viewed a description of each product, including different terms used to refer to these products, example brand names, and accompanying photographs (see Supplemental Table 1). We then asked all participants, “Have you ever used any of these products in your entire life? (Please select Yes or No)” corresponding to the following 11 products: “(1) Cigarettes, even 1 or 2 puffs; (2) Non-nicotine e-cigarettes like Monq or Vitaminvape, even 1 or 2 puffs; (3) Disposable pod-based vape like Puffbar or FOGG, even 1 or 2 puffs; (4) Pod-based vape like JUUL or Phix, even 1 or 2 puffs; (5) Any other vape like mods, even 1 or 2 puffs; (6) Vaped THC (wax or oil) or marijuana, even 1 or 2 puffs; (7) Nicotine pouch like Zyn or Velo, even for a short time; (8) Nicotine lozenge like Lucy or Velo, even for a short time; (9) Nicotine gum like Lucy or Nicorette, used even once; (10) Nicotine tablet like Rouge, even swallowed once; and (11) Nicotine toothpick like Pixotine or Zippix, used even once.” For any product ever used, we then asked participants to indicate past 30-day use (0–30 days). We then recoded participants to having never used, ever used (but not in the past 30-days), and used in the past 30-days.

Perceived Harm of Each Product

For each of the products, we asked participants: “How HARMFUL would this [product] be for YOUR HEALTH?” with the possible answer options of “Not at all harmful” (score of 1), “Slight harmful” (2), “Moderately harmful” (3), and “Extremely harmful” (4).36 Perceived harm of nicotine lozenge and tablet were asked together.

Perceived Addictiveness of Each Product

For each of the products, we asked participants: “How addictive are these products?” with the possible answer options of “Not addictive” (score of 1), “Slightly addictive” (2), “Moderately addictive” (3), “Extremely addictive” (4).36

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to ascertain perceptions of harm and addictiveness for each product overall, across age groups (13–17 years, 18–20 years, 21–25 years, and 26–40 years), and by product use status (never, ever, and past 30-day use). Chi-squared tests were conducted to test for significant differences across age group and product use status for the perceptions of harm and addictiveness for each of the products. We then applied adjusted linear regression models, including covariates for age group, product use status, gender, race/ethnicity, and financial comfort, for the perceived harm and addictiveness for each product. Post-hoc tests were conducted for pairwise comparisons, adjusting the alpha using the Tukey test, between the age group and product use status categories. Statistical analyses were conducted in R software [version 1.1.456, R Core Team]. All tests were 2-tailed, with significance set at P < .05.

Results

Perceived Harm of Each Product, Overall and by Demographic Characteristics

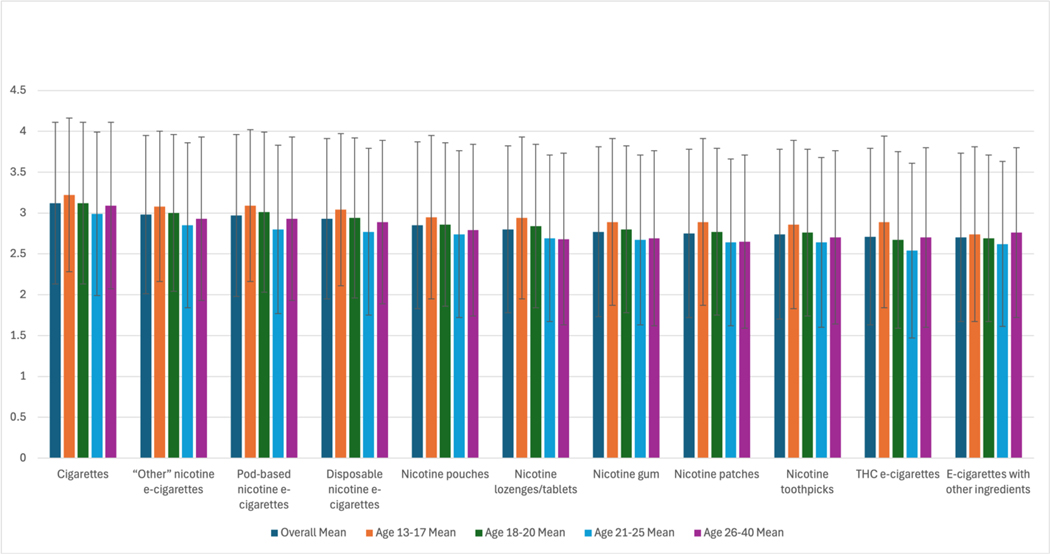

Across all products assessed, between 8% to 16.9% of participants perceived that these products were not at all harmful to their health (Supplemental Table 2). Participants found cigarettes to be the most harmful (M: 3.12, SD: 0.99), followed by “any other vape like mods” (“other” nicotine e-cigarettes) (M: 2.98, SD: 0.97) and pod-based nicotine e-cigarettes (M: 2.97, SD: 0.99) (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 3). THC e-cigarettes (M: 2.71, SD: 1.08) and non-nicotine e-cigarettes like Monq or Vitaminvape (e-cigarettes with other ingredients) (M: 2.70, SD: 1.03) were perceived as the least harmful.

Figure 1:

Perceived Harm of Each Product (Mean and Standard Deviation), Overall and by Age Group

Participants aged 13–17 perceived each product to be more harmful than those aged 21–25 (p’s <0.01), with the exception of “other” nicotine e-cigarettes and nicotine toothpicks (no difference in perceived harm). Participants aged 18–20 perceived nicotine e-cigarettes to be more harmful than did those aged 21–25 (p’s <0.05). However, there was no difference in perceived harm of e-cigarettes with other ingredients for participants for all age groups. Participants aged 18–20 perceived e-cigarettes with other ingredients to be less harmful than those aged 26–40 (p’s <0.008). See Supplemental Table 3 for full details on post-hoc pairwise comparisons of perceived harm and age group for each product.

Participants who identified as Non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic had lower perceived harm (compared to Non-Hispanic White) for cigarettes and nicotine e-cigarettes (p’s <0.001). Participants who identified as Asian American/Pacific Islander perceived greater harm (compared to Non-Hispanic White) for THC e-cigarettes, nicotine pouches, nicotine lozenges/tablets, and nicotine toothpicks (p’s <0.028) and lower harm for cigarettes and disposable nicotine e-cigarettes (p’s <0.048). There were no differences in perceptions of harm among participants who identified as LGBTQ+ (compared to heterosexual) for the nicotine e-cigarettes, yet perceived harm was lower across other products compared to their heterosexual identifying peers (p’s <0.011), with the exception of perceived harm being higher for cigarettes among participants who identified as LGBTQ+ (p=0.007). Similarly, for those who self-reported living less than comfortably (compared to living comfortably), there were no differences in perceptions of harm for the nicotine e-cigarettes, yet perceived harm was lower for e-cigarettes with other ingredients, THC e-cigarettes, nicotine gum, nicotine lozenges/tablets, and nicotine toothpicks (p’s < 0.03), and higher for cigarettes (p=0.002). See Table 1 for full adjusted regression results.

Table 1:

Perceived Harm of Each Product, by Sociodemographic Variable

| Cigarettes | E-cigarettes with other ingredients | Disposable nicotine e-cigarettes | Pod-based nicotine e-cigarettes | “Other” nicotine e-cigarettes | THC e-cigarettes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | |

| Age 13–17 (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age 18–20 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.128 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.980 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.245 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.481 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.601 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.009 |

| Age 21–25 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.002 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.844 | −0.19 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.001 | −0.17 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Age 26+ | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.983 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.019 | −0.12 | 0.04 | 0.002 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.017 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.081 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.188 |

| Use – Never (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Use - Ever | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.010 | −0.39 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.24 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.21 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.60 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Use - Past 30 days | −0.38 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.47 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.43 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.48 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.47 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.67 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Gender – Female (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gender - Male | −0.10 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.506 | −0.14 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.11 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.11 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| Gender- Non-Binary | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.065 | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.002 | −0.27 | 0.07 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.001 | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.001 | −0.31 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic Black | −0.24 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.162 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.091 |

| Race/ethnicity – Asian American/ Pacific Islander | −0.16 | 0.06 | 0.008 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.281 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.048 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.171 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.216 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.010 |

| Race/ethnicity – Hispanic | −0.28 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.909 | −0.16 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.512 |

| Race/ethnicity – Other/ Multiple | −0.26 | 0.07 | <0.001 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.247 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.229 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.310 | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.265 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.321 |

| Sexual identity – Heterosexual (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity –LGBTQ+ | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.007 | −0.14 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.682 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.124 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.954 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.011 |

| Income – Live comfortably (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Income – Live less than comfortably | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.002 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.535 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.523 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.955 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.003 |

| Nicotine pouches | Nicotine gum | Nicotine lozenges/tablets | Nicotine patches | Nicotine toothpicks | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | |

| Age 13–17 (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Age 18–20 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.165 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.100 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.090 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.003 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.014 |

| Age 21–25 | −0.15 | 0.05 | 0.001 | −0.17 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.21 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.05 | 0.001 |

| Age 26+ | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.108 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.025 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.001 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| Use – Never (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Use - Ever | −0.24 | 0.06 | <0.001 | −0.44 | 0.06 | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.07 | 0.004 | −0.32 | 0.06 | <0.001 | −0.24 | 0.09 | 0.010 |

| Use - Past 30 days | −0.47 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.39 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.38 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.32 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.35 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Gender – Female (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Gender - Male | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.061 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.004 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.050 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.144 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.046 |

| Gender- Non-Binary | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.061 | −0.16 | 0.07 | 0.029 | −0.18 | 0.07 | 0.014 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.142 | −0.19 | 0.07 | 0.010 |

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic Black | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.657 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.232 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.257 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.406 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.012 |

| Race/ethnicity – Asian American/ Pacific Islander | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.025 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.082 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.053 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.028 |

| Race/ethnicity – Hispanic | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.600 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.371 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.268 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.205 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.571 |

| Race/ethnicity – Other/ Multiple | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.119 | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.046 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.331 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.128 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.125 |

| Sexual identity – Heterosexual (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity –LGBTQ+ | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.003 | −0.14 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.04 | 0.001 | −0.13 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Income – Live comfortably (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Income – Live less than comfortably | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.084 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.026 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.001 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.054 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.001 |

Note: Results presented for are adjusted linear regression models, including covariates for age group, product use status, gender, race/ethnicity, and financial comfort, for the perceived harm for each product.

Comparisons of Perceived Harm of Each Product, by Product Use Status

For all products, participants who never used perceived each product to be more harmful than those who ever used the product and those who used the product in the past 30 days (p’s <0.02), with the exception of cigarettes (no difference in perceived harm). Participants who ever used cigarettes, nicotine e-cigarettes, nicotine pouches, and nicotine lozenges/tables perceived them to be more harmful than those who used in the past 30-days (p’s <0.001). See Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 4 for full details on perceived harm and product use status for each product, including post-hoc pairwise comparisons.

Figure 2:

Perceived Harm of Each Product (Mean and Standard Deviation), Overall and by Product Use Status

Perceived Addictiveness of Each Product, Overall and by Demographic Characteristics

Across all products assessed, between 9.7% to 17.2% of participants perceived that these products were not addictive (Supplemental Table 5). Overall, participants found cigarettes to be the most addictive (M: 3.09, SD: 1.01), followed by pod-based nicotine e-cigarettes (M: 3.01, SD: 1.03), and “other” nicotine e-cigarettes (M: 3.00, SD: 1.01) (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 6). Nicotine patches (M: 2.75, SD: 1.05), nicotine toothpicks (M: 2.75, SD: 1.06), and e-cigarettes with other ingredients (M: 2.66, SD: 1.06) were perceived as least addictive.

Figure 3:

Perceived Addictiveness of Each Product (Mean and Standard Deviation), Overall and by Age Group

Overall, participants aged 13–17 perceived each product to be more addictive than those aged 21–25 (p’s <0.002), with the exception of cigarettes, nicotine toothpicks, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients. Participants aged 18–20 perceived nicotine e-cigarettes to be more addictive than those aged 21–25 (p’s <0.004). Participants aged 18–20 and 21–25 perceived cigarettes and e-cigarettes with other ingredients to be less addictive than those aged 26–40 (p’s <0.007). See Supplemental Table 6 for full details on post-hoc pairwise comparisons of perceived addictiveness and age group for each product.

Participants who identified as Non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic had lower perceived addictiveness (compared to Non-Hispanic White) for cigarettes and all nicotine-containing products (p’s <0.002), except there were no differences for nicotine lozenges. Participants who identified as Asian American/ Pacific Islander had higher perceived addictiveness (compared to Non-Hispanic White) for e-cigarettes with other ingredients and THC e-cigarettes (p’s <0.015). Participants who identified as LGBTQ+ (compared to heterosexual/straight) had higher perceived addictiveness for cigarettes (p=0.038) and lower perceived addictiveness for e-cigarettes with other ingredients (p=0.004). Those who self-reported living less than comfortably had higher perceived addictiveness (compared to living comfortably) for cigarettes (p<0.001) and lower perceived addictiveness for e-cigarettes with other ingredients (p=0.029). See Table 2 for full adjusted regression results.

Table 2:

Perceived Addictiveness of Each Product, by Sociodemographic Variable

| Cigarettes | E-cigarettes with other ingredients | Disposable nicotine e-cigarettes | Pod-based nicotine e-cigarettes | “Other” nicotine e-cigarettes | THC e-cigarettes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | |

| Age 13–17 (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age 18–20 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.928 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.866 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.066 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.006 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.170 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.005 |

| Age 21–25 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.358 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.708 | −0.22 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.26 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.18 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.20 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Age 26+ | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.002 | −0.20 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.25 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.001 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.121 |

| Use – Never (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Use - Ever | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.30 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.310 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.688 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.568 | −0.39 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Use - Past 30 days | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.003 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.054 | −0.14 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.35 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Gender – Female (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gender - Male | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.661 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.941 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.033 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.013 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.045 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.020 |

| Gender- Non-Binary | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.580 | −0.20 | 0.08 | 0.007 | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.285 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.497 | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.261 | −0.20 | 0.08 | 0.007 |

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic Black | −0.33 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.210 | −0.33 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.39 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.32 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.023 |

| Race/ethnicity – Asian American/ Pacific Islander | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.081 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.002 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.178 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.088 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.261 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.015 |

| Race/ethnicity – Hispanic | −0.31 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.736 | −0.24 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.26 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.803 |

| Race/ethnicity – Other/ Multiple | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.013 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.393 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.022 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.022 | −0.15 | 0.08 | 0.053 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.811 |

| Sexual identity – Heterosexual (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity –LGBTQ+ | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.038 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.110 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.175 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.820 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.317 |

| Income – Live comfortably (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Income – Live less than comfortably | 0.12 | 0.03 | <0.001 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.029 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.303 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.566 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.541 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.421 |

| Nicotine pouches | Nicotine gum | Nicotine lozenges | Nicotine tablets | Nicotine patches | Nicotine toothpicks | |||||||||||||

| Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | Estimate | Std. Error | p-value | |

| Age 13–17 (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age 18–20 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.112 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.273 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.040 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.042 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.070 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.273 |

| Age 21–25 | −0.16 | 0.05 | 0.001 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.004 | −0.17 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.18 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.17 | 0.05 | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.012 |

| Age 26+ | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.114 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.198 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.060 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.038 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.049 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.126 |

| Use – Never (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Use - Ever | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.062 | −0.33 | 0.06 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.004 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.434 | −0.21 | 0.07 | 0.001 | −0.11 | 0.09 | 0.262 |

| Use - Past 30 days | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.059 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.085 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.048 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.159 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.281 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.169 |

| Gender – Female (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gender - Male | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.081 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.171 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.616 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.198 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.232 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.351 |

| Gender- Non-Binary | −0.14 | 0.07 | 0.057 | −0.16 | 0.07 | 0.027 | −0.19 | 0.07 | 0.010 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.120 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.112 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.220 |

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic White (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity – Non-Hispanic Black | −0.22 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.18 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.002 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.003 | −0.14 | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| Race/ethnicity – Asian American/ Pacific Islander | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.389 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.099 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.789 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.361 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.296 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.425 |

| Race/ethnicity – Hispanic | −0.16 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.04 | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.04 | 0.002 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.007 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.013 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity – Other/ Multiple | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.502 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.317 | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.456 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.676 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.346 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.329 |

| Sexual identity – Heterosexual (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity –LGBTQ+ | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.177 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.510 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.554 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.976 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.118 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.072 |

| Income – Live comfortably (ref) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Income – Live less than comfortably | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.879 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.536 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.360 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.333 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.877 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.088 |

Note: Results presented for are adjusted linear regression models, including covariates for age group, product use status, gender, race/ethnicity, and financial comfort, for the perceived addictiveness for each product.

Comparisons of Perceived Addictiveness of Each Product, by Product Use Status

There were no differences in perceived addictiveness across product use status for disposable nicotine e-cigarettes, nicotine pouches, nicotine tablets, and nicotine toothpicks. Participants who never used cigarettes, nicotine gums, nicotine lozenges, nicotine patches, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients had higher perceived addictiveness compared to those who ever used the product (p’s <0.01), with the exception of pod-based e-cigarettes and “other” e-cigarettes. Participants who ever used pod-based and “other” nicotine e-cigarettes perceived the two products to be more addictive than those who used in the past 30-days (p’s <0.01). Participants who ever used nicotine gums perceived the product to be less addictive than those who used in the past 30-days (p’s <0.001). See Figure 4 and Supplemental Table 7 for full details on perceived addictiveness and product use status for each product, including post-hoc pairwise comparisons.

Figure 4:

Perceived Addictiveness of Each Product (Mean and Standard Deviation), Overall and by Product Use Status

Discussion

This study is one of the first to look at perceptions of harm and addictiveness across age groups and across different nicotine products, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients. Cigarettes were perceived as most harmful and addictive compared to all other products, supporting that the decades of anti-smoking policy and intervention practices have successfully educated all age groups on the harms of smoking cigarettes.37 Yet, nicotine e-cigarettes have as much if not more nicotine than cigarettes, and are therefore just as, if not more, addictive than cigarettes.38,39 Moreover, the long-term negative health effects of e-cigarettes are still largely unknown. The Truth Initiative and The Real Cost Campaign have made efforts to educate the public, and especially young people, on the true harms of nicotine use, as have other education and prevention efforts.40,41

We found that perceived harm and addictiveness e-cigarettes with other ingredients and THC e-cigarettes were the lowest among the 11 products included in this study. Even though e-cigarettes with other ingredients do not have nicotine, they still contain chemicals such as propylene glycol and flavorants, and are therefore not harmless.4 People may first try e-cigarettes with other ingredients and then nicotine e-cigarettes, perhaps because of lower harm perceptions associated with the former product. Yet, the long-term effects of inhaling other aerosolized substances (e.g., vitamins) are not yet well understood.

Overall, we found age group differences in perceived harm and addictiveness across all products, with younger participants perceiving greater harm and addictiveness than older participants, similar to previous studies using national PATH data.31,42 The exception was for e-cigarettes with other ingredients, for which older participants perceived more harm and addictiveness than younger participants. This may be due to the fact that e-cigarettes with other ingredients are a newer product and marketed as providing health benefits,4 and adolescents and young adults may have similar views to how they initially misperceived Juul to have low harm because they contained “only water vapor.”19 Across all participant groups, perceived harm and addictiveness of THC e-cigarettes was lower than for nicotine e-cigarettes, similar to findings on other cannabis harm perception studies.30,43 This finding suggests the need for additional education, especially for adolescents and young adults, around the harms of e-cigarettes with other ingredients and THC e-cigarettes, as people may view these products as a less harmful alternative to nicotine use.44 We found that nicotine pouches, another product that is becoming increasing popular especially among adolescents and young adults,7 were perceived as the next most harmful and addictive product after the nicotine e-cigarettes, with adolescents and young adults finding it more harmful and addictive than other nicotine products (lozenges, tablets, gums, patches, toothpicks), THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients.

Participants who had experience using all products studied tended to perceive less harm and addictiveness across all products, confirming past research that similarly showed that people who used tobacco had lower tobacco-related perceived risk,45 with studies showing a predictive relationship between perceived low risk and subsequent use.19,23,24

We found that certain sociodemographic groups, such as people who identify as LGBTQ+, Non-Hispanic Black, or Hispanic, had lower perceived harm and addictiveness for all products studied. These sociodemographic groups who perceived lower risk also tend to be the groups who are targeted by industry marketing or live in areas with a high concentration of tobacco/e-cigarette and cannabis shops,46,47 factors that are associated with lower perceptions of harm. There is evidence to indicate that certain sociodemographic groups may be using substances more because they are receiving targeted marketing.48–50 Future research should continue to examine potential drivers of differences in use by sociodemographic groups.49

Comprehensive efforts in educating around the harms and addictiveness of cigarettes51 must similarly be made to address the lower perceived risk of newer nicotine products, non-nicotine e-cigarettes, and cannabis e-cigarettes. Given our findings around differences in perceptions of harm and addictiveness by age groups and other demographic factors, and that low misperceived harm of products is associated with use,19,52 it is critical that prevention strategies include information to address misperceptions. This is especially true for educating on the harm and addictiveness of any nicotine products with emerging popularity, such as nicotine pouches.7 This includes tailoring school-based curricula as well as mass media campaigns to educate on the health risks of using such products.41 Additionally, marketing and advertising should be regulated to prevent such industry targeting to begin with. Education of harms and addictiveness also plays a critical role in clinical settings, as healthcare providers, especially pediatricians, should routinely discuss the harms and addictiveness of such products with their patients.53

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations and implications for future research. Our study drew from a convenience sample, and thus findings regarding perceived harm and addictiveness may not be generalizable to the broader U.S. population. We did not include a “Don’t know” option for perceived harm and addictiveness, and some participants, especially people who have never used the products, may not know the harm and addictiveness of the products. Additionally, future surveys should make efforts to clearly define the meaning of “harm” and “addictiveness” to ensure that participants are interpreting the questions as intended. Adolescents especially may not understand what the term “addiction” really means and its negative consequences.19,52,54 It is important to work on changing the social norms around both the health harms and addictive nature of all products included in this study.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study provides novel insight on the perceived risk of a variety of products (nicotine products, THC e-cigarettes, and e-cigarettes with other ingredients) and across adolescents to young adults to adults. Future studies should continue to examine risk perceptions of new and emerging nicotine and non-nicotine products and gather longitudinal data on subsequent product use outcomes. These findings provide further evidence to support the need for increased efforts in prevention messaging and education, not just around cigarettes and nicotine e-cigarettes, but for THC, CBD, and other non-nicotine e-cigarette products to all age groups. For example, future research can examine the effectiveness of messaging campaigns, especially educating around the harms of new and emerging products, to specific age groups and sociodemographic populations. Public health practitioners, clinicians, educators, school administrators, and other key stakeholders could educate the public about the harms of such product use and should continue to debunk myths especially among certain minority groups who have disproportionately lower levels of perceived risk of products. Addressing the disparities in risk perceptions will ultimately address disparities and inequities in product use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Agamroop Kaur, a member of the REACH Lab’s Youth Action Board, for her help piloting the survey with adolescents and adults and for compiling their feedback. We are grateful to the support from David Cash, BA, Research Director, and Juanita Greene, BA, Research Coordinator, in the REACH Lab for their assistance in setting up and testing the online survey used in this study. They were not compensated for their time.

Funding Source:

The research reported in this publication was supported by the Taube Research Faculty Scholar Endowment to Bonnie Halpern-Felsher and through additional support from grant U54 HL147127 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, Co-PI). The research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K99CA267477 and Instructor K Award Support from the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute to Shivani Mathur Gaiha. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: All authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Halpern-Felsher is a paid expert scientist in some litigation against e-cigarette companies and an unpaid scientific advisor and expert witness regarding some tobacco-related policies. She is also the Founder and Executive Director of the Tobacco Prevention Toolkit and the Cannabis Awareness and Prevention Toolkit. Drs. Liu, McCauley, and Gaiha have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- 1.Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cooper M, Cornelius M, Jamal A, Cullen KA. Tobacco Product Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2022. 2022;71(45). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramarow EA. Current Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults Aged 18 and Over: United States, 202. 2023;(475). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birdsey J, Cornelius M, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among U.S. Middle and High School Students — National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(44):1173–1182. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7244a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaiha SM, Lin C, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Use Patterns, Flavors, Brands, and Ingredients of Nonnicotine e-Cigarettes Among Adolescents, Young Adults, and Adults in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2216194-e2216194. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J, Tan ASL, Winickoff JP, Rees VW. Correlates of adolescent sole-, dual- and poly-use of cannabis, vaped nicotine, and combusted tobacco. Addict Behav. 2023;146:107804. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaiha SM, Lin C, Lempert LK, Halpern-Felsher B. Use, marketing, and appeal of oral nicotine products among adolescents, young adults, and adults. Addict Behav. 2023;140:107632. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patwardhan S, Fagerström K. The New Nicotine Pouch Category: A Tobacco Harm Reduction Tool? Nicotine Tob Res. 2022;24(4):623–625. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Results from the Annual National Youth Tobacco Survey. Published online 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg CJ, Krishnan N, Graham AL, Abroms LC. A synthesis of the literature to inform vaping cessation interventions for young adults. Addict Behav. 2021;119(March):106898. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osman A, Kowitt SD, Ranney LM, Heck C, Goldstein AO. Risk factors for multiple tobacco product use among high school youth. Addict Behav. 2019;99:106068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith CL, Cooper BR, Miguel A, Hill L, Roll J, McPherson S. Predictors of cannabis and tobacco co-use in youth: exploring the mediating role of age at first use in the population assessment of tobacco health (PATH) study. J Cannabis Res. 2021;3(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s42238-021-00072-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Knoll SJ, Pascale MP, et al. Intention to quit or reduce e-cigarettes, cannabis, and their co-use among a school-based sample of adolescents. Addict Behav. 2024;157:108101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.108101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan M, Cross SJ, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. J Physiol. 2015;593(16):3397–3412. doi: 10.1113/JP270492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Counotte DS, Smit AB, Pattij T, Spijker S. Development of the motivational system during adolescence, and its sensitivity to disruption by nicotine. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1(4):430–443. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glantz S, Jeffers A, Winickoff JP. Nicotine Addiction and Intensity of e-Cigarette Use by Adolescents in the US, 2014 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2240671-e2240671. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PrevalenceDai H. and Factors Associated With Youth Vaping Cessation Intention and Quit Attempts. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roditis M, Delucchi K, Cash D, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ Perceptions of Health Risks, Social Risks, and Benefits Differ Across Tobacco Products. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(5):558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKelvey K, Baiocchi M, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Use and Perceptions of Pod-Based Electronic Cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183535-e183535. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorukanti A, Delucchi K, Ling P, Fisher-Travis R, Halpern-Felsher B. Adolescents’ Attitudes towards E-cigarette Ingredients, Safety, Addictive Properties, Social Norms, and Regulation HHS Public Access. Prev Med. 2017;94:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glanz KE, Lewis FME, Rimer BK. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Jossey-Bass/Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madden TJ, Ellen PS, Ajzen I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1992;18(1):3–9. doi: 10.1177/0146167292181001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker MA, Villanti AC, Quisenberry AJ, et al. Tobacco Product Harm Perceptions and New Use. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181505. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong G, Simon P, Mayer ME, et al. Harm Perceptions of Alternative Tobacco Products among US Adolescents. Tob Regul Sci. 2019;5(3):242–252. doi: 10.18001/TRS.5.3.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song AV, Morrell HER, Cornell JL, et al. Perceptions of smoking-related risks and benefits as predictors of adolescent smoking initiation. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):487–492. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams RJ, Herzog TA, Simmons VN. Risk perception and motivation to quit smoking: A partial test of the Health Action Process Approach. Addict Behav. 2011;36(7):789–791. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganz O, Johnson AL, Cohn AM, et al. Tobacco harm perceptions and use among sexual and gender minorities: findings from a national sample of young adults in the United States. Addict Behav. 2018;81:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patterson JG, Keller-Hamilton B, Wedel A, et al. Absolute and relative e-cigarette harm perceptions among young adult lesbian and bisexual women and nonbinary people assigned female at birth. Addict Behav. 2023;146:107788. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popova L, McDonald EA, Sidhu S, et al. Perceived harms and benefits of tobacco, marijuana, and electronic vaporizers among young adults in Colorado: implications for health education and research. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2017;112(10):1821–1829. doi: 10.1111/add.13854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, McLaughlin S, Lazaro A, Halpern-Felsher B. What Does It Meme? A Qualitative Analysis of Adolescents’ Perceptions of Tobacco and Marijuana Messaging. Public Health Rep. Published online 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bluestein MA, Harrell MB, Hébert ET, et al. Associations Between Perceptions of e-Cigarette Harmfulness and Addictiveness and the Age of E-Cigarette Initiation Among the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Youth. Tob Use Insights. 2022;15:1179173X2211336. doi: 10.1177/1179173X221133645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qualtrics XM // The Leading Experience Management Software. https://www.qualtrics.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qualtrics. Unlock breakthrough insights with market research panels. https://www.qualtrics.com/research-services/online-sample/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams VF, Smith AA, Villanti AC, et al. Validity of a Subjective Financial Situation Measure to Assess Socioeconomic Status in US Young Adults. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(5). https://journals.lww.com/jphmp/fulltext/2017/09000/validity_of_a_subjective_financial_situation.10.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halpern-Felsher B, Kim H. Measuring E-cigarette use, dependence, and perceptions: Important principles and considerations to advance tobacco regulatory science. Addict Behav. 2018;79(November 2017):201–202. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKelvey K, Gaiha SM, Delucchi KL, Halpern-Felsher B. Measures of both perceived general and specific risks and benefits differentially predict adolescent and young adult tobacco and marijuana use: findings from a Prospective Cohort Study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):91–91. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00765-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. The history of adolescent tobacco prevention and cessation programs and recommendations for moving forward. In: Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Health. Elsevier; 2023:400–414. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818872-9.00154-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackler RK, Ramamurthi D. Nicotine arms race: JUUL and the high-nicotine product market. Tob Control. 2019;28(6):623–628. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin C, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. Nicotine Dependence from Different E-Cigarette Devices and Combustible Cigarettes among US Adolescent and Young Adult Users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):5846. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19105846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. A Breath of Knowledge: Overview of Current Adolescent E-cigarette Prevention and Cessation Programs. Curr Addict Rep. 2020;7(4):520–532. doi: 10.1007/s40429-020-00345-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. School-based programs to prevent adolescent e-cigarette use: A report card. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2022;52(6):101204–101204. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2022.101204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strong DR, Messer K, White M, et al. Youth perception of harm and addictiveness of tobacco products: Findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study (Wave 1). Addict Behav. 2019;92:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammond CJ, Chaney A, Hendrickson B, Sharma P. Cannabis use among U.S. adolescents in the era of marijuana legalization: a review of changing use patterns, comorbidity, and health correlates. Int Rev Psychiatry Abingdon Engl. 2020;32(3):221–234. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1713056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chadi N, Minato C, Stanwick R. Cannabis vaping: Understanding the health risks of a rapidly emerging trend. Paediatr Child Health. 2020;25(Suppl 1):S16–S20. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxaa016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell BK, Le T, Gubner NR, Guydish J. Health risk perceptions and reasons for use of tobacco products among clients in addictions treatment. Addict Behav. 2019;91:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson A, Ganz O, Pearson J, Celcis N, Vallone D, Villanti AC. How the industry is marketing menthol cigarettes: the audience, the message and the medium. Tob Control. 2015;24(6):594–600. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan ASL, Hanby EP, Sanders-Jackson A, Lee S, Viswanath K, Potter J. Inequities in tobacco advertising exposure among young adult sexual, racial and ethnic minorities: examining intersectionality of sexual orientation with race and ethnicity. Tob Control. 2021;30(1):84–93. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathur Gaiha S, Halpern-Felsher B, Feld AL, Gaber J, Rogers T, Henriksen L. JUUL and other e-cigarettes: Socio-demographic factors associated with use and susceptibility in California. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101457. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCauley DM, Baiocchi M, Gaiha SM, Halpern-Felsher B. Sociodemographic differences in use of nicotine, cannabis, and non-nicotine E-cigarette devices. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2024;255:111061. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.111061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaiha SM, Rao P, Halpern-Felsher B. Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Adolescents’ and Young Adults’ Susceptibility, Use, and Intended Future Use of Different E-Cigarette Devices. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):1941. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19041941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flay BR. School-based smoking prevention programs with the promise of long-term effects. Tob Induc Dis. 2009;5(1):6–6. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-5-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roditis M, Lee J, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescent (Mis)Perceptions About Nicotine Addiction: Results From a Mixed-Methods Study. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2016;43(2):156–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198115598985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pepper JK, Gilkey MB, Brewer NT. Physicians’ counseling of adolescents regarding E-cigarette use. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(6):580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J, Halpern-Felsher BL. What Does It Take to Be a Smoker? Adolescents’ Characterization of Different Smoker Types. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(11):1106–1113. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.