Abstract

RNA modification has emerged as an important epigenetic mechanism that controls abnormal metabolism and growth in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). However, the roles of RNA N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) modification in AML remain elusive. Here, we report that ac4C and its catalytic enzyme NAT10 drive leukaemogenesis and sustain self-renewal of leukaemic stem cells/leukaemia-initiating cells through reprogramming serine metabolism. Mechanistically, NAT10 facilitates exogenous serine uptake and de novo biosynthesis through ac4C-mediated translation enhancement of the serine transporter SLC1A4 and the transcription regulators HOXA9 and MENIN that activate transcription of serine synthesis pathway genes. We further characterize fludarabine as an inhibitor of NAT10 and demonstrate that pharmacological inhibition of NAT10 targets serine metabolic vulnerability, triggering substantial anti-leukaemia effects both in vitro and in vivo. Collectively, our study demonstrates the functional importance of ac4C and NAT10 in metabolism control and leukaemogenesis, providing insights into the potential of targeting NAT10 for AML therapy.

Subject terms: Cancer metabolism, Cancer stem cells, Cancer epigenetics

Zhang, Huang, Wang, Long et al. report that NAT10 enhances serine uptake and biosynthesis in an ac4C-dependent mechanism, thereby promoting stemness and progression in acute myeloid leukaemia.

Main

AML is a prevalent and aggressive haematopoietic malignancy developed from a subset of initiating cells known as leukaemic stem cells (LSCs)/leukaemia-initiating cells (LICs)1–5. Although it is well acknowledged that genetic mutations, including chromosomal rearrangements and somatic mutations, drive the transformation of haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) into LSCs/LICs6–9, non-genetic abnormalities are emerging as crucial mechanisms contributing to leukaemogenesis.

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of AML10. Amino acids as the major source of nitrogen and carbon donors are required at high levels in LSCs11. Blockage of exogenous amino acid uptake selectively eradicates LSCs when combined with venetoclax and azacitidine treatment11. Of note, recent studies unveiled the dependency of serine in AML, particularly in those harbouring internal tandem duplications of the FLT3 gene (FLT3-ITD)12–15. As a conditional essential amino acid, serine can be imported into cells by transporters or synthesized de novo through the serine synthesis pathway (SSP), and then used for glycine and cysteine synthesis, the folate cycle, nucleotide synthesis, the methionine cycle and antioxidant defence16,17. Pharmacological inhibition of PHGDH, a rate-limiting enzyme in SSP, inhibited leukaemia progression and sensitized FLT3-ITD AMLs to chemotherapeutic cytarabine13. Therefore, serine metabolism represents a metabolic vulnerability in AML that could be exploited for therapeutic intervention.

Deregulation of RNA modifications and their machinery is an important epigenetic contributor to leukemogenesis and is closely associated with metabolic alterations in AML18–22. We recently reported that METTL3/METTL14-mediated N6-methyladenosine (m6A) promotes glutamine metabolism through enhancing mRNA stability and translation of SLC1A5, GPT2 and MYC in an IGF2BP2-dependent manner20. Furthermore, the other m6A writer METTL16 reprograms branched-chain amino acid metabolism in AML through regulating the expression of BCAT1 and BCAT2 (ref. 21). Nonetheless, it is much less known whether other types of RNA modifications play a role in rewiring AML metabolism and could serve as therapeutic targets.

N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C), a type of RNA modification conserved throughout bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes, is the sole acetylation event in eukaryotic RNAs23. The formation of ac4C is catalysed by N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10), a member of the GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase family24–27. It has been long believed that ac4C is present only in abundant RNA molecules such as 18s rRNA and tRNAs26,27. However, it was recently found that NAT10 also catalyses ac4C modification in messenger RNAs and thus controls mRNA translation efficiency25. Growing evidence indicates the significance of mRNA ac4C in solid tumours28–35, but its role in leukaemia remains unknown.

Here, we report that ac4C and its writer NAT10 play vital roles in AML to drive leukaemogenesis and LSC self-renewal through reprogramming serine metabolism. Furthermore, we identify NAT10 as a target of fludarabine, an ‘old drug’ used in the clinical treatment of leukaemia36. Inhibition of NAT10 by fludarabine or the known NAT10 inhibitor Remodelin can effectively eradicate AML cells both in vitro and in mouse models. Our findings uncover the ac4C epitranscriptomic mechanism in AML pathogenesis and highlight NAT10 as an appealing therapeutic target for AML treatment.

Results

Epigenetic CRISPR screen reveals NAT10 is essential for AML

To investigate the RNA epigenetic vulnerability in AML, we conducted an analysis of the dependency of AML on 232 RNA epigenetic regulators using The Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) data (https://depmap.org/portal)37. The results revealed that 70 (~30%) RNA epigenetic regulators are essential for the growth and survival of AML cells, as indicated by a CERES score below −0.5 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). It is noteworthy that the CERES scores of RNA epigenetic regulators were significantly lower than those of other genes, suggesting a potentially critical role of the RNA epigenetic mechanisms in AML (Fig. 1a).

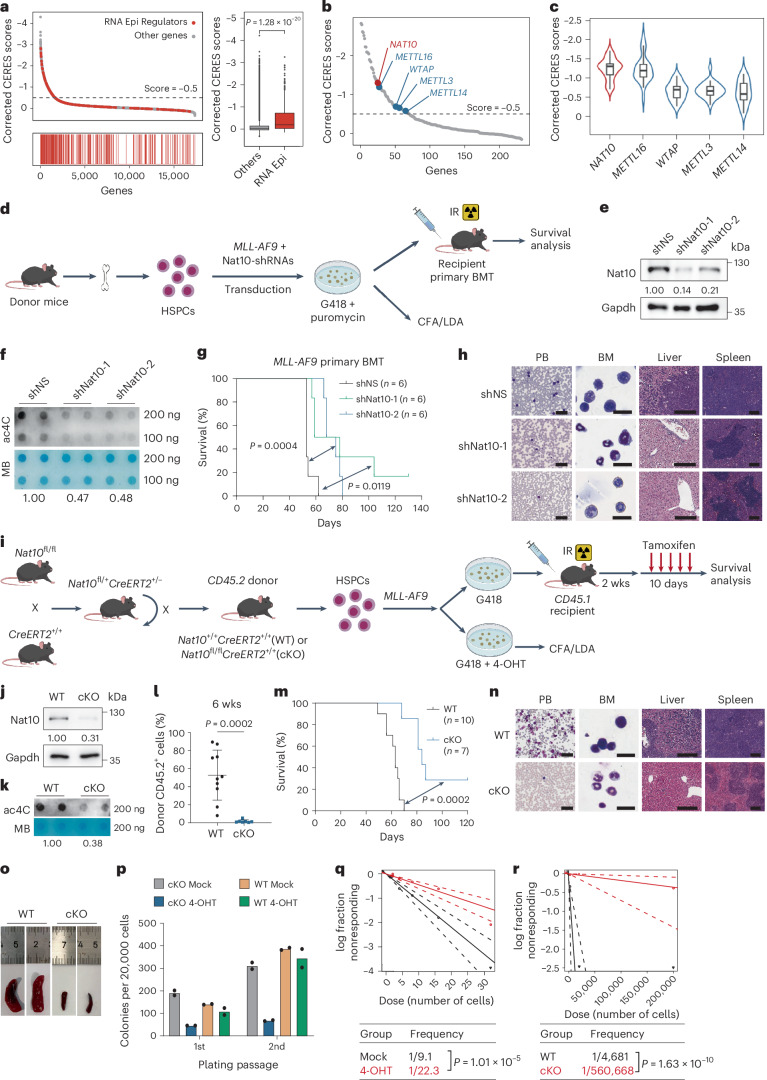

Fig. 1. Nat10 is essential for AML development and LSC/LIC self-renewal.

a, Corrected CERES scores of genes from genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 essentiality screens across 24 human AML cell lines (left). CERES scores of RNA epigenetic regulators (n = 232) and other genes (n = 17,699) (right). Centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range; points, outliers. b, Dot-plot of corrected CERES scores illustrating the top candidates of RNA epigenetic regulators. c, Violin plots showing the median and interquartile range of the CERES scores of NAT10 as well as m6A writers (n = 24). Centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. d, Experimental scheme of MLL-AF9-driven AML mouse model. IR, irradiation. e,f, Western blot analysis (e) and dot-blot analysis (f) showing the decrease of Nat10 protein and RNA ac4C modification in MLL-AF9 transformed mouse HSPCs by Nat10 shRNAs. MB, methylene blue. g,h, The effect of Nat10 knockdown on MLL-AF9-induced leukaemogenesis (n = 6). Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in g. Wright–Giemsa staining of PB and BM, and haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver and spleen of recipient mice at the end point are shown in h. Scale bars, 50 μm for PB, 20 μm for BM, 200 μm for liver and 300 μm for spleen. i, Experimental scheme for generation of Nat10-cKO mice and MLL-AF9-driven Nat10-cKO AML model. j,k, Western blot analysis (j) and dot-blot analysis (k) showing the ablation of Nat10 and ac4C levels in the BM cells of WT and Nat10-cKO mice 10 days after in vivo tamoxifen treatment. l–o, The effect of Nat10 KO on MLL-AF9-induced de novo leukaemogenesis in lethally irradiated recipient mice (WT, n = 10; cKO, n = 7). Percentages of CD45.2+ donor cells in the PB 6 weeks after BMT are shown in l. Values are mean ± s.d. and a two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in m. Wright–Giemsa staining of PB and BM, and H&E staining of liver and spleen of recipient mice at the end point are shown in n. Scale bars are the same as in h. Representative images of spleens are shown in o. p, Colony numbers of MLL-AF9-transduced HSPCs from Nat10+/+CreERT2 (WT) or Nat10fl/flCreERT2 (cKO) mice in methylcellulose medium. 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, 1 μM) was added to induce Nat10 KO as in q. q, In vitro LDA using MLL-AF9-transduced HSPCs from WT or Nat10-cKO mice. r, In vivo LDA using BM leukaemia cells from primary BMT mice in m. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in p. Two-sided chi-squared tests were used in q and r. A two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test was used in a. Log-rank tests were used in g and m. Generic Diagramming Platform (https://biogdp.com/) was used to draw schematic diagrams in d and i.

Notably, there was a remarkable reduction in sgRNAs targeting the ac4C writer NAT10 in AML cells (Fig. 1b). The CERES score of NAT10 is −1.3, lower than that of the m6A writers METTL3, METTL14, WTAP and METTL16 that have been previously implicated as key players in the development and progression of AML21,38–41 (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we checked the clinical relevance of the top candidates with a CERES score below −1.0 and found that NAT10 was one of the only two genes whose expression is upregulated in AML patients and is positively associated with unfavourable prognosis in AML (Extended Data Fig. 1b). These results suggest that the ac4C writer NAT10 may be a critical oncogene in AML.

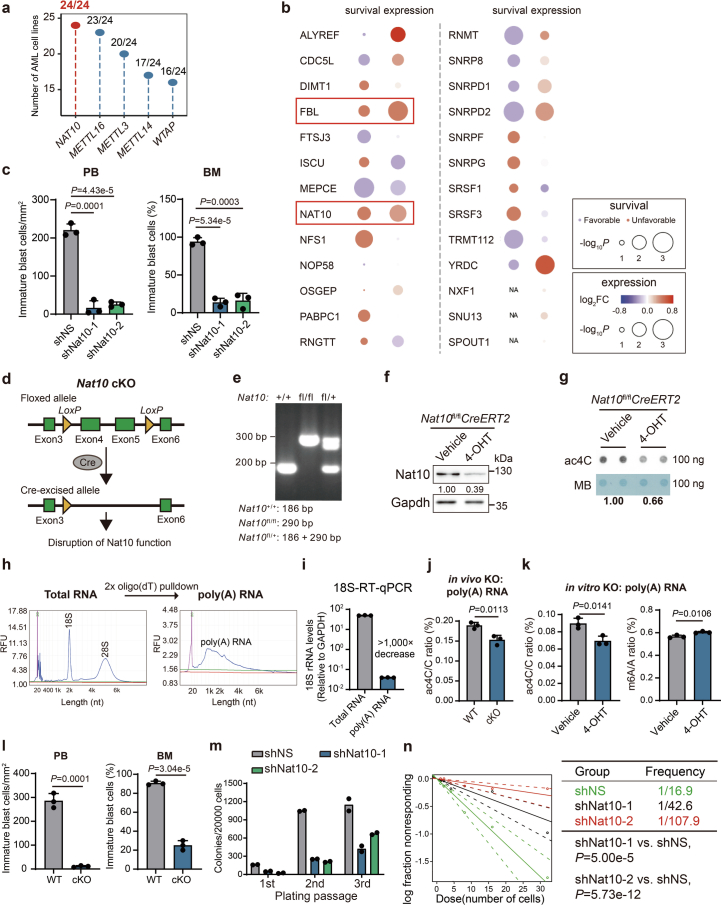

Extended Data Fig. 1. NAT10 is essential for AML.

(a) Number of AML cell lines with loss of fitness (CERES score lower than −0.5) when depleting specific genes. (b) Expression and survival analyses of TCGA-AML data showing the clinical relevance of the top 26 candidate genes with a CERES score lower than −1.0. (c) Histograms showing knockdown of Nat10 reduced the numbers and percentages of immature blast cells in peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) from the primary BMT recipient mice. The number of immature blast cells were counted in 3 representative fields of Wright–Giemsa stained PB smear or BM cells. (d) The schematic diagram showing the strategy of conditional knockout of Nat10. (e) Genotyping of Nat10+/+, Nat10fl/fl or Nat10fl/+ mouse. (f,g) The reduction of Nat10 and RNA ac4C modification in the c-Kit+ BM cells of NAT10fl/flCreERT2 mice with or without in vitro 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) treatment was confirmed by western blot (f) and dot blot (g) analyses, respectively. Cells were collected from the 1st passage of CFA. (h) Poly(A) RNA was isolated through two rounds of oligo(dT) pulldown and the purity was verified through size distribution in Qsep Bio-Fragment Bioanalyzer profiling. (i) Validation of poly(A) RNA purity through RT–qPCR with primers specific to 18S rRNA and GAPDH. (j) LC–MS/MS showing the reduction of ac4C modification levels in the poly(A) RNA of c-Kit+ BM cells from NAT10fl/flCreERT2 mice with in vivo tamoxifen treatment. (k) LC–MS/MS showing the ac4C modification levels (left) and m6A modification levels (right) in the poly(A) RNA of c-Kit+ BM cells from NAT10fl/flCreERT2 mice with in vitro 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) treatment. (l) Histograms showing knockout of Nat10 reduced the numbers and percentages of immature blast cells in peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) from the primary BMT recipient mice. The number of immature blast cells were counted in 3 representative fields of Wright–Giemsa stained PB smear or BM cells. (m) Colony numbers of mouse HSPCs transduced with MLL-AF9 plus shRNAs targeting Nat10 or non-specific control (shNS) in methylcellulose medium. (n) In vitro LDA in mouse HSPCs co-transduced with MLL-AF9 and shNS or shRNAs targeting Nat10. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in c, i, j, k and l. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in m. Two-sided Chi-squared tests were used in n. Images in f and g were representative of three independent experiments.

NAT10 promotes AML development and LSC/LIC self-renewal

To investigate the roles of NAT10 in AML, we co-transduced MLL-AF9 with two lentiviral short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against Nat10 into mouse HSPCs and transplanted the double-transduction-positive donor cells into lethally irradiated recipient mice (Fig. 1d–f). Silencing of Nat10 significantly prolonged the survival of recipient mice, along with a decrease in the number of immature blast cells in both peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM), as well as a reduction in leukaemia cell infiltration and organ architecture disruption in spleens and livers (Fig. 1g,h and Extended Data Fig. 1c).

To further confirm the in vivo function of Nat10, we also generated Nat10fl/flCreERT2 conditional knockout (cKO) mice (referred to as Nat10-cKO) (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 1d,e). The ablation of Nat10 and a reduction of mRNA ac4C levels in the HSPCs of Nat10-cKO mice with in vitro 4-OHT induction or in vivo tamoxifen treatment was confirmed (Fig. 1j,k and Extended Data Fig. 1f–k). We transplanted lethally irradiated recipient mice with MLL-AF9-transduced HSPCs from Nat10+/+CreERT2 (Nat10-WT) or Nat10-cKO mice (Fig. 1i). Consistent with the results of shRNA knockdown, tamoxifen-induced knockout (KO) of Nat10 significantly delayed MLL-AF9-mediated leukaemogenesis and substantially prolonged the survival of recipient mice (Fig. 1l,m). This was again accompanied by a decrease in immature blast cells in PB and BM, and less leukaemia cell infiltration in livers and spleens (Fig. 1n and Extended Data Fig. 1l). Of note, the severity of splenomegaly was significantly ameliorated in Nat10-cKO AML mice (Fig. 1o).

We further evaluated the impact of Nat10 depletion on LSCs/LICs. Serial colony-forming assay (CFA) and in vitro limiting dilution assays (LDAs) showed that both knockdown and KO of Nat10 remarkably impaired MLL-AF9-mediated colony formation/immortalization of HSPCs in methylcellulose medium and the stemness of AML cells, respectively (Fig. 1p,q and Extended Data Fig. 1m,n). Furthermore, in vivo LDAs showed that the frequency of LSCs/LICs in the BM of Nat10-cKO leukaemic mice is dramatically decreased compared with the control group (Fig. 1r). These results together demonstrate that Nat10 is critical for the maintenance of LSCs/LICs self-renewal.

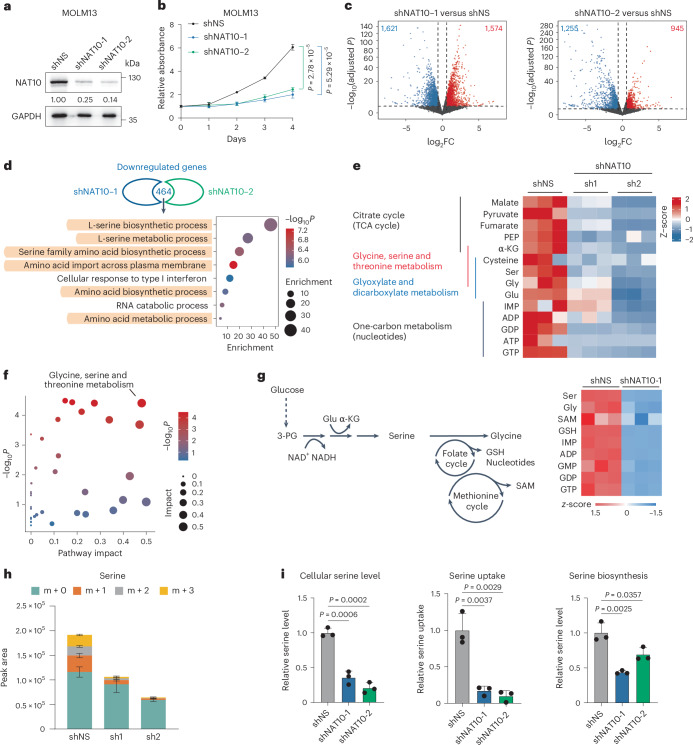

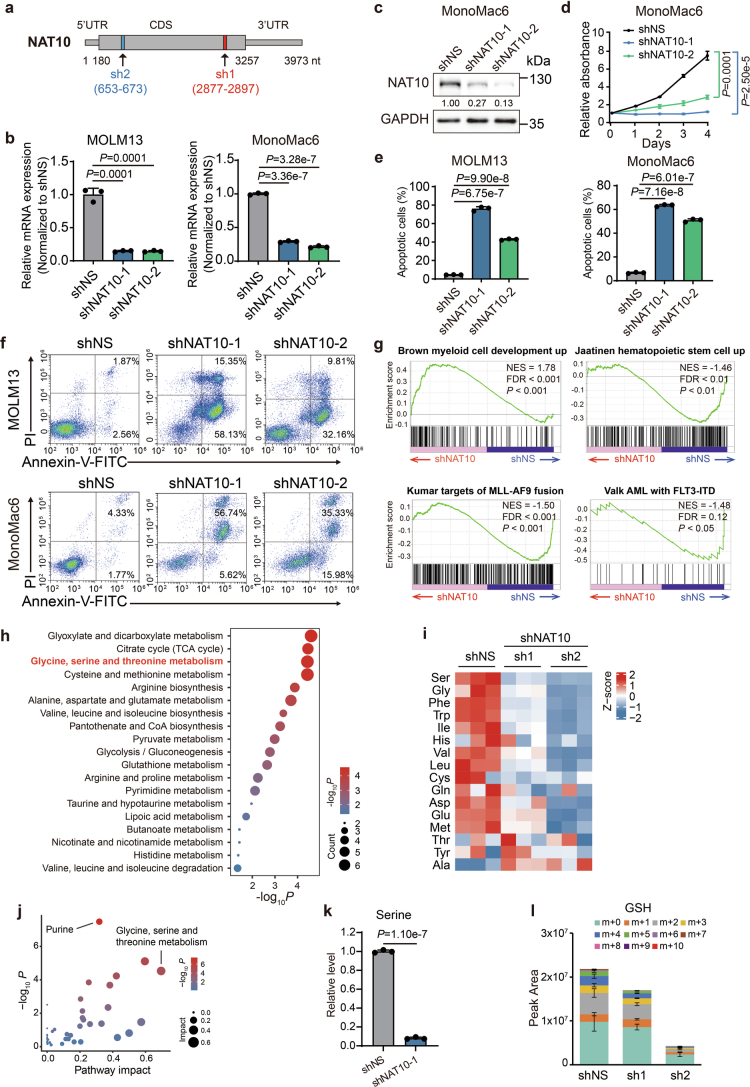

Rewiring of serine metabolism in AML cells by NAT10

In human AML cell lines MOLM13 and MonoMac6, knockdown of NAT10 by shRNAs also exhibited anti-leukaemia effects, as shown by the suppression of cell growth and the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 2a,b, Extended Data Fig. 2a–f and Supplementary Fig. 1a). To investigate how NAT10 affects the survival of leukaemia cells, we conducted RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells. Transcriptome profiling identified 3,195 and 2,200 differentially expressed genes (DEGs; fold change >1.5 or <0.667, adjusted P < 0.05) in MOLM13 cells transduced with shNAT10-1 and shNAT10-2, respectively (Fig. 2c). Gene set enrichment analysis revealed an enrichment of the upregulated genes in myeloid cell development, while the downregulated genes were associated with stemness and AML with MLL-AF9 and FLT3-ITD (Extended Data Fig. 2g). Notably, downregulated genes were also enriched in the amino acid metabolism pathway, especially the serine metabolism pathway (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. Transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses reveal NAT10 promotes serine uptake and biosynthesis.

a, Western blotting showing the knockdown efficiency of NAT10 in MOLM13 cells on day 4 post lentiviral shRNA transduction. b, Methylthialazole tetrazolium (MTT) assays showing the effects of NAT10 knockdown on cell proliferation in MOLM13 cells. c, Volcano plots showing DEGs in MOLM13 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown as identified by RNA-seq. Red, significant upregulated genes (fold change >1.5, adjusted P value < 0.05). Blue, significant downregulated genes (fold change <0.667, adjusted P value < 0.05). d, The intersection of the downregulated NAT10 targets in MOLM13 cells after NAT10 knockdown by two shRNAs. Bubble diagram showing the enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) pathways by the 464 overlapping downregulated transcripts. e, Heatmap showing levels of representative metabolites detected by LC–MS in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells labelled with U-13C-glucose for 16 h. f, Bubble diagram showing the most impacted metabolic pathway with enrichment of reduced metabolites upon NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 cells. g, Schematic representation of serine metabolism pathway and heatmap showing the changes of metabolites in this pathway in MOLM13 cells after NAT10 knockdown as identified by LC–MS without isotope labelling. h, Histograms showing total levels and isotopologue distribution (m + x; x, numbers of 13C) of serine measured by LC–MS in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells. Cells were grown in medium containing U-13C-glucose for 16 h before sample collection. i, The levels of total intracellular serine (left), serine uptake (middle) and serine biosynthesis (right) were measured by fluorescent quantification in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells on day 4 post-transduction of lentiviral shRNAs. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in b, h and i. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in b and i. Two-tailed Wald test adjusted with Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was used in c. Hypergeometric tests were used in d and f.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses reveal NAT10 regulates serine metabolism in AML cells.

(a) The schematic diagram showing the targeting sites of NAT10 shRNAs. (b) mRNA levels of NAT10 in MOLM13 (left) and MonoMac6 (right) cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. (c) Western blotting showing the knockdown efficiency of NAT10 in MonoMac6 cells on day 4 post-transduction of lentiviral shRNAs. (d) MTT assays showing the effects of NAT10 knockdown on cell proliferation in MonoMac6 cells. Cells were seeded on day 4 post-transduction (denoted as day 0 in the growth curves in MTT). (e) Histograms showing the percentages of apoptotic cells in control or NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 and MonoMac6 cells as detected by FITC-Annexin V/PI staining and flow cytometry analysis. Annexin V positive cells were defined as apoptotic cells. Apoptosis was detected on day 5 post-transduction of lentiviral shRNAs. (f) Flow-cytometric analysis of cell apoptosis in MOLM13 (upper) and MonoMac6 (bottom) cells on day 5 after NAT10 knockdown. (g) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of DEGs in MOLM13 cells after NAT10 knockdown. (h) Bubble diagram showing enrichment of metabolic pathways by the metabolites with reduced level after NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 cells. (i) Heatmap showing the changes of detected amino acids on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 cells. (j) Bubble diagram showing the most impacted metabolic pathways with enrichment of reduced metabolites upon NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 cells. (k) Total levels of serine measured by LC–MS in MOLM13 cells transduced with NAT10 shRNAs or shNS for 4 days. (l) Total levels and isotopologue distribution (m + x; x, numbers of 13C) of GSH measured by LC–MS in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells on day 4 post-transduction of shRNAs. Cells were grown in medium containing U-13C-glucose for 16 hours before sample collection. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in b, d, e, k and l. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in b, d, e, and k. Images in c and f were representative of three independent experiments.

Indeed, global isotope-tracing metabolomic confirmed that NAT10 knockdown greatly affected metabolites involved in glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, as well as the connected tricarboxylic acid cycle and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism in MOLM13 cells (Fig. 2e,f and Extended Data Fig. 2h,i). A metabolomic profiling without stable isotope labelling also validated that glycine, serine and threonine metabolism is the most affected pathway when NAT10 was silenced (Extended Data Fig. 2j). In addition, the levels of serine and its downstream metabolites, including glycine, antioxidant glutathione (GSH) and nucleotides, were significantly reduced upon NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 2k).

Serine can be acquired from the extracellular environment or de novo synthesized utilizing glucose16. Further analysis of the isotope-tracing data showed that NAT10 knockdown dramatically reduced the incorporation of 13C from U-13C-glucose into serine and its downstream metabolites, such as GSH (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 2l). In addition, the abundance of unlabelled serine (M + 0) decreased upon NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 2h). Consistent with the LC–MS data, fluorescent quantification analyses showed that NAT10 knockdown significantly reduced the total levels of intracellular serine in both complete and serine/glycine-deprived medium and significantly inhibited cellular consumption of serine from the complete medium (Fig. 2i). These results together demonstrate that knockdown of NAT10 represses both uptake and biosynthesis of serine.

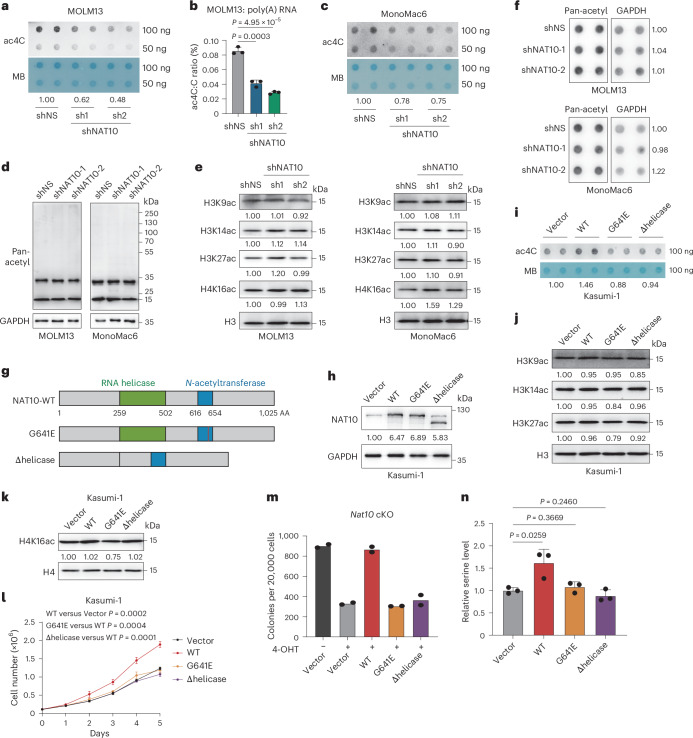

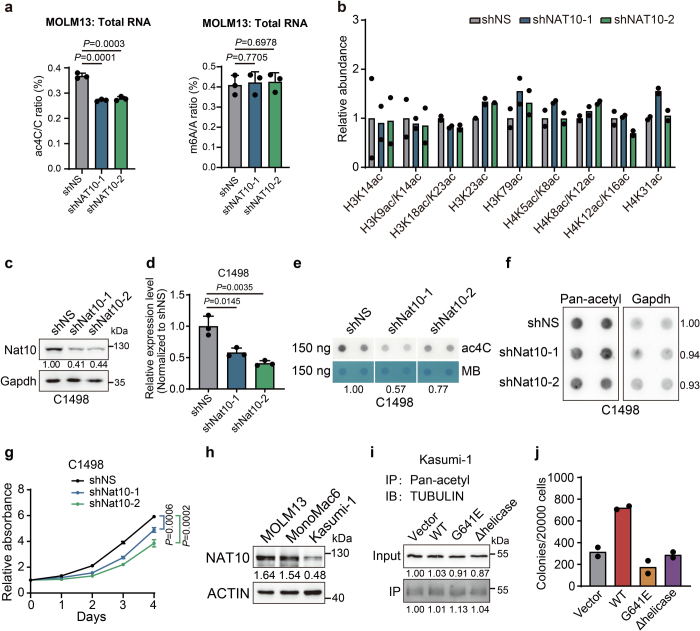

The oncogenic functions of NAT10 rely on RNA ac4C writing

We observed that the RNA ac4C levels were significantly decreased upon Nat10 knockdown or KO in mouse HSPCs (Fig. 1f,k and Extended Data Fig. 1g,j,k), implying the potential involvement of ac4C in the oncogenic function of Nat10 in AML. In addition to RNA, NAT10 and its yeast homologue Kre33 have been reported to catalyse acetylation on histone and non-histone proteins, such as tubulin42–44. We found that silencing of NAT10 in human and mouse AML cells resulted in a noticeable decrease of RNA acetylation (Fig. 3a–c and Extended Data Fig. 3a), but no significant alteration of histone and non-histone proteins acetylation (Fig. 3d–f and Extended Data Fig. 3b–g). Conversely, ectopic expression of Flag-tagged NAT10 in Kasumi-1, which expresses a lower level of NAT10 compared with other human AML cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 3h), led to an elevation of cell growth and RNA ac4C levels without inducing significant changes of protein acetylation (Fig. 3g–l and Extended Data Fig. 3i). These findings imply that RNA, rather than protein, is the primary substrate of NAT10 in AML.

Fig. 3. NAT10 promotes AML in an RNA acetylation-dependent manner.

a, Dot blotting showing the reduction of RNA ac4C in MOLM13 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. b, LC–MS/MS showing the reduction of poly(A) RNA ac4C in MOLM13 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. c, Dot blotting showing the reduction of RNA ac4C in MonoMac6 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. d, Western blotting detecting protein acetylation on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 and MonoMac6 lysates using anti-pan-acetylation antibody. e, Western blot analysis of histone acetylation in AML cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. f, Dot blotting showing the protein pan-acetylation levels of AML cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. g, Schematic structures depicting RNA binding region (RNA helicase, green box) and N-acetyltransferase domain (blue box) within the human NAT10 protein and NAT10 variants used in this study. The red line indicates the inactive mutation of G641 with glycine (G) to glutamic acid (E) conversions. h, Western blotting showing the overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase mutant in Kasumi-1 stable lines. i, Dot blotting showing the changes of ac4C levels in Kasumi-1 stable lines with overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase. j, Western blot analysis of histone acetylation in Kasumi-1 stable lines with overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase. k, Western blot analysis of histone acetylation in Kasumi-1 stable lines with overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase. l, MTT assays showing the cell proliferation of Kasumi-1 stable lines with overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase. m, Colony numbers of MLL-AF9-transduced HSPCs from Nat10-cKO mice with overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase in methylcellulose medium. 4-OHT (1 μM) was added to induce Nat10 KO. n, Quantification of intracellular serine levels in Kasumi-1 stable lines with overexpression of NAT10-WT, NAT10-G641E or NAT10-Δhelicase. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates and two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in b, l and n. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in m.

Extended Data Fig. 3. The effects of NAT10 knockdown or overexpression in human and mouse AML cell lines.

(a) LC–MS/MS showing the changes of RNA ac4C modification levels (left) and RNA m6A modification levels (right) in the total RNA of MOLM13 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. (b) The histogram showing the levels of lysine acetylation in histones in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells on day 4 post-transduction of lentiviral shRNAs by LC–MS/MS. (c, d) Western blotting (c) and RT–qPCR (d) confirming the knockdown efficiency of Nat10 in C1498 cells on day 4 post-transduction of lentiviral shRNAs. (e) ac4C dot blotting of C1498 cells on day 4 after Nat10 knockdown. MB, methylene blue. (f) Dot blot analysis of protein acetylation level using anti-pan-acetylation (Pan-acetyl) antibody in C1498 cells on day 4 after Nat10 knockdown. (g) MTT assays showing the effects of Nat10 knockdown on cell proliferation of C1498 cells. Cells were seeded on day 4 post-transduction (denoted as day 0 in the growth curves in MTT). (h) Western blotting showing the level of NAT10 in multiple AML cell lines. (i) Co-IP and western blotting showing the acetylation of TUBULIN in Kasumi-1 stable lines transduced with NAT10-WT (WT), NAT10-G641E mutant (G641E) or NAT10-Δhelicase mutant (Δhelicase) lentiviruses. IP, immunoprecipitation. IB, immunoblotting. (j) The colony numbers of MLL-AF9-transduced mouse HSPCs with overexpression of NAT10-WT (WT), NAT10-G641E mutant (G641E) or NAT10-Δhelicase mutant (Δhelicase) in methylcellulose medium. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in b and j. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in a, d and g. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. Images in c, e, f, h and i were representative of three independent experiments.

To further investigate the RNA acetylation-dependent function of NAT10, we generated a catalytic dead G641E mutant of NAT10, as well as a helicase-truncation (Δhelicase) that lost RNA binding activity25. Unlike the wild-type (WT) NAT10 (NAT10-WT), these two mutants were unable to efficiently catalyse RNA acetylation and promote cell growth in Kasumi-1 (Fig. 3g–l and Extended Data Fig. 3i). Similarly, ectopic expression of NAT10-WT, rather than the G641E or Δhelicase mutant, promoted colony formation in MLL-AF9 transformed mouse HSPCs (Extended Data Fig. 3j), and could almost completely restore colony formation in Nat10-cKO mouse HSPCs (Fig. 3m). Consistently, ectopic expression of NAT10-WT but not either mutant enforced the increase of serine metabolism (Fig. 3n). These findings strongly indicate that NAT10 promotes the metabolism and growth of AML cells through its RNA binding and acetyltransferase activity.

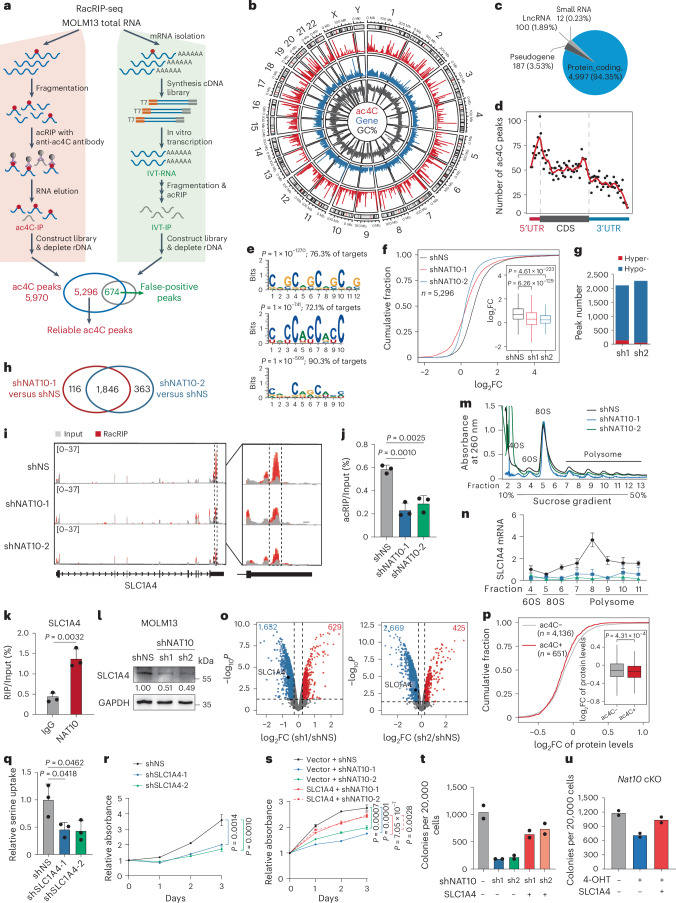

NAT10 mediates ac4C on SLC1A4 to facilitate serine uptake

To understand the mechanisms underlying the function of NAT10 as the RNA ac4C writer in AML, we profiled transcriptomic ac4C in MOLM13 cells using refined acetylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (RacRIP-seq), which includes a systematic calibration to eliminate the false positive signals using an in vitro-transcribed modification-free control library45 (referred to as IVT control) (Fig. 4a). The RacRIP-seq was robust and reproducible, showing high enrichment efficiency for MOLM13-IP but not IVT-IP, and a high correlation (Pearson’s correlation, cor ≥ 0.99, P < 0.001) between replicates (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). The RacRIP-seq yielded 5,296 reliable ac4C peaks (88.7%) that were identified from MOLM13 but absent in the IVT control (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 4d). Consistent with previous studies, most of the ac4C peaks are located in protein-coding transcripts and are highly enriched near the translation initiation sites and within coding sequences (CDS) (Fig. 4b–d and Extended Data Fig. 4e). HOMER motif analysis revealed that cytidine (C)-rich consensus sequences CXG, CXC and CXX (X indicates A, U, C and G) were significantly enriched (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4. NAT10 regulates serine uptake via ac4C modification on SLC1A4 mRNA.

a, Experimental scheme of RacRIP-seq. b, Circus plot showing the distribution of ac4C peaks (red), protein-coding genes (blue) and GC content (black) on the genome. c, The percentages of various RNA species identified by RacRIP-seq. d, The metagene profiles of ac4C peaks across mRNA transcripts. e, Top consensus sequences of ac4C peaks determined by HOMER motif analysis. f, Cumulative curves and box plots (insert) of ac4C log2 fold change (FC) showing global reduction of ac4C modification in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells. Box plot, centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. g, Histogram showing the numbers of hyper- or hypo- ac4C peaks in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells. h, Venn Diagram showing the intersection of hypo-ac4C peaks in MOLM13 cells transduced with different shRNAs against NAT10. i, IGV tracks showing ac4C peak distribution in SLC1A4 mRNA (left). High-confidence ac4C sites were marked in dashed area and was enlarged on right. The y axis represents counts per million (CPM). j, Gene-specific acRIP–qPCR detecting SLC1A4 ac4C levels in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells. k, RIP–qPCR showing the direct binding of endogenous NAT10 on SLC1A4 mRNA around ac4C site. l, Western blotting showing SLC1A4 protein levels in MOLM13 cells after NAT10 knockdown. m,n, Polysome profiling showing ribosome occupancy on SLC1A4 mRNA in MOLM13 cells. UV absorbance at 260 nm of sucrose density gradient fractions from cell lysates is shown (m). Total RNAs in different fractions were extracted and subjected to qPCR analysis. The levels of SLC1A4 in each fraction was normalized to input (n). o, Volcano plots showing differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in MOLM13 cells after NAT10 knockdown. Red, significant upregulated proteins (fold change >1.2, P < 0.05); blue, significant downregulated proteins (fold change <0.83, P < 0.05). p, Cumulative curves and box plot (insert) showing global changes of protein levels for ac4C− and ac4C+ transcripts in MOLM13 cells after NAT10 knockdown. Box plot, centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. q, Serine uptake levels in SLC1A4 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells. r, MTT assay showing the effects of SLC1A4 knockdown on MOLM13 cell proliferation. s, MTT assay in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells with or without SLC1A4 overexpression. t, CFA assay in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells with or without SLC1A4 overexpression. u, CFA assay using c-Kit+ BM cells from Nat10-cKO mice transduced with MLL-AF9 retrovirus plus pCL20C (vector) or pCL20C-SLC1A4 lentiviruses. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates and two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in j, k, n, q, r and s. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in t and u. A one-sided hypergeometric test was used in e. A two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test was used in f and p. Protein-wise linear models combined with empirical Bayes statistics were used in o.

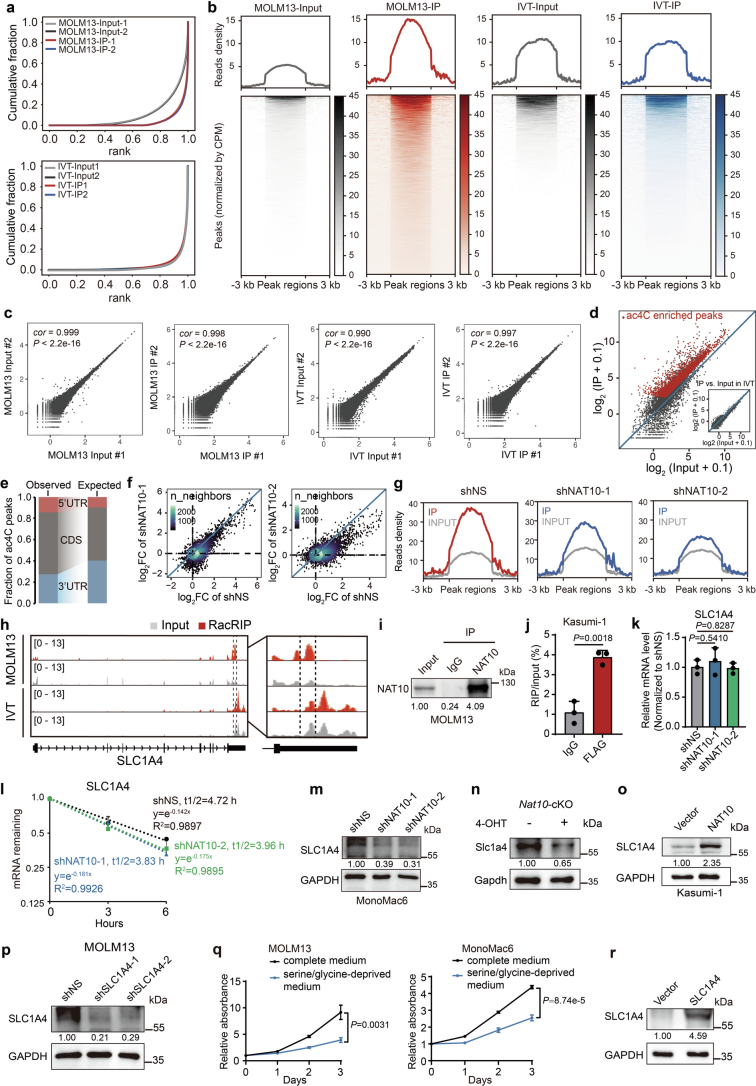

Extended Data Fig. 4. Transcriptome-wide mapping of ac4C reveals SLC1A4 as a direct target of NAT10.

(a) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plot depicting the enrichment of ac4C signals in MOLM13 and IVT libraries. (b) The densities of ac4C signals in MOLM13 and IVT libraries. Regions with ac4C enrichment were sorted in descending order based on the mean value per region. (c) Correlation analysis of replicate libraries in RacRIP-seq. cor, Pearson's correlation coefficient. (d) Scatter plot showing high enrichment efficiency of reliable ac4C peaks (red) in MOLM13-IP but not IVT-IP. (e) The percentages of ac4C peaks within CDS or UTRs in the acetylated transcripts (observed) compared to the expected percentages based on the length of each region (expected). (f) Fold changes of ac4C peaks (IP/input) in NAT10 knockdown (sh1 or sh2) versus control (shNS) MOLM13 cells. (g) Enriched signals of ac4C modification in control (shNS) and NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells (sh1 and sh2). (h) IGV tracks showing the distribution of ac4C peaks in the full-length SLC1A4 mRNA transcript identified by RacRIP-seq in MOLM13 cells and IVT control (left). The region between two dashed lines depicted high-confidence ac4C region for acRIP–qPCR validation. The enlarged view around this region was shown (right). Y axis represents CPM (counts per million). (i) Western blotting showing that the endogenous NAT10 was effectively enriched in MOLM13 cells in the RIP assay. IP, immunoprecipitation. (j) The direct binding of NAT10 on SLC1A4 mRNA around high-confidence ac4C site was confirmed by RIP-qPCR assays using FLAG antibody in Kasumi-1 stable lines with ectopically expressed FLAG-NAT10. (k) The relative mRNA expression of SLC1A4 in MOLM13 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. (l) RNA stability assay showing the mRNA half-life (t1/2) of SLC1A4 in MOLM13 cells transduced with NAT10 shRNAs or shNS. Cells were treated with actinomycin D on day 4 after knockdown of NAT10. (m) Western blotting showing the decrease of SLC1A4 expression on day 4 after knockdown of NAT10 in MonoMac6 cells. (n) Western blotting showing the decrease of Slc1a4 expression in c-Kit+ BM cells from Nat10fl/flCreERT2 (cKO) mice treated with 4-OHT (1 μM) as compared to those treated with vehicle. Cells were collected from the 1st passage of CFA. (o) Western blotting showing the increase of SLC1A4 expression in Kasumi-1 stable lines with ectopic expression of SLC1A4. (p) Western blotting showing the knockdown efficiency of SLC1A4 in MOLM13 cells on day 4 post-transduction of lentiviral shRNAs. (q) MTT assays showing the growth of MOLM13 cells (left) and MonoMac6 cells (right) cultured in complete or serine/glycine-deprived medium. (r) Western blotting showing the overexpression of SLC1A4 in MOLM13 stable lines. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in j, k, l and q. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in j, k and q. Images in i, m, n, o, p and r were representative of three independent experiments.

Subsequently, we applied RacRIP-seq in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells to characterize NAT10 targets. A global reduction of ac4C was observed (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 4f,g) and 1,846 hypo-acetylated peaks were identified upon NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 4g,h). Among them, we noticed that ac4C on the mRNA of serine transporter SLC1A4 declined dramatically after NAT10 silencing (Fig. 4i and Extended Data Fig. 4h), which was validated by acRIP–qPCR (Fig. 4j). Furthermore, the direct binding of NAT10 to SLC1A4 mRNA was also confirmed by RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) (Fig. 4k and Extended Data Fig. 4i,j). These results together indicate that NAT10 mediates ac4C modification on SLC1A4 mRNA.

ac4C has been reported to increase mRNA stability and/or translation25,30,46,47. RT–qPCR and mRNA stability assay suggested that both the RNA levels and stability of SLC1A4 remain unchanged upon NAT10 knockdown (Extended Data Fig. 4k,l). However, western blotting showed that SLC1A4 protein levels were substantially decreased upon knockdown or KO of NAT10 (Fig. 4l and Extended Data Fig. 4m,n) and were increased when NAT10 was overexpressed (Extended Data Fig. 4o). Furthermore, we conducted ribosome profiling and found that NAT10 knockdown significantly decreased the relative levels of SLC1A4 in the 60S and 80S ribosomes, and particularly in polysome (Fig. 4m,n), indicating an inhibition of SLC1A4 mRNA translation upon NAT10 knockdown. To gain a more comprehensive view on the regulation of protein expression by NAT10, we performed tandem mass tag (TMT) quantitative proteomics, and observed a global decrease of protein abundance (including that of SLC1A4) upon NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 (Fig. 4o and Supplementary Table 2). Notably, mRNAs with ac4C exhibited a significantly greater decrease of protein levels than mRNAs without ac4C (Fig. 4p), suggesting that NAT10-mediated ac4C has a profound effect on mRNA translation.

SLC1A4 plays a crucial role as serine transporter in various pathobiological processes, including tumourigenesis48–50. However, its involvement in AML is not well understood. We found that knockdown of SLC1A4 resulted in a significant inhibition of serine uptake and AML cell growth (Fig. 4q,r and Extended Data Fig. 4p), similar to the effect of serine deprivation from culture medium (Extended Data Fig. 4q). Moreover, the inhibition of AML cell growth and colony formation by NAT10 knockdown could be partially reversed by introducing SLC1A4 (Fig. 4s,t and Extended Data Fig. 4r). Notably, ectopic expression of SLC1A4 restored colony-formation ability in NAT10-KO mouse HSPCs (Fig. 4u). Collectively, these data reveal SLC1A4 as a functionally essential RNA target of NAT10 in AML.

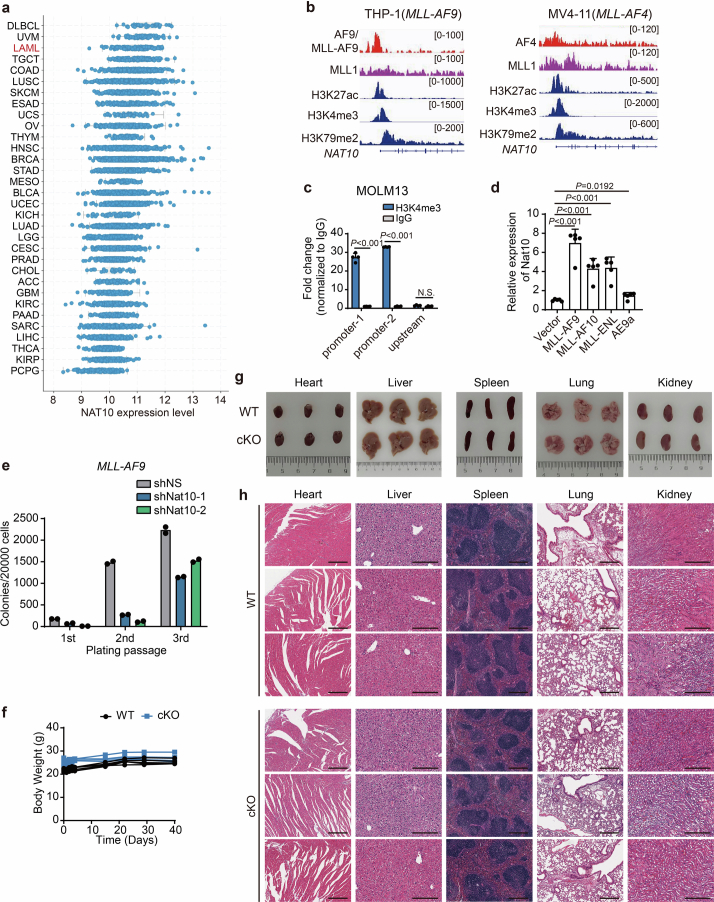

NAT10 activates serine biosynthesis via ac4C-HOXA9/MENIN-SSP

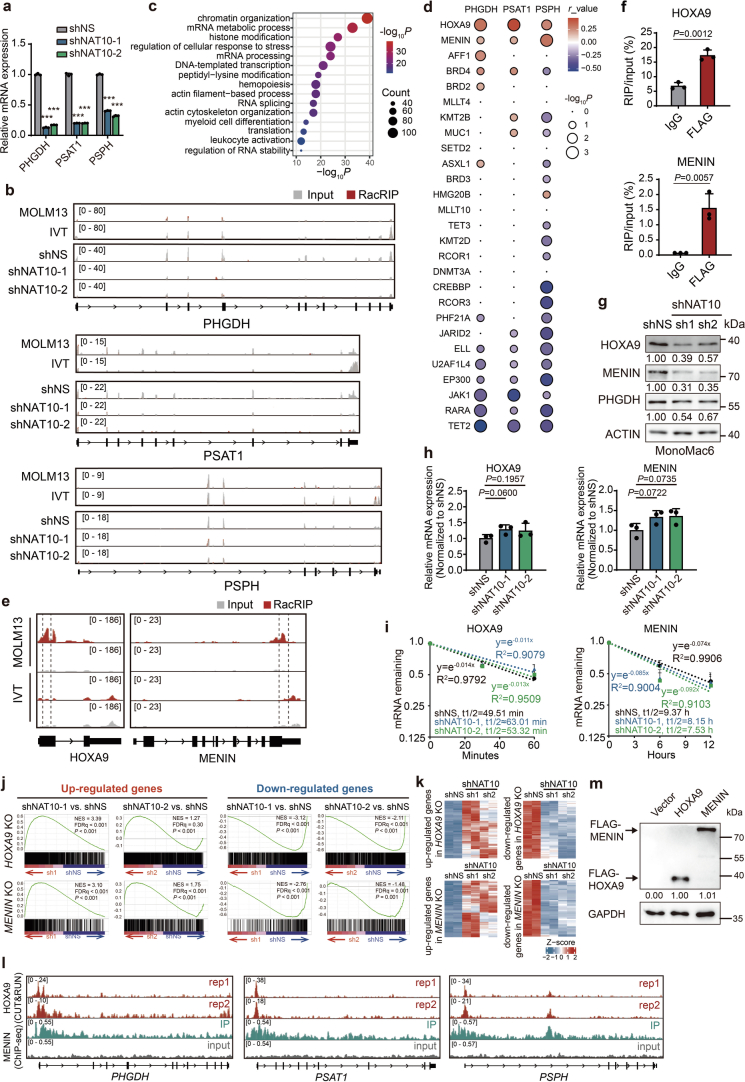

Metabolic analyses suggest that NAT10 has a profound impact on serine biosynthesis, in addition to serine uptake (Fig. 2h,i). While the expression of SSP genes (for example, PHGDH, PSAT1 and PSPH) was significantly reduced following NAT10 knockdown (Extended Data Fig. 5a), no apparent ac4C modification was found on their transcripts (Extended Data Fig. 5b), indicating that they may not be direct targets of NAT10. To elucidate the underlying mechanism, we conducted a thorough analysis of the RacRIP-seq data. Functional annotation indicates that the hypo-acetylated mRNAs were mainly associated with transcription regulation and haematopoietic differentiation (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 5c), including a subset of transcription factors and histone/DNA modification regulators that are crucial in AML51–56 (Fig. 5b). Among them, the transcription factor HOXA9 and the H3K4me3 reader MENIN (encoded by MEN1) were identified as the top two candidates whose expression levels positively correlated with that of SSP genes in AML (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 5d), suggesting they may involve in regulating transcription of SSP genes and metabolic reprogramming as potential targets of NAT10.

Extended Data Fig. 5. NAT10 activates SSP genes transcription through HOXA9/MENIN.

(a) RT–qPCR showing the decrease of PHGDH, PSAT1 and PSPH mRNA levels in MOLM13 cells on day 4 after knockdown of NAT10. ***, P < 0.001. The exact P values were shown in Source Data. (b) IGV tracks showing no obvious ac4C peak distribution across PHGDH, PSAT1 or PSPH transcripts. Y axis represents CPM (counts per million). (c) The enriched GO pathways of hypo-acetylated transcripts after NAT10 knockdown in MOLM13 cells. (d) Bubble plot showing the expression correlations between NAT10 candidate targets and SSP genes in AML (GSE30285 and GSE34184). The colour and size of bubbles represent the direction/strength and significance of expression correlation between NAT10 target genes and the SSP genes. r_value, Pearson’s correlation coefficient. (e) IGV tracks showing the distribution of ac4C peaks in HOXA9 and MENIN mRNA transcripts identified by RacRIP-seq in MOLM13 cells and IVT control. The regions between two dashed lines depicted high-confidence ac4C regions for acRIP–qPCR validation. Y axis represents CPM (counts per million). (f) The direct binding of NAT10 on HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs around high-confidence ac4C sites were confirmed by RIP-qPCR assays using FLAG antibody in Kasumi-1 stable lines with ectopically expressed FLAG-NAT10. (g) Western blotting showing the decrease of HOXA9, MENIN and PHGDH expression on day 4 after knockdown of NAT10 in MonoMac6 cells. (h) The mRNA expressions of HOXA9 and MENIN in MOLM13 cells on day 4 after NAT10 knockdown. (i) RNA stability assay showing the mRNA half-life (t1/2) of HOXA9 and MENIN in MOLM13 cells transduced with NAT10 shRNAs or shNS. Cells were treated with actinomycin D on day 4 after knockdown of NAT10. (j) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showing the upregulated and downregulated target genes of HOXA9 and MENIN were also differentially expressed upon NAT10 knockdown. NES, normalized enrichment score. FDR, False Discovery Rate. (k) Heatmaps showing expression profiling of HOXA9 or MENIN target genes in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells. (l) IGV tracks showing the distribution of HOXA9 or MENIN binding sites on the promoters of PHGDH, PSAT1 and PSPH identified by CUT&RUN (GSE221701) or ChIP-seq (GSE168461) in MOLM13 cells, respectively. (m) Western blotting showing the overexpression of FLAG-tagged HOXA9 or MENIN in MOLM13 stable lines. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in a, f, h and i. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in a, f and h. Images in g and m were representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. 5. NAT10 promotes SSP genes transcription and serine biosynthesis through HOXA9/MENIN.

a, Heatmap of hypo-acetylation genes related to transcription regulation and haematopoietic differentiation in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells. b, The interactome of NAT10 targets that are essential for leukaemia transcriptional regulation. The colour of circles represents the expression correlation between NAT10 targets and SSP genes. c, IGV tracks showing ac4C peak distribution in HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs. High-confidence ac4C sites were marked in dashed area. The y axis represents CPM. d, acRIP–qPCR detecting ac4C levels of HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells. e, RIP–qPCR assays showing the binding of endogenous NAT10 on HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs. f–h, Western blotting detecting NAT10 targets in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells (f), in c-Kit+ BM cells from Nat10-cKO mice (g) and in Kasumi-1 stable lines with NAT10 overexpression (h). i, Polysome profiling showing ribosome occupancy on HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs in MOLM13 cells. j, Commonly enriched GO terms of the downregulated DEGs in NAT10 knockdown and HOXA9-KO/MENIN-KO MOLM13 cells. k, Heatmap showing the expression levels of genes involved in serine metabolism in NAT10 knockdown, HOXA9-KO/MENIN-KO MOLM13 cells. l,m, RT–qPCR (l) and western blotting (m) showing the decrease of mRNA and protein levels of PHGDH, PSAT1 and PSPH in MOLM13 upon HOXA9 or MENIN knockdown. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001. n, Quantification of serine biosynthesis levels in MOLM13 upon HOXA9 or MENIN knockdown. o,p, MTT assays (o) and CFA assays (p) in NAT10 knockdown or control MOLM13 cells with or without HOXA9 or MENIN overexpression. Precise P values are shown in Source Data. q,r, CFA (q) and LDA (r) using c-Kit+ BM cells from Nat10-cKO mice transduced with MLL-AF9 plus MSCV-PIG (vector), MSCV-HOXA9 or MSCV-MENIN retroviruses. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 4 biological replicates in o or n = 3 biological replicates in d, e, i, l and n. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in p and q. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in d, e, l, n and o. A two-sided chi-squared test was used in r.

As displayed in Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), HOXA9 and MENIN had high levels of ac4C peaks that decreased after NAT10 silencing (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 5e). The ac4C modification and the direct binding of NAT10 on HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs were confirmed through acRIP–qPCR and RIP–qPCR, respectively (Fig. 5d,e and Extended Data Fig. 5f). Similar to SLC1A4, knockdown or KO of NAT10 significantly decreased HOXA9 and MENIN protein levels without affecting their mRNA levels or stability (Fig. 5f,g and Extended Data Fig. 5g–i). Moreover, overexpression of NAT10 increased HOXA9 and MENIN proteins (Fig. 5h). Additionally, polysome fractionation assays revealed a significant decrease in the translation of HOXA9 and MENIN in NAT10-knockdown cells (Fig. 5i). These data demonstrate that NAT10 mediates ac4C deposition on HOXA9 and MENIN mRNAs to enhance their translation.

Transcriptome profiling analysis in HOXA9 and MENIN-KO cells showed that the downstream targets of HOXA9 and MENIN were also differentially expressed in NAT10 knockdown cells (Extended Data Fig. 5j,k). Specifically, genes related to serine biosynthesis, such as PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH, CBS and CTH, were commonly downregulated upon depletion of HOXA9, MENIN and NAT10 (Fig. 5j,k). Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and Cleavage Under Targets & Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) results showed that HOXA9 and MENIN bound to the promoters of PHGDH, PSAT1 and PSPH (Extended Data Fig. 5l), suggesting a direct regulatory role of HOXA9 and MENIN in the expression of SSP genes. Indeed, knockdown of HOXA9 or MENIN significantly reduced the expression of SSP genes (Fig. 5l,m) and hindered serine synthesis (Fig. 5n). By modulating HOXA9 and MENIN expression, knockdown or KO of NAT10 markedly decreased the expression of SSP genes (Fig. 5f,g and Extended Data Fig. 5g), whereas overexpression of NAT10 displays the opposite effects (Fig. 5h).

In addition, overexpression of HOXA9 or MENIN was able to rescue cell growth and colony-forming ability in NAT10 knockdown MOLM13 cells (Fig. 5o,p and Extended Data Fig. 5m). Notably, ectopic expression of HOXA9 or MENIN restored colony-formation ability and stemness in Nat10-KO mouse HSPCs (Fig. 5q,r), indicating that HOXA9 and MENIN are functionally essential targets of NAT10 in mediating AML stemness. Collectively, NAT10 promotes serine biosynthesis and growth of AML cells through HOXA9/MENIN-mediated transcriptional regulation of SSP genes.

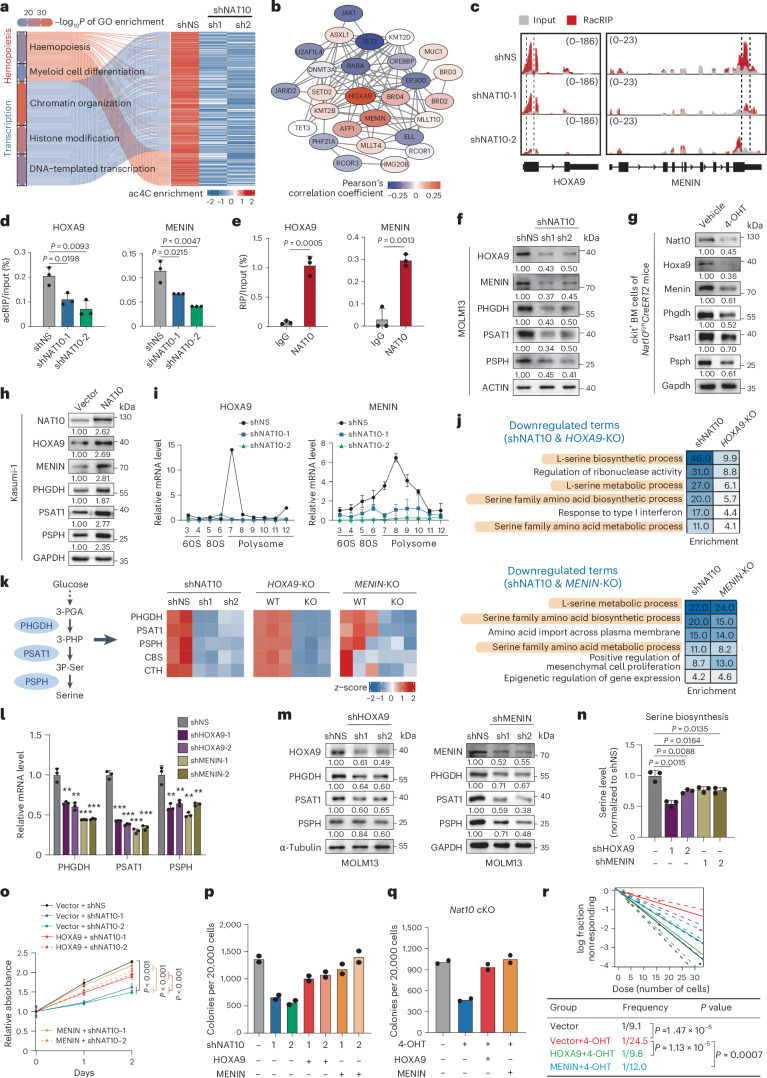

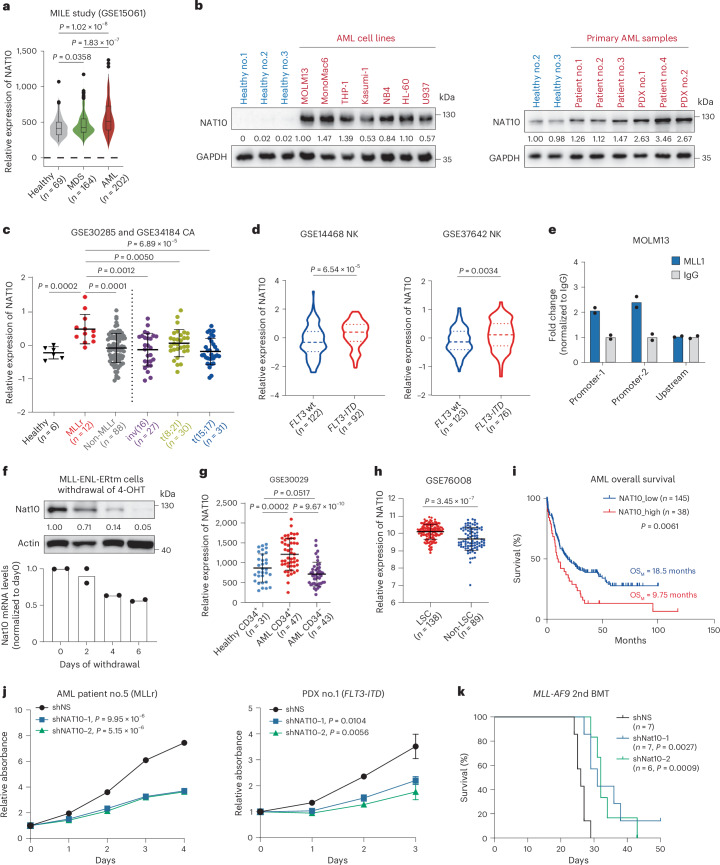

Aberrant high expression of NAT10 in AML, especially in LSCs

According to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data, NAT10 is highly expressed in haematopoietic malignancies, such as AML (Extended Data Fig. 6a). By analysing data from the Microarray Innovations in Leukaemia (MILE) study, we observed that NAT10 was expressed at a higher level in primary BM mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) of patients with AML compared with those of healthy controls and patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (Fig. 6a). By immunoblotting, we confirmed the upregulation of NAT10 protein in all the tested human leukaemia cell lines and primary AML samples relative to the healthy controls (Fig. 6b). Further analysis revealed that NAT10 expression was significantly higher in t(11q23)/MLL-rearranged (MLLr) AML than in other subtypes of AML and healthy controls (P < 0.001; Fig. 6c) and also higher in FLT3-ITD mutated cases compared with those with WT FLT3 in cytogenetically normal AML (Fig. 6d).

Extended Data Fig. 6. NAT10 is highly expressed in MLL-rearranged AML.

(a) Expression of NAT10 in various types of cancer as adopted from cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org/). (b) IGV tracks of ChIP-seq data (GSE79899) obtained from THP-1 and MV4-11 cells at the promoter region of NAT10 gene. (c) CUT&RUN assays showing histone modification H3K4me3 on NAT10 promoter. Two predicted binding sites within NAT10 promoter were analysed, while an upstream site served as a negative control. (d) RT–qPCR showing the expression of Nat10 mRNA in c-Kit+ BM cells of C57BL/6 mice transduced with MSCVneo empty vector or various oncofusion genes. Cells were collected from the 1st passage of CFA. AE9a, AML1-ETO9a. (e) CFA using BM cells from MLL-AF9 induced leukaemia mice transduced with shRNAs targeting Nat10 or negative control (shNS). (f) Body weights of all the mice from both Nat10-WT and Nat10-cKO groups were monitored and shown. n = 5 in each group. (g) Representative images of several major organs, including heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney, dissected from Nat10-WT and Nat10-cKO mice at the experimental end point. (h) Representative images of HE staining of heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney from Nat10-WT and Nat10-cKO groups. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 4 biological replicates in c, or n = 5 biological replicates in d. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in e. The exact P values in c and d were shown in Source Data.

Fig. 6. NAT10 is highly expressed in AML and represents a therapeutic target.

a, NAT10 expression levels in BM-MNCs from primary MDS and patients with AML and healthy donors in the MILE study. Centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range; points, outliers. b, Western blotting showing NAT10 protein levels in PBMCs from healthy control, human leukaemia cell lines and BM-MNCs from patients with AML. c, Microarray data showing NAT10 expression levels in patients with primary AML with chromosomal translocations and healthy donors. Values are mean ± s.d. MLLr, MLL-rearrangement. d, NAT10 expression levels in patients with normal-karyotype (NK) AML with WT FLT3 or FLT3-ITD mutation. Centre line, median; upper and lower lines, third and first quartiles. e, CUT&RUN assays showing the direct binding of MLL1/MLL1-fusion on NAT10 promoter. The upstream site served as a negative control. f, Western blotting (top) and RT–qPCR (bottom) showing a gradual decrease of Nat10 protein and mRNA levels in MLL-ENL-ERtm cells after 4-OHT withdrawal. g, NAT10 expression levels in CD34+ fractions from BM of healthy donors or patients with AML, as well as in CD34− fractions of BM from patients with AML. Values are mean ± s.d. h, NAT10 expression levels in functionally validated LSC and non-LSC fractions sorted from patients with primary AML. Values are mean ± s.d. i, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of patients with AML based on their NAT10 expression levels from TCGA. OSM, medium overall survival. j, MTT assays showing the effects of NAT10 knockdown on cell proliferation of primary BM-MNC from a patient with MLL-rearranged AML (patient 5) and PDX cells harbouring FLT3-ITD mutation (PDX 1). k, Kaplan–Meier curves showing the effects of Nat10 knockdown on the maintenance/progression of MLL-AF9-induced AML in secondary BMT recipient mice. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in e and f. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates and two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in j. Log-rank tests were used in i and k. A two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test was used in a, c, d, g and h. Images in b are representative of three technical replicates.

MLL-fusion proteins promote the transcription of target genes by binding to their promoters and modulating histone modifications57,58. To uncover the mechanisms underlying the increased expression of NAT10 in MLL-rearranged AML, we analysed published ChIP-seq data and found that MLL-AF9 and MLL-AF4 directly bind to the promoter of NAT10 (Extended Data Fig. 6b), which was validated through CUT&RUN in MOLM13 cells (Fig. 6e). Furthermore, the epigenetic signature of MLL-fusion target genes (H3K79me2, H3K27ac and H3K4me3) were observed in the vicinity of MLL-fusion binding sites in NAT10 promoter (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). In addition, overexpression of MLL-fusion proteins in mouse HSPCs resulted in a substantial increase in Nat10 expression (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Consistently, the expression of Nat10 was sustained by 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)-induced MLL-ENL in the murine leukaemic cell line MLL-ENL-ERtm, and gradually decreased upon 4-OHT withdrawal (Fig. 6f). Collectively, these results demonstrate that NAT10 is transcriptionally upregulated by MLL fusions in MLLr AML.

Of note, a significantly higher level of NAT10 was observed in CD34+ immature AML cells compared with CD34− bulk AML cells and CD34+ cells from healthy controls (Fig. 6g). Consistently, functionally defined LSCs also exhibited a higher level of NAT10 than non-LSCs based on the GSE76008 dataset59 (Fig. 6h). In line with the enrichment of NAT10 in LSCs/LICs, high expression of NAT10 is associated with poor survival in patients with AML (Fig. 6i).

NAT10 represents a promising therapeutic target for AML

The above findings that NAT10 is upregulated in AML and critical for maintaining the survival and stemness of AML cells prompted us to evaluate the therapeutic potential of NAT10 in AML. Consistent with the results from cell lines, knockdown of NAT10 also remarkably repressed cell growth in primary human leukaemia cells harbouring an MLL fusion or patient-derived xenograft (PDX) cells with an FLT3-ITD mutation (Fig. 6j) and inhibited colony formation of blast cells from MLL-AF9 leukaemia mice (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Furthermore, secondary BM transplant (BMT) experiments showed that silencing of NAT10 significantly prolonged overall survival of recipient mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 6k). On the other hand, tamoxifen-induced deletion of Nat10 in Nat10-cKO adult mice did not result in acute death or body weight loss for over 40 days of monitoring and had little impact on the morphology and histopathology of major organs (Extended Data Fig. 6f–h), suggesting that NAT10 is a promising and safe therapeutic target for AML.

Pharmacological targeting of NAT10 potently suppresses AML

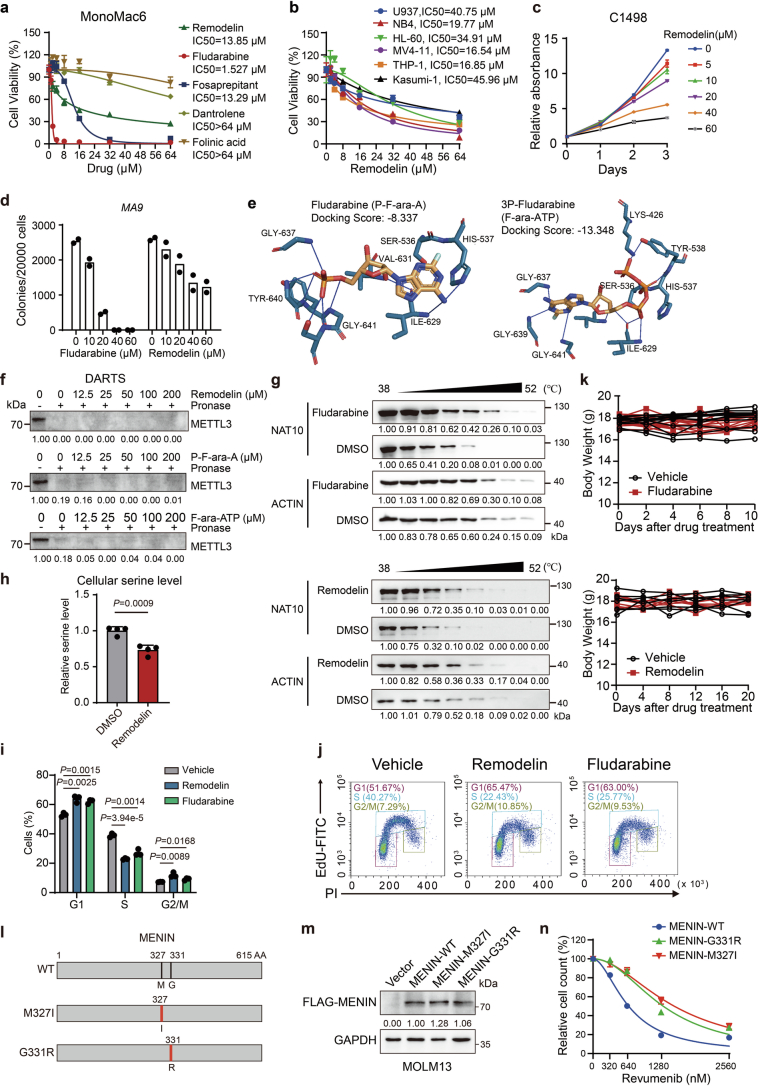

We subsequently evaluated the anti-leukaemia effects of NAT10 inhibitors. In addition to the well-known NAT10 inhibitor Remodelin60, several US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs, including fosaprepitant, folinic acid, fludarabine and dantrolene, were also tested because of their higher binding potency to NAT10 than Remodelin and acetyl coenzyme A (Ac-CoA)61. Treating MOLM13 and MonoMac6 cells with fludarabine, fosaprepitant and Remodelin remarkably inhibited cell growth with a half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) ranging from 1.5 to 18.5 μM, whereas folinic acid and dantrolene treatment showed marginal effects (Fig. 7a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). Fludarabine and Remodelin can also effectively inhibit the growth of many other AML cell lines (Fig. 7b and Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). Notably, the IC50 of fludarabine in AML cell lines and primary patient cells was much lower than that in primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors (Fig. 7b,c). In addition, treating leukaemia blast cells from MLL-AF9 leukaemia mice with fludarabine or Remodelin suppressed colony formation in a concentration-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Such data demonstrate that fludarabine and Remodelin exhibit promising anti-leukaemia effects in vitro.

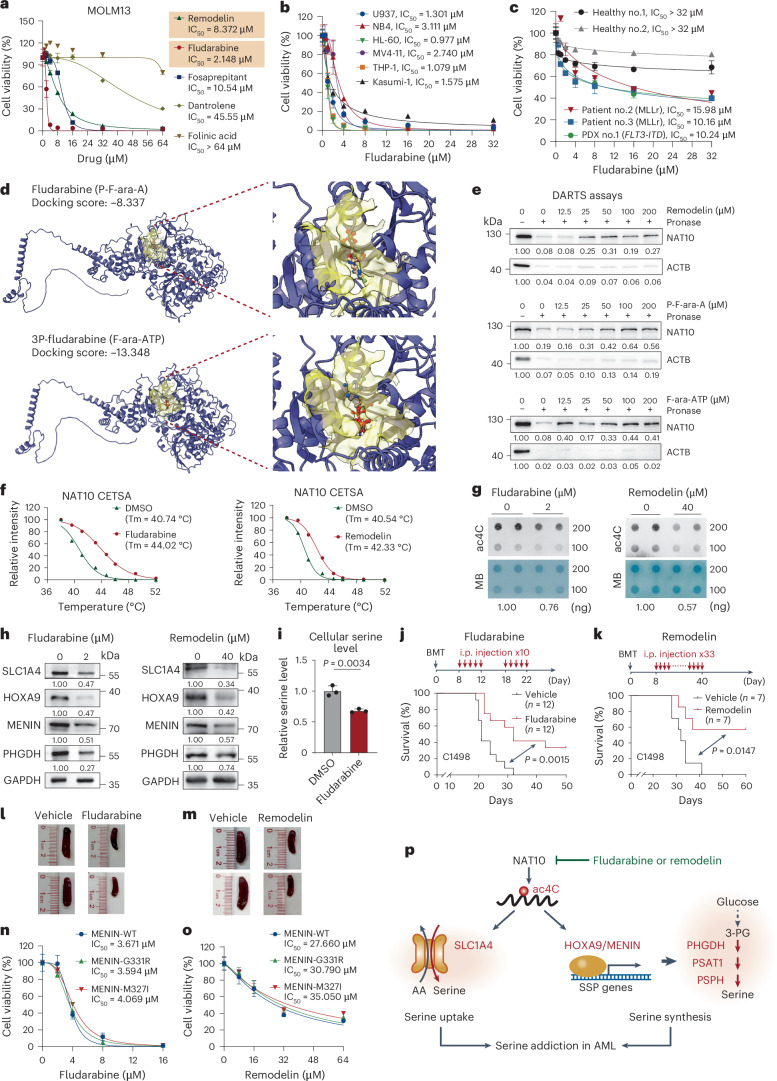

Fig. 7. Inhibition of NAT10 by Remodelin or fludarabine exhibits anti-leukaemia potency in vitro and in vivo.

a, MTT assays and the IC50 values of Remodelin, fludarabine, fosaprepitant, dantrolene and folinic acid in MOLM13 cells after 72 h of treatment. b, MTT assays showing the inhibitory effects of fludarabine in leukaemia cell lines with a 72-h treatment. IC50 in each cell line was shown. c, MTT assays showing the inhibitory effects of fludarabine in PBMCs from healthy donors, primary BM-MNCs from patients with AML or PDX cells with a 72-h treatment. d, Molecular docking of NAT10 with fludarabine (P-F-ara-A) and 3P-fludarabine (F-ara-ATP). e, DARTS assays evaluating the efficacy of Remodelin, P-F-ara-A and F-ara-ATP on protecting NAT10 protein against pronase digestion in MOLM13 cell lysates. f, Thermal shift curves of NAT10 from CETSA assays in MonoMac6 pretreated with fludarabine (F-ara-A), Remodelin or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Tm, thermal melting temperature. g, Dot blotting showing the reduction of RNA ac4C in MOLM13 cells with fludarabine or Remodelin treatment. MB staining served as RNA loading control. h, Western blotting showing the protein levels of NAT10 targets and downstream genes in MOLM13 cells with fludarabine or Remodelin treatment. i, Total cellular serine levels in MOLM13 cells treated with or without fludarabine. j,k, Kaplan–Meier survival curves of mice transplanted with C1498 cells and treated with fludarabine (j), Remodelin (k) or vehicle control. Days of BMT and drug treatment are shown in j and k (top). n = 12 in each group in j and n = 7 in each group in k. i.p., intraperitoneal. l, Representative images of spleens from j. m, Representative images of spleens from k. n,o, MTT assays showing the inhibition effects of fludarabine (n) and Remodelin (o) in MOLM13 cells transduced with WT or mutated MENIN. p, Proposed model depicting the function and mechanism of NAT10 in AML pathogenesis. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in a–c, i, n and o. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used in i. Log-rank tests were used in j and k.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Targeting NAT10 by small molecule inhibitors suppresses AML cells both in vitro and in vivo.

(a) MTT assays and the IC50 values of Remodelin, fludarabine, Fosaprepitant, Dantrolene and Folinic acid in MonoMac6 cells after 72 hours of treatment. (b) MTT assays showing the inhibitory effects of Remodelin in leukaemia cell lines with 72-hour treatment. IC50 in each cell line was shown. (c) MTT assays showing the inhibitory effects of Remodelin in C1498 cells. (d) Effect of fludarabine and Remodelin on the colony-forming capacity of blast cells from MLL-AF9-induced leukaemia mice. (e) Predicted binding modes of fludarabine (P-F-ara-A) and 3P-fludarabine (F-ara-ATP) to the enzymatic pocket of the NAT10 protein. (f) DARTS assays evaluating the efficacy of Remodelin, P-F-ara-A and F-ara-ATP on protecting METTL3 protein against pronase digestion in MOLM13 cell lysates. (g) Western blotting of NAT10 protein from CETSA assays in MonoMac6 pretreated with fludarabine (F-ara-A), Remodelin or DMSO. (h) Total cellular serine level in MOLM13 cells treated with or without Remodelin at 10 μM for 96 hours. (i) Histogram showing the cell proportions in different phases of MOLM13 cells treated with Remodelin (20 μM) or fludarabine (1 μM) for 72 hours. (j) An example showing the EdU labelling and PI staining followed by flow cytometry to assess cell cycle of MOLM13 cells. (k) Body weight of C1498 syngeneic AML mice after i.p. injection of fludarabine (200 mg/kg), Remodelin (30 mg/kg) or corresponding vehicle control. (l) Schematic structures depicting human wild-type MENIN protein and MENIN variants used in this study. The red lines indicated the mutation of M327 with methionine (M) to isoleucine (I) conversion in the M327I variant or the mutation of G331 with glycine (G) to arginine (R) conversion in the G331R variant, respectively. (m) Western blotting showing the overexpression of FLAG-tagged wild-type or mutant MENIN in stably transduced MOLM13 cells (n) The inhibition curves of MOLM13 cells transduced with wild-type or mutant MENIN treated with Revumenib at indicated concentration for 12 days. Values are mean of n = 2 biological replicates in d. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in a, b, c, i and n or n = 4 biological replicates in h. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. Images in f, g and m were representative of three independent experiments.

Fludarabine (also known as P-F-ara-A) is a synthetic adenine nucleoside analogue that has been used for clinical treatment of lymphocytic and myeloid leukaemia36. As a prodrug, it is rapidly dephosphorylated by serum phosphatase to free F-ara-A, which is then transported into cells and converted to its 5′-triphosphate, F-ara-ATP, the principal active metabolite62. Molecular docking showed that both fludarabine and F-ara-ATP could interact with the Ac-CoA binding pocket of NAT10 with docking scores of −8.337 and −13.348, respectively (Fig. 7d and Extended Data Fig. 7e). The binding of fludarabine and F-ara-ATP with NAT10 were confirmed by drug affinity responsive target stability assay (DARTS) and cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA), with a comparable or better protective effect for NAT10 against protease-mediated degradation or high-temperature-induced denaturation compared with Remodelin (Fig. 7e,f and Extended Data Fig. 7f,g). Consequently, fludarabine significantly reduced cellular RNA ac4C levels, the expression of NAT10 targets and total serine levels, and induced G1/S phase arrest in AML cells, similar to what was observed for Remodelin (Fig. 7g–i, Extended Data Fig. 7h–j and Supplementary Fig. 1b). These results together indicate that fludarabine is an inhibitor of NAT10 and exhibits comparable or even more potent inhibitory effect than Remodelin in inhibiting NAT10.

To evaluate the in vivo therapeutic efficacy of fludarabine as well as Remodelin, we established a C1498 syngeneic AML model, followed by intraperitoneal injection of fludarabine (200 mg kg−1 ten times) or Remodelin (30 mg kg−1 for 33 times). Treatment with fludarabine or Remodelin significantly prolonged the overall survival of recipient mice and alleviated the symptoms of splenomegaly without significant body weight loss (Fig. 7j–m and Extended Data Fig. 7k). Together, such proof-of-concept data indicate that targeting NAT10 by small molecule inhibitors could effectively inhibit AML in vitro and in vivo.

MENIN inhibitors, such as revumenib (SNDX-5613), have emerged as promising therapies for MLLr or NPM1-mutant AML. However, patients often develop resistance to MENIN inhibitors due to somatic mutations of MENIN (for example, M327I or G331R) at the revumenib–MENIN interface63. Given the efficient reduction of MENIN by NAT10 inhibitor, we sought to explore the potential of NAT10 inhibitors in overcoming MENIN inhibitor resistance. Consistent with previous report63, MOLM13 cells stably expressing MENIN-M327I or MENIN-G331R mutants were insusceptible to revumenib treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7l–n). Notably, treatment with fludarabine or Remodelin remarkably inhibited cell growth in these revumenib-resistant cells, with similar IC50 values to those in revumenib-sensitive cells with WT MENIN (Fig. 7n,o), suggesting that targeting NAT10 represents a promising strategy for overcoming MENIN inhibitor resistance in AML.

Discussion

Although RNA modification represents an important post-transcriptional regulation mechanism in AML, the function and mechanism of RNA ac4C modification in leukaemia remain poorly understood. In this study, we uncover that ac4C and its writer NAT10 play a previously unappreciated role in promoting leukaemogenesis and maintaining the self-renewal of LSCs/LICs. Mechanistically, NAT10-mediated ac4C reprograms serine metabolism by simultaneously promoting the uptake and biosynthesis of serine (Fig. 7p). We also identify fludarabine as an inhibitor of NAT10 and show inhibiting NAT10 by fludarabine or Remodelin effectively suppresses leukaemia cells and overcomes MENIN inhibitor resistance. Thus, our findings offer insights into the epitranscriptomic mechanism of AML pathogenesis, shedding light for targeting NAT10 in AML treatment.

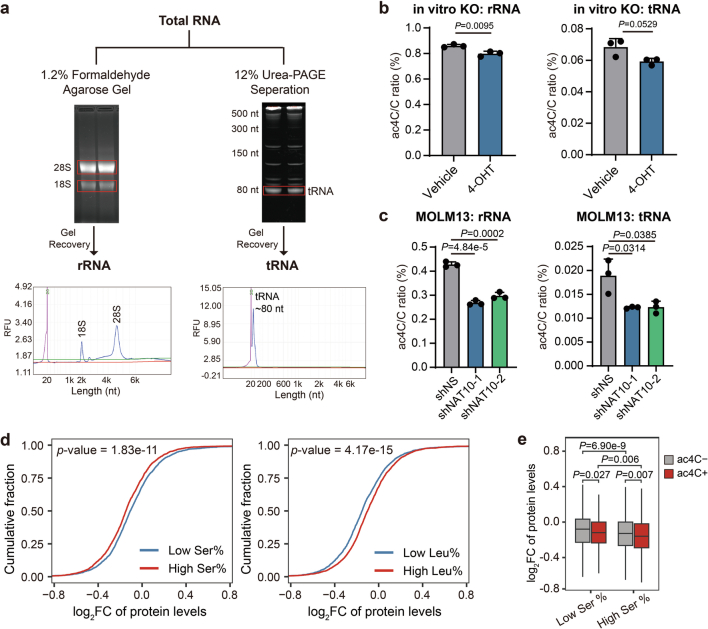

NAT10 has been reported to catalyse RNA ac4C modification on 18s rRNA, tRNA (tRNASer and tRNALeu) and mRNAs. Indeed, NAT10 KO/knockdown resulted in the reduction of ac4C levels in rRNAs and tRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c), although to a less extent compared with the decrease of ac4C in mRNAs (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 1j,k). ac4C in 18s rRNA is suggested to be involved in rRNA processing and ribosome biogenesis and may have a global impact on translation27,64, whereas ac4C in tRNASer and tRNALeu may function in maintaining decoding fidelity and translation efficiency of proteins65. Our proteomics data showed a global decrease of protein abundance upon NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 4o), suggesting that rRNA ac4C may play a role. However, mRNAs with ac4C exhibited a more profound decrease of protein levels than those without ac4C upon NAT10 knockdown (Fig. 4p), suggesting that ac4C on mRNA has a selective translation regulation effect on top of the global impact regulated by ac4C on rRNA. On the other hand, proteins with higher content of serine displayed more pronounced downregulation upon NAT10 knockdown, while the opposite trend was observed for leucine (Extended Data Fig. 8d), suggesting that serine levels, rather than tRNA ac4C modification, may contribute to the effect of NAT10 in regulating translation. Furthermore, we observed lower protein levels of mRNAs harbouring ac4C compared with those without ac4C upon NAT10 knockdown, regardless of the content of serine in their encoded proteins (Extended Data Fig. 8e), again highlighting the critical roles of mRNA ac4C on the translation regulatory function of NAT10.

Extended Data Fig. 8. The ac4C modification on mRNAs plays a dominant role in the effect of NAT10 on AML cells.

(a) Schematic showing the isolation of rRNA and tRNA from total RNA and the purity validation of each fraction. (b) The ac4C levels in rRNA and tRNA in Nat10-cKO BM cells upon 4-OHT induction (1 μM for 72h) were detected by LC–MS/MS. (c) The ac4C levels in rRNA and tRNA in NAT10 knockdown and control MOLM13 cells on day 4 post-transduction were detected by LC–MS/MS. (d) Cumulative curves showing global changes of protein levels for proteins with high (greater than or equal to 7.5%) or low (lower than 7.5%) serine levels (left), or proteins with high (greater than or equal to 9.5%) or low (lower than 9.5%) leucine levels (right) in NAT10 knockdown (average of shNAT10-1/sh1 and shNAT10-2/sh2) versus control (shNS) MOLM13 cells. (e) Box plots showing global changes of protein levels for ac4C- or ac4C+ mRNAs with high (greater than or equal to 7.5%) or low (lower than 7.5%) serine levels in their protein products in NAT10 knockdown (average level of shNAT10-1 and shNAT10-2) versus control (shNS) MOLM13 cells. Box plot, center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5 × interquartile range. Values are mean ± s.d. of n = 3 biological replicates in b and c. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used in b and c. Two-sided Mann–Whitney U-test was used in d and e.

Recently, serine has been identified as an important oncogenesis-supportive metabolite in leukaemia and several other cancer types17. Our multi-omics analyses reveal that NAT10-mediated ac4C has a profound impact on promoting serine metabolism. Mechanistically, NAT10 deposits ac4C modification on SLC1A4 mRNAs, enhancing its translation and leading to sustained serine import. On the other hand, NAT10 enhances the translation of HOXA9 and MENIN, boosting the transcription of SSP genes and serine biosynthesis. Therefore, our results uncover a previously unappreciated mechanism by which leukaemia cells (especially LSCs) with high NAT10 expression sustain high intracellular serine levels through activating both uptake and synthesis of serine in an ac4C-dependent mechanism. It has been shown that targeting serine metabolic vulnerability, either through inhibition of SSP or dietary restriction of serine or in combination, could effectively suppress AML cell survival and delay AML development13,15. Given the dual impacts of NAT10 on serine uptake and synthesis, targeting NAT10 may represent an approach to effectively impair serine metabolism and treat AML.

HOXA9 and MENIN have been identified as valuable therapeutic targets, holding substantial promise in the fight against AML. Our data also reveal HOXA9 and MENIN as upstream regulators of the serine biosynthesis pathway, adding additional evidence for the critical role of HOXA9 and MENIN in AML. Although MENIN inhibitors have been developed and shown to be effective in treating advanced acute leukaemia, HOXA9 was considered ‘undruggable’, and efforts have been devoted to reducing its expression or disrupting its interaction with its cofactor MEIS1. Our investigation has uncovered ac4C as an emerging regulatory mechanism for modulating the expression of HOXA9 and MENIN, thereby emphasizing that targeting ac4C could be an alternative approach to simultaneously disrupt the dependency of HOXA9 and MENIN in AML. On the other hand, therapy resistance to MENIN inhibitors occurred due to mutations in the MENIN protein. Our data showed that Remodelin or fludarabine treatment could suppress growth of AML cells with mutated MENIN (and therefore resistant to MENIN inhibitor treatment) to an extent similar to that on MENIN WT cells, suggesting an alternative strategy of overcoming MENIN inhibitor resistance that warrants further systematic studies.

Overall, our results demonstrate that NAT10 and ac4C play critical roles in reprogramming serine metabolism and promoting leukaemogenesis and stemness maintenance of LSCs. Our proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that treatment with NAT10 inhibitors can effectively suppress AML cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Nonetheless, further investigation of NAT10 as a clinical target is strongly warranted, with the aim of developing ac4C-based therapies for the clinical treatment of AML.

Methods

The research conducted in this study complies with all relevant ethical regulations. All procedures involving mice and experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC) (L025504202111015), Guangzhou Institute of Biomedicine and Health (GIBH), Chinese Academy of Sciences (2020066) and Ruiye Bio-tech Guangzhou Co. (RYEth-20221010411).The use of human specimens and informed consent were approved by the ethics board of the SYSUCC (G2023-108-01 and G2023-285-01) and Fujian Medical University Union Hospital in China (2021KJCX004).

Mice and animal housing

The Nat10 floxed mice (Nat10fl/fl) on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from GemPharmatech, R26-CreERT2 mice were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms Center and B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All laboratory mice were maintained in the animal facility at SYSUCC, GIBH, Chinese Academy of Sciences or Ruiye Bio-tech Guangzhou. All animal experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of SYSUCC, GIBH or Ruiye.

Mouse bone marrow transplantation

These assays were conducted as described previously20,40 with some modifications. For primary BMT, 0.2 × 106 donor cells from CFA assays and 1.0 × 106 radioprotective dose of whole bone marrow cells collected from B6.SJL (CD45.1) or C57BL/6 (CD45.2) mouse were transplanted into lethally (500 cGy twice, 86 cGy min−1) irradiated 7–9-week-old B6.SJL (CD45.1) or C57BL/6 (CD45.2) recipient mice via tail vein injection. For secondary BMT, 0.2 × 106 BM cells collected from primary leukaemic mice were injected into sublethally (450 cGy, 86 cGy min−1) irradiated 7–9-week-old B6.SJL (CD45.1) recipient mice via tail vein injection. For BMT using MLL-AF9 transduced c-Kit+ Nat10fl/flCreERT2 BM cells, 0.2 × 106 donor cells from CFA assays combined with 1.0 × 106 radioprotective dose of whole BM cells from a B6.SJL (CD45.1) were transplanted. Two weeks after transplantation, recipient mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen (75 mg kg−1, Sigma-Aldrich) every other day for five times to induce Nat10 KO. Engraftment cells were analysed by BD LSRFortessa X-20 and analysed using FlowJo v.10. When mice showed signs of systemic illness signs of immobility, a huddled posture, the inability to eat, ruffled fur or self-mutilation, the animals were killed immediately by CO2 inhalation or cervical dislocation. BM cells isolated from both tibia and femur were loaded for cytospin preparation. BM cytospin and blood smear slides were stained with Wright–Giemsa (Polysciences). Portions of the spleen and liver from leukaemic mice were collected, fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin before they were sectioned and stained with H&E.

C1498 syngeneic AML model

For the C1498 syngeneic AML model, 1.0 × 106 viable C1498 cells were transplanted into sublethally (300 cGy, 86 cGy min−1) irradiated 7–9-week-old C57BL/6 recipient mice via tail vein injection. One week after transplantation, recipient mice began receiving fludarabine phosphate (HY-B0028, MedChem Express) at dose of 200 mg kg−1 ten times (two rounds of consecutive 5 days with a 5-day interval) or Remodelin hydrobromide (S7641, Selleck) once per day at dose of 30 mg kg−1 for 33 times. When mice showed signs of systemic illness, they were killed immediately.

Plasmid construction

Human NAT10, SLC1A4, HOXA9 and MENIN coding sequence was reverse transcribed and PCR-amplified from MOLM13 total RNA and cloned into the pCL20C lentiviral vector (Addgene) or MSCV-PIG retroviral vector (Addgene) through the EcoRI enzymatic sites. NAT10 and MENIN mutant vectors were constructed using a Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs). shRNA vectors were constructed by synthesizing shRNA-encoded DNA oligonucleotides and cloning into the pLKO.1 vector (Addgene). Mature antisense sequences of shRNAs were listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Virus preparation and infection

These assays were conducted as described previously40,66 with some modifications. In brief, retroviruses or lentiviruses were produced in HEK293T cells by co-transfection of individual expression construct with the pCL-Eco packaging vector (IMGENEX) or the pMD2.G:pMDLg/pRRE:pRSV-Rev packaging mix (individually purchased from Addgene), respectively. One or two rounds of ‘spinoculation’ were performed to allow the infection of viruses. Resistance selection (1 μg ml−1 of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and/or 10 μg ml−1 blasticidin (InvivoGen)) began 48 h later. Cells infected with lentiviral shRNAs were sampled for analysis of RNA modifications, RNA/protein expression, cell metabolism and multi-omics (including RNA-seq, RacRIP-seq, metabolomics profiling and proteomics) on day 4 post-infection. The survival and apoptosis analysis were evaluated at later time points (day 4–8 for MTT, day 5 for apoptosis). As for gene overexpression, a stable cell line was obtained by at least three passages of antibiotic selection.

Isolation of HSPCs from mice bone marrow

BM cells were extracted from the tibia and femur of 5–7-week-old mice and resuspended in ammonium chloride solution (BL503B, Biosharp) for removing red blood cells. c-Kit+ cells were isolated using mouse CD117 microbeads together with OctoMACS Separator and Starting kits (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Induced deletion of Nat10 in vitro and in vivo

For in vitro deletion of Nat10 in BM cells from Nat10fl/flCreERT2 mice, 1 mM (Z)-4-OHT (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in ethanol (Macklin) was added to methylcellulose base medium (R&D Systems) at a final concentration of 1 µM. Cells were cultured for more than 5 days in methylcellulose medium before collection.

For in vivo deletion of Nat10, tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in corn oil (Macklin) at a concentration of 20 mg ml−1. Mice were injected with tamoxifen or vehicle intraperitoneally at a relatively low dose of 75 mg kg−1 body weight once a day for 5 consecutive days or as indicated. Ten days later, genotyping was performed and BM cells were collected for subsequent analysis. For mice undergoing survival analysis, the survival was monitored for 40 days and their body weight was measured repeatedly during this period. At the end point of the experiment, the mice were killed to collect organs (including heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) for H&E staining.

Colony-forming and replating assay

BM cells were collected from 5–7-week-old WT, Nat10+/+CreERT2 or Nat10fl/flCreERT2 mice. BM progenitor (HSPC, that is, c-Kit+) cells were enriched by the CD117 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) from BM cells. BM progenitor cells were co-transduced with retroviruses or lentiviruses as indicated through one or two rounds of ‘spinoculation’. The transduced cells were seeded into mouse methylcellulose medium (R&D Systems) supplemented with 10 ng ml−1 of recombinant interleukin (IL)-3, IL-6, GM-CSF and 50 ng ml−1 recombinant SCF (Sino Biological) along with 0.5 mg ml−1 of G418 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and/or 1.5 μg ml−1 of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 5–7 days. (Z)-4-OHT (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in ethanol was added to methylcellulose medium at a final concentration of 1 µM when necessary. For serial replating assay, colony cells were collected every 5–7 days and then replated in methylcellulose medium. Colony numbers were counted before each plating.

For CFA assays using human cell lines, MOLM13 cells transduced with lentivirus were seeded into MethoCult H4434 Classic medium (STEMCELL Technologies) with the addition of 1.5 μg ml−1 puromycin when necessary.

Limiting dilution assay

For in vivo LDAs, frozen BM cells collected from primary BMT mice (Nat10-cKO and Nat10-WT, two mice from each group whose survival is close to the median survival of the corresponding group) that developed leukaemia were thawed and equal numbers of cells from the same group were mixed and injected into sublethally (450 cGy, 86 cGy min−1) irradiated 8-week-old B6.SJL recipient mice through tail vein with four different doses (0.2 × 106, 0.02 × 106, 0.002 × 106 and 0.0002 × 106) of donor cells for each group. Six recipient mice were transplanted in each dose of each group. The number of recipient mice that developed leukaemia within 8 weeks post-transplantation was counted for each group. ELDA software67 was used to analyse the frequencies of LSCs/LICs.

For in vitro LDAs, HSPCs transduced with different combinations of retroviruses and/or lentiviruses were seeded into Mouse Methylcellulose Base Media (R&D Systems) supplied with 10 ng ml−1 recombinant IL-3, IL-6, GM-CSF and 50 ng ml−1 recombinant SCF (Sino Biological), along with 0.5 mg ml−1 G418 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and/or 1.5 μg ml−1 puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Five days later, the colony cells were collected and replated into 96-well plates at different doses of cell number with 24 replicates for each group. (Z)-4-OHT (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in ethanol was added to methylcellulose medium at a final concentration of 1 µM when necessary. After 7–10 days, the number of wells with colonies was counted. ELDA software was used to analyse frequencies of LSCs/LICs.

LC–MS/MS for determination of RNA modifications

RNA ac4C and m6A quantification by LC–MS/MS was performed as described previously25,68,69. In brief, 200 ng of total RNA or other RNA components isolated from it (for example, poly(A) RNA, rRNA and tRNA) were digested by nuclease P1 (1 U, New England Biolabs) at 37 °C for 2 h, followed by the addition of alkaline phosphatase (1 U, Takara) and incubation at 37 °C for another 2 h. The nucleosides were separated by reverse-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography on a C18 column (Agilent) with online MS detection using Agilent 6470 Triple Quadrupole LC–MS System at a flow rate of 0.25 ml min−1. Buffer A: 0.1% formic acid; buffer B: 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid with the gradient as follows: 0–1 min, 100% A; 1–2.4 min, 99.8% A; 2.4–3.8 min, 99.2% A; and 3.8–5.2 min, 98.2% A. Quantification was performed by comparison with the standard curve obtained from pure nucleoside standards. The ratio of ac4C to C or m6A to A was calculated based on the calculated concentrations.

RacRIP-seq