ABSTRACT

Background and Aims

Women's autonomy in healthcare decision‐making is crucial for improving maternal and child health. Despite its importance, there is limited evidence on autonomous healthcare decision making particularly in postpartum women. Thus, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of postpartum women's autonomy in healthcare decision making and its associated factors in Chencha town, Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia.

Methods

A community based cross‐sectional study was conducted among 617 postpartum women in southern Ethiopia from October 1 to November 30, 2023. A study participants were selected by a simple random sampling technique. The data were collected through pretested and interviewer administered questionnaire. Following coding and entry into Epi‐data version 3.1, the data were exported into statistical package for social science software (SPSS version 26) for analysis. A logistic regression model was fitted and, variables with p < 0.05 were declared to be significantly associated with women autonomy in healthcare decision‐making.

Results

In this study, 61.6% of postpartum women have autonomous in their health care decision making with 95% confidence interval (CI): 57.4, 65.3. Women age over 35 years (AOR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7, 6.0), enrollment in community‐based health insurance (AOR = 1.5 95% CI: 1.0, 2.3), having four and above antenatal care visits (AOR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.6, 3.8), using skilled delivery service (AOR = 4.3, 95% CI: 2.9, 6.6), having primary educational level (AOR = 4.9, 95% CI: 3.0, 8.0), and secondary and above educational level (AOR = 5, 95% CI: 3.1, 8.0) were positively associated with women autonomy in health care decision making.

Conclusion

This study revealed that majority of postpartum women were autonomous in their healthcare decision making. Maternal age, educational status, enrollment in community‐based health insurance, having frequent ANC follow‐up and using skilled delivery service were factors significantly associated with women's autonomy. Focus should be given to improve women antenatal care follow‐up and the enrollment of community‐based health insurance.

Keywords: Ethiopia, healthcare decision making, postpartum women, women autonomy

Abbreviations

- ANC

antenatal care

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- EDHS

Ethiopian demographic health survey

- PNC

postnatal care

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Science

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. Introduction

Women's autonomy is the ability to make independent decisions in various aspects of life, including healthcare decision making, it is a vital determinant of maternal and child health [1]. When women are autonomous to make healthcare decisions independently, they can better manage their health and the health of their children [2, 3]. women's autonomy is critical for accessing reproductive healthcare, utilizing contraceptives, and managing sexual health, including the prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [4].

However, in many developing countries, women's autonomy is often restricted. Traditionally, men hold the role of primary decision‐makers in families, which limits women's ability to make health‐related decisions. This lack of autonomy directly affects maternal health outcomes [5]. Women with limited decision‐making power are less likely to access essential services like antenatal care, skilled delivery, and postnatal care, which are vital for reducing maternal mortality [6]. Further, the inadequate use of maternal health services significantly increases the risk of complication and maternal death [7].

Globally, maternal mortality remains a pressing issue, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), where gender inequality and limited women autonomous healthcare seeking persist [8]. In 2020, approximately 287 000 maternal deaths occurred worldwide, with 800 women dying each day from preventable pregnancy and childbirth complications [9]. Sub‐Saharan Africa bears a disproportionate share of these deaths, where a woman's lifetime risk of dying from maternal causes is 1 in 37, compared to 1 in 4800 in high‐income countries [10].

In Ethiopia, while progress has been made in reducing the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 871 per 100 000 live births in 2000 to 401 per 100 000 in 2017, maternal mortality remains a significant challenge [11]. Around 12 000 women still die each year due to complications that could have been prevented with better healthcare access and decision‐making autonomy [12]. Promoting women's autonomy in healthcare decisions is a critical strategy for addressing these challenges and achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) related to maternal health [13].

Despite improvements in maternal health, disparities in women's autonomy persist, particularly in Ethiopia, where geographical location, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity continue to affect healthcare decision‐making [14]. Between 2005 and 2011, women's autonomy in healthcare decisions declined, contributing to the high maternal mortality rate, especially among disadvantaged population [15].

Previous studies in Ethiopia highlighted increased autonomy, with factors such as higher education, employment, media exposure, and better household economic status [16, 17]. However, the previous studies were focused on the rural areas, and the effect of enrollment in community health insurance was not investigated. Therefore this study aimed to assess the prevalence of postpartum women autonomy in healthcare decision making and its associated factors in Chencha town, southern Ethiopia.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Setting and Period

Chencha town, located in the Gamo Zone of the Southern Ethiopia. The town has a total population of 111 686, with 51 310 men and 60 376 women. The majority of the residents in Chencha are Gamo people, who speak the Gamo language and follow the Orthodox Christian faith. The town is situated 37 km from Arba Minch, the capital of the Gamo Zone, and 441.4 km from Addis Ababa. There is one primary hospital and two health centers providing healthcare services for the town's population [18]. The study was conducted from October 1 to November 30, 2023.

2.2. Study Design

A community based cross sectional study.

2.3. Population

All postpartum women living in Chencha town were source population, whereas, randomly selected women who gave birth in the last 6 months and living in selected kebeles of Chencha town were study population.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

All women who gave birth in the last 6 months during the data collection period were included in the study. However, women who were unable to respond due to severe illness at the time of the interview were excluded from the study.

2.5. Sample Size Determination

The required sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula considering the following assumptions. Proportion (p) of women autonomy in healthcare decision making (58.4%) [19], 95% confidence interval (CI), 5% margin of error and 10% for the potential rate of nonresponse. By adding a design effect, 411 × 1.5 = 617 was the final sample size.

2.6. Sampling Techniques and Procedures

The selection of a representative sample was performed using a multistage sampling process. Of the eight kebeles in Chencha town five kebeles were selected using a simple random sampling technique. Then, a list of households with mothers who had given birth in the past 6 months was obtained from the health extension workers' registry in the selected kebeles. This list served as the sampling frame, representing all households eligible for inclusion in the study. Using SPSS, a table of random numbers was generated to randomly select study participants from this sampling frame, the sample size was proportionally allocated to each kebele in the study setting. The selected households were then contacted using their household IDs, with assistance from health extension workers.

2.7. Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

Data were collected using a pretested, structured, interviewer‐administered questionnaire adapted from relevant literature [19, 20, 21]. The questionnaire had three sections: socio‐demographic factors, obstetric‐related factors, and sociocultural and maternal health factors. It was translated into the local language by language experts and translated back into English to check its consistency. Six diploma‐level midwives were recruited for data collection, with two BSc midwives supervising the process. All data collectors and supervisors received a 1‐day orientation covering the study's purpose, confidentiality, and interview procedures. To reduce nonresponse, participants who were initially unavailable were contacted up to three additional times. The process was supervised daily by the supervisor and principal investigator.

2.8. Variables of the Study

The dependent variable for this study was women's autonomy in healthcare decision‐making whereas the explanatory variables were women's age, religion, women's educational level, women's occupation, husband occupation, husband educational level, community Health insurance enrollment, wealth index, media exposure, parity, ANC, number of ANC, place of delivery, assistant for the delivery, PNC, number of PNC, family planning use and time taken to the health facility.

2.9. Operational Definition and Measurement

Women's autonomy in healthcare decision‐making: This was measured based on women's response to “person who usually decides on respondent's health care.” The responses of this dependent variable were coded as (1) independently, (2) together with others, and (3) others. For analysis, we recoded the data so that women who made healthcare decisions either alone or with their partner were coded as “1,” while those whose partner made the decision alone were coded as “0.” In this context, “0” indicates that the woman has no autonomy in healthcare decision‐making, while “1” indicates that she has autonomy [15, 17, 19].

Antenatal care four and above (ANC 4): Was defined as “Yes” if the women had attended antenatal care at least four times during the last pregnancy [13].

Skilled delivery: was defined as “Yes” and coded as “1” if the women gave birth in health institutions (hospitals, clinics or health centers, health posts, and other health care centers) in the last birth, or had a skilled health professional (doctor, nurse, or midwife) assist with the last delivery [22].

Postnatal care: was defined as “Yes” and coded as 1 when women came for a postnatal checkup within 6 weeks after a delivery period and at least one PNC visit within 6 weeks by skilled health workers [13].

Community health insurance membership: If they were covered by community health insurance, they were coded “yes” (insured), and individuals not insured were coded “no” [23].

Household wealth index: It is a composite measure of a household's cumulative living standard. Based on the net score wealth status of respondents is classified into three poor, medium, and rich. A total of 37 items, including domestic animals, durable assets, productive assets, dwelling characteristics, any variable or assets owned by more than 90% or less than 5% were excluded, The Keiser–Mayer Olkin measure of sample adequacy (≥ 0.6) used to check the PCA assumption, anti‐image correlations (> 0.4), and Bartlett Sphericity Test (p‐value 0.05) [24].

2.10. Data Quality Control

To ensure data quality the questionnaire was reviewed by researchers with experts in the study's subject matter and a pretest was done on 5% (31 samples) of the total sample size at Birbir town 2 weeks before the actual data collection. Based on pretest result necessary adjustments were made and the revised questionnaire was used for the actual data collection. Data collectors and supervisors received 3 days training on the study's objectives, the data collection tool, and the methods of data collection. Additionally, close supervision was ensured on each data collection day.

2.11. Data Analysis and Processing

The collected data were cleaned, coded and entered into Epi‐data version 3.1 and exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics such as percentages, frequency, mean, and standard deviation was used to summarize the characteristics of the study participants and the findings were presented by using tables and graphs. The binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with the outcome. Initially, bivariable analysis was done to identify the candidate explanatory variables for the multivariable analysis. Thereafter, all explanatory variables having a p‐value of less than 0.25 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis to control the possible confounders and identify independent predictors of women autonomy. Model fitness was checked by using Hosmer Lemeshow goodness of fit test, it was founded to be insignificant (p = 0.568), which indicates good model fitness. Multicollinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor (VIF), none of the variables were yielding VIF greater than five. Adjusted odds ratio with 95% CI were reported and variables with a p‐value of less than 0.05 were declared to be significantly associated with women autonomy in healthcare decision making. The reporting of this study follows the criteria specified in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [25].

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

In this study, a total of 617 participants were interviewed resulting in a response rate of 100%. The mean age was 28.41 years (±4.94 SD) and about 322 (52.2%) fell within the age group of 25–34 years. Among the participants, 84.4% were married and 50.5% were housewives. In terms of the husband's occupation and education, 46.2% of them worked as farmers, and 39.0% of the husbands had no formal education. In relation to the house wealth index, approximately one‐third (31.9%) of the participants were classified as rich (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of study participants according to their sociodemographic characteristics in Chencha town southern Ethiopia (n = 617).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 15–24 | 169 | 27.4 |

| 25–34 | 322 | 52.2 | |

| > 35 | 126 | 20.4 | |

| Religion | Protestant | 217 | 37.1 |

| Orthodox | 400 | 64.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 521 | 84.4 |

| Others | 96 | 15.6 | |

| Ethnicity | Gamo | 548 | 88.8 |

| Others | 69 | 11.2 | |

| Women education | No formal education | 252 | 40.8 |

| Primary education | 174 | 28.2 | |

| Secondary and above | 191 | 31 | |

| Women occupation | Housewife | 312 | 50.5 |

| Merchant | 75 | 12.2 | |

| Farmer | 150 | 24.4 | |

| Employed | 80 | 12.9 | |

| Husband occupation | Farmer | 285 | 46.2 |

| Merchant | 117 | 18.9 | |

| Employed | 95 | 15.4 | |

| Daily laborer | 120 | 19.5 | |

| Husband education | No formal education | 241 | 39.0 |

| Primary education | 255 | 41.3 | |

| Secondary and above | 121 | 19.6 | |

| House wealth index | Poor | 197 | 31.9 |

| Medium | 207 | 33.5 | |

| Rich | 213 | 34.5 |

3.2. Socio‐Cultural Related Characteristics

The study findings indicated that 51.5% of the participants were registered in the community health insurance program. 51.7% of the participants had received information on maternal health from various sources, with the majority (50.2%) reporting as the primary Mass media as source of information. Furthermore, the study highlighted that 40.7% of the women had to travel a distance of 30 min or more on foot to reach the nearest healthcare facility (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio‐cultural Characteristics of study participants of Chencha town southern, Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 617).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community health insurance enrollment | Yes | 318 | 51.5 |

| No | 299 | 48.5 | |

| Heard about maternal health | Yes | 319 | 51.7 |

| No | 298 | 48.3 | |

| Source of maternal health information (n = 319) | Mass media | 160 | 50.2 |

| Health care provider | 159 | 49.8 | |

| Time taken to reach health facilities | ≥ 30 min | 251 | 40.7 |

| < 30 min | 366 | 59.3 |

3.3. Obstetric Care Related Characteristics

Regarding the obstetric history of the women included in this study, the analysis revealed that 67.6% were multiparous 72% of the women's pregnancies were planned. In relation to family planning services, 44.9% of the participants reported previous use of contraceptives. Furthermore, 12.3% of the respondents reported poor obstetric outcomes during their previous pregnancies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Obstetric carerelated characteristics of women in Chencha town, Southern Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 617).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first pregnancy | Below 19 | 93 | 15.1 |

| 20–29 | 511 | 82.8 | |

| Above 30 | 13 | 2.1 | |

| Parity | Prim parous | 200 | 32.4 |

| Multiparous | 417 | 67.6 | |

| Previous use of contraceptive | Yes | 277 | 44.9 |

| No | 340 | 55.1 | |

| Pregnancy wanted | Planned | 444 | 72 |

| Unplanned | 173 | 28 | |

| Pregnancy‐related complication | Yes | 39 | 6.3 |

| No | 578 | 93.7 | |

| Poor obstetric History | Yes | 76 | 12.3 |

| No | 541 | 87.7 |

Note: Prim parous = having one viable pregnancy (≥ 28 weeks), multiparous = having more than one viable pregnancy (≥ 28 weeks).

3.4. Maternal Health Service‐Related Factors

Among women, 43.9% attended four or more ANC visits. Regarding the place of delivery, 50.1% of women gave birth in a health facility. However, only 31.8% of the women attended postnatal care (Table 4).

Table 4.

Maternal health service‐related factors among women in southern Chencha town, Ethiopia, 2023 (n = 617).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time during first antenatal care | > 16 weeks | 397 | 64.4 |

| ≤ 16 weeks | 220 | 35.6 | |

| ANC four and above | Yes | 271 | 43.9 |

| No | 346 | 56.1 | |

| Place of delivery | Health Institution | 309 | 50.1 |

| Home | 308 | 49.9 | |

| Postnatal care | Yes | 196 | 31.8 |

| No | 421 | 68.2 | |

|

Time of PNC Visit n = 196 |

Within 2 days | 128 | 20.9 |

| Within 3–7 days | 47 | 7.9 | |

| 7 days–2 weeks | 5 | 0.5 | |

| 2 weeks–6 weeks | 16 | 2.6 |

Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; PNC, postnatal care.

3.5. Women Autonomy in Health Care Decision Making

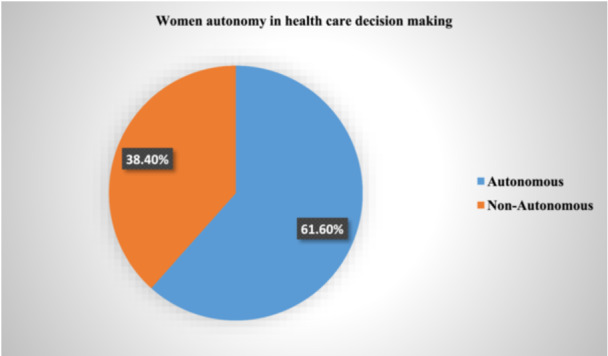

In Chencha town, Women autonomy in health care decision making was found to be 61.6% (95% CI: 57.4, 65.3), indicating that 38.4% of women were nonautonomous related to their health care decision making (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The proportion of women who had women autonomy in health care decision in Chencha town, southern Ethiopia, 2023.

3.6. Factors Associated With Women Autonomy in Health Care Decision Making

In the binary logistic regression analysis, women age over 35 years, education level, enrollment in community‐based health insurance, previous family planning use, parity, ANC four and above, skilled delivery service and having maternal health information were associated with the outcome variable (Table 5).

Table 5.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of women autonomy in Health care decision making among women who give birth in the last 6 months in Chencha town, 2023.

| Variable | Categories | Autonomous women | COR = (95% CI) | AOR = (95% CI) | p‐ value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||||

| Age | 15–24 | 90 (53.3%) | 79 (46.7%) | 1 | ||

| 25–34 | 189 (58.7%) | 133 (41.3%) | 1.5 (0.8–1.8) | 1 (0.6–1.6) | 0.91 | |

| > 35 | 101 (80.2%) | 25 (19.8%) | 3.5 (2–6) | 3.2 (1.7– 6.0) | < 0.01 | |

| Women education level | No formal education | 103 (40.9%) | 149 (59.1) | 1 | ||

| Primary education | 130 (74.7%) | 44 (25.3%) | 4.2 (2.7–6.5) | 4.9 (3.0–8.0) | < 0.01 | |

| Secondary and above | 147 (77.0%) | 44 (23.0%) | 4.8 (3.1–7.3) | 5.0 (3.1–8.1) | < 0.01 | |

| Community‐based health insurance | Yes | 219 (68.9%) | 99 (31.1%) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 0.03 |

| No | 161 (53.8%) | 138 (46.2%) | 1 | |||

| Previous family planning use | Yes | 180 (65%) | 97 (35%) | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.58 |

| No | 200 (58.8%) | 140 (41.25) | 1 | |||

| Parity | Prim porous | 116 (58. %) | 84 (42%) | 1 | ||

| Multiparous | 264 (63.3%) | 153 (36.7%) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 0.9 (0.6– 1.4) | 0.79 | |

| ANC four and above | Yes | 205 (75.6%) | 66 (24.4%) | 3 (2.1–4.3) | 2.5 (1.6–3.8) | < 0.01 |

| No | 175 (50.6% | 171 (49.4%) | 1 | |||

| Skilled delivery service | Yes | 243 (78.6%) | 66 (21.4%) | 4.5 (3.2–6.5) | 4.3 (2.9– 6.6) | < 0.01 |

| No | 137 (44.5%) | 171 (55.5%) | 1 | |||

| Having maternal health information | Yes | 194 (65.1%) | 104 (34.9%) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7– 1.6) | 0.54 |

| No | 186 (58.3%) | 133 (41.7%) | 1 | |||

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COR, crude odds ratio.

In multivariate logistic analysis, women age over 35 years (AOR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7, 6.0), having primary educational level (AOR = 4.9, 95% CI: 3, 8), secondary and above educational level (AOR = 5, 95% CI: 3.1, 8), enrollment in community‐based health insurance (AOR = 1.5 95% CI: 1.0, 2.3), having ANC four and above visits (AOR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.6, 3.8), and skilled delivery service utilization (AOR = 4.3,95% CI: 2.9, 6.6) were positively associated with women autonomy in health care decision making (Table 5).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of women autonomy in health care decision‐making and associated factors among postpartum women in Chencha town southern Ethiopia. The finding revealed that the prevalence of postpartum women's autonomy was 61.6% (95% CI: 57.4, 65.3). Maternal age, educational status, enrollment in community‐based health insurance, having frequent ANC follow‐up and using skilled delivery service were factors significantly associated with postpartum women's autonomy in healthcare decision making.

The prevalence of women autonomy in this study was consistent with findings from studies in Mettu and Wolaita zones in Ethiopia, which reported autonomy rates of 58.4% and 60.5%, respectively [2, 19]. However, the autonomy rate in this study is lower than the study done in Debretabor (75.4%), yet higher than the result of study conducted in Bale zone (41.4%) [13, 21]. The discrepancy in findings may be attributed to differences in socioeconomic status, demographic characteristics, outcome variable measurement, study population, and study periods. Additionally, variations in the inclusion criteria, such as including women who gave birth recently along with differences in study settings could also contribute to these differences.

In this study, women over the age of 35 years were three times more likely to be autonomous in their healthcare decision making compared to their counterparts. This finding aligns with studies conducted in Debertabor, Mettu District, and Bale Zone, Ethiopia [2, 20, 21]. The possible explanation for this association could be that younger women are often burdened with significant responsibilities, such as managing household tasks, building homes, and caring for livestock and children. In many cases, these women are undervalued and lack control over financial resources or key decisions, even those related to their own health and personal life. As they age, however, they tend to attain higher levels of respect, which can shift the dynamics in their relationships. This often results in greater mutual respect between partners, with older women having more influence in decision‐making and a stronger voice in matters affecting their lives, including healthcare [26, 27].

The odds of women autonomy in healthcare decision making was higher among women who achieved primary and more educational status when compared with women who have informal educational status. This is in line with studies conducted in Ethiopia Mettu district [20]. The possible justification for this association can be the fact that educated women have a better ability to comprehend and utilize essential health information and services to make informed decisions about their health. Moreover, educated women are more likely to challenge traditional norms, assert their rights in accessing healthcare, and make independent decisions without relying solely on others, such as partners or family members, to guide their choices. This can positively impact their health behaviors and outcomes. As reason, educated women are more autonomous in health care decision making [28].

Women who were enrolled in community health insurance were twice more likely to be autonomous in healthcare decision‐making compared to those who were not enrolled. This finding aligned with studies conducted in sub‐Saharan Africa that showed a positive association between women's decision‐making autonomy and health insurance enrollment [23]. This because the insurance provides financial security, better access to healthcare services, and increased knowledge about health. Enrollment in community health insurance reduces their reliance on others for healthcare decisions and enhances their independence and gender equality in health [20].

In addition, women who exercised autonomy in healthcare decision‐making were three times more likely to attend four or more ANC visits compared to those who did not. This finding aligns with the results of similar study conducted in Mettu district [20]. This is likely because autonomous women have more control over their health‐related choices, which enables them to prioritize and seek timely, adequate antenatal care. Their ability to make independent decisions empowers them to recognize the importance of regular ANC visits for monitoring their pregnancy [29].

Furthermore, the odds of women autonomy in healthcare decision making were four times higher among women who used skilled delivery service compared with their counterparts. This finding aligns with the results of multiple analysis from the Ethiopian Demographic Survey [13]. The possible justification for this association could be that autonomous women are more empowered to seek and access quality healthcare services. They are more likely to recognize the benefits of skilled care during childbirth and can make informed decisions without needing to rely on others. This autonomy enhances their confidence in navigating healthcare systems but also underscores the importance of supporting women's rights to make independent decisions about their reproductive health [30].

5. Limitations of the Study

The cross sectional study may not establish the temporal relationship between outcome and predictor variables. A limitation of the study is that it did not include husbands perspectives and their might be recall bias on assessing maternal healthcare service utilization.

6. Conclusion

In this study, the majority of postpartum women were autonomous in their healthcare decision making. Maternal age over 35 years, educational status primary and above, enrollment in community‐based health insurance, having frequent antenatal care follow‐up, and using skilled delivery service were factors significantly associated with postpartum women's autonomy in healthcare decision making. Focus should be given to improve women frequent antenatal care follow‐up and the enrollment of community‐based health insurance by providing health education for pregnant women. In addition, clinicians and policymakers should prioritize the strategies that promote women's autonomy to achieve better health outcome.

Author Contributions

All authors (A.H., A.A.L., F.A.K, A., A.E., and T.K.) equally contributed in the conception of the research problem, initiated the research, wrote the research proposal, conducted the research, made data entry, analysis and interpretation and wrote and reviewed the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, Addisalem Haile had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from Arba Minch University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Institutional Review Board (IRB) with a reference number of IRB/1476/2023. In addition, permission was obtained from the Gamo zone health office and Chencha town. Before data collection, informed consent was obtained from study participants and the right to withdraw from the interview was guaranteed. The privacy and confidentiality of the information obtained from the respondents were kept confidential and anonymous.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest.

Transparency Statement

The lead author Addisalem Haile affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Arba Minch University for the opportunity to conduct this research and present the thesis report. We also sincerely appreciate the dedication and time contributed by the data collectors, supervisors, and study participants during the data collection period. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Rose L., “Women's Healthcare Decision‐Making Autonomy by Wealth Quintile From Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in Sub‐Saharan African Countries,” International Journal of Women's Health and Wellness 3 (2017): 54, 10.23937/2474-1353/1510054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nigatu D., Gebremariam A., Abera M., Setegn T., and Deribe K., “Factors Associated With Women's Autonomy Regarding Maternal and Child Health Care Utilization in Bale Zone: A Community Based Cross‐Sectional Study,” BMC Women's Health 14, no. 1 (2014): 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yohannes Dibaba W., “Women's Autonomy and Reproductive Health‐Care‐Seeking Behavior in Ethiopia,” Women\& Health 58, no. 7 (2018): 729–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kabir R., Alradie‐Mohamed A., Ferdous N., Vinnakota D., Arafat S. M. Y., and Mahmud I., “Exploring Women's Decision‐Making Power and HIV/AIDS Prevention Practices in South Africa,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 24 (2022): 16626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bitew D. A., Asmamaw D. B., Belachew T. B., and Negash W. D., “Magnitude and Determinants of Women's Participation in Household Decision Making Among Married Women in Ethiopia, 2022: Based on Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey Data,” Heliyon 9, no. 7 (2023): e18218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee S., Nantale R., Wani S., Kasibante S., and Marvin Kanyike Kanyike A., “Influence of Women's Decision‐Making Autonomy and Partner Support on Adherence to the 8 Antenatal Care Contact Model in Eastern Uganda: A Multicenter Cross‐Sectional Study,” European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 300 (2024): 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tunçalp Ӧ, Pena‐Rosas J. P., Lawrie T., et al., “WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience‐Going Beyond Survival,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 124, no. 6 (2017): 860–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Odusina E. K. and Oladele O. S., “Is There a Link Between the Autonomy of Women and Maternal Healthcare Utilization in Nigeria? A Cross‐Sectional Survey,” BMC Women's Health 23, no. 1 (2023): 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO , Global Maternal Health (WHO, 2023), https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1.

- 10. WHO U, UNFPA, World Bank Group and, Division tUNP , Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000–2017 (WHO, 2019).

- 11. EPHI I , Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey: Key Indicators (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI, 2019).

- 12. Tessema G. A., Laurence C. O., Melaku Y. A., et al., “Trends and Causes of Maternal Mortality in Ethiopia During 1990–2013: Findings From the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2013,” BMC Public Health 17, no. 1 (2017): 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tiruneh F. N., Chuang K.‐Y., and Chuang Y.‐C., “Women's Autonomy and Maternal Healthcare Service Utilization in Ethiopia,” BMC Health Services Research 17, no. 1 (2017): 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Health FMO , National Health Equity Strategic Plan. Addis Ababa (Health FMO, 2020).

- 15. Asabu M. D. and Altaseb D. K., “The Trends of Women's Autonomy in Health Care Decision Making and Associated Factors in Ethiopia: Evidence From 2005, 2011 and 2016 DHS Data,” BMC Women's Health 21, no. 1 (2021): 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borde M. T., “A Woman's Lifetime Risk Disparities in Maternal Mortality in Ethiopia,” Public Health Challenges 2, no. 1 (2023): e56. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tesema G. A., Yeshaw Y., Kasie A., Liyew A. M., Teshale A. B., and Alem A. Z., “Spatial Clusters Distribution and Modelling of Health Care Autonomy Among Reproductive‐Age Women in Ethiopia: Spatial and Mixed‐Effect Logistic Regression Analysis,” BMC Health Services Research 21, no. 1 (2021): 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chencha Town Health Office, Annual Report (Chencha, 2022).

- 19. Alemayehu M. and Meskele M., “Health Care Decision Making Autonomy of Women From Rural Districts of Southern Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross‐Sectional Study,” International Journal of Women's Health 9 (2017): 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kassahun A. and Zewdie A., “Decision‐Making Autonomy in Maternal Health Service Use and Associated Factors Among Women in Mettu District, Southwest Ethiopia: A Community‐Based Cross‐Sectional Study,” BMJ Open 12, no. 5 (2022): e059307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kebede A. A., Cherkos E. A., Taye E. B., Eriku G. A., Taye B. T., and Chanie W. F., “Married Women's Decision‐Making Autonomy in the Household and Maternal and Neonatal Healthcare Utilization and Associated Factors in Debretabor, Northwest Ethiopia,” PLoS One 16, no. 9 (2021): e0255021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tesfaye B., Atique S., Azim T., and Kebede M. M., “Predicting Skilled Delivery Service Use in Ethiopia: Dual Application of Logistic Regression and Machine Learning Algorithms,” BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 19, no. 1 (2019): 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zegeye B., Idriss‐Wheeler D., Ahinkorah B. O., et al., “Association Between Women's Household Decision‐Making Autonomy and Health Insurance Enrollment in Sub‐Saharan Africa,” BMC Public Health 23, no. 1 (2023): 610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Habte A., Gizachew A., Ejajo T., and Endale F., “The Uptake of Key Essential Nutrition Action (ENA) Messages and Its Predictors Among Mothers of Children Aged 6–24 Months in Southern Ethiopia, 2021: A Community‐Based Crossectional Study,” PLoS One 17, no. 10 (2022): e0275208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. von Elm E., Altman D. G., Egger M., Pocock S. J., Gøtzsche P. C., and Vandenbroucke J. P., “The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies,” Annals of Internal Medicine 147, no. 8 (2007): 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoppe K. A., “Ifi Amadiume. Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 18, no. 3 (2016): 498–500. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abedin S. and Arunachalam D., “Risk Deciphering Pathways From Women's Autonomy to Perinatal Deaths in Bangladesh,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 26, no. 11 (2022): 2339–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kilfoyle K. A., Vitko M., O'Conor R., and Bailey S. C., “Health Literacy and Women's Reproductive Health: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Women's Health 25, no. 12 (2016): 1237–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yeo S., Bell M., Kim Y. R., and Alaofè H., “Afghan Women's Empowerment and Antenatal Care Utilization: A Population‐Based Cross‐Sectional Study,” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 22, no. 1 (2022): 970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Das S., ‐ Deepak , and Singh R. R., “Does Empowering Women Influence Maternal Healthcare Service Utilization?: Evidence From National Family Health Survey‐5, India,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 28, no. 4 (2023): 679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.