Abstract

Diseases of Theobroma cacao L. (Malvaceae) disrupt cocoa bean supply and economically impact growers. Vascular streak dieback (VSD), caused by Ceratobasidium theobromae, is a new encounter disease of cacao currently contained to southeast Asia and Melanesia. Resistance to VSD has been tested with large progeny trials in Sulawesi, Indonesia, and in Papua New Guinea with the identification of informative quantitative trait loci (QTLs). Using a VSD susceptible progeny tree (clone 26), derived from a resistant and susceptible parental cross, we assembled the genome to chromosome‐level and discriminated alleles inherited from either resistant or susceptible parents. The parentally phased genomes were annotated for all predicted genes and then specifically for resistance genes of the nucleotide‐binding site leucine‐rich repeat class (NLR). On investigation, we determined the presence of NLR clusters and other potential disease response gene candidates in proximity to informative QTLs. We identified structural variants within NLRs inherited from parentals. We present the first diploid, fully scaffolded, and parentally phased genome resource for T. cacao L. and provide insights into the genetics underlying resistance and susceptibility to VSD.

Core Ideas

Large progeny trials have identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for resistance to vascular streak dieback (VSD) of Theobroma cacao.

New genome technologies permit diploid assemblies and greater scrutiny of parentally inherited chromosomes.

We built the diploid genome of a VSD susceptible progeny of resistant maternal and susceptible paternal trees.

We investigated resistance genes at QTLs and found differences based on parental inheritance.

Abbreviations

- LRR

leucine‐rich repeat

- NLR

nucleotide binding site leucine‐rich repeat gene models

- PPR

Phytophthora pod rot

- VSD

vascular streak dieback

1. INTRODUCTION

Cacao, Theobroma cacao L. (Malvaceae), is an important perennial tree crop producing beans that are used as raw materials in the chocolate, beverage, and cosmetic industries (Schnell et al., 2007). Much of the world's cocoa bean production comes from small‐holder, mixed‐crop farms in some 50 countries that depend on trade with developed countries where the raw product is manufactured into chocolate (Daymond et al., 2022). Cacao is a difficult crop to grow profitably due to several endemic problems. Alongside other problems, diseases disrupt the supply of cocoa and have serious economic impacts on growers (Marelli et al., 2019). Responses to disease can lead to tree removal and replacement with more profitable and reliable crops (Daymond et al., 2022). The center of origin for T. cacao is the Upper Amazon, South America, where evolutionary studies indicate divergence from close common ancestors around 9.9 million years ago (Richardson et al., 2015). While genetic diversity exists within the geographic center of origin, cultivation largely relies on a limited genetic pool of T. cacao (Motamayor et al., 2008). Despite this relative homogeneity in cultivated cacao, genetic variation in agronomic and disease response trait‐related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPS) are present (Orduña et al., 2024).

Southeast (SE) Asia is one of the major suppliers of cocoa beans, and cultivation has historically been relatively disease‐free due to the lack of coevolved pathogens (Bailey & Meinhardt, 2016). However, in the 1960s, vascular streak dieback (VSD) emerged as a new encounter disease of cacao and caused devastating crop losses in Papua New Guinea (PNG) (Guest & Keane, 2007). The causal agent of VSD is Ceratobasidium theobromae, a fastidious biotrophic fungus first discovered and described by Philip Keane et al. (1972). Ceratobasidium theobromae then spread to other SE Asian and Melanesian cacao regions as an emergent disease on cacao (Guest & Keane, 2007). In Indonesia, the pathogen has spread into Sumatera Regions (Trisno et al., 2016) and was subsequently confirmed in a new area of Barru District, South Sulawesi (Junaid et al., 2020). The pathogen is believed to be contained in the SE Asia region; however, closely related strains, based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, have recently been identified in diverse host species and across distant geographic regions. Notably, fungal isolates from diseased cassava (Manihot esculenta) in Laos (Leiva et al., 2023) and from horticultural plants in North America (Beckerman et al., 2022) show closely aligned ITS sequences. In cacao, symptoms include green spotted chlorosis in older leaves and vascular browning in the petioles and stems that often lead to rapid branch or whole tree death in susceptible genotypes (Guest & Keane, 2007; Samuels et al., 2012). Infection is initiated when hyphae, from germinated basidiospores, penetrate immature leaves and colonize the xylem. Disease symptoms are typically only visible after 3 months leading to potential delays in containment (Marelli et al., 2019). Some genotypes of T. cacao that were resistant to disease 50 years ago remain resistant, indicating that durable resistance is highly heritable and therefore may be exploited in breeding to introgress resistance into new, improved cacao genotypes (Tan & Tan, 1988).

Varieties of cacao that show resilience to infection by C. theobromae have been studied in both PNG and Sulawesi, Indonesia. Results of these studies identified informative quantitative trait loci (QTLs) that correlate with both qualitative and quantitative resistance in progeny populations (Epaina, 2012; Singh, 2021). The two independent studies used progenies derived from crosses between Trinitario KA2‐101 (resistant to VSD) and K82 (susceptible to VSD) in PNG (Epaina, 2012), and between Amelonado S1 (resistant to VSD) with Iquitos, Criollo, and Amelonado RUQ 1347 (susceptible to VSD and formerly known as CCN 51) in Sulawesi, Indonesia (Singh, 2021). The progeny trials used 346 and 130 progeny that segregated in response to VSD in PNG and Sulawesi, respectively. The informative QTLs associated with resistance indicated a likely polygenic response and were mapped onto nine of the 10 T. cacao chromosomes from the PNG progeny trial (Epaina, 2012) and three in the Sulawesi trial (Singh, 2021). The two studies used either simple sequence repeat (SSR) or SNP markers and compared linkage maps with established disease resistance mapping developed by Lanaud et al. (2009). The available genomes for Matina 1–6 (Motamayor et al., 2013) and Criollo (Argout et al., 2011) were used to inform the linkage maps. Interestingly, VSD QTLs co‐localized with a region identified for resistance to Phytophthora pod rot (PPR) and Frosty pod rot (FP) (causal agents Phytophthora palmivora and Moniliophthora roreri, respectively) on chromosome 8, while others were common for response to both VSD and PPR on chromosomes 3, 4, and 5 in only one study. Both studies identified VSD QTLs within similar regions on chromosomes 3, 8, and 9. These apparent shared QTL regions indicate hotspots for disease resistance.

Classical selection and breeding for resistance, particularly in perennial trees, can be a long and difficult process (Sniezko, 2006). The research is further complicated for resistance to C. theobromae as the pathogen cannot be cultured in vitro and is extremely slow growing within the host plant before visible symptoms develop. Traditional Koch's postulates cannot be satisfied for biotrophic organisms; however, molecular approaches are becoming increasingly important in validation studies (Bhunjun et al., 2021). Understanding the genetics underlying resistance and susceptibility to VSD is likely to accelerate the breeding cycle by providing clear targets for molecular screening.

Effective plant responses to disease at the molecular level are well established as involving resistance genes of the nucleotide‐binding site leucine‐rich repeat family (NLRs) (Fluhr et al., 2001). NLR genes are known to be numerous, clustered, and highly polymorphic both between and within species (Barragan & Weigel, 2020; Santos et al., 2022; Weyer et al., 2019; Van de Weyer et al., 2019). We therefore approached the problem of understanding the underlying genetics of resistance to VSD by building on the structural knowledge of NLR genes and from the progeny QTL studies of Epaina (2012) and Singh (2021). We aimed to leverage the latest sequencing and bioinformatic approaches to gain a clearer insight into the genetic regions of interest. Our premise for the work was that (i) QTLs are informative for predicting resistance, (ii) genetic resistance hotspots are present, (iii) QTLs may indicate the presence of NLR gene clusters, and (iv) polymorphic NLR genes within clusters, from contrasting genotypes, may explain disease phenotype. The questions we therefore posed were, can we assemble the cacao genome and successfully discriminate alleles inherited from parents of known VSD phenotype within an F1 tree progeny, and if so, can we determine differences in NLR clusters, type, and specific gene sequences at the QTL locations, based on parentage? An additional question that we tested was, using new sequencing technologies, can we assemble and scaffold to chromosome level both pathogen (∼30 Mb) and host (∼380 Mb) genomes from a single sample? This would circumvent the inability to culture the biotrophic C. theobromae and provide insight into the genomics of a compatible interaction. This final aim was not successful due to the limited pathogen DNA we were able to extract, but future studies could work to improve on this approach.

Taking these premises and goals, we built a high‐quality parental phased genome resource for a susceptible cacao (clone 26) of known parental cross, S1 maternal and RUQ 1347 paternal. We annotated the genome for all predicted genes, and then specifically for only NLR‐type genes, and conducted fine‐scale investigation of genomic regions associated with resistance to C. theobromae to determine the resistance gene complements inherited from both parents. We made comparative studies into the NLR genes at QTL locations and show structural differences within parentally inherited chromosomes, potentially providing insights into resistance to VSD and other serious diseases of cacao. Additionally, we provide the first diploid, fully scaffolded, and parentally phased genome resource for T. cacao L.

Core Ideas

Large progeny trials have identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for resistance to vascular streak dieback (VSD) of Theobroma cacao.

New genome technologies permit diploid assemblies and greater scrutiny of parentally inherited chromosomes.

We built the diploid genome of a VSD susceptible progeny of resistant maternal and susceptible paternal trees.

We investigated resistance genes at QTLs and found differences based on parental inheritance.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. Near complete parental assigned chromosomes for cultivated Theobroma cacao

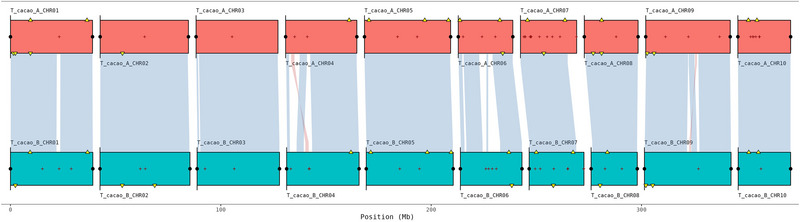

We assembled and parentally phased the chromosomes of a VSD susceptible T. cacao (clone 26), the progeny of a cross between a maternal resistant (S1, haplotype A) with a paternal susceptible (RUQ 1347, haplotype B) tree. All but three inherited chromosomes (two S1, one RUQ 1347) show telomeric caps (black dots in Figure 1). The genomes show few gaps (red plus symbol in Figure 1), high levels of contiguity and completeness, as well as chromosomal synteny (Edwards et al., 2022) based on conserved single‐copy orthologs (Simão et al., 2015). Minor inverted translocations on chromosomes 4 and 9 (pink synteny lines) are likely to be biologically real considering the lack of flanking gaps that would indicate mis‐scaffolding.

FIGURE 1.

Chromsyn (Edwards et al., 2022) synteny plots of T. cacao parentally phased genome, haplotypes A (top) and B (below). Synteny blocks of collinear “Complete” BUSCO genes (Simão et al., 2015) link scaffolds from adjacent assemblies: blue, same strand; red, inverse strand. Yellow triangles mark “Duplicated” BUSCOs. Filled circles mark telomere predictions from Telociraptor (black) (Edwards, 2023). Assembly gaps are marked as dark red + signs.

The phased genomes are both highly complete according to the assessment of conserved single‐copy orthologs and basic statistics (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Raw data statistics from NanoPlot (De Coster & Rademakers, 2023) and genome statistics for both sets of parentally inherited Theobroma cacao chromosomes using Quast and BUSCOs (Gurevich et al., 2013; Simão et al., 2015).

| Raw HiFi data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total bases | 30,259,224,851 | |

| Mean read length | 14,413.4 | |

| Mean read quality | 35.6 | |

| Genome statistic | Haplotype A | Haplotype B |

| Total genome length (bp) | 374,523,129 | 381,631,648 |

| Chromosome length (bp) | 338,223,858 | 340,140,478 |

| No. of chromosomes | 10 | 10 |

| N50 (bp) | 38,945,508 | 39,156,173 |

| L50 | 5 | 5 |

| No. of contigs | 165 | 315 |

| GC (%) | 33.73 | 33.67 |

| BUSCO complete (genome; n = 1,614) | 98.2% | 98.4% |

| Single‐copy | 97.5% | 97.8% |

| Duplicated | 0.7% | 0.6% |

| BUSCO fragmented | 0.6% | 0.9% |

| BUSCO missing | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| Protein‐coding genes (funannotate) | 26,199 | 26,321 |

| NBARCs (FindPlantNLRs annotation) | 342 | 370 |

| NLRs | 293 | 326 |

| TIR‐NLR (TNL) | 11 | 15 |

| Integrated domain (ID) NLRs | 5 | 12 |

| Repeats | 62.0% | 62.4% |

Note: Haplotype A chromosomes derived from maternal plant S1 and haplotype B from paternal plant RUQ 1347. Annotation statistics based on FindPlantNLRs and Funannotate (Chen et al., 2023; Palmer & Stajich, 2023). NLR annotated resistance genes were classified and largely conformed to coiled‐coil class with only small numbers of Toll/interleukin‐1 receptor‐type (TIR) and integrated domain type NLRs.

The goal for genome assemblies of gapless and telomere‐to‐telomere (T2T) chromosomes has recently been achievable with the latest sequencing technologies (Sergey et al., 2022). The resulting genome assemblies permit greater depth in understanding structural and evolutionary biology (Mao & Zhang, 2022). Recently, chromosome‐level genomes for three wild cacao species from the Upper Amazon were made public (Nousias et al., 2024). These provide the first cacao genomes produced using long read sequence technology and indicate an evolutionary divergence, based on conserved orthologs, from cultivated Criollo and Matina reference genomes (Argout et al., 2017, 2011; Motamayor et al., 2013) at ∼1.83 and ∼1.34 million years ago. The wild cacao assemblies represent the collapsed haploid state for genomes and are larger in both chromosome and genome base pair (bp) lengths compared with earlier reference genomes. Each of our parentally phased genome assemblies is comparable in size to the wild cacao, at around 380 Mb; however, we annotated more predicted protein coding genes at around 26,000 (Table 1) compared to around 21,000, and higher percentage of repetitive sequences at 62% compared to 53% (Nousias et al., 2024). We annotated all genes for the predicted nucleotide binding site (NBARC) domain type as well as predicted “complete” NLRs that incorporate NBARC plus leucine‐rich repeat (LRR) domains (Table 1). Of the complete NLRs, we determined only 11 and 15 Toll/interleukin‐1 receptor‐type TNL‐type, and only 5 and 12 novel integrated domains (ID) within NLRs per haplotype.

Despite our efforts to source a VSD‐symptomatic leaf, we were unable to extract sufficient DNA for sequencing and assembly of the pathogen, C. theobromae. On reviewing our pathogen sequence data, as described in the experimental procedures, we determined only 17 reads mapped to the genome for C. theobromae. We confirmed these low sequence results by mapping the reads to a more recent genome for C. theobromae isolated from cassava in Laos (Leiva et al., 2023). Of interest, the C. theobromae infecting cassava was cultured on potato dextrose media, whereas the pathogen causing cacao VSD has not been culturable. Our results show that an alternative approach is required for obtaining sufficient high molecular weight DNA from C. theobromae for complete phased genome assemblies.

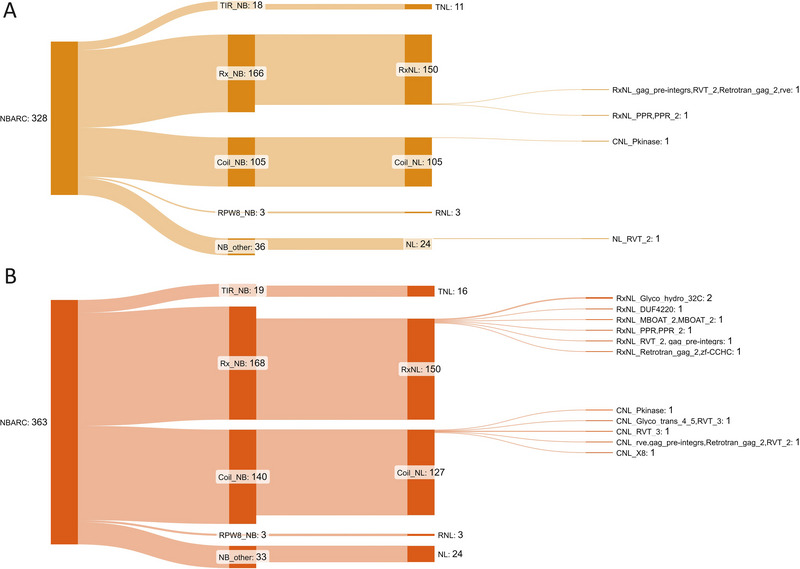

2.2. Low structural diversity of NLRs between Theobroma cacao alleles

The NLR‐type resistance genes were annotated, as described in the experimental procedures, and the parentally inherited chromosomes were compared, noting that haplotype A (red annotations) (Figure 2) aligned with the resistant maternal and haplotype B (yellow annotations) with susceptible paternal trees. We found that the predicted NLR‐type genes varied in quantity and types between the two sets of chromosomes. Of the 342 and 370 predicted genes that contained NBARC domains (Table 1), one of the key identifiers of this class of NLR‐type resistance genes, our research determined a discrepancy of 293 and 326 complete gene models within haplotypes A and B, respectively. Using the web tool version of OrthoVenn3 (Sun et al., 2023) with the OrthoMLC algorithm, using an expect value of 1e‐15 and inflation value 1.5, we found that NLR amino acid sequences clustered into 83 orthologous groups (orthogroups). Of these orthogroups, 82 clusters were shared between the two haplotypes with the largest cluster including 55 proteins, 28 and 27 from haplotypes A and B, respectively. Forty‐four orthogroups contained a single NLR protein from each haplotype, meaning that the matching homolog was present in each assembly. Nevertheless, aligned sequences for homologous proteins showed some variations, and there were also 2.4% single NLRs, numbering 4 and 11 from haplotypes A and B, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Physical locations of predicted NLR genes on the paired chromosomes of Theobroma cacao (A) haplotype A (red) and (B) haplotype B (yellow) generated using ChromoMap (Anand & Rodriguez Lopez, 2022) in RStudio.

2.3. Low numbers of Theobroma cacao NLR‐type genes compared to other tree species

Resistance genes of the NLR‐type are numerous and highly polymorphic both within and between plant species (Van de Weyer et al., 2019). Trees have generally been shown to have higher numbers of NLR‐type genes than herbaceous species, and this is suggested to accommodate a changing pathogen environment over the life of a tree (Tobias & Guest, 2014). More recently, analyses of gene content in diploid genomes have been possible due to advances in sequencing and computational technologies. Notably, tree resistance genes have been investigated within the diploid genome for Melaleuca quinquenervia (S. H. Chen et al., 2023), highlighting variation in numbers (763 and 733) between haplotypes and across chromosomes for this class of gene. Our analysis of the NLR complement within T. cacao showed similar representation to an earlier genome study (Argout et al., 2011) that determined just 297 nonredundant NLR‐type genes. Our work, however, presents the diploid content of NLRs as 293 and 326 for haplotypes A and B, respectively, permitting deeper investigation of homologs at loci. We confirmed low numbers and percentages of the Toll/interleukin‐1 receptor (TIR) NLR class (termed TNLs) of resistance genes within T. cacao (Figure 3) compared to many trees within the Rosid clade, in which they comprise 40%–60% (Arya et al., 2014; Christie et al., 2016; Kohler et al., 2008). This was noted in earlier molecular and genomic studies where only 4% of NLRs contained the TIR domain (Argout et al., 2011; Kuhn et al., 2006), with our classification indicating 3.8% and 5% for haplotypes A and B. Unlike the previous study with PCR primers for molecular markers that found TNLs on chromosomes 3 and 5 (Kuhn et al., 2006), we determined TNLs within clusters on chromosomes 4 (three genes), 5 (two genes), and 6 (three and five genes on haplotypes A and B), plus a single TNL gene on chromosomes 2, 4, and 6 of each haplotype. Our finding of only five and 12 NLR‐type genes with noncanonical integrated domains in the two haplotypes also suggests that this integration is less important as a strategy for pathogen recognition and response in cultivated T. cacao compared to other species (Marchal et al., 2022).

FIGURE 3.

The predicted NLR gene complement in the parentally phased Theobroma cacao genome. The two sets of chromosomes corresponding to (A) haplotypes A and (B) B were independently classified (S. H. Chen et al., 2023) and visualized to present the domain classes using SankeyMatic (Bogart, 2014), including novel integrated domains (IDs) with abbreviations derived from the Pfam database (Mistry et al., 2021). CC, coil–coil domain; NBARC, nucleotide binding domain; RPW8, resistance to powdery mildew 8‐like coiled‐coil; Rx, Potato CC‐NB‐LRR protein Rx; TIR, Toll/interleukin‐1 receptor.

2.4. Theobroma cacao NLR‐type genes are present and polymorphic in proximity to QTLs for VSD resistance

Informative QTL regions were investigated for resistance gene homologs across the parental inherited chromosomes. Based on our analysis, the most closely aligned VSD QTLs between PNG and Sulawesi T. cacao progeny trials were on chromosomes 3 and 8 (Table 2). We checked these regions based on our annotations for NLRs and identified an NLR cluster at around 27 Mb and 29 Mb on chromosome 3 within both parentally inherited alleles. The location matches within our calculated regions based on the reversed start position for the cM QTL (Table 2). The NLR sequences from 27 Mb were exact homologs except for a short region from the last 60 nucleotides of the LRR (g929.t1 and g1196.t1). When we aligned the four gene sequences for the NLRs from 29 Mb (g2393.t1, g782.t1, g2391.t1, g779.t1) with ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994) and visualized in BioEdit (Hall, 1991), we see close homology across the cluster but SNPs and indels are evident (Figure 4, A). When investigating the translated coding sequences, these variants cause frameshifts and non‐synonymous mutations and may therefore be functionally informative. We found an NLR cluster of three genes on chromosome 8 at around 3.8 Mb, which falls within the 2 cM interval specified by Singh (2021) of 2–4 Mb from the QTL midpoint. The NLR cluster formed two orthogroups, one group of two head‐to‐head Rx‐NLR predicted proteins from each haplotype (g1318.t1, g1320.t1 and g3681.t1, g3683.t1) and the other of single, nearly exactly homologous proteins, with one amino acid variant, namely proline (g1316.t1, haplotype A) to arginine (g3679.t1, haplotype B). Between the region 27–36 kb on chromosome 9, we determined four NLRs from haplotypes A and B. Paired gene homologs around 31 Mb on chromosome 9 were aligned (g3078.t1 and g3828.t1) and show SNPs that appear as five non‐synonymous amino acid mutations within the translated coding sequences (Figure 4, B).

TABLE 2.

Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for vascular streak dieback (VSD) resistance were calculated using average Theobroma cacao linkage group (LG) lengths (Epaina, 2012) and dividing chromosome lengths (bp) by LG lengths (in cM) to determine 1 cM in bp (per chromosome).

| Theobroma cacao A (S1 inherited) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomes (LG) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| cM (average) | 99.9 | 107.2 | 91.6 | 79.7 | 89.8 | 75.8 | 56.6 | 60 | 106.1 | 62.4 | |

| bp per chromosome (this study) | 39,005,981 | 41,965,441 | 38,945,508 | 33,857,508 | 40,959,067 | 25,938,454 | 26,721,266 | 25,579,687 | 40,159,845 | 25,091,101 | |

| bp per cM | 390,450 | 391,469 | 425,169 | 424,812 | 456,114 | 342,196 | 472,107 | 426,328 | 378,509 | 402,101 | |

| SSR BLAST (bp) | 9,150,264 | 8,422,934 | a 24,936,286 | 29,469,565 | 6,342,946 | 5,663,668 | 17,544,725 | ||||

| Singh (2021) | VSD QTL (bp) | 24,936,286 | 9,353,725 ( b 29,591,783) | 8,782,359 | 25,170,874 | ||||||

| Epaina (2012) | VSD QTL (bp) | 11,270,737 | 26,861,405 | 8,531,872 ( b 30,413,636) | 27,163,747 | 7,976,071 | 18,514,151 (b 7,065,536) | 31,452,994 | |||

| Epaina (2012) | PPR QTL (bp) | 8,531,872 ( b 30,413,636) | 23,158,620 | 6,937,499 | 18,514,151 ( b 7,065,536) | ||||||

| Theobroma cacao B (RUQ1347 inherited) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomes (LG) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| bp per chromosome (this study) | 39,156,173 | 42,761,000 | 39,170,102 | 34,430,140 | 41,360,500 | 29,284,707 | 25,927,970 | 21,951,902 | 41,168,245 | 24,929,739 | |

| bp per cM | 391,954 | 398,890 | 427,621 | 431,997 | 460,585 | 386,342 | 458,091 | 365,865 | 388,014 | 399,515 | |

| SSR BLAST hit (bp) | 9,029,444 | 8,422,195 | 25,194,781 | 29,860,574 | 6,481,531 | 5,634,604 | c 17,636,093 | ||||

| Singh (2021) | VSD QTL (bp) | 9,407,666 ( b 29,762,436) | 7,536,820 | 25,802,906 | |||||||

| Epaina (2012) | VSD QTL (bp) | 11,314,135 | 27,370,630 | 8,581,075 ( b 30,589,027) | 27,623,167 | 8,054,243 | 15,888,421 ( b 6,063,481) | 32,242,768 | |||

| Epaina (2012) | PPR QTL (bp) | 8,581,075 ( b 30,589,027) | 23,550,302 | 7,005,492 | 15,888,421 ( b 6,063,481) | ||||||

Note: QTLs (cM) were then multiplied by bp length for 1 cM to obtain the chromosome locations for the diploid genome. VSD QTL locations were compared using local BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) with primers for nearest simple sequence repeats (SSR) (Table 5.3.4, Epaina, 2012). Green cells = VSD and Brown cells = Phytophthora pod rot (PPR) resistance informative QTL physical locations on chromosomes.

aReverse SSR primer blast match only.

bQTL determined with start position on chromosome reversed.

cForward SSR primer blast match only.

FIGURE 4.

Subregions of gene sequence alignment of an NLR cluster matching the quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapped regions at around 29 Mb on chromosome 3 (A) and of single NLR homologs at 31 Mb on chromosome 9 (B) within both parentally inherited alleles, A and B, for Theobroma cacao clone 26. Yellow boxed regions indicate SNPs and indels that lead to amino acid changes in predicted coding regions. All predicted NLRs are annotated as Rx‐NLRs (S. H. Chen et al., 2023) named for resistance to potato virus X.

The QTLs on chromosomes 3 and 8 accounted for 11% and 15% phenotypic variance in the Sulawesi progeny trials (Singh, 2021) and were informative for VSD and PPR resistance in the PNG trial (Epaina, 2012) (2). The chromosome 9 QTL accounted for 16%–18% phenotypic variance in the Sulawesi trial. All putative resistance genes around QTLs were annotated as Rx NLR‐type resistance genes. The Rx‐NLR coded protein from potato (Solanum tuberosum) has long been identified as conferring resistance to the potato virus X by direct recognition (Kohm et al., 1993). Recent work has clarified the interaction of sensor Rx‐NLRs with downstream helper NLR protein oligomerization (Contreras et al., 2023), showing a distinct mechanism for immune responses in plants. While our work has uncovered the arrangement and sequence differences of predicted Rx‐NLR clusters around QTLs for resistance to VSD, further confirmation of these variants is needed across multiple progenies that have clear phenotypes for resistance/susceptibility. Amplification of DNA regions around these clusters will provide additional clarity but was beyond the scope of the current study. Functional validation would also be beneficial to determine mechanisms of recognition and response, as it is known that paired head to head NLRs, as we identified on chromosome 8, can determine resistance to more than one pathogen (Xi et al., 2022), potentially explaining the results from the study conducted in PNG.

2.5. Annotation statistics show high homology between allelic pairs in Theobroma cacao

The orthology of all annotated proteins was analyzed with OrthoVenn3 as described previously. The predicted proteins indicated 22,486 shared clusters, of which 21,800 included a single predicted homologous gene from each haplotype. The largest cluster had 44 predicted proteins and there were 9.76% singletons. In total, there are 2928 (2896), 1865 (1798), and 3278 (3315) predicted genes for haplotype A (and B) on chromosomes 3, 8, and 9, respectively. Except for chromosome 9, with around 76 predicted genes within ∼2 Mb of the QTL informing resistance to VSD, the locations on chromosomes 3 and 8 are in highly dense gene‐encoding regions, with 325 and 370 predicted genes.

We investigated the predicted genes around the QTLs and found that homologs were present between haplotypes (Table 3). We reviewed the predicted protein functions based on Pfam database (Mistry et al., 2021) annotations within proximity of NLRs that corresponded to QTLs. Around the predicted QTL for resistance to VSD on chromosome 3, an Rx‐NLR gene cluster is interspersed with two predicted genes coding for protein kinases (Table 3). In T. cacao, these predicted receptor‐like kinases (RLK) have transmembrane motifs and fused LRR domains indicating a putative role in response to perturbation and defense (Jose et al., 2020). A BLAST of the T. cacao predicted RLK amino acid sequence against the NCBI database showed a close match with a predicted Gossypium arboretum receptor kinase‐like protein Xa21. This class of RLK has been well studied in crop plants, notably in rice, where Xa21 confers resistance to Xanthomonas sp. and multiple other pathogens (Ercoli et al., 2022). The finding of RLKs so closely associated with the Rx‐NLR genes on chromosome 3 in both parental alleles, close to the predicted region for VSD resistance QTL, suggests a potential role in disease response and a target for further research. The NLR QTL regions on chromosomes 8 and 9 have no associated RLKs; however, it is likely that multiple genes are involved in the VSD resistance response observed.

TABLE 3.

Predicted and annotated genes that are in proximity to the quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for resistance to Ceratobasium theobromae, causal agent of vascular streak dieback in cultivated Theobroma cacao.

| Haplotype A | Haplotype B | Pfam ID | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLR QTL chromosome 3 (40 kb region) | |||

| V9T21_008377 | WDX93_008321 | PF00334 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase |

| V9T21_008378 | WDX93_008322 | PF01625 | Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase |

| V9T21_008380 | WDX93_008324 | PF07714 | Protein tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase |

| V9T21_008380 | WDX93_008324 | PF13855 | Leucine‐rich repeat |

| V9T21_008382 | WDX93_008326 | PF07714 | Protein tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase |

| V9T21_008382 | WDX93_008326 | PF13855 | Leucine‐rich repeat |

| V9T21_008382 | WDX93_008326 | PF08263 | Leucine‐rich repeat N‐terminal domain |

| V9T21_008383 | WDX93_008327 | PF02298 | Plastocyanin‐like domain |

| NLR QTL chromosome 8 (10 kb region) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| V9T21_020396 | WDX93_020310 | PF00745 | Glutamyl‐tRNAGlu reductase, dimerisation domain |

| V9T21_020396 | WDX93_020310 | PF01488 | Shikimate/quinate 5‐dehydrogenase |

| V9T21_020397 | WDX93_020311 | PF01293 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase |

| V9T21_020399 | WDX93_020313 | PF08694 | Ubiquitin‐fold modifier‐conjugating enzyme 1 |

| V9T21_020401 | WDX93_020315 | PF12295 | Symplekin tight junction protein C terminal |

| V9T21_020401 | WDX93_020315 | PF11935 | Symplekin/PTA1 N‐terminal |

| V9T21_020402 | WDX93_020316 | PF11935 | Symplekin/PTA1 N‐terminal |

| V9T21_020404 | WDX93_020318 | PF00719 | Inorganic pyrophosphatase |

| NLR QTL chromosome 9 (3 kb region) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| V9T21_023576 | WDX93_023431 | PF00514 | Armadillo/beta‐catenin‐like repeat |

| V9T21_023578 | WDX93_023433 | PF02341 | RbcX protein |

| V9T21_023579 | WDX93_023434 | PF00076 | RNA recognition motif |

Note: The genomes are available at NCBI: PRJNA1083235 and PRJNA1086984 and annotation data at: https://zenodo.org/records/12195204.

3. CONCLUDING REMARKS

A recent study, using single nucleotide polymporphisms, confirmed low genetic diversity due to selection for domestication in cultivated cacao (Orduña et al., 2024). The results of that work may explain why similar loci are apparent across varieties for resistance to different diseases, as was found in the two studies, in Indonesia and in PNG, that informed the current research. Genome resources have, until recently, been presented as collapsed haploid genomes, and the allocation of QTLs has been limited due to the loss of valuable information from the two allele sets. Technologies are rapidly improving and permitting far more detailed comparative studies than were possible only a few years ago. Our original goal of assembling both the host and compatible pathogen genomes from one sample was unsuccessful due to low sequence coverage for C. theobromae reads. However, future methods could optimize the sampling and use adaptive sequencing with the Oxford Nanopore Technologies metagenome sampling tools (Martin et al., 2022). This approach is rapidly developing, with new models incorporating Bayesian dynamic adaptive sampling (Weilguny et al., 2023) and providing promising tools to investigate the biology of unculturable biotrophic pathogens.

For this research, we employed recent advances in technology and software to assemble and assign parental chromosomes for a VSD susceptible T. cacao genotype (clone 26) from the Mars Cocoa Research Centre in Pangkep, Sulawesi, Indonesia. We annotated the two parental chromosome sets independently and characterized all the predicted NLR‐type resistance genes. The resulting curated and annotated genomes were compared at QTL locations that were identified to explain resistant phenotypes to VSD and PPR. Our results show that some QTLs may indeed resolve to NLR‐type resistance genes and parentally inherited allelic variants could be investigated for breeding trees with resistance to VSD, PPR, and potentially other diseases of cacao. Interestingly, the primers around QTL markers for resistance were not present in all the parental chromosomes, indicating possible genetic variations controlling phenotype. Specifically, we detected no BLAST match for SSR primers at QTLs for chromosome 3 in the S1 (resistant) and for chromosome 9 in RUQ 1347 (susceptible) inherited alleles. Our work provides a comprehensive analysis of the predicted NLRs and other genes on each chromosome and shows the variation in structure and type of these genes within a VSD‐susceptible individual.

Future work could develop molecular screening around these specific genes across both resistant and susceptible trees for a range of diseases of cacao. The current work has developed foundational genome resources to facilitate such analyses that may be used to assist future breeding programs for resistance.

3.1. Experimental procedures

3.1.1. High‐molecular weight DNA extraction protocol testing

Prior to our work in Sulawesi, Indonesia, we ran exhaustive high molecular weight (HMW) DNA extraction protocol testing on cacao leaf samples from plants maintained in the University of Sydney greenhouses. A persistent problem remained for clean extractions due to high contaminant levels that had the properties of a jelly‐like substance, presumably pectin, though not confirmed. We attempted to resolve the nature of the contaminant with enzymatic testing using pectinase. We also tested our contaminant DNA with nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer (NMR). Data were collected on a 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with triple resonance CryopProbe and the following buffer conditions: 10 mM Tris; 10% D2O; pH 8.0, in 3 mm short NMR tubes (volume ∼160 µL). We ran controls of 10 mM Tris buffer and clean HMW DNA in Tris buffer. Test samples included pectin, pectin with pectinase treatment, contaminated DNA with pectinase treatment, and contaminated DNA with macerozyme (incl. pectinase) treatment. Unfortunately, the signals in the aromatic/amide regions were beyond detection, suggesting a large DNA‐contaminant (potentially covalent) complex form in this sample. Young leaves were found to produce cleaner DNA but did not show any symptoms of VSD, so we aimed to extract samples from older infected leaves using a combined protocol described below that improved on but did not resolve the contaminant problem.

3.1.2. Cacao leaf material collected from field trial tree

We collected fully expanded leaf material on January 10, 2023, during wet weather, from the Mars Cocoa Research Institute field trials in Pangkep, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The leaves were found on T. cacao F1 generation progeny, VSD susceptible clone number 26, from Sulawesi 1 to S1 (resistant maternal), crossed with RUQ 1347 (MIS_GBR207 CCN 51) (susceptible paternal) parental plants (Turnbull et al., 2017). The leaves were symptomatic of VSD with browning of the leaf apex and vascular death visible in the petiole (Figure 5). Leaves were placed in plastic bags and transported to the laboratories at Universitas Hasannudin, Makassar, and refrigerated overnight.

FIGURE 5.

Leaf from Theobroma cacao, VSD susceptible clone 26, growing at the Mars Cocoa Research Institute field trials, Pangkep, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. (Left) The symptomatic leaf apex dieback and some chlorosis indicating Ceratobasidium theobromae. (Right) Visible vascular death caused by the pathogen. Scale bar left ∼5 cm.

3.1.3. High molecular weight DNA extracted from cacao leaves

The following day while leaves were fresh, HMW DNA was extracted using a protocol adapted from the sorbitol wash method developed by A. Jones et al. (2021) and the HMW plant DNA CTAB extraction method developed by Hilario (2018). Small (1 cm2) pieces of the leaf lamina were placed into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes with a small amount (a few mg) of PVP40000. The tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into a powder with micropestle while frozen. We attempted to grind midrib tissue to extract the pathogen DNA but found it too tough and fibrous. Three or more rounds of sorbitol wash were used on the samples, in accordance with the protocol (A. Jones et al., 2021), until the supernatant was no longer viscous. Then DNA was extracted, according to the protocol (Hilario, 2018), using CTAB buffer with an incubation step at 56°C for 2 h in a water bath. Apart from an extended RNase A incubation step of 10 min, the protocol was followed until the precipitation step. The DNA formed a visible gelatinous precipitate at this stage and was left to continue precipitating at ‐20°C overnight. The following day, the DNA was collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 25 min at room temperature, and cleanup steps followed according to the protocol before dissolving in 10 mM Tris‐HCL pH 8.0. The DNA was quantified, and purity was checked using a NanoDrop Lite Plus spectrophotometer and a QuBit 2.0 Fluorometer. Purified HMW DNA (10 × 1.5‐µL tubes) was couriered under an Australian Department of Agriculture, Water, and the Environment import permit to the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF), Brisbane, Australia, for cleanup, size selection, library prep, and sequencing on Pacific Biosciences of California, Inc. (PacBio) Sequel II.

3.1.4. Formaldehyde cross‐linking of leaves for HiC sequencing

We prepared samples according to the manufacturer's protocols for chromatin crosslinking library prep and sequencing at Phase Genomics to obtain HiC reads. Total 5 g of leaf material was immersed in 2% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 2 min for surface sterilization and then washed with ultrapure water. The leaves were cut into strips and immersed in 1% (v/v) formaldehyde for 40 min with intermittent mixing. The crosslinking reaction was quenched with the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM for 15 min. The crosslinked leaves were washed with ultrapure water, dried, and then ground to a powder after freezing with liquid nitrogen.

3.1.5. Data processing and genome assembly

Details of all the software, versions, parameters, and scripts used to process the data are available at: https://github.com/peritob/Theobroma‐cacao‐genome/tree/main.

3.1.6. Preparing the raw data for processing

We downloaded the 23 GB (ccs.bam) HiFi sequence read data from AGRF, filtered the reads using HiFiAdapterFilt (Sim et al., 2022), and checked the statistics using Nanoplot (De Coster & Rademakers, 2023). The HiC paired‐end read (25 GB) mapping statistics against the cacao Criollo reference genome (GCF_000208745.1) were good for informative read pairs (12.18%) but not against the pathogen genome (GCA_012932095.1) at (0.03%), although 4.28% same strand high‐quality reads were mapped. We mapped all the filtered HiFi reads to the C. theobromae genome (Ali et al., 2019) with Minimap2 (Li, 2018) to filter the pathogen from the host. We presumed all the mapped reads to be pathogen and all the unmapped reads to be from the host and proceeded accordingly. Additionally, we ran a local blast with internal transcribed spacer (ITS) primers on the VSD‐mapped raw sequence reads. This confirmed a partial (13/17 base match) in silico hit using the ITS regions using forward primers ITS4 (White et al., 1990) and reverse ITS5A (Stanford et al., 2000). We later reviewed reads that mapped to the pathogen genome and determined that 2957 of the 2974 reads mapped to a single region on SSOP01001218.1 of C. theobromae genome assembly ASM907832v1. When we checked the NCBI BLAST top‐hit for this region, it matched the sequence for plant chloroplast. We then mapped our reads to the T. cacao chloroplast (NC_014676.2) and verified that all but 17 reads mapped. The C. theobromae scaffold therefore contains a region of chloroplast sequence, likely the RuBisCO rbcL gene, explaining our problems in assembling the pathogen data. The reads were also mapped to a newer genome for C. theobromae isolated from cassava in Laos (GCA_037974915.1) (Leiva et al., 2023) and this also resulted in 17 mapped reads. Raw Illumina data available for the parental plants was trimmed of adaptors and low‐quality reads with Fastp (S. Chen et al., 2018).

3.1.7. Genome assembly and chromosome scaffolding

We attempted several assembly approaches with Hifiasm software (Cheng et al., 2021). Previous experience with HiC scaffolding has shown the possibility to phase the separate nuclear compartments (Tobias et al., 2022). We therefore attempted to build a plant‐pathogen hybrid genome to scaffold with HiC and visually identify and separate the two organisms using the heatmaps. The hybrid genome was not complete, likely due to insufficient overlaps for the pathogen reads. We tried to assemble all the pathogen reads into consensus sequences using Flye (Kolmogorov et al., 2019) and Hifiasm without success. We then tested the trio‐binning option for Hifiasm of the diploid T. cacao incorporating the Illumina parental reads after running Yak (Li, 2020). This was unsuccessful, so we assembled the diploid T. cacao genome using HiC integration with Hifiasm followed by HiC scaffolding of the resulting genomes independently with Juicer (Durand, Shamim, et al., 2016), 3D‐DNA (Dudchenko et al., 2017), and manual scaffolding with Juicebox (Durand, Robinson, et al., 2016).

3.1.8. Theobroma cacao genome curation

We used the Matina 1–6 cacao genome (GCF_000403535.1) to anchor our genome scaffolds with PAFScaff (Field et al., 2020) based on Minimap2 (Li, 2018) mapping. We screened the resulting fasta files for nonnuclear genomic contaminants with FCS‐GX (Astashyn et al., 2024) and Tiara (Karlicki et al., 2022). In each case, the two haplotypes were run independently. FCS‐GX was run against the NCBI gxdb (build date January 24, 2023; downloaded September 12, 2023). Additional checks of contamination were executed with Taxolotl (Tobias et al., 2022). Taxolotl was provided with the annotation for each haplotype and run with taxwarnrank = class using mmseqs2 against the NCBI nr database (compiled May 19, 2022). In addition to generating results for all sequences in each haplotype, analysis of subsets was performed for (1) chromosome scaffolds only, (2) pure FCS‐GX scaffolds, (3) contaminated FCS‐GX scaffolds, (4) Tiara “eukarya” scaffolds, and (5) scaffolds not classified as “eukarya” by Tiara. Results were visualized with Pavian. Lists were made of non‐plant contaminant contigs from the fcs_gx_reports and were removed, as well as plastid contigs flagged in the tiara outputs. We then ran Telociraptor (Edwards, 2023) followed by Chromsyn (Edwards et al., 2022) on the chromosome‐level contigs to compare synteny and scaffolds tweaked according to the contig graphs and figure outputs. We used the parental data available within our lab (Singh, 2021) to assign scaffolds and contigs. We mapped the maternal S1 data to the concatenated haplotypes A and B genomes using Hisat2 (Kim et al., 2019) and then similarly mapped the RUQ 1347 data. We assumed that the most reads mapped were the likely parental chromosome/contig and curated each genome. Of the chromosomes, 3, 5, and 8 were switched accordingly (Figure 6). We designated the S1 maternally inherited contigs as genome T_cacao_v1.3_A, and RUQ 1347 paternally inherited as T_cacao_v1.3_B.

FIGURE 6.

Theobroma cacao–resistant (S1) and –susceptible (RUQ 1347) parental paired‐end (PE) Illumina sequence reads mapped to the concatenated Hap A and B progeny chromosomes. The reads that were mapped in greater numbers to chromosomes and contigs were used to determine parental assignment and swapped accordingly.

3.1.9. Parental assigned genomes were annotated independently

To repeat mask the genome for annotation, we ran both genomes through Repeatmasker and Repeatmodeler. We then mapped publicly available RNAseq data from CCN51 T. cacao from NCBI (PRJNA933172) to the soft‐masked genomes independently with hisat2. We trimmed the RNAseq data with Fastp (S. Chen et al., 2018) prior to mapping and processed the outputs with Samtools (Li et al., 2009) to make bam files. The mapped RNAseq bam files were used as evidence to predict protein coding genes within the funannotate (Palmer & Stajich, 2023) predict pipeline with the BUSCO embryophyte (Manni et al., 2021; Simão et al., 2015) database. We used Interproscan5 (P. Jones et al., 2014) independently and then ran funannotate annotate to obtain final predicted proteins and coding sequences. In order to make GenBank (Sayers et al., 2023) compatible annotations, we ran the resulting files with Table2asn (GenBank, 2023).

3.1.10. NLR‐type resistance gene annotation

We annotated the resistance gene complement with the FindPlantNLRs pipeline (S. H. Chen et al., 2023), which incorporates NLR‐Annotator (Steuernagel et al., 2020), HMMER (Finn et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2010), and BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) components as well as Interproscan5 (P. Jones et al., 2014). Unlike many annotation methods, the pipeline takes an unmasked genome as a starting point to avoid masking, and hence not annotating, repetitive LRR regions that are characteristic of NLR‐type genes. The last stage of the pipeline determines NLR gene classes, including predicted integrated domains, and locations within each parental haplotype. All NLRs were plotted to visualize on chromosomes with Chromomap (Anand & Rodriguez Lopez, 2022), and classes based on domain Pfams were visualized with Sankeymatic (Bogart, 2014).

3.1.11. QTL locations on chromosomes predicted and compared against NLR‐type gene predictions

Informative QTLs for resistance to VSD were obtained from data of two previous studies (Epaina, 2012; Singh, 2021). Using the chromosome lengths for our parental genome haplotypes, we calculated the predicted locations for VSD resistance QTLs. In brief, we took averages of Linkage Group (LG) map lengths (Epaina, 2012) and divided the chromosome base pair length from assembled genomes (current study) by centimorgan (cM). We then determined the expected midpoint (in base pairs) for the resistance QTLs. Singh (2021) predicted QTL confidence intervals at 3–4 Mb and determined three significant QTLs on chromosomes 3, 8, and 9. Initially, our calculations for the QTL locations from the PNG progeny study showed a significant region at around 18.5 Mb on chromosome 8 (Table 2). This was not concordant with the Sulawesi study, at between 5.5 and 8.8 Mb, leading us to investigate if our calculations were misrepresenting the “start” position for chromosome 8. When recalculated based on the reverse orientation, we found that the QTL matched more closely, at around 7 Mb. We also noted that the QTL identified on chromosome 3, when start positions were reversed, indicated a cluster of NLR‐type genes at around 30 kb. Additional to these methods, we used a local nucleotide basic local sequence alignment (BLAST) (Altschul et al., 1990) with primers for the nearest QTL SSR markers noted in the PNG study (tab. 5.3.4, Epaina, 2012). The discrepancy between the physical map locations using blast and calculations based on average cM distance in base pairs is around 4–6 Mb, except for chromosome 9, where the difference was greater. Several significant QTLs were associated with resistance to other pathogens including PPR (Table 2) in the study by Epaina (2012). QTLs that were in similar regions within both studies were regarded as likely harboring useful candidate genes for breeding resistance. The most closely aligned VSD QTLs between studies were on chromosomes 3, 8, and 9. As the cM markers were not evenly spaced across the physical map, we checked the loci using a local BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) with simple sequence repeats (SSR) marker primers for VSD QTLs (tab. 5.3.4, Epaina, 2012). The primer exact match was within 2–3 Mbp of our calculated QTLs for chromosome 8, within both parental alleles. Only the reverse primer for the SSR marker had a match on chromosome 3 for haplotype A, and the physical location was ∼25 Mbp compared to ∼29 Mbp for our calculations. The SSR primer blast match on chromosome 9 was not within the same calculated region, at ∼18 Mbp, and primers only matched exactly within haplotype A. Therefore, the exact matches with VSD QTL SSR primers were only present on chromosomes 8 and 9 for haplotype A (S1‐resistant parent alleles) and for chromosomes 3 and 8 for haplotype B (RUQ1347‐susceptible parent alleles). While SSR blast hits do not exactly match with these NLR physical map locations, we reasoned that the allelic variance seen within proximity to the QTL may be of interest for further investigation, particularly where primer hits showed differences across parental alleles. Detailed comparisons for the VSD significant QTLs across the two studies were undertaken to investigate resistance gene homologs and other predicted genes across the parental chromosomes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Peri A. Tobias: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing—original draft. Jacob Downs: Formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing—review and editing. Peter Epaina: Formal analysis; resources; writing—review and editing. Gurpreet Singh: Formal analysis; resources; writing—review and editing. Robert F. Park: Writing—review and editing. Richard J. Edwards: Data curation; writing—review and editing. Eirene Brugman: Methodology; writing—review and editing. Andi Zulkifli: Methodology; writing—review and editing. Junaid Muhammad: Project administration; resources; writing—review and editing. Agus Purwantara: Project administration; resources; writing—review and editing. David I. Guest: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration; supervision; writing—review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Joint Cocoa Research Fund and European Cocoa Association supported this research, and the VSD susceptible Theobroma cacao clone is growing at the Mars Cocoa Research Institute in Pangkep, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The authors acknowledge the facilities, and the scientific and technical assistance of the Sydney Informatics Hub at the University of Sydney and access to the high‐performance computing facility Artemis. We acknowledge the support of Sydney Analytical for running samples and interpretation on the University of Sydney Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Core Facilities. Thank you to Mark Powrie who generously assisted during the work in Sulawesi.

Tobias, P. A. , Downs, J. , Epaina, P. , Singh, G. , Park, R. F. , Edwards, R. J. , Brugman, E. , Zulkifli, A. , Muhammad, J. , Purwantara, A. , & Guest, D. I. (2024). Parental assigned chromosomes for cultivated cacao provides insights into genetic architecture underlying resistance to vascular streak dieback. The Plant Genome, 17, e20524. 10.1002/tpg2.20524

Assigned to Associate Editor David Edwards.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data that support the findings of this research are publicly available. Raw data are available at National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the following biosample accession: SAMN40241783 and bioproject accession: PRJNA1083235. Theobroma cacao (clone 26) genomes are available here: PRJNA1083235 (maternally inherited), PRJNA1086984 (paternally inherited). This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accessions JBEWUL000000000 and JBEWUM000000000. NLR predicted coding and amino acid sequences and gff3 data are available at: https://github.com/peritob/Theobroma‐cacao‐genome/tree/main. Diploid genome fasta, annotation gff3 and protein prediction tsv files are available from zenodo at: https://zenodo.org/records/12195204.

REFERENCES

- Ali, S. S. , Asman, A. , Shao, J. , Firmansyah, A. P. , Susilo, A. W. , Rosmana, A. , Mcmahon, P. , Junaid, M. , Guest, D. , Kheng, T. Y. , Meinhardt, L. W. , & Bailey, B. A. (2019). Draft genome sequence of fastidious pathogen Ceratobasidium theobromae, which causes vascular‐streak dieback in Theobroma cacao . Fungal Biology and Biotechnology, 6, Article 14. 10.1186/s40694-019-0077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S. F. , Gish, W. , Miller, W. , Myers, E. W. , & Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology, 215, 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, L. , & Rodriguez Lopez, C. M. (2022). ChromoMap: An R package for interactive visualization of multi‐omics data and annotation of chromosomes. BMC Bioinformatics, 23, Article 33. 10.1186/s12859-021-04556-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argout, X. , Martin, G. , Droc, G. , Fouet, O. , Labadie, K. , Rivals, E. , Aury, J. M. , & Lanaud, C. (2017). The cacao Criollo genome v2.0: An improved version of the genome for genetic and functional genomic studies. BMC Genomics, 18, Article 730. 10.1186/s12864-017-4120-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argout, X. , Salse, J. , Aury, J.‐M. , Guiltinan, M. J. , Droc, G. , Gouzy, J. , Allegre, M. , Chaparro, C. , Legavre, T. , Maximova, S. N. , Abrouk, M. , Murat, F. , Fouet, O. , Poulain, J. , Ruiz, M. , Roguet, Y. , Rodier‐Goud, M. , Barbosa‐Neto, J. F. , Sabot, F. , … Lanaud, C. (2011). The genome of Theobroma cacao . Nature genetics, 43, 101–108. 10.1038/ng.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya, P. , Kumar, G. , Acharya, V. , & Singh, A. K. (2014). Genome‐wide identification and expression analysis of NBS‐encoding genes in Malus x domestica and expansion of NBS genes family in Rosaceae. PLoS One, 9, e107987. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astashyn, A. , Tvedte, E. S. , Sweeney, D. , Sapojnikov, V. , Bouk, N. , Joukov, V. , Mozes, E. , Strope, P. K. , Sylla, P. M. , Wagner, L. , Bidwell, S. L. , Brown, L. C. , Clark, K. , Davis, E. W. , Smith‐White, B. , Hlavina, W. , Pruitt, K. D. , Schneider, V. A. , & Murphy, T. D. (2024). Rapid and sensitive detection of genome contamination at scale with FCS‐GX. Genome Biology, 25, Article 60. 10.1186/s13059-024-03198-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, B. A. , & Meinhardt, L. W. (Eds.). (2016). Cacao diseases: A history of old enemies and new encounters. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Barragan, A. C. , & Weigel, D. (2020). Plant NLR diversity: The known unknowns of Pan‐NLRomes A brief history of plant NLRs. The Plant Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman, J. (2022). Vascular streak dieback of redbud: What plant pathologists know so far. Purdue University Extension. https://www.hriresearch.org/vascular-streak-dieback-update [Google Scholar]

- Bhunjun, C. S. , Phillips, A. J. L. , Jayawardena, R. S. , Promputtha, I. , & Hyde, K. D. (2021). Importance of molecular data to identify fungal plant pathogens and guidelines for pathogenicity testing based on Koch'S postulates. Pathogens, 10, 1096. 10.3390/pathogens10091096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart, S. (2014). SankeyMatic. https://sankeymatic.com/build/

- Chen, S. , Zhou, Y. , Chen, Y. , & Gu, J. (2018). Fastp: An ultra‐fast all‐in‐one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics, 34, i884–i890. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. H. , Martino, A. M. , Luo, Z. , Schwessinger, B. , Jones, A. , Tolessa, T. , Bragg, J. G. , Tobias, P. A. , & Edwards, R. J. (2023). A high‐quality pseudo‐phased genome for Melaleuca quinquenervia shows allelic diversity of NLR‐type resistance genes. GigaScience, 12, giad102. 10.1093/gigascience/giad102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. , Concepcion, G. T. , Feng, X. , Zhang, H. , & Li, H. (2021). Haplotype‐resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods, 18, 170–175. 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie, N. , Tobias, P. A. , Naidoo, S. , & Külheim, C. (2016). The Eucalyptus grandis NBS‐LRR gene family: Physical clustering and expression hotspots. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, Article 1238. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, M. P. , Pai, H. , Tumtas, Y. , Duggan, C. , Yuen, E. L. H. , Cruces, A. V. , Kourelis, J. , Ahn, H.‐K. , Lee, K.‐T. , Wu, C.‐H. , Bozkurt, T. O. , Derevnina, L. , & Kamoun, S. (2023). Sensor NLR immune proteins activate oligomerization of their NRC helpers in response to plant pathogens. The EMBO Journal, 42, e111519. 10.15252/embj.2022111519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daymond, A. J. , Mendez, D. G. , Hadley, P. , Bastide, P. , Abdoellah, S. , Acheampong, K. , Amores‐Puyutaxi, F. M. , Anhert, D. , & Konan, D. C. (2022). A global review of cocoa farming systems . International Cocoa Organisation (ICCO) and the Swiss Foundation of the Cocoa and Chocolate Economy. https://research.reading.ac.uk/cocoa/projects/a‐global‐review‐of‐cocoa‐farming‐systems/ [Google Scholar]

- De Coster, W. , & Rademakers, R. (2023). NanoPack2: Population‐scale evaluation of long‐read sequencing data. Bioinformatics, 39, btad311. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btad311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudchenko, O. , Batra, S. S. , Omer, A. D. , Nyquist, S. K. , Hoeger, M. , Durand, N. C. , Shamim, M. S. , Machol, I. , Lander, E. S. , Aiden, A. P. , & Aiden, E. L. (2017). De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi‐C yields chromosome‐length scaffolds. Science, 356, 92–95. 10.1126/science.aal3327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand, N. C. , Robinson, J. T. , Shamim, M. S. , Machol, I. , Mesirov, J. P. , Lander, E. S. , & Aiden, E. L. (2016). Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi‐C contact maps with unlimited zoom tool. Cell Systems, 3, 99–101. 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand, N. C. , Shamim, M. S. , Machol, I. , Rao, S. S. P. , Huntley, M. H. , Lander, E. S. , & Aiden, E. L. (2016). Juicer provides a one‐click system for analyzing loop‐resolution Hi‐C experiments. Cell Systems, 3, 95–98. 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. J. (2023). Telociraptor . GitHub. https://github.com/slimsuite/telociraptor [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. J. , Dong, C. , Park, R. F. , & Tobias, P. A. (2022). A phased chromosome‐level genome and full mitochondrial sequence for the dikaryotic myrtle rust pathogen, Austropuccinia psidii . BioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.04.22.489119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epaina, P. (2012). Identification of molecular markers and quantitative trait loci linked to resistance to vascular streak dieback and phytophthora pod rot of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.). The University of Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Ercoli, M. F. , Luu, D. D. , Rim, E. Y. , Shigenaga, A. , Araujo, A. T. , Chern, M. , Jain, R. , Ruan, R. , Joe, A. , Stewart, V. , & Ronald, P. (2022). Plant immunity: Rice XA21‐mediated resistance to bacterial infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119, e2121568119. 10.1073/pnas.2121568119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field, M. A. , Rosen, B. D. , Dudchenko, O. , Chan, E. K. F. , Minoche, A. E. , Edwards, R. J. , Barton, K. , Lyons, R. J. , Tuipulotu, D. E. , Hayes, V. M. , D Omer, A. , Colaric, Z. , Keilwagen, J. , Skvortsova, K. , Bogdanovic, O. , Smith, M. A. , Aiden, E. L. , Smith, T. P. L. , Zammit, R. A. , & Ballard, J. W. O. (2020). Canfam‐GSD: De novo chromosome‐length genome assembly of the German Shepherd Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) using a combination of long reads, optical mapping, and Hi‐C. GigaScience, 9, giaa027. 10.1093/gigascience/giaa027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn, R. D. , Clements, J. , Arndt, W. , Miller, B. L. , Wheeler, T. J. , Schreiber, F. , Bateman, A. , & Eddy, S. R. (2015). HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Research, 43, W30–W38. 10.1093/nar/gkv397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluhr, R. , King, S. I. , Vi, H. , & Shakespeare, W. (2001). Sentinels of disease. Plant Resistance Genes, 127, 1367–1374. 10.1104/pp.010763.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GenBank . (2023). Table2asn . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/table2asn

- Guest, D. , & Keane, P. (2007). Vascular‐streak dieback: A new encounter disease of cacao in Papua New Guinea and Southeast Asia caused by the obligate basidiomycete Oncobasidium theobromae . Phytopathology, 97, 1654–1657. 10.1094/PHYTO-97-12-1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich, A. , Saveliev, V. , Vyahhi, N. , & Tesler, G. (2013). QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 29, 1072–1075. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T. A. (1991). BioEdit: A user‐friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hilario, E. (2018). Plant nuclear genomic DNA preps . Protocols.io. 10.17504/protocols.io.rncd5aw [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. S. , Eddy, S. R. , & Portugaly, E. (2010). Hidden Markov model speed heuristic and iterative HMM search procedure. BMC Bioinformatics, 11, Article 431. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. , Torkel, C. , Stanley, D. , Nasim, J. , Borevitz, J. , & Schwessinger, B. (2021). High‐molecular weight DNA extraction, cleanup and size selection for long‐read sequencing. PLoS One, 16, e0253830. 10.1371/journal.pone.0253830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. , Binns, D. , Chang, H.‐Y. , Fraser, M. , Li, W. , Mcanulla, C. , Mcwilliam, H. , Maslen, J. , Mitchell, A. , Nuka, G. , Pesseat, S. , Quinn, A. F. , Sangrador‐Vegas, A. , Scheremetjew, M. , Yong, S.‐Y. , Lopez, R. , & Hunter, S. (2014). InterProScan 5: Genome‐scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics, 30, 1236–1240. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose, J. , Ghantasala, S. , & Roy Choudhury, S. (2020). Arabidopsis transmembrane receptor‐like kinases (RLKS): A bridge between extracellular signal and intracellular regulatory machinery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21, 4000. 10.3390/ijms21114000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junaid, M. , Purwantara, A. , & Guest, D. (2020). First report of vascular streak dieback symptom of cocoa caused by Ceratobasidium theobromae in Barru District, South Sulawesi. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 486, 012170. 10.1088/1755-1315/486/1/012170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlicki, M. , Antonowicz, S. , & Karnkowska, A. (2022). Tiara: Deep learning‐based classification system for eukaryotic sequences. Bioinformatics, 38, 344–350. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane, P. J. , Flentje, N. J. , & Lamb, K. P. (1972). Investigation of vascular‐streak dieback of cocoa in Papua New Guinea. Australian Journal of Biological Sciences, 25, 553–564. 10.1071/BI9720553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. , Paggi, J. M. , Park, C. , Bennett, C. , & Salzberg, S. L. (2019). Graph‐based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT‐genotype. Nature Biotechnology, 37, 907–915. 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, A. , Rinaldi, C. , Duplessis, S. , Baucher, M. , Geelen, D. , Duchaussoy, F. , Meyers, B. C. , Boerjan, W. , & Martin, F. (2008). Genome‐wide identification of NBS resistance genes in Populus trichocarpa . Plant Molecular Biology, 66, 619–636. 10.1007/s11103-008-9293-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm, B. A. , Goulden, M. G. , Gilbert, J. E. , Kavanagh, T. A. , & Baulcombe, D. C. (1993). A potato virus X resistance gene mediates an induced, nonspecific resistance in protoplasts. The Plant Cell, 5, 913–920. 10.1105/tpc.5.8.913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, M. , Yuan, J. , Lin, Y. , & Pevzner, P. A. (2019). Assembly of long, error‐prone reads using repeat graphs. Nature Biotechnology, 37, 540–546. 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, D. N. , Narasimhan, G. , Nakamura, K. , Brown, J. S. , Schnell, R. J. , & Meerow, A. W. (2006). Identification of cacao TIR‐NBS‐LRR resistance gene homologues and their use as genetic markers. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 131, 806–813. 10.21273/jashs.131.6.806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanaud, C. , Fouet, O. , Clément, D. , Boccara, M. , Risterucci, A. M. , Surujdeo‐Maharaj, S. , Legavre, T. , & Argout, X. (2009). A meta‐QTL analysis of disease resistance traits of Theobroma cacao L. Molecular Breeding, 24, 361–374. 10.1007/s11032-009-9297-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leiva, A. M. , Pardo, J. M. , Arinaitwe, W. , Newby, J. , Vongphachanh, P. , Chittarath, K. , Oeurn, S. , Thi Hang, L. , Gil‐Ordóñez, A. , Rodriguez, R. , & Cuellar, W. J. (2023). Ceratobasidium sp. is associated with cassava witches’ broom disease, a re‐emerging threat to cassava cultivation in Southeast Asia. Scientific Reports, 13, Article 22500. 10.1038/s41598-023-49735-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. (2018). Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics, 34, 3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. (2020). Yak . GitHub. https://github.com/lh3/yak [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Handsaker, B. , Wysoker, A. , Fennell, T. , Ruan, J. , Homer, N. , Marth, G. , Abecasis, G. , & Durbin, R. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics, 25, 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni, M. , Berkeley, M. R. , Seppey, M. , Simão, F. A. , & Zdobnov, E. M. (2021). BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 38, 4647–4654. 10.1093/molbev/msab199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y. , & Zhang, G. (2022). A complete, telomere‐to‐telomere human genome sequence presents new opportunities for evolutionary genomics. Nature Methods, 19, 635–638. 10.1038/s41592-022-01512-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal, C. , Michalopoulou, V. A. , Zou, Z. , Cevik, V. , & Sarris, P. F. (2022). Show me your ID: NLR immune receptors with integrated domains in plants. Essays in Biochemistry, 66, 527–539. 10.1042/EBC20210084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli, J.‐P. , Guest, D. I. , Bailey, B. A. , Evans, H. C. , Brown, J. K. , Junaid, M. , Barreto, R. W. , Lisboa, D. O. , & Puig, A. S. (2019). Chocolate under threat from old and new cacao diseases. Phytopathology, 109, 1331–1343. 10.1094/PHYTO-12-18-0477-RVW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. , Heavens, D. , Lan, Y. , Horsfield, S. , Clark, M. D. , & Leggett, R. M. (2022). Nanopore adaptive sampling: A tool for enrichment of low abundance species in metagenomic samples. Genome Biology, 23, Article 11. 10.1186/s13059-021-02582-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, J. , Chuguransky, S. , Williams, L. , Qureshi, M. , Salazar, G. A. , Sonnhammer, E. L. L. , Tosatto, S. C. E. , Paladin, L. , Raj, S. , Richardson, L. J. , Finn, R. D. , & Bateman, A. (2021). Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Research, 49, D412–D419. 10.1093/nar/gkaa913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamayor, J. C. , Lachenaud, P. , Da Silva e Mota, J. W. , Loor, R. , Kuhn, D. N. , Brown, J. S. , & Schnell, R. J. (2008). Geographic and genetic population differentiation of the Amazonian chocolate tree (Theobroma cacao L). PLoS One, 3, e3311. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamayor, J. C. , Mockaitis, K. , Schmutz, J. , Haiminen, N. , Iii, D. L. , Cornejo, O. , Findley, S. D. , Zheng, P. , Utro, F. , Royaert, S. , Saski, C. , Jenkins, J. , Podicheti, R. , Zhao, M. , Scheffler, B. E. , Stack, J. C. , Feltus, F. A. , Mustiga, G. M. , Amores, F. , … Kuhn, D. N. (2013). The genome sequence of the most widely cultivated cacao type and its use to identify candidate genes regulating pod color. Genome Biology, 14, Article r53. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-r53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nousias, O. , Zheng, J. , Li, T. , Meinhardt, L. W. , Bailey, B. , Gutierrez, O. , Baruah, I. K. , Cohen, S. P. , Zhang, D. , & Yin, Y. (2024). Three de novo assembled wild cacao genomes from the Upper Amazon. Scientific Data, 11, Article 369. 10.1038/s41597-024-03215-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurk, S. , Koren, S. , Rhie, A. , Rautiainen, M. , Bzikadze, A. V. , Mikheenko, A. , Vollger, M. R. , Altemose, N. , Uralsky, L. , Gershman, A. , Aganezov, S. , Hoyt, S. J. , Diekhans, M. , Logsdon, G. A. , Alonge, M. , Antonarakis, S. E. , Borchers, M. , Bouffard, G. G. , Brooks, S. Y. , … Phillippy, A. M. (2022). The complete sequence of a human genome. Science, 376, 44–53. 10.1126/science.abj6987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orduña, H. E. N. , Müller, M. , Krutovsky, K. V. , & Gailing, O. (2024). Genotyping of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) germplasm resources with SNP markers linked to agronomic traits reveals signs of selection. Tree Genetics & Genomes, 20, Article 13. 10.1007/s11295-024-01646-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J. M. , & Stajich, J. E. (2023). Funannotate . GitHub. https://github.com/nextgenusfs/funannotate [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J. E. , Whitlock, B. A. , Meerow, A. W. , & Madriñán, S. (2015). The age of chocolate: A diversification history of Theobroma and Malvaceae. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3, Article 120. 10.3389/fevo.2015.00120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, G. J. , Ismaiel, A. , Rosmana, A. , Junaid, M. , Guest, D. , Mcmahon, P. , Keane, P. , Purwantara, A. , Lambert, S. , Rodriguez‐Carres, M. , & Cubeta, M. A. (2012). Vascular streak dieback of cacao in Southeast Asia and Melanesia: In planta detection of the pathogen and a new taxonomy. Fungal Biology, 116, 11–23. 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M. L. , Resende, M. L. V. , Alves, G. S. C. , Huguet‐Tapia, J. C. , Resende, M. F. R. J. , & Brawner, J. T. (2022). Genome‐wide identification, characterization, and comparative analysis of NLR resistance genes in Coffea spp. Frontiers in Plant Science, 13, Article 868581. 10.3389/fpls.2022.868581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers, E. W. , Cavanaugh, M. , Clark, K. , Pruitt, K. D. , Sherry, S. T. , Yankie, L. , & Karsch‐Mizrachi, I. (2023). GenBank 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Research, 51, D141–D144. 10.1093/nar/gkac1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, R. J. , Kuhn, D. N. , Brown, J. S. , Olano, C. T. , Phillips‐Mora, W. , Amores, F. M. , & Motamayor, J. C. (2007). Development of a marker assisted selection program for cacao. Phytopathology, 97, 1664–1669. 10.1094/PHYTO-97-12-1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim, S. B. , Corpuz, R. L. , Simmonds, T. J. , & Geib, S. M. (2022). HiFiAdapterFilt, a memory efficient read processing pipeline, prevents occurrence of adapter sequence in PacBio HiFi reads and their negative impacts on genome assembly. BMC Genomics, 23, Article 157. 10.1186/s12864-022-08375-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão, F. A. , Waterhouse, R. M. , Ioannidis, P. , Kriventseva, E. V. , & Zdobnov, E. M. (2015). BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single‐copy orthologs. Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–3212. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G. (2021). Identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with resistance to vascular streak dieback disease of cacao. The University of Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Sniezko, R. A. (2006). Resistance breeding against nonnative pathogens in forest trees—Current successes in North America. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 279, 270–279. 10.1080/07060660609507384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford, A. M. , Harden, R. , & Parks, C. R. (2000). Phylogeny and biogeography of Juglans (Juglandaceae) based on matK and ITS sequence data. American Journal of Botany, 87, 872–882. 10.2307/2656895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuernagel, B. , Witek, K. , Krattinger, S. G. , Ramirez‐Gonzalez, R. H. , Schoonbeek, H.‐J. , Yu, G. , Baggs, E. , Witek, A. I. , Yadav, I. , Krasileva, K. V. , Jones, J. D. G. , Uauy, C. , Keller, B. , Ridout, C. J. , & Wulff, B. B. H. (2020). The NLR‐annotator tool enables annotation of the intracellular immune receptor repertoire. Plant Physiology, 183, 468–482. 10.1104/pp.19.01273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. , Lu, F. , Luo, Y. , Bie, L. , Xu, L. , & Wang, Y. (2023). OrthoVenn3: An integrated platform for exploring and visualizing orthologous data across genomes. Nucleic Acids Research, 51, W397–W403. 10.1093/nar/gkad313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G. Y. , & Tan, W. K. (1988). Genetic variation in resistance to vascular‐streak dieback in cocoa (Theobroma cacao). Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 75, 761–766. 10.1007/BF00265602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D. , Higgins, D. G. , & Gibson, T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position‐specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research, 22, 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias, P. A. , Edwards, R. J. , Surana, P. , Mangelson, H. , Inácio, V. , do Céu Silva, M. , Várzea, V. , Park, R. F. , & Batista, D. (2022). A chromosome‐level genome resource for studying virulence mechanisms and evolution of the coffee rust pathogen Hemileia vastatrix . bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.07.29.502101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias, P. A. , & Guest, D. I. (2014). Tree immunity: Growing old without antibodies. Trends in Plant Science, 19, 367–370. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trisno, J. , Reflin, R. , & Martinius, M. (2016). Vascular streak dieback: Penyakit Baru Tanaman Kakao di Sumatera Barat. Jurnal Fitopatologi Indonesia, 12, 142. 10.14692/jfi.12.4.142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, C. J. , Daymond, A. J. , Gutierrez, O. , Hadley, P. , Livingstone, D. , Motamayor, J. C. , Phillips, W. , Umaharan, P. , & Zhang, D. (2017, November 13–17). Adopting reference genotypes to identify off‐types in cacao collections [Paper presentation]. 2017 International Symposium on Cocoa Research, Lima, Peru.

- Van de Weyer, A.‐L. , Monteiro, F. , Furzer, O. J. , Nishimura, M. T. , Cevik, V. , Witek, K. , Jones, J. D. G. , Dangl, J. L. , Weigel, D. , & Bemm, F. (2019). A species‐wide inventory of NLR genes and alleles in Arabidopsis thaliana . Cell, 178, 1260–1272. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weilguny, L. , De Maio, N. , Munro, R. , Manser, C. , Birney, E. , Loose, M. , & Goldman, N. (2023). Dynamic, adaptive sampling during nanopore sequencing using Bayesian experimental design. Nature Biotechnology, 41, 1018–1025. 10.1038/s41587-022-01580-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyer, A.‐L. , Monteiro, F. , Furzer, O. J. , Nishimura, M. T. , Cevik, V. , Witek, K. , Jones, J. D. G. , Dangl, J. L. , Weigel, D. , & Bemm, F. (2019). The Arabidopsis thaliana pan‐NLRome. bioRxiv. 10.1101/537001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, B. T. , Lee, S. , & Taylor, J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., & White T. J. (Eds.), PCR protocols: A guide to methods and application (pp. 315–322) Academic Press,. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y. , Cesari, S. , & Kroj, T. (2022). Insight into the structure and molecular mode of action of plant paired NLR immune receptors. Essays in Biochemistry, 66, 513–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement