Abstract

Abstract

Introduction

Burdensome care transitions may occur despite clinicians’ engagement in care planning discussions with residents and their family/friend care partners. Conversations about potential hospital transfers can better prepare long-term care (LTC) residents, their families and care providers for future decision-making. Lack of such discussions increases the likelihood of transitions that do not align with residents’ values. This study will examine experiences of LTC residents, family/friend care partners and staff surrounding decision-making about LTC to hospital transitions and codesign a tool to assist with transitional decision-making to help prioritise needs and preferences of residents and their care partners.

Methods and analysis

This study will use semi-structured needs assessment interviews (duration: 1 hour), content analysis of existing decision support and discussion tools and a codesign workshop series (for residents and care partners, and for staff) at three participating LTC home research sites. This qualitative work will inform the development of a decision support tool that will subsequently be pilot tested and evaluated at three partnering LTC homes in future phases of the project. The study is guided by the Person-centred Practice in Long-term Care theoretical framework. Interview audio recordings will be transcribed verbatim and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Participants will be recruited in partnership with three LTC homes in Ottawa, Ontario. Eligible participants will be English or French speaking residents, family/friend care partners or staff (eg, physicians, nurses and personal support workers) who have experienced or been involved in a transition from LTC to hospital.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Bruyère Health Research Ethics Board (#M16-23-030). Findings will be (1) reported to participating and funding organisations; (2) presented at national and international conferences and (3) disseminated by peer-review publications.

Keywords: Hospitalization, Decision Making, Patient-Centered Care, Nursing Care, Nursing Homes

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Needs assessment interviews will be conducted with individuals in diverse roles in the transition process from three long-term care homes with varying organisational structures in Ottawa, Canada.

All aspects of the study will be coproduced with clinical experts, family/friend care partners and long-term care residents.

The study is limited by its geographic scope, as all participating homes are in a single region of Canada and lack representation from rural areas.

Special efforts will be made to recruit a diverse sample in both official languages, despite the relatively homogeneous populations at the research sites.

Introduction

Long-term care (LTC) residents are typically nearing the final stages of their life’s journey; these stages often include many care transitions.1 2 Care transitions (called transitions henceforth) refer to transfers between different care settings (eg, hospital, LTC, home and community care).3 Transitions across care settings can be difficult and stressful, especially for adults nearing the end of life.4 Transitions near the end of life can also result in adverse health outcomes for residents.5 For example, a recent study found that among 555 residents who transitioned from LTC to hospital, adverse events (ie, skin tears, pressure ulcers and falls) were experienced in 37% of transitions; and 70% of these adverse events were deemed to be preventable.5 Furthermore, the proportion of LTC residents who die in hospital at the end of life varies markedly between countries, from 6% in Canada to 77% in Japan.6

Person-centred care is considered as the gold standard in LTC care in Canada7 and aligns with the Residents’ Bill of Rights (2021), which mandates that residents have the right to be involved in the decision-making around their care in LTC homes in Ontario.8 In this province, LTC is primarily available to individuals with complex medical needs or those requiring substantial assistance with activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing and mobility. Health and social care for residents in LTC is publicly funded but requires resident copayments to cover accommodation costs.9 LTC homes are regulated under the under the Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021,10 which replaced the Long-Term Care Homes Act, 2007.11

In contrast to LTC, other care options for older adults in Ontario include retirement homes and ageing in place through community-based care.12 Retirement homes, which provide more independence and typically cater to older adults with fewer healthcare needs, are privately funded and not regulated as strictly as LTC.13 Ageing in place, supported by government-subsidised home care services, is a growing trend for older adults who require less intensive support and prefer to remain in their homes.14 While the Canada Health Act provides some universal healthcare coverage across provinces,15 the specifics of publicly funded services vary significantly.

While person-centred care is the ideal, the reality of care delivery in LTC homes is often constrained by systemic challenges. These include understaffing, time constraints and heavy workloads, all of which contribute to a system that prioritises efficiency and medical needs over individualised care.9 As a result, care in LTC is frequently task-oriented, focusing on managing medical conditions rather than attending to individual preferences or emotional and social needs.16 In contrast, person-centred care shifts the focus from a system-driven, medicalised approach to one that prioritises the resident’s values, personal goals and holistic well-being.17 This model encourages collaboration between residents, their family or friend care partners and staff, emphasising individualised care plans that align with the resident’s identity, preferences and experiences.17 Person-centred care differs significantly from standard care in Ontario LTC homes, which is often shaped by systemic barriers that limit the ability of staff to fully engage with residents on a personal level.18

Person-centred care refers to care that encompasses the principles of respecting individuals, acknowledging their inherent human dignity, treating them as unique persons and understanding what holds significance to them in relation to their treatment and care.17 Moving forward, the term ‘person-centred care’ will be referred to as ‘resident-centred care’ to better align with this study’s focus on individuals residing in LTC. This term also acknowledges that family or friend care partners (ie, informal care assistants who take on the primary role of assisting an individual in managing their health)19 frequently play a role in care decision-making alongside the LTC residents that they support.20

We will use the Person-centred Practice in Long-term Care (PeoPLe) theoretical framework21 to guide and inform this work. The PeoPLe framework offers a resident-centred care perspective that all practices in LTC, including facilitating transitions to and from hospital, should prioritise residents’ values and preferences and respect residents’ personhood as they live with progressive disease and disability. The framework is based on five constructs: (1) prerequisites; (2) practice environment; (3) person-centred processes; (4) fundamental principles of care and (5) outcome.21 The prerequisite construct requires professional competency, interpersonal skills and commitment to the job. The practice environment invites shared decision-making, effective staff relationships and supportive organisational systems.21 The person-centred processes and fundamental principles of care require holistic approaches, authentic engagement and working with the person’s beliefs.21 Finally, the outcome promotes a healthful culture.21 We will use these constructs to help us highlight and navigate the tensions inherent in providing resident-centred care17 in LTC settings, where over 70% of residents have dementia and may have difficulty engaging in discussions and decision-making about their care.22 The framework’s explicit focus on LTC is highly relevant to our aim to develop a decision-making tool that will be useful in this setting given common structural barriers to the provision of resident-centred care in LTC, such as time constraints, heavy workloads, staffing shortages and lack of management support.23

Transition decisions require consideration of the benefits and harms of the transition and discussions with residents and care partners about which of these matter to them most.24 When an LTC resident experiences symptoms such as severe pain, respiratory distress or infection, a transfer to the hospital can provide access to diagnostic tests and treatments.25 However, a transfer to hospital may be misaligned with the resident’s or their family/friend care partners’ wishes, understanding of their illness trajectory and goals of care.26 LTC to hospital transitions can cause a variety of emotional and physical harms.3 For example, waiting in an emergency room, away from the resident’s home environment and familiar care team can lead to feelings of distress, anxiety, fear and lack of autonomy.27 It can also lead to complications such as delirium, pressure ulcers and hospital acquired infections.28 When decisions about transitions from LTC to hospital are resident-centred, they can improve residents’ satisfaction with care, the quality and safety of care, quality of life and well-being of residents and decrease hospital readmission rates.29,31 On the other hand, many LTC residents are transferred to hospital at the end of life and die receiving burdensome medical treatments.32 33 This process denies them the opportunity for a tranquil death in a familiar, home-like environment that aligns with the preferences of the majority of Canadians.32 33

The existing body of literature consistently underscores the insufficient support provided to LTC staff during decision-making processes associated with transitions from LTC to hospital settings.34,36 Similarly, when weighing potential risks and benefits of a transition from LTC to hospital, residents and their family/friends care partners may not fully comprehend or take into account the expected or anticipated decline in both physical and cognitive abilities that many LTC residents experience.37 This decline is often associated with the frailty death trajectory, which refers to a unique pattern of decline in the last 12 months of life.37 This trajectory for LTC residents is different from the terminal phase observed in individuals dying of cancer, for example, where there is a more clearly defined period leading up to the end of life.38 Notably, decisions regarding transitions from LTC to hospital (eg, transfer to hospital to insert an intravenous line to treat dehydration or feeding tube because of dysphagia—both of which are often expected in advanced frailty)37 as an attempt to delay or reverse a progressive decline often do not consider the natural progression of disease nor the resident’s values and goals.4 This may result in actions that harm residents and are stressful for family/friend care partners.38 An additional advantage of developing a decision support tool to be used by residents, care partners and staff when preparing for the possibility of a future transition from LTC to hospital is the parallel benefit of enhanced understanding by family and friends of the anticipated changes in the residents’ health over the course of their stay in LTC.

This project will employ a participatory codesign approach, engaging residents, care partners and staff as equal collaborators. In phase 1, needs assessments, content analysis and codesign workshops will capture diverse perspectives to guide the creation of a decision-making tool for transitions between LTC homes and hospitals. Subsequent phases will involve interdisciplinary tool development, followed by pilot testing and evaluation in partnership with LTC homes. By incorporating the voices of a diverse population, including Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) communities, the study will ensure culturally responsive solutions, enhancing the inclusivity and applicability of the tool for all collaborators involved.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study is to inform and codesign a decision-making tool that will help ensure that decisions regarding LTC to hospital transitions support residents’ autonomy and align with their preferences and priorities.

Objectives

Conduct a needs assessment with LTC residents, care partners and staff involved in decisions about transitions from LTC to hospital to inform the development of a decision-making tool.

Undertake a content analysis of existing decision support and discussion tools to inform the codesign of our tool with a focus on cultural awareness and safety.

Codesign a decision-making tool with LTC residents, care partners and staff at three LTC sites aimed at improving the decision-making experience regarding LTC to hospital transitions that is acceptable and appropriate to residents, family/friend care partners and care providers and is feasible and sustainable for long-term use in LTC settings.

Research questions

What are the experiences of residents, care partners and staff surrounding decision-making about transitions from LTC to hospital?

What can we learn from existing decision support and discussion tools, specifically around cultural awareness and safety?

What are staff, resident and care partner priorities for a decision-making tool that they feel would better inform, support and engage them before and during the decision-making process regarding transitions from LTC to hospital?

Methods and analysis

This study will be conducted in collaboration with three LTC homes in Ontario, Canada. The research team maintains continuous partnerships with these homes and is well positioned to codesign a tool with residents, care partners and staff (eg, physicians, nurses, personal support workers and administrators) to aid in decision-making about LTC to hospital transitions. Phase 1 of this project will use a three-part sequential qualitative study design that includes needs assessment interviews, content analysis of existing tools and collaborative codesign workshops.

Patient and public involvement

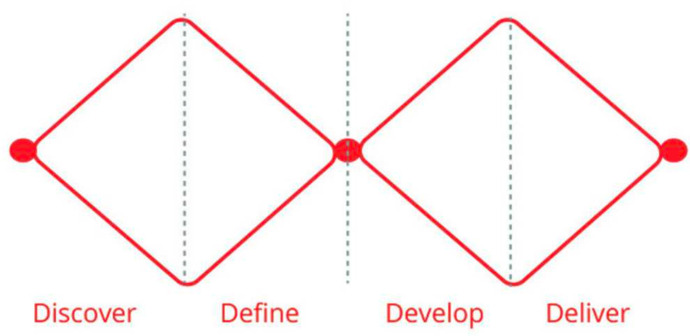

To develop the overarching study aims and design, the research team engaged with the leadership team that guides the larger study in which this project is embedded, the family and friends’ and resident councils of our partnering LTC homes and a Research Advisory Committee comprised of family/friend care partners. These discussions informed the larger 4 year study that will inform and codesign (phase 1), create (phase 2), pilot test (phase 3) and evaluate (phase 4) a decision-making tool to guide LTC to hospital transitions to be more resident-centred. We will adapt the Double Diamond39 method’s four stages: (1) discover, (2) define, (3) develop and (4) deliver to guide the development of our decision-support tool (figure 1).

Figure 1. Double-Diamond method by the London Design Council (2015). This figure illustrates the Double-Diamond method’s four stages: (1) discover, (2) define, (3) develop and (4) deliver to guide the development of our decision-support tool.

This participatory codesign approach treats all stakeholders as equal collaborators in the design process.39 This will allow for the development of a tool and indicators of success that meet the needs of residents, care partners and staff.40 The discover and define stages will take place during phase 1 (the period covered by this protocol) via needs assessment interviews (objective 1), content analysis of existing tools and discussion guides (objective 2) and codesign workshops (objective 3). The develop and deliver stages will comprise the tool creation by the quantitative team (comprised of patient partners, researchers, clinicians, engineers and graphic designers) within our research team (phase 2 ethics approval #M16-23-030) based on the findings from objectives 1–3, and then pilot tested (phase 3) and evaluate (phase 4) in partnership with LTC homes later in the larger project.

Phase 1: objective 1

We will conduct semistructured needs assessment interviews in our three partnering LTC homes with residents (n=9); family/friend care partners, power of attorney for personal care or substitute decision-makers (n=9) and staff (n=9) with experience of decision-making regarding an LTC to hospital transition. The selection of these LTC homes is based on their existing partnerships with our research team and their diverse resident populations, which will help us capture a range of experiences and perspectives. To recruit participants, we will post recruitment posters in LTC homes, include information in newsletters, present the project at family, resident and nurse council network meetings, and work with LTC home leadership to identify interested individuals. The target of nine participants per group was determined based on previous research showing that this sample size is typically sufficient to achieve data saturation in qualitative studies involving LTC settings.41 We expect to reach data saturation as common themes and perspectives emerge,42 but we are prepared to increase the sample size if additional data are needed to ensure comprehensive coverage of the research topic.

We will use a qualitative descriptive design for this substudy 1, a methodology well suited for understanding complex, real-world phenomena, such as decision-making during care transitions in LTC settings.43 44 Qualitative descriptive studies aim to provide a straightforward account of participants’ experiences and are commonly used in health research to capture the perspectives of various stakeholders.43 This approach aligns with our objective to explore the needs and experiences of residents, care partners and staff, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of decision-making in LTC to hospital transitions. Based on past research, we anticipate that this sample size (n=27) will be sufficient to get diverse viewpoints to address our research questions.31 The interview script (duration 1 hour) will be guided by the Decisional Needs Assessment Workbook by Jacobsen et al.45 See online supplemental file 1 for the interview guide for resident participants. Sampling will be purposive and will aim to ensure maximum inclusivity and diversity of research participants through collaboration with the partnering homes’ equality, diversity and inclusion committees. As the older adult population grows in Canada, we are also witnessing wider diversity in all age categories.46 This is reflected in the diversity of LTC staff, with representation from BIPOC communities.47 Ensuring a diverse sample in our recruitment process will foster inclusivity in efforts to improve care transitions for all LTC residents, care partners and staff. Interviews will be conducted either in person or virtually by members of the research team, with informed consent obtained prior to the interviews. In cases where a participant is unable to give consent directly, a designated proxy may do so on their behalf.48 For residents who have a proxy, ongoing assent will be observed throughout the sessions by evaluating their verbal, behavioural or emotional responses, such as smiling or nodding, to ensure their comfort and willingness to continue participating.48 Interviews will include a sociodemographic questionnaire component to help us describe our sample and consider the relevance of intersecting equity considerations in our interpretation of the interview data. To strengthen the evaluation of the decision-making tool and enhance the overall robustness of the study, we will incorporate specific outcomes in phase 1 that will facilitate both quantitative and qualitative assessments in subsequent phases. Specifically, we will assess perceived adequacy of support through a structured questionnaire designed to capture gaps and satisfaction in current transition processes. Each interviewer will write a self-reflexive journal entry after each interview. Recordings of the interviews will be transcribed for analysis.

Qualitative analysis software (MAXQDA)48 will be used to organise interview transcript data and data will be analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) according to Braun and Clarke’s approach.49 This robust method of analysis seeks to establish patterns of meaning by recursively engaging with the data. RTA involves a six-step process including familiarisation with the data set; coding closely to the research question; generating initial themes; developing and reviewing themes; refining themes and reporting on the themes.49 The robustness and rigour of the data will be assessed using Lincoln and Guba’s four-dimension criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability.50 Credibility will be ensured through the prolonged engagement of participants,50 involving an introductory session with LTC home councils, continuous involvement in both study phases and presentation of results at the study’s completion. Dependability will be established through a comprehensive record of the data collection process and an adaptable protocol that embraces reflexivity. Confirmability will be ensured through reflexivity by having weekly team meetings and maintaining reflexive journals after interviews. Finally, transferability will be confirmed through our purposive sampling at each of the three LTC homes and the comparison of findings across research sites.

Phase 1: objective 2

A content analysis of existing serious illness conversation tools and decision-making aids will be conducted guided by the PeoPLe theoretical framework.21 Qualitative content analysis is a method used to systematically interpret textual data by identifying patterns, themes and relationships within the material.51 This approach emphasises coding and categorising data to make sense of its underlying meanings, ensuring that all relevant aspects of the data are examined.51 In this substudy 2, we will apply directed content analysis, where pre-existing theories, such as the PeoPLe framework,21 guide the analysis. This method ensures a structured examination of tools, focusing on their cultural sensitivity, accessibility and effectiveness in addressing resident preferences. The review will involve a systematic search of the literature to identify tools currently in use with particular emphasis on those that prioritise cultural relevance and safety in LTC. Criteria for inclusion will encompass tools intended for facilitating discussions about serious illness or care transitions among healthcare providers, residents and care partners, with a specific focus on those designed to be culturally aware. We will develop a set of evaluative criteria based on the content analysis of existing tools and the initial feedback gathered during codesign workshops. These criteria may include aspects such as tool usability, clarity, cultural sensitivity and impact on decision-making processes. We will work with residents, care partners and staff to identify the evaluation criteria that are most meaningful to them and prioritise the measurement of these in our evaluation. This set of criteria will guide the assessment of the new decision-making tool’s effectiveness in phase 4. This approach seeks to supplement and enhance the representation of ethno-cultural diversity in our study, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of the perspectives and preferences of residents, care partners and staff.

Phase 1: objective 3

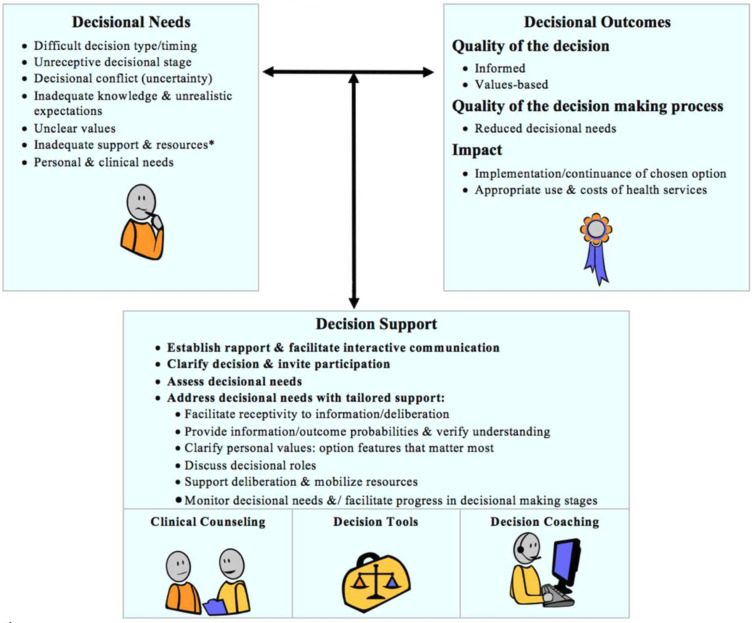

Codesign methodology emphasises collaborative, participatory processes where all stakeholders actively contribute to the development of a solution.40 This substudy 3 will follow a participatory action research framework, fostering a cyclical process of action, reflection and refinement.52 Informed by findings from objectives 1 and 2, we will facilitate two codesign workshops at each of three LTC homes (n=6) to solicit resident, family/friend care partner and staff preferences and priorities for the design of the decision-making tool. We anticipate that this number of workshops will allow us to reach data saturation as recurring themes and patterns emerge across the participant groups.42 However, additional workshops will be conducted if necessary to ensure comprehensive data collection. The first three workshops (duration: 2 hours each) will include residents and care partners from the three partnering LTC homes recruited through purposive sampling. This method involves deliberately selecting participants based on specific characteristics, such as their experience with transitions from LTC to hospital or their involvement in decision-making processes.53 A minimum of three participants from each partnering LTC home will be recruited for each codesign workshop. Based on past research, we anticipate that this sample size will be sufficient to gather diverse insight for tool development.31 Participants will be recruited using snowball sampling with the help of participants from objective 1. Objective 3 will be open to participants from phase 1 as well as new participants. We will obtain informed consent prior to participation in codesign workshops. The research team will share findings from objectives 1 and 2 and then facilitate a discussion of resident and care partner preferences and priorities for a tool-based solution to improving resident-centred decision-making around LTC to hospital transitions. Participants will be invited to brainstorm tool design, items included and format guided by the Ottawa Decision Support Framework54 (figure 2). This framework aims to improve decisional outcomes by supporting quality decision-making that is informed and values-based and has been instrumental in developing many patient decision aids, measures and training programmes.54 We will use the Ottawa Decision Support Framework to develop a series of prompts to guide the codesign workshops. This will ensure that we solicit feedback on all the decisional needs identified in the framework.

Figure 2. The Ottawa Decision Support Framework by Stacey, Legare, Boland, Lewis, Loiselle, Hoefel, Garvelink and O’Connor (2020). This framework aims to improve decisional outcomes by supporting quality decision-making.

The first round of codesign workshops will be recorded, transcribed, and a member of the research team will take detailed notes on participant preferences, and feedback for a decision-making tool prototype. The research staff will analyse the data from the codesign workshops to identify cross-cutting themes and preferences for a decision-making tool and consolidate a list of key priorities and design criteria based on resident and care partner values, preferences and recommendations. This list will be distributed back to workshop participants for participant validation as a method of increasing trustworthiness.55 The list will be revised as needed.

The second round of codesign workshops will be held with key staff members involved in making decisions about LTC to hospital transitions (eg, personal support workers, nurses and physicians). Staff will be recruited through connections made in objective 1, using informational flyers that provide a description of the study and contact information for our team and snowball sampling. We will recruit three staff members at each home in different care provider roles (n=9). We will facilitate one codesign workshop at each of the three LTC homes where the researchers will share findings from objectives 1 and 2 and the first round of codesign workshops and then facilitate a discussion of staff preferences and priorities for the design, items included and format of a tool-based solution to improving resident-centred decision-making around LTC to hospital transitions. We will use the same process for informed consent, data collection and analysis as in the first round of codesign workshops.

In addition, we will pilot test preliminary tool features within a subset of participating LTC homes to gather initial data on their feasibility and acceptability (phase 3). This pilot testing will involve collecting feedback on the tool’s design, functionality and user experience from both residents and staff. These preliminary findings will inform refinements and adjustments to ensure that the final tool is well aligned with the needs and preferences identified in phase 1.

Timeline

Phase 1 is anticipated to span approximately 6 months, from January 2024 to June 2024. Phase 2 will follow from July 2024 to December 2024. Phase 3 is scheduled from January 2025 to March 2025, with phase 4 occurring from April 2025 to June 2025.

Dissemination

Results from phase 1 will be used to inform the creation of the tool in phase 2 of the larger study. Phase 1 results will also be shared with residents, family/friend care partners and staff at an in-person session at each participating home. The research team will develop infographics describing phase 1 results in English and French and encourage the family, resident and nurse councils at each home to disseminate them at their council meetings. Knowledge translation activities for phase 1 findings also include presentations at conferences (eg, the Canadian Hospice and Palliative Care Association Annual conference, Ontario Long-Term Care Clinicians Annual Conference and Palliative Approach in LTC Community Practice webinars), progress reports to our partners, publications in open-access journals (eg, BMC Geriatrics) and social media posts by the researchers. Later in the larger study, the new decision-making tool will be disseminated through the Long-Term Care Community Practice, a group of professionals, patients and family/friend care partners who share best practices for palliative approaches in LTC. The tool will also be circulated via Advance Care Planning Canada, an initiative dedicated to creating a Pan-Canadian Framework for advance care planning.

Ethics

This project was approved by the Bruyère Health Research Ethics Board (#M16-23-036) as well as the ethics boards of each three partnering LTC homes. Informed consent will be collected from all participants prior to the start of the interviews and workshops. If a participant requires a proxy to consent on their behalf, ongoing assent will be obtained based on an assessment of how the resident expresses or indicates their preferences verbally, behaviourally or emotionally (eg, smiling, nodding, etc).56 This assessment will ensure that the participant is able to make a meaningful choice and has at least a minimal level of understanding. Given that 70% of residents in LTC have dementia,22 we anticipate that there will be involvement from this population in our research study.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Family and Friends Council and the Residents Council at St Patrick’s Home for their feedback on the study design. We would also like to thank the Family Councils Ontario’s Research Advisory Committee for their feedback and ongoing support of the project.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant number TIA 184572.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-086748).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Collaborators: The following are members of the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Bruyère Health Research Institute and have all been integral to the overall design of the study: Alixe Ménard, Lauren Konikoff, Yamini Singh, Mary M Scott, Christina Y Yin, Maren Kimura, Sarina R Isenberg, Frank Molnar, Kumanan Wilson, Daniel Kobewka, Celeste Fung, Jackie Kierulf and Krystal Kehoe MacLeod. The contributions of the following collaborators were indispensable to the composition of this paper: Michaela Adams (Perley Health), Sandy Shamon (University of Toronto), and Sharon Kaasalainen (McMaster University).

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Contributor Information

Alixe Ménard, Email: alimenard@ohri.ca.

Lauren Konikoff, Email: lkonikoff@ohri.ca.

Michaela Adams, Email: madams@perleyhealth.ca.

Yamini Singh, Email: yasingh@ohri.ca.

Mary M Scott, Email: marscott@ohri.ca.

Christina Y Yin, Email: cyin@ohri.ca.

Maren Kimura, Email: mkimura4@uwo.ca.

Daniel Kobewka, Email: dkobewka@toh.ca.

Celeste Fung, Email: CelesteFung@stpats.ca.

Sarina R Isenberg, Email: SIsenberg@bruyere.org.

Sharon Kaasalainen, Email: kaasal@mcmaster.ca.

Jackie Kierulf, Email: jckhome@sympatico.ca.

Frank Molnar, Email: fmolnar@toh.ca.

Sandy Shamon, Email: sandy.shamon@utoronto.ca.

Kumanan Wilson, Email: kwilson@toh.ca.

Krystal Kehoe MacLeod, Email: kmacleod@bruyere.org.

Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Bruyère Research Institute:

M Alixe, K Lauren, S Yamini, S Mary, Y Christina, K Maren, K Daniel, K Jackie, KM Krystal, F Celeste, S Sandy, K Sharon, M Frank, W Kumanan, and I Sarina

Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and Bruyère Health Research Institute:

Alixe Ménard, Lauren Konikoff, Michaela Adams, Yamini Singh, Mary M Scott, Christina Y Yin, Maren Kimura, Daniel Kobewka, Jackie Kierulf, Krystal Kehoe MacLeod, Celeste Fung, Sandy Shamon, Sharon Kaasalainen, Frank Molnar, Kumanan Wilson, and Sarina R Isenberg

References

- 1.Gruneir A, Bronskill S, Bell C, et al. Recent health care transitions and emergency department use by chronic long term care residents: a population-based cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:202–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CIHI; [15-Sep-2023]. Profile of residents in residential and hospital-based continuing care 2017-2018.https://www.cihi.ca/en/profile-of-residents-in-residential-and-hospital-based-continuing-care-2017-2018 Available. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naylor M, Keating SA. Transitional Care: Moving patients from one care setting to another. Am J Nurs. 2008;108:58–63. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336420.34946.3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham S, Menec V. Transitions Between Care Settings at the End of Life Among Older Homecare Recipients: A Population-Based Study. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016;2 doi: 10.1177/2333721416684400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapoor A, Field T, Handler S, et al. Adverse Events in Long-term Care Residents Transitioning From Hospital Back to Nursing Home. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1254–61. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allers K, Hoffmann F, Schnakenberg R. Hospitalizations of nursing home residents at the end of life: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2019;33:1282–98. doi: 10.1177/0269216319866648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viau-Guay A, Bellemare M, Feillou I, et al. Person-centered care training in long-term care settings: usefulness and facility of transfer into practice. Can J Aging. 2013;32:57–72. doi: 10.1017/S0714980812000426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fixing long-term care act. 2021. [7-Dec-2023]. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/view Available. Accessed.

- 9.Daly T. Out of place: mediating health and social care in Ontario’s long-term care sector. Can J Aging. 2007;26 Suppl 1:63–75. doi: 10.3138/cja.26.suppl_1.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of Ontario Fixing long-term care act. 2021. [16-Sep-2024]. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/view Available. Accessed.

- 11.Government of Ontario Long-term care homes act. 2007. [16-Sep-2024]. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/view Available. Accessed.

- 12.Peckham A, Rudoler D, Li JM, et al. Community-Based Reform Efforts: The Case of the Aging at Home Strategy. Healthc Policy. 2018;14:30–43. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2018.25550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manis DR, Poss JW, Jones A, et al. Rates of health services use among residents of retirement homes in Ontario: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2022;194:E730–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell L, Poss J, MacDonald M, et al. Inter-provincial variation in older home care clients and their pathways: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Canada. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:389. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04097-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Act C. Canada Health Act. 2004. [2-Oct-2024]. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/canada-health-care-system-medicare/canada-health-act.html Available. Accessed.

- 16.Woods DL, Navarro AE, LaBorde P, et al. Social Isolation and Nursing Leadership in Long-Term Care. Nurs Clin N Am. 2022;57:273–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2022.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godfrey M, Young J, Shannon R, et al. The Person, Interactions and Environment Programme to Improve Care of People with Dementia in Hospital: A Multisite Study. NIHR Journals Library; 2018. [23-Oct-2023]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK508103/ Available. accessed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee C, Tripp D, McVie M, et al. Empowering Ontario’s long-term care residents to shape the place they call home: a codesign protocol. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e077791. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett PN, Wang W, Moore M, et al. Care partner: A concept analysis. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65:184–94. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kortes-Miller K, Boulé J, Wilson K, et al. Dying in Long-Term Care: Perspectives from Sexual and Gender Minority Older Adults about Their Fears and Hopes for End of Life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2018;14:209–24. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2018.1487364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer H, McCormack B, Hildebrandt C, et al. Knowing the person of the resident – a theoretical framework for Person-centred Practice in Long-term Care (PeoPLe) IPDJ . 2020;10:1–16. doi: 10.19043/ipdj.102.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng R, Lane N, Tanuseputro P, et al. Increasing Complexity of New Nursing Home Residents in Ontario, Canada: A Serial Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1293–300. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes JB, Vareta D, Fernandes S, et al. Rehabilitation Workforce Challenges to Implement Person-Centered Care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:3199. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earl T, Katapodis N, Schneiderman S, et al. Making Healthcare Safer III: A Critical Analysis of Existing and Emerging Patient Safety Practices. Agency for 21 Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020. [23-Oct-2023]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555516/ Available. accessed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobewka DM, Kunkel E, Hsu A, et al. Physician Availability in Long-Term Care and Resident Hospital Transfer: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:469–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman EA, Min SJ. Patients’ and Family Caregivers’ Goals for Care During Transitions Out of the Hospital. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2015;34:173–84. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2015.1095149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutlu S, Çetinkaya A, Yılmaz E. Emergency Service Perceptions and Experiences of Patients: “Not A Great Place, But Not Disturbing”. J Patient Exp. 2021;8 doi: 10.1177/23743735211034298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ. 2004;170:1678–86. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsen ER, Hollister B, Söderhamn U, et al. What matters to older adults? Exploring person-centred care during and after transitions between hospital and home. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:569–81. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo JW, Jabeen S, Bajwa T, Jr, et al. Hospital readmission of skilled nursing facility residents: a systematic review. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2015;8:148–56. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20150129-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuipers SJ, Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. The importance of patient-centered care and co-creation of care for satisfaction with care and physical and social well-being of patients with multi-morbidity in the primary care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3818-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canada Economy News. Canadian Government Policy . C.D. Howe Institute; [25-Apr-2023]. Expensive endings: reining in the high cost of end-of-life care in canada.https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/expensive-endings-reining-high-cost-end-life-care-canada Available. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174:627–33. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siu HYH, Elston D, Arora N, et al. A Multicenter Study to Identify Clinician Barriers to Participating in Goals of Care Discussions in Long-Term Care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:647–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:549–56. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ethier JL, Paramsothy T, You JJ, et al. Perceived Barriers to Goals of Care Discussions With Patients With Advanced Cancer and Their Families in the Ambulatory Setting: A Multicenter Survey of Oncologists. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:125–42. doi: 10.1177/0825859718762287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stow D, Matthews FE, Hanratty B. Frailty trajectories to identify end of life: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Med. 2018;16:171. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lunney JR. Patterns of Functional Decline at the End of Life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park BM, Lee HJ. Healthcare Safety Nets during the COVID-19 Pandemic Based on Double Diamond Model: A Concept Analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:1014. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9081014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirk J, Bandholm T, Andersen O, et al. Challenges in co-designing an intervention to increase mobility in older patients: a qualitative study. J Health Organ Manag. 2021;35:140–62.:140. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-02-2020-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma SK, Mudgal SK, Gaur R, et al. Navigating Sample Size Estimation for Qualitative Research. J Med Evidence. 2024;5:133–9. doi: 10.4103/JME.JME_59_24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13:201–16. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, et al. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25:443–55. doi: 10.1177/1744987119880234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunter DJ, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. GSTF J Nurs Health Care. 2019;4 https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/180272/7/180272.pdf Available. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobsen MJ, O’Connor AM, Stacey D. Decisional needs assessment in populations. 2013. [9-Jun-2023]. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/implement/population_needs.pdf Available. Accessed.

- 46.Ontario Centres for Learning, Research, and Innovation in Long-Term Care Embracing diversity toolkit. 2021. [14-Nov-2021]. https://clri-ltc.ca/resource/embracingdiversity/ Available. Accessed.

- 47.National Institute on Ageing Supporting diversity and inclusion in long-term care. 2020. [30-Jan-2024]. https://www.niageing.ca/commentary-posts/2020/9/3/supporting-diversity-and-inclusion-in-long-term-care Available. Accessed.

- 48.Black BS, Rabins PV, Sugarman J, et al. Seeking assent and respecting dissent in dementia research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:77–85. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1de2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–97. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. N D for P E. 1986;1986:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ev.1427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, et al. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23:42–55. doi: 10.1177/1744987117741667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Funnell S, Tanuseputro P, Letendre A, et al. “Nothing About Us, without Us.” How Community-Based Participatory Research Methods Were Adapted in an Indigenous End-of-Life Study Using Previously Collected Data. Can J Aging . 2020;39:145–55. doi: 10.1017/S0714980819000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stacey D, Légaré F, Boland L, et al. 20th Anniversary Ottawa Decision Support Framework: Part 3 Overview of Systematic Reviews and Updated Framework. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:379–98. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20911870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, et al. Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26:1802–11. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Green L, McNeil K, Korossy M, et al. HELP for behaviours that challenge in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:S23–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]