Abstract

Objective

To qualitatively and quantitatively synthesize the literature on the efficacy and safety of magnetic seizure therapy (MST) in psychiatric disorders.

Methods

A literature search was conducted of the OVID Medline, OVID EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science and Cochrane databases from inception to 14 January 2024, using subject headings and key words for “magnetic seizure therapy.” Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), post-hoc analyses of RCTs, open-label trials, or case series investigating MST in adults with a verified psychiatric diagnosis and reporting on two possible primary outcomes (1) psychiatric symptom reduction (as measured by validated rating scale) or (2) neurocognitive outcomes (as measured by standardized testing), were included. Abstracts, individual case reports, reviews and editorials were excluded. Extracted data included: (1) basic study details; (2) study design; (3) sample size; (4) baseline demographics; (5) outcome data (including secondary outcomes of suicidal ideation and adverse events); and (6) stimulation parameters. Cochrane's risk of bias tool was applied. A quantitative analysis was conducted for the depression studies, using Hedge's g effect sizes.

Results

A total of 24 studies (n = 377) were eligible for inclusion. Seventeen studies in depression (including three RCTs), four studies in schizophrenia (including one RCT), one study in bipolar disorder, one study in obsessive-compulsive disorder and one study in borderline personality disorder were summarized. We found no significant difference in depressive symptom reduction between MST and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in randomized, controlled trials (g = 0.207 towards ECT, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.132 to 0.545, P = 0.232). We found a significant reduction in depressive symptoms overall with MST in the pooled RCT and open-label analysis (g = 1.749, CI 1.219 to 2.279, P < 0.005). It is suggested that MST has modest cognitive side effects.

Conclusions

Large-scale RCTs are necessary to confirm early signals of MST as an effective intervention in psychiatric disorders with a cognitive profile that is potentially more favourable than ECT.

Keywords: magnetic seizure therapy, electroconvulsive therapy, convulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder

Abrégé

Objectif:

synthétiser qualitativement et quantitativement la documentation sur l’efficacité et l’innocuité de la thérapie par convulsions magnétiques (magnetic seizure therapy, MST) dans les cas de troubles psychiatriques.

Méthodologie:

une recherche documentaire a été effectuée dans les bases de données Ovide MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science et Cochrane depuis leur création jusqu’au 14 janvier 2024, en utilisant les vedettes-matières et les mots-clés pour rechercher « magnetic seizure therapy ». Des essais cliniques randomisés (ECR), des analyses a posteriori d’ECR, des essais ouverts ou des études de séries de cas portant sur la MST chez des adultes ayant fait l’objet d’un diagnostic psychiatrique vérifié et faisant état de deux résultats primaires possibles (1) la réduction des symptômes psychiatriques (mesurée par une échelle d’évaluation validée) ou (2) les résultats neurocognitifs (mesurés par des tests standardisés), ont été inclus. Les résumés, les études de cas individuelles, les revues et les éditoriaux n’ont pas été pris en compte. Les données extraites étaient les suivantes : (1) informations sur l’étude de base; (2) conception de l’étude; (3) taille de l’échantillon; (4) données démographiques de référence; (5) données relatives aux résultats (y compris les résultats secondaires concernant les idées suicidaires et les événements indésirables); (6) paramètres de stimulation. L’outil d’évaluation du risque de biais de Cochrane a été appliqué. Une analyse quantitative a été réalisée sur les études portant sur la dépression, en utilisant les tailles d’effet calculées à l’aide du g de Hedge.

Résultats:

au total, 24 études (n = 377) ont été retenues. Dix-sept études sur la dépression (dont trois ECR), quatre études sur la schizophrénie (dont une ECR), une étude sur le trouble bipolaire, une étude sur le trouble obsessionnel-compulsif et une étude sur le trouble de la personnalité limite ont été résumées. Nous n’avons pas constaté de différence significative en ce qui concerne la réduction des symptômes dépressifs entre la MST et la thérapie électroconvulsive (TEC) dans les essais cliniques randomisés (g = 0,207 pour la TEC, intervalle de confiance de 95% [IC] −0,132 à 0,545, p = 0,232). Nous avons constaté une réduction significative des symptômes dépressifs dans l’ensemble avec la MST dans l’ECR groupé et l’analyse ouverte (g = 1,749, IC 1,219 à 2,279, P < 0,005). Il semble que la MST ait des effets secondaires cognitifs mineurs.

Conclusions:

des ECR à grande échelle sont nécessaires pour confirmer les indications précoces de la MST en tant qu’intervention efficace pour les troubles psychiatriques au profil cognitif potentiellement plus favorable que la TEC.

Introduction

First-line and second-line treatments do not produce meaningful improvement in an important subset of patients. Even with multiple medication trials and non-invasive neurostimulation approaches, there are significant proportions of patients that do not respond. For example, up to 30% of patients with depression do not respond to pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy 1 and response rates for interventions like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) range from 40% to 50%. 2 In patients with bipolar depression, up to 48% 3 do not respond to first-line interventions, and many patients with schizophrenia struggle with persistent symptoms despite adequate antipsychotic treatment. 4

The spectrum of brain stimulation treatments has expanded in recent years with proliferation of non-invasive neurostimulation approaches that include rTMS, transcranial direct current stimulation, transcranial alternating current stimulation, and others. 5 As an example, rTMS could be useful after one or more failed antidepressant trials and offers specific benefits: an office-based treatment without anesthesia, limited side effects and potentially rapid response. 6 Yet, we see that there are those with definite non-response to rTMS or modest improvement failing to meet remission—particularly patients with more severe baseline depressive symptoms or comorbidities. 7 Directing non-responders towards electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective next step in depression treatment, yielding a 60–80% response rate.8–10 Despite its clear benefits, there are some drawbacks to the use of this invasive treatment. Contemporary studies of patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) are showing somewhat lower response rates to ECT compared to earlier studies.11,12 ECT continues to have lower patient acceptance due to negative perceptions and concern over adverse cognitive effects. 13 The cognitive side effects can be impairing and are well-described: prolonged post-treatment disorientation, anterograde amnesia and possible retrograde amnesia.14–16

Thus, there is the need for new interventional treatments, which maintain efficacy with a more favourable side effect profile. First described in 2000, magnetic seizure therapy (MST) is emerging as a promising candidate treatment. MST uses repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation instead of direct electrical current to induce a generalized seizure. 17 The promise of lower side effects is attributed to a more controlled and focal seizure onset and spread. 18

In the 2016 CANMAT guidelines, MST was listed as an investigational treatment, with level three evidence for acute efficacy and tolerability. This was based primarily on the results of smaller randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized, controlled prospective trials or case series. 19 Since that time, there has been several studies exploring different aspects of this treatment in patients with depression and also other disorders.

Despite growing interest, there have been only four systematic reviews published on MST.20–23 Those published tend to be narrow in focus, for example, concentrating solely on unipolar depression or schizophrenia. They also tend to have restrictive inclusion criteria, excluding smaller research reports other than RCTs. As such, the aims of this study were to: (1) conduct a systematic review of the efficacy (reduction in psychiatric symptoms and suicidality) and safety of MST (neurocognitive and adverse effects) in all psychiatric disorders (2) conduct a quantitative analysis of these outcomes where sufficient data exists and a qualitative analysis where the data are insufficient.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted of the OVID Medline, OVID EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, from inception to 14 January 2024. This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting checklist 24 (included in Supplemental Materials). It was further registered in PROSPERO (PROSPERO identifier: CRD42024502157).

Search Strategy

The search strategy was first designed, tested and revised in OVID MEDLINE in collaboration with a health sciences librarian. It was then translated and run in the remaining databases.

The search strategies utilized database-specific subject headings and keywords to capture the central concept of MST. The search terms (magnetic seizure therapy) OR (seizure therap*) OR (magnetic convulsive therap*) OR (magnetic neurostimulat*) OR (magnetic brain stimulation*) OR (magnetic seizure induc*) OR (magnetic neuromodulation) OR (magnetic seizure treatment) OR (Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation/ and seizure) were entered. Specific psychiatric disorders were not added as conjunctive search terms, as MST is an emerging field and limited in use at this time. No study type or language limits were applied. Unpublished studies were not sought as part of this systematic review. Please see Supplemental Materials for full details of the search strategies.

Inclusion Criteria

Selected studies were required to meet the following inclusion criteria:

RCTs, open-label trials, retrospective analyses of larger RCTs, or case series.

In adults (age >18 years old) with a valid diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder according to a recognized diagnostic manual (i.e., The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth or Fifth edition, or the International Classification of Diseases- Eleventh edition) or according to a clinician.

Reporting the effects of MST on two possible main outcomes, either symptom improvement (as measured by a validated rating scale) AND/OR cognitive impairment (as measured by change in standardized cognitive measures).

If an RCT format, with the main comparators being placebo or sham MST, ECT, other interventional treatments (eg. rTMS), or first-line pharmacotherapy.

The full text was available in English.

Our systematic review was meant to provide a more comprehensive overview of the literature. Studies were not limited by the inclusion of comorbid disorders. Only abstracts, individual case reports, reviews and editorials (including letters to the editor) were excluded. Non-traditional treatment schedules (e.g., accelerated) and continuation MST formats were excluded from analyses.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest for this systematic review were symptomatic improvement on a validated symptom rating scale and cognitive adverse effects as measured by a validated cognitive rating scale. Additional outcomes included reduction in suicidal ideation (as measured by validated suicide rating scale) and other adverse effects.

Screening and Data Extraction

All titles and abstracts identified by the literature search were independently reviewed for study inclusion by two authors, JP and LZ. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions with a senior author, DMB. If the study details were unclear from the abstract, the full text was retrieved for more in-depth assessment. The same process detailed above was applied for the next round of full text review.

The data was extracted and managed using the Covidence software program. Data was independently extracted by two authors, JP and LZ. The extracted data highlighted: (1) basic study details (e.g., authors, year published, country published); (2) study design; (3) sample size; (4) baseline demographics (age, sex, treatment setting); (5) outcome data (symptom scale reduction, neurocognitive measures, adverse events); and (6) treatment number and stimulation parameters. For missing data, authors were contacted once by email; if no response, only available data was analyzed. Cross-referencing clinical trial investigation numbers identified studies derived from a single sample; in these cases, the study with the largest available dataset was used.

Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis compared the differences in primary outcomes between MST and ECT in RCTs. The focus on RCTs was chosen for the most rigorous comparison between the two treatments. A sensitivity analysis of study design was then conducted to include non-RCT (e.g., open-label) studies comparing MST to ECT. Finally, all studies—regardless of study design and with or without ECT comparator—were pooled for analysis of primary outcomes of MST alone. There were no planned subgroup analyses. For those studies not eligible for meta-analysis, we completed a narrative synthesis of study findings.

R version 4.3.2 25 was used for basic data proceeding, and the meta-analyses were performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 4 software. 26

Hedge's g

Given that most studies have small sample sizes, we used Hedge's g to estimate the effect size for continuous data. The effect size was calculated based on the mean difference between the baseline and endpoint scores in the primary scale, standardized by the pooled standard deviation (within group if no comparator in study or between-groups if comparator). This standardization allows comparison across different study scales and also computes study weights to include in the analysis. 27 Within the standard error, an estimate of the pre-post correlation coefficient was based on calculation from data of two of the included studies.28,29 The correlation coefficient used in this study was the average of the two estimates. A random effects model was used considering study heterogeneity would be considerable. This model assumes that true effect size could vary between studies, as they represent random samples within a larger population.

Test of Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic and was interpreted as suggested by the Cochrane Handbook: 0–30% uncertain, 30–50% moderate and >50% substantial heterogeneity. 27 A funnel plot was generated to examine publication bias for each analysis (please see Supplemental Materials).

Risk of Bias Assessment

The quality of studies included was assessed by two independent authors (JP, LZ) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tools. More specifically, for RCTs, six domains were assessed: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, selective outcome reporting and missing data. An overall score divided studies into low, moderate (some concerns) or high risk. 30 For non-controlled studies, potential for confounding, selection of participants, classification of interventions, deviation from intended intervention, measure of outcomes, missing data and selective reporting were the domains assessed. The resulting score placed studies in low, moderate, serious or critical risk of bias. 31

Results

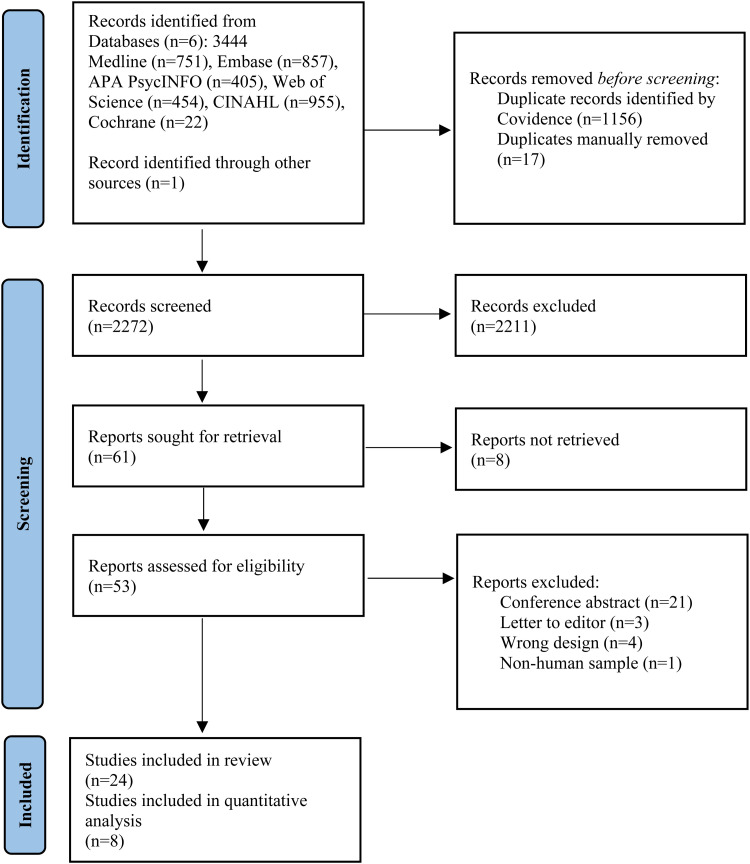

Our search yielded 3444 studies to be screened, supplemented by one additional article 32 from a journal not-yet-indexed. Full texts of 61 studies were reviewed (see PRISMA flow diagram—Figure 1). A total of 24 studies (n = 377 MST patients) were included in the qualitative analysis. This was divided into 17 studies in depression (n = 273), four in schizophrenia (n = 59), one in bipolar depression (BD) (n = 26), one in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (n = 10), and one in borderline personality disorder (BPD) (n = 9). Within depression, there were three RCTs comparing MST with ECT,28,33,34 one post-hoc analysis of an RCT, 35 four non-randomized, open-label comparison with ECT studies,36–39 eight open-label single arm studies,29,40–46 and one case series. 47 In schizophrenia, there was one randomized, double-blind comparison with ECT, 48 as well as one post-hoc secondary analysis of the RCT, 49 one open-label study 50 and one case series. 51 Bipolar disorder had one open-label trial, 52 though it should be noted that there were often small subgroups of participants with bipolar depression included in some of the depression studies. At this time, there was a single open-label pilot study examining MST in OCD. 53 Finally, there was one open-label feasibility trial 32 of conjoint MST and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) in suicidal patients with BPD comorbid with TRD. Full study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Study Design and Demographic-Clinical Characteristics of Subjects Included in Analysis.

| Study name | Country | Study design | Sample size (n=) | Diagnosis | Demographics Age: mean (SD) Women: n (%) |

Primary outcomes | Secondary outcomes | Comparator | Main outcome | Suicide scale | TRO | Neurocognitive outcomes | AEs (incl. serious) | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | ||||||||||||||

| Wang 2020 | Beijing, China | Non-randomized, open-label pilot trial | 15 | MDD (DSM-V) Clinical |

IP + OP Age: 31.9 (10.9) Women: 11 (73) |

HDRS17 | HAMA RBANS Stroop |

N/A | *Reduction HDRS | N/A | N/A |

*Improved RBANS ns Δ: Stroop |

Dizziness (53%) Myalgias (40%) Transient lisp (13%) Transient fever (7%) No serious AEs 0 dropout |

Critical |

| ⇒ Wang 2019 | Beijing, China | Case series | 3 | MDD (DSM-IV) Clinical |

IP + OP Age: 42 (5.0) Women: 1 (33) |

HDRS17 | HAMA RBANS Stroop |

N/A | 2 responders 1 decrease HDRS by 27% |

N/A | N/A | Improved RBANS Decreased Stroop |

No post-MST delirium No serious AEs 0 dropout |

Critical |

| Kayser 2019 | Bonn, Germany | Initially randomized, controlled open-label, then switch to single-arm open-label trial | 38 | TR-MDD BD I/II (DSM-IV) Clinical |

IP + OP Age: 47.2 (10) Women: 19 (50) |

HDRS-28 | Response Remission HSRD sub-items |

vs. BP RUL-ECT then single-arm |

*Reduction HDRS Response (68.4%) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A 0 dropout |

Moderate |

| ⇒ Kayser 2011 | Bonn, Germany | Randomized, controlled open-label trial | 10 (20 total) |

TR-MDD BD I/II (DSM-IV) Clinical |

IP + OP Age: 48.8 (8.4) Women: 6 (60) |

MADRS | HDRS28 HAMA BDI SCL-90 Neuropsych |

vs. BP RUL-ECT |

*Reduction MADRS (equivalent to ECT) MST response (60%) |

N/A |

*Faster TRO (vs. ECT) 2:16 min (0:57) |

*Improved geometric forms (vs. ECT) ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests (vs. ECT) |

No AEs, including serious 0 dropout |

Moderate |

| ⇒ Kayser 2015 | Bonn, Germany | Initially randomized, controlled open-label, then switch to single-arm open-label trial | 10 (RCT) 16 (open-label) |

TR-MDD BD I/II (DSM-IV) Clinical |

IP + OP Age: 47.2 (10) Women: 11 (42.3) |

HDRS-28/17 | MADRS HAMA BDI SCL-90 Neuropsych |

vs. BP RUL-ECT then single-arm |

*Reduction MADRS Response (69%) Remission (46%) |

N/A | N/A |

*Improved RVDLT total learning *Improved ROCF recall (immediate, delayed) *Improved VOT *Improved Stroop interference, RWT formal-lexical verbal fluency ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests |

N/A 0 dropout |

Moderate |

| ⇒ Kayser 2020 | Bonn, Germany | Prospective, open-label trial | 10 | TR-MDD TR-BD II (DSM-IV) SCID-I |

IP + OP Age: 42.1 (10) Women: 4 (40) |

AMI-SF | HDRS-28 HAMA MADRS BDI Neuropscyh |

N/A | ns reduction AMI-SF |

N/A | N/A |

*Improved RWT formal-lexical-verbal fluency ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests |

N/A 1 drop-out (MST device defect & repair) |

Moderate |

| White 2006 | Texas, USA | Non-randomized, open, case-matched study | 10 (20 total) |

MDD Unknown |

Not specified Age: 48 (4.0) Women: 6 (60) |

Anesthetic doses EEG-BIS TRO Recovery time |

HDRS17 | vs. BP BF-ECT |

*Faster TRO (vs. ECT) *Reduction succinylcholine (vs. ECT) |

N/A |

*Faster TRO (vs. ECT) 4 min (1) |

N/A | N/A 0 dropout |

Moderate |

| El-Deeb 2020 | Tanta, Egypt | Non-randomized, controlled open-label trial | 30 (60 total) |

MDD (DSM-IV-TR) MINI plus |

Not specified Age: 39.1 (12.6) Women: 17 (56.7) |

HDRS-21 | BDI TRO Neuropsych Columbia ECT AE schedule |

vs. BP BT-ECT vs. BP RUL-ECT |

*Reduction HAMD (MST alone, vs. RUL-ECT but not BT-ECT) | N/A |

*Faster TRO(vs. ECT) 1.83 min (0.87) |

*Improved WMS, VP I & II, Wisconsin CST (MST alone, vs. ECT) |

Body ache

(n = 1) No headache or subjective “memory complaints” No serious AEs 0 dropout |

Moderate |

| Daskalakis 2020 | Toronto, Canada | Prospective, open-label trial | 86 (47 protocol completers) |

MDD +/-

psychotic

features (DSM-IV) SCID-I |

IP + OP Age: 46.9 (13.3) Women: 49 (57.4) |

% response & remission | TRO Neuropsych |

N/A |

*Remission high-freq (vs. low-freq) High-freq rem (33.3%) Mod-freq (19.2%) Low-freq (11.1%) |

N/A |

*Between group difference medium-freq > low-freq > high-freq Overall mean 10.52 min (7.52) |

*Decreased AMI-SF *Improved BVMT-R total recall and delayed recall ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests |

17 serious AEs. Those deemed related to MST: -Emergence mania (n = 1) -Hospitalization from fall/shoulder dislocation (n = 1) -Superficial burn from coil malfunction (n = 1) |

Moderate |

| ⇒ Sun 2016 | Toronto, Canada |

Prospective, open-label trial | 27 (33 total) |

TR-MDD (DSM-IV) SCID |

IP + OP Age: 46 (15.3) Women: 15 (56) |

Beck SSI | Measures cortical inhibition (LICI, N100) | N/A | *Reduction SSI | Primary outcome | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low |

| ⇒ Weissman 2020 | Toronto, Canada | Post-hoc analysis of prospective, open-label trial | 67 | TR-MDD (DSM-IV) SCID-I |

IP + OP Age: 46.3 (13.6) Women: 40 (60) |

Beck SSI | HSRD item 3 | N/A |

*Time-association with SSI Remission 32/67 (47.8%) |

Primary outcome | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate |

| ⇒ Tang 2021 | Toronto, Canada | Prospective, open-label trial | 30 | TR-MDD TR-BD (DSM-IV) SCID |

IP + OP Age: 47.3 (12.8) Women: 20 (66.7) |

Relapse Re-hospitalization |

SSI TRO Neuropsych |

N/A | Relapse 10/30 patients (33.3%) | 17/17 patients sustained remission of SSI | ns: TRO 1st vs last session |

*Improved COWAT (post-acute to post-continuation), *Improved BVMT (baseline to post-acute), *Decreased AMI-SF (baseline to post-acute) (baseline to post-continuation) ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests |

1 serious AE (hypomania relapse) 5 stops due to device malfunction 7 dropouts -worsened anxiety (n = 3) -worsened mood (n = 2) -headache & muscle ache (n = 1) -memory complaints (n = 1) |

Moderate |

| Deng 2023 | Multi-site, USA |

Randomized, double-blind controlled trial | 35 (73 total) |

MDD BD (DSM-IV-TR) SCID |

Not specified Age: 47.7 (15.6) Women: 22 (62.9) |

HDRS-24 % response or remission |

AMT MMSE TRO Columbia ECT AE schedule |

vs. UBP RUL-ECT |

*Reduction HDRS (ns vs. ECT) MST Response (51.4%) MST Remission (37.1%) |

N/A | *Faster TRO (vs. ECT) |

*Decrease disorientation (vs. ECT) *Improved autobiographical recall memory (vs. ECT) specificity (vs. ECT) ns Δ: MMSE (alone, vs. ECT) |

AEs: -Dry mouth -Headache -Nausea -Muscle pain 4 serious AEs in MST group: -Device malfunction (n = 1) -Nausea, vomiting (n = 2) -Tendinitis (n = 1) 6 drop-out -2 from AEs -4 unknown |

Low |

| Polster 2015 | Bonn, Germany | Prospective, controlled, open-label within-subject observational trial | 10 (20 total) |

TR-MDD (DSM-IV) Clinical |

Not specified Age: 43.7 (11) Women: 3 (30) |

Word retrieval (delayed, cued recall) | HDRS-28 BDI |

vs. BP RUL-ECT | ns change in delayed recall treatment vs. control days (MST group) | N/A | N/A |

*Decrease delayed recall (pre-post MST, MST vs healthy controls) *Less worse delayed recall on treatment days (vs. ECT) ns Δ: Cued recall (MST alone, vs. ECT) |

N/A 0 dropout |

Moderate |

| Fitzgerald 2013 | Victoria, Australia |

Prospective, open-label trial | 13 | TR-MDD (DSM-IV) MINI |

Not specified Age: 46.7 (14.8) Women: 10 (76.9) |

MADRS | HDRS-17 BDI BPRS CORE rating of melancholia TRO Neuropsych |

N/A |

*Reduction MADRS Response (38.5%) |

N/A | Mean TRO (n = 4) 82.8 s (14.65) |

ns Δ: All neurocognitive tests |

Emergence awareness (n=“a number of patients”) Headache (n = 1) No serious AEs 1 dropout (lack of MST response) |

Moderate |

| Fitzgerald 2018 | Victoria, Australia | Randomized, controlled double-blind pilot trial | 18 (37 total) |

TR-MDD (DSM-IV) MINI |

Not specified Age: 44.6 (14.8) Women: 8 (44.4) |

HDRS-17 | IDS QIDS CORE Neuropsych |

vs. BP RUL-ECT |

*Reduction HDRS (ns vs. ECT) MST response (33.3%) |

N/A | N/A |

*Improved digit symbol coding (vs. ECT) *Improved story memory (alone) *Improved Stroop (alone) ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests |

Emergence awareness (n=“several patients”) No serious AEs 1 drop-out (unable to attend) |

Moderate |

| Zhang 2020 | Beijing, China | Rater-blinded, non-randomized study | 18 (45 total) |

MDD (DSM-IV) Clinical |

IP + OP Age: 29 (8.3) Women: 16 (88.9%) |

RBANS | Response Rremission HDRS-17 HAMA |

vs. BP BF-ECT |

*Improved RBANS *Reduction HDRS (ns vs. ECT) MST response (72.2%) MST remission (81.5%) |

N/A | * Faster TRO in MST (vs. ECT) |

*Improved total RBANS (alone, vs. ECT) *Improved RBANS subscores: immediate memory, delayed memory, attention (alone, vs. ECT) ns Δ: Speech (alone, vs. ECT) Visual spatial memory (alone, vs. ECT) |

N/A 0 drop-out |

Low |

| Schizophrenia | ||||||||||||||

| Tang 2018 | Toronto, Canada |

Non-controlled, open-label pilot trial | 8 | Schizophrenia (DSM-IV) SCID-IV |

Not specified Age: 45.9 (12.3) Women: 1 (12.5) |

BPRS | Response Remission Q-LES-Q TRO Neuropsych |

N/A |

*Reduction BPRS Response in 3/4 and remission 1/4 trial completers |

N/A | ns: Change TRO pre-post MST |

*Decreased AMI-SF ns Δ: Other neurocognitive tests |

No serious AEs 4 drop outs -Anxiety about MST (n = 1) -Perceived lack of benefit (n = 1) -No show (n = 1) -Clinical deterioration after treatment 12 requiring involuntary hospitalization (n = 1) |

Moderate |

| Jiang 2018 | Shanghai, China | Case series | 8 | Schizophrenia (DSM-V) Clinical |

IP only Age: 25.3 (7.0) Women: 6 (62.5) |

PANSS | RBANS | N/A | Reduction PANSS in 5/6 completers Response in completers (50%) |

N/A | N/A | Improved immediate memory (n = -2) Increased delayed memory (n = 2) |

Dizziness

(n = 2) Subjective memory loss (n = 1) One serious AE (suicide attempt after MST #2) 2 drop-outs -family revoked consent after suicide attempt (n = 1) -Could not generate seizure (n = 1) |

Serious |

| Jiang 2021 | Shanghai, China | Randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial | 43 (79 total) |

Schizophrenia (DSM-V) Clinical |

IP only Age: 31.3 (9.3) Women: 24 (55.8) |

PANSS | RBANS | vs. BP BT-ECT |

*Reduction total & positive PANSS (ns vs. ECT) MST response (55.8%) |

N/A | N/A |

*No change total RBANS (vs. worse in ECT) * Improved immediate memory subtest (vs. ECT) *Improved language subtest (vs. ECT) ns Δ: Other RBANS subtests |

4 serious AEs/drop-outs -Liver dysfunction

(n = 1) -Hypotension (n = 1) -Conjunctival hemorrhage (n = 1) -Swelling right arm (n = 1) |

Moderate |

| ⇒ Li 2022 | Shanghai, China | Sub-analysis of randomized, double-blind, controlled trial | 18 (34 total) |

Schizophrenia (DSM-V) Clinical |

IP only Age: 32.1 (11.3) Women: 9 (50) |

PANSS RBANS |

Serum BDNF MRI scanning |

vs. BP BT-ECT | ns effect on hippocampal volumes (vs *increased in ECT) | N/A | N/A |

*Increased language score (vs. ECT) *Improved RBANS immediate memory (vs. ECT) ns Δ: Other RBANS subtests |

4 serious AEs/ drop-outs -Liver dysfunction (n = 1) -Hypotension (n = 1) -Cancer diagnosis (n = 1) -Worn out MST coils (n = 1) |

Moderate |

| Bipolar disorder | ||||||||||||||

| Tang 2020 | Toronto, Canada | Non-controlled, open-label trial | 26 (20 protocol completers) |

TR-BD (DSM-IV) SCID |

Not specified Age: 47.3 (14.2) Women: 17 (65.4) |

HDRS-24 | TRO Neuropsych |

N/A |

*Reduction HDRS Response 38.5% Remission 23.1% |

N/A | Mean TRO 8.51 min (4.79) |

*Decreased AMI-SF pre-post ns Δ: 23 other neurocognitive tests |

4 serious AEs (first 2 possibly related to MST): -Hypomanic episode (n = 1) -Fall and dislocated shoulder (n = 1) -Gallbladder removal (n = 1) -Myocardial infarction (n = 1) |

Moderate |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | ||||||||||||||

| Tang 2021 | Toronto, Canada | Non-controlled, open-label pilot | 10 (7 completers) |

OCD (DSM-IV) SCID-IV |

Not specified Age: 37 (10.2) Women: 2 (20%) |

Y-BOCS resp/remission | QIDS-SR SSI Q-LES-Q-SF Neuropsych |

N/A | ns: Change YBOCS 1 response 0 remission |

ns: SSI change |

ns Change TRO pre-post MST Mean TRO 13.04 min (14.06) |

*Decreased AMI ns Δ: All other neurocognitive tests |

No serious AEs | Moderate |

| Borderline personality disorder | ||||||||||||||

| Traynor 2023 | Toronto, Canada | Open-label case-control | 9 MST + DBT (19 total) |

BPD + TRD (SCID-IV & IPDE-10) |

Not specified Age: 301. (9.4) Women: 9 (100%) |

MSSI HDRS-24 |

QIDS-SR ZAN-BPD YMRS Neuropscyh |

DBT only |

*Reduction MSSI (sustained at 4months) ns Δ: Reduction HDRS (non-sustained) |

Primary outcome | Mean TRO 9.08 min (3.07) |

*Decreased D-KEFS total switch (pre-post, both groups) *Decreased D-KEFS category switch total correct (pre-post, both groups) ns Δ: All other neurocognitive tests |

3 serious AEs, unrelated to MST -Attempted suicide (n = 1) -Ureteroscopic surgeries (n = 2) |

Moderate |

Note:

⇒ = secondary study, using duplicate patient population.

TRO = time to re-orientation; AE = adverse events; MDD = major depressive disorder; TR = treatment-resistant; BD = bipolar disorder; SCID = structured clinical interview for DSM; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; IPDE = International Personality Disorder Examination; IP = inpatient; OP = outpatient; BP = brief pulse ECT (pulse width 0.5–2.0 ms); UBP = ultrabrief pulse ECT (pulse width 0.3 ms); HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; AMI-SF = Autobiographical-Memory Interview Short-Form; EEG-BIS = electro-encephalogram bispectral index; BSSI = Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; RBANS = Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia; YBOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; MSSI = Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; SCL-90=Symptom Checklist 90; AMT = Autobiographical Memory Test; MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; Q-LES-Q-SF=Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and Satisfaction Questionnaire Short-Form; BDNF = Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor; MRI = Magnetic Resonance Imaging; QIDS-SR = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report; ZAN-BPD = Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; Neuropsych = extensive neuropsychological testing; RVDLT = Rey Visual Design Learning Test; ROCF = Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure; VOT = Hooper Visual Organization Test; RWT = Regensburger Wortflüssigkeits-Test; WMS = Wechsler Memory Scale; VP I & II = Visual Paired Associates I & II; Wisconsin CST = Card Sorting Test, BVMT-R = Brief Visuo-Spatial Memory Test Revised; COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; D-KEFS = Delis Kaplan Executive Function System; N/A = data not available or not reported.

Statistically significant P < 0.05; ns = non-significant; Δ= change.

Table 2 provides an overview of the MST parameters used in retrieved studies. Earlier studies chose between low-, medium- and high-frequency stimulation. More recent studies have largely adopted a high-frequency stimulation of 100 Hertz (Hz). There are two commonly used positions in most studies, the vertex and frontal cortex at midline. For ECT, right unilateral (RUL) ECT has been the most common comparator in depression, followed by bifrontal and then bitemporal. Schizophrenia studies have only compared MST to bitemporal ECT.

Table 2.

Detailed Treatment and Stimulation Parameters of Included Studies.

| Study | Total treatment # | Location | Threshold determination | Stimulation frequency | Pulse intensity | Train duration | Max pulses per train |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major depressive disorder | |||||||

| Wang 2020 | Daily 6 Tx |

Vertex MagStim 130 mm circular coil |

Titration | 100Hz | 100% | Up to 10 s | 1000 |

| ⇒ Wang 2019 | Daily 6 Tx |

Vertex MagStim 130 mm circular coil |

Titration | 100Hz | 100% | Up to 10s | 1000 |

| Kayser 2019 | Freq NR 8–12 Tx |

Vertex (Cz position) MagPro twin coil |

Titration 6x ST |

100Hz | 100% | Up to 8 s | 800 |

| ⇒ Kayser 2011 | 2x per week 12 Tx |

Vertex MagPro twin coil 13cm pw 370us |

Titration 3–6x ST |

100Hz | 100% | Up to 6 s | 600 |

| ⇒ Kayser 2015 | 2x per week 12–22 Tx |

Vertex MagPro pw 0.2ms |

Titration 6x ST |

100Hz | 100% | Up to 10s | 1000 |

| ⇒ Kayser 2020 | 2x per week Tx mean = 8.9 |

Vertex (Cz position) MagPro twin coil pw 0.28 ms |

Fixed dosing | 100 Hz | 100% | NR | 600 pulses then increased by 50 if seizure < 15s |

| White 2006 | Freq NR 10–12 Tx |

Position NR Custom modified MagStim device pw 500us |

Fixed dosing 1.3x ST |

50Hz | NR | 8 s | 400 |

| El-Deeb 2020 | 2x per week 5 Tx |

Vertex MagStim Theta |

Fixed dosing | 100Hz | 100% | 10s | 1000 |

| Daskalakis 2020 | 2–3x per week Until remission or 24 Tx max |

Frontal cortex MagPro with TwinCoil- XS |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4—20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| ⇒ Sun 2016 | 2–3x per week Until remission or 24 Tx max |

Frontal cortex (Fz position) MagPro twin coil |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4 – 20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| ⇒ Weissman 2020 | 2–3x per week Until remission or 24 Tx max |

Frontal cortex MagPro with TwinCoil-XS |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4 – 20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| ⇒ Tang 2021 | 0–2mos: q1w 2–4mos: q2w 4–6mos: q3w 7mo: q4w |

Frontal cortex MagPro with TwinCoil- XS |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4 – 20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| Deng 2023 | 3x per week Until remission or plateau Tx mean = 9.0 |

Vertex MagStim Theta with double-layer round coil |

Titration | 100Hz | 100% | 5 – 10 s | 1000 |

| Polster 2015 | 2x per week 10–12 Tx |

Vertex MagPro with twin 13-cm coil |

Titration At ST |

100Hz | 100% | Average 5–8 s | 1000 |

| Fitzgerald 2013 | 3x per week 18 Tx max |

Vertex Bilateral dual-cone 13-cm MST coil |

Initially fixed (10 s train), then titration | 100Hz | 100% | 4 – 10s | 1000 |

| Fitzgerald 2018 | 3x per week Until response or 15 Tx max |

Vertex MagVenture A/S with bilateral dual 13-cm cone |

Titration | 100Hz | 100% | 4 – 10s | 1000 |

| Zhang 2020 | Day 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9 6 Tx |

Vertex (middle site of P3, P4) MagStim 13-cm coil |

Fixed dosing | 100Hz | 100% | Up to 10 s | 1000 |

| Schizophrenia | |||||||

| Jiang 2018 | 3x per week for 2 weeks, then 2x per week for 2 weeks Total 10 Tx |

Vertex MagPro ×100 pw 370us |

Titration | 25Hz | 100% | 4 – 20 s | 500 |

| Tang 2018 | 2–3x per week Until remission or 24 Tx max |

Frontal cortex (over F3, F4) MagVenture twin coil |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4 – 20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| Jiang 2021 | 3x per week for 2 weeks, then 2x per week for 2 weeks Total 10 Tx |

Vertex MagPro TwinCoil-XS pw 370us |

Titration | 50 Hz | 100% | 4 – 20s | 1000 |

| Li 2022 | 3x per week for 2 weeks, then 2x per week for 2 weeks Total 10 Tx |

Vertex MagPro X100 pw 370us |

Titration | 50Hz | 100% | 4 – 20s | 500 |

| Bipolar disorder | |||||||

| Tang 2020 | 2–3x per week Until remission or 24 Tx max |

Frontal cortex or vertex MagVenture with twin coil |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4 – 20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | |||||||

| Tang 2021 | 2–3x per week Until remission or 24 Tx max |

Frontal cortex or vertex MagVenture with twin coil |

Titration | 25Hz 50, 60 Hz 100 Hz |

100% | 4 – 20s 2 – 20s 2 – 10s |

500 1000 1000 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | |||||||

| Traynor 2023 | 3x per week Up to 15 Tx |

Frontal cortex MagVenture MagPro with Cool TwinCoil |

Titration | 25 Hz | 100% | 4 – 20s | 500 |

Note:

⇒ = secondary study, using duplicate patient population.

NR = not reported; Tx = treatment; pw = pulse width; DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; s = seconds; ST = seizure threshold.

The quantitative analysis was limited to patients with depression as the number of studies allowed this analysis to be conducted. The first analysis of three RCTs comparing antidepressant efficacy of MST versus ECT comprised a total 130 patients. A sensitivity analysis was conducted of both RCTs and open-label studies comparing MST versus ECT, totaling 255 patients. Finally, we examined antidepressant efficacy of MST alone by including all possible studies. After removing secondary studies, five open-label studies (with or without ECT comparator) were combined with the three active MST arms of the RCTs to form the pooled all-studies analysis of 248 MST patients.

MST in MDD

Symptom Improvement

Meta-Analysis of MST Versus ECT on Depressive Symptoms in RCTs

Trials included in this analysis employed a randomized, controlled design, comparing MST to ECT. All three studies measured depressive symptoms via the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), 54 a widely-used, clinician-administered scale for depression. However, they employed slightly different versions: the 17-item, 24-item and 28-item versions.

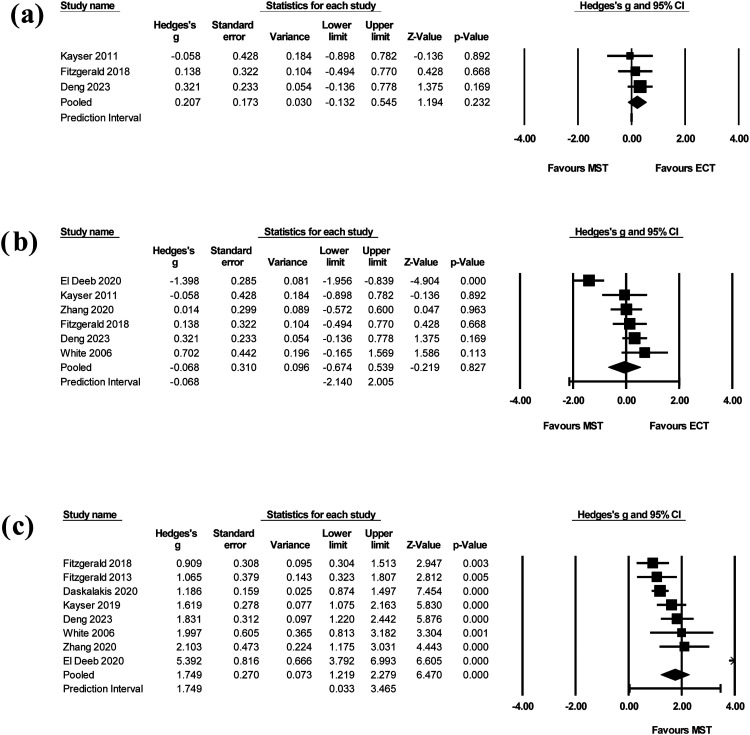

In the three trials analyzed, the cumulative effect size was 0.207 in favour of ECT (95% CI −0.132 to 0.545, Z-value = 1.194) (Figure 2(a)). The change in depressive symptoms for MST was not significantly different than for ECT (P = 0.232). It should be noted that all three confidence intervals cross zero, signifying likely no difference between groups. Further, one RCT 33 was weighted at 54.9%, meaning it contributes much more importantly to pooled results than the other studies. The test for heterogeneity showed no inconsistency (I2 = 0%, Q-value = 0.667). It is not likely to be a reliable measure due to lack of power and potential for bias with only three studies. Both fixed and random effects models were computed with no statistical difference in the results.

Figure 2.

(a) Forest plot of MST versus ECT on depressive symptoms in RCTs. The cumulative effect size across three studies was 0.207 in favour of ECT (95% CI −0.132 to 0.545, Z-value = 1.194, P = 0.232). (b) Forest plot of MST versus ECT on depressive symptoms across RCTs and open-label trials. The cumulative effect size across six studies was −0.068 in favour of MST (95% CI −0.674 to 0.539, Z-value = −0.219, P = 0.827). (c) Forest plot of MST on depressive symptoms across all studies. The pooled effect size across eight studies included was 1.749 (95% CI 1.219 to 2.279, Z-value = 6.740, P < 0.005).

MST = magnetic seizure therapy; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy.

Meta-Analysis of MST Versus ECT on Depressive Symptoms Across RCTs and Open-Label Studies

A sensitivity analysis involved all studies comparing MST to ECT, using either randomized or open-label designs. Six studies were included. One open-label study only reported the baseline HDRS, not endpoint, and was thus excluded. 38

In the six studies, the cumulative effect size was −0.068 in favour of MST (95% CI −0.674 to 0.539, Z-value = -0.219) (Figure 2(b)). Again, the change in depressive symptoms was not significantly different than for ECT (P = 0.827). All but one study's confidence interval crossed zero. All studies contributed a similar weight between 14% and 19% in the analysis. Of note, when the main outlier study was removed, 37 the cumulative effect size resembled that of the previous analysis: a cumulative effect size of 0.214 in favor of ECT (95% CI −0.064 to 0.492). There was again no significant difference in depressive symptom reduction between MST and ECT (P = 0.131). The I2 statistic was 82% (Q-value = 27.968), indicating substantial heterogeneity. It should again be highlighted that this analysis contained less than 10 studies, affecting the interpretability of this measure. There was no significant difference between fixed and random effects models.

Meta-Analysis of MST on Depressive Symptoms Across all Studies

The final analysis combined the active MST arms of RCTs with all possible open-label studies with or without ECT comparator. Amongst the open-label studies, three studies40,44,47 were not included as they investigated MST in alternative formats, and five secondary studies28,35,41,42,45 were excluded. The pooled effect size across eight studies included was 1.749 (95% CI 1.219 to 2.279, Z-value = 6.740) (Figure 2(c)). The change in depressive symptoms after MST treatment was significant (P < 0.005). Most studies contributed similar weight or importance to the analysis, between 6% and 17%. The test for heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 80%, Q-value = 34.729). Both fixed and random effects models were employed, with no significant difference in results.

Qualitative Analysis of MST on Suicidality

Only three studies35,44,45 reported on suicidality. However, these studies used the same sample of patients. The main clinical analysis by Weissman et al. was a post-hoc analysis of an open-label, prospective trial of 67 patients with TRD and baseline suicidality. MST treatment occurred until remission (0 on Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI)) or a maximum of 24 sessions. Thirty-two patients achieved remission (47.8%), with a mean decrease in Beck SSI from 10.9 (4.9) to 6.0 (6.6) (P < 0.001). Tang et al. followed a subset of the remitters into continuation MST (decreasing frequency of MST sessions, with additional boosters as needed), totaling 17 patients. By study end, all 17 patients (100%) had continued remission of their suicidality.

Cognitive and Other Adverse Effects of MST

Fourteen studies examined a minimum of one neurocognitive measure before and after MST. Excluding those with alternative MST formats40,44,47 and secondary studies, 42 the ten remaining studies utilized different measures, such as time to reorientation, Folstein Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE), the autobiographical memory test (AMT), the short-form autobiographical memory interview (AMI-SF), and the repeatable battery for neuropsychological status (RBANS). Seven studies reported either non-significant pre-post changes or improvement in all cognitive measures, two reported worsening of certain pre-post cognitive measures (namely autobiographical memory, delayed recall), and one study provided insufficient information. The mean time to orientation in reported studies is 3.99 min (0.65).

In addition, there were seven studies that examined the cognitive effects of MST versus ECT specifically. All seven report more favorable neurocognitive outcomes in MST than ECT in varied domains. The time to re-orientation was unanimously shorter in MST compared to ECT in the reported studies.28,33,34,36–39 If limited to randomized, controlled trials, MST carried less impairment in the AMT, 33 neglect (geometric forms) 28 and digit symbol coding. 34

Only six studies reported on adverse effects beyond cognition after those with alternative MST formats and duplicate data were removed. The commonly reported adverse effects amongst studies were: dizziness, headache, muscle ache and nausea. Two studies34,46 from the same research group reported emergence awareness in MST, despite using identical doses of succinylcholine and propofol to ECT. Three of the four studies28,33,34,37 with an ECT comparator reported higher adverse effects in ECT compared to MST. Regarding serious adverse events, the majority (83%) of studies reported no serious adverse events with MST. The one exception 29 reported a high absolute number, but only 3.4% of the serious adverse events were determined to be related to MST. The four studies with ECT comparator showed no serious adverse events in the MST arms.

Please refer to Table 1 for full details about the neurocognitive and other adverse effects of MST.

MST in Schizophrenia

Four studies examined the effects of MST in patients with schizophrenia. In general, the four studies showed antipsychotic efficacy, with improved or only slightly worsened cognition. The two early studies50,51 were smaller, open-label pilot trials, first assessing feasibility and acceptability in this population. The third study 48 by Jiang et al. is a randomized, controlled, double-blind study, comparing the effects of MST versus bitemporal ECT. The final study 49 was a secondary sub-analysis of the same RCT, with a specific focus on the serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) biomarker and hippocampus structural changes.

Symptom Improvement (Including Suicidality)

All four studies reported a reduction in psychiatric symptoms following treatment with MST. In the first study, 50 eight TR-schizophrenia patients underwent up to 24 sessions of MST. All subjects had a significant reduction in Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) from 42.6 at baseline to 32.4 after MST (P = 0.018). In the second pilot, 51 eight inpatients with schizophrenia received up to 10 sessions of add-on MST over four weeks. Only six patients received five or more sessions. Within this group, there were mean reductions of 27.3 and 11.2 in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score and PANSS positive score (P = 0.009) respectively. In the sole RCT, 48 79 inpatients were randomized to receive either 10 sessions of MST (n = 43) or ECT (n = 34) over four weeks. The per-protocol analysis (those receiving five or more sessions) of 37 patients treated with MST showed a significant reduction of 10 (7.5) in PANNS general score (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in symptom reduction or response rates between the MST and ECT groups.

There was no systematic reporting of suicidality, via scale or other means, in the four studies. One pilot study 51 did report one suicide attempt in a patient after the second MST treatment, but deemed it unlikely to be related to MST treatment.

Cognitive and Other Adverse Effects

All four trials examined the neurocognitive effects of MST in patients with schizophrenia. Excluding the post-hoc analysis, the remaining studies used either the RBANS or other neuropsychological testing. In the first pilot study, 50 a worsening in the AMI-SF after MST was reported, though all other measures did not change significantly. In the second, 51 only three of eight patients could complete the RBANS, and the post-treatment scores were either stable or improved. Finally, the RCT demonstrated minimal RBANS changes in the 43 MST patients of the intention-to-treat analysis, while there was a worsening the ECT group (P < 0.05). There was significantly greater impairment in patients treated with ECT in the immediate memory and language subtests specifically. In summary, all studies in patients with schizophrenia demonstrated stable or improved cognitive testing following MST treatment, except for worsened autobiographical memory in one pilot study. The one trial comparing MST versus ECT noted significantly less impairment in patients with schizophrenia treated with MST.

Most studies did not report on common adverse effects. The main serious adverse events were either thought to be related to MST (e.g., conjunctival hemorrhage) or not related to MST (suicide attempt mentioned above, liver dysfunction secondary to anesthesia and hypotension secondary to anesthesia).

MST in Bipolar Disorder

One study 52 examined specifically the effects of MST in patients with treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Twenty-six patients were treated with up to 24 sessions of MST of varied orientations: low-, medium- or high-frequency prefrontal MST or high-frequency vertex MST. These 26 adequate-trial completers (received eight or more MST sessions) had a statistically significant reduction (P < 0.001) in HDRS-24 from baseline scores of 28.1 (4.4) to end of treatment scores of 17.8 (8.5). The corresponding effect size was large (d = 1.25, 95% CI 0.42–1.57) and slightly larger for the per-protocol completers. There was no specific data reported on suicidality.

This study also assessed 24 different neurocognitive measures at baseline and after MST. There was a statistically significant mean decrease of 18.9% (P < 0.001) on the AMI-SF, while the remaining 23 measures of cognition remained stable. Time to reorientation was 8.5 min (4.8). Otherwise, there were two serious adverse events reported, thought to be related to MST. The first was the emergence of hypomania days after protocol completion in a patient, while the second was a fall and shoulder dislocation in another patient.

As mentioned, six studies investigating MST in depression included a small proportion of patients with BD. However, there were no subgroup analyses performed and thus it was not possible to disentangle them from the larger unipolar depression cohort.

MST in OCD

One study 53 examined the effects of MST in patients with OCD. Ten patients with moderate-severe OCD, resistant to SSRI-medications, were treated with up to 24 MST treatments. Seven patients underwent an adequate trial (8 or more MST treatments), and only one achieved response. There was further no significant change in Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score from baseline to endpoint in this group (Z = −0.08, P = 0.93). Similarly, there was a non-significant change in suicidality, as measured by the SSI (Z = −1.08, P = 0.28).

The mean time to reorientation for adequate trial completers was 13.0 (14.1) minutes, not significantly different than baseline (Z = −0.76, P = 0.45). A significant difference was found for the baseline-to-endpoint AMI-SF (Z = −2.21, P = 0.03), but no other neurocognitive outcomes. There were no serious adverse events reported amongst trial participants.

MST in BPD

One study 32 examined MST combined with psychotherapy in patients with BPD. Nineteen patients with moderate-severe suicidality and BPD comorbid with TRD were allocated to DBT alone (one hour of individual plus one hour of group therapy per week) versus MST (total of 15 treatments) combined with DBT. Only the MST-DBT group (n = 9) showed a significant reduction in suicidality as measured by Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI) (β = −12.03 CI −19.24 to −4.82, (SE) = 3.75; t[31] = −3.21; P < 0.01), sustained at four-month follow-up. Only the MST-DBT arm also showed improvement in HDRS and Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) after treatment.

The mean time to reorientation was 9.08 (3.07) minutes. A significant difference was found in the baseline-endpoint Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) category switch total correct (F[1,16] = 7.98; P = 0.01) and total switch (F[1,16] = 5.07; P = 0.04) for both groups. There were no other significant effects found in any of the other neurocognitive measures, including autobiographic memory. There were three serious adverse events unrelated to MST intervention.

Discussion

This study provides an up-to-date quantitative and qualitative synthesis of the efficacy and tolerability of MST in psychiatric disorders. We found 17 studies in depression (including three RCTs), four studies in schizophrenia (including one RCT), one study in bipolar disorder, one study in OCD and one study in BPD. A quantitative analysis of the patients with depression (n = 248) revealed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms with MST, without significant difference to ECT in the smaller RCT analysis (n = 130). A sensitivity analysis of RCTs and non-randomized studies comparing MST versus ECT (n = 255) then confirmed no significant difference in efficacy between the two treatments.

The antidepressant effects of MST found in this review are reinforced by recent studies. Chen et al. 21 performed a meta-analysis of 285 patients with depression from 10 non-randomized studies comparing MST with ECT. The results showed similar antidepressant efficacy, with shorter reorientation and less impaired recall in MST. Similarly, Cai et al. 22 did not find significant differences in study-defined remission and depressive symptom improvement between ECT and MST in four RCTs (n = 86). Taken together, evidence for the similarity in clinical efficacy of MST is continuing to mount and would now likely meet the threshold for level 2 evidence from depression guidelines. 19

That said, the preliminary evidence for MST's antidepressant effects requires careful consideration of the context. To start, the comparison to ECT is likely somewhat premature, as existing studies are too small and under-powered to detect true differences. Larger, multi-site RCTs will be necessary to confirm these initial signals, and a large, multi-centre trial is now nearing completion. 55 Furthermore, the existing studies examined MST versus ECT with RUL, bifrontal and bitemporal modalities— demonstrating an uncertainty about the most apt comparator to MST. The largest RCT to date 33 compared MST to ultrabrief pulse RUL-ECT, which may be appropriate, though bilateral ECT is widely considered the most effective form treatment. 56 It is most likely that research groups are simply following historical and institutional norms concerning pulse width, electrode placement, number of treatments and anesthetics. Yet some coherence in research will be necessary in order to truly understand MST's place in the therapeutic continuum and compared to ECT. Lastly, independent of its antidepressant effects, ECT has repeatedly demonstrated unique anti-suicidal properties.57,58 The investigation of MST's potential to reduce suicidality is promising, yet the evidence is still very limited.

Of note, the studies included also demonstrate the wide variation of MST practice in the literature. At this point, the optimal coil type, placement, frequency, pulses per train and treatment course length have yet to be fully determined. One of the included studies compared different stimulation frequencies in 86 patients; the findings indicated that high-frequency stimulation produced the most important antidepressant effects, with less time to orientation. 29 Indeed, the majority of MST trials in depression in the literature have employed a high-frequency stimulation over the vertex. This leaves the alternative treatment modalities open for further exploration. This is not dissimilar from ECT practice, which typically differs based on patient-related factors, treatment factors and institutional-geographic factors.59,60

In general, it is suggested that MST has a more benign cognitive side effect profile. The studies included showed more rapid orientation time and mostly preserved cognitive abilities (even some gains) after MST. For example, the time to reorientation across all reported MST studies was 5.93 min (1.59), while estimates in ECT range from 10 to 30 min.61,62 The anterograde and retrograde amnesia characteristic of ECT14–16 seems to be modest in MST. This is congruent with pre-clinical evidence, in both virtual conducting spheres and non-human primates, suggesting that MST seizure expression is less intense, more focal and more superficial, potentially sparing the deeper hippocampus.63,64 However, the strength of these conclusions is again limited by the low number of studies (typically under-powered due to small sample sizes) and heterogeneous neurocognitive testing across studies. In the future, it will be necessary to synthesize the neuropsychological measures between studies, ensuring common multi-domain testing that accounts for practice effects.

Outside of depressive disorders, there are still very limited conclusions to be drawn about the efficacy and safety of MST. Studies have started to accumulate in schizophrenia, followed by bipolar disorder, and these are likely the next major areas of exploration. There were no MST studies found for other indications of ECT (e.g., catatonia, Parkinson's disease, neurocognitive disorders). A search of the clinical trials online database reveals two upcoming non-inferiority trials between ECT and MST in patients with depression and two upcoming trials between ECT and MST in patients with bipolar depression. 65

Study Limitations

This study had multiple limitations. There is a small number of studies published to date on MST, from a small group of investigators and health centers. The majority of these studies are characterized by small sample sizes and open-label designs, with only a few medium-sized RCTs. As such, the quantitative analysis should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the studies also utilized different MST parameters, number of treatment sessions and outcome measures. There are also differences in ECT comparators. While this is indicative of the “real-world” clinical setting, it makes pooling effect sizes across studies more challenging. Finally, most studies had a short follow-up period of around 1–2 months. Given the high rates of relapse after a successful course of ECT in the first six months, 66 it is essential to determine the durability of MST effects.

Conclusion

MST is evolving as an alternative to ECT in treating severe and refractory psychiatric disorders. There is accumulating literature in depression, followed by bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The potentially safer cognitive profile, with less post-ictal disorientation and amnesia, makes MST a particularly attractive alternative. Larger-scale, RCTs focusing on severe, treatment-refractory illness are needed. They should further make a concerted effort to harmonize neurocognitive outcomes with other studies, as well as include validated suicidality scales. The discrete effects of MST on suicidality have not yet been well characterized in comparison to ECT. Moreover, despite characterizing seizure induction, there are fewer studies exploring neurophysiological correlates in MST. This exploration is essential to uncovering the underlying mechanisms of action of MST. In sum, future research is necessary to reinforce MST as an effective, yet more cognitively-safe, convulsive therapy in our psychiatric armamentarium.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437241301005 for Magnetic Seizure Therapy in Refractory Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La thérapie par convulsions magnétiques pour la prise en charge des troubles psychiatriques réfractaires : revue systématique et méta-analyse by Jake Prillo, Lorina Zapf, Caroline W. Espinola, Zafiris J. Daskalakis and Daniel M. Blumberger in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Reena Besa, information specialist, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, for their help in generating the search strategy.

Footnotes

Data Availability: The datasets used and/or analyzed for this meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: LZ receives a stipend/salary from CAMH as a visiting graduate student. ZJD has received research and equipment in-kind support for an investigator-initiated study through Brainsway Inc and Magventure Inc and industry-initiated trials through Magnus Inc. He also currently serves on the scientific advisory board for Brainsway Inc. His work has been supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Brain Canada and the Temerty Family, Grant and Kreutzcamp Family Foundations. DMB receives research support from CIHR, NIH, Brain Canada and the Temerty Family through the CAMH Foundation and the Campbell Family Research Institute. He received research support and in-kind equipment support for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. He was the site principal investigator for three sponsor-initiated studies for Brainsway Ltd. He also received in-kind equipment support from Magventure for two investigator-initiated studies. He received medication supplies for an investigator-initiated trial from Indivior. He is a scientific advisor for Sooma Medical. He is the Co-Chair of the Clinical Standards Committee of the Clinical TMS Society (unpaid). JP and CWE have no personal conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jake Prillo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5398-8003

Daniel M. Blumberger https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8422-5818

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.John Rush A, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a star*d report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Anderson RJ, Daskalakis ZJ. A study of the pattern of response to rtms treatment in depression. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):746-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (step-bd). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya A, Chen R, Mrudula K, et al. An overview of noninvasive brain stimulation: basic principles and clinical applications. Can J Neurol Sci/Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 2022;49(4):479-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George MS, Lisanby SH, Sackeim HA. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: applications in neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(4):300-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaster TS, Downar J, Vila-Rodriguez F, et al. Trajectories of response to dorsolateral prefrontal Rtms in major depression: a three-d study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(5):367-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haq AU, Sitzmann AF, Goldman ML, Maixner DF, Mickey BJ. Response of depression to electroconvulsive therapy: a meta-analysis of clinical predictors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(10):1374-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, et al. Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ect. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(8):985-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Broek WW, de Lely A, Mulder PG, Birkenhäger TK, Bruijn JA. Effect of antidepressant medication resistance on short-term response to electroconvulsive therapy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):400-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand A, Mathew SJ, Sanacora G, et al. Ketamine versus ECT for nonpsychotic treatment-resistant major depression. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(25):2315-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husain SS, Kevan IM, Linnell R, Scott AI. Electroconvulsive therapy in depressive illness that has not responded to drug treatment. J Affect Disord. 2004;83(2–3):121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson ST, Agbese E, Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA. Identifying recipients of electroconvulsive therapy: data from privately insured Americans. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(5):542-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(12):839-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squire LR, Slater PC, Miller PL. Retrograde amnesia and bilateral electroconvulsive therapy: long-term follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(1):89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lisanby SH, Maddox JH, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Sackeim HA. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(6):581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lisanby SH, Schlaepfer TE, Fisch HU, Sackeim HA. Magnetic seizure therapy of major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(3):303-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng ZD, Lisanby SH, Peterchev AV. Electric field strength and focality in electroconvulsive therapy and magnetic seizure therapy: a finite element simulation study. J Neural Eng. 2011;8(1):016007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milev RV, Giacobbe P, Kennedy SH, et al. Canadian Network for mood and anxiety treatments (canmat) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 4. Neurostimulation treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):561-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang XY, Chen HD, Liang WN, et al. Adjunctive magnetic seizure therapy for schizophrenia: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:813590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M, Yang X, Liu C, et al. Comparative efficacy and cognitive function of magnetic seizure therapy vs. Electroconvulsive therapy for major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai DB, Yang XH, Shi ZM, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy for depression: A systematic review. J Pers Med. 2023;13(3):449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu H, Jiang J, Cao X, Wang J, Li C. Magnetic seizure therapy for people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;6(6):CD012697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Comprehensive meta-analysis software. 4th edn. Englewood, New Jersey: BioStat Inc.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.4 Cochrane; 2023. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

- 28.Kayser S, Bewernick BH, Grubert C, Hadrysiewicz BL, Axmacher N, Schlaepfer TE. Antidepressant effects, of magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy, in treatment-resistant depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(5):569-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daskalakis ZJ, Dimitrova J, McClintock SM, et al. Magnetic seizure therapy (mst) for major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol: Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;45(2):276-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. Robins-i: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Traynor JM, Ruocco AC, McMain SF, et al. A feasibility trial of conjoint magnetic seizure therapy and dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal patients with borderline personality disorder and treatment-resistant depression. Nature Mental Health. 2023;1(1):45-54. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng Z-D, Luber B, McClintock SM, Weiner RD, Husain MM, Lisanby SH. Clinical outcomes of magnetic seizure therapy vs electroconvulsive therapy for major depressive episode: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(3):240-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Elliot D, et al. A pilot study of the comparative efficacy of 100 hz magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy in persistent depression. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(5):393-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissman CR, Blumberger DM, Dimitrova J, et al. Magnetic seizure therapy for suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(8):e207434-e207434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White PF, Amos Q, Zhang Y, et al. Anesthetic considerations for magnetic seizure therapy: a novel therapy for severe depression. Anesth Analg. 2006;103(1):76-contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Deeb FA, Gad E-SA, Kandeel AA, et al. Comparative effectiveness clinical trial of magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy in major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry: Off JAm Acad Clin Psychiatrists. 2020;32(4):239-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polster JD, Kayser S, Bewernick BH, Hurlemann R, Schlaepfer TE. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy and magnetic seizure therapy on acute memory retrieval. J ECT. 2015;31(1):13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Ren Y, Jiang W, et al. Shorter recovery times and better cognitive function-a comparative pilot study of magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy in patients with depressive episodes. Brain Behav. 2020;10(12):e01900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Vila-Rodriguez F, Ge R, et al. Accelerated magnetic seizure therapy (amst) for treatment of major depressive disorder: a pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2020;264(h3v, 7906073):215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kayser S, Bewernick BH, Matusch A, Hurlemann R, Soehle M, Schlaepfer TE. Magnetic seizure therapy in treatment-resistant depression: clinical, neuropsychological and metabolic effects. Psychol Med. 2015;45(5):1073-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayser S, Bewernick BH, Wagner S, Schlaepfer TE. Effects of magnetic seizure therapy on anterograde and retrograde amnesia in treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(2):125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayser S, Bewernick BH, Wagner S, Schlaepfer TE. Clinical predictors of response to magnetic seizure therapy in depression: a preliminary report. J ECT. 2019;35(1):48-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang VM, Blumberger DM, Throop A, et al. Continuation magnetic seizure therapy for treatment-resistant unipolar or bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(6):20m13677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Y, Farzan F, Mulsant BH, et al. Indicators for remission of suicidal ideation following magnetic seizure therapy in patients with treatment-resistant depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):337-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Herring SE, Clinton AM, Downey G, Daskalakis ZJ. Pilot study of the clinical and cognitive effects of high-frequency magnetic seizure therapy in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(2):129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Vila-Rodriguez F, Jiang W, Ren Y-P, Wang C-M, Ma X. Accelerated magnetic seizure therapy for treatment of major depressive disorder: a report of 3 cases. J ECT. 2019;35(2):135-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang J, Li J, Xu Y, et al. Magnetic seizure therapy compared to electroconvulsive therapy for schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:770647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, Zhang X, Jiang J, et al. Comparison of electroconvulsive therapy and magnetic seizure therapy in schizophrenia: structural changes/neuroplasticity. Psychiatry Res. 2022;312(qc4, 7911385):114523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blumberger DM, Downar J, Daskalakis ZJ. A pilot case series of magnetic seizure therapy in refractory schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(SUPPL. 1):S71. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang J, Li Q, Sheng J, et al. 25 Hz magnetic seizure therapy is feasible but not optimal for Chinese patients with schizophrenia: a case series. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang VM, Blumberger DM, Dimitrova J, et al. Magnetic seizure therapy is efficacious and well tolerated for treatment-resistant bipolar depression: an open-label clinical trial. J Psychiatry Neurosci: JPN. 2020;45(5):313-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang VM, Blumberger DM, Weissman CR, et al. A pilot study of magnetic seizure therapy for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(2):161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daskalakis ZJ, Tamminga C, Throop A, et al. Confirmatory efficacy and safety trial of magnetic seizure therapy for depression (crest-mst): study protocol for a randomized non-inferiority trial of magnetic seizure therapy versus electroconvulsive therapy. Trials. 2021;22(1):786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at different stimulus intensities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(5):425-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaster TS, Blumberger DM, Gomes T, Sutradhar R, Wijeysundera DN, Vigod SN. Risk of suicide death following electroconvulsive therapy treatment for depression: a propensity score-weighted, retrospective cohort study in Canada. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(6):435-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rönnqvist I, Nilsson FK, Nordenskjöld A. Electroconvulsive therapy and the risk of suicide in hospitalized patients with major depressive disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leiknes KA, Jarosh-von Schweder L, Høie B. Contemporary use and practice of electroconvulsive therapy worldwide. Brain Behav. 2012;2(3):283-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martin BA, Delva NJ, Graf P, et al. Delivery of electroconvulsive therapy in Canada: A first national survey report on usage, treatment practice, and facilities. J ECT. 2015;31(2):119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sackeim HA, Luber B, Moeller JR, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Nobler MS. Electrophysiological correlates of the adverse cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2000;16(2):110-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sartorius A, Karl S, Zapp A, et al. Duration of electroconvulsive therapy postictal burst suppression is associated with time to reorientation. J ECT. 2021;37(4):247-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cycowicz YM, Luber B, Spellman T, Lisanby SH. Neurophysiological characterization of high-dose magnetic seizure therapy: comparisons with electroconvulsive shock and cognitive outcomes. J ECT. 2009;25(3):157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McClintock SM, Tirmizi O, Chansard M, Husain MM. A systematic review of the neurocognitive effects of magnetic seizure therapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23(5):413-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clinicaltrials.Gov. National Library of Medicine (NLM); 2024.

- 66.Jelovac A, Kolshus E, McLoughlin DM. Relapse following successful electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(12):2467-2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_07067437241301005 for Magnetic Seizure Therapy in Refractory Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: La thérapie par convulsions magnétiques pour la prise en charge des troubles psychiatriques réfractaires : revue systématique et méta-analyse by Jake Prillo, Lorina Zapf, Caroline W. Espinola, Zafiris J. Daskalakis and Daniel M. Blumberger in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry