Abstract

This paper examines the provision of Continuing Healthcare (CHC) within the National Health Service (NHS) in England. It identifies significant care gaps and barriers that mainly affect rural communities; despite CHC’s crucial role in supporting individuals with complex and ongoing healthcare needs, disparities in access and delivery persist, exacerbating health inequalities in rural areas where communities often live in more significant deprivation. Three case studies serve to highlight these challenges to gain a better understanding of the systemic issues at play. The overarching themes underpinning the difficulties in delivering care to rural communities are the insignificant distances between services and the hurdles to obtaining funding. Rural regions often have higher costs due to insufficient local resources and inadequate staffing. These case studies illustrate that rural communities have reduced service availability and logistical challenges, which can lead to delayed or inadequate care.

Keywords: CHC, care-gaps, rurality, inequality, social-care

What do we already know about this topic?

CHC funding is complex, and most patients do not meet the criteria. Still, even when funding is agreed upon, patients in rural communities are at risk of not receiving the care they require due to a lack of available services.

How does your research contribute to this field?

By examining real-world examples of care gaps arising in rural communities, we can analyze areas of potential improvement in the provision of CHC.

What are your research implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

It is suggested that policy and practice changes are required to care for rural patients in need of continuing healthcare support who are currently marginalized due to their location.

Introduction

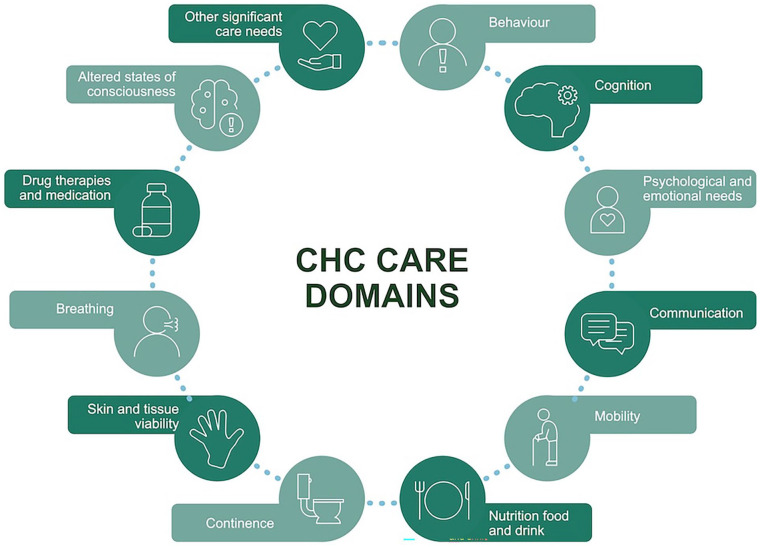

Arising in the early 1990s, CHC is NHS-funded health and social care provided outside of hospitals in England for individuals over 18 years with “high levels of need” that have arisen due to disability, accident, or illness 1 ; Figure 1 highlights CHC domains of care. Whilst the NHS is free at the point of use, social care has always been a means-tested service. It is the responsibility of local authorities, meaning a person’s eligibility for state-funded social care depends wholly on their financial situation.2,3 An individual’s eligibility for CHC, however, is not means tested and is assessed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) made up of 2 or more health and social care professionals who have recently been involved in the person’s assessment, treatment, or case, where possible, against a decision support tool (DST). The eligibility decision should be made within 28 days from assessment, with the integrated care board (ICB) informing persons in writing of their decision. For those with rapidly deteriorating conditions or conditions that may be entering a terminal phase, a fast-track pathway tool allows for a care package to be arranged within 48 h. Those eligible can be funded in either a care home or their own homes.

Figure 1.

CHC domains of care.

In 2021/2022, 104,400 people in England received CHC, around 61% of these being fast-track cases, 4 yet despite these figures, CHC is often called the “NHS’s best-kept secret.” 5 Research conducted for the “Just Group Care Report” found that 77% of those over 45 were unaware of CHC, and 60% of those who had assisted relatives with care funding arrangements had never heard of it. 6 The criteria for CHC eligibility are confusing and complex, and despite the considerable length of the guidelines (187-page National Framework), 7 there is much room for interpretation. Hence, many private companies charge thousands of pounds to argue an individual’s case. Numerous support groups and social media platforms have been set up by individuals and families who feel they have not been relatively assessed and are going through the appeals process. A recent high-profile documentary by Kate Garraway regarding her husband, who had been declined CHC despite his extensive and complex needs, highlighted that even after an appeal, they were waiting for the review almost 3 years later; he has since sadly passed away. 8 Unfortunately, this is not a new or unusual circumstance as the process of attaining CHC is complex and lengthy; in 2018, the BBC reported that more than 3000 people died whilst awaiting CHC eligibility decisions in the prior year. 9

CHC is intended to provide care to the most vulnerable in our society who have complex, intense, or unpredictable physical and mental health and/or learning disability care needs. Despite this, there are many obstacles and delays to being assessed as eligible and then receiving care, which means increased pressure is placed on families and other care services; this particularly disadvantages those in rural communities where healthcare access is more challenging. 10 The Nuffield Trust stated that “it had long been recognized” that rural and remote services faced particular challenges for various reasons. 11 Barriers to the delivery of CHC in rural areas include workforce challenges, recruitment and retention difficulties, and overall higher staff costs, including more considerable distances of coverage leading to higher travel costs and unproductive time spent by staff having to travel. Given that many CHC patients require in-person care due to complex needs, these barriers may be especially challenging. Access to resources such as telecommunications, training and consultancy may also be more expensive in remote areas, which causes health disparities. There may be insufficient adjustment or compensation to cover the unavoidable additional costs of rural health care delivery. In this scenario, health services cannot provide the same level of service for rural patients compared to urban patients.

A report by the House of Lords (2023) found that the average age in rural areas was nearly 6 years higher than that of urban areas, and a quarter of the rural population was over 65. Statistics also indicate that the number of over-65s is increasing much more sharply in rural areas, 37% between 2001 and 2015 versus 17% in urban areas. The report also highlighted that older populations living in rural areas presented a specific challenge to the delivery of health services owing to “greater incidences of chronic illness, disability, and mortality”; therefore, the delivery of CHC is in greater demand. 12 Some parts of the country are more proactive in funding the additional expenses that care agencies incur with rural visits, but this is not universal or standardized.

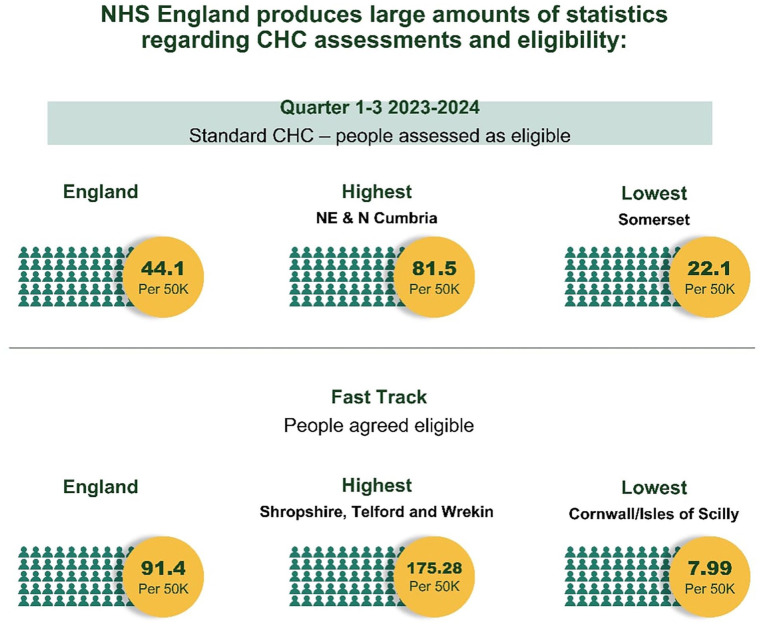

Regardless of these challenges, there are some patients who, despite being assessed as eligible for CHC, are not necessarily receiving care. Most assessments (79% in England in 2023/2024) deny CHC funding. 13 NHS England produces large amounts of statistics regarding CHC assessments and eligibility (Figure 2). However, data regarding how many people are eligible yet are unable to access care or those who experience delays in care do not appear to be recorded. Longstanding issues with the lack of care provision are widely known, and where care cannot be provided, this impacts other services, often leading to otherwise avoidable deterioration in health. Some integrated care boards (ICBs), formally clinical commissioning groups (CCG), have also undertaken scrutiny reviews of CHC provision, with interesting findings; 1 CCG with a £14 million CHC spend in 2017 spent £1 million on administration costs alone. 14 Each DST assessment entails an MDT with NHS and local authority representatives, taking 2-4 h plus report writing and then manager verification, more if the decision is disputed and goes through the lengthy appeals process. This money could otherwise be spent on improving the access to care provision for all our communities.

Figure 2.

People assessed as eligible for Standard CHC by NHS England - Quarters 1-3, 2023-24.

In rural healthcare, delivering CHC involves more than logistics and finances; community social factors significantly influence access to care. Community attitudes, expectations, and beliefs can promote or hinder healthcare delivery. Recognizing this dual impact is crucial for addressing the unique challenges CHC faces in rural areas.

As previously mentioned, CHC is not widely known by the general public or healthcare professionals. This lack of awareness marginalizes potentially eligible individuals from accessing the care they require and have a right to receive. CHC has a unique feature in that, technically, there is no budget; if a patient is deemed eligible, they must receive funding or care. This could be seen as a reason why CHC is not more widely promoted and, at times, relies on social services to highlight that the care they are funding is outside their responsibility to provide. Additionally, individuals are not permitted to “top up” CHC funding in the same way it is allowed in social care. If a person is deemed CHC eligible, then their entire care needs should be met by the NHS, although they are permitted to fund separate private services to complement the NHS care if they so wish.

It could be argued that individuals already in the social services system have a greater chance of being referred for CHC than those who can self-fund their care and, therefore, have little or no contact with social care. Further research into the source of CHC referrals and the previous funding arrangements may shed more light on this.

Case-Studies

The following case studies illustrate the significant care gaps in NHS-funded CHC, focusing on rural communities’ challenges. These real-world examples highlight the disparity in access, quality of care, and the urgent need for targeted interventions to ensure equitable and equal healthcare provision for all.

Case Study 1

AA was an 80-year-old patient on the palliative care pathway who lived rurally with a similar-aged spouse. Following assessment, Fast Track CHC agreed to provide care for 2 h over 3 visits per day. Despite this, local care agencies were required to travel 30 min each way; this time is generally unpaid, so no care agencies were willing to accept the care provision. This resulted in additional pressures on the family, community nurses, and GPs. Available resources such as Marie Curie and hospice care were utilized, but the same issues were observed regarding travel, which impacted the time spent caring. Community nursing teams are not commissioned to provide personal care, but they tend to assist when faced with a patient requiring assistance despite not having capacity. This patient ultimately developed pressure damage from the limited personal care interventions that were available to them and was admitted to the hospital via ambulance as there was no hospice capacity.

In this case, social and economic pressures within the local workforce impacted care provision. Care agencies were reluctant to accept patients in remote locations due to the unpaid travel time required, highlighting an economic reality shaped by the local community’s needs and expectations. These social dynamics effectively limit the availability of care providers, leaving families with fewer options and increased burdens.

Case Study 2

A 45-year-old patient with thoracic spinal cord injury, which had resulted in paralysis, had lived with their parents since their injury 8 years previously and utilized assistive technology to remain as independent as possible. Their health needs were complex, intense, and unpredictable, including mobility, skin care, continence, psychological, medication management, and risk of autonomic dysreflexia. The patient’s parents had provided all assistance with care needs over the past 8 years; however, due to their failing health, they were forced to organize privately funded carers for 1 h per day. Despite only having access to 1 h of care, they were required to pay for 2 h due to the lengthy travel time taken for carers to access the family. Additionally, they had sparse visits from community nurses for catheter changes and skin care.

Following assessment for CHC, the patient was deemed to have primary health care needs requiring 7 h per day care and access to on-call 24-h assistance when required. The patient had planned to move into an adapted bungalow in the same small rural village close to their family and friends. However, the ICB failed to engage the services of a care agency due to the travel time involved, which would not have been paid for. The only other option was for the patient to have a Personal Health Budget (PHB) and source care for themselves. Eventually, the family managed to employ private carers to provide additional support. Still, due to the rural distances, this was not for the 7 h the patient was assessed as requiring. The parents continued to provide additional care, which led to a more rapid decline in their health and subsequent access to primary and secondary health services.

This case illustrates the necessity for compromises in healthcare decisions and emphasizes the influence of social expectations and cultural norms. While it can be argued that the patient’s family was hesitant to manage a Personal Health Budget (PHB), 15 possibly due to a preference for caregivers, their trust within the community and a desire for family involvement in care management, it’s essential to consider that their options were limited. They faced a choice between receiving no care at all or navigating the complexities of managing a PHB, which could be overwhelming and stressful. Additionally, various social factors may contribute to resistance against external care solutions, affecting the patient’s ability to obtain the necessary level of care. Ultimately, this situation highlights how patients and their families may have to compromise on the care that has been deemed essential to receive any support at all.

Case Study 3

An 82-year-old patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Alzheimer’s was living with their son and his family in an isolated farm setting. The patient had severe cognitive impairment, was incontinent and had challenging behaviors at times. The community nurses periodically supported the patient with skin tears and continence assessments but became concerned due to the increasing frequency of minor injuries. The patient would spend much of their day pottering about the farm, “helping” the family with work, and while their family tried to keep them safely occupied and in sight, they frequently wandered. Following the assessment, it was agreed that the patient fulfilled the CHC funding criteria due to the intensity and complexity of their needs. The ICB agreed to fund 4 h daily over 2-3 visits.

Unfortunately, the ICB could not source a care agency due to the location of the patient’s home. A PHB was offered, but the family felt they would have the same difficulties trying to source care from the same list of providers the ICB had access to. Eventually, it was reluctantly agreed that the patient should move to an EMI nursing care home for their safety; the ICB fully funded this. This decision upset the family as the care home was far from their home, and they could not visit often. The change of environment ultimately was detrimental to the patient, who became increasingly agitated and distressed, and his condition further deteriorated.

While rooted in the necessity for safety, the family’s choice to move their loved one to an EMI nursing care home was also deeply influenced by the social dynamics at play. The stigma associated with institutional care and the traditional expectation for families to provide care can weigh heavily, especially in rural communities. These societal pressures emphasize the emotional and social challenges that families navigate, often complicating their care decisions and the well-being of their loved ones.

In this heartbreaking situation, there seem to be no clear winners. The family wanted their loved one to stay home, surrounded by familiar faces and the warmth of family interactions, which could have made a significant difference in their comfort. The individual, too, benefitted from the familiar environment of their home. Additionally, it’s worth noting that the Integrated Care Board would incur significantly higher costs by placing the individual in an EMI nursing home than supporting care at home.

Unfortunately, this scenario reflects a common pitfall: the difficulty in placing the patient at the heart of the decision-making process. Suppose the ICB had provided more support for the family in hiring private carers through a Personal Health Budget. In that case, it’s possible that the individual could have remained at home, creating a win-win situation that would not only enhance the quality of life for the patient but also alleviate some financial pressures on the ICB.

Comparative Analysis With Other High-Income Countries

Comparing CHC provisions in the United Kingdom, excluding Scotland due to its distinct system established in 2015, to those of other nations presents significant challenges. This complexity arises from the community’s varied care structures for patients with high medical needs. Different countries employ diverse systems to fund and support individuals, with the objective of delivering both social and healthcare services. The methodologies for assessment and funding differ considerably, suggesting that further research into the approaches adopted by other countries may yield valuable insights into the future of CHC.

Nonetheless, the experiences of other high-income countries may provide helpful perspectives on enhancing in-person care in rural areas. For instance, Canada has implemented mobile health units that deliver in-person health services across rural communities, effectively addressing gaps in local healthcare availability. 16 Similarly, Norway has established community-based care hubs that bring essential services closer to the homes of rural patients, thereby alleviating travel burdens for healthcare personnel. 17 Australia has adopted financial incentives and retention programs to support rural healthcare providers, which have proven effective in mitigating workforce shortages. 18

Adapting similar models within NHS may address several workforce and economic challenges, ensuring that patients in rural areas who require CHC receive timely and effective in-person care.

Potential Role of Technology in Rural CHC

CHC services encompass a broad spectrum of care, addressing the needs of individuals with severe behavioral challenges and those requiring intricate medical interventions. The diverse range of patients who qualify for such services renders the assessment process and eligibility criteria rather complex. Additionally, when considering the challenges associated with delivering care in rural areas, where resources may be limited or unavailable, it becomes apparent that patients and their caregivers often face significant obstacles in obtaining the requisite care.

In specific scenarios, technology and innovative methodologies can positively influence individuals’ ability to sustain independence. For instance, individuals with severe mobility impairments may utilize assistive technologies to perform tasks such as opening doors, activating electronic devices, and fostering social interactions. While technology will invariably play a critical role in caring for our most vulnerable populations, it should not be perceived as a substitute for comprehensive in-person care.

Face-to-face caregiving is crucial for most CHC patients with complex needs, but technology can play a significant role in early intervention. Tools like remote monitoring for chronic illnesses, digital platforms for preventive care, and teleconsultations can provide proactive support before issues escalate, potentially reducing the need for extensive in-person CHC services. While technology cannot replace hands-on care, it can aid in the early identification and management of health issues, easing pressure on CHC resources and improving healthcare access in rural areas.

Discussion

By definition, individuals eligible for CHC are those with complex needs who require support to maintain their health. As previously noted, a few hours of daily care may suffice to sustain their health and overall well-being. In the absence of these essential services, circumstances can deteriorate, necessitating the involvement of additional services. Initially, community primary care providers, including general practitioners and community nurses, are often responsible for delivering this care. However, the situation can rapidly escalate to require the intervention of ambulances, Accident and Emergency services, and other secondary care providers, already facing significant pressures.

At the core of the issue lies the misallocation of adequate resources, which are not where they are most needed. Private care agencies are not obligated to accept clients; consequently, when all agencies decline, it raises the question of what course of action the Integrated Care Board (ICB) should pursue. Potential improvements could be realized by adopting a team-based approach or having the National Health Service (NHS) employ its own community care teams. The focus in healthcare should remain squarely on patients, minimizing the time and resources expended on disputes between local authorities and the NHS regarding budget responsibilities for essential care. Furthermore, reducing the time spent persuading private care agencies to accept contracts is imperative.

To adequately address the needs of rural communities, efforts should be made to encourage companies to establish more rural-based hubs. Although this strategy may not be universally feasible, embracing, and utilizing technology in patient care could enhance service provision. Nevertheless, technology should not be exploited as a substitute for essential human care.

Social factors, including community norms and family expectations, may affect healthcare access in rural areas. Some rural communities may prefer familial care, which may hinder the deployment of CHC to patients who may rely on family support instead. Service providers may also resist serving remote patients due to economic pressures and community attitudes that discourage travel for unpaid work. Additionally, there may be mistrust of outside care agencies, and patients may try to rely solely on services known to them, such as their family doctor. Addressing these social factors in policy solutions that resonate with rural populations’ cultural and social needs is essential to improving appropriate CHC-funded healthcare access.

Conclusion

Individuals with complex needs may require supplementary support that local authorities are neither equipped to provide nor legally obligated to supply in England. The proportion of patients deemed eligible for CHC resides in care homes, where care services become readily accessible once approved. However, many individuals living independently are not receiving the necessary support.

Enhancements to care provision must be implemented, particularly in rural regions where access to services can pose significant challenges. Engaging in constructive dialogue with stakeholders, including policymakers, is essential to ensure a fair allocation of funds dedicated to adequately addressing the needs of rural populations. Furthermore, it is crucial to avoid placing undue burdens on rural healthcare providers, who may be required to compensate for an ineffective system that inadequately recognizes the specific demographics of their client base.

The complexities and costs associated with CHC are undeniably significant. However, the NHS’s inability to provide adequate local support for rural communities may increase expenses, including care home fees and prolonged inpatient hospital stays. While it may be argued that the NHS cannot sustain CHC for rural populations, the more critical inquiry should focus on whether the NHS can afford not to maintain such services. Whilst not directly comparable, it may be possible to learn lessons from established care delivery models in other high-income nations; these strategies present possible pathways toward a more equitable and economically sustainable CHC framework.

Acknowledgments

The Authors would like to thank the practice staff at Marsh Medical Practice for their ongoing contribution to the provision of care for its patients.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Statement: Our institution sought ethics approval from our local ethics committee reference MMP-LE020924-LH. This study was conducted as a retrospective analysis of previously collected data. The review examined data from the electronic record system, originally gathered for routine clinical work. The data were used solely for this retrospective review. Authors directly involved in the data analysis, are trained in ethical research practices and comply with the guidelines and principles of ethical reporting. All findings are reported accurately and honestly, without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation.

Informed Consent/Patient Consent: Written informed consent has been obtained for the 3 case studies presented in this paper. All data presented in this article were anonymized and obtained from medical records and healthcare professionals involved in the patients’ care. No personal or identifying details of the patients are included in this report. The cases described herein are based solely on clinical information relayed by the treating physicians and other healthcare team members, ensuring patient confidentiality while maintaining the integrity of the medical observations and outcomes reported.

Trial Registration Number/Date: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: Carl Deaney  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2709-7960

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2709-7960

Data Availability Statement: The data that support the findings of this study are derived from clinical case notes and healthcare professional observations. Due to the nature of this research, supporting data is not available.

References

- 1. Oliver D. NHS continuing care is a mess. BMJ. 2016;354:i4214. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayhew L. Means testing adult social care in England. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract. 2017;42(3):500-529. doi: 10.1057/s41288-016-0041-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Searle C. Back to Basics: NHS Continuing Healthcare Eligibility. The Law Society. 2022. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://communities.lawsociety.org.uk/may-2022/back-to-basics-nhs-continuing-healthcare-eligibility/6002314.article

- 4. Powell T, Harker R. NHS Continuing Healthcare in England; 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn06128/

- 5. Hackett M, Cook S, Petford S, et al. Best Kept Secret: The Value of Clinical Homecare to the NHS, Patients and Society. 2011. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://www.healthnethomecare.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Best-Kept-Secret-Report-Final-Version-March-2024-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Public awareness of “labyrinthine” NHS Continuing Healthcare still low – even though it can pay people’s care costs in full. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://www.justgroupplc.co.uk/~/media/Files/J/Just-Retirement-Corp/news-doc/2023/awareness-of-labyrinthine-nhs-chc-low–but-it-can-pay-care-costs-in-full.pdf

- 7. Department of Health and Social Care. July 2022. National Framework for NHS Continuing Healthcare and NHS-funded Nursing Care. 2022. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/64b0f7cdc033c100108062f9/National-Framework-for-NHS-Continuing-Healthcare-and-NHS-funded-Nursing-Care_July-2022-revised_corrected-July-2023.pdf

- 8. Lee D. Make sure you don’t miss out on NHS-funded care like Kate Garraway’s husband. The Telegraph. 2024. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/money/consumer-affairs/dont-miss-nhs-funded-care-kate-garraway-husband/

- 9. Unia E, Rhodes D. Thousands died waiting for NHS funding decision August 24, 2018. BBC. 2018. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-45116453

- 10. Maclaren AS, Locock L, Skea Z, Skåtun D, Wilson P. Rurality, healthcare and crises: Investigating experiences, differences, and changes to medical care for people living in rural areas. Health Place. 2024;87:103217. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2024.103217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palmer B, Rolewicz L. Rural, remote and at risk: Why rural health services face a steep climb to recovery from Covid-19. Nuffield Trust. 2020. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/covid-19-rural-health-services-final.pdf

- 12. Coleman C. Health care in rural areas. 2023. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/health-care-in-rural-areas/

- 13. NHS England. 2023. Accessed May 11, 2024. www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/nhs-chc-fnc/

- 14. Adult Care and Healthcare Overview and Scrutiny Committee. Continuing Healthcare Scrutiny Review undertaken by The adult care and health overview & scrutiny committee. 2018. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://democracy.wirral.gov.uk/documents/s50053206/Enc.%201%20for%20Continuing%20HealthCare%20CHC%20Scrutiny%20Review%2027062018%20Adult%20Care%20and%20Health%20Overview%20an.pdf

- 15. NHS England. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/personal-health-budget-phb-quality-framework/

- 16. Health Canada. Health Services in Rural Canada: Access, Innovative Rural Model Services, and Health Human Resources. Government of Canada, 2021. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/health-services-rural-canada.html [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norwegian Ministry of Health. The Norwegian Healthcare System and Health Outcomes in Rural Regions: Strategies and Reforms. Norwegian Ministry of Health, 2020. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.fhi.no/en/ https://www.fhi.no/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Australian Government Department of Health. Incentives for Rural Health Practitioners and the Development of Regional Health Hubs. Department of Health, 2022. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/ [Google Scholar]