SUMMARY

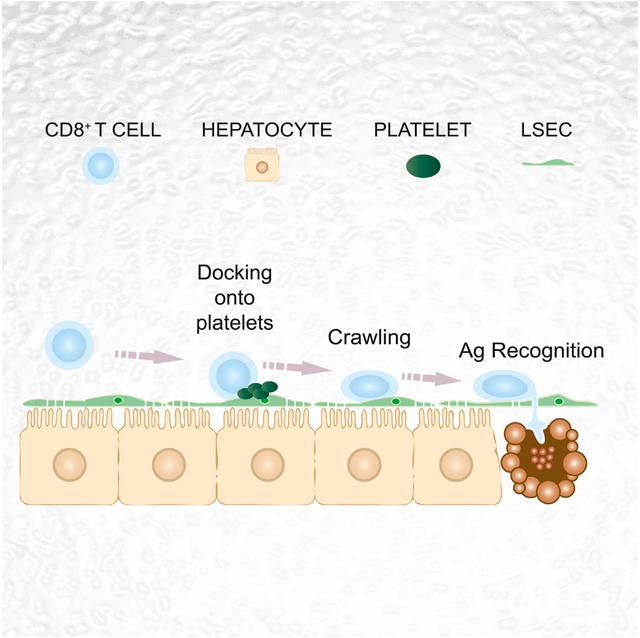

Effector CD8+ T cells (CD8 TE) play a key role during hepatotropic viral infections. Here, we used advanced imaging in mouse models of hepatitis B virus (HBV) pathogenesis to understand the mechanisms whereby these cells home to the liver, recognize antigens, and deploy effector functions. We show that circulating CD8 TE arrest within liver sinusoids by docking onto platelets previously adhered to sinusoidal hyaluronan via CD44. After the initial arrest, CD8 TE actively crawl along liver sinusoids and probe sub-sinusoidal hepatocytes for the presence of antigens by extending cytoplasmic protrusions through endothelial fenestrae. Hepatocellular antigen recognition triggers effector functions in a diapedesis-independent manner and is inhibited by the processes of sinusoidal defenestration and capillarization that characterize liver fibrosis. These findings reveal the dynamic behavior whereby CD8 TE control hepatotropic pathogens and suggest how liver fibrosis might reduce CD8 TE immune surveillance toward infected or transformed hepatocytes.

In Brief

Circulating effector cytotoxic T cells recognize antigen and kill virus-infected hepatocytes without need to migrate into the tissue. Rather, they arrest within liver sinusoids, docking onto platelets, from where they probe hepatocytes for the presence of antigens, a process that is inhibited during liver fibrosis.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The capacity of CD8+ T cells to protect against intracellular pathogens is mediated by antigen (Ag)-experienced effector cells that migrate to infected organs, recognize pathogen-derived Ags, and perform effector functions. Priming of adaptive immune responses during infection with intracellular bacteria or viruses results in extensive reprogramming of T cell trafficking so that effector cells can deal with pathogens that are located in peripheral compartments (Masopust et al., 2001). Understanding of the dynamic events leading to generation and expansion of effector CD8+ T cells (CD8 TE) within lymphoid organs has rapidly improved in recent years, particularly with the use of intravital microscopy (IVM) (Germain et al., 2012). By contrast, less is known on the spatiotemporal aspects that govern CD8 TE migration and function at peripheral infection sites. As a general rule, CD8 TE are thought to recognize pathogen-infected parenchymal cells and perform effector functions in the brain, skin, or gut following extravasation from post-capillary venules mediated by different combinations of inflammation-regulated selectins, integrins, and chemokines (Mueller, 2013).

The liver is a vital organ in which pathogenesis and outcome of infection by clinically relevant noncytopathic viruses, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), is determined by CD8 TE (Guidotti and Chisari, 2006). Several observations suggest that the liver may be an exception to the classic multi-step leukocyte migration paradigm involving rolling, adhesion, and extravasation from postcapillary venules. First, leukocyte adhesion is not restricted to the endothelium of post-capillary venules and occurs also in sinusoids (Lee and Kubes, 2008). Second, leukocyte adhesion to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) often occurs independent of any notable rolling (Lee and Kubes, 2008). Furthermore, in contrast to vascular beds in most organs—where a continuous endothelial cell layer and a basal membrane physically separate parenchymal cells from circulating leukocytes—LSEC lack tight junctions as well as a basal membrane and contain numerous fenestrae of up to 200 nm in diameter (Jacobs et al., 2010). Thus, the fenestrated endothelial barrier of sinusoids provides the opportunity for direct interaction of circulating cells with underlying hepatocytes. For all these reasons, the pathways directing the spatiotemporal regulation of CD8 TE migration and function in the liver may differ from those in other vascular districts.

Here, we have used advanced imaging methodologies in mouse models of HBV pathogenesis to show that hepatic CD8 TE homing is indeed independent of selectins, β2- and α4-integrins, PECAM-1, VAP-1, Gαi-coupled chemokine receptors, or Ag recognition, all previously thought to be variably relevant for leukocyte trafficking in other organs (von Andrian and Mackay, 2000; Mueller, 2013). Rather, circulating CD8 TE initially arrest within liver sinusoids by docking onto platelets in turn adherent to sinusoidal hyaluronan via CD44. After the initial platelet-dependent arrest, CD8 TE actively crawl along liver sinusoids and extend cellular protrusions through endothelial fenestrae to probe underlying hepatocytes for the presence of Ag. Hepatocellular Ag recognition leading to cytokine production and hepatocyte killing occurs in a diapedesis-independent manner, i.e., before CD8 TE extravasation into the parenchyma, and it is inhibited by experimental sinusoidal defenestration and capillarization, both of which are characteristic of liver fibrosis.

RESULTS

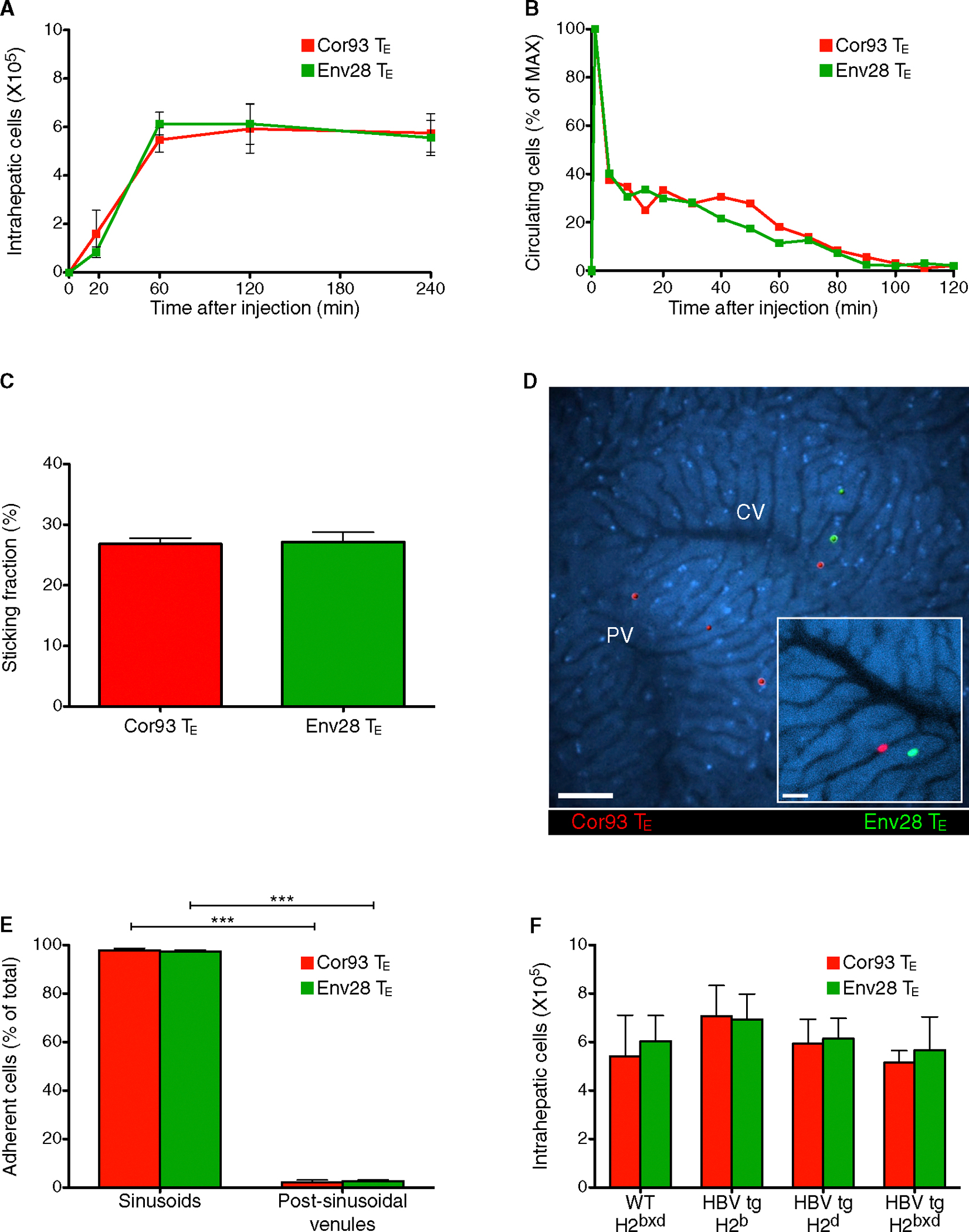

CD8 TE Arrest within Liver Sinusoids Independently of Ag Recognition

To study how CD8 TE traffic within the liver and recognize Ag, we made use of two transgenic mouse strains whose CD8+ T cells express H2b- or H2d-restricted T cell receptors (TCRs) specific for the HBV nucleocapsid (Cor) or envelope (Env) proteins, respectively (Isogawa et al., 2013). Naive CD8+ T cells from these TCR transgenic mice (referred to as Cor93 and Env28 CD8+ T cells, respectively) could be differentiated in vitro into bona fide CD8 TE (data not shown) that, when transferred into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (Guidotti et al., 1995), caused liver disease and inhibited viral replication (data not shown) as much as previously reported polyclonal memory HBV-specific CD8+ T cells (Iannacone et al., 2005). Further analyses in HBV replication-competent transgenic mice revealed that (1) passively transferred Cor93 and Env28 CD8 TE accumulate at peak levels in the liver (see quantification of flow cytometric data in Figure 1A) and no longer circulate throughout the hepatic vasculature by 2 hr of intravenous injection (see quantification of epifluorescence IVM data in Figure 1B), and (2) virtually all CD8 TE that arrested within the 2 hr time frame (~30% of visualized CD8 TE, Figure 1C) adhered to hepatic sinusoids and not to post-sinusoidal venules (Figures 1D and 1E; Movie S1). The transfer of HBV-specific CD8 TE into wild-type (WT) mice, previously injected with a reporter adenovirus (Ad-HBV-GFP) rendering HBV-replicating hepatocytes fluorescent (Sprinzl et al., 2001), revealed that CD8 TE adhere to liver sinusoids regardless of the location of HBV Ag-producing hepatocytes (Movie S1). Consistent with these results, the overall accumulation of CD8 TE in the liver was independent of Ag recognition, as virtually identical numbers of co-transferred Cor93 and Env28 CD8 TE were isolated by 2 hr of injection from the same liver of transgenic and nontransgenic MHC-matched and MHC-mismatched recipients (Figure 1F; Movie S1).

Figure 1. CD8 TE Arrest within Liver Sinusoids Independently of Ag Recognition.

Cor93 (107) CD8 TE (red) and Env28 (107) CD8 TE (green) were intravenously injected into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) or into the indicated mouse strains.

(A) Absolute number of hepatic Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE recovered at the indicated time points after injection. n = 8; results are representative of three independent experiments.

(B) Quantification of the number of circulating Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE detected at the indicated time points within the field of a view (see Experimental Procedures). Results are representative of at least five experiments.

(C) Quantification of the sticking fractions for Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE. n = 5.

(D) Representative images of Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE within the liver vasculature. Images are representative of at least ten experiments. Scale bars represent 50 μm and 20 μm (inset).

(E) Quantification of the localization (sinusoids versus post-sinusoidal venules) of adherent Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE. Cells were defined as adherent when they arrested for >30 s. n = 5.

(F) Absolute number of hepatic Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE recovered 2 hr after injection from the livers of WT or HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2b, H2d or H2bxd). n = 8; results are representative of two independent experiments.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

See also Movie S1.

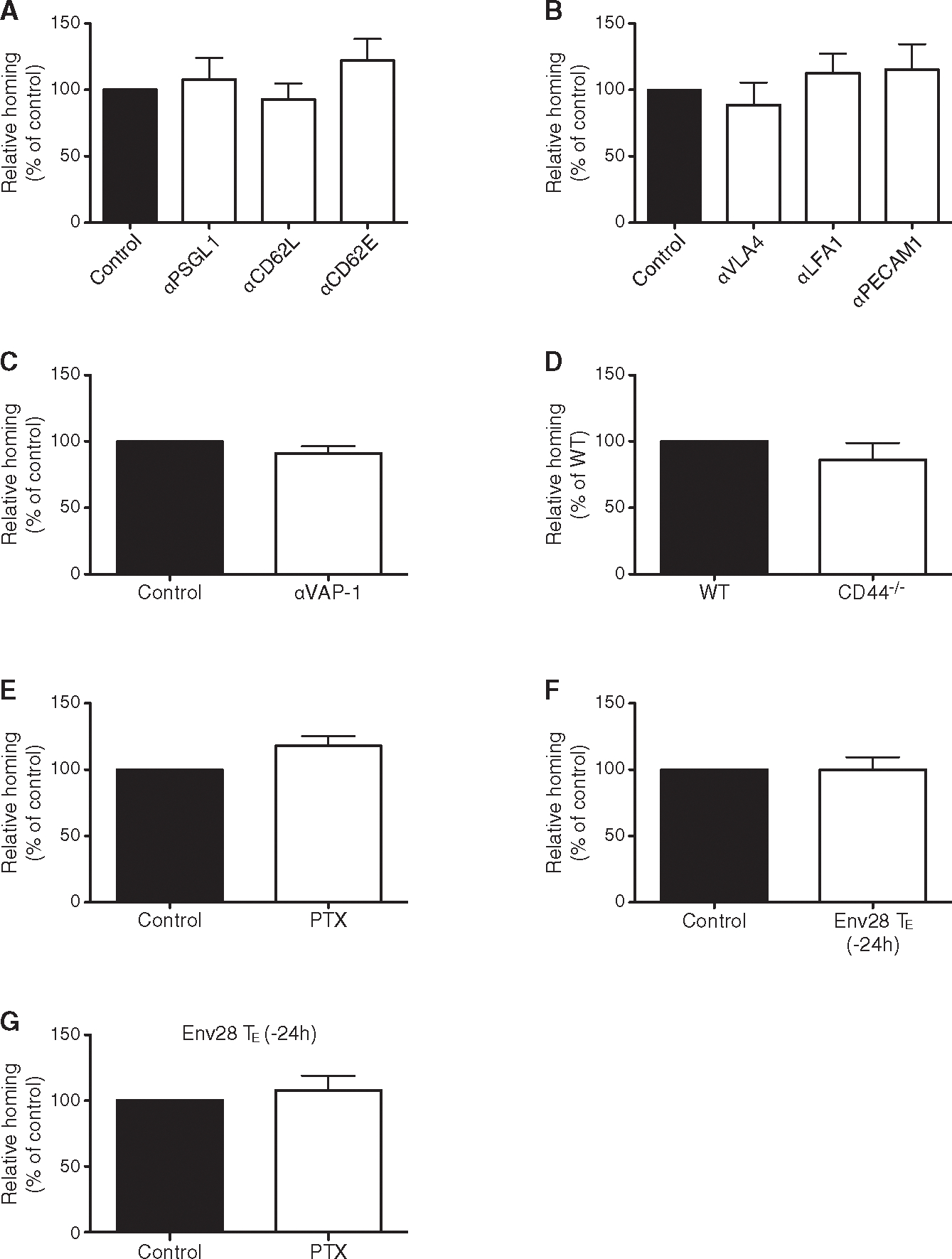

Adhesion Molecules that Govern Leukocyte Trafficking in Other Organs Are Not Required for CD8 TE Accumulation in the Liver

Next, we investigated whether the hepatic CD8 TE accumulation observed within 2 hr of transfer involves the same adhesion molecules known to govern leukocyte trafficking in vascular locations of other organs (von Andrian and Mackay, 2000). Blocking PSGL-1, CD62L, CD62E, VLA-4, LFA-1, PECAM-1, and VAP-1 expressed by CD8+ T cells or LSEC (data not shown) had no impact on hepatic CD8 TE accumulation (Figures 2A–2C) and neither did CD8 TE expression of CD44 (Figure 2D), which has been implicated in hepatic neutrophil recruitment (McDonald et al., 2008). Pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment of CD8 TE, which inhibited chemokine-mediated in vitro migration (data not shown), also did not alter the in vivo hepatic homing capacity of these cells (Figure 2E). Of note, the expression of selectins, integrin ligands, and chemokines is relatively low in the liver of HBV replication-competent transgenic mice prior to CD8 TE transfer (Figures S1A and S1B), consistent with the uninflamed environment seen in experimentally infected chimpanzees prior to HBV-specific CD8+ T cell arrival (Wieland and Chisari, 2005). Increasing the hepatic expression of selectins, integrin ligands, and chemokines via Env28 CD8 TE injection (Figures S1A and S1B) did not affect the liver homing potential of subsequently injected Cor93 CD8 TE either PTX-treated or not (Figures 2F and 2G). To ascertain that the results shown in Figure 2 were not limited to in vitro differentiated CD8 TE, we verified that the liver homing potential of in vivo generated CD8 TE isolated from the spleen of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-infected mice and injected into recipient mice was not affected by blocking the above-mentioned adhesion molecules, even when multiple ligand-receptor pairs where blocked at one time (Figures S1C–S1G). Thus, hepatic accumulation of in vitro or in vivo differentiated CD8 TE is independent of PSGL-1, CD62L, CD62E, VLA-4, LFA-1, PECAM-1, VAP-1, their CD44 expression and Gαi-coupled receptor signaling capability, and the degree of liver inflammation.

Figure 2. Adhesion Molecules that Govern Leukocyte Trafficking in Other Organs Are Not Required for CD8 TE Accumulation in the Liver.

(A) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were previously treated with anti-PSGL1, anti-CD62L or anti-CD62E Abs relative to control (control = 100%). n = 5; results are representative of two independent experiments. Similar results were obtained with Env28 CD8 TE (data not shown).

(B) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were previously treated with anti-VLA-4, anti-LFA-1 or anti-PECAM-1 Abs relative to control (control = 100%). n = 8; results are representative of two independent experiments. Similar results were obtained with Env28 CD8 TE (data not shown).(C) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated WT CD44−/− within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were previously treated with anti-VAP-1 Abs relative to control (control = 100%). n = 5; results are representative of two independent experiments. Similar results were obtained with Env28 CD8 TE (data not shown).

(D) Percentage of CD44−/− Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) relative to WT Cor93 CD8 TE (WT = 100%). n = 10; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(E) Percentage of PTX-treated Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) relative to control Cor93 CD8 TE (control = 100%). n = 5; results are representative of two independent experiments. Similar results were obtained with Env28 CD8 TE (data not shown).

(F) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were injected 24 hr earlier with 5 × 106 Env28 CD8 TE relative to control (control = 100%). n = 5; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(G) Percentage of PTX-treated Cor93 CD8 TE (relative to untreated Cor93 CD8 TE controls) that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were treated 24 hr earlier with Env28 CD8 TE. n = 5; results are representative of two independent experiments.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

See also Figure S1.

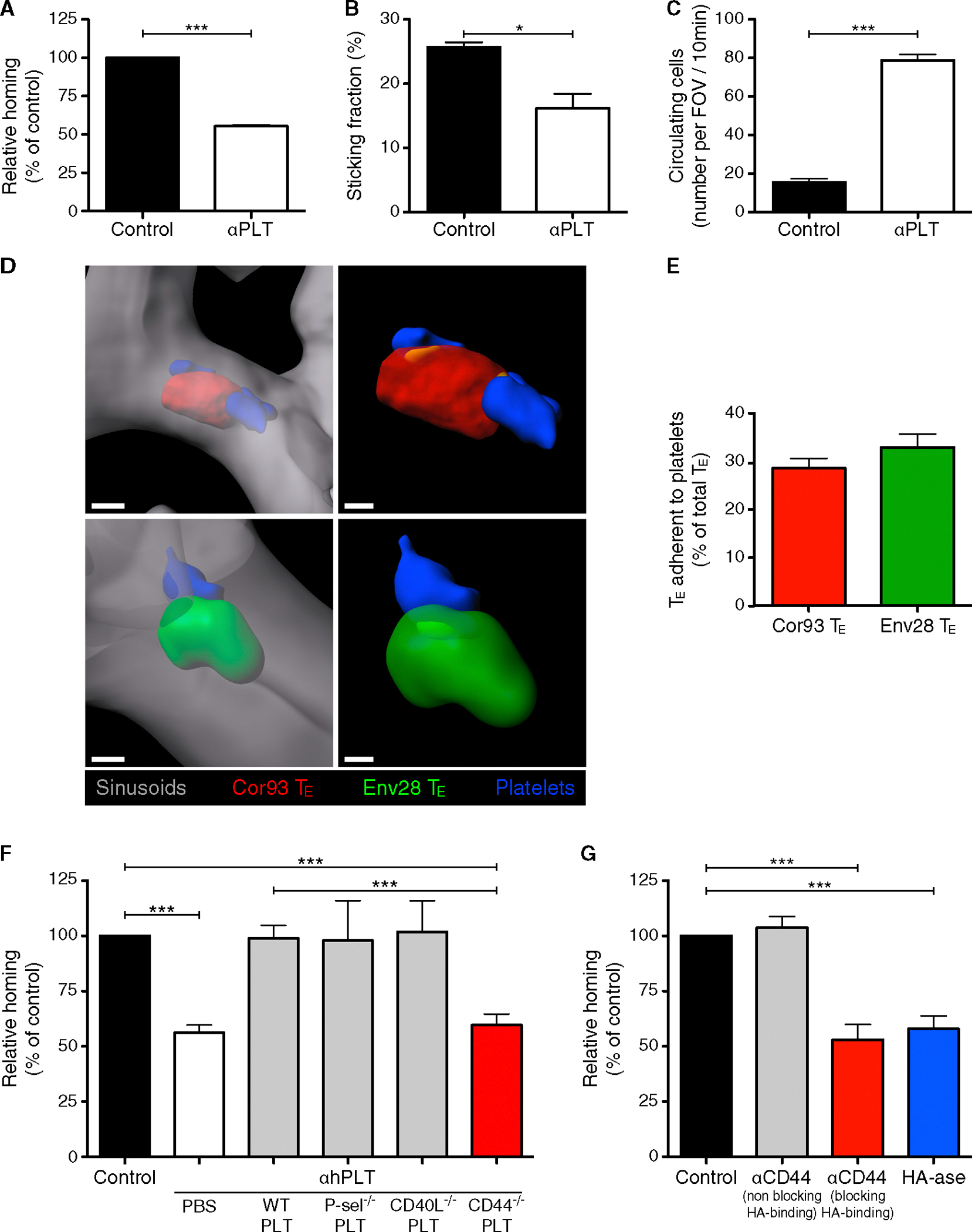

Hepatic CD8 TE Accumulation Requires Platelet Adherence to Sinusoidal Hyaluronan via CD44

We previously showed that platelets facilitate the hepatic accumulation of CD8 TE observed in HBV replication-competent mice at 1–2 days post transfer (Iannacone et al., 2005). However, it remained to be determined whether a platelet-specific pathway could influence the early adhesion of CD8 TE to liver sinusoids. To address this question, we crossed two transgenic mouse strains, one HBV replication-competent and the other with platelets in which the human glycoprotein (GP) Ibα subunit replaced the mouse homolog in the GPIb-IX-V complex (mGPI-bαnull;hGPIbαTg mice) (Ware et al., 2000). The resulting HBV replication-competent mGP-Ibαnull;hGPIbαTg mice can be depleted of endogenous platelets by specific anti-hGPIbα monoclonal antibodies and subsequently reconstituted with mouse platelets lacking reactivity with the depleting antibodies (Iannacone et al., 2008). Platelet depletion per se reduced the hepatic accumulation of CD8 TE by ~50% by 2 hr after transfer (Figure 3A), and this reduction was associated with diminished CD8 TE adhesion to LSEC (Figure 3B; Movie S2) and higher number of CD8 TE circulating throughout the liver microvasculature (Figure 3C; Movie S2). Notably, platelets frequently adhered to LSEC prior to CD8 TE transfer, forming small and transient aggregates of up to 10–15 platelets (Movie S3). Although these aggregates covered a minute fraction of the LSEC surface area (<3%, data not shown), circulating CD8 TE docked preferentially to these sites (Movie S3), so that up to 30% of intrasinusoidal CD8 TE were found attached to platelets at the 2 hr time point by static confocal immunofluorescence analysis (Figures 3D and 3E). Dynamic epifluorescence IVM analysis of platelet-CD8 TE interaction revealed that 30 out of 48 arrested CD8 TE (>60%) docked onto platelets that were already adherent to liver sinusoids (data not shown). Using reconstitution experiments and genetic approaches to identify molecules that might mediate the capacity of platelets to support early hepatic CD8 TE accumulation, we found that platelet-derived CD44 (but not platelet-derived P-selectin, CD40L, or serotonin) facilitated CD8 TE homing to the liver (Figures 3F and S2A). Of note, CD44—expressed by CD8 TE (data not shown) and platelets (Figure S2B)—has the capacity to bind to hyaluronan on liver sinusoids (McDonald et al., 2008). Accordingly, platelet adhesion to liver sinusoids occurred less efficiently in CD44−/−mice than wild-type (WT) controls (Figure S2C; note that CD44−/−mice have normal blood platelet counts and normal in vitro platelet aggregation capacity, data not shown); moreover, in vivo blockade of CD44-hyaluronan interaction or removal of sinusoidal hyaluronan decreased early hepatic CD8 TE accumulation and the attendant liver disease (Figures 3G, S2D, and S2E). Similar results (i.e., reduced hepatic CD8 TE accumulation and reduced liver disease severity) were obtained when CD44-hyaluronan interaction was blocked in a different model of acute viral hepatitis (Iannacone et al., 2005) that relies on endogenous, rather than adoptively transferred, CD8 TE (Figures S2F and S2G). Altogether, these results indicate that CD8 TE adhesion within liver sinusoids and the attendant immunopathology require platelet-expressed CD44 interacting with hyaluronan.

Figure 3. Hepatic CD8 TE Accumulation Requires Platelets that Have Adhered to Sinusoidal Hyaluronan via CD44.

(A) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mice that were previously depleted of platelets (aPLT) relative to control (control = 100%). n = 4; results are representative of three independent experiments.

(B) Quantification of the sticking fraction for Cor93 CD8 TE injected into HBV replication-competent 3 mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mice that were platelet-depleted (aPLT) or left untreated (control). Results are representative of three experiments.

(C) Quantification of the number of Cor93 CD8 TE that were still circulating 2 hr after transfer into HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mice that were platelet-depleted (aPLT) or left untreated (control). Results are representative of three experiments.

(D) Representative confocal micrographs of the liver of a HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mouse (H2b) that was injected 2 hr earlier with Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE. Platelets are shown in blue and sinusoids in gray. To allow visualization of intravascular event and to enhance image clarity, the transparency of the sinusoidal rendering was set to 45% (left panels) and the transparency of the cell rendering to 48% (right panels). Scale bars represent 3 μm (left panels) and 1.5 μm (right panels).

(E) Percentage of Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE that were adherent to endogenous platelets in the liver of a HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mouse (H2b) that was injected 2 hr earlier with these cells. 300 of each cell type from 30 random 40× fields of view were analyzed. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

(F) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mice that were previously depleted of platelets (aPLT) and then injected with PBS, WT platelets, P-selectin−/−platelets, CD40L−/−platelets, or CD44−/−platelets relative to control (control = 100%). n = 6; results are representative of three independent experiments. For the role of platelet-derived serotonin see Figure S2.

(G) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mice that were previously injected with anti-CD44 Abs (clones KM81 or IM7 that either block or not the capacity of CD44 to bind to hyaluronan [HA], respectively) or hyaluronidase (HA-ase) relative to control (control = 100%). n = 7; results are representative of two independent experiments.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

CD8 TE Crawl along Liver Sinusoids until Hepatocellular Ags Are Recognized

We next took advantage of multiphoton IVM to study events that follow the initial platelet-dependent sinusoidal CD8 TE arrest and eventually lead to cognate recognition of hepatocellular Ag. To this end, HBV-specific CD8 TE were infused into mice that had been previously injected with either Ad-HBV-GFP or with adeno-associated viral vectors encoding for GFP and for specific HBV Ags (AAV-HBcAg-GFP or AAV-HBsAg-GFP), using experimental conditions whereby fewer than 5% of hepatocytes are transduced (data not shown). Dynamic imaging revealed that CD8 TE not adjacent to Ag-expressing hepatocytes crawl upstream and downstream in the liver sinusoids at an average speed of ~10 μm/min (note that blood flows in liver sinusoids at 100–400 μm/s) (Sironi et al., 2014). By contrast, CD8 TE migrating in close proximity to Ag-expressing hepatocytes slowed down and eventually arrested (Figures 4A and S3A–S3E; Movie S4). To confirm that cessation of intrasinusoidal CD8 TE crawling is dictated by proximity to HBV Ag-expressing hepatocytes and by capacity to recognize cognate Ag, Cor93 and Env28 CD8 TE were co-transferred into a lineage of HBV transgenic mice that express HBcAg (but not HBsAg) in 100% of hepatocytes (Guidotti et al., 1994). While Env28 CD8 TE crawled within liver sinusoids of HBcAg transgenic mice at an average speed of ~10 μm/min, the vast majority of Cor93 CD8 TE remained immotile, or moved much more slowly and had a confined motility (Figures 4B–4F, S3F, and S3G; Movie S5). Altogether, these observations indicate that CD8 TE exhibit an intrasinusoidal crawling behavior that halts when hepatocellular Ags are recognized.

Figure 4. CD8 TE Crawl along Liver Sinusoids until Hepatocellular Ags Are Recognized.

(A) Intrasinusoidal crawling of CD8 TE, visualized by multiphoton IVM (still image from Movie S4) in the liver of a WT mouse that was injected with Ad-HBV-GFP 2 days prior to Cor93 CD8 TE transfer. The movie was recorded ~1 hr after Cor93 CD8 TE transfer. Red lines denote tracks of individual Cor93 CD8 TE. Sinusoids are in gray. Scale bar represents 50 μm. Similar results were obtained when Env28 CD8 TE were transferred into Ad-HBV-GFP-injected mice or when Cor93 or Env28 CD8 TE were transferred into WT mice previously injected with AAV-HBcAg-GFP or AAV-HBsAg-GFP, respectively (data not shown).

(B) Intrasinusoidal crawling of CD8 TE, visualized by multiphoton IVM (still image from Movie S5) in the liver of a HBcAg transgenic mouse (H2b) that was injected with H2b-restricted Cor93 (red) and H2d-restricted Env28 (green) CD8 TE. Red and green lines denote tracks of individual Cor93 and Env28 CD8 TE, respectively. Sinusoids are in gray and hepatocellular nuclei are in blue. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

(C) Still image (large left panel) and time lapse recording (small right panels) in the liver of a HBcAg transgenic mouse (H2b) that was injected with Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE. Red and green lines denote tracks of individual Cor93 and Env28 CD8 TE, respectively. Sinusoids are in gray. Elapsed time in minutes:seconds. Scale bar represents 15 μm (left) and 10 μm (right).

(D–F) Mean speed (D), displacement (E), and straightness (F) (see Experimental Procedures) of individual Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE in the liver of a HBcAg transgenic mouse (H2b). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001.

Figures S3 and S4 and Movies S4 and S5.

Of note, HBV Ag expression in HBcAg transgenic mice, as in HBV replication-competent mice, is restricted to hepatocytes (Isogawa et al., 2013); in keeping with this, only hepatocytes isolated from these HBV transgenic mouse lineages presented Ag in vitro to HBV-specific CD8 TE, in contrast to LSECs, Kupffer cells and dendritic cells isolated from their livers or liver-draining lymph nodes, which did not (Figure S4 and data not shown). These results are consistent with recent reports showing that HLA class I restricted HBV epitopes are exclusively expressed by human hepatocytes during natural HBV infection (Ji et al., 2012).

CD8 TE Recognize Hepatocellular Ags and Perform Effector Functions in a Diapedesis-Independent Manner

The foregoing results suggest that CD8 TE may recognize hepatocellular Ag while still in the intravascular space. To test this hypothesis, we set up an immunofluorescence staining method allowing the detection of Ag-recognizing (i.e., IFN-γ producing) cells with respect to their localization within the liver. Two hours after the co-transfer of Cor93 and Env28 CD8 TE in H2b-restricted HBV replication-competent or HBcAg transgenic mice, both populations were contained within the hepatic sinusoidal lumen but only MHC-matched Cor93 CD8 TE expressed IFN-γ (Figures 5A, S5A, and S5B; Movie S6; data not shown). IFN-γ expression by intravascular CD8 TE adjacent to hepatocyte expressing cognate Ag was also confirmed in WT mice that were injected with Ad-HBV-GFP prior to Cor93 CD8 TE transfer (Figures S5C and S5D). That CD8 TE performed effector functions without extravasating is further indicated by the detection of apoptotic hepatocytes preferentially juxtaposed to intravascular MHC-matched—rather than MHC-mismatched—CD8 TE (Figure 5B; Movie S6; quantification in Figure S6). Confocal 3D reconstructions of these experiments occasionally revealed the presence of small CD8 TE protrusions appearing to penetrate the sinusoidal wall in order to gain contact with underlying hepatocytes (Figure 5B; Movie S6). Analysis of the hepatic localization of CD8 TE in transgenic and nontransgenic MHC-matched and MHC-mismatched recipients at 2 and 4 hr after CD8 TE transfer revealed that only CD8 TE capable of recognizing Ag eventually extravasate (Figures S7A–S7C). These observations, coupled with the notion that the ratio between intravascular and extravascular CD8 TE performing effector functions (i.e., expressing IFN-γ or triggering hepatocellular apoptosis) decreases over time (Figures S7D and S7E), indicate that extravasation follows rather than precedes Ag recognition. Together, the above results indicate that CD8 TE do not need to extravasate in order to recognize hepatocellular Ags and to perform effector functions.

Figure 5. CD8 TE Recognize Hepatocellular Ags and Perform Effector Functions in a Diapedesis-Independent Manner.

(A) Representative confocal micrographs of the liver of a HBV replication-competent transgenic mouse (H2b) that was injected 2 hr earlier with Cor93 (red) and Env28 (green) CD8 TE. Sinusoids are shown in gray and IFN-γ in yellow. To allow visualization of intravascular events and to enhance image clarity, the transparency of the sinusoidal rendering in the right panel was set to 70% and that of T cells to 60%. Scale bars represent 4 μm. See also Movie S6 and Figure S5. Similar results were obtained in similarly treated HBcAg transgenic mice (data not shown).

(B) Representative confocal micrographs of the liver of a HBV replication-competent transgenic mouse (H2b) that was injected 2 hr earlier with Cor93 CD8 TE (red). Sinusoids are shown in gray and caspase 3 in brown. To allow visualization of intravascular events and to enhance image clarity, the transparency of the sinusoidal rendering in the right panel was set to 50%. Scale bars represent 5 μm. See also Movie S6 and Figure S6. Similar results were obtained in similarly treated HBcAg transgenic mice (data not shown).

(C) Correlative confocal and transmission electron microscopy of the liver of an HBcAg transgenic mouse whose LSEC express membrane-targeted tdTomato (see Experimental Procedures) that was injected 30 min earlier with Cor93 CD8 TE. Left: overlay of the Cor93 CD8 TE and LSEC fluorescence (red and green, respectively) with the electron micrograph of the same section. Right: electron micrograph alone. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

(D) Transmission electron tomograms of five selected serial slices from the area delineated by the red inset in (C). The numbers indicate the z-distance from the middle section. Cor93 CD8 TE and LSEC are indicated by the red and green overlay, respectively. Scale bars represent 500 nm. See Movie S7 for the complete tomographic reconstruction of 289 sections with a 1.95 nm z-step.

See also Figures S5, S6, and S7 and Movies S6 and S7.

CD8 TE Recognize Hepatocellular Ags through Fenestrations in Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells

The above-mentioned results and the unique anatomy of the liver microvasculature suggest that CD8 TE cellular protrusions might reach underlying hepatocytes through anatomical discontinuities in the hepatic sinusoid created by fenestrae that penetrate the endothelial cell lining. To test this hypothesis, we established a correlative technique that combines the specificity of 3D confocal fluorescence microscopy with the resolution of transmission electron tomography; this was carried out on liver sections from HBcAg transgenic mice whose LSEC are fluorescent (see Experimental Procedures). While confirming at higher resolution that CD8 TE protrusions penetrate the sinusoidal wall, we found that these structures correspond to cytoplasmic CD8 TE extensions that protrude through the LSEC fenestrae and contact the hepatocyte membrane over relatively large surface areas (Figures 5C and 5D; Movie S7). Although the fixation procedure of this correlative technique does not permit Ab staining (thus it cannot detect Ag recognition markers), these results are compatible with the formation of an immunological synapse between intravascular CD8 TE and hepatocytes. The notion that CD8 TE extend cytoplasmic protrusions penetrating the sinusoidal barrier of WT mice as well (data not shown) suggests that contacts with sub-sinusoidal hepatocytes might be the mechanism whereby CD8 TE crawling intravascularly probe the liver for the presence of hepatocellular Ag.

To test the biological significance of CD8 TE-mediated Ag recognition through sinusoidal fenestrae, HBV replication-competent transgenic mice were chronically exposed to low doses of arsenite (Straub et al., 2007), a treatment that reduces liver porosity (i.e., number and size of sinusoidal endothelial cell fenestrae) recapitulating the sinusoidal defenestration that characterizes liver fibrosis (Friedman, 2004). Arsenite treatment decreased liver porosity by ~5-fold (Figures 6A–6C) without affecting neither hepatic HBV Ag expression nor the capacity of hepatocytes to present Ag to CD8 TE in vitro (data not shown). This same treatment did not alter the hepatic homing of CD8 TE, which is platelet-dependent, but it reduced their in vivo Ag recognition capacity, as evidenced by the reduction of both IFN-γ expression and sALT elevation (Figures 6D–6J). To rule out off-target effects of arsenite treatment, we infected arsenite-treated mice with LCMV, a virus whose tropism in the liver is mostly restricted to intravascular Kupffer cells (Guidotti et al., 1999) and where, therefore, subsequently transferred LCMV-specific CD8 TE should recognize infected cells independent of contacts through sinusoidal endothelial fenestrae. Indeed, arsenite exposure impacted neither the homing nor the Ag-recognition capacity of LCMV-specific CD8 TE (Figures 6K and 6L).

Figure 6. Reducing Sinusoidal Porosity Limits Hepatocellular Ag Recognition by CD8 TE.

(A and B) Representative scanning electron micrographs from liver sections of control (A) or arsenite-treated (B) HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) mice. Yellow dotted lines denote sinusoidal edges. Scale bars represent 1 μm.

(C) Porosity (the percentage of liver endothelial surface area occupied by fenestrae) was measured in control and arsenite-treated mice. n = 3; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(D) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were previously treated with arsenite relative to control (control = 100%). n = 20; results are representative of two independent experiments. Similar results were obtained with Env28 CD8 TE (data not shown).

(E) Total hepatic RNA from the same mice described in (D) was analyzed for the expression of IFN-γ by qPCR. Results are expressed as fold induction (f.i.) over HBV replication-competent transgenic mice injected with PBS, after normalization to the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

(F) ALT activity measured in the serum of the same mice described in (D).

(G and H) Representative confocal micrographs from the same mice described in (D). Cor93 CD8 TE are shown in red, sinusoids in gray and IFN-γ in yellow. Arrowheads denote IFN-γ+ cells. Scale bars represent 20 μm.

(I) The percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that stained positive for IFN-γ was quantified in liver sections from the same mice described in (D). n = 90.

(J) IFN-γ mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Cor93 CD8 TE was quantified in liver sections from the same mice described in (D). n = 90.

(K) Percentage of GP33 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into LCMV-infected mice that were previously treated with arsenite, relative to control (control = 100%). n = 5; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(L) Total hepatic RNA from the same mice described in (K) was analyzed for the expression of IFN-γ by qPCR. Results are expressed as fold induction (f.i.) over LCMV-infected mice injected with PBS, after normalization to the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Next, we evaluated whether the deposition of extracellular matrix in the space of Disse—a process known as liver capillarization, which creates a physical barrier between sinusoidal fenestrae and hepatocellular membranes and is frequently found in fibrotic livers (Friedman, 2004)—could also limit Ag recognition by intravascular CD8 TE. To this end, we transferred HBV-specific CD8 TE to HBV replication-competent transgenic mice with liver fibrosis as a consequence of chronic exposure to carbon tetrachloride (Figures 7A–7C). This treatment did not alter the capacity of CD8 TE to home to the liver, while significantly impaired CD8 TE ability to recognize Ag on hepatocytes but not on intravascular Kupffer cells (Figures 7D–7H).

Figure 7. Liver Fibrosis Limits Hepatocellular Ag Recognition by CD8 TE.

(A and B) Representative Sirius Red (left) or transmission electron (right) micrographs from liver sections of control (A) or carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-treated (B) HBV replication-competent transgenic mice. Sirius Red staining is shown in red. Scale bars represent 100 μm (Sirius Red) and 1.5 μm (transmission electron micrographs). Red and yellow dotted lines denote LSEC and the hepatocyte body, respectively. SD, space of Disse; H, hepatocyte.

(C) Quantification of Sirius red staining in HBV replication-competent transgenic mice that were treated or not with CCl4. n = 3; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(D) Percentage of Cor93 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into HBV replication-competent transgenic mice (H2bxd) that were previously treated with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) relative to control (control = 100%). n = 15; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(E) Total hepatic RNA from the same mice described in (D) was analyzed for the expression of IFN-γ by qPCR. n = 15; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(F) ALT activity measured in the serum of the same mice described in (D). n = 15; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(G) Percentage of GP33 CD8 TE that accumulated within the liver 2 hr upon transfer into LCMV-infected mice that were previously treated with CCl4 relative to control (control = 100%). n = 7; results are representative of two independent experiments.

(H) Total hepatic RNA from the same mice described in (G) was analyzed for the expression of IFN-γ by qPCR. Results are expressed as fold induction (f.i.) over LCMV-infected mice injected with PBS, after normalization to the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Altogether, these results indicate that CD8 TE recognize hepatocellular Ags through sinusoidal endothelial fenestrations and suggest a mechanism whereby liver fibrosis reduces T cell immune-surveillance toward infected or transformed hepatocytes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we coupled advanced imaging techniques and models of HBV pathogenesis to reveal previously unappreciated determinants that regulate the migration, Ag recognition, and effector function of CD8 TE within the liver. In contrast to most other organs—where CD8 TE arrest is mainly restricted to post-capillary venules and promoted by inflammation (von Andrian and Mackay, 2000)—CD8 TE circulating through the liver initially arrest within sinusoids and they do so independently of selectins, Gαi-coupled chemokine receptors, β2- and α4-integrins, PECAM-1, and VAP-1. Furthermore, sinusoidal arrest and early accumulation of CD8 TE occurs independently of their capacity to recognize hepatocellular Ag.

We previously used similar models of HBV pathogenesis to show that platelets are involved in hepatic CD8 TE accumulation occurring 1–2 days post transfer (Iannacone et al., 2005), but the molecular mechanisms and spatiotemporal dynamics underlying these observations have remained elusive. Herein, we extended these observations by showing that (1) platelets adhere to LSEC even under steady-state conditions, leading to the transient formation of small intrasinusoidal aggregates on LSECs; (2) this process is mediated by platelet-expressed CD44 interacting with LSEC hyaluronan; and (3) intrasinusoidal platelet aggregates function as preferential docking sites for circulating CD8 TE. Other platelet molecules that had been previously implicated in the cross-talk between platelets and adaptive immunity, such as CD40L (Iannacone et al., 2008) or serotonin (Lang et al., 2008) were shown to be dispensable for these processes. Notably, platelets have been shown to form intrasinusoidal aggregates on the surface of bacterially infected Kupffer cells, possibly as a pathogen-trapping mechanism promoting immune-mediated clearance (Wong et al., 2013). In contrast to this study, we saw no evidence for a preferential formation of platelet aggregates on Kupffer cells in our system (data not shown), where Kupffer cells are neither infected with bacteria nor targeted by CD8 TE. These results, together with the notion that Kupffer cell depletion does not affect hepatic CD8 TE accumulation in these mouse models (Sitia et al., 2011), indicate that platelet-Kupffer cell interaction does not play a role in the hepatic homing of CD8 TE targeting hepatocellular Ags.

It is noteworthy that experiments using anti-GP-Ibα Abs to deplete circulating platelets by roughly 50-fold (reducing normal platelet counts from ~106 platelets/ml to 2 × 104 platelets/ml) decreased the early hepatic accumulation of CD8 TE only 2-fold. These results suggest that either the number of circulating platelets vastly exceeds the number required to efficiently arrest CD8 TE in the liver or that a fraction of CD8 TE home to the liver independently of platelets. Although the failure to further reduce hepatic CD8 TE accumulation by treating platelet-depleted animals with CD44 blocking Abs supports the latter hypothesis, future studies are needed to settle this issue definitively.

Although our data have unambiguously identified the molecular interaction by which platelets adhere to LSEC, the mechanism(s) supporting CD8 TE docking onto platelet aggregates remains unexplained. Of note, platelets possess a large array of surface molecules mediating adhesion to endothelial cells, and, among these, only P-selectin has a known ligand (i.e., PSGL-1) expressed also by CD8 TE (Borges et al., 1997). As passive PSGL-1 neutralization or reconstitution with P-selectin-deficient platelets did not alter the capacity of CD8 TE to accumulate intrahepatically, it appears that the interaction between P-selectin on platelets and PSGL-1 on CD8 TE is not operative in our system. Whether other constitutively expressed or activation-induced platelet molecules directly or indirectly (via the formation of molecular bridges with CD8 TE ligands) contribute to the process of CD8 TE docking onto platelet aggregates remains to be determined. An attractive alternative hypothesis, which is currently under investigation, is that intrasinusoidal platelet aggregates alter local flow dynamics in ways that force CD8 TE to slow down and then engage platelets and/or LSEC via non-covalent interactions.

Following the initial interaction with platelets, CD8 TE were shown to crawl along liver sinusoids independently of blood direction and at a speed that was 500- to 1,000-fold slower than sinusoidal flow (Sironi et al., 2014). This multi-directional intrasinusoidal crawling behavior is reminiscent of what has been observed for CD1d-restricted NKT cells patrolling the liver microvasculature (Geissmann et al., 2005). While the molecular mechanisms mediating CD8 TE crawling are unknown, preliminary data show that chemokine cues might not be involved in this process (unpublished data). Whether hepatic CD8 TE crawl along physical structures—as described for naive T cells migrating along the fibroblastic reticular cell network in the T cell area of lymph nodes (Bajénoff et al., 2006) or for effector T cells migrating along the myeloid scaffold delineating hepatic granulomas (Egen et al., 2008)—or whether noradrenergic neurotransmitters from sympathetic nerves can also modulate intrasinusoidal CD8 TE motility—as described for intrasinusoidal hepatic NKT cells (Wong et al., 2011)—remains to be determined.

Importantly, our data show that the intrasinusoidal crawling behavior represents a form of immune surveillance, since it occurs independently of the presence of cognate Ag and it ceases following hepatocellular Ag recognition. Indeed, virus-specific CD8 TE were shown to recognize hepatocellular Ags and to perform pathogenic functions (i.e., they produced IFN-γ and they killed HBV-expressing hepatocytes) while still in the intravascular space. These processes were mediated by the extension of cellular protrusions through sinusoidal endothelial cell fenestrae by CD8 TE, producing contact sites with the hepatocyte membrane that are compatible with the establishment of an immunological synapse (Dustin and Groves, 2012). Of note, this Ag probing activity by intravascular CD8 TE would require the formation and retraction of cellular protrusions, events that might seem at odds with average CD8 TE migration rates of ~10 μm/min. The high variability among CD8 TE velocities (between 1 and up to 30 μm/min, see Figure 4D) is compatible with the hypothesis that slower cells are more active in extending and retracting trans-endothelial protrusions than faster-moving ones. The notion that circulating leukocytes can interact with hepatocytes through endothelial fenestrations has been proposed in previous studies (Ando et al., 1994; Geissmann et al., 2005; Warren et al., 2006). Our results revealed that this process has functional significance, as reducing sinusoidal porosity or creating a physical barrier between sinusoidal fenestrae and hepatocellular membranes inhibited hepatocellular Ag recognition by CD8 TE. These results also suggest a potential mechanism whereby liver fibrosis (a condition promoting both sinusoidal defenestration and capillarization) might reduce CD8 TE immune surveillance toward infected or transformed hepatocytes and, in the latter case, favor the development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Another novel finding from our studies is that CD8 TE extravasation from the liver microcirculation follows, rather than precedes, hepatocellular Ag recognition and effector function. The fate of extravasated CD8 TE remains ill defined. One possibility is that they invade hepatocytes, enter endosomal/lysosomal compartments and are degraded, a process of suicidal emperipolesis that was recently described for naive CD8+ T cells undergoing primary activation in the liver (Benseler et al., 2011). We are attracted by the hypothesis that CD8 TE extravasation into the liver parenchyma (whether through emperipolesis or other yet undefined mechanisms) might actually represent a way to limit Ag recognition and, therefore, to regulate excessive liver damage caused by CD8 TE. This concept is supported by the notion that hepatocellular MHC-I expression is polarized and localized predominantly to the portion of the basolateral membrane facing the sinusoidal lumen (Warren et al., 2006), so that MHC-I-peptide complexes might be less accessible to CD8 TE residing in extravascular spaces.

In summary, the data presented here reveal novel dynamic determinants regulating trafficking and effector function of CD8 TE after hepatocellular Ag recognition. This is particularly relevant for the pathogenesis of viral infections such as those caused by HBV and HCV, noncytopathic pathogens that replicate selectively in the hepatocyte and cause acute or chronic liver disease that are triggered by virus-specific CD8 TE (Guidotti and Chisari, 2006). By extension, it is conceivable that similar mechanisms may also be operative for bacterial and parasitic infections that target hepatocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

Mice were obtained from various sources and maintained in SPF conditions. All experimental animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Committee of the San Raffaele Scientific Institute. For details on mouse lines and BM chimera generation, see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Viruses and Vectors

For details on adenoviral vectors, adeno-associated viruses and LCMV, see the Extended Experimental Procedures. All infectious work was performed in designated BSL-2 or BSL-3 workspaces, in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Generation of Effector CD8+ T Cells and Adoptive Transfer

In vitro generation of CD8+ T cells (CD8 TE) was performed basically as described (Manjunath et al., 2001). A total of 107 cells of each cell type were injected intravenously (i.v.) into recipient animals. In imaging experiments, CD8 TE were labeled with 2.5 μM CMFDA, 2.5 μM CFSE, 7.5 μM CMTPX, 10 μM CMTMR, or 2.5 μM BODIPY 630/650-X (Life Technologies) for 20 min at 37°C in plain RPMI prior to adoptive transfer. For details, see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Blocking Abs and Hyaluronidase Treatment

The following blocking Abs were injected i.v. 2 hr prior to T cell transfer: antiPSGL-1 (clone 4RA10; BioXCell; 200 μg/mouse), anti-CD62L (clone MEL-14; BioXCell; 100 mg/mouse), anti-CD62E (clone 10E9.6; BD PharMingen; 100 μg/mouse), anti-VLA-4 (clone PS/2; BioXCell; 100 μg/mouse), anti-LFA-1 (clone M17/4; BioXCell; 100 mg/mouse and clone GAME46; BD PharMingen; 25 μg/mouse), anti-PECAM-1 (clone MEC13.3; BioLegend; 100 μg/mouse), anti-VAP-1 (80 μg of clone 7–88 + 80 μg of clone 7–106/mouse, both provided by S. Jalkanen), anti-CD44 (clone KM81, blocking CD44 binding to hyaluronan [Zheng et al., 1995]; Cedarlane; 20 μg/mouse), anti-CD44 (clone IM7, not interfering with CD44 binding to hyaluronan [Zheng et al., 1995]; BioXCell; 100 μg/mouse). In indicated experiments mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 20 U/g hyaluronidase type-IV (Sigma-Aldrich), as described (Johnsson et al., 1999).

Env28 CD8 TE-Mediated Induction of Liver Inflammation

In order to increase the hepatic expression of selectins, integrin ligands and chemokines (experiments described in Figures 2F, 2G, and S1), HBV replication-competent transgenic mice were injected i.v. with 5 × 106 Env28 CD8 TE 24 hr prior to the injection of 107 Cor93 CD8 TE.

Treatment with Pertussis Toxin and Chemotaxis Assay

The role of Gαi signaling was assessed by incubating CD8 TE (107 cells/ml) for 2 hr at 37°C with 100 ng/ml pertussis toxin (Merck). For details on chemotaxis assay see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Depletion and Transfusion of Platelets

HBV replication-competent × mGP-Ibαnull;hGP-IbαTg mice were injected i.v. with 80 μg of clone LJ-P3 (a monoclonal Ab that recognizes the platelet-specific human GP-Ibα) at least 3 hr prior to further experimental manipulation, as described (Iannacone et al., 2008). Platelet transfusion was performed as described (Iannacone et al., 2008), with each mouse receiving a single i.v. injection of 6 × 108 platelets.

Treatment with Sodium Arsenite or Carbon Tetrachloride

In indicated experiments, mice were treated with sodium arsenite (250 ppb in drinking water ad libitum) for 10 weeks. In other experiments mice were fed by oral gavage with a solution of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) in peanut oil (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final dose of 0.7 mg/g of body weight. CCl4 was administered twice a week for 12 weeks, after which the treatment was suspended for a washout period of 4 weeks.

Cell Isolation and Flow Cytometry

Single-cell suspensions of livers, spleens, and lymph nodes were generated as described (Iannacone et al., 2005; Tonti et al., 2013). For details on flow cytometric analyses see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Isolation of Primary Hepatocytes, LSEC, Kupffer Cells, Intrahepatic Dendritic Cells, and Dendritic Cells from Liver-Draining Lymph Nodes

Primary hepatocytes, LSEC, Kupffer cells, and dendritic cells were isolated essentially as described (Isogawa et al., 2013). Hepatic lymph node dendritic cells were isolated by positive selection using biotinylated CD11c and streptavidin Magnetic Particles (BD Biosciences). For details see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Imaging Studies

For details on histochemistry, confocal immunofluorescence histology, intravital epifluorescence, and multiphoton microscopy, electron microscopy, and correlative light and electron tomography, see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

DNA, RNA, and Biochemical Analyses

For details on molecular and biochemical analyses, see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Statistical Analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed in Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Means between two groups were compared with two-tailed t test. Means among three or more groups were compared with one-way or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Circulating CD8 TE arrest in liver sinusoids by docking onto platelet aggregates

CD8 TE crawl along liver sinusoids in search of hepatocellular antigen

Cytokine production and hepatocyte killing occur in a diapedesis-independent manner

Liver fibrosis impairs antigen recognition by intravascular CD8 TE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Raso for technical support; R. Serra for secretarial assistance; S. Jalkanen for providing anti-VAP-1 Abs; S. Wieland for providing pCMV-b-gal; M. Bader for providing TPH-1−/−mice; J. Egen for advice on the liver surgical preparation for the inverted microscope setup; C. Tacchetti for advice on correlative microscopy; L. Suarez-Amarán for help with the generation of recombinant adeno-associated viruses; P. Dellabona and R. Pardi for critical reading of the manuscript and the members of the M. Iannacone and L.G.G. laboratories for helpful discussions. We would like to acknowledge the PhD program in Basic and Applied Immunology at San Raffaele University, as D.I. conducted this study as partial fulfillment of his PhD in Molecular Medicine within that program. This work was supported by European Research Council (ERC) grants 250219 (to L.G.G.) and 281648 (to M. Iannacone); NIH RO1 grant AI40696 (to L.G.G.) and HL-42846 (to Z.M.R.); Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) grant 9965 (to M. Iannacone); and a Career Development Award from the Giovanni Armenise-Harvard Foundation (to M. Iannacone).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and seven movies and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.005.

REFERENCES

- Ando K, Guidotti LG, Cerny A, Ishikawa T, and Chisari FV (1994). CTL access to tissue antigen is restricted in vivo. J. Immunol. 153, 482–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajénoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, and Germain RN (2006). Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration, and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity 25, 989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benseler V, Warren A, Vo M, Holz LE, Tay SS, Le Couteur DG, Breen E, Allison AC, van Rooijen N, McGuffog C, et al. (2011). Hepatocyte entry leads to degradation of autoreactive CD8 T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 16735–16740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges E, Tietz W, Steegmaier M, Moll T, Hallmann R, Hamann A, and Vestweber D (1997). P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on T helper 1 but not on T helper 2 cells binds to P-selectin and supports migration into inflamed skin. J. Exp. Med. 185, 573–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin ML, and Groves JT (2012). Receptor signaling clusters in the immune synapse. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 543–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egen JG, Rothfuchs AG, Feng CG, Winter N, Sher A, and Germain RN (2008). Macrophage and T cell dynamics during the development and disintegration of mycobacterial granulomas. Immunity 28, 271–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SL (2004). Mechanisms of disease: Mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis and therapeutic implications. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1, 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Cameron TO, Sidobre S, Manlongat N, Kronenberg M, Briskin MJ, Dustin ML, and Littman DR (2005). Intravascular immune surveillance by CXCR6+ NKT cells patrolling liver sinusoids. PLoS Biol. 3, e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain RN, Robey EA, and Cahalan MD (2012). A decade of imaging cellular motility and interaction dynamics in the immune system. Science 336, 1676–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti LG, and Chisari FV (2006). Immunobiology and pathogenesis of viral hepatitis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 1, 23–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti LG, Martinez V, Loh YT, Rogler CE, and Chisari FV (1994). Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid particles do not cross the hepatocyte nuclear membrane in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 68, 5469–5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti LG, Matzke B, Schaller H, and Chisari FV (1995). High-level hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 69, 6158–6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti LG, Borrow P, Brown A, McClary H, Koch R, and Chisari FV (1999). Noncytopathic clearance of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus from the hepatocyte. J. Exp. Med. 189, 1555–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannacone M, Sitia G, Isogawa M, Marchese P, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR, Chisari FV, Ruggeri ZM, and Guidotti LG (2005). Platelets mediate cytotoxic T lymphocyte-induced liver damage. Nat. Med. 11, 1167–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannacone M, Sitia G, Isogawa M, Whitmire JK, Marchese P, Chisari FV, Ruggeri ZM, and Guidotti LG (2008). Platelets prevent IFN-alpha/beta-induced lethal hemorrhage promoting CTL-dependent clearance of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogawa M, Chung J, Murata Y, Kakimi K, and Chisari FV (2013). CD40 activation rescues antiviral CD8⁺ T cells from PD-1-mediated exhaustion. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs F, Wisse E, and De Geest B (2010). The role of liver sinusoidal cells in hepatocyte-directed gene transfer. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Sastry KSR, Tiefenthaler G, Cano J, Tang T, Ho ZZ, Teoh D, Bohini S, Chen A, Sankuratri S, et al. (2012). Targeted delivery of interferon-a to hepatitis B virus-infected cells using T-cell receptor-like antibodies. Hepatology 56, 2027–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson C, Hällgren R, Elvin A, Gerdin B, and Tufveson G (1999). Hyaluronidase ameliorates rejection-induced edema. Transpl. Int. 12, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PA, Contaldo C, Georgiev P, El-Badry AM, Recher M, Kurrer M, Cervantes-Barragan L, Ludewig B, Calzascia T, Bolinger B, et al. (2008). Aggravation of viral hepatitis by platelet-derived serotonin. Nat. Med. 14, 756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W-Y, and Kubes P (2008). Leukocyte adhesion in the liver: distinct adhesion paradigm from other organs. J. Hepatol. 48, 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjunath N, Shankar P, Wan J, Weninger W, Crowley MA, Hieshima K, Springer TA, Fan X, Shen H, Lieberman J, and von Andrian UH (2001). Effector differentiation is not prerequisite for generation of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 871–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, and Lefranc¸ ois L (2001). Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science 291, 2413–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B, McAvoy EF, Lam F, Gill V, de la Motte C, Savani RC, and Kubes P (2008). Interaction of CD44 and hyaluronan is the dominant mechanism for neutrophil sequestration in inflamed liver sinusoids. J. Exp. Med. 205, 915–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SN (2013). Effector T-cell responses in non-lymphoid tissues: insights from in vivo imaging. Immunol. Cell Biol. 91, 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sironi L, Bouzin M, Inverso D, D’Alfonso L, Pozzi P, Cotelli F, Guidotti LG, Iannacone M, Collini M, and Chirico G (2014). In vivo flow mapping in complex vessel networks by single image correlation. Sci. Rep. 4, 7341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitia G, Iannacone M, Aiolfi R, Isogawa M, van Rooijen N, Scozzesi C, Bianchi ME, von Andrian UH, Chisari FV, and Guidotti LG (2011). Kupffer cells hasten resolution of liver immunopathology in mouse models of viral hepatitis. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzl MF, Oberwinkler H, Schaller H, and Protzer U (2001). Transfer of hepatitis B virus genome by adenovirus vectors into cultured cells and mice: crossing the species barrier. J. Virol. 75, 5108–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub AC, Stolz DB, Ross MA, Hernández-Zavala A, Soucy NV, Klei LR, and Barchowsky A (2007). Arsenic stimulates sinusoidal endothelial cell capillarization and vessel remodeling in mouse liver. Hepatology 45, 205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonti E, Jiménez de Oya N, Galliverti G, Moseman EA, Di Lucia P, Amabile A, Sammicheli S, De Giovanni M, Sironi L, Chevrier N, et al. (2013). Bisphosphonates target B cells to enhance humoral immune responses. Cell Rep. 5, 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Andrian UH, and Mackay CR (2000). T-cell function and migration. Two sides of the same coin. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 1020–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Russell S, and Ruggeri ZM (2000). Generation and rescue of a murine model of platelet dysfunction: the Bernard-Soulier syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2803–2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren A, Le Couteur DG, Fraser R, Bowen DG, McCaughan GW, and Bertolino P (2006). T lymphocytes interact with hepatocytes through fenestrations in murine liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology 44, 1182–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland SF, and Chisari FV (2005). Stealth and cunning: hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses. J. Virol. 79, 9369–9380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CHY, Jenne CN, Lee WY, Léger C, and Kubes P (2011). Functional innervation of hepatic iNKT cells is immunosuppressive following stroke. Science 334, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CHY, Jenne CN, Petri B, Chrobok NL, and Kubes P (2013). Nucleation of platelets with blood-borne pathogens on Kupffer cells precedes other innate immunity and contributes to bacterial clearance. Nat. Immunol. 14, 785–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Katoh S, He Q, Oritani K, Miyake K, Lesley J, Hyman R, Hamik A, Parkhouse RM, Farr AG, and Kincade PW (1995). Monoclonal antibodies to CD44 and their influence on hyaluronan recognition. J. Cell Biol. 130, 485–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.