Abstract

Aims

Heart failure (HF) is a global health issue, with lipid metabolism and inflammation critically implicated in its progression. This study harnesses cutting‐edge, expanded genetic information for lipid and inflammatory protein profiles, employing Mendelian randomization (MR) to uncover genetic risk factors for HF.

Methods

We assessed genetic susceptibility to HF across 179 lipidomes and 91 inflammatory proteins using instrumental variables (IVs) from recent genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) and proteome‐wide quantitative trait loci (pQTL) studies. GWASs involving 47 309 HF cases and 930 014 controls were obtained from the Heart Failure Molecular Epidemiology for Therapeutic Targets (HERMES) Consortium. Data on 179 lipids from 7174 individuals in a Finnish cohort and 91 inflammatory proteins from a European pQTL study involving 14 824 individuals are available in the HGRI‐EBI catalogue. A two‐sample MR approach evaluated the associations, and a two‐step mediation analysis explored the mediation role of inflammatory proteins in the lipid–HF pathway. Sensitivity analyses, including MR‐RAPS (robust adjusted profile score) and MR‐Egger, ensured result robustness.

Results

Genetic IVs for 162 lipids and 74 inflammatory proteins were successfully identified. MR analysis revealed a genetic association between HF and 31 lipids. Among them, 18 lipids, including sterol ester (27:1/18:0), cholesterol, 9 phosphatidylcholines, phosphatidylinositol (16:0_20:4) and 6 triacylglycerols, were identified as HF risk factors [odds ratio (OR) = 1.037–1.368]. Cholesterol exhibited the most significant association with elevated HF risk [OR = 1.368, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.044–1.794, P = 0.023]. In the inflammatory proteome, leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor (OR = 0.841, 95% CI = 0.789–0.897, P = 1.08E‐07), fibroblast growth factor 19 (OR = 0.905, 95% CI = 0.830–0.988, P = 0.025) and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator (OR = 0.938, 95% CI = 0.886–0.994, P = 0.030) were causally negatively correlated with HF, whereas interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha (OR = 1.333, 95% CI = 1.094–1.625, P = 0.004) was causally positively correlated with HF. Mediation analysis revealed leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor (mediation proportion: 23.5%–25.2%) and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator (mediation proportion: 9.5%–10.7%) as intermediaries in the lipid–inflammation–HF pathway. No evidence of directional horizontal pleiotropy was observed (P > 0.05).

Conclusions

This study identifies a genetic connection between certain lipids, particularly cholesterol, and HF, highlighting inflammatory proteins that influence HF risk and mediate this relationship, suggesting new therapeutic targets and insights into genetic drivers in HF.

Keywords: causality, heart failure, inflammatory proteome, lipidome, mediator, Mendelian randomization

Introduction

Heart failure (HF), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, underscores a significant public health issue by contributing substantially to the cardiovascular disease (CVD) burden globally. This condition is a complex clinical syndrome that stems from structural or functional cardiac disorders, impeding the ventricles' capacity to fill or eject blood. The traditional view ascribes the genesis of HF to factors such as myocardial infarction and hypertension, which induce cardiac remodelling and dysfunction over time. 1 Yet, a more nuanced understanding has emerged, recognizing the interplay of metabolic abnormalities, inflammatory markers and genetic variants in influencing the continuum of HF, and abnormalities in lipid metabolism may influence HF progression through inflammation. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

Contemporary genomic and proteomic advancements have paved the way for a revolution in cardiovascular pathology, offering unprecedented insight into the biological underpinnings of HF. Genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) have shed light on novel genetic loci associated with HF while elucidating the contribution of metabolic disturbances and inflammatory processes to its pathogenesis. 6 , 7 , 8 A Mendelian randomization (MR) framework for causal inference based on genetic data is also progressively establishing correlations between plasma lipids and associated protein profiles and HF. 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 These studies have moved beyond conventional risk factors and conventional lipids, such as low‐density lipoprotein‐cholesterol (LDL‐C) and high‐density lipoprotein‐cholesterol (HDL‐C), in relation to HF, revealing how specific lipid profiles and inflammatory markers may modulate HF risk, potentially ushering in a new era of prognostic assessment and targeted treatments.

This investigation seeks to extend these insights, employing MR to dissect the causal interconnections between a diverse range of lipids, inflammatory mediators and HF. Moving beyond traditional plasma lipid profiles and inflammatory protein profiles, the identification of key biomarkers of HF using the newly released large‐scale GWASs and proteome‐wide quantitative trait loci (pQTL) studies is not only scientifically imperative but also transformative for patient care, paving the way for more personalized and effective HF prevention and management strategies. 14 , 15 , 16

Methods

Study design

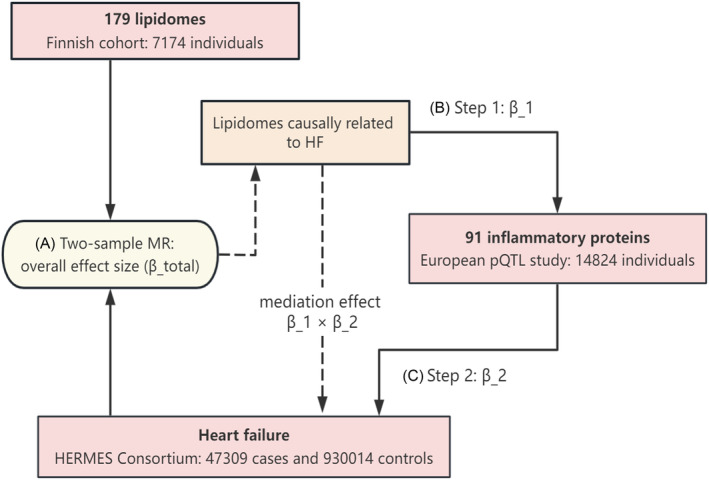

We aimed to identify inheritable risk factors for HF, focusing on lipid profiles and inflammatory proteins. By employing a two‐sample MR strategy, we assessed genetic susceptibilities across 179 lipid categories and 91 inflammatory protein groups, utilizing genetic instrumental variables (IVs) for these groups based on extensive GWASs. Additionally, we investigated the potential mediating role of inflammation in the process by which lipids might increase the risk of HF, using a two‐step MR approach to analyse possible mediating effects. A brief workflow is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study design schematic. Two‐sample Mendelian randomization (MR) was first used to assess the causal association between 179 lipids and heart failure (HF) and to derive the total causal effect (β_total) to obtain the associated lipids. Subsequently, two‐step MR was used to assess the mediation effect of inflammatory factors, with the first step assessing the causal effect of liposomes causally associated with HF on the inflammatory proteome (β_1) and the second step assessing 91 inflammatory proteomes causally associated with HF to derive the causal effect (β_2), which thus allowed for the calculation of the mediation effect (β_1 × β_2). A–C denote the order of MR estimation performed. HERMES, Heart Failure Molecular Epidemiology for Therapeutic Targets; pQTL, proteome‐wide quantitative trait loci.

Access to the GWAS summary statistics

The genetic basis of our HF analysis is derived from a comprehensive GWAS meta‐analysis under the Heart Failure Molecular Epidemiology for Therapeutic Targets (HERMES) Consortium, involving 47 309 HF cases and 930 014 controls of European descent across 26 studies [accession number from the Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) open GWAS project: ebi‐a‐GCST009541]. 16 Additionally, our study incorporates lipidomic data from an in‐depth analysis of 179 lipid species within a Finnish cohort of 7174 individuals, alongside 91 inflammatory protein data from a 14 824 European participants' pQTL study. 14 , 15 These data are catalogued in the HGRI‐EBI (lipidome: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/publications/37907536; accession numbers: GCST90277238 to GCST90277416; inflammatory proteome: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwHF/publications/37563310; accession numbers: GCST90274758 to GCST90274848). Detailed information on 179 lipidome summary data is provided in Table S1 and 91 inflammatory proteins in Table S2. These datasets, adhering to ethical standards set by their original studies, do not require further ethical approval for our reanalysis.

Genetic instruments for causal interference

To infer causality between lipid profiles, inflammatory proteins and HF, we utilized IVs as genetic proxies identified from GWASs based on significant genetic correlations (P < 5E‐8) and minimal linkage disequilibrium with r 2 < 0.001 in a 10 000 kb window. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with F‐statistic values below 10 were excluded due to weak instrumental validity. Phenotypes without SNPs that fulfil the requirements of strong correlation and independence will be considered to have no usable IVs and will not be used for subsequent analyses. Adhering to the exclusion restriction assumption of MR, we only included SNPs that were associated with lipids and inflammatory protein levels, independent of confounders that may affect HF risk. 17

Statistical analysis

Causal estimates of the lipidome, inflammatory proteome and HF

Following the identification of the IVs for each lipid and inflammatory protein phenotype, we conducted the causality analysis using the TwoSampleMR package (Version 0.5.8) in R (Version 4.3.1) by employing diverse methods contingent upon the quantity and characteristics of the IVs. The inverse variance weighting (IVW) method was used for attributes with multiple IVs, which operates under the premise that all IVs are valid without any interaction among them, an assumption that is ideal for scenarios with complex IVs. For traits associated with only one IV, we utilized the Wald ratio method for a straightforward causality estimate of singular risk factors. To strengthen the validity of our results and reduce the probability of false discoveries, we applied the MR‐RAPS (robust adjusted profile score) technique via the mr.raps package (Version 0.4.1). 18 This advanced method calibrates the scores to provide stable and normal estimations, improving the accuracy of our MR evaluations. We accepted a P value of <0.05 as our threshold for statistical significance, consciously deciding against a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons to preserve the exploratory intent of our research and to avoid overlooking any potential connections with HF. For cases analysing over three IVs for an individual trait, we also included MR‐Egger regression to test for pleiotropy. An intercept with a P value above 0.05 was indicative of negligible pleiotropic effects, which reinforced the credibility of our causal findings.

Intermediary role of inflammatory proteins in the lipid–HF causal pathway

Our research further investigated the potential pathways by which lipids could influence the risk of HF through their effects on inflammatory proteins. By applying a two‐step MR analysis, we first established the direct impact of lipid profiles on HF. 19 We calculated the overall effect size of this relationship (β_total). Then, we identified which inflammatory proteins have a statistically significant connection with HF and determined their effect size (β_2). This allowed us to estimate the potential indirect effect of lipids on HF risk through these proteins. We continued our inquiry by analysing the interactions between relevant lipids and these particular inflammatory proteins (β_1). Through this, we developed a hypothetical indirect pathway, suggesting that lipid levels could modify HF risk by altering inflammatory protein concentrations (mediation proportion = β_1 * β_2/β_total). Our investigative approach remained exploratory, keeping the significance level for our IVW/Wald ratio assessments and other robust methods at P < 0.05, facilitating the identification of potential genetic links between lipid metabolism, inflammatory processes and HF development.

Results

Lipidome causally related to HF

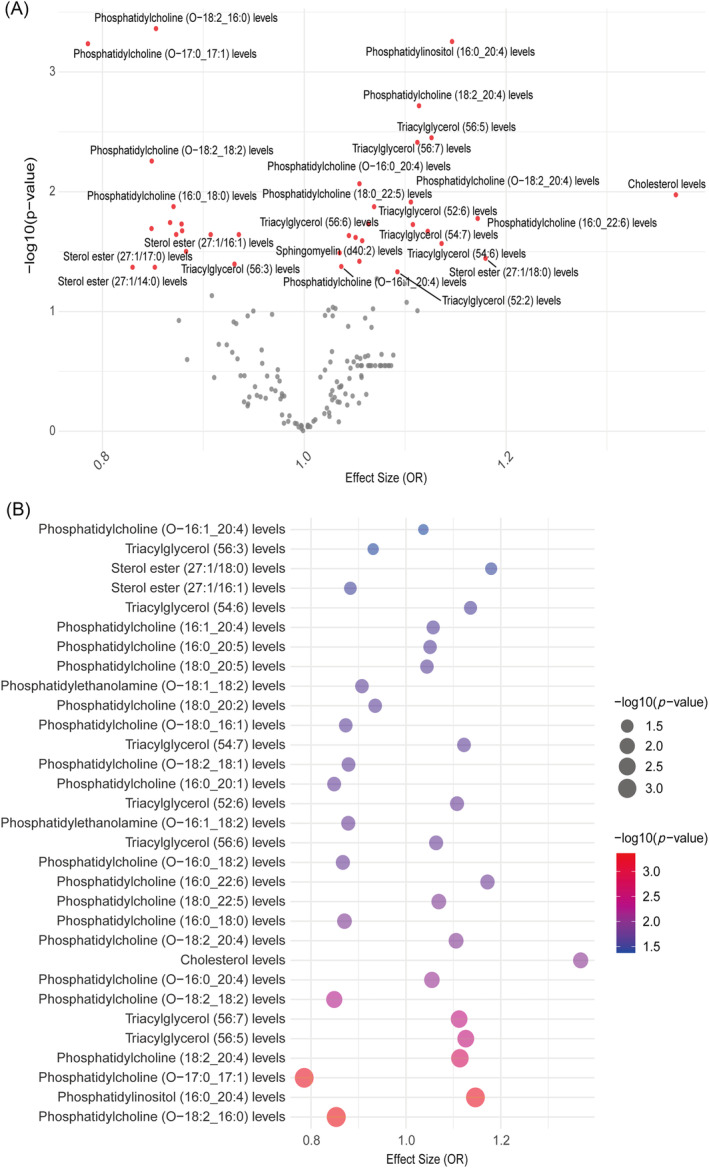

To evaluate the causal connections between 179 lipid species and HF, our initial step involved identifying IVs for these lipids. Based on the strong correlation and independence requirements, we successfully identified the IVs of 162 lipids and computed the F‐statistic values (29.79–1946.15), which showed that there was no weak instrumental bias (Table S3). MR results of these lipids with IVs co‐ordinated with GWAS data on HF indicated that 36 lipids were genetically causally associated with HF (Figure 2A and Table S4). This preliminary finding highlights an important subset of the lipid group with a potential impact on HF risk. To reinforce the MR findings, robust RAPS analysis of the associated 36 lipids revealed that 31 lipids passed the significance test, including 2 sterol esters, cholesterol, 18 phosphatidylcholines, 2 phosphatidylethanolamines, 1 phosphatidylinositol and 7 triacylglycerols (Figure 2B and Table 1). Among these, 18 lipids [sterol ester (27:1/18:0), cholesterol, 9 phosphatidylcholines, phosphatidylinositol (16:0_20:4) and 6 triacylglycerols] emerged as high‐frequency HF risk factors [odds ratio (OR) = 1.037–1.368], whereas 13 lipids, including 9 phosphatidylcholines, showed protective characteristics against HF (OR = 0.786–0.935). Importantly, cholesterol was identified as the lipid most strongly associated with increased HF risk [OR = 1.368, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.044–1.794, P = 0.023] (Figure 2B and Table 1). To assess directional horizontal pleiotropy, the Egger intercept test was applied to phenotypes with more than three IVs, and P values were consistently >0.05, indicating that MR assessments were not biased due to pleiotropy, thus strengthening the validity of our causal inferences (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mendelian randomization (MR) estimates for lipidome and heart failure (HF). (A) The volcano plot reveals that 36 lipid species exhibited significant causal associations with HF (red dots). (B) The bubble plot indicates that the causal relationship between 31 lipids and HF was confirmed by the robust MR method, of which 18 were risk factors and 13 were protective factors. OR, odds ratio.

Table 1.

Robust adjusted profile score assessment of lipids shown to be significantly causally associated with heart failure by traditional Mendelian randomization methods.

| ID.exposure | Trait.exposure | ID.outcome | Trait.outcome | nsnp | Beta | SE | P value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCST90277238 | Sterol ester (27:1/14:0) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.160 | 0.085 | 0.059 | 0.852 |

| GCST90277241 | Sterol ester (27:1/16:1) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | −0.125 | 0.063 | 0.047 | 0.883 |

| GCST90277242 | Sterol ester (27:1/17:0) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.186 | 0.100 | 0.063 | 0.830 |

| GCST90277244 | Sterol ester (27:1/18:0) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 6 | 0.182 | 0.079 | 0.020 | 1.200 |

| GCST90277257 | Cholesterol levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | 0.314 | 0.138 | 0.023 | 1.368 |

| GCST90277280 | Phosphatidylcholine (16:0_18:0) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.139 | 0.060 | 0.020 | 0.870 |

| GCST90277284 | Phosphatidylcholine (16:0_20:1) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.164 | 0.077 | 0.033 | 0.849 |

| GCST90277288 | Phosphatidylcholine (16:0_20:5) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | 0.050 | 0.023 | 0.029 | 1.051 |

| GCST90277291 | Phosphatidylcholine (16:0_22:6) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | 0.159 | 0.072 | 0.027 | 1.172 |

| GCST90277295 | Phosphatidylcholine (16:1_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | 0.056 | 0.026 | 0.031 | 1.057 |

| GCST90277302 | Phosphatidylcholine (18:0_20:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.067 | 0.031 | 0.028 | 0.935 |

| GCST90277305 | Phosphatidylcholine (18:0_20:5) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.043 | 0.020 | 0.028 | 1.044 |

| GCST90277306 | Phosphatidylcholine (18:0_22:5) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.067 | 0.028 | 0.017 | 1.069 |

| GCST90277317 | Phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 4 | 0.109 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 1.115 |

| GCST90277321 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐16:0_18:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | −0.145 | 0.049 | 0.003 | 0.865 |

| GCST90277323 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐16:0_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | 0.053 | 0.021 | 0.011 | 1.055 |

| GCST90277330 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐16:1_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.048 | 1.037 |

| GCST90277333 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐17:0_17:1) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.241 | 0.082 | 0.003 | 0.786 |

| GCST90277335 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:0_16:1) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.136 | 0.065 | 0.037 | 0.873 |

| GCST90277341 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:2_16:0) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | −0.160 | 0.049 | 0.001 | 0.852 |

| GCST90277342 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:2_18:1) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.129 | 0.060 | 0.030 | 0.879 |

| GCST90277343 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:2_18:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | −0.166 | 0.048 | 0.001 | 0.847 |

| GCST90277344 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:2_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.101 | 0.042 | 0.017 | 1.106 |

| GCST90277348 | Phosphatidylethanolamine (18:0_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 7 | 0.034 | 0.018 | 0.065 | 1.034 |

| GCST90277350 | Phosphatidylethanolamine (O‐16:1_18:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.130 | 0.059 | 0.028 | 0.878 |

| GCST90277353 | Phosphatidylethanolamine (O‐18:1_18:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | −0.097 | 0.045 | 0.030 | 0.907 |

| GCST90277360 | Phosphatidylinositol (16:0_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | 0.138 | 0.043 | 0.001 | 1.148 |

| GCST90277377 | Sphingomyelin (d40:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 6 | 0.055 | 0.030 | 0.060 | 1.057 |

| GCST90277396 | Triacylglycerol (52:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | 0.089 | 0.047 | 0.057 | 1.093 |

| GCST90277400 | Triacylglycerol (52:6) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.103 | 0.046 | 0.025 | 1.109 |

| GCST90277407 | Triacylglycerol (54:6) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.130 | 0.059 | 0.028 | 1.138 |

| GCST90277408 | Triacylglycerol (54:7) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.116 | 0.053 | 0.029 | 1.123 |

| GCST90277409 | Triacylglycerol (56:3) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | −0.073 | 0.037 | 0.048 | 0.930 |

| GCST90277411 | Triacylglycerol (56:5) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 2 | 0.119 | 0.044 | 0.006 | 1.126 |

| GCST90277412 | Triacylglycerol (56:6) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 4 | 0.063 | 0.027 | 0.021 | 1.065 |

| GCST90277413 | Triacylglycerol (56:7) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | 0.106 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 1.112 |

Abbreviations: nsnp, number of single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error of effect size.

Table 2.

Directional horizontal pleiotropy assessment by MR‐Egger regression.

| Exposure | ID.exposure | Trait.exposure | ID.outcome | Trait.outcome | Egger_intercept | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipidome | GCST90277244 | Sterol ester (27:1/18:0) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.027 | 0.065 | 0.701 |

| GCST90277317 | Phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.012 | 0.020 | 0.617 | |

| GCST90277323 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐16:0_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.744 | |

| GCST90277330 | Phosphatidylcholine (O‐16:1_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.009 | 0.010 | 0.526 | |

| GCST90277348 | Phosphatidylethanolamine (18:0_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 0.023 | 0.013 | 0.142 | |

| GCST90277360 | Phosphatidylinositol (16:0_20:4) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.008 | 0.046 | 0.895 | |

| GCST90277377 | Sphingomyelin (d40:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.766 | |

| GCST90277396 | Triacylglycerol (52:2) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 0.044 | 0.051 | 0.546 | |

| GCST90277409 | Triacylglycerol (56:3) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.032 | 0.067 | 0.717 | |

| GCST90277412 | Triacylglycerol (56:6) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.00001 | 0.017 | 1.000 | |

| GCST90277413 | Triacylglycerol (56:7) levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.008 | 0.024 | 0.792 | |

| Inflammatory proteome | GCST90274820 | Leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.503 |

| GCST90274787 | Fibroblast growth factor 19 levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | −0.025 | 0.017 | 0.379 | |

| GCST90274847 | Urokinase‐type plasminogen activator levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.491 |

Abbreviations: MR, Mendelian randomization; SE, standard error.

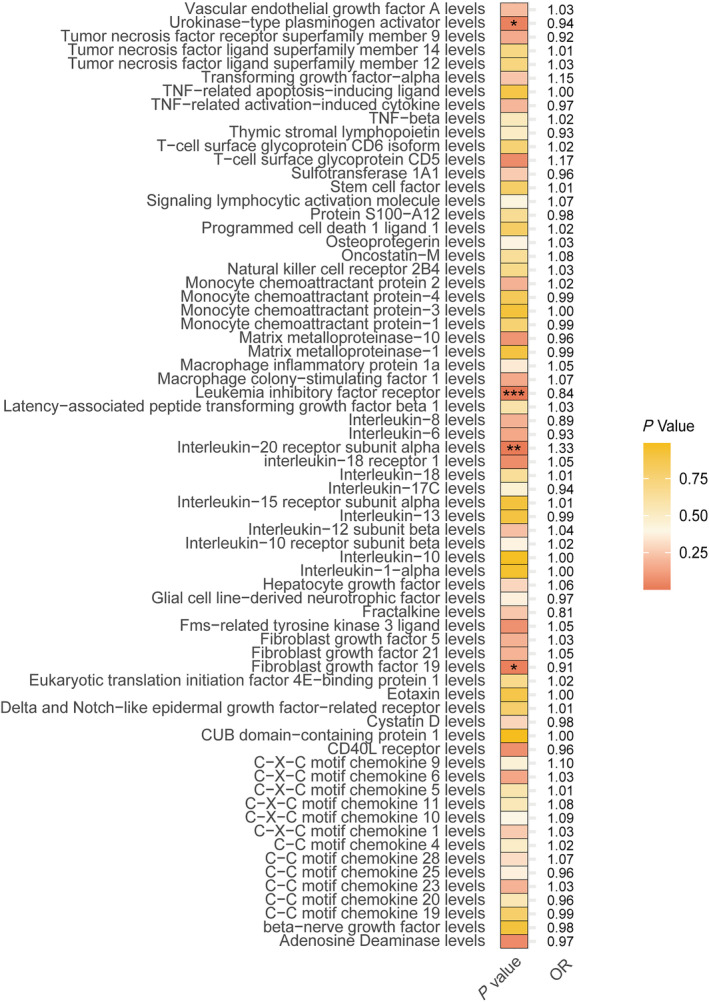

Inflammatory proteins genetically associated with HF

The role of inflammatory processes in HF progression is gaining recognition. To elucidate which specific inflammatory mediators are genetically importantly associated with HF, we obtained the latest 91 GWASs of inflammatory proteins. Based on our selection criteria, 74 of these proteins with IVs were deemed suitable for MR analysis, exhibiting robust instrumental validity with F‐statistic values spanning from 29.72 to 1472.93 (Table S5). Our MR analysis pinpointed four inflammatory proteins with a significant genetic correlation to HF: leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor (OR = 0.841, 95% CI = 0.789–0.897, P = 1.08E‐07), interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha (OR = 1.333, 95% CI = 1.094–1.625, P = 0.004), fibroblast growth factor 19 (OR = 0.905, 95% CI = 0.830–0.988, P = 0.025) and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator (OR = 0.938, 95% CI = 0.886–0.994, P = 0.030) (Figure 3 and Table S6). Robust RAPS analysis emphasized consistent causal estimates (Table 3). Notably, our analysis revealed that an increased level of interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha significantly heightens the risk of HF, and the Egger intercept test did not support the presence of pleiotropy (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Heatmap of the Mendelian randomization results for the inflammatory proteome and heart failure. OR, odds ratio. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Table 3.

Robust adjusted profile score estimates of inflammatory proteins shown to be significantly causally associated with heart failure by traditional Mendelian randomization methods.

| ID.exposure | Trait.exposure | ID.outcome | Trait.outcome | nsnp | Beta | SE | P value | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCST90274820 | Leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | −0.174 | 0.035 | 5.31E‐07 | 0.840 |

| GCST90274808 | Interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 1 | 0.288 | 0.115 | 0.012 | 1.333 |

| GCST90274787 | Fibroblast growth factor 19 levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 3 | −0.098 | 0.040 | 0.013 | 0.907 |

| GCST90274847 | Urokinase‐type plasminogen activator levels | GCST009541 | Heart failure | 8 | −0.064 | 0.031 | 0.036 | 0.938 |

Abbreviations: nsnp, number of single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error of effect size.

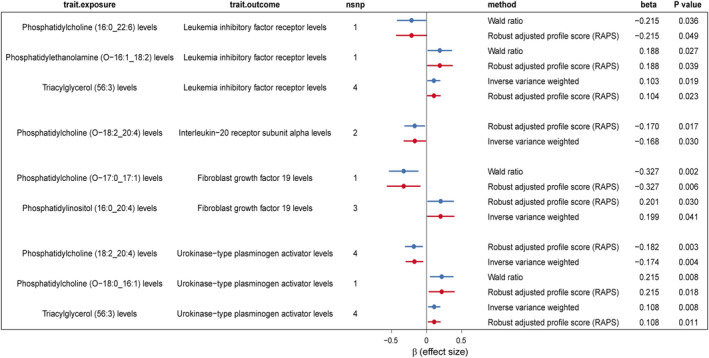

Inflammatory mediators as lipid–HF causal pathways

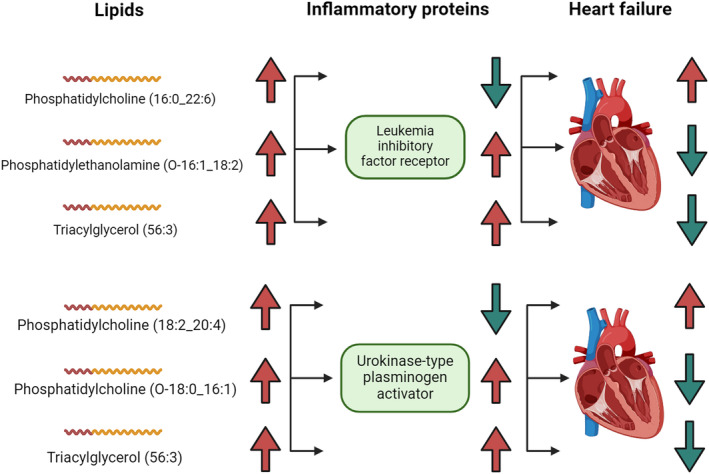

Given the potential for lipids to mediate the development of HF through inflammatory factors, we employed a two‐step MR approach to assess the possible mediating effects of four inflammation proteins associated with HF. We first focus on the leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor, which is inversely related to HF risk. The MR analysis of 31 lipids revealed that levels of phosphatidylethanolamine (O‐16:1_18:2) (β_1 = 0.188) and triacylglycerol (56:3) (β_1 = 0.104) positively correlated with leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor level, whereas phosphatidylcholine (16:0_22:6) (β_1 = −0.215) levels showed a negative correlation (Figure 4 and Table S7).

Figure 4.

Significantly mediated Mendelian randomization estimates of lipidome and inflammatory protein levels. nsnp, number of single nucleotide polymorphism.

Attempting to establish a mediation pathway, we examined the causal relationship of these three lipids with HF. Phosphatidylcholine (16:0_22:6) (β_total = 0.159) was directly proportional to HF risk, while phosphatidylethanolamine (O‐16:1_18:2) (β_total = −0.130) and triacylglycerol (56:3) (β_total = −0.073) showed an inverse relationship (Table 3). The coherent effect directions across lipid‐to‐HF, lipid‐to‐inflammatory protein and inflammatory protein‐to‐HF pathways suggest leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor (β_2 = −0.174) as a potential mediator in the phosphatidylcholine (16:0_22:6)–HF (mediation proportion = −0.215 * −0.174/0.159 = 23.5%) and other mentioned lipid–HF causal pathways [0.188 * −0.174/−0.130 = 25.2% in phosphatidylethanolamine (O‐16:1_18:2)–HF and 0.104 * −0.173/−0.073 = 24.8% in triacylglycerol (56:3)–HF].

Regarding the interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha, which positively correlates with HF risk, MR analysis indicated an inverse relationship between phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:2_20:4) levels and the interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha (Figure 4 and Table S8). Given the direct correlation of phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:2_20:4) levels with HF risk, the inconsistent effect directions do not support interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha as a mediator in the lipid–HF effect pathway. Conversely, for fibroblast growth factor 19, negatively associated with HF risk, two lipids, phosphatidylinositol (16:0_20:4) (positively correlated) and phosphatidylcholine (O‐17:0_17:1) (negatively correlated), were causally related to fibroblast growth factor 19 (Figure 4 and Table S9). Reviewing the lipid–HF relationships, phosphatidylinositol (16:0_20:4) was positively associated with HF, and phosphatidylcholine (O‐17:0_17:1) was negatively associated with HF (Table S4). Thus, similarly, fibroblast growth factor 19 was not assessed as a potential mediating effector.

Finally, among 31 lipids, three [phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4), triacylglycerol (56:3) and phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:0_16:1)] were significantly associated with urokinase‐type plasminogen activator through IVW/Wald ratio and RAPS significance tests. Phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4) (β_1 = −0.182) was inversely related to urokinase‐type plasminogen activator, while triacylglycerol (56:3) (β_1 = 0.108) and phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:0_16:1) (β_1 = 0.215) showed a positive correlation (Figure 4 and Table S10). In the causal relationship with HF, phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4) (β_total = 0.109) is a risk factor, whereas triacylglycerol (56:3) (β_total = −0.073) and phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:0_16:1) (β_total = −0.136) are potential protective factors (Table S4). Given the inverse relationship between urokinase‐type plasminogen activator and HF (β_2 = −0.064), higher levels of phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4) and lower levels of urokinase‐type plasminogen activator correlate with increased HF risk, suggesting urokinase‐type plasminogen activator as a mediator in the phosphatidylcholine (18:2_20:4)–HF effect pathway (−0.182 * −0.064/0.109 = 10.7%). Similarly, coherent effect directions identify urokinase‐type plasminogen activator as a potential mediator in the triacylglycerol (56:3) (0.108 * −0.064/−0.073 = 9.5%) and phosphatidylcholine (O‐18:0_16:1)–HF (0.215 * −0.064/−0.136 = 10.1%) causal pathways.

Taken together, the leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator are identified as potential inflammatory mediators in the lipid–HF causal pathways (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator identified as inflammatory mediators in the lipid–heart failure (HF) causal pathways. The arrows represent the direction of the risk effect, with red for increased levels or high HF risk and green for decreased levels or low HF risk. For example, when phosphatidylcholine (16:0_22:6) levels are elevated, leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor levels are reduced, and HF risk is increased.

Discussion

Our study contributes significant insights into the complex interplay between lipid profiles, inflammatory proteins and HF, leveraging a genetically inferred MR approach. By examining a broad spectrum of 179 lipid categories and 91 inflammatory proteins through genetic IVs derived from extensive GWASs and pQTL studies, we have identified novel genetic associations that underscore the potential mechanistic pathways influencing HF risk.

Causal relationships between lipids and HF

Our findings reveal a robust causal relationship between specific lipid species and HF, with 31 out of 179 lipid species being genetically associated with HF. Notably, cholesterol and certain phosphatidylcholines and triacylglycerols were highlighted as significant contributors to HF risk based on their OR. This observation is particularly significant considering the current understanding of lipid metabolism's role in CVDs, which has largely focused on the impact of total cholesterol, LDL‐C and HDL‐C levels. 5 , 6 , 20 , 21 Our study expands this view by pinpointing specific lipid molecules that may play crucial roles in the development of HF beyond the traditional lipid markers. 20 , 22 Phosphatidylcholines and triacylglycerols containing different fatty acids, for instance, have been less emphasized in cardiovascular risk assessment models, and refined molecular species functions are not adequately characterized. However, their significant association with HF risk in our study points towards their potential role in cardiac pathophysiology. Phosphatidylcholines are critical components of cell membranes and lipoproteins, and alterations in their composition have been linked to changes in lipoprotein functionality and atherosclerotic processes. 23 Rong et al. found that the up‐regulation of phosphatidylcholines (22:4_14:1) was closely associated with the HF indicator BNP. 23 The latest metabolomics profile from the Framingham Heart Study and an observational study of lipid profile and HF risk have suggested an association between phosphatidylcholines and HF events. 5 , 24 Specifically, each unit increase in phosphatidylcholine (32:0) was associated with a 1.23‐fold higher risk of HF. 5 Furthermore, our MR analysis identifies nine phosphatidylcholines as protective factors for HF. The functional roles of phosphatidylcholines are influenced by their fatty acid compositions and linkages to the glycerol backbone. Ether linkages, like in phosphatidylcholine (O‐16:0), may enhance membrane properties by increasing resistance to oxidative stress and altering membrane fluidity, contributing to their protective effects against HF. 25 Genetic informatics‐driven identification of specific lipid profiles associated with HF risk may more accurately indicate CVD risk, potentially because of their effects on inflammation, endothelial function and plaque stability. 26

Cholesterol: A significant causal risk factor for HF

Here, for the first time, cholesterol level was established as the most significant causal risk factor for HF, suggesting that the risk of HF would increase by approximately 40% for each unit change in cholesterol level. The unbiased results establish genetically beyond observational studies for the investigation of their relationship. 27 , 28 The association between cholesterol levels and HF risk further highlights the nuanced role of cholesterol in CVD beyond traditional atherosclerotic pathways. While elevated LDL‐C levels are well‐established risk factors for coronary artery disease, the specific role of cholesterol in HF pathogenesis may involve complex interactions with inflammatory pathways and cardiac energy metabolism. 29 Recent studies have shown that the depletion of carnitine acetyltransferase (CRAT) enhances cholesterol breakdown through the bile acid synthesis pathway. This process triggers chronic inflammation, which in turn accelerates the progression of HF, establishing an interconnection between cholesterol homeostasis and the immune‐inflammatory response of cardiomyocytes to HF. 29 , 30

Inflammatory proteins causally associated with HF

Furthermore, our investigation into the inflammatory proteins revealed four proteins—leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor, interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha, fibroblast growth factor 19 and urokinase‐type plasminogen activator—genetically associated with HF. This finding enriches the current dialogue on inflammation's role in CVD by identifying specific inflammatory pathways that may contribute to HF pathogenesis. The identification of inflammatory proteins, such as interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha, as risk factors for HF further illuminates the intricate interplay between lipid profiles and inflammatory pathways in cardiovascular pathology. 31 , 32 This is consistent with the growing body of evidence highlighting inflammation as a central mechanism in the development and progression of HF. 4 , 13 , 31 , 33 Observational studies have often linked members of the fibroblast growth factor family, especially fibroblast growth factors 21 and 23, to HF risk. However, MR studies have indicated that genetically inferred fibroblast growth factor 23 does not significantly increase HF risk. 34 , 35 More evidence is needed to support the association of fibroblast growth factor 9 with HF. The mediation analysis provides intriguing insights into how lipid levels could influence HF risk through inflammatory processes. We discovered potential pathways whereby specific lipids may modulate HF risk by altering concentrations of inflammatory proteins such as leukaemia inhibitory factor receptors and urokinase‐type plasminogen activators. Leukaemia inhibitory factor signalling is initiated by binding to the membrane‐bound leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor and gp130, activating the Janus kinase (Jak)–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3‐K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathways. It plays a key role in cardiomyocyte remodelling and shows cardioprotective effects under ischaemic conditions by reducing oxidative stress and cell death. 36 This is consistent with our finding that leukaemia inhibitory factor receptor is negatively associated with HF risk and that specific immune cell types may increase HF risk by decreasing levels of this inflammatory protein. Moreover, the urokinase‐type plasminogen activator and its soluble receptor are increasingly recognized as significant in HF, serving as biomarkers for disease severity and potential targets for therapeutic intervention. 37 , 38 These findings emphasize the importance of these inflammatory factors in the pathology of HF, and further research is needed to fully exploit their potential in clinical applications.

Strengths and limitations

The absence of evidence for directional horizontal pleiotropy in our results reinforces the potential causal relationship between identified lipids and inflammatory markers in HF. By using genetic IVs to infer causality, we circumvent the limitations of observational studies that can be confounded by lifestyle factors and reverse causation. This methodological strength enhances the reliability of our findings and provides a stronger basis for developing intervention strategies based on genetic susceptibilities. 39 While our study marks a significant step forward, further research is needed to elucidate the biological mechanisms through which these identified lipids and inflammatory proteins influence HF risk. Additionally, our study's limitations include potential biases in MR analysis and the generalizability of our findings. When interpreting our results, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations of the data used, such as measurement bias in the lipidomic and proteomic data. Importantly, it needs to be recognized that worsening HF is a complex disease in which the presence of any other pro‐inflammatory factor may influence its progression, 40 and the lack of further subdivision of the HF GWAS cohort into subtypes (e.g., ischaemic or non‐ischaemic) and stratification. Experimental studies in cellular and animal models could provide deeper insights into the pathophysiological processes involved. Clinical trials designed to modulate these specific lipid and inflammatory pathways could validate the therapeutic potential of our findings. Including populations from diverse ethnic backgrounds could enhance the generalizability of our findings and uncover population‐specific genetic risk factors for HF. More detailed background investigations could provide more clinically interpretable perspectives on newly identified targets.

Conclusion and future directions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a significant genetic association between specific lipids, notably cholesterol, and HF, along with identifying key inflammatory proteins that contribute to HF risk and may be a mediator in the lipid–HF causal pathway. These findings not only advance our understanding of HF pathogenesis but also point towards novel therapeutic targets that could transform HF management. As we move towards a more personalized medicine approach, integrating genetic risk factors with clinical strategies will be crucial in combating the global burden of HF.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 82073659).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. More information about genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) of 179 plasma lipidomes.

Table S2. More information about GWASs for 91 inflammatory proteins.

Table S3. Genetic instrumental variables (IVs) for lipidomes.

Table S4. Mendelian randomization (MR) estimates of lipidome and heart failure (HF).

Table S5. Genetic IVs of inflammatory proteomes.

Table S6. MR estimates of inflammatory proteomes and HF.

Table S7. MR estimates of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Table S8. MR estimates of interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Table S9. MR estimates of fibroblast growth factor 19 levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Table S10. MR estimates of urokinase‐type plasminogen activator levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Acknowledgements

We thank the researchers who provided the shared data that made this study possible.

Zheng, Z. , and Tan, X. (2024) Mendelian randomization of plasma lipidome, inflammatory proteome and heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 11: 4209–4221. 10.1002/ehf2.14997.

Contributor Information

Zequn Zheng, Email: 13414057384@163.com.

Xuerui Tan, Email: doctortxr@126.com.

Data availability statement

All the data supporting the findings of this study are included in this article and its supporting information.

References

- 1. Skrzynia C, Berg JS, Willis MS, Jensen BC. Genetics and heart failure: A concise guide for the clinician. Curr Cardiol Rev 2015;11:10‐17. doi: 10.2174/1573403x09666131117170446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Hoef CCS, Boorsma EM, Emmens JE, van Essen BJ, Metra M, Ng LL, et al. Biomarker signature and pathophysiological pathways in patients with chronic heart failure and metabolic syndrome. Eur J Heart Fail 2023;25:163‐173. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rao A, Gupta A, Kain V, Halade GV. Extrinsic and intrinsic modulators of inflammation‐resolution signaling in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2023;325:H433‐H448. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00276.2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halade GV, Lee DH. Inflammation and resolution signaling in cardiac repair and heart failure. EBioMedicine 2022;79:103992. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wittenbecher C, Eichelmann F, Toledo E, Guasch‐Ferré M, Ruiz‐Canela M, Li J, et al. Lipid profiles and heart failure risk: Results from two prospective studies. Circ Res 2021;128:309‐320. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiao J, Ji J, Zhang N, Yang X, Chen K, Chen L, et al. Association of genetically predicted lipid traits and lipid‐modifying targets with heart failure. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2023;30:358‐366. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwac290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fullenkamp DE, Puckelwartz MJ, McNally EM. Genome‐wide association for heart failure: From discovery to clinical use. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2012‐2014. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Henry A, Gordillo‐Marañón M, Finan C, Schmidt AF, Ferreira JP, Karra R, et al. Therapeutic targets for heart failure identified using proteomics and Mendelian randomization. Circulation 2022;145:1205‐1217. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels, LPA risk genotypes, and increased risk of heart failure in the general population. JACC Heart Failure 2016;4:78‐87. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li X, Chan JSK, Guan B, Peng S, Wu X, Lu X, et al. Triglyceride‐glucose index and the risk of heart failure: Evidence from two large cohorts and a Mendelian randomization analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022;21:229. doi: 10.1186/s12933-022-01658-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moncla LM, Mathieu S, Sylla MS, Bossé Y, Thériault S, Arsenault BJ, et al. Mendelian randomization of circulating proteome identifies actionable targets in heart failure. BMC Genomics 2022;23:588. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08811-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin L, Yu H, Xue Y, Wang L, Zhu P. Proteome‐wide Mendelian randomization investigates potential associations in heart failure and its etiology: Emphasis on PCSK9. BMC Med Genomics 2024;17:59. doi: 10.1186/s12920-024-01826-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Remmelzwaal S, van Oort S, Handoko ML, van Empel V, Heymans SRB, Beulens JWJ. Inflammation and heart failure: A two‐sample Mendelian randomization study. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2022;23:728‐735. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000001373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ottensmann L, Tabassum R, Ruotsalainen SE, Gerl MJ, Klose C, Widén E, et al. Genome‐wide association analysis of plasma lipidome identifies 495 genetic associations. Nat Commun 2023;14:6934. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42532-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao JH, Stacey D, Eriksson N, Macdonald‐Dunlop E, Hedman ÅK, Kalnapenkis A, et al. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune‐mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol 2023;24:1540‐1551. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01635-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah S, Henry A, Roselli C, Lin H, Sveinbjörnsson G, Fatemifar G, et al. Genome‐wide association and Mendelian randomisation analysis provide insights into the pathogenesis of heart failure. Nat Commun 2020;11:163. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13690-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: Genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:R89‐R98. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao Q, Wang J, Hemani G, Bowden J, Small DS. Statistical inference in two‐sample summary‐data Mendelian randomization using robust adjusted profile score. Ann Statist 2020;48:1742‐1769. doi: 10.1214/19-AOS1866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carter AR, Sanderson E, Hammerton G, Richmond RC, Davey Smith G, Heron J, et al. Mendelian randomisation for mediation analysis: Current methods and challenges for implementation. Eur J Epidemiol 2021;36:465‐478. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00757-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poloczková H, Krejčí J. Heart failure treatment in 2023: Is there a place for lipid lowering therapy? Curr Atheroscler Rep 2023;25:957‐964. doi: 10.1007/s11883-023-01166-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koohi F, Khalili D, Mansournia MA, Hadaegh F, Soori H. Multi‐trajectories of lipid indices with incident cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and all‐cause mortality: 23 years follow‐up of two US cohort studies. J Transl Med 2021;19:286. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02966-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Velagaleti RS, Massaro J, Vasan RS, Robins SJ, Kannel WB, Levy D. Relations of lipid concentrations to heart failure incidence: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2009;120:2345‐2351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.830984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rong J, He T, Zhang J, Bai Z, Shi B. Serum lipidomics reveals phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine disorders in patients with myocardial infarction and post‐myocardial infarction‐heart failure. Lipids Health Dis 2023;22:66. doi: 10.1186/s12944-023-01832-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Y, Gray A, Xue L, Farb MG, Ayalon N, Andersson C, et al. Metabolomic profiles, ideal cardiovascular health, and risk of heart failure and atrial fibrillation: Insights from the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2023;12:e028022. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.028022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dean JM, Lodhi IJ. Structural and functional roles of ether lipids. Protein Cell 2018;9:196‐206. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0423-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hunter WG, McGarrah RW 3rd, Kelly JP, Khouri MG, Craig DM, Haynes C, et al. High‐density lipoprotein particle subfractions in heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:177‐186. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Francis GS. Cholesterol and heart failure: Is there an important connection? J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2137‐2138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan JSK, Satti DI, Lee YHA, Hui JMH, Lee TTL, Chou OHI, et al. High visit‐to‐visit cholesterol variability predicts heart failure and adverse cardiovascular events: A population‐based cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022;29:e323‐e325. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwac097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim GB. Cholesterol catabolism and bile acid synthesis in cardiomyocytes promote inflammation and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2023;20:647. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00917-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mao H, Angelini A, Li S, Wang G, Li L, Patterson C, et al. CRAT links cholesterol metabolism to innate immune responses in the heart. Nat Metab 2023;5:1382‐1394. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00844-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hanna A, Frangogiannis NG. Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as therapeutic targets in heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2020;34:849‐863. doi: 10.1007/s10557-020-07071-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Everett BM, Siddiqi HK. Heart failure, the inflammasome, and interleukin‐1β: Prognostic and therapeutic? J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1026‐1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reina‐Couto M, Vale L, Carvalho J, Bettencourt P, Albino‐Teixeira A, Sousa T. Resolving inflammation in heart failure: Novel protective lipid mediators. Curr Drug Targets 2016;17:1206‐1223. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666160101121135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donovan K, Herrington WG, Paré G, Pigeyre M, Haynes R, Sardell R, et al. Fibroblast growth factor‐23 and risk of cardiovascular diseases: A Mendelian randomization study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol: CJASN 2023;18:17‐27. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05080422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan H, Yue T, Chen Z, Wu W, Xu S, Weng J. Targeting FGF21 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases: From mechanism to medicine. Int J Biol Sci 2023;19:66‐88. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.73936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kubin T, Gajawada P, Bramlage P, Hein S, Berge B, Cetinkaya A, et al. The role of oncostatin M and its receptor complexes in cardiomyocyte protection, regeneration, and failure. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:1811. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koller L, Stojkovic S, Richter B, Sulzgruber P, Potolidis C, Liebhart F, et al. Soluble urokinase‐type plasminogen activator receptor improves risk prediction in patients with chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Failure 2017;5:268‐277. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hayek SS, Tahhan AS, Ko YA, Alkhoder A, Zheng S, Bhimani R, et al. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor levels and outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 2023;29:158‐167. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2022.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Larsson SC, Butterworth AS, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: Principles and applications. Eur Heart J 2023;44:4913‐4924. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Savarese G, Anker MS, Anker SD. Iron deficiency as a promoter of cardiotoxicity: Not only cadmium‐induced. Eur Heart J 2023;44:2641. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. More information about genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) of 179 plasma lipidomes.

Table S2. More information about GWASs for 91 inflammatory proteins.

Table S3. Genetic instrumental variables (IVs) for lipidomes.

Table S4. Mendelian randomization (MR) estimates of lipidome and heart failure (HF).

Table S5. Genetic IVs of inflammatory proteomes.

Table S6. MR estimates of inflammatory proteomes and HF.

Table S7. MR estimates of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Table S8. MR estimates of interleukin‐20 receptor subunit alpha levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Table S9. MR estimates of fibroblast growth factor 19 levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Table S10. MR estimates of urokinase‐type plasminogen activator levels and lipids causally associated with HF.

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the findings of this study are included in this article and its supporting information.