Abstract

Multifaceted natural killer (NK) cell activities are indispensable for controlling human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 transmission and pathogenesis. Among the diverse functions of NK cells, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) has been shown to predict better HIV-1 protection. ADCC is initiated by the engagement of an Fc γ receptor CD16 with an Fc portion of the antibody, leading to phosphorylation of the CD3 ζ chain (CD3ζ) and Fc receptor γ chain (FcRγ) as well as downstream signaling activation. Though CD3ζ and FcRγ were thought to have overlapping roles in NK cell ADCC, several groups have reported that CD3ζ-mediated signals trigger a more robust ADCC. However, few studies have illustrated the direct contribution of CD3ζ in HIV-1-specific ADCC. To further understand the roles played by CD3ζ in HIV-1-specific ADCC, we developed a CD3ζ knockdown system in primary human NK cells. We observed that HIV-1-specific ADCC was inhibited by CD3ζ perturbation. In summary, we demonstrated that CD3ζ is important for eliciting HIV-1-specific ADCC, and this dynamic can be utilized for NK cell immunotherapeutics against HIV-1 infection and other diseases.

Keywords: natural killer cell, HIV, SIV, cell signaling

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells exert diverse effector functions that are critical for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 control.1–6 Specifically, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is a major contributor of HIV-1 control.1,7,8 Others have elucidated that in the RV144 and VAX003 vaccine trials, individuals with better control of HIV-1 infection following vaccination exhibited higher levels of HIV-1-specific immunoglobulin G3 (IgG3) antibodies, which are potent inducers of NK cell ADCC.7,9 Similarly in nonhuman primate (NHP) models, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) protection is strongly correlated with robust SIV-specific ADCC activities.8 To trigger ADCC, the Fc portion of the antibody binds to CD16, a low-affinity Fc γ receptor IIIa, on NK cells, which induces phosphorylation of CD3 ζ chain (CD3ζ) and Fc receptor γ chain (FcRγ) adaptor molecules.10 This event initiates subsequent signaling activation, which induces NK cell ADCC as a consequence.11–21

Due to the association of CD16 with both CD3ζ and FcRγ,10,22 it has often been thought to trigger similar activation signals for NK cell ADCC. However, multiple lines of evidence indicate that NK cells preferentially utilize CD3ζ to exert more robust ADCC.11,23–26 One subset of human and rhesus macaque (RM) NK cells without FcRγ expression, referred to as g- or Δg NK cells,11,23,25,27,28 is specialized in ADCC responses, and it primarily depends on CD3ζ for relaying signals from CD16.11,29 Recently, Tuyishime et al. illustrated that the magnitude of CD3ζ phosphorylation positively correlates with NK cell ADCC potency in humans.30 People experiencing systemic lupus erythematosus also exhibited lower CD3ζ expression in their NK cells, and their NK cell ADCC activity is positively associated with the levels of CD3ζ.26 A recent study performed by Liu et al. documented that FcRγ knockout in primary NK cells using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats knockout technique did not perturb NK cell responses via CD16 stimulation.31 While these reports imply the importance of CD3ζ in NK cell ADCC, few studies have directly elucidated its contribution to overall NK cell ADCC through modulation of CD3ζ expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA) gene knockdown. Specifically in HIV-1 infection, the link between CD3ζ and potent HIV-1-specific ADCC activities is yet to be definitively established. Hence, in order to fill this knowledge gap, we investigated whether the reduction of CD3ζ expression by siRNA knockdown can diminish HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC.

Materials and Methods

NK cell expansion

Healthy human blood specimens were obtained from ZenBio Inc. and under Duke IRB protocol 00000873. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were purified from healthy donor blood by Ficoll–Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. NK cells were then isolated from PBMC using a human NK Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. NK cells were then resuspended in NK cell expansion medium comprised of NK magnetic-activated cell sorting medium (NK MACS medium; Miltenyi Biotec) supplemented with 5% human AB Serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 30 ng/mL of recombinant human interleukin (IL)-15 (Miltenyi Biotec). Five days after culture, an additional NK cell expansion medium was supplemented, and cell numbers were counted. NK cell expansion medium was then added to the cell culture to maintain a cell concentration of 0.5 million cells/mL. Every 2–3 days, cell numbers were monitored, and the NK cell expansion medium was supplied so that the cell concentration was kept under 0.5 million cells/mL up until 17 days after culture initiation.

Single NK cell clones

NK cells were isolated from human PBMC by negative selection (human NK Cell Isolation Kit, Miltenyi Biotec). As feeder cells, we mixed fresh allogeneic PBMC and 8866 cell lines that are in an exponential proliferation phase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a PBMC:8866 cell ratio of 10:1 and irradiated with the dose of 60 Gy. NK cells and feeder cells were cocultured in a cloning medium consisting of RPMI-1680 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 1× minimum essential medium non-essential amino acids (MEM NEAA, Gibco), 1× sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 100 μg/mL kanamycin, 500 U/mL Roche recombinant human IL-2 (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (Fisher Scientific) and plated in 96-well plates so that 100 μL of culture in each well contained one NK cell. Fourteen days after culture, wells with proliferated NK cell clones (NKCL) were transferred to a 48-well plate, and additional cloning media were supplied every 2–3 days. The phenotype of NKCL was characterized by flow cytometry using the following antibodies: anti-CD3-AlexaFluor 700 (BD Pharmingen, clone SP34.2), anti-CD56-BV605 (BD Pharmingen, clone NCAM16.2), and anti-CD16-APC-Cy7 (BD Pharmingen, clone 3G8). To minimize the potential batch effects on mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) during our experiments, we also employed multiple mitigation strategies. We first purchased the antibodies in bulk in order to use a single lot of antibodies for the entire duration of this study. We also ensured the quality control of the BD FACS Symphony, including the use of calibration beads,32 daily to ascertain that the voltage, filter, and laser measurements were within consistent and acceptable values.

siRNA knockdown for CD3ζ

Expanded NK cells were pelleted and nucleofected with 5 µM Accell nontargeting siRNA #1 (Horizon Discovery) or 5 μM SMARTpool Accell CD3ζ siRNA (Horizon Discovery) using a P3 Nucleofection Kit (Lonza) and Amaxa 4D nucleofector (Lonza, pulse code CM137).33,34 Nucleofected cells were then cultured in an NK cell expansion medium. For NKCL, cells were incubated in NK MACS medium with 5% human AB serum, 500 U/mL recombinant human IL-2 (R&D Systems), and 1 ng/mL of recombinant human IL-15 (Miltenyi Biotec) following nucleofection. Two days after nucleofection, the efficiency of CD3ζ knockdown and the levels of FcRγ expression were analyzed via flow cytometry by the staining of the following surface and intracellular markers: anti-CD3-BV786 (BD Pharmingen, clone SP34.2), anti-CD14-BUV737 (BD Pharmingen, clone M5E2), anti-CD20-BUV395 (BD Pharmingen, clone L27), anti-CD56-BV605 (BD Pharmingen, clone NCAM16.2), anti-HLADR-APC-Cy7 (BD Pharmingen, clone G46-6), anti-CD16-BUV496 (BD Pharmingen, clone 3G8), anti-Fc receptor γ chain (FcRγ)—Alexa Fluor 700 (conjugated in our laboratory from anti-FcεRI antibody γ subunit, EMD Millipore, rabbit polyclonal), and anti-CD247 (CD3ζ)-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BioLegend, clone 6B10.2). A representative gating strategy is summarized in Supplementary Figure S3.

Calcein acetoxymethyl–based NK cell ADCC and killing assay

CEM.NKR.CCR5 cell lines (ATCC) were spinoculated with p24 90 ng of HIV-1 bronchoalveolar lavage (BaL, National Institutes of Health [NIH] AIDS reagent) per 2 × 105 cells at 1,200 g for 2 h; infected cells were cultured for 6 days in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 U/mL penicillin–streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (R10). One day prior to the killing assay, a fraction of BaL-infected cells was stained with anti-HIV core antigen-FITC (Beckman Coulter, clone KC57), and the percentage of HIV+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. We confirmed that >99% of CEM.NKR.CCR5 cells are CD4+, and, following spinoculation, we observed that 30%–60% of cells became BaL+ the day before the experiment. BaL-uninfected or BaL-infected cells were then stained with 10 μM calcein acetoxymethyl (CAM) (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37°C. Stained cells were washed twice and coated with 10 μg/mL human anti-HIV-1 envelope-specific antibody PGT121 or anti-human CD4 antibody (clone CD4R1)11 for 15 min at room temperature. Following the incubation, nontargeting siRNA or CD3ζ siRNA-nucleofected expanded NK cells or NKCL pool were cocultured to achieve a 10:1 Effector:Target (E:T) ratio in a total volume of 200 μL R10 per well. Four hours after coculture, supernatant from the culture was harvested and CAM signals were measured using Nivo plate readers (PerkinElmer). To measure spontaneous CAM release, target cells without NK cells were prepared. Four hours after coculture, cells were pelleted, and the supernatant was collected, and the levels of CAM release (excitation 480 nm, emission 535 nm) were quantified by Nivo Plate Reader (PerkinElmer). ΔCAM was calculated by subtracting fluorescence from the condition without NK cells. We confirmed that data from expanded NK cells and NKCL are comparable (data not shown), and both datapoints were plotted in the same figure as a separate symbol.

Annexin V-based NK cell ADCC and killing assay

CEM.NKR.CCR5 cell lines were stained with 50 nM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min. After staining, cells were incubated with anti-human CD4 antibody (clone CD4R1, NHP reagents) at room temperature for 15 min. Following antibody coating, nontargeting siRNA or CD3ζ siRNA-nucleofected expanded NK cells were added and cultured for 4 h. Following coculture, the cells were stained with anti-Annexin V-APC (BD Biosciences, clone), and the % Annexin V+CFSE+ cells were measured by flow cytometry. The %ADCC was calculated as follows: %ADCC = (%Annexin V+ cells with an antibody) − (%Annexin V+ cells without an antibody). For an HIV-1-specific antibody titration, BaL-infected CEM.NKR.CCR5 cell lines were treated with 5-fold serial dilution of human anti-HIV-1 env antibodies PGT121, VRC01, 10E8, and 35022 starting at 100 μg/mL. Cells were then incubated with primary human NK cells for 4 h, and %Annexin V+CFSE+ cells were measured by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software) was used to evaluate statistically significant differences. p-Values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to assess statistically significant differences for paired analyses.

Results and Discussion

To delineate the contribution of CD3ζ in NK cell ADCC, we aimed to establish a CD3ζ knockdown system in expanded primary human NK cells or NKCL using siRNA. We first investigated a transient CD3ζ knockdown approach using CD3ζ siRNA. Nucleofection of CD3ζ siRNA was able to reduce CD3ζ expression, whereas FcRγ expression was only minimally altered (Fig. 1A–C, p < .05). The levels of CD3ζ and FcRγ were not strongly correlated following CD3ζ knockdown, further supporting the specificity of this strategy (Supplementary Fig. S1). We also measured the levels of surface CD16 expression; while there was a statistically significant difference, the downregulation of CD16 expression was limited by CD3ζ knockdown (Fig. 1D). Altogether, we confirmed that CD3ζ knockdown by siRNA can specifically assess the contribution of CD3ζ in NK cell function with limited off-target effects.

FIG. 1.

CD3ζ knockdown specifically downregulates CD3ζ expression in primary human NK cells. Expanded primary human NK cells or pooled NKCL were nucleofected with scrambled siRNA (si-Ct) or CD3ζ siRNA and the levels of CD3ζ in live CD3− CD14−CD20−CD56+CD16+ cells were measured by flow cytometry, (A) the representative flow plots were shown (B, C, D) the boxplots for % CD3ζ+ live CD3−CD14−CD20−CD56+CD16+ cells (B), % FcRγ+ live CD3−CD14−CD20−CD56+CD16+ cells (C), and CD16 MFI for live CD3−CD14−CD20−CD56+CD16+ cells (D) were depicted. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to evaluate statistically significant differences. (n = 11, *: p < .05).

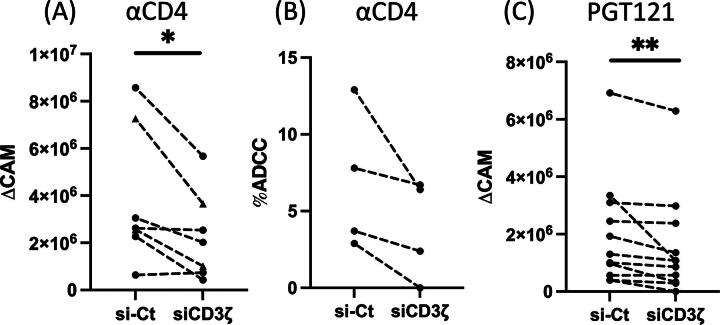

Using this siRNA knockdown strategy, we investigated whether CD3ζ reduction will impair NK cell ADCC responses. First, to evaluate the effect of CD3ζ knockdown on NK cell ADCC against abundantly expressed antigens, we used uninfected CEM.NKR-CCR5 cell lines35 as target cells and coated cells with anti-human CD4 antibody to elicit NK cell ADCC.11 We demonstrated that CD3ζ knockdown significantly decreases NK cell ADCC activity against target cells as measured by intracellular CAM release (Fig. 2A, p < .05). While it was not statistically significant, our Annexin V-based NK cell ADCC assay also revealed an analogous reduction of NK cell ADCC activities by CD3ζ knockdown (Fig. 2B). In summary, we illustrated that CD3ζ knockdown specifically perturbs NK cell ADCC against an antigen with high endogenous expression.

FIG. 2.

CD3ζ reduction diminishes HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC. Expanded primary human NK cells (triangle) or the mixed NKCL (circle) were nucleofected with scrambled siRNA (si-Ct) or CD3ζ siRNA for two days. Cells were then cocultured with BaL-uninfected CEM.NKR.CCR5 cells coated with anti-CD4 antibody (A, B) and BaL-infected CEM.NKR.CCR5 cells incubated with anti-HIV-1 envelope antibody PGT121 (C) for 4 h. Shown are datapoints for ΔCAM (A, C) and %ADCC (B) from respective donors. To assess statistically significant differences, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied. (A; n = 7, B; n = 4, C; n = 11, *: p < 0.05, **: p < .01). ADCC, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; CAM, calcein acetoxymethyl; NK, natural killer; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

In order to evaluate the impact of CD3ζ knockdown on HIV-1-specific ADCC, we next tested the potency of HIV-1-specific ADCC by HIV-1 BaL-infected CEM.NKR-CCR5 cells. First, we investigated which of the commonly used HIV-1-specific antibodies (PGT121, VRC01, 35022, and 10E8)36 elicited the most robust HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC at the optimal concentrations. Our ADCC assay elucidated that PGT121 triggered the most potent HIV-1-specific ADCC within the concentration of 5–20 μg/mL (Supplementary Fig. S2). Using PGT121, we next tested if the knockdown of CD3ζ abrogated HIV-1-specific ADCC.36 Consistent with Figure 2A, HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC was significantly diminished by loss of CD3ζ expression (Fig. 2C, p < .01). Taken together with our prior findings, these data illustrate that CD3ζ contributes to eliciting HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC.

Having developed a CD3ζ knockdown strategy in primary human NK cells using siRNA, we were able to confirm that CD3ζ siRNA does not significantly alter FcRγ expression. Using this technique, we illustrated that HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC was perturbed by decreasing CD3ζ expression. Our findings represent a critical addition to our understanding of NK cell biology, specifically for ADCC activity. Previous studies indicate the association between robust ADCC responses and CD3ζ levels in NK cells,11,23–26 but the importance of CD3ζ in ADCC has never been characterized by knockout/knockdown techniques. Our data support the argument that CD3ζ is a crucial molecule in harnessing NK cell ADCC by directly modulating CD3ζ expression.

While our findings provide novel insights into NK cell ADCC, we acknowledge that this study has several limitations. First, HIV-1-specific ADCC potency was limited in our experiments, presumably due to the antibody clones that were used in this study. Recently, it was demonstrated that the combination of neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 can further ameliorate HIV-1-specific ADCC responses.37 Therefore, the role of CD3ζ in HIV-1-specific NK cell ADCC can be validated in an in vitro system with the optimal combination of antibodies against HIV-1. Moreover, the roles of CD3ζ in NK cell ADCC were mostly demonstrated in vitro in this study. Thus, follow-up studies using samples from people living with HIV (PLWH) or NHP models are necessary to validate our findings ex vivo and in vivo.

Our presented data also provide a novel insight into which method can potentially be applied for NK cell immunotherapeutics. To date, numerous NK cell-based strategies, including chimeric-antigen receptor NK cells, bispecific killer engagers, or trispecific killer engagers, demonstrated their effectiveness against cancers and multiple pathogens.38–41 The potency of NK cell therapies is also increasingly appreciated in HIV-1 infection.41 These approaches are further augmented by gene editing strategies to enhance NK cell activities.42,43 Our results imply that the modulation of CD3ζ expression by siRNA knockdown or lentiviral transduction could be implemented as an additional tool to specifically augment NK cell-mediated ADCC in these strategies to kill HIV-1-infected cells more effectively. Altogether, we highlighted that NK cells prefer to utilize CD3ζ for inducing HIV-1 ADCC. These results can be translated to develop more potent NK cell ADCC for HIV-1 cure strategies and other disease treatments.

Authors’ Contributions

S.S., R.K.R., and S.J. conceptually developed the initial project, and S.S. performed a majority of experiments. E.L., M.A.C., A.P., S.B.G., and H.B. generated NKCL, and M.A.C. and A.P. helped the expansion of primary human NK cells. K.K. and C.M. developed the protocol for CEM.NKR-CCR5 cell line infection with BaL, prepared the laboratory stock of BaL, and performed HIV-1-specific antibody-titration experiments. Y.L. provided anti-HIV-1 Env antibodies. S.S. and G.W. drafted the article, and all the authors contributed to the final version.

Data Availability

The data generated for this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This research was supported by NIH grants: R01AI161010, R01AI136756, P01AI162242, and UM1AI164570 (to R.K.R.).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Mdluli T, Jian N, Slike B, et al. RV144 HIV-1 vaccination impacts post-infection antibody responses. PLoS Pathog 2020;16(12):e1009101; doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qi Y, Martin MP, Gao X, et al. KIR/HLA pleiotropism: Protection against both HIV and opportunistic infections. PLoS Pathog 2006;2(8):e79; doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vieillard V, Fausther-Bovendo H, Samri A, et al. Specific phenotypic and functional features of natural killer cells from HIV-infected long-term nonprogressors and HIV controllers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53(5):564–573; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d0c5b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahmad F, Hong HS, Jackel M, et al. High frequencies of polyfunctional CD8+ NK cells in chronic HIV-1 infection are associated with slower disease progression. J Virol 2014;88(21):12397–12408; doi: 10.1128/JVI.01420-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Woolley G, Mosher M, Kroll K, et al. Natural killer cells regulate acute SIV replication, dissemination, and inflammation, but do not impact independent transmission events. J Virol 2022;97(1):e0151922; doi: 10.1128/jvi.01519-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kroll KW, Shah SV, Lucar OA, et al. Mucosal-homing natural killer cells are associated with aging in persons living with HIV. Cell Rep Med 2022;3(10):100773; doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yates NL, Liao HX, Fong Y, et al. Vaccine-induced Env V1-V2 IgG3 correlates with lower HIV-1 infection risk and declines soon after vaccination. Sci Transl Med 2014;6(228):228ra39; doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hessell AJ, Hangartner L, Hunter M, et al. Fc receptor but not complement binding is important in antibody protection against HIV. Nature 2007;449(7158):101–104; doi: 10.1038/nature06106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michaelsen TE, Aase A, Norderhaug L, et al. Antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity induced by chimeric mouse-human IgG subclasses and IgG3 antibodies with altered hinge region. Mol Immunol 1992;29(3):319–326; doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90018-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lanier LL, Yu G, Phillips JH. Analysis of Fc gamma RIII (CD16) membrane expression and association with CD3 zeta and Fc epsilon RI-gamma by site-directed mutation. J Immunol 1991;146(5):1571–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah SV, Manickam C, Ram DR, et al. CMV primes functional alternative signaling in adaptive deltag NK cells but is subverted by lentivirus infection in rhesus macaques. Cell Rep 2018;25(10):2766–2774 e3; doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vivier E, Nunes JA, Vely F. Natural killer cell signaling pathways. Science 2004;306(5701):1517–1519; doi: 10.1126/science.1103478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwon HJ, Kim HS. Signaling for synergistic activation of natural killer cells. Immune Netw 2012;12(6):240–246; doi: 10.4110/in.2012.12.6.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Upshaw JL, Schoon RA, Dick CJ, et al. The isoforms of phospholipase C-gamma are differentially used by distinct human NK activating receptors. J Immunol 2005;175(1):213–218; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cella M, Fujikawa K, Tassi I, et al. Differential requirements for Vav proteins in DAP10- and ITAM-mediated NK cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med 2004;200(6):817–823; doi: 10.1084/jem.20031847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen X, Trivedi PP, Ge B, et al. Many NK cell receptors activate ERK2 and JNK1 to trigger microtubule organizing center and granule polarization and cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104(15):6329–6334; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611655104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, et al. LAT: The ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell 1998;92(1):83–92; doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80901-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ting AT, Karnitz LM, Schoon RA, et al. Fc gamma receptor activation induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of both phospholipase C (PLC)-gamma 1 and PLC-gamma 2 in natural killer cells. J Exp Med 1992;176(6):1751–1755; doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Billadeau DD, Brumbaugh KM, Dick CJ, et al. The Vav-Rac1 pathway in cytotoxic lymphocytes regulates the generation of cell-mediated killing. J Exp Med 1998;188(3):549–559; doi: 10.1084/jem.188.3.549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Watzl C, Long EO. Signal transduction during activation and inhibition of natural killer cells. Curr Protoc Immunol 2010;Chapter 11:Unit 11 9B; doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1109bs90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu LL, Landskron J, Ask EH, et al. Critical Role of CD2 Co-stimulation in adaptive natural killer cell responses revealed in NKG2C-deficient humans. Cell Rep 2016;15(5):1088–1099; doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Medjouel Khlifi H, Guia S, Vivier E, et al. Role of the ITAM-bearing receptors expressed by natural killer cells in cancer. Front Immunol 2022;13:898745; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.898745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee J, Zhang T, Hwang I, et al. Epigenetic modification and antibody-dependent expansion of memory-like NK cells in human cytomegalovirus-infected individuals. Immunity 2015;42(3):431–442; doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peppa D, Pedroza-Pacheco I, Pellegrino P, et al. Adaptive reconfiguration of natural killer cells in HIV-1 infection. Front Immunol 2018;9:474; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hwang I, Zhang T, Scott JM, et al. Identification of human NK cells that are deficient for signaling adaptor FcRγ and specialized for antibody-dependent immune functions. Int Immunol 2012;24(12):793–802; doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Suarez-Fueyo A, Bradley SJ, Katsuyama T, et al. Downregulation of CD3zeta in NK cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients confers a proinflammatory phenotype. J Immunol 2018;200(9):3077–3086; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang T, Scott JM, Hwang I, et al. Cutting edge: Antibody-dependent memory-like NK cells distinguished by FcRγ deficiency. J Immunol 2013;190(4):1402–1406; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee J, Chang WLW, Scott JM, et al. FcRγ-NK cell induction by specific cytomegalovirus and expansion by subclinical viral infections in rhesus macaques. J Immunol 2023;211(3):443–452; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2200380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou J, Amran FS, Kramski M, et al. An NK cell population lacking FcRγ is expanded in chronically infected HIV patients. J Immunol 2015;194(10):4688–4697; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tuyishime M, Spreng RL, Hueber B, et al. Multivariate analysis of FcR-mediated NK cell functions identifies unique clustering among humans and rhesus macaques. Front Immunol 2023;14:1260377; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1260377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu W, Scott JM, Langguth E, et al. FcRγ gene editing reprograms conventional NK cells to display key features of adaptive human NK cells. iScience 2020;23(11):101709; doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mizrahi O, Ish Shalom E, Baniyash M, et al. Quantitative flow cytometry: Concerns and recommendations in clinic and research. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2018;94(2):211–218; doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang RS, Lai MC, Shih HA, et al. A robust platform for expansion and genome editing of primary human natural killer cells. J Exp Med 2021;218(3); doi: 10.1084/jem.20201529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dahlvang JD, Dick JK, Sangala JA, et al. Ablation of SYK kinase from expanded primary human NK Cells via CRISPR/Cas9 enhances cytotoxicity and cytokine production. J Immunol 2023;210(8):1108–1122; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2200488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tremblay-McLean A, Coenraads S, Kiani Z, et al. Expression of ligands for activating natural killer cell receptors on cell lines commonly used to assess natural killer cell function. BMC Immunol 2019;20(1):8; doi: 10.1186/s12865-018-0272-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stephenson KE, Julg B, Tan CS, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity of PGT121, a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody against HIV-1: A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 clinical trial. Nat Med 2021;27(10):1718–1724; doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01509-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tuyishime M, Garrido C, Jha S, et al. Improved killing of HIV-infected cells using three neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies. J Clin Invest 2020;130(10):5157–5170; doi: 10.1172/JCI135557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P, et al. Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N Engl J Med 2020;382(6):545–553; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Felices M, Lenvik TR, Davis ZB, et al. Generation of BiKEs and TriKEs to improve NK cell-mediated targeting of tumor cells. Methods Mol Biol 2016;1441:333–346; doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3684-7_28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vallera DA, Felices M, McElmurry R, et al. IL15 trispecific killer engagers (TriKE) make natural killer cells specific to CD33+ targets while also inducing persistence, In Vivo expansion, and enhanced function. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22(14):3440–3450; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bardhi A, Wu Y, Chen W, et al. Potent in vivo NK cell-mediated elimination of HIV-1-infected cells mobilized by a gp120-bispecific and hexavalent broadly neutralizing fusion protein. J Virol 2017;91(20); doi: 10.1128/JVI.00937-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pomeroy EJ, Hunzeker JT, Kluesner MG, et al. A genetically engineered primary human natural killer cell platform for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Ther 2020;28(1):52–63; doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gurney M, Stikvoort A, Nolan E, et al. CD38 knockout natural killer cells expressing an affinity optimized CD38 chimeric antigen receptor successfully target acute myeloid leukemia with reduced effector cell fratricide. Haematologica 2022;107(2):437–445; doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.271908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated for this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.