Abstract

Significance:

Oxidative stress (OS) and inflammation are inducers of tissue injury. Alternative splicing (AS) is an essential regulatory step for diversifying the eukaryotic proteome. Human diseases link AS to OS; however, the underlying mechanisms must be better understood.

Recent Advances:

Genome‑wide profiling studies identify new differentially expressed genes induced by OS-dependent ischemia/reperfusion injury. Overexpression of RNA-binding protein RBFOX1 protects against inflammation. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α directs polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 to regulate mouse carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (Ceacam1) AS under OS conditions. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L variant 1 contains an RGG/RG motif that coordinates with transcription factors to influence human CEACAM1 AS. Hypoxia intervention involving short interfering RNAs directed to long-noncoding RNA 260 polarizes M2 macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype and alleviates OS by inhibiting IL-28RA gene AS.

Critical Issues:

Protective mechanisms that eliminate reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important for resolving imbalances that lead to chronic inflammation. Defects in AS can cause ROS generation, cell death regulation, and the activation of innate and adaptive immune factors. We propose that AS pathways link redox regulation to the activation or suppression of the inflammatory response during cellular stress.

Future Directions:

Emergent studies using molecule-mediated RNA splicing are being conducted to exploit the immunogenicity of AS protein products. Deciphering the mechanisms that connect misspliced OS and pathologies should remain a priority. Controlled release of RNA directly into cells with clinical applications is needed as the demand for innovative nucleic acid delivery systems continues to be demonstrated.

Keywords: alternative splicing, CEACAM1, exons, ischemia/reperfusion injury, RNA-binding proteins, spliceosome

Introduction

The continuity of all living cells depends on the integrity of genetic information that allows for the synthesis of macromolecules such as proteins and RNAs, which are crucial for the physiological functions of life. Nuclear genes consist of both coding (exons) and noncoding (introns) sequences that are removed by RNA splicing (Marasco and Kornblihtt, 2023), a biochemical process that leads to the assembly of the spliceosome, ligation of the interrupted exons, and the subsequent maturation of messenger RNA (mRNA).

The processing of RNA transcripts includes five recognized processes: (i) capping (in which the 5′ triphosphate of the pre-mRNA is cleaved, and a guanosine monophosphate is added and subsequently methylated to produce m7GpppN), (ii) editing (in which individual RNA residues are converted to alternative bases, e.g., adenosine is converted to inosine by base deamination to produce mRNAs encoding different protein products), (iii) splicing (in which intervening sequences are removed, and the spliceosome ligates exons together), (iv) 3′ end formation, which involves pre-mRNA synthesis and cleavage of the poly (A) tail, and (v) degradation. Eukaryotic genes, organized as a mosaic of exons, give rise to differential splice-site (ss) selection or alternative splicing (AS).

Although the role of AS in boosting transcript diversity has been recently investigated in cancer (Han et al., 2022), tissue identity (Louadi et al., 2021), cell development (Öther-Gee Pohl and Myant, 2022), skeletal muscle during exposure to microgravity (Henrich et al., 2022), and autoimmunity (Phillips, 2022), its coordinating role in resolving oxidative stress (OS), especially in ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI), has not been appreciated. Metabolic and oxidative disturbances during surgical procedures increase a patient's exposure to multifaceted inflammatory immune responses involving direct and indirect cytotoxic mechanisms in a process known as tissue IRI (Castillo et al., 2022), an area of our laboratory's interest. Importantly, no definitive therapies exist for the prevention of IRI. Many studies have shown promising results but are mostly restricted to preclinical phases.

A rational approach to prevent IRI may be to consider new therapeutic modalities that focus on the combinatorial role of AS cellular and molecular activation pathways in the regulation of local immune and inflammatory cascades (Dery and Kupiec-Weglinski, 2022). Although many reviews have investigated the mechanisms of AS and RNA splicing (Gordon et al., 2021; Shenasa and Hertel, 2019; Ule and Blencowe, 2019), in this study, we compile the most recent basic and clinical studies, including our own (Dery et al., 2023a), linking AS functionality to stress-triggered biochemical inducers of OS, with a discussion on novel splicing-correcting therapies in the clinical setting.

Historical Background

The discovery of RNA splicing, initially described in the 1970s, overturned years of thought in the field. Before groundbreaking studies that showed how RNA is processed at the 5′ terminus of adenovirus 2 late mRNA (Berget et al., 1977), the consensus was that all organisms contained the same gene structure as bacteria. After all, it was the work of the 1965 recipient of the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, just two decades earlier, by the French biochemist Jacques Monod, along with others, which showed that the structure of a bacterial gene is made up of three distinct units: (i) the regulatory region or promoter, (ii) the open reading frame (ORF) or coding region, and (iii) the terminator sequence. The prevailing view that all the significant discoveries of the gene were solved was best summarized by Monod's famous assertion that anything true for Escherichia coli must also be true for elephants (Friedmann, 2004; Suran, 2020).

The recognition that multicelled animal genes are intervened by noncoding DNA introns between expressed exon sequences revolutionized our understanding of the eukaryotic gene structure; it was, in fact, far more complex than bacteria. Some introns stretch up to 100 kb (100,000 bp) in length (Hong et al., 2006) between exons that are mostly short (<200 bp in size). It also raised new questions about introns and exons' origins, stability, and adaptive significance. For example, while the primordial photosynthetic cyanobacterium Fischerella has introns, few single-celled eukaryotes have introns, suggesting an evolutionary loss that occurred during speciation (Barinaga, 1990). The re-emergence of spliceosomal introns in multicelled animals and plants is not only surprising but also debunks the dogma that one gene produces one mRNA, and all mRNAs from a gene produce one protein (Edgell et al., 2000; Suran, 2020).

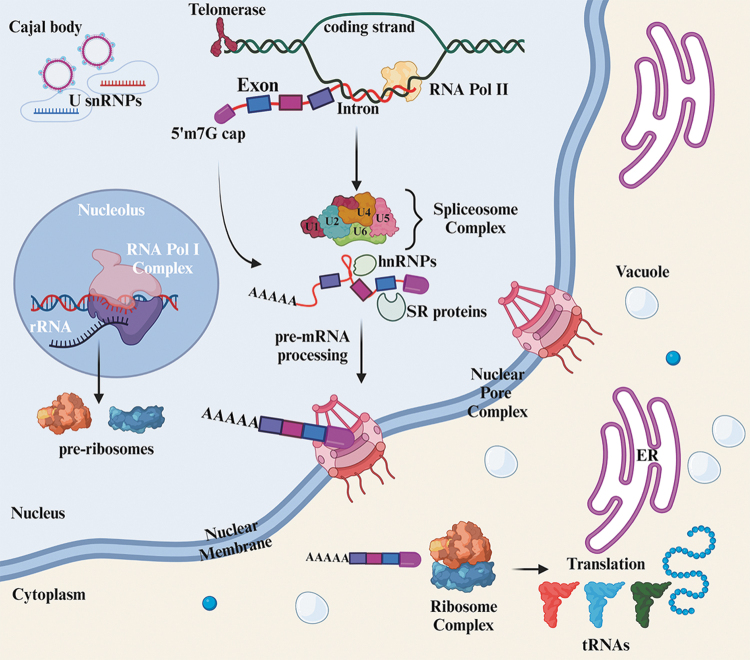

Intron discovery also led to the search for a biochemical mechanism that would bring continuity back to the split nature of genes. It is now well appreciated that the process of RNA splicing (also called constitutive splicing) occurs through the de novo assembly of the large multiprotein/RNA complex, called the spliceosome (Fig. 1). The core of this multi-megadalton RNA–protein complex consists of a complement of smaller nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle complexes called snRNPs whose job it is to mark specific nucleotides for processing. For example, while the 5′ss defines the proximal exon/intron boundary's boundary and is recognized by the U1 snRNP, the branch point (BP) sequence is recognized by the U2 snRNP. Many hundreds of proteins and small nuclear RNAs associate with the spliceosome to provide a molecular scaffold that gives it its shape and guides the precursor mRNA to execute intron removal (Ule and Blencowe, 2019).

FIG. 1.

The spliceosome is a macromolecular complex that assembles de novo on pre-mRNAs during a critical step in gene expression called RNA splicing. Cotranscriptional splicing occurs when RNA pol II unwinds the DNA helix and initiates RNA transcription on the template strand. Concurrently, the assembly of U-rich snRNPs forms the spliceosome, a macromolecular complex of proteins and RNA. Following post-transcriptional modifications, including the addition of an m7G cap and poly-A tail, the exons (colored boxes) and introns (red line) encoded in the nascent RNA (now called precursor-mRNA) are processed by the spliceosome at the 5′ss and 3′ss. In the cytoplasm, ribosome complexes direct the translation of mRNA into protein macromolecules via charged transfer (t)-RNAs displaying corresponding amino acids. Protein translocation to the ER facilitates further protein modifications. Telomerase provides genomic stability to highly proliferative normal and tumor cells. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; m7G, 7-methylguanosine; mRNA, messenger RNA; snRNP, smaller nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle; ss, splice site.

Although the ribosome has a diameter size of 3.6-angstrom in some eukaryotic cells (Yan et al., 2015), the transient nature of the spliceosome has made it a challenging target for structure-function analyses. Unlike the static megadalton ribosome (Cabej, 2013), the spliceosome continually assembles de novo on each intron stepwise, making capture by biochemical means at any time point potentially artificial. Currently, the focus of the AS field is to understand how spliceosomes achieve the high fidelity necessary to ensure proper processing of pre-mRNAs while maintaining flexibility to allow for AS-site choice during times of stress, inflammation, or cancer (Chen and Moore, 2015).

AS Events Enhance Transcript Diversification

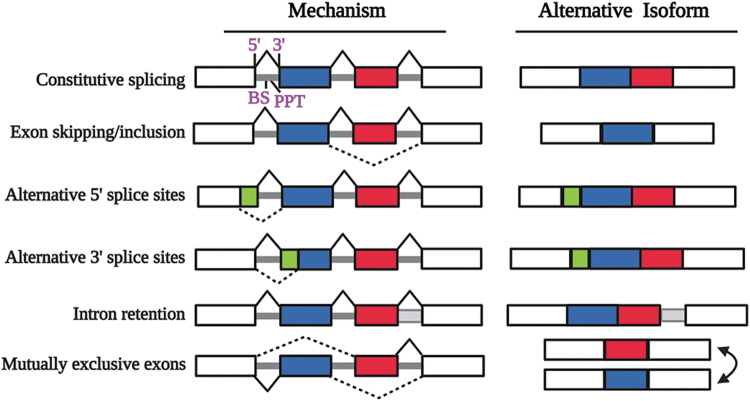

High-throughput sequencing studies have revealed that ∼95% of human genes are subjected to RNA splicing modulation (Chen and Moore, 2015). Recent studies suggest that 38% of the human genome comprises noncoding intronic sequences, while only 3% is devoted to exonic (Zhang et al., 2022). The basic mechanisms of AS are detailed in Figure 2 and include the following: (i) exon skipping/inclusion, (ii) alternative 5′ss, (iii) alternative 3′ss, (iv) intron retention, (v) mutually exclusive exons, and (vi) alternative polyadenylation (Bhadra et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022). Exon skipping/inclusion occurs prevalently, whereas intron retention is the least common type. Some factors that control the precision and diversity of AS include chromatin modifications, RNA secondary architectures, and the strength or weakness of the splice sites.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of types of AS. Constitutive splicing (as well as for alternative isoforms) depends on four basal splice signals (shown in purple) to initiate spliceosome activity: (i) the 5′ss (CAG/GTRAGT); (ii) BS (YTAY); (iii) PPT (Y rich); and the 3′ss (NCAG/G). Boxes represent exons, solid lines are the introns, Y is the pyrimidine, and the / symbol defines the exon–intron boundary. Other major AS events are depicted (the constitutive product is not shown for simplicity). AS, alternative splicing; BS, branch site; PPT, polypyrimidine tract. Created with Biorender.com

The concentration and localization of enhancing and silencing splicing factors are also essential. When they occur within snRNPs, necessary for AS assembly and activity, they become localized at the border between speckles and the adjacent chromatin domains (Girard et al., 2012; Hall et al., 2006). Speckles contain little DNA and function as storage compartments for splicing factors. Indeed, snRNPs terminally associate with the carboxyterminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II at sites of active transcription where spliceosomes assemble, although the precise mechanism of how they translocate from the speckle to the CTD remains a mystery.

AS represents a major source of phenotypic innovation across eukaryotic lineages, including metazoans (Kim et al., 2007), fungi (Grützmann et al., 2014), and plants (Zhang et al., 2015). In some insect populations, mutations accumulate in their splice sites (altering their AS developmental programs), causing differential methylation patterns to produce alternative social grouping systems between workers and their queens (Lyko et al., 2010). Human body lice are thought to have emerged from human head lice that adapted to the widespread use of clothing (Bush et al., 2017), and in the case of two mice subspecies, their divergence about half a million years ago is attributed to their different AS profiles (Harr and Turner, 2010). These examples help to explain how different morphs arise in the same species and lead to adaptive radiation and speciation events.

Several studies have shown that the source of transcript diversification comes from intronic recombination, similar to how gene duplication arose in metazoans (Bush et al., 2017). Three possible mechanisms are attributed to the origins of AS and include exon shuffling, exonization of transposed elements, and constitutively spliced exons (Kim et al., 2008). In exon shuffling, new exons are inserted into existing genes (by insertion or duplication), or a process of nonhomologous recombination can bring two or more exons from different genes together to produce new exon–intron structures (Patthy, 2021). Studies show that exon shuffling may play a significant role in the rapid evolution of eukaryotic genes (Letunic et al., 2002). Exonization of transposed elements arises from the insertion of primate-specific moveable Alu elements.

They are the most repetitive elements in the human genome, with millions of copies accounting for more than 10% of the genome (Batzer and Deininger, 2002; Lander et al., 2001). The frequency of new retrotransposition events occurs between every 20 and 125 births (Cordaux et al., 2006), accounting for ∼1% of Mendelian genetic disorders (Deininger and Batzer, 1999).

OS Influences AS Pathways

In addition to Alu elements' role in evolutionary diversity, its excessive transcription products can lead to abnormal regulation, manifesting as a source of many genetic diseases. For example, the Human Genetic Mutation Database identifies the involvement of Alu elements in neurofibromatosis (Wallace et al., 1991), leukemia (Komkov et al., 2012), Alzheimer's disease (Wu et al., 2013), and breast cancer (Fazza et al., 2009). These diseases share another common feature besides the interplay of Alu elements: the etiology caused by damage from OS. Broadly speaking, OS widely occurs in biological systems and involves the imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants in favor of the oxidants, potentially leading to tissue damage (Sies, 1997).

Free radicals and oxidants are generated as by-products of catabolic metabolism and adenosine triphosphate production pathways in mitochondria (Pham-Huy et al., 2008). When they cannot be gradually destroyed, their accumulation generates OS, which activates intracellular stress signaling pathways that modulate gene expression and lead to chronic inflammation.

The role of AS in OS was recently investigated in a mouse model of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury and ischemia/reperfusion (IR). Lin et al. (2022) performed a genome‑wide profiling analysis and identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that showed enrichment in inflammatory response pathways, including hub genes CSF‑1, CXCL1, CXCL10, IL‑1β, IL‑34, IL‑6, and TLR2. The phosphorylation pathway showed changes in the regulated AS genes, CSNK1A1, PAK2, CRK, ADK, and IKBKB. Moreover, apoptosis and proliferation pathways involved in IR significantly induced AS pathways. Further search for an RNA-binding protein (RBP) led to the identification of RNA-binding fox‑1 homolog 1 (RBFOX1), a splicing regulator that primarily mediates it function through its RNA-binding domains. It is expressed exclusively in neurons, heart, and muscle and as a result influences synaptic function, neuronal excitability, and maturation (Wamsley et al., 2018).

Genetic studies in patients with autism have revealed chromosomal translocations affecting RBFOX1 (Prashad and Gopal, 2021). Lin et al. (2022) showed that RBFOX1 mRNA/protein in the nuclei of mouse renal tubules was downregulated by cisplatin and IR. In vitro experiments using HK‑2 cells derived from human renal proximal tubular epithelia showed that hypoxia/reperfusion blocked the nuclear localization of RBFOX1, likely disrupting its ability to recognize its cognate mRNA element and regulate spliceosome activity. Ectopic RBFOX1 inhibited superoxide dismutase, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) while promoting the activation of the NRF2/heme oxygenase 1 (HO‑1) signaling axis (Fig. 3, blue lines). The precise mechanism by which RBFOX1 overexpression synergizes with HO-1 remains unclear.

FIG. 3.

AS regulation requires the recruitment of RBPs, for example, RBFOX1, to reduce inflammation-dependent OS from cisplatin and IR-induced AKI. Hypoxia/reperfusion restricts nuclear localization of RBPFOX1 (left side) and concurrently blocks the expression of NRF2/HO-1 signaling pathways (right side), activates the expression of NF-κB, proinflammatory signaling cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β), ROS production, and superoxide dismutase activity to stimulate apoptosis (red lines). Ectopic overexpression of RBFOX1 protects against inflammation and OS in hypoxia/reperfusion-induced HK-2 cells by repressing and activating NF-κB and NRF2/HO-1 pathways, respectively (blue lines). Question marks indicate possible mechanisms that remain undefined (see main text for details). AKI, acute kidney injury; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; IL, interleukin; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; OS, oxidative stress; RBFOX1, RNA-binding protein, fox-1 homolog 1; RBP, RNA-binding protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha. Adapted from Lin et al. (2022). Created with Biorender.com

Still, the recent findings that the RBP, human antigen R (HuR), regulates HO-1 cytoprotection in a human liver transplant injury model provide a clue (Dery et al., 2020). HuR can alter the cellular response to stress, inflammatory, and immune stimuli (Srikantan and Gorospe, 2012). Similarly, future studies would benefit from understanding how RBFOX1 promotes the expression of DEGs. Does the failure to induce AS cause the deregulation of scaffolding proteins necessary for spliceosome assembly to generate free radicals, thereby autoregulating its expression?

A variation of this theme was recently demonstrated when the functional role of U2AF1, a spliceosome factor essential for the catalysis of pre-mRNA splicing, was investigated (Liu et al., 2021a). They showed that U2AF1 expressed in mouse bone marrow stromal OP9 cells caused mitochondrial dysfunction and increased the generation of hydrogen peroxide, thereby promoting the production of cytokines/chemokines. Another group approached how OS affects AS by investigating the role of Fas cell surface death receptor regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), the master regulator of the hypoxic transcriptional response (Peciuliene et al., 2022). Short-term hypoxia (2 h) induced the expression of genes involved in oxidative and proteotoxic stress (e.g., ANGPL4, SRPY1, HSP70, ZNF54, and Hsp10). Longer term (24 h) exposure to hypoxia triggered cell response mechanisms involving genes associated with glycogen synthesis (protein phosphatase 1) or in the negative control of cell growth and division (protein phosphatase 2).

The role of HIF-1α in the characterization of hypoxic injury was further established in a model of ischemic heart disease, with differential splicing in calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma (CAMK2G) isoforms and Rbfox1 in postmyocardial infarction (MI) treatment groups (Williams et al., 2021). CaMK2, a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase, is a key transducer of calcium signaling in physiological and pathological settings.

Our group recently extended these findings when we demonstrated by luciferase and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays that Hif-1α controls the AS of mouse carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (Ceacam1) through direct interactions with the promoter region of polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 (Ptbp1) under OS conditions (Dery et al., 2023a). CEACAM1 is a pleiotropic transmembrane glycoprotein that differentially regulates epithelial, endothelial, and immune cells depending on two cytoplasmic splice variant domains. The inclusion of the variable exon 7 generates the long cytoplasmic tail, CEACAM1-L, comprising ∼70+ residues in length and produces inhibitory signaling in myeloid and lymphocytic cells (Kim et al., 2019). In contrast, excluding the variable exon 7 induces exon skipping to make the short cytoplasmic tail isoform, CEACAM1-S, comprising 12 amino acids. It is generally associated with epithelial cells and regulates mucosal immunity (Nagaishi et al., 2008).

Our group recently reported that hepatic CEACAM1 plays a role in orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) in mice and humans (Nakamura et al., 2020). The novelty of our recent study was to use the small-molecule prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG) to stabilize Hif-1α under normoxia conditions (Dery et al., 2023a). We showed that administration of DMOG shortly before acute liver injury induced the AS expression of Ceacam1-S, which improved liver function and reduced IRI. In the clinical arm, CEACAM1-S:HIF-1A mRNA expression in donor livers before transplant correlated with improved liver function and recipient transplant outcomes. These results suggest that CEACAM1-S may be a potential marker of liver quality and that efforts to increase its expression may have therapeutic benefits for transplantation or acute liver injury (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Hif-1α interaction with RNA splicing factor Ptbp1 regulates the AS of mouse Ceacam1. PHD proteins, as oxygen sensors, release their inhibition of HIF-1α during OS conditions. This frees HIF-1α to dimerize with constitutively expressed HIF-1β in the nucleus. Their transcriptional activation binds to the promoter structure of Ptbp1 to increase its expression. The splicing regulation by Ptbp1 enables fine-tuning interactions that increase the expression of Ceacam1-S and lead to ischemia tolerance in liver transplantation. Ceacam1, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1; Hif-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; Ptbp1, polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1. Adapted from Dery et al. (2023a). Created with Biorender.com

Finally, Gárate-Rascón et al. (2021) addressed how the splicing factor SLU7 may link stress-protective mechanisms with liver disease. Hepatic function resulting from damage responses has been analyzed in Slu7 haploinsufficient mice exposed to chronic (CCl4) versus acute (acetaminophen) liver injury (Gárate-Rascón et al., 2021). The authors used mass spectrometry of human and diseased mouse livers to identify hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α1) regulation by SLU7. Specifically, HNF4α1 stability and function directly depend on the capacity of SLU7 to protect the liver against OS. SLU7 has been identified as a critical component of the stress granule proteome, making it an essential element in the cell's antioxidant machinery. A representative selection of genes that may regulate AS in OS are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative Studies Involving Alternative Splicing and Oxidative Stress (2020-Present)

| Year | Model | Gene | Novelty | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | U2OS, A549, and Cos7 cells | STK11 | The LKB1 isoform, mLKB1, regulates mitochondrial metabolic activity through the histological colocalization of mLKB1 with mitochondria-resident ATP synthase and NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-3, which is upregulated by OS. | Tan et al. (2023) |

| 2023 | Prostate cancer cell lines (RWPE1, 22Rv1, DU145, PC3) | HMGA2 | Truncated HMGA2 cells display elevated levels of HMGA2, which is associated with higher OS and can be sensitive to ferroptosis a treatment for prostate cancer patients who overexpress HMGA2. | Campbell et al. (2023) |

| 2023 | Mice intestines | RBM47 | RBM47 regulates antioxidant and Wnt signaling pathways, intrinsically modifying intestine growth, inflammatory and tumorigenic pathways through AS of the mRNA encoding Tjp1/Zo1. | Soleymanjahi et al. (2023) |

| 2022 | Macrophage | IFNLR1 | lncRNA260 siRNA promotes hypoxia-dependent M2 polarization by reducing IL-28RAV2 AS variant. | Yang et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | Mouse cochleae | SQSTM1 | HEI-OC-1 cells showed higher expression in full-length p62 reduced ROS caused by H2O2. Different full-length to spliced variant ratios in p62 may be a new target to reduce the level of OS closely related to age-related hearing loss and noise-induced hearing loss in the cochleae. | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 2022 | Mouse kidney tissue | RBFOX1 | RBFOX1 reduced hypoxia/reoxygenation‑induced apoptosis of HK‑2 cells by inhibiting inflammation and OS. | Lin et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | Mouse neural cells | SRSF2 | Increased SRSF2 and decreased SRSF1 cause Pnn deficiency, increasing OS in neurons. | Hsu et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | Human fibroblasts | Sp1 | Sp1 depletion induced senescence with OS and suppressed the expression of downstream spliceosomal genes. | Kwon et al. (2021) |

| 2022 | Tibetan sheep ovaries | LYVE1 and ADAMTS-1 | High-altitude stress modulated differentially AS events by suppressing skipped exon events and increasing retained intron events, leading to the repression of ovarian development. | Li et al. (2022c) |

| 2022 | Mouse fibroblasts (3T3-L1) | PRKCD | GSK3ß with the RBP complex of lncRNA NEAT1 and SFRS10 enables fine-tuning of PKCδI expression during adipogenesis. | Bader et al. (2020) |

| 2021 | Bone marrow stromal cells | U2AF1 mutant (U2AF1S34F) | Differential AS events induced by mutant U2AF1 cause OS in bone marrow stromal cells and can lead to DNA damage and genomic instability in hematopoietic cells. | Liu et al. (2021a) |

| 2021 | Cystic fibrosis | Genome-wide RNAi screen | Identified novel modifier genes involved in OS susceptibility in cystic fibrosis | Checa et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | NR gene superfamily | Nuclear receptor genes | The differential expression profiles of splice-sensitive cassette exon domains may augment cellular resilience to OS. | Annalora et al. (2020) |

| 2021 | Mouse hepatocytes | SLU7 | Reduced expression of SLU7 in human and mouse diseased livers correlated with a switch from HNF4α P1 usage to P2 usage, which enhanced OS and impairment of hepatic functions. | Gárate-Rascón et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | Human and mouse breast cancer | MBD2 | MBD2 AS is suppressed under hypoxic conditions, favoring MBD2a production through the activation of HIF-1 and repression of SRSF2-mediated AS. MBD2a production facilitates breast cancer metastasis. | Liu et al. (2021b) |

| 2020 | Human retinal pigment epithelium | Epithelium cells treated with A2E | Found 10 different clusters of pathways involving differentially AS genes and highlighted subpathways determined by the induction of OS. | Donato et al. (2020) |

| 2020 | U251 and HeLa cells | PKM | PKM2 is upregulated in most cancer types, and the inactive form of PKM2 leads to cancer metabolism. PKM2 formed a tetramer without an allosteric activator and escaped inhibitory effects by OS. | Masaki et al. (2020) |

| 2020 | HeLa cells | XBP1 | PLD binds to eEf1A2 and triggers OS, causing a rapid apoptotic program in tumor cells. PLD activates a stress-induced unfolded protein response in the endoplasmic reticulum, including the AS of XBP1. | Losada et al. (2020) |

AS, alternative splicing; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; HIF-1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1; HNF4α, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4; IL, interleukin; IL-28RA, IL-28 receptor α; lncRNA260, long-noncoding RNA 260; mLKB1, mitochondria-localized LKB1; mRNA, messenger RNA; OS, oxidative stress; PLD, plitidepsin; RBFOX1, RNA-binding protein, fox-1 homolog 1; RBP, RNA-binding protein; RNAi, RNA interference; ROS, reactive oxygen species; siRNA, short interfering RNA; SRSF, serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor; Tjp1, tight junction protein 1.

These studies demonstrate how AS is a biological response to OS, orchestrated through multiple mechanisms, and, ultimately, how coordination dictates cellular fate.

RGG/RG Motif Proteins Coordinate AS During Inflammatory Processes

The class of RBPs discussed thus far has well-characterized sequence modules, including RNA-recognition motifs, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) K-homology domains, and zinc fingers. Such RNA-binding domains (RBDs) facilitate protein-RNA interactions by forming tertiary structures using specific amino acid sequences to interact with the phosphodiester backbone of pre-mRNA ligands (Lunde et al., 2007). Another class of RBPs contains short motif arginine–glycine-rich (RGG/RG) domains interspersed at variable lengths within the primary protein structure (Gary and Clarke, 1998). RGG/RG domains are widely disseminated throughout eukaryotic genomes (Järvelin et al., 2016), making them the second-most common RBD in the human genome (Fornerod, 2012; Thandapani et al., 2013). Despite this, far less is known about the RGG/RG domains. They are common among RBPs, including hnRNP L (Dery et al., 2018), hnRNP D (Hillebrand et al., 2017), and hnRNP A1 (Mayeda et al., 1998).

Intriguingly, Gly-rich sequences form intrinsically unstructured domains in solution but adopt an active configuration when interacting with other proteins or RNA (Rogelj et al., 2011). Unstructured domains arise from a strong amino acid compositional bias, rich in hydrophilic charged residues that lack bulky hydrophobic residues. This property of not being able to form a hydrophobic core prevents the formation of a stable three-dimensional fold. The transient conformational variability of proteins with RGG/RG domains allows them to participate in multiple biological processes and facilitate combinatorial regulation.

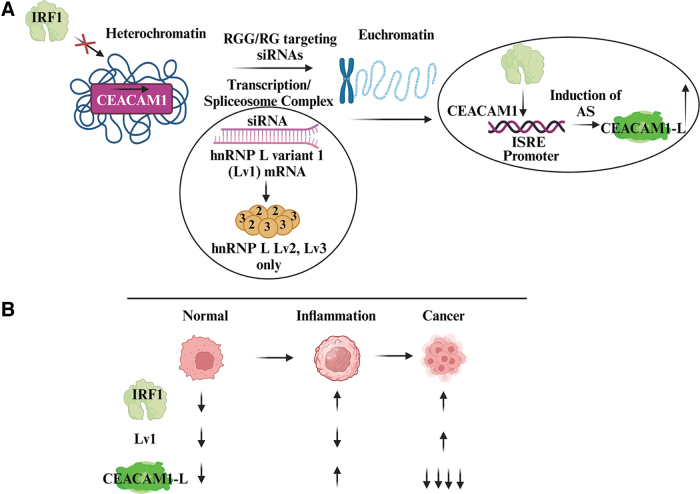

Our earlier studies uncovering the mechanism of AS in CEACAM1 led to our interest in RGG/RG domains (Dery et al., 2011). RNA affinity chromatography was used to identify the trans-acting factors involved in human CEACAM1 AS (Dery et al., 2011). We showed that two members of the hnRNP family, hnRNP L and hnRNP A1, interact with the variable exon 7 to induce exon skipping to promote the formation of the CEACAM1-S splicing variant. Our subsequent study characterized how interferon response factor 1 (IRF1) regulates CEACAM1 AS in breast cancer cells to generate the CEACAM1-L isoform (Dery et al., 2014). Having shown how hnRNP L and IRF1 cause CEACAM1-S and CEACAM1-L generation, we investigated whether IRF1 guides AS through hnRNP L-directed RNA splicing (Dery et al., 2018).

CEACAM1 gene expression dynamics was analyzed using short interfering RNA (siRNA) directed to hnRNP L variant 1 (Lv1) in the presence or absence of IRF1 in HeLa cervical cancer cells (Fig. 5A). The synergistic interaction of IRF1 (a transcription factor) and Lv1 (an RNA splicing factor) led to the unexpected euchromatization of DNA, effectively exposing promoter structures in the loosened chromatin allowing initiation of transcription and AS to overproduce CEACAM1-L in cancer cells. These studies demonstrate how RGG/RG proteins coordinate with cellular factors to control the cell's response to changes in the chromatin landscape and, ultimately, AS. The role Lv1 plays in inflammation and cancer is summarized in Figure 5B.

FIG. 5.

RBP hnRNP L and DNA transcription factor IRF1 synergize to coordinate CEACAM1 silencing. (A) RNA interference studies of RGG/RG containing hnRNP Lv1 opened the chromatin structure when IRF1 was present. Depleting the pool of available Lv1 in the transcription/spliceosome complex, leaving only variants 2 and 3 (Lv2, Lv3), had the remarkable ability to allow IRF1 access to CEACAM1 promoter structures leading to the cotranscriptional regulation and overexpression of CEACAM1-L. (B) Summary interactions between IRF1, Lv1, and CEACAM1-L. During normal cellular conditions, CEACAM1-S is favored. During inflammatory conditions, IRF1 controls the expression of CEACAM1-L. During cancer, Lv1 is expressed at higher levels, and in the presence of IRF1, this causes epigenetic changes in chromatin and coordinate silencing of CEACAM1-L. hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; IRF1, interferon response factor 1; Lv1, L variant 1. Adapted from Dery et al. (2018). Created with Biorender.com

Another recent contribution to how intrinsically disordered RGG/RG-rich motifs modulate spliceosome assembly has been reported (de Vries et al., 2022). This study demonstrated that the interaction between U1 and U2 snRNP, essential for the assembly of early spliceosomal complexes, depends on the positively charged carboxyl-terminal tail of SF3A1, a core component of the U2 particle, and binding to U1-SL4, a core component of the U1 particle. Crystallographic studies have shown that the structure of the SF3A1-UBL/U1-SL4 complex plays a role in AS regulation, although the exact mechanism remains unclear. The authors hypothesized that arginine methyltransferases targeting the RGG/RG domain of SF3A1 compete with PTBP1 and other RNA splicing factors for U1-SL4; however, more studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Intrinsically disordered RGG/RG domains also play an essential role in human diseases such as cancer, muscular atrophy, and neurodegenerative disorders (Chowdhury and Jin, 2022). Recently, the RGG/RG domain of RNA binding motif protein X-linked (RBMX) was investigated in X-linked intellectual disability Shashi-type neural progenitor cells (Cai et al., 2021). Previously, a 23-bp frameshift deletion in RBMX was causally associated with Shashi-XLID (Shashi et al., 2015). Cai et al. (2021) showed that the p53 pathway is dysregulated in RBMX-deficient cells, and they attributed this to protein arginine methyltransferase 5 targeting the RGG/RG domain. Furthermore, the inability to target serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) dysregulates RNA splicing of MDM4 pre-mRNA, resulting in the activation of the p53 pathway.

Another recent study investigated the role of G-rich sequence factor 1 (GRSF1), an RBP with G-rich elements, in a model of sepsis (Qi et al., 2021), which stems from an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants and has been identified as one of the most important causes of death in intensive care units (Mantzarlis et al., 2017). Some of the consequences of sepsis include impaired vascular permeability, decreased cardiac performance, and mitochondrial malfunction. Qi et al. (2021) hypothesized that GRSF1 may play a role in evaluating the severity and prognosis of sepsis. GRSF1 is known to participate in essential cellular processes such as senescence (Noh et al., 2018), regulation of mitochondrial function (Antonicka et al., 2013), and proinflammatory interleukin (IL)-6 (Noh et al., 2019), which are associated with sepsis deterioration.

Using experimental mouse models of cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis, in parallel with peripheral blood from 42 septic human subjects versus 32 healthy controls, the authors show that the expression of GRSF1 correlates with high mortality in septic mice and human patients. Finally, a recent study of MALT1 implicated the role of RGG/RG domains in mediating adaptive immune responses (Jones et al., 2022). MALT1 paracaspase is critical for signaling antigen-stimulated effector T cells and maintaining immune homeostasis in resting T cells (Noels et al., 2007). In this study, the authors show how hnRNP U and hnRNP L, both RBPs rich in RGG/RG motifs, bind competitively to stem-loop RNA structures involving the 5′ and 3′ss of MALT1 exon 7 to influence AS. A representative selection of genes that play a role in the regulation of AS during inflammation are summarized in Table 2. Cumulatively, these studies shed light on RGG/RG domains and their ability to facilitate the molecular recognition of cellular RNAs. However, more studies are needed to understand their role in AS fully.

Table 2.

Representative Studies Involving Alternative Splicing and Inflammation (2020-Present)

| Year | Model | Gene | Novelty | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | SC Mice | KRAS | Upregulation of splicing factor SRSF1 expression increases pancreatitis and KRASG12D-mediated tumorigenesis through IL-1 and MAPK signaling pathways. | Wan et al. (2023) |

| 2023 | HT22 cells | NR3C1 | NR3C1 affects gene expression of inflammation transcription factors such as Trim33, Kdm1a, Nfctc1, and Hif-1A, through alterations in their splicing patterns, which play a role in the pathogenesis of PTSD. | Li et al. (2023b) |

| 2023 | MSCs | PPP2R1B, HNRNPLL | Lnc-PPP2RIB interacts with HNRNPLL to regulate the splicing of PPP2R1B, which induces Runx2 and OSX expression leading to osteogenesis. | Peng et al. (2023) |

| 2023 | Primary human small airway epithelial cells | BRD4 | BRD4-mediated AS plays a crucial role in regulating the innate activation of XBP1, ATP11A, and IFRD1, which are involved in tumorigenesis and fibrosis. | Mann et al. (2023) |

| 2023 | ESCC cell lines | DGCR5 | Discovered the mechanism behind Wnt signaling in lncRNA splicing and proposed the DGCR5 splicing switch as a vulnerability in ESCC. The DGCR5-S (short form) inhibits TTP anti-inflammatory response, facilitating tumor-promoting inflammation. | Li et al. (2023c) |

| 2023 | Mouse and human livers | SRPK2 | SRPK2 regulation of AS plays a role in lipogenesis in humans with ALD. FGF21 inhibits SRPK2, which can improve ALD pathologies. | Li et al. (2023a) |

| 2022 | Rat PC12 cells | PCBP1 | PCBP1 modulated the expression of neuroinflammatory genes such as LCN-2 and AS of ubiquitination-related gene WWP-2. | Yusufujiang et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | Transgenic mouse lung pneumocytes | CASP9 | Caspase 9 undergoes AS to produce proapoptotic caspase 9a and prosurvival C9b, two opposing isoforms. Caspase 9b can modulate lung inflammation, immune cell influx, and peripheral immune response by directly activating the NF-κB pathway in vivo. | Kim et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | RAW264.7 macrophage | MYD88 | Downregulation of splicing factor SF3A1 allowed liver X receptor agonist T0901317 to increase the short form of MyD88 mRNA, leading to NF-κB-mediated inflammation inhibition. | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 2022 | HK2 cells | ANXA2 | ANXA2 regulated AS of inflammatory genes UBA52, RBCK1, and LITAF. | Chen et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | T cells | CASP9, BAX, and BCL2L11 | Caspase 9, Bax, and Bim isoforms induced by CD3/CD28 costimulation promote resistance to apoptosis. Changes in all three gene function combinatorially to promote T cell viability. | Blake et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | Human dermal fibroblasts | IKBKG | Overexpression of the NEMO-Δex5 isoform stabilized the IKK protein (IKKi). Immune cells and TNF-stimulated dermal fibroblasts upregulated IKKi, promoting type I IFN induction and antiviral responses. | Lee et al. (2022) |

| 2021 | Mouse macrophage | AIM2 | The unannotated alternative first exon isoform of Aim2 is predominantly expressed during inflammation and contains an iron-responsive element that enables regulation of mRNA translation through its iron levels. | Robinson et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | Pancreas | SRSF5 | SRSF5 caused HnRNP L-DDX17 interaction, inhibiting tRF-21 biogenesis. HnRNP-L-DDX17 activity preferentially spliced caspase 9 and mH2A1 pre-mRNAs, promoting cell malignant phenotypes. | Pan et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | Human cardiomyocytes | WTAP | WTAP promoted myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating m6A modification of ATF4 mRNA, promoting stress in the endoplasmic reticulum and cell apoptosis. | Wang et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | Murine NAFLD models and liver cancer cell lines | ESRP2 | Chronic inflammation suppresses expression of ESRP2, an RNA splicing factor that activates NF2, in hepatocytes. Loss of NF2 permits sustained YAP/TAZ activity, imposing a selection pressure that favors the survival of mutated liver cells during chronic oncogenic stress. | Hyun et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | Mouse cardiomyocytes | HSPA1A | HSPA1A can play a role in cardiac hypertrophy by regulating the AS of asxl2 and runx1. | Li and Yang (2021) |

| 2021 | Mouse prefrontal cortex | NRXN 1–3 | The inclusion of the Nrxn 1–3 AS4 exon significantly increased in the prefrontal cortex of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Splicing changes are correlated with local Il1β-expression. | Marchese et al. (2021) |

| 2021 | Mouse and human livers | RELA | Levels of p65 and spliced variant p65 iso5 mRNA are higher in SARS-CoV-2 patients than in healthy subjects. The ability of p65 iso5 to bind dexamethasone identifies it as a possible new therapeutic target to control inflammation and related diseases. | Spinelli et al. (2021) |

| 2020 | Pancreatic β cells | NLRC5 | By mediating the effects of IFNα on AS, NLRC5 may be a central player in the effects of IFNα on β cells that trigger and amplify autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes. | Szymczak et al. (2022) |

| 2020 | Mouse alveolar macrophages | Various DEGs | In alveolar macrophages, lung inflammation induced substantial alternative pre-mRNA splicing. | Janssen et al. (2020) |

| 2020 | Murine macrophages | MYD88 | AS of MyD88 may provide a mechanism that ensures robust termination of inflammation for tissue repair. | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 2020 | HeLa cells | RBM4 | The inclusion of TNIP1 exon mediated by RBM4 affects target expression in inflammatory pathways. RBM4 can mediate inflammatory response via splicing regulation. | Wang et al. (2020) |

ALD, alcohol liver disease; DEG, differentially expressed gene; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; hnRNP, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein; IFN, interferon; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TTPs, tristetraprolins.

The Redox Role of AS in Immunity

Redox regulation of the immune response consists of complex mechanisms that control the activation or suppression of the inflammatory response. The production of ROS/reactive nitrogen species will cause various redox-sensitive transcription factors and enzymes to alter the activity of cellular antioxidants and, in the process, affect the performance of macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells (Noels et al., 2007). During the early period of inflammation, myeloid cells undergo polarization through classical activation pathways to form proinflammatory (M1) macrophages in defense against intracellular bacteria or viruses. As the inflammation persists, an alternate activation pathway polarizes (M2) macrophages to help tissue healing tolerate self-antigens and regain homeostasis (Dou et al., 2019). Macrophages are derived from blood monocytes, and they play a significant role in maintaining the stability of the internal environment. Their role in detecting pathogens and cancerous cells, undergoing phagocytosis, and secreting proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, contributes to their proapoptotic activity (Mantovani et al., 2022).

A recent area of scientific scrutiny concerns how myeloid cells undergo post-transcriptional changes during immune cell differentiation (Liu et al., 2018). Liu et al. (2018) differentiated human primary monocytes into M1 macrophages using granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor or M2 macrophages using macrophage colony stimulating factor. They studied changes in differential AS events (DASEs) using high-depth RNA-seq profiling (Fig. 6). DASEs refer to the variations in AS patterns of pre-mRNA transcripts that occur due to cellular signals, environmental or developmental cues. Their function is often to increase proteomic complexity in eukaryotic organisms. Lipopolysaccharide/interferon-gamma (IFNγ) or anti-inflammatory cytokines were also used to differentiate monocytes into macrophages. DASEs from M1 macrophages clustered in innate immunity pathways involving pleckstrin-homology domains, whereas M2 macrophages were enriched in different immunity pathways, such as c-type lectin-like and chemotaxis.

FIG. 6.

Monocyte differentiation and splicing events. Monocytes polarize into functionally distinct M1/M2 macrophage programs by GM-CSF and M-CSF cytokines. TLR4 recognizes cytokines, PAMPs, and DAMPs to activate MyD88 and TIRAP. Signal transduction pathways activate MAP and IKK kinases that regulate the expression of different cytokines, such as NF-κB, AP1, and CSF-1. NF-κB and AP1 produce proinflammatory cytokines, including GM-CSF, whereas CSF-1 produces anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as M-CSF. GM-CSF and M-CSF can undergo AS modulation, specifically as a cassette exon event. This generates different isoforms of GM-CSF and M-CSF, such as included/excluded isoforms. These cytokines are then excreted from the cell and used to differentiate monocytes into their respective macrophages, propagating their inflammatory response. DAMP, damage-associated molecular pattern; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor; M-CSF, macrophage colony stimulating factor; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4. Adapted from Kawasaki and Kawai (2014) and Liu et al. (2018). Created with Biorender.com

Several RBPs had changes in expression of ≥2-fold, including MBNL2 and RBFOX2, which are functionally significant in regulating primary monocyte differentiation. AS analyses revealed the inclusion of the cassette exon upon differentiation in seven DASEs (NUMB, SBF1, ADAM15, GOLIM4, GSNK1G3, PPP1R12A, and FNBP1) and switched 5′ss usage in NCOR2. These data offer new insights into the regulatory networks impacting human diseases, such as myotonic dystrophies (DM1/2), caused by repeat RNA expansions that sequester MBNL1, turning the AS in adult tissues into that of undifferentiated cells (Konieczny et al., 2014). However, more studies are necessary to determine how monocytes and macrophages compromise patients with DM, leading to immunosuppression and muscle, cardiac, and neurological disorders.

Yang et al. (2022) recently demonstrated a new dimension of how AS regulated the transformation from inflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages when they investigated the contribution by long-noncoding RNA 260 (lncRNA260). First, the population of M2 murine macrophages derived from in vitro differentiation of bone marrow-derived macrophages was significantly reduced following hypoxia/reperfusion treatment. This phenotype was reversed by treatment with siRNAs targeting lncRNA260. When they investigated the AS of IL-28 receptor α (IL-28RA) in M2 polarized cells, they observed that M2 polarization correlated significantly with a reduction in the IL-28RAV2 AS variant. The IL-28RA gene undergoes AS to generate two splice variants, IL-28RAV1 and IL-28RAV2, widely expressed in the heart, bone marrow, pancreas, thyroid, skeletal muscle, prostate, and testis (Yang et al., 2010).

Modulating the AS of IL-28RA has important ramifications because IL-28RAV2 inhibits IFNλ1 and type III IFN, which plays an important role in anticell proliferation while promoting an inflammatory response (Gong et al., 2017). The authors showed that the AS variant IL-28RAVl leads to the upregulation of M2 biomarkers, for example, ARG1, p-AKT, and PI3KCG (by some unknown mechanism), causing activation of JAK-STAT and PI3K/AKT signaling. The overall result of these molecular signaling pathways is M2-type polarization, leading to a lower inflammatory response, which may have significant consequences for reduced myocardial cell damage and ventricular remodeling during acute MI.

The intersection between AS, inflammation, autophagy, and OS has also been investigated in retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (Leong et al., 2022). RP causes progressive retinal degeneration, has no cure, and can cause a defect in the accumulation of ROS inside photoreceptors (Gallenga et al., 2021). Recently, Leong et al. (2022) studied genes enriched in RNA splicing and proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic processes in 3D retinal organoids generated from Usher type 1B-retinitis pigmentosa (USH1B)-RP patient-derived pluripotent stem cells. They performed single-cell RNA sequencing and showed that MYO7A expression in rod photoreceptors and Müller glial cells correlated with changes in the neural retina leucine zipper rods and apoptotic signaling pathways in cells rich in intermediate filament proteins. Future studies will be necessary to determine whether this human model for USH1B-RP can translate to discovering potential biomarkers for RP.

Some other exciting developments linking splicing modulation to immunity come from new investigations into how pharmacological intervention could be exploited to generate aberrant mRNAs encoding novel proteins or neoepitopes (Lu et al., 2021). The idea is that if a subset undergoes translation, it might be presented by MHC I as neoepitopes and provoke antitumor immunity. Functional studies showed that 30 of 70 (∼43%) candidate neoantigenic peptides could elicit a CD8+ T cell immune response in naive C57BL/6 mice by IFNγ. This study addressed the following interesting questions. The first is how splicing modulation affects CD4+ T cells and MHC II-presented neoantigens. Second, how do cancer-associated mutations in RNA splicing factors affect checkpoint immunotherapy? Finally, other posttranscriptional modifications, such as intronic polyadenylation, would unexpectedly occur by the induced pharmacological modulation of AS.

Although further studies are needed to answer these questions, the presentation of novel immunogenic factors by therapeutic modulation of AS offers the hope of a new avenue for developing clinically relevant therapeutic applications.

The Regulation of AS and Ischemia-Related Stress

Hemorrhagic shock, resection, and organ transplantation clinically manifest IRI, a dynamic process that involves the two interrelated phases of local ischemic insult and inflammation-mediated reperfusion injury (Dery and Kupiec-Weglinski, 2022). Various pathways are activated during organ IRI, including toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling, ROS generation, cell death regulation, and innate and adaptive immunity activation. One area of active scientific interest is the role that damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) play in IRI. Sosa et al. (2021) recently showed that donor hepatic tissues release high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) into patient portal blood following reperfusion and that it translocated into the cytoplasm of macrophages in IRI-positive OLT patients. DAMPs include HMGB1, Hsp60 and Hsp70, ROS, fibrinogen, fibronectin (FN), hyaluronic acid, and heme and play a role in activating pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like teceptor 4 (TLR4), to initiate the inflammatory response (Dery et al., 2023b; Sosa et al., 2021).

IRI leads to significant clinical manifestations after organ transplantation, including allograft rejection. So far, no therapeutic modalities have emerged; therefore, understanding the combinatorial effects of cellular/molecular activation pathways that regulate AS immune and inflammatory IRI cascades may be insightful (Ito et al., 2021). Recent genome-wide gene expression profiling studies have estimated that more than >1000 genes are upregulated following IRI (Zamorano et al., 2021). Gene Ontology pathway analyses revealed that many of these genes are involved in inflammatory responses, hypoxia, mitogen-activated protein kinase, NF-κB, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathways. Despite the large number of documented changes in gene expression that occur during IRI, our understanding of the post-transcriptional mechanisms that play a role remains severely limited.

One of the early studies that identified a role for splicing variants in organ transplantation investigated FN in rat cardiac allografts and isografts (Coito et al., 1997). FN is a multidomain extracellular matrix glycoprotein implicated in pathological conditions such as adhesion, differentiation, growth, embryonic development, blood clotting, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and transplantation (Coito et al., 2000; van Hoolwerff et al., 2023). In the case of cancer, the loss of FN leads to tumor cells freeing themselves from their primary growth site by metastasizing to other parts of the body. The importance of FN and its contribution as a model for understanding how AS regulation leads to the development and disease (Murphy et al., 2021) was recently recognized as the subject of the 2022 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award (Burki, 2022).

Three possible isoforms are generated by alternative processing of the FN primary transcript: extra domain A (EDA), extra domain B (EDB), and type III homologies connecting segment. Coito et al. (2000) showed that AS of the EDA exon, but not EDB, is regulated explicitly in cardiac transplantation. The localization of EDA splice isoforms closely associated with infiltrating leukocytes was prominent in the myocardium of the rejecting allografts. These data are important for establishing how leukocyte effectors migrate and function in allografts versus isografts and could provide a foundation for testing novel antirejection concepts and therapeutic strategies in transplant recipients.

More recently, full-length transcriptomic analysis of murine and human hearts has been investigated under IR stress (Oehler et al., 2022). Oehler et al. (2022) identified 58,440 AS events that originated from a subset of 12,789 murine genes and focused on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) for its complex genomic region/structure. PGC-1α functions as a transcriptional coactivator but is assembled by extensive AS events regulated by different promoters (Martínez-Redondo et al., 2016). The authors then presented evidence of novel PGC-1α transcripts and promoters that are differentially expressed under a high-fat diet in a diabetic cardiomyopathy model. Whether the differences in PGC-1α expression observed in IR-injured diet-induced obesity mouse groups translate to diabetic patients with MI remains to be determined. More studies should focus on pathomechanistic insights into the complex regulatory mechanisms of PGC-1α expression and function in these patients' hearts.

Clinical Considerations Using AS Technology

Decades of effort to map the etiology of many human chronic diseases have revealed a central role for AS gene dysregulation in diabetes (Wu et al., 2021), cardiovascular diseases (Hasimbegovic et al., 2021), neurodegenerative diseases (Krach et al., 2022), alcoholic liver disease (Baralle and Baralle, 2021), chronic kidney disease (Lin et al., 2022), cancer (Murphy et al., 2022), and aging (Bhadra et al., 2020). More than 11.5 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms located throughout the human genome can negatively alter the concentration, localization, or activity of RBPs. These mutations can also lead to somatic mutations that alter cassette exon splicing and intron retention (Madsen et al., 2007). Mutations occurring in the noncoding intronic 5′ and 3′ splice donor sites (GT and AG dinucleotides) account for 15% of hereditary human diseases (Jiang and Chen, 2021).

Some examples include a nonsense mutation in exon 18 of BRCA1, which disrupts the interaction of splicing factor ASF/SF2 with proximal exon splicing enhancers (ESEs) (Liu et al., 2001). ESEs are short sequences that are encoded in the exons of expressed mRNAs and play a role in coordinating with proteins known as serine/arginine-rich proteins to enhance recognition of nearby splice sites. Another study showed that an AT→GT point mutation in the intron of the human estrogen receptor causes a cryptic 5′ss in intron 5, leading to the insertion of a 69-nucleotide cryptic exon into the reading frame (Wang et al., 1997). A dominantly inherited genetic disease (limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 1 B) is caused by a 5′ donor-site mutation (G→C) that causes the retention of intron 9, leading to nonsense-mediated decay of the primary transcript (Muchir et al., 2000).

More recently, a global search was conducted to detect intronic branch point motifs underlying human diseases using massively parallel sequencing data (Zhang et al., 2022). Intriguingly, a branch point motif found two nucleotides upstream of the traditional consensus BP (BP-2) showed a lower variation rate in human populations and higher evolutionary conservation.

Many studies are now using precision medicine and targeted therapies to deliver small-molecule drugs (Tang et al., 2021), monoclonal antibodies (Bessa et al., 2020), and splice-switching oligonucleotides (SSOs) (Ham et al., 2021) to modulate RNA splicing pathways. SSOs are short-modified synthetic nucleic acids that base pair with pre-mRNA, which disrupts normal splicing mechanisms by blocking protein-RNA binding complexes to the pre-mRNA, essentially blocking transcription (Havens and Hastings, 2016). Interest in SSO-based drugs has grown because of their ability to treat diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked disorder that stimulates muscle degeneration, and cystic fibrosis (CF), an inherited autosomal recessive disease that causes breathing and digestion problems. SSOs are used in DMD to produce functional dystrophin proteins by restoring the ORF (Disterer et al., 2014).

Patients who received the clinically approved SSO drug showed a decrease in serum creatine phosphokinase, which is typically abnormally high in patients with DMD, indicating reduced stress damage to muscle fibers (Sergeeva et al., 2022). Clinical trials in the recruitment phase are scheduled to test SSOs and therapeutic efficacy targeting splice isoforms with oligonucleotide blockers in CF (ClinicalTrials.gov). Another clinical trial was conducted to investigate whether next-generation peptide-conjugated phosphorodiamidate morpholino (MO) oligomers can effectively treat patients with DMD who are amenable to exon 51 skipping (NCT05100823 and NCT04004065).

MOs are stable water-soluble molecules that block complementary RNA sequences and prevent proteins from binding to these sites for processing (Moulton, 2017). Studies have shown that when MOs are complementary to sequences in the 5′-untranslated region, the first 25 coding bases of mRNA can inhibit the initiation complex, preventing the formation of the ribosome and blocking the translation of mRNA into polypeptides. Du and Gatti (2011) reported that antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (AMOs) are effective in treating genetic disorders, such as primary immunodeficiency diseases, and conditions that play a role in maintaining or developing the immune system. AMOs can also be used in potential cancer treatments through the modulation of splicing.

A study by Shieh et al. (2009) reported that myeloid cell leukemia-1 AMOs could be helpful for potential cancer therapy, as these AMOs can target Mcl-1 pre-mRNA to shift splicing patterns to produce proapoptotic Mcl-1S (short form), which activates apoptosis in basal cell carcinoma cells. Our studies with AMOs have shown that MOs targeting the hnRNP L-binding site on variable exon 7 of human CEACAM1 disrupt IRF1-directed AS (Dery et al., 2018). More recently, we showed that AMOs, designed to selectively induce mouse Ceacam1-S, protected hepatocyte cultures against temperature-induced stress in vitro (Dery et al., 2023a).

Other notable approaches that are currently in development involve the use of RNA inhibition and CRISPR gene-editing technologies. Small-interfering RNAs' significant function in post-transcriptional gene silencing has gained attention for silencing genes involved in developmental, oncogenic, metabolic, neurological, immunological, and circulatory origins. One therapeutic designed by Arbutus Pharma consists of lipid nanoparticles (ARB-001467) containing multiple RNA interference triggers that target viral transcripts used to treat patients with chronic hepatitis B patients (Alshaer et al., 2021). Patients treated with this drug showed reduced serum hepatitis B antigen levels, indicating the efficacy of siRNA therapy. Following a similar path of scientific inquiry, a recent study showed how CRISPR-edited cells and antisense oligos could be used to force the expression of specific isoforms for therapeutic benefits (Blake et al., 2022).

This study specifically investigated how T cell costimulation through the CD28 receptor affects AS in T cells activated through the T cell receptor (CD3). Moreover, antisense oligonucleotides in CRISPR-edited cells can induce CD28-enhanced splicing events in caspase 9, Bax, and Bim, which are genes involved in the apoptotic signaling pathway. Significantly, these isoforms promote resistance to apoptosis and further promote cell viability. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the potential of molecule-mediated spliceosome modulation in the treatment of human diseases.

Future Considerations

The plethora of complex AS cellular networks that depend on hundreds of splicing-related proteins acting in trans, with a similar number of diseases affected by mutations in cis-elements, offers a seemingly limitless number of targeting possibilities in pursuit of using molecule-mediated RNA splicing (MMRS) for novel clinical therapeutics. For example, the recent clinical study using risdiplam, an oral survival of motor neuron 2 (SMN2) pre-mRNA splicing modifier, has been approved for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) (Mercuri et al., 2023). Fifty-one individuals with types 2 and 3 SMA, aged 2–25 years, were tested for safety, efficacy, and dosing regimens between 12 weeks and 24 months. Results showed that risdiplam increased SMN protein by twofold, but whether this level was sufficient to gain function or improve will require more studies. Importantly, branaplam is now facing phase II trials for the same therapeutic application (Manigrasso et al., 2021).

Another promising MMRS modulator is the synthetic pladienolide derivative called H3B-8800, which appears efficacious against tumors with splicing factor mutations in SF3B1, U2AF, and SRSF2 (Seiler et al., 2018). Pladienolides are mRNA splicing inhibitors that decrease splicing capacity up to 75% in vitro (Ghosh and Anderson, 2012) and derive from the class of drugs used to manage and treat various bacterial infections. Phase I clinical trials showed that while the H3B-8800 appeared to act as expected, the clinical response to myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia did not fare well (Steensma et al., 2019). These studies reveal the challenges that remain in developing MMRS modulators, where the cellular context and benefit of splicing modulation for a particular disease must be weighed against searching for suitable prognostic biomarkers.

The holy grail in the AS field is to develop molecular tools that exploit the immunogenicity of AS protein products. However, as with most biological systems, caution is required when systems that depend on fine-tuning are manipulated. For example, conflicting studies of hnRNP M have shown its role as a splicing factor and transmembrane receptor. In a breast cancer model, we identified hnRNP M as an authentic RNA-splicing factor responsible for producing human CEACAM1-L (Dery et al., 2011).

However, other studies have shown that it has the most unusual property of being a transmembrane protein involved in colorectal cancer metastasis, functioning as a receptor for carcinoembryonic antigen (Thomas et al., 2011), which protects tumor cells from anoikis, a form of programmed cell death. Therefore, alterations of hnRNP M may have the unintended consequences of promoting one splice isoform in the case of one type of genetic disease but unexpectedly activating tumor cell progression in another.

Moreover, several studies have shown that pretranscriptional modifications can influence post-translational phosphorylation, methylation, and sumoylation of splicing factors, affecting not only the RNA splicing pathway but also other aspects of cell biology (Leva et al., 2012; Rouvière et al., 2013; Sinha et al., 2010). The emergent picture is that while the use of MMRS is promising, it could unintentionally affect the function of the cis and trans regulators of AS, changing the particular gene, the exon and intron sizes, the cellular context, and the developmental state or physiological requirements of the cell. More studies are needed to establish safety protocols that include genotypic characterization, optimization of delivery parameters (timing, route, and frequency of administration [inhaled vs. intravenous]), screening for the development of off-target pathways, understanding humoral immune responses, and determining the factors that lead to patient complications.

Another important question that needs more study is what role do AS pathways play in what has been referred to as the antioxidant paradox in the interdependent relationship between OS and inflammation (Biswas, 2016). Why do many antioxidant therapies fail to produce beneficial effects in human diseases that are linked to OS and inflammation? For example, while low-grade chronic inflammation and OS occur in many chronic diseases, activating similar pathways involving NF-κB and cytokines/chemokines, selected agents targeting both oxidative and inflammatory pathways are not clinically relevant. Therefore, future clinical trials should target AS gene regulatory pathways that act in concert to alleviate OS and inflammation in a tissue- or cell-specific manner (i.e., on target).

The use of bioinformatic tools (e.g., extended local similarity analysis, linear discriminant analysis effect size) and logistic/random-forest classifiers should be developed to provide cogent analyses of the molecular signaling maze and the cross talk that occurs at the cellular level (Dery et al., 2023b). Novel computational methods are being developed to identify and optimize RNA-targeted small molecules, to characterize RNAs' intrinsic structural flexibility better, and to demonstrate how small molecules functionally target important structured RNAs (Manigrasso et al., 2021). Computer-assisted molecular docking studies that identify putative ligand–pocket docking complexes that are energetically favorable may better help to develop RNA-targeted virtual screening methods (Clark, 2020). Wang et al. (2020) recently developed predictive and prognostic AS signatures in lung adenocarcinoma using machine learning methods (Cai et al., 2020).

Taken together, combining machine learning and deep learning techniques will generate the data needed to appreciate the mechanisms at work better and thus improve long-term clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Despite the impressive number of discoveries over more than 40 years of extensive research on the mechanisms of AS, its role in human diseases remains to be fully defined. Comprehensive profiling of the genes that undergo AS during OS-related tissue IRI may open new avenues for developing clinical therapeutics. Part of the challenge will be translating the one gene → one protein → one disease phenotype model into more three-dimensional molecular models, ultimately leading to better designed animal and clinical studies and helping us understand how AS affects broader biological systems.

Key Points

AS is a critical step in gene expression pathways that increase the coding capacity of the human genome.

Failure of AS pathways to function correctly may lead to misidentification of the wrong splice sites causing human disease.

MMRS is an exciting development that switches the splicing of specific deleterious isoforms toward a more beneficial isoform.

Deep machine-learning techniques will identify genes amenable to therapeutic targeting in human splicing disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank UCLA student interns Brian Cheng, Aanchal Kasargod, Richard Chiu, and former mentors Ren-Jang Lin, PhD, and Jack Shively, PhD, for their insightful discussions on AS mechanisms. All authors have seen the article and consented to be included here. There was no assistance in the preparation of the article.

Abbreviations Used

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- ALD

alcohol liver disease

- AMOs

antisense morpholino oligonucleotides

- AS

alternative splicing

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BS

branch site

- CAMK2G

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, gamma

- CEACAM1

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CTD

carboxyterminal domain

- DAMPs

damage-associated molecular patterns

- DASEs

differential AS events

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- DMOG

dimethyloxalylglycine

- EDA

extra domain A

- EDB

extra domain B

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- ESE

exon splicing enhancer

- FN

fibronectin

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor

- GRSF1

G-rich sequence factor 1

- Hif-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- HMGB1

high mobility group box 1

- HNF4α1

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α

- hnRNP

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- HuR

human antigen R

- IFNγ

interferon-gamma

- IL

interleukin

- IL-28RA

IL-28 receptor α

- IR

ischemia/reperfusion

- IRF1

interferon response factor 1

- IRI

ischemia/reperfusion injury

- lncRNA260

long-noncoding RNA 260

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- Lv1

L variant 1

- m7G

7-methylguanosine

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- M-CSF

macrophage colony stimulating factor

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MMRS

molecule-mediated RNA splicing

- MOs

morpholinos

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MSCs

mesenchymal stem cells

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplantation

- ORF

open reading frame

- OS

oxidative stress

- PAMPs

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha

- PLD

plitidepsin

- PPT

polypyrimidine tract

- PTBP1

polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1

- RBFOX1

RNA-binding protein, fox-1 homolog 1

- RBMX

RNA binding motif protein X-linked

- RBP

RNA-binding protein

- RNAi

RNA interference

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RP

retinitis pigmentosa

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- SMA

spinal muscular atrophy

- SMN2

survival of motor neuron 2

- snRNP

smaller nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle

- SRSF1

serine- and arginine-rich splicing factor 1

- ss

splice site

- SSO

splice-switching oligonucleotides

- Tjp1

tight junction protein 1

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TTPs

tristetraprolins

- USH1B

Usher type 1B-retinitis pigmentosa

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization: K.J.D.; writing—original draft: K.J.D., Z.W., and M.W.; writing—review and editing: K.J.D., Z.W., and J.W.K.-W.; visualization: K.J.D. and Z.W.; funding acquisition: J.W.K.-W.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by NIH grants P01 AI120944, R01 DK062357, R01 DK107533, and R01 DK102110 (Jerzy W. Kupiec-Weglinski).

References

- Alshaer W, Zureigat H, Al Karaki A, et al. siRNA: Mechanism of action, challenges, and therapeutic approaches. Eur J Pharmacol 2021;905:174178; doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annalora AJ, Marcus CB, Iversen PL. Alternative splicing in the nuclear receptor superfamily expands gene function to refine endo-xenobiotic metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 2020;48(4):272–287; doi: 10.1124/dmd.119.089102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonicka H, Sasarman F, Nishimura T, et al. The mitochondrial RNA-binding protein GRSF1 localizes to RNA granules and is required for posttranscriptional mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Metab 2013;17(3):386–398; doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader D, Patel RS, Lui A, et al. Multi-level regulation of PKCδI alternative splicing by lithium chloride. Mol Cell Biol 2020;41(3); doi: 10.1128/mcb.00338-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baralle M, Baralle FE. Alternative splicing and liver disease. Ann Hepatol 2021;26:100534; doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barinaga M. Introns pop up in new places—What does it mean? Science 1990;250(4987):1512; doi: 10.1126/science.2125746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat Rev Genet 2002;3(5):370–379; doi: 10.1038/nrg798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berget SM, Moore C, Sharp PA. Spliced segments at the 5’ terminus of adenovirus 2 late mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1977;74(8):3171–3175; doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessa C, Matos P, Jordan P, et al. Alternative splicing: Expanding the landscape of cancer biomarkers and therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21(23):9032; doi: 10.3390/ijms21239032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra M, Howell P, Dutta S, et al. Alternative splicing in aging and longevity. Hum Genet 2020;139(3):357–369; doi: 10.1007/s00439-019-02094-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK. Does the interdependence between oxidative stress and inflammation explain the antioxidant paradox? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016;2016:5698931; doi: 10.1155/2016/5698931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D, Radens CM, Ferretti MB, et al. Alternative splicing of apoptosis genes promotes human T cell survival. Elife 2022;11:80953; doi: 10.7554/eLife.80953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki T. Lasker awards 2022. Lancet 2022;400(10358):1093–1094; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01877-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bush SJ, Chen L, Tovar-Corona JM, et al. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017;372(1713); doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabej NR. 2-Epigenetics of Reproduction in Animals. In: Building the Most Complex Structure on Earth. (Cabej NR. ed.) Elsevier: Oxford; 2013; pp. 59–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, He B, Zhang P, et al. Exploration of predictive and prognostic alternative splicing signatures in lung adenocarcinoma using machine learning methods. J Transl Med 2020;18(1):463; doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02635-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Cinkornpumin JK, Yu Z, et al. Deletion of RBMX RGG/RG motif in Shashi-XLID syndrome leads to aberrant p53 activation and neuronal differentiation defects. Cell Rep 2021;36(2):109337; doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell T, Hawsawi O, Henderson V, et al. Novel roles for HMGA2 isoforms in regulating oxidative stress and sensitizing to RSL3-Induced ferroptosis in prostate cancer cells. Heliyon 2023;9(4):e14810; doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo RL, González-Candia A, Carrasco R. Editorial: Mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury in animal models and clinical conditions: Current concepts of pharmacological strategies. Front Physiol 2022;13:880543; doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.880543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checa J, Martínez-González I, Maqueda M, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screening identifies novel pathways/genes involved in oxidative stress and repurposable drugs to preserve cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cell integrity. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021;10(12):1936; doi: 10.3390/antiox10121936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Liu Y, Xia S, et al. Annexin A2 (ANXA2) regulates the transcription and alternative splicing of inflammatory genes in renal tubular epithelial cells. BMC Genomics 2022;23(1):544; doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08748-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Moore MJ. Spliceosomes. Curr Biol 2015;25(5):R181–R183; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MN, Jin H.. The RGG motif proteins: Interactions, functions, and regulations. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA; 2022:e1748; doi: 10.1002/wrna.1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DE. Virtual screening: Is bigger always better? Or can small be beautiful? J Chem Inf Model 2020;60(9):4120–4123; doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, Brown LF, Peters JH, et al. Expression of fibronectin splicing variants in organ transplantation: A differential pattern between rat cardiac allografts and isografts. Am J Pathol 1997;150(5):1757–1772. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coito AJ, de Sousa M, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Fibronectin in immune responses in organ transplant recipients. Dev Immunol 2000;7(2–4):239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordaux R, Hedges DJ, Herke SW, et al. Estimating the retrotransposition rate of human Alu elements. Gene 2006;373:134–137; doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries T, Martelly W, Campagne S, et al. Sequence-specific RNA recognition by an RGG motif connects U1 and U2 snRNP for spliceosome assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119(6):e2114092119; doi: doi: 10.1073/pnas.2114092119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol Genet Metab 1999;67(3):183–193; doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dery KJ, Gaur S, Gencheva M, et al. Mechanistic control of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-1 (CEACAM1) splice isoforms by the heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear proteins hnRNP L, hnRNP A1, and hnRNP M. J Biol Chem 2011;286(18):16039–16051; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]