Abstract

Following the description of an illustrative case of a 70-year-old female patient with longstanding active acromegaly and invalidating, progressive joint complaints, current insights regarding diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of acromegalic arthropathy are summarized. Since clinical trials on this topic are lacking, the reported recommendations are based on extensive clinical and research experience with this clinical entity, and on established diagnostics and interventions in patients with other rheumatic diseases. The cornerstones of the management of acromegalic arthropathy remains normalization of growth hormone and insulin growth factor-1 levels. However, patients with severe or progressive acromegalic arthropathy require a multidisciplinary approach to determine adequate diagnostics and treatment options. Because of the high prevalence and invalidating character of acromegalic arthropathy, developing evidence-based effective prevention and treatment strategies, preferably by international collaboration within rare disease networks, e.g., Endo-ERN, is a clear unmet need.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11102-024-01465-1.

Keywords: Acromegaly, Arthropathy, Osteoarthritis, Management, Treatment

Case presentation

A 70-year-old female patient was diagnosed with acromegaly at the age of 56 years in 2008, after which she was referred to our expert center for pituitary diseases. At the time of diagnosis, she presented with temporary headaches, and optical nerve palsy, which recovered spontaneously. Retrospectively, she had a longstanding history of ‘unexplained’ complaints, including lack of energy, excessive sweating, facial changes, acral growth with the need of a larger wedding ring and shoe size, surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS, 2008), and emotional lability. Moreover, polyarticular joint complaints had been present for over 6 years, which resulted in two joint replacements (left hip (2004), and right knee (2006)), and the presence of osteoarthritic changes in both hands. Prior to the diagnosis of acromegaly, orthopedic surgeons assumed rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which was ruled out following referral to a specialized rheumatological clinic.

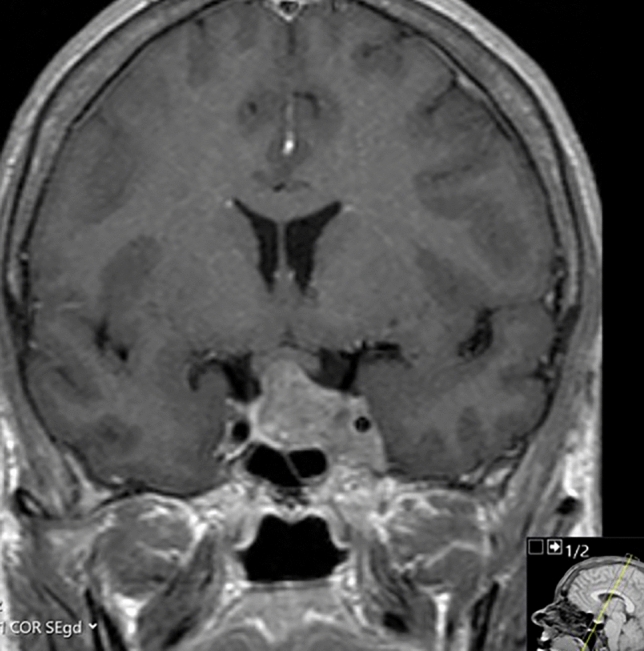

At the time of diagnosis, laboratory results showed significantly elevated growth hormone (GH; random 43.90 mU/L, and nadir following glucose suppression test 16.20 mU/L (reference range 0.00–7.25 mU/L) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels of 96.3 nmol/L (1.3 × upper limit of normal (ULN), reference range 7.0–76.0 nmol/L), and insufficient corticotropic, gonadotropic and thyrotropic axes. The pituitary MRI scan revealed a macroadenoma with invasion of the left cavernous sinus hampering total resection, as shown in Fig. 1. Cardiac examination showed left ventricular hypertrophy with mild diastolic dysfunction, and a moderate mitral and tricuspid valve insufficiency, whilst colonoscopy showed multiple colonic polyps with low grade dysplasia: all presumably complications of longstanding (undiagnosed) GH excess.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the sellar region. In 2008, the diagnostic coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of the sellar region after intravenous administration of contrast revealed a macroadenoma with invasion of the left cavernous sinus and some compression of the optic chiasm

She underwent transsphenoidal surgery for tumor debulking in 2009, which could not be curative due to the cavernous sinus invasion. Additionally, pharmacological treatment with dopamine agonist (DA) and somatostatin receptor ligands (SRL) at maximum dosages was started, followed by an SRL switch to Pegvisomant because of side effects (viz., alopecia). In the meantime, she received an additional right hip prosthesis (2010) because of secondary degenerative joint disease. Because of insufficient biochemical disease control with pharmacological therapy (random GH 9.49 mU/L, and IGF-1 393 nmol/L), she received pituitary radiotherapy in 2012. In 2015, Pegvisomant was stopped, after which she remained in biochemical remission to date (random GH 0.57 mU/L, IGF-1 level 9.3 nmol/L (reference range 5.1–22.0 nmol/L). Seven years after radiotherapy, she developed a GH deficiency (peak GH 5.7 mU/L using GHRH arginine test) without beneficial effects of 0.2 mg recombinant human GH (rhGH) supplementation (IGF-1 levels 14.6 nmol/L, reference range 5.1 – 22.0 nmol/L). Simultaneously, the corticotropic and thyrotropic axes were supplemented adequately. Bone mineral density (BMD) following rhGH treatment was assessed at the lumbar spine (T-score − 1.1, Z-score + 0.9; potentially unreliable due to degeneration), with hip BMD being unreliable due to joint prosthesis, and distal forearm BMD being unavailable.

Despite achievement of biochemical remission, she had progressive, joint pain and stiffness in the hands, knees, hips, shoulders, ankles, and feet—varying in intensity depending on the joint. The joint complaints negatively influenced her daily functioning, with walking for over 15 min becoming impossible, resulting in the need for gait aids for long distances, pain medication, and physiotherapy, although she did not experience any beneficial effect of physiotherapy. Prior to retirement, she could work for 6 h a week. She was, however, able to bike and swim (non-weight-bearing exercise) without noticeable limitations. Radiographically, significant progression of structural abnormalities with end-stage arthropathy at multiple joint sites, as shown in Fig. 2, was observed. She received repetitive steroid injections in the left knee, followed by a 4th large joint prosthesis (total left knee prosthesis) in May of 2022.

Fig. 2.

Radiographic examination of the hands, knees, and hips with follow-up. The first detailed radiographic examination of the joint complaints occurred in 2010 (A, B, C), with a follow-up detailed examination in 2016 (D, E). A Dorsovolar radiograph of the hands. Osteoarthritis of the hands, predominantly in the interphalangeal joints but also in other joints such as the MCP joints. B Posteroanterior radiograph of the knees. Osteoarthritis in the left knee, total knee replacement in the right knee. C Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Severe osteoarthritis in the right hip, total hip replacement on the left side. D Follow-up dorsovolar radiograph of the hands. Progression of the osteoarthritis in the hands, predominantly in the interphalangeal and MCP joints but also in other joints. E Follow-up posteroanterior radiograph of the knees. Progression of the osteoarthritis in the left knee

Background

Acromegaly is characterized by GH and IGF-1 excess, resulting in a plethora of clinical complaints [1–5]. Although multimodality treatment strategies—surgical pituitary adenoma resection, radiotherapy, and pharmacological treatment (i.e., SRL, Pegvisomant, DAs)—are available to induce disease remission in most patients with amelioration of clinical symptoms and life expectancy, many patients suffer from (partially) irreversible, persistent, or delayed complaints due to the longstanding disease history, suboptimal biochemical control, or signs of mild GH excess [5, 6]. A major component of longstanding complaints despite disease remission are the musculoskeletal complications of acromegaly, i.e., acromegalic osteopathy with skeletal fragility, and acromegalic arthropathy [7, 8].

Acromegalic arthropathy is one of main drivers of impaired health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) [6]. Previously, clinical, and radiographic characteristics of acromegalic arthropathy in the most subjectively affected joints have been assessed (i.e., hips, knees, hands, shoulders, feet, and spine joints [2, 3, 6, 9–12]). Compared to the general population, the prevalence of arthropathy is two to nine times higher—depending on the joint site—despite biochemical remission [3]. About 70% of patients in remission report joint symptoms, and virtually all patients have radiographic structural changes, which occur in a poly-articular pattern in > 95% of patients [12, 13].

The unique radiographic phenotype of patients with acromegalic arthropathy (i.e. primarily osteophytosis with widened joint spaces reflecting cartilage hypertrophy), is clearly different from primary osteoarthritis (OA) [14–17]. However, patients with smoldering, persistent acromegaly activity showed joint space narrowing (JSN), and more severe joint complaints more often than patients without JSN [18]. Risk factors for primary OA have been reported to also influence risk of acromegalic arthropathy (e.g., age, sex, and BMI [19–22]), and there are acromegaly-specific risk factors (e.g. baseline IGF-1 levels, and disease duration [14–18]). Moreover, progression of acromegalic arthropathy—clinically or radiographically—has been reported for a considerable proportion of patients, independent of disease remission [10–12], with higher age, higher baseline IGF1 levels, treatment with SRL [10], and increased severity of arthropathy at baseline being the main risk factors [12].

Both acromegalic osteopathy and arthropathy are understudied to date. Recently, the current landscape of literature on the diagnosis and management of acromegalic osteopathy was summarized [7]. Despite efforts by our institution and other centers, unfortunately, little is known regarding treatment and management of acromegalic arthropathy, being a clear unmet need in the care for patients with acromegaly [13]. Although there are similarities between joint disease in acromegaly and primary OA, many features are distinct, requiring a unique diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Therefore, we aim to summarize current insights regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of acromegalic arthropathy based on our extensive clinical and research experience, describing an illustrative case of a patient with acromegaly with progressive and invalidating joint complaints.

Clinical assessment and diagnostics (Box 1)

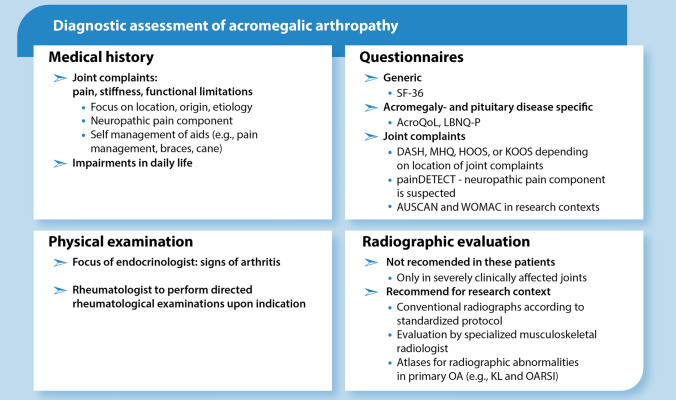

Box 1.

Diagnostic assessment of acromegalic arthropathy. AcroQoL Acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, AUSCAN Australian/Canadian osteoarthritis index, DASH Disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand, HOOS Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score, KL Kellgren and Lawrence, KOOS Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score, LBNQ-P Leiden Bother and needs questionnaire for pituitary patients, MHQ Michigan hand outcomes questionnaire, OARSI Osteoarthritis research society, SF-36 Short form-36; WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Medical history and physical examination

In this section, we summarize our findings and recommendations regarding the diagnostic options of patients with acromegalic arthropathy (Box 1). All patients with acromegaly are at risk for developing arthropathy, with specific risk factors contributing to increased risk, or increased bother in daily life, or more need for support regarding musculoskeletal disease. During general periodical visits by the endocrinologist (vide infra), a basic history assessment can be performed to screen for patients requiring specific attention for joint disease.

In case of positive screening questions, musculoskeletal symptoms need to be characterized in detail by history taking and physical examination to investigate whether a differential diagnosis can be considered, how these complaints impact daily life, and if treatment is required. This history taking should focus on onset and course over time, location (mono-articular vs poly-articular), type of joint complaints—including nociceptive and neuropathic pain-like symptoms (e.g., tingling or prickling)—and the presence of joint-related or general symptoms which could be attributed to arthritis independent of acromegaly. Additionally, limitations in activities and restrictions in societal participation should be assessed, considering hobbies, family/social life, and occupation of the patient. Furthermore, the beneficial effects of previously attempted specific interventions (e.g., taping, braces, pain medication, intra-articular injections) or lifestyle changes need to be evaluated. Physical examination, including the joints, needs to be performed, with the recognition of other underlying diseases causing the joint complaints (e.g., arthritis) being the main aim of the assessment.

Based on the findings during the history taking and physical examination, patients should be referred to a rheumatologist, an orthopedic surgeon, a physiotherapist, or occupational therapist. When signs of arthritis are observed (viz., redness, warmth, swelling/hydrops, limited extension), the patient needs to be referred to a rheumatologist to exclude an underlying (immune-mediated) rheumatic disease. Notably, a relationship between acromegaly and (inflammatory) rheumatic diseases has not been proven [23].

Use of validated questionnaires

In our value-based health care (VBHC) care path for patients with pituitary adenomas, routine use of validated questionnaires is commonplace. For patients with acromegaly, several questionnaires might be useful, including both generic and pituitary- and acromegaly-specific questionnaires. In research settings, several joint-specific questionnaires on self-reported joint symptoms have been used in patients with acromegaly [11, 12, 24–26]. These questionnaires can aid in the characterization of (the severity of) joint complaints, as well as evaluation of the impact on HR-QoL, and the specific bothers and needs prior to and after (alterations in) treatment.

In Supplemental File 1, generic HR-QoL questionnaires, as well as disease-specific quality of life questionnaires (i.e., Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (AcroQoL), Leiden Bother and Needs Questionnaire for patients with pituitary disease (LBNQ-Pituitary)), as well as domain-specific questionnaires assessing joint complaints are described in more detail [27–51]. At present, the LBNQ-Pituitary is the most frequently used questionnaire in clinical practice in our pituitary VBHC care path to signal whether adjustments in the management are necessary [30].

For the assessment of joint complaints in research settings, multiple joint-specific questionnaires have been used, albeit none of them validated for patients with acromegaly. Several questionnaires focused on care outcomes in patients with OA are being developed at present, which should be assessed for their usefulness in patients with acromegaly in the future.

Radiographic assessment

Conventional radiography

Clinically affected joints can be radiographically investigated using conventional radiographs. As is the case in primary OA, radiographic examination is not commonplace, and only indicated for patients in which a differential diagnosis needs radiological examination, or when joint replacement surgery is considered. When radiographs are indicated, a standardized radiological protocol should be used, as has been described for our center [12, 13].

Analysis of structural joint abnormalities and their severity can be performed in multiple ways. In the context of research in patients with primary OA, the semi-quantitative Kellgren and Lawrence (KL), and Osteoarthritis Research Society (OARSI) methods are the most well-known (vide infra). In the absence of validated methods for acromegalic arthropathy, both radiographic scoring methods can be used. In clinical practice, however, these scoring techniques are seldomly used.

In studies of patients with acromegaly, the most used scoring method is the semi-quantitative KL system, which is based on the evaluation of the presence of osteophytes (OP), JSN, sclerosis, and degenerative cysts in a specific joint, resulting in a composite score ranging from 0 to 4 on a 5-point Likert scale [52]. To improve scoring reliability, comparison atlases with examples of several KL scores are available for multiple joints (e.g., hands, knees, hips, spine), but unfortunately not for all (e.g., shoulders, feet). Another scoring method used in research is the OARSI scoring system [53, 54], evaluating individual radiographic OA characteristics separately: OP, JSN, misalignment, erosion, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts. These characteristics are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3. Unfortunately, the characteristic joint space widening (JSW)—hallmark of acromegalic arthropathy—is not included in any of the existing scoring methods, and might be overlooked. We therefore recommend detailed examination by an experienced musculoskeletal radiologist for clinical care purposes. For research purposes, we recommend the OARSI scoring system with the addition of (potentially automated [55–57]) JSW reading for the in-depth assessment of acromegalic arthropathy, since OA characteristics abnormalities are scored individually.

Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging

A more detailed radiographic assessment of the joint(s) might be needed. Ultrasonography is a non-invasive, high-resolution imaging technique without the need for radiation. For joint assessment, ultrasonography can detect, amongst others, effusions, and ligament and cartilage injury, which can aid in the detection of inflammatory diseases (i.e., arthritis tendinitis, and bursitis). On the other hand, the role for ultrasonography in diagnosing OA is limited. Moreover, reproducibility of ultrasonography during follow-up remains highly dependent on the specialized ultrasonographer.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be performed, e.g., to exclude traumatic injury with cartilage or ligament tears, or other subtle structural changes. Previously, we have successfully and reliably performed MRI scans of the knee in patients with acromegaly, which showed the characteristic structural changes as well as decreased cartilage quality [58]. For degenerative joint disease, however, MRI scans are not indicated in the clinical diagnostic trajectory. Moreover, MRI scans are expensive, time consuming, and have limited availability.

Categorization of patients depending on severity of arthropathy

Based on the presence of complaints, amount and location of affected joints, patients are divided into three categories: patients without joint complaints, patients with mono-articular disease (one singular joint affected) and poly-articular disease (multiple joint locations affected, e.g., hip and knee, or shoulder and hip). Moreover, patients will be divided into clinically affected, and radiologically affected, or both.

Treatment modalities and clinical management (Box 2)

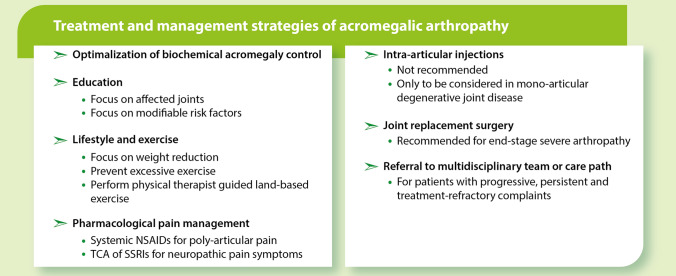

Box 2.

Treatment and management strategies of acromegalic arthropathy. NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, SSRI serotonin reuptake inhibitor, TCA tricyclic anti-depressant

Following adequate and appropriate diagnostic strategies, we summarize our findings and recommendations regarding the treatment options and management of patients with acromegalic arthropathy (Box 4). Notably, none of the strategies outlined in this section have been formally evaluated, and are, therefore, not evidence-based in patients with acromegaly at this time. Most of the described strategies have been assessed in, and are, therefore, evidence-based for patients with primary OA.

Management of acromegalic disease activity

The mainstay of acromegalic arthropathy management is adequate biochemical control of disease activity and symptom control [10–12, 18, 26, 59, 60]. Since controlled patients after surgical cure were reported to have improved joint outcomes compared to pharmacologically controlled patients in previous studies [12], we recommend to evaluate whether further improvement of disease control is possible, e.g., whether a second surgery could be beneficial or pharmacological treatment can be intensified, also when a patient has acceptable IGF-1 levels (i.e., 1.2xULN) but still active disease symptomatology.

As mentioned, the use of pharmacological treatment (SRL, Pegvisomant and dopamine agonist combined) was associated with an increased risk of short-term progression of radiographic OA [10]. Moreover, SRL exposure, calculated using the dosage and duration of SRL use, was related to increased short-term radiographic OA progression, in particularly of JSN [10, 18], which was no longer observed during long-term follow-up studies [12]. Speculating, these observations could be the consequence of smoldering or residual disease activity in medically treated patients, or a direct effect of SRL itself, since SSTR are demonstrated in both joint and cartilage cells [61, 62]. As pharmacological treatment is initiated because of (persistent) disease activity, however, confounding by indication affects these observations.

Management of joint complications

Next to the improvement of biochemical disease control, management should be focused on relief of joint complaints, and improvement of functionality. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the different steps of the management of joint complaints in more detail [13].

Education

Education on joint disease in acromegaly and associated modifiable risk factors is essential to improve self-management strategies [63, 64]. The most important modifiable risk factors, partially dependent on joint location, are overweight, joint injuries, and specific muscle weakness [65, 66]. Moreover, patients should be educated on how to cope with joint complaints and the therapeutic options available in general, and those applicable to their specific needs. Patient education and training of self-management strategies can occur through several ways (e.g. face-to-face meetings, group sessions, videoconferences, and telephone-based sessions, provided by e.g. specialized nurses and/or social workers/psychologists) [67]. For patients with primary OA, self-management programs are available, albeit their efficacy has not been proven [68], whereas in patients with pituitary diseases (not specifically for acromegalic arthropathy), the effectiveness of self-management programs has clearly been shown [69].

Lifestyle and exercise

One of the most important recommendations for patients with acromegaly is maintaining a healthy lifestyle, with a healthy diet and exercise routine, and these lifestyle improvements are likely to aid in a favorable joint outcome [63, 64, 67, 70–72]. In primary OA, weight reduction in overweight and obese individuals is a well-studied and effective method to decrease strain on the weight-bearing joints. Moreover, decrease of adipose tissue mass may lead to a decrease in chronic inflammation and subsequent degenerative changes [73, 74]. Recently, a network meta-analysis on the effects of dietary interventions on the WOMAC questionnaire outcomes reported that to obtain a 50% reduction of the WOMAC score, a 25% weight reduction from baseline is necessary [75], indicating the potential of weight reduction, although the amount of weight reduction described in this study is very extreme. Notably, weight reduction should always be paired with adequate exercise routes to preserve lean body mass, and in frail patients, dietary weight management is, therefore, not recommended [76, 77].

Rehabilitation, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and aids

Analogous with the clinical practice guidelines for polyarticular primary OA, we recommend referral to a specialized physiotherapist for guided, structured, land-based exercise programs as a core treatment for acromegalic arthropathy [63, 64, 67, 71, 78, 79], preferably early in the disease course. As an alternative, at-home exercise programs for patients with acromegaly might be beneficial as well [80]. Moreover, gait aids and mind–body exercise might be recommended in case of arthropathy of the knee and hip, based on their favorable efficacy and safety profiles in primary OA [63]. For patients with acromegaly and hand OA, physical therapy, and occupational therapy, as well as the use of aids and orthoses might results in reduced symptom severity, as mentioned in the guidelines for primary hand OA [66]. Furthermore, changes in foot shape and plantar pressure related to acromegaly, can be supported by orthopedic insoles or (semi-)orthopedic shoes in order to prevent complications and reduce potential overload and lower extremity pain [81].

Pharmacological pain management

In patients with persistent or progressive complaints, pharmacological pain management might be of use for symptom relief. In patients with mono-articular complaints of the knee and hand, the use of topical pain-relieving creams or gels can be used [63]. For poly-articular complaints, we recommend the use of non-selective NSAIDs (e.g., naproxen), or selective COX-2 inhibitors (e.g., etericoxib, or rofecoxib) as a first-line treatment, but only on demand for short periods of time, since there is no evidence for pain relief with chronic use in combination with an unfavorable toxicity profile.

Although most patients with acromegaly suffer from nociceptive joint pain, a minority of patients (i.e., around 25%) present with (possible) neuropathic pain-like symptoms [24]. Since neuropathic pain requires a different pharmacological approach, neuropathic pain-like symptoms need to be recognized early. Patients with neuropathic pain-like symptoms could benefit from treatment with specific neuropathic pain medication, including tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), anti-epileptic drugs (e.g., pregabalin/gabapentin), or a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (e.g., duloxetine [82–84]).

Intra-articular injections

Intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid are expected to be of limited value because of the poly-articular nature of acromegalic arthropathy in most patients, and are, therefore, not recommended [64, 66, 85]. However, in the rare case of mono-articular joint complaints with signs of an inflammatory origin, intra-articular corticosteroids can be considered.

Joint replacement surgery

In case of persistent invalidating end-stage arthropathy, joint replacement surgery, or other articular surgical interventions, can be considered as a last resort [86]. Orthopedic surgery should be considered in patients with pain, limited mobility, and functional disabilities, when conservative treatment strategies have failed to provide symptomatic relief or improvement of quality of life. Conventional radiographs are used to assess the severity of radiographic OA. Joint replacement surgeries should be planned following expert consultation with an orthopedic surgeon. From a translational research perspective, the joint tissues and biological materials removed during joint replacement surgery (i.e., ligaments, cartilage, and bone) could provide us with valuable insights on the underlying mechanisms of joint disease in acromegaly. In the future, a biobank for joint tissues, potentially in cooperation with the national and European scientific societies and the European Reference Network for endocrine conditions (Endo-ERN) might be considered.

Multidisciplinary team referral and intensive care path for complex patients

Patients with acromegaly with persistent or progressive arthropathy could be referred to an expert center with a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) consisting of specialized endocrinologists, rheumatologists, radiologists, orthopedic surgeons, pain specialists, rehabilitation physicians, and psychologists for expert opinion. During MDT meetings, the appropriate actions to be taken for individual patients need to be discussed. In our center, an intensive 6-week multi-disciplinary care path exists for patients with common rheumatological diseases (e.g., RA), including weekly or twice-weekly sessions with a rheumatologist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and psychologist. This intensive care path encompasses detailed diagnostics and therapeutic strategies, with the aim for optimal management of joint disease. Following this 6-week care path, patients will be referred back to their treating physician with an individualized management advice. This care path can serve as an example for the creation of a VBHC care path for patients with acromegalic arthropathy, highlighting the improvement of care for rare diseases though regular care for more common diseases.

Discussion and future perspectives

In the present overview, we highlighted the recommended diagnostic and management options for patients with acromegalic arthropathy based on extensive clinical expertise, the current literature from acromegaly arthropathy, and guidelines for patients with primary OA. In absence of clinical trials focusing on acromegalic arthropathy, all diagnostic and treatment strategies mentioned are not (yet) evidence-based, highlighting the need for studies on this topic.

First, the necessity of a knowledgeable and experienced MDT needs to be stressed for the adequate diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, as well as the management of acromegalic arthropathy. Organizing care within expert centers—functioning as a pituitary center of excellence (PTCOE)—with MDTs with additional expertise in joint disease on long-term complications of acromegaly (including acromegalic arthropathy in patients with acromegaly) is preferred [87–90].

As the diagnostic age for acromegaly and primary OA is ≥ 50 years, and acromegalic arthropathy has been associated with older age, the outlined recommendations also apply for elderly patients [91, 92]. Regardless of acromegaly, management of elderly patients should focus on maintenance or improvement of muscle mass and function and decreasing the risk of falling, and for potential surgeries or other interventions, the health status, comorbidities, as well as the chances to achieve the surgical goal and potential risks, need to be carefully considered [63, 64, 67, 71, 78, 79].

The recommended strategies focus on joint complaints. Although these strategies aim for optimal management, patients might suffer from persistent residual complaints with a negative impact on their daily functioning and quality of life [5–8]. Patient education programs and/or individual counseling by a psychologist can support patients with coping with these complaints and their effect on daily life [69].

Due to the direct and indirect effects of GH and IGF-1 on bone, patients with acromegaly can suffer from both arthropathy and osteopathy. Acromegalic osteopathy is characterized by a decrease in bone quality resulting in skeletal fragility and increased fracture risk, despite normal BMD measured by DXA scans [5, 7, 8, 93]. As for arthropathy, adequate control of disease activity is the cornerstone of treatment of acromegalic osteopathy [5, 7, 8, 93]. Additionally, maintaining a eugonadal state and adequate vitamin D levels may improve bone quality [5, 7, 8, 93]. Notably, bone acting drugs have been shown to decrease incident vertebral fractures in patients with active disease [94]. Moreover, the effects of bone-acting drugs in patients with acromegaly with disease control might play an additional role—as in patients with osteoporosis [95–97], although studies are lacking.

Notably, not all therapeutic strategies are without risk, and the risks and benefits of joint replacement surgeries especially must be weighed on an individual patient level whilst considering their overall (medical) situation. Because of the concomitant osteopathy [8, 93], joint implants theoretically might take longer to adhere to the bone (in the case of uncemented prostheses), or might results in fragility fractures of the weakened bone next to the implant, or other forms of aseptic loosening or dislocation of the implant, as reported in the sole small cohort study in patients with acromegaly [98]. Although these complications have not occurred in patients with acromegalic arthropathy following joint replacement surgery in our expert center, the potential risks in this specific patient group must be considered. Expert knowledge on joint replacement surgeries in patients with acromegaly should be combined nationally or internationally, as these surgeries are not performed by one dedicated orthopedic surgeon for all patients.

Several therapeutic or management strategies have not been mentioned prior, one of which being dietary supplements, vitamins, and minerals. However, in our experience, patients with acromegaly do use several supplements to increase bone and cartilage health, of which glucosamine was the most frequently used. In literature, the effects of these supplements on bone and cartilage health in primary OA is not recommend [99–101].

All therapeutic strategies described in the previous sections focus on symptomatic relief in patients with acromegalic arthropathy, whereas cure or prevention of acromegalic arthropathy is not attainable to date. The potential beneficial effect of education, weight loss, or physical therapy prior for the prevention of joint complaints needs to be assessed. In the future, more detailed characterization of the different phenotypes of acromegalic arthropathy – presence of OP, JSN or JSW—will aid in the discovery of new treatment strategies, as patients exhibit different radiographic phenotypes: an OA-like phenotype, or a characteristically acromegalic phenotype [18, 58]. For these phenotypes, the impact of GH excess might play a different, yet-to-be-elucidated role. Moreover, prospective studies should focus on the natural history and disease course in these patients using standardized and protocolized outcome measures. Moreover, translational studies using tissue samples (e.g., cartilage and bone resected during joint replacement surgery) should focus on the underlying mechanisms, and, thereby, potential drug targets, of the development of acromegalic arthropathy.

In conclusion, recommended diagnostic, therapeutic, and management strategies, as well as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, of patients with acromegalic arthropathy have been summarized. To date, treatment options are solely symptomatic, not curative as in OA and pragmatic and not evidence based. Therefore, future studies should focus on effective prevention and treatment strategies of arthropathy in acromegaly, preferably within international collaborations to join forces for this rare condition, as this is a great unmet need for patients with acromegaly.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Iris C.M. Pelsma: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Project administration. Herman M. Kroon: Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. Cornelie D. Andela: Investigation, Data Curation, Draft Writing—Review & Editing. Enrike M.J. van der Linden: Writing—Review & Editing. Margreet Kloppenburg: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing. Nienke R. Biermasz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. Kim M.J.A. Claessen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or funding details to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dekkers OM, Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, Vandenbroucke JP (2008) Mortality in acromegaly: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93(1):61–67. 10.1210/jc.2007-1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassenaar MJ, Biermasz NR, Kloppenburg M, van der Klaauw AA, Tiemensma J, Smit JW, Pereira AM, Roelfsema F, Kroon HM, Romijn JA (2010) Clinical osteoarthritis predicts physical and psychological QoL in acromegaly patients. Growth Horm IGF Res 20(3):226–233. 10.1016/j.ghir.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wassenaar MJ, Biermasz NR, van Duinen N, van der Klaauw AA, Pereira AM, Roelfsema F, Smit JW, Kroon HM, Kloppenburg M, Romijn JA (2009) High prevalence of arthropathy, according to the definitions of radiological and clinical osteoarthritis, in patients with long-term cure of acromegaly: a case-control study. Eur J Endocrinol 160(3):357–365. 10.1530/eje-08-0845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cushing H (1909) Partial hypophysectomy for acromegaly: with remarks on the function of the hypophysis. Ann Surg 50(6):1002–1017. 10.1097/00000658-190912000-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colao A, Ferone D, Marzullo P, Lombardi G (2004) Systemic complications of acromegaly: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management. Endocr Rev 25(1):102–152. 10.1210/er.2002-0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F (2005) Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(5):2731–2739. 10.1210/jc.2004-2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giustina A (2023) Acromegaly and bone: an update. Endocrinol Metab 38(6):655–666. 10.3803/EnM.2023.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazziotti G, Lania AG, Canalis E (2022) Skeletal disorders associated with the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor 1 axis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 18(6):353–365. 10.1038/s41574-022-00649-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wassenaar MJ, Biermasz NR, Bijsterbosch J, Pereira AM, Meulenbelt I, Smit JW, Roelfsema F, Kroon HM, Romijn JA, Kloppenburg M (2011) Arthropathy in long-term cured acromegaly is characterised by osteophytes without joint space narrowing: a comparison with generalised osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 70(2):320–325. 10.1136/ard.2010.131698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claessen KM, Ramautar SR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Roelfsema F, Romijn JA, Kroon HM, Kloppenburg M, Biermasz NR (2012) Progression of acromegalic arthropathy despite long-term biochemical control: a prospective, radiological study. Eur J Endocrinol 167(2):235–244. 10.1530/eje-12-0147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claessen KM, Ramautar SR, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, Kroon HM, Kloppenburg M, Biermasz NR (2014) Increased clinical symptoms of acromegalic arthropathy in patients with long-term disease control: a prospective follow-up study. Pituitary 17(1):44–52. 10.1007/s11102-013-0464-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelsma ICM, Biermasz NR, van Furth WR, Pereira AM, Kroon HM, Kloppenburg M, Claessen K (2020) Progression of acromegalic arthropathy in long-term controlled acromegaly patients: 9 years of longitudinal follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelsma ICM, Kroon HM, van Trigt VR, Pereira AM, Kloppenburg M, Biermasz NR, Claessen K (2022) Clinical and radiographic assessment of peripheral joints in controlled acromegaly. Pituitary. 10.1007/s11102-022-01233-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkan, A.: Acromegalic arthropathy and sleep apnea. J Endocrinol 155 Suppl 1, S41–44; discussion S45 (1997). [PubMed]

- 15.Barkan AL (2001) Acromegalic arthropathy. Pituitary 4(4):263–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colao A, Cannavo S, Marzullo P, Pivonello R, Squadrito S, Vallone G, Almoto B, Bichisao E, Trimarchi F, Lombardi G (2003) Twelve months of treatment with octreotide-LAR reduces joint thickness in acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 148(1):31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colao A, Marzullo P, Vallone G, Giaccio A, Ferone D, Rossi E, Scarpa R, Smaltino F, Lombardi G (1999) Ultrasonographic evidence of joint thickening reversibility in acromegalic patients treated with lanreotide for 12 months. Clin Endocrinol 51(5):611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claessen KM, Kloppenburg M, Kroon HM, Romijn JA, Pereira AM, Biermasz NR (2013) Two phenotypes of arthropathy in long-term controlled acromegaly? A comparison between patients with and without joint space narrowing (JSN). Growth Horm IGF Res 23(5):159–164. 10.1016/j.ghir.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakagawa Y, Hyakuna K, Otani S, Hashitani M, Nakamura T (1999) Epidemiologic study of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with plain radiography. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 8(6):580–584. 10.1016/s1058-2746(99)90093-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ansok CB, Muh SJ (2018) Optimal management of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Orthop Res Rev 10:9–18. 10.2147/ORR.S134732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibounig T, Simons T, Launonen A, Paavola M (2020) Glenohumeral osteoarthritis: an overview of etiology and diagnostics. Scand J Surg. 10.1177/1457496920935018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh JH, Chung SW, Oh CH, Kim SH, Park SJ, Kim KW, Park JH, Lee SB, Lee JJ (2011) The prevalence of shoulder osteoarthritis in the elderly Korean population: association with risk factors and function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 20(5):756–763. 10.1016/j.jse.2011.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prencipe N, Scarati M, Manetta T, Berton AM, Parisi S, Bona C, Parasiliti-Caprino M, Ditto MC, Gasco V, Fusaro E, Grottoli S (2020) Acromegaly and joint pain: is there something more? A cross-sectional study to evaluate rheumatic disorders in growth hormone secreting tumor patients. J Endocrinol Invest 43(11):1661–1667. 10.1007/s40618-020-01268-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelsma ICM, van Trigt VR, Kroon HM, Pereira AM, van der Meulen C, Kloppenburg M, Biermasz NR, Claessen KMJA (2021) Low prevalence of neuropathic-like pain symptoms in long-term controlled acromegaly. Pituitary. 10.1007/s11102-021-01190-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wassenaar M, Biermasz N, Kloppenburg M, van der Klaauw A, Tiemensma J, Smit J, Pereira A, Roelfsema F, Kroon H, Romijn J (2010) Clinical osteoarthritis predicts physical and psychological QoL in acromegaly patients. Growth Hormon IGF Res 20:226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelsma ICM, Kroon HM, van Trigt VR, Pereira AM, Kloppenburg M, Biermasz NR, Claessen K (2022) Clinical and radiographic assessment of peripheral joints in controlled acromegaly. Pituitary 25(4):622–635. 10.1007/s11102-022-01233-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Verrips E (1998) Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 51(11):1055–1068. 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L (1992) Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305(6846):160–164. 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb SM, Prieto L, Badia X, Albareda M, Catala M, Gaztambide S, Lucas T, Paramo C, Pico A, Lucas A, Halperin I, Obiols G, Astorga R (2002) Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (ACROQOL) a new health-related quality of life questionnaire for patients with acromegaly: development and psychometric properties. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 57(2):251–258. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andela CD, Scharloo M, Ramondt S, Tiemensma J, Husson O, Llahana S, Pereira AM, Kaptein AA, Kamminga NG, Biermasz NR (2016) The development and validation of the leiden bother and needs questionnaire for patients with pituitary disease: the LBNQ-pituitary. Pituitary 19(3):293–302. 10.1007/s11102-016-0707-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan WS, Jain R, Dillon B, Clarke L, Fehily M, Ravenscroft M (2008) The ’M2 DASH’-manchester-modified disabilities of arm shoulder and hand score. Hand (N Y) 3(3):240–244. 10.1007/s11552-008-9090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaton DE, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Wright JG, Tarasuk V, Bombardier C (2001) Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther 14(2):128–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solway S, B.D., McConnell S, Bombardier C (2002) The DASH outcome measure user’s manual. In., vol. 2nd ed.

- 34.Veehof MM, Sleegers EJ, van Veldhoven NH, Schuurman AH, van Meeteren NL (2002) Psychometric qualities of the Dutch language version of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand questionnaire (DASH–DLV). J Hand Ther 15(4):347–354. 10.1016/s0894-1130(02)80006-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung KC, Pillsbury MS, Walters MR, Hayward RA (1998) Reliability and validity testing of the Michigan Hand outcomes questionnaire. J Hand Surg Am 23(4):575–587. 10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolte MT, Shauver MJ, Chung KC (2017) Normative values of the Michigan Hand outcomes questionnaire for patients with and without hand conditions. Plast Reconstr Surg 140(3):425e–433e. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klassbo M, Larsson E, Mannevik E (2003) Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score. An extension of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. Scand J Rheumatol 32(1):46–51. 10.1080/03009740310000409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klassbo M, Roos EM (2003) Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)–validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 4:10. 10.1186/1471-2474-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roos EM, Lohmander LS (2003) The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:64. 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD (1998) Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)–development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 28(2):88–96. 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellamy N, Campbell J, Haraoui B, Gerecz-Simon E, Buchbinder R, Hobby K, MacDermid JC (2002) Clinimetric properties of the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index: an evaluation of reliability, validity and responsiveness. Osteoarthr Cartil 10(11):863–869. 10.1053/joca.2002.0838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW (1988) Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 15(12):1833–1840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rienstra W, Blikman T, Mensink FB, van Raay JJ, Dijkstra B, Bulstra SK, Stevens M, van den Akker-Scheek I (2015) The modified painDETECT questionnaire for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: translation into Dutch, cross-cultural adaptation and reliability assessment. PLoS ONE 10(12):e0146117. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Andrés J, Pérez-Cajaraville J, Lopez-Alarcón MD, López-Millán JM, Margarit C, Rodrigo-Royo MD, Franco-Gay ML, Abejón D, Ruiz MA, López-Gomez V, Pérez M (2012) Cultural adaptation and validation of the painDETECT scale into Spanish. Clin J Pain 28(3):243–253. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31822bb35b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alkan H, Ardic F, Erdogan C, Sahin F, Sarsan A, Findikoglu G (2013) Turkish version of the painDETECT questionnaire in the assessment of neuropathic pain: a validity and reliability study. Pain Med 14(12):1933–1943. 10.1111/pme.12222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsubayashi Y, Takeshita K, Sumitani M, Oshima Y, Tonosu J, Kato S, Ohya J, Oichi T, Okamoto N, Tanaka S (2013) Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the painDETECT questionnaire: a multicenter observational study. PLoS ONE 8(9):e68013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gudala K, Ghai B, Bansal D (2017) Neuropathic pain assessment with the PainDETECT questionnaire: cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation to Hindi. Pain Pract 17(8):1042–1049. 10.1111/papr.12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sung JK, Choi JH, Jeong J, Kim WJ, Lee DJ, Lee SC, Kim YC, Moon JY (2017) Korean version of the painDETECT questionnaire: a study for cultural adaptation and validation. Pain Pract 17(4):494–504. 10.1111/papr.12472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cappelleri JC, Koduru V, Bienen EJ, Sadosky A (2015) A cross-sectional study examining the psychometric properties of the painDETECT measure in neuropathic pain. J Pain Res 8:159–167. 10.2147/jpr.S80046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freynhagen R, Tölle TR, Gockel U, Baron R (2016) The painDETECT project—far more than a screening tool on neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin 32(6):1033–1057. 10.1185/03007995.2016.1157460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR (2006) painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 22(10):1911–1920. 10.1185/030079906x132488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS (1957) Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16(4):494–502. 10.1136/ard.16.4.494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altman RD, Hochberg M, Murphy WA Jr, Wolfe F, Lequesne M (1995) Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 3:3–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altman RD, Gold GE (2007) Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthr Cartil 15:A1-56. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marijnissen AC, Vincken KL, Vos PA, Saris DB, Viergever MA, Bijlsma JW, Bartels LW, Lafeber FP (2008) Knee Images Digital Analysis (KIDA): a novel method to quantify individual radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis in detail. Osteoarthr Cartil 16(2):234–243. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jansen MP, Welsing PMJ, Vincken KL, Mastbergen SC (2021) Performance of knee image digital analysis of radiographs of patients with end-stage knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 29(11):1530–1539. 10.1016/j.joca.2021.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rayegan H, Nguyen HC, Weinans H, Gielis WP, Ahmadi Brooghani SY, Custers RJH, van Egmond N, Lindner C, Arbabi V (2023) Automated radiographic measurements of knee osteoarthritis. Cartilage 14(4):413–423. 10.1177/19476035231166126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Claessen K, Canete AN, de Bruin PW, Pereira AM, Kloppenburg M, Kroon HM, Biermasz NR (2017) Acromegalic arthropathy in various stages of the disease: an MRI study. Eur J Endocrinol 176(6):779–790. 10.1530/eje-16-1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biermasz NR, van Klooster R, Wassenaar MJ, Malm SH, Claessen KM, Nelissen RG, Roelfsema F, Pereira AM, Kroon HM, Stoel BC, Romijn JA, Kloppenburg M (2012) Automated image analysis of hand radiographs reveals widened joint spaces in patients with long-term control of acromegaly: relation to disease activity and symptoms. Eur J Endocrinol 166(3):407–413. 10.1530/eje-11-0795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wassenaar MJ, Biermasz NR, van der Klaauw AA, Pereira AM, Roelfsema F, Smit JW, Kroon HM, Kloppenburg M, Romijn JA (2009) High prevalence of arthropathy, according to the definitions of radiological and clinical osteoarthritis, in patients with long-term cure of acromegaly: a case-control study. Eur J Endocrinol 160(3):357–365. 10.1530/EJE-08-0845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vitali E, Palagano E, Schiavone ML, Mantovani G, Sobacchi C, Mazziotti G, Lania A (2022) Direct effects of octreotide on osteoblast cell proliferation and function. J Endocrinol Invest 45(5):1045–1057. 10.1007/s40618-022-01740-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bruns C, Dietl MM, Palacios JM, Pless J (1990) Identification and characterization of somatostatin receptors in neonatal rat long bones. Biochem J 265(1):39–44. 10.1042/bj2650039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Kraus VB, Lohmander LS, Abbott JH, Bhandari M, Blanco FJ, Espinosa R, Haugen IK, Lin J, Mandl LA, Moilanen E, Nakamura N, Snyder-Mackler L, Trojian T, Underwood M, McAlindon TE (2019) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 27(11):1578–1589. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, Callahan L, Copenhaver C, Dodge C, Felson D, Gellar K, Harvey WF, Hawker G, Herzig E, Kwoh CK, Nelson AE, Samuels J, Scanzello C, White D, Wise B, Altman RD, DiRenzo D, Fontanarosa J, Giradi G, Ishimori M, Misra D, Shah AA, Shmagel AK, Thoma LM, Turgunbaev M, Turner AS, Reston J (2020) 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthritis Rheumatol 72(2):220–233. 10.1002/art.41142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, Doherty M, Dziedzic KS, Greibrokk E, Haugen IK, Herrero-Beaumont G, Jonsson H, Kjeken I, Maheu E, Ramonda R, Ritt MJ, Smeets W, Smolen JS, Stamm TA, Szekanecz Z, Wittoek R, Carmona L (2019) 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 78(1):16–24. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, Callahan L, Copenhaver C, Dodge C, Felson D, Gellar K, Harvey WF, Hawker G, Herzig E, Kwoh CK, Nelson AE, Samuels J, Scanzello C, White D, Wise B, Altman RD, DiRenzo D, Fontanarosa J, Giradi G, Ishimori M, Misra D, Shah AA, Shmagel AK, Thoma LM, Turgunbaev M, Turner AS, Reston J (2020) 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee. Arthr Care Res 72(2):149–162. 10.1002/acr.24131 [Google Scholar]

- 67.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Hawker GA, Henrotin Y, Hunter DJ, Kawaguchi H, Kwoh K, Lohmander S, Rannou F, Roos EM, Underwood M (2014) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22(3):363–388. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kroon FP, van der Burg LR, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Johnston RV (2014) Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10.1002/14651858.CD008963.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andela CD, Repping-Wuts H, Stikkelbroeck N, Pronk MC, Tiemensma J, Hermus AR, Kaptein AA, Pereira AM, Kamminga NGA, Biermasz NR (2017) Enhanced self-efficacy after a self-management programme in pituitary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Endocrinol 177(1):59–72. 10.1530/EJE-16-1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt KD, Croft P, Doherty M, Dougados M, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kwoh K, Lohmander LS, Tugwell P (2007) OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthr Cartil 15(9):981–1000. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt KD, Croft P, Doherty M, Dougados M, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kwoh K, Lohmander LS, Tugwell P (2008) OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil 16(2):137–162. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S (2019) Osteoarthritis. Lancet 393(10182):1745–1759. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Collins KH, Lenz KL, Pollitt EN, Ferguson D, Hutson I, Springer LE, Oestreich AK, Tang R, Choi YR, Meyer GA, Teitelbaum SL, Pham CTN, Harris CA, Guilak F (2021) Adipose tissue is a critical regulator of osteoarthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 10.1073/pnas.2021096118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Loef M, van de Stadt L, Bohringer S, Bay-Jensen AC, Mobasheri A, Larkin J, Lafeber F, Blanco FJ, Haugen IK, Berenbaum F, Giera M, Ioan-Facsinay A, Kloppenburg M (2022) The association of the lipid profile with knee and hand osteoarthritis severity: the IMI-APPROACH cohort. Osteoarthr Cartil 30(8):1062–1069. 10.1016/j.joca.2022.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Panunzi S, Maltese S, De Gaetano A, Capristo E, Bornstein SR, Mingrone G (2021) Comparative efficacy of different weight loss treatments on knee osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Obes Rev 22(8):e13230. 10.1111/obr.13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang X, Miller GD, Messier SP, Nicklas BJ (2007) Knee strength maintained despite loss of lean body mass during weight loss in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62(8):866–871. 10.1093/gerona/62.8.866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Houston DK, Miller ME, Kitzman DW, Rejeski WJ, Messier SP, Lyles MF, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ (2019) Long-term effects of randomization to a weight loss intervention in older adults: a pilot study. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 38(1):83–99. 10.1080/21551197.2019.1572570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skou ST, Roos EM (2019) Physical therapy for patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis: supervised, active treatment is current best practice. Clin Exp Rheumatol 120(5):112–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.: In: Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. London (2022) [PubMed]

- 80.Lima TRL, Kasuki L, Gadelha M, Lopes AJ (2019) Physical exercise improves functional capacity and quality of life in patients with acromegaly: a 12-week follow-up study. Endocrine 66(2):301–309. 10.1007/s12020-019-02011-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Omma T, Tunc AR, Firat SN, Taskaldiran I, Culha C, Ersoz Gulcelik N (2022) Pedabarography may play a role in foot plantar scanning in acromegaly. Int J Clin Pract 2022:9882896. 10.1155/2022/9882896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown JP, Boulay LJ (2013) Clinical experience with duloxetine in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain. A focus on osteoarthritis of the knee. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 5(6):291–304. 10.1177/1759720X13508508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang ZY, Shi SY, Li SJ, Chen F, Chen H, Lin HZ, Lin JM (2015) Efficacy and safety of duloxetine on osteoarthritis knee pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Med 16(7):1373–1385. 10.1111/pme.12800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wohlreich M, Frakes E, Risser RC, Ahl J (2013) Duloxetine dose escalation in patients with osteoarthritis knee pain, who were taking optimized NSAIDs. Curr Med Res Opin 29(8):879. 10.1185/03007995.2013.806889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brophy RH, Fillingham YA (2022) AAOS clinical practice guideline summary: management of osteoarthritis of the knee (Nonarthroplasty), Third edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 30(9):e721–e729. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-01233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Akkaya M, Pignataro A, Sandiford N, Gehrke T, Citak M (2022) Clinical and functional outcome of total hip arthroplasty in patients with acromegaly: mean twelve year follow-up. Int Orthop 46(8):1741–1747. 10.1007/s00264-022-05447-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Giustina A, Uygur MM, Frara S, Barkan A, Biermasz NR, Chanson P, Freda P, Gadelha M, Haberbosch L, Kaiser UB, Lamberts S, Laws E, Nachtigall LB, Popovic V, Reincke M, van der Lely AJ, Wass JAH, Melmed S, Casanueva FF (2024) Standards of care for medical management of acromegaly in pituitary tumor centers of excellence (PTCOE). Pituitary 27(4):381–388. 10.1007/s11102-024-01397-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Giustina A, Uygur MM, Frara S, Barkan A, Biermasz NR, Chanson P, Freda P, Gadelha M, Kaiser UB, Lamberts S, Laws E, Nachtigall LB, Popovic V, Reincke M, Strasburger C, van der Lely AJ, Wass JAH, Melmed S, Casanueva FF (2023) Pilot study to define criteria for Pituitary Tumors Centers of Excellence (PTCOE): results of an audit of leading international centers. Pituitary 26(5):583–596. 10.1007/s11102-023-01345-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grottoli S, Ghigo E (2024) Pituitary tumor centers of excellence (PTCOE): the next border of acromegaly treatment. Pituitary 27(4):314–316. 10.1007/s11102-024-01416-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mortini P, Nocera G, Roncelli F, Losa M, Formenti AM, Giustina A (2020) The optimal numerosity of the referral population of pituitary tumors centers of excellence (PTCOE): A surgical perspective. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 21(4):527–536. 10.1007/s11154-020-09564-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dal J, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Andersen M, Kristensen LO, Laurberg P, Pedersen L, Dekkers OM, Sorensen HT, Jorgensen JO (2016) Acromegaly incidence, prevalence, complications and long-term prognosis: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol 175(3):181–190. 10.1530/eje-16-0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kropf LL, Madeira M, Vieira Neto L, Gadelha MR, de Farias ML (2013) Functional evaluation of the joints in acromegalic patients and associated factors. Clin Rheumatol 32(7):991–998. 10.1007/s10067-013-2219-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mazziotti G, Lania A, Canalis E (2019) MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Bone disorders associated with acromegaly: mechanisms and treatment. Eur J Endocrinol. 10.1530/EJE-19-0184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mazziotti G, Battista C, Maffezzoni F, Chiloiro S, Ferrante E, Prencipe N, Grasso L, Gatto F, Olivetti R, Arosio M, Barale M, Bianchi A, Cellini M, Chiodini I, De Marinis L, Del Sindaco G, Di Somma C, Ferlin A, Ghigo E, Giampietro A, Grottoli S, Lavezzi E, Mantovani G, Morenghi E, Pivonello R, Porcelli T, Procopio M, Pugliese F, Scillitani A, Lania AG (2020) Treatment of acromegalic osteopathy in real-life clinical practice: The BAAC (Bone Active Drugs in Acromegaly) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 10.1210/clinem/dgaa363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Marjoribanks J, Farquhar C, Roberts H, Lethaby A, Lee J (2017) Long-term hormone therapy for perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD004143. 10.1002/14651858.CD004143.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barrionuevo P, Kapoor E, Asi N, Alahdab F, Mohammed K, Benkhadra K, Almasri J, Farah W, Sarigianni M, Muthusamy K, Al Nofal A, Haydour Q, Wang Z, Murad MH (2019) Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women: a network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104(5):1623–1630. 10.1210/jc.2019-00192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mei Y, Williams JS, Webb EK, Shea AK, MacDonald MJ, Al-Khazraji BK (2022) Roles of Hormone replacement therapy and menopause on osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease outcomes: a narrative review. Front Rehabil Sci 3:825147. 10.3389/fresc.2022.825147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Guo L, Yang Y, An B, Yang Y, Shi L, Han X, Gao S (2017) Risk factors for dislocation after revision total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 38:123–129. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.12.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gallagher B, Tjoumakaris FP, Harwood MI, Good RP, Ciccotti MG, Freedman KB (2015) Chondroprotection and the prevention of osteoarthritis progression of the knee: a systematic review of treatment agents. Am J Sports Med 43(3):734–744. 10.1177/0363546514533777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wandel S, Juni P, Tendal B, Nuesch E, Villiger PM, Welton NJ, Reichenbach S, Trelle S (2010) Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis. BMJ 341:c4675. 10.1136/bmj.c4675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zeng L, Yu G, Hao W, Yang K, Chen H (2021) The efficacy and safety of Curcuma longa extract and curcumin supplements on osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 10.1042/BSR20210817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Zeng L, Yu G, Hao W, Yang K, Chen H (2021) The efficacy and safety of Curcuma longa extract and curcumin supplements on osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 10.1042/BSR20210817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.