Abstract

Introduction

Burns are associated with a high risk of developing comorbidities, including psychiatric disorders such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This study aimed to evaluate the association between PTSD and opioid use, chronic pain syndrome, and other outcomes following burn injuries.

Methods

A retrospective case-control analysis was conducted using the TriNetX database, a federated, de-identified national health research network with 92 healthcare organizations across the United States. Burn patients with and without PTSD were identified and matched based on demographics and injury severity. The likelihood of opioid use and other outcomes, including chronic pain, depression, anxiety, and emergency department visits, were compared between cohorts. Our study examined eight cohorts based on the percentage of total body surface area burned (TBSA%) and the presence or absence of PTSD. These cohorts were stratified as follows: patients with or without PTSD with TBSA, 1–19%, 20–39%, 40–59%, and 60+%. This stratification enabled a detailed comparison of outcomes across different levels of burn severity and the presence of PTSD, providing a comprehensive context for the results.

Results

The mean age of patients with PTSD was slightly higher (46 ± 16 years) than that of those without PTSD (43 ± 23 years). Incidence of PTSD ranged from 4.96 to 12.26%, differing by percentage of total body surface area burned (TBSA%). Significant differences in various complications and comorbidities were observed between patients with and without PTSD within each burn severity cohort. Compared to the patients without PTSD, patients with PTSD had a significantly higher risk of opioid use in all cohorts: TBSA 1–19%, 20–39%, 40–59%, and 60+%.

Conclusion

PTSD is associated with a significant increased likelihood of adverse outcomes following severe burns, particularly opioid use, chronic pain, psychological disorders, and higher healthcare utilization. These findings underscore the importance of identifying PTSD in burn patient management and highlight the need for further research into postoperative pain management strategies for this vulnerable population. Psychological assessments and cognitive behavioral therapy may be particularly useful.

Lay Summary

Burn injuries can cause serious problems like infections and organ failure, and they sometimes lead to death. Severe burns affect about 4.4% of all burn cases and can be deadly in nearly 18% of those cases. They cause inflammation that can lead to long-term heart, metabolism, and thinking problems. These injuries can also cause mental health issues like PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder).

PTSD means people might relive their trauma through bad memories or nightmares, avoid thinking about it, and feel different emotions for at least a month after it happens. People who survive burns often get PTSD because the injury is so traumatic and takes a long time to heal. Between 2% and 30% of burn survivors might feel very stressed soon after, and up to 40% could have PTSD within six months.

People with PTSD from burns often also have depression and anxiety because recovering and going back to normal life is tough. Doctors often give strong painkillers called opioids to burn patients, but they can be very addictive. People with PTSD and opioid problems often also have other mental health issues. A study in 2023 found that 80% of burn patients with opioid problems also had other mental health problems. This shows how important it is to treat pain and mental health carefully in burn survivors.

This study looks at how PTSD affects opioid use in people with burns. It uses data from many hospitals to see if PTSD makes pain worse and makes people use more opioids after surgery. Learning about this can help doctors find better treatments and stop people from using opioids too much if they have PTSD from a burn.

Keywords: Burns, post-traumatic stress disorder, opioid use, mental health

Introduction

A burn is a traumatic injury to either skin or organic tissue from thermal agents. When the injury covers 20% or more of the total body surface area (TBSA), it is associated with a greater potential of developing wound sepsis, multiorgan dysfunction, and death. 1 According to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample (NIS) in the United States, severe burns represented 4.4% of all burn admissions, with a mortality rate of about 17.8%. Severe burns are associated with increased inflammation that can cause prolonged cardiac dysfunction and affect both metabolic and catabolic mechanisms within the body. This chronic inflammatory process alters the blood brain barrier, contributing to cognitive impairment and structural alterations within the brain. These biological changes, alongside numerous psychological factors, can contribute to the development of psychiatric disorders following trauma. 2 Although medical burn care has significantly improved, reducing both deaths and hospitalizations related to burn injuries, such patients require holistic treatment to address the physical, psychological, and social results of their burn injuries.1,3

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) characterizes Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a psychiatric condition consisting of intrusive thoughts, avoidant behaviors, and negative effects in both cognition and mood for at least one month. 2 It can develop after an individual experiences or witnesses a life-threatening and traumatic event. Burn injuries can be very distressing due to the nature of the injury, lengthy treatment course, extended period of hospitalization, follow-up care, and irreversible damage leading to body dissatisfaction and appearance concerns. 4 Studies have shown that the development of both PTSD and pain in burn survivors arise due to increased levels of cortisol, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and fatigue. 5 Psychological factors such as the trauma of the injury itself, the emotional stress of prolonged treatment, the impact on body image, and the social isolation during recovery also play significant roles.6,7 These elements of negative thought patterns, mood disturbances, and metabolic imbalances may persist during treatment or for months afterwards. 8 Approximately 2–30% of burn survivors will go on to develop acute stress disorder, with 40% of survivors developing PTSD three to six months post-burn injury. 7 PTSD also shares comorbidity with many other mood disorders and psychiatric illnesses. 9 Evidence suggests that patients with PTSD are more likely to have depression and anxiety than those without it. 2 Burn survivors can develop depression due to the delay in returning to their normal life activities, experience anxiety about how they may be perceived regarding their injuries, and risk re-experiencing the traumatic event in similar situations.10–14 The presence of these comorbidities is influenced by factors such as personality characteristics, coping mechanisms, social support, premorbid psychopathology, as well as demographic and social factors. 3

Opioids are common analgesics used to treat various categories of pain within hospitals and clinics. They are often used in burn pain management in all phases of care such as in intensive care units, perioperative periods, and outpatient settings. 15 Although opioids are quite effective in reducing pain, they also risk addiction, misuse, and dependence as well. 16 Like depression and anxiety, PTSD is also highly comorbid with substance use disorders, with burn patients at an increased risk for developing psychiatric illnesses and substance abuse compared to the general population.4,15 A retrospective study conducted in 2023 evaluated the risk of developing a mental health or psychiatric illness in severe burn patients diagnosed with opioid use disorder. Approximately 80% of burn patients with opioid disorder also had a mental health disorder, with 30% diagnosed with substance abuse disorder. 15 This result establishes the risk of developing an opioid use disorder in burn patients experiencing pain, even without the presence of psychiatric illness. This study sought to quantify the association of PTSD and increased opioid usage and chronic pain syndrome in severe burn patients using a multi-institutional database (TriNetX). The authors hypothesized that severe burn patients with PTSD will have increased risk of chronic pain syndrome, demonstrated through increased opioid use. Additionally, the authors posited that the presence of PTSD would be associated with an increased risk of complications, compared to burn patients without PTSD. The results of our study may be vital in assessing PTSD as a potential risk factor for opioid misuse in burn patients.

Methods

Data source

A retrospective case-control analysis was conducted using the TriNetX Research Diamond Network to identify patients who had undergone severe burns, as defined by specific International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. At the time of the study (2 May 2024), the TriNetX Research Diamond Network included 92 healthcare organizations in the United States and more than 213.1 million patients. TriNetX offers access to deidentified patient data extracted from electronic medical records, including information from inpatient visits, outpatient visits, and pharmacy records. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) because it is an analysis of secondary data without individual identifiers.

Inclusion criteria

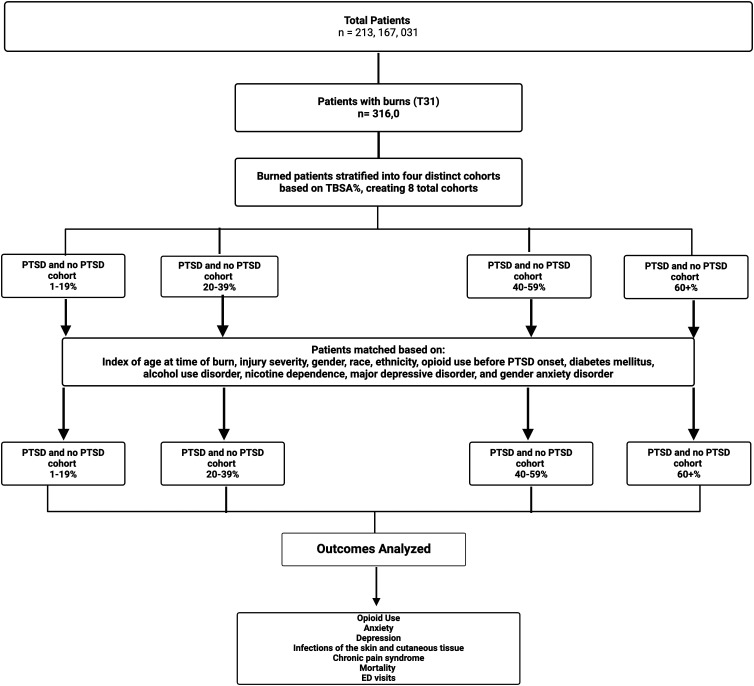

Two distinct cohorts were established for this study: Cohort A (control group), comprising burned patients without PTSD, and Cohort B (case group), consisting of burned patients diagnosed with PTSD (ICD 10 code: F43.1). PTSD diagnosis required symptoms meeting diagnostic criteria continuing for at least one month following a burn injury, as per DSM-5 guidelines. As a result, we set the index time of incidence to at least one-month post-burn injury. Both cohorts were stratified based on the severity of the injury by the percent of total body surface area burned (TBSA%) (ICD code T31), resulting in the formation of eight distinct groups of burn patients without (A) and with (B) PTSD : 1–19%TBSA (1A and 1B) (ICD code T31.0 - T31.1), 20–39% TBSA (2A and 2B) (T31.2-T31.3), 40–59% TBSA (3A and 3B) (T31.4-T31.5), and 60+% TBSA (4A and 4B) (T31.6 - T31.9). Next, we conducted propensity score matching methods to match those in Cohort A with those in Cohort B based on the following criteria: age at time of burn, injury severity, gender, race, ethnicity, opioid use before PTSD onset, diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, nicotine dependence, major depressive disorder, and general anxiety disorder. Figure 1 provides a flow diagram outlining the process of producing the TriNetX database for our study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the outcomes analyzed in burn patients by presence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), stratified by percentage of total body surface area burned (TBSA%).

Variables

The main aim of this research was to compare the likelihood of opioid use within 60 days following a severe burn injury among patients diagnosed with PTSD (Cohort B) with those without PTSD (Cohort A). Opioid use risk was operationalized in this study by the issuance of an opioid prescription. Additionally, our study examined five other burn-related and PTSD-related outcomes: the likelihood of developing chronic pain syndrome (ICD code G89.4), depression (ICD code F32), anxiety (ICD code F40-F48), and emergency department presentation (Current Procedural Terminology code 1013711). Additional comorbidities were included in our study based on previous studies of burn injury patients with PTSD (anxiety, depression, emergency department presentations, and chronic pain syndrome).17,18

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using TriNetX software (TRINETX, LLC, Cambridge, MA), which employs JAVA, R, and Python programming languages. Measures of association, such as risk ratios, risk differences with t-tests, and odds ratios, were computed, each accompanied by its respective 95% confidence interval (CI). Online Supplementary Tables were generated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Statistical significance was deemed as p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 333,013 burn patients without the diagnosis of PTSD in 92 healthcare organizations (HCOs) were identified, with a mean age of 43 ± 23 years. Concurrently, a total of 16,974 burn patients with the diagnosis of PTSD across 92 HCOs were identified, with a mean age of 46 ± 16 years. After matching, cohorts consisting of those with 1–19% TBSA (cohorts mild burns with and without PTSD) each contained 15,966 patients; 20–39% TBSA (cohorts moderate burns with and without PTSD) each contained 810 patients; 40–59% TBSA (cohorts severe burns with and without PTSD) each contained 378 patients; and 60+% TBSA (cohorts critical burns with and without PTSD) each contained 333 patients. Mild burns without PTSD and mild burns with PTSD had 306,068 and 16,004 patients, respectively, with an incidence of PTSD of 4.96%.

Moderate burns without PTSD and moderate burns with PTSD had 8719 and 829 patients, respectively, with an incidence of PTSD of 8.68%. Severe burns without PTSD and severe burns with PTSD had 2806 and 392 patients, respectively, with an incidence of PTSD of 12.26%. Lastly, critical burns without PTSD and critical burns with PTSD Cohorts had 2878 and 349 patients, respectively, with an incidence of PTSD of 10.81%. Demographics of each cohort after matching is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics after matching.

| Mild burns without PTSD | Mild burns with PTSD | Moderate burns without PTSD | Moderate burns with PTSD | Severe burns without PTSD | Severe burns with PTSD | Critical burns without PTSD | Critical burns with PTSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients before match | 306,068 | 16,004 | 8719 | 829 | 2806 | 392 | 2878 | 349 |

| Number of patients after match | 15,966 | 15,966 | 810 | 810 | 378 | 378 | 333 | 333 |

| Incidence of PTSD | 4.96% | 8.68% | 12.26% | 10.81% | ||||

| Mean age in years (SD) | 40.1 ± 16.4 | 39.2 ± 15.8 | 40.3 ± 18.5 | 39 ± 17.4 | 38.7 ± 19.3 | 39.3 ± 16.4 | 36.4 ± 20 | 39.7 ± 14.5 |

| Male | 38.8% | 38.3% | 54.3% | 53.7% | 58.9% | 59.8% | 60.1% | 57.1% |

| Female | 61.2% | 61.6% | 45.6% | 46.2% | 41.1% | 40.2% | 39.9% | 42.9% |

| White | 23.4% | 22.7% | 21.7% | 18.6% | 24.6% | 22.8% | 22.2% | 23.1% |

| Black | 3.9% | 4.1% | 2.6% | 3.5% | 5.6% | 6.1% | 4.5% | 3.3% |

| Asian | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Other Races | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Unknown Races | 72.6% | 73.1% | 75.7% | 77.9% | 69.8% | 71.1% | 70.3% | 70.6% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 27.7% | 27.0% | 24.3% | 22.8% | 29.1% | 28.0% | 23.4% | 25.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.8% | 2.1% | 1.2% | 1.7% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Unknown Ethnicity | 70.5% | 70.9% | 74.5% | 75.5% | 68.3% | 69.4% | 73.6 | 71.8 |

Note: A is the Control group (without PTSD) and B is the Case Group (with PTSD).

PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; SD: standard deviation.

Table 2a provides the comparison of likelihood of having complications and comorbidities between the case and control groups with lower burn severity (1–19% and 20–39% TBSA). In mild burns with PTSD (1–19% TBSA), there were significantly elevated rates of opioid use (20.6% vs. 17.6%), chronic pain syndromes (2.8% vs. 1.647%), depression (14.9% vs. 6.7%), anxiety (41.7% vs. 10.8%), emergency department visits (31.4% vs. 24.5%), and mortality (1.058% vs. 0.676%) compared to mild burns without PTSD, respectively (p < 0.05). In moderate burns with PTSD (20–39% TBSA), there were significantly higher rates of opioid use (24.3% vs. 18.9%), chronic pain syndromes (4.2% vs. 1.2%), depression (11.5% vs. 5.3%), anxiety (43.8% vs. 7.4%), and emergency department visits (19.0% vs. 13.3%) compared to moderate burns without PTSD (p < 0.05). Additionally, moderate burns with PTSD had a higher risk for mortality (1.9% vs. 1.6%), however, it was not deemed significant (p = 0.5740).

Table 2.

Comparison of comorbidities and complications associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Burns.

Table 2a. Comparisons in cohorts with less severe burns.

| 1–19% TBSA | Mild burns without PTSD | Mild burns with PTSD | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid use | 2809 (17.6%) | 3283 (20.6%) | 1.170 | (1.123, 1.217) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic pain syndrome | 263 (1.647%) | 447 (2.8%) | 1.700 | (1.589, 1.811) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 1070 (6.7%) | 2393 (14.9%) | 2.223 | (2.120, 2.326) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety | 1731 (10.8%) | 6656 (41.7%) | 3.861 | (3.785, 3.937) | <0.0001 |

| Emergency department visits | 3919 (24.5%) | 5007 (31.4%) | 1.281 | (1.215, 1.347) | <0.0001 |

| Mortality | 108 (0.676%) | 169 (1.058%) | 1.565 | (1.300, 1.830) | 0.0002 |

| 20–39% TBSA | Moderate burns without PTSD | Moderate burns with PTSD | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

| Opioid use | 153 (18.9%) | 197 (24.3%) | 1.285 | (1.220, 1.350) | 0.0049 |

| Chronic pain syndrome | 10 (1.2%) | 34 (4.2%) | 3.50 | (3.454, 3.546) | 0.0002 |

| Depression | 43 (5.3%) | 93 (11.5%) | 2.169 | (2.066, 2.272) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety | 60 (7.4%) | 355 (43.8%) | 5.918 | (5.841, 5.995) | <0.0001 |

| Emergency department visits | 108 (13.3%) | 154 (19.0%) | 1.428 | (1.164, 1.692) | 0.0019 |

| Mortality | 13 (1.6%) | 16 (1.9%) | 1.187 | (1.122, 1.252) | 0.5740 |

TBSA: total body surface area burned.

Table 2b shows the relative likelihood of having complications and comorbidities between the case and control groups with higher burn severity (40–59% and 60+% TBSA). In severe burns with PTSD (40–59% TBSA), there were significantly higher rates of opioid use (19.3% vs. 18.8%), depression (17.5% vs. 4.8%), anxiety (43.4% vs. 6.9%), and emergency department visits (15.9% vs. 9.3%) compared to severe burns without PTSD (p < 0.05). Additionally, severe burns with PTSD had a higher risk for chronic pain syndrome (4.8% vs. 2.6%), however, it was not deemed significant (p = 0.1234). In critical burns with PTSD (60%+ TBSA), there were significantly higher rates of opioid use (46.2% vs. 18.3%), chronic pain syndromes (6.9% vs. 3.0%), depression (17.1% vs. 3.9%), anxiety (40.8% vs. 10.8%), and emergency department visits (19.2% vs. 9.6%) compared to critical burns without PTSD (p < 0.05).

Table 2b.

Comparisons in cohorts with more severe burns.

| 40–59% TBSA | Severe burns without PTSD | Severe burns with PTSD | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid use | 71 (18.8%) | 73 (19.3%) | 1.026 | (0.766, 1.38) | 0.0453 |

| Chronic pain syndrome | 10 (2.6%) | 18 (4.8%) | 1.846 | (0.842, 3.848) | 0.1234 |

| Depression | 18 (4.8%) | 66 (17.5%) | 3.645 | (2.221, 6.053) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety | 26 (6.9%) | 164 (43.4%) | 6.289 | (4.278, 9.301) | <0.0001 |

| Emergency department visits | 35 (9.3%) | 60 (15.9%) | 1.709 | (1.159, 2.536) | 0.0041 |

| Mortality | 10 (2.6%) | 10 (2.6%) | 1.0 | (0.421, 2.375) | 1.000 |

| 60%+ TBSA | Critical burns without PTSD | Critical burns with PTSD | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

| Opioid use | 61 (18.3%) | 154 (46.2%) | 2.524 | (2.139, 4.650) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic pain syndrome | 10 (3.0%) | 23 (6.9%) | 2.30 | (1.112, 4.757) | 0.0203 |

| Depression | 13 (3.9%) | 57 (17.1%) | 4.384 | (2.448, 7.854) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety | 36 (10.8%) | 136 (40.8%) | 3.777 | (2.704, 5.278) | <0.0001 |

| Emergency department visits | 32 (9.6) | 64 (19.2%) | 2.012 | (0.873, 3.069) | 0.0002 |

| Mortality | 14 (4.2%) | 10 (3.0%) | 0.714 | (0.322, 1.585) | 0.4056 |

TBSA: total body surface area burned.

Discussion

This retrospective national database analysis presents a novel examination of burn-related comorbidities associated with PTSD, particularly those related to chronic pain/opioid use and other mental health problems. Our study sought to quantify the association of PTSD and increased opioid usage and chronic pain syndrome in severe burn patients using a multi-institutional database (TriNetX). We hypothesized that severe burn patients with PTSD would have an increased risk of chronic pain syndrome, demonstrated through increased opioid use. Additionally, we posited that the presence of PTSD would be associated with an increased risk of complications compared to burn patients without PTSD. Our results mostly support these hypotheses. Significant differences in various complications and comorbidities were observed between patients with and without PTSD within each burn severity cohort. All patients in each cohort with PTSD had a significantly higher risk of opioid use and chronic pain syndrome than their corresponding patient without PTSD cohort. Interestingly, only patients in the 60%+ TBSA cohort had a markedly higher risk ratio of opioid use compared to all other cohorts. This finding suggests that due to the range of TBSA% in those categorized as ‘severe’, further stratification in injury severity may be warranted.

Previous studies of PTSD have highlighted an elevated prevalence and response to pain within burn injury patients. 19 Studies have demonstrated not only a higher incidence of chronic pain in those with PTSD but also a heightened perception of pain compared to healthy individuals.20,21 With a heightened perception of pain, individuals with various psychological conditions such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, or difficulties coping with pain were significantly more likely to use opioids one to two months after surgery.22–24 Catastrophic thinking, a cognitive style characterized by an exaggerated negative mindset about pain and its consequences, has been shown to exacerbate pain perception and contribute to chronic pain. 25 These findings provide potential insight into why there is a significantly increased likelihood of using opioids in patients with PTSD across all cohorts.

PTSD and chronic pain syndrome frequently co-occur and have been shown to work synergistically in trauma victims, leading to greater individual effects compared to when either condition presents alone. 26 This effect supports our study's findings that the risk of developing chronic pain syndrome is increased with comorbid PTSD and highlights the need for studies further elucidating observed relationship between comorbid PTSD and chronic pain syndrome to mitigate their combined effects. Understanding this relationship is crucial for developing interventions that address both conditions simultaneously.

Although burns are traumatic, few studies have examined PTSD as a surgical comorbidity. One study conducted using the TriNetX database found that the presence of PTSD following burns increased the risk of morbidity, calling for early screening and preventative care in burn patients with comorbid PTSD in order to reduce morbidity. 2 Our study adds to the existing literature by further investigating the effect of PTSD in severe burn patients, specifically its link to opioid use in affected patient populations. As one of the mainstays of analgesia in the treatment of severe burns, opioids unfortunately are prone to abuse and come with an array of unwanted side effects, such as nausea, respiratory depression, and delirium. 27 Our study found that all PTSD cohorts had an increased risk of opioid use compared to the patients without PTSD in counterpart cohorts, a finding supported by studies associating PTSD and opioid dependence.28,29 The traditional medical model assumes a direct correlation between trauma and pain or risk. 19 However, evidence suggests that individuals with psychological comorbidities may have difficulties coping with or managing pain with minor traumatic events, leading to increased hospitalization and emergency department visits.20,26 Although the data on PTSD is limited, these findings suggest that burn patients with PTSD may face additional challenges in their recovery process. Our study underscores the importance of this knowledge when prescribing opioids to patients.

One of the strengths of our study lies in the use of a national database, which enabled the analysis of 213.1 million patients and facilitated the attainment of a sufficiently large sample size. This size allowed for propensity-matched cohorts based on age at time of burn, injury severity, gender, race, ethnicity, opioid use before PTSD onset, and the presence of diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, nicotine dependence, major depressive disorder, and general anxiety disorder. Previous studies highlighted the value of using TriNetX to analyze patient records and prescription data, underscoring the credibility of this approach with testing PTSD as an independent factor for opioid use in burn patients.21–23,30

In addition to exploring the relationship between mental health challenges, such as PTSD, and pain management in burn patients, it is essential to consider the diverse factors that contribute to the complexity of PTSD outcomes. Factors such as personal histories, previous exposure to trauma, and psychosocial elements, including support systems and coping strategies, significantly shape the development and severity of PTSD following burn injuries. 17 Additionally, existing psychological conditions and an individual's cognitive interpretation of the traumatic experience play critical roles in influencing PTSD symptoms and response to treatment.31,32 Recognizing these various influences is crucial for developing tailored psychosocial interventions that address the unique needs of burn patients with PTSD, thereby improving their rehabilitation and long-term recovery. A thorough assessment of these factors can empower healthcare providers to enhance the quality of psychosocial care provided to burn patients, aligning with the holistic approach emphasized in our conclusion. 33

TriNetX does contain some limitations. First, TriNetX lacks patient-level data. TriNetX contains encounter-level health records, pharmacy records, and insurance billing data to detect the presence or absence of specific medical, surgical, and prescription codes. However, this patient data is de-identified, thereby restricting researchers from accessing the precise relationships between variables. While previous studies indicated an increased risk of chronic pain among patients with PTSD and burn injuries, the identification of variables like ‘diagnosis of chronic pain syndrome (yes or no)’ in our study merely signifies the presence of the diagnostic code, without specifying pain levels from 0 to 10.2,22 Our decision to include this variable aimed to assess the prevalence of pre-existing chronic pain, particularly considering the significant number of patients in both cohorts who were already using baseline opioid analgesics. Another limitation is that we lacked precise information on the quantities of opioid analgesics prescribed versus consumed by individual patients. Such information is not available. Lastly, TriNetX represents populations containing between 1 and 9 patients as ‘10’ patients, which may have affected the significance of outcomes observed among the PTSD cohort. In both Table 1 and Table 2, instances where a few patientsin the cohort experienced postoperative complications resulted in their representation as ‘10’ patients. Despite these limitations, the use of this database offers compelling evidence that warrants further exploration into patient-level data, allowing for more precise determination of the causal relationships underlying postoperative opioid usage and other outcomes. Additionally, prospective studies are needed to further elucidate the temporal relationships and causal mechanisms underlying the observed associations between PTSD, opioid use, and chronic pain syndrome in burn patients.

Conclusion

Our study utilized the TriNetX database to examine associations between PTSD and adverse outcomes in severely burned patients. PTSD was consistently linked to increased opioid use across all levels of burn severity. Patients with PTSD also exhibited higher rates of chronic pain syndrome, depression, anxiety, and emergency department visits. The risk of mortality between cohorts varied based on burn injury severity. These findings underscore the importance of identifying and addressing PTSD as a significant factor in managing severe burn injuries. Healthcare professionals should adopt comprehensive approaches that include psychological screening, early intervention, and tailored pain management strategies to mitigate these risks. Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms driving these associations and to optimize care for this vulnerable patient population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sbh-10.1177_20595131241288298 for Examining the role of post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic pain and opioid use in burn patients: A multi-cohort analysis by Joshua Lewis, Lornee C Pride, Shawn Lee, Ogechukwu Anwaegbu, Nangah N Tabukumm, Manav M Patel and Wei-Chen Lee in Scars, Burns & Healing

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 TR001439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors thank Sarah T. Smith, PhD, for her assistance with editing the manuscript in preparation for submission. Additionally, we would like to thank Dr Norma Perez and the Center of Excellence for Professional Advancement and Research with their guidance and support. The authors would like to thank BioRender.com for creating Figure 1 for our manuscript.

Author biographies

Joshua Lewis is a second-year medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine. He is interested in plastic surgery research. He particularly has an interest in examining the effects of disparities at the medical education level and addressing disparities in plastic surgery. In plastic surgery, he has a grand interest in burns and cosmetic surgeries.

Lornee Pride is a second-year medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine. She is interest in neurosurgery, neurological psychological conditions, healthcare disparities, and epilepsy.

Shawn Lee is a second-year medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine. He has an interest in dermatology, Mohs surgery, and burns.

Ogechukwu Anwaegbu is a third-year medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine. She is interested in anesthesiology, health equity, social media analysis, and ear/nose/throat surgery.

Nangah N Tabukum is a third-year medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of medicine. She is interested in anesthesiology research and health disparities.

Manav M Patel is a second-year medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine. He has an interest in plastic surgery, general surgery, and burns.

Wei-Chen Lee is an assistant professor at the Department of Family Medicine and the founding member of the Lab to Eliminate Disparities at the University of Texas Medical Branch. Her research is focused on health disparities that disproportionately affect aging population, racial minorities, and rural adults.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded in part by the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), through its grant to the UTMB Center of Excellence for Professional Advancement and Research (grant number 1 D34HP49234-01-00). HRSA had no role in decisions related to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Joshua Lewis https://orcid.org/0009-0001-4785-2011

Ogechukwu Anwaegbu https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8776-5941

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

How to cite this article

Joshua L, Lornee CP, Shawn L, Ogechukwu A, Nangah NT, Manav MP and Wei-Chen L. Examining the role of posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic pain and opioid use in burn patients: A multi-cohort analysis. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 10, 2024. DOI: 10.1177/20595131241288298.

References

- 1.Ellison DL. Burns. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2013; 25: 273–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iglesias N, Campbell MS, Dabaghi E, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in burn patients – A large database analysis. Burns 2024; 50: 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attoe C, Pounds-Cornish E. Psychosocial adjustment following burns: an integrative literature review. Burns 2015; 41: 1375–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang YK, Su YJ. Burn severity and long-term psychosocial adjustment after burn injury: the mediating role of body image dissatisfaction. Burns 2021; 47: 1373–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim TD, Lee S, Yoon S. Inflammation in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): a review of potential correlates of PTSD with a neurological perspective. Antioxidants 2020; 9: 07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie C, Hu J, Cheng Yet al. et al. Researches on cognitive sequelae of burn injury: current status and advances. Front Neurosci 2022; 16: 1026152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boersma-van Dam E, Engelhard IM, van de Schoot R, et al. Bio-Psychological Predictors of Acute and Protracted Fatigue After Burns: A Longitudinal Study. Front Psychol 2022 Jan 24; 12: 794364. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.794364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health (US) NI of, Study BSC. Information about mental illness and the brain. In: NIH Curriculum Supplement Series, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20369/ (2007, accessed 4 July 2024). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr 2014; 59: 460–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treatment (US) C for SA. A review of the literature. In: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207192/ ( 2014, accessed 4 July 2024). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treatment (US) C for SA. Understanding the impact of trauma. In: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/ ( 2014, accessed 4 July 2024). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fauerbach JA, McKibben J, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Psychological distress after major burn injury. Psychosom Med 2007; 69: 473–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeve J, James F, McNeill R. Providing psychosocial and physical rehabilitation advice for patients with burns. J Adv Nurs 2009; 65: 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards RR, Smith MT, Klick B, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety as unique predictors of pain-related outcomes following burn injury. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med 2007; 34: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah NR, Mao RMD, Coleoglou Centeno AA, et al. Opioid use disorder in adult burn patients: implications for future mental health, behavioral and substance use patterns. Burns 2023; 49: 1073–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Academies of Sciences E, Division H and M, Policy B on HS , et al. Pain management and the intersection of pain and opioid use disorder. In: Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. National Academies Press (US), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458655/ ( 2017, accessed 4 July 2024)) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lodha P, Shah B, Karia S, De Sousa A. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Ptsd) following burn injuries: a comprehensive clinical review. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 2020; 33: 276–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trudgill DIN, Gorey KM, Donnelly EA. Prevalent posttraumatic stress disorder among emergency department personnel: rapid systematic review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2020; 7: 7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farre A, Rapley T. The new old (and old new) medical model: four decades navigating the biomedical and psychosocial understandings of health and illness. Healthcare 2017; 5: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onwumere J, Stubbs B, Stirling M, et al. Pain management in people with severe mental illness: an agenda for progress. Pain 2022; 163: 1653–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wermine K, Gotewal S, Song J, et al. Patterns of antibiotic administration in patients with burn injuries: a TriNetX study. Burns J Int Soc Burn Inj 2024; 50: 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konings B, Villatoro L, Van den Eynde J, et al. Gastrointestinal syndromes preceding a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease: testing Braak’s hypothesis using a nationwide database for comparison with Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular diseases. Gut 2023; 72: 2103–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeJesus J, Shah NR, Franco-Mesa C, et al. Risk factors for opioid use disorder after severe burns in adults. Am J Surg 2023; 225: 400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Vries V, de Jong AEE, Hofland HWCet al. et al. Pain and posttraumatic stress symptom clusters: a cross-lagged study. Front Psychol 2021; 12: 669231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flink IL, Boersma K, Linton SJ. Pain catastrophizing as repetitive negative thinking: a development of the conceptualization. Cogn Behav Ther 2013; 42: 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gasperi M, Afari N, Goldberg J, et al. Pain and trauma: the role of criterion A trauma and stressful life events in the pain and PTSD relationship. J Pain 2021; 22: 1506–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jamal S, Shaw M, Quasim T, et al. Long term opioid use after burn injury: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth 2024; 132: 599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Martínez AE, Reyes-Pérez Á, Serrano-Ibáñez ER, et al. Chronic pain, posttraumatic stress disorder, and opioid intake: A systematic review. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7: 4254–4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fareed A, Eilender P, Haber M, et al. Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Opiate Addiction: A Literature Review. J Addict Dis 2013; 32: 168–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iglesias NJ, Prasai A, Golovko G, et al. Retrospective outcomes analysis of tracheostomy in a paediatric burn population. Burns J Int Soc Burn Inj 2023; 49: 408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes JP, VanElzakker MB, Shin LM. Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: a review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Front Integr Neurosci 2012; 6: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann SK, Marwaha R, Torrico TJ. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559129/ (2024, accessed 4 July 2024). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shokre ES, Mohammed SEM, Elhapashy HMM, et al. The effectiveness of the psychosocial empowerment program in early adjustment among adult burn survivors. BMC Nurs 2024; 23: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sbh-10.1177_20595131241288298 for Examining the role of post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic pain and opioid use in burn patients: A multi-cohort analysis by Joshua Lewis, Lornee C Pride, Shawn Lee, Ogechukwu Anwaegbu, Nangah N Tabukumm, Manav M Patel and Wei-Chen Lee in Scars, Burns & Healing