Abstract

The objective of this study was to describe characteristics of effective pediatric primary care interventions that focused on parenting education about healthy parent-child relationships. A scoping review of 4 electronic databases searched for related systematic reviews published in English from January 2000 to June 2023. The full texts of 14 systematic reviews were evaluated by 2 independent reviewers and used to identify 25 unique parenting interventions of which 21 improved outcomes more than the comparison group. Results demonstrate that a range of low to high intensity interventions can improve parent-child relationships, and many of these also improve parent mental health and child behaviors. By contrast, multi-component interventions were needed to improve child development and reduce injuries. Interventions that decreased child injuries focused on reducing parental stress through professional support, access to community resources, and mental health information. Future research is needed on pediatric primary care parenting education that incorporates responsive parenting, includes patient samples with ACEs, and measures physical health outcomes or biomarkers.

Keywords: primary health care, pediatrics, social determinants of health, behavioral health, prevention, quality improvement

Introduction

Pediatric primary care providers are the only professionals who regularly meet with children and their families from infancy through adolescence. Well-child care in particular is designed to focus on the prevention of disease, as well as the promotion of health and development. However, it is imperative to prioritize effective interventions given the limited amount of time for well-child care visits. 1

Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) may be an important topic for pediatricians to prioritize. As defined by the original CDC study, ACEs include family-relationship risk factors such as child maltreatment (physical, verbal, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect) and household challenges (mental illness, substance abuse, intimate partner violence, incarceration, divorced, or separated parents). 2 Research shows that exposure to 1 ACE increases the odds of additional ACEs, there is a dose-response relationship between ACEs and poor health, and ACEs increase risk of a wide range of physical, mental, and social problems.2 -6 In children, studies suggest that ACEs increase risk of behavior problems, developmental delays, somatic complaints, sleep disruption, injuries, unhealthy weight, asthma, and substance use.7 -12

A separate literature shows that safe, stable, and nurturing home environments promote optimal health and development. For example, recent reviews show that positive and collaborative parent-child relationships improve child mental health, including reduced depression, 13 reduced aggression, 14 and improved self-regulation. 15 There is also evidence that the quality of parent-child relationships can impact physical health, such as inflammatory responses in children with asthma, 16 glycemic control in patients with diabetes, 17 and medical adherence across chronic health conditions. 18 Studies of children with ACEs suggest that interventions that focus on promoting responsive parenting may affect cortisol regulation, brain development, epigenetic regulation, and autonomic nervous system functioning. 19 In consideration of this literature, the American Academy of Pediatrics encourages universal interventions to promote relational health. 20

Since interventions that improve relational health may reduce the negative consequences of ACEs, many pediatricians are searching for feasible, evidence-based parenting advice, materials, and programs to implement in their clinics. The goal of this review was to identify and present parenting interventions in such a way that pediatricians can make an informed choice about what to implement and with what resources. Therefore, our specific aims were: (1) To identify interventions that focused on parenting education about healthy parent-child relationships, involved a pediatric primary care practice, and measured child or parent-child outcomes; (2) To describe characteristics of effective interventions; and (3) To offer guidance regarding strategies to improve relational health and related outcomes.

Methods

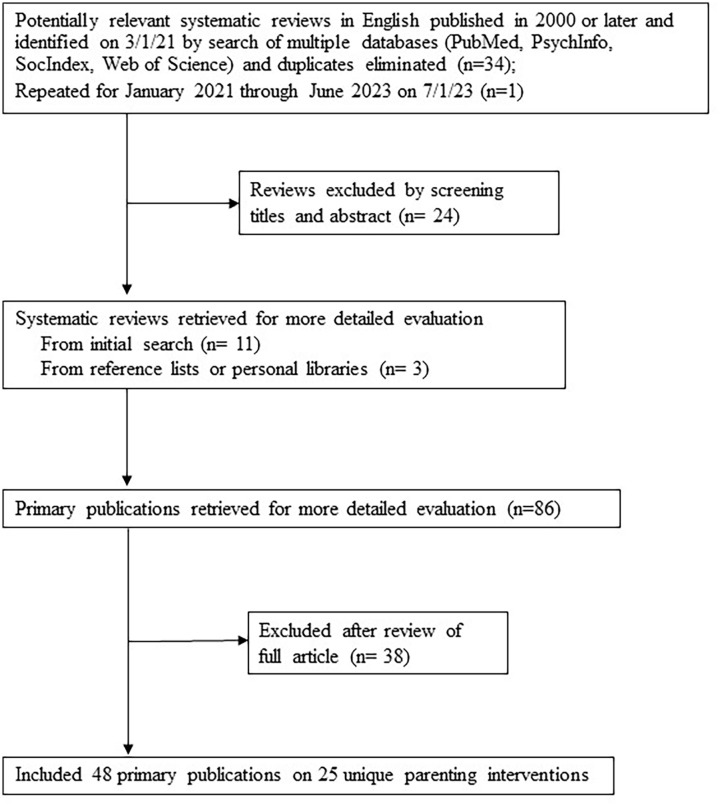

This review followed the reporting guidelines for the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR). 21 A flow diagram of our literature search is illustrated in Figure 1. In March 2021, we searched for systematic reviews of parenting education by pediatric providers published in English from January 2000 to December 2020. Key search terms were “Intervention” AND (“Parenting” or “Parent-child relations”) AND (“Pediatric primary care” or “Primary health care”). The search was performed in PubMed, PsychInfo, SocIndex and Web of Science. In July 2023, this search was repeated from January 2021 through June 2023. Systematic reviews were included if they contained primary studies of parenting education about healthy parent-child relationships in a pediatric primary care setting.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search.

The full-text of the systematic reviews were then evaluated by 2 independent reviewers. Primary studies were included if they (1) evaluated an intervention that focused on parenting education about healthy parent-child relationships, (2) involved a pediatric primary care practice (see Table 1 column “pediatricians” for specific types of involvement); and (3) measured child or parent-child outcomes. All studies of parenting education through pediatric primary care were included, regardless of whether child ACEs were measured. Studies that did not isolate the impact of parenting education but combined with other interventions (such as pharmacotherapy) were excluded. 22 In addition, descriptive studies and pilot work that did not report outcomes on a comparison group or did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between groups due to low power were excluded.23,24

Table 1.

Summary of Pediatric Parenting Intervention Components.

| Outcome | Intervention/age group (in order by age group) | Pediatricians | Nurses or other clinic staff | Specialist | Parent coaches | Community health workers | Nurse or other home visitors | Phone coaching | Parent groups | Written handout or book | Videos or website | Books for child | Toys for child | Community resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight gain | THRIVE/0-6 months 25 | WCC | P | |||||||||||

| Injury reduction | Queensland Home Visits/0-4 months with 1 or more ACEs 26 | Team meetings | SW | √ | √ | |||||||||

| SEEK/0-5 years screened for ACEs27,28 | Screen home | SW | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Minnesota Violence Prevention/7-15 years with behavior concerns 29 | Screen MH/refer | MH | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Child development | Touchpoints/0-18 months 30 | WCC | √ | SW | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Caribbean Parenting/3-18 months 31 | WCC | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Social-emotional screening/6-36 months 32 | Referrals | √ | P | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| VIP/0-3 years, maternal low education or income33 -36 | WCC | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Child behavior | Building Blocks/0-3 years, maternal low education or income 37 | WCC | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| VIP/0-3 years, maternal low education or income 37 | WCC | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Healthy Steps/0-3 years38 -40 | WCC | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Parenting Matters/2-5 years with parent discipline concern 41 | Referrals | P | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| PriCARE/2-6 years with behavior concerns42,43 | Co-located MH | MH | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| DOCC/5-12 years with behavior concerns 44 | Team meetings | SW | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Primary Care Triple P/2-12 years with behavior concerns45 -48 | Co-located group | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Minnesota Violence Prevention/7-15 years with behavior concerns 29 | Screen MH/refer | MH | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Parent-child | Queensland Home Visits/0-4 months with 1 or more ACEs 26 | Team meetings | SW | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Well-Child Care Counseling, North Carolina, 0-6 months49,50 | WCC + responsiveness to infant social behaviors | |||||||||||||

| Finger puppets/2-6 months51,52 | Pediatric waiting room | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Baltimore Home Visits/0-18 months, maternal drug-abuse (ACE) 53 | Team meetings | P | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Well-child care counseling, New York, 0-18 months54,55 | WCC | SW or P | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Caribbean Parenting/3-18 months 31 | WCC | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Toddlers without Tears, 8-15 months 56 | WCC | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Care for Development, 0-24 months 57 | Development interview | |||||||||||||

| Building Blocks/0-3 years, maternal low education or income58 -60 | WCC | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| VIP/0-3 years maternal low education or income35,58 -62 | WCC | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Healthy Steps/0-3 years38 -40 | WCC | D | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| SEEK/0-5 years screened for ACEs27,28 | Screen home | SW | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Play Nicely, 1-5 years63 -65 | WCC + discipline | √ | ||||||||||||

| PriCARE/2-6 years with behavior concerns42,43 | Co-located MH | MH | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Primary Care Triple P/2-12 years45 -48 | Co-located group | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| DOCC/5-12 years with behavior concerns 44 | Team meetings | SW | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Minnesota Violence Prevention/7-15 years with behavior concerns 29 | Screen MH/refer | MH | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Abbreviations: D, developmental specialist; DOCC, Doctor Office Collaborative Care.; MH, mental health; P, psychologist; PriCARE, Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement in Primary Care; SEEK, Safe Environment for Every Kid; SW, social worker; THRIVE, Teaching Healthy Responsive parenting during Infancy to promote Vital growth and rEgulation; VIP, Videotape Interaction Project; WCC, well-child care.

Extracted data included key components of the intervention; research design; child physical, behavioral, and developmental outcomes; parent-child relationship and parent mental health outcomes. Disagreements among reviewers were discussed and resolved by consensus. For interventions with 2 or more publications, emails were sent to first authors to validate the accuracy of intervention descriptions and outcomes. Results were collated by statistically significant outcomes and qualitatively analyzed for patterns across intervention components and information content. In addition, a 2 × 2 matrix was used to stratify interventions by the extent to which pediatric clinical staff were involved in the intervention and the extent to which additional professionals were needed.

Results

We identified 35 systematic reviews of which 11 met inclusion criteria. Three additional systematic reviews were identified by reviewing reference lists of the first 11 reviews or personal libraries.66 -79 From these 14 systematic reviews, a total of 25 unique parenting education interventions met inclusion criteria. Four of these parenting interventions did not improve outcomes more than the comparison group.80 -83 Table 1 provides a summary of intervention components for the remaining 21 interventions, Table 2 provides a summary of information content, and Figure 2 provides a contrast and comparison of interventions. Three interventions were delivered specifically to pediatric patients with ACEs,26,27,53 5 were delivered to pediatric patients with behavioral concerns,29,41,44,45,52 2 were delivered to low education or income families,34,60 and the remaining eleven were delivered to general pediatric populations. Additional information on all the interventions can be found in the Appendix.

Table 2.

Summary of Pediatric Parenting Intervention Information.

| Outcome | Intervention/age group (in order by age group) | Caregiver | 1° Care | Behavioral approach | Relational approach | Peers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent mental health and stress | Parent substance use or violence | Preventative health care | Child development | Child behaviors | Positive parenting/praising | Discipline | Responsive parenting/showing love | Talking/listening | Playing | Emotion regulation | Peer social skills | Exposure to violence | ||

| Weight gain | THRIVE/0-6 months 25 | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Injury reduction | Queensland Home Visits/0-4 months with 1 or more ACEs 26 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| SEEK/0-5 years screened for ACEs27,28 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Minnesota Violence Prevention/7-15 years with behavior concerns 29 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Child development | Touchpoints/0-18 months 30 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Caribbean Parenting/3-18 months 31 | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Social-emotional screening/6-36 months 32 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| VIP/0-3 years, maternal low education or income33 -36 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Child behavior | Building Blocks/0-3 years, maternal low education or income 37 | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| VIP/0-3 years, maternal low education or income 37 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Healthy Steps/0-3 years38 -40 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Parenting Matters/2-5 years with parent discipline concern 41 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| PriCARE/2-6 years with behavior concerns42,43 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| DOCC/5-12 years with behavior concerns 44 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Primary Care Triple P/2-12 years with behavior concerns45 -48 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Minnesota Violence Prevention/7-15 years with behavior concerns 29 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Parent-child | Queensland Home Visits/0-4 months with 1 or more ACEs 26 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Well-Child Care Counseling, North Carolina, 0-6 months49,50 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Finger puppets/2-6 months51,52 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Baltimore Home Visits/0-18 months, maternal drug-abuse (ACE) 53 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Well-child care counseling, New York, 0-18 months54,55 | √ | |||||||||||||

| Caribbean Parenting/3-18 months 31 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Toddlers without Tears, 8-15 months 56 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Care for Development, 0-24 months 57 | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Building Blocks/0-3 years, maternal low education or income58 -60 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| VIP/0-3 years maternal low education or income35,58 -62 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Healthy Steps/0-3 years38 -40 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| SEEK/0-5 years screened for ACEs27,28 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Play Nicely, 1-5 years63 -65 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| PriCARE/2-6 years with behavior concerns42,43 | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Primary Care Triple P/2-12 years45 -48 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| DOCC/5-12 years with behavior concerns 44 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Minnesota Violence Prevention/7-15 years with behavior concerns 29 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: DOCC, Doctor Office Collaborative Care; PriCARE, Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement in Primary Care; SEEK, Safe Environment for Every Kid; THRIVE, Teaching Healthy Responsive parenting during Infancy to promote Vital growth and rEgulation; VIP, Videotape Interaction Project.

Figure 2.

Comparison of pediatric primary care parenting education interventions.

Interventions That Improved Child Physical Outcomes

Four out of 8 (50%) of the studies that measured any type of child physical health outcome demonstrated a statistically significant difference from the comparison group. One pilot study of THRIVE (Teaching Healthy Responsive parenting during Infancy to promote Vital growth and rEgulation) for general pediatric patients age 0 to 6 months found improvement in infant conditional weight gain. 25 This study used co-located psychology fellows to discuss responsive parenting at well-child care, including eating and sleep routines, and was compared to a control group that focused on mental health. Two interventions for children with ACEs reduced child injuries and assaults. One was a nurse home visiting program for infants which offered connection to community resources, parenting education, and social support. 26 The other was the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) intervention for age 0 to 5 years and trained pediatricians to offer information and community resources related to depression, substance abuse, partner violence, and stress, in addition to making a social worker available.27,28 The Minnesota Violence Prevention program reduced fight-related injuries. 29 This program was for children age 7 to 15 years with behavioral health symptoms, and provided information about child development, positive parenting, discipline and decision-making using a parenting manual, videotapes, and weekly phone coaching over 6 weeks.

Interventions That Improved Child Developmental Outcomes

Four out of the 9 (44%) interventions that measured child developmental outcomes demonstrated improvements. The Video-taped Interaction Project (VIP) utilized a co-located developmental specialist who met with families individually and reinforced positive interactions, in addition to sharing written information, books, and toys.33 -36 A Caribbean Parenting Intervention utilized community health workers and nurses to discuss waiting room videos and message cards about topics that included showing love, comforting, talking, praising, bath time, reading, and playing. 31 Both interventions improved cognitive development. VIP also improved expressive language, as did a program based upon Touchpoints that utilized parent coaches, handouts, videos, and follow-up home or telephone visits. 30 A fourth intervention improved social-emotional development compared to the group who declined the intervention. 32 This intervention by a pediatric psychologist was done at clinic or home-based visits and included parenting topics (such as discipline, sleep, feeding, and toileting), as well as information about developmental goals, play therapy, parent-child interaction therapy, and community resources.

Interventions That Improved Child Behavioral Outcomes

Eleven out of the 13 (84%) interventions that measured child behavior improved outcomes. Eight improved outcomes more than the comparison, including the Minnesota Violence Prevention program 29 and VIP. 37 The majority targeted children ages 2 years or older with parental concerns about child behavior.

A self-directed intervention enhanced imitation and play for toddlers from low-income and/or low education families through monthly newsletters, learning materials, and developmental questionnaires. 37 All of the other interventions that were superior to the comparison condition utilized support staff other than the pediatrician. The Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement in Primary Care (PriCARE) program utilized co-located mental health professionals to run weekly positive parenting groups over 6 weeks.42,43 Primary Care Triple P (Positive Parenting Program) utilized nurses to run four 2-h group sessions, in addition to weekly telephone calls, tip sheets and videos related to child development, behaviors, and positive parenting.45 -48 In Healthy Steps, a developmental specialist provided guidance on child development, parent support, and community resources through parent groups, home visits, and phone follow-up.38,39 In the Doctor Office Collaborative Care (DOCC) program, social workers met with individuals or groups over 6 months and provided information about managing stress, promoting positive behavior, anger control, and social skills. 44 Parenting Matters utilized phone coaching by clinical psychology students weekly over 6 weeks and provided information about child development, behaviors, positive parenting and discipline. 41

Interventions That Improved Parent-Child and/or Parent Mental Health Outcomes

Eighteen out of 20 (90%) interventions that measured parent-child outcomes improved outcomes. Seventeen improved outcomes more than the comparison group, including Queensland Home Visits, 26 SEEK,27,28 Caribbean Parenting, 31 Minnesota Violence Prevention, 29 Building Blocks,58 -60 VIP,35,58 -62 PriCARE,42,43 DOCC, 44 Primary Care Triple P,45 -47 and Healthy Steps. 40 In addition, 4 interventions improved outcomes through counseling by pediatricians. The Care for Development Intervention trained pediatricians in use of a standardized interview at acute visits and teaching parent strategies for listening, observing, praising, playing, and making homemade toys. 57 Play Nicely trained pediatricians to talk with parents about plans for discipline after they viewed a related video.63 -65 A third intervention focused on having pediatricians provide educational pamphlets, books, and videos at well-child care.54,55 Another well-child care intervention focused on normal development and responsiveness to infant social behaviors.49,50

Three additional interventions relied on support staff. Both the Baltimore Home Visits program which utilized nurse home visitors 53 and the Toddlers without Tears program that utilized facilitated parenting groups 56 improved emotional responsiveness and reduced harsh parenting. Also, a low-intensity intervention that had clinic staff provide finger puppets and a list of suggested activities at the 2-month well-child visit demonstrated increased cognitive stimulation, as well as reduced parental depression.51,52

Ten of the 13 (77%) interventions that also measured parent mental health outcomes demonstrated reductions in parent stress, depression, anxiety, and/or smoking.26,29,30,40,43,44,46,51,58,60

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to identify pediatric primary care interventions that focused on improving relational health and thereby might reduce the negative consequences of ACEs. Our results demonstrate that a range of low to high intensity interventions can improve relational health, such as decreased corporal punishment and psychological aggression, as well as increased maternal-child attachment, stimulating interactions, and sensitivity. Lower intensity interventions improved relational health simply through distribution of written materials, 37 toys that encouraged interactive play,51,52 or enhanced pediatrician counseling about parent-child interactions.49,50,57,63 -65 Higher intensity interventions involved pediatricians through screening and/or team meetings, as well as collaboration with nurse home visitors, social workers, or parent coaches.36-29,44,53 The 3 studies that demonstrated improved relational health in pediatric patients with known ACEs were high intensity in both pediatrician involvement and use of additional professionals.26,27,53 However, the majority of interventions that measured parent mental health demonstrated improvements, which suggests the potential for pediatric parenting interventions to reduce child exposure to ACEs and have clinical merit beyond the direct impact on the child.29,30,40,43,44,47,52,58

Child behaviors were also improved by a range of low to high intensity interventions. For example, 3 interventions were not superior to the comparison because child behaviors were improved by the low intensity comparison, specifically handouts only, 80 books only, 83 and phone coaching as opposed to in person coaching. 81 In addition, Building Blocks demonstrated enhanced child play and parent-child interactions, while lowering maternal depression, based only upon distribution of newsletters and learning materials. 37 Thus, pediatric practices that have limited resources to add support staff should keep in mind that sharing written information with families about positive parenting and play can be impactful.

By contrast, improving child development and reducing injuries required multicomponent interventions including support from additional professionals, such as developmental specialists, psychologists, social workers, parent coaches, and community health workers. In addition, all of the interventions that reduced child injuries26,27,29 and half of the interventions that improved child development30,32 also focused on connecting families to community resources, including information about parent mental health.

Positive parenting focuses on influencing child behavior through praise for positive behaviors and discipline strategies for negative behaviors. By contrast, responsive parenting focuses on building relationships between parents and children by listening to children, playing with them, and helping them to understand and manage their emotions. Of the interventions that improved child behavior and development, all included information about positive parenting strategies. Less than half of the interventions included responsive parenting content, and only 3 interventions included information specific to developing emotion regulation. Children affected by ACEs have been exposed to or are living with caregivers who have challenges with emotion regulation and stress management. Therefore, research is warranted to evaluate whether parenting education that incorporates information about responsive parenting is particularly helpful to reducing the negative consequences of ACEs.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, our conclusions may overestimate the efficacy of interventions due to publication bias. We tried to address this by reaching out to authors and making sure that our results included both significant and non-significant findings. Second, our review treated all of the interventions as having equal validity although some have been evaluated more extensively, particularly Healthy Steps and VIP. Most studies also only examined short-term impact, although Healthy Steps and VIP are exceptions. Furthermore, a variety of other pediatric interventions may impact child or parent-child outcomes but were not included in this review because they do not focus on education about parent-child relationships. For example, Reach Out and Read does not focus on education about parent-child relationships so was not included in this review, but does focus on child development with studies demonstrating positive impacts on language development and parent-child interactions. 84 The results of this review should be considered in the context of the broader literature on pediatric interventions.

Our results demonstrate a lack of parenting interventions to date that measured child physical health outcomes or biomarkers. More studies are needed that specifically evaluate the impact of pediatric primary care parenting interventions for children with ACEs, and more studies are needed on samples of school-age and adolescent patients.

In conclusion, this review provides a summary of pediatric primary care parenting intervention components and content which can be used by pediatricians to guide their selection of strategies to improve relational health and related outcomes. Our results highlight the potential for feasible, low-intensity interventions to improve relational health and child behaviors. Given that ACEs increase the risk for mental, physical, and developmental health issues across the lifespan, policies that support parents and access to parenting interventions are warranted, as is research funding to expand knowledge about how to foster healthier, more resilient communities.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501319241306302 for Parenting Education to Improve Relational Health Through Pediatric Primary Care: A Scoping Review by Ariane Marie-Mitchell, Cindy Delgado and Rachel Gilgoff in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Acknowledgments

We thank the librarians at the Loma Linda University Dell Webb Library for their technical support. We also thank Sarah Rock and the Community Translational Research Institute for administrative assistance with the ACEs Aware Grant.

Appendix.

Pediatric Primary Care Parenting Interventions (Alphabetical by Name of Intervention).

| Target | Name of intervention | Clinical intervention | Research | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-abusing pregnant women and their newborns followed into pediatric practice | Baltimore Home Visits 53 | People: Nurse home visitors who met weekly with pediatrician and psychologist Materials: handouts on child development Delivery: 2 home visits before birth and biweekly from birth to 18 months Information: Healthy parent-child interaction, child development, and community resources. Based upon The Carolina Preschool Curriculum and Hawaii Early Learning Program Follow-up: home visits until 18 months |

Design: RCT Sample: 60 pregnant women with histories of substance abuse and offspring followed until 18 months Comparison: usual primary care |

Physical: no difference in birth weight Behavioral: n/a Development: no difference in cognitive and motor development Parent-Child: more emotionally response based upon HOME scale Parent: no difference in parenting stress |

| Newborns at risk of developmental delay based upon low maternal education and/or low income | Building Blocks (BB)37,58

-60

*abbreviated list focusing on studies in the United States |

People: Pediatrician provided usual well-child care and materials Materials: monthly newsletters, learning materials (toy or book), developmental questionnaires Delivery: self-directed Information: Reinforce positive and supportive interactions Follow-up: none |

Design: RCTs Samples: (multiple studies of infants 0-36 months) Comparison: usual well-child care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: enhanced imitation/play Development: no difference Parent-Child: improved stimulating interactions Parent: lower maternal depression |

| General pediatric population age <24 months receiving acute care | Care for Development Intervention 57 | People: 2 pediatricians who received training in the care for Development Intervention Materials: none Delivery: individual Information: standardized interview and strategies for listening, observing, praising, playing, and making homemade toys Follow-up: clinic visit 1 week later |

Design: Quasi-experimental pre-post study Sample: 233 infants less than 24 months Comparison: usual primary care prior to training |

Physical: no difference in medical compliance or illness outcomes Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: improved environment on the HOME scale Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 3-18 months living in the Caribbean | Caribbean Parenting Intervention 31 | People: Pediatrician provided usual well-child care with Community health workers who discussed videos with families and Nurses who provided reinforcing message cards Materials: Waiting room videos, Message cards Delivery: individual Information: Topics included love, comforting, talking, praising, using bath time, looking at books, simple toys to make, drawing, games, and puzzles Follow-up: at well-child visits over 18 months |

Design: Cluster RCT Sample: 501 mother-child dyads from 29 health care centers; 262 children were reassessed at age 6 years Comparison: usual primary care |

Physical: no difference in growth Behavioral: n/a Development: improved cognitive development at 18 months only Parent-Child: improved parenting knowledge scores at 18 months only Parent: no difference in maternal depression |

| General pediatric patients age 8-13 years with a primary diagnosis of anxiety who were referred by primary care physician or self-referred | Cool Kids 81 | People: Child anxiety specialist in pediatric primary care or Therapist by phone Materials: parent and child workbook with exercises Delivery: individual sessions in primary care or telephone Information: psychoeducation, changing unhelpful thoughts, exposures, problem solving exercises, parent management exercises, and assertiveness skills Follow-up: weekly over 10 weeks |

Design: randomized comparison Sample: 48 8-13 year olds with anxiety seen by a pediatrician Comparison: face-to-face sessions in primary care compared to phone visits with therapist |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: no difference (reduced parent and child report of anxiety in both groups) Development: n/a Parent-Child: n/a Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 0-6 months | Developmental Stages and Guidance 82 | People: 2 Pediatricians and a Nurse Practitioner Materials: none Delivery: individual Information: Use of age specific discussions of affective, cognitive, and physical development Follow-up: well-child visits to 6 months |

Design: RCT Sample: 83 inner city mothers and their healthy first-born infants followed to 6 months Comparison: usual well-child care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: no significant differences Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 5-12 years old referred by pediatrician for behavior concerns | Doctor Office Collaborative Care (DOCC) 44 | People: 4 social workers with pediatrician involvement Materials: psychoeducational materials Delivery: 6-12 individual or group sessions Information: managing stress, promoting positive behavior, anger control, social skills Follow-up: over 6 months |

Design: cluster RCT Sample: 321 5-12 year olds from general pediatric practice with ADHD, disruptive behavior or anxiety Comparison: usual care |

Physical: no change physical quality life Behavioral: reduced behavior problems, hyperactivity, and internalizing problems Development: n/a Parent-Child: improved parent-child interaction Parent: decreased parenting stress |

| Low risk pediatric population age 2 months old (born full-term, >2500 g, without chronic conditions, or neurodevelopmental exposures to mothers age 18 years or older who spoke English or Spanish and did not expect to move during study period) | Finger Puppets51,52 | People: Research assistant gave finger puppet to mothers in pediatric waiting room at infant well-child check Resources: finger puppet, list of 10 suggested activities to do Delivery: individual 1-min interaction Information: important to talk with infants so can learn to talk and be ready for school Follow-up: well-child care until a. 4 months or b. 6 months |

Design: cohort study over 2-4 months Sample: 116 to 127 mothers of infants presenting for well-child at age 2 months old Comparison: usual well-child care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: increased parental involvement and cognitive stimulation Parent: reduced maternal postpartum depression reported at 4 month well-child visit |

| General pediatric population age 0-3 years | Healthy Steps for Young Children38

-40

*abbreviated reference list |

People: Pediatrician provided usual well-child care with developmental specialist Materials: written handouts Delivery: individual and group Information: child development, parent support & community resources Follow-up: phone support plus up to 7 home visits after well-child visit |

Design: RCTs and quasi-experimental Sample: (multiple studies of age 0-3 year olds; see Piotrowski et al 40 for summary) Comparison: usual primary care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: less likely to report child behavior problems Development: no difference in vocabularies Parent-Child: more securely attached, established routines, reading, playing; less harsh discipline, Parent: more likely to discuss depressive concerns but symptoms less likely to be above cutoff |

| General pediatric patients age 3-6 years screened using the Child Behavior Checklist for Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) | Incredible Years in Primary Care 83 | People: Therapist-led or Nurse-led groups in pediatric primary care Materials: Incredible Years book Delivery: group Information: appropriate play, use of parental attention, praise, consequences, discipline techniques including time out Follow-up: over 6-12 sessions |

Design: RCT Sample: 24 practices randomized to 1 of 2 conditions for 117 3-6 year olds with ODD seen in primary care Comparison: Incredible Years book only |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: no difference (decreased behavior problems in all groups) Development: n/a Parent-Child: no difference in parenting knowledge Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 7-15 years screened using the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 | Minnesota Violence Prevention 29 | People: Pediatrician responded to positive screen and when appropriate made a referral to a telephone-based program (Positive Parenting parent educator), mental health, or other resources Materials: Positive Parenting manual and 2 videotapes Delivery: individual coaching by phone weekly over an average of 6 weeks (range 1-15) Information: child development, positive parenting, discipline, decision-making & peers Follow-up: by phone over 6 weeks (range 1-15) |

Design: RCT Sample: 224 children age 7-15 years old with a positive screen for internalizing, externalizing, or inattentive symptoms Comparison: usual primary care (did not see screening results) |

Physical: decreased fight-related injuries Behavioral: decreased aggressive, delinquent behavior & inattention Development: n/a Parent-Child: decreased use of corporal punishment Parent: decreased parental depression |

| General pediatric population age 2-5 years with parent concerns about child discipline | Parenting Matters 41 | People: Family medicine physician referred to telephone coach (graduate student in clinical psychology) Materials: written self-help booklet Delivery: individual by weekly phone calls for 6 weeks Information: child development, positive parenting, discipline, and decreasing negative behaviors Follow-up: coach by phone over 6 weeks |

Design: RCT Sample: 178 caregivers of children age 2-5 years old Comparison: usual primary care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: decreased behavior problems Development: n/a Parent-Child: n/a Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 1-5 year | Play Nicely63 -65 | People: pediatricians Materials: video Delivery: a/b: 5-10 min multimedia program about responding to child aggression viewed in waiting room; c. online website Information: do not allow child to be victim, do not allow aggression, decrease exposure to violence, show love, and consistency (also pediatricians may have discussed discipline) Follow-up: none |

Design: RCT Sample: a. 258 caregivers of children 6-24 months old 63 ; b. 258 caregivers of child age 1-5 years old presenting for well-child care 65 ; c. 52 caregivers of children age 1-5 years old 64 Comparison: a/b. routine primary care; c. child maltreatment website |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: parents were assisted in plans for discipline if discussion with pediatrician or viewed program; less likely to endorse physical punishment (not significant for sample c) Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 2-6 years old with parent concerns about child behavior | Child-Adult Relationship Enhancement in Primary Care (PriCARE)42,43 | People: 2 licensed mental health professionals co-located in urban pediatric practice Materials: home practice assignments Delivery: group Information: positive parenting to increase prosocial behaviors, effective commands to increase compliance Follow-up: weekly for 6 weeks |

Design: RCT Sample: a. 120 2-6 year olds from an urban pediatric clinic 42 ; b. 174 2-6 year olds from 1 of 4 urban pediatric clinics 43 Comparison: waitlist control |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: decreased behavior problems Development: n/a Parent-Child: improved parenting attitudes on AAPI-2 Parent: reduced parenting stress |

| General pediatric population age 3-6 years with parent concerns about child behavior and willingness to participate in parent program, included if screened positive on the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory | Primary Care Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PC-PCIT) 80 | People: Therapist-led groups in pediatric primary care Materials: handouts about managing difficult behaviors, parenting tip sheets Delivery: group Information: Enhanced parent-child attachment, positive parenting, child social skills, clear, and consistent rules Follow-up: over 4 weeks |

Design: RCT Sample: 30 3-6 year olds with subclinical behavior problems Comparison: handouts only |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: no difference (decreased behavior problems in both groups) Development: n/a Parent-Child: no difference (decreased dysfunctional discipline in both groups) Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population a,b: age 2-12 years living in Hong Kong (no psychiatric illnesses or domestic violence) but referred for child behavior, parenting, or psychosocial concern c. age 2-6 years living in Australia (no developmental delay or psychiatric problem, parents not in therapy, or relationship problems) but concern for child behavior; d. Age 9-11 years living in Netherlands with mild psychosocial concerns based upon the Strengths and Difficulties Questionniare |

Primary Care Triple P- Positive Parenting Program45 -48 | People: pediatric clinic staff and nurses Materials: tip sheets and videos Delivery: four 2-h group sessions led by nurses Information: common behavior problems and developmental issues, positive non-violent child management techniques Follow-up: weekly telephone calls |

Design: a,b,d: RCT; c. pre-post Sample: a. 93 parents of age 3-7 year olds receiving care from a Maternal and Child Health Center 45 ; b. 661 parents of age 2-12 year olds receiving care from a MCHC or Child Assessment Center 46 ; c. 30 families of age 2-6 years presenting to community health clinics 47 ; d. 81 families of age 9-11 years with mild psychosocial concerns 48 Comparison: a,b,c: wait-list control; d. Usual care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: decreased child disruptive behavior Development: n/a Parent-Child: decreased dysfunctional parenting Parent: decreased parenting stress, depression, and anxiety d. No statistically significant differences found |

| General postnatal pediatric population screened for family vulnerability including single parenting, mental health problems, substance use problems, domestic violence, and childhood abuse | Queensland, Australia Home Visits 26 | People: Nurse home visitors who met weekly with pediatrician and team social worker Materials: none Delivery: home visits weekly to 6 weeks, fortnightly to 3 months; also social work intervention for subset needing more support Information: enhance parenting self-esteem, provide guidance for normal child development, promote preventative child health care; facilitate access to appropriate community services Follow-up: home visits until 3 months |

Design: RCT Sample: 181 mothers of newborns followed until 4 months Comparison: usual care |

Physical: reduced parent-reported injuries and bruises Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: improved all subscales of HOME including maternal-infant attachment Parent: no change in postnatal depression or stress; decreased smoking |

| General pediatric population age 0-5 years screened for parental depression, substance abuse, intimate partner violence |

Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK)27,28 | People: Pediatricians screened and counseled, Social worker if needed Materials: written handouts Delivery: individual Information: parental depression, substance abuse, major stress, intimate partner violence and related community resources Follow-up: social worker by phone if needed after initial primary care visit |

Design: RCTs Sample: a. 729 caregivers of children age 0-5 year olds 27 ; b. 1119 caregivers of children age 0-5 year olds 28 Comparison: usual primary care |

Physical: fewer minor physical assaults Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: less psychological aggression, fewer CPS reports Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 6-36 months screened for developmental concerns | Social-emotional screening 32 | People: nursing staff distributed developmental screen and pediatric psychologist provided intervention or referrals in consultation with pediatrician Materials: none Delivery: office or home-based appointments as needed Information: discipline, sleep, feeding, toileting, developmental goals, play therapy, parent-child interaction therapy; community resources Follow-up: until 36 months; also telephone information line |

Design: cohort study Sample: 170 infants and toddlers with developmental concerns based upon screening Comparison: declined intervention |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: n/a Development: improvements on ASQ-SE scores Parent-Child: n/a Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 0-6 months | Teaching Healthy Responsive parenting during Infancy to promote Vital growth and Regulation (THRIVE) 25 | People: psychology fellows integrated in pediatric primary care Resources: handouts Delivery: 4 individual sessions in conjunction with well-child care Information: responsive parenting principles targeted to establish healthy eating, sleeping, and emotion regulation Follow-up: well-child care until 6 months |

Design: parallel RCT Sample: 65 mother-infant dyads Comparison: attention control focused on promoting mental health |

Physical: medium effect on conditional weight gain (CWG) Behavioral: n/a Development: n/a Parent-Child: n/a Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 8-15 months | Toddlers without Tears 56 | People: nurse and parenting facilitator in pediatric practice Materials: handouts on child development Delivery: three 2-h groups Information: unreasonable expectations, harsh parenting, and lack of nurturing parenting Follow-up: well-child care at 8, 12, and 15 months visits |

Design: cluster randomized trial Sample: 733 English speaking mothers of 6-8 month old children in Australia Comparison: usual well-child care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: no difference in child behaviors Development: n/a Parent-Child: reduced harsh parenting and unreasonable expectations at 24 months; reduce unreasonable expectations at 36 months Parent: no difference in parent mental health |

| General pediatric neonatal population | Touchpoints, parent coaching based upon 30 | People: Parent coaches at a pediatric practice with support from social work, nursing, education director & community advisory group Materials: handouts and videos about parent-child interactions Delivery: coach met at well-child care then followed up with home visits and phone calls Information: (1) strengthen parent–health provider relationship and communication; (2) educate about the importance of nonharsh parent–child interactions and age-appropriate child behaviors; and (3) increase family use of community resources Follow-up: until 18 months |

Design: quasi-experimental pre-post study Sample: 50 newborns from low-income Latino and African American families receiving well-baby care at an urban primary care health center Comparison: 30 matched newborns from community sample |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: n/a Development: improved communication Parent-Child: n/a Parent: improved adequacy of family needs & parental resilience |

| Newborns at risk of developmental delay based upon low maternal education and/or low income | Video-taped Interaction Project (VIP)33

-37,58

-62

*abbreviated list focusing on studies in the United States |

People: Pediatrician provided usual well-child care with developmental specialist providing VIP Materials: learning materials (toy or book), video of parent-child interaction, pamphlets Delivery: 12-15 individual sessions between birth and age 3 years at well-child care visits Information: Reinforce positive and supportive interactions Follow-up: by developmental specialist up to 36 months |

Design: RCTs Samples: (multiple studies of mother-infant dyads) Comparison: usual well-child care |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: enhanced imitation/play and attention, reduced externalizing problems Development: improved cognitive development and expressive language Parent-Child: improved stimulating interactions and reading, lower physical punishment, decreased perceived picky eating Parent: lower parenting stress, lower maternal depression |

| General pediatric population age 0-18 months (first born child, mothers English-speaking, and at least eighth grade educated) | Well-Child Care Counseling, New York54,55 | People: 35 pediatricians; if complex problems also social workers or psychologists Materials: educational pamphlets, books, and audio-visuals Delivery: well-child care Information: child development Follow-up: none |

Design: cohort study over 30 months Sample: 595 mother-infant dyads Comparison: low, medium, and high physician teaching input |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: not significant Development: not significant Parent-Child: more parent-reported positive contact Parent: n/a |

| General pediatric population age 0-6 months | Well-Child Care Counseling, North Carolina49,50 | People: one pediatrician Materials: none Delivery: well-child visit Information: normal development and responsiveness to infant social behaviors Follow-up: well-child visits until 6 months old |

Design: RCT Sample: 32 mother-infant dyads Comparison: accident prevention and nutrition |

Physical: n/a Behavioral: n/a Development: no significant differences on structured developmental ratings Parent-Child: increased sensitivity and appropriateness of mother-infant interactions Parent: n/a |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Ariane Marie-Mitchell conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data extraction, drafted, and revised the manuscript. Dr. Cindy Delgago extracted data from literature, edited and summarized references, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. Rachel Gilgoff conceptualized the study, extracted data from literature, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions and editing, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was initiated through a California ACEs Aware Grant, “Relational Health to Improve ACEs Care” funded from June 2020 to June 2021. The ACEs Aware Initiative had no role in the design and conduct of this literature review.

Ethical Considerations: Not applicable (literature review).

Consent to Participate: Not applicable (literature review).

Consent for Publication: Not applicable (literature review).

ORCID iD: Ariane Marie-Mitchell  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5868-9117

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5868-9117

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Moyer V, Butler M. Gaps in the evidence for well-child care: a challenge to our profession. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1511-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Felitti V, Anda R, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown D, Anda R, Tiemeier H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:389-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Danese A, Moffitt T, Harrington H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(12):1135-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dube S, Felitti V, Dong M, Giles W, Anda R. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):268-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anda R, Felitti V, Bremner J, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burke N, Hellman J, Scott B, Weems C, Carrion V. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:408-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flaherty E, Thompson R, Litrownik A, et al. Adverse childhood exposures and reported child health at age 12. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:150-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flaherty E, Thompson R, Dubowitz H, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and child health in early adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):622-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Macleod J, Hickman M, Bowen E, Alati R, Tilling K, Smith G. Parental drug use, early adversities, later childhood problems and children’s use of tobacco and alcohol at age10: birth cohort study. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1731-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marie-Mitchell A, O’Connor T. Adverse childhood experiences: translating knowledge about adverse childhood experiences into the identification of children at risk for poor outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 13(1):14-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oh D, Jerman P, Marques S, et al. Systematic review of pediatric health outcomes associated with childhood adversity. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu YR, Merritt DH. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression among Chinese children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;88:316-332. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masud H, Ahmad MS, Cho KW, Fakhr Z. Parenting styles and aggression among young adolescents: a systematic review of literature. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(6):1015-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis B, Baggett KM, Patterson AL, Feil EG, Landry SH, Leve C. Power and efficacy of maternal voice in neonatal intensive care units: implicit bias and family-centered care. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(4):905-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manczak EM, Levine CS, Ehrlich KB, Basu D, McAdams DP, Chen E. Associations between spontaneous parental perspective-taking and stimulated cytokine responses in children with asthma. Health Psychol. 2017;36(7):652-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Young M, Lord J, Patel N, Gruhn M, Jaser S. Good cop, bad cop: quality of parental involvement in type 1 diabetes management in youth. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(11):546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Psihogios A, Fellmeth H, Schwartz L, Barakat LP. Family functioning and medical adherence across children and adolescents with chronic health conditions: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019;44(1):84-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Purewal Boparai S, Au V, Koita K, et al. Ameliorating the biological impacts of childhood adversity: a review of intervention programs. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;81:82-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garner A, Yogman M. Preventing childhood toxic stress: partnering with families and communities to promote relational health. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2021052582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Myers K, Vander Stoep A, Zhou C, McCarty C, Katon W. Effectiveness of a telehealth service delivery model for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a community-based randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54(4):263-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zachry A, Jones T, Flick J, Richey P. The early STEPS pilot study: the impact of a brief consultation session on self-reported parenting satisfaction. Matern Child Health J. 2021;25(12):1923-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zuckerman B, Edson K, Mesite L, Hatcher C, Rowe M. Small moments, big impact: pilot trial of a relational health app for primary care. Acad Pediatric. 2022;22(8):1437-1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rybak T, Modi A, Mara C, et al. A pilot randomized trial of an obesity prevention program for high-risk infants in primary care. J Pediatr Psychol. 2023;48(2):123-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Armstrong KL, Fraser JA, Dadds MR, Morris J. Promoting secure attachment, maternal mood and child health in a vulnerable population: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Child Health. 2000;36(6):555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Kim J. Pediatric primary care to help prevent child maltreatment: the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):858-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dubowitz H, Lane WG, Semiatin JN, Magder LS. The SEEK model of pediatric primary care: can child maltreatment be prevented in a low-risk population? Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(4):259-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borowsky IW. Effects of a primary care-based intervention on violent behavior and injury in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e392-e399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farber LZM. Parent mentoring and child anticipatory guidance with Latino and African American families. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(3):179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang SM, Grantham-Mcgregor SM, Powell CA, et al. Integrating a parenting intervention with routine primary health care: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136:272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Briggs R, Stettler E, Silver E, et al. Social-emotional screening for infants and toddlers in primary care. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e377-e384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mendelsohn AL, Cates CB, Weisleder A, et al. Reading aloud, play, and social-emotional development. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mendelsohn AL, Dreyer BP, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care to promote child development: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(1):34-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mendelsohn A, Valdez P, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care: impact at 33 months on parenting and on child development. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):206-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cates C, Weisleder A, Johnson S, et al. Enhancing parent talk, reading, and play in primary care: sustained impacts of the video interaction project. Pediatrics. 2018;199:49-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weisleder A, Brockmeyer C, Dreyer PB, et al. Promotion of positive parenting and prevention of socioemotional disparities. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20153239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Minkovitz C, Hughart N, Strobino D, et al. A practice-based intervention to enhance quality of care in the first 3 years of life. JAMA. 2003;290(23):3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Caughy MOH, Huang KY, Miller T, Genevro JL. The effects of the Healthy Steps for Young Children Program: results from observations of parenting and child development. Early Child Res Q. 2004;19:611-630. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piotrowski C, Talavera G, Mayer J. Healthy steps: a systematic review of a preventive practice-based model of pediatric care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(1):91-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reid G, Stewart M, Vingilis E, et al. Randomized trial of distance-based treatment for young children with discipline problems seen in primary health care. Fam Pract. 2013;30(1):14-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schilling S, French B, Berkowitz JS, Dougherty LS, Scribano VP, Wood NJ. Child-adult relationship enhancement in primary care (PriCARE): a randomized trial of a parent training for child behavior problems. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(1):53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wood J, Kratchman D, Scribano P, Berkowitz S, Schilling S. Improving child behaviors and parental stress: a randomized trial of child adult relationship enhancement in primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(4):629-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kolko DJ, Campo J, Kilbourne AM, Hart J, Sakolsky D, Wisniewski S. Collaborative care outcomes for pediatric behavioral health problems: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e981-e992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leung C, Sanders MR, Leung S, Mak R, Lau J. An outcome evaluation of the implementation of the triple P-positive parenting program in Hong Kong. Fam Process. 2003;42(4):531-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leung C, Sanders R, Francis I, Lau J. Implementation of triple P-positive parenting program in Hong Kong: predictors of programme completion and clinical outcomes. J Child Serv. 2006;1(2):4-17. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Turner KMT, Sanders MR. Help when it’s needed first: a controlled evaluation of brief, preventive behavioral family intervention in a primary care setting. Behav Ther. 2006;37(2):131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spijkers W, Jansen D, Reijneveld S. Effectiveness of primary care triple P on child psychosocial problems in preventive child healthcare: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Casey P, Whitt J. Effect of the pediatrician on the mother-infant relationship. Pediatrics. 1980;65(4):815-820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whitt JK, Casey PH. The mother-infant relationship and infant development: the effect of pediatric intervention. Child Dev. 1982;53(4):948-956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Domek G, Szafran L, Allison M, et al. Finger puppets to support early language development: effects of a primary care-based intervention in infancy. Clin Pediatr. 2023;62(12):1497-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Domek G, Heller Szafran L, Jimenez-Zambrano A, Silveira L. Impact on maternal postpartum depressive symptoms of a primary care intervention promoting early language: a pilot study. Matern Child Health J. 2023;27(2):346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Black MM, Nair P, Kight C, Wachtel R, Roby P, Schuler M. Parenting and early development among children of drug-abusing women: effects of home intervention. Pediatrics. 1994;94(4 Pt 1):440-448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chamberlin RW, Szumowski EK. A follow-up study of parent education in pediatric office practices: impact at age two and a half. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(11):1180-1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chamberlin RW, Szumowski EK, Zastowny TR. An evaluation of efforts to educate mothers about child development in pediatric office practices. Am J Public Health. 1979;69(9):875-886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hiscock H, Bayer J, Price A, Ukoumunne O, Rogers S, Wake M. Universal parenting programme to prevent early childhood behavioural problems: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):318-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ertem O, Atay G, Bingoler B, Dogan D, Bayhan A, Sarica D. Promoting child development at sick-child visits: a controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e124-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Berkule S, Cates C, Dreyer B, et al. Reducing maternal depressive symptoms through promotion of parenting in pediatric primary care. Clin Pediatr. 2014;53(5):460-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Canfield FC, Wiesleder A, Cates BC, et al. Primary care parenting intervention effects on use of physical punishment among low-income parents of toddlers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(8):586-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mendelsohn A, Huberman H, Berkule SB, Brockmeyer C, Morrow L, Dreyer B. Primary care strategies for promoting parent-child interactions and school readiness in at-risk families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(1):33-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cates C, Weisleder A, Dreyer B, et al. Leveraging healthcare to promote responsive parenting: impacts of the video interaction project on parenting stress. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(3):827-835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Katzow M, Canfield CF, Gross S, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and perceived picky eating in a low-income, primarily Hispanic sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(9):706-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chavis A, Hudnut-Beumler J, Webb MW, et al. A brief intervention affects parents’ attitudes toward using less physical punishment. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(12):1192-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Richardson H, Damashek A. Examining the use of a brief online intervention in primary care for changing low-income caregivers’ attitudes toward spanking. J Iinterpers Violence. 2022;37(21-22):Np20409-np20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Scholer SJ, Hudnut-Beumler J, Dietrich M. The effect of physician: parent discussions and a brief intervention on caregivers’ plan to discipline: is it time for a new approach? Clin Pediatr. 2011;50(8):712-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Breitenstein S, Gross D, Christophersen R. Digital delivery methods of parenting training interventions: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(3):168-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Brown C, Raglin Bignall W, Ammerman R. Preventive behavioral health programs in primary care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20180611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cluxton-Keller F, Riley AW, Noazin S, Umoren MV. Clinical effectiveness of family therapeutic interventions embedded in general pediatric primary care settings for parental mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(4):395-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Coker TR, Windon A, Moreno C, Schuster MA, Chung PJ. Well-child care clinical practice redesign for young children: a systematic review of strategies and tools. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):S5-S25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. De Cesaro B, Gurgel L, Nunes G, Reppold C. Child language interventions in public health: a systematic literature review. Codas. 2013;25(6):588-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kendrick D, Barlow J, Hampshire A, Stewart-Brown S, Polnay L. Parenting interventions and the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood: systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(5):682-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Marie-Mitchell A, Kostolansky R. A systematic review of trials to improve child outcomes associated with adverse childhood experiences. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):756-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. McCalman J, Heyeres M, Campbell S, et al. Family-centred interventions by primary healthcare services for Indigenous early childhood wellbeing in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States: a systematic scoping review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Moon DJ, Damman J, Romero A. The effects of primary care-based parenting interventions on parenting and child behavioral outcomes: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020;21(4):706-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Peacock-Chambers E, Ivy K, Bair-Merritt M. Primary care interventions for early childhood development: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Shah R, Kennedy S, Clark M, Bauer S, Schwartz A. Primary care–based interventions to promote positive parenting behaviors: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Smith JD, Cruden G, Rojas L, et al. Parenting interventions in pediatric primary care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20193548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tully L, Hunt C. Brief parenting interventions for children at risk of externalizing behavior problems: a systematic review. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(3):705-719. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Van Aar J, Leijten P, Orobio De Castro B, Overbeek G. Sustained, fade-out or sleeper effects? A systematic review and meta-analysis of parenting interventions for disruptive child behavior. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:153-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Berkovits DM, O’Brien AK, CG C., Eyberg MS. Early identification and intervention for behavior problems in primary care: a comparison of two abbreviated versions of parent-child interaction therapy. Behav Ther. 2010;41(3):375-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chavira D, Drahota A, Garland A, Roesch S, Garcia M, Stein M. Feasibility of two modes of treatment delivery for child anxiety in primary care. Behav Res Ther. 2014;60:60-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dworkin P, Allen D, Geertsma M, Solkoske L, Cullina J. Does developmental content influence the effectiveness of anticipatory guidance? Pediatrics. 1987;80(2):196-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lavigne JV, Lebailly SA, Gouze KR, et al. Treating oppositional defiant disorder in primary care: a comparison of three models. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;33(5):449-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Garbe M, Bond S, Boulware C, et al. The effect of exposure to reach out and read on shared reading behaviors. Acad Pediatr. 2023;23(8):1598-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501319241306302 for Parenting Education to Improve Relational Health Through Pediatric Primary Care: A Scoping Review by Ariane Marie-Mitchell, Cindy Delgado and Rachel Gilgoff in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health