ABSTRACT

The dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, which almost exclusively resides within host phagocytic cells during infection, must meet its nutritional needs by scavenging molecules from the phagosome environment. The requirement for gluconeogenesis, but not fatty acid catabolism, for intracellular growth, implicates amino acids as a likely intracellular nutrient source. Consequently, we investigated Histoplasma growth on amino acids. Growth assays demonstrated that Histoplasma yeasts readily utilize most amino acids as nitrogen sources but only efficiently catabolize glutamine, glutamate, aspartate, proline, isoleucine, and alanine as carbon sources. An amino acid permease-based conserved domain search identified 28 putative amino acid transporters within the Histoplasma genome. We characterized the substrate specificities of the major Histoplasma amino acid transporters using a Saccharomyces cerevisiae heterologous expression system and found that H. capsulatum Dip5, Gap3, and a newly described permease, Gai1, comprise most of Histoplasma’s amino acid import capacity. Histoplasma yeasts deficient in these three transporters are impaired for growth on free amino acids but proliferate within macrophages and remain fully virulent during infection of mice, indicating that free amino acids are not the principal nutrient source within the phagosome to support Histoplasma proliferation during infection.

KEYWORDS: Histoplasma, pathogenesis, phagosome, amino acid transporter, macrophage

Introduction

Histoplasma capsulatum is a thermally dimorphic fungal pathogen and the causative agent of histoplasmosis, which ranges in clinical presentation from a flulike respiratory illness to widespread disseminated disease [1–3]. As a primary pathogen, Histoplasma causes disease in both immunocompromised and in healthy individuals due to a robust virulence program triggered by mammalian body temperature-induced transition to the yeast phase [4]. After inhalation of Histoplasma, lung-resident macrophages take up the fungal cells, which grow and replicate within the macrophage phagosome, an environment typically restrictive to microbes. How Histoplasma acquires nutrients within this restrictive compartment is poorly understood, with most of the current knowledge pertaining to acquisition of specific micronutrients. Trace metals, such as copper, zinc, and iron, are scavenged by Histoplasma using high affinity transporters for copper and zinc and secreted siderophores for iron [5–9]. On the other hand, uracil, tryptophan, and vitamins such as pantothenate and riboflavin are not available within the phagosome, necessitating de novo biosynthesis of these compounds by Histoplasma yeasts [10–12]. The broader metabolite profile of the macrophage phagosome, especially for fungal pathogens, is generally inferred from transcriptional and genetic studies. For example, phagosomes containing Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans generally lack sugars, forcing internalized fungi to rely on gluconeogenic carbon sources such as fatty acids and amino acids [13,14]. Gluconeogenesis is also required for Histoplasma’s intracellular growth [15]. However, unlike C. albicans, which requires the glyoxylate cycle for its virulence [16], fatty acid catabolism is dispensable for H. capsulatum during infection, as Histoplasma mutants deficient in beta oxidation and the glyoxylate cycle are fully virulent in cultured macrophages and in mice [15]. Since amino acids are additional candidate gluconeogenic substrates inside host cells, we investigated amino acids as potential nitrogen and carbon sources available in the phagosome for intracellular Histoplasma yeast.

Amino acid uptake in fungi is carried out by transporters belonging to the well-conserved amino acid-polyamine-organocation (APC) superfamily. In A. fumigatus, 13 amino acid transporters were upregulated within 12 hours after mouse lung infection [17]. The genomes of C. neoformans and C. albicans encode at least 9 and 28 amino acid permeases, respectively, and these have been largely characterized based on their homology to the amino acid permeases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae [18,19]. Two C. neoformans transporters, Aap4 and Aap5, have broad amino acid substrate specificity, and loss of both transporters results in inability to import amino acids at 37°C and attenuated virulence in mice [18]. The amino acid transporters of C. albicans, particularly the six general amino acid permease (Gap) homologs, have varying substrate specificities [19–21], and C. albicans Gap4 is required for filamentation in response to S-adenosylmethionine [19]. Additionally, in C. albicans both Stp2 (an amino acid-responsive transcription factor) and Csh3 (an ER chaperone required for proper folding and trafficking of amino acid transporters) are required for alkalinization of media during growth on amino acids [22,23]. A C. albicans stp2 mutant was further found to be less virulent in a mouse model of candidemia [23]. More recently, the GNP family of amino acid transporters in Candida were characterized using toxic amino acid analogs and the transporters shown to be important for fungal survival within and damage to host macrophages, though only minor virulence defects were observed in mice [21]. Undoubtedly, much remains to be understood about the role of host-derived amino acids during fungal infections and which specific amino acids may be available as nutritional sources.

However, most fungal pathogens are largely extracellular during infection. A. fumigatus grows as extracellular filaments, and C. neoformans and C. albicans are only transiently intracellular, having evolved mechanisms for avoiding phagocytosis and inducing their own escape from host macrophages [23–25]. H. capsulatum, on the other hand, is almost exclusively intracellular during acute infection, making it a unique model for probing the macrophage phagosomal environment. Here, we examine the adaptation of Histoplasma for growth on amino acids by functionally characterizing Histoplasma’s ability to import and grow on free amino acids as its carbon or nitrogen source and determine the importance of amino acid import for Histoplasma intracellular proliferation and virulence.

Materials and methods

Histoplasma capsulatum strains and cultivation

The H. capsulatum strains used in this study are listed in Table S1A and were derived from the G217B clinical isolate (NAm2 clade, ATCC# 26032). Strains were cultivated as yeasts at 37°C using Histoplasma-Macrophage Medium (HMM) or using a defined minimal 3 M-based medium [26] supplemented with carbon and nitrogen sources as described. For general maintenance, strains were plated on HMM media solidified with 0.6% agarose and supplemented with 25 µM FeSO4. For growth of uracil auxotrophs, media was supplemented with 100 µg/mL uracil. Yeast liquid cultures were grown at 37°C with continuous shaking (200 rpm). For growth experiments and infections, Histoplasma yeast cultures were grown to late exponential growth phase in liquid HMM media prior to use in experiments. Growth was quantified either by measuring culture turbidity via optical density at 595 nm or by enumeration of CFU via plating of serial dilutions on solid HMM media.

Identification and phylogeny of Histoplasma amino acid transporters

Putative Histoplasma amino acid transporters were identified by searching the H. capsulatum G217B genome for proteins containing the Pfam domains PF00209 (SNF), PF00324 (AA_permease), PF01490 (Aa_trans), PF03222 (Trp_Tyr_perm), PF05525 (Branch_AA_trans), PF13520 (AA_permease_2), or PF13906 (AA_permease_C) using the HMMsearch software (HMMER version 3.3). Proteins matching PF00324, PF01490, and PF13520 were identified, and homologous fungal proteins in other fungi were extracted from the SwissProt protein database for: Aspergillus fumigatus Af293 (taxid: 330879), Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 (taxid: 227321), Blastomyces dermatitidis ER-3 (taxid: 559297), Candida albicans SC5314 (taxid: 237561), Coccidioides immitis RS (taxid: 246410), Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii H99 (taxid: 235443), Fusarium verticillioides 7600 (taxid: 334819), Malassezia globosa CBS 7966 (taxid: 425265), Neurospora crassa OR74A (taxid: 367110), Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C (taxid: 559292), Schizosaccharomyces pombe 972 h- (taxid: 284812), Trichophyton rubrum CBS 118,892 (taxid: 559305), Ustilago maydis (taxid: 5270). Protein sequences were trimmed to contain only the Pfam transporter domain and domain sequences aligned using Clustal (MEGA; version 10.2.4) [27]. Aligned proteins were used to construct a phylogenetic tree to infer orthology using the neighbour-joining method.

Heterologous expression of Histoplasma transporters in S. cerevisiae

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain 22Δ10α, which lacks 10 amino acid transporters, was used for heterologous expression studies [28]. S. cerevisiae strain 23344c, which retains all amino acid transporters but is otherwise isogenic with 22Δ10α, was used as the wild-type control (both S. cerevisiae strains provided by Guillaume Pilot, Virginia Tech). S. cerevisiae strains were maintained at 30°C on minimal media containing 2% glucose, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base (YNB) lacking amino acids and ammonium sulfate, 5 g/L ammonium sulfate, and supplemented with 200 mg/L uracil for ura3 mutant strains. For solid media, 8 g/L agar was included. S. cerevisiae strain 22Δ10α was transformed with URA3-based Histoplasma transporter expression plasmids (listed in Table S1B) using lithium acetate-mediated transformation [29]. Histoplasma transporter-encoding genes were amplified by PCR from H. capsulatum cDNA and cloned into the pDR196 S. cerevisiae constitutive expression vector [30]. Transformants were tested for amino acid import by culture in YNB-glucose medium without amino acids or ammonium sulfate, supplemented with individual amino acids as the nitrogen source in a 96-well microtiter plate. Each amino acid was tested across a range of concentrations up to 4 mM. Wells containing YNB-glucose medium with 4 mM ammonium sulfate were included as positive growth controls. Plates were incubated at 30°C with twice daily agitation at 1000 rpm. Growth was measured daily by culture turbidity via optical density at 595 nm using a BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader until early stationary phase was reached in wells containing wild-type S. cerevisiae 23344c at the 4 mM amino acid concentration (approx. 48-72 h, depending on the substrate used). Endpoint growth for each amino acid concentration was determined as the area under the curve across amino acid concentrations (GraphPad Prism software (v9.5.0)) normalized to that of wild-type S. cerevisiae 23344c and S. cerevisiae 22Δ10α transformed with the empty vector pDR196 (representing 100% and 0% growth, respectively).

Transcriptional profiling

RNA for reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis was isolated from log phase wild-type H. capsulatum yeasts grown for 24 hours in 3 M media containing 1.5% glucose or 1.5% casamino acids as the carbon source, or from yeasts collected from a 24-hour infection of P388D1 macrophages (MOI 1:1). RNA was released from yeasts via mechanical disruption of yeasts with 0.5 mm-diameter glass beads in TRIzol (Invitrogen) and purified using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research). For RT-qPCR, cDNA was generated from total RNA using Maxima reverse transcriptase (Thermo Scientific) primed with random pentadecamers. Quantitative PCR was performed using gene-specific primer pairs (Table S2), and products were quantified via SYBR green fluorescence detection (SensiMix SYBR No-ROX Kit, Bioline). Changes in gene expression were quantified relative to the average expression of the constitutive Histoplasma ACT1, RPS15, and TEF1 housekeeping genes using the cycle threshold (ΔCT) method [31].

Generation of mutant and RNAi Histoplasma strains

The transporter-deficient strain lacking the three major transporters was generated by isolation of an 8 base pair deletion of the GAP3 gene (located at nucleotide 25 of the CDS) using CRISPR/Cas9 [32] in the RNAi sentinel strain, OSU194. The Gai1 and Dip5 transporters were subsequently depleted via RNA interference with a GFP sentinel as previously described (RNAi [33]) using a chimeric RNAi construct consisting of 579 and 771 base pair regions of GAI1 and DIP5, respectively. Knockdown of DIP5 and GAI1 was monitored by quantification of the sentinel GFP fluorescence using a modified gel documentation system and ImageJ software (v1.44p) or using a BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader.

Assays for Histoplasma utilization of amino acids and peptides

Wild-type Histoplasma G217B or the transporter-deficient yeasts were grown to late log phase, rinsed twice, and resuspended in 3 M minimal media with carbon and nitrogen sources at 20 mM and 2 mM concentrations, respectively. To test amino acids as a source of nitrogen, 20 mM of glucose was included in the media (Figure 1a). To test metabolism of free amino acids as a source of carbon, 2 mM of ammonium sulfate was included in the media (Figure 1b). Due to low solubility, tyrosine was tested only at 2 mM concentration in both experiments. To test metabolism of peptides, hemoglobin or gelatin (2%) were incubated at 37°C for 24 h with proteinase K (75 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), trypsin (30 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich), or cathepsin D (15 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) and added to 3 M media lacking any carbon or nitrogen in 48-well plates. Growth of yeasts in peptide digests was measured as turbidity (optical density at 595 nm) following incubation at 37°C with continuous shaking at 200 rpm.

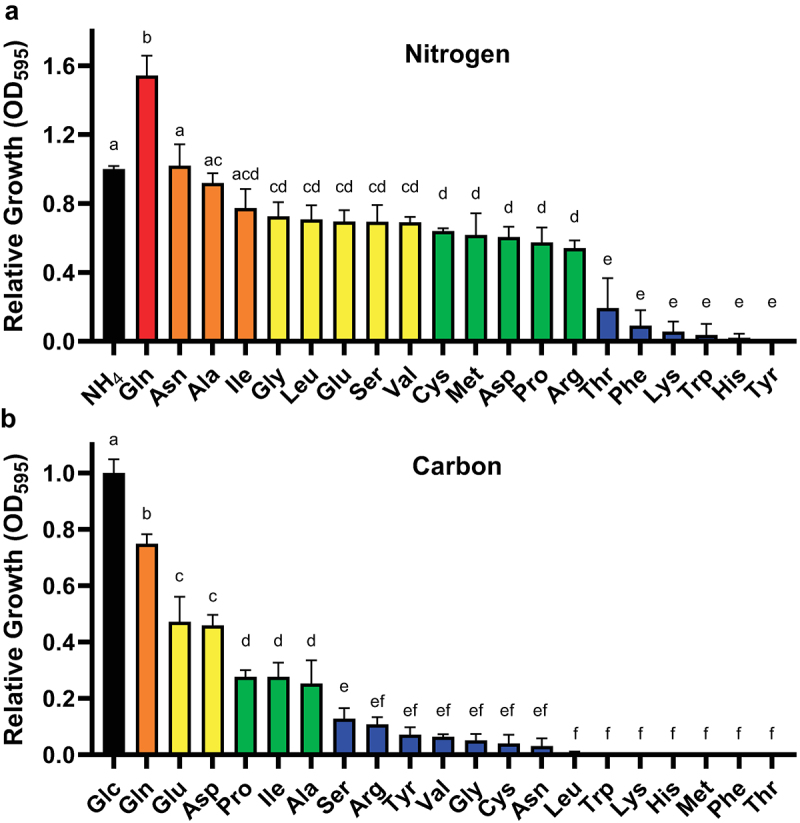

Figure 1.

H. capsulatum utilizes a range of amino acids as the sole nitrogen or carbon source.

Growth of wild type Histoplasma yeast in minimal media containing individual amino acids as the sole nitrogen (a) or carbon (b) source. Growth is shown relative to media containing ammonium sulfate (NH4) for nitrogen (A) or glucose (Glc) for carbon (B). Histoplasma yeast growth was measured via culture optical density at 595 nm after 7 days of growth. Colors correspond to quality of the substrate as a nitrogen (A) or carbon (B) source: red = excellent; orange = good; yellow = fair; green = poor; blue = negligible. Error bars represent standard deviation between 3 biological replicates. Bars annotated with the same letters denote no significant difference between means as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (α = 0.05).

Macrophage infections

Infection of cultured macrophages used a LacZ-expressing P388D1 murine cell line [34]. Macrophages were cultivated in Ham’s F12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma) and incubated at 37°C with a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. Macrophages were infected with H. capsulatum yeasts at an MOI (yeasts:macrophages) of 1:3 for intramacrophage CFU enumeration or 1:1 for macrophage killing assays. After 2 hours of infection, non-internalized yeasts were removed by replacing with fresh media. Intracellular proliferation of H. capsulatum was determined by lysing macrophages with H2O and plating of serial dilutions of the lysate onto solid HMM media for enumeration of colony forming units (CFUs). For macrophage killing assays, surviving macrophages were quantified by measurement of the remaining LacZ activity relative to that of uninfected macrophages [34].

Murine model of histoplasmosis

To model respiratory and disseminated histoplasmosis, a sublethal inoculum (4×104 H. capsulatum yeasts) was introduced intranasally into isoflurane-anesthetized wild type male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River). At 8 days post-infection, lungs and spleens were collected, tissue was homogenized in HMM, and dilutions of the homogenates plated on solid HMM media for CFU enumeration. Animal experiments were performed in compliance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at The Ohio State University [protocol# 2007A0241].

Statistical analyses

Experimental data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (v9.5.0) for determination of statistically significant differences, which are indicated in figures with letters (same-lettered groups are not statistically different) or with asterisks (n.s., not significant; *, p < 0.05). Statistical tests used are indicated in figure legends of associated data. Data were collected from 3 biological replicates (n = 3) unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Histoplasma metabolizes select amino acids for growth

Given the importance of gluconeogenesis for Histoplasma virulence [15], we investigated which amino acids could support Histoplasma yeast growth as potential phagosomal sources of carbon or nitrogen. Utilization of specific amino acids was tested by measuring yeast growth on individual amino acids as the sole nitrogen or carbon source. With glucose as the carbon source, Histoplasma yeasts utilized most amino acids for nitrogen, except threonine, phenylalanine, lysine, tryptophan, histidine, and tyrosine (Figure 1a). Glutamine in particular provided an excellent nitrogen source for Histoplasma yeasts, consistent with glutamine as a preferred nitrogen source in other fungi [35]. With ammonium as the nitrogen source, a more restricted set of amino acids could supply needed carbon: glutamine, glutamate, aspartate, proline, isoleucine, and alanine (Figure 1b). Interestingly, many amino acids that could supply nitrogen were insufficient sources of carbon, even when provided in 10-fold excess (as carbon versus nitrogen). Tyrosine cannot be fully ruled out as a carbon source, as its solubility required testing at a 10-fold lower concentration compared to the other amino acids. Thus, Histoplasma yeasts can metabolize amino acids, but they are limited to select amino acids for nitrogen and particularly carbon.

The Histoplasma genome encodes 28 putative amino acid transporters

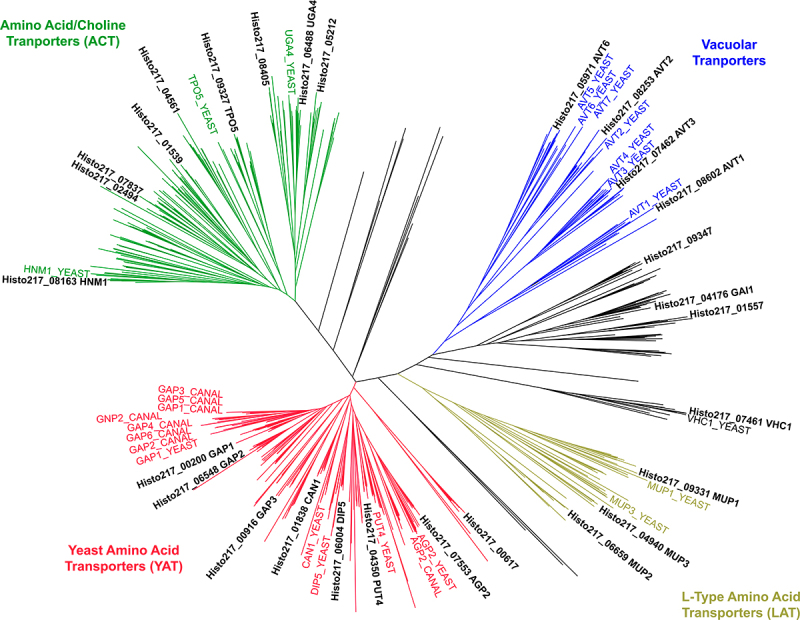

For yeast metabolism of amino acids, amino acids must first be imported into the cell via plasma membrane-localized transporters. Therefore, we identified the predicted amino acid transporters encoded in the Histoplasma genome. A hidden Markov model (HMM) search of the Histoplasma predicted proteome using the Pfam domains PF00324 (AA_permease), PF01490 (Aa_trans), and PF13520 (AA_permease_2) yielded 28 putative amino acid transporters belonging to the amino acid-polyamine-organocation (APC) superfamily of transporters (Table 1). To assign orthology with other fungal amino acid transporters, these proteins and 499 transporter protein sequences from other fungi were aligned and their evolutionary relatedness inferred by construction of a phylogenetic tree (Figure 2). The putative Histoplasma transporters separated into 5 major clades, corresponding to groups from the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB): 2.A.3.10 (YAT, Yeast Amino Acid Transporters), 2.A.3.8 (LAT, L-type Amino Acid Transporters), 2.A.3.4 (ACT, Amino Acid/Choline Transporters), and 2.A.18 (AAAP, amino acid/auxin permeases), which includes the vacuolar transporter (AVT) clade and a second less-defined clade with transporters with a range of reported substrate specificities. Assignment of Histoplasma transporter designations was based on orthology to experimentally characterized transporters, chiefly from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Histoplasma has three transporters corresponding to the general amino acid permeases (Gap transporters) of S. cerevisiae which were designated Gap1, Gap2, and Gap3. Within the same Yeast Amino Acid Transporter clade, transporters orthologous to S. cerevisiae Can1 (arginine permease), Dip5 (dicarboxylic amino acid permease), Put4 (proline utilization), and Agp2 (plasma membrane sensor) were identified as well as one transporter (Histo217_00617) which did not have an orthologous transporter in the Hemiascomycetes. Histoplasma’s L-type amino acid transporters included three proteins designated Mup1, Mup2, and Mup3 due to similarity to S. cerevisiae Mup (methionine uptake) proteins. The Amino Acid/Choline Transport clade contained diverse putative transporters, and reliable orthologs were identified for Uga4 (S. cerevisiae GABA permease), Tpo5 (putative transporter of polyamines), and Hnm1 (putative transporter of choline, ethanolamine, and carnitine). Multiple Histoplasma proteins were found in the Vacuolar Transporter clade that were orthologs to S. cerevisiae Avt1, Avt2, Avt3, and Avt6 (amino acid vacuolar transport). In addition, Histoplasma has a Vhc1 ortholog (vacuolar protein homologous to cation-chloride cotransporters). Similar to, but not within the Vacuolar Transporter clade is a large group of putative transporter proteins absent in the Hemiascomycetes. One of these we named Gai1 (general amino acid importer 1) based on its deduced transport ability (see below).

Table 1.

The Histoplasma genome encodes 28 putative amino acid transporters.

| Histoplasma Gene ID (35) | NCBI Accession # | Designation | Yeast FPKM (35) | Mycelia FPKM (35) | Y:M Ratio |

TCDB best fungal hit | e value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Amino Acid Transporters (YAT) | 06004 | KAG5291756.1 | DIP5 | 375.50 | 271.87 | 1.381 | 2.A.3.10.13 | 0.00E + 00 |

| 00916 | KAG5292284.1 | GAP3 | 339.80 | 10.25 | 33.151 | 2.A.3.10.24 | 1.00E–113 | |

| 01838 | KAG5298552.1 | CAN1 | 94.38 | 9.83 | 9.601 | 2.A.3.10.4 | 1.00E–175 | |

| 04350 | KAG5293028.1 | PUT4 | 49.34 | 69.49 | 0.710 | 2.A.3.10.17 | 1.00E–158 | |

| 07553 | KAG5297634.1 | AGP2 | 24.89 | 63.98 | 0.389 | 2.A.3.10.19 | 1.00E–143 | |

| 00617 | KAG5291949.1 | 7.52 | 111.89 | 0.067 | 2.A.3.10.20 | 1.00E–54 | ||

| 06548 | KAG5288319.1 | GAP2 | 4.46 | 17.95 | 0.248 | 2.A.3.10.24 | 1.00E–154 | |

| 00200 | KAG5301200.1 | GAP1 | 3.77 | 14.14 | 0.267 | 2.A.3.10.24 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| L-Type AA Transporters (LAT) | 06659 | KAG5287964.1 | MUP2 | 44.77 | 8.56 | 5.230 | 2.A.3.8.4 | 1.00E–40 |

| 09331 | KAG5295090.1 | MUP1 | 14.29 | 11.72 | 1.219 | 2.A.3.8.4 | 1.00E–157 | |

| 04940 | KAG5296624.1 | MUP3 | 13.29 | 5.83 | 2.280 | 2.A.3.8.4 | 1.00E–56 | |

| Amino Acid/Choline Transporters (ACT) | 09327 | KAG5295083.1 | TPO5 | 41.81 | 24.36 | 1.716 | 2.A.3.4.2 | 1.00E–97 |

| 08163 | KAG5297000.1 | HNM1 | 38.45 | 21.10 | 1.822 | 2.A.3.4.1 | 0.00E + 00 | |

| 02494 | KAG5292451.1 | 21.48 | 44.07 | 0.487 | 2.A.3.4.2 | 1.00E–67 | ||

| 07837 | KAG5297226.1 | 18.95 | 11.51 | 1.646 | 2.A.3.4.2 | 1.00E–82 | ||

| 04561 | KAG5297906.1 | 15.09 | 67.46 | 0.224 | 2.A.3.4.1 | 1.00E–37 | ||

| 05212 | KAG5302217.1 | 9.04 | 17.50 | 0.517 | 2.A.3.4.3 | 1.00E–75 | ||

| 01539 | KAG5291448.1 | 8.83 | 20.11 | 0.439 | 2.A.3.4.2 | 1.00E–69 | ||

| 08405 | KAG5297354.1 | 5.09 | 12.80 | 0.398 | 2.A.3.4.3 | 1.00E–80 | ||

| 06488 | KAG5301877.1 | UGA4 | 5.04 | 1.45 | 3.476 | 2.A.3.4.3 | 1.00E–132 | |

| Vacuolar Transporters | 08602 | KAG5287070.1 | AVT1 | 65.28 | 17.22 | 3.791 | 2.A.18.5.2 | 1.00E–118 |

| 07462 | KAG5290114.1 | AVT3 | 29.58 | 6.15 | 4.810 | 2.A.18.7.3 | 1.00E–176 | |

| 08253 | KAG5297544.1 | AVT2 | 24.77 | 23.84 | 1.039 | 2.A.18.6.20 | 1.00E–96 | |

| 05971 | KAG5291793.1 | AVT6 | 20.42 | 11.84 | 1.725 | 2.A.18.6.6 | 1.00E–94 | |

| Unclassified | 04176 | KAG5292887.1 | GAI1 | 619.46 | 16.61 | 37.294 | 2.A.18.4.2 | 1.00E–81 |

| 07461 | KAG5290113.1 | VHC1 | 37.32 | 17.14 | 2.177 | no hits | ||

| 01557 | KAG5291464.1 | 21.61 | 18.70 | 1.156 | 2.A.18.4.2 | 1.00E–41 | ||

| 09347 | KAG5295107.1 | 18.71 | 21.50 | 0.870 | 2.A.18.4.2 | 1.00E–62 |

Figure 2.

Phylogeny of Histoplasma’s 28 predicted amino acid transporters.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree containing 28 predicted H. capsulatum amino acid transporters as well as 499 fungal proteins containing the PF00324 (AA_permease), PF01490 (Aa_trans), or PF13520 (AA_permease_2) Pfam domains. The predicted Histoplasma amino acid transporters separated into 5 broad clades: yeast amino acid transporters (YAT, red), L-type amino acid transporters (LAT, yellow), vacuolar transporters (blue), amino acid/choline tranporters (ACT, green), or unclassified (black). Relevant S. cerevisiae (“YEAST”) and C. albicans (“CANAL”) homologs are highlighted in their respective clade colors. A detailed cladogram is at Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27188757).

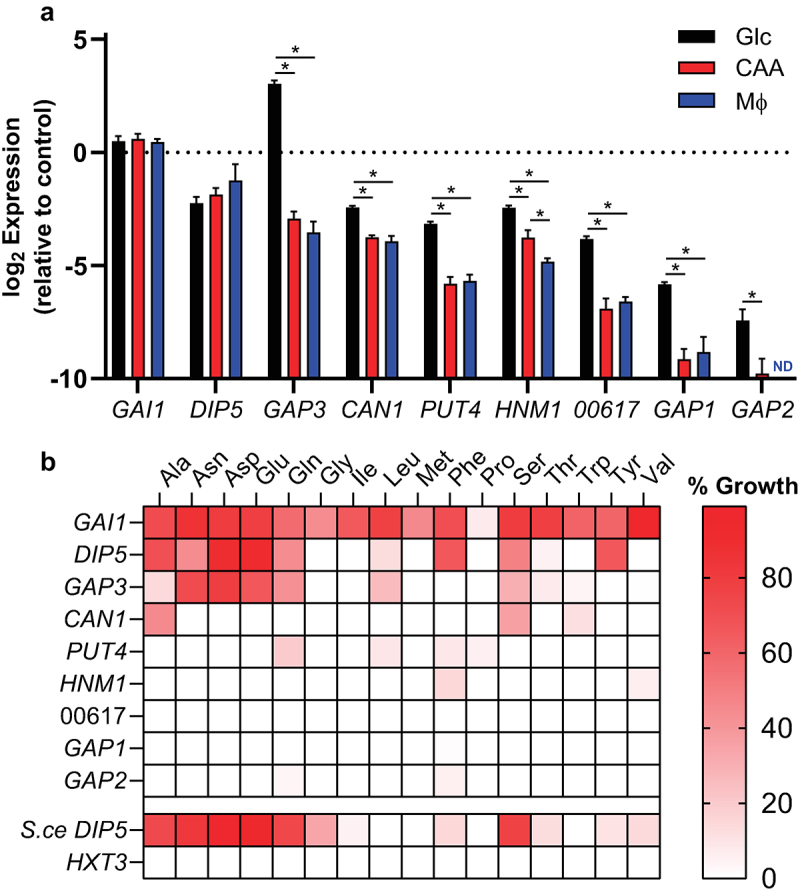

Histoplasma undergoes broad transcriptional rewiring upon transition between the avirulent mycelia and the pathogenic yeast phases. As genes important for Histoplasma virulence often show upregulation in the yeast phase [36,37], the relative transcription of each transporter-encoding gene was initially compared using previously published RNAseq datasets collected from Histoplasma yeast and mycelia [36]. In yeasts, the genes DIP5, GAP3, and GAI1 showed the overall highest expression (Table 1). GAI1 and GAP3 transcription showed enhanced expression in yeasts compared to mycelia (37- and 33-fold, respectively) suggesting functions linked to Histoplasma pathogenesis. Some transporter-encoding genes were transcribed at higher levels in mycelia, such as the unannotated genes Histo217_00617 and Histo217_04561. For subsequent transcriptional profiling, we prioritized 9 genes encoding putative plasma membrane-localized transporters: those with overall high or yeast-phase-enriched expression (GAI1, DIP5, and GAP3) and orthologs of characterized non-vacuolar Saccharomyces amino acid transporters (CAN1, PUT4, HNM1, GAP1, GAP3, and Histoplasma 00617). To determine whether these transporters are expressed during macrophage infection, we directly measured their expression in yeasts recovered from infected macrophages and compared gene expression to that of yeasts grown in minimal media with glucose and ammonium sulfate as the carbon and nitrogen sources or yeasts grown in minimal media with casamino acids as the carbon/nitrogen source. Seven genes showed significant upregulation in minimal glucose/ammonium media compared to growth on amino acids or inside macrophages (Figure 3a). Of these, GAP3 was the most upregulated in glucose (approximately 65-fold). Notably, for all genes except HNM1 (which had slightly higher expression in amino acid-containing media versus intracellular), there was no significant difference in expression between growth on amino acids versus residence within macrophages, suggesting the macrophage phagosome is most similar to an environment with amino acids rather than hexoses [13,15]. The GAI1 and DIP5 genes showed no regulation but consistent high overall expression in yeasts.

Figure 3.

The Gai1, Dip5, and Gap3 permeases comprise most of Histoplasma’s amino acid transport capacity.

(a) Relative gene expression of H. capsulatum amino acid transporters from yeasts grown in minimal media containing glucose and ammonium sulfate (“Glc,” black bars), casamino acids (“CAA,” red bars), or during intracellular growth in cultured macrophages (“MΦ,” blue bars). Gene expression is shown relative to the average expression of three Histoplasma housekeeping genes (ACT1, RPS15, and TEF1; dotted horizontal line). Error bars represent standard deviation for 3 biological replicates. Asterisks denote statistically significant expression differences as determined via Student’s t test (*, p < 0.05). Pairs lacking asterisks were not significantly different. ND = not detected. (b) Growth of the amino acid permease-deficient S. cerevisiae strain 22Δ10α on individual amino acids following transformation with heterologously expressed Histoplasma genes encoding amino acid transporters, as well as the native S. cerevisiae Dip5 transporter (S.ce DIP5) and the H. capsulatum hexose transporter-encoding gene HXT3. Growth is normalized for each amino acid the growth of wild-type S. cerevisiae (100%) and the transporter-deficient strain 22Δ10α (0%). Growth data on each amino acid is the average of 3 biological replicates.

Histoplasma Gap3, Dip5, and Gai1 provide the majority of amino acid import

To investigate the substrate specificities of Histoplasma’s putative amino acid transporters, their ability to provide amino acid import to an amino acid-transporter-deficient S. cerevisiae strain was tested. Histoplasma genes encoding the transporters were heterologously expressed in S. cerevisiae strain 22Δ10α, which lacks 10 amino acid transporters and is unable to import amino acids [28]. Transport of individual amino acids was inferred by the ability of each Histoplasma gene to confer growth to the S. cerevisiae yeasts when provided single amino acids as the sole nitrogen source (Figure 3b). Growth was measured in a gradient of amino acid concentrations and normalized to growth of wild type S. cerevisiae on each amino acid substrate to account for any differences in Saccharomyces metabolic capacity. Zero percent growth was defined as growth of the transporter deficient strain (22Δ10α) transformed with an empty vector. As an approximation of the substrate specificity of the Histoplasma transporters, the area under the curve of growth across all concentrations was determined once early stationary phase was reached in the wild type strain at the highest amino acid concentration. As cysteine, histidine, and lysine cannot be utilized by S. cerevisiae as nitrogen sources, these amino acids were unable to be tested as growth substrates [28,38]. Arginine also could not be tested as it is readily taken up even in the transporter-deficient S. cerevisiae strain [28]. Heterologous expression of Histoplasma GAI1 conferred growth on all tested amino acids, making it the most promiscuous transporter of those tested (Figure 3b). DIP5 showed a more narrow substrate range, with aspartate and glutamate being the most readily imported, followed by phenylalanine, tyrosine, alanine, serine, asparagine, glutamine, and leucine. GAP3, despite its homology to general amino acid permeases, showed a similar substrate specificity to DIP5, with aspartate, asparagine, glutamate, and glutamine supporting S. cerevisiae growth, along with serine, leucine, alanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine to a much lesser extent. The remaining genes tested were extremely limited in their ability to facilitate growth of Saccharomyces on amino acids, both in terms of the number of amino acids transported as well as the degree of transport. While Can1 has been reported as a basic amino acid permease in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans [39,40], the Histoplasma Can1 transporter facilitated S. cerevisiae growth on alanine, serine, and tryptophan, but only marginally. Other Histoplasma transporters provided less than 50% relative growth on few amino acids (Figure 3b). Despite their homology to general amino acid permeases, the Histoplasma Gap2 and Gap1 transporters provided little amino acid import and growth to S. cerevisiae. Histoplasma Gap1 (also referred to as HcCyn1) has previously been demonstrated to confer cystine transport to S. cerevisiae [41], highlighting the possibility of other substrates for these transporters. Overall, GAI1, DIP5, and GAP3 were the most effective Histoplasma transporters of amino acids in this heterologous expression system.

To validate that the observed amino acid transport was permease-specific, we tested growth of S. cerevisiae expressing the Histoplasma HXT3 gene, which is predicted to transport glucose. As expected, no difference in growth on amino acids was observed between the HXT3-expressing strain and S. cerevisiae transformed with the empty vector control. As a positive control, the native S. cerevisiae DIP5 gene (S.ce DIP5) was expressed and resulted in transport of dicarboxylic amino acids, consistent with what has been reported in the literature [39].

Loss of Gap3, Dip5, and Gai1 impairs Histoplasma growth on free amino acids

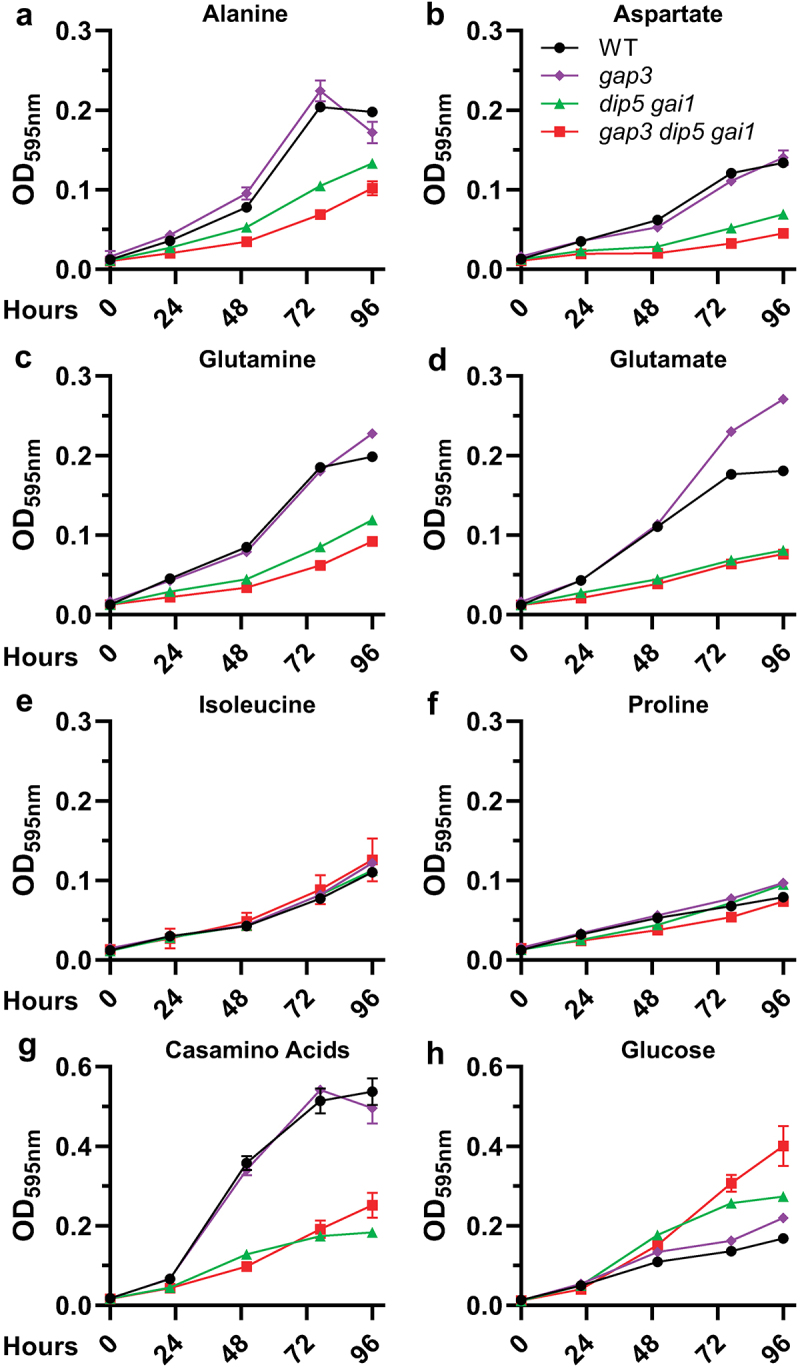

As GAP3, DIP5, and GAI1 are the most highly expressed amino acid transporter genes in Histoplasma yeast, and given the overlap between their transported substrates when expressed in Saccharomyces with the profile of amino acids that Histoplasma can metabolize (Figure 1), we tested whether loss of these transporters prevented Histoplasma yeast growth on amino acids. Given the potential redundancy of the transporters (Figure 3b), we created a strain deficient in all three transporters via a combination of CRISPR/Cas9-based gene disruption (GAP3) and RNA interference (RNAi; DIP5 and GAI1). This triple transporter-deficient strain, along with the gap3 single deletion strain and a DIP5/GAI1 double-deficient strain, were tested for growth on individual amino acids capable of supporting growth as both the carbon and nitrogen source (Figure 1) as an indication of amino acid uptake and utilization. Compared to wild-type Histoplasma yeasts, the triple transporter-deficient strain grew poorly in media with alanine, aspartate, glutamine, or glutamate (Figure 4a–d). The triple-transporter-deficient strain grew as well as wild type on both proline and isoleucine, although wild type itself showed poor growth on these amino acids (Figure 4e,f). Most importantly, compared to wild-type yeasts, the Histoplasma transporter-deficient strain showed a marked reduction (78% reduced) in growth rate on casamino acids, an acid hydrolysate of casein containing a mixture of all free amino acids (Figure 4g). Of the three transporters tested, Gap3 contributed the least to the observed phenotypes, as deletion of Gap3 alone had no effect on growth compared to wild type yeasts, save for a slight increase in final density with glutamate (Figure 4d). Depletion of Dip5 and Gai1 gave an intermediate phenotype compared to the triple deficient strain only when grown on alanine, aspartate, and glutamine, but showed a similarly severe reduction in growth rate to the triple deficient strain on casamino acids (83% lower than that of wild-type), suggesting Dip5 and Gai1 are the predominant amino acid transporters in Histoplasma yeasts.

Figure 4.

A Gap3 Dip5 Gai1 triple-transporter deficient strain of Histoplasma grows poorly on most amino acids.

Growth of wild type (“WT,” black circles), gap3 mutant (“gap3,” purple diamonds), DIP5/GAI1-deficient (“dip5 gai1,” green triangles), and triple deficient (“gap3 dip5 gai1,” red squares) Histoplasma yeasts on alanine (a), aspartate (b), glutamine (c), glutamate (d), isoleucine (e), proline (f), casamino acids (g), or glucose and ammonium sulfate (H) as the carbon and nitrogen source(s). Growth was measured as yeast culture optical density at 595 nm over time (hours, x-axis). Error bars represent standard deviation among 3 biological replicates.

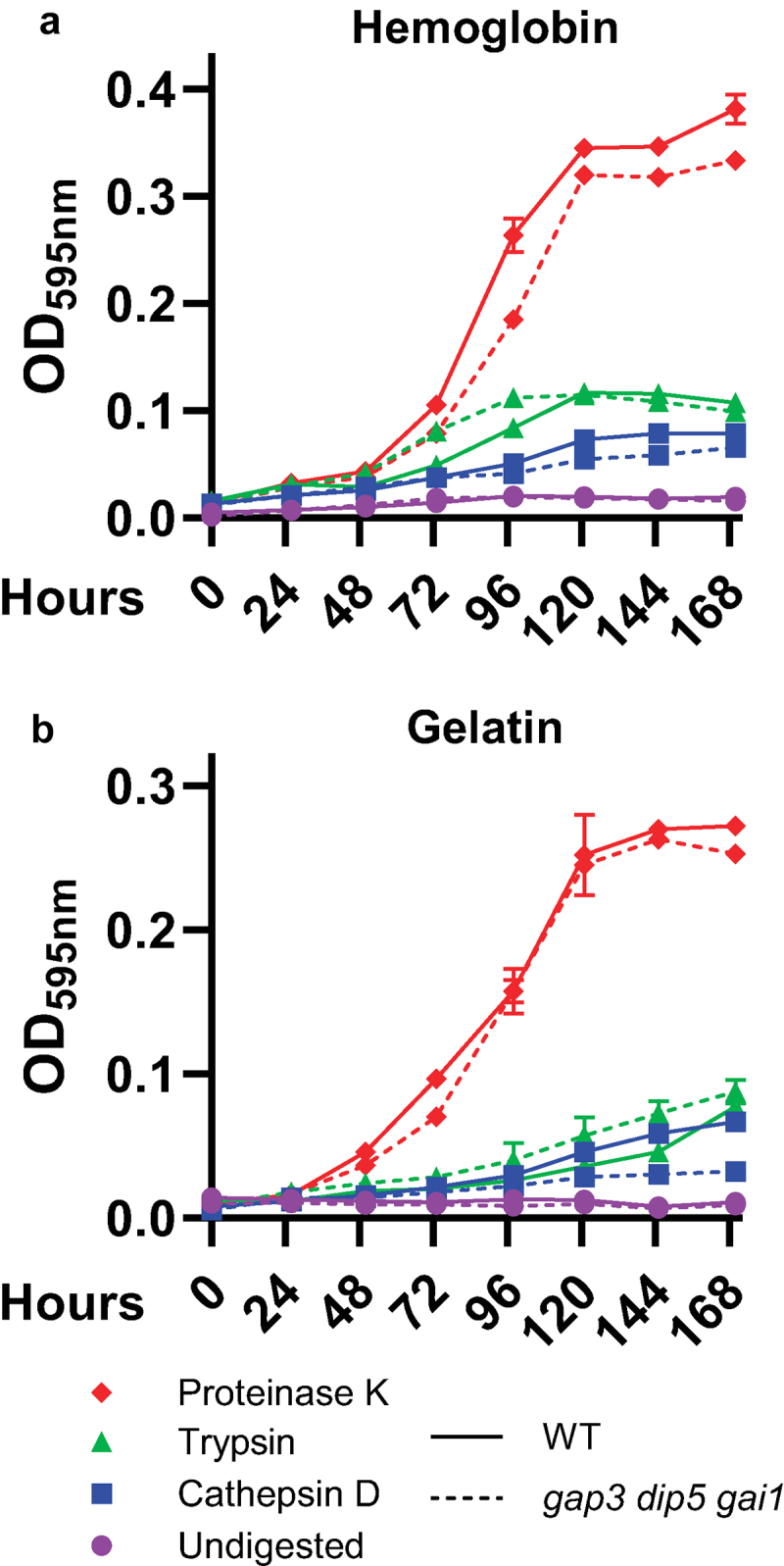

During infection, proteins and peptides could provide a source of amino acids for intracellular proliferation of Histoplasma yeasts. While the strain of H. capsulatum yeast used in this study is not known to secrete proteases, Histoplasma has the capacity to grow on short peptides, with more extensive digestion of proteins corresponding with increased growth of the fungus [15,42,43]. To test whether depletion of Histoplasma GAP3, DIP5, and GAI1 amino acid transporters impaired utilization of peptides (i.e. digested proteins), we grew Histoplasma yeast in minimal media containing either hemoglobin or gelatin as the sole carbon and nitrogen source, as well as hemoglobin or gelatin digested with cathepsin D (a phagosomal proteinase), trypsin, or proteinase K (Figure 5). Consistent with previously published data, neither wild type Histoplasma nor the permease-deficient strain was able to grow on undigested protein [15]. Digestion of proteins into peptides facilitated growth of Histoplasma yeasts, and production of shorter peptides (as would be expected from treatment with proteinase K, which has broader protein cleavage specificity) was associated with better Histoplasma growth on both protein substrates. However, only slight differences in growth were observed between the wild type and the triple amino acid transporter-deficient strain on these peptide-containing media (Figure 5a–b) consistent with the Gap3, Dip5, and Gai1 transporters being specific for free amino acids. Wild-type yeasts grew slightly better than permease-deficient yeasts on cathepsin D-treated gelatin after 4 days of growth (Figure 5b), but overall growth on this substrate was extremely poor, and this difference was not mirrored in the cathepsin D-treated hemoglobin condition. Therefore, while depletion of Gap3, Dip5, and Gai1 impairs growth on free amino acids, these transporters are not necessary for import of peptide substrates.

Figure 5.

Loss of amino acid transport does not impair growth on digested protein.

Growth of wild type (solid lines) Histoplasmayeast and a strain deficient in the Gap3, Dip5, and Gai1 transporters (dashed lines) in media containing 1% hemoglobin (a) or gelatin (b) which had been pre-treated with proteinase K (red diamonds), trypsin (green triangles), cathepsin D (blue squares), or left undigested (purple circles). Growth was measured as yeast culture optical density at 595 nm over time (hours, x-axis). Error bars represent standard deviation between 3 biological replicates.

Intriguingly, the GAP3/DIP5/GAI1-deficient yeasts consistently reached saturation more rapidly than wild type Histoplasma yeast when grown on minimal glucose medium (Figure 4h). As all Histoplasma strains were maintained on rich media containing both glucose and amino acids, this may reflect adaptation of the triple permease-deficient strain to media components other than amino acids, therefore priming this strain for growth on glucose-NH4 medium as suggested by the shorter lag before exponential growth in minimal glucose.

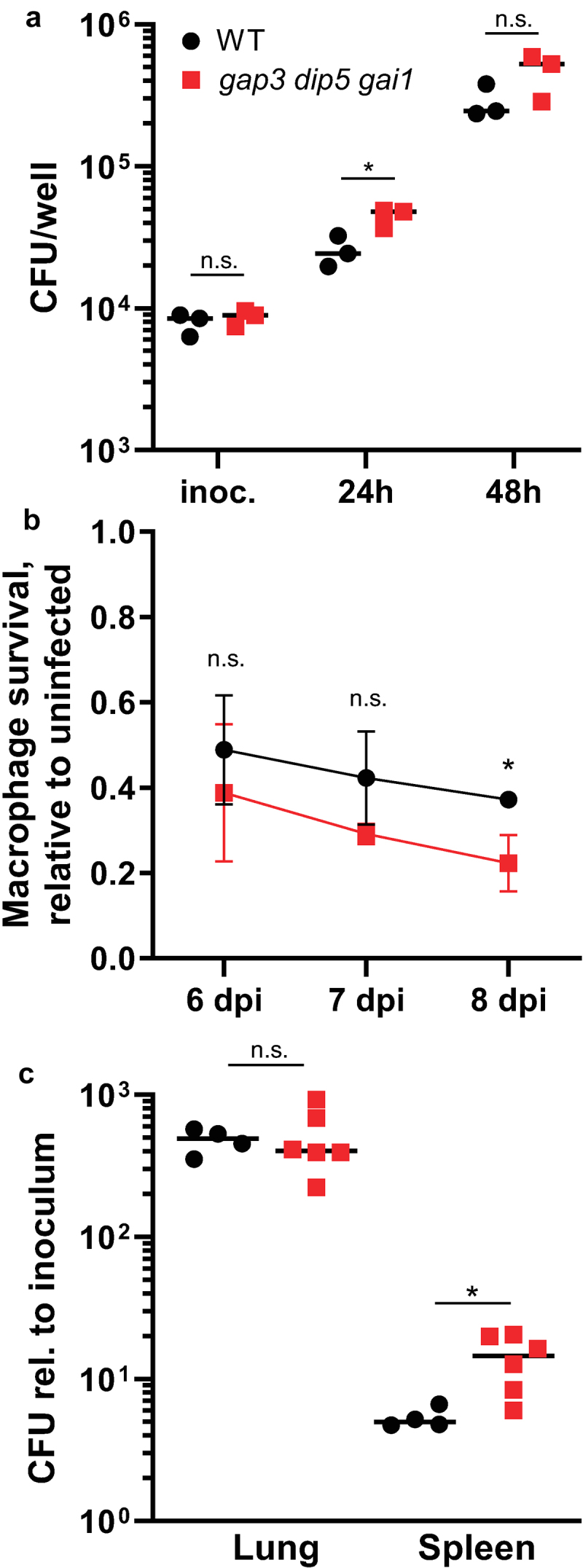

Histoplasma yeast virulence does not require the Gap3, Gai1, or Dip5 transporters

As previous work suggests that amino acid metabolism supports growth of Histoplasma yeasts within the macrophage phagosome [15], we tested whether amino acid import by yeasts is thus required for Histoplasma virulence by measuring the proliferation of Histoplasma yeasts lacking the GAP3/DIP5/GAI1 transporters inside cultured macrophages. Compared to wild-type Histoplasma yeasts, permease-deficient yeast were not attenuated in their ability to grow intracellularly (Figure 6a). This full proliferation in the absence of amino acid transport led to similar killing of cultured macrophages by Histoplasma yeasts (Figure 6b). As a further test of the contribution of amino acid import to Histoplasma virulence, the triple-transporter-deficient yeasts were tested for their ability to cause respiratory infections in mice. Since Histoplasma yeasts lacking gluconeogenic metabolism are known to be severely attenuated by 8 days post-infection [15], the peak of the fungal lung colonization, the murine infection of transporter-deficient yeasts was also examined at this time point. At 8 days post-infection, no difference was observed in the lung fungal burdens between wild type Histoplasma and the triple amino acid transporter-deficient strain (Figure 6c). There was a small but statistically significant increase in spleen fungal burdens in the permease-deficient strain compared to wild type yeast at 8 days post infection. Taken together, these results indicate the Gap3, Dip5, and Gai1 amino acid transporters are dispensable for Histoplasma proliferation in macrophages and virulence in vivo, suggesting metabolism of an intracellular nutritional source other than free amino acids.

Figure 6.

Amino acid transport-deficient Histoplasma yeasts are fully virulent in macrophages and in vivo.

(a-b) Cultured transgenic P388D1 LacZ-expressing macrophages were inoculated with either wild type (“WT,” black circles) or amino acid permease-deficient (“gap3 dip5 gai1,” red squares) Histoplasma yeasts. (a) At 24 and 48 hours post-infection, macrophages were lysed and intracellular yeast were quantified by enumerating colony forming units (CFU). (b) At 6, 7, and 8 days post-infection, macrophage viability was quantified using the remaining LacZ activity relative to uninfected controls to indicate Histoplasma lysis of macrophages. (c) Respiratory infections of C57BL/6 mice indicate in vivo virulence. Mice were infected intranasally with wild type (“WT,” black circles) or amino acid permease-deficient (“gap3 dip5 gai1,” red squares) Histoplasma yeasts. After 8 days post-infection, the fungal burdens in mouse lungs and spleens were quantified by plating of tissue homogenates. Data is plotted relative to the inoculum. In (a), points represent biological replicates. In (b), error bars represent standard deviation among 3 biological replicates. In (c), points represent CFU counts from individual mice. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences in growth as determined via Student’s t test (*, p < 0.05; n.s., not significant).

Discussion

H. capsulatum readily metabolizes amino acids for growth, especially as a nitrogen source. For carbon, however, Histoplasma yeasts show a clear growth preference for a subset of amino acids (at least when grown in vitro). Histoplasma expression of multiple amino acid transporters with broad substrate specificities (e.g. Gai1 and Dip5 transporters) suggests lack of transport of any individual amino acid is not responsible for the restricted set of amino acids as nutritional sources. Instead, the limited set of amino acids that provide carbon most likely arises from differences in catabolic pathway efficiency or differential regulation of amino acid catabolic pathways in Histoplasma yeasts. Of the 28 transporters identified in this study, those of the 2.A.3.10 family were the most highly expressed and two (GAP3 and GAI1) were particularly induced in yeasts compared to avirulent mycelia. Strikingly, the pattern of amino acid transporter expression by yeasts within macrophages largely resembled that of yeasts in an amino acid-rich environment (Figure 3(a)), not of an amino acid-limited environment. This suggests that nutritionally, the Histoplasma-containing phagosome is characterized by abundant amino acids, or alternatively the lack of non-amino acid substrates (e.g. hexoses), which is consistent with observations in other intracellular fungal pathogens [13,14].

While the amino acid transporter expression profiling suggests the phagosome contains amino acids to support Histoplasma metabolism, the identities of these amino acids and their intraphagosomal concentrations remain unknown. The full virulence of Histoplasma yeasts auxotrophic for tyrosine and phenylalanine demonstrates that the macrophage phagosome has sufficient tyrosine and phenylalanine to rescue these auxotrophies. However, the phagosome lacks sufficient tryptophan as tryptophan auxotrophs have attenuated growth in macrophages [11]. Thus, while Histoplasma has the necessary transporters to import amino acids during infection, the phagosome environment does not contain all amino acids in sufficient quantities to meet Histoplasma’s nutritional requirements.

Despite multiple lines of evidence indicating the phagosome environment has amino acids and that Histoplasma catabolizes amino acids during infection, preventing uptake of amino acids by depletion of the three major amino acid transporters does not attenuate Histoplasma virulence. The broad specificity for the amino acids transported by the Gai1, Gap3, and Dip5 transporters indicates a high degree of redundancy, which required simultaneous depletion of all three permeases to sufficiently block amino acid import. In contrast to the nearly 80% reduction in growth rate when grown on amino acids in vitro, the amino acid transporter-deficient strain showed full rates of proliferation within macrophages and was fully virulent in vivo, indicating amino acid import by these genes is not necessary for intracellular proliferation. It is possible that one of the other putative permeases identified could facilitate amino acid uptake within the phagosome. However, the expression of transporters other than Gai1, Gap3, and Dip5 is minimal, even during residence within macrophages. Furthermore, the capacity of Histoplasma’s other permeases to transport amino acids is very low and could not support growth on amino acids in the absence of Gai1, Gap3, and Dip5 when grown in vitro. An enticing alternative explanation is that small peptides, rather than free amino acids, are the source of amino acids during macrophage infection. Given that the phagosome harbors lysosomal proteolytic enzymes, such as cathepsins, the phagosome may harbor abundant proteolytic products. Thus, we hypothesize that host proteinases convert proteins into peptides, which then serve as the major nutritional carbon and/or nitrogen substrate(s) for Histoplasma yeasts inside the phagosome. Consistent with this, the strain of H. capsulatum used in this study cannot grow on undigested protein, but digestion of the protein into peptides as the carbon source can support growth of Histoplasma yeasts, including yeasts that lack the ability to import amino acids. Thus, Histoplasma’s success as an intracellular pathogen of phagocytes may result from exploitation of the proteolytic nature of the phagosome to provide peptides as a source of amino acids for metabolism to support intracellular yeast proliferation and virulence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Guillaume Pilot for kindly providing the S. cerevisiae amino acid transporter mutant strain 22Δ10α as well as the S. cerevisiae expression vector pDR196.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grant R01-AI148561 to C.A.R. S.C.R. was funded through a predoctoral fellowship sponsored by NIH/NIAID award 1-T32-AI-112542, an NRSA training grant administered by the Infectious Diseases Institute at The Ohio State University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, interpretation, or the submission of the work for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

SCR, QS, and CAR designed the experiments. SCR and CAR performed the experiments and data analyses. QS performed initial experiments on utilization of amino acids and contributed to data analysis. The manuscript was drafted by SCR, and revised by SCR, QS, and CAR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

Raw data are available via Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27188757).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2024.2438750

References

- [1].Ajello L. The medical mycological iceberg: a study of incidence and prevalence. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86(5):437–15. doi: 10.2307/4594192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Goodwin RA, Loyd JE, Des Prez RM. Histoplasmosis in normal hosts. Med. 1981;60(4):231–266. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198107000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(1):115–132. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00027-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Holbrook ED, Rappleye CA. Histoplasma capsulatum pathogenesis: making a lifestyle switch. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11(4):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shen Q, Beucler MJ, Ray SC, et al. Macrophage activation by ifn-γ triggers restriction of phagosomal copper from intracellular pathogens. PLOS Pathog. 2018;14(11):1–26. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dade J, DuBois JC, Pasula R, et al. Hc Zrt2, a zinc responsive gene, is indispensable for the survival of Histoplasma capsulatum in vivo. Med Mycol. 2016;54(8):865–875. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hwang LH, Mayfield JA, Rine J, et al. Histoplasma requires SID1, a member of an iron-regulated siderophore gene cluster, for host colonization. PLOS Pathog. 2008;4(4):e1000044. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hilty J, George Smulian A, Newman SL. Histoplasma capsulatum utilizes siderophores for intracellular iron acquisition in macrophages. Med Mycol. 2011;49:1–10. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.558930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Newman SL, Gootee L, Brunner G, et al. Chloroquine induces human macrophage killing of Histoplasma capsulatum by limiting the availability of intracellular iron and is therapeutic in a murine model of histoplasmosis. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(4):1422–1429. doi: 10.1172/JCI117119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Retallack DM, Heinecke EL, Gibbons R, et al. The URA5 gene is necessary for Histoplasma capsulatum growth during infection of mouse and human cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67(2):624. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.2.624-629.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shen Q, Gonzalez-Mireles A, Ray SC, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum relies on tryptophan biosynthesis to proliferate within the macrophage phagosome. Infect Immun. 2023;91(6). doi: 10.1128/iai.00059-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Garfoot AL, Zemska O, Rappleye CA, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum depends on de novo vitamin biosynthesis for intraphagosomal proliferation. Infect Immun. 2014;82(1):393–404. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00824-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lorenz MC, Bender JA, Fink GR. Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3(5):1076–1087. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.5.1076-1087.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fan W, Kraus PR, Boily MJ, et al. Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during murine macrophage infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4(8):1420–1433. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1420-1433.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shen Q, Ray SC, Evans HM, et al. Metabolism of gluconeogenic substrates by an intracellular fungal pathogen circumvents nutritional limitations within macrophages. MBio. 2020;11(2):11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02712-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lorenz MC, Fink GR. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature. 2001;412(6842):83–86. doi: 10.1038/35083594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McDonagh A, Fedorova ND, Crabtree J, et al. Sub-telomere directed gene expression during initiation of invasive aspergillosis. PLOS Pathog. 2008;4(9):e1000154. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Martho KFC, De Melo AT, Takahashi JPF, et al. Amino acid permeases and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0163919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kraidlova L, Schrevens S, Tournu H, et al. Characterization of the Candida albicans amino acid permease family: Gap2 is the only general amino acid permease and Gap4 is an S -adenosylmethionine (SAM) transporter required for SAM-Induced morphogenesis. mSphere. 2016;1(6). doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00284-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kraidlova L, van Zeebroeck G, van Dijck P, et al. The Candida albicans GAP gene family encodes permeases involved in general and specific amino acid uptake and sensing. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10(9):1219–1229. doi: 10.1128/EC.05026-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Garbe E, Miramón P, Gerwien F, et al. GNP2 encodes a high-specificity proline permease in Candida albicans. MBio. 2022;13(1). doi: 10.1128/mbio.03142-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Martínez P, Ljungdahl PO. An ER packaging chaperone determines the amino acid uptake capacity and virulence of Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51(2):371–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03845.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vylkova S, Carman AJ, Danhof HA, et al. The fungal pathogen candida albicans autoinduces hyphal morphogenesis by raising extracellular pH. MBio. 2011;2(3). doi: 10.1128/mBio.00055-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nicola AM, Robertson EJ, Albuquerque P, et al. Nonlytic exocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans from macrophages occurs in vivo and is influenced by phagosomal pH. MBio. 2011;2(4). doi: 10.1128/mBio.00167-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Westman J, Moran G, Mogavero S, et al. Candida albicans hyphal expansion causes phagosomal membrane damage and luminal alkalinization. MBio. 2018;9(5). doi: 10.1128/mBio.01226-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Worsham PL, Goldman WE. Quantitative plating of Histoplasma capsulatum without addition of conditioned medium or siderophores. Med Mycol. 1988;26(3):137–143. doi: 10.1080/02681218880000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, et al. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Besnard J, Pratelli R, Zhao C, et al. UMAMIT14 is an amino acid exporter involved in phloem unloading in Arabidopsis roots. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(22):6385–6397. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Frozen competent yeast cells that can be transformed with high efficiency using the LiAc/ss carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Meyer A, Eskandari S, Grallath S, et al. AtGAT1, a high affinity transporter for γ-aminobutyric acid in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(11):7197–7204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510766200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rappleye CA, Mitchell AP. Targeted gene deletions in the dimorphic fungal pathogen Histoplasma using an optimized episomal CRISPR/Cas9 system. mSphere. 2023;8(4). doi: 10.1128/msphere.00178-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rappleye CA, Engle JT, Goldman WE. RNA interference in Histoplasma capsulatum demonstrates a role for α-(1,3)-glucan in virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(1):153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Edwards JA, Zemska O, Rappleye CA, et al. Discovery of a role for Hsp82 in Histoplasma virulence through a quantitative screen for macrophage lethality. Infect Immun. 2011;79(8):3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05124-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Garbe E, Vylkova S. Role of amino acid metabolism in the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2019;6(3):108–119. doi: 10.1007/s40588-019-00124-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Edwards JA, Chen C, Kemski MM, et al. Histoplasma yeast and mycelial transcriptomes reveal pathogenic-phase and lineage-specific gene expression profiles. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):695. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Beyhan S, Gutierrez M, Voorhies M, et al. A temperature-responsive network links cell shape and virulence traits in a primary fungal pathogen. PLOS Biol. 2013;11(7):e1001614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bianchi F, van’t Klooster JS, Ruiz SJ, et al. Regulation of amino acid transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeMicrobiology and molecular biology reviews. American Society for Microbiology; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Regenberg B, Düring-Olsen L, Kielland-Brandt MC, et al. Substrate specificity and gene expression of the amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1999;36(6):317–328. doi: 10.1007/s002940050506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sychrová H, Chevallier MR. Transport properties of a C. albicans amino-acid permease whose putative gene was cloned and expressed in S. cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1993;24(6):487–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00351710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yadav AK, Bachhawat AK. CgCYN1, a plasma membrane cystine-specific transporter of candida glabrata with orthologues prevalent among pathogenic yeast and fungi. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(22):19714–19723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.240648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Holbrook ED, Edwards JA, Youseff BH, et al. Definition of the extracellular proteome of pathogenic-phase Histoplasma capsulatum. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(4):1929–1943. doi: 10.1021/pr1011697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zarnowski R, Connolly PA, Wheat LJ, et al. Production of extracellular proteolytic activity by Histoplasma capsulatum grown in Histoplasma-macrophage medium is limited to restriction fragment length polymorphism class 1 isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data are available via Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27188757).