Abstract

This retrospective study assesses the impact of India’s National Health Policy (NHP) 2017 on public health expenditure and its implications for achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG-3). Using secondary data analysis from government sources, we observed health budget trends relative to GDP from 2017 to 2022. The study found a marginal increase in public health expenditure from 0.9% to 1.6% of GDP, which is below the NHP’s target of 2.5%. The results underscore the challenge of high out-of-pocket expenses, which remain a barrier to UHC. The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the inadequacies of the current funding levels. We conclude that a substantial increase in health budget allocations is crucial for India to make significant strides toward UHC and meet SDG-3 targets. The study also calls for strategic enhancements in healthcare infrastructure and services to address the persistent gaps in healthcare delivery and financing. The findings advocate for a more aggressive approach to public health investment to ensure that quality healthcare services are accessible, affordable, and equitable for all citizens, thereby advancing India’s progress toward comprehensive health coverage.

Keywords: Budget, India, National Health Mission, Sustainable Development Goal, Universal Health Coverage

INTRODUCTION

In a developing country such as India, health financing is a critical aspect of the healthcare system. India launched its revised National Health Policy 2017 which emphasizes an increase in public health expenditure to 2.5% of the GDP in a time-bound manner. This increase in allocation is seen as a necessary step toward ensuring that quality healthcare services are accessible and affordable for all citizens, thereby reducing financial hardship associated with healthcare costs. The policy aligns with SDG 3.8 for achieving UHC.[1] Ensuring a healthy population that is more productive uses educational opportunities effectively and contributes to overall economic development.

Health financing in India involves various sources. The central and state governments fund health services, with the NHM receiving a significant portion of the health budget. Despite these efforts, out-of-pocket expenditure remains high. Health insurance, both public and private, also contributes to health financing. In addition, donations from NGOs and international grants support specific health programs. Each source is crucial for India’s pursuit of UHC, but challenges such as the need for increased public health expenditure and reduced out-of-pocket costs persist. India’s public health expenditure was 0.9% of GDP in 2015-16, which has merely increased to 1.6% of GDP in 2021-22 (against 5-10% global leverage). India ranks 179th among 189 countries in prioritizing healthcare in the government budget.[2] Also, India is among the top 10 countries in the world, incurring a very high magnitude of out-of-pocket expenditure.[3]

In response to these challenges, the NHP calls for a strategic partnership between the public and private sectors to fill health system gaps and a more significant investment in healthcare infrastructure, especially in the wake of inadequacies exposed by the pandemic. The policy’s focus on health financing is integral to India’s commitment to providing equitable, quality healthcare services to all its citizens and moving toward the achievement of UHC and SDG3.

As the National Health Policy completes its five years, this study aims to analyze the trends in Public Health Expenditure in India from 2017 to 2022 on the advancement of Universal Health Coverage and the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a record-based retrospective study using the secondary data of annual health budget records available in the open and public domain from the MoHFW and NHM websites.[4,5] The secondary data for health budget allocation were compared with health indicators (life expectancy, maternal mortality rate, child mortality rate, Human Development Index, out-of-pocket expenditure on health, and tuberculosis cases) to observe the trends in India from 2017 to 2022 (in the past five years). Descriptive data analysis has been used, and a bar graph and trends chart were plotted.

RESULTS

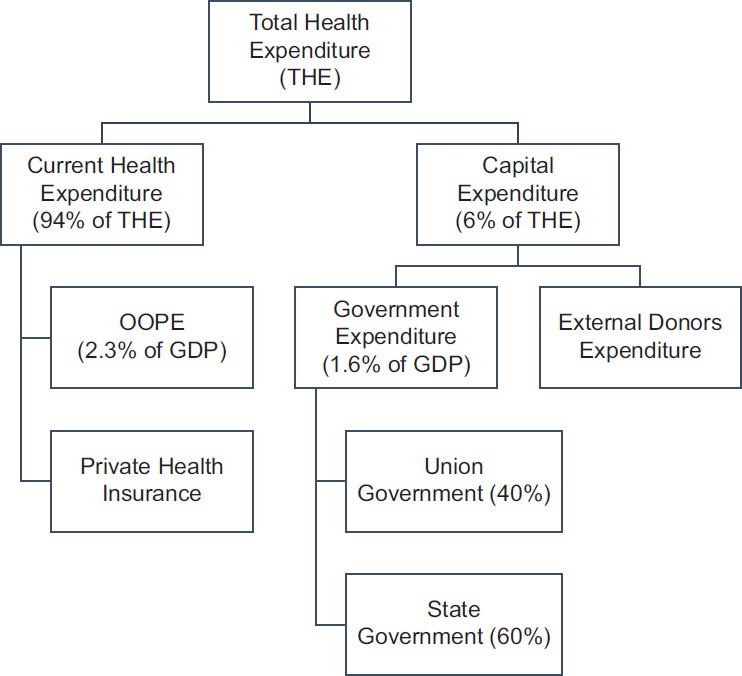

In India, most of the funding to the health sector comes through public expenditure. Under public expenditure, the center and state provide funds to the MoHFW, the State Department of Health and Family Welfare, and other related departments [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Allocation of budget[6]

In India, the budget breakdown allocated solely to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) shows that the bulk of the allocated sum goes to the NHM, strengthening the health system in rural and urban areas. The NHM envisages universal access to equitable, affordable, quality healthcare services that are answerable and approachable to people’s needs. In the 2022-23 annual budget, INR 37,000.23 crore, or 42.92 percent of the MoHFW budget, was allocated to the NHM.[7] Still, the allocation is a “negligible” increase compared with the revised estimate of Rs 85,915 crore for FY 2021-22.

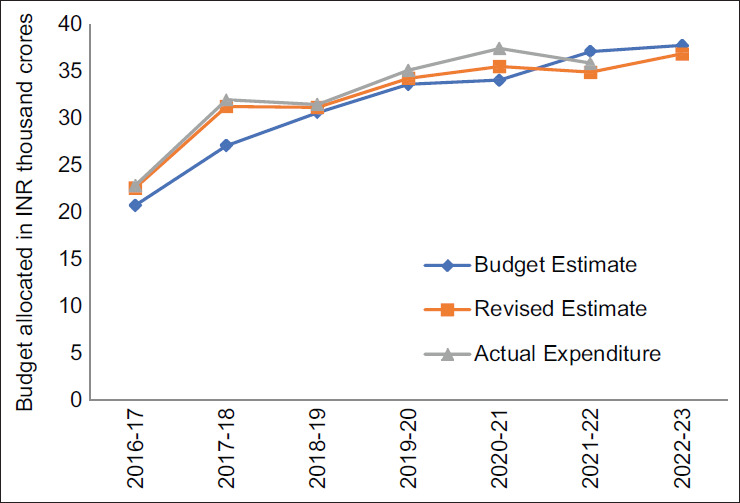

The budget allocated to the health department has increased incrementally to 38.7% from 2017 to 2021 [Figure 2]. Despite this increase in the funds allocated to the MoHFW, the funds allocated to NHM increased by only 18.7% in the past five years. Among all the heads of NHM expenditure, more than 50% of the money is spent on health systems strengthening. The utilization has been over 100% in the past five years, i.e. the Department exceeded its budget estimates.

Figure 2.

Budget allocation to National Health Mission

The maternal mortality rate has been significantly decreased, from 130 per 100,000 live births in 2017 to 97 in 2022 [Table 1]. In addition, during the same period, the child mortality rate significantly dropped, going from 39 per 1,000 live births to 23 (against 21 forecasted). As per the recommendations of National Health Policy 2017 and a 2.5% GDP contribution, there is likely to be a further decrease in MMR and IMR as more resources are allocated to maternal and child health services, including prenatal care, skilled birth attendance, and neonatal care programs. In India, resource allocations for the healthcare sector are skewed toward curative healthcare, neglecting the preventive and promotive aspects.

Table 1:

Comparison of basic health indicators in 2017 and 2022

| Indicator | 2017 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 69.96 | 70.62 |

| Maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 live births) | 130 | 97 |

| Child mortality rate (per 1,000 live births) | 39 | 23 |

| Human Development Index | 0.640 | 0.644 |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure on health (% of THE) | 58.7 | 52 |

| Tuberculosis cases (per 100,000 population) | 204 | 172 |

DISCUSSION

The actual expenditure of the MoHFW more than doubled but the NHM expenditure increased merely by 64% during the past five years. Although NHM is the most significant component of the expenditure incurred by MoHFW, its share in the total expenditure of the ministry fell from 58.6% in 2016-17 to 46.4% in 2020-21.[5] The share of expenditure on NHM of the total expenditure of the ministry has been declining over the years. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, 10% budget growth proved insufficient in bringing the country close to the NHP-2017 target.[8] In India, more than 50% of healthcare expenses are paid out of pocket, a significant proportion compared with economies such as China (around 30%) and Brazil (about 25%).

Thailand was the only LMIC country to introduce UHC reforms in 2001 successfully.[9] Thailand became the first country in Asia to eliminate HIV transmission from mother to child, owing to its robust public healthcare system in 2016.[10] But, India is still lacking than other countries in terms of health and other indicators. India’s health system ranked in the bottom third with an effective UHC coverage index score of 47 of 100.[11] According to the United Nations World Development Report 2020, India ranks 134th on the Human Development Index with a score of 0.644.[12] India has a higher infant mortality rate (<5 years) than Bangladesh and Nepal. The number of beds and doctors is worse than in other countries in the region, including China, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Nepal.[13]

Health financing in developed countries is often characterized by a robust mix of public and private funding, leading to better health indicators such as life expectancy and lower infant mortality rates. Developing countries, including India, tend to rely more on out-of-pocket payments, resulting in financial strain and poorer health outcomes. India’s healthcare spending is low compared with developed nations, and although there has been progress, significant investment is needed to bridge the gap in health indicators. India has one of the lowest public health expenditures compared with GDP in the world. India’s health expenditure is approximately 1.6% of GDP, lower than 7.6% on average for OECD countries and 3.6% on average for BRICS countries.[14]

CONCLUSION

The study reveals a modest rise in India’s health expenditure from 0.9% to 1.6% of GDP over five years, falling short of the ambitious National Health Policy 2017 target of 2.5% by 2025. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the inadequacy of current funding levels, with only a fraction of low- and middle-income countries projected to meet the recommended 5% GDP expenditure on health by 2040. India is taking bigger steps and trying to achieve its fullest potential, which can be aided by appropriate funding and policy-making with the proper execution of those policies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors want to thank Dr Sonu Goel and his team, Professor, PGIMER, Chandigarh, for their constant guidance and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.SDG Target 3.8 | Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/sdg-target-3.8-achieve-universal-health-coverage-(uhc)-including-financial-risk-protection. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 19]

- 2.Demand for Grants 2021-22 Analysis: Health and Family Welfare. PRS Legislative Research. Available from: https://prsindia.org/budgets/parliament/demand-for-grants-2021-22-analysis-health-and-family-welfare. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 18]

- 3.Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure)-India | Data. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicatorSH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=IN. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 11]

- 4.Home : National Health Mission. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/ [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 19]

- 5.India Budget | Ministry of Finance | Government of India 2022-23. Available from: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/ [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 19]

- 6.National Health Estimates (2018-19) released. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1858770. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 13]

- 7.Funds Allocated and Key Achievements made under National Health Mission. Available from: https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1782603. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 19]

- 8.Jain B, Garg S, Aggarwal P, Bahurupi Y, Singh M, Kumar R. Health budget in light of pandemic: Health reforms from mirage to reality. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2022;11:1–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_740_21. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_740_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Getzzg. How and why do countries make universal health care policies? Interplay of country and global factors. J Glob Health. 2021. Available from: https://jogh.org/2021/jogh-11-16003/ [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Thailand eliminates mother-to-child HIV transmission | CNN. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/06/07/world/thailand-hiv-mother-to-child-transmission-who/index.html. [Last accessed on 2022 Sep 11]

- 11.Lozano R, Fullman N, Mumford JE, Knight M, Barthelemy CM, Abbafati C, et al. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1250–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30750-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2020. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 19]

- 13.Physicians (per 1,000 people) | Data. Available from: https://data.worldbank.orgindicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS. [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 19]

- 14.Jain B, Garg S, Aggarwal P, Bahurupi Y, Singh M, Kumar R. Health budget in light of pandemic: Health reforms from mirage to reality. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11:1–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_740_21. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_740_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]