ABSTRACT

Antibiotic resistance is recognized as one of the major challenges in public health. The global spread of antibiotic resistance is the consequence of a constant flow of information across multi-hierarchical interactions, involving cellular (clones), subcellular (resistance genes located in plasmids, transposons, and integrons), and supracellular (clonal complexes, genetic exchange communities, and microbiotic ensembles) levels. In order to study such multilevel complexity, we propose to establish an experimental epidemiology model for the transmission of antibiotic resistance with the cockroach Blatella germanica. This paper reports the results of five types of preliminary experiments with B. germanica populations that allow us to conclude that this animal is an appropriate model for experimental epidemiology: (i) the composition, transmission, and acquisition of gut microbiota and endosymbionts; (ii) the effect of different diets on gut microbiota; (iii) the effect of antibiotics on host fitness; (iv) the evaluation of the presence of antibiotic resistance genes in natural- and lab-reared populations; and (v) the preparation of plasmids harboring specific antibiotic resistance genes. The basic idea is to have populations with higher and lower antibiotic exposure, simulating the hospital and the community, respectively, and with a certain migration rate of insects between populations. In parallel, we present a computational model based on P-membrane computing that will mimic the experimental system of antibiotic resistance transmission. The proposal serves as a proof of concept for the development of more-complex population dynamics of antibiotic resistance transmission that are of interest in public health, which can help us evaluate procedures and design appropriate interventions in epidemiology.

Key words: antibiotic resistance, experimental epidemiology, membrane computing, Blatella germanica

*These senior authors contributed equally.

TRANSMISSION OF ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE: THE PROBLEM

The problem of antibiotic resistance in hospital bacteria and the human community has been recognized by various organizations (1–3) as one of the greatest challenges to public health, which calls into question the maintenance and progress of modern medicine (4, 5). This alarm is based on the inability to treat and prevent infections caused by microorganisms that are resistant to all therapeutic alternatives available. In recent years, there have been some unexpected circumstances that have acted synergistically and have worsened the problem, namely, (i) a general failure to discover new antimicrobials; (ii) the exponential development of antibiotic resistance in overcrowded countries with serious health deficits and the global spread of multiresistant bacteria; (iii) the invasion by resistant bacteria of ecosystems (surface water and sewage, soil, animals, and food) and, particularly, the invasion of human intestinal microbiota; and (iv) a pollution environment with high concentrations of antibiotics, metals, and biocides that favor the selection of multiresistant bacteria and their persistence. An estimated 25,000 people die each year in Europe and the United States from antibiotic resistance (5).

The antibiotic resistance problem has been addressed during the last quarter of a century under the highly orthodox approach of “thinking” based on (i) the need to develop new antibiotics, (ii) reduced consumption of antimicrobials, and (iii) the control and preventive isolation of patients carrying resistant bacteria in hospitals. These strategies were effective in very early stages of the invasion by resistant bacteria and even in developed countries with high standards of public health. Unfortunately, the focus of the pharmaceutical companies on other areas of therapeutic research and the planetary globalization of resistance with the invasion of populations and ecosystems has radically changed the landscape for actions based on the above premises (6). In parallel with this conceptual stagnation, advances in molecular genetics and the biology of bacterial populations that have revealed the explosive evolution of resistance (it has been compared to a chain reaction where the same resistance gene in India emerging as the β-lactamase NDM-1 appears a few months later in the rest of the world) allow us to speculate that the spread is due to the interaction of transmission chain events that occur at different levels of the biological hierarchy (7).

It is no longer the classical transmission of bacteria from one space to another, but swarms of clonal complexes, the gene exchange of communities and even fragments of microbiota or complete microbiota (8–10), which requires attention. Antibiotic resistance genes (ABRs) can be located in transposons, integrons, and plasmids that are integrated in a bacterial cell, either in the chromosome or in replicons that form part of a community of bacteria that belong to a particular host that lives in a particular environment. In other words, ABRs can be successively located at different subcellular, cellular, and supracellular nested levels of the full ecosystem. All the previously mentioned ABR carriers are units of selection that can be simultaneously and independently chosen at the different environmental levels. Understanding ABR evolution is complex, since it is not just the result of antibiotic-driven selection of mutant resistant bacterial clones but, more properly, the consequence of a variety of trans-hierarchical interactions between all biological vehicles involved in the dissemination of the genetic information encompassing ABRs. Such multilevel complexity is difficult to address as a whole. Within each of these levels there are “epidemic” resistance genes and gene vectors (plasmids, transposons, or integrons) that accelerate global spread. However, is it possible to predict the dissemination of resistance?

THE ROLE OF MICROBIOTA IN ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE

The gut microbiome is a complex community of microorganisms that live in the digestive tracts of humans and other animals. It is essential to maintain homeostasis and the health of the host, since it is responsible for vitamin synthesis, energy supply, immune cell maturation, and defense against infectious pathogens, among other properties (11). In humans, there are large numbers of microorganisms (up to 1012 CFU/g material). Although the composition of this microbiota determines the health status of the organism, it is not a stable organization, undergoing a series of changes during human development. In contrast, an unbalanced microbiota (dysbiosis) is associated with many gastrointestinal as well as nongastrointestinal diseases (1, 4, 12). Anaerobic bacteria in particular, and more specifically those of the Bacteroides genus, are the most common bacterial species in the human microbiota, according to metagenomic studies (13). Intestinal bacteria, on the other hand, not only exchange resistance genes between them but can interact with bacteria passing through the colon, causing the acquisition and transmission of ABRs (14).

The increase in the number of ABRs is attributed to different causes including the composition of human gut microbiota, the selective pressure generated by the massive use of antibiotics, and social changes that have increased the transmission of resistant organisms (15, 16). Other factors include the age of individuals (17, 18) and social interchange (19). We should also add the fact that farm-raised animals are often treated with antibiotics in large quantities to improve their quality and prevent infection. Thus, pathogenic-resistant organisms propagated in livestock are a source of introduction to the food supply and could be widely disseminated in food products (20). The problem occurs when all these factors and treatments cause the emergence of resistant bacteria and the increase of their propagation (16).

EXPERIMENTAL EPIDEMIOLOGY: THE CONCEPT

It is not easy to measure the transmission of ABRs in human populations. However, we can mimic the process by using appropriate experimental models in which to test interventions and, ultimately, encourage public health recommendations. Experimental epidemiology began nearly a century ago, but its development has been very slow and it is currently an area of knowledge that remains poorly treated (21–25), particularly in its evolutionary and predictive aspects. Nevertheless, over the last few years new studies using several model systems with different levels of microbial complexity have been assayed and have revealed how host genes affect the microbiome and how the microbiome regulates host genetic programs (26). Model organisms are the best way to perform, under controlled conditions, different host-microbiome interactions and relationship experiments that are not affordable in human studies. In many cases, the genetic and genomic studies of hosts and microbes have proven essential in identifying key factors that enable symbiosis. Model systems are also revealing roles for the microbiome in host physiology ranging from mate selection (27) to skeletal biology (28) and lipid metabolism (29), to cite a few. With the increasing number of microbiome studies completed and underway, experimental systems using model organisms are proving to be essential tools to interrogate and validate the associations identified between the human microbiome and disease.

The gut microbiotas of many animals are reservoirs of ABRs, and it is a matter of how to choose an appropriate experimental system to observe and measure the processes that determine the spread of resistance genes in populations, considering different units of selection by the antibiotic. In this sense, arranged hierarchically we can study (i) resistance genes, (ii) elements of horizontal transfer carriers of these genes (integrons, transposons, and/or plasmids), and (iii) bacterial lineages and bacterial communities with horizontal transfer exchange. Our chosen model system was the German cockroach Blatella germanica, which has been suggested as a useful animal system in previous work (30, 31).

WHY CHOOSE B. GERMANICA AS AN EXPERIMENTAL MODEL SYSTEM?

B. germanica is a cosmopolitan species of cockroach (32). Cockroaches are omnivorous insects that harbor a rich and complex gut microbiota, similar in some characteristics to human gut microbiota (33, 34), and may contain bacteria with many ABRs that can be a reservoir to be transferred to humans (32). They are found mostly in buildings and homes, sheltered in small, damp places such as bathrooms or kitchens, since the best conditions for them are high humidity (60%) and warm temperatures (between 26 and 28°C) (35). In addition, this and other cockroach species have been detected in areas like hospital rooms and in intensive care areas, sometimes acting as pathogenic vectors (34, 36). They are responsible for generating allergic reactions due to their feces, and their behavior is regulated by pheromones (35). It has been found that many of the bacteria present in the human digestive tract are also present in that of cockroaches, where they coexist with many pathogens and opportunists that can cause disease in humans (37). Therefore, B. germanica is considered a natural reservoir of human pathogens, and its characterization may be helpful for biomedical research, given that many isolates identified from its external body and internal gut show antibiotic multiresistance (32, 38).

Cockroaches are insects that maintain two types of symbiotic systems. One is the intracellular symbiont Blattabacterium cuenoti, a Gram-negative bacterium belonging to the phylum Bacteroidetes, located in bacteriocytes (special host cells) in the fat body; and the other group, the gut microbiota proper, is formed mostly by ectosymbionts located in particular areas of the intestinal tract (39). The endosymbiont is key in recycling nitrogen and contains urease, an enzyme absent in mammals and many other animals that is capable of degrading urea (40). On the other hand, the gut microbiota of cockroaches also plays an important role in host metabolism because it helps to process the complex diet of an omnivorous insect like B. germanica (39, 41). It is still unknown how cockroaches obtain their microbiota in each generation, but the presumption is that it is via trophallaxis (mouth-to-mouth or anus-to-mouth feeding), coprophagy (consumption of feces), or body/ootheca licking or from the environment. A relevant result obtained by our group is that the endosymbiont Blattabacterium was the only bacterium found in the ootheca, which clearly indicates that there is no vertical transmission and thus there must be horizontal acquisition of the intestinal microbiota in each generation by any of the previous proposed mechanisms (39, 41).

The ontogenetic development of the microbial community also remains unknown. The gut contents of nymphs are similar but are different from that of adult cockroaches. Bacteroidetes (60%), Firmicutes (30%), and Proteobacteria (10%) were the phyla most commonly found in all the stages except in embryos and in nymphal stage 1 (n1), where Blattabacterium was the only (embryo) or the most present (n1) bacterium (39).

Some of the interesting characteristics of B. germanica in proposing it as an experimental animal model are its relatively short life cycle and the ease with which it is maintained in the laboratory. Although variable, the B. germanica life cycle from eggs lasts ∼100 days. The nymphs go through six stages before becoming adults, which occurs in ∼36 days, with a life expectancy of adults of 9 to 10 months. The population under study belong to an original population maintained in the lab for 30 years and kindly provided by Xavier Belles from the Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (Barcelona, Spain) in 2013, being reared since then in the chambers of the Institut Cavanilles (València, Spain) in lunch boxes with aeration at 26°C, 70% humidity, and a photoperiod of 12-h light/12-h darkness. The normal diet in lab-reared animals is dog food (Teklad 2021C; Harlan UK Ltd, Bicester), which provides the animal with a complete set of nutrients.

The digestive tract of the insect is divided into three parts: foregut, midgut, and hindgut. There are few or no microbiota at all in either the foregut or the midgut. Thus, the hindgut concentrates the vast majority of bacterial species that constitute the intestinal bacterial microbiota of this insect (33, 34, 39). Another important part of the insect is the fat body, which contains three types of cells: adipocytes, uricocytes, and bacteriocytes, the special eukaryotic cells harboring Blattabacterium, which, as already stated, plays an essential role in the metabolism of cockroaches, allowing them to recycle the excess of nitrogen stored in the uricocytes and used as a nitrogen source (40). This means that the cockroach is capable of generating a reservoir and of recycling nitrogen by means of a new metabolic pathway in collaboration with the endosymbiont (40, 42). In this way, the insect-endosymbiont relationship can convert an excretory product into a valuable metabolic reserve (43). The relationship between both partners (B. germanica and Blattabacterium) is mutualistic, meaning that both host and symbionts need each other to survive. Thus, any experimental setting with B. germanica needs to keep Blattabacterium alive, or somehow be able to play its role.

Before starting with the experimental epidemiology itself, two major types of questions should be addressed. The first is related to the composition, function, and transmission of gut microbiota in B. germanica, and more precisely the role played in host physiology and how symbionts, particularly the gut microbiota, are transmitted and/or acquired throughout generations, and how different diets affect gut microbiota and host fitness. The second type of questions are related to the presence of ABRs in natural and lab-reared populations and how the fitness of B. germanica is affected when it is treated with different antibiotics.

Large differences in bacterial community composition have been observed among individuals of the same cockroach species that are associated with the accumulation of different microbial products that influence the health status of the host (34). Similar variations among individuals in bacterial communities from the same habitat have also been reported for mammals, including humans (44) and pigs (45), and are believed to have appeared from the random acquisition of microorganisms in diet and the environment (45). Apart from these two factors, host phylogeny is also considered as an important issue that affects the composition and abundance of the gut communities of mammals (46). The impact of host phylogeny on the composition of gut microbiota has also been demonstrated in cockroaches. Thus, cockroaches share a high presence of Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria with their sister group wood-feeding termites. In addition, the gut microbiota of these animals has many elements in common with the gut communities of more distantly related animals, such as cow rumen and the intestinal tracts of mice and humans (33). This suggests the existence of common environmental factors that determine the composition of resident microbiota in the intestinal habitat. In humans, bacterial populations in the gut have an impact on host physiological functions through their metabolic activity, because they are performing essential metabolic functions and produce small bioactive molecules that interact with the host (47–49). Similarly, in insects, several works have demonstrated the diverse roles played by gut microbiota in host physiology leading, in extreme cases where some groups are absent, to host mortality (50–53). In the case of our model, B. germanica, preliminary work has shown changes in bacterial abundance and composition across insect development (37), although no further information regarding the associated metabolic roles of the involved bacteria is yet available (work in progress).

As already stated, Blattabacterium is located in the bacteriocytes, specialized cells 20 μm in diameter, which originated phylogenetically from intestinal epithelium cells infected by a free-living ancestor via food intake (54). Bacteriocytes, in turn, are internalized in the abdominal fat body of cockroaches (55). They are also localized in the follicular epithelium of the ovarioles, the structures that group ovaries. Transmission is vertical, i.e., maternal by transovarial infection (54). The transfer begins with the invasion of ovarioles by bacteriocytes that are attached to the oocytes. Blattabacterium is then released from the bacteriocyte and migrates through its own tunic and follicular epithelium into the space between the latter and the oocyte (56). Then the bacteria are “endocytosed” by the pseudopodia of the egg membrane, and are internalized. Finally, they migrate to the center of the egg (57).

The dependency of microbiota on diet is a matter that has been widely observed, and in cockroaches the subject has been studied first by observing morphological and developmental aspects (58), and later by studying the effect of synthetic diets and how they affect the insect and the microbiota (34, 59, 60). In previous studies in our group on the dynamics of microbiota across time, the bacterial load was determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and the bacterial composition of gut microbiota was established by pyrosequencing the 16S rRNA gene gene in the egg, five nymphal stages, and adult (38). It was observed that bacterial load increased by 2 orders of magnitude from n1 to n2, coinciding with the incorporation of the majority of bacterial taxa. As in humans, there is an ecological succession from nymphs to adults, and important changes in the bacterial composition between the adult and the nymphs have been found. The effect of diet on the composition and evolution of gut microbiota in this animal model has also been studied in previous work (39, 41). To assess the effect of protein content in the females of B. germanica, three types of diet—high protein content (50%), no protein content (0%), and control diet or dog food (24% protein content)—at two different adult stages (8 and 13 days) were used. It was found that the variations in the bacterial community were due mainly to changes in the protein content of the diet and also the time analyzed (39). Clustering analyses proved that samples tended to be grouped by diet, indicating that protein content is a very important element in modulating the structure of the gut microbial ecosystem in cockroaches. In the same work, the gut microbiota of wild adult cockroaches was analyzed. Remarkably, the highest diversity was found in the wild animals, and the composition was more similar to that of the cockroaches fed with no protein content and for 13 days, indicating the low protein content that cockroaches must cope with in natural conditions.

EFFECT OF ANTIBIOTIC ON SYMBIOTIC SYSTEMS: MICROBIOTA AND FITNESS CHANGES DUE TO ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT IN B. GERMANICA

As stated above, before starting experimental epidemiology with B. germanica, it is necessary (i) to have knowledge about the effect of antibiotics in B. germanica symbionts (either endosymbionts or gut microbiota) and in the fitness of the host and (ii) to explore the presence of ABRs in the microbiota of wild B. germanica by metagenome analyses.

Regarding the first point, several preliminary experiments were carried out. In the first series, two antibiotics with two different intensities of antibiotic exposure were employed: chlortetracycline (1 and 10 mg/ml) and rifampin (2 and 20 mg/ml). Several parameters were then measured: (i) fitness (weight of the individuals at established time points, time of development, and fecundity measured as number of females with ootheca at established time points) and (ii) qualitative PCR and qPCR determination assays, with primers targeting the gene ureC specific to Blattabacterium, as a measure of the amount of genomes and, thus, of endosymbionts. For the qPCR assay, genomic DNA samples prepared from previously dissected fat bodies were measured and unified to a concentration of 5 ng/μl, and 3 μl of each sample mixed with 17 μl of a PCR mixture using SYBR green in an AriaMx real-time PCR system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The sequences of the primers were UC1F, 5′-GTCCAGCAACTGGAACTATAGCCA-3′, and UC1R, 5′-GTCCAGCAACTGGAACTATAGCCA-3′, giving an amplification fragment of 166 nucleotides.

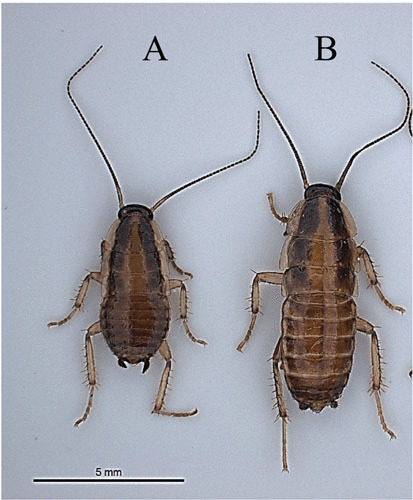

With antibiotic treatments there was observed, in general, a statistically significant decrease in the three fitness parameters measured: weight, developmental time, and fecundity. Significant differences in weight after 25 days of treatment were obtained for both antibiotics and treatments (see Fig. 1 to see the general observation of a decrease in size and weight). The developmental time, measured as the proportion of individuals that reached the adult stage, showed no significant differences between chlortetracycline and the control at low exposures. However, significant differences were observed at high doses. It should be noted that this result is in agreement with recent findings of the bactericidal effect of chlortetracycline on bacteria harboring low numbers of ribosomes, as in the case of Blattabacterium (61). Under treatment with rifampicin both concentrations clearly affected development, which was more noticeable at the highest concentration. The appearance of oothecas (i.e., fecundity) was also clearly affected as a result of antibiotic treatments. Both treatments with the two exposures differed from the corresponding control. After the treatments, fewer females had oothecas, and they were smaller and took longer to appear.

FIGURE 1.

Loss of weight and size in B. germanica due to antibiotic treatment after 25 days. (A) Insect treated with chlortetracycline 1 mg/ml. (B) Insect not treated with antibiotics.

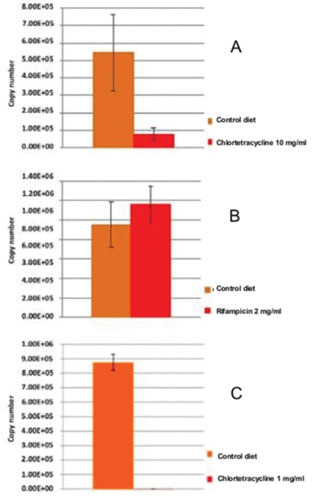

Quantitative analyses were carried out using the same gene as the target and real-time qPCR with SYBR green, using four control samples and four individuals treated, each with three replicates. The results of the abundance of endosymbionts in parental chlortetracycline-treated samples revealed a decrease in the amount of the ureC gene compared to the control cockroaches. The ones treated with rifampicin showed no differences in the amount, with no decrease in the endosymbionts. The qPCR in the progeny (F1) of B. germanica treated with chlortetracycline revealed a marked reduction in the amount of DNA compared to control cockroaches, by nearly 6 orders of magnitude (Fig. 2). In addition, the appearance of individuals in this F1 was different, with a lighter color and smaller size compared to the control. The average weight per individual was also lower compared to the control. Rifampicin-treated samples could not be analyzed due to the death of all the samples of the progeny with both antibiotic doses, which shows the strong effect of this antibiotic in the insect.

FIGURE 2.

Copy number of gene ureC of Blattabacterium genome in B. germanica treated with chlortetracycline 10 mg/ml (A) and rifampicin 2 mg/ml (B). There is a strong reduction in the number of endosymbionts with chlortetracycline, whereas with rifampin at low dose no effect is observed. (C) Copy number of gene ureC of Blattabacterium genome in F1 progeny of B. germanica treated with chlortetracycline 1 mg/ml.

In a second series of experiments, additional trials were carried out with rifampicin with a dose 10 times below the lowest dose previously employed, using a population that was fed dog food until the adults appeared. This population was divided in two; the control was fed dog food, and rifampicin (0.2 mg/ml) was added to the water supply of the other group. The gut and fat body of three individuals at different time points (10, 20, and 30 days) were analyzed to monitor two parameters: (i) the amount of Blattabacterium by qPCR, using the ureC gene as target DNA; and (ii) the changes in the bacterial composition by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Once the new individuals appeared, the antibiotic-treated population was subdivided into another two groups; one continued with the antibiotic supply and the other returned to its dog food diet for 10 days. The qPCR analyses did not show any significant differences in the quantification of the endosymbiont of the antibiotic-treated individuals versus dog food diet recipients in the original two populations. However, the two populations derived from the antibiotic-treated one showed a reduction in the Blattabacterium population of 5 log units in all of the samples, compared to the amounts of the original antibiotic-treated and dog food-receiving populations.

Changes in the microbiota composition from these antibiotic treatments were analyzed using the Illumina (San Diego, CA) MiSeq platform to amplify and sequence the 16S rRNA gene (amplicons). These regions are frequently used for phylogenetic classifications in microbial populations (62). The analysis of the sequences was accomplished by using the MiSeq system in the Illumina analysis cloud environment BaseSpace (www.basespace.illumina.com). The taxonomic information for the 16S rDNA sequences was obtained by comparison against the Ribosomal Database Project-II (RDP). For species identification, the taxonomic assignment was also performed with RDP and a bootstrap threshold of 60%. Additional Web-based matching against type strain sequences was conducted with RDP SeqMatch (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/seqmatch/seqmatch_intro.jsp). Abundances were Hellinger transformed and a principal component analysis based on the covariance matrix of transformed abundances was performed. Subsequently, the QIIME application was used for analysis (63). The FastQC application was used as a quality control for the sequences (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). With the 16S Metagenomics application, the taxonomic classification was determined. This application performs a taxonomic classification using the Greengenes Database (64).

The results obtained in the original two populations showed that the microbiota was greatly affected in the antibiotic-treated samples compared to the control ones. In the new population formed with the newborns of the antibiotic-treated populations, but with no antibiotic in the diet, the microbiota recovered almost to the same composition of the samples that were fed the control diet. That is to say, the microbiota recovered simply by suspending the treatment of rifampicin, while if the treatment continued, it produced a drastic reduction in the composition of the microbiota. In this case, the treatment with rifampicin had a rapid effect on the microbiota composition in one generation, while the endosymbiont population (qPCR experiments) seemed to be affected in the next generation, despite the suppression of the treatment. The morphological features of the population (size, weight, and developmental time of insects) were affected by the antibiotic, with a delay in all these parameters (unpublished data).

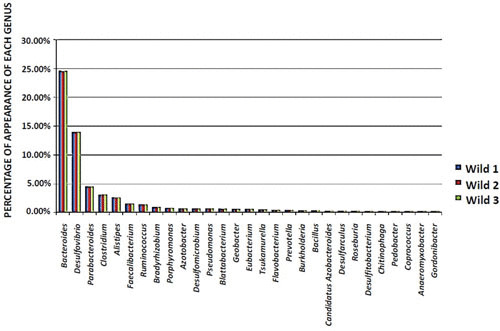

In terms of the second goal (to explore the presence of ABRs in the microbiota of wild B. germanica by metagenome analyses), metagenomics analyses of three wild animals were also performed to determine their bacterial composition and abundances (Fig. 3) and also to identify ABRs and their possible taxon origin (Table 1). In these analyses, we applied a bioinformatics pipeline from raw DNA sequencing data that included demultiplexing and quality filtering, OTU picking, taxonomic assignment, phylogenetic reconstruction, diversity analyses, and visualizations. The search for resistance genes in the predicted open reading frames was performed by a blastp analysis against the Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database (http://ardb.cbcb.umd.edu/), through local alignments for the location of gene sequences belonging to resistant genes.

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of genus abundance (>1.5%) from three wild B. germanica females.

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic resistance genes found in the metagenomic analyses performed on three wild B. germanica females

| Resistance gene | Description | Resistance profile |

|---|---|---|

| acra, acrb | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Aminoglycoside, glycylcycline, β-lactam, macrolide, acriflavine |

| adeb | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Chloramphenicol, aminoglycoside |

| amrb | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Aminoglycoside, macrolide, acriflavine |

| aph33ib, aph6id | Aminoglycoside O-phosphotransferase | Streptomycin |

| arna | Bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of UDP-glucuronic acid (UDP-GlcUA) to UDP-4-keto-arabinose (UDP-Ara4O) | Polymyxin |

| baca | Undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase | Bacitracin |

| bcra | ABC transporter system, bacitracin efflux pump | Bacitracin |

| bl1_ampc, bl1_sm, bl1_mox | Class C β-lactamase | Cephalosporin |

| bl2b_tem | Class A β-lactamase | Cephalosporin, penicillin |

| bl2b_tem1 | Class A β-lactamase | Cephalosporin ii, penicillin, Cephalosporin i |

| cata2, mdtl | Group A chloramphenicol acetyltransferase | Chloramphenicol |

| ceob | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system | Chloramphenicol |

| ermf | rRNA adenine N-6-methyltransferase | Streptogramin B, lincosamide, macrolide |

| fosx | Glutathione transferase, metalloglutathione transferase | Fosfomycin |

| ksga | Dimethylates two adjacent adenosines in the 16S rRNA in the 30S particle | Kasugamycin |

| lsa | ABC efflux family that is resistant to macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramin B | Streptogramin B, lincosamide, macrolide |

| macb | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Macrolide |

| mdtf | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Doxorubicin, erythromycin |

| mdth, mdtg | Major facilitator superfamily transporter. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Deoxycholate, fosfomycin |

| mdtk | Major facilitator superfamily transporter. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Enoxacin, norfloxacin |

| mexi, mexw, mexd, oprj | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Glycylcycline, fluoroquinolone, erythromycin, roxithromycin |

| mexy | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Aminoglycoside, glycylcycline |

| pbp1b, pbp2 | Penicillin-insensitive transglycosylase N-terminal domain | Penicillin |

| qnrb | Pentapeptide repeat family | Fluoroquinolone |

| rosa, rosb | Efflux pump/potassium antiporter system. RosA: major facilitator superfamily transporter; RosB: potassium antiporter | Fosmidomycin |

| smeb, smed, smee | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Fluoroquinolone |

| sul2 | Sulfonamide-resistant dihydropteroate synthase | Sulfonamide |

| tet32, tetm | Ribosomal protection protein | Tetracycline |

| tet37 | Flavoproteins. Only one such protein found in oral metagenome | Tetracycline |

| tolc | Resistance-nodulation-cell division transporter system. Multidrug resistance efflux pump | Aminoglycoside, glycylcycline, β-lactam, macrolide, acriflavin |

| vand, vanrd | VanD-type vancomycin resistance operon genes | Vancomycin, teicoplanin |

| vanra, vansa, vanrc | VanA-type vancomycin resistance operon genes | Vancomycin, teicoplanin |

| vatb | Virginiamycin A acetyltransferase | Streptogramin A |

The results of all these experiments were of great interest, helping us to observe what could be expected in the experimental model with the different antibiotics and the dose to be employed.

HUMANIZING THE BACTERIAL MICROBIOTA OF B. GERMANICA

A fundamental question that we had in mind was the following: Is it possible to humanize the bacterial microbiota of cockroaches? By that, we mean to introduce human bacterial species harboring ABRs into the gut microbiota of B. germanica. In a first approach, the idea was to use bacteria naturally occurring in cockroaches, so the system would be as natural as possible. A search for antibiotic-resistant bacterial isolates was carried out and these were analyzed to look for the presence of plasmids that could be responsible for resistance. Finally, a system to analyze the population of the endosymbiont was also required, to evaluate the effect of different antibiotics on Blattabacterium survival. In summary, for this specific project we had to look for natural cultured antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains in natural and lab-reared populations, and locate which of the resistance genes observed were in plasmids. The results obtained allowed the identification of bacterial species also present in humans and harboring antibiotic resistance; thus, this idea of “humanizing” the gut microbiota was no longer necessary because we can use bacteria present in both systems.

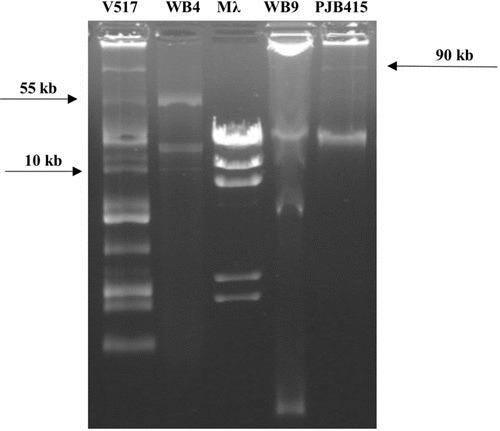

Previous work on the analysis of cultivable microbiota in the hindgut of different species of cockroaches used several culture media and conditions (rich and specific media, incubation temperature of 37°C). All previous research was addressed to find human-pathogenic bacteria and measure the risk of this insect as a vector for the spread of disease (65, 66). In our case, screening of the gut microbiota using culturing methods was performed as previously described (65, 67). Some bacterial strains showing ABRs in wild and in lab-reared animals were obtained, with some isolates presenting multiresistance (Table 2). The idea was to increase the chance of finding target antibiotic-resistant organisms of clinical interest by means of isolation in general media with different antibiotics, to look for the presence of plasmids that were resistant to one or several antibiotics, and finally to tag the plasmid with green fluorescent protein (GFP) to monitor its possible transfer between insects harboring it. After checking several media, the best results were obtained using brain heart infusion (Pronadisa, Madrid, Spain), a general medium rich in nutrients and suitable for the growth and development of various bacterial groups including many types of pathogens (68). Two more media, specifically for enterococci (Enterococcus agar; Difco, Le Pont de Claix, France) and enterobacteria (MacConkey agar; bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), were also employed to increase the chance of finding antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The incubation temperature was chosen to be as similar as possible to cockroaches’ natural conditions (28°C) instead of the conditions found inside the human body (37°C). The colonies isolated were analyzed for antibiotic resistance with four antibiotics at the standard concentrations of use in microbiology (gentamicin, 20 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; vancomycin, 10 μg/ml; and ampicillin, 100 μg/ml) and identified by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene (using Sanger platform) and blastn searches using the 16S rRNA sequences database. Bacterial isolates resistant to all the antibiotics assayed were found after analyzing a few individuals (Table 2). From several isolates showing resistance to more than one antibiotic, plasmid extractions were performed and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Different plasmids were found, ranging in size from 1 to >50 kb (Fig. 4), but the restriction analyses performed did not show similarities to plasmids previously analyzed from the same species (69–71). Consequently, due to the difficulties found in using the plasmids observed because of the lack of sequence information, we used previously analyzed plasmids pRE25 (72) and pIP501 (73) showing resistance to different antibiotics. pRE25 is a conjugative and mobilizing multiresistance plasmid of 50 kb from Enterococcus faecalis strain RE25 (74). Plasmid pRE25 encodes resistance to 12 antimicrobials belonging to five structural classes. These include aminoglycosides, lincosamides, macrolides, chloramphenicol, and streptothricin. These genes are closely related to the ABRs already detected in human pathogens, including kanamycin, neomycin, streptomycin, erythromycin, roxithromycin, tylosin, and chloramphenicol, among others. Similar resistance determinants have been found in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, bacteria isolated from animal environments and other sources, which reveals the widespread dissemination of antibiotic resistance traits among Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This important genetic exchange may lead to a dramatic limitation of the potential of antibiotics to combat human infection (75). Accordingly, pRE25 may contribute to the further spread of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms via food in the human community.

TABLE 2.

Species identified and the antibiotics to which they show resistance after isolation of colonies belonging to the gut microbiota of 12 wild and 5 lab-reared B. germanica individuals

| Isolate | Antibiotics and concentrations used | Gram reaction | Identification (16S rRNA gene) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanamycin (50 μg/ml) | Vancomycin (10 μg/ml) | Ampicillin 100 μg/ml | Gentamicin (20 μg/ml) | |||

| Wild1 | S | R | R | S | – | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| Wild2 | S | R | R | S | – | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| Wild3 | R | R | R | R | – | Pseudomonas nitroreducens |

| Wild4 | S | R | R | S | – | Pseudomonas nitroreducens |

| Wild5 | S | R | R | S | – | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| Wild6 | S | S | S | S | + | Enterococcus pallens |

| Wild7 | S | R | R | S | – | Pseudomonas nitroreducens |

| Wild8 | S | R | R | S | – | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| Wild9 | R | R | S | R | + | Enterococcus malodoratus |

| Wild10 | R | R | R | R | + | Enterococcus avium |

| Wild11 | R | R | S | R | + | Enterococcus avium/Enterococcus gilvus |

| Wild12 | R | R | S | R | + | Enterococcus malodoratus |

| Lab1 | R | R | R | R | – | Stenotrophomonas pavanii |

| Lab2 | R | R | R | S | + | Enterococcus durans |

| Lab3 | R | R | R | R | + | Staphylococcus hominis |

| Lab4 | S | S | R | S | – | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| Lab5 | R | R | R | R | + | Enterococcus canis |

R: antibiotic resistant; S: antibiotic sensible

FIGURE 4.

Plasmid profiles of some of the isolates from the hindgut. V517 and PJB415, marker plasmids; Mλ, marker λ HindIII; V517, Escherichia coli strain with plasmids used as markers; WB4, Pseudomonas nitroreducens; WB9, K. oxytoca; PJB415, plasmid marker 90 kb.

Plasmid pIP501 (30 kbp) is a broad-host-range, conjugative plasmid originally isolated from a clinical strain of Streptococcus agalactiae in 1975 (76). When compared to relevant sequences of pRE25, an overall nucleotide identity of 98% was observed. pRE25 can be transferred by conjugation to E. faecalis, Listeria innocua, and Lactococcus lactis by means of a transfer region that is similar to that of pIP501, and in addition, a 30.5-kb segment is almost identical to this plasmid. At the time being the protocol for measuring antibiotic resistance transfer is based on the use of these plasmids, hosted by Klebsiella oxytoca and Enterococcus avium, isolated from the Blatella gut.

Two gfp genes, one placed in the broad-range-host vector pSEVA237M harboring a promoterless monomeric superfolder gfp gene (77), and another GFP with the strong constitutive promoter J23104 cloned in the pUC57-Amp plasmid (78), were employed. The following step was to introduce these gfp genes into the plasmids pRE25 and pIP501 and, once the emission of green fluorescence had been confirmed, transform these labeled plasmids into natural bacterial isolates that did not show resistance to the antibiotic under study (K. oxytoca and Enterococcus pallens; Table 2). These bacteria were provided to a population of cockroaches with a water supply that had been modified with the same antibiotic to introduce selective pressure to increase the resistant bacteria harboring the markers, mimicking a hospital population. Another population fed without antibiotic, as a normal population, was mixed with the antibiotic-treated cockroaches.

EXPERIMENTAL EPIDEMIOLOGY DESIGN: A PROPOSAL TO MEASURE THE ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE TRANSMISSION RATE

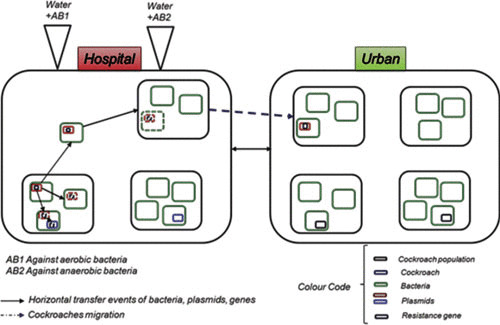

The two populations grew in two different hospital and community environments (Fig. 5), with the possibility of migrating from one population to another being simulated, which means the study was metapopulational. The first consisted of individuals previously colonized by bacteria resistant to one antibiotic, whereas the second consisted of individuals with possible natural resistance. The hospital environment was supplied with water containing antibiotic. Each blue box corresponds to a roach with its particular microbiota. The green boxes are bacteria that, in turn, can harbor different plasmids (red and dark-blue boxes). The arrows mean trans-hierarchical horizontal transfer events of bacteria and plasmids, represented by the discontinuous boxes. Then migration was allowed to facilitate the transmission of resistant bacteria to the untreated population.

FIGURE 5.

Experimental model of transmission of information about antibiotic resistance using an experimental model system with the aim of simulating the evolution of antibiotic (AB) resistance genes in human communities mimicking hospital and urban environments.

The methodology proposed intends to establish a reproducible model of the transmission of antibiotic resistance using an animal model system to understand the dynamics of ABRs in human populations. This type of complex scenario, where bacteria-resistant populations and their genetic platforms containing ABRs move because they are selected, and evolve because of their promiscuous migration, establishes the precondition to visualize ABRs not only as a biological function but also as the processing of an information flow.

According to the current situation in this field of research, we aim to combine new developments in molecular microbiology, metagenomics, bacterial population biology and metapopulation, evolutionary biology, and computational biology and systems. The project has been divided into five levels.

Theory: the issue of trans-hierarchical relations between evolutionary objects. If a resistance gene is in a specific gene vector in a bacterial population and this is housed in a microbiota of a particular host and if genes, vectors, populations, and guests are independently subjected to selective processes, could we predict the spread of resistance, given the dynamics of these biological objects and selection conditions?

Computational: we aim to test the hypothesis that transmission processes can be defined computationally when resistance genes and genetic vectors can be formalized (see below). If this is confirmed, a computer model can be made based on the processes under study to formulate new hypotheses to return the focus of computing to biology through new experiments. In addition to the description and resolution of this problem for the first time, modeling techniques based on membrane computing can be applied.

Experimental: a model system for experimental epidemiology with B. germanica populations in order to measure where they will represent both hierarchical levels of study, the population conditions and selection, to help test the model.

Clinical: the model of B. germanica also constitutes a model of evolution of antibiotic resistance in hospitals and in the community and will be compared with epidemiological field experiences in these areas.

Intervention: the targets will be detected for interventions to prevent the spread of resistant organisms.

COMPUTER MODELING OF THE TRANSMISSION OF ABRs

In parallel with the experimental epidemiology on ABRs, we developed a computer model (31) that captures the transmission of genetic information across different levels of the biological hierarchy, from metapopulations of a given species (ecology) to the genetic units of bacteria harboring ABRs in the corresponding animal microbiotas (79). The model and the associated software, entitled ARES (Antibiotic Resistance Evolution Simulator), aims to simulate and measure the antibiotic resistance transmission rate under different population scenarios and exposure regimes to antibiotics. ARES simulates P-system model scenarios with five types of nested computing membranes to emulate the following nested compartments: (i) a peripheral ecosystem, (ii) different local environments, (iii) a reservoir of supplies, (iv) an animal host, and (v) host-associated microbiota. The computational objects emulating molecular entities, such as plasmids, ABRs, antimicrobials, and/or other substances, can be properly introduced in the ARES framework and may interact and evolve together with the membranes, based on a set of preestablished rules and specifications. ARES has been implemented as an online server and offers additional tools for storage and model editing and downstream analysis (31). ARES can be accessed at http://gydb.org/ares. The experimental epidemiology design with B. germanica offers empirical values for the transmission rates of ABRs on the above-mentioned hierarchical levels, which will also be simulated by ARES under a similar design (i.e., two populations of animals, with a given migration rate of animals, different exposure to antibiotics, etc.). Accordingly, this will validate ARES as a tool to apply it to other regimes. In fact, ARES offers the chance to model predictive multilevel scenarios of antibiotic resistance evolution that can be interrogated, edited, and resimulated if necessary, with different parameters, until a correct model description of the process in the real world is convincingly approached.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

This chapter presents a research program to experimentally (with the cockroach B. germanica) and computationally (by means of P-system membrane computing) evaluate the transferability of ABRs across different biological elements (microbiota, clones, and plasmids) and establish a model of experimental epidemiology of antibiotic resistance. Prolonged use of antibiotics or the intake of processed food increases the proportion of resistant bacteria (79), implying that the study of the emergence, persistence, and transfer mode of antibiotic resistance between hosts is necessary for the design of new antibiotics, health measures, vaccination campaigns, and epidemiological risk prediction (8–10, 80). B. germanica is a model to investigate the evolution of resistance because it has a very rich intestinal microbiota with human-like complexity (40), capable of incorporating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It can be grown in the laboratory and has a short generation time (4 months), enabling both the size and nature of the bacterial inoculum, as well as the dose of the various antibiotics, to be manipulated.

The outcomes of this project will be important to estimate the critical parameters that feed ARES, a membrane computational model to investigate the transmission of antibiotic resistance across hierarchical levels. The results obtained by the simulator will, in turn, serve to refine the experiments. B. germanica also constitutes a model of evolution of antibiotic resistance in hospitals and in the community and will be compared with epidemiological field experiences in these areas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants to A.M. and A.L. from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, co-financed by ERDF funds (projects SAF2012-31187, SAF2013-49788-EXP, SAF2015-65878-R, and BFU2015-64322-C2-1-R), Carlos III Institute of Health (projects PIE14/00045 and AC15/00022), and Valencian Regional Government (project PrometeoII/2014/065). Plasmids pRE25 and pIP501 were kindly provided by T. Coque and F. Baquero (University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain).

Contributor Information

Pablo Llop, Foundation for the Promotion of Sanitary and Biomedical Research in the Valencian Region (FISABIO), València, Spain.

Amparo Latorre, Foundation for the Promotion of Sanitary and Biomedical Research in the Valencian Region (FISABIO), València, Spain; Integrative Systems Biology Institute, Universitat de València, València, Spain; Network Research Center for Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Andrés Moya, Foundation for the Promotion of Sanitary and Biomedical Research in the Valencian Region (FISABIO), València, Spain; Integrative Systems Biology Institute, Universitat de València, València, Spain; Network Research Center for Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Fernando Baquero, Hospital Ramón y Cajal (IRYCIS), Madrid, Spain.

Emilio Bouza, Hospital Ramón y Cajal (IRYCIS), Madrid, Spain.

J.A. Gutiérrez-Fuentes, Complutensis University, Madrid, Spain

Teresa M. Coque, Hospital Ramón y Cajal (IRYCIS), Madrid, Spain

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/. Accessed February 20th, 2017.

- 2.Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 2013. G8 Science Ministers Statement. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/g8-science-ministers-statement. Accessed February 20th, 2017.

- 3.World Health Organization. 2016. Antimicrobial resistance. Fact sheet No. 194. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/. Accessed February 20th, 2017.

- 4.Carlet J, Jarlier V, Harbarth S, Voss A, Goossens H, Pittet D, Participants of the 3rd World Healthcare-Associated Infections Forum. 2012. Ready for a world without antibiotics? The Pensières Antibiotic Resistance Call to Action. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 1:11. 10.1186/2047-2994-1-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi AKM, Wertheim HFL, Sumpradit N, Vlieghe E, Hara GL, Gould IM, Goossens H, Greko C, So AD, Bigdeli M, Tomson G, Woodhouse W, Ombaka E, Peralta AQ, Qamar FN, Mir F, Kariuki S, Bhutta ZA, Coates A, Bergstrom R, Wright GD, Brown ED, Cars O. 2013. Antibiotic resistance—the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis 13:1057–1098. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarlier V, Carlet J, McGowan J, Goossens H, Voss A, Harbarth S, Pittet D, Participants of the 3rd World Healthcare-Associated Infections Forum. 2012. Priority actions to fight antibiotic resistance: results of an international meeting. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 1:17. 10.1186/2047-2994-1-17. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rolain JM, Parola P, Cornaglia G. 2010. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM-1): towards a new pandemia? Clin Microbiol Infect 16:1699–1701. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03385.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baquero F. 2004. From pieces to patterns: evolutionary engineering in bacterial pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:510–518. 10.1038/nrmicro909. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baquero F, Coque TM, de la Cruz F. 2011. Ecology and evolution as targets: the need for novel eco-evo drugs and strategies to fight antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3649–3660. 10.1128/AAC.00013-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baquero F, Tedim AP, Coque TM. 2013. Antibiotic resistance shaping multi-level population biology of bacteria. Front Microbiol 4:15. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00015. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. 2010. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev 90:859–904. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA. 2007. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 449:811–818. 10.1038/nature06245. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM, Bertalan M, Borruel N, Casellas F, Fernandez L, Gautier L, Hansen T, Hattori M, Hayashi T, Kleerebezem M, Kurokawa K, Leclerc M, Levenez F, Manichanh C, Nielsen HB, Nielsen T, Pons N, Poulain J, Qin J, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Tims S, Torrents D, Ugarte E, Zoetendal EG, Wang J, Guarner F, Pedersen O, de Vos WM, Brunak S, Doré J; MetaHIT Consortium, Antolín M, Artiguenave F, Blottiere HM, Almeida M, Brechot C, Cara C, Chervaux C, Cultrone A, Delorme C, Denariaz G, Dervyn R, Foerstner KU, Friss C, van de Guchte M, Guedon E, Haimet F, Huber W, van Hylckama-Vlieg J, Jamet A, Juste C, Kaci G, Knol J, Lakhdari O, Layec S, Le Roux K, Maguin E, Mérieux A, Melo Minardi R, M’rini C, Muller J, Oozeer R, Parkhill J, Renault P, Rescigno M, Sanchez N, Sunagawa S, Torrejon A, Turner K, Vandemeulebrouck G, Varela E, Winogradsky Y, Zeller G, Weissenbach J, Ehrlich SD, Bork P. 2011. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 473:174–180. 10.1038/nature09944. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salyers AA, Gupta A, Wang Y. 2004. Human intestinal bacteria as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes. Trends Microbiol 12:412–416. 10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.004. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francino MP. 2014. Early development of the gut microbiota and immune health. Pathogens 3:769–790. 10.3390/pathogens3030769. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francino MP. 2016. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol 6:1543. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore AM, Ahmadi S, Patel S, Gibson MK, Wang B, Ndao MI, Deych E, Shannon W, Tarr PI, Warner BB, Dantas G. 2015. Gut resistome development in healthy twin pairs in the first year of life. Microbiome 3:27. 10.1186/s40168-015-0090-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu N, Hu Y, Zhu L, Yang X, Yin Y, Lei F, Zhu Y, Du Q, Wang X, Meng Z, Zhu B. 2014. DNA microarray analysis reveals that antibiotic resistance-gene diversity in human gut microbiota is age related. Sci Rep 4:4302. 10.1038/srep04302. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Wintersdorff CJ, Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Oude Lashof AM, Hoebe CJ, Savelkoul PH, Wolffs PF. 2014. High rates of antimicrobial drug resistance gene acquisition after international travel, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 20:649–657. 10.3201/eid2004.131718. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y, Yang X, Lu N, Zhu B. 2014. The abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in human guts has correlation to the consumption of antibiotics in animal. Gut Microbes 5:245–249. 10.4161/gmic.27916. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ebert D, Lipsitch M, Mangin KL. 2000. The effect of parasites on host population density and extinction: experimental epidemiology with Daphnia and six microparasites. Am Nat 156:459–477. 10.1086/303404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flexner S. 1922. Experimental epidemiology. J Exp Med 36:9–14. 10.1084/jem.36.1.9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenwood M, Hill AB, Topley WWC, Wilson J. 1936. Experimental Epidemiology. Medical Research Council Special Report No. 209. Medical Research Council, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 24.May RM, Anderson RM. 1979. Population biology of infectious diseases: part II. Nature 280:455–461. 10.1038/280455a0. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster LT. 1932. Experimental epidemiology. Medicine 11:321–344. 10.1097/00005792-193209000-00002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kostic AD, Howitt MR, Garrett WS. 2013. Exploring host-microbiota interactions in animal models and humans. Genes Dev 27:701–718. 10.1101/gad.212522.112. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharon G, Segal D, Ringo JM, Hefetz A, Zilber-Rosenberg I, Rosenberg E. 2010. Commensal bacteria play a role in mating preference of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:20051–20056. 10.1073/pnas.1009906107. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methé BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, Li H, Alekseyenko AV, Blaser MJ. 2012. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature 488:621–626. 10.1038/nature11400. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semova I, Carten JD, Stombaugh J, Mackey LC, Knight R, Farber SA, Rawls JF. 2012. Microbiota regulate intestinal absorption and metabolism of fatty acids in the zebrafish. Cell Host Microbe 12:277–288. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.003. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baquero F. 2015. Causes and interventions: need of a multiparametric analysis of microbial ecobiology. Environ Microbiol Rep 7:13–14. 10.1111/1758-2229.12242. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campos M, Llorens C, Sempere JM, Futami R, Rodriguez I, Carrasco P, Capilla R, Latorre A, Coque TM, Moya A, Baquero F. 2015. A membrane computing simulator of trans-hierarchical antibiotic resistance evolution dynamics in nested ecological compartments (ARES). Biol Direct 10:41. 10.1186/s13062-015-0070-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akinjogunla OJ, Odeyemi AT, Udoinyang EP. 2012. Cockroaches (Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica): reservoirs of multi drug resistant (MDR) bacteria in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. Sci J Biol Sci 1:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schauer C, Thompson CL, Brune A. 2012. The bacterial community in the gut of the Cockroach Shelfordella lateralis reflects the close evolutionary relatedness of cockroaches and termites. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2758–2767. 10.1128/AEM.07788-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engel P, Moran NA. 2013. The gut microbiota of insects—diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev 37:699–735. 10.1111/1574-6976.12025. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegfried BD, Scott SC. 1996. Insecticide resistance mechanisms in the German cockroach, Blatella germanica. Am Chem Soc 96:218–229. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubus JC, Guerra MT, Bodiou AC. 2001. Cockroach allergy and asthma. Allergy 56:351–352. 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00109.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menasria T, Moussa F, El-Hamza S, Tine S, Megri R, Chenchouni H. 2014. Bacterial load of German cockroach (Blattella germanica) found in hospital environment. Pathog Glob Health 108:141–147. 10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000136. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pai HH, Chen WC, Peng CF. 2005. Isolation of bacteria with antibiotic resistance from household cockroaches (Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica). Acta Trop 93:259–265. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.11.006. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carrasco P, Pérez-Cobas AE, van de Pol C, Baixeras J, Moya A, Latorre A. 2014. Succession of the gut microbiota in the cockroach Blattella germanica. Int Microbiol 17:99–109. 10.2436/20.1501.01.212. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.López-Sánchez MJ, Neef A, Peretó J, Patiño-Navarrete R, Pignatelli M, Latorre A, Moya A. 2009. Evolutionary convergence and nitrogen metabolism in Blattabacterium strain Bge, primary endosymbiont of the cockroach Blattella germanica. PLoS Genet 5:e1000721. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000721. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pérez-Cobas AE, Maiques E, Angelova A, Carrasco P, Moya A, Latorre A. 2015. Diet shapes the gut microbiota of the omnivorous cockroach Blattella germanica. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 91:fiv022. 10.1093/femsec/fiv022. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patiño-Navarrete R, Moya A, Latorre A, Peretó J. 2013. Comparative genomics of Blattabacterium cuenoti: the frozen legacy of an ancient endosymbiont genome. Genome Biol Evol 5:351–361. 10.1093/gbe/evt011. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabree ZL, Kambhampati S, Moran NA. 2009. Nitrogen recycling and nutritional provisioning by Blattabacterium, the cockroach endosymbiont. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:19521–19526. 10.1073/pnas.0907504106. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blekhman R, Goodrich JK, Huang K, Sun Q, Bukowski R, Bell JT, Spector TD, Keinan A, Ley RE, Gevers D, Clark AG. 2015. Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol 16:191. 10.1186/s13059-015-0759-1. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson CL, Wang B, Holmes AJ. 2008. The immediate environment during postnatal development has long-term impact on gut community structure in pigs. ISME J 2:739–748. 10.1038/ismej.2008.29. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoy YE, Bik EM, Lawley TD, Holmes SP, Monack DM, Theriot JA, Relman DA. 2015. Variation in taxonomic composition of the fecal microbiota in an inbred mouse strain across individuals and time. PLoS One 10:e0142825. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142825. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, Turnbaugh PJ, Ramey RR, Bircher JS, Schlegel ML, Tucker TA, Schrenzel MD, Knight R, Gordon JI. 2008. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320:1647–1651. 10.1126/science.1155725. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pluznick JL. 2014. Gut microbes and host physiology: what happens when you host billions of guests? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 5:91. 10.3389/fendo.2014.00091. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishnan S, Alden N, Lee K. 2015. Pathways and functions of gut microbiota metabolism impacting host physiology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 36:137–145. 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.08.015. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, Shastri GG, Ann P, Ma L, Nagler CR, Ismagilov RF, Mazmanian SK, Hsiao EY. 2015. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 161:264–276. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gross EM, Brune A, Walenciak O. 2008. Gut pH, redox conditions and oxygen levels in an aquatic caterpillar: potential effects on the fate of ingested tannins. J Insect Physiol 54:462–471. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.11.005. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryu JH, Kim SH, Lee HY, Bai JY, Nam YD, Bae JW, Lee DG, Shin SC, Ha EM, Lee WJ. 2008. Innate immune homeostasis by the homeobox gene caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science 319:777–782. 10.1126/science.1149357. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ke J, Sun JZ, Nguyen HD, Singh D, Lee KC, Beyenal H, Chen SL. 2010. In-situ oxygen profiling and lignin modification in guts of wood-feeding termites. Insect Sci 17:277–290. 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2010.01336.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brooks MA, Richards AG. 1955. Intracellular symbiosis in cockroaches. I. Production of aposymbiotic cockroaches. Biol Bull 109:22–39. 10.2307/1538656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sacchi L, Nalepa CA, Bigliardi E, Lenz M, Bandi C, Corona S, Grigolo A, Lambiase S, Laudani U. 1998. Some aspects of intracellular symbiosis during embryo development of Mastotermes darwiniensis (Isoptera: Mastotermitidae). Parassitologia 40:309–316. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sacchi L, Grigolo A. 1989. Endocytobiosis in Blattella germanica L. (BLATTODEA): recent acquisitions. Endocytobiosis Cell Res 6:121–147. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sacchi L, Corona S, Grigolo A, Laudani U, Selmi MG, Bigliardi E. 1996. The fate of the endocytobionts of Blattella germanica (Blattaria: Blattellidae) and Periplaneta americana (Blattaria: Blattidae) during embryo development. Ital J Zool (Modena) 63:1–11. 10.1080/11250009609356100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aguilera L, Marquetti MC, Fuentes O, Navarro A. 1998. Efecto de 2 dietas sobre aspectos biológicos de Blattella germanica (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae) en condiciones de laboratorio. Rev Cubana Med Trop 50:143–149. [PubMed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Colman DR, Toolson EC, Takacs-Vesbach CD. 2012. Do diet and taxonomy influence insect gut bacterial communities? Mol Ecol 21:5124–5137. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05752.x. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yun JH, Roh SW, Whon TW, Jung MJ, Kim MS, Park DS, Yoon C, Nam YD, Kim YJ, Choi JH, Kim JY, Shin NR, Kim SH, Lee WJ, Bae JW. 2014. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5254–5264. 10.1128/AEM.01226-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levin BR, McCall IC, Perrot V, Weiss H, Ovesepian A, Baquero F. 2017. A numbers game: ribosome densities, bacterial growth, and antibiotic-mediated stasis and death. mBio 8:e02253-16. 10.1128/mBio.02253-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, Sengamalay N, Ott S, Brotman RM, Ravel J. 2014. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2:6. 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5069–5072. 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hammad KM, Mahdy HM. 2012. Antibiotic resistant-bacteria associated with the cockroach, Periplaneta americana collected from different habitat in Egypt. N Y Sci J 5:198–206. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haghi FM, Nikookar H, Hajati H, Harati MR, Shafaroudi MM, Yazdani-Charati J, Ahanjan M. 2014. Evaluation of bacterial infection and antibiotic susceptibility of the bacteria isolated from cockroaches in educational hospitals of Mazandaran University of medical sciences. Bull Environ Pharmacol Life Sci 3:25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wannigama DL, Dwivedi R, Zahraei-Ramazani A. 2013. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of gram-negative pathogenic bacteria species isolated from Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica in Varanasi, India. J Arthropod Borne Dis 8:10–20. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Atlas RM. 2010. Handbook of Microbiological Media, 4th ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC, and CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu SW, Dornbusch K, Kronvall G, Norgren M. 1999. Characterization and nucleotide sequence of a Klebsiella oxytoca cryptic plasmid encoding a CMY-type β-lactamase: confirmation that the plasmid-mediated cephamycinase originated from the Citrobacter freundii AmpC β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:1350–1357. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang TW, Wang JT, Lauderdale TL, Liao TL, Lai JF, Tan MC, Lin AC, Chen YT, Tsai SF, Chang SC. 2013. Complete sequences of two plasmids in a blaNDM-1-positive Klebsiella oxytoca isolate from Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4072–4076. 10.1128/AAC.02266-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akingbade A, Balogun SA, Ojo DA, Afolabi RO, Motayo BO, Okerentugba PO, Okonko IO. 2012. Plasmid profile analysis of multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from wound infections in South West, Nigeria. World Appl Sci J 20:766–775. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwarz FV, Perreten V, Teuber M. 2001. Sequence of the 50-kb conjugative multiresistance plasmid pRE25 from Enterococcus faecalis RE25. Plasmid 46:170–187 10.1006/plas.2001.1544. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thompson JK, Collins MA. 2003. Completed sequence of plasmid pIP501 and origin of spontaneous deletion derivatives. Plasmid 50:28–35. 10.1016/S0147-619X(03)00042-8. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perreten V, Teuber M. 1995. Antibiotic resistant bacteria in fermented dairy products. A new challenge for raw milk cheeses? In Proceedings of the Symposium on Residues of Antimicrobial Drugs and other Inhibitors in Milk, 28-31 August 1995, Kiel, Germany. International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tauch A, Krieft S, Kalinowski J, Pühler A. 2000. The 51,409-bp R-plasmid pTP10 from the multiresistant clinical isolate Corynebacterium striatum M82B is composed of DNA segments initially identified in soil bacteria and in plant, animal, and human pathogens. Mol Gen Genet 263:1–11. 10.1007/PL00008668. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horodniceanu T, Bouanchaud DH, Bieth G, Chabbert YA. 1976. R plasmids in Streptococcus agalactiae (group B). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 10:795–801. 10.1128/AAC.10.5.795. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silva-Rocha R, Martínez-García E, Calles B, Chavarría M, Arce-Rodríguez A, de Las Heras A, Páez-Espino AD, Durante-Rodríguez G, Kim J, Nikel PI, Platero R, de Lorenzo V. 2013. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA): a coherent platform for the analysis and deployment of complex prokaryotic phenotypes. Nucleic Acids Res 41(D1):D666–D675. 10.1093/nar/gks1119. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vilanova C, Tanner K, Dorado-Morales P, Villaescusa P, Chugani D, Frías A, Segredo E, Molero X, Fritschi M, Morales L, Ramón D, Peña C, Peretó J, Porcar M. 2015. Standards not that standard. J Biol Eng 9:17. 10.1186/s13036-015-0017-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marshall BM, Levy SB. 2011. Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clin Microbiol Rev 24:718–733. 10.1128/CMR.00002-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martínez JL, Baquero F, Andersson DI. 2007. Predicting antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:958–965. 10.1038/nrmicro1796. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]