Abstract

Introduction

Laryngeal mask airway (LMA) use in neonatal resuscitation is limited despite existing evidence and recommendations. This survey investigated the knowledge and experience of healthcare providers on the use of the LMA and explored barriers and solutions for implementation.

Methods

This online, cross-sectional survey on LMA in neonatal resuscitation involved healthcare professionals of the Union of European Neonatal and Perinatal Societies (UENPS).

Results

A total of 858 healthcare professionals from 42 countries participated in the survey. Only 6% took part in an LMA-specific course. Some delivery rooms were not equipped with LMA (26.1%). LMA was mainly considered after the failure of a face mask (FM) or endotracheal tube (ET), while the first choice was limited to neonates with upper airway malformations. LMA and FM were considered easier to position but less effective than ET, while LMA was considered less invasive than ET but more invasive than FM. Participants felt less competent and experienced with LMA than FM and ET. The lack of confidence in LMA was perceived as the main barrier to its implementation in neonatal resuscitation. More training, supervision, and device availability in delivery wards were suggested as possible actions to overcome those barriers.

Conclusion

Our survey confirms previous findings on limited knowledge, experience, and confidence with LMA, which is usually considered an option after the failure of FM/ET. Our findings highlight the need for increasing the availability of LMA in delivery wards. Moreover, increasing LMA training and having an LMA expert supervisor during clinical practice may improve the implementation of LMA use in neonatal clinical practice.

Keywords: Laryngeal mask, Neonate, Resuscitation, Supraglottic airway device

Introduction

In 1983, Dr. Brain published the first article on the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) [1]. Since its introduction into clinical practice, airway management in adult patients needing anesthesia or resuscitation procedures has been progressively revolutionized [2, 3]. Compared to the endotracheal tube (ET), the advantages of the LMA include avoiding laryngoscopy and its associated adverse effects, reduced local damage to the upper respiratory tract, and ease of positioning [4–6]. In neonates, the LMA has been used in different clinical circumstances, including resuscitation, congenital upper airway malformations, anesthesia, postnatal transport, and surfactant administration [4–6].

LMAs are classified by generation and number of channels (first, second, and third) and by sealing mechanism (cuffed or uncuffed) [5]. Neonatal LMA size 1 is indicated for neonates weighing 2–5 kg and is available in both cuffed and uncuffed models. Recently, a smaller model (size 0.0) has become available for neonates weighing less than 2 kg (Air-Qsp Intubating laryngeal mask manufactured by Cookgas LLC, St. Luis, Missouri, United States).

The LMA appeared for the first time in the American Heart Association/American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines in 2000 [7], and the latest editions of the American and European guidelines on neonatal resuscitation include the LMA in their algorithms [8, 9]. Two recent systematic reviews showed that the LMA is more effective than the face mask (FM) during neonatal resuscitation [10, 11]. The Neonatal Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) suggests that a supraglottic airway may be used instead of an FM for resuscitation of late-preterm and term infants immediately after birth [12].

Although the existing evidence favors the use of the LMA and official recommendations reflect this, the use of the LMA by neonatologists in clinical practice remains very limited [13, 14]. Understanding the reasons for this limitation is necessary together with potential interventions to augment knowledge and promote the use of the LMA by neonatal health caregivers involved. In this survey, we aimed to investigate the knowledge of and experience with LMA of the healthcare professionals who are members of the Union of European Neonatal and Perinatal Societies (UENPS) and to explore barriers and possible solutions for implementing its use in neonates.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey on experience with and opinion on the LMA among healthcare professionals of UENPS. The survey was conceived, endorsed, and coordinated by UENPS. It was also endorsed by the European Resuscitation Council (ERC), the Italian Society of Neonatology (SIN), and the European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC).

The UENPS survey manager contacted the national presidents of UENPS to promote participation in the survey among the members. The presidents invited healthcare professionals involved in neonatal care and neonatal resuscitation at birth to participate in the survey via email and information on the national society’s websites. In addition, the survey was promoted during neonatology congresses across Europe using a slide with a QR code for access to the survey. The survey was hosted by a web survey service (www.surveymonkey.com) and was active between January 1 and July 31, 2023.

Survey access acted as consent for participation. This consent procedure and the survey were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Padua, Italy (number 396n/AO/23).

After a literature review and discussion among experts, a team of experienced neonatologists of UENPS and the ERC developed the survey, which included multiple-choice, fill-in, and yes/no questions. The survey was revised for clarity and content, pilot tested with five neonatologists who were not involved in the design, and was further revised before dissemination.

The survey was written in English. To increase the involvement of the non-English-speaking participants, the survey was translated into local languages (Bulgarian, Croatian, Estonian, French, Greek, Italian, Lithuanian, Russian, and Turkish); the translations were arranged by the national neonatal and perinatal societies. The survey (online Suppl. Material; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000538808) included 44 items about (i) participant characteristics, (ii) LMA availability, (iii) training and experience with LMA on manikins and newborns, (iv) comparison between LMA, FM, and ET in terms of use and preference, (v) clinical scenarios, and (vi) opinions on why the LMA is not used more in neonatal resuscitation and possible actions to implement LMA use.

Data were examined with descriptive analyses using R 4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [15]. Categorical data were summarized as numbers and percentages, and continuous data as median and interquartile range. A comparison between experienced neonatal resuscitators (neonatologists and anesthesiologists) and less experienced neonatal resuscitators (other participants) was performed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 858 healthcare professionals from 42 countries participated in the survey, and 747/858 filled in the whole survey (completion rate 87.1%). Information on participants and laryngeal mask training is shown in online Supplementary Table 1. The survey included 543 neonatologists (63%), 97 nurses (11%), 94 pediatricians (11%), 50 midwives (6%), 44 pediatric residents (5%), 16 obstetricians (2%), and 14 anesthesiologists (2%). Experience in the delivery ward was <5 years in 185 participants (22%), 5–10 years in 160 (19%), 11–20 years in 243 (28%), and >20 years in 270 (31%). Only a few participants had taken an LMA-specific course (53/836, 6%), while many had participated in a session on LMA use within a neonatal resuscitation course (523/836, 63%).

Most delivery rooms were equipped with an LMA (69%), and the I-gel (Intersurgical, Berkshire, UK) was the most frequent model (48%). The full-term model (LMA size 0.5–1) was available in 67%, and the preterm model (LMA size 0.0) in 17%. The uncuffed and cuffed models were similarly available (50–51%) (online Suppl. Table 2).

Overall, participants reported more experience in placing the LMA on manikins (71%) than on newborns (23%), and most stated less than 5 placements (44% and 66%, respectively) (Table 1). Positioning the device was considered less difficult with the LMA (92%) and the FM (94%) than with the ET (72%). When used on newborns, only 9% of participants considered the LMA as their first choice, while most used it as their second choice after failure with the FM (30%) or ET (43%).

Table 1.

Experience in using the LMA in manikins and newborns

| Experience in manikins | ||

|---|---|---|

| variable | categories | total (n = 858), n (%) |

| Have you ever placed the LMA in a neonatal manikin? | No | 230 (26.8) |

| Yes | 606 (70.6) | |

| No reply | 22 (2.6) | |

| How many insertions did you perform in total? | <5 | 264/606 (43.6) |

| 5–10 | 172/606 (28.4) | |

| 11–20 | 56/606 (9.2) | |

| >20 | 110/606 (18.2) | |

| I do not know | 4/606 (0.7) | |

| What technique did you use to insert the LMA? | Pushing the LMA against the palate | 292/606 (48.2) |

| Pushing the LMA against the base of the tongue | 103/606 (17) | |

| No particular landmarks because the LMA found the right place automatically | 141/606 (23.3) | |

| Using a laryngoscope as a tongue depressor | 68/606 (11.2) | |

| Using another instrument as a tongue depressor | 12/606 (2) | |

| I do not know | 16/606 (2.6) | |

| How much air did you put in the cuff? | I followed the manufacturer’s instructions | 300/606 (49.5) |

| I used a test balloon | 53/606 (8.7) | |

| I did not use a cuffed LMA | 205/606 (33.8) | |

| I do not know | 48/606 (7.9) | |

| Before removing the LMA, did you remove the air from the cuff? | No | 33/606 (5.4) |

| Yes | 338/606 (55.8) | |

| I do not know | 30/606 (5) | |

| I did not use cuffed LMA | 205/606 (33.8) | |

| Difficult, n (%) | Quite easy, n (%) | Very easy, n (%) | I do not know, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How do you consider positioning the device (defined as placing the device in the correct position) in a manikin | |||||

| LMA | 46/606 (7.6) | 306/606 (50.5) | 247/606 (40.8) | 7/606 (1.2) | |

| FM | 36/606 (5.9) | 290/606 (47.9) | 273/606 (45) | 7/606 (1.2) | |

| ET | 169/606 (27.9) | 309/606 (51) | 121/606 (20) | 7/606 (1.2) | |

| Experience with newborns | ||

|---|---|---|

| variable | categories | total (n = 858), n (%) |

| Have you ever placed the LMA in a newborn infant? | No | 632 (73.7) |

| Yes | 197 (23) | |

| No reply | 29 (3.4) | |

| What LMA size did you use? | 0 | 23/197 (11.7) |

| 0.5 | 2/197 (1) | |

| 1 | 119/197 (60.4) | |

| 1.5 | 4/197 (2) | |

| 2 | 11/197 (5.6) | |

| I do not know | 38/197 (19.3) | |

| In how many newborns did you place the LMA? | <5 | 130/197 (66.0) |

| 5–10 | 36/197 (18.3) | |

| 11–20 | 7/197 (3.6) | |

| >20 | 13/197 (6.6) | |

| I do not know | 11/197 (5.6) | |

| On what occasions did you use the LMA? | In neonatal resuscitation, as a first choice in neonates requiring positive pressure ventilation | 17/197 (8.6) |

| In neonatal resuscitation, as a second choice after the failure of face mask ventilation | 60/197 (30.5) | |

| In neonatal resuscitation, as a second choice after the failure of tracheal intubation | 85/197 (43.1) | |

| In neonatal resuscitation, due to a lack of intubation skills | 20/197 (10.2) | |

| During neonatal transport | 11/197 (5.6) | |

| In elective conditions (i.e., neonates needing anesthesia) | 41/197 (20.8) | |

| Other condition (malformations) | 25/197 (12.7) | |

| Other condition (surfactant administration) | 6/197 (3) | |

| In which situation did you use the LMA for the first time during neonatal resuscitation? | A more expert colleague guided me | 21/197 (10.7) |

| I was the most experienced healthcare provider on neonatal resuscitation, and I had no problems | 79/197 (40.1) | |

| I was the most experienced healthcare provider on neonatal resuscitation, and “I tried” despite I was not an expert in LMA use | 70/197 (35.5) | |

| Other situations | 16/197 (8.1) | |

| No reply | 11/197 (5.6) | |

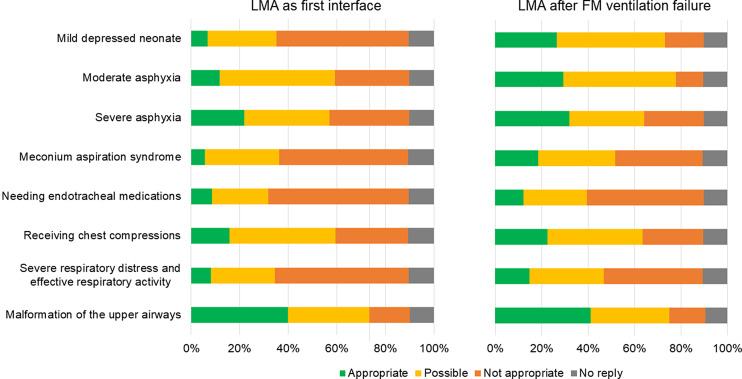

In specific clinical situations (Fig. 1), using the LMA as the primary interface was considered appropriate mostly for neonates with upper airway malformations (40%) and likely to be used for those with moderate/severe asphyxia (35–47%) or receiving chest compressions (44%). Furthermore, using the LMA after FM ventilation failure was considered appropriate mostly in neonates with upper airway malformations (41%) or severe asphyxia (32%) and likely to be used for mildly depressed neonates (47%) or those with moderate asphyxia (49%) or receiving chest compressions (41%). Numerical data are reported in online Supplementary Table 3. Online Supplementary Table 4 reports the preference order of the LMA, FM, and ET in different clinical scenarios.

Fig. 1.

Participants’ opinion on using LMA as the first interface or after face mask ventilation failure in specific clinical situations (numerical data in online suppl. Table 3).

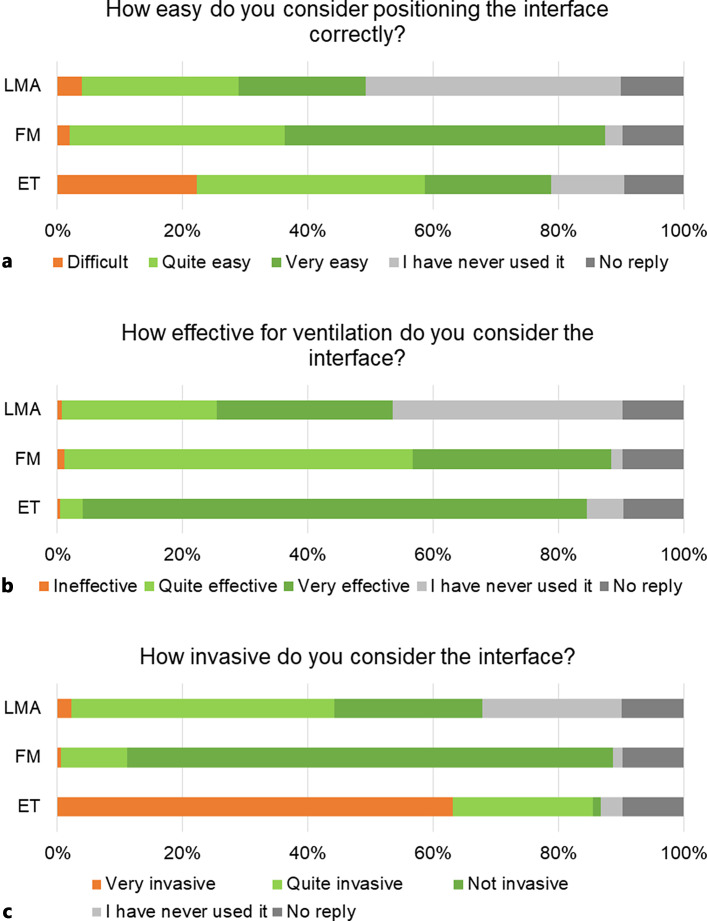

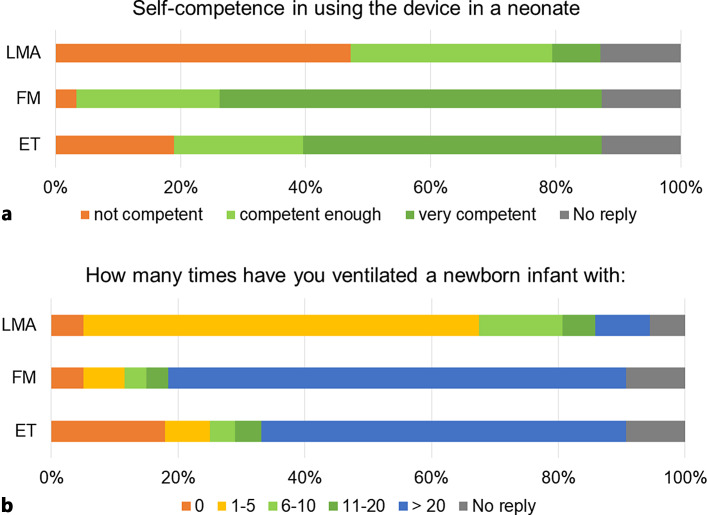

Participants considered the LMA and FM easier to position but less effective than the ET, while the LMA was perceived as less invasive than the ET but more invasive than the FM (Fig. 2). Overall, participants felt less competent and less experienced with the LMA than with the FM and ET (Fig. 3). Numerical data are reported in online Supplementary Tables 5–7.

Fig. 2.

Participants’ opinion on positioning, effectiveness, and invasiveness of LMA, FM, and ET and self-competence and experience about using the devices (numerical data in online suppl. Table 5).

Fig. 3.

Participants’ self-competence and experience with using LMA, FM, and ET (numerical data in online suppl. Tables 6–7).

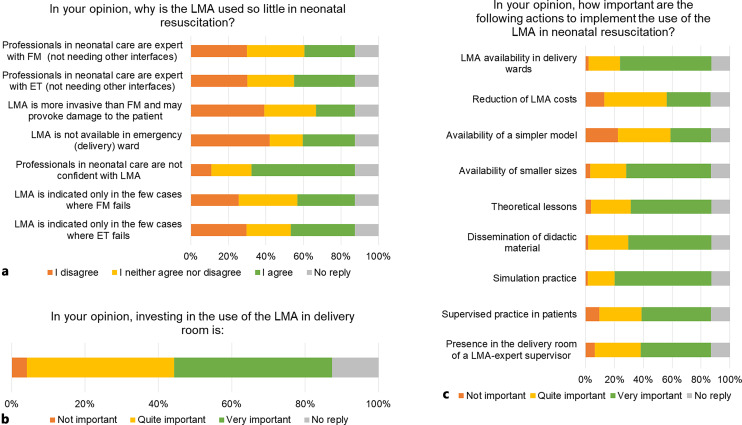

When asked about the reasons for the limited use of LMA in neonatal resuscitation, participants indicated mainly the lack of confidence in using the LMA, while there were no clear signals regarding the other reasons (Fig. 4). Overall, many participants recognized the importance of investing in LMA use by delivery room personnel and indicated training, supervision, and availability of the device in the delivery ward as possible actions to implement LMA use (Fig. 4). Numerical data are reported in online Supplementary Table 8.

Fig. 4.

Participants’ opinion on the reasons for the limited use of LMA in neonatal resuscitation and possible actions to implement it (numerical data in online suppl. Table 8).

When stratifying the results according to the level of experience in neonatal resuscitation, the LMA was considered appropriate in neonates with upper airway malformations more frequently by experienced neonatal resuscitators (neonatologists and anesthesiologists) compared to less experienced neonatal resuscitators (other participants) (p < 0.0001; online Suppl. Table 9). In addition, participants’ opinion on positioning, effectiveness, and invasiveness of the LMA showed some differences between experienced and less experienced neonatal resuscitators (p < 0.001) as summarized in online Supplementary Table 10. Participants’ self-confidence and experience with using the LMA were higher in experienced neonatal resuscitators (p < 0.0001; online suppl. Tables 11–12). Participants reported heterogeneous opinions both about the reasons for the limited use of the LMA and possible actions to implement its use in neonatal resuscitation and about the importance of investing in the LMA in the delivery room, with many less experienced neonatal resuscitators opting for no reply (online suppl. Tables 13–15).

Discussion

This survey offers insight into the knowledge of and experience with the LMA among healthcare professionals of UENPS and suggests possible actions to increase LMA use in neonatal resuscitation. Overall, we found areas of improvement regarding knowledge of the device, as a quarter of the participants with access to an LMA in the delivery ward were unaware of the size or the presence of a gastric access on the device. Of note, many participants had never attended a course that included training with the LMA and only a few had attended a specific course focused on this device. The low exposure to LMA training has been already reported in previous surveys dated 2004–2022 [16–19], while improved results were shown in a recent Canadian/US survey [13]. When having to use the LMA in clinical practice, many participants were not expert in using it but found themselves to be the most experienced healthcare provider in the room and just “tried.”

Hands-on sessions play an important part in neonatal resuscitation training. Although most participants had the chance to place the LMA on a manikin, many of them reported a limited number of attempts and did not use the original recommended technique. The LMA should be positioned by pushing it against the palate, keeping in mind the swallowing mechanism [20]. Of note, many participants reported deflating the cuff before removing the LMA. This aspect is still under debate as removing an LMA with a deflated cuff may be less traumatic and reduce the risk of cuff damage, while removing an LMA with an inflated cuff maintains the seal for ventilation and airway protection and favors oral secretion removal [20].

Overall, we found limited experience with the LMA in clinical practice, as only a quarter of the participants had had the chance to place the LMA on a newborn. This was compounded by the limited availability of the LMA in the resuscitation trolley in the delivery wards – despite the American and European guidelines on neonatal resuscitation including the LMA in their algorithms [8, 9] – and the lack of confidence in using the LMA. In fact, the participants felt more confident with the FM, and this mirrored its more frequent use in clinical practice. The limited experience with the LMA in clinical practice and the lack of confidence have been reported previously [13, 16–19, 21].

According to participants’ opinion, the LMA was used mainly as a second choice after FM/ET failure in agreement with previous reports [13, 17], despite the most recent ILCOR treatment recommendations advising that the LMA should be used in place of an FM for resuscitation of late-preterm and term infants immediately after birth [12]. Most participants would use the FM before the LMA in mildly asphyxiated neonates, and we believe that they may perceive the LMA as being more invasive than the FM. The perception of the LMA being invasive has been reported previously despite the literature supporting the safety of LMA [10, 22–24]. This perception may be influenced by low confidence in using the device rather than low confidence in its effectiveness. We believe that placing the device in nonemergency situations can increase experience and confidence, leading to beneficial effects when prompted to use it in emergency situations. In neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid, the LMA was frequently considered inappropriate as a first or second choice, despite the lack of evidence [8, 9] and promising results from a recent trial [24]. Mixed opinions emerged about using the LMA in neonates receiving chest compressions, which mirrored the conflicting messages from American and European guidelines indicating that the LMA should not be used or used as a second option, respectively [8, 9]. The literature offers only a few studies supporting the use of the LMA in lambs and adults receiving chest compressions [25, 26], but data on its use on neonates are lacking. Interestingly, some participants used the LMA on newborns with upper airway malformations (such as Pierre Robin syndrome). Most participants considered the LMA as a first choice in such cases, where FM ventilation and/or ET are expected to be difficult or unfeasible, and the LMA becomes potentially lifesaving [4–6, 13, 14, 17]. Few participants used the LMA for surfactant administration (SALSA), which is gathering interest because it avoids invasive procedures (such as laryngoscopy) and requires less skill [22, 23]. As above, we believe that placing the device in nonemergency cases can improve competence.

Using the LMA in very preterm babies is a recognized challenge due to the lack of an adequately sized model [6]. Our survey showed that one out of 6 participants had access to a small model (LMA size 0.0), which has recently become available for neonates weighing less than 2 kg. Despite such encouraging data, smaller models may be more appropriate for extremely low-birth-weight infants.

Our survey highlighted that the lack of confidence in the LMA among healthcare providers was perceived as the main barrier to LMA use in neonatal resuscitation, as previously reported [21]. Heterogeneous opinions were offered regarding other possible barriers, such as the LMA being restricted to a few cases after failure of FM/ET, or professionals being experts with FM/ET and not needing other interfaces, which may again be associated with limited training and confidence. The reader should be aware that most participants were neonatologists with high experience in the delivery ward, who may favor the ET over the LMA in comparison with other healthcare providers with less exposure to neonatal emergency procedures. The current debate on the LMA highlights its role in rural/peripheral hospitals or settings with low patient volume and staff with limited skills [6]. Improving the training (especially practical exercises on neonatal manikins), having an LMA-expert supervisor during clinical practice, and increasing the availability of the LMA, including smaller sizes, in the delivery wards were indicated as the most important actions to overcome such barriers [13, 27].

As expected, the varying experience in neonatal resuscitation among participants contributed to the heterogeneity of some findings. Overall, the different approaches to LMA and opinions on barriers and facilitators for LMA implementation in neonatal resuscitation mirrored the higher experience in airway management of neonatologists and anesthesiologists. It can be argued that the increased confidence in LMA skills could be associated with a higher level of self-confidence and general experience in neonatal resuscitation. Hence, we believe that experienced neonatal resuscitators may be the most appropriate target in LMA implementation.

The strengths of the survey include the large sample and extensive experience in the neonatal delivery ward care of the participants. Furthermore, it adds some direct comparisons between the LMA, FM, and ET to the literature in terms of the self-confidence, experience, and opinions of healthcare providers. The survey has also some limitations that should be acknowledged. The pilot testing involved only one group of survey respondents, while a heterogeneous sample may have identified further areas for improvement of the survey. Some questions in the survey might lack equipoise as the wording may have been interpreted as favoring the LMA over other interfaces. The participation was voluntary, and the survey may have missed data from healthcare providers with less experience with the LMA who may have perceived the topic as outside their knowledge or competence. Most participants were neonatologists; hence, the generalizability of the findings should be limited accordingly. In addition, we did not collect data on participants’ specific experience in neonatal resuscitation. Moreover, we were not aware of whether the participants were instructors of neonatal resuscitation programs, which could be associated with more experience and confidence with the LMA [13, 21]. Within such limitations, we believe that our findings provide original and useful information about LMA knowledge and experience of healthcare providers, as well as perceived barriers and solutions for implementation. This information may serve as a current – although incomplete – overview of LMA use among a large scientific society and may be the basis for further investigations on specific aspects of this topic.

Conclusions

This is the first survey on experience with and opinions of the LMA among UENPS healthcare professionals involved in neonatal care. The findings reflect the position after the publication of the guidelines in 2021, which incorporated the LMA into the European algorithm. Our study confirms previous findings on limited knowledge, experience, and confidence with the LMA, which is usually considered an option after failure of FM/ET. Our findings highlight the need to increase the availability of the LMA in delivery wards. Moreover, programs should prioritize increasing LMA training and having an LMA expert supervisor during clinical practice to improve the implementation of LMA use in neonatal clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the participants of the survey.

Statement of Ethics

The survey was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Padova (Italy) (Prot. No. 396n/AO/23). Written informed consent to participate was not directly obtained but inferred by completion of the questionnaire.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no potential conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

Daniele Trevisanuto contributed to the study concept, preparation of the survey, data interpretation, and writing the initial draft. Camilla Gizzi, Artur Beke, Giuseppe Buonocore, Antonia Charitou, Manuela Cucerea, Boris Filipović-Grčić, Nelly Georgieva Jekova, Esin Koç, Joana Saldanha, Dalia Stoniene, Heili Varendi, Giuseppe De Bernardo, John Madar, Marije Hogeveen, Luigi Orfeo, Fabio Mosca, Giulia Vertecchi, and Corrado Moretti contributed to the study concept, preparation of the survey, and critical review of the manuscript. Francesco Cavallin contributed to data analysis and writing the initial draft. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Brain AI. The laryngeal mask-a new concept in airway management. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55(8):801–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaida S, Gaitini L, Somri M, Matter I, Prozesky J. Airway management during the last 100 years. Crit Care Clin. 2023;39(3):451–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soar J, Nicholson TC, Parr MJ, Berg KM, Böttiger BW, Callaway CW, et al. Advanced airway management during adult cardiac arrest consensus on science with treatment recommendations. Brussels, Belgium: International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Advanced Life Support Task Force; 2019. Available from: http://ilcor.org. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trevisanuto D, Micaglio M, Ferrarese P, Zanardo V. The laryngeal mask airway: potential applications in neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(6):F485–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bansal SC, Caoci S, Dempsey E, Trevisanuto D, Roehr CC. The laryngeal mask airway and its use in neonatal resuscitation: a critical review of where we are in 2017/2018. Neonatology. 2018;113(2):152–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Shea JE, Scrivens A, Edwards G, Roehr CC. Safe emergency neonatal airway management: current challenges and potential approaches. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022;107(3):236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niermeyer S, Kattwinkel J, Van Reempts P, Nadkarni V, Phillips B, Zideman D, et al. International guidelines for neonatal resuscitation: an excerpt from the guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care: international consensus on science. Contributors and reviewers for the neonatal resuscitation guidelines. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):E29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aziz K, Lee HC, Escobedo MB, Hoover AV, Kamath-Rayne BD, Kapadia VS, et al. Part 5: neonatal resuscitation: 2020 American Heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_Suppl l_2):S524–S550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Madar J, Roehr CC, Ainsworth S, Ersdal H, Morley C, Rüdiger M, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation. 2021;161:291–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamada NK, McKinlay CJ, Quek BH, Schmölzer GM, Wyckoff MH, Liley HG, et al. Supraglottic airways compared with face masks for neonatal resuscitation: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2022;150(3):e2022056568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diggikar S, Krishnegowda R, Nagesh KN, Lakshminrusimha S, Trevisanuto D. Laryngeal mask airway versus face mask ventilation or intubation for neonatal resuscitation in low-and-middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023;108(2):156–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Supraglottic airways for neonatal resuscitation NLS #5340 . International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) Neonatal Life Support Task Force; 2022. Available from: http://ilcor.org. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robin B, Soghier LM, Vachharajani A, Moussa A. Laryngeal mask airway clinical use and training: a survey of north American neonatal health care professionals. Am J Perinatol. 2023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cavallin F, Brombin L, Turati M, Sparaventi C, Doglioni N, Villani PE, et al. Laryngeal mask airway in neonatal stabilization and transport: a retrospective study. Eur J Pediatr. 2023;182(9):4069–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trevisanuto D, Ferrarese P, Zanardo V, Chiandetti L. Laryngeal mask airway in neonatal resuscitation: a survey of current practice and perceived role by anaesthesiologists and paediatricians. Resuscitation. 2004;60(3):291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goel D, Shah D, Hinder M, Tracy M. Laryngeal mask airway use during neonatal resuscitation: a survey of practice across newborn intensive care units and neonatal retrieval services in Australian New Zealand Neonatal Network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56(9):1346–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Belkhatir K, Scrivens A, O’Shea JE, Roehr CC. Experience and training in endotracheal intubation and laryngeal mask airway use in neonates: results of a national survey. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106(2):223–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lyra JC, Guinsburg R, de Almeida MFB, Variane GFT, Souza Rugolo LMS. Use of laryngeal mask for neonatal resuscitation in Brazil: a national survey. Resusc Plus. 2023;13:100336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brimacombe JR. Laryngeal mask anesthesia: principles and practice. 2nd ed.Saunders Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shah BA, Foulks A, Lapadula MC, McCoy M, Hallford G, Bedwell S, et al. Laryngeal mask use in the neonatal population: a survey of practice providers at a regional tertiary care center in the United States. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40(14):1551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Devi U, Roberts KD, Pandita A. A systematic review of surfactant delivery via laryngeal mask airway, pharyngeal instillation, and aerosolization: methods, limitations, and outcomes. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57(1):9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calevo MG, Veronese N, Cavallin F, Paola C, Micaglio M, Trevisanuto D. Supraglottic airway devices for surfactant treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 2019;39(2):173–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pejovic NJ, Myrnerts Höök S, Byamugisha J, Alfvén T, Lubulwa C, Cavallin F, et al. A randomized trial of laryngeal mask airway in neonatal resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mani S, Gugino S, Helman J, Bawa M, Nair J, Chandrasekharan P, et al. Laryngeal mask ventilation with chest compression during neonatal resuscitation: randomized, non-inferiority trial in lambs. Pediatr Res. 2022;92(3):671–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benger JR, Lazaroo MJ, Clout M, Voss S, Black S, Brett SJ, et al. Randomized trial of the i-gel supraglottic airway device versus tracheal intubation during out of hospital cardiac arrest (AIRWAYS-2): patient outcomes at three and six months. Resuscitation. 2020;157:74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mani S, Pinheiro JMB, Rawat M. Laryngeal masks in neonatal resuscitation-A narrative review of updates 2022. Children. 2022;9(5):733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.