Abstract

Background:

Fistulas, abnormal connections between two anatomical structures, significantly impact the quality of life and can result from a variety of causes, including congenital defects, inflammatory conditions, and surgical complications. Stem cell therapy has emerged as a promising alternative due to its potential for regenerative and immunomodulatory effects. This overview of systematic reviews aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy in managing fistulas, drawing on the evidence available.

Methods:

This umbrella review was conducted following the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology to assess the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy for treating various types of fistulas. A comprehensive search was performed across multiple electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Register, and Web of Science up to 5 May 2024. Systematic reviews focusing on stem cell therapy for fistulas were included, with data extracted on study design, stem cell types, administration methods, and outcomes. The quality of the reviews was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 tool, and meta-analyses were conducted using R software version 4.3.

Results:

Nineteen systematic reviews were included in our umbrella review. The stem cell therapy demonstrated by significant improvements in clinical remission rates, with a relative risk (RR) of 1.299 (95% CI: 1.192–1.420). Stem cell therapy enhanced fistula closure rates, both short-term (RR=1.481; 95% CI: 1.036–2.116) and long-term (RR=1.422; 95% CI: 1.091–1.854). The safety analysis revealed no significant increase in the risk of adverse events with stem cell therapy, showing a pooled RR of 0.972 (95% CI: 0.739–1.278) for general adverse events and 1.136 (95% CI: 0.821–1.572) for serious adverse events, both of which indicate a safety profile comparable to control treatments. Re-epithelialization rates also improved (RR=1.44; 95% CI: 1.322–1.572).

Conclusion:

Stem cell therapy shows promise as an effective and safe treatment for fistulas, particularly in inducing remission and promoting closure of complex fistulas. The findings advocate for further high-quality research to confirm these benefits and potentially incorporate stem cell therapy into standard clinical practice for fistula management. Future studies should focus on long-term outcomes and refining stem cell treatment protocols to optimize therapeutic efficacy.

Keywords: efficacy, fistula, meta-analysis, stem cell therapy, systematic review, treatment

Introduction

Highlights

Significant efficacy: stem cell therapy significantly improves clinical remission and fistula closure rates though evidence is limited.

Safety profile: stem cell therapy does not significantly increase adverse or serious adverse event risks.

Positive re-epithelialization: stem cell therapy promotes re-epithelialization, reducing recurrence rates in fistula management.

Call for further research: larger, high-quality trials are needed to validate benefits and optimize stem cell therapy protocols.

Fistulas are abnormal connections or passageways that develop between two anatomical structures or organs that are not typically connected1. These conditions can arise in various body regions and can result from various underlying causes, such as congenital defects, inflammatory conditions, injuries, or surgical complications2. Fistulas can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life, leading to discomfort, pain, and potentially life-threatening complications if left untreated. The treatment of fistulas has traditionally relied on surgical interventions, which can be invasive, carry inherent risks, and may not always provide satisfactory outcomes, particularly in cases of complex or recurrent fistulas3. Consequently, there has been an increasing interest in exploring alternative and innovative therapeutic methods, one of which is stem cell therapy.

Stem cells are unique, undifferentiated cells capable of self-renewal and differentiation into a variety of specialized cell types4. Due to their unique properties, stem cells have emerged as a promising therapeutic modality in regenerative medicine, offering potential solutions for a wide range of medical conditions, including fistulas5,6. The application of stem cell therapy for fistula treatment is based on the premise that these cells can promote tissue regeneration and healing by differentiating into the required cell types and facilitating the repair and restoration of damaged or compromised tissues7,8. Furthermore, stem cells are believed to possess immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties, which may contribute to the resolution of fistulas associated with inflammatory conditions.

Over the past decade, numerous studies have investigated the potential of stem cell therapy in the management of various types of fistulas, including, but not limited to, perianal fistulas, enterocutaneous fistulas, vesicovaginal fistulas, and tracheoesophageal fistulas7. These studies have employed different types of stem cells, such as adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and bone marrow-derived stem cells (BMSCs), administered through various routes and techniques9. While the results of these individual studies have been promising, showcasing the promising advantages of stem cell therapy in fistula management, there is a need for a comprehensive synthesis and evaluation of the available evidence to offer a clearer insight into the efficacy, safety, and potential limitations of this therapeutic approach.

An umbrella review, which is a systematic review of multiple systematic reviews, offers a unique opportunity to consolidate and critically appraise the existing evidence from various systematic reviews on stem cell therapy for fistulas10. By synthesizing the findings from multiple systematic reviews, an umbrella review can offer a thorough summary of the existing evidence for identifying potential gaps or inconsistencies in the literature, and highlight areas that require further research. The primary objective of this umbrella review is to critically evaluate and summarize the evidence from systematic reviews concerning the use of stem cell therapy in the treatment of various types of fistulas. This review aims to assess the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy in managing different types of fistulas, drawing on the evidence available from systematic reviews. Additionally, it seeks to identify the most commonly investigated types of stem cells, the routes of their administration, and the techniques employed in treating fistulas.

Methods

This umbrella review has been conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for umbrella reviews10. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting the study (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D529)11.

Systematic search of databases

Our research team commenced a comprehensive search across multiple electronic databases to procure systematic reviews on stem cell therapy for the treatment of various types of fistulas. The databases included PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Register, and Web of Science. This wide-reaching search strategy was designed to ensure an extensive collection of pertinent literature, covering a diverse range of sources to capture the most relevant data on the topic. The search was from the databases’ inception up to 5th May 2024.

Predefined search strategy

We developed a detailed search strategy to guide our database exploration. This strategy incorporated both controlled vocabulary, such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and free-text keywords to optimize the retrieval of articles. The keywords included ‘fistula’, ‘stem cell therapy’, ‘stem cell transplantation’, and variants thereof. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to combine these terms effectively, enhancing the search specificity and breadth. The complete search strategy used for each database is presented in Table S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D529).

Reference scanning

We examined the reference lists of all retrieved articles, reviews, and other relevant publications to complement our database searches. This manual scanning aimed to identify additional studies that the electronic searches might have missed.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for the systematic reviews were meticulously defined to ensure alignment with the objectives of our study. Specifically, we included systematic reviews that focused on the use of stem cell therapy for treating various types of fistulas. These reviews needed to report specific outcomes, such as efficacy, safety, and long-term effectiveness. Additionally, the reviews were required to provide detailed information on the types of stem cells used, the methods of their administration, and the follow-up periods involved. On the other hand, our exclusion criteria ruled out non-English articles, reviews that failed to provide explicit data on outcomes, and studies that focused on nonhuman subjects. Consequently, only articles published in English were considered for inclusion in our analysis.

Screening of articles

We used semi-automated software named Nested Knowledge for de-duplication and screening of the records. Screening was performed in two stages. First, two independent screeners reviewed the title and abstract of the records. The eligible articles from this step underwent a full-text screening phase. When disagreements between the reviewers arose regarding the eligibility of studies for inclusion, a third independent reviewer was involved to resolve the conflict.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers using a predesigned form to ensure accuracy and consistency. This form allowed for the collection of detailed information about study design, participant characteristics, type of fistula, type of stem cells used, method of administration, outcomes measured, and results. Any differences between reviewers were settled through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

The quality of each selected systematic review was evaluated using the AMSTAR 2 tool, which is specifically designed for appraising systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. This assessment helped determine the strength and reliability of the evidence provided in the reviews.

Statistical analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis of the data retrieved from the systematic reviews where possible12. The I² statistic was employed to evaluate heterogeneity across the studies. A random-effects model was employed in cases of substantial heterogeneity (I² >50%). Each outcome was pooled independently to determine the overall estimate13,14. A 95% CI was considered. All analyses were conducted using two-tailed tests, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed to indicate statistical significance. We used the ‘meta’ and ‘metafor’ packages in R software (version 4.3) to perform the analysis15–17.

Results

Literature search

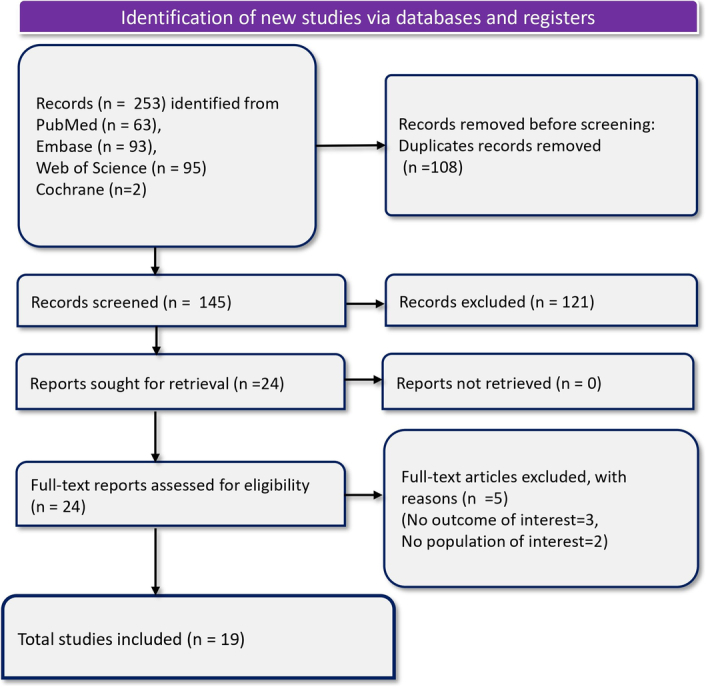

The search across several databases initially identified a total of 253 records: 63 from PubMed, 93 from Embase, 95 from Web of Science, and 2 from Cochrane. After removing 108 duplicate records, 145 records remained and were subsequently screened. Of these, 24 reports were deemed relevant and retrieved for a more detailed review. All 24 reports underwent a full-text assessment for eligibility. During this phase, five reports were excluded for reasons such as not meeting the outcome interests (three reports) and not pertaining to the target population (two reports). Consequently, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. We did not find any additional eligible studies in the manual reference searching. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA flow diagram of the article selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart depicting article selection and screening process.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews

The included systematic reviews extensively covered the use of stem cell therapy for treating various types of fistulas, with a particular focus on those associated with Crohn’s Disease (CD) (Table 1). Spanning searches up to 2023, these reviews encompass a range of study years from 2002 to 2023, illustrating significant progress in research over nearly two decades. The types of studies included vary widely, from RCTs to observational studies and cohort studies, providing a robust cross-section of research methodologies. Each review typically applied rigorous screening and eligibility criteria to focus on studies specifically examining the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapies in the treatment of fistulas. The types of stem cells examined are predominantly MSCs, derived from sources like adipose tissue, bone marrow, and, in some cases, more novel sources like umbilical cord and placenta. The reviews detail various control treatments against which stem cell efficacy was measured, including conventional therapies like fibrin glue, saline solution, and standard-of-care practices. Outcomes assessed in these reviews primarily focus on healing rates, symptom improvement, and adverse events, providing a well-rounded perspective on the effectiveness and safety of the treatments. Notably, the risk of bias in these studies was frequently evaluated using tools like the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, with findings ranging from moderate to high risk, suggesting variability in study quality. The assessment of the quality of these reviews is detailed in Table S3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/D529).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included systematic reviews.

| Study ID | Population | Databases and date of search | Year range of included studies | Number of studies included with study design | Type of stem cells | Type of control | Outcomes | Risk of bias of included studies | Risk of bias tool used | Grade | Publication bias | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernardi 201918 | Individuals with refractory CD | PubMed, ScienceDirect, Jan 2008–Dec 2018 | 2008–2018 | Thirteen RCTs (1 on luminal CD, 12 on perianal fistulizing CD) | Adipose-derived MSCs | Standard treatments, various other treatments | Healing of fistulas, symptom improvement | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Promising results with MSCs in healing perianal fistulas; need for more studies on luminal CD; variability in dosage and administration methods |

| Cao 201719 | Patients diagnosed with CD | PubMed, Web of Science, up to Sep 30, 2016 | 2009–2016 | Fourteen RCTs | ASCs, BM-MSCs | Placebo or standard of care | Overall healing rate, clinical response, AEs | Low to moderate | NOS | Not assessed | Not assessed | MSCs are effective for Crohn’s fistula; CDAI baseline is a candidate for evaluating effectiveness |

| Cao 202120 | Patients with Crohn’s fistula | PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Jun 2005–Aug 2020 | 2005–2020 | Twenty-nine studies (RCTs and cohort studies) | Adipose-derived and BM-MSCs | Placebo, fibrin glue | Healing rate, AEs, CDAI, PDAI, IBDQ, CRP | Moderate to high | NOS | Not assessed | Not assessed | MSCs show a higher healing rate (61.75%) vs. placebo (40.46%) a lower incidence of AEs; the optimal dose is identified as 3 × 10^7 cells/ml |

| Cheng 201921 | Patients with perianal CD | PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, CNKI, up to Oct 2018 | 2005–2018 | Thirteen studies (five RCTs, eight nonrandomized experimental) | Autologous and allogeneic MSCs from adipose tissue and bone marrow | Placebo, fibrin glue, standard care | Fistula healing, clinical response, AEs | Moderate to high | Cochrane risk-of-bias tool | Not assessed | Funnel plots indicate no publication bias | Local MSC therapy is safe and effective; higher healing rates with autologous MSCs and size-based dosing |

| Cheng 20207 | Patients with complex perianal fistulas (either of cryptoglandular origin or associated with CD) | PubMed and EMBASE, up to Mar 2020 | 2009–2020 | Seven RCTs | Autologous and allogeneic MSCs | Fibrin glue, saline solution | Healing rate, AEs, re-epithelialization | Moderate to high | Cochrane risk-of-bias tool | Not assessed | Funnel plot indicates no publication bias | Local MSC therapy is safe and efficacious for complex perianal fistulas; significant long-term efficacy; no significant difference in AEs |

| Cheng 202322 | Patients with perianal CD | PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, up to Mar 2022 | 2009–2022 | Six RCTs | Autologous and allogeneic MSCs | Saline solution, fibrin glue | Healing rate, AEs | Moderate to high | Cochrane risk-of-bias tool | Not assessed | Funnel plot indicates no publication bias | Local MSC injection is safe and efficacious for perianal fistulas in CD; significant long-term efficacy; no significant difference in AEs |

| Choi 201923 | Patients with complex perianal fistulas (CD and non-CD) | PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, up to Aug 2017 | 2005–2017 | Sixteen studies (3 RCTs, 13 non-RCTs) | Autologous and allogeneic MSCs | Conventional surgical methods | Healing rate, AEs, re-epithelialization | Moderate to high | MINORS | Not assessed | Funnel plot and Orwin’s fail-safe N indicate possible publication bias | Stem cell therapy is effective for complex perianal fistulas; higher healing rates with autologous MSCs; further large-scale RCTs needed |

| Ciccocioppo 201924 | Patients with CD or cryptoglandular fistulas | MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, May 2017 | 2003–2017 | Twenty-three studies (4 RCTs, 10 one-arm trials, 7 observational) | Autologous and allogeneic MSCs from adipose tissue and bone marrow | Placebo, fibrin glue, standard care | Fistula closure, radiological healing, AEs | Moderate to high | Cochrane risk-of-bias assessment instrument | Not assessed | Funnel plots indicate no publication bias | 80% fistula closure in MSC-treated patients; 64% in MSC vs. 37% in control in RCTs; low incidence of treatment-related AEs |

| Dave 201525 | Patients with IBD, including CD and UC | PubMed (since inception to Mar 2015), EMBASE (since inception to Nov 2014) | 2009–2013 | Twelve studies (RCTs and observational) | MSCs from various sources including BM, adipose tissue, and UC | Placebo, standard of care, fibrin glue | Healing of perianal fistulas, clinical remission, AEs | High | Cochrane risk of bias tool | Not assessed | Possible publication bias indicated by funnel plot | MSCs show promise in treating IBD with healing of perianal fistulas and induction of clinical remission; challenges include cost and characterization |

| El-Nakeep 202226 | Patients with medically refractory CD | MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP; up to Mar 19, 2021 | 2009–2020 | Seven RCTs | HSCs and MSCs | Standard of care, placebo | Clinical remission, CDAI <150 at 24 weeks, fistula closure short-term, fistula closure long-term, total AEs, SAEs, withdrawal due to AEs | Moderate to high | Cochrane risk-of-bias tool | Low to very low certainty | Possible publication bias indicated by funnel plot | SCT shows uncertain effects on clinical remission and CDAI <150 at 24 weeks; beneficial for fistula closure short and long-term; likely increases SAEs |

| Ko 202127 | Patients with IBD, including CD and UC | PubMed, from inception to Oct 29, 2020 | 2016–2022 | Thirty-two studies | MSCs | Placebo, standard of care | Healing of perianal fistulas, clinical remission, AEs | Moderate to high | Not assessed | Not assessed | Not assessed | Local MSC injections for PFCD support long-term efficacy and safety; mixed evidence for systemic MSC infusion in luminal IBD due to methodological heterogeneity |

| Lee 201728 | Patients with Crohn’s anal fistula | MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Jan 1995–Mar 2016 | 1995–2016 | Thirty-nine retrospective, 16 prospective cohorts, 5 open-label, 3 RCTs | MSC, ASC | Various surgical interventions including setons, advancement flaps, fistula plugs | Fistula healing rate | Overall high risk of bias | Cochrane ROBINS-I and ROB tool | Not assessed | Not assessed | Surgical interventions for Crohn’s anal fistula are heterogeneous with high bias. Standardization needed for better understanding of treatment options |

| Lei Ye 201629 | CD patients, age ≥18, refractory to or unsuitable for current therapies | Cochrane Library, PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, ISI Web of Knowledge, ClinicalTrials.gov, up to Sep 2015 | 2007–2015 | Eighteen articles (six clinical trials with HSCs, 12 with MSCs) | Autologous/Allogeneic MSCs, HSCs | Self-control or placebo controls using fibrin glue or routine therapies | Clinical remission, endoscopic response, perianal fistulas healing/closure, SAEs | Moderate to high | Cochrane ROB-1, NOS | Not assessed | Not assessed | MSCs reduce CDAI and alleviate CD symptoms; low incidence of SAEs |

| Li 202330 | Patients with perianal fistulizing CD | PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE; Mar 2022 | 2016–2022 | Five RCTs | MSCs | Placebo | Efficacy (remission), safety (TEAEs, perianal abscess, proctalgia) | High | Cochrane risk of bias tool | Not assessed | Low possibility of publication bias indicated by symmetrical funnel plot | MSCs treatment leads to definite remission (OR 2.06, P<.0001); no significant increase in TEAEs, perianal abscess, or proctalgia |

| Lightner 201831 | Patients with perianal CD | PubMed, Cochrane Library Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE; Jan 1, 2003 - Oct 31, 2017 | 2003–2017 | Eleven studies (phase I, II, III trials) | MSCs (autologous and allogeneic) | Placebo, fibrin glue, no treatment | Safety and efficacy of MSCs, AEs, SAEs, fistula healing rates | Moderate | Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool for RCTs, NOS | Not assessed | Not assessed | MSCs improve healing rates for perianal CD; no significant increase in AEs or SAEs; higher healing rates with MSCs vs. conventional treatments |

| Narang 201632 | Adults with cryptoglandular fistula in ano | MEDLINE (PubMed and Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Cochrane Library, 2007–2014 | 2007–2014 | Twenty-one articles (two RCTs, rest observational) | Not specified | Placebo or no treatment | Fistula closure rate, complications | Moderate to high | MINORS | Not assessed | Not assessed | New techniques are in early stages, with difficult-to-reproduce results and lacking long-term data. No clear evidence currently favors any specific technique |

| Qiu 201733 | Patients with active CD | PubMed, Cochrane Library CENTRAL, EMBASE; initial search Feb 5, 2015; updated Oct 15, 2016 | 2002–2016 | Twenty-one studies (RCTs and observational) | HSCs and MSCs (both autologous and allogeneic) | Various, including placebo and standard of care | Clinical response, clinical remission, fistula healing, endoscopic remission, SAEs, recurrence | Varied, mostly moderate to high | Cochrane risk of bias tool for RCTs, NOS | Not assessed | Egger test indicates publication bias exists for clinical response but not for fistula healing | Stem cell therapy potentially effective for refractory CD; high efficacy in inducing fistula healing; toxicity is a significant barrier |

| Qiu 202434 | Adult patients with medically refractory CD or CD-related fistula | PubMed, CENTER (Cochrane Library), EMBASE (Ovid); up to 5 Sep 2023 | 2009–2023 | Twelve RCTs | ADSCs, BM-MSCs, HSCs, placenta-derived cells, UC-MSCs | Placebo, no treatment | Clinical remission, SAEs | Varied, mostly moderate to high | Cochrane risk of bias tool (ROB 2.0) | Moderate certainty | Minimal risk of publication bias detected | SCT significantly increases likelihood of CR vs. placebo/no treatment; not associated with higher likelihood of SAEs |

| Wang 202335 | Patients with complex perianal fistulas of cryptoglandular or CD origin | PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library database, US ClinicalTrials.gov; up to May 15, 2022 | 2009–2020 | Six clinical trials, 10 publications | ASCs, BSCs | Placebo, fibrin glue, saline solution, surgery | Healing rates (HR), safety, efficacy, AEs, SAEs, recurrence, re-epithelialization | Low to high | Cochrane risk of bias tool | Not assessed | No publication bias detected | MSCs therapy superior to conventional treatment in short, long, and over-long-term follow-up; no statistical difference in medium-term efficacy; both autologous and allogeneic MSCs effective |

AEs, adverse events; ASC, adipose-derived stem cell; BM-MSC, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell; CD, Crohn’s disease; CDAI, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; ICTRP, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; PDAI, Perianal Disease Activity Index; PFCD, Perianal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease; RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROB, risk of bias; SAEs, serious adverse events; TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events; UC-MSC, umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell.

Efficacy

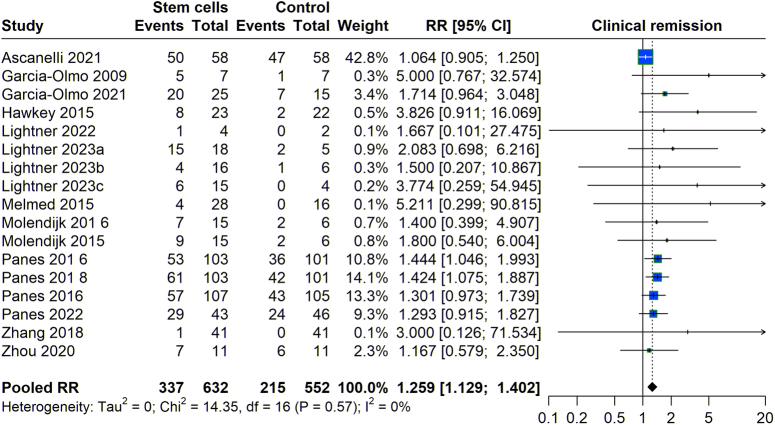

We assessed the effectiveness of stem cell treatment inducing clinical remission among patients with fistula. Analyzing studies from 2003 to 2023 revealed a relative risk (RR) of 1.299 (95% CI: 1.192–1.420), suggesting that patients receiving stem cell therapy were ~30% more likely to achieve clinical remission than those in the control group. The data exhibited very low heterogeneity (I²=0%), indicating a consistent effect across the studies, which supports the benefit of stem cell therapy to induce clinical remission in fistula effectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical remission with stem cell therapy versus control group.

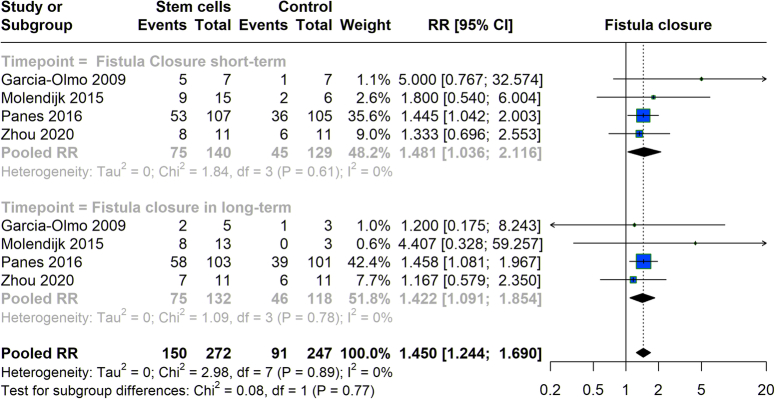

We explored the effectiveness of stem cell therapy in closing, considering both short-term and long-term outcomes. In the short-term, the pooled RR was 1.481 (95% CI: 1.036–2.116), demonstrating a 48.1% increased likelihood of achieving fistula closure shortly after treatment compared to controls, with minimal heterogeneity (I²=0%). The studies indicated a continued benefit for long-term outcomes with an overall RR of 1.422 (95% CI: 1.091–1.854), indicating a 42.2% greater likelihood of maintaining fistula closure. This consistent support across time frames highlights the effectiveness of stem cell therapy in managing fistula (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Fistula closure with stem cell therapy versus control group.

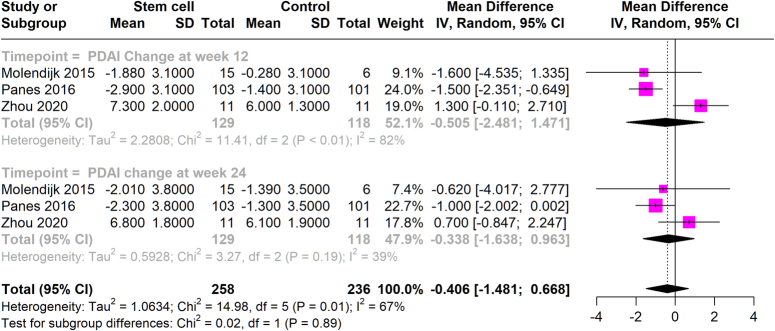

The effect of stem cell therapy on PDAI scores was analyzed by comparing the stem cell-treated groups to control groups over specific time frames. At 12 weeks, the analysis showed a negligible mean difference in PDAI scores of −0.505 (95% CI: −2.481 to 1.471), with a high heterogeneity (I²=82%). At 24 weeks, the mean difference slightly improved to −0.338 (95% CI: −1.638 to 0.963), with reduced heterogeneity (I²=39%). These findings suggest that stem cell therapy does not significantly impact PDAI scores (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Mean PDAI at 12 weeks and 24 weeks with stem cell therapy versus control group.

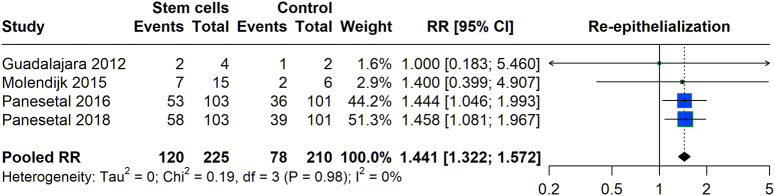

We assessed the re-epithelialization associated with stem cell therapy compared to controls. The pooled data analysis from various studies showed an RR of 1.44 (95% CI: 1.322–1.572). This indicates a higher risk of re-epithelialization with stem cell treatment. The heterogeneity across the studies was found to be negligible (I²=0%), suggesting consistent findings among the included studies regarding the effect of stem cell treatment on re-epithelialization (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Re-epithelialization with stem cell therapy versus control group.

Safety

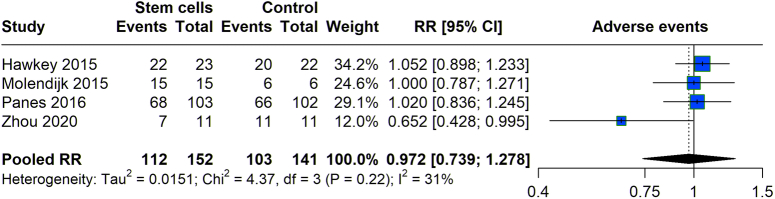

We evaluated the frequency of adverse events in patients undergoing stem cell treatment versus those in control groups across various studies. Data revealed that the stem cell group experienced 112 adverse events out of 152 participants, while the control group reported 103 adverse events from 141 participants (Fig. 6). The pooled RR for experiencing adverse events with stem cell therapy was calculated at 0.972 (95% CI: 0.739–1.278), suggesting no statistically significant difference in the risk of adverse events between the two groups, as the CI straddles the value of 1. The heterogeneity among the included studies was moderate (I 2= 31%).

Figure 6.

Adverse events with stem cell therapy versus control group.

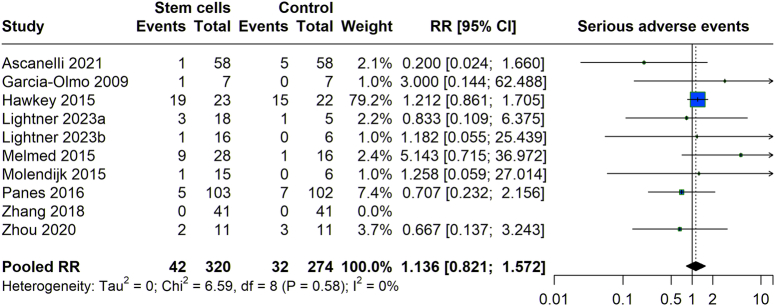

The risk of serious adverse events (SAEs) associated with stem cell therapy was also evaluated compared to control groups across multiple studies (Fig. 7). The analysis indicated that were 42 SAEs reported among 320 participants in treatment groups, in comparison to 32 SAEs among 274 participants in the control groups. The pooled RR for SAEs was 1.136 (95% CI: 0.821–1.572), crossing the threshold of 1, which signifies that the observed increase in risk of SAEs for the stem cell groups was not statistically significant. With an I² of 0%, the results showed very low heterogeneity, highlighting consistent findings across studies and confirming that stem cell therapy does not significantly elevate the risk of SEA compared to conventional controls.

Figure 7.

Serious adverse events with stem cell therapy versus control group.

Discussion

The exploration of stem cell therapy for the treatment of fistulas shows a pivotal shift towards regenerative medicine in managing conditions traditionally reliant on surgical interventions. This umbrella review synthesizes evidence from a wide array of systematic reviews, offering a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of stem cell therapy as a promising alternative to conventional treatments.

Our findings reveal that stem cell therapy, particularly using MSCs derived from adipose tissue and bone marrow, exhibits significant potential in inducing clinical remission and promoting fistula closure. The pooled data from the meta-analyses suggest a higher likelihood of achieving clinical remission and fistula closure than traditional treatments. This is particularly noteworthy given the chronic and often refractory nature of fistulas associated with CD, where surgical outcomes can be unpredictable and recurrence rates high.

The clinical remission rates, as demonstrated by a relative risk of 1.299, indicate a 30% improvement over controls, which is statistically significant and clinically relevant. Similarly, the ability of stem cell therapy to achieve fistula closure in the short-term and maintain it in the long-term provides evidence of its role not only as a treatment modality but also in potentially altering the disease course. The analysis of PDAI scores, a critical measure for evaluating the severity and activity of perianal disease, provided mixed results. At 12 weeks, the meta-analysis showed a negligible mean difference in PDAI scores in the stem cell treatment groups and controls, with high heterogeneity observed (I²=82%). This variation decreased significantly at 24 weeks, where the mean difference improved slightly, albeit still not reaching statistical significance, and with reduced heterogeneity (I²=39%). These results indicate that although stem cell therapy may not have a substantial immediate effect on reducing PDAI scores, there could be a trend towards improvement over time. This indicates that the therapeutic effects of stem cells on symptomatic relief might require longer periods to manifest significantly, which aligns with the gradual process of tissue repair and immunomodulation mediated by these cells. Re-epithelialization is a critical factor in the healing process of fistulas, indicating the restoration of the epithelial layer over the fistula tract. Our findings from the pooled analysis revealed a relative risk of 1.44 for improved re-epithelialization with stem cell therapy, suggesting a positive effect. The consistency of this outcome across studies, as indicated by a very low heterogeneity, shows the potential of stem cells to promote epithelial healing. This is particularly relevant in fistulas, where the failure of epithelial closure can lead to recurrent infections and prolonged discomfort. While the direct impact on PDAI scores may not be immediately evident, the positive trends in re-epithelialization suggest that stem cells could play a crucial role in the underlying healing mechanisms. These outcomes emphasize the need for further targeted research to fully elucidate the scope of benefits that stem cell therapy can offer, particularly focusing on long-term symptomatic relief and quality of life improvements in patients with chronic and complex fistular diseases. This would involve not only more comprehensive clinical trials but also detailed mechanistic studies to better understand how stem cells interact at the molecular and cellular levels to facilitate healing and remission in fistula patients.

Our analysis finds that stem cell therapy does not increase the risk of adverse events or SEA compared to controls. This is supported by pooled relative risks which straddle the unity, indicating no significant difference in the risk of adverse events between stem cell therapy and conventional treatments. Considering the invasive nature and potential complications associated with surgical interventions, such a safety profile is crucial.

The benefit of MSCs in fistula treatment is primarily due to their ability to regulate immune responses and enhance tissue regeneration36. MSCs are known for their immunomodulatory effects, which can significantly reduce inflammation. Inflammation is a critical component in the pathology of fistulas, particularly those associated with autoimmune disorders like CD37. Additionally, their capacity to differentiate into various cell types and secrete growth factors such as VEGF, TGF-β, and FGF aids in healing and tissue repair, addressing both the symptoms and underlying causes of fistulas38. The therapeutic potential of MSCs in fistula treatment also hinges on their unique abilities for differentiation and self-renewal, governed by intricate signaling pathways and regulatory transcription factors39. In the environment of a fistula, MSCs are thought to predominantly modulate healing through these mechanisms. Key signaling pathways include Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Hedgehog, which are crucial for maintaining the balance between stem cell renewal and differentiation40. These pathways, in response to the local microenvironment, activate specific transcription factors like Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog, helping maintain the pluripotency and self-renewal capacities of MSCs41.

The promising results observed in the application of stem cell therapy for fistulas, particularly in terms of clinical remission and re-epithelialization, set a compelling groundwork for future research in this field. However, several key areas require further exploration to optimize and standardize this therapeutic approach. The systematic reviews included in our umbrella review demonstrated a range of methodological quality, with many exhibiting moderate to high risk of bias. This variability highlights a significant concern, as it may impact the reliability and validity of the conclusions drawn about the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy in fistula management. To address these concerns, we recommend that future research prioritize the inclusion of high-quality, well-designed RCTs. These studies should adhere to rigorous methodological standards to enhance the strength of the evidence. Furthermore, it is crucial for systematic reviews to incorporate comprehensive risk-of-bias assessments and conduct sensitivity analyses. Such measures will help ensure the reliability of the conclusions and minimize potential bias, providing a clearer and more accurate understanding of the effects of stem cell therapy on fistula treatment.

These studies should also standardize the types and preparations of stem cells used, dosages, and administration routes to establish clearer protocols that can be universally recommended. Moreover, the long-term safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy require comprehensive assessment. While initial results are encouraging, long-term follow-up studies are necessary to observe any potential adverse effects or relapse rates, which are crucial for validating the sustained benefits of this treatment. Additionally, research should focus on understanding the mechanisms by which stem cells influence tissue healing and immune modulation in the context of fistulas. Detailed mechanistic studies would not only elucidate the pathways involved but also potentially identify biomarkers that can predict treatment response or indicate the likelihood of relapse, thereby personalizing treatment approaches. Another important area of research involves the comparative effectiveness of stem cell therapy against existing standard treatments across different types of fistulas. This would position stem cell therapy within the current treatment paradigm, potentially offering a less invasive alternative to surgery for patients with complex or recurrent fistulas. Furthermore, the economic implications of stem cell therapy, including cost-effectiveness and accessibility, should be evaluated. This is particularly pertinent in settings where healthcare resources are limited, and the burden of surgical interventions is high. Research into optimizing the production and storage of stem cells can help reduce costs and improve the feasibility of this therapy in clinical settings. It is imperative that future studies incorporate a comprehensive evaluation of patient-reported outcomes, including metrics on quality of life, symptom relief, and functional status. These aspects are crucial for understanding the full impact of therapeutic interventions on patients’ daily lives and overall well-being.

There are a few limitations of this study. The inherent heterogeneity in the systematic reviews included in the study design, population characteristics, types of stem cells used, and their administration methods might have influenced the overall conclusions. Such variability can complicate the aggregation of data and interpretation of pooled results. The quality of the reviewed studies differed, with some studies with moderate to high risk of bias. This variability in study quality could affect the reliability of the conclusions drawn about the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy. An additional limitation is the language bias, since only English-language studies were included, possibly omitting relevant data published in other languages. The reviews predominantly included studies on fistulas related to CD, which may not fully represent other types of fistulas, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings to all fistular conditions. These limitations highlight the necessity for better-quality research and suggest caution in extrapolating these results to all fistula treatments without further evidence.

Conclusion

Stem cell therapy represents a promising advancement in the treatment of fistulas, offering the potential to improve outcomes for patients with limited options under current standard care. However, the current evidence base is insufficient to definitively establish the effectiveness of stem cell therapy in fistula treatment. More high-quality studies are needed to confirm the benefits of stem cell therapy for fistulas.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Not applicable.

Source of funding

The authors (S.M., A.F., and S.I.A.) gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through Project Number: RG24-M014.

Author contribution

T.T., S.M., H.A.A., and M.S.: conceptualization; A.F., R.R., P.S., A.S., A.K.: data curation; M.S., G.V.S.P., S.R., and J.A.: formal analysis; S.S., S.G., G.B., and N.C.: investigation; S.G., G.B., S.I.A., and M.S.: methodology; H.A.A., A.F., and R.R.: project administration; S.M., P.S., T.T., R.M., S.P., and M.B.: resources; S.I.A., G.V.S.P., and A.K.B.: software; S.S., S.G., and M.N.K.: supervision; H.A.A., A.F., and M.N.K.: validation; S.R., J.A., K.B., and M.P.: visualization; S.M., M.S., K.B., and M.P.: writing of manuscript; S.G., G.B., and S.I.A.: Reviewing and editing of manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

PROSPERO: CRD42024557858.

Guarantor

Muhammed Shabil.

Data availability statement

The data are available in the supplementary material and with the authors, available upon request.

Provenance and peer review

Invited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors (S.M., A.F., and S.I.A.) gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through Project Number: RG24-M014.

Footnotes

Tripti Tripathi and Shilpa Gaidhane contributed equally as first authors.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 28 October 2024

Contributor Information

Tripti Tripathi, Email: triptitripathi66@gmail.com.

Syam Mohan, Email: syammohanm@yahoo.com.

Hassan A. Alfaifi, Email: haaalfaifi@moh.gov.sa.

Abdullah Farasani, Email: aofarasani@jazanu.edu.sa.

Roopashree R, Email: r.roopashree@jainuniversity.ac.in.

Pawan Sharma, Email: pawan.sharma000@outlook.com.

Abhishek Sharma, Email: abhishek.Sharma1@nimsuniversity.org.

Apurva Koul, Email: Apurva2978.research@cgcjhanjeri.in.

G. V. Siva Prasad, Email: sivaprasad.gv@raghuenggcollege.in.

Sarvesh Rustagi, Email: sarveshrustagi@uumail.in.

Jigisha Anand, Email: jigishaanand.bio@geu.ac.in.

Sanjit Sah, Email: sanjitsahnepal561@gmail.com.

Shilpa Gaidhane, Email: shilpa.gaidhane@dmiher.edu.in.

Ganesh Bushi, Email: ganeshbushi313@gmail.com.

Diptismita Jena, Email: diptismita.jena@gmail.com.

Mahalaqua N. Khatib, Email: nazlikhatib@dmiher.edu.in.

Muhammed Shabil, Email: mohdshabil99@gmail.com.

Siddig I. Abdelwahab, Email: siddigroa@yahoo.com.

Kiran Bhopte, Email: kiran.research@iesuniversity.ac.in.

Manvi Pant, Email: manvi.panrt@ndimdelhi.org.

Rachana Mehta, Email: mehtarachana89@gmail.com.

Sakshi Pandey, Email: sakshi.pandey.orp@chitkara.edu.in.

Manvinder Brar, Email: manvinder.brar.orp@chitkara.edu.in.

Nagavalli Chilakam, Email: nagavallichilakam9@gmail.com.

Ashok K. Balaraman, Email: ashok@cyberjaya.edu.my.

References

- 1.Slinger G, Trautvetter L. Addressing the fistula treatment gap and rising to the 2030 challenge. Int J Gynecol Obstetr 2020;148:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Włodarczyk M, Włodarczyk J, Sobolewska-Włodarczyk A, et al. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of cryptoglandular perianal fistula. J Int Med Res 2021;49:0300060520986669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charalampopoulos A, Papakonstantinou D, Bagias G, et al. Surgery of simple and complex anal fistulae in adults: a review of the literature for optimal surgical outcomes. Cureus 2023;15:e35888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afshari A, Shamdani S, Uzan G, et al. Different approaches for transformation of mesenchymal stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2020;11:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang X, Meng Y, Han Z, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver disease: full of chances and challenges. Cell Biosci 2020;10:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Y, Ji C, Lu L. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver fibrosis/cirrhosis. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng F, Huang Z, Li Z. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cells in treatment of complex perianal fistulas: a meta-analysis. Stem Cells Int 2020;2020:8816737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suresh V, Jomon De J, Manasa G, et al. Advancements of artificial intelligence-driven approaches in the use of stem cell therapy in diseases or disorders: clinical applications and ethical issues. The Evidence 2024;2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Arranz M, Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros MD, et al. Autologous adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular perianal fistula: a randomized clinical trial with long-term follow-up. Stem Cells Transl Med 2020;9:295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid Implement 2015;13:132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey P, Shabil M, Bushi G. Comment on “Sodium fluorescein and 5-aminolevulinic acid fluorescence-guided biopsy in brain lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. J Neurooncol 2024;1–2. doi: 10.1007/s11060-024-04820-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alrahbeni T, Mahal A, Alkhouri A, et al. Surgical interventions for intractable migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2024;110:6306–6313; 10.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shabil M, Khatib MN, Banda GT, et al. Effectiveness of early Anakinra on cardiac function in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome of COVID-19: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2024;24:847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goel S, Shabil M, Kaur J, et al. Safety, efficacy and health impact of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS): an umbrella review protocol. BMJ Open 2024;14:e080274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shamim MA, Gandhi AP, Dwivedi P, et al. How to perform meta-analysis in R: a simple yet comprehensive guide. The Evidence 2023;1:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shabil M, Bushi G, Khatib MN. A commentary on “Psychological health among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: an updated meta-analysis”. Indian J Psychiatry 2024;66:763–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernardi L, Santos C, Pinheiro VAZ, et al. Transplantation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in refractory Crohn’s disease: systematic review. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2019;32:e1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Ding Z, Han C, et al. Efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cells for fistula treatment of Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y, Su Q, Zhang B, et al. Efficacy of stem cells therapy for Crohn’s fistula: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Stem Cell Res Ther 2021;12:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng F, Huang Z, Li Z. Mesenchymal stem-cell therapy for perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol 2019;23:613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng F, Huang Z, Wei W, et al. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Choi S, Jeon BG, Chae G, et al. The clinical efficacy of stem cell therapy for complex perianal fistulas: a meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol 2019;23:411–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciccocioppo R, Klersy C, Leffler DA, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: safety and efficacy of local injections of mesenchymal stem cells in perianal fistulas. JGH Open 2019;3:249–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dave M, Mehta K, Luther J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:2696–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Nakeep S, Shawky A, Abbas SF, et al. Stem cell transplantation for induction of remission in medically refractory Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022;5:CD013070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko JZ, Johnson S, Dave M. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases: an up-to-date systematic review. Biomolecules 2021;11:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MJ, Heywood N, Adegbola S, et al. Systematic review of surgical interventions for Crohn’s anal fistula. BJS Open 2017;1:55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye L, Wu X, Yu N, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of stem cells in refractory Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. J Cellul Immunother 2016;2:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li A, Liu S, Li L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells versus placebo for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Surg Innov 2023;30:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lightner AL, Wang Z, Zubair AC, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mesenchymal stem cell injections for the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease: progress made and future directions. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narang SK, Keogh K, Alam NN, et al. A systematic review of new treatments for cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Surgeon 2017;15:30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu Y, Li M-y, Feng T, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy for Crohn’s disease. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu Y, Li C, Sheng S. Efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024;15:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Jiang HY, Zhang YX, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for perianal fistulas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther 2023;14:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang M, Yuan Q, Xie L. Mesenchymal stem cell‐based immunomodulation: properties and clinical application. Stem Cells Int 2018;2018:3057624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao F, Chiu S, Motan D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis 2016;7:e2062-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azari Z, Nazarnezhad S, Webster TJ, et al. Stem cell-mediated angiogenesis in skin tissue engineering and wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2022;30:421–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaripova LN, Midgley A, Christmas SE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in the pathogenesis and therapy of autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:16040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H-M, Yuan S, Meng H, et al. Stem Cell-Based Therapies For Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:8494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zakrzewski W, Dobrzyński M, Szymonowicz M, et al. Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019;10:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in the supplementary material and with the authors, available upon request.