Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is defined as hepatic steatosis with at least one concomitant cardiovascular risk factor, and has emerged as the most frequent liver disease worldwide (1). It conveys risks of liver disease progression to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) and of cardiovascular events (2).

In MASLD, several treatment options for cardiometabolic comorbidities are safe, but previously, their impact on liver disease was either insufficiently studied or lacking, without adequately addressing liver pathology. For example, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) are only recommended for their respective indications, namely type 2 diabetes and obesity (2). While significant steatosis reduction was achieved with the GLP-1RA semaglutide, liver fibrosis was not significantly improved in a phase II trial (3), and higher-level, histologically controlled evidence in MASLD is still lacking.

In 2024, resmetirom, a β-selective thyromimetic, was the first drug to gain FDA approval for moderate and advanced MASH-fibrosis due to the effect of histological MASH resolution and fibrosis improvement reported in the MAESTRO-NASH randomized controlled trial (RCT) (4). The rationale for targeting liver thyroid hormone receptors (THRs) in the liver lies in the intense regulation of hepatic metabolic fuctions by the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) and the signalling through THRβ. As such, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) elevation, even within the euthyroid range with normal-range thyroid hormones, is an independent risk factor for MASLD (5). Thyroid hormone effects in hepatocytes are mediated through THRβ, stimulating carbohydrate metabolism and fatty acid β-oxidation and increasing fatty acid absorption from lipoproteins, resulting in systemically lowered low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) levels (6). Resmetirom selectively targets THRβ, thus avoiding THRα-mediated cardiac effects (6).

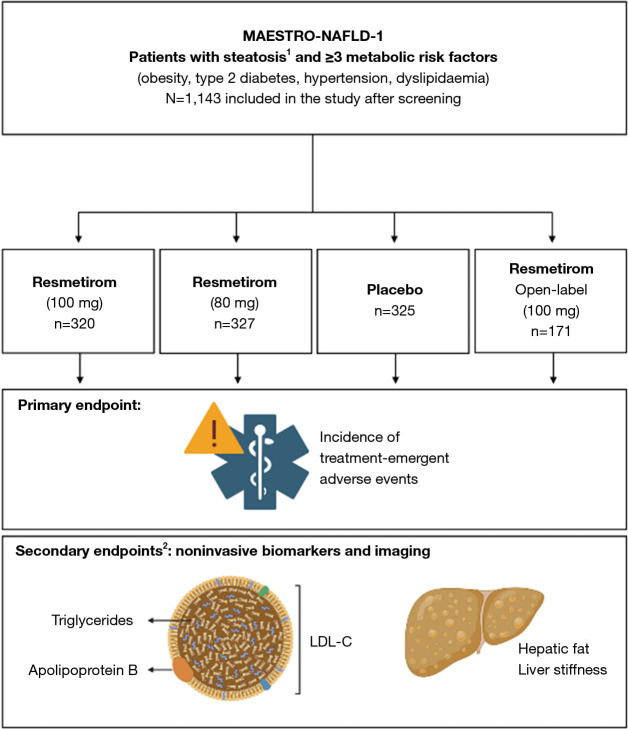

The MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 trial, published by Harrison et al. in 2023, was a multicentric RCT investigating resmetirom for the treatment of MASLD/MASH. The study focused on resmetirom safety profiles (treatment-emergent adverse events, TEAEs) as the primary outcome and serum and imaging biomarkers as non-invasive secondary endpoints (Figure 1) (7).

Figure 1.

Trial design of the MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 trial. The MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 (NCT04197479) trial [adapted from (7)] randomized patients to three double-blind arms. Treatment-emergent adverse events constituted the primary endpoint, metabolic and hepatic readouts were the secondary endpoints. Given numbers represent randomized subjects. Figure created with Biorender.com. 1, non-invasive testing for screening; 2, selected secondary outcomes are depicted. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

This study demonstrated an adequate safety profile of both resmetirom dosages across the 52-week study timeframe. TEAE rates in excess of placebo included mild or moderate diarrhea and nausea in the resmetirom treatment arms, particularly within the first 12 weeks of treatment, and nausea, more common in females (7).

The central secondary endpoint, hepatic fat content, was met at 16 weeks post treatment initiation, with a highly significant reduction compared to placebo in all resmetirom arms. At 52 weeks, an average mean reduction of 36.7–51.8% in hepatic fat from baseline in the resmetirom arm was noted, with the effect more pronounced in the two 100-mg-dosage groups. Regarding predictive biomarkers for treatment response, weight loss ≥5% in combination with resmetirom treatment, or high resmetirom exposure [reflected in a high sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) response], was associated with a greater reduction in hepatic fat. While the the mean change from baseline liver stiffness measurement for patients with presumed moderate fibrosis F2 was not significant at 52 weeks, a numerically greater percentage of patients in the resmetirom arms achieved a reduction of ≥2 kPa in vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE).

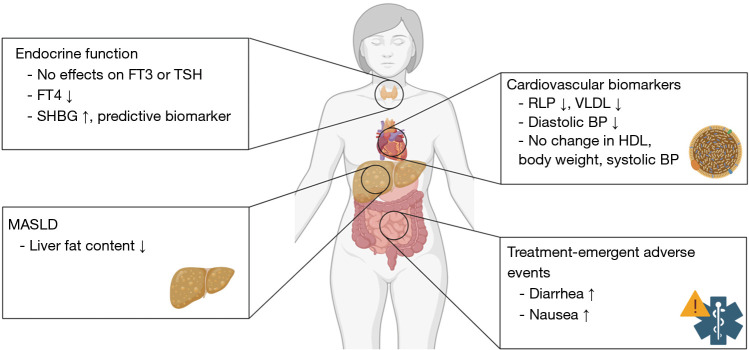

All resmetirom arms had a significant reduction of the atherogenic biomarkers LDL-C, apolipoprotein B (apoB), and triglycerides (TG) compared to placebo. This effect was sustained from 24 to 48 weeks after treatment initiation. Further cardiovascular readouts that were ameliorated with resmetirom included remnant-like particle (RLP) cholesterol, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol, atherogenic lipoprotein particles LDL and small LDL particles. The study found no significant impact on blood sugar control and body weight (Figure 2) (7).

Figure 2.

Effects of Resmetirom, as reported by the MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 trial. Only selected effects from the study (7) are depicted. Figure created with Biorender.com. BP, blood pressure; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; HDL, high density lipoprotein; MASLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; RLP, remnant-like particle; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

The present study by Harrison et al. provides striking evidence for resmetirom, especially in the context of decades of negative clinical trials in liver fibrosis of non-metabolic etiology, and the pressing need to address the growing health burden of MASH (1). While the MAESTRO-NASH RCT, designed to expedite FDA approval, used NASH severity, as quantified by NAS and fibrosis stage as the best-documented readout for MASLD-related survival and transplant-free survival (8), the present trial used non-invasive biomarkers and imaging endpoints. It is particularly interesting that resmetirom did not only address hepatic steatosis, but also the other metabolic components of the MASLD diagnosis, reflected in the positive influence on atherogenic biomarkers (7).

Possible concerns in the long-term setting are endocrine-related changes and interactions with other hormone-related diseases or therapies. Treatment with resmetirom reduced levels of prohormone free T4 and, but not TSH or free T3, while increasing concentrations of SHBG (4). The mechanism or long-term clinical impact of the free T4 downregulation, as well as the stability of endocrine effects over time remain to be determined. In the present trial, over 40% of patients in the open-label arm were on thyroxine medication due to hypothyreodism, without noted adverse effects or interactions with resmetirom. Similarly, a high proportion of patients in the trial were on concomitant antidiabetic drugs or medication for dyslipidemia, without any reported disadvantages (7).

Further questions in real-life cohorts may pertain to concomitant alcohol consumption, which is clinically discouraged in patients with MASLD/MASH (2), but frequent in real-life cohorts with steatosis: in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) dataset, around 2.6% of of US citizens hat metabolic steatosis with concomitant significant alcohol consumption (MetALD) (9).

Present evidence on resmetirom is limited to 52 weeks, and mostly patients with F2/3 stages. Recognizing that MASLD is a chronic, dynamic disease with possible progression and complications, the authors are currently pursuing several further research directions for resmetirom. While the present trial focussed on F2/F3 stages, the MAESTRO-NASH-OUTCOMES trial investigates resmetirom in patients with MASH-cirrhosis, evaluating disease progression and events of hepatic decompensation (8). Ongoing RCTs within the framework of the MAESTRO clinical program are investigating longer-term treatment extension (8), and will provide evidence on the sustainability of the encouraging responses observed in the present publication.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, HepatoBiliary Surgery and Nutrition. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://hbsn.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/hbsn-24-568/coif). F.T. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of HepatoBiliary Surgery and Nutrition. F.T. reports research funding from AstraZeneca, MSD, Gilead, Agomab (fundings to his institution); consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Gilead, GSK, Abbvie, BMS, Intercept, Ipsen, Pfizer, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, MSD, Sanofi, Boehringer; payment or honoraria from Gilead, AbbVie, Falk, Merz, Intercept, Sanofi, Astra Zeneca, Orphalan, Boehringer; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Gilead; participation in Advisory Boards from Sanofi and Pfizer. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:851-61. 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) ; European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO); EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol 2024;81:492-542. 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1113-24. 10.1056/NEJMoa2028395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison SA, Bedossa P, Guy CD, et al. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2024;390:497-509. 10.1056/NEJMoa2309000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YL, Tian S, Wu J, et al. Impact of Thyroid Function on the Prevalence and Mortality of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023;108:e434-43. 10.1210/clinem/dgad016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wirth EK, Puengel T, Spranger J, et al. Thyroid hormones as a disease modifier and therapeutic target in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 2022;17:425-34. 10.1080/17446651.2022.2110864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison SA, Taub R, Neff GW, et al. Resmetirom for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med 2023;29:2919-28. 10.1038/s41591-023-02603-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison SA, Ratziu V, Anstee QM, et al. Design of the phase 3 MAESTRO clinical program to evaluate resmetirom for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2024;59:51-63. 10.1111/apt.17734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalligeros M, Vassilopoulos A, Vassilopoulos S, et al. Prevalence of Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD, MetALD, and ALD) in the United States: NHANES 2017-2020. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024;22:1330-1332.e4. 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as